Abstract

Objective

Damage to the vascular endothelium is strongly implicated in the pathogenesis of idiopathic inflammatory myopathies (IIM). Normally, high‐density lipoprotein (HDL) protects the vascular endothelium from damage from oxidized phospholipids, which accumulate under conditions of oxidative stress. The current work evaluated the antioxidant function of HDL in IIM patients.

Methods

HDL’s antioxidant function was measured in IIM patients using a cell-free assay, which assesses the ability of isolated patient HDL to inhibit oxidation of low-density lipoproteins and is reported as the HDL inflammatory index (HII). Cholesterol profiles were measured for all patients, and subgroup analysis included assessment of oxidized fatty acids in HDL and plasma MPO activity. A subgroup of IIM patients was compared with healthy controls.

Results

The antioxidant function of HDL was significantly worse in patients with IIM (n = 95) compared with healthy controls (n = 41) [mean (S.d.) HII 1.12 (0.61) vs 0.82 (0.13), P < 0.0001]. Higher HII associated with higher plasma MPO activity [mean (S.d.) 13.2 (9.1) vs 9.1 (4.6), P = 0.0006] and higher oxidized fatty acids in HDL. Higher 5-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid in HDL correlated with worse diffusion capacity in patients with interstitial lung disease (r = −0.58, P = 0.02), and HDL’s antioxidant function was most impaired in patients with autoantibodies against melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5 (MDA5) or anti-synthetase antibodies. In multivariate analysis including 182 IIM patients, higher HII was associated with higher disease activity and DM diagnosis.

Conclusion

The antioxidant function of HDL is abnormal in IIM patients and may warrant further investigation for its role in propagating microvascular inflammation and damage in this patient population.

Keywords: dermatomyositis, polymyositis, cardiovascular disease

Rheumatology key messages

The antioxidant function of high-density lipoprotein in idiopathic inflammatory myopathy patients was abnormal compared with controls.

MPO activity correlated with higher oxidized fatty acids in high-density lipoprotein, and worse high-density lipoprotein antioxidant function.

Impaired high-density lipoprotein antioxidant function was associated with higher idiopathic inflammatory myopathy disease activity and dermatomyositis diagnosis.

Introduction

DM is an idiopathic inflammatory myopathy (IIM) that is associated with marked activation and damage to small blood vessels in connective tissue of the muscle, skin and gastrointestinal tract [1, 2]. Capillary loss precedes other pathological muscle changes, and the inflammatory infiltrate in DM is predominantly perivascular and perimysial [3]. Vascular damage is considered integral to the disease pathogenesis in DM, and to a lesser degree in PM and IBM, which also demonstrate activated capillaries with increased adhesion molecule expression [4].

High-density lipoprotein (HDL) protects the vascular endothelium from damage due to oxidized phospholipids, which accumulate under conditions of oxidative stress. Impaired function of HDL has previously been identified in inflammatory diseases including SLE, RA and atherosclerosis [5]. Oxidized fatty acids including hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids (HETEs) and hydroxyoctadecadienoic acids (HODEs) not only contribute to the oxidation of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) but their accumulation in HDL also impairs HDL function, increasing risk of vascular damage [6, 7].

Although it is well established that oxidized lipids and HDL strongly influence the vascular endothelium [5, 6], the level and function of these lipoproteins in patients with IIM has not been previously evaluated. In the current work, we investigate the antioxidant function of HDL in IIM patients compared with healthy controls, and in a large cohort of IIM patients.

Methods

Study design

Myositis patients and healthy controls were recruited from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). All myositis patients met EULAR/ACR classification criteria for at least ‘probable’ adult IIM and subclasses including DM, PM and IBM, which was verified by chart review [8]. All subjects gave written informed consent for the study under a protocol approved by the Human Research Subject Protection Committee at UCLA (IRB# 10-001833). Subjects or funders were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of our research.

Initial analysis was designed to compare IIM patients with healthy controls (HC) (IIM/HC comparison cohort). The first 95 patients enrolled in the UCLA IIM cohort were compared with 41 HC who were recruited for the study during the same time period. Subgroup analyses for oxidized lipids were performed from the initial patient cohorts and included 12 DM, 12 PM and 12 HC matched for age. Subsequently, we further expanded the IIM cohort to all patients enrolled in the study through the time of analysis (expanded disease-specific cohort) to assess the association of HDL’s antioxidant function with disease-specific characteristics and disease activity level.

Patients provided a blood sample and completed questionnaires regarding cardiovascular risk and health information. Assessment of creatine phosphokinase (CPK), inflammatory markers including high-sensitivity CRP (hsCRP), Westergren ESR and fasting lipid profiles were performed by the UCLA clinical laboratory using standard methods. Myositis-specific antibodies (MSA) were assessed using standardized lab protocols (95 by the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation and 16 from other clinical labs). Additional blood was collected in heparinized tubes (Becton Dickinson, Mississauga, ON, Canada), which were centrifuged at 2400 revolutions per min for 20 min and plasma separated and stored at −80°C for additional assays as described below. Disease activity and damage were assessed using physician global myositis disease activity and damage scales by 100 mm visual analogue scale (VAS) and 5-point Likert scale [9]. Interstitial lung disease (ILD) was defined by radiographic findings consistent with ILD on high-resolution CT showing at least one of the following features: reticulation and fibrosis, traction bronchiectasis, honeycombing or ground glass opacification [10].

Evaluation of HDL antioxidant function

The cell-free assay was a modification of a previously published method using LDL as the fluorescence-inducing agent [11]. HDL was isolated by dextran bead precipitation. To determine the anti-inflammatory properties of HDL, the change in fluorescence intensity as a result of the oxidation of 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA) (ThermoFisher Scientific) to 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein (DCF) in incubations with a standard LDL in the absence or presence of the test HDL was assessed and the HDL inflammatory index (HII) calculated. Readings with H2DCFDA and LDL cholesterol were normalized to 1.0. In brief, as described previously, 25 μl of LDL-cholesterol (100 μg/ml) was mixed with 50 μl of test HDL (100 μg HDL-cholesterol/ml) in black, flat bottom polystyrene microtitre plates and incubated at 37°C with rotation for 30 min. Twenty-five microlitres of H2DCFDA solution (0.2 mg/ml) was added to each well, mixed, and incubated at 37°C for 1 h with rotation. Fluorescence was determined with a plate reader (Spectra Max, Gemini XS Molecular Devices) at an excitation wavelength of 485 nm, emission wavelength of 530 nm and cutoff of 515 nm with photomultiplier sensitivity set at medium. Values for intra- and interassay variability were 0.5 (0.37)% and 3.0 (1.7)%, respectively [12].

Determination of HETEs and HODES in HDL

HDL was isolated by ultracentrifugation from plasma and 5-HETE, 12-HETE, 15-HETE, 9-HODE and 13-HODE levels in HDL were measured by liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization, tandem mass spectroscopy as described previously [7, 13].

MPO activity

The activity of MPO was measured using the InnoZyme MPO activity assay kit (EMD Chemicals, Darmstadt, Germany) as described previously [14].

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using JMP IN 13.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Patient groups were compared using Student’s t-test or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous variables and the χ2 test of association for categorical variables. Correlations between variables were evaluated using the Pearson’s or Spearman’s correlation coefficient, depending on the data distribution. The significance level was pre-specified at two-sided P < 0.05. For multivariate regression analyses, model covariates included demographics, patient variables significantly associated with HDL’s antioxidant function in univariate analysis, and variables known to be associated with HDL’s antioxidant function including age and statin use. The antioxidant function of HDL was examined both as a continuous variable in linear regression analysis (HII), and as a categorical variable (tertile HII) in logistic regression analyses of the IIM cohort. In linear models, HII, hsCRP and CPK were log-transformed due to skewness. Because physician global disease activity and CPK levels were significantly correlated, two separate multivariate models were performed to evaluate each disease activity measure individually.

Results

Antioxidant function of HDL is abnormal in IIM when compared with HC (IIM/HC comparison cohort)

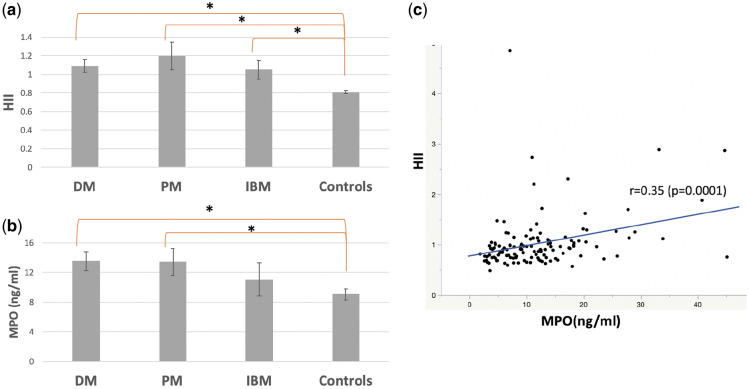

The antioxidant function of HDL as measured by its ability to inhibit oxidation of LDL was significantly worse in patients with IIM (n = 95) when compared with age- and sex-matched HC (n = 41) [mean (S.d.) HII 1.12 (0.61) vs 0.82 (0.13), P < 0.0001] (Table 1, Fig. 1a). Plasma MPO activity was higher in DM/PM patients compared with HC [mean (S.d.) 13.2 (9.1) vs 9.1 (4.6), P = 0.0006] (Fig. 1b) and correlated with impaired HDL antioxidant function measured by a higher HII in the IIM/HC cohort (n = 136, r = 0.35, P = 0.0001, Fig. 1c). MPO also correlated with HII in the IIM group alone (r = 0.36, P = 0.0005).

Table 1.

HDL function in IIM patients and healthy controls (IIM/HC comparison cohort, n = 136)

| DM | PM | IBM | Control | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 55) | (N = 30) | (N = 10) | (N = 41) | |

| HII | 1.09 (0.49)*** | 1.20 (0.84)*** | 1.05 (0.31)*** | 0.82 (0.13) |

| Age, years | 48 (15) | 54 (13) | 65 (14)* | 49 (14) |

| Gender, female n (%) | 43 (78) | 20 (67) | 6 (60) | 28 (68) |

| Race, n (%)** | ||||

| White | 49 (89) | 16 (54) | 7 (70) | 32 (78) |

| Black | 2 (4) | 10 (33) | 2 (20) | 0 (0) |

| Asian | 4 (7) | 4 (13) | 1 (10) | 9 (22) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| Hispanic | 16 (29) | 3 (10) | 1 (10) | 11 (27) |

| Hs-CRP (mg/l) | 7.8 (11.3)*** | 6.7 (9.0)*** | 1.8 (2.4)**** | 2.7 (3.8) |

| ESR (mm/h) | 29 (29)*** | 30 (20)*** | 25 (21) | 12 (13) |

| CPK (U/l) | 325 (795) | 573 (759) | 474 (508) | – |

| Lipid panel (mg/dl) | ||||

| Total cholesterol | 199 (41) | 215 (61)*** | 186 (46) | 191 (33) |

| LDL cholesterol | 114 (36) | 117 (46) | 95 (40) | 109 (28) |

| HDL cholesterol | 55 (18) | 62 (29) | 55 (13) | 58 (19) |

| Triglycerides | 157 (95)*** | 186 (146)*** | 175 (89)*** | 123 (82) |

| CVD risk factors, n (%) | ||||

| History of MI | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | 0 | 0 |

| Hypertension** | 13 (24) | 10 (33) | 5 (50) | 8 (20) |

| Diabetes** | 5 (9) | 8 (27) | 3 (30) | 1 (2) |

| Ever smoker | 1 (2) | 2 (7) | 1 (10) | 1 (2) |

| Family history of MI | 5 (9) | 3 (10) | 1 (10) | 3 (7) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31 (8) | 30 (8) | 25 (4) | 27 (7) |

| Statin use | 5 (9) | 2 (7) | 2 (20) | 2 (5) |

| MPO (ng/ml) | 14 (9)† | 13 (10)† | 11 (7) | 9 (5) |

| Medications n (%) use | ||||

| MTX | 16 (29) | 5 (20) | 0 | – |

| TNF inhibitor | 3 (5) | 2 (6) | 0 | – |

| LEF | 2 (4) | 1 (3) | 0 | – |

| MMF** | 9 (16) | 9 (30) | 0 | – |

| AZA | 9 (16) | 7 (23) | 0 | – |

| HCQ | 12 (22) | 6 (20) | 1 (10) | – |

| Immunoglobulins | 13 (24) | 5 (17) | 0 | – |

| Rituximab | 1 (2) | 4 (13) | 0 | – |

| CYC | 4 (7) | 2 (6) | 0 | – |

| Prednisone** | 37 (67) | 27 (90) | 5 (50) | – |

| Prednisone dose | 14 (16) | 21 (27) | 6 (7)**** | – |

| ILD, n (%)** | 18 (33) | 14 (47) | 0 (0) | – |

Values are mean (S.d.) unless specified.

P < 0.05 compared with all other groups.

P < 0.05 on χ2 test.

P < 0.05 compared with HC.

P < 0.05 compared with PM. HDL: high-density liopoprotein; IIM: idiopathic inflammatory myopathies; HII: HDL inflammatory index; HC: healthy controls; hs-CRP: high sensitivity CRP; CPK: creatine phosphokinase; LDL: low-density lipoprotein; CVD: cardiovascular disease; MI: myocardial infarction; ILD: interstitial lung disease; HMGCR: 3-Hydroxy-3-Methylglutaryl-Coenzyme A Reductase; SRP: signal recognition particle. Patients with anti-HMCGR or anti-SRP-mediated immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy were included as DM (N = 2) or PM (N = 11).

Fig. 1.

HII and MPO in the IIM/HC comparison cohort

(a) HDL function (HII) in IIM (55 DM, 30 PM, 10 IBM) and HC (n = 41), mean (S.e.). (b) MPO in IIM and HC, mean (S.e.). (c) Correlation between HII and MPO in IIM and controls, *P < 0.05. IIM: idiopathic inflammatory myopathies; HII: HDL inflammatory index; HC: healthy controls; HDL: high-density lipoprotein.

Cardiovascular (CV) risk factors and traditional cholesterol levels were compared between the two groups (Table 1). The IIM patient group had a higher proportion of patients with hypertension and diabetes, and had higher total cholesterol and triglyceride levels compared with HC. Other traditional cardiovascular risk factors were similar between the two groups. DM and PM patients also had higher levels of systemic inflammation compared with HC (Table 1), which did not correlate with HII (r = 0.11, P = 0.20 for hsCRP, r = 0.13, P = 0.14 for ESR).

Multivariate regression analysis of HDL antioxidant function (HII) was performed to evaluate whether IIM diagnosis and higher MPO activity remained associated with impaired HDL antioxidant function after adjustment for other differences between IIM and HC (supplementary Table S1, available at Rheumatology online). IIM diagnosis (vs HC) and higher plasma MPO activity remained significantly associated with impaired antioxidant function of HDL (higher HII) in multivariate analysis after controlling for demographics (age, sex), other variables that were significant in univariate analysis (ever smoker, triglycerides) and statin use.

Increased oxidation products of arachidonic acid and linoleic acid in HDL in IIM

Oxidized fatty acids were assessed in age-matched DM, PM and HC (n = 12 in each group). Levels of oxidized fatty acids were significantly higher in HDL from IIM patients compared with HC (Table 2) and associated with abnormal HDL antioxidant function. In particular, 5-HETE, 15-HETE, 9-HODE and 13-HODE levels were significantly increased in HDL from patients with PM compared with HC (supplementary Fig. S1, available at Rheumatology online) and higher 5-HETE significantly associated with worse HDL antioxidant function measured by a higher HII (r = 0.41, P = 0.01, supplementary Fig. S2a, available at Rheumatology online). HDL-associated 13-HODE also showed a modest trend for association with worse HDL antioxidant function (r = 0.30, P = 0.08). Higher MPO activity correlated with higher HDL-associated 5-HETE (r = 0.46, P = 0.007, supplementary Fig. S2b, available at Rheumatology online), 12-HETE (r = 0.23, P = 0.19), 15-HETE (r = 0.38, P = 0.03), 9-HODE (r = 0.40, P = 0.02) and 13-HODE (r = 0.41, P = 0.02).

Table 2.

Oxidized fatty acid levels in HDL from IIM patients and HC

| IIM (N = 24) | HC (N = 12) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 50 (8) | 48 (13) |

| Sex, female, n (%) | 17 (71) | 8 (67) |

| Race, White n (%) | 14 (58) | 10 (53) |

| Ethnicity, Hispanic, n (%) | 7 (29) | 5 (42) |

| Hs-CRP (mg/l) | 10.8 (11.7)* | 0.6 (0.5) |

| ESR (mm/h) | 46 (24)* | 6 (7) |

| CVD risk factors | ||

| History of MI, n (%) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 8 (47)* | 1 (8) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 5 (28) | 0 (0) |

| Ever smoker, n (%) | 2 (14) | 0 (0) |

| FHx of MI, n (%) | 4 (27)* | 0 (0) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 33 (9)* | 24 (4) |

| Statin use, n (%) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Lipid panel (mg/dl) | ||

| Total cholesterol | 197 (45) | 184 (28) |

| LDL cholesterol | 118 (44) | 112 (25) |

| HDL cholesterol | 59 (29) | 55 (13) |

| Triglycerides | 137 (57)* | 90 (39) |

| HII | 1.34 (0.56)* | 0.80 (0.15) |

| MPO (ng/ml) | 19 (9)* | 8 (3) |

| HETE/HODE (pg/75 μg HDL cholesterol) | ||

| 5-HETE | 48 792 (28 922)* | 12 721 (4493) |

| 12-HETE | 698 (650)* | 321 (234) |

| 15-HETE | 27 (21)* | 12 (9) |

| 9-HODE | 161 (148)* | 57 (97) |

| 13-HODE | 390 (279)* | 158 (111) |

Values reported in mean (S.d.) unless specified. P < 0.05. HDL: high-density liopoprotein; IIM: idiopathic inflammatory myopathies; HC: healthy controls; hs-CRP: high sensitivity CRP; CVD, cardiovascular disease; MI, myocardial infarction; FHx, family history of premature MI; LDL: low-density lipoprotein; HII: HDL inflammatory index; HETE: hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids; HODE: hydroxyoctadecadienoic acids.

Patients with ILD showed modest trends for higher 5-HETE, 12-HETE, 15-HETE and 13-HODE levels in HDL compared with myositis patients without ILD (n = 10/24) (supplementary Table S2, available at Rheumatology online). More patients with PM had ILD (9/12) compared with patients with DM (5/12) (P = 0.09), which may have resulted in higher oxidized fatty acid levels in PM compared with DM patients. Patients with moderate to severe ILD [diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) <50%] also showed trends for higher HDL-associated 5-HETE, 12-HETE and 13-HODE levels compared with ILD patients with less severe ILD (DLCO ≥50%) (Table 3). HDL-associated 5-HETE (supplementary Fig. S2c, available at Rheumatology online) and 12-HETE levels were inversely correlated with DLCO (r = −0.58, P = 0.02 and r = −0.49, P = 0.05 respectively); higher levels of these oxidized fatty acids correlated with lower DLCO in ILD patients.

Table 3.

Clinical data of IIM patients by tertiles of HDL function (expanded disease-specific cohort, n = 182)

| Tertile 1 | Tertile 2 | Tertile 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 61) | (n = 61) | (n = 60) | |

| HII | 1.21 (0.62) | 0.53 (0.09) | 0.23 (0.05) |

| Age, years | 50 (14) | 51 (15) | 51 (15) |

| Gender, female, n (%) | 44 (72) | 42 (69) | 44 (73) |

| Race, White n (%) | 44 (72) | 50 (82) | 45 (75) |

| Ethnicity, Hispanic, n (%) | 13 (21) | 11 (18) | 10 (17) |

| ESR (mm/h) | 34 (29) | 28 (24) | 27 (25) |

| Hs-CRP (mg/l) | 7.7 (12.0) | 4.7 (8.3) | 6.5 (9.7) |

| Lipid panel (mg/dl) | |||

| Total cholesterol | 209 (50) | 210 (52) | 205 (50) |

| LDL cholesterol | 121 (44) | 128 (46) | 113 (3) |

| HDL cholesterol | 59 (24) | 57 (20) | 58 (19) |

| Triglycerides | 182 (137) | 156 (93) | 169 (124) |

| CVD risk factors, n (%) | |||

| History of MI, yes | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 2 (3) |

| Hypertension | 16 (26) | 18 (30) | 17 (28) |

| Diabetes | 7 (11) | 7 (11) | 10 (17) |

| Ever smoker | 11 (18) | 19 (32) | 12 (20) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.7 (6.3) | 27.8 (6.5) | 27.6 (5.8) |

| Statin use | 7 (11) | 5 (8) | 8 (14) |

| IIM characteristics | |||

| Disease duration, years | 4.5 (7.8)* | 3.6 (7.4) | 4.3 (5.0)** |

| DM disease diagnosis, n (%) | 46 (75) | 46 (75) | 30 (50)*** |

| CPK (U/l) | 867 (1989)** | 405 (1123) | 562 (1199) |

| Physician global activity (VAS 0–100 mm) | 43 (21)* | 40 (18) | 34 (17) |

| Physician global activity (Likert 0–4) | 1.89 (0.95) | 1.69 (0.73) | 1.56 (0.65) |

| Physician global damage (VAS 0–100 mm) | 37 (23) | 31 (25) | 34 (21) |

| Physician global damage (Likert 0–4) | 1.63 (0.96) | 1.40 (1.11) | 1.51 (0.85) |

| ILD present, n (%) | 23 (47) | 14 (28) | 20 (47) |

| Medications use, n (%) | |||

| Rituximab | 6 (10) | 3 (5) | 3 (5) |

| CYC | 4 (7) | 4 (7) | 2 (3) |

| HCQ | 11 (18) | 11 (18) | 17 (28) |

| Immunoglobulins | 13 (21) | 14 (23) | 11 (19) |

| MMF | 17 (28) | 11 (18) | 15 (25) |

| Prednisone | 43 (70) | 39 (64) | 45 (76) |

| Prednisone dose (daily) | 19 (24) | 15 (19) | 15 (18) |

| MTX | 11 (18) | 22 (36) | 11 (19)*** |

| LEF | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 3 (5) |

| AZA | 7 (12) | 3 (5) | 11 (19) |

Values reported are mean (S.d.) if not specified. P-value by t-test or Wilcoxon test for continuous variables, χ2 for categorical variables.

P < 0.05 compared with tertile 3.

P < 0.05 compared with tertile 2.

P < 0.05 by χ2 test. IIM: idiopathic inflammatory myopathies; HDL: high-density liopoprotein; HII: HDL inflammatory index; hs-CRP: high sensitivity CRP; LDL: low-density lipoprotein; CVD: cardiovascular disease; MI, myocardial infarction; CPK: creatine phosphokinase; VAS: visual analogue scale; ILD interstitial lung disease.

Clinical and laboratory characteristics of IIM patients associated with abnormal HDL antioxidant function (expanded disease-specific cohort)

HDL’s antioxidant capacity was evaluated in 182 IIM patients (expanded disease-specific cohort). Population characteristics including age, gender, race and ethnicity, as well as IIM disease activity (physician global VAS and CPK) were similar to IIM patients in the IIM/HC comparison cohort (Table 1) and oxidized fatty acid subgroup (Table 2) (supplementary Table S3, available at Rheumatology online). IIM patients in the expanded disease-specific cohort were divided into three groups by the HII. Tertile 1 contained patients with the highest HII, consistent with severe HDL dysfunction, and tertile 3 contained patients with the lowest HII consistent with the most protective, antioxidant HDL. No significant differences in demographics, traditional cholesterol levels or other comorbidities including cardiovascular risk factors were noted between patients in the different tertiles (Table 3).

The proportion of patients with DM was lowest in patients with the most anti-inflammatory HDL (tertile 3 HII). Patients with the most impaired antioxidant function of HDL (tertile 1 HII) had higher myositis disease activity compared with patients with the most anti-inflammatory HDL (tertile 3 HII), as measured by physician global disease activity scales and CPK levels. Tertile 1 patients also had the longest disease duration, and there was a modest trend for higher global disease damage scores in these patients with poor HDL function.

Association of myositis disease activity and DM diagnosis with abnormal HDL antioxidant function in IIM patients

Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the association of myositis disease activity with HDL’s antioxidant function in IIM patients after controlling for significant correlates of HDL function noted in Table 3 as well as variables previously associated with HDL function (age and statin use). Higher physician global disease activity measured by VAS was significantly associated with HDL with the most impaired antioxidant function (tertile 1 HII) when compared with HDL with the most preserved antioxidant function (tertile 3) after controlling for age, statin use, DM diagnosis, disease duration and MTX use (Table 4). A second multivariate model was performed to assess the relationship of abnormal HDL function with myositis disease activity measured by CPK levels. Higher CPK levels were also significantly associated with impaired antioxidant function of HDL after controlling for the same covariates. The association between abnormal antioxidant function of HDL (higher HII) and higher disease activity by VAS and CPK remained significant in multivariate linear models including all patients in the expanded disease cohort with HII as a continuous variable (supplementary Table S4, available at Rheumatology online).

Table 4.

Multivariate logistic regression models of dysfunctional HDL (tertile 1 vs tertile 3 HII)

| Predictor variable | Model 1 | Model 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 1.009 (0.98, 1.04) | 1.004 (0.98, 1.03) |

| Disease duration, years | 1.03 (0.96, 1.10) | 1.02(0.95, 1.09) |

| DM diagnosis (vs PM) | 3.73 (1.51, 9.78)* | 4.9 (1.7, 15.8)* |

| MTX use | 0.84 (0.30, 2.34) | 0.84 (0.29, 2.39) |

| Statin use | 0.43 (0.11, 1.64) | 0.94 (0.24, 3.78) |

| Physician global disease activity VAS (0–100mm), 10 mm | 10.67 (1.60, 71.22)* | – |

| CPK level, 10 U/l | – | 1.002 (0.999, 1.006)* |

Due to collinearity between VAS and CPK we constructed separate models for each outcome measure. Model 1: Physician global disease activity in VAS, Model 2: CPK. Values presented are unit odds ratios and 95% CIs. P < 0.05. HDL: high-density liopoprotein; HII: HDL inflammatory index; VAS: visual analogue scale; CPK: creatine phosphokinase.

In all models described above, DM diagnosis was significantly associated with impaired antioxidant function of HDL after multivariate adjustment. A diagnosis of DM conferred a 4- to 5-fold risk of abnormal antioxidant function of HDL (tertile 1 HII) compared with a diagnosis of PM in the multivariate logistic model (Table 4).

Association of myositis autoantibodies with HDL function

Of 182 IIM patients, 111 had myositis antibody profiles available for review and HDL function was compared between autoantibody subgroups (Table 5). Patients with no autoantibodies had the lowest HII values, consistent with the most antioxidant HDL. In contrast, patients with anti-melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5 (MDA5) and anti-synthetase antibodies had the highest mean HII values consistent with the worst HDL antioxidant function. The anti-synthetase group had significantly higher mean HII compared with patients with no autoantibodies (P = 0.02), while the MDA5 group had a smaller sample size and did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.09). Other MSA/myositis-associated antibodies group also had significantly higher mean HII compared with patients with no autoantibodies (P = 0.02).

Table 5.

HDL function in IIM by autoantibody subgroups

| Antibody group | N | HII, mean (S.d.) |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-synthetase Ab | 20 | 0.93 (0.81)* |

| MDA5 Ab | 9 | 0.95 (1.02) |

| HMGCR Ab/SRP Ab | 15 | 0.72 (0.66) |

| Unidentified Ab | 10 | 0.71 (0.33) |

| Other MSA/MAA | 47 | 0.70 (0.28)* |

| No autoantibody | 10 | 0.46 (0.23) |

P < 0.05 compared with no autoantibody group by Wilcoxon test. Other MSA (myositis specific antibodies)/MAA (myositis associated antibodies) included Mi2, MJ, SSA, PM-SCL and TIF1 ɣ. HDL: high-density liopoprotein; IIM: idiopathic inflammatory myopathies; HII: HDL inflammatory index; Ab: antibody; MDA5: melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5; HMGCR: 3-Hydroxy-3-Methylglutaryl-Coenzyme A Reductase; SRP: signal recognition particle.

Discussion

IIM are inflammatory diseases of the muscle, which may be associated with severe, multi-organ damage and high morbidity and mortality [15]. CV disease is a major cause of mortality in IIM, with large population based studies demonstrating higher rates of myocardial infarction and severe atherosclerosis compared with the general population [16, 17]. Oxidative stress plays a pivotal role in the development and progression of atherosclerosis, [18] and studies have shown that accumulation of oxidized phospholipids in the vasculature elicits activation of inflammatory signalling pathways [19]. Activation and damage to the small blood vessels in the connective tissue are also implicated in the pathogenesis of IIM itself [4, 20]. However, the mechanisms for ongoing vascular damage in IIM are currently not well understood.

Normal-functioning HDL particles have anti-inflammatory, antioxidant properties that protect the vasculature from endothelial damage caused by oxidative stress [21, 22]. However, during acute and chronic inflammatory states, HDL may become impaired in its protective antioxidant function and promote, rather than prevent vascular inflammation and damage [23–25]. Such non-protective ‘pro-inflammatory’ HDL has been shown to associate with increased atherosclerotic risk in patients with coronary artery disease as well as in other rheumatologic conditions such as RA and SLE [14, 25–27].

In the current work, HDL from IIM patients had impaired capacity to prevent lipid oxidation compared with HC. This difference remained significant after multivariate adjustment for other patient factors, which were different between IIM patients and controls. MPO activity was also higher in DM and PM patients compared with HC, with the highest levels noted in DM patients. Higher plasma activity of MPO associated with worse HDL antioxidant function.

MPO is a peroxidase enzyme that is abundantly expressed in leukocytes such as neutrophils, and generates hypochlorous acid, which is cytotoxic to bacteria, but also causes oxidative damage to host tissues. Previous work has shown that MPO oxidizes HDL’s major protein, apolipoprotein A-1 (apoA-1), generating an HDL particle with impaired antioxidant function [28]. MPO levels have been strongly linked to acute coronary events in the general population [29, 30]; however, no work to date has investigated MPO and HDL’s antioxidant function in IIM. In the current work, higher plasma MPO activity remained significantly associated with impaired antioxidant function of HDL in IIM patients after multivariate adjustment. Further investigation of the relationship between MPO, HDL antioxidant function and microvascular disease in larger IIM cohorts may be warranted.

IIM patients were found to have slightly higher rates of CV risk factors (hypertension, diabetes) and higher total cholesterol and triglycerides when compared with HC. This is consistent with previous work in IIM reporting increased rates of traditional CV risk factors such as obesity, hypertension, diabetes and altered lipid profiles [16, 31–33]. Despite the evidence of increased CV risk factors seen in the IIM population, the precise mechanisms of accelerated vascular damage in IIM patients remain unclear. Measures of HDL function have been suggested as a potential biomarker for identifying those at risk for CV disease and increased vascular damage in other rheumatologic conditions such as RA and SLE [27, 34]. In a study of 276 SLE women, dysfunctional pro-inflammatory HDL was predictive of a 17-fold increase of atherosclerosis, and this association remained significant even after accounting for traditional CV risk factors [34]. It is yet to be determined whether short-term measures of HDL antioxidant function (HII) will predict the risk of longitudinal CV disease in patients with IIM.

Oxidation products of arachidonic acid (HETEs) and its precursor linoleic acid (HODEs) are bioactive lipid mediators produced by enzymes such as MPO under conditions of oxidative stress [35]. In the vascular endothelium, HETEs and HODEs contribute to monocyte and macrophage differentiation as well as to the increased expression of adhesion molecules and release of inflammatory, chemotactic and pro-thrombotic mediators [36, 37]. Previous work has linked these lipid mediators to the development of atherosclerosis [7], and suggests that their accumulation in HDL contributes to HDL dysfunction [6, 38].

In the current study, levels of oxidized fatty acids were significantly higher in HDL from IIM patients compared with HC, particularly in IIM patients with ILD. ILD is a common and severe complication of IIM linked to oxidative stress, with a wide spectrum of clinical presentations ranging from asymptomatic changes on imaging, to rapidly progressive disease leading to respiratory failure within 3–6 months of diagnosis [39]. Evidence of endothelial cell activation and damage has been reported in IIM-ILD, with increased expression of adhesion molecules and higher blood levels of markers of endothelial damage [40, 41]. Higher plasma MPO activity in IIM patients correlated with higher HDL-associated HETEs and HODEs, and 5-HETE in particular, was significantly correlated with impaired antioxidant capacity of HDL. IIM patients with ILD had trends for higher 5-HETE levels in HDL compared with IIM patients without ILD, and higher 5-HETE correlated with more severe lung disease measured by a lower DLCO. Bittleman and Casale previously demonstrated that 5-HETE may play an important role in neutrophil rich lung inflammatory responses such as asthma and alveolitis in pulmonary fibrosis [42]. 12-HETE was also numerically higher in IIM patients, particularly in patients with ILD. 12-HETE is another known pro-inflammatory chemoattractant for neutrophils that was shown to be a key mediator of vascular permeability in acute lung injury mouse models [43–45].

DM diagnosis was associated with worse HDL function compared with PM or IBM diagnosis after multivariate analysis of a cross sectional cohort of 182 IIM patients. Higher IIM disease activity was also associated with impaired HDL antioxidant function after multivariate adjustment. Work by Zheng et al. previously reported that the MPO-induced oxidation of HDL may occur primarily in the artery wall rather than in circulation due to the multiple ‘antioxidant’ pathways in circulation [46]. We hypothesize that the relatively predominant vascular inflammation in DM patients compared with PM patients may predispose them to site-specific oxidation of apoA-1 in the skin and muscle microvasculature, contributing to impaired antioxidant function of HDL.

HDL’s antioxidant function was analysed by autoantibody group, which showed that patients with either MDA5 or anti-synthetase antibody had the highest mean HIIs, consistent with the worst HDL antioxidant function. IIM patients with no autoantibodies had the most antioxidant, protective HDL, which was significantly better in function compared with patients with anti-synthetase antibodies and other MSA. Interestingly, MDA5, the antigen for anti-MDA5 antibody, has been specifically linked to vascular dysfunction causing impaired vasodilation, increased vascular oxidative stress and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines [47]. While these data must be interpreted as pilot in nature, as full multivariate analysis including antibody subgroups was limited by the sample size, we hypothesize that the presence of myositis autoantibodies may be surrogate markers of more severe disease, which associate with impaired HDL function. Further work is ongoing including larger numbers within each MSA subgroup to confirm these findings.

There are limitations to the current work. Our data were from an observational cohort of a single centre. Although the total IIM cohort is large, there was a limited sample size for certain subgroup analyses such as the oxidized fatty acids and MSA subgroups. Further prospective studies in other IIM cohorts with additional patients are needed. It is important to recognize that with limited prior knowledge of HDL function in IIM, univariate and multivariable analyses were meant to be hypothesis generating, and covariate searching was exploratory in nature. Many comparisons were made and significance level was not adjusted for multiple hypothesis testing. Further longitudinal and mechanistic studies are in progress to validate our findings, and determine the consequences of dysfunctional HDL to disease progression including ILD. Immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy (IMNM) has been recently identified as a unique disease entity [48]. In the current work, patients with IMNM were not analysed separately given small numbers. Studies with larger numbers of patients in IMNM and specific MSA subgroups are needed.

In conclusion, this is the first study to characterize HDL’s antioxidant function in a large cohort of patients with IIM. The protective function of HDL in IIM patients was abnormal compared with non-myositis controls, and associated with higher disease activity and DM diagnosis. Higher circulating MPO activity associated with accumulation of oxidized fatty acids in HDL, and worse HDL antioxidant function. Previous studies support the association between altered HDL function and increased oxidative stress leading to CV disease. Identifying a relevant measure of high CV risk and understanding the mechanisms that promote vascular damage may lead to potential risk stratification in IIM. This may be particularly important in patients with active disease despite currently available immunosuppressive therapy. The current data may suggest a mechanism for propagation of accelerated CV disease and microvascular damage seen in IIM through failure of HDL to metabolize pro-inflammatory, oxidized lipids. Further prospective studies are necessary to determine the specific role of impaired antioxidant function of HDL particles in IIM and IIM-associated ILD. Better understanding of disease pathogenesis may lead to development of alternative, targeted therapeutics. Synthetic apoA-1 mimetic peptides bind oxidized fatty acids, attenuate atherosclerosis and lung injury in animal models, and have been shown to improve HDL function in humans [38, 49]. Our results suggest that the use of such therapeutic agents that can reduce vascular damage may warrant further investigation in patients with IIM.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

C.C.-S. received support from the NHLBI (5K23HL094834, R01HL123064), and the Myositis Association. S.T.R. received support from NHLBI (HL-82823 and HL-71776). The current work has been presented as an abstract at the American College of Rheumatology meeting 2018 Chicago [Bae S, Wang J, Shahbazian A et al. Abnormal function of high density lipoproteins in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies (abstract). Arthritis Rheumatol 2018;70(Suppl 10): abstract # 1333].

Funding: No specific funding was received from any funding bodies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors to carry out the work described in this manuscript.

Disclosure statement: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Rheumatology online.

References

- 1. Emslie-Smith AM, Engel AG. Microvascular changes in early and advanced dermatomyositis: a quantitative study. Ann Neurol 1990;27:343–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Marie I, Hachulla E, Hatron PY et al. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis: short term and longterm outcome, and predictive factors of prognosis. J Rheumatol 2001;28:2230–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. De Visser M, Emslie-Smith AM, Engel AG. Early ultrastructural alterations in adult dermatomyositis. Capillary abnormalities precede other structural changes in muscle. J Neurol Sci 1989;94:181–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lundberg I, Kratz AK, Alexanderson H, Patarroyo M. Decreased expression of interleukin-1α, interleukin-1β, and cell adhesion molecules in muscle tissue following corticosteroid treatment in patients with polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheum 2000;43:336–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hahn BH, Grossman J, Ansell BJ, Skaggs BJ, McMahon M. Altered lipoprotein metabolism in chronic inflammatory states: proinflammatory high-density lipoprotein and accelerated atherosclerosis in systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 2008;10:213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Charles-Schoeman C, Meriwether D, Lee YY, Shahbazian A, Reddy ST. High levels of oxidized fatty acids in HDL are associated with impaired HDL function in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol 2018;37:615–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Imaizumi S, Grijalva V, Navab M et al. L-4F differentially alters plasma levels of oxidized fatty acids resulting in more anti-inflammatory HDL in mice. Drug Metab Lett 2010;4:139–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lundberg IE,, Tjärnlund A, Bottai M et al. 2017 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology Classification criteria for adult and juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies and their major subgroups. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017;69:2271–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rider LG, Werth VP, Huber AM et al. Measures of adult and juvenile dermatomyositis, polymyositis, and inclusion body myositis: Physician and Patient/Parent Global Activity, Manual Muscle Testing (MMT), Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ)/Childhood Health Assessment Questionnaire (C-HAQ), Childhood Myositis Assessment Scale (CMAS), Myositis Disease Activity Assessment Tool (MDAAT), Disease Activity Score (DAS), Short Form 36 (SF-36), Child Health Questionnaire (CHQ), physician global damage, Myositis Damage Index (MDI), Quantitative Muscle Testing (QMT), Myositis Functional Index-2 (FI-2), Myositis Activities Profile (MAP), Inclusion Body Myositis Functional Rating Scale (IBMFRS), Cutaneous Dermatomyositis Disease Area and Severity Index (CDASI), Cutaneous Assessment Tool (CAT), Dermatomyositis Skin Severity Index (DSSI), Skindex, and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63:S118–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Travis WD, Costabel U, Hansell DM et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: update of the international multidisciplinary classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013;188:733–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Navab M, Hama SY, Hough GP et al. A cell-free assay for detecting HDL that is dysfunctional in preventing the formation of or inactivating oxidized phospholipids. J Lipid Res 2001;42:1308–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Charles-Schoeman C, Khanna D, Furst DE et al. Effects of high-dose atorvastatin on antiinflammatory properties of high density lipoprotein in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a pilot study. J Rheumatol 2007;34:1459–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Meriwether D, Sulaiman D, Volpe C et al. Apolipoprotein AI mimetics mitigate intestinal inflammation in COX2-dependent inflammatory disease model. J Clin Invest 2019;129:3670–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Charles-Schoeman C, Lee YY, Grijalva V et al. Cholesterol efflux by high density lipoproteins is impaired in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:1157–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kuo CF, See LC, Yu KH, Chou IJ et al. Incidence, cancer risk and mortality of dermatomyositis and polymyositis in Taiwan: a nationwide population study. Br J Dermatol 2011;165:1273–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Diederichsen LP, Diederichsen AC, Simonsen JA et al. Traditional cardiovascular risk factors and coronary artery calcification in adults with polymyositis and dermatomyositis: a Danish multicenter study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2015;67:848–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rai SK, Choi HK, Sayre EC, Avina-Zubieta JA. Risk of myocardial infarction and ischaemic stroke in adults with polymyositis and dermatomyositis: a general population-based study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2016;55:461–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Steinberg D, Parthasarathy S, Carew TE, Khoo JC, Witztum JL. Beyond cholesterol. Modifications of low-density lipoprotein that increase its atherogenicity. N Engl J Med 1989;320:915–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Freigang S. The regulation of inflammation by oxidized phospholipids. Eur J Immunol 2016;46:1818–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Grundtman C, Malmström V, Lundberg IE. Immune mechanisms in the pathogenesis of idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Arthritis Res Ther 2007;9:208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Navab M, Hama SY, Anantharamaiah GM et al. Normal high density lipoprotein inhibits three steps in the formation of mildly oxidized low density lipoprotein: steps 2 and 3. J Lipid Res 2000;41:1495–508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Navab M, Hama SY, Cooke CJ et al. Normal high density lipoprotein inhibits three steps in the formation of mildly oxidized low density lipoprotein: step 1. J Lipid Res 2000;41:1481–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Van Lenten BJ, Hama SY, de Beer FC et al. Anti-inflammatory HDL becomes pro-inflammatory during the acute phase response. Loss of protective effect of HDL against LDL oxidation in aortic wall cell cocultures. J Clin Invest 1995;96:2758–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ansell BJ, Navab M, Hama S et al. Inflammatory/antiinflammatory properties of high-density lipoprotein distinguish patients from control subjects better than high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and are favorably affected by simvastatin treatment. Circulation 2003;108:2751–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Khera AV, Cuchel M, de la Llera-Moya M et al. Cholesterol efflux capacity, high-density lipoprotein function, and atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med 2011;364:127–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Charles-Schoeman C, Watanabe J, Lee YY et al. Abnormal function of high-density lipoprotein is associated with poor disease control and an altered protein cargo in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60:2870–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McMahon M, Grossman J, FitzGerald J et al. Proinflammatory high-density lipoprotein as a biomarker for atherosclerosis in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:2541–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Smith JD. Myeloperoxidase, inflammation, and dysfunctional high-density lipoprotein. J Clin Lipidol 2010;4:382–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Baldus S, Heeschen C, Meinertz T et al. Myeloperoxidase serum levels predict risk in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Circulation 2003;108:1440–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cavusoglu E, Ruwende C, Eng C et al. Usefulness of baseline plasma myeloperoxidase levels as an independent predictor of myocardial infarction at two years in patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome. Am J Cardiol 2007;99:1364–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wang H, Tang J, Chen X, Li F, Luo J. Lipid profiles in untreated patients with dermatomyositis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2013;27:175–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang H, Cai Y, Cai L et al. Altered lipid levels in untreated patients with early polymyositis. PLoS One 2014;9:e89827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. de Moraes MT, de Souza FH, de Barros TB, Shinjo SK. Analysis of metabolic syndrome in adult dermatomyositis with a focus on cardiovascular disease. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013;65:793–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. McMahon M, Grossman J, Skaggs B et al. Dysfunctional proinflammatory high-density lipoproteins confer increased risk of atherosclerosis in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60:2428–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Navab M, Ananthramaiah GM, Reddy ST et al. The oxidation hypothesis of atherogenesis: the role of oxidized phospholipids and HDL. J Lipid Res 2004;45:993–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Vangaveti V, Baune BT, Kennedy RL. Hydroxyoctadecadienoic acids: novel regulators of macrophage differentiation and atherogenesis. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab 2010;1:51–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhao L, Funk CD. Lipoxygenase pathways in atherogenesis. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2004;14:191–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Morgantini C, Natali A, Boldrini B et al. Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties of HDLs are impaired in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2011;60:2617–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fujisawa T, Hozumi H, Kono M et al. Prognostic factors for myositis-associated interstitial lung disease. PLoS One 2014;9:e98824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Barbasso Helmers S, Englund P et al. Sera from anti-Jo-1-positive patients with polymyositis and interstitial lung disease induce expression of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 in human lung endothelial cells. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60:2524–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Funauchi M, Shimadsu H, Tamaki C et al. Role of endothelial damage in the pathogenesis of interstitial pneumonitis in patients with polymyositis and dermatomyositis. J Rheumatol 2006;33:903–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bittleman DB, Casale TB. 5-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (HETE)-induced neutrophil transcellular migration is dependent upon enantiomeric structure. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1995;12:260–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bolick DT, Orr AW, Whetzel A et al. 12/15-lipoxygenase regulates intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression and monocyte adhesion to endothelium through activation of RhoA and nuclear factor-κB. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2005;25:2301–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cunningham FM, Woollard PM. 12(R)-hydroxy-5,8,10,14-eicosatetraenoic acid is a chemoattractant for human polymorphonuclear leucocytes in vitro. Prostaglandins 1987;34:71–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zarbock A, DiStasi MR, Smith E et al. Improved survival and reduced vascular permeability by eliminating or blocking 12/15-lipoxygenase in mouse models of acute lung injury (ALI). J Immunol 2009;183:4715–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zheng L, Nukuna B, Brennan ML et al. Apolipoprotein A-I is a selective target for myeloperoxidase-catalyzed oxidation and functional impairment in subjects with cardiovascular disease. J Clin Invest 2004;114:529–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Asdonk T, Steinmetz M, Krogmann A et al. MDA-5 activation by cytoplasmic double-stranded RNA impairs endothelial function and aggravates atherosclerosis. J Cell Mol Med 2016;20:1696–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mammen AL, Chung T, Christopher-Stine L et al. Autoantibodies against 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase in patients with statin-associated autoimmune myopathy. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:713–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Navab M, Reddy ST, Van Lenten BJ et al. High-density lipoprotein and 4F peptide reduce systemic inflammation by modulating intestinal oxidized lipid metabolism: novel hypotheses and review of literature. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2012;32:2553–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.