Abstract

Objective

To evaluate upadacitinib efficacy and safety dose response in Japanese patients with active RA and an inadequate response to conventional synthetic DMARDs (csDMARDs).

Methods

This was a multicentre, phase IIb/III, dose-ranging study conducted in Japan, in which patients on previously stable csDMARDs were randomized to receive upadacitinib 7.5, 15 or 30 mg once daily or matching placebo for a 12-week double-blind period. The primary endpoint was a 20% improvement in ACR criteria (ACR20) response at week 12 using non-responder imputation. Key secondary endpoints included ACR50, ACR70 and 28-joint DAS with CRP (DAS28-CRP) remission and low disease activity. Adverse events were also assessed.

Results

Of 197 patients treated, 187 completed the double-blind period. At week 12, more patients receiving upadacitinib 7.5, 15 or 30 mg vs placebo met the ACR20 response (75.5%, 83.7%, 80.0% vs 42.9%; P < 0.001), with significant differences observed as early as week 1. Stringent responses, including ACR50, ACR70 and DAS28-CRP <2.6, were achieved by significantly higher proportions of patients on upadacitinib than placebo and by numerically higher proportions on upadacitinib 15 or 30 mg vs upadacitinib 7.5 mg. Adverse events and infections (serious infections, opportunistic infections and herpes zoster) were more common with upadacitinib vs placebo and numerically highest with upadacitinib 30 mg. There were no venous thromboembolic events reported.

Conclusion

Efficacy of upadacitinib was demonstrated in this population of Japanese patients with RA and an inadequate response to csDMARDs. Safety and tolerability were consistent with other upadacitinib RA studies. The 15 mg dose of upadacitinib showed the most favourable benefit–risk profile.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02720523.

Keywords: rheumatoid arthritis, Janus kinase inhibitor, upadacitinib, safety, efficacy, Japanese

Rheumatology key messages

Treatment with upadacitinib was efficacious and acceptably safe in Japanese patients with RA.

Optimal benefit–risk was observed with upadacitinib 15 mg compared with 7.5 mg in patients with RA.

The overall safety and tolerability were consistent with other published studies of upadacitinib in RA.

Introduction

RA is a systemic autoimmune disease characterized by chronic inflammatory synovitis and progressive joint destruction and is associated with severe disability [1, 2]. To prevent irreversible damage associated with progressive disease, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR), Japanese College of Rheumatology [3] and European League against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommend clinical remission or low disease activity (LDA) as the therapeutic target for patients with RA [4, 5]. MTX, a conventional synthetic DMARD (csDMARD), is usually recommended as first-line treatment for RA. However, a significant proportion of patients do not respond adequately to MTX treatment and do not achieve the treatment target at optimal therapeutic doses [3, 4]. In addition, side effects and tolerability of MTX can impact treatment adherence. If the treatment target is not achieved with the first csDMARD and risk factors for progressive disease are present, the addition of biological (b) or targeted synthetic (ts) DMARDs is recommended. Owing to rheumatologists’ extensive experience using bDMARDs in combination with MTX, these combinations are often used first in clinical practice. However, bDMARDs require intravenous or subcutaneous administration, and a significant proportion of patients fail to respond to bDMARDs or lose their primary response [6].

Orally administered inhibitors of the Janus kinase (JAK) family belong to the class of tsDMARDs and have emerged as alternative treatment options for patients with RA. JAKs [JAK1, 2 and 3 and tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2)] are important mediators of multiple cytokine-signalling pathways involved in normal cellular processes as well as in the pathogenesis of RA and other immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Several compounds have been tested in clinical trials and some are approved for the treatment of RA [7–11]. Upadacitinib (ABT-494) is an oral JAK inhibitor engineered for greater selectivity towards JAK1 vs JAK2, JAK3 and TYK2. Upadacitinib is currently in development for the treatment of RA and has demonstrated rapid and sustained clinical and functional efficacy in both global phase II [12, 13] and phase III studies [14, 15].

Here we report the week 12 results of the SELECT-SUNRISE (NCT02720523) study, which evaluated the efficacy and safety of upadacitinib 7.5, 15 and 30 mg once daily (QD) vs placebo for the treatment of Japanese patients with moderately to severely active RA on a stable dose of csDMARDs who have demonstrated an inadequate response (IR) to csDMARDs.

Methods

Study design and settings

SELECT-SUNRISE was a multicentre phase IIb/III dose-ranging study conducted across 49 sites in Japan. The primary objective of this study was to assess the dose response of a 20% improvement in ACR criteria (ACR20) at week 12. The study tested three upadacitinib doses (7.5, 15 and 30 mg QD) vs placebo in patients with moderately to severely active RA who were csDMARD-IR and on a stable dose of csDMARDs. The 7.5 mg dose of upadacitinib, which was not assessed in the global phase III programme, was included in this study to address a request by the Japanese regulatory authority [Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA)] for dose ranging in local Japanese patients. The study duration included a 35 day screening period, a 12 week randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled treatment period and a 30 day follow-up period (for site visit) to confirm dose response in the efficacy of upadacitinib (Supplementary Fig. S1, available at Rheumatology online). Patients who completed week 12 had the option to continue in the study; patients in the upadacitinib groups continued on the same dose of upadacitinib and patients in the placebo group switched to upadacitinib 7.5, 15 or 30 mg QD according to a pre-specified randomized assignment.

The study was conducted according to the International Conference on Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use guidelines, applicable regulations and guidelines governing clinical study conduct and the Declaration of Helsinki. Study-related documents were reviewed and approved by independent ethics committees and institutional review boards. All patients provided written informed consent before participation in the study.

Study population

Eligible patients were ≥18 years of age with a diagnosis of RA for ≥3 months and fulfilled the 2010 ACR and EULAR classification criteria for RA [16]. Eligible patients had ≥6 tender (of 68 assessed) and ≥6 swollen (of 66 assessed) joints at screening and baseline visits and high-sensitivity CRP (hsCRP) ≥3 mg/l measured through a central laboratory at screening. Patients had been receiving csDMARD therapy for ≥3 months and had been on a stable dose of csDMARD therapy (MTX, sulfasalazine, leflunomide, bucillamine or iguratimod) for ≥4 weeks prior to the first dose of study drug. A combination of up to two background csDMARDs was allowed except for the combination of MTX and leflunomide. Patients with prior exposure to at most one bDMARD were allowed to be enrolled (up to 20% of the study population) if they had evidence of intolerance to the bDMARD or limited exposure (<3 months) with required washout periods. Patients were allowed stable concomitant RA medications including NSAIDs, acetaminophen/paracetamol and oral corticosteroids (equivalent to prednisone ≤10 mg/day).

Patients were excluded if they had prior exposure to any JAK inhibitor (including but not limited to tofacitinib, baricitinib and filgotinib) or were considered inadequate responders to bDMARDs. Additional exclusion criteria included serum aspartate transaminase greater than twice the upper limit of normal (ULN), serum alanine transaminase greater than twice the ULN, estimated glomerular filtration rate by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula <40 ml/min/1.73 m2, total white blood cell count <2500/μl, absolute neutrophil count <1500/μl, platelet count <100 000/μl, absolute lymphocyte count <850/μl and haemoglobin <10 g/dl.

Randomization and treatment

Patients were randomized using an interactive response technology with a randomization schedule generated by the Data and Statistical Sciences Department of the study sponsor. Patients, investigators and the sponsor were masked to this allocation. Patients received QD an extended-release formulation of upadacitinib at 7.5, 15 or 30 mg or a matching placebo for 12 weeks along with their background dose of csDMARD(s). The study period began with the baseline visit and ended with the week 12 visit.

Outcomes

The primary efficacy endpoint was the proportion of patients who achieved an ACR20 response at week 12. The ACR20 response rate was based on ≥20% improvement in tender joint count and swollen joint count and three or more of the five remaining measures, including patient’s assessment of pain (visual analogue scale [VAS]), patient’s global assessment of disease activity, physician’s global assessment of disease activity, HAQ–Disability Index (HAQ-DI) and hsCRP.

Key secondary endpoints at week 12 included the proportion of patients achieving ACR50 and ACR70 responses, the proportion of patients achieving a 28-joint DAS using CRP (DAS28-CRP) ≤3.2 and <2.6 and changes from baseline in DAS28-CRP, HAQ-DI, the 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) Physical Component Summary (PCS), Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Fatigue (FACIT-F), Work Instability Scale for RA (RA-WIS) and morning stiffness severity. Additional secondary endpoints at all visits included the proportions of patients achieving ACR20/50/70 responses, DAS28-CRP ≤3.2 and <2.6, LDA and clinical remission by the Simplified Disease Activity Index (SDAI ≤11 and ≤3.3, respectively) and Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI ≤10 and ≤2.8, respectively) and changes from baseline in individual components of the ACR response criteria, DAS28-CRP, morning stiffness severity and duration, SF-36 PCS, FACIT-F and RA-WIS.

Most efficacy variables were measured at weeks 0, 1, 2, 4, 8 and 12. Safety evaluations were conducted during the entire duration of the study and included adverse event (AE) monitoring, physical examinations, vital sign measurements, electrocardiogram and clinical laboratory testing that included haematology, chemistry and urinalysis. Laboratory data were processed at a central laboratory and categorized according to the OMERACT criteria. For creatine phosphokinase (CPK) and serum creatinine, National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria (NCI-CTC) were used. Patients were required to fast for a minimum of 8 h prior to providing blood samples for laboratory analysis. Data for hsCRP were blinded.

Statistical analysis

The sample size estimates were based on a prior study [13]. It was estimated that 48 patients in each group would provide 90% power and a two-sided α of 5% to detect a statistically significant dose response for the primary endpoint, using the Cochran–Armitage test and accounting for a 5% dropout rate.

The primary endpoint analysis was conducted using the full analysis set, defined as all randomized patients who received at least one dose of the study drug. Point estimate and 95% CIs using normal approximation were provided for the response rates for each randomized treatment group. The Cochran–Armitage test was conducted for the dose–response relationship. In addition, the primary endpoint was compared between each upadacitinib dose and the placebo group using the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test, adjusting for prior bDMARD use (yes/no). Non-responder imputation was used for missing data.

For binary secondary endpoints, frequencies and percentages were reported for each randomized treatment group. For the continuous endpoints DAS28-CRP and HAQ-DI change from baseline, statistical inference was conducted using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with multiple imputation (MI) for missing data. The ANCOVA model included treatment as the fixed factor and the corresponding baseline value and the stratification factor prior bDMARD use (yes/no) as covariates. For other continuous endpoints, statistical inference was conducted using mixed-effect model repeated measure (MMRM) with the stratification factor being prior bDMARD use (yes/no). From both the MI and MMRM analyses, the least square (LS) mean and 95% CI were reported for each randomized treatment group. The LS mean treatment differences and associated 95% CIs and P-values were reported comparing each upadacitinib dose group with the placebo group.

An independent external data monitoring committee was used to review unblinded safety data at regular intervals during the conduct of the study.

Results

Demographics and baseline characteristics

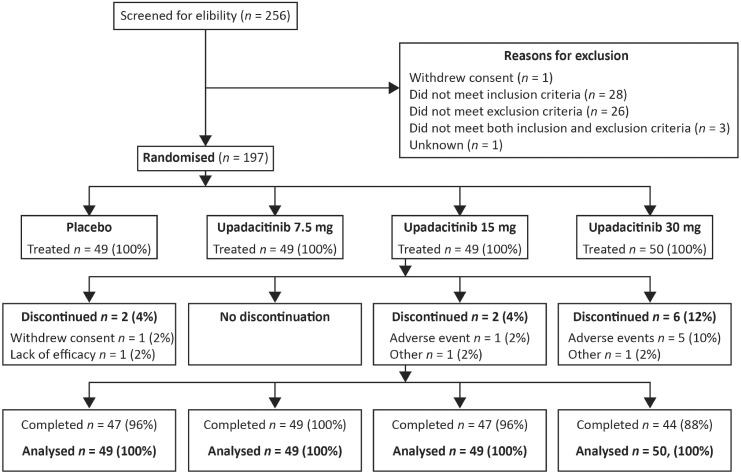

Of 256 Japanese patients who were screened for eligibility, 197 patients were randomized (upadacitinib: 7.5 mg, n = 49; 15 mg, n = 49; 30 mg, n = 50; placebo: n = 49) and received double-blind study treatment, of whom 187 (94.9%) completed 12 weeks on the study drug (Fig. 1). Patients in the upadacitinib 30 mg group had a numerically higher discontinuation rate due to AEs (10%) compared with other treatment groups. No patient discontinued due to a lack of efficacy in any of the upadacitinib treatment groups (one discontinued from the placebo group) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Patient disposition

Baseline characteristics were generally well balanced across treatment groups, although some differences were observed in sex, duration of RA diagnosis and csDMARD use (Table 1). Participants were predominantly female (78.7%) with a mean age of 55.2 years (S.d. 12.1). The mean duration of RA since diagnosis was 5.5 years (S.d. 6.0) and the mean disease activity was high at baseline based on DAS28-CRP [5.1 (S.d. 0.9)] and CDAI [30.5 (S.d. 10.3)].

Table 1.

Demographics and other baseline characteristics

| Parametera | Placebo (n = 49) | Upadacitinib 7.5 mg QD (n = 49) | Upadacitinib 15 mg QD (n = 49) | Upadacitinib 30 mg QD (n = 50) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Age, years | 54.3 (13.0) | 55.8 (11.0) | 56.0 (12.5) | 54.7 (12.2) |

| Female, n (%) | 42 (85.7) | 34 (69.4) | 36 (73.5) | 43 (86.0) |

| Weight, kg | 56.5 (13.7) | 59.2 (10.7) | 58.6 (10.1) | 56.9 (13.0) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 22.8 (4.5) | 23.0 (2.7) | 23.2 (3.4) | 23.1 (5.0) |

| Time since RA diagnosis, years, median (range) | 2.1 (0.4–19.2) | 4.0 (0.4–31.3) | 2.9 (0.4–34.7) | 2.8 (0.3–16.3) |

| RF positive, n (%) | 31 (63.3) | 38 (77.6) | 36 (73.5) | 33 (66.0) |

| Anti-CCP positive, n (%) | 40 (81.6) | 42 (85.7) | 38 (77.6) | 46 (92.0) |

| Prior bDMARD exposure, n (%) | 3 (6.1) | 5 (10.2) | 6 (12.2) | 3 (6.0) |

| csDMARD use at baseline, n (%) | ||||

| MTX alone | 29 (59.2) | 25 (51.0) | 28 (57.1) | 37 (74.0) |

| MTX plus other csDMARD | 14 (28.6) | 13 (26.5) | 12 (24.5) | 7 (14.0) |

| csDMARD other than MTX | 6 (12.2) | 11 (22.4) | 9 (18.4) | 6 (12.0) |

| MTX dose, mg/weekb | 10.1 (2.5) | 10.3 (2.6) | 9.2 (1.9) | 10.0 (2.3) |

| Oral steroid use, n (%) | 24 (49.0) | 26 (53.1) | 28 (57.1) | 24 (48.0) |

| Oral glucocorticoid dose, mg/dayc (prednisone equivalent dose) | 3.8 (2.1) | 3.3 (1.4) | 3.8 (1.9) | 3.6 (1.3) |

| Disease characteristics | ||||

| Tender joint count of 68 joints | 16.8 (11.4) | 16.3 (8.9) | 17.8 (12.6) | 16.3 (10.8) |

| Swollen Joint count of 66 joints | 10.9 (4.7) | 11.7 (4.9) | 14.0 (7.8) | 11.7 (5.3) |

| hsCRP, mg/l, median (range) | 9.6 (1.3–103.0) | 8.3 (1.0–47.5) | 7.8 (0.8–84.6) | 7.0 (1.2–51.1) |

| DAS28-CRP | 5.2 (0.8) | 5.1 (0.8) | 5.1 (1.1) | 5.0 (0.9) |

| CDAI | 31.0 (9.9) | 29.1 (8.1) | 32.1 (12.0) | 29.8 (10.7) |

| SDAI | 32.8 (10.1) | 30.4 (8.3) | 33.7 (12.8) | 31.0 (11.1) |

| HAQ-DI | 1.0 (0.7) | 0.9 (0.7) | 1.0 (0.7) | 0.9 (0.6) |

| FACIT-F | 35.2 (8.1) | 34.6 (9.6) | 33.8 (11.2) | 36.6 (9.2) |

| SF-36 PCS | 39.0 (7.1) | 40.0 (6.7) | 40.5 (7.9) | 42.4 (6.3) |

| RA-WIS | 10.6 (6.3) | 10.6 (6.1) | 9.5 (6.4) | 8.0 (6.0) |

| Morning stiffness severity | 4.6 (2.7) | 4.8 (2.6) | 4.9 (2.9) | 3.8 (2.8) |

| Morning stiffness duration, min, median (range) | 60.0 (0–1440.0) | 60.0 (0–540.0) | 50.0 (0–1440.0) | 30.0 (0–1440.0) |

Data are mean (S.d.) unless stated otherwise.

Mean MTX dose calculated only for patients receiving MTX.

Mean glucocorticoid dose calculated only for patients receiving glucocorticoids. bDMARD: biological DMARD; csDMARD: conventional synthetic DMARD; hsCRP: high-sensitivity CRP; DAS28 (CRP): 28-joint Disease Activity Score using C-reactive protein; CDAI: Clinical Disease Activity Index; SDAI: Simplified Disease Activity Index; HAQ-DI: Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index; FACIT-F: Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy- Fatigue; QD: once daily; SF-36 PCS: Short Form (36-item) Physical Component Summary; RA-WIS: Rheumatoid Arthritis-Work Instability Scale.

Efficacy outcomes

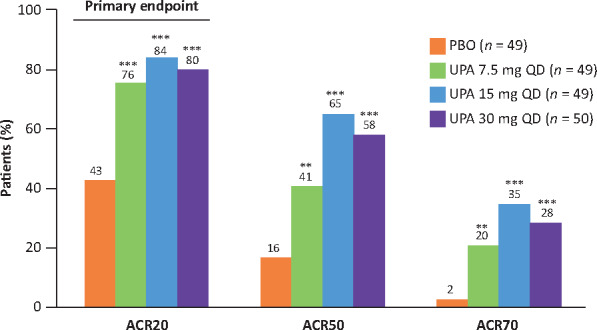

At week 12, 37 of 49 patients (75.5%; 95% CI 63.5, 87.6) in the upadacitinib 7.5 mg group, 41 of 49 patients (83.7%; 95% CI 73.3, 94.0) in the upadacitinib 15 mg group and 40 of 50 patients (80.0%; 95% CI 68.9, 91.1) in the upadacitinib 30 mg group achieved the primary endpoint of ACR20 as compared with 21 of 49 patients (42.9%; 95% CI 29.0, 56.7) in the placebo group (P < 0.001 for each upadacitinib group vs placebo) (Fig. 2). A significant dose response was observed (P < 0.001).

Fig. 2.

ACR20, ACR50 and ACR70 responses at week 12 (NRI)

**P < 0.01, ***P < .001 vs PBO. NRI: non-responder imputation; PBO: placebo; UPA: upadacitinib.

When compared with placebo, significantly more patients treated with upadacitinib achieved ACR20 at week 1 [31% (P = 0.006), 25% (P = 0.026) and 34% (P = 0.002) for upadacitinib 7.5 mg, 15 mg and 30 mg, respectively, vs 8% for placebo] and all subsequent time points. At week 12, patients treated with upadacitinib achieved significantly higher rates of the more stringent measures of ACR50 and ACR70 (Fig. 2). Results for ACR50 and ACR70 were statistically significant for all upadacitinib dose groups compared with placebo. Patients treated with upadacitinib 15 mg and 30 mg had numerically higher ACR50 and ACR70 responses than those treated with 7.5 mg; no incremental efficacy was observed with upadacitinib 30 mg vs 15 mg (Fig. 2).

Through 12 weeks, the mean reduction from baseline in DAS28-CRP was significantly greater in patients who received upadacitinib vs placebo [7.5 mg: −2.1; 15 mg: −2.4; 30 mg: −2.4; placebo: −0.8 (all doses P < 0.001 vs placebo)]. Treatment with upadacitinib over 12 weeks also led to significant improvements in SDAI [mean change from baseline: upadacitinib 7.5 mg: −18.7; 15 mg: −22.4; 30 mg: −22.1; placebo: −9.2 (all doses P < 0.001 vs placebo)] and CDAI [mean change from baseline: upadacitinib 7.5 mg: −17.8; 15 mg: −21.4; 30 mg: −21.4; placebo: −9.1 (all doses P < 0.001 vs placebo)].

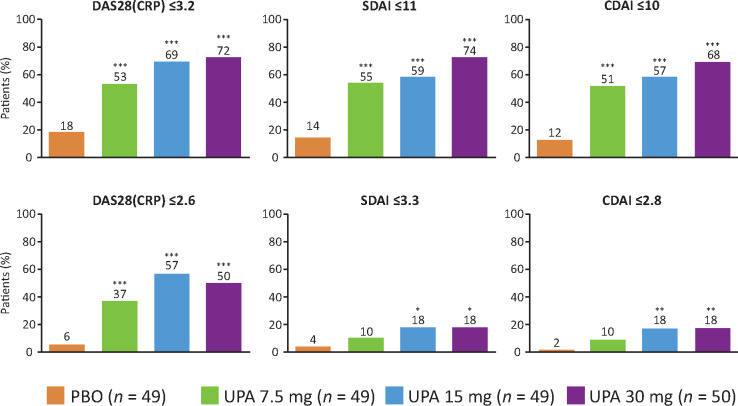

At week 12, upadacitinib treatment led to more patients achieving LDA and remission based on DAS28-CRP (≤3.2 and <2.6), SDAI (≤11 and ≤3.3) and CDAI (≤10 and ≤2.8) vs placebo (Fig. 3). Significant differences between upadacitinib 15 and 30 mg vs placebo were observed across all definitions of LDA and remission. However, for the 7.5 mg dose of upadacitinib, the differences were not significant vs placebo for SDAI and CDAI remission (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Achievement of LDA and remission states at week 12 (NRI)

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < .001 vs PBO. NRI: non-responder imputation; PBO: placebo; UPA: upadacitinib.

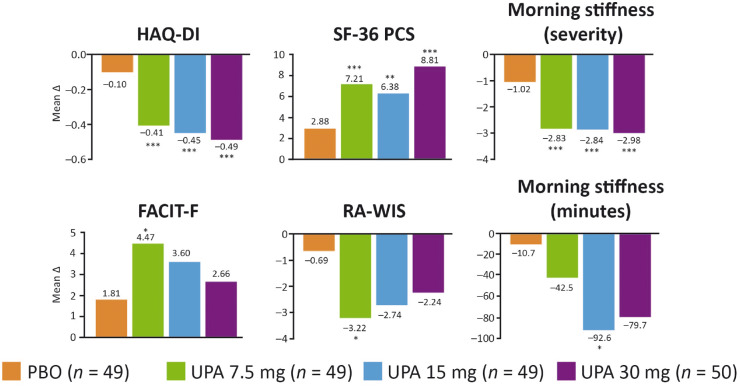

Reductions in HAQ-DI scores from baseline were also significantly greater in the upadacitinib treatment groups, with dose-dependent responses across the three upadacitinib treatment groups [7.5 mg: −0.41; 15 mg: −0.45; 30 mg: −0.49; placebo: −0.10 (P < 0.001)]. In addition to HAQ-DI, all remaining components of the ACR response criteria were reduced significantly through 12 weeks by treatment with upadacitinib vs placebo across doses tested (Supplementary Fig. S2, available at Rheumatology online).

Upadacitinib treatment led to significantly greater reductions in morning stiffness severity across doses compared with placebo (Fig. 4). However, only the 15 mg dose led to a significant reduction in the duration of morning stiffness vs placebo. Numerical improvements with upadacitinib vs placebo were observed in FACIT-F and RA-WIS scores with all upadacitinib doses, but the differences were only significant with the 7.5 mg dose (P < 0.05). There was also a significant improvement in the SF-36 PCS among those treated with upadacitinib [7.5 mg: 7.2; 15 mg: 6.4; 30 mg: 8.8; placebo: 2.9 (P ≤ 0.002)].

Fig. 4.

Change from baseline in patient-reported outcomes at week 12

HAQ-DI results are based on multiple imputation, other endpoints were based on MMRM analysis. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs PBO. PBO: placebo; UPA: upadacitinib.

Safety

AEs were reported in 29 (59%) patients receiving upadacitinib 7.5 mg, 28 (57%) patients receiving 15 mg, 37 (74%) patients receiving 30 mg and 24 (49%) patients receiving placebo. AEs that resulted in discontinuation of the study drug were reported in one (2%) patient on upadacitinib 15 mg, seven (14%) patients on 30 mg and no patients from the 7.5 mg or placebo treatment groups (Table 2). Infections were the most frequent AEs observed across treatment groups, with nasopharyngitis being the most common (data not shown). One serious infection occurred in the upadacitinib 15 mg group (cellulitis) and three occurred in the 30 mg group (hand-foot-and-mouth disease, herpes zoster and Pneumocystis pneumonia); none were reported with upadacitinib 7.5 mg or placebo. Two opportunistic infections occurred in the upadacitinib 30 mg group (oral candidiasis and Pneumocystis pneumonia). There were five events of herpes zoster reported through 12 weeks (one each in the placebo and upadacitinib 7.5 mg groups, none with upadacitinib 15 mg and three with upadacitinib 30 mg), one of which was considered serious in the 30 mg treatment group and led to discontinuation of the study drug. Another patient in the upadacitinib 30 mg group had a non-serious herpes zoster event that led to discontinuation of the study drug. The majority of herpes zoster events were reported as involving only one dermatome. None of the events of herpes zoster were reported as having non-cutaneous involvement. Four drug-related hepatic disorders were reported up to week 12 (two events on placebo and one event each in the 15 and 30 mg groups). Except for one event of hepatic steatosis in the placebo group, all events were reported with alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or aspartate aminotransferase (AST) enzyme elevations. There was one adjudicated cardiovascular event (transient ischaemic attack) reported in the upadacitinib 7.5 mg treatment group in a patient with a medical history of a cerebrovascular accident. There were no reports of death, malignancy, gastrointestinal perforation, renal dysfunction, active/latent tuberculosis, adjudicated major adverse cardiovascular events (defined as cardiovascular death, non-fatal myocardial infarction or non-fatal stroke) or venous thromboembolic events.

Table 2.

Summary of adverse events through 12 weeks

| AEs | Placebo (n = 49) | Upadacitinib 7.5 mg QD (n = 49) | Upadacitinib 15 mg QD (n = 49) | Upadacitinib 30 mg QD (n = 50) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total AEs | 24 (49.0) | 29 (59.2) | 28 (57.1) | 37 (74.0) |

| Serious AEs | 0 | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.0) | 5 (10.0) |

| AEs leading to discontinuation of study drug | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.0) | 7 (14.0) |

| Deaths | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Infections | 11 (22.4) | 18 (36.7) | 16 (32.7) | 22 (44.0) |

| Serious infection | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.0) | 3 (6.0) |

| Opportunistic infection | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (4.0) |

| Herpes zostera | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.0) | 0 | 3 (6.0) |

| Active/latent tuberculosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Malignancy (including NMSC) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hepatic disorder | 2 (4.1) | 0 | 2 (4.1) | 1 (2.0) |

| Gastrointestinal perforation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Adjudicated cardiovascular event | 0 | 1 (2.0) | 0 | 0 |

| Adjudicated MACE | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Other adjudicated cardiovascular event | 0 | 1 (2.0) | 0 | 0 |

| Adjudicated venous thromboembolic event | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

All values presented as n (%).

Including two cases of serious herpes zoster, one in the upadacitinib 7.5 mg group and one in the upadacitinib 30 mg group. AE: adverse event; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular event; NMSC: non-melanoma skin cancer; QD: once daily.

Laboratory measures were assessed at baseline and at each study visit. During the 12 week period, mean levels of haemoglobin remained within normal ranges across treatment groups. At week 12, mean haemoglobin values increased in the upadacitinib 7.5 mg treatment group [3.5 g/l (S.d. 8.6)], whereas there was a small reduction in the 15 mg group [−0.3 g/l (S.d. 7.0)] and a larger reduction in the 30 mg group [−5.4 g/l (S.d. 10.6)]. Grade 3 decreases in haemoglobin were reported from one patient (2%) in the placebo group, five patients (10%) in the upadacitinib 30 mg group and no patients in the 7.5 mg or 15 mg groups; no grade 4 decreases in haemoglobin were reported in any dose group (Supplementary Table S1, available at Rheumatology online). The mean lymphocyte, neutrophil and platelet counts were within normal reference ranges at all visits for all treatment groups. Grade 3 decreases in lymphocyte counts were observed in all treatment groups, including placebo. They were most common in the 30 mg upadacitinib group, with lower frequencies observed with 15 and 7.5 mg (Supplementary Table S1, available at Rheumatology online). Two grade 4 lymphocyte decreases were also observed with upadacitinib 30 mg, with an additional occurrence in the 7.5 mg group. Grade 3 or 4 decreases in neutrophil count were infrequent and there were no grade 3 or 4 decreases in the platelet count.

By week 8, the mean concentration of natural killer (NK) cells increased by 2.8% (S.d. 50.3) with upadacitinib 7.5 mg and 9.3% (S.d. 38.1) with placebo, while it decreased by 3.2% (S.d. 51.9) with upadacitinib 15 mg and by 7.6% (S.d. 57.0) with upadacitinib 30 mg. The decreases in NK cells were generally not associated with viral infections. Up to week 12 there were small increases in the levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) with upadacitinib compared with placebo, which appeared to plateau at week 8. However, the ratio of LDL-C to HDL-C did not change by week 12 (Supplementary Table S2, available at Rheumatology online).

Changes in ALT and AST were observed in some patients. One patient each in the placebo and upadacitinib 15 mg groups experienced grade 3 ALT elevations and one patient experienced grade 3 AST elevation in the placebo group. No patient had an ALT or AST value that was grade 4 and no Hy’s law case was identified. There were three cases of grade 4 CPK elevations reported in the upadacitinib 30 mg group; all three patients were asymptomatic and no patient discontinued the study drug due to blood CPK elevation.

Discussion

The SELECT-SUNRISE study assessed the efficacy and safety profile of three doses of upadacitinib (7.5, 15 and 30 mg) in Japanese patients who had moderately to severely active RA despite a stable dose of csDMARD(s). Through 12 weeks, upadacitinib was effective at reducing the signs and symptoms of RA in patients across all doses examined. More than 75% of patients who received upadacitinib achieved the primary endpoint of an ACR20 response at week 12 with a statistically significant dose–response relationship (P < 0.001). Significant clinical and functional responses were noted as early as week 1 for the upadacitinib treatment groups compared with placebo, which persisted through 12 weeks.

Based on the results of phase IIb trials with upadacitinib in RA, upadacitinib exposures associated with 15 mg QD and 30 mg QD were predicted to provide the optimal balance of benefit–risk in patients with moderately to severely active RA and were therefore selected for further evaluation in the global phase III development programme [17]. While less stringent endpoints such as ACR20 responses are designed to assess effects vs placebo, they may not allow discrimination between several effective doses. While results across the three doses were comparable for ACR20, the 7.5 mg dose (assessed in Japan only) showed numerically lower responses for more stringent endpoints such as ACR50 and ACR70 responses and remission defined by DAS28-CRP, SDAI and CDAI. Of note, the 7.5 mg dose did not significantly increase rates of SDAI and CDAI remission vs placebo, whereas significant increases were observed with the 15 and 30 mg doses. These results are consistent with exposure–response analyses of upadacitinib from the phase IIb trials in patients with RA, which indicated that doses <15 mg QD would provide suboptimal efficacy [17]. However, certain patient-reported outcomes (RA-WIS and FACIT-F) showed a greater improvement with the 7.5 mg dose vs the other upadacitinib doses. The reasons for this are unclear but may be due to variability introduced by both the small sample sizes in each group (particularly for RA-WIS, as this only included the subset of patients who were employed) and the inherent variability in patient-reported measures.

Treat-to-target guidelines recommend a treatment target of remission or LDA in patients with RA, with the aim of preventing structural damage and normalizing health-related quality of life [4]. In this study, at least half of patients treated with upadacitinib 15 or 30 mg and more than one-third of patients treated with upadacitinib 7.5 mg achieved a state of clinical remission based on DAS28-CRP <2.6 after 12 weeks. More stringent definitions of clinical remission based on SDAI ≤3.3 and CDAI ≤2.8 were also achieved by more patients treated with upadacitinib 15 or 30 mg (almost 20% in each group) compared with patients treated with upadacitinib 7.5 mg (10%) after 12 weeks. The alternative treatment target of LDA (as measured by DAS28-CRP, SDAI and CDAI) was also achieved at week 12 in a significant proportion of patients treated with upadacitinib, with numerically higher responses seen with upadacitinib 15 and 30 mg vs the 7.5 mg dose.

The impact of RA on patients has been described in several studies that concluded RA causes major and diverse effects on patients, affecting both physical and mental domains of well-being [18, 19]. A reduction in disease activity results in improvement of patients’ physical function and health-related quality of life [20]. Consistent with improvements in disease activity, patient-reported outcomes including physical function assessment (HAQ-DI), quality-of-life domains (SF-36) and severity of morning stiffness scores significantly improved among patients treated with upadacitinib compared with placebo. Numerical improvements were also observed with upadacitinib in fatigue (FACIT-F) and work instability (RA-WIS).

The safety profile of upadacitinib in this study was generally comparable to other JAK inhibitor studies in this population and similar to global trials of upadacitinib, with some known differences in the safety of JAK inhibition in this Japanese population compared with other geographical regions. The rate of herpes zoster seen in the 30 mg group in this study (6%) appeared to be higher than that observed in the SELECT-NEXT and SELECT-BEYOND studies (1–2%), which did not include Japanese study sites [14, 21]. A similar trend has been observed for Japanese and Korean patients treated with tofacitinib and baricitinib vs other geographical regions [22, 23]. The reason for the increased rate of herpes zoster in Japanese patients is unclear, although it has been suggested that genetic predisposition, regional differences in reporting and cultural or medical factors could be involved [22, 24]. Over 12 weeks, infections were more common in patients treated with upadacitinib vs placebo and followed a dose-dependent trend. The frequency and types of infections observed were consistent with those known for the JAK inhibitor class [25] and were also consistent with those typically seen in the RA population [26].

Most changes in laboratory parameters were mild or moderate and followed a dose-dependent trend; grade 3 and 4 laboratory abnormalities were rare. The types of laboratory changes were consistent with those known in the JAK class, with the exception that no changes in creatinine were observed in this study. The dose-dependent changes in NK cells observed in this study are consistent with inhibition of JAK/signal transducer and activator of transcription signalling with upadacitinib treatment. However, an association between these decreases in NK cells and an increased risk of viral infections could not be established and the clinical relevance of this finding is unclear. Increases in mean levels of LDL-C and HDL-C were also observed with upadacitinib in this study, as reported with other JAK inhibitors [7, 8]. Elevations were generally observed during the first 8 weeks of treatment and remained stable with longer-term treatment. However, the atherosclerotic index remained unchanged at week 12.

Similar to the global upadacitinib studies, certain AEs were higher with upadacitinib 30 mg compared with the other doses, including infections, discontinuation due to AEs and AEs of lymphopenia and of CPK elevation.

This study has several limitations. As this was a dose range trial, the sample size in each treatment group was relatively small, which may have introduced variability into the results and limited the precision of conclusions. This may also have resulted in some imbalances in baseline demographics between the treatment groups, notably in sex, time since RA diagnosis and baseline csDMARD use. It is possible that these differences may have affected the efficacy outcomes in the study; for example, female patients with RA have been shown to have worse fatigue than male patients [27, 28]. However, baseline disease characteristics, including levels of fatigue, were comparable across the treatment groups at baseline, suggesting that differences in demographics did not have a large effect on treatment outcomes.

The geographical diversity of the study population was limited, as the study was conducted with patients in Japan only, precluding generalization of the efficacy and safety results. However, data have already been published on the efficacy and safety of upadacitinib 15 and 30 mg doses from a global population of csDMARD-IR patients with RA and overall conclusions are consistent with those observed in the current study [14]. In addition, this was a relatively short study of only 12 weeks of treatment, but an extension is ongoing to provide longer-term data on the efficacy and safety of upadacitinib in Japanese patients.

Overall, upadacitinib at the 15 mg dose showed the most favourable benefit–risk profile in this csDMARD-IR Japanese population, with comparable efficacy observed with the 15 and 30 mg doses. The 30 mg group had higher rates of AEs and premature discontinuation. Upadacitinib 7.5 mg was less efficacious than 15 mg for the majority of endpoints. Other than the higher incidence of herpes zoster, the safety profile of upadacitinib in this Japanese population was consistent with that observed in global phase III studies. These results suggest that upadacitinib is a favourable treatment option in Japanese patients with RA and an IR to csDMARDs. Further studies are needed to address the role of upadacitinib in Japanese patients who are MTX naïve and those who have an IR to bDMARDs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Statistical support was provided by Masuyuki Yokoyama, of AbbVie, and medical writing support was provided by Dalia Majumdar, of AbbVie, and John Ewbank, of 2 the Nth, which was funded by AbbVie.

Data Sharing

This clinical trial data can be requested by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent scientific research and will be provided following review and approval of a research proposal and statistical analysis plan and execution of a data sharing agreement. Data requests can be submitted at any time and the data will be accessible for 12 months, with possible extensions considered. For more information on the process or to submit a request, visit the following link: https://www.abbvie.com/our-science/clinical-trials/clinical-trials-data-and-information-sharing/data-and-information-sharing-with-qualified-researchers.html.

Funding: This work was supported by AbbVie. AbbVie contributed to the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation and writing, reviewing and approval of final version.

Disclosure statements: H.K. received consulting fees, speaking fees and/or honoraria from AbbVie, Asahi-Kasei Pharma, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Eli Lilly Japan, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Novartis and Pfizer Japan; research grants from AbbVie, Asahi-Kasei Pharma, Astellas Pharma, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Eisai, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma and Novartis. T.T. received grants from AbbVie, Asahi-Kasei Pharma, Astellas Pharma, AYUMI Pharmaceutical, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Nippon Kayaku, Novartis Pharma, Pfizer Japan and Takeda Pharmaceutical and personal fees from AbbVie, Astellas Pharma, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, Eli Lilly Japan, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Nippon Kayaku, Novartis Pharma, Pfizer Japan, Sanofi, Teijin Pharma, Taiho Pharmaceutical, Taisho Pharmaceutical, Takeda Pharmaceutical and UCB Japan. K.Y. participated in speakers bureaus for Pfizer Japan, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Astellas Pharma, AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma. Y.Z., A.O., A.P., S.K. and S.M. are shareholders and employees of AbbVie. Y.T. received speaking fees and/or honoraria from Daiichi Sankyo, Astellas Pharma, Eli Lilly Japan, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Sanofi, AbbVie, Pfizer Japan, YL Biologics, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, UCB Japan, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Novartis, Eisai, Takeda, Janssen Pharmaceutical and Asahi-Kasei Pharma and research grants from Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eisai, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Takeda Pharmaceutical, AbbVie, Astellas Pharma, Daiichi Sankyo, Ono Pharmaceutical, Merck Sharp & Dohme Japan and Taisho-Toyama. The other authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Rheumatology online.

References

- 1. Burmester GR, Kivitz AJ, Kupper H et al. Efficacy and safety of ascending methotrexate dose in combination with adalimumab: the randomised CONCERTO trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:1037–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McInnes IB, Schett G. The pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2011;365:2205–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kameda H, Fujii T, Nakajima A et al. Japan College of Rheumatology guideline for the use of methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Mod Rheumatol 2019;29:31–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Smolen JS, Landewe R, Bijlsma J et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:960–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL Jr et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:1–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nakayamada S, Kubo S, Iwata S, Tanaka Y. Recent progress in JAK inhibitors for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. BioDrugs 2016;30:407–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Burmester GR, Blanco R, Charles-Schoeman C et al. Tofacitinib (CP-690,550) in combination with methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis with an inadequate response to tumour necrosis factor inhibitors: a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet 2013;381:451–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Genovese MC, Kremer J, Zamani O et al. Baricitinib in patients with refractory rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2016;374:1243–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kavanaugh A, Kremer J, Ponce L et al. Filgotinib (GLPG0634/GS-6034), an oral selective JAK1 inhibitor, is effective as monotherapy in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: results from a randomised, dose-finding study (DARWIN 2). Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:1009–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Genovese MC, Greenwald M, Codding C, et al. Peficitinib, a JAK inhibitor, in combination with limited conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in the treatment of moderate-to-severe rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017;69:932–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kivitz AJ, Gutierrez-Urena SR, Poiley J et al. Peficitinib, a JAK inhibitor, in the treatment of moderate-to-severe rheumatoid arthritis in patients with an inadequate response to methotrexate. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017;69:709–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kremer JM, Emery P, Camp HS et al. A phase IIb study of ABT-494, a selective JAK-1 inhibitor, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:2867–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Genovese MC, Smolen JS, Weinblatt ME et al. Efficacy and safety of ABT-494, a selective JAK-1 inhibitor, in a phase IIb study in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to methotrexate. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:2857–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Burmester GR, Kremer JM, Van den Bosch F et al. Safety and efficacy of upadacitinib in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and inadequate response to conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (SELECT-NEXT): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2018;391:2503–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Serhal L, Edwards CJ. Upadacitinib for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2019;15:13–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ et al. 2010 Rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum 2010;69:1580–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mohamed M-E, Winzenborg ID, Noertersheuser E et al. Integrated exposure-response analyses for upadacitinib efficacy and effects on laboratory parameters in rheumatoid arthritis – analyses of phase 2b studies. Arthritis Rheumatol 2018;70 (Suppl 10):abstract 2542. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Matcham F, Scott IC, Rayner L et al. The impact of rheumatoid arthritis on quality-of-life assessed using the SF-36: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2014;44:123–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kojima M, Kojima T, Ishiguro N et al. Psychosocial factors, disease status, and quality of life in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Psychosom Res 2009;67:425–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ishiguro N, Dougados M, Cai Z et al. Relationship between disease activity and patient-reported outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis: post hoc analyses of overall and Japanese results from two phase 3 clinical trials . Mod Rheumatol 2018;28:950–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Genovese MC, Fleischmann R, Combe B et al. Safety and efficacy of upadacitinib in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis refractory to biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (SELECT-BEYOND): a double-blind, randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2018;391:2513–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Winthrop KL, Yamanaka H, Valdez H et al. Herpes zoster and tofacitinib therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014;66:2675–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Harigai M, Takeuchi T, Smolen JS et al. Safety profile of baricitinib in Japanese patients with active rheumatoid arthritis with over 1.6 years median time in treatment: an integrated analysis of Phases 2 and 3 trials. Mod Rheumatol 2020;30:36–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Winthrop KL, Curtis JR, Lindsey S et al. Herpes zoster and tofacitinib: clinical outcomes and the risk of concomitant therapy. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017;69:1960–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Winthrop KL. The emerging safety profile of JAK inhibitors in rheumatic disease. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2017;13:234–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Listing J, Gerhold K, Zink A. The risk of infections associated with rheumatoid arthritis, with its comorbidity and treatment. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013;52:53–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Huyser BA, Parker JC, Thoreson R et al. Predictors of subjective fatigue among individuals with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1998;41:2230–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nikolaus S, Bode C, Taal E, van de Laar MA. Fatigue and factors related to fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013;65:1128–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.