Abstract

In this study, the induction of esterase activity during the degradation of a high concentration of di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) (1500 mg l−1) by Fusarium culmorum was investigated using Ca(NO3)2 as nitrogen source under liquid fermentation conditions. Assessments of esterase activities through biochemical tests and zymographic assays, as well as fungal growth were studied. A high concentration of DEHP increased esterase activity in F. culmorum, which produces five esterase isoforms (26.4, 31.7, 43, 73.6 and 125 kDa), which were different in abundance and molecular weight to those produced constitutively in glucose-containing medium (control medium). F. culmorum showed higher µ and YX/S values in DEHP-containing medium than those observed in the control medium. F. culmorum has great potential for use in the restoration of sites contaminated with high concentrations of DEHP and even of other phthalates with less complex structures.

Keywords: Ascomycete, Enzyme, Liquid fermentation, Plasticizer

Introduction

Phthalate esters (phthalates) are used as plastic additives (plasticizers) to increase the flexibility of plastics and are considered endocrine-disrupting chemicals (Pérez-Andres et al. 2017). Phthalates are present as pollutants at different levels in the environment because they are released from plastics (Hahladakis et al. 2018). Their concentrations range from trace levels to very high concentration, up to 500 mg l−1 (Net et al. 2015). In particular, DEHP has been listed as priority environmental pollutant by the United States Environmental Protection Agency and the China National Environmental Monitoring Centre (Yang et al. 2018). DEHP has been detected at concentrations from 7.5 to 2045 mg kg−1 in sediments from locations where it is manufactured (Green Facts 2008) and at concentrations as high as 1.4 ng l−1 in urban air in Europe (Guerranti et al. 2019). Phthalates are organic compounds that are resistant to hydrolysis and photolysis in the environment. Because biodegradation plays a significant role in elimination of phthalates from environment with properties of high efficiency, environmental safety and low cost, it is the most promising process for remediating phthalate-contaminated environments (Fan et al. 2018; Bope et al. 2019). Therefore, it is important to identify efficient phthalate degraders and to increase our knowledge regarding enzyme production by phthalate-degrading organisms, which will enhance phthalate biodegradation efforts and allow these pollutants to be eliminated from the environment. Fusarium species are highly efficient phthalate-degrading organisms due to their production of esterases, which catalyze the hydrolysis of ester bonds in phthalates to carboxylic acids (Aguilar-Alvarado et al. 2015; Ahuactzin-Pérez et al. 2016; González-Márquez et al. 2019a). Studies on DEHP biodegradation by Fusarium culmorum revealed that this organism is able efficiently to degrade DEHP to butanediol, CO2 and H2O, showing that esterase enzymes are involved in the DEHP biodegradation process (Ahuactzin-Pérez et al. 2016; González-Márquez et al. 2019a).

Fungi from the genus Fusarium are plant pathogens of agricultural crops (Aoki et al., 2014). Several approaches are now being exploited to identify and remove pathogenicity genes in fungi (Van de Wouw and Howlett 2011). It has been successfully removed phytopathogenic genes of Ustilago maydis (Khrunyk et al. 2010) and new technologies such as the CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing system have been established for precise genome modification of fungi (Sánchez et al. 2020) such as the phytopathogenic Fusarium species (Schuster and Kahmann 2019). These new gene editing tools will enable accurate gene modifications for the elimination of fungal virulence from strains whose powerful enzymatic systems are used for pollutant degradation. On the other hand, cell-immobilized bioreactor systems have been found to be highly efficient in treating pollutant-containing wastewater (Kanaujiya et al., 2019). This could be an alternative approach for the removal of phthalate from wastewater by F. culmorum.

In this study, the effect of a high concentration of DEHP (1500 mg l−1) on the induction of esterase activity during its degradation by F. culmorum was studied under liquid fermentation conditions. Fungal growth, protein content and assessments of esterase activities by biochemical tests and zymographic assays were performed using both DEHP-containing medium (1500 mg l−1) and glucose medium (as a control).

Materials and methods

Fusarium culmorum Fc1-CICBUAT was obtained from the microbial collection from Centro de Investigación en Ciencias Biológicas (CICB) at the Autonomous University of Tlaxcala (UAT) (Tlaxcala, Mexico) for use in this study. This fungus was isolated from an industrial facility for recycling paper, where phthalates can be found as additives in paper dyes, inks and adhesives for paper envelopes (Aguilar-Alvarado et al. 2015). This strain is deposited at the Collection of the Mexico’s National Center for Genetic Resources (CNRG-INIFAP) (Jalisco, Mexico). A DEHP-containing medium was prepared containing the following components (l−1): 1.5 g DEHP (purity grade 99%; Sigma), 0.66 g Ca(NO3)2; 0.32 g K2HPO4, 0.12 g MgSO4·7H2O, 0.12 g KCl, and 0.01 g FeSO4·7H2O (with 100 µl of Tween 80). A control fermentation culture was performed using a glucose-containing medium containing the following components (l−1): 10 g glucose, 2.4 g Ca(NO3)2, 1.2 g K2HPO4, 0.46 g MgSO4·7H2O, 0.4 g KCl, and 0.01 g FeSO4·7H2O. The media were autoclaved for 15 min at 121 °C. Erlenmeyer flasks (125 ml) containing 50 ml of sterile culture medium were inoculated with a suspension of F. culmorum spores to a final concentration of 107 spores ml−1 as reported by González-Márquez et al. (2019a). Cultures were incubated with shaking at 120 rpm on an orbital shaker at 25 °C for 7 days. Samples were collected at 12-h intervals.

The mycelial biomass in the liquid cultures was collected by vacuum filtration and the specific growth rate (µ) and yield parameters were estimated as reported by Ahuactzin-Pérez et al. (2016). The protein content of samples was quantified using a Bradford assay (Bradford 1976), where 200 µl of Bradford reagent (BIORAD) was added to 100 μl of supernatant and 700 μl of sterile distilled water, mixed, and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. The absorbance of the solutions was measured at 595 using a spectrophotometer UNICO (S-2150 series Dayton, NJ, USA).

Esterase activity was quantified in the supernatant using p-nitrophenyl butyrate (pNPB) as substrate according to Ferrer-Parra et al. (2018). The esterase yield per unit of biomass (YE/X), esterase productivity (P), maximal enzymatic activity (Emax), and specific rate of enzyme production (qp) were estimated as previously described (Ahuactzin-Pérez et al. 2016). One unit enzyme activity (U) was defined as the amount of activity required to release 1 μmol of ρ-nitrophenol per min from pNPB under the assay conditions. Volumetric and esterase specific activities were expressed in U l−1 and U mg−1 of protein, respectively. The polypeptide profiles with esterase activity were determined using polyacrylamide gels (PAGE) (Leammli 1970). Esterase activity was assayed by zymography according to Ferrer-Parra et al. (2018). Briefly, samples were loaded on 20% separating and 4% stacking PAGE gels and electrophoresed under non-reducing conditions. After electrophoresis, the gels were washed and then incubated overnight at 25 °C in a substrate buffer. ProteinTM Dual Precision Xtra Plus Standards (BIORAD) was used as molecular markers. The gels were imaged using a Gel Doc EZ Imager (BIORAD), and bands in the lanes were assessed for their densities using Image Lab Version 6.0.0 (BIORAD).

All assays were performed in triplicate, and the values are presented as the means ± SD. Statistical analyses were conducted using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test using SigmaPlot version 12.0 (Systat Software Inc, San Jose, CA, USA).

Results and discussions

The biomass production of F. culmorum in DEHP-containing medium and in control (glucose-containing) medium is shown in Fig. 1. The fungus attained the stationary phase after 72 and 108 h in the DEHP-containing and control media, respectively (Fig. 1). The Xmax value was higher in the control medium than in DEHP-containing medium, although the highest µ and YX/S values were observed in the medium added with DEHP (Table 1). Córdoba-Sosa et al. (2014) reported the growth of P. ostreatus in medium added with 1500 mg of DEHP l−1 under liquid fermentation conditions and observed that it reached the stationary phase after 360 h of growth. Aguilar-Alvarado et al. (2015) studied the growth of filamentous fungi (five different species) on DEHP-containing agar and observed that F. culmorum produced greater amounts of biomass than other fungi in medium added with 1500 mg of DEHP l−1. Ahuactzin-Pérez et al. (2016) observed that F. culmorum attained the stationary phase after approximately 96 h of growth in DEHP-containing medium (1000 mg l−1) that had glucose as an added substrate. The results of the present work showed that F. culmorum was able to grow on a high concentration of DEHP (1500 mg l−1) as only carbon source and it did not require glucose as cosubstrate.

Fig. 1.

Growth curves of F. culmorum in glucose (Δ) and in 1500 mg of DEHP l−1 (□) in liquid fermentation. Biomass production was higher in glucose (Δ) than in DEHP-containing medium (□). Biomass curves were fitted (—) using the logistic equation (Ahuactzin-Pérez et al. 2016)

Table 1.

Specific growth rate and growth parameters of F. culmorum grown in glucose medium and DEHP-containing medium in liquid fermentation

| Parameter | Glucose-containing medium | DEHP-containing medium |

|---|---|---|

| µ (h−1) | 0.04b ± 0.001 | 0.06a ± 0.002 |

| Xmax (g l−1) | 1.84a ± 0.01 | 1.08b ± 0.02 |

| YX/S (gX gS−1) | 0.18b ± 0.003 | 0.72a ± 0.002 |

Values are mean ± SEM (n = 3)

a, bMeans in a row without a common superscript letter differ (P < 0.05) as analyzed by one-way ANOVA and the Tukey’s test

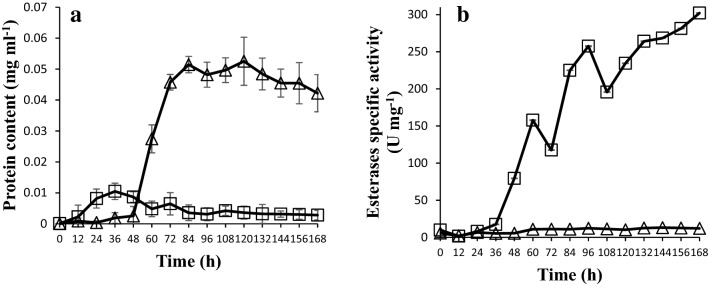

The protein content was greater in glucose-containing medium than in DEHP-containing medium after 48 h (Fig. 2a). However, the observed values for esterase specific activities and esterase yield parameters were greater in the DEHP-containing medium than in the control medium (Fig. 2b, Table 2). In general, esterase specific activity increased after 36 h, achieving the highest activity after 168 h in DEHP-containing medium (Fig. 2b). After observing low esterase specific activity in glucose-containing medium during the first 48 h, the activity slightly increased after 60 h and remained almost unchanged during the course of the fermentation (Fig. 2b). Compared to the glucose-containing medium, the Emax, YE/X, P and qp values were approximately 1.4-, 2.4-, 1.5- and 3.5-fold higher in DEHP-containing medium, respectively (Table 2). These results demonstrated that DEHP induced esterase activity in F. culmorum. Previous studies also observed esterase induction in P. ostreatus and F. culmorum grown in DEHP-containing medium added with glucose as cosubstrate (Ahuactzin-Pérez et al. 2016). Ferrer-Parra et al. (2018) studied esterase activity in F. culmorum in DEHP-containing medium (with 1500 mg l−1) using NaNO3 as nitrogen source. In the present study, more than threefold higher esterase activity (845.8 U l−1) was found using Ca(NO3)2 as nitrogen source than that previously demonstrated (242.4 U l−1) (Ferrer-Parra et al. 2018). It has been reported that Bacillus sp showed about twice as high amylase activity in medium added with CaCl2 that in medium added with NaCl, suggesting that the ion Ca++ enhanced the enzyme activity (Saxena and Singh 2011).

Fig. 2.

Protein content (a) and esterase specific activity (b) of F. culmorum grown in glucose-containing medium (Δ) and in 1500 mg of DEHP l−1 (□) in liquid fermentation conditions. The protein content was greater in the control medium (Δ) than in the DEHP-containing medium (□) after 48 h (a). However, the esterase specific activities were higher in the DEHP-containing medium (□) than in the control medium (b)

Table 2.

Esterase yields of F. culmorum grown in glucose medium and DEHP-containing medium in liquid fermentation

| Esterase yields | Glucose-containing medium | DEHP-containing medium |

|---|---|---|

| Emax (U l−1) | 606.8b ± 3 | 845.8a ± 8 |

| YE/X (U gX−1) | 329.8b ± 4 | 783.1a ± 9 |

| qp (U gX−1 h−1) | 13.2b ± 0.02 | 47.0a ± 0.03 |

| P (U l−1 h−1) | 4.6b ± 0.003 | 7.04a ± 0.002 |

Values are mean ± SEM (n = 3)

a, bMeans in a row without a common superscript letter differ (P < 0.05) as analyzed by one-way ANOVA and the Tukey’s test

Fan et al. (2018) reported that a hydrolase (harboring a catalytic triad conserved in esterases/hydrolases) from Gordonia sp. YC-JH1 that was heterologously expressed in Escherichia coli was able to degrade 70–80% of DEHP (100 mg l−1) to phthalic acid within 24 h, with 3.14 U mg−1 protein observed as the highest specific activity. In the present study, the greatest specific activity observed was 302 U mg−1 of protein (Fig. 2b). González-Márquez et al. (2019a) reported the degradation of 92% of DEHP (1000 mg l−1) by F. culmorum to butanediol, CO2 and H2O within 36 h, showing an enhanced specific esterase activity at 72 h. In the present study, F. culmorum had an enhanced specific esterase activity after 48 h and until the end of the fermentation period at 168 h, exhibiting an approximately 1.3-fold higher volumetric esterase activity in DEHP-containing medium (606.8 U l−1; Table 2) than that observed in previous studies (483 U l−1) (González-Márquez et al. 2019a). Furthermore, the results of the present study show that 1500 mg of DEHP l−1 did not inhibit the growth of the fungus, but a high concentration of DEHP enhanced the fungal esterase activity.

Figure 3 shows the esterase zymogram of F. culmorum grown in glucose-containing medium. Two bands with esterase activity were detected after 12 h and were observed throughout the fermentation period (25.4 and 30.5 kDa). The esterase zymogram of F. culmorum grown in DEHP-containing medium is shown in Fig. 4. The addition of DEHP (1500 mg l−1) to the culture medium induced the production of five esterase isoforms (26.4, 31.7, 43, 73.6 and 125 kDa), which were clearly observed after 48 h and until at the end of the fermentation period (168 h). Three esterase isoforms were observed at 24 h (26.4, 31.7 and 73.6 kDa), while four (26.4, 31.7, 73.6 and 125 kDa) were clearly observed at 36 h. These results show that esterase enzymes produced by F. culmorum in medium added with DEHP are different in abundance and molecular weight to those that were constitutively produced in glucose-containing medium. González-Márquez et al. (2019b) reported that the addition of different concentrations of apple cutin (0.2, 2 and 20 g l−1) to the culture medium induced the production of two esterase (cutinase) isoforms (65 and 90 KDa) in F. culmorum. Studies on dimethyl terephthalate degradation showed that Fusarium sp. produced an esterase of approximately 84 kDa (Luo et al. 2012). In addition, Zhang et al. (2014) reported on an esterase of 34.1 kDa from Sulfobacillus acidophilus was heterologously expressed in E. coli and was able to degrade several phthalates to their corresponding monoesters, although it was unable to degrade dicyclohexyl phthalate and DEHP due to the complex structures of these phthalates. Furthermore, Fan et al. (2018) reported that a hydrolase (harboring a catalytic triad conserved in esterases/hydrolases) of approximately 50 kDa from Gordonia sp. YC-JH1 that was heterologously expressed in E. coli was able to degrade DEHP (100 mg l−1) to phthalic acid. González-Márquez et al. (2019a) reported that eight esterase isoforms (24.9, 34.7, 35.9, 40.6, 47.8, 52.7, 94.1 and 166.1 kDa) were detected during the degradation of DEHP (1000 mg l−1) by F. culmorum using NaNO3 as nitrogen source in liquid fermentation.

Fig. 3.

Detection of esterase activity of F. culmorum grown in glucose-containing medium by zymography. Two bands with esterase activity (25.4 and 30.5 kDa) were detected after 12 h and were observed throughout the fermentation period. Numbers at the bottom of the gel indicate fermentation time (h)

Fig. 4.

Detection of esterase activity of F. culmorum grown in 1500 mg of DEHP l−1 by zymography. Five bands with esterase activity (26.4, 31.7, 43, 73.6 and 125 kDa) were detected after 48 h and were observed throughout the fermentation period. Numbers at the bottom of the gel indicate fermentation time (h)

Conclusion

Fusarium culmorum has great potential for use in the restoration of sites contaminated with high concentrations of DEHP and even of other phthalates with less complex structures. It is crucial to increase the enzymatic activity levels to accelerate the complete biodegradation of DEHP. These results showed that a high DEHP concentration (1500 mg l−1) using Ca(NO3)2 as nitrogen source enhanced esterase activity in F. culmorum and that the presence of several esterase isoforms depends on the concentration of DEHP and nitrogen source present in the medium. Studies performing detailed characterizations of esterases produced by F. culmorum in DEHP-containing medium need to be carried out to promote the practical application of phthalate biodegradation to decrease the negative impacts of these compounds in the environment.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the Council for Science and Technology from Mexico (CONACyT) to carry out this research (Project No. 1549; Fronteras de la Ciencia). CONACyT also provides funding for doctoral studies (No. 555469) to AGM.

Author contributions

AGM did the experimental work (PhD thesis). OLC and GV-G co-supervised AGM PhD thesis and checked the MS. CS co-supervised AGM PhD thesis and wrote the MS. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest in the publication.

References

- Aguilar-Alvarado Y, Báez-Sánchez MR, Martínez-Carrera D, Ahuactzin-Pérez M, Cuamatzi-Muñoz M, Sánchez C. Mycelial growth and enzymatic activities of fungi isolated from recycled paper wastes grown on di (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate. Pol J Environ Stud. 2015;24:1897–1902. doi: 10.15244/pjoes/58808. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahuactzin-Pérez M, Tlecuitl-Beristain S, García-Dávila J, González-Pérez M, Gutiérrez-Ruíz MC, Sánchez C. Degradation of di(2-ethyl hexyl) phthalate by Fusarium culmorum: Kinetics, enzymatic activities and biodegradation pathway based on quantum chemical. Sci Total Environ. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.05.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki T, O’Donnell K, Geiser DM. Systematics of key phytopathogenic Fusarium species: current status and future challenges. J Gen Plant Pathol. 2014;80(3):189–201. doi: 10.1007/s10327-014-0509-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bope AM, Haines SR, Hegarty B, Weschler CJ, Peccia J, Dannemiller KC. Emerging investigator series: degradation of phthalate esters in floor dust at elevated relative humidity. Environ Sci Proc Imp. 2019;21:1268–1279. doi: 10.1039/c9em00050j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Córdoba-Sosa G, Torres JL, Ahuactzin-Pérez M, Díaz-Godínez G, Díaz R, Sánchez C. Growth of Pleurotus ostreatus ATCC 3526 in different concentrations of di (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate in liquid fermentation. JCBPS. 2014;4:96–103. [Google Scholar]

- Fan S, Wang J, Yan Y, Wang J, Jia Y. Excellent degradation performance of a versatile phthalic acid esters-degrading bacterium and catalytic mechanism of monoalkyl phthalate hydrolase. Int J Mol Cell Med. 2018;19(9):2803. doi: 10.3390/ijms19092803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer-Parra L, López-Nicolás DI, Martínez-Castillo R, Montiel-Cina JP, Morales-Hernández AR, Ocaña-Romo E, González-Márquez A, Portillo-Ojeda M, Sánchez-Sánchez DF, Sánchez C. Partial characterization of esterases from Fusarium culmorum grown in media supplemented with di (2-ethyl hexyl phthalate) in solid-state and liquid fermentation. Mex J Biotechnol. 2018;3(1):82–94. doi: 10.29267/mxjb.2018.3.1.83. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gónzalez-Márquez A, Loera-Corral O, Santacruz-Juárez E, Tlécuitl-Beristain S, García-Dávila J, Viniegra-González G, Sánchez C. Biodegradation patterns of the endocrine disrupting pollutant di (2-ethyl hexyl) phthalate by Fusarium culmorum. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2019;170:293–299. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2018.11.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gónzalez-Márquez A, Loera-Corral O, Viniegra-González G, Sánchez C. Production of cutinolytic esterase by Fusarium culmorum grown at different apple cutin concentrations in submerged fermentation. Mex J Biotechnol. 2019;4(4):50–64. doi: 10.29267/mxjb.2019.4.4.50. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Green Facts (2008) Facts on health and the environment. https://www.greenfacts.org/en/dehp-dietylhexyl-phthalate/l-2/3-effects-environment.htm#3. Accessed 19 Jun 2020

- Guerranti C, Martellini T, Fortunati A, Scodellini R, Cincinelli A. Environmental pollution from plasticiser compounds: do we know enough about atmospheric levels and their contribution to human exposure in Europe? Curr Opin Environ Sci Health. 2019;8:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.coesh.2018.10.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hahladakis JN, Velis CA, Weber R, Lacovidou E, Purnell P. An overview of chemical additives present in plastics: migration, release, fate and environmental impact during their use, disposal and recycling. J Hazard Mater. 2018;344:179–199. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanaujiya DK, Paul T, Sinharoy A, Pakshirajan K. Biological treatment processes for the removal of organic micropollutants from wastewater: a review. Curr Pollut Rep. 2019;5:112–128. doi: 10.1007/s40726-019-00110-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khrunyk Y, Munch K, Schipper K, Lupas AN, Kahmann R. The use of FLP-mediated recombination for the functional analysis of an effector gene family in the biotrophic smut fungus Ustilago maydis. New Phytol. 2010;187:957–968. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leammli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo ZH, Pang KL, Wu YR, Gu JD, Chow RK, Vrijmoed LL. Degradation of phthalate esters by Fusarium sp. DMT-5-3 and Trichosporon sp. DMI-5-1 isolated from mangrove sediments. Prog Mol Subcell Biol. 2012;53:299–328. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-23342-5_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Net S, Sempéré R, Delmont A, Paluselli A, Ouddane B. Occurrence, fate and behavior and ecotoxicological state of phthalates in different environmental matrices. Environ Sci Technol. 2015;49(7):4019–4035. doi: 10.1021/es505233b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Andres L, Díaz-Godínez R, Luna-Suárez S, Sánchez C. Characteristics and uses of phthalates. Mex J Biotechnol. 2017;2(1):145–154. doi: 10.29267/mxjb.2017.2.1.145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez C, Moore D, Robson G, Trinci T. 21st Century miniguide to fungal biotechnology. Mex J Biotechnol. 2020;5(1):11–42. doi: 10.2967/mxjb.2020.5.1.11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena R, Singh R. Amylase production by solid-state fermentation of agro-industrial wastes using Bacillus sp. Braz J Microbiol. 2011;42(4):1334–1342. doi: 10.1590/s1517-83822011000400014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster M, Kahmann R. CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing approaches in filamentous fungi and oomycetes. Fungal Genet Biol. 2019;130:43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2019.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Wouw AP, Howlett BJ. Fungal pathogenicity genes in the age of 'omics'. Mol Plant Pathol. 2011;12(5):507–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2010.00680.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang T, Ren L, Jia Y, Fan S, Wang J, Nahurira R, Wang H, Yan Y, Wang Y. Biodegradation of di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate by Rhodococcus ruber YC-YT1 in contaminated water and soil. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:964–984. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15050964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XY, Fan X, Qiu YJ, Li CY, Xing S, Zheng YT, Xu JH. Newly identified thermostable esterase from Sulfobacillus acidophilus: properties and performance in phthalate ester degradation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80(22):6870–6878. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02072-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]