Highlights

-

•

Conspiracy beliefs concerning coronavirus are present in the population and are negatively related to adherence to epidemiological safety guidelines.

-

•

Conspiracy beliefs may originate partially from boredom and paranoia proneness.

-

•

Certain factors – trust in media outlets and internal motivation to isolation – may be potentially worthwhile to address to enhance adherence to safety guidelines in the general population.

Keywords: conspiracy, paranoia, epidemic, compliance, public health

Abstract

Background

Due to coronavirus pandemic, governments have ordered a nationwide isolation. In this situation, we hypothesised that people holding conspiracy beliefs are less willing to adhere to medical guidelines. Furthermore, we explored what possible factors may modify relationships between conspiracy, paranoia-like beliefs, and adherence to epidemiological guidelines. Also, we examined the prevalence of different coronavirus conspiracy beliefs.

Methods

Two independent internet studies. Study 1 used a proportional quota sample that was representative of the population of Poles in terms of gender and settlement size (n=507). Study 2 employed a convenience sample (n=840).

Results

Coronavirus conspiracy beliefs are negatively related to safety guidelines. Mixed results suggest that paranoia-like beliefs are related negatively to safety guidelines. Prevalence of firmly held coronavirus conspiracy beliefs is rare. Nevertheless, certain percentage of participants agree with conspiracy beliefs at least partially. Coronavirus related anxiety, trust in media, and internal motivation to isolation moderate the relationship between conspiracy beliefs and adherence to safety guidelines. Paranoia-like beliefs partially mediate between boredom and conspiracy beliefs.

Conclusions

Conspiracy beliefs concerning coronavirus are present in the population and are negatively related to adherence to safety guidelines. Conspiracy beliefs originate partially from boredom and paranoia proneness. Certain factors – trust in media and internal motivation to isolation – are potentially worthwhile to address to enhance adherence to safety guidelines. Non-probabilistic sampling suggests caution in interpretation of the present findings.

1. Introduction

People in many countries face mandatory self-isolation due to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and risk of developing COVID-19. Quarantine and self-isolation may result in heightened stress and emotional disturbances (Brooks et al., 2020) and an increase of family violence and abuse (Humphreys et al., 2020; van Gelder et al., 2020). Studies have shown that there is a great possibility of a surge of stress and psychological suffering due to COVID-19. People at higher risk of mental problems may respond with the first onset of psychiatric symptoms or relapse (Brown et al., 2020; Kelly, 2020; Pfefferbaum & North, 2020). For instance, the recent case report suggested that the severity of delusions may significantly increase in the context of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in patients with schizophrenia (Fischer, Coogan, Faltraco, & Thome, 2020). However, there is some evidence that perceived stress does not hinder adherence to safety guidelines (Perez, Uddin, Galea, Monto, & Aiello, 2012). At the same time, adherence to self-isolation measures may play a crucial role in slowing down the spread of SARS-CoV-2 (further on: coronavirus) infections, "flattening the curve" (Kenyon, 2020). In this research we explored different psychological factors that may be related to self-isolation and protective behaviours, with a particular focus on conspiracy beliefs and paranoia-like beliefs in a community sample. Furthermore, we explored possible moderators of these relationships. We also wanted to explore what particular specific coronavirus-related conspiracy theories may be the most prevalent during COVID-19 epidemic in Poland.

Adherence to protective and self-isolation measures can be treated as an analogue to treatment compliance. An additional aspect of this analogy is that in an epidemic situation, non-compliance of one person is likely to affect the well-being of another. Numerous factors can affect treatment compliance (Jin, Sklar, Oh, & Li, 2008), e.g., patient characteristics, treatment characteristics, medical care system, nature of the disease, and general social and economic factors. Quarantine adherence was linked to socio-cultural norms and perceived pro-social character of isolation, perceived benefits of quarantine, perceived risk of disease outbreak and trust in government (Webster et al., 2020). We may expect that people with high levels of general interpersonal mistrust (e.g., having exaggerated paranoia-like thoughts) and perceiving epidemiological threat as illusionary, benign or a conspiracy, would be less inclined towards adherence to safety guidelines (Freeman et al., 2020). Recently, all these factors may be operating even more intensively due to the high level of uncertainty and related stress during COVID-19 epidemic.

The relationship between mistrust, paranoia-like thoughts, and adherence to medical or epidemiological recommendations has been described in recent research (Freeman et al., 2020; Marinthe et al., 2020), where paranoia-like and conspiracy beliefs in England and France are associated with lower adherence to safety guidelines. Importantly, believing in conspiracy theories is associated negatively with trust towards science in general (Lewandowsky, Oberauer, & Gignac, 2013). Previous research shows that beliefs in conspiracy theories are relatively widely spread and linked to paranoia-like beliefs (Cichocka, Marchlewska, & Golec de Zavala, 2016; Darwin, Neave, & Holmes, 2011). Moreover, paranoia-like beliefs fully mediated the relationship between boredom proneness and conspiracy beliefs (Brotherton & Eser, 2015). This effect seems important in light of heightened boredom during quarantine and self-isolation (Brooks et al., 2020). A recent report suggests that people with proneness towards paranoia-like beliefs may experience an exacerbation of their symptoms during coronavirus pandemic (Brown et al., 2020; Fischer et al., 2020). It indicates that people with a tendency to paranoia-like beliefs, interpersonal mistrust (including distrust towards governmental messages), science and conspiracy beliefs may potentially be a high-risk group in terms of following safety guidelines.

At the same time, the epidemic may relate to higher risk perception and higher anxiety (i.e. fear of contracting with coronavirus) resulting in its consequence. Higher risk perception is associated with undertaking health behaviours and adherence to quarantine (Brewer et al., 2007; Webster et al., 2020). Previous research from the SARS and H1N1 outbreaks suggest that compliance with safety measures could be affected by risk perception and perceived credibility of information about health measures (Cava, Fay, Beanlands, McCay, & Wignall, 2005; Prati, Pietrantoni, & Zani, 2011). In the context of an epidemic, credibility can also be conceptualised as general trust towards governmental or media outlets regarding safety guidelines. It seems partially contradictory with findings linking paranoia-like beliefs in the general population to the sense of threat and anxiety (Freeman et al., 2005; Freeman et al., 2008; Schutters et al., 2012). Anxiety linked to paranoid beliefs should predispose to greater involvement in safety behaviours (Freeman et al., 2007), which could coincide with epidemiological safety measures (e.g. physical isolation, avoiding public places). However, as discussed above, distrust inherent for paranoia-like and conspiracy beliefs may most probably incline to diminished adherence to safety and self-isolation measures (Freeman et al., 2020), when perceiving guidelines as malign. It could indicate that sense of anxiety and risk particularly associated with coronavirus - and not anxiety in general - could have a modifying effect on the relationship between paranoia-like beliefs and conspiracy beliefs and adherence to self-isolation and safety measures.

There is some recent data on how paranoia-like and conspiracy beliefs in a community sample may be associated with adherence to epidemiological guidelines during an actual epidemic (Freeman et al., 2020; Marinthe et al., 2020). Further research identifying factors associated with adherence is of importance in the context of active social campaigning and targeting misinformation or fake news. In this paper, we present two independent studies of the relation of conspiracy and paranoia like beliefs on adherence to safety guidelines. In both, we analysed the prevalence of different conspiracy theories associated with the current epidemic. We hypothesised that higher levels of paranoia-like and conspiracy beliefs would be related to lower levels of adherence to safety and self-isolation guidelines (Studies 1 and 2). We aimed to provide a comprehensive overview of the mechanisms related to adherence to safety measures due to the COVID-19 outbreak. Hence, in the second study, we also hypothesised that other factors, like the coronavirus related anxiety (Brewer et al., 2007), access to basic resources (financial, food, medical), perceiving self-isolation as internally motivated (Webster et al., 2020), perceived credibility of governmental and media outlets (Cava et al., 2005; Prati et al., 2011), and boredom (Brooks et al., 2020) would be associated with greater adherence to self-isolation measures.

Also, we explored what factors may moderate relationships between conspiracy and paranoia-like beliefs and adherence to safety guidelines. We hypothesised that these relationships would be moderated by the factors mentioned above – the coronavirus related anxiety (Studies 1 and 2), access to resources, internal/external motivation for safety measures, the credibility of government and media outlets and boredom (Study 2). On the other hand, we hypothesised that anxiety unrelated to coronavirus - symptoms of social phobia and agoraphobia - will not moderate these relationships, despite being associated with paranoia-like beliefs (Study 2) (Freeman et al., 2008; Schutters et al., 2012). Finally, in Study 2., we also attempted to replicate the result obtained by Brotherton & Eser (2015), where paranoia-like beliefs fully mediated the relationship of boredom proneness and conspiracy beliefs. In the current study, we hypothesised that the relationship between boredom reported during self-isolation due to pandemic and coronavirus conspiracy beliefs would be mediated by paranoia-like beliefs, indicating the role of paranoia-like beliefs in the occurrence of conspiracy beliefs.

2. Study 1

In this study, we aimed to investigate relationships between self-referential paranoia-like beliefs, conspiracy beliefs and adherence to safety measures in a representative sample of Poles. We also were able to assess the prevalence of specific conspiracy theories regarding coronavirus.

2.1. Study 1. methods

2.1.1. Procedure and the socio-legal context

The study was conducted between 11th and 14th April 2020. The whole Poland was in a state of emergency for a month now, with various special laws established to control the spread of the coronavirus. The whole education system, from primary to university level, was conducting online classes. Businesses and organizations, such as shopping malls (except groceries and pharmaceuticals), restaurants (except takeaways), bars, hotels, museums, concert halls, cinemas, theatres, libraries, gyms, hairdressers and other, were prohibited from operating. Religious services (including burials) were operating with a restricted amount of participants. Local government bureaus were working in a limited capacity. The number of people using operating businesses was restricted. Operating businesses were obliged to provide their services to only senior citizens between 10 and 12 AM. People ought to keep at least 2m distance on the streets (this also concerned people from the same household). There was a ban on using public parks and forests. Children up to the age of 13 were prohibited from going outside without their legal guardian. All people were required to cover their mouths and nose in public. Violation of these restrictions was met with fines administered by the police or the sanitary-epidemiological stations on the police's motion for violation of these rules (fines as high as 30000PLN, roughly 6500EUR).

Study 1 involved a nationwide proportional quota sample collected online by Pollster Institute - one of the leading Polish online research platforms. The sample consisted of 507 individuals and was representative of the population of adult Poles in terms of gender and settlement size. At the same time, respondents were slightly older than the general population. Participants were asked to complete the scales that measured: anxiety related to coronavirus, adherence to safety and self-isolation, conspiracy beliefs related to coronavirus epidemic, and R-GPTS Reference subscale.

2.1.2. Measures

Coronavirus related anxiety - measure consisting of 3 items assessed on a scale from 1 to 7 related to the anxiety of 1) contracting with coronavirus, 2) family member contracting with coronavirus, 3) worsening of the financial situation due to coronavirus. Higher scores indicate greater levels of anxiety associated with coronavirus. This measure had a satisfactory internal consistency of Cronbach's α = 0.81.

Adherence to safety and self-isolation measures - 4 items assessed on a scale 1 to 7 related to official WHO recommendations (World Health Organization 2020). The higher score indicates a higher degree of declared compliance with safety-measures. This measure had a satisfactory internal consistency of α = 0.80.

Conspiracy beliefs - measure consisting of 14 items with various conspiracy beliefs regarding coronavirus epidemic. Table 1 . lists specific items. All items were summed into a general index of coronavirus conspiracy beliefs endorsement (Wood, Douglas, & Sutton, 2012). This scale had an excellent internal consistency of α = 0.93.

Table 1.

Prevalence of conspiracy beliefs in Studies 1 and 2.

| Conspiracy theory | Strongly disagreeing (1 on Likert scale) | Disagreeing (3 or less on Likert scale) | Agreeing (5 or more on Likert scale) | Strongly agreeing (7 on Likert scale) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conspiracy theories in Study 1. | |||||

| The Polish government is intentionally hiding the real number of people contracted with coronavirus. | 17.6% | 34.7% | 46.2% | 19.5% | |

| The Polish government is manipulating information regarding coronavirus to broaden their sphere of influence. | 17% | 34.1% | 46.7% | 20.1% | |

| Coronavirus was created by ecologists to reduce population and help the environment | 47.9% | 71.8% | 9.3% | 2.2% | |

| Coronavirus is a way for the climate movement to fulfil their plans | 45.4% | 71% | 9.1% | 2.8% | |

| Coronavirus was created by pharmaceutical organizations | 40.8% | 65.5% | 13.4% | 3.7% | |

| Medicine intended for people with coronavirus actually make them sicker | 41% | 68.8% | 8.1% | 2.6% | |

| Coronavirus is injected through vaccines | 61.3% | 83.2% | 3.9% | 1.2% | |

| Medical doctors want to spread coronavirus | 62.7% | 83.4% | 4.7% | 1% | |

| Coronavirus was created by the USA government to aid their position in the economic war with China | 42.6% | 69.4% | 9.9% | 3.4% | |

| Coronavirus was created by the USA government to take control of the world economy | 43.6% | 71% | 10.7% | 2.6% | |

| Coronavirus was created by the Chinese to take control of the world economy | 33.1% | 55.4% | 22.5% | 6.9% | |

| Coronavirus was intentionally spread by the Chinese in restaurants | 40.8% | 66.7% | 12.6% | 4.3% | |

| Coronavirus was created to get rid of old people | 38.9% | 61.7% | 20.1% | 5.3% | |

| Coronavirus was created to eliminate the weakest | 34.3% | 58.4% | 22.1% | 5.9% | |

| Conspiracy theories in Study 2. | |||||

| Coronavirus was created by one of the governments as a biological weapon. | 32.5% | 56.5% | 19.5% | 4.4% | |

| True information about coronavirus is concealed by governments and public organizations. | 13.9% | 36.7% | 45.4% | 11.1% | |

| Coronavirus was created by pharmaceutical companies. | 44.5% | 70.4% | 9.9% | 2.0% | |

| Effective treatment for coronavirus is concealed by governments or pharmaceutical companies. | 44.9% | 74.3% | 10.5% | 3.5% | |

| Coronavirus epidemic is a way to control people behaviour. | 37.0% | 62.1% | 23.8% | 6.8% | |

| Coronavirus epidemic is a medical experiment carried out on the public without consent. | 48.9% | 74.4% | 9.4% | 2.6% | |

| Decisions regarding coronavirus are made by a small unknown group of decision-makers. | 47.7% | 72.7% | 11.7% | 2.5% | |

| Governments are intentionally allowing the virus to spread on their territories. | 50.7% | 80.6% | 6.9% | 1.8% | |

| Coronavirus epidemic was planned as a way to distract people from some other event. | 46.3% | 71.1% | 12.1% | 3.6% | |

| Coronavirus was created to eliminate the weakest members of society. | 46.7% | 71.8% | 13.9% | 3.3% | |

| Coronavirus was created to take the size of the human population under control. | 47.1% | 70.7% | 13.9% | 3.3% | |

| Coronavirus was created to stop global warming and climate change. | 56.1% | 80.4% | 5.1% | 1% | |

Green Paranoid Thoughts Scale-Revised (R-GPTS) - is a comprehensive questionnaire of paranoia-like beliefs to be used in clinical and general population settings (Freeman et al., 2019). This study employed only the Reference subscale, consisting of 8 items, and with excellent internal consistency, α = 0.91.

2.1.3. Statistical analyses

Data were analysed with IBM SPSS 26. Spearman's Spearman's ρ ranked correlation was used to account for non-normality in the data distribution. Correlation matrices were subjected to a Bonferroni correction to account for the number of similar significance tests. Moderation analyses were performed with PROCESS v3.5 macro was used for moderation analyses. Predictive variables in these analyses were centred. "High" and "low" values in simple slopes analyses indicate ±1 sd of a moderator variable.

2.2. Study 1. results

Five hundred seven participants completed the study. Mean age was 44.07 (±14.41). There were 253 (49,9%) women in the sample. 10.8% of participants had basic or vocational education, 41.2% had secondary education, and 47.9% had higher education. 35.9% participant lived in the country, 32.1% in a town below 100k inhabitants, 19.3% in a small city between 100k and 500k inhabitants and 12.6% in a large city above 500k inhabitants. Mean score of adherence to WHO guidelines was 23.99 (±4.23). Regarding support for conspiracy theories, 32.1% declared full agreement with at least one conspiracy theory concerning coronavirus (13% when government conspiracy is excluded). Prevalence of belief in different conspiracy theories is presented in detail in Table 1. Table 2 . shows detailed relations of different aspects of safety measures and coronavirus anxiety, conspiracy beliefs and GTPS-R Reference. Coronavirus related anxiety was not significantly correlated with conspiracy beliefs and R-GPTS Reference. Conspiracy beliefs and R-GPTS Reference were significantly correlated at ρ = 0.24, p < 0.001.

Table 2.

Detailed correlation coefficients from Study 1.

| Mean score (sd) | WHO epidemic guidelines |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| “I try not to leave my house unless it's absolutely necessary” | “Because of the epidemic I wash my hands more often and longer than usual” | “I limit contact with my relatives and friends to avoid coronavirus contraction” | “When outside the home I try to keep several meter distance from others” | Total score | ||

| Coronavirus related anxiety | 15.97 (4.16) | 0.36** | 0.42** | 0.31** | 0.31** | 0.42** |

| Conspiracy beliefs | 38.10 (17.32) | -0.20** | -0.14 | -0.19** | -0.22** | -0.22** |

| GPTS-R Reference | 8.77 (7.36) | -0.15* | - | -0.15* | -0.20** | -0.17* |

If not stated otherwise, values in cells are Spearman's ρ correlation coefficient. GPTS-R Reference – Reference subscale of Green Paranoid Thoughts Scale. Not significant relations are not presented for clarity. No symbol - p ≤ 0.05, * - p ≤ 0.01, ** - p ≤ 0.001. p values in this table are corrected for the number of tests with Bonferroni correction (15 tests in total).

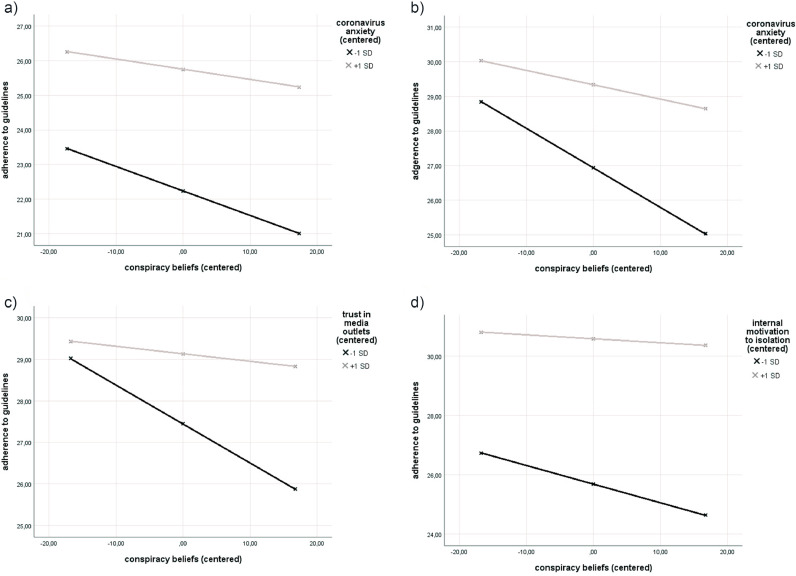

Moderation analysis revealed that there was a significant interaction between conspiracy beliefs and coronavirus related anxiety in predicting adherence to safety guidelines. For details of the model, see Table 4. and Fig. 1 a. There was no moderation effect for R-GPTS Reference scale.

Table 4.

Regression, moderation and simple slopes analyses for Studies 1 and 2.

| Study 1. Regression and moderation analysis for conspiracy and paranoia-like beliefs predicting adherence to safety guidelines |

Study 2. Regression and moderation analysis for conspiracy beliefs and coronavirus related anxiety predicting adherence to safety guidelines |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE b | t | p | b | SE b | t | p | ||

| Constant | 23.99 | 0.16 | 144.18 | <0.001 | Constant | 28.14 | 0.24 | 118.97 | <0.0001 |

| GPTS-R Reference | -0.05 | 0.02 | -2.085 | 0.038 | Conspiracy beliefs | -0.08 | 0.01 | -5.47 | <0.0001 |

| Conspiracy beliefs | -0.05 | 0.01 | -4.622 | <0.001 | Coronavirus related anxiety | 0.19 | 0.04 | 5.03 | <0.0001 |

| Coronavirus related anxiety | 0.43 | 0.04 | 10.544 | <0.001 | |||||

| GPTS-R Reference x Coronavirus related anxiety | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.023 | 0.98 | Conspiracy beliefs x Coronavirus related anxiety | 0.006 | 0.002 | 2.76 | 0.006 |

| Conspiracy beliefs x Coronavirus related anxiety | 0.01 | 0.002 | 2.142 | 0.033 | |||||

| Note: F(5,501) = 29.64, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.23 | Note: F(3,836) = 22.33, p < 0.0001, R2 = 0.07 | ||||||||

| Study 1. Simple slopes values for coronavirus related anxiety predicting conspiracy beliefs |

Study 2. Simple slopes values for coronavirus related anxiety predicting conspiracy beliefs |

||||||||

| Coronavirus related anxiety -1sd | -0.07 | 0.01 | -5.33 | <0.0001 | Coronavirus related anxiety -1sd | -0.11 | 0.02 | -6.02 | <0.0001 |

| Coronavirus related anxiety +1sd | -0.03 | 0.01 | -2.32 | 0.021 | Coronavirus related anxiety +1sd | -0.04 | 0.02 | -2.10 | 0.04 |

| Study 2. Regression and moderation analysis for conspiracy beliefs and trust in media outlets predicting adherence to safety guidelines |

Study 2. Regression and moderation analysis for conspiracy beliefs and internal motivation to isolation predicting adherence to safety guidelines |

||||||||

| b | SE b | t | p | b | SE b | t | p | ||

| Constant | 28.29 | 0.24 | 116.33 | <0.0001 | Constant | 28.25 | 0.23 | 123.72 | <0.0001 |

| Conspiracy beliefs | -0.06 | 0.01 | -3.73 | 0.0002 | Conspiracy beliefs | -0.04 | 0.01 | -2.61 | 0.009 |

| trust in media outlets | 0.57 | 0.17 | 3.42 | 0.0007 | internal motivation to isolation | 1.50 | 0.14 | 10.99 | <0.0001 |

| Conspiracy beliefs x trust in media outlets | 0.026 | 0.01 | 2.90 | 0.004 | Conspiracy beliefs x internal motivation to isolation | 0.015 | 0.007 | 2.16 | 0.031 |

| Note: F(3,836) = 17.10, p < 0.0001, R2 = 0.06 | Note: F(3,836) = 57.02, p < 0.0001, R2 = 0.17 | ||||||||

| Study 2. Simple slopes values for trust in media outlets predicting conspiracy beliefs |

Study 2. Simple slopes values for internal motivation to isolation predicting conspiracy beliefs |

||||||||

| Trust in media outlets -1sd | -0.09 | 0.02 | -5.36 | <0.0001 | Internal motivation to isolation -1sd | -0.06 | 0.02 | -3.74 | 0.0002 |

| Trust in media outlets +1sd | -0.02 | 0.02 | -0.81 | 0.42 | Internal motivation to isolation +1sd | -0.01 | 0.02 | -0.68 | 0.50 |

Fig. 1.

Simple slopes from moderation analyses. Fig. 1a) coronavirus anxiety the relationship between adherence to WHO guidelines and coronavirus conspiracy beliefs in Study 1. Fig. 1b, c and d) moderation analyses with significant results in Study 2.

3. Study 2

In this study, we aimed to investigate relationships between paranoia-like beliefs, conspiracy beliefs and adherence to safety measures. At the same time, we also considered other associated variables - trust in media and government outlets, boredom, the anxiety of coronavirus contagion, access to resources, internal and external motivation to staying at home/isolating and psychopathology in a community convenient sample. We also were able to assess the prevalence of certain selected conspiracy theories regarding coronavirus.

3.1. Study 2. methods

3.1.1. Procedure and the socio-legal context

The study was conducted between 21st and 28h April 2020. The socio-legal context was the same as in study 1., with one exception – ban on using public parks and forests was lifted the day before the study. The study was conducted online, using LimeSurvey software. Participants were gathered via social media advertisements and asked to take part in the study and share it with their friends. So a mixture of convenient and snowball sampling was used. Participation in the study was voluntary, and participants gave their informed consent. The study obtained a positive opinion from the Research Ethics Committee at the Institute of Psychology, Polish Academy of Science.

3.1.2. Measures

Coronavirus related anxiety - measure consisting of 5 items assessed on a scale from 1 to 7 related to the anxiety of 1) contracting with coronavirus, 2) family member contracting with coronavirus, 3) contracting other people with coronavirus, 4) someone contracting you with coronavirus, 5) worsening of the financial situation due to coronavirus. Higher scores indicate greater levels of anxiety associated with coronavirus. This measure had a satisfactory internal consistency of Cronbach's α = 0.81.

Adherence to safety and self-isolation measures - 5 items assessed on a scale 1 to 7 related to official Polish government recommendations, Table 4 lists all the items. The greater score indicates a higher degree of declared compliance with safety-measures. This measure had a satisfactory internal consistency of α = 0.87.

Perceived access to resources - measure consisting of 5 items assessed on a scale from 1 to 7, based on results by Brooks et al., (2020), related to perceived access to financial resources, food, medical/safety supplies (antibacterial liquids, masks, gloves), pharmaceuticals and medical care. Higher results indicate greater perceived access to resources. This measure had an acceptable internal consistency of α = 0.74.

Trust in media and government outlets, boredom, internal and external motivation for self-isolation. One item each, asking for an assessment of trust in of media and government (Ministry of Health, National Health Inspectorate) messages related to coronavirus pandemic, level of boredom, and statements: "I perceive recommendations to isolate as externally imposed, e.g. because of the threat of being fined" and "I perceive recommendations to isolate as internally motivated, e.g. to protect my and/or others health". These were assessed on a 1 to 7 Likert scale.

Green Paranoid Thoughts Scale-Revised (R-GPTS) - This measure was translated into Polish for this study. JK has done the first translation, and then it was modified by ŁG; any incompatibilities were resolved by discussion. It contains two subscales - Reference (8 items, excellent α of 0.90) and Persecutory (10 items, excellent α of 0.93) beliefs.

Symptoms Checklist-27-plus (SCL-27-plus) - is a comprehensive screening measure of different types of emotional disorders symptoms, and pain (Hardt, 2008; Kuncewicz, Dragan, & Hardt, 2014). It consists of five subscales for measuring pain, depressive, agoraphobic, sociophobic and vegetative symptoms. The whole questionnaire had an excellent α of 0.93. All subscales had satisfactory internal consistency ranging from α = 0.77 (pain subscale) to α = 0.93 (depressive symptoms subscale).

Conspiracy beliefs - measure consisting of 12 items with various conspiracy beliefs regarding coronavirus epidemic. Table 1. lists specific items. Some of the items were generated based on the generic set of conspiracy beliefs (Brotherton, French, & Pickering, 2013). All items were summed into a general index of coronavirus conspiracy beliefs endorsement (Wood et al., 2012) . This scale had an excellent internal consistency of α = 0.96.

Data were analysed in the same way as in Study 1.

3.2. Study 2. results

Eight hundred forty participants completed the study. Mean The mean age was 29.94 (±10.39). There were 607 (72.3%) women in the sample, and 8 (1%) participants declared other gender than male/female or did not want to disclose one. 4.6% of participants had basic primary or vocational education, 36.4% had secondary education, and 58.9% had higher education. 16.1% participant lived in the country, 27.5% in a town below 100k inhabitants, 21.8% in a small city between 100k and 500k inhabitants and 34.6% in a large city above 500k inhabitants. Mean score of adherence to protective guidelines was 28.15 (±7.11). Mean scores for SCL-27-plus subscales was: pain 5.99 (±4.45), vegetative 3.94 (±4.12), sociophobic 5.00 (±5.31), agoraphobic 2.76 (±3.85) and depressive 7.25 (±6.26) symptoms. Table 3 . presents mean values of other variables. Almost one in five participants (17%) declared full support for at least one conspiracy theory concerning coronavirus. Table 1. lists different conspiracy theories and their prevalence.

Table 3.

Detailed correlation coefficients from Study 2.

| Official governmental guidelines, “To avoid coronavirus contraction...”

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean score (sd) | “...I try not to leave my house unless it's absolutely necessary” | “...I wash my hands more often and longer than usual” | “...I limit direct contact with my relatives and friends” | “... I try to keep at least 1.5m distance from others when in public” | “...I wear a mask and/or gloves when in public” | Total score | ||

| Coronavirus related anxiety | 23.29 (6.36) | 0.19** | 0.18** | 0.15** | 0.24** | 0.20** | 0.30** | |

| Conspiracy beliefs | 30.78 (16.75) | -0.14* | -0.13 | -0.17** | -0.12 | -0.15** | -0.20** | |

| GPTS-R | Reference | 6.45 (7.45) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Persecution | 4.54 (7.93) | - | - | -0.12 | - | - | - | |

| Perceived resources | 26.85 (5.47) | - | 0.13* | 0.14* | - | 0.16** | 0.15** | |

| Motivation for adherence | Internal | 5.45 (1.71) | 0.43** | 0.22* | 0.37** | 0.32** | 0.32** | 0.44** |

| External | 3.99 (2.08) | -0.12 | - | -0.16* | - | - | -0.16** | |

| Trust in outlets | Governmental | 4.46 (1.70) | 0.20** | 0.16** | 0.18** | 0.18** | 0.22** | 0.25** |

| The media | 3.80 (1.48) | 0.13 | - | 0.13* | - | 0.14* | 0.15* | |

| Boredom | 3.80 (2.07) | - | - | -0.17** | -0.13 | - | - | |

If not stated otherwise, values in cells are Spearman's ρ correlation coefficient. GPTS-R Reference – Reference subscale of Green Paranoid Thoughts Scale. SCL-27-plus – Symptoms Checklist 27 plus. Not significant relations are not presented for clarity. No symbol - p ≤ 0.05, * - p ≤ 0.01, ** - p ≤ 0.001, p values in this table are corrected for the number of tests with Bonferroni correction (90 tests in total).

Detailed relations of safety measures and other variables are shown in Table 3. Coronavirus anxiety significantly correlated with R-GPTS Reference and Persecution (both at ρ = 0.13, p < 0.003) but not with conspiracy beliefs. Conspiracy beliefs and R-GPTS Reference (ρ = 0.23, p < 0.001) and Persecution (ρ = 0.26, p < 0.001) were significantly correlated. Conspiracy beliefs were positively correlated with SCL-27-plus subscales (ρ = 0.12 - 0.21, all p's ≤ 0.001). R-GPTS Reference (ρ = 0.26 - 0.57, all p's < 0.001) and Persecution (ρ = 0.25 - 0.52, all p's < 0.001) were significantly correlated with SCL-27-plus subscales. In all these analyses, the weakest correlation was with the pain subscale and the strongest with the sociophobic symptoms subscale.

Series of moderation analyses showed that coronavirus related anxiety, an internal motivation to isolation and trust in media outlets moderated the relationship between adherence to safety guidelines and coronavirus conspiracy beliefs. At the same time, perceived resources, external motivation to isolation, boredom and trust in government outlets did not. Moreover, in line with our hypotheses, sociophobic and agoraphobic symptoms were not moderators of the relationship between conspiracy beliefs and adherence to guidelines. Details of these analyses are presented in Table 4 . Fig. 1. presents simple slope graphs.

Series of moderation analyses with adherence to governmental guidelines as predicted variable and R-GPTS Reference or Persecutory scales as main predictors showed that none of the considered factors was a moderator of these relationships. Again, in line with hypotheses, sociophobic and agoraphobic symptoms were not moderators of the relationship between Persecutory and Reference beliefs and adherence to guidelines.

Furthermore, we performed an analysis of mediation to investigate indirect effect of boredom on conspiracy beliefs through paranoia-like beliefs. Boredom predicted conspiracy beliefs b = 1.79, t = 6.58, p < 0.001, R 2 = 0.05. Boredom also predicted R-GPTS total score b = 1.84, t = 8.01, p < 0.001, R 2 = 0.07. In the mediation model, the relationship between boredom and conspiracy beliefs was reduced (b = 1.28, t = 4.67, p < 0.001), while paranoia-like beliefs was a significant predictor (b = 0.27, t = 6.92, p < 0.001) implying a significance of indirect effect. Overall, the model was significant and explained a modest amount of variance; F(2, 837) = 46.83, p < 0.001, R 2 = 0.10. The indirect effect of boredom on conspiracy beliefs through R-GPTS total score accounted for 28% of the total effect of boredom on conspiracy beliefs, indicating partial mediation.

4. Discussion

In these two independent studies, we aimed at exploring relationships of conspiracy and paranoia-like beliefs and adherence to safety measures during coronavirus pandemic. Such research seems essential on the basis of a surge of anti-scientific and conspiracy stances not only in polish media and politics (Dobosz & Zawiła-Niedźwiecki, 2016) but also worldwide and in the context of current coronavirus pandemic (Smith, 2020). Prior studies have explored various factors impacting adherence to self-isolation guidelines (Webster et al., 2020). Recent studies have found that conspiracy beliefs, paranoia-like beliefs, which are prevalent in the general population, may also be related to adherence to epidemiological guidelines (Freeman et al., 2020; Marinthe et al., 2020). We designed our studies to explore further these relationships. In addition to previous results we also explored factors moderating these hypothesised relations.

Prevalence of some conspiracy beliefs was relatively low to moderate (5-23%) in both independent studies, with most beliefs at around 10%, of participants rather agreeing with most of them. Strong agreement with proposed conspiracy beliefs is rather rare, with 1-7% of participants endorsing most of these beliefs. There are, however, some exceptions. In both studies, conspiracy beliefs about governments, particularly the Polish government, manipulating information had around 46% of participants rather agreeing with them, and in some cases 20% of strongly agreeing. Those theories mostly reflect beliefs about government manipulating information for their gain or enhancement of their political influence. It may be a reflection of a lack of trust put in the Polish government in comparison to other countries (Smith, 2020). On the other hand, conspiracy beliefs about government's malicious actions like intentionally spreading the virus or facilitating depopulation are somewhat less popular.

In both studies, in line with our expectations, we uncovered a small but consistent pattern of negative relationships between conspiracy beliefs and all aspects of adherence to safety guidelines and general adherence to them. It is consistent with previous findings showing relationships of conspiracy beliefs and distrust towards science (Lewandowsky et al., 2013) and results showing the relationship of conspiracy beliefs about coronavirus with lower adherence to safety guidelines (Freeman et al., 2020; Marinthe et al., 2020). A higher degree of conspiracy beliefs about coronavirus pandemic may likely predispose to lesser motivation to adhere to official guidelines. Internal motivation to isolation moderating the relationship between adherence to guidelines and conspiracy beliefs support this conclusion. On the other hand, given the cross-sectional nature of obtained data, it may be possible that people with lower abilities or resources to adhere to safety measures will be more prone to endorse conspiracy beliefs as a result of cognitive dissonance reduction or need for cognitive closure (Kossowska & Bukowski, 2015; Marchlewska, Cichocka, & Kossowska, 2018). Future research would do well to explore this issue. In our study, perceived access to resources was positively associated with adherence to guidelines but did not moderate the relationship between conspiracy beliefs and adherence to guidelines.

Interestingly, we also found a moderating effect of coronavirus related anxiety on the relationship between conspiracy theories and adherence to safety measures. It may point to risk perception associated with coronavirus (i.e. fear of contracting coronavirus) as a factor positively impacting adherence to safety guidelines (Brewer et al., 2007). It suggests that activating anxiety related to COVID-19 may be a potential strategy of entailing better adherence to safety guidelines. However, previous studies regarding vaccinations (Nyhan, Reifler, Richey, & Freed, 2014) found that eliciting anxiety by presenting negative consequences of not-vaccinating brings the opposite effect on motivation for future vaccination. This may indicate that people with already higher levels of anxiety will be more prone to adhere to safety guidelines irrespective of their conspiracy beliefs, but eliciting anxiety in less anxious individuals may be contra-effective. A potentially fertile ground for future research would be to check this issue in details.

Our hypothesis stating that paranoia-like beliefs are linked to lower adherence to safety measures received mixed support. In Study 1. we found small but significant negative relationships between reference paranoia-like beliefs and aspects of safety behaviours and general adherence to them, except hand-washing. On the other hand, in Study 2., we found only small negative relationships between persecutory beliefs and limiting direct contact with relatives and friends. These results may be dictated by stringent multiple comparison corrections done in Study 2, suggesting a rather weak effect.

We also observed a moderate positive correlation between symptoms of sociophobia and paranoia-like beliefs, which is in line with previous results (Schutters et al., 2012) and a small positive correlation with coronavirus related anxiety. Obtained results may indicate that despite higher levels of anxiety and associated safety behaviours (Freeman et al., 2007) paranoia-like beliefs in the general population may predispose to a lesser degree of adherence to epidemiological guidelines. However this effect may be ambiguous (Kowalski & Gawęda, 2020). We were not able to observe any of the studied variables to moderate relationships between paranoia-like beliefs and adherence to safety measures. Probably because of paranoia-like beliefs being a significant but weak predictor of adherence to safety guidelines.

Interestingly, we found that paranoia-like beliefs may play a role in the formation of coronavirus conspiracy beliefs. Replicating previous results (Brotherton & Eser, 2015), we established a partial mediation effect of paranoia-like beliefs between boredom reported during self-isolation period and coronavirus conspiracy beliefs. It may be illustrated as conspiracy theories being a filler for the less active mind (during boredom) when there is an individual inclination for anxiety, mistrust (Douglas & Sutton, 2011) and self-centred thinking (von Gemmingen, Sullivan, & Pomerantz, 2003) inherent for paranoia.

Mistrust associated with paranoia-like beliefs may also be reflected in our finding that trust in the government and media outlets are positively related to adherence to safety guidelines. We also found a moderation effect of trust in media outlets on the relationship between conspiracy beliefs and adherence to safety guidelines. Our results may reflect the media dependence on sensationalism and novelty (Marwick & Lewis, 2017). A possible byproduct of such an approach may be a lowered coverage, and thus accessibility, of the scientifically credible materials, i.e. safety guidelines during the pandemic (Klemm, Das & Hartmann, 2016).

Our study has some limitations. First, our design was cross-sectional, precluding the possibility to infer causality or at least coincidence in time. It would be of importance to provide longitudinal and experimental data on how conspiracy and paranoia-like beliefs may be impacting health-related behaviours during an epidemic or at least motivation to undertake such actions. It would also be of importance to investigate whether an epidemic results in a surge of conspiracy beliefs or are they at a relatively similar level irrespective of ongoing events. Next, non-probabilistic sampling and online data collection warrant caution in the generalization of the present results. Online surveys are completed by individuals who have access to the Internet, demonstrate a certain level of digital literacy, are paid for their participation or show high interest in a given topic. In consequence, individuals who do not have Internet access, do not need additional sources of income, are digitally illiterate or uninterested in a survey topic may be underrepresented in online samples. Finally, some of the constructs were measured with single items (boredom, trust in media or governmental outlets). This may hinder the reliability of obtained data, and future studies should employ more complex operationalisations of such variables.

In concluding remarks, along with other studies, our findings may have potential implications for guidelines and associated narratives. Paranoia-like and conspiracy beliefs are significantly related to lower adherence to safety guidelines with a small effect size (Freeman et al., 2020; Marinthe et al., 2020). Nevertheless, this effect may translate into a higher infection rate. However, some previous data indicate that direct targeting of conspiracy beliefs and activating anxiety related to certain afflictions may not work as intended (Nyhan et al., 2014). Our data also show that conspiracy beliefs are, in some part, a product of boredom in association with paranoia-like beliefs, and thus be firmly held and resistant to change (Freeman, 2007). It could indicate the importance of concentrating on other factors in seeking greater adherence to safety guidelines. In line with prior studies (Webster et al., 2020), our findings may suggest that actions increasing the trust in media outlets and internal motivation to follow safety guidelines may be potential targets for interventions.

Contributors

JK designed and conducted Study 2, analysed statistical data, and wrote initial draft of the manuscript. MM and ŁG edited the manuscript and contributed important conceptual input. Furthermore, ŁG took part in designing Study 2. MM, ZM and PG designed and conducted Study 1. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

On behalf of all authors I declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Study 1., conducted by MM, ZM & PG, was financed by Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education Grant: (DIALOG Grant No. 0013/2019; financing period: 2019-2021) and National Science Center Grant: 2017/26/M/HS6/00689. All authors declare no conflict of interest. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

References

- World Health Organization. (2020, April). Advice for public. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public.

- Brewer N.T., Chapman G.B., Gibbons F.X., Gerrard M., McCaul K.D., Weinstein N.D. Meta-analysis of the relationship between risk perception and health behavior: the example of vaccination. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 2007;26(2):136–145. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.2.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks S.K., Webster R.K., Smith L.E., Woodland L., Wessely S., Greenberg N., Rubin G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotherton R., Eser S. Bored to fears: Boredom proneness, paranoia, and conspiracy theories. Personality and Individual Differences, 80. 2015:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2015.02.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brotherton R., French C.C., Pickering A.D. Measuring belief in conspiracy theories: the generic conspiracist beliefs scale. Frontiers in Psychology. 2013;4:279. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown E., Gray R., Lo Monaco S., O'Donoghue B., Nelson B., Thompson A., Francey S., McGorry P. The potential impact of COVID-19 on psychosis: A rapid review of contemporary epidemic and pandemic research. Schizophrenia research. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2020.05.005. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cava M.A., Fay K.E., Beanlands H.J., McCay E.A., Wignall R. Risk perception and compliance with quarantine during the SARS outbreak. Journal of Nursing Ccholarship. 2005;37(4):343–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2005.00059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cichocka A., Marchlewska M., Golec de Zavala A. Does self-love or self-hate predict conspiracy beliefs? Narcissism, self-esteem, and the endorsement of conspiracy theories. Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2016;7(2):157–166. doi: 10.1177/1948550615616170. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Darwin H., Neave N., Holmes J. Belief in conspiracy theories. The role of paranormal belief, paranoid ideation and schizotypy. Personality and Individual Differences. 2011;50(8):1289–1293. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.02.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dobosz P., Zawiła-Niedźwiecki J. Government: Anti-science wave sweeps Poland. Nature. 2016;532(7600):441. doi: 10.1038/532441d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas K.M., Sutton R.M. Does it take one to know one? Endorsement of conspiracy theories is influenced by personal willingness to conspire. The British Journal of Social Psychology. 2011;50(3):544–552. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.2010.02018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer M., Coogan A.N., Faltraco F., Thome J. COVID-19 paranoia in a patient suffering from schizophrenic psychosis - a case report. Psychiatry Research. 2020;288 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman D. Suspicious minds: the psychology of persecutory delusions. Clinical Psychology Review. 2007;27(4):425–457. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman D., Garety P.A., Bebbington P.E., Smith B., Rollinson R., Fowler D., Kuipers E., Ray K., Dunn G. Psychological investigation of the structure of paranoia in a non-clinical population. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 186. 2005:427–435. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.5.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman D., Garety P.A., Kuipers E., Fowler D., Bebbington P.E., Dunn G. Acting on persecutory delusions: the importance of safety seeking. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45(1):89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman D., Gittins M., Pugh K., Antley A., Slater M., Dunn G. What makes one person paranoid and another person anxious? The differential prediction of social anxiety and persecutory ideation in an experimental situation. Psychological Medicine. 2008;38(8):1121–1132. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708003589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman D., Loe B., Kingdon D., Startup H., Molodynski A., Rosebrock L., Bird J. The revised Green et al., Paranoid Thoughts Scale (R-GPTS): Psychometric properties, severity ranges, and clinical cut-offs. Psychological Medicine. 2019:1–10. doi: 10.1017/S0033291719003155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman D., Waite F., Rosebrock L., Petit A., Causier C., East A., Lambe S. Coronavirus conspiracy beliefs, mistrust, and compliance with government guidelines in England. Psychological Medicine. 2020:1–13. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720001890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardt J. The symptom checklist-27-plus (SCL-27-plus): a modern conceptualization of a traditional screening instrument. Psycho-Social Medicine. 2008;5 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2736518/?report=classic Doc08Retrieved from. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys K.L., Myint M.T., Zeanah C.H. Increased Risk for Family Violence During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Pediatrics. 2020;146(1) doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin J., Sklar G.E., Oh V.M.S., Li S.C. Factors affecting therapeutic compliance: A review from the patient's perspective. Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management. 2008;4(1):269–286. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.s1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly B.D. Coronavirus disease: challenges for psychiatry. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science. 2020:1–2. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2020.86. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon C. Flattening-the-curve associated with reduced COVID-19 case fatality rates- an ecological analysis of 65 countries. The Journal of Infection. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.007. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klemm C., Das E., Hartmann T. Swine flu and hype: a systematic review of media dramatization of the H1N1 influenza pandemic. Journal of Risk Research. 2016;19(1):1–20. doi: 10.1080/13669877.2014.923029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kossowska M., Bukowski M. Motivated roots of conspiracies: The role of certainty and control motives in conspiracy thinking. In: Bilewicz M., Cichocka A., Soral W., editors. The psychology of conspiracy. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 2015. pp. 145–161. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski J., Gawęda Ł. Persecutory beliefs predict adherence to epidemiological safety guidelines over time–a longitudinal study. Psychological Medicine. 2020:1–2. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720002792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuncewicz D., Dragan M., Hardt J. Walidacja polskiej wersji kwestionariusza The Symptom Checklist-27-plus [Validation of the Polish version of the symptom checklist-27-plus questionnaire] Psychiatria polska. 2014;48(2):345–358. http://www.psychiatriapolska.pl/uploads/images/PP_2_2014/345Kuncewicz_PsychiatrPol2_2014.pdf Retrieved from. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowsky S., Oberauer K., Gignac G.E. NASA Faked the Moon Landing—Therefore, (Climate) Science Is a Hoax: An Anatomy of the Motivated Rejection of Science. Psychological Science. 2013;24(5):622–633. doi: 10.1177/0956797612457686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchlewska M., Cichocka A., Kossowska M. Addicted to answers: Need for cognitive closure and the endorsement of conspiracy beliefs. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2018;48(2):109–117. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marinthe G., Brown G., Delouvée S., Jolley D. Looking out for myself: Exploring the relationship between conspiracy mentality, perceived personal risk and COVID-19 prevention measures. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2020;25(4):957–980. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/cm9st. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marwick A., Lewis R. Data & Society Research Institute; 2017. Media Manipulation and Disinformation Online. [Google Scholar]

- Nyhan B., Reifler J., Richey S., Freed G.L. Effective messages in vaccine promotion: a randomised trial. Pediatrics. 2014;133(4):e835–e842. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez V., Uddin M., Galea S., Monto A.S., Aiello A.E. Stress, adherence to preventive measures for reducing influenza transmission and influenza-like illness. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2012;66(7):605–610. doi: 10.1136/jech.2010.117002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum B., North C.S. Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2008017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prati G., Pietrantoni L., Zani B. Compliance with recommendations for pandemic influenza H1N1 2009: the role of trust and personal beliefs. Health Education Research. 2011;26(5):761–769. doi: 10.1093/her/cyr035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutters S.I.J., Dominguez M.-D.-G., Knappe S., Lieb R., van Os J., Schruers K.R.J., Wittchen H.-U. The association between social phobia, social anxiety cognitions and paranoid symptoms. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2012;125(3):213–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D. Coronavirus: medical experts denounce Trump's theory of "disinfectant injection.". The Guardian. 2020 http://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/23/trump-coronavirus-treatment-disinfectant Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Smith M. International COVID-19 tracker update: 18 May | YouGov. YouGov. 2020 https://yougov.co.uk/topics/international/articles-reports/2020/05/18/international-covid-19-tracker-update-18-may Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- van Gelder N., Peterman A., Potts A., O'Donnell M., Thompson K., Shah N., Oertelt-Prigione S., Gender and COVID-19 working group COVID-19: Reducing the risk of infection might increase the risk of intimate partner violence. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;21 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100348. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Gemmingen M.J., Sullivan B.F., Pomerantz A.M. Investigating the relationships between boredom proneness, paranoia, and self-consciousness. Personality and Individual Differences. 2003;34(6):907–919. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00219-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Webster R.K., Brooks S.K., Smith L.E., Woodland L., Wessely S., Rubin G.J. How to improve adherence with quarantine: rapid review of the evidence. Public Health. 2020;182:163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood M.J., Douglas K.M., Sutton R.M. Dead and Alive: Beliefs in Contradictory Conspiracy Theories. Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2012;3(6):767–773. doi: 10.1177/1948550611434786. [DOI] [Google Scholar]