Abstract

Background

Klebsiella pneumoniae is a leading cause of intractable hospital-acquired multidrug-resistant infections and carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae (CPKp) are particularly feared. Most of the clinical isolates produce capsule as a major virulence factor. Recombination events at the capsule locus are frequent and responsible for capsule diversity within Klebsiella spp. Capsule diversity may also occur within clonal bacterial populations generating differences in colony aspect. However, little is known about this phenomenon of phenotypic variation in CPKp and its consequences.

Results

Here, we explored the genetic causes of in vitro switching from capsulated, mucoid to non-mucoid, non-capsulated phenotype in eight clinical CPKp isolates. We compared capsulated, mucoid colony variants with one of their non-capsulated, non-mucoid isogenic variant. The two colony variants were distinguished by their appearance on solid medium. Whole genome comparison was used to infer mutations causing phenotypic differences. The frequency of phenotypic switch was strain-dependent and increased along with colony development on plate. We observed, for 72 non-capsulated variants that the loss of the mucoid phenotype correlates with capsule deficiency and diverse genetic events, including transposition of insertion sequences or point mutations, affecting genes belonging to the capsule operon. Reduced or loss of capsular production was associated with various in vitro phenotypic changes, affecting susceptibility to carbapenem but not to colistin, in vitro biofilm formation and autoaggregation.

Conclusions

The different impact of the phenotypic variation among the eight isolates in terms of capsule content, biofilm production and carbapenem susceptibility suggested heterogeneous selective advantage for capsular loss according to the strain and the mutation. Based on our results, we believe that attention should be paid in the phenotypic characterization of CPKp clinical isolates, particularly of traits related to virulence and carbapenem resistance.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12866-020-02007-y.

Keywords: Capsule, Carbapenem, Insertion sequence, Biofilm, Klebsiella pneumoniae

Background

Klebsiella pneumoniae is a Gram negative, capsulated, non-motile, rod-shaped bacterium commonly found in the gut flora of healthy individuals, but it can be also found in the environment, particularly in soil and water [1]. Of great concern are infections caused by K. pneumoniae, mostly targeting the respiratory and urinary tracts and causing life-threatening infections including pneumonia, sepsis, meningitis, and pyogenic liver abscesses, particularly in health-care settings [2]. Colistin and carbapenems are last-line drugs for K. pneumoniae infections but K. pneumoniae lineages showing resistance to those drugs emerged and disseminated worldwide, challenging the already limited treatment options [3, 4]. World Health Organization (WHO) included carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae (CPKp) in the list of PRIORITY 1 critical pathogens for new drugs [5]. An understanding of the pathobiology of K. pneumoniae infections would help in developing new control strategies and possible vaccines [6]. Several virulence factors, including the lipopolysaccharide (LPS), fimbriae, siderophores and the capsular polysaccharide (CPS), are contributing to K. pneumoniae’s ability to thrive in the environment and in the host.

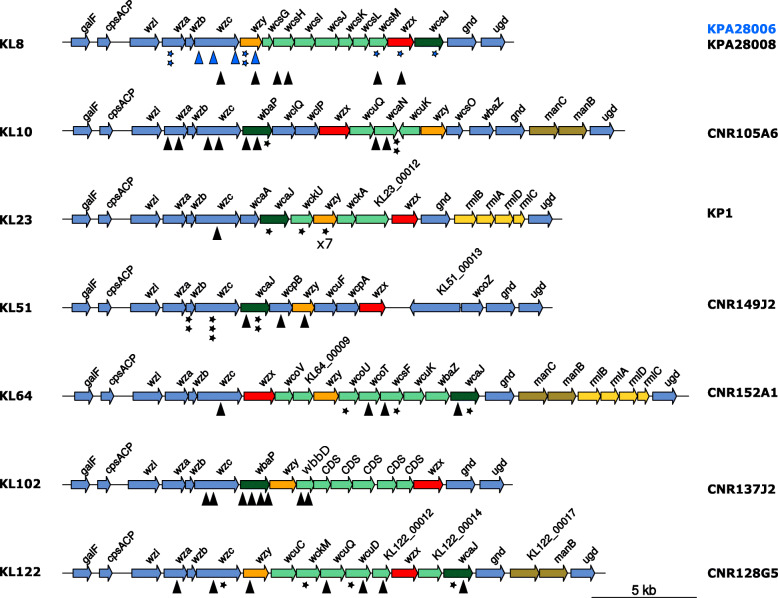

The capsule can ensure resistance to antimicrobial peptides, phagocytosis, and complement-mediated killing [7–10]. More than 77 capsular-types (K-type) have been reported in clinical isolates of K. pneumoniae [11]. Large-scale recombination events involving the capsule biosynthesis (cps) region drive an extensive variation, even within the same clonal complex (CC), as described for CC258 isolates [12]. The genes responsible for capsule synthesis are organized into an operon, from galF through cpsACP, wzi, wza, wzb, wzc and ugd, with conserved functions and organization and additional glycosyltransferase genes [11] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Capsular loci maps. Capsular regions from the seven capsular types investigated in this work are represented from galF to ugd. Genes are indicated by arrows. Blue arrows correspond to core genes from the different capsule loci. Glycosyltransferases are indicated in green. Orange and red arrows represent genes encoding the polymerase and the flippase, respectively. In yellow/dark yellow the genes involved in sugar/repeat unit synthesis (non-conserved). KL numbers are indicated on the left and the analyzed strain of each K-type on the right. IS insertions are represented by triangles and other mutations events by stars as specified in Table 2. Two strains of capsular type KL8 were investigated, blue signs correspond to KPA28006 and black ones to KPA28008

Recent studies shed light on the role of the different genes orchestrating capsule production in K. pneumoniae. Mutations in wza, wzb, wzc and wzy resulted in reduced amount or absence of capsule, corresponding to a rough, non-mucoid appearance on plate, along with decreased serum resistance and high susceptibility to neutrophilic phagocytosis [13]. On the other hand, inactivation of wcaJ, a glycosyltransferase involved in colanic acid synthesis, led to a non-capsulated, non-mucoid variant, which was less efficiently phagocytosed compared to the capsulated K. pneumoniae, and which showed a better ability to form biofilm on polystyrene surfaces, and an altered colistin susceptibility [14]. However, capsule production is controlled by a complex regulatory network involving several genes outside the cps cluster [15]. Interestingly, loss of mucoid-capsular phenotype has also been reported to occur within the host due to various mutations in the cps cluster [16]. Capsule loss due to mutations in the cps operon has been shown to occur among clinical ST258 isolates, leading to a better ability to form biofilm and persist in the mice bladder [17]. Altogether, these data suggest an evolutionary advantage that capsule loss can confer to K. pneumoniae in the human host and environment under certain circumstances. When analyzed in the laboratory, clinical isolates of K. pneumoniae may exhibit mixed populations, noticed by the presence of heterogeneous colony appearance on solid media. This phenomenon may reflect changes in the capsule production within a clonal bacterial population. It is referred as to phenotypic variation, usually from capsulated to non-capsulated variant. However, appearance of colony variants due to changes in capsule biosynthesis might also occur in vitro depending on medium, time and temperature of incubation [18]. This could subsequently lead to the storage and transfer of mixed samples across different clinical laboratories, thus hampering the correct phenotypic characterization of clinical isolates.

Here, we explored the genetic causes of in vitro switching from capsulated, mucoid (M) to non-capsulated, non-mucoid (NM) phenotype in eight clinical CPKp isolates. The frequency of phenotypic switch was strain-dependent and increased along with colony development on plate. The loss of the mucoid phenotype resulted from diverse genetic events: Insertion Sequence (IS) transposition, deletion or point mutations occurring in genes of the cps locus. In one variant, a second mutation inactivated rfaH, a regulatory gene of capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis [19]. Variation of the impact of the phenotypic switch among the eight isolates in terms of capsule content, biofilm production and carbapenem susceptibility suggested heterogeneous selective advantage for capsular loss according to the strain and the mutations.

Results

Non-mucoid variants arise at various frequencies in different K. pneumoniae strains

All along a screening of clinical CPKp strains, we noticed that upon isolation from − 80 °C glycerol stocks, CPKp often exhibited a heterogeneous population with mostly mucoid (M) colonies but also a variable proportion of colonies with a translucent, non-mucoid (NM) appearance on plate. This observation led us to analyze more systematically the population heterogeneity. Hence, we selected eight CPKp isolates belonging to seven STs (ST107, ST16, ST11, ST147, ST383, ST39, ST855) and expressing different carbapenemases (KPC, VIM-1, OXA-48 and OXA-181), as shown in Table 1. The population heterogeneity could be better visualized on TSA medium. We also observed that, when streaked on TSA, M colonies could give rise to either a mixed population (M and NM) or to a pure M population. Furthermore, M colonies might exhibit non-mucoid sectors (Fig. 2a). On the other hand, NM colonies re-isolated on TSA led to homogeneous NM population. The ability of M colonies to produce NM segments was dependent on the incubation time (> 24 h), indicating further selection and growth advantage of NM variants at later growth stages on solid medium.

Table 1.

Strains analyzed in this work

| Strain& | STa | wzi | K-typeb | Resistance genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

KP1 [20] SAMN14419408 |

ST39 | wzi83 | KL23 | aminoglycoside: aac(6′)-Ib3; aac(3)-Iia; aph(6)-Id; macrolide: mph(E); msr(E); phenicol: catA1; catB2; sulphonamide: sul1;sul2; tetracycline: tet(D); trimethoprim: dfrA14; dfrB1; β-lactam: blaSHV-40; blaOXA-9; blaSCO-1; blaVIM-1; fosfomycin: fosA |

|

CNR128G5 SAMN14419403 |

ST383 | wzi162 | KL122 | aminoglycoside: aadA2b; aac(3)-IIa; aac(6′)-Ib3; rmtB; quinolone: oqxA; sulphonamide: sul1; tetracycline: tet(A); β-lactam: blaOXA-9; blaSHV-145; blaCTX-M-14; blaCTX-M-15; blaKPC-2; blaOXA-1; blaTEM-1B; fosfomycin: fosA |

|

CNR152A1 SAMN14419404 |

ST147 | wzi64 | KL64 | aminoglycoside: aph(3″)-Ib; aph(6)-Id; sulphonamide: sul2; trimethoprim: dfrA14; β-lactam: blaSHV-11; blaCTX-M-15; blaKPC-3; blaTEM-1B |

|

CNR105A6 SAMN14419407 |

ST855 | wzi100 | KL10 | aminoglycoside: aac(6′)-Ib; aadA1; aph(3″)-Ib; aph(6)-Id; phenicol: catA1; sulphonamide: sul1; tetracycline: tet(B); β-lactam: blaSHV-81; blaKPC-2; blaOXA-9; blaTEM-1A |

|

SAMN14419405 |

ST11 | wzi334 | KL8 | aminoglycoside: aph(3′)-VIa; aadA1; aac(6′)-Iq; phenicol: cmlA1; sulphonamide: sul1; sul2; tetracycline: tet(B); tet(D); trimethoprim: dfrA15; β-lactam: blaKPC-2; blaSHV-182; blaCTX-M-2 |

|

SAMN14419406 |

ST11 | wzi334 | KL8 | aminoglycoside: aph(3′)-Via; quinolone: oqxA; oqxB; tetracycline: tet(D); β-lactam: blaKPC-2; blaSHV-182; blaCTX-M-2 |

|

CNR149J2 SAMN14419409 |

ST16 | wzi50 | KL51 | aminoglycoside: aac(6′)-Ib-cr; aadA2; aph(3′)-Ia; quinolone: qnrS1; macrolide: mph(A); sulphonamide: sul1; trimethoprim: dfrA12; β-lactam: blaSHV-145; blaCTX-M-15; blaOXA-1; blaOXA-181; blaTEM-1B |

|

CNR137J2 SAMN14419410 |

ST107 | wzi173 | KL102 | aminoglycoside: aac(3)-Iid; aph(3″)-Ib; aph(6)-Id; quinolone: qnrS1; macrolide: mph(A); sulphonamide: sul2; tetracycline: tet(A); trimethoprim: dfrA17; β-lactam: blaSHV-145; blaLAP-2; blaOXA-48; blaTEM-1B |

&Sequence accession numbers are also indicated, aST = Sequence Type; bK-type = capsular type

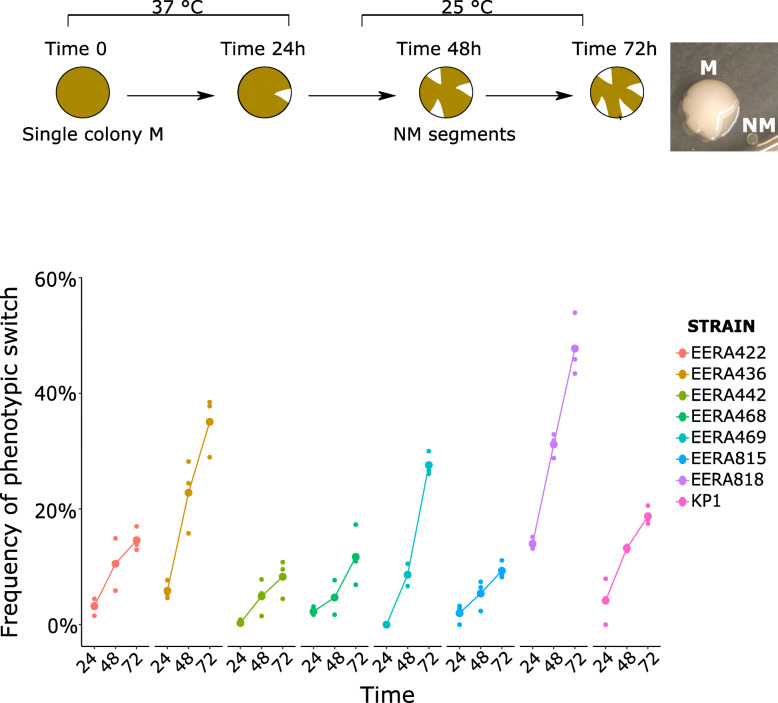

Fig. 2.

Frequency of phenotypic switch in the eight CPKp isolates. a. Left: Workflow followed to visualize and quantify the colony switch from mucoid to non-mucoid phenotype; right: two colonies with NM sectors. b. Frequency of phenotypic variation (colony with non-mucoid sectors) monitored over 72 h in the eight CPKp strains. The first 24 h, the isolates were incubated at 37 °C then at 25 °C to observe the appearance of NM segments. M = mucoid, NM = non-mucoid. Strain names are indicated according to the figure key. Frequency and standard deviations are given in Table S4

In order to determine whether the frequency of switching from M to NM was variable among the selected strains, we quantified colony variants by counting the number of colonies exhibiting non-mucoid segments after 24 h incubation at 37 °C and after 24 and 48 additional hours of incubation at 25 °C (Fig. 2b). Re-isolation of bacteria from these segments confirmed that they led to stable NM colonies. We observed, for the eight strains, a high rate of colony switching, ranging from 10% to more than 40% colonies with NM sectors after 72 h of incubation. We observed the highest frequency (from 15% at 24 h to 47% of the population at 72 h) for K. pneumoniae CNR137J2 belonging to ST107 and expressing KL102-type capsule.

Different mutational events led to a non-mucoid phenotype

To characterize the diversity of the NM variants selected on TSA plates, we isolated 6 to 11 independent NM isolates for each of the eight strains and performed whole genome sequencing (WGS) to compare them with the original isolates. In total, we analyzed 72 NM variants. Libraries were first constructed by tagmentation (>50x coverage). However, we obtained a low or even partial coverage of the AT-rich cps locus (Fig. S1), precluding the confident identification of mutations responsible for the NM phenotype. Similarly, Wyres et al. were recently unable to determine the K-type of 129 out of 393 K. pneumoniae genomes sequenced by tagmentation [22]. The 72 NM variants were sequenced following enzymatic digestion of the genomic DNA by a mix of nucleases, providing a uniform coverage of the K. pneumoniae genome and no discrimination of AT-rich regions (Fig. S1). We identified in all the isolates analyzed, a mutation in the cps locus (Fig. 1, Table 2), predicted to be responsible for the NM phenotype. In 26 NM variants, up to five additional mutations were detected elsewhere in the genome. These mutations might have also contributed to the overgrowth of the NM sector (Table S1). In particular, in the NM3 variant of strain CNR149J2 we identified a four-base pair (bp) duplication disrupting the rfaH gene, an activator of capsule biosynthesis [19]. Fifty-six percent (40/72) of NM mutants resulted from IS insertion (IS1-, ISL3-, IS5-like) in different essential genes for capsule synthesis (Table 2). In the other variants, we identified point mutations (n = 14), including five non-sense mutations or indels (n = 18) (Table 2). The genes most frequently affected were wcaJ (22.2%), a colanic acid biosynthesis UDP-glucose lipid carrier transferase which mediates the first step of capsule biosynthesis in Escherichia coli [23] and plays a role in virulence and phage sensitivity in K. pneumoniae [24], followed by wzc (20.8%), encoding a putative tyrosine-kinase and wzy (15.3%) encoding the polymerase. Other mutated genes encode different glycosyltransferases involved in the complex cps synthesis (29.2%) or essential genes like wza, wzb and wzx (5.6, 2.8 and 2.8%, respectively). In the case of KP1 strain, seven out of the eleven independent NM isolates analyzed shared the same mutation in wzy: a deletion of one T in a track of nine T residues, likely resulting from a slippage of the DNA polymerase during chromosome replication.

Table 2.

Mutations in the capsule synthesis cluster detected in non-mucoid variants

| Strain | NM Variant | Gene | Mutationa, b |

|---|---|---|---|

| CNR128G5 | NM1 | wza | ISKpn25 (pos 382) |

| NM2 | wzc | IS903b (pos 2036) | |

| NM3 | wzc | G1699T (D567Y) | |

| NM4c | wzy | ISKpn25 (pos 319) | |

| NM5 | wckM | Δ4 bp (AAAC) (pos 729); (*) | |

| NM6 | wcuQ | ISKpn25 (pos 332) | |

| NM7 | wcuD | ΔA (pos 38); (*) | |

| NM8 | wcuD | ISKpn25 (pos 1073) | |

| NM9 | KL122_00012 | ISKpn25 (pos 796) | |

| NM10 | wcaJ | insAAd (pos 744); (*) | |

| NM11 | wcaJ | IS1-like e (pos 840) | |

| CNR152A1 | NM1 | wzc | ISKpn26 (pos 738) |

| NM2c | wcaJ | IS903b (pos 602) | |

| NM3 | wcaJ | T389A (I130N); G452C (G151A) | |

| NM4 | wcoT | IS903b (pos 866) | |

| NM5 | wcsF | IS903b (pos 1126) | |

| NM6 | wcsF | G118T; (*) | |

| NM7 | wcoU | insAd (pos 811); (*) | |

| CNR105A6 | NM1 | wza | IS1-like (pos 998) |

| NM2 | wza | IS1-like (pos 998) | |

| NM3 | wzc | IS903b (pos 2073) | |

| NM4c | wzc | IS1-like (pos 542) | |

| NM5 | wbaP (wcaJ) | IS903b (pos 699) | |

| NM6 | wbaP (wcaJ) | IS1-like (pos 316) | |

| NM7 | wbaP (wcaJ) | T997G (S333A) | |

| NM8 | wcaN | Δ18bp (pos 190–208); (*) | |

| NM9 | wcaN | IS1-like (pos 358) | |

| NM10 | wcaN | IS1-like (pos 358) | |

| NM11 | wcaN | C79A (V27L) | |

| KPA28006 | NM1c | wzc | IS903b (pos 715) |

| NM2 | wzc | IS1-like (pos 244) | |

| NM3 | wzc | IS1-like (pos 2146) | |

| NM4 | wzy | ΔC (pos 274); (*) | |

| NM5 | wzy | ΔC (pos 274); (*) | |

| NM6 | wcsM | ΔA (pos 339); (*) | |

| NM7 | wcaJ | ΔA (pos 1279); (*) | |

| NM8 | wzx | ΔA (pos 422); (*) | |

| NM9 | wza | A278T (L93Q) | |

| KPA28008 | NM1 | wzc | IS1-like (pos 950) |

| NM2 | wzy | IS1-like (pos 319) | |

| NM3 | wcsM | IS903b (pos 505) | |

| NM4c | wzx | IS1-like (pos 342) | |

| NM5 | wcsH | IS1-like (pos 605) | |

| NM6 | wcsH | IS1-like (pos 914) | |

| CNR149J2 | NM1 | wzb | C447A (*) |

| NM2 | wzc | T345A (*) | |

| NM3c | wzc | Δ11bp (pos 635); (*) | |

| NM4 | wzc | G787C (A263P) | |

| NM5 | wcaJ | IS1-like (pos 905) | |

| NM6 | wcaJ | T1145G (L382R) | |

| NM7 | wcaJ | A111T (*) | |

| NM8 | wcpB | IS1-like (pos 347) | |

| NM9 | wzy | ISKox3 (pos 591) | |

| NM10 | wzb | T68G (L23R) | |

| CNR137J2 | NM1 | wzc | IS903b (pos 209) |

| NM2 | wzc | IS1-like (pos 760) | |

| NM3 | wbaP (wcaJ) | IS1-like (pos 616) | |

| NM4 | wbaP (wcaJ) | IS1-like (pos 1312) | |

| NM5 | wbaP (wcaJ) | IS1-like (pos 247) | |

| NM6c | wbaP (wcaJ) | IS1-like (pos 888) | |

| NM7 | wbbD | IS1-like (pos 319) | |

| NM8 | wbbD | IS1-like (pos 284) | |

| KP1 | NM1 | wzc | IS1-like (pos 469) |

| NM2 | wzy | T736C (S246P) | |

| NM3 | wzy | ΔT (pos 864); (*) | |

| NM4 | wzy | ΔT (pos 864); (*) | |

| NM5 | wzy | ΔT (pos 857); (*) | |

| NM6c | wzy | ΔT (pos 864); (*) | |

| NM7 | wzy | ΔT (pos 864); (*) | |

| NM8 | wzy | ΔT (pos 864); (*) | |

| NM9 | wcaJ | A31T; (*) | |

| NM10 | wckU | ΔA (pos 16); (*) |

aIn parentheses are indicated: for point mutations, the amino acid change and for other mutations, the position in the gene, b the star indicates either a non-sense mutation or a frameshift c; NM variant selected for in depth phenotypic analysis (in bold); d Ins for insertion; eIS1-like correspond to IS1R, IS1SD, IS1F, ISKpn14 and closely related ISs

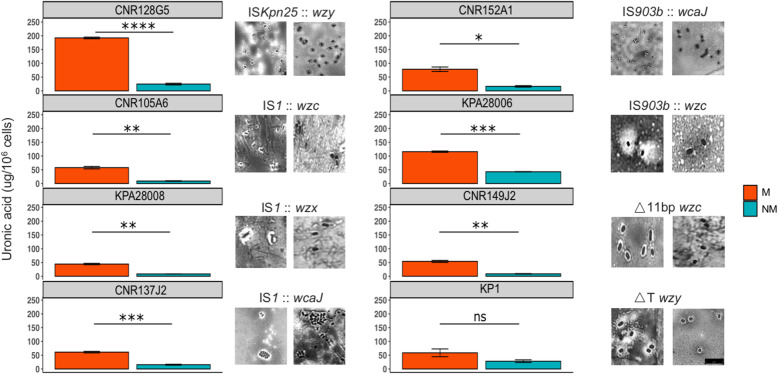

Phenotypic comparison of mucoid and non-mucoid variants

For each CPKp strain, we selected one NM variant with different mutations in wcaJ, wzc, wzx, wzy (indicated by the “&” symbol in Table 2) and investigated their impact on phenotypes contributing to their dissemination and persistence in the host.

To evaluate the impact of mutations on capsule production, we quantified uronic acid, a major constituent of the polysaccharidic capsule. In seven out of eight pairs, the NM variant showed a significantly lower amount of uronic acid compared to M variant, confirming that the loss of the mucoid trait resulted from the loss or the reduction of capsule production (Fig. 3). In the remaining strain, KP1, the NM variant (frameshifted in wzy), although it did not reach significance, showed a 2-fold decrease in the uronic acid production. The impact on the capsule synthesis in the NM variants was confirmed by capsule visualization by India ink negative staining (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Capsule quantification and visualization in M and NM variants. Uronic acid assay [25] was carried out to quantify capsular polysaccharides in the eight CPKp and their selected NM variants. In all but one couple (KP1), the NM variant exhibited a significant decrease in CPS production compared to the WT isolate. In particular, a stronger difference was noticed in the case of CNR128G5 (p-value ****), followed by CNR137J2 and KPA28006. India ink staining was performed to visually detect decrease/absence of capsule in the non-mucoid variant (right image). The scale bar in each image represent 5 μm. Non-mucoid isolates selected for each K. pneumoniae strain showed different mutation events (Table 2). M = mucoid, NM = non-mucoid

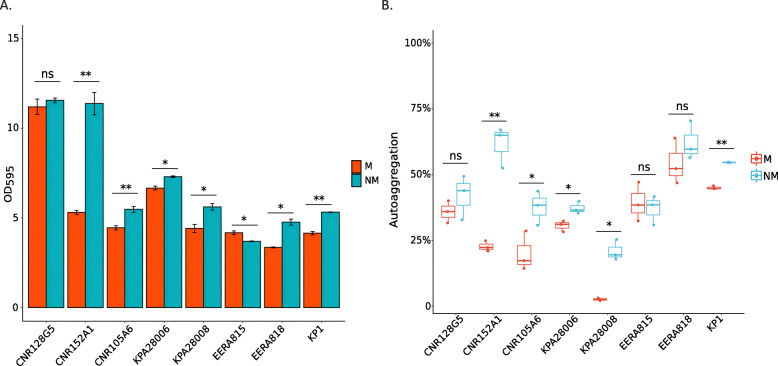

We investigated and compared the ability of M and NM variants to form biofilm on polystyrene surfaces. For six out of eight strains (CNR152A1, CNR105A6, KPA28006, KPA28008, CNR137J2, and KP1) the NM variants significantly produced more biofilm after 24 h of incubation (Fig. 4a) compared to the parental M strains. However, in the case of CNR149J2 the NM variant produced less biofilm than the parental strain. This opposite phenotypic effect of capsule loss might be related to the mutation in rfaH, which has been shown to have a pleiotropic effect [19]. Therefore, the contribution of the capsule to biofilm formation on polystyrene was variable according to strain- and/or mutations.

Fig. 4.

In vitro biofilm production and autoaggregation. a. The WT isolates and the selected NM variants were characterized for their ability to produce biofilm in M63 minimal medium supplemented with glucose. In six out of eight couples (CNR152A1, CNR105A6, KPA28006, KPA28008, CNR137J2 and KP1), the NM variant was more efficient in biofilm formation than the parental M strain. Only CNR149J2 showed an opposite trend: the M variant showed a better ability to form biofilm under tested conditions. p-values of < 0.001 ***, < 0.01 ** and < 0.05 * were considered significant. b. Autoaggregation assay of M and NM variant in spent M63/Glu medium. M = mucoid, NM = non-mucoid are indicated according to the figure key

Autoaggregation might contribute to biofilm formation [26, 27]. The autoaggregative behavior of M and NM derivatives was quantified in spent M63/Glu minimal medium over 24 h at room temperature. Interestingly, all the NM variants but one (CNR149J2) showed, overall, a better ability to autoaggregate under the tested conditions (Fig. 4b). Particularly, the NM variants of CNR152A1, CNR105A6, KPA28006, KPA28008, KP1, which produce more biofilm, showed an increased autoaggregation compared to the parental isolates.

Curli production contributes to biofilm formation and capsule loss can unmask the fimbriae [28]. We compared M and NM isolates for curli production by the Congo red (CR) assay. Among the eight strains analyzed, only one tested positive: CNR128G5, which shows a high level of biofilm formation independently of the M or NM phenotype (Fig. S2). For all the analyzed isolates, we did not observe differences between NM and M variants in the CR assay (Fig. S2), suggesting that capsule loss did not impact significantly on fimbriae production in these isolates.

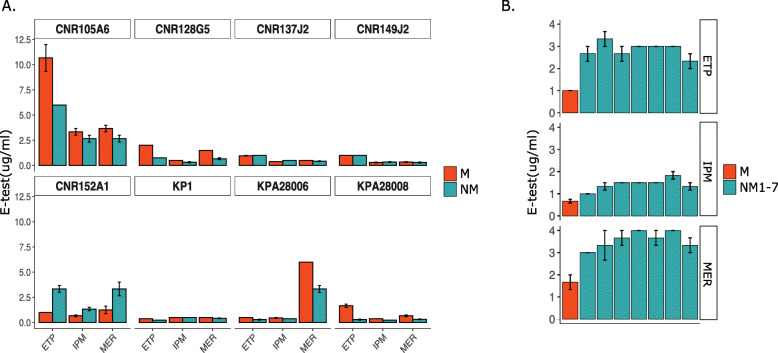

Since the eight strains analyzed harbored a carbapenemase-encoding gene, we compared the susceptibility of both the parental and the NM variants towards carbapenems, which are targeting bacterial cell wall synthesis. Interestingly, we found that minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) for the clinically relevant carbapenems (ertapenem, meropenem, imipenem) determined by E-test were different in five out of the eight strains for the M and NM variants. Four NM variants showed an increased susceptibility to those drugs. On the other hand, for CNR152A1, the NM variant (CNR152A1-NM2) - mutated in wcaJ, was surprisingly more resistant than the parental M strain (Fig. 5). In order to determine whether this effect resulted exclusively from the mutation in wcaJ, genomes were carefully checked for any additional mutation, IS insertion or recombination but we did not identify any in genes known to contribute to β-lactam resistance such as the major porins (ompK35 and ompK36) and their regulator ompR/envZ and the PBPs (PBP1F, 1A, 1B, 2, 2D). In order to determine whether this effect was isolate or mutation specific, we determined the susceptibility to carbapenems by E-test in the six other independent NM variants from CNR152A1 harboring different mutations in the cps locus (Table 2). Consistently with what was observed for NM3, the six other NM variants showed a reduced carbapenem susceptibility. These results confirmed that the reduced susceptibility of CNR152A1 non-mucoid variants was not specific to the wcaJ mutant but likely related to the loss of capsule.

Fig. 5.

Carbapenem susceptibility profiles of the eight CPKp strains and their NM variants. a. The carbapenem susceptibility of the eight CPKp strains and the NM variants was quantified by E-test. ETP = ertapenem; IPM = imipenem and MER = meropenem. Four out of eight NM variants selected showed an increase in susceptibility towards the carbapenem tested, whereas the NM deriving from CNR149J2, CNR137J2 and KP1 did not show any difference compared to the WT mucoid strain. Only CNR152A1-NM2 showed a different behavior, with decreased susceptibility, particularly against meropenem and ertapenem. b. Carbapenem susceptibility by E-test of the seven NM variants derivatives of CNR152A1. M = mucoid, NM = non-mucoid. Experiments were performed in triplicates. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM)

Capsule has been shown to play a role in resistance to antimicrobial peptides, including polymyxin B, affecting the interaction with the bacterial outer membrane [29]. Those antibiotics show mode of action and mechanisms of resistance different from ß-lactams. We measured the susceptibility levels of both the parental and the NM variants towards polymyxin B and colistin. However, we did not observe any difference between the M and the NM variant for the eight pairs (Table S2).

Discussion

Microbial populations inhabit diverse and constantly changing niches, facing oscillations between abundance of nutrients, which allows a prolific bacterial growth, and hostile environments, where individuals adopt strategies to cope with the scarcity of nutrients [30]. One of them is the phenotypic variation, where a population can switch among multiple phenotypes to survive in challenging habitats imposed, for instance, by the antibiotic pressure and the host immune system. In a scenario where multidrug resistant (MDR) clinical isolates are incessantly emerging and spreading, the adoption of such strategies from bacterial populations can further challenge their characterization in the laboratory [31]. K. pneumoniae can undergo phenotypic variation, switching from mucoid to non-mucoid colony aspect [32]. Hypo- or non-mucoid appearance has been associated with the loss of capsule in Klebsiella and different degrees of mucoidity may indicate diverse mutations affecting capsule synthesis genes [16, 17]. These colony variants might arise in vivo, but also following their isolation in the laboratory. Colony variants can be observed on solid media, but they go frequently overlooked, as they show only subtle differences. Here, by analyzing NM variants deriving from eight clinical CPKp, we showed some phenotypic consequences of the capsule loss potentially contributing to NM variants selection. These phenotypic switches occurred at various frequencies in the different strains analyzed.

By using a newly developed high throughput method called TraDisort, Dorman et al. identified numerous loci involved in the regulatory network of capsule synthesis in K. pneumoniae [15]. However, here we showed that in vitro transition on solid media from M to NM variant (n = 72) of eight CPKp clinical isolates is driven by mutations occurring in the capsule locus upon the insertion of IS elements, SNPs and deletions. In a single NM variant (CNR149J2 NM3), we identified both a mutation inactivating wzc, which encodes a tyrosine-protein kinase essential for capsule biosynthesis and a mutation in the rfaH gene encoding a transcriptional regulator of the cps operon [19]. In other NM variants, the disruption of wzc led to a non-capsulated phenotype and the contribution of the rfaH mutation to the phenotype remains to be determined. Except this specific case, under the conditions we used, mutations in genes involved in this regulatory network, which would reduce capsule synthesis, do not provide a sufficient selective advantage for growth. Recently, Lee et al. observed different colony aspects (mucoid and non-mucoid) among CPKp isolated successively from a single patient [16]. They showed that the within-host evolution of K. pneumoniae non-mucoid variants was driven by IS insertion and amino acid alterations in genes essential for capsule synthesis. Likewise, we observed that the NM phenotype among CPKp clinical isolates was related to genetic events happening in the cps cluster, particularly targeting wcaJ, followed by wzc and wzy genes. These core genes are essential for capsule synthesis in E. coli and Klebsiella spp. and their disruption is associated with altered capsule polysaccharide polymerization [14, 15, 17, 33]. However, we identified among the NM variants analyzed, mutations in other genes of the cps operon, confirming their contribution to capsule synthesis and the selective advantage for their inactivation. For example, in the strain CNR128G5, the 11 NM variants were mutated in eight different cps genes. One exception is the first gene of the operon: wzi, as no variant harboring a mutation in this gene was observed. Wzi was shown to be an outer-membrane lectin contributing to the formation of the bacterial capsule [34]. Its gene inactivation will probably not lead to a metabolic advantage. However, IS insertion in this gene are predicted to have a polar effect on the downstream genes essential for capsule biosynthesis [35]. The absence of mutation in this gene might indicate a fitness cost of its inactivation under the condition used for capsule mutant selection.

Characterization of selected NM mutants unveiled a diverse landscape of mutations, with the majority (55.6%) linked to IS elements jumping into cps genes. Transposable elements are an important source of genetic variability. Movements of ISs are hardly detected using short-read sequencing. Therefore, this type of capsule locus inactivation might be overlooked while analyzing K. pneumoniae variants. Transposition is generally maintained at low level to preserve the integrity of the bacterial host genome. However, ISs can undergo bursts of transposition under stress conditions, including oxidative stress and starvation [36], which likely occurred during the prolonged incubation on TSA plates at 25 °C. In the case of KP1, the most frequent event was a thymine deletion in wzy (delT), occurring in 6 out of 10 NM independent variants (Table 2). These deletions occurred in a poly(T) track (nt 857–867 of the gene), which could lead to replication slippage, thus increasing the probability of frameshift errors. Similarly, we observed a high rate of frameshift mutations in KPA28006 with three adenosine deletions in wcsM, wcaJ and wzx, corresponding to poly-A track. Interestingly, we also isolated two variants with the same cytosine deletion. This residue is followed by a stretch of a poly-T track. These regions with stretches of nucleotides might be particularly prone to polymerase slippage. The frequency of mucoid to non-mucoid switch in these two strains was among the lowest we have observed. It is possible that the frequency of IS transposition in KP1 (1 out of 11 NM isolates) and KPA28006 (3 out of 9 NM isolates) was lower than in other strains under the condition used, revealing this mechanism of phase variation by increasing its relative frequency. On the other hand, the highest frequency of conversion from M to NM appearance was observed for CNR137J2 (more than 40% over 3-days incubation), followed by CNR152A1 and KPA28008. Notably, in the case of CNR137J2 and KPA28008, all mutants resulted from IS transposition (seven IS1-like insertions and one IS903b in CNR137J2 and five IS1-like insertions and one IS903b in KPA28008). One could hypothesize that the high rate of switching in these two strains is due to a higher rate of IS transposition and possibly to IS transposition bursts. In order to assess whether these differences could be related to different occurrence of IS elements in the eight parental strains, we estimated the number of the ISs that were responsible for a non-mucoid phenotype among the 72 isolates we analyzed (Table S3). However, we were not able to correlate the transposition frequency and the number of ISs in the parental strain. Indeed, in the strains KPA28008 and CNR137J2, which contain the smallest number of the analyzed ISs (n = 5), all non-mucoid mutants were predicted to result from an IS insertion. On the contrary, in KP1, which contains ten ISs, only one out of the ten non-mucoid variants resulted from an IS transposition.

Here, we also demonstrated that the simple act of picking one colony rather than another one could lead to different interpretations on the phenotype of bacterial isolates from a clinical sample. Indeed, the colony variants exhibited several distinct phenotypic properties in addition to the capsule production, like biofilm formation, autoaggregation and susceptibility to carbapenems. Those phenotypic were predicted to result from altered capsule production. However, additional mutations in some isolates might have also contributed to the observed effect. Particularly, we observed enhanced biofilm production and autoaggregation in M63/Glu for five out of eight NM variants. Higher levels of autoaggregation are indicative of a change in cell surface [26], which here was the loss of capsule, likely unmasking other surface components contributing to autoaggregation. CNR152A1-NM2 showed the highest increase of biofilm formation and autoaggregation, as deduced from the sedimentation rate among the eight strains analyzed (< 24 h), suggesting properties impacting on cell clumping. In-depth analysis of CNR152A1 genome compared to isolates from the same STs retrieved from the National Center for Biotechnology (NCBI) revealed an IS903b at codon 264 disrupting wbbM, belonging to the antigen O biosynthesis gene cluster. It encodes a glycosyltransferase and its disruption has been shown to induce defects in LPS biosynthesis [37], increasing the electronegative charge of the bacterial cell surface. The IS insertion was also present in the CNR152A1-NM2 and in the other NM variants included in our analysis. The loss of capsule, combined with the mutation in wbbM, likely caused a dramatic change from a hydrophilic to a hydrophobic bacterial surface, possibly contributing to enhance the autoaggregative and biofilm formation properties. On the other hand, CNR128G5 produces a high level of biofilm on the whole and no significant difference in biofilm production was observed between NM and M variants.

We also observed a variable impact of the NM phenotype on carbapenem susceptibility. In four out of eight isolates, the capsule loss in the NM variant resulted in an increased susceptibility to meropenem, ertapenem and imipenem. This observation suggested a protection of the mucoid-capsulated phenotype under carbapenem pressure in certain strains, possibly contributing to reduced permeability of the outer membrane to these antibiotics. Interestingly, in CNR152A1, we noticed a decrease in susceptibility in the NM2 variant, particularly towards meropenem and ertapenem. This observation went true for all the NM variants of this strain, regardless the mutated gene. Markedly, loss of O-antigen expression is likely to affect the conformation and function of various surface proteins [38]. Deep rough LPS mutants, lacking the complete core region up to the 3-deoxy-d-manno-octulopyranosic acid residues, were shown to be less capable of assisting the folding, insertion, and trimerization of porins [39]. Hence, we hypothesized that the loss of capsule in the eight CNR152A1 NM variants, combined with the defects in the O-antigen, might further disturb the assembly of outer membrane proteins, resulting in a decrease in carbapenem permeability and susceptibility. Alternatively, autoaggregation and hydrophobicity by themselves might contribute to reduce carbapenem susceptibility. On the other hand, it has been reported that capsular defective strains are more susceptible to antimicrobial peptides including polymyxin B [14, 29]. However, we did not observe the same for the eight strains, possibly due to a strain- and mutation-dependent impact of the capsule loss.

Conclusions

Capsule loss is a common event, which can take place within monoclonal populations, generating heterogeneity, and it might have an impact on important phenotypic traits related to host adaptation and antimicrobial susceptibility. Given the phenotypic divergences observed between strains, the technical issues encountered to differentiate M and NM variants and to get an optimal sequencing coverage of the capsule biosynthesis region by using tagmentation for library construction, phenotypic characterization of clinical isolates should be performed carefully, especially when those display a multi-drug resistant phenotype.

Methods

Strains and growth conditions

The clinical CPKp isolates used in this study were from the National Reference Centre laboratory for Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae at the Bicêtre Hospital and are listed in Table 1, together with relevant information: origin, capsular types, ST, antibiotic resistance genes repertoire. K. pneumoniae ATCC CIP 53153 was used as a reference strain. Bacteria were grown in Tryptic-Soy (TS) broth or lysogeny broth (LB) and on TS agar (TSA) or LB agar (LBA) plates. Antibiotic susceptibility testing was performed on Mueller-Hinton Agar (MHA) plates. M63 minimal medium was supplemented with Glucose 0.4% (M63/Glu) to perform biofilm assay. Spent M63/Glu medium used to test autoaggregation was recovered following growth of the same isolate, centrifugation at high speed (11,000 x g) for 10 min and 0.22 μm filtration of the supernatant.

Isolation of non-mucoid variants and frequency of phenotypic variation

The M and NM K. pneumoniae variants (MVs and NMVs) can be observed on LBA although the NMVs were more accurately distinguished on TSA. We noticed that MVs typically give rise to translucent sectors after 24 h of growth at 37 °C. Appearance of NM sectors within M colonies, referred to as phenotypic switch was quantified as follows. A single mucoid colony was resuspended in normal saline to an OD600 of 0.1. One hundred μL of serial dilutions were plated on TSA to get c.a. 100 colonies per plate. After overnight growth, colony aspect (M or NM) was investigated optically by light contrast. The number of mucoid colonies exhibiting non-mucoid sectors was counted after 24, 48 and 72 h of incubation. The frequency of appearance of NMVs was quantified as the ratio between colonies showing NM sectors over the total number of colonies on plate for three independent cultures.

Capsule extraction and quantification

Capsular polysaccharides were extracted and quantified using a colorimetric assay for uronic acid, a component of the K. pneumoniae capsule repeat unit, as described previously [25]. In parallel, serial dilutions of the bacterial culture were plated to determine the number of Colony Forming Units (CFUs). The uronic acid content was expressed in nanograms per 106 CFUs.

Capsule staining and microscopic visualization

Bacterial capsule was visualized by negative staining with the India Ink method, followed by counter-staining of bacterial cells with Crystal Violet as described [25]. Excess of Crystal Violet was washed away using copper sulfate 10% (wt/vol). Images were taken using a Leica DM-4 B microscope with a PL Fluotar 100x/1.32 PH3 immersion objective and photographed using the Hamamatsu ORCA Flash4.0 LT camera and the Leica Application Suite (LasX) software. The resolution was 2048 × 2048 (72 dpi). No downstream processing was made to enhance image resolution as well as any adjustment and/or manipulation.

In vitro biofilm production

The ability of the MVs and NMVs to form biofilm on polystyrene was analyzed using 96-well plates [40]. Briefly, stationary-phase cultures were diluted to OD600 = 0.05 in fresh M63 minimal medium supplemented with 0.4% glucose and 100 μl of this inoculum were grown for 24 h in 96-well polystyrene plates at 37 °C. Biofilm was fixed by using Bouin’s solution (acetic acid 5%, formaldehyde, 9% and picric acid, 0.9% in water) and washed with water once before adding 1% (wt/vol) crystal violet. After 10 min of staining at room temperature, the plates were washed twice with water, dried at room temperature, crystal violet was solubilized by the addition of 200 μL of a solution of ethanol–acetone (80–20) and OD595 was determined. Results correspond to three independent experiments with four-replicates measurements.

Autoaggregation assay

Autoaggregation (i.e., cell clumping and sedimentation) was measured as previously described [41]. Mucoid isolates and their respective NMVs were grown overnight in M63 supplemented with glucose 0.4% and MgSO4 1 mM at 37 °C shaking. After centrifugation at 3000 g for 5 min, bacterial pellets were resuspended in 1 mL of spent M63/Glu minimal medium to get an OD600 ~ 0.3–0.6. The OD600 of the upper layer of the cultures was read after 24 h upon static incubation at room temperature by an Infinite® 200 PRO spectrophotometer. Autoaggregation percentage was expressed as: (1- OD600 upper layer 24 h/OD600 bacterial suspension at time zero) *100.

Curli/cellulase expression

Curli fibers are protease resistant and bind to Congo red (CR) and other amyloid dyes [42]. However, CR binds to other bacterial extracellular features, including cellulose [42]. We therefore assess curli/cellulose production by the Congo red assay. TS agar was supplemented with 40 μg/mL Congo red (Sigma-Aldrich) and 20 μg/mL Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Plates were inoculated with drops of 5 μL of each overnight bacterial culture grown in TSB and incubated for 72 h at 37 °C after which colony morphology and color were inspected and recorded.

Carbapenem and colistin susceptibility assays

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed by E-test (bioMérieux) on Mueller-Hinton (MH) agar for carbapenems, whereas colistin was tested by broth microdilution assay. Experiments were performed in triplicates. Results were interpreted according to EUCAST guidelines, as updated in 2018 (http://www.eucast.org).

Whole genome sequencing, genome assembly and variant characterization

Genomic DNA was extracted on exponentially growing K. pneumoniae (OD600 = 0.4–0.6) using the Qiagen Blood and Tissue DNeasy kit according to manufacturer’s recommendations. Libraries were prepared following manufacturers’ instructions by using the Illumina Flex kit based on Tn5 transposase tagmentation and the NEBNext Ultra II FS DNA Library prep kit based on random enzymatic fragmentation of genomic DNA. Whole genome sequencing was performed on Illumina NexSeq500 or HiSeq2500 platform. SPAdes [43] was used for de novo assembly and genome annotation was completed using RAST [44]. Resistome, virulome and ST were determined using Kleborate (https://github.com/katholt/Kleborate). SNPs, IS insertion and recombination events were detected by using breseq [45] using as reference contigs of the M variant and in-house scripts based on BWA [46] and GATK [47, 48]. Mutations were visually verified by using the IGV viewer [49]. IS sequences were identified in the draft genome sequences of the eight strains by BLASTN to identify IS – chromosome junctions. IS sequences were retrieved and analyzed by using the ISfinder database [50].

Statistical analysis

R version 3.6.1 (http://www.rstudio.com/) was used to construct graphs and analyze data regarding phenotypic switch frequencies, capsule quantification, carbapenem susceptibility, biofilm formation and autoaggregation. Groups were compared using unpaired t-test. P values of < 0.0001 ****, < 0.001 ***, < 0.01 ** and < 0.05 * were considered significant.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Rafael Patiño-Navarrete for his help in the bioinformatics analysis.

Abbreviations

- CPKp

Carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharides

- CPS

Polysaccharidic capsule

- K-type

Capsular-type

- CC

Clonal complex

- M

Mucoid

- NM

Non-mucoid

- IS

Insertion sequence

- WGS

Whole genome sequencing

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- nt

Nucleotide

- TSB

Tryptic-soy broth

- LB

Lysogeny broth

- CFUs

Colony forming units

- wt/vol

Weight/volume

Authors’ contributions

AC, NC, PDZ performed experiments; TN and RB collected and provided the samples for the study; AC, PG, NC, PDZ, TN and IRC analyzed the data; AC and PG designed the study; AC, IRC, RB and PG wrote the manuscript; all authors approved the manuscript prior to submission.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the French National Research Agency (ANR-10-LABX-62-IBEID and ANR-10-LABX-33), and from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program under Grant Agreement No. 773830 (Project MedVetKlebs, One Health EJP). Adriana Chiarelli is part of the Pasteur - Paris University (PPU) International PhD Program. This project has received funding from the Institut Carnot Pasteur Microbes & Santé, and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No 665807.

Availability of data and materials

Fastq files were deposited at the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) with the BioProject accession number PRJNA613777. Sequence accession numbers of the eight strains are indicated in Table 1.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. The eight strains are from laboratory collections without information on patient.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rémy A. Bonnin and Philippe Glaser contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Wyres KL, Holt KE. Klebsiella pneumoniae as a key trafficker of drug resistance genes from environmental to clinically important bacteria. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2018;45:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2018.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Podschun R, Ullmann U. Klebsiella spp. as nosocomial pathogens: epidemiology, taxonomy, typing methods, and pathogenicity factors. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11(4):589–603. doi: 10.1128/CMR.11.4.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.David S, Reuter S, Harris SR, Glasner C, Feltwell T, Argimon S, Abudahab K, Goater R, Giani T, Errico G, et al. Epidemic of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in Europe is driven by nosocomial spread. Nat Microbiol. 2019;4(11):1919–1929. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0492-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petrosillo N, Taglietti F, Granata G. Treatment options for colistin resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae: present and future. J Clin Med. 2019;8(7):934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Tacconelli E, Carrara E, Savoldi A, Harbarth S, Mendelson M, Monnet DL, Pulcini C, Kahlmeter G, Kluytmans J, Carmeli Y, et al. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: the WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(3):318–327. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30753-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feldman MF, Mayer Bridwell AE, Scott NE, Vinogradov E, McKee SR, Chavez SM, Twentyman J, Stallings CL, Rosen DA, Harding CM. A promising bioconjugate vaccine against hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116(37):18655–18663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1907833116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kabha K, Nissimov L, Athamna A, Keisari Y, Parolis H, Parolis LA, Grue RM, Schlepper-Schafer J, Ezekowitz AR, Ohman DE, et al. Relationships among capsular structure, phagocytosis, and mouse virulence in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 1995;63(3):847–852. doi: 10.1128/IAI.63.3.847-852.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paczosa MK, Mecsas J. Klebsiella pneumoniae: going on the offense with a strong defense. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2016;80(3):629–661. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00078-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clements A, Gaboriaud F, Duval JF, Farn JL, Jenney AW, Lithgow T, Wijburg OL, Hartland EL, Strugnell RA. The major surface-associated saccharides of Klebsiella pneumoniae contribute to host cell association. PLoS One. 2008;3(11):e3817. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moranta D, Regueiro V, March C, Llobet E, Margareto J, Larrarte E, Garmendia J, Bengoechea JA. Klebsiella pneumoniae capsule polysaccharide impedes the expression of beta-defensins by airway epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 2010;78(3):1135–1146. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00940-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wyres KL, Wick RR, Gorrie C, Jenney A, Follador R, Thomson NR, Holt KE. Identification of Klebsiella capsule synthesis loci from whole genome data. Microbial genomics. 2016;2(12):e000102. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wyres KL, Gorrie C, Edwards DJ, Wertheim HF, Hsu LY, Van Kinh N, Zadoks R, Baker S, Holt KE. Extensive capsule locus variation and large-scale genomic recombination within the Klebsiella pneumoniae clonal group 258. Genome Biol Evol. 2015;7(5):1267–1279. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evv062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin CL, Chen FH, Huang LY, Chang JC, Chen JH, Tsai YK, Chang FY, Lin JC, Siu LK. Effect in virulence of switching conserved homologous capsular polysaccharide genes from Klebsiella pneumoniae serotype K1 into K20. Virulence. 2017;8(5):487–493. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2016.1228508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pal S, Verma J, Mallick S, Rastogi SK, Kumar A, Ghosh AS. Absence of the glycosyltransferase WcaJ in Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC13883 affects biofilm formation, increases polymyxin resistance and reduces murine macrophage activation. Microbiology. 2019;165(8):891–904. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dorman MJ, Feltwell T, Goulding DA, Parkhill J, Short FL. The capsule regulatory network of Klebsiella pneumoniae defined by density-TraDISort. mBio. 2018;9(6):e01863–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Lee H, Shin J, Chung YJ, Baek JY, Chung DR, Peck KR, Song JH, Ko KS. Evolution of Klebsiella pneumoniae with mucoid and non-mucoid type colonies within a single patient. Int J Med Microbiol. 2019;309(3–4):194–198. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2019.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ernst CM, Braxton JR, Rodriguez-Osorio CA, Zagieboylo AP, Li L, Pironti A, Manson AL, Nair AV, Benson M, Cummins K, et al. Adaptive evolution of virulence and persistence in carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Nat Med. 2020;26(5):705–711. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0825-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tipton KA, Dimitrova D, Rather PN. Phase-variable control of multiple phenotypes in Acinetobacter baumannii strain AB5075. J Bacteriol. 2015;197(15):2593–2599. doi: 10.1128/JB.00188-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bailey MJ, Hughes C, Koronakis V. RfaH and the ops element, components of a novel system controlling bacterial transcription elongation. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26(5):845–851. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.6432014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tato M, Coque TM, Ruiz-Garbajosa P, Pintado V, Cobo J, Sader HS, Jones RN, Baquero F, Canton R. Complex clonal and plasmid epidemiology in the first outbreak of Enterobacteriaceae infection involving VIM-1 metallo-beta-lactamase in Spain: toward endemicity? Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(9):1171–1178. doi: 10.1086/522288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Monteiro J, Santos AF, Asensi MD, Peirano G, Gales AC. First report of KPC-2-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae strains in Brazil. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53(1):333–334. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00736-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wyres KL, Nguyen TNT, Lam MMC, Judd LM, van Vinh CN, Dance DAB, Ip M, Karkey A, Ling CL, Miliya T, et al. Genomic surveillance for hypervirulence and multi-drug resistance in invasive Klebsiella pneumoniae from south and Southeast Asia. Genome Med. 2020;12(1):11. doi: 10.1186/s13073-019-0706-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stevenson G, Andrianopoulos K, Hobbs M, Reeves PR. Organization of the Escherichia coli K-12 gene cluster responsible for production of the extracellular polysaccharide colanic acid. J Bacteriol. 1996;178(16):4885–4893. doi: 10.1128/JB.178.16.4885-4893.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cai R, Wang G, Le S, Wu M, Cheng M, Guo Z, Ji Y, Xi H, Zhao C, Wang X, et al. Three capsular polysaccharide synthesis-related Glucosyltransferases, GT-1, GT-2 and WcaJ, are associated with virulence and phage sensitivity of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Domenico P, Schwartz S, Cunha BA. Reduction of capsular polysaccharide production in Klebsiella pneumoniae by sodium salicylate. Infect Immun. 1989;57(12):3778–3782. doi: 10.1128/IAI.57.12.3778-3782.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trunk T, Khalil HS, Leo JC. Bacterial autoaggregation. AIMS Microbiol. 2018;4(1):140–164. doi: 10.3934/microbiol.2018.1.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davey ME, Duncan MJ. Enhanced biofilm formation and loss of capsule synthesis: deletion of a putative glycosyltransferase in Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Bacteriol. 2006;188(15):5510–5523. doi: 10.1128/JB.01685-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schembri MA, Blom J, Krogfelt KA, Klemm P. Capsule and fimbria interaction in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 2005;73(8):4626–4633. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.8.4626-4633.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Campos MA, Vargas MA, Regueiro V, Llompart CM, Alberti S, Bengoechea JA. Capsule polysaccharide mediates bacterial resistance to antimicrobial peptides. Infect Immun. 2004;72(12):7107–7114. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.12.7107-7114.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phillips ZN, Tram G, Seib KL, Atack JM. Phase-variable bacterial loci: how bacteria gamble to maximise fitness in changing environments. Biochem Soc Trans. 2019;47(4):1131–1141. doi: 10.1042/BST20180633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahmad I, Karah N, Nadeem A, Wai SN, Uhlin BE. Analysis of colony phase variation switch in Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates. PLoS One. 2019;14(1):e0210082. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matatov R, Goldhar J, Skutelsky E, Sechter I, Perry R, Podschun R, Sahly H, Thankavel K, Abraham SN, Ofek I. Inability of encapsulated Klebsiella pneumoniae to assemble functional type 1 fimbriae on their surface. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;179(1):123–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb08717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wugeditsch T, Paiment A, Hocking J, Drummelsmith J, Forrester C, Whitfield C. Phosphorylation of Wzc, a tyrosine autokinase, is essential for assembly of group 1 capsular polysaccharides in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(4):2361–2371. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009092200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bushell SR, Mainprize IL, Wear MA, Lou H, Whitfield C, Naismith JH. Wzi is an outer membrane lectin that underpins group 1 capsule assembly in Escherichia coli. Structure. 2013;21(5):844–853. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rahn A, Whitfield C. Transcriptional organization and regulation of the Escherichia coli K30 group 1 capsule biosynthesis (cps) gene cluster. Mol Microbiol. 2003;47(4):1045–1060. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Foster PL. Stress-induced mutagenesis in bacteria. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;42(5):373–397. doi: 10.1080/10409230701648494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kelly SD, Clarke BR, Ovchinnikova OG, Sweeney RP, Williamson ML, Lowary TL, Whitfield C. Klebsiella pneumoniae O1 and O2ac antigens provide prototypes for an unusual strategy for polysaccharide antigen diversification. J Biol Chem. 2019;294(28):10863–10876. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.008969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klein G, Raina S. Regulated assembly of LPS, its structural alterations and cellular response to LPS defects. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(2):356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Bolla JM, Lazdunski C, Pages JM. The assembly of the major outer membrane protein OmpF of Escherichia coli depends on lipid synthesis. EMBO J. 1988;7(11):3595–3599. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03237.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O'Toole GA, Kolter R. Initiation of biofilm formation in Pseudomonas fluorescens WCS365 proceeds via multiple, convergent signalling pathways: a genetic analysis. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28(3):449–461. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fagan RP, Smith SG. The Hek outer membrane protein of Escherichia coli is an auto-aggregating adhesin and invasin. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2007;269(2):248–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reichhardt C, McCrate OA, Zhou X, Lee J, Thongsomboon W, Cegelski L. Influence of the amyloid dye Congo red on curli, cellulose, and the extracellular matrix in E. coli during growth and matrix purification. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2016;408(27):7709–7717. doi: 10.1007/s00216-016-9868-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, Kulikov AS, Lesin VM, Nikolenko SI, Pham S, Prjibelski AD, et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol. 2012;19(5):455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aziz RK, Bartels D, Best AA, DeJongh M, Disz T, Edwards RA, Formsma K, Gerdes S, Glass EM, Kubal M, et al. The RAST server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Deatherage DE, Barrick JE. Identification of mutations in laboratory-evolved microbes from next-generation sequencing data using breseq. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1151:165–188. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-0554-6_12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Langmead B: Aligning short sequencing reads with Bowtie. Current protocols in bioinformatics 2010, Chapter 11:Unit 11.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, Sivachenko A, Cibulskis K, Kernytsky A, Garimella K, Altshuler D, Gabriel S, Daly M, et al. The genome analysis toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20(9):1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patino-Navarrete R, Rosinski-Chupin I, Cabanel N, Gauthier L, Takissian J, Madec JY, Hamze M, Bonnin RA, Naas T, Glaser P. Stepwise evolution and convergent recombination underlie the global dissemination of carbapenemase-producing Escherichia coli. Genome Med. 2020;12(1):10. doi: 10.1186/s13073-019-0699-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdottir H, Winckler W, Guttman M, Lander ES, Getz G, Mesirov JP. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(1):24–26. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Siguier P, Perochon J, Lestrade L, Mahillon J, Chandler M. ISfinder: the reference Centre for bacterial insertion sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(Database issue):D32–D36. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Fastq files were deposited at the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) with the BioProject accession number PRJNA613777. Sequence accession numbers of the eight strains are indicated in Table 1.