Abstract

The spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 began later in Africa than in Asia and Europe. Senegal confirmed its first case of coronavirus disease on March 2, 2020. By March 4, a total of 4 cases had been confirmed, all in patients who traveled from Europe.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, viruses, respiratory infections, zoonoses, coronavirus disease, Senegal

The spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was delayed in Africa and Latin America. The earliest recorded case of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in Africa was identified in Egypt 7 weeks after the beginning of the outbreak (1). On February 28, 2020, Nigeria declared the first confirmed case in sub-Saharan Africa (2). On March 2, Senegal confirmed an imported case, then 2 additional imported cases the next day, and a fourth on March 4.

In Senegal, the Ministry of Health coordinated all standard operating procedures (SOPs) for the detection, notification, case management, and transport of persons with suspected COVID-19 cases from entry points (e.g., airport, harbor), healthcare centers, or locality to the referral service, using the initial WHO case definition (3). A nasopharyngeal swab specimen was collected from any symptomatic suspected case-patient or person in contact with confirmed case-patients for SARS-CoV-2–specific real-time RT-PCR testing at the Institut Pasteur Dakar (IPD) (Appendix). Samples were accompanied by a standardized investigation form collecting demographical information, clinical details, and history of exposure (contact with a confirmed case or history of travel).

In the case of a positive diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection, an active surveillance of contacts or co-exposed persons was initiated immediately around the index case. The nasopharyngeal swabs of positive patients were used for the next-generation sequencing.

Senegal experienced its first COVID-19 suspected case on February 26. During February 26–March 4, a total of 26 suspected case-patients (14 female and 12 male) were tested for a possible SARS-CoV-2 infection. Patient age range was 3–80 years (mean 35.16 years; median 33 years). Of the 26 suspected case-patients, 2 male and 2 female were confirmed as SARS-CoV-2 infected; they were 34 (patient 1), 82 (patient 2), 68 (patient 3), and 33 (patient 4) years of age. Because all were probably infected outside of the country, they were reported as imported cases. They all arrived by airplane, 3 from France and 1 from England. One case-patient had traveled manifesting symptoms undetected by the crew members. Patients 2 and 3, a married couple, traveled together; both had diabetes and hypertension, and both experienced mild clinical symptoms. All 4 patients were admitted to the Isolation and treatment Center (ITC) established by the Ministry of Health (MoH) in Dakar, Senegal. They all were apyretic the first day of hospitalization; they required mild supportive care but not oxygen therapy. In the adopted protocol, discharge of a patient from ITC required 2 consecutive negative tests for SARS-CoV-2 taken 48 hours apart. Patient 1 was discharged after 4 days, and patient 4 after 7 days, whereas patients 2 and 3 stayed for 16 days. Indeed, the viral shedding lasted longer with patients 2 and 3, the oldest. Patients 1 and 4 represented a moderate risk for dissemination of the disease, but patients 2 and 3 represented a high risk for diffusion. Investigations of contact cases and swabbing of high-risk contact cases have not to date identified any secondary cases.

We successfully obtained the complete genome sequences from the 4 SARS-CoV-2–positive patients’ samples. The 4 complete genomes were nearly identical across the whole genome; sequence identity was >99%. Outside of the stretch of 44 undetermined nucleotides (19360–19403) in the genome of the strain from patient 1, only 1 nucleotide difference was mapped in open reading frame 8 of patient 4’s virus isolate genome, at position 28259 with a T®C synonymous substitution in virus isolate genomes from patients 1, 2, and 3. All genome sequences have been deposited in GISAID database (https://www.gisaid.org; accession nos. EPI_ISL_418206–9).

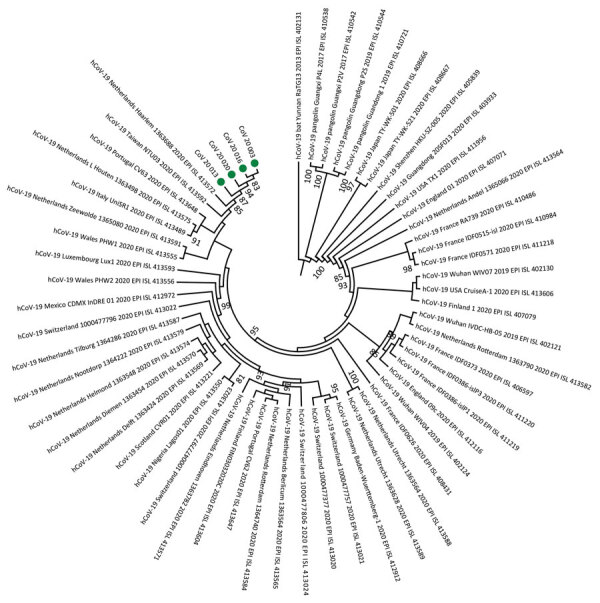

Phylogenetic analyses revealed that SARS-CoV-2 strains from Senegal clustered with strains from diverse origins (Europe, Asia, Latin America, and Africa). Of note, they were close to the hCoV-19 Netherlands Haarlem 1363688 2020 EPI ISL 413572 and hCoV-19 Taiwan NTU03 2020 EPI ISL 413592 strains. The strains from Senegal clustered together, as shown by the phylogenetic branch with a high bootstrap value of 99% (Figure). All strains from Senegal belong to the ORF8-L isoform.

Figure.

Phylogeny of 4 severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 strains isolated from Senegal (green dots). Whole-genome nucleotide sequences were compared with 56 other genome sequences from the coronavirus disease pandemic retrieved from GenBank and GISAID (https://www.gisaid.org) databases. Sequences were aligned with MAFFT (https://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server). We generated the phylogenetic tree by the maximum-likelihood method under the HKY85-gamma nucleotide substitution model using IQ-TREE (http://www.cibiv.at/software/iqtree). We assessed robustness of tree topology with 1,000 replicates; bootstrap values >75% are shown on the branches of the consensus trees. Phylogenetic analyses revealed that strains from Senegal clustered with strains from diverse origins (Europe, Asia, Latin America, and Africa). CoV, coronavirus; hCoV, human coronavirus.

The diagnosis of these cases showed the surveillance system of Senegal’s capacity to quickly detect, isolate, and investigate those cases to take adequate control measures. Our findings indicate that the earliest cases in Senegal or sub-Saharan Africa were imported from Europe, implying that the particularly high volume of direct flights from Europe was a key factor in the spread of the virus in West Africa. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that a few COVID-19 cases were missed at that time in Senegal, including paucisymptomatic or asymptomatic cases (4,5). Our study emphasizes the imperative need for efficient epidemiologic investigations to identify the cases and characterize the transmission modes to prevent, control, and stop the spread of COVID-19.

Additional information about the COVID-19 outbreak in Senegal.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Ministry of Health for COVID-19 surveillance coordination. We thank the healthcare workers and the IPD staff for its unwavering efforts in testing and tracing.

Biography

Dr. Dia is a virologist and head of the Reference Center for influenza and other respiratory viruses at Pasteur Institute Dakar. His primary research interests are the genetic and antigenic dynamics of influenza viruses in Senegal.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Dia N, Lakh NA, Diagne MM, Mbaye KD, Taieb F, Fall NM, et al. COVID-19 outbreak, Senegal, 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020 Nov [date cited]. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2611.202615

These authors contributed equally to this article.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. Update on COVID-19 in the Eastern Mediterranean Region, 16 February 2020. [cited 2020 Sep 8]. http://www.emro.who.int/media/news/update-on-covid-19-in-the-eastern-mediterranean-region.html

- 2.World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa. COVID-19 situation update for WHO African region, 4 March 2020. [cited 2020 Sep 8]. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331330/SITREP_COVID-19_WHOAFRO_20200304-eng.pdf

- 3-.World Health Organization. Global surveillance for human infection with novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV): interim guidance, 21 January 2020 [cited 2020 Sep 16]. https://www.ephi.gov.et/images/20200121-global-surveillance-for-2019-ncov.pdf

- 4.Rothe C, Schunk M, Sothmann P, Bretzel G, Froeschl G, Wallrauch C, et al. Transmission of 2019-nCoV infection from an asymptomatic contact in Germany. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:970–1. 10.1056/NEJMc2001468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spiteri G, Fielding J, Diercke M, Campese C, Enouf V, Gaymard A, et al. First cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the WHO European Region, 24 January to 21 February 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020;25. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.9.2000178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional information about the COVID-19 outbreak in Senegal.