Abstract

Introduction

The simultaneously increased prevalence of atopic diseases and decreased prevalence of infectious diseases might point to a link between the two entities. Past work mainly focused on either atopic diseases or recurrent infections. We aim to investigate whether risk factors for atopic diseases (ie, asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, and/or food allergy) differ from risk factors for recurrent respiratory tract infections (RRTIs) in children.

Methods

Cross‐sectional data were used from 5517 children aged 1 to 18 years who participated in an Electronic Portal for children between 2011 and 2019. Univariable/multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to determine risk factors for any atopic disease and RRTIs.

Results

Children aged ≥5 years were more likely to have any atopic disease (adjusted odds ratio [OR]: 1.50‐2.77) and less likely to have RRTIs (OR: 0.68‐0.84) compared to children aged less than 5 years. Female sex (OR: 0.72; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.63‐0.81), low birth weight (OR: 0.74; 95% CI: 0.57‐0.97) and dog ownership (OR: 0.79; 95% CI: 0.66‐0.95) reduced the odds of any atopic disease, but not of RRTIs. Daycare attendance (OR: 1.22; 95% CI: 1.02‐1.47) was associated with RRTIs, but not with atopic diseases. A family history of asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, and RRTIs was significantly associated with the same entity in children, with OR varying from 1.58 (95% CI: 1.35‐1.85) in allergic rhinitis to 2.20 (95% CI: 1.85‐2.61) in asthma.

Conclusion

Risk factors for atopic diseases are distinct from risk factors for RRTIs, suggesting that the changing prevalence of both entities is not related to shared risk factors.

Keywords: atopic disease, atopy, children, recurrent infection, respiratory tract infections, risk factors

Abbreviations

- CI

confidence interval

- IQR

interquartile range

- ISAAC

International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood

- n

number

- OR

odds ratio

- RRTIs

recurrent respiratory tract infections

1. INTRODUCTION

Atopic diseases are common diseases in childhood. The prevalence of asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, and food allergy has been estimated at approximately 20%, 15%, 8%, and 6%, respectively. 1 , 2 The prevalence of atopic diseases has been steadily rising in the past decades. 3 Simultaneously, the prevalence of infectious diseases has decreased. 4 These two trends in prevalence have been linked, leading to the hypothesis that a decline in infections or a lack of exposure to microbes could have an etiological role in the increased prevalence of atopic diseases. The known geographical variation in the prevalence of atopic diseases is in line with this hypothesis: a high prevalence in industrialized, urban environments concurrent with low microbial exposure, and a low prevalence in the developing or rural world concurrent with high microbial exposure. 5 It is known that early, repeated exposure to infectious agents stimulates the immune system to develop regulatory T‐cells, and hereby the development of atopic diseases may be prevented. 6

Environmental factors associated with a reduced risk of atopic diseases are often described as being associated with an increased risk of infections, such as daycare attendance, growing up in a rural environment, having older siblings and having pets. 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 A large number of epidemiological studies have described that other environmental factors, such as maternal smoking during pregnancy, postnatal exposure to cigarette smoke, air pollution, and a family history of atopic diseases, are associated with an increased prevalence of atopic diseases. 11

Although the opposing trends in the prevalence of atopic diseases and infections have been linked, studies investigating demographic, environmental, and family history risk factors for both atopic diseases and recurrent infections in conjunction are lacking. Large studies investigating a broad range of risk factors for atopic diseases and recurrent infections that enable adjustment for each other may lead to a better understanding of the development of these disease entities in children. A large set of data on this topic is available in the so‐called Electronic Portal developed by the University Medical Centre (UMC) Utrecht. This is a standardized data collection tool used in multiple centers across the Netherlands that includes data of several validated questionnaires on atopic diseases and recurrent respiratory tract infections (RRTIs) in childhood. 12 The primary aim of this study was to investigate how risk factors associated with any atopic disease (ie, asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, and/or food allergy) are different from risk factors associated with RRTIs in children. Our secondary aim was to investigate how these risk factors are associated with individual atopic disease entities.

2. METHODS

2.1. Domain and data collection

We performed a cross‐sectional questionnaire‐based study among children aged 1 to 18 years old who participated in the Electronic Portal between June 2011 and September 2019. The Electronic Portal is a web‐based application established by a nationwide collaborative network of Dutch caregivers. The details of the Electronic Portal have been previously published. 12 Children were included in the Electronic Portal as part of a first outpatient visit for respiratory or allergic symptoms in a participating secondary care (n = 9) or tertiary care (n = 1) center or as part of the WHISTLER birth cohort study. 13 No exclusion criteria other than age were specified. Of the 9558 children who were invited to participate in the Electronic Portal, 5517 (58%) children started the questionnaire and were evaluated in this study. Informed consent was obtained from all parents (and/or children as applicable) before enrolment. The study was reviewed and approved by the medical ethics committee of the University Medical Centre Utrecht (No. 10/348).

2.2. Measurements

2.2.1. Outcome definitions

Information on the presence of atopic diseases and RRTIs was extracted from the answers to the questionnaires in the Electronic Portal (Table S1). The definition of asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis was adopted from the ISAAC questionnaires. 14 Food allergy was defined as suggestive allergic symptoms within 2 hours after ingestion of the suspected food. RRTIs were defined as having a minimum number of upper or lower respiratory infections per year. 15 The minimum number depended on the child's age (Table S1).

2.2.2. Demographic, environmental, and family history factors

All risk factors were selected based on prior research and clinical expertise of the authors. 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 Information on the presence of the selected risk factors was extracted from answers to the questionnaires in the Electronic Portal. Included demographic factors were age, sex, gestational age, birth weight, maternal and paternal ethnicity, and education level. Included environmental factors were exclusive breastfeeding, pacifier use, having siblings, number of older siblings, daycare attendance in the first year of life, living environment (ie, rural or urban), having a dog, having a cat, maternal smoking during pregnancy, indoor smoking, adoption, vaccination status (ie, complete age‐appropriate vaccinations according to the Dutch vaccination schedule), flooring in the house and flooring in the child's bedroom (ie, solid or carpet). Included factors on family history were having a family history (ie, one or both parents and/or sibling(s) with the disease) of asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, food allergy or recurrent respiratory tract infections.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics including numbers (percentages) and medians (interquartile range [IQR]) were used to describe the study population. Data on all risk factors and outcomes were complete in 55% of the children and 92% of the values. Missing values were imputed by using multiple imputations (20 iterations) using SPSS. First, the crude association between risk factors and the disease outcome (ie, any of the atopic diseases or RRTIs) was assessed using univariable logistic regression analyses. Second, the adjusted association between the risk factors and outcome was assessed using multivariable logistic regression analyses. The multivariable regression analyses included all risk factors (no prior selection based on P values), the child's comorbidity and the analyses were controlled for inclusion setting (ie, secondary care, tertiary care, or birth cohort). The same analyses were performed per individual atopic disease entity. Results of the univariable and multivariable regression analyses were expressed as, respectively, crude odds ratios (ORs) and adjusted ORs with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). A P value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 25.0 for Windows (SPPS, INC, Chicago, IL).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Patients

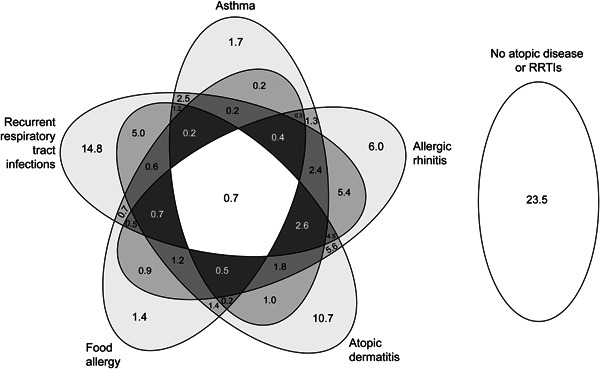

The median age of 5517 included children was 6 years (IQR: 3 to 10) and 43% were girls (Table 1). Children were included after referral to a secondary care center (56%), a tertiary care center (30%), or as part of the WHISTLER birth cohort (14%). Sixty‐two percent of children had one or more atopic disease(s), 42% had RRTIs, and 23% had no atopic diseases or RRTIs (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the cohort (n = 5517)

| Demographics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), y | 6.00 (3‐10) |

| Female sex | 2370 (43) |

| Inclusion center | |

| Secondary care | 3064 (56) |

| Tertiary care | 1676 (30) |

| Birth cohort | 777 (14) |

| Gestational age | |

| <37 wk | 607 (11) |

| 37‐43 wk | 4807 (87) |

| ≥43 wk | 103 (2) |

| Low birth weight | 429 (8) |

| Dutch maternal ethnicity | 5116 (93) |

| Dutch paternal ethnicity | 4999 (91) |

| Maternal education level | |

| Low | 528 (10) |

| Middle | 1888 (34) |

| High | 3101 (56) |

| Paternal education level | |

| Low | 612 (11) |

| Middle | 1944 (35) |

| High | 2961 (54) |

| Environment | |

| Exclusive breastfeeding | |

| Never | 3583 (65) |

| <6 mo | 948 (17) |

| ≥6 mo | 987 (18) |

| Pacifier use | 3600 (65) |

| Having siblings | 4349 (79) |

| Daycare attendance | 4688 (85) |

| Urban living environment | 2360 (43) |

| Having a pet dog | 972 (18) |

| Having a pet cat | 971 (18) |

| Maternal smoking during pregnancy | 221 (4) |

| Indoor smoking | 287 (5) |

| Adopted | 71 (1) |

| Vaccinated (complete age‐appropriate) | 4946 (90) |

| Flooring house | |

| Solid | 5409 (98) |

| Carpet | 108 (2) |

| Flooring bedroom child | |

| Solid | 4594 (83) |

| Carpet | 924 (17) |

| Family history | |

| Asthma | 2230 (41) |

| Allergic rhinitis | 3610 (65) |

| Atopic dermatitis | 3312 (60) |

| Food allergy | 1926 (35) |

| RRTIs | 3103 (56) |

| Disease outcome child | |

| Asthma | 958 (17) |

| Allergic rhinitis | 1919 (35) |

| Atopic dermatitis | 2083 (38) |

| Food allergy | 552 (10) |

| Recurrent respiratory tract infections (RRTIs) | 2336 (42) |

| Combined disease outcome child | |

| Any atopic disease | 3408 (62) |

| Both any atopic disease and RRTIs | 1523 (28) |

| No atopic disease and no RRTIs | 1295 (23) |

Note: Percentages do not always add up to 100 due to rounding.

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; n, number; RRTI, recurrent respiratory tract infections.

Figure 1.

Venn diagram displaying the proportion of atopic diseases and respiratory tract infections in all included children. The numbers are percentages

3.2. Risk factors for atopic diseases and RRTIs

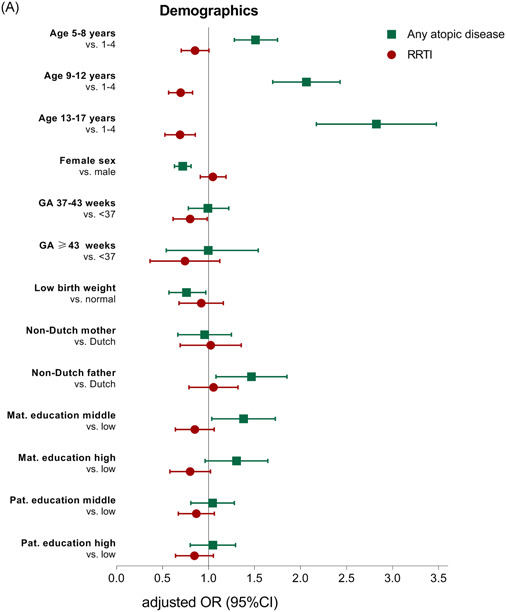

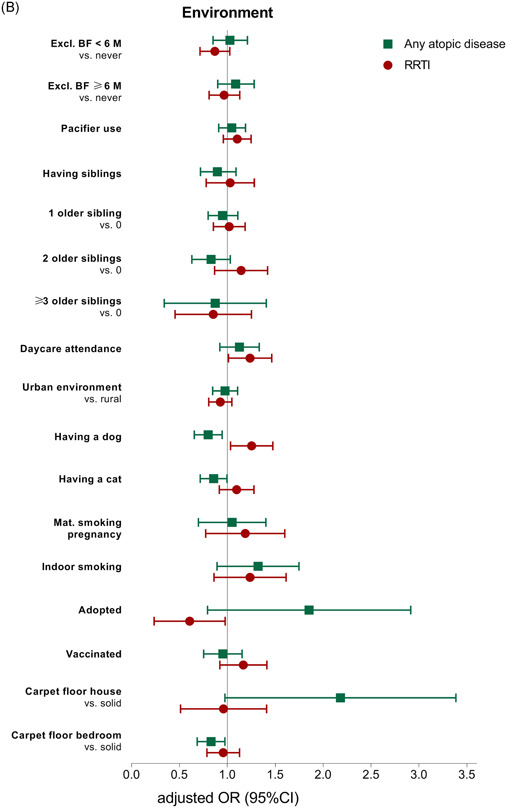

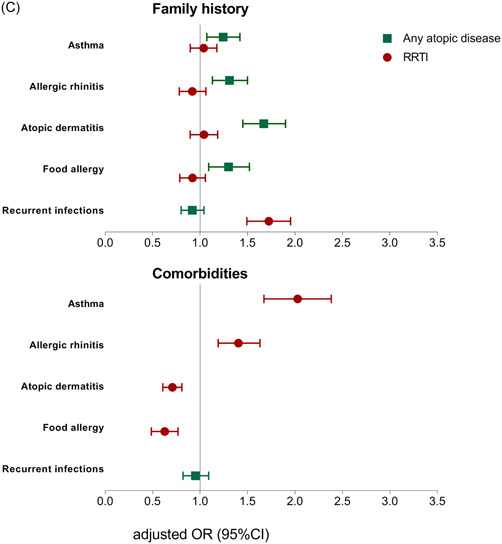

Table 2 and Figure 2 report the results from the multivariable regression analyses, exploring the association between demographic, environmental, and family history risk factors and the presence of any atopic disease or RRTIs. Table 3 reports the results from the multivariable regression analyses per individual atopic disease entity. The results of the univariable analyses are presented in Tables S2 and S3.

Table 2.

Independent risk factors for respectively any atopic disease and RRTIs

| Any atopic disease | RRTIs | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P value* | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P value* |

| Age, y | ||||

| 5‐8 (vs 1‐4) | 1.50 (1.28‐1.75) | <.001 | 0.84 (0.71‐1.01) | .06 |

| 9‐12 (vs 1‐4) | 2.04 (1.71‐2.44) | <.001 | 0.69 (0.57‐0.83) | <.001 |

| 13‐17 (vs 1‐4) | 2.77 (2.20‐3.50) | <.001 | 0.68 (0.53‐0.86) | <.01 |

| Female sex | 0.72 (0.63‐0.81) | <.001 | 1.04 (0.91‐1.19) | .54 |

| Gestational age, wk | ||||

| 37‐43 wk (vs <37) | 0.98 (0.78‐1.22) | .84 | 0.79 (0.62‐0.99) | <.05 |

| ≥ 43 wk (vs <37) | 0.91 (0.54‐1.54) | .72 | 0.68 (0.40‐1.15) | .15 |

| Low birth weight (vs normal) | 0.74 (0.57‐0.97) | .03 | 0.90 (0.69‐1.17) | .44 |

| Non‐Dutch mother (vs Dutch) | 0.93 (0.68‐1.26) | .63 | 0.99 (0.71‐1.37) | .95 |

| Non‐Dutch father (vs Dutch) | 1.43 (1.10‐1.87) | <.01 | 1.03 (0.80‐1.33) | .80 |

| Education level mother | ||||

| Middle (vs low) | 1.35 (1.05‐1.74) | .02 | 0.83 (0.65‐1.07) | .16 |

| High (vs low) | 1.27 (0.98‐1.66) | .08 | 0.78 (0.59‐1.03) | .08 |

| Education level father | ||||

| Middle (vs low) | 1.02 (0.82‐1.29) | .84 | 0.85 (0.68‐1.07) | .16 |

| High (vs low) | 1.03 (0.81‐1.30) | .82 | 0.83 (0.65‐1.06) | .14 |

| Environment | ||||

| Exclusive breastfeeding | ||||

| <6 mo (vs never) | 1.02 (0.85‐1.21) | .87 | 0.86 (0.72‐1.03) | .10 |

| ≥6 mo (vs never) | 1.08 (0.90‐1.28) | .41 | 0.96 (0.81‐1.13) | .61 |

| Pacifier use | 1.04 (0.91‐1.19) | .57 | 1.10 (0.96‐1.25) | .17 |

| Having siblings | 0.88 (0.72‐1.09) | .25 | 1.01 (0.79‐1.29) | .92 |

| Number of siblings | ||||

| 1 (vs 0) | 0.94 (0.80‐1.11) | .48 | 1.01 (0.86‐1.19) | .89 |

| 2 (vs 0) | 0.81 (0.64‐1.04) | .10 | 1.12 (0.88‐1.43) | .36 |

| ≥3 (vs 0) | 0.77 (0.40‐1.45) | .41 | 0.79 (0.49‐1.28) | .34 |

| Day care attendance | 1.11 (0.93‐1.34) | .24 | 1.22 (1.02‐1.47) | <.05 |

| Urban living environment (vs rural) | 0.97 (0.85‐1.11) | .63 | 0.92 (0.81‐1.05) | .23 |

| Having a pet dog | 0.79 (0.66‐0.95) | .01 | 1.24 (1.04‐1.48) | <0.05 |

| Having a pet cat | 0.85 (0.72‐1.00) | .05 | 1.09 (0.92‐1.28) | .34 |

| Maternal smoking during pregnancy | 1.01 (0.72‐1.42) | .96 | 1.14 (0.80‐1.62) | .47 |

| Indoor smoking | 1.27 (0.92‐1.77) | .15 | 1.20 (0.88‐1.63) | .26 |

| Adopted | 1.65 (0.91‐3.00) | .10 | 0.53 (0.28‐1.01) | .05 |

| Vaccinated | 0.94 (0.76‐1.16) | .56 | 1.15 (0.93‐1.42) | .19 |

| Carpet floor house (vs solid) | 1.96 (1.10‐3.48) | .02 | 0.89 (0.55‐1.44) | .64 |

| Carpet floor bedroom child (vs solid) | 0.82 (0.69‐0.98) | .03 | 0.95 (0.79‐1.13) | .55 |

| Family history | ||||

| Asthma | 1.24 (1.07‐1.42) | <.01 | 1.03 (0.90‐1.18) | .70 |

| Allergic rhinitis | 1.30 (1.13‐1.50) | <.001 | 0.91 (0.78‐1.06) | .23 |

| Atopic dermatitis | 1.66 (1.45‐1.90) | <.001 | 1.03 (0.90‐1.19) | .64 |

| Food allergy | 1.29 (1.09‐1.52) | <.01 | 0.91 (0.79‐1.06) | .23 |

| Recurrent respiratory infections | 0.91 (0.80‐1.04) | .18 | 1.71 (1.50‐1.96) | <.001 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Asthma | NA | 2.01 (1.68‐2.39) | <.001 | |

| Allergic rhinitis | NA | 1.39 (1.19‐1.63) | <.001 | |

| Atopic dermatitis | NA | 0.70 (0.61‐0.81) | <.001 | |

| Food allergy | NA | 0.62 (0.49‐0.77) | <.001 | |

| Recurrent respiratory infections | 0.94 (0.82‐1.09) | .44 | NA | |

Note: *Significant P values are in bold. Analyses were mutually adjusted for all risk factors within the model and for centre (secondary care, tertiary care, or birth cohort).

Abbreviations: adjusted OR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; NA, not applicable; RRTIs, recurrent respiratory tract infections.

Figure 2.

A, Association between demographic risk factors and any atopic disease and recurrent respiratory tract infections. CI, confidence interval; GA, gestational age; mat, maternal; OR, odds ratio; pat, paternal; RRTI, recurrent respiratory tract infections. B, Association between environmental risk factors and any atopic disease and recurrent respiratory tract infections. BF, exclusive breastfeeding; CI, confidence interval; excl. OR, odds ratio; RRTIs, recurrent respiratory tract infections. C, Association between family history and comorbidity risk factors and any atopic disease and recurrent respiratory tract infections. CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; RRTIs, recurrent respiratory tract infections [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Table 3.

Independent risk factors for individual atopic disease entities

| Asthma | Allergic rhinitis | Atopic dermatitis | Food allergy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P value* | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P value* | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P value* | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P value* |

| Age, y | ||||||||

| 5‐8 (vs 1‐4) | 3.07 (2.42‐3.89) | <.001 | 2.20 (1.83‐2.64) | <.001 | 0.77 (0.66‐0.90) | <.01 | 1.11 (0.86‐1.44) | .42 |

| 9‐12 (vs 1‐4) | 3.64 (2.83‐4.66) | <.001 | 4.02 (3.31‐4.87) | <.001 | 0.57 (0.48‐0.68) | <.001 | 1.13 (0.85‐1.49) | .41 |

| 13‐7 (vs 1‐4) | 5.21 (3.95‐6.87) | <.001 | 6.65 (5.25‐8.43) | <.001 | 0.44 (0.35‐0.55) | <.001 | 1.06 (0.75‐1.48) | .75 |

| Female sex | 0.83 (0.70‐0.97) | .02 | 0.70 (0.61‐0.81) | <.001 | 0.97 (0.86‐1.0) | .57 | 0.88 (0.72‐1.07) | .20 |

| Gestational age | ||||||||

| 37‐43 wk (vs <37) | 0.84 (0.64‐1.10) | .21 | 0.88 (0.69‐1.12) | .29 | 1.03 (0.83‐1.27) | .82 | 1.28 (0.88‐1.86) | .19 |

| ≥ 43 wk (vs <37) | 1.29 (0.72‐2.32) | .39 | 0.82 (0.47‐1.42) | .48 | 0.78 (0.47‐1.31) | .35 | 0.98 (0.42‐2.29) | .97 |

| Low birth weight (vs normal) | 1.04 (0.76‐1.43) | .80 | 0.72 (0.54‐0.96) | .02 | 0.89 (0.61‐1.02) | .07 | 1.09 (0.72‐1.63) | .69 |

| Non‐Dutch mother (vs Dutch) | 0.59 (0.37‐0.93) | .02 | 0.97 (0.70‐1.35) | .86 | 1.13 (0.84‐1.52) | .41 | 0.80 (0.51‐1.25) | .32 |

| Non‐Dutch father (vs Dutch) | 1.00 (0.71‐1.40) | .98 | 1.34 (1.03‐1.74) | .03 | 1.20 (0.94‐1.54) | .14 | 1.35 (0.92‐1.98) | .13 |

| Maternal education level | ||||||||

| Middle (vs low) | 1.16 (0.87‐1.55) | .31 | 1.22 (0.93‐1.59) | .16 | 1.12 (0.87‐1.44) | .38 | 0.99 (0.67‐1.45) | .95 |

| High (vs low) | 1.08 (0.78‐1.48) | .62 | 1.08 (0.82‐1.43) | .57 | 1.09 (0.84‐1.42) | .50 | 0.97 (0.65‐1.44) | .86 |

| Paternal education level | ||||||||

| Middle (vs low) | 0.78 (0.59‐1.02) | .07 | 1.19 (0.94‐1.52) | .16 | 0.99 (0.79‐1.24) | .93 | 1.27 (0.88‐1.85) | .20 |

| High (vs low) | 0.78 (0.58‐1.05) | .10 | 1.06 (0.82‐1.37) | .66 | 1.00 (0.79‐1.27) | .99 | 1.32 (0.90‐1.95) | .16 |

| Environment | ||||||||

| Exclusive breastfeeding | ||||||||

| <6 mo (vs never) | 0.99 (0.79‐1.24) | .94 | 1.04 (0.86‐1.25) | .68 | 1.04 (0.88‐1.22) | .65 | 0.92 (0.70‐1.20) | .53 |

| ≥6 mo (vs never) | 1.04 (0.84‐1.28) | .76 | 1.08 (0.90‐1.30) | .41 | 0.93 (0.78‐1.10) | .38 | 1.34 (1.04‐1.72) | .02 |

| Pacifier use | 1.28 (1.08‐1.52) | <.01 | 1.03 (0.89‐1.19) | .72 | 0.98 (0.86‐1.11) | .71 | 1.06 (0.87‐1.30) | .55 |

| Having siblings | 1.00 (0.73‐1.36) | .98 | 1.00 (0.80‐1.26) | .99 | 0.79 (0.65‐0.95) | .01 | 1.32 (0.96‐1.83) | .09 |

| Number of siblings | ||||||||

| 1 (vs 0) | 1.17 (0.96‐1.45) | .13 | 0.84 (0.71‐1.00) | <.05 | 1.06 (0.90‐1.24) | .48 | 0.86 (0.68‐1.10) | .22 |

| 2 (vs 0) | 1.14 (0.85‐1.52) | .38 | 0.71 (0.55‐0.91) | <.01 | 1.06 (0.84‐1.33) | .62 | 0.83 (0.59‐1.18) | .30 |

| ≥3 (vs 0) | 1.07 (0.54‐2.14) | .84 | 0.80 (0.45‐1.41) | .43 | 1.04 (0.671‐1.52) | .84 | 0.71 (0.38‐1.32) | .27 |

| Day care attendance | 1.04 (0.83‐1.31) | .71 | 1.16 (0.95‐1.42) | .14 | 0.97 (0.82‐1.16) | .74 | 1.19 (0.88‐1.60) | .26 |

| Urban living (vs rural) | 1.14 (0.96‐1.36) | .13 | 0.94 (0.82‐1.09) | .43 | 1.01 (0.89‐1.15) | .92 | 0.94 (0.77‐1.15) | .55 |

| Having a pet dog | 1.01 (0.81‐1.26) | .92 | 0.85 (0.70‐1.03) | .10 | 0.83 (0.69‐1.00) | .05 | 0.52 (0.38‐0.72) | <.001 |

| Having a pet cat | 0.91 (0.73‐1.14) | .41 | 0.71 (0.59‐0.87) | <.01 | 0.92 (0.78‐1.10) | .38 | 0.91 (0.69‐1.21) | .52 |

| Maternal smoking pregnancy | 1.26 (0.82‐1.94) | .29 | 1.16 (0.79‐1.68) | .45 | 0.57 (0.40‐0.82) | <.01 | 1.05 (0.61‐1.82) | .85 |

| Indoor smoking | 1.00 (0.69‐1.45) | .99 | 1.02 (0.73‐1.41) | .92 | 1.16 (0.85‐1.57) | .36 | 1.82 (1.18‐2.81) | .01 |

| Adopted | 1.58 (0.81‐3.09) | .18 | 1.00 (0.53‐1.84) | .98 | 1.62 (0.92‐2.84) | .09 | 0.39 (0.12‐1.28) | .12 |

| Vaccinated | 0.71 (0.56‐0.91) | <.01 | 0.82 (0.65‐1.04) | .10 | 1.11 (0.91‐1.36) | .29 | 1.36 (0.98‐1.89) | .07 |

| Carpet floor house (vs solid) | 1.46 (0.83‐2.57) | .20 | 1.35 (0.77‐2.32) | .28 | 1.17 (0.74‐1.85) | .50 | 0.94 (0.46‐1.91) | .986 |

| Carpet floor bedroom child | 0.82 (0.65‐1.05) | .12 | 0.88 (0.72‐1.07) | .19 | 0.85 (0.72‐1.01) | .07 | 1.11 (0.84‐1.46) | .45 |

| Family history | ||||||||

| Asthma | 2.20 (1.85‐2.61) | <.001 | 1.07 (0.9‐1.25) | .36 | 1.00 (0.88‐1.14) | .99 | 0.93 (0.75‐1.15) | .51 |

| Allergic rhinitis | 0.94 (0.78‐1.13) | .52 | 1.58 (1.35‐1.85) | <.001 | 1.13 (0.99‐1.30) | .08 | 1.21 (0.96‐1.54) | .11 |

| Atopic dermatitis | 1.17 (0.98‐1.41) | .09 | 1.00 (0.86‐1.17) | .97 | 1.72 (1.50‐1.98) | <.001 | 1.20 (0.95‐1.50) | .13 |

| Food allergy | 0.99 (0.82‐1.20) | .92 | 1.14 (0.96‐1.35) | .13 | 1.24 (1.06‐1.44) | <.01 | 1.20 (0.92‐1.57) | .18 |

| Recurrent respiratory infections | 0.88 (0.74‐1.06) | .17 | 1.17 (1.01‐1.36) | .04 | 0.89 (0.78‐1.02) | .08 | 0.85 (0.69‐1.05) | .13 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||||

| Asthma | NA | 1.77 (1.49‐2.10) | <.001 | 1.35 (1.14‐1.59) | <.001 | 1.46 (1.16‐1.86) | <.01 | |

| Allergic rhinitis | 1.79 (1.51‐2.13) | <.001 | NA | 2.11 (1.83‐2.43) | <.001 | 1.63 (1.33‐2.01) | <.001 | |

| Atopic dermatitis | 1.34 (1.14‐1.58) | <.01 | 2.11 (1.83‐2.44) | <.001 | NA | 1.60 (1.30‐1.95) | <.001 | |

| Food allergy | 1.46 (1.15‐1.86) | <.01 | 1.68 (1.36‐2.06) | <.001 | 1.61 (1.32‐1.96) | <.001 | NA | |

| Recurrent respiratory infections | 1.99 (1.67‐2.37) | <.001 | 1.38 (1.18‐1.61) | <.001 | 0.70 (0.61‐0.81) | <.001 | 0.63 (0.50‐0.80) | <.001 |

Note: *Significant P values are in bold. Analyses were mutually adjusted for all risk factors within the model and for centre (secondary care, tertiary care, or birth cohort).

Abbreviations: adjusted OR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

3.2.1. Demographic factors

Several demographic factors were associated with any atopic disease, while only age and gestational age were associated with RRTIs (Table 2 and Figure 2A). Children aged 5 years and older had a higher odds of any atopic disease (adjusted OR: 1.50‐2.77), but a lower chance of RRTIS (adjusted OR: 0.78‐0.84), compared to children aged less than 5 years. Female sex (OR: 0.72; 95% CI: 0.63‐0.81) and low birth weight (OR: 0.74; 95% CI: 0.57‐0.97) were associated with a reduced odds of any atopic disease. Children born between 37 and 43 weeks of gestation had a lower odds of RRTIs (OR: 0.79; 95% CI: 0.62‐0.99), compared to children born preterm.

When comparing the ORs per individual atopic disease entity, children aged 5 years and older had a higher chance of asthma (OR: 3.07‐5.21) and allergic rhinitis (adjusted OR: 2.20‐6.65) compared to children aged less than 5 years (Table 3). Children aged 5 years and older had a lower chance of atopic dermatitis (adjusted OR: 0.44‐0.77) compared to children aged less than 5 years. Female sex was associated with reduced odds of asthma (adjusted OR: 0.83; 95% CI: 0.70‐0.97) and allergic rhinitis (adjusted OR: 0.70; 95% CI: 0.61‐0.81). Low birth weight was associated with reduced odds of allergic rhinitis (adjusted OR: 0.72; 95% CI: 0.54‐0.96) only.

3.2.2. Environmental factors

Children who had a pet dog had a lower chance of any atopic disease (adjusted OR: 0.79; 95% CI: 0.66‐0.95). But a higher chance of RRTIs (adjusted OR: 1.24; 95% CI: 1.04‐1.48). Daycare attendance increased the odds of RRTIs (adjusted OR: 1.22; 95% CI: 1.02‐1.47) but was not associated with any atopic disease (Table 2 and Figure 2B).

In the analyses per individual atopic disease entity, children who had a pet dog had a lower odds of food allergy (adjusted OR: 0.52; 95% CI: 0.38‐0.72) (Table 3). Furthermore, children who had a pet cat had a lower chance of allergic rhinitis (adjusted OR: 0.71; 95% CI: 0.59‐0.87). In addition, children with one or two siblings had a lower chance of allergic rhinitis (adjusted OR: 0.84; 95% CI: 0.71‐0.99 and adjusted OR: 0.71; 95% CI: 0.55‐0.91, respectively). Children who were exclusively breastfed for 6 months or longer had a higher chance of food allergy (adjusted OR: 1.34; 95% CI: 1.04‐1.72). An unexpected finding was that we observed an inverse association between maternal smoking during pregnancy and atopic dermatitis (adjusted OR: 0.57; 95% CI: 0.40‐0.82).

3.2.3. Family history

The associations between family history and disease outcomes were disease‐specific. Children who reported a family history of one of the atopic diseases were more likely to have any atopic disease, but were not likely to have more RRTIs (Table 2 and Figure 2C). Children who reported a family history of recurrent infections were more likely to have RRTIs (adjusted OR: 1.71; 95% CI: 1.50‐1.96) but were not likely to have more atopic disease.

In the analyses per individual atopic disease entity, the disease‐specific association between family history and disease outcome was further confirmed for asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis (adjusted OR: 2.20, 1.58, 1.72, respectively) (Table 3).

3.2.4. Child's comorbidity

The concurrent presence of RRTIs was not associated with having any atopic diseases (adjusted OR: 0.94; 95% CI: 0.82‐1.09) (Table 2 and Figure 2C). However, children who had asthma or allergic rhinitis were more likely to have RRTIs (adjusted OR: 2.01; 95% CI: 1.68‐2.39 and adjusted OR: 1.39; 95% CI: 1.19‐1.63, respectively). On the contrary, the concurrent presence of atopic dermatitis or food allergy reduced the odds of having RRTIs (adjusted OR: 0.70; 95% CI: 0.61‐0.81 and adjusted OR: 0.62; 95% CI: 0.49‐0.77).

In the analysis per individual atopic disease entity, the concurrent presence of another atopic disease increased the odds of the outcome atopic disease (adjusted OR ranging between 1.34 and 2.11) (Table 3). Although the concurrent presence of RRTIs was not associated with having any atopic diseases, having RRTIs was associated with individual atopic disease entities. Children who reported RRTIs were more likely to have asthma (adjusted OR: 1.99; 95% CI: 1.67‐2.37) and allergic rhinitis (adjusted OR: 1.38; 95% CI: 1.18‐1.61), but less likely to have atopic dermatitis (adjusted OR: 0.70; 95% CI: 0.61‐0.81) and food allergy (adjusted OR: 0.63; 95% CI: 0.50‐0.80).

4. DISCUSSION

Here, we present an overview of demographic, environmental, and family history risk factors for atopic diseases compared to risk factors for recurrent RRTIs in a large cohort of Dutch children. Our data show that risk factors for atopic diseases and RRTIs differ. As an example, girls, children with low birth weight and children with a pet dog were more likely to have atopic diseases but were not more likely to have RRTIs. Furthermore, corresponding family history was a disease‐specific risk factor for both atopic diseases and for RRTIs.

Children aged 5 years and older had a higher chance of asthma and allergic rhinitis compared to children younger than 5 years, while older children had a lower chance of atopic dermatitis and RRTIs These findings are consistent with the so‐called “atopic march.” 16 The atopic march is thought to start with atopic dermatitis, followed by food allergy, asthma, and allergic rhinitis. In addition, our data showed that the concurrent presence of RRTIs increased the odds of having asthma or allergic rhinitis, while it reduced the odds of having atopic dermatitis. Children with atopic diseases may be more susceptible to respiratory infections due to airway inflammation and impaired innate immune function. 17 , 18 On the contrary, other studies have proposed that infections may stimulate a patient's protective immunity and hereby reduce the risk of atopic diseases. 19 Although a causal relationship cannot be demonstrated in this cross‐sectional study, these data suggest that the association between RRTIs and atopic diseases may be different per individual atopic disease entity. Furthermore, female sex was associated with reduced odds of atopic diseases as has been previously acknowledged. 20 Epidemiological studies have reported a predominance of atopic diseases in males before puberty and in females after puberty, possibly explained by hormonal influences or sex‐specific genetic, environmental, or social factors. 21 We did not observe an association between sex and RRTIs, although previous studies suggest that males are more susceptible to most types of respiratory tract infections. 22 The possible protective effect of low birth weight on atopic disease has been previously reported, 23 and may be explained by differences in immune system development, gastrointestinal tract permeability, and exposure to antigens between children with low and normal birth weight.

We found an increased risk of food allergy in children who were exclusively breastfed for more than 6 months. These children may have introduced allergenic foods later in life. Our data consolidate existing evidence that early introduction of allergenic foods prevents the development of food allergies. 24 Daycare attendance increased the risk of RRTIs as has been acknowledged in previous research. 9 The finding that dog ownership was associated with a reduced risk of atopic diseases confirms evidence that having a pet dog protects against atopic diseases and sensitization. 7 The possible protective effect of pet ownership might be explained by an immunomodulatory effect of exposure to allergens, endotoxins, or bacteria 7 or by affecting DNA methylation. 25 However, the protective effect of pet ownership may be partly attributed to selective avoidance of pets in households with allergic family members (reverse causality). 26

The association between family history and the child's outcome was disease‐specific, that is, children with asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, or RRTIs were significantly more likely to have a parent and/or sibling reporting the same condition. Especially the association between family history and RRTIs is intriguing and requires further investigation, as it has not been described before. A family history of RRTIs is often overlooked although it is particularly important to identify children at increased risk of RRTIs and children with genetic disorders or immune deficiencies. 27 Given the rarity of single‐gene immunodeficiency diseases, 28 it is suggestive that this association can be more readily explained by a polygenic inheritance pattern. Host genetic factors have been implicated in respiratory infections of varying aetiology, but no consistent associations are observed. 29 Most likely, gene‐environment interactions play a role in the pathogenesis of both atopic diseases and RRTIs. Regardless of the aetiology of the observed association between family history and disease phenotype, our results do emphasize the importance of assessing the family history when confronted with a child with suspected atopic disease or RRTIs.

There are a number of limitations to our study. First, this was a questionnaire‐based survey. Thus, we measured the self‐reported prevalence of atopic diseases and RRTIs without objectively assessing clinical parameters such as lung capacity by spirometry or specific immunoglobulin E results. However, we did use validated and widely used instruments including the ISAAC questionnaires. 14 A second limitation to our study is the cross‐sectional study design. As we measured the prevalence rather than the incidence of diseases, it remains unknown whether the identified factors are a risk factor involved in the aetiology of the diseases. This study is strengthened by standardized data collection in a large group of children from both a birth cohort and hospital setting.

5. CONCLUSIONS

To conclude, our findings indicate that the demographic, environmental, and family history risk factors for atopic diseases are distinct from the risk factors for RRTIs. Thus, the changing prevalence of both disease entities might not be related to shared risk factors.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.

Supporting information

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the members of the Expert Network, D.M.W. Gorissen (Department of Pediatrics, Deventer Hospital, Deventer, The Netherlands), B.E. van Ewijk (Department of Pediatrics, Tergooi Hospital, Blaricum/Hilversum, The Netherlands), W.A.F. Balemans (Department of Pediatrics, St Antonius Hospital, Nieuwegein, The Netherlands), M.F. van Velzen (Department of Pediatrics, Meander Medical Centre, Amersfoort, The Netherlands), P.F. Eskes (Department of Pediatrics, Meander Medical Centre, Amersfoort, The Netherlands), G. Slabbers (Department of Pediatrics, Bernhoven Hospital, Uden, The Netherlands), R. van Gent (Department of Pediatrics, Máxima Medical Centre, Veldhoven, The Netherlands), and participant of the Electronic Portal, M. Stadermann, for their collaboration and work within their centers.

The study was partly supported by a grant from the WKZ Utrecht (Wilhelmina Children's Hospital) Research Fund (contact name Dr Lilly M. Verhagen). Dr Lilly M. Verhagen also received a Fellowship clinical research talent UMC Utrecht. The Electronic Portal was supported by an unrestricted grant of GlaxoSmithKline (contact name Prof Dr Cornelis K. van der Ent).

Kansen HM, Lebbink MA, Mul J, et al. Risk factors for atopic diseases and recurrent respiratory tract infections in children. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2020;55:3168–3179. 10.1002/ppul.25042

Sabine M.P.J. Prevaes, and Cornelis K. van der Ent are members of ERN‐LUNG.

Hannah M. Kansen and Melanie A. Lebbink contributed equally.

REFERENCES

- 1. Asher MI, Montefort S, Björkstén B, et al. Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood. Lancet. 2006;368(9537):733‐743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nwaru BI, Hickstein L, Panesar SS, et al. The epidemiology of food allergy in Europe: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Allergy. 2014;69(1):62‐75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Platts‐Mills TAE. The allergy epidemics: 1870‐2010. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136(1):3‐13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Troeger C. Estimates of the global, regional, and national morbidity, mortality, and aetiologies of lower respiratory infections in 195 countries, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(11):1191‐1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bach J. The effect of infections on susceptibility to autoimmune and allergic diseases. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(12):911‐920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yazdanbakhsh M, Kremsner PG, Van Ree R. Allergy, parasites and the hygiene hypothesis. Science. 2002;296(5567):490‐494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mandhane PJ, Sears MR, Poulton R, et al. Cats and dogs and the risk of atopy in childhood and adulthood. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124(4):745‐750.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Benn CS, Melbye M, Wohlfahrt J, Björkstén B, Aaby P. Cohort study of sibling effect, infectious diseases, and risk of atopic dermatitis during first 18 months of life. Br Med J. 2004;328(7450):1223‐1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hagerhed‐Engman L, Bornehag CG, Sundell J, Åberg N. Day‐care attendance and increased risk for respiratory and allergic symptoms in preschool age. Allergy Eur J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;61(4):447‐453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Toivonen L, Karppinen S, Schuez‐Havupalo L, et al. Burden of recurrent respiratory tract infections in children: a prospective cohort study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016;35(12):e362‐e369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gallant MJ, Ellis AK. What can we learn about predictors of atopy from birth cohorts and cord blood biomarkers? Ann Allergy, Asthma, Immunol. 2018;120(2):138‐144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zomer‐Kooijker K, van Erp FC, Balemans WAF, van Ewijk BE, van der Ent CK. The expert network and electronic portal for children with respiratory and allergic symptoms: rationale and design. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13(1):9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Katier N, Uiterwaal CS, de Jong BM, et al. Study Leidsche Rijn (WHISTLER): rationale and design. Eur J Epidemiol. 2004;19(9):895‐903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Asher MI, Keil U, Anderson HR, et al. International study of asthma and allergies in childhood (ISAAC): rationale and methods. Eur Respir J. 1995;8(3):483‐491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Grüber C, Keil T, Kulig M, et al. History of respiratory infections in the first 12 yr among children from a birth cohort. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2008;19(6):505‐512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hill DA, Spergel JM. The atopic march: critical evidence and clinical relevance. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;120(2):131‐137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Busse WW, Lemanske RF Jr., Gern JE. The role of viral respiratory infections in asthma and asthma exacerbations. Lancet. 2010;376(9743):826‐834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mrabet‐Dahbi S, Maurer M. Does allergy impair innate immunity? Leads and lessons from atopic dermatitis. Allergy. 2010;65:1351‐1356. 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02452.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cruz AA, Cooper PJ, Figueiredo CA. Global issues in allergy and immunology: parasitic infections and allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;140(5):1217‐1228. 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pali‐Schöll I, Jensen‐Jarolim E. Gender aspects in food allergy. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;19(3):249‐255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chen W, Mempel M, Schober W, Behrendt H, Ring J. Gender difference, sex hormones, and immediate type hypersensitivity reactions. Allergy Eur J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;63(11):1418‐1427. 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01880.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Falagas ME, Mourtzoukou EG, Vardakas KZ. Sex differences in the incidence and severity of respiratory tract infections. Respir Med. 2007;101(9):1845‐1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Siltanen M, Wehkalampi K, Hovi P, et al. Preterm birth reduces the incidence of atopy in adulthood. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(4):935‐942. 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.12.1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Du Toit G, Roberts G, Sayre PH, et al. Randomized trial of peanut consumption in infants at risk for peanut allergy. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(9):803‐813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Qi C, Jiang Y, Yang IV, et al. Nasal DNA methylation profiling of asthma and rhinitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145:1‐9. 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.12.911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Svanes C, Zock JP, Antó J, et al. Do asthma and allergy influence subsequent pet keeping? An analysis of childhood and adulthood. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118(3):691‐698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. de Benedictis FM, Bush A. Recurrent lower respiratory tract infections in children. BMJ. 2018;362(July):k2698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Picard C, Bobby Gaspar H, Al‐Herz W, et al. International Union of Immunological Societies: 2017 Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases Committee report on inborn errors of immunity. J Clin Immunol. 2018;38(1):96‐128. 10.1007/s10875-017-0464-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Patarčić I, Gelemanović A, Kirin M, et al. The role of host genetic factors in respiratory tract infectious diseases: systematic review, meta‐analyses, and field synopsis. Sci Rep. 2015;5(October):1‐10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information