Key Points

Question

What is the risk of electrolyte disorders in acutely ill children receiving commercially available plasmalike isotonic fluids?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial of 614 acutely ill children, the risk of electrolyte disorders was 6.7-fold greater in children receiving plasmalike isotonic fluid therapy as compared with those receiving moderately hypotonic fluid therapy with 20 mmol/L of potassium.

Meaning

These findings suggest that commercially available plasmalike isotonic fluids are not optimal for fluid therapy in acutely ill children.

This randomized clinical trial uses data from a pediatric emergency department in Finland to evaluate the risk of developing electrolyte disorders in acutely ill children receiving commercially available plasmalike isotonic fluid therapy containing 20 mmol/L of potassium.

Abstract

Importance

The use of isotonic fluid therapy is currently recommended in children, but there is limited evidence of optimal fluid therapy in acutely ill children.

Objective

To evaluate the risk for electrolyte disorders, including hyponatremia, hypernatremia, and hypokalemia, and the risk of fluid retention in acutely ill children receiving commercially available plasmalike isotonic fluid therapy.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This unblinded, randomized clinical pragmatic trial was conducted at the pediatric emergency department of Oulu University Hospital, Finland, from October 3, 2016, through April 15, 2019. Eligible study subjects (N = 614) were between 6 months and 12 years of age, required hospitalization due to an acute illness, and needed intravenous fluid therapy. Exclusion criteria included a plasma sodium concentration of less than 130 mmol/L or greater than 150 mmol/L on admission; a plasma potassium concentration of less than 3.0 mmol/L on admission; clinical need of fluid therapy with 10% glucose solution; a history of diabetes, diabetic ketoacidosis, or diabetes insipidus; a need for renal replacement therapy; severe liver disease; pediatric cancer requiring protocol-determined chemotherapy hydration; and inborn errors of metabolism. All outcomes and samples size were prespecified except those clearly marked as exploratory post hoc analyses. All analyses were intention to treat.

Interventions

Acutely ill children were randomized to receive commercially available plasmalike isotonic fluid therapy (140 mmol/L of sodium and 5 mmol/L potassium in 5% dextrose) or moderately hypotonic fluid therapy (80 mmol/L sodium and 20 mmol/L potassium in 5% dextrose).

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was the proportion of children with any clinically significant electrolyte disorder, defined as hypokalemia less than 3.5 mmol/L, hypernatremia greater than 148 mmol/L, or hyponatremia less than 132 mmol/L during hospitalization due to acute illness. The main secondary outcomes were the proportion of children with severe hypokalemia and weight change.

Results

There were 614 total study subjects (mean [SD] age, 4.0 [3.1] years; 315 children were boys [51%] and all 614 were Finnish speaking [100%]). Clinically significant electrolyte disorder was more common in children receiving plasmalike isotonic fluid therapy (61 of 308 patients [20%]) compared with those receiving moderately hypotonic fluid therapy (9 of 306 patients [2.9%]; 95% CI of the difference, 12%-22%; P < .001). The risk of developing electrolyte disorder was 6.7-fold greater in children receiving isotonic fluid therapy. Hypokalemia developed in 57 patients (19%) and hypernatremia developed in 4 patients (1.3%) receiving plasmalike isotonic fluid therapy. Weight change was greater in children receiving isotonic, plasmalike fluid therapy compared with those receiving mildly hypotonic fluids (mean weight gain, 279 vs 195 g; 95% CI, 16-154 g; P = .02).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this randomized clinical trial, commercially available plasmalike isotonic fluid therapy markedly increased the risk for clinically significant electrolyte disorders, mostly due to hypokalemia, in acutely ill children compared with previously widely used moderately hypotonic fluid therapy containing 20 mmol/L of potassium.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02926989

Introduction

Since 2018, the American Academy of Pediatrics has been recommending isotonic solutions for intravenous maintenance fluid therapy in most children to avoid hyponatremia.1 Fatal hyponatremia or severe brain damage has been reported in children receiving hypotonic intravenous fluid therapy, in particular in postoperative patients receiving high amounts of hypotonic fluids.2,3,4,5,6 Decreased occurrence of mild hyponatremia in children receiving isotonic fluid therapy has been reported in randomized clinical trials in pediatric intensive care patients,7,8,9 in postoperative patients,10,11,12,13 and in mixed pediatric populations.14,15,16

The recommendation of the American Academy of Pediatrics has markedly changed fluid therapy in children toward isotonic fluid therapy instead of moderately hypotonic fluid therapy. Yet, there is still limited evidence of isotonic fluid therapy outcomes in acutely ill children.17,18 Furthermore, isotonic fluids have been shown to result in decreased renal output in healthy adult volunteers.19 The recent American Academy of Pediatrics guideline acknowledges the limited evidence on the risk of hypernatremia and fluid retention in children receiving isotonic fluid therapy.1 Finally, clinical trials using plasmalike isotonic solutions have not reported the risk of hypokalemia in children.14,18 Thus, the appropriate amount of potassium in intravenous fluid therapy is not known.

We conducted a large randomized trial to evaluate the risk for electrolyte disorders, including hyponatremia, hypernatremia, and hypokalemia, and the risk of fluid retention in acutely ill children receiving plasmalike, ready-to-use isotonic fluid products.14 Moderately hypotonic fluid with 80 mmol/L of sodium and 20 mmol/L of potassium was the control treatment because it was the recommended choice in pediatric textbooks when this study was started.20

Methods

Trial Design and Oversight

This prespecified, unblinded, randomized, pragmatic clinical trial was conducted at the pediatric emergency department (ED) of Oulu University Hospital, Finland, from October 3, 2016, through April 15, 2019. The pediatric ED in the present study is a part of the Finnish public health care system and the only hospital in the area with pediatric wards providing intravenous fluid therapy for acutely ill children. The trial was conducted in accordance with the principles of Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline. This trial was registered at ClinicalTrialsRegister.eu before initiation (EUDRA-CT 2016-002046)21 and at ClinicalTrials.gov during the first days of the study (NCT02926989).22 The Finnish Medical Agency reviewed the study protocol before its initiation. The Regional Ethics Committee of the Northern Ostrobothnia Hospital District, Oulu, Finland, approved the study protocol. The study protocol with a full literature review and statistical analysis plan is available (Supplement 1 and eTable in Supplement 2). Parents or legal guardians gave their written informed consent before participation. Patients aged 6 to 12 years gave their own written consent in addition to parental consent. The authors designed the trial, collected the data, and performed the analyses. Treating physicians at the pediatric ED participated in the data collection. The first 3 authors (S.L, M.H., and M.K.) and the last author (T.T.) wrote the initial version of the manuscript, and all authors contributed to revisions. All authors approved the manuscript and vouched for the accuracy and completeness of the data.

Patients

Study subjects were eligible for enrollment in the trial if they were patients at the pediatric ED, were between 6 months and 12 years of age, required hospitalization due to an acute illness, and needed intravenous fluid therapy according to the clinical judgment of the treating physician. Exclusion criteria included a plasma sodium concentration of less than 130 mmol/L or greater than 150 mmol/L on admission; a plasma potassium concentration of less than 3.0 mmol/L on admission; clinical need of fluid therapy with 10% glucose solution; a history of diabetes, diabetic ketoacidosis, or diabetes insipidus; a need for renal replacement therapy; severe liver disease; pediatric cancer requiring protocol-determined chemotherapy hydration; and inborn errors of metabolism.

Trial Treatment

Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive isotonic or moderately hypotonic fluid therapy. The isotonic fluid (commercially available as Plasmalyte Glucos 50 mg/mL [Baxter UK]) contained 140 mmol/L of sodium in 5% dextrose, 5 mmol/L of potassium, 1.5 mmol/L of magnesium, 98 mmol/L of chloride, 23 mmol/L of acetate, and 23 mmol/L of gluconate. The moderately hypotonic solution contained 80 mmol/L of sodium chloride and 20 mmol/L of potassium chloride in 5% dextrose based on the existing recommendations in pediatric textbooks at the beginning of the study. Patients were allowed to receive fluid replacement of 20 mL/kg lactated Ringer solution or other isotonic crystalloids if clinically indicated before the initiation of the study fluid. A statistician created a computerized randomization list using permuted blocks of 4. Sealed, numbered, opaque envelopes contained the name of the study fluid according to the randomization list. Treating physicians enrolled patients, opened the randomization envelopes after receiving written informed consent, and assigned patients to intervention groups. The study investigators, treating physicians, nurses, patients, and patients’ legal guardians were aware of the intravenous fluid administered. Laboratory personnel performing laboratory analysis for electrolyte concentrations were unaware of the treatment group.

After randomization, the treating physician determined the infusion rate based on the daily fluid requirements estimated according to the Holliday-Segar formula23 and fluids needed for rehydration (weight decrease, g = mL, or clinical judgment, 5%-10% of weight). Fluids were administered using electronic delivery pumps programmed for an hourly infusion rate and continued until the treating physician decided to stop the administration. For safety reasons, the study design was open. The treating physicians were allowed to change the sodium or potassium concentrations, the fluid therapy product, or the infusion rate when clinically indicated.

Blood electrolytes were determined every morning, or more frequently when clinically indicated, during the acute illness until discharge from the hospital. All laboratory values were immediately available to the treating physicians. A venous blood sampling technique was recommended, but when unsuccessful, capillary blood sampling by skin puncture was performed. The study patients were weighed before the onset of fluid therapy, daily while in the hospital, and after the fluid therapy had stopped. The duration of the intravenous fluid therapy and the weight change were collected from the hospital medical records. Other laboratory tests were performed as clinically indicated.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the proportion of children with any clinically significant electrolyte disorder, defined as hypokalemia less than 3.5 mmol/L, hypernatremia greater than 148 mmol/L, or hyponatremia less than 132 mmol/L during hospitalization due to acute illness. The secondary outcomes were the proportion of children with severe hypokalemia, defined as potassium less than 3.0 mmol/L; the proportion of children with mild hyponatremia, defined as plasma sodium 132 to 135 mmol/L; the fluid retention measured by weight change (in grams) during hospitalization: weight (in grams) at discharge – weight (in grams) on admission; the proportion of children requiring any change of fluid therapy; the proportion of children admitted to intensive care after admission; the duration of intravenous fluid therapy (hours); the duration of hospitalization; and the number of deaths. All secondary outcomes were reported during hospitalization due to acute illness except the number of deaths within 30 days of randomization. Exploratory post hoc analyses, added to the analyses after starting the study, included the time to electrolyte disorder (hours), analyses regarding metabolic acidosis in those with available blood gas samples, and copeptin values as a precursor for antidiuretic hormone in a random sample of patients at 6 to 24 hours.

Statistical Analysis

The occurrence of any clinically significant electrolyte disorder in children receiving isotonic fluid therapy was estimated to be 13% based on a previous study reporting the need of adding potassium in plasmalike fluid in children.14 We considered the difference between groups to be clinically significant if the occurrence of an electrolyte disorder was 7% lower in children receiving moderately hypotonic fluid. We set the α error at 5% and the β error at 20%, ie, a power of 80%, which resulted in 275 children per group. To ensure that the final analysis included the required number of children with a measured primary outcome, we decided to recruit 305 children per group. All analyses were performed in strict intention-to-treat population. Primary and secondary outcomes were specified in the protocol before starting the study. Post hoc analyses after the original statistical analysis are presented separately (Supplement 1).

In hospitalized participants, missing data were rare. Risk ratios and the number needed to treat to avoid 1 patient developing an electrolyte disorder in the hypotonic fluid therapy group were calculated. The number needed to harm was used if isotonic fluid increased the risk. For primary and secondary outcomes, we calculated 95% CIs of the differences using a standard normal deviate test for the proportions and a t test for continuous variables with a statistical significance level of <.05.24 P values were 2-sided. The widths of CIs were not adjusted for multiplicity and should not be interpreted as definite treatment effects. All analyses were performed using IBM Statistics for Windows, version 26 (IBM Corp) and StatsDirect statistical software, version 3 (StatsDirect Ltd). Statistical analyses were performed from May 20, 2019, to January 8, 2020.

Results

Characteristics of the Patients

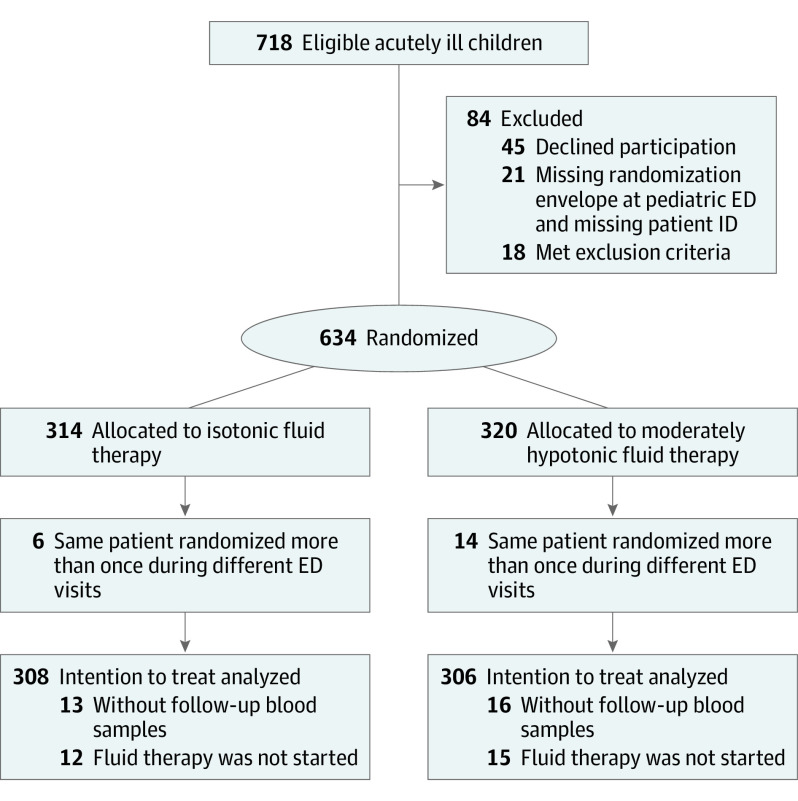

From October 3, 2016, to April 15, 2019, a total of 713 acutely ill children potentially in need of maintenance fluid therapy were evaluated for suitability for the study (Figure 1). Altogether, 84 patients were excluded, either because they declined to participate, did not meet the inclusion criteria, or the randomization envelope or patient identification were missing. Only the first visit was included in the analysis for 20 patients (6 isotonic and 14 hypotonic) enrolled more than once during different visits at the ED. Thus, 614 patients were included in the intention-to-treat population (mean [SD] age, 4.0 [3.1] years; 315 children were boys [51%] and all 614 were Finnish speaking [100%]; Table 1). The mean (SD) duration of hospitalization was 2.3 (3.8) days, and the mean (SD) duration of intravenous fluid therapy was 29 (41) hours. The most common reasons for hospitalization were respiratory infections, gastroenteritis, and other viral infections. Nine patients (1.5%) were admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit from the ED. A total of 73 patients (12%) needed anesthesia during hospitalization. Mean (SD) time from stopping intravenous fluid therapy to discharge from the hospital was 19.3 (31.1) hours in children receiving isotonic fluid therapy and 19.1 (31.3) hours in patients receiving moderately hypotonic therapy.

Figure 1. Study Design.

Altogether, 21 children were excluded owing to diabetes (5), pediatric cancer (1), severe hyponatremia at admission (1), severe hypokalemia at admission (1), age criterion not satisfied (7), parents did not understand the informed consent (1), and reason not specified by ED physician (5). The total number of children who both received fluid therapy and had at least 1 blood sample obtained was 283 in the isotonic group and 275 in the moderately hypotonic group. No children were lost to follow-up because the study ended at discharge from hospital. ED indicates emergency department.

Table 1. Characteristics of the Patients at Baseline.

| Characteristic | Fluid therapy, mean (SD)a | |

|---|---|---|

| Isotonic (n = 308) | Moderately hypotonic (n = 306) | |

| Age, y | 4.0 (3.1) | 4.1 (3.1) |

| Female, No. (%) | 147 (48) | 152 (50) |

| Weight, kg | 17 (9) | 17 (9) |

| Dehydration, No. (%) | 1.7 (3.4) | 1.5 (2.9) |

| Plasma, mmol/L | ||

| Sodium | 138 (2.8) | 138 (2.6) |

| Potassium | 4.1 (0.4) | 4.1 (0.5) |

| pH | 7.4 (0.06) | 7.4 (0.06) |

| Bicarbonate | 22 (4.0) | 22 (3.7) |

| Base excess | −2.6 (3.6) | −2.5 (3.4) |

| Coexisting illness, No. (%) | ||

| None | 262 (85) | 258 (84) |

| Asthma | 17 (6) | 15 (5) |

| Neurodevelopmental disorder | 9 (3) | 7 (2) |

| Other | 20 (6) | 26 (9) |

| Acute illness, No. (%) | ||

| Respiratory infection | 109 (35) | 98 (32) |

| Pneumonia | 55 (18) | 53 (17) |

| Empyema | 3 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Viral wheezing | 33 (11) | 27 (8) |

| Other | 21 (7) | 22 (7) |

| Gastroenteritis, No. (%) | 84 (27) | 81 (26) |

| Norovirus | 16 (5) | 9 (3) |

| Rotavirus | 21 (7) | 13 (4) |

| Adenovirus | 7 (2) | 3 (1) |

| Campylobacter | 1 (0) | 0 (0) |

| EHEC | 0 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Pyelonephritis | 18 (6) | 15 (5) |

| Sepsis | 1 (0) | 4 (1) |

| Other infections | ||

| Bacterial | 20 (6) | 24 (8) |

| Viral | 27 (9) | 31 (10) |

| Neurologic illness | 9 (3) | 10 (3) |

| Febrile seizure | 1 (0) | 2 (1) |

| Surgical illness | 15 (5) | 20 (7) |

| Appendicitis | 7 (2) | 9 (3) |

| Miscellaneous | 25 (8) | 23 (8) |

| Other treatments, No. (%) | ||

| Fluid bolus, 10-20 mL/kg at ED | 77 (25) | 79 (26) |

| Admission to PICU from ED | 3 (1) | 6 (2) |

| Need for anesthesia or sedationb | 36 (12) | 37 (12) |

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; EHEC, enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PICU, pediatric intensive care unit.

Values are expressed as mean (SD) unless otherwise specified.

MRI, chest tube, joint puncture, or appendectomy.

Primary Outcome

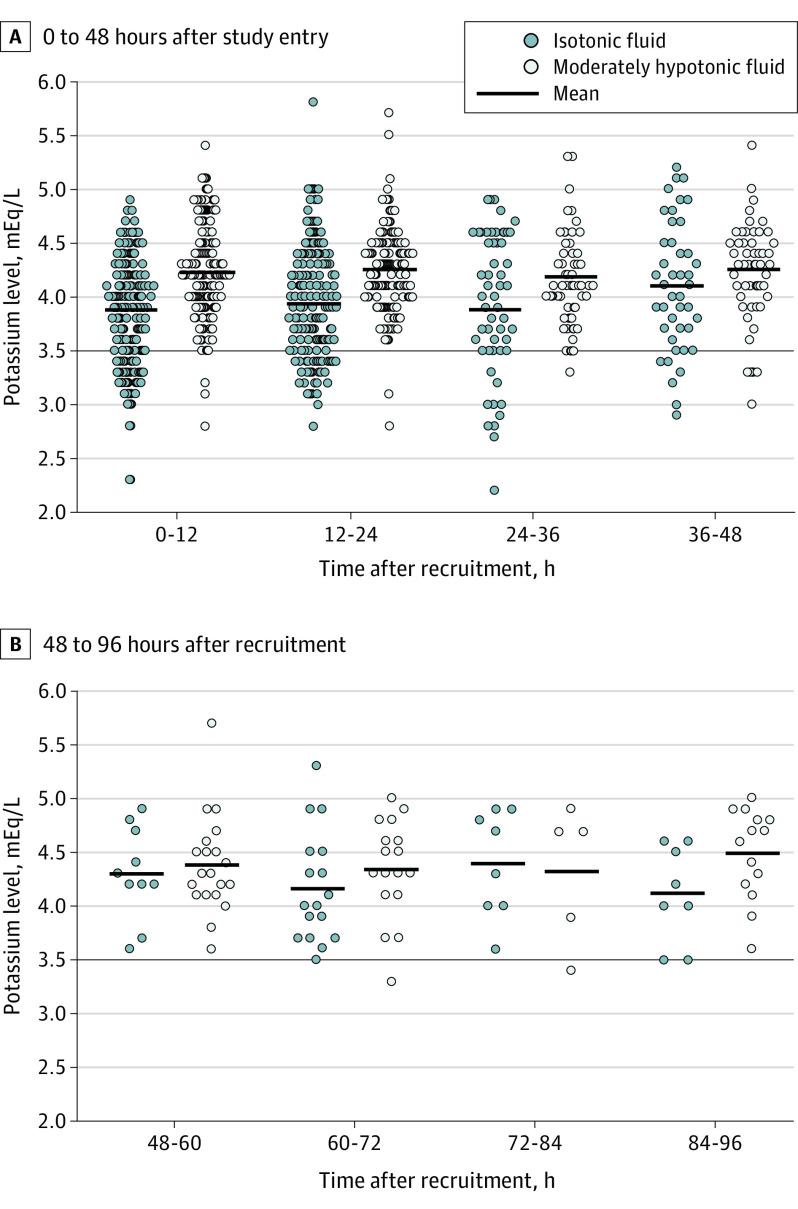

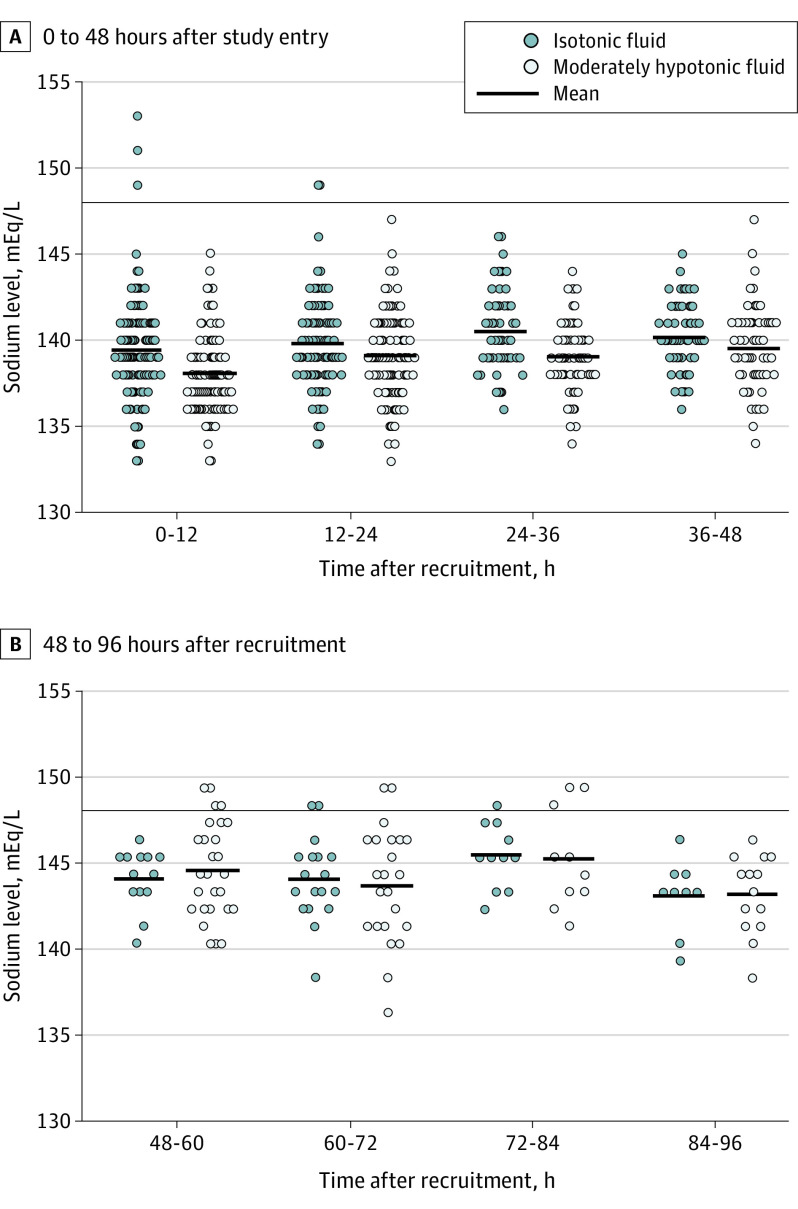

Clinically significant electrolyte disorders were more common in children receiving isotonic fluid therapy (61 of 308 patients, 20%) compared with those receiving moderately hypotonic fluid therapy (9 of 306 patients, 2.9%) (95% CI of the difference, 12%-22%; P < .001) (Table 2, Figures 2 and 3). The risk ratio for clinically significant electrolyte disorder was 6.7 (95% CI, 3.5-13), and the number needed to harm was 6 (95% CI, 5-9) in children receiving isotonic fluid therapy compared with those receiving moderately hypotonic fluid therapy. Hypokalemia developed in 57 patients (19%) receiving isotonic fluid therapy and in 9 patients (2.9%) receiving moderately hypotonic fluid therapy (95% CI, 11%-21%) (P < .001). Hypernatremia developed in 4 patients (1.3%) receiving isotonic fluid therapy and in none of those receiving moderately hypotonic fluid therapy (95% CI of the difference, 0.05%-3.3%; P = .04) (Table 2). None of the patients developed severe hyponatremia (sodium <132 mmol/L) (Table 2).

Table 2. Primary and Secondary Outcomes.

| Outcome | Fluid therapy, No. (%) | Difference (95% CI)a | NNT (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isotonic (n = 308) | Moderately hypotonic (n = 306) | ||||

| Primary outcome 0-7 db | |||||

| Electrolyte disorder, No. (%) | 61 (20) | 9 (2.9) | 17 (12 to 22) | Harm, 6 (5 to 9) | 6.7 (3.5 to 13) |

| Components of the composite outcome | |||||

| Hypokalemia (<3.5 mmol/L) | 57 (19) | 9 (2.9) | 16 (11 to 21) | Harm, 7 (5 to 10) | 6.3 (3.2 to 12) |

| Hypernatremia (>148 mmol/L) | 4 (1.3) | 0 | 1.3 (0.05 to 3) | Harm, 78 (31 to 2047) | ∞ (1.04 to ∞) |

| Hyponatremia (<132 mmol/L) | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA |

| Secondary outcomes 0-7 d | |||||

| Severe hypokalemia (<3.0 mmol/L) | 8 (2.6) | 1 (0.3) | 2.3 (0.5 to 4.8) | Harm, 45 (22 to 211) | 7.9 (1.3 to 49) |

| Mild hyponatremia (132-135 mmol/L) | 7 (2.3) | 11 (3.6) | −1.3 (−4 to 1.5) | NA | 0.6 (0.3 to 1.6) |

| Weight change, g | 279 (431)c | 195 (420)c | 84 (16 to 154) | NA | NA |

| Any change of fluid therapy | 40 (13) | 46 (15) | −2 (−7.6 to 3.4) | NA | 0.8 (0.6 to 1.3) |

| Switch to isotonic group, No. (%) | NA | 4 (1.3) | NA | NA | NA |

| Switch to moderately hypotonic group, No. (%) | 7 (2.2) | NA | |||

| Extra potassium added, No. (%) | 8 (2.6) | 1 (0.3) | |||

| Referral to intensive care | 9 (2.9) | 11 (3.6) | −0.7 (−3.7 to 2) | NA | 0.8 (0.4 to 1.9) |

| Duration of IV fluids, h | 29.5 (50)c | 29.4 (29)c | 0.1 (−6.5 to 7) | NA | NA |

| Length of stay in d | 2.3 (4.5)c | 2.2 (3.0)c | 0.1 (−0.5 to 0.7) | NA | NA |

| No. of deathsd | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA |

| Exploratory post hoc analyses | |||||

| pH <7.35 on day 1e | 9/132 (6.8) | 16/152 (11) | −4 (−11 to 3) | NA | 0.6 (0.3 to 1.4) |

| Bicarbonate (<21 on day 1e) | 7/132 (5.3) | 39/152 (26) | −21(−29 to −12) | Benefit, 5 (4 to 9) | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.4) |

| Base excess (<−2.5 on day 1e) | 14/132 (11) | 50/152 (33) | −22 (−31 to −13) | Benefit, 5 (4 to 8) | 0.3 (0.2 to 0.5) |

| Copeptin, pmol/Lf | 8.1 (5.4)c | 7.3 (4.6)c | 0.8 (−2 to 3.8) | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: IV, intravenous; NA, not applicable; NNT, number needed to treat; RR, risk ratio.

Standard normal deviation test for proportions and Student t test for continuous variable.

The primary outcome was the proportion of children with any clinically significant electrolyte disorder during the first week of hospitalization. The isotonic fluid contained 140 mmol/L of sodium and 5 mmol/L of potassium. The moderately hypotonic fluid contained 80 mmol/L of sodium and 20 mmol/L of potassium. Number needed to treat was calculated to show the benefit of isotonic fluid therapy over moderately hypotonic fluid therapy in avoiding one child with an electrolyte disorder. If the association was reverse, ie, there were more electrolyte disorders in the isotonic group, the number needed to harm was reported.

Values written as mean (SD).

Death 0-30 days.

Blood gas analysis of those with available results.

Copeptin levels examined at 6-24 hours fluid in a random sample (10%) of the participants.

Figure 2. Potassium Concentrations at Different Time Points.

Potassium levels are presented in the intention-to-treat population of children (N = 614) randomly allocated to receive plasmalike isotonic fluid therapy or moderately hypotonic fluid therapy with 80 mmol/L of sodium and 20 mmol/L of potassium. Each dot indicates the value of 1 study subject. The short horizontal lines indicate the mean value of the group in each time frame. The long horizontal line indicates the limit of clinically significant electrolyte disorder used in the statistical analysis. Potassium values indicating hyperkalemia >5.5. mmol/L were not verified in subsequent samples but were kept in the data unless the problem with the hemolysis was specifically marked in the laboratory sheets, resulting in hyperkalemia in 1 of 308 vs 2 of 306 (95% CI of the difference, –2% to 1.2%).

Figure 3. Sodium Concentrations at Different Time Points.

Sodium levels are presented in the intention-to-treat population of children (N = 614) randomly allocated to receive plasmalike isotonic fluid therapy or moderately hypotonic fluid therapy with 80 mmol/L of sodium and 20 mmol/L of potassium. Each dot indicates the value of 1 study subject. The short horizontal lines indicate the mean value of the group in each time frame. The long horizontal line indicates the limit of clinically significant electrolyte disorder used in the statistical analysis.

Secondary Outcomes

Severe hypokalemia (<3.0 mmol/L) was significantly more common in patients receiving plasmalike isotonic fluid therapy (8 of 308 patients, 2.6%) compared with patients receiving moderately hypotonic fluid therapy (1 of 306 patients, 0.3%) (95% CI of the difference, 0.5%-4.8%; P = .02) with a risk ratio of 7.9 (95% CI, 1.3-49) and number needed to harm of 45 (95% CI, 22-211). The patients with severe hypokalemia in the isotonic fluid therapy group (8 total) were hospitalized due to gastroenteritis (3 adenoviruses [37.5%], 1 rotavirus [12.5%]), severe pneumonia requiring intensive care (2 [25%]), pneumonia (1; 12.5%), and severe viral wheezing requiring intensive care (1 [12.5%]). The patient who developed severe hypokalemia in the moderately hypotonic fluid therapy group was hospitalized due to pneumonia. The occurrence of mild hyponatremia (sodium, 132-135 mmol/L) did not differ between children receiving isotonic fluid therapy (7 of 308 patients, 2.3%) and children receiving moderately hypotonic fluid therapy (11 of 306 patients, 3.6%) (difference, –1.3%; 95% CI, –4.3 to 1.5; P = .33).

Children receiving isotonic fluid therapy had a greater weight gain during the hospitalization (279 g) as compared with those receiving moderately hypotonic fluid therapy (195 g) (95% CI of the difference, 16-154 g; P = .02) (Table 2). There was no difference in the total proportion of children whose fluid therapy was modified by clinicians either by adding electrolytes or by changing fluid therapy otherwise between the 2 study groups. The need for pediatric intensive care unit treatment, duration of intravenous fluid therapy, and time to discharge from hospital did not differ between the groups. There were no deaths in the study population.

Exploratory Post Hoc Analyses

Mean (SD) time to the development of hypernatremia was 12 (4.9) hours in children receiving isotonic fluid therapy. Mean (SD) time to the development of hypokalemia was 14 (8.4) hours in children receiving isotonic fluid and 31 (26) hours in children receiving moderately hypotonic fluid (95% CI, –37 to –2.2; P = .07). Metabolic acidosis, measured by base excess and bicarbonate levels in blood gas analysis, resolved faster in children receiving isotonic fluid therapy compared with children receiving moderately hypotonic fluid therapy. Low bicarbonate levels on the day after admission were detected in 7 of 132 patients (5.3%) with a measurement in the isotonic group and in 39 of 152 patients (26%) with a measurement in the moderately hypotonic group (difference, –21%; 95% CI, –29% to –12%; Table 2). In retrospect, in a random sample of participants (10%), copeptin levels were examined in frozen plasma samples, obtained at 6 to 24 hours after starting fluid therapy, to evaluate whether copeptin levels were higher in children exposed to isotonic fluid therapy and higher concentrations of sodium. Copeptin values were higher in children receiving isotonic fluid therapy vs those receiving moderately hypotonic fluid therapy (mean [SD], 8.1 [5.4] vs 7.3 [4.6] pmol/L), but the difference was not statistically significant (Table 2).

Severe Adverse Events

There were no reported neurologic complications in the study population. One patient who received isotonic fluid therapy was transferred to the pediatric intensive care unit due to severe hypokalemia (potassium, 2.2 mmol/L) on the third day of fluid therapy. This patient had the Finnish type of congenital nephrosis without severe renal dysfunction or need for dialysis and was hospitalized due to adenovirus gastroenteritis. Another patient, with rotavirus infection and mild hypokalemia (potassium, 3.1 mmol/L) in the isotonic fluid group, had myoclonus and seizures during hospitalization and was later diagnosed with epilepsy.

Discussion

In this randomized, pragmatic single-center trial of 614 acutely ill children at a pediatric ED of a university hospital, commercially available plasmalike isotonic fluid increased the risk of clinically significant electrolyte disorder compared with moderately hypotonic fluid containing 80 mmol/L of sodium and 20 mmol/L of potassium. The risk of developing electrolyte disorder was 6.7-fold greater in children receiving isotonic fluid therapy, mostly due to the increased risk of hypokalemia. Electrolyte disorders were not prevented by the open study design, which allowed physicians to change fluid therapy during hospitalization. The length of stay did not differ between the treatment groups.

Most electrolyte disorders observed in children receiving plasmalike isotonic fluid therapy in the present study were due to hypokalemia. Hypokalemia is a common electrolyte disorder among children receiving intravenous fluid therapy or treated at an intensive care unit.25,26 The recent guideline by the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends adding an appropriate amount of potassium in fluids.1 Yet, commercially available plasmalike isotonic fluids have been used in earlier randomized controlled trials without reporting the risk of hypokalemia.14,18 Our study shows that the use of isotonic fluid therapy with a plasmalike potassium concentration is potentially dangerous in acutely ill children because it increased the risk of hypokalemia. Thus, adding potassium routinely to commercially available plasmalike fluids appears to be essential in acutely ill children, even in the absence of hypokalemia at admission.

In the present study, children receiving plasmalike isotonic fluid therapy had an increased risk for hypernatremia. Before the present study, the risk of hypernatremia was poorly documented in acutely ill children receiving isotonic fluid therapy.1,18 The earlier meta-analysis showed wide and inconclusive 95% CIs for the risk of hypernatremia (RR, 0.6-2.4) in children receiving isotonic fluids.18 Untreated hypernatremia has previously been associated with an increased risk of mortality in hospitalized children.27 Even though all children with hypernatremia in the present study were asymptomatic, our results raise concerns about the risks of using isotonic fluid in acutely ill children.

Weight gain was greater in children receiving isotonic fluid therapy than in those receiving moderately hypotonic fluids. The mean difference was minimal and most likely clinically insignificant. Yet, water retention due to excess amounts of sodium might be associated with increased weight in a few patients. In the largest17 of 3 earlier studies reporting weight gain, with 110 acutely ill children, greater weight gain among children receiving isotonic fluid therapy was observed, but the difference was not statistically significant.17,28,29 The greater weight gain suggested by the present study may be clinically insignificant for most pediatric patients, but it might cause a risk for vulnerable patient populations.30

The risk of hyponatremia was not increased in patients receiving moderately hypotonic fluid therapy, which is contrary to the risk reported earlier.1,18 This discrepancy is likely explained by the different patient populations, as previous studies mainly included pediatric patients receiving intensive care7,8,9 and postoperative patients10,11,12,13 but only a few acutely ill children. Furthermore, one-third of our patients suffered from dehydration due to viral gastroenteritis, suggesting hypotonic fluid losses before the fluid therapy.31 One of the few earlier studies with a similar study population of acutely ill children did not show an increased risk of hyponatremia in those receiving moderately hypotonic fluids either.17 Finally, our study allowed changes in fluid therapy, which may have prevented the development of hyponatremia in a few patients.

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of the study include a large cohort of acutely ill children with a thorough clinical follow-up in a pragmatic randomized trial. The study design with access to unmasked laboratory values reflects a real-life situation. There were several limitations. This was a single-center study. Despite a rather large sample size, the statistical power of the study is insufficient to assess mortality and neurologic sequelae. In addition, we included only children with normal kidney function.32 Thus, the results of the present study are not generalizable to children with kidney failure or other conditions used as exclusion criteria. The unblinded study design might interfere with the outcomes based on the clinical evaluation, such as the length of stay. The commercial product used may not be available in all institutions.

Conclusions

In this randomized clinical trial, commercially available plasmalike isotonic fluid increased the risk for clinically significant electrolyte disorders in acutely ill children compared with previously widely used moderately hypotonic fluid therapy containing 80 mmol/L of sodium and 20 mmol/L potassium. These findings suggest that plasmalike isotonic fluid may be unsuitable for fluid therapy in acutely ill children unless extra potassium is added. The clinical significance of hypernatremia and weight gain in children receiving isotonic fluid therapy should be investigated in the future.

Trial Protocol

eTable. Full List of Randomized Clinical Trials Comparing Isotonic Fluid Therapy and Hypotonic or Moderately Hypotonic Fluid Therapy in Children

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Feld LG, Neuspiel DR, Foster BA, et al. ; Subcommittee on Fluid and Electrolyte Therapy . Clinical practice guideline: maintenance intravenous fluids in children. Pediatrics. 2018;142(6):1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arieff AI, Ayus JC, Fraser CL. Hyponatraemia and death or permanent brain damage in healthy children. BMJ. 1992;304(6836):1218-1222. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6836.1218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halberthal M, Halperin ML, Bohn D. Lesson of the week: acute hyponatraemia in children admitted to hospital: retrospective analysis of factors contributing to its development and resolution. BMJ. 2001;322(7289):780-782. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7289.780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moritz ML, Ayus JC. Preventing neurological complications from dysnatremias in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2005;20(12):1687-1700. doi: 10.1007/s00467-005-1933-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koczmara C, Hyland S, Greenall J. Hospital-acquired acute hyponatremia and parenteral fluid administration in children. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2009;62(6):512-515. doi: 10.4212/cjhp.v62i6.851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grissinger M. Hyponatremia and death in healthy children from plain dextrose and hypotonic saline solutions after surgery. P T. 2013;38(7):364-388. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Montañana PA, Modesto i Alapont V, Ocón AP, López PO, López Prats JL, Toledo Parreño JD. The use of isotonic fluid as maintenance therapy prevents iatrogenic hyponatremia in pediatrics: a randomized, controlled open study. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2008;9(6):589-597. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31818d3192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yung M, Keeley S. Randomised controlled trial of intravenous maintenance fluids. J Paediatr Child Health. 2009;45(1-2):9-14. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2007.01254.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rey C, Los-Arcos M, Hernández A, Sánchez A, Díaz JJ, López-Herce J. Hypotonic versus isotonic maintenance fluids in critically ill children: a multicenter prospective randomized study. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100(8):1138-1143. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02209.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brazel PW, McPhee IB. Inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone in postoperative scoliosis patients: the role of fluid management. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996;21(6):724-727. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199603150-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neville KA, Sandeman DJ, Rubinstein A, Henry GM, McGlynn M, Walker JL. Prevention of hyponatremia during maintenance intravenous fluid administration: a prospective randomized study of fluid type versus fluid rate. J Pediatr. 2010;156(2):313-319.e1, 2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.07.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choong K, Arora S, Cheng J, et al. Hypotonic versus isotonic maintenance fluids after surgery for children: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5):857-866. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coulthard MG, Long DA, Ullman AJ, Ware RS. A randomised controlled trial of Hartmann’s solution versus half normal saline in postoperative paediatric spinal instrumentation and craniotomy patients. Arch Dis Child. 2012;97(6):491-496. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2011-300221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McNab S, Duke T, South M, et al. 140 mmol/L of sodium versus 77 mmol/L of sodium in maintenance intravenous fluid therapy for children in hospital (PIMS): a randomised controlled double-blind trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9974):1190-1197. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61459-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saba TG, Fairbairn J, Houghton F, Laforte D, Foster BJ. A randomized controlled trial of isotonic versus hypotonic maintenance intravenous fluids in hospitalized children. BMC Pediatr. 2011;11:82. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-11-82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Torres SF, Iolster T, Schnitzler EJ, Siaba Serrate AJ, Sticco NA, Rocca Rivarola M. Hypotonic and isotonic intravenous maintenance fluids in hospitalised paediatric patients: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2019;3(1):e000385. doi: 10.1136/bmjpo-2018-000385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friedman JN, Beck CE, DeGroot J, Geary DF, Sklansky DJ, Freedman SB. Comparison of isotonic and hypotonic intravenous maintenance fluids: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(5):445-451. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McNab S, Ware RS, Neville KA, et al. Isotonic versus hypotonic solutions for maintenance intravenous fluid administration in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(12):CD009457. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009457.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Regenmortel N, De Weerdt T, Van Craenenbroeck AH, et al. Effect of isotonic versus hypotonic maintenance fluid therapy on urine output, fluid balance, and electrolyte homeostasis: a crossover study in fasting adult volunteers. Br J Anaesth. 2017;118(6):892-900. doi: 10.1093/bja/aex118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marcdante KJ, Kliegman RM, eds. Nelson Essentials of Pediatrics. 7th ed. Elsevier Saunders; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Isotonic versus hypotonic intravenous fluids in hospitalised children—a randomised controlled trial. ClinicalTrialsRegister.eu identifier: 2016-002046-23. Accessed September 19, 2020. https://www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu/ctr-search/search?query=eudract_number:2016-002046-23

- 22.Intravenous fluids in hospitalized children. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02926989. Updated August 22, 2019. Accessed September 19, 2020. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02926989

- 23.Holliday MA, Segar WE. The maintenance need for water in parenteral fluid therapy. Pediatrics. 1957;19(5):823-832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Armitage P, Berry G, Matthews JNS, eds. Statistical Methods in Research. 4th ed. Blackwell Science; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Armon K, Riordan A, Playfor S, Millman G, Khader A; Paediatric Research Society . Hyponatraemia and hypokalaemia during intravenous fluid administration. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93(4):285-287. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.093823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cummings BM, Macklin EA, Yager PH, Sharma A, Noviski N. Potassium abnormalities in a pediatric intensive care unit: frequency and severity. J Intensive Care Med. 2014;29(5):269-274. doi: 10.1177/0885066613491708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moritz ML, Ayus JC. The changing pattern of hypernatremia in hospitalized children. Pediatrics. 1999;104(3 Pt 1):435-439. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.3.435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Valadão MC, Piva JP, Santana JC, Garcia PC. Comparison of two maintenance electrolyte solutions in children in the postoperative appendectomy period: a randomized, controlled trial. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2015;91(5):428-434. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2015.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shamim A, Afzal K, Ali SM. Safety and efficacy of isotonic (0.9%) vs. hypotonic (0.18%) saline as maintenance intravenous fluids in children: a randomized controlled trial. Indian Pediatr. 2014;51(12):969-974. doi: 10.1007/s13312-014-0542-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alobaidi R, Morgan C, Basu RK, et al. Association between fluid balance and outcomes in critically ill children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(3):257-268. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.4540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whyte LA, Jenkins HR. Pathophysiology of diarrhoea. Paediatrics & Child Health. 2012;22:443–447. doi: 10.1016/j.paed.2012.05.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lehnhardt A, Kemper MJ. Pathogenesis, diagnosis and management of hyperkalemia. Pediatr Nephrol. 2011;26(3):377-384. doi: 10.1007/s00467-010-1699-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eTable. Full List of Randomized Clinical Trials Comparing Isotonic Fluid Therapy and Hypotonic or Moderately Hypotonic Fluid Therapy in Children

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement