Abstract

Pheochromocytomas (PCC) and paragangliomas (PGL) are rare neuroendocrine tumors. Head and neck paragangliomas (HNPGL) can be categorized into carotid body tumors, which are the most common, as well as jugular, tympanic, and vagal paraganglioma. A review of the current literature was conducted to consolidate knowledge concerning PGL mutations, familial occurrence, and the practical application of this information. Available scientific databases were searched using the keywords head and neck paraganglioma and genetics, and 274 articles in PubMed and 1183 in ScienceDirect were found. From these articles, those concerning genetic changes in HNPGLs were selected. The aim of this review is to describe the known genetic changes and their practical applications. We found that the etiology of the tumors in question is based on genetic changes in the form of either germinal or somatic mutations. 40% of PCC and PGL have a predisposing germline mutation (including VHL, SDHB, SDHD, RET, NF1, THEM127, MAX, SDHC, SDHA, SDHAF2, HIF2A, HRAS, KIF1B, PHD2, and FH). Approximately 25–30% of cases are due to somatic mutations, such as RET, VHL, NF1, MAX, and HIF2A. The tumors were divided into three main clusters by the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA); namely, the pseudohypoxia group, the Wnt signaling group, and the kinase signaling group. The review also discusses genetic syndromes, epigenetic changes, and new testing technologies such as next-generation sequencing (NGS).

Keywords: pheochromocytoma, paraganglioma, head and neck neoplasms, head and neck tumors, genetic syndromes, mutations

1. Introduction

Pheochromocytomas (PCC) and paragangliomas (PGL) are rare neuroendocrine tumors originating from either adrenomedullary chromaffin cells (PCCs); sympathetic ganglia of the thorax (T-PGL); or abdominal (A-PGL), pelvic, or parasympathetic ganglia in the head and neck (HNPGL) [1,2]. They are referred to collectively as PPGL. PCCs typically secrete one or more than one catecholamine: epinephrine, norepinephrine, and dopamine [1], while PGLs in most cases are non-secretory [1,3,4,5]. PCC represent 80% to 85% of chromaffin-cell tumors, and PGL represent 15% to 20% [6]. These tumors are characteristically well-vascularized and typically benign; nonetheless, roughly 10–15% may metastasize to the lungs, bone, liver, and lymph nodes. They most frequently occur between the third and sixth decades of life and present more commonly in women [7]. HNPGL can be categorized into carotid body tumors, which are the most common, as well as jugular, tympanic, and vagal paraganglioma. Other rare locations include the larynx, thyroid gland, parathyroid gland, nose, paranasal sinuses, parotid gland, or orbit [8]. PGL have also been described in the urogenital system, in the spermatic cord in particular [9]. Clinical symptoms vary according to the location and size of the tumor. Carotid body tumors typically produce a painless, slow-growing neck mass [10,11] that may eventually cause dysphagia and cranial nerve disorders. In contrast, pulsatile tinnitus and conductive hearing loss are characteristic of tympanic paraganglioma [12].

Neuroendocrine tumors show the highest degree of heritability in all neoplasms (approximately 40–50%) [13,14,15,16,17]. The first reports of the familial occurrence of PGL date from 1933, when carotid paragangliomas were first described by Chase [18,19]. In recent years, it has been confirmed that more than one-third of these tumors are genetically determined [20]. Today, the planning of further treatment considers family history, the extent and location of the tumor, its genetic origin, and the molecular pathways involved, especially as genetic testing becomes increasingly available and consistently improves the efficacy of therapy [3]. When a mutation is detected in a susceptibility gene such as VHL, SDH, or the recently discovered MDH2, a search for common co-occurring tumors is indicated [20,21]. Mutation in the SDHB subunit is also associated with the risk for malignancy and worse prognosis [3,10,22,23]. In 50% of patients with metastatic disease, a mutation in the SDHB gene was found. In the remaining 50% of cases, the genetic factors of the malignancy are still unidentified [23]. With this knowledge, genetic testing of PGL and the testing of first-degree family members should be routinely implemented to diagnose low-grade tumors [24]. Therefore, we aim to comprehend and conclude the most recent knowledge surrounding mutations in PGL, family occurrence, and their practical application based on the current literature and the paradigm of diagnostics.

2. Results

The outcomes are presented in the form of a literature review, structured by thematic subsections concerning the classification of head and neck paragangliomas with regard to genetic and molecular changes (based on 21 papers), as well as elucidation of genetic syndromes (based on 19 publications). Moreover, the review presents new methods as they pertain to the investigation of these tumors, such as investigation of epigenetic patterns or the application of new advanced molecular tools like next-generation sequencing (NGS) (based on five publications).

The details concerning the content of the presented articles (materials, methods, and conclusions) are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The table includes details concerning the content of the presented articles (authors, year of publication, number of patients in the study, reported genes, and most significant findings). Only data from original papers are included; no reviews are considered.

| Author, Year | No. of Patients | Genes | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Niemann et al. (2001) [25] | Five patients with histologically proven paraganglioma (single family members) and one patient (of this family) with imaging findings consistent with a PGL. 33 family members were clinically unaffected. | SDHC gene location | The disease locus in PGL3 was determined to be located at 1q21-q23. |

| Mannelli et al. (2009) [26] | 501 patients with PCC and/or PGL 160 patients under 50 years of age whose DNA sequencing results revealed wild-type RET, VHL, SDHB, SDHC, and SDHD were subsequently analyzed for genomic rearrangements involving the VHL gene or one of the SDH genes. |

RET VHL SDHD SDHB SDHC Genomic rearrangements (total deletion of the SDHD gene) |

Detection of germinal mutations (such as VHL, RET, NF1, SDHB, SDHC and SDHD) in 32.1% of cases. From 100% in patients with associated lesions to 11.6% in patients with a single tumor. Genomic rearrangements were found in two of 160 patients (1.2%), both involving total deletion of the SDHD gene. |

| Bayley et al. (2010) [27] | 443 patients with apparently sporadic PCC/PGL who did not have mutations in SDHD, SDHC, or SDHB. Examination of a Spanish family with HNPGL presenting with a young age of onset. |

SDHAF2 | No germinal (315 patients) or somatic (128 patients) mutations, and no germinal deletions of the SDHAF2 gene were found. After pedigree analysis of a Spanish family with HNPGL a pathogenic mutation in SDHAF2 was found that resulted in an amino acid substitution (p.Gly78Arg). The same mutation was noted previously in a Dutch kindred. |

| Kunst et al. (2011) [28] | 57 family members. | SDHAF2 | Establishing a correlation between HNPGL occurrence (based on phenotypic analysis) and SDHAF2 mutation. The mutation carriers showed early onset of the disease and high levels of multifocality. |

| Casey et al. (2014) [29] | 31 patients with confirmed PCC/PGL. |

TMEM127

SDHAF2 RET |

The occurrence of TMEM127, SDHAF2 and RET mutations was found in patients without indications for genetic testing based on phenotypic evaluation. |

| Fishbein et al. (2015) [23] | Stage 1: whole exome sequencing on a discovery set of 21 patients with PCC/PGL. Stage 2: targeted sequencing of a separate validation set of 103 patients withPCC/PGL. |

NF1

ATRX |

Mutations in NF1 were detected in 42% of tumors. In 28% of SDHB-related tumors, deleterious variants of ATRX were found (PP119F1 p.W2275* and PP098F2 p.R2197H). ATRX protein was not detected in tumor cells by immunohistochemistry. The study found somatic mutation of ATRX in 12.6% of cases; 30% of them had truncating mutations and 69% missense mutations, classified as deleterious. |

| Luchetti et al. (2015) [30] | 85 patients: PCC 60, PGL 5, HNPGL 20. |

HRAS

BRAF |

Missense mutation was found in six cases (PCC = 6/60, PGL = 0/5, and HNPGL = 0/20) in HRAS in the hotspot region of codon 13 and 61. In one case of PCC, an activating BRAF mutation was found. In two patients a missense mutation was identified in the tetramerization domain of TP53 protein. |

| Fishbein et al. (2017) [31] | 173 patients with PCCs/PGLs. |

SDHB, RET, WHL, NF1, SDHD, MAX EGLN1 (PHD2), TMEM127, CSDE1, HRAS, EPAS1, MAML3, BRAF, NGFR |

27% of patients had germinal mutations (including SDHB 9%, RET 6%, VHL 4%, and NF1 3%). SDHD, MAX, EGLN1 (PHD2), and TMEM127 mutations were found in less than 2% each. CSDE1 was identified as a somatically mutated driver gene complementary to the other four known drivers (HRAS, RET, EPAS1, and NF1). MAML3, BRAF, NGFR, and NF1 fusion genes were discovered. |

| Bausch et al. (2017) [32] | 972 unrelated patients without mutations in the classic PCC/PGL associated genes. |

SDHA, TMEM127, MAX, SDHAF2 |

Six percent of patients were mutation carriers (including SDHA, TMEM127, MAX, and SDHAF2). 91% of patients had familial, multiple, extra-adrenal, and/or malignant tumors and/or had younger age of onset. Extra-adrenal tumors occurred in 48% of mutation carriers and in 79% of carriers with HNPGL. |

| Chen et al. (2017) [22] | 37 patients with HNPGLs. |

SDHD

SDHB SDHAF2 |

SDHD gene mutations were found in: the Chinese founder mutation (c.3G>C, p.Met1Ile) in six cases, a missense mutation (c.284T>C, p.L95P) in one case, an in-frame deletion (c.278–280delATT, p.Y93S) in one case. A missense SDHB mutation (c.647A>G) and a nonsense SDHAF2 mutation (c.130C>T, p.Gln44Ter) were found in two cases. Frequent methylation was observed in six of the TSGs tested (HIC1, DcR1, DcR2, DR4, DR5, and CASPS8). Four of them (HIC1, DcR1, DcR2 and CASPS8) showed more frequent mutations in SDH-associated HNPGL than in non-mutated ones. |

| Calsina et al. (2018) [21] | 830 patients with PPGLs, negative for the main PPGL driver genes. | MDH2 | Twelve heterozygous variants of MDH2 were found (five of the 12 were missense (41.7%), one synonymous (8.3%), four were located in the intronic region (33.3%), one was an in-frame deletion (8.3%), and one affected a donor splice-site (8.3%). Five of these were unreported variants. The study showed the functional impact of two variants (p.Arg104Gly and p.Lys314del) and suggests altered molecular function of two variants (p.Val160Met and p.Ala256Thr). |

| Ding et al. (2019) [33] | 23 cases of multiple HNPGL. |

SDHD, SDHB, SDHC, SDHAF2, VHL, RET |

Family 1: 12 SDHD mutations (8 bilateral carotid body tumor (CBT) with 1 bilateral malignant CBT) Family 2: 3 SDHD mutations (1 bilateral CBT, 2 unilateral CBT) Family 3: 2 cases of SDHD mutations (vagus PGL and pheochromocytoma) Other patients: sporadic manifestations (5 cases SDHD gene mutation, 1 case RET gene mutation). Two novel mutations were found: c.387–393del7 mutation of SDHD gene and c.3247A>G mutation of RET gene. More frequent occurrence of SDHD mutations was found in patients and family members with multiple HNPGL. |

2.1. Classification Based on the Genetic and Molecular Background

Germinal mutations occur in the germ line and are passed on to all cells of the developing body [34]. A germline predisposing mutation is found in approximately 40% of PCCs and PGLs in one of at least 12 genes (VHL, SDHB, SDHD, RET, NF1, THEM127, MAX, SDHC, SDHA, SDHAF2, HIF2A, HRAS, KIF1B, PHD2, FH). The second type of genetic alteration is classified as somatic. These occur later in life, affecting only a single cell of a particular tissue, and give rise to the development of a specific neoplasm. Somatic mutations of RET, VHL, NF1, MAX, and HIF2A account for 25–30% of these tumors [13,16,23,32,33,35,36].

PGLs are classified into three clusters by the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) on the basis of molecular, cytogenetic abnormalities, and specific single-nucleotide causative mutations, which led to the development of PPGLs. Moreover, contributing genes are grouped according to their biological activity—namely, the pseudohypoxia group, the Wnt signaling group, and the kinase signaling group. This division into groups with different clinical, imaging, molecular, and biochemical features allows for the personalization of patient care as well as the development of new screening and treatment guidelines [14,35,37,38].

The pseudohypoxia group can be further divided into two subgroups. The first comprises tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA)-related factors concerning 10–15% of PPGLs. This group includes germline mutations in succinate dehydrogenase subunits SDHA, SDHB, SDHC, SDHD or SDHAF2 (SDHx)—succinate dehydrogenase complex assembly factor 2, and FH (a second enzyme in the TCA cycle). The second subgroup encompasses VHL/EPAS1-related genes and accounts for 15–20% of PPGLs [14,35,37,38,39,40].

Activation of hypoxia inducible factors (HIFs) is a mutual characteristic for this cluster. HIFs are released in physiological response to cellular hypoxia. A pseudo-hypoxic state is caused by the presence of abnormal, mutated VHL, SDH, EGLN1, and HIF2A genes. The effect of this is constant activation of HIF pathways in the cell despite normal oxygen levels. This condition causes epigenetic changes in HIF target genes, which affects many processes including proliferation, angiogenesis, migration, apoptosis, and invasion. These events may all contribute to PPGL formation [19,35,38,41,42,43,44].

The Wnt signaling cluster is another group that are, in particular, triggered by somatic mutations in the CSDE1 gene or somatic gene fusions which affect the MAML3 gene. This results in the activation of Wnt and Hedgehog signaling pathways. Patients with sporadic PPGLs (5–10% of all PPGLs) are grouped here. Many developmental processes such as proliferation, cell polarity, adhesion, or differentiation are regulated by the Wnt pathway. As a result, these tumors are considered more aggressive, recur significantly, and are often prone to metastases [14,31,37,38,39,45].

The kinase signaling cluster (50–60% of PPGLs) includes germline or somatic mutations in RET, NF1, MAX, HRAS, and TMEM127 genes [14,37]. The RAS/MAPK and PI3/AKT signaling pathways are enabled due to RET proto-oncogene activation or NF1 tumor suppressor inactivation, resulting in tumor formation. In contrast, TMEM127 mutations trigger the mTOR pathways. Another mechanism includes deactivation of the MAX suppressor gene, causing an abnormally elevated expression of cofactor MYC (proto-oncogene), resulting in the formation of PPGLs [14,38,39,40,41,43,44].

Several genetic syndromes are associated with PPGL: Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (MEN2), Neurofbromatosis type 1 (NF1), Von Hippel–Lindau (VHL) disease, and Hereditary paraganglioma syndrome (PGL 1, PGL2, PGL3 and PGL4) [46,47].

HNPGL are very rare in NF1, MEN 2, and VHL patients. Rather, they display a predisposition toward the development of PCCs.

2.2. Genetic Syndromes

HNPGL are a solid manifestation in hereditary paraganglioma syndromes. They are caused by mutations in the succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) complex, which is necessary for the mitochondrial electron transport chain and ATP generation. This compound is composed of four subunits (A-D) with SDHAF2 stabilizing the entire complex. Subunits B, C, and D are strongly correlated with PCCs and PGLs [8,12,14,26,35,42,46,47,48].

PGL1 syndrome is an autosomal dominant disease linked to HNPGLs. It is correlated with inactivating mutations of the SDHD gene localized on chromosome 11q23. PCCs and sympathetic PGLs occur in 40% of cases, and bilateral or multifocal tumors are present in approximately 74% of patients. Though these tumors are typically not malignant, they have a tendency toward recurrence [14]. SDHD mutations are also associated with maternal genomic imprinting. Tumors are more likely to develop in children if the father is affected or a mutation carrier himself. If the mutation is inherited from the mother, it is inactivated but still genetically transmitted [8,12,15,35,41,47,49].

PGL4 syndrome also arises from a mutation with an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance, is responsible for inactivating the SDHB gene located on 11p35. In this condition, the following symptoms are reported: sympathetic extra-adrenal PGLs, PCCs, and HNPGLs. In up to 70% of all cases of PGL4 syndrome, the tumors are malignant [13]. PGLs typically produce catecholamines such as dopamine and norepinephrine, and only 10% of SDHB mutated tumors are biochemically silent; however, the clinical consequences are generally the result of significant mass effect rather than catecholamine excess. Typical tumor localizations include the abdomen and the mediastinum. The SDHB gene mutation increases the risk of renal cell carcinoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), and breast and papillary thyroid carcinoma, and while patients with metastatic disease should be routinely tested for the presence of the predisposing SDHB mutation, there are no guidelines regarding the screening of asymptomatic SDHx gene mutation carriers. Experts do suggest annual biochemical screening for PCC/PGLs from between the ages of five and 10, as well as full-body MRI screening for all associated tumor types every 2–5 years [8,12,14,35,41,47,49].

PGL3 syndrome is caused by an SDHC gene mutation located on 1q21-q23 and is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern. PGL3 is associated with the occurrence of benign HNPGL, sympathetic PGL, and PCC and is typically multifocal. Metastases of these tumors is exceedingly rare [8,25,42,47,49,50].

Mutations in the SDHAF2 gene have also been recently reported. SDHAF2 mutation results in a rare type of familial paraganglioma syndrome that leads to HNPGL, but only in the children of a father who is a carrier of the defective gene. This syndrome is transmitted in an autosomal dominant manner, and usually manifests in the third decade of life. Genetic screening of SDHAF2 mutation is crucial in patients with HNPGL with suspicious family history, young age of onset, or multiple tumors and have already tested negative for SDHB, SDHC, and SDHD mutations [27,28,29,37,46,47].

2.3. Epigenetic Patterns in HNPGL

Epigenetic changes are gene modifications that do not change the DNA sequence but affect gene activity. Most often the changes include methylation—the addition of a methyl group to the DNA strand—which results in the switching off or silencing of the gene and subsequent altered protein production. Other types of epigenetic modification include acetylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitylation, and sumoylation. Some of these changes can be inherited [51]. However, the most frequent of all epigenetic markers in DNA is cytosine methylation. This change in the human genome is referred to as “CpG methylation” or “DNA methylation” [52]. Inactivation of tumor-suppressor genes (TSGs) is caused by overall DNA hypomethylation and hypermethylation of CpG islands located in the closest vicinity of the promoter. Tumorigenesis of HNPGL is not yet fully explained, and the search for new genetic as well as epigenetic changes is ongoing.

In a study by Chen et al. [22], the methylation status of a panel of TSGs (p16, HIC1, DcR1, DcR2, DR4, DR5, CASP8, HSP47, MGMT, and RASSF1A) has been determined and compared in HNPGLs with and without SDH mutations. A correlation between the methylation index (MI) and the presence of germline mutations was observed. Six out of 10 TSGs showed frequent methylation: HIC1 and those involved in the apoptosis pathway DcR1, DcR2, DR4, DR5, and CASPS8. More frequent methylation in SDH-related HNPGLs compared to non-mutated analogues was observed in four analyzed TSGs (CASPS8, HIC1, DcR1, and DcR2).

2.4. Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS)

Most of the studies conducted as of today have utilized conventional Sanger sequencing. Next-generation sequencing (NGS), in contrast to Sanger sequencing, enables broader and more accurate sequencing, leading to the detection of mutations in multiple genes. This technology allows for sample multiplication and also increases capacity and effectiveness, as well as reducing costs. Therefore, the use of NGS could provide the opportunity to test all patients at risk, rather than just a few selected targets [36]. It may provide a better understanding of the crucial role of the mutations acquired on various level of disease development, as well as those underlying the carcinogenesis of HNPGLs [53]. Luchetti et al. [30] analyzed 50 “mutation hotspot” variants in PCC and PGL using NGS in 20 patients with HNPGL and 85 patients with PPGL. The authors identified mutations in HRAS (7.1%), and BRAF (1.2%) as well as for TP53 in 2.35% of cases. In the group of PPGL tumors with identified hereditary mutations (21 cases), HRAS, BRAF, and TP53 genes were not mutated. It was concluded that the occurrence of HRAS/BRAF mutations predominates in sporadic PPGL (8.9%) but is inconsequential for inherited PPGL.

3. Materials and Methods

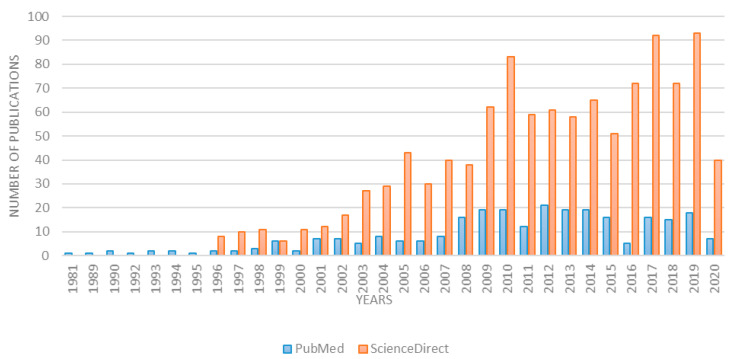

This study assumes a review of world scientific literature. An online search was conducted using the scientific databases PubMed and ScienceDirect applying the key words head and neck paraganglioma and genetics. The first resulting article in PubMed dated from 1981 and from 1996 in ScienceDirect. Over the last 10 years, the number of articles on the subject has doubled. While this review considers articles from the last 20 years, over 85% of them were published in the last 10 years. Detailed data concerning the number of articles in each year are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Number of publications according to key words head and neck paraganglioma and genetics.

In total, 274 articles containing the indicated keywords were found in PubMed and 1183 in ScienceDirect. Of these, only those from the last 20 years reporting genetic changes in head and neck paraganglioma were selected.

4. Conclusions

The conclusions of this review are based on the entire overview of the literature and may prove useful for the improvement of diagnostic and therapeutic schemes surrounding PCCs and PGLs. According to the article “Recommendations for Somatic and Germline Genetic Testing of Single Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma” [54], the study of germline DNA should be prioritized in head and neck paraganglioma and thorax paraganglioma. A strong recommendation for genetic testing—somatic as well as germline mutations, regardless of the age at diagnosis—is indicated. It is also strongly recommended even in patients with a negative family history, especially if the lesions occur at a young age and are multifocal [55]. Genetic testing is very effective for predicting the incidence of metastatic tumors. Numerous authors [3,56,57] have demonstrated the variability in the SDHB gene, which leads to metastatic disease in 40% or more of patients. An agreement in the literature on the selection of mutations in HNPGL has been drawn, and encompasses the following genes: SDHA, SDHB, SDHD, SDHAF2, SDHC, SDHB, VHL, FH, RET. These should be routinely determined in PGL patients. Different combinations of these genes should be tested depending on the availability of a tumor sample or the performance of SDHB-immunohistochemistry (SDHB-IHC).

To conclude, the diagnostic schedule in PGL should include the collection of clinical data including epidemiology, family history concerning neoplasms, the course of the disease (e.g., tumor growth rate), and/or its relapses. Radiological evaluation of the tumor consisting of imaging and angiography (assessment of tumor size, vascularization, localization, position relative to other structures, presence of metastases) should also be considered. Furthermore, in light of the expanding knowledge of the genetic basis of this disease, genetic testing concerning causative alterations has become increasingly important. A multidisciplinary team consisting of an ENT specialist, a radiologist, an endocrinologist, a nuclear medicine physician, and a geneticist can qualify the patient on the grounds of such information for further treatment and the management of follow-up.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jadzia Tin-Tsen Chou for language revision.

Author Contributions

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Science Centre, Poland, grant number 2019/33/N/NZ5/00872. The APC was funded by the National Science Centre, Poland, grant number 2019/33/N/NZ5/00872.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lenders J.W.M., Duh Q.-Y., Eisenhofer G., Gimenez-Roqueplo A.-P., Grebe S.K.G., Murad M.H., Naruse M., Pacak K., Young W.F. Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014;99:1915–1942. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koopman K., Gaal J., De Krijger R.R. Pheochromocytomas and Paragangliomas: New Developments with Regard to Classification, Genetics, and Cell of Origin. Cancers. 2019;11:1070. doi: 10.3390/cancers11081070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asban A., Kluijfhout W.P., Drake F.T., Beninato T., Wang E., Chomsky-Higgins K., Shen W.T., Gosnell J.E., Suh I., Duh Q.-Y. Trends of genetic screening in patients with pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: 15-year experience in a high-volume tertiary referral center. J. Surg. Oncol. 2018;117:1217–1222. doi: 10.1002/jso.24961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fishbein L. Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma: Genetics, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Hematol. Clin. 2016;30:135–150. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burnichon N., Rohmer V., Amar L., Herman P., Leboulleux S., Darrouzet V., Niccoli P., Gaillard D., Chabrier G., Chabolle F., et al. The Succinate Dehydrogenase Genetic Testing in a Large Prospective Series of Patients with Paragangliomas. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009;94:2817–2827. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lenders J.W.M., Eisenhofer G., Mannelli M., Pacak K. Phaeochromocytoma. Lancet. 2005;366:665–675. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67139-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boedeker C.C. Paragangliomas and paraganglioma syndromes. GMS Curr. Top. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2011;10 doi: 10.3205/cto000076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fishbein L., Nathanson K.L. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: Understanding the complexities of the genetic background. Cancer Genet. 2012;205:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergen.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun D., Yang P., Liu Y., Wang S. Paraganglioma of the spermatic cord: Report of one case and review of literature. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2020;13:1779–1786. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dorobisz K., Dorobisz T., Temporale H., Zatoński T., Kubacka M., Chabowski M., Dorobisz A., Krecicki T., Janczak D. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Difficulties in Carotid Body Paragangliomas, Based on Clinical Experience and a Review of the Literature. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. Off. Organ Wroc. Med. Univ. 2016;25:1173–1177. doi: 10.17219/acem/61612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Else T., Greenberg S., Fishbein L. Hereditary Paraganglioma-Pheochromocytoma Syndromes. In: Adam M.P., Ardinger H.H., Pagon R.A., Wallace S.E., Bean L.J., Stephens K., Amemiya A., editors. GeneReviews®. University of Washington; Seattle, WA, USA: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boedeker C.C., Hensen E.F., Neumann H.P., Maier W., Van Nederveen F.H., Suárez C., Kunst H.P., Rodrigo J.P., Takes R.P., Pellitteri P.K., et al. Genetics of hereditary head and neck paragangliomas. Head Neck. 2013;36:907–916. doi: 10.1002/hed.23436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dahia P.L.M. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma pathogenesis: Learning from genetic heterogeneity. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2014;14:108–119. doi: 10.1038/nrc3648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katabathina V.S., Rajebi H., Chen M.M., Restrepo C.S., Salman U., Vikram R., Menias C.O., Prasad S.R. Genetics and imaging of pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas: Current update. Abdom. Radiol. N. Y. 2020;45:928–944. doi: 10.1007/s00261-019-02044-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cavenagh T., Patel J., Nakhla N., Elstob A., Ingram M., Barber B., Snape K., Bano G., Vlahos I. Succinate dehydrogenase mutations: Paraganglioma imaging and at-risk population screening. Clin. Radiol. 2019;74:169–177. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2018.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turchini J., Cheung V.K.Y., Tischler A.S., Krijger R.R.D., Gill A.J. Pathology and genetics of phaeochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Histopathology. 2017;72:97–105. doi: 10.1111/his.13402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sen I., Young W.F., Kasperbauer J.L., Polonis K., Harmsen W.S., Colglazier J.J., DeMartino R.R., Oderich G.S., Kalra M., Bower T.C. Tumor-specific prognosis of mutation-positive patients with head and neck paragangliomas. J. Vasc. Surg. 2020;71:1602–1612.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2019.08.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chase W.H. Familial and bilateral tumours of the carotid body. J. Pathol. Bacteriol. 1933;36:1–12. doi: 10.1002/path.1700360102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin T.P., Irving R.M., Maher E.R. The genetics of paragangliomas: A review. Clin. Otolaryngol. 2007;32:7–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.2007.01378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burnichon N., Abermil N., Buffet A., Favier J., Gimenez-Roqueplo A.-P. The genetics of paragangliomas. Eur. Ann. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Dis. 2012;129:315–318. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Calsina B., Currás-Freixes M., Buffet A., Pons T., Contreras L., Letón R., Méndez I.C., Remacha L., Calatayud M., Obispo B., et al. Role of MDH2 pathogenic variant in pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma patients. Genet. Med. Off. J. Am. Coll. Med. Genet. 2018;20:1652–1662. doi: 10.1038/s41436-018-0068-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen H., Zhu W., Li X., Xue L., Wang Z.-Y., Wu H. Genetic and epigenetic patterns in patients with the head-and-neck paragangliomas associate with differential clinical characteristics. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2017;23:8812–8960. doi: 10.1007/s00432-017-2355-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fishbein L., Khare S., Wubbenhorst B., Desloover D., D’Andrea K., Merrill S., Cho N.W., Greenberg R.A., Else T., Montone K., et al. Whole-exome sequencing identifies somatic ATRX mutations in pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:6140. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muth A., Crona J., Gimm O., Elmgren A., Filipsson K., Askmalm M.S., Sandstedt J., Tengvar M., Tham E. Genetic testing and surveillance guidelines in hereditary pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. J. Intern. Med. 2018;285:187–204. doi: 10.1111/joim.12869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Niemann S., Becker-Follmann J., Nurnberg G., Rüschendorf F., Sieweke N., Hügens-Penzel M., Traupe H., Wienker T.F., Reis A., Muller U. Assignment of PGL3 to chromosome 1 (q21-q23) in a family with autosomal dominant non-chromaffin paraganglioma. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2001;98:32–36. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(20010101)98:1<32::AID-AJMG1004>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mannelli M., Castellano M., Schiavi F., Filetti S., Giacchè M., Mori L., Pignataro V., Bernini G., Giachè V., Bacca A., et al. Clinically Guided Genetic Screening in a Large Cohort of Italian Patients with Pheochromocytomas and/or Functional or Nonfunctional Paragangliomas. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009;94:1541–1547. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bayley J.-P., Kunst H.P., Cascón A., Sampietro M.L., Gaal J., Korpershoek E., Hinojar-Gutiérrez A., Timmers H.J., Hoefsloot L.H., Hermsen M.A., et al. SDHAF2 mutations in familial and sporadic paraganglioma and phaeochromocytoma. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:366–372. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kunst H.P.M., Rutten M.H., Hoefsloot L.H., Timmers H.J.L.M., Marres H.A., Jansen J.C., Kremer H., Bayley J.-P., Cremers C.W.R.J., De Mönnink J.-P. SDHAF2 (PGL2-SDH5) and Hereditary Head and Neck Paraganglioma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011;17:247–254. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Casey R., Garrahy A., Tuthill A., O’Halloran D., Joyce C., Casey M.B., O’Shea P.M., Bell M. Universal Genetic Screening Uncovers a Novel Presentation of an SDHAF2 Mutation. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014;99:E1392–E1396. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-4536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luchetti A., Walsh D., Rodger F., Clark G., Martin T., Irving R., Sanna M., Yao M., Robledo M., Neumann H.P.H., et al. Profiling of Somatic Mutations in Phaeochromocytoma and Paraganglioma by Targeted Next Generation Sequencing Analysis. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2015;2015:138573. doi: 10.1155/2015/138573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fishbein L., Leshchiner I., Walter V., Danilova L., Robertson A.G., Johnson A.R., Lichtenberg T.M., Murray B.A., Ghayee H.K., Else T., et al. Comprehensive Molecular Characterization of Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma. Cancer Cell. 2017;31:181–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bausch B., Schiavi F., Ni Y., Welander J., Patocs A., Ngeow J., Wellner U., Malinoc A., Taschin E., Barbon G., et al. Clinical Characterization of the Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma Susceptibility Genes SDHA, TMEM127, MAX, and SDHAF2 for Gene-Informed Prevention. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1204–1212. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ding Y., Feng Y., Wells M., Huang Z., Chen X. SDHx gene detection and clinical Phenotypic analysis of multiple paraganglioma in the head and neck. Laryngoscope. 2018;129:E67–E71. doi: 10.1002/lary.27509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Griffiths A.J., Miller J.H., Suzuki D.T., Lewontin R.C., Gelbart W.M. An Introduction to Genetic Analysis. 7th ed. W.H. Freeman; New York, NY, USA: 2000. Somatic Versus Germinal Mutation. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guha A., Musil Z., Vicha A., Zelinka T., Pacak K., Astl J., Chovanec M. A systematic review on the genetic analysis of paragangliomas: Primarily focused on head and neck paragangliomas. Neoplasma. 2019;66:671–680. doi: 10.4149/neo_2018_181208N933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rattenberry E., Vialard L., Yeung A., Bair H., McKay K., Jafri M., Canham N., Cole T.R., Denes J., Hodgson S.V., et al. A Comprehensive Next Generation Sequencing–Based Genetic Testing Strategy to Improve Diagnosis of Inherited Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013;98:E1248–E1256. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crona J., Taïeb D., Pacak K. New Perspectives on Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma: Toward a Molecular Classification. Endocr. Rev. 2017;38:489–515. doi: 10.1210/er.2017-00062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taïeb D., Pacak K. New Insights into the Nuclear Imaging Phenotypes of Cluster 1 Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2017;28:807–817. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2017.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jochmanova I., Pacak K. Genomic Landscape of Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma. Trends Cancer. 2018;4:6–9. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2017.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gimenez-Roqueplo A.-P., Dahia P.L., Robledo M. An Update on the Genetics of Paraganglioma, Pheochromocytoma, and Associated Hereditary Syndromes. Horm. Metab. Res. 2012;44:328–333. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1301302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gunawardane P.T.K., Grossman A.B. The clinical genetics of phaeochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Arch. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017;61:490–500. doi: 10.1590/2359-3997000000299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gupta N., Strome S.E., Hatten K.M. Is routine genetic testing warranted in head and neck paragangliomas? Laryngoscope. 2018;129:1491–1493. doi: 10.1002/lary.27656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khatami F., Mohammadamoli M., Tavangar S.M. Genetic and epigenetic differences of benign and malignant pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas (PPGLs) Endocr. Regul. 2018;52:41–54. doi: 10.2478/enr-2018-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Welander J., Söderkvist P., Gimm O. Genetics and clinical characteristics of hereditary pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 2011;18:R253–R276. doi: 10.1530/ERC-11-0170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dahia P.L.M. Pheochromocytomas and Paragangliomas, Genetically Diverse and Minimalist, All at Once! Cancer Cell. 2017;31:159–161. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu P., Li M., Guan X., Yu A., Xiao Q., Wang C., Hu Y., Zhu F., Yin H., Yi X., et al. Clinical Syndromes and Genetic Screening Strategies of Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma. J. Kidney Cancer VHL. 2018;5:14–22. doi: 10.15586/jkcvhl.2018.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Opocher G., Schiavi F. Genetics of pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010;24:943–956. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kantorovich V., King K.S., Pacak K. SDH-related pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010;24:415–424. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Williams M.D. Paragangliomas of the Head and Neck: An Overview from Diagnosis to Genetics. Head Neck Pathol. 2017;11:278–287. doi: 10.1007/s12105-017-0803-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ong R.K.S., Flores S.K., Reddick R.L., Dahia P.L.M., Shawa H. A Unique Case of Metastatic, Functional, Hereditary Paraganglioma Associated with anSDHC Germline Mutation. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018;103:2802–2806. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-01302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weinhold B. Epigenetics: The Science of Change. Environ. Health Perspect. 2006;114:A160–A167. doi: 10.1289/ehp.114-a160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rao S., Chiu T.-P., Kribelbauer J.F., Mann R.S., Bussemaker H.J., Rohs R. Systematic prediction of DNA shape changes due to CpG methylation explains epigenetic effects on protein–DNA binding. Epigenetics Chromatin. 2018;11:6. doi: 10.1186/s13072-018-0174-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ross J.S., Cronin M. Whole Cancer Genome Sequencing by Next-Generation Methods. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2011;136:527–539. doi: 10.1309/AJCPR1SVT1VHUGXW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Currás-Freixes M., Inglada-Pérez L., Mancikova V., Montero-Conde C., Letón R., Comino-Méndez I., Apellániz-Ruiz M., Sánchez-Barroso L., Sánchez-Covisa M.A., Alcázar V., et al. Recommendations for somatic and germline genetic testing of single pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma based on findings from a series of 329 patients. J. Med. Genet. 2015;52:647–656. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2015-103218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roose L.M., Rupp N.J., Röösli C., Valcheva N., Weber A., Beuschlein F., Tschopp O. Tinnitus with Unexpected Spanish Roots: Head and Neck Paragangliomas Caused by SDHAF2 Mutation. J. Endocr. Soc. 2020;4 doi: 10.1210/jendso/bvaa016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brouwers F.M., Eisenhofer G., Tao J.J., Kant J.A., Adams K.T., Linehan W.M., Pacak K. High Frequency ofSDHBGermline Mutations in Patients with Malignant Catecholamine-Producing Paragangliomas: Implications for Genetic Testing. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006;91:4505–4509. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Favier J., Amar L., Gimenez-Roqueplo A.-P. Paraganglioma and phaeochromocytoma: From genetics to personalized medicine. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2015;11:101–111. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2014.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]