Abstract

Exploding head syndrome (EHS) is an under-recognized parasomnia characterized by a complaint of sudden loud noise or a sense of explosion in the head that usually occurs at sleep onset. This paper is a report of 6 patients diagnosed with EHS through a structured clinical interview and video-polysomnography (vPSG) recordings. We also reviewed the available literature that addressed the presentation and clinical and PSG characteristics of EHS. The case series included 4 men and 2 women of a mean age of 44.2 years (between 13 and 77 years). Their episodes were variable in expression, between a sudden firecracker-like explosion to a gun-shot sound, mostly as if happening inside the head. EHS is always associated with distress but never with pain. Five out of 6 patients had other sleep-related problems with a close relationship of EHS symptoms to comorbid sleep disorder manifestations and exacerbations. The vPSG recordings of 5 patients were unremarkable. An attack of EHS was documented in 1 patient, arising during stage N2 of sleep. Three patients responded well to reassurance and treatment for the comorbid sleep disorder. The other 3 patients responded well to amitriptyline (10–50 mg). EHS is a well-characterized, underrecognized hypnic parasomnia with a benign course. Amitriptyline seems to be effective in persistent cases.

Keywords: Headache, Sleep, Arousal, Seizure, Narcolepsy, Restless legs syndrome

Introduction

A prognostically benign, distressing, and frightening clinical entity known as exploding head syndrome (EHS) was given its provocative name by J.M.S. Pearce in 1988 [1]. Recently, as opposed to this more dramatic and auditory-focused term “EHS,” “episodic cranial sensory shock” has been suggested to describe the condition; but EHS is still commonly used [2].

It is described as a perception of loud noises when falling asleep or awakening [3]. These noises are sudden in onset, typically of very brief duration, and quite distressing to the sufferer. The noises are usually without any pain; however, EHS episodes result in a great deal of fear, confusion, and distress. The experience is typically infrequent but can manifest in more chronic forms, thus resulting in clinical consequences.

Despite its fascinating nature and frightening name, relatively little is known about EHS. Several sleep medicine textbooks either omit it altogether or only make a brief and cursory mention of its core features. Unarguably, EHS is infrequently assessed in both practice and research as a disparate and discernible clinical entity; this lack of attention may result in misdiagnosis, unnecessary testing, and continued agony for patients. Therefore, we report a case series of 6 patients with EHS to present our clinical experience and attempt to delve into the available literature to enhance the understanding of EHS.

Methods

One of the authors interviewed all patients and their bed partners, and 5 of them underwent video polysomnography (vPSG) at the University Sleep Disorders Center, King Saud University, Riyadh. EHS was diagnosed according to the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD-3) [3]. The diagnostic criteria include a complaint of sudden loud noise or a sense of explosion in the head either at sleep onset or waking; the event is followed by abrupt arousal with a sense of fear but no significant pain [3]. Additionally, all other reported sleep disorders were diagnosed according to the ICSD-3. The ethics committee approved this report at King Saud University, and informed consent was obtained from all patients. All subjects (or their parents) have given their written informed consent to publish their cases.

Case Reports

Patients' details are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic data, characteristics of the symptoms, Polysomnographic findings, and comorbid conditions of the 6 new exploding head syndrome patients

| Variable | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | Patient 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 46 | 46 | 13 | 38 | 77 | 45 |

| Sex | Female | Male | Male | Male | Male | Female |

| BMI | 32 | 25 | 26 | 31 | 36 | 26 |

| Duration of symptoms, years | 2 | >10 | 2 | 8 | >30 | >5 |

| Frequency | >1/week | 1–2/month | 1–3/month | 7–8/month | 3–4/month | 1–2/month |

| Type of sound | Loud bang | Something hitting tin roof | Snapping sound | Loud pistol shot | Jet sound | Banging of door |

| Timing | Sleep onset | Sleep onset | Sleep onset | Variable | Sleep onset | Sleep onset |

| Exacerbating factors | None | Sleep deprivation | None | Sleep deprivation | None | Sleep deprivation |

| Comorbid sleep disorders | None | Insomnia | None | Narcolepsy type 2, mild OSA, | REM-related OSA | Restless legs syndrome |

| Other parasomnias | None | None | Somniloquy, somnambulism | Somnambulism, bruxism, sleep-related eating disorder | Hypnic jerks | Hypnic jerks |

| Relation to the sleeping position | Supine | Supine | None | None | Supine | Prone |

| vPSG | Unremarkable | Unremarkable | N3 arousals | Mild OSA N2 arousal | REM-related OSA | Refused by the patient |

| Management | Amitriptyline 50 mg | Education/sleep hygiene | Education/sleep hygiene | Amitriptyline 10 mg | Amitriptyline 10 mg | Education/sleep hygiene |

Case 1

The first patient was a 46-year-old female known to have multiple sclerosis for more than 15 years. During her follow-up, she developed a new symptom of abnormal sound, as if emanating from the inside of her head, which woke her up from sleep with fear and distress. She described the sound as a loud bang, and the experience was distressing to the extent that she had persistent fear of going back to sleep. Symptoms usually occurred more than once a week, at the beginning of sleep and typically at the transition from wakefulness to sleep. She learned to mitigate the symptoms by avoiding the supine sleeping position. The symptoms were initially attributed to stress by her treating physician. She denied any history of other sleep-related symptoms. She continued to suffer from these symptoms for 2 years before being referred to the sleep medicine clinic. The diagnosis of EHS was made through a structured interview, and the vPSG was unremarkable. She was educated about the nature of the problem and was given instructions on sleep hygiene techniques. Subsequently, she was started on amitriptyline 10 mg, which was gradually increased to 50 mg (30 min before bedtime) according to the response. The patient reported complete remission of symptoms at this dose and continues to be in remission to date.

Case 2

A 46-year-old male presented to the sleep medicine clinic with a 12-year history of sleep-onset insomnia. The patient also complained of symptoms suggestive of EHS, which he described as “something hitting a tin roof” inside his head, though initially, he would look around to check the surroundings to look for the source of the sound. His episodes always occurred at the beginning of sleep. The frequency of the episodes was 1–2/month, related to the supine sleeping position, and the exacerbations were closely related to the insomnia symptoms. The patient had an irregular sleep pattern and poor sleep hygiene, which was closely related to the symptom paradigm. His vPSG was unremarkable. The clinical condition was explained to the patient, and he was educated about sleep hygiene. By following sleep hygiene and cognitive behavioral therapy rules, he experienced improvement of all sleep-related symptoms, i.e., insomnia and EHS. The patient did not need any pharmacological therapy on follow-up. He has been in remission for the last 3 years.

Case 3

A 13-year-old boy with an unremarkable medical history, except for a febrile seizure at the age of 2 years, presented with somniloquy. It was first noticed at the age of 10 years; it was followed by somnambulism and symptoms suggestive of EHS. The frequency of somniloquy was almost daily, and that of somnambulism was once a week. EHS symptoms would occur 2–3 times a month without any co-relation with the sleeping position. He described his symptoms as a snapping sound inside his head, immediately after sleep onset, never more than 1 episode per night. He had poor sleep hygiene with excessive use of electronic gadgets around bedtime and in bed. The vPSG showed frequent arousals during stage N3; however, no movement or abnormal respiratory events could be documented. After multiple sessions with the sleep behavior educator, all symptoms improved, though he continues to have somniloquy occasionally. The EHS symptoms have been in remission for 2 years now.

Case 4

A 38-year-old man was under treatment in the psychiatry clinic for generalized anxiety disorder and manic depressive disorder. For that, he was on vortioxetine 50 mg and clonazepam 1 mg. He had multiple sleep-related complaints and was referred by his psychiatrist to the sleep medicine service. He had excessive daytime sleepiness for 5 years with an Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) score of 21/24. The patient disclosed the presence of multiple other sleep-related symptoms: somniloquy since adolescence, somnambulism since adolescence, sleep-related eating disorder, and bruxism since his late twenties. He also complained of dysphoric and well-remembered dreams (nightmares) that caused awakenings. The patient also had a history of snoring and choking without witnessed apnea. His BMI was 31 kg/m2.

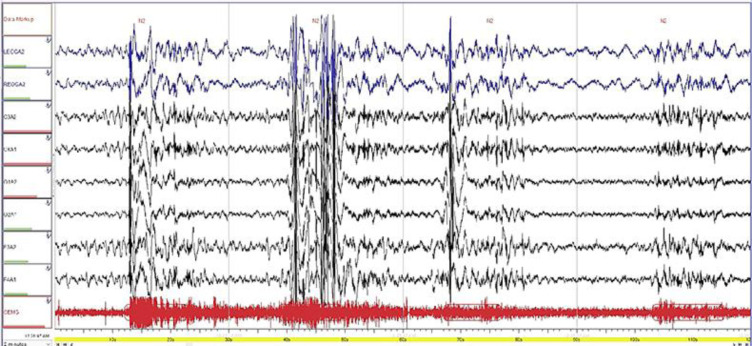

The patient also had symptoms of EHS, which he described as “pistol shot”, for 4 years with a frequency of 1–2 times/week. The vPSG revealed mild obstructive sleep apnea and apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) of 7.5/h without significant desaturation. However, during the PSG, N2 arousal was seen followed by awakening, and it corresponded to an EHS episode experienced by the patient (Fig. 1). The patient complained of irresistible attacks of sleep and hypnogogic and hypnopompic hallucinations. However, he denied cataplexy. The multiple sleep latency test (MSLT) revealed an average sleep latency of 1 min and 6 s and 3 episodes of sleep onset REM (SOREM).

Fig. 1.

A zoomed 2-min Epoch consisting of the parameters of sleep staging (EEG, EOG, and chin EMG) showing stage N2. The EEG was associated with an increase in chin EMG. EEG, electroencephalogram; EOG, electrooculogram; EMG, electromyogram.

The patient was diagnosed to have type 2 narcolepsy and was started on modafinil. He was also started on continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP); however, EHS symptoms did not improve on CPAP therapy. Therefore, the patient was started on amitriptyline 10 mg, 30 min before bedtime. With amitriptyline, the patient had remission of EHS symptoms, but other parasomnias showed only minimal improvement.

This patient is a unique clinical experience, never reported before; a patient of narcolepsy with overlap parasomnia syndrome, namely NREM parasomnia (somnambulism, somniloquy, and sleep-related eating disorder) and REM parasomnia (nightmares) with EHS, subsumed as “other parasomnias.”

Case 5

A 77-year-old man with diabetes and hypertension presented to the sleep disorders clinic with snoring and excessive daytime sleepiness with an ESS score of 12/24 and no nocturnal choking or witnessed apnea. EHS symptoms had been present for the last 30 years, always attributed to stress by his treating doctors. The patient described a sound like a flying jet inside his head at sleep onset that caused awakening and distress but never pain. The frequency of events was 3–4 times/month. Episodes were generally more frequent in the supine sleeping position.

The vPSG showed AHI (NREM/REM) of 13 (8/33). No other abnormal events could be documented; however, he refused to use CPAP. He continued to have the symptoms despite applying the sleep hygiene rules; therefore, he was prescribed 10 mg amitriptyline 30 min before bedtime. He showed good response to therapy, and the frequency of attacks decreased to less than 1 episode every 2 months on the first follow-up and complete remission on subsequent follow-ups.

Case 6

A 45-year-old woman presented to the sleep disorders clinic with symptoms of restless legs syndrome (RLS). She also reported symptoms of EHS. The frequency of EHS events was 2–3 times/month, manifesting as the sound of “banging of a door.” Episodes occurred at the initiation of sleep and almost always in the prone position. The patient refused PSG, as she could not sleep in unfamiliar surroundings. During the interview, her long history of menorrhagia came forth. The further work-up revealed hypochromic-microcytic anemia with low iron stores and low serum ferritin (5 μg/L). The patient was referred to the gynecology service to manage menorrhagia; she was put on oral iron and gabapentin (200 mg). After normalizing the serum ferritin level (76 μg/L), both RLS and EHS symptoms improved. The frequency of EHS decreased to less than 1 episode/month. Later, gabapentin was stopped (after 6 months) and she continues to be in remission for both symptom paradigms.

Discussion

The current report has unique features, including EHS in a patient with narcolepsy, which, to our knowledge, has not been reported before. Additionally, in the patient with RLS and low iron stores, EHS symptoms improved with the correction of ferritin levels.

EHS, being a parasomnia, is abnormal behavior that occurs during sleep. Human physiological consciousness states consist of waking consciousness, NREM sleep, and REM sleep; thus, parasomnias may occur during NREM, REM, or during transitions to and from sleep [3]. In the classification of parasomnias, EHS finds its place under “other parasomnias” due to its relative ambiguity [3].

Parasomnias (para denotes “next to,” and somnus denotes “sleep”) include a collection of the most puzzling, interesting, and unusual behavioral disorders that arise during sleep, which are distinguished by sleep-related acute, abnormal behavioral or physiological actions. The International Classification of Sleep Disorders, Third Edition (ICSD-3), describes parasomnias as unwanted physical events or incidents that arise during entrance into sleep, within sleep, or during arousal from sleep [3]. Parasomnias are classified into NREM parasomnias, such as confusional arousal, sleep terror, sleepwalking, and sleep-related eating disorder; and REM parasomnias, including REM sleep behavior disorder, recurrent isolated sleep paralysis, and nightmare disorder [3].

The prevalence of EHS is difficult to ascertain as the literature is scarce and mostly based on small case series and case reports. Nevertheless, during the validation study on “Munich parasomnia screening,” the prevalence was estimated to be 13.8% in psychiatric patients, 10.0% in patients with sleep disorders, and 10.7% in healthy controls when screened for EHS symptoms on a self-report measure [4]. Similarly, a self-reported internet-based study on 108 participants reported a lifetime rate of 50.0%, although the author of the study is skeptical about the result due to ambiguities in the phrasing of questions [5]. Nonetheless, it belittles the concept of rarity of EHS as it is presumed that patients with EHS rarely seek medical attention solely for the symptoms of this syndrome [1], which is duly replicated in our series where 5 out of 6 patients sought sleep medicine consultation for complaints other than EHS. Besides, patients find it difficult to phrase a complaint due to the ambiguity of symptoms.

Prevalence of EHS in most of the series shows a female predominance (female-to-male ratio of 1.6:1) [3, 4, 6], which is not the case in our case series. In our series, the male-to-female ratio is 2:1, probably reflecting cultural differences in seeking medical advice.

Symptomatology of EHS is variable, ranging from purely auditory to discreetly visual, although the auditory phenomenon is dominant and overwhelming [6]. It is imperative to note that the experience of significant pain is one of the features enabling the elimination of the diagnosis of EHS [1, 3, 6]. This cardinal feature of an absence of pain was seen in all patients of our series. Although in some instances, complaints of mild pain during EHS have been reported, this perception of pain is considered a misperception of shock and fear; nevertheless, mild pain is occasionally reported [6].

The type of sound and its intensity are variable but always unpleasant and distressing, usually expressed through vivid analogy, such as buzz, pistol shot, Christmas cracker, door slam, electric short circuit, etc. [6]. The perception of the sound is commonly bilateral, and the location is variable. It is perceived mostly within the head but sometimes in the ears. In our series, sounds were mainly perceived within the head [6].

The relation between EHS and sleep position was variable in one series, and EHS episodes occurred most commonly in the supine (47%) as opposed to the prone (17%) or lateral recumbent (30%) positions [7]. In our series, the attacks predominantly occurred in the supine position with 4 out of 6 patients having symptoms mostly in the supine position. Clinically, these results may imply a recommendation for EHS patients to avoid sleeping on their backs [6, 7]. The timing of the episodes shows wake/sleep transition predominance over sleep/wake transition, which is duly replicated in our series, with a ratio of 5:1. The appearance of symptoms at sleep onset may imply that EHS is more likely to occur with attempts to inhibit auditory neurons as opposed to wakeful activation. As most episodes occur at sleep onset, this parasomnia can be considered as a “hypnic parasomnia.”

Besides paradigmatic sounds, many patients have visual disturbances during EHS. Some patients perceive lightning or more generic light flashes, whereas others describe visual static. Feelings of intense heat and epigastric and precordial sensations are not uncommon [6]. An aura of electrical sensations that ascends from the lower torso to the head (and immediately precedes the sensory explosions) has also been reported [6, 7].

The relevance of PSG in EHS is for research purposes only; it is not a requirement for the diagnosis. The PSG is often unremarkable in the cases of isolated EHS, probably due to the sparse frequency of the episodes. Although most patients reported EHS attacks after sleep onset, current electroencephalogram (EEG) data used to capture the attacks revealed a predominance of alpha activity along with short episodes of theta, suggesting that the attacks occur during wakefulness [6]. This supports the theory that EHS is due to abnormal activity of neurons in the brainstem involved in sleep initiation [6]. Nevertheless, EHS attacks may occur during stage N2, as in 1 of the patients from the current report [3].

Studies that assessed the EEG recordings of patients with EHS reported no evidence of epileptiform activity [6]. The lack of recorded cortical EEG epileptiform activity does not invariably rule out the possibility of an epileptic basis for EHS, as a subcortical epileptiform activity may occur without any recordable cortical activity.

Pathophysiology

The exact pathophysiology of EHS is unknown; however, multiple theories have been proposed. First, a variety of ear dysfunctions, such as sudden perturbations of middle ear components or the Eustachian tube [6], labyrinthine membrane ruptures [8], and perilymph fistulas, have been suggested [8]. Second, a brief temporal lobe complex partial seizure has been proposed [9]. Third, withdrawal of medications, such as EHS benzodiazepines and selective serotonin, has been suggested [9]. Fourth, and most recently, it has been suggested that EHS may occur because of transient calcium channel dysfunction [9, 10]. Finally, the most popular one of the EHS pathophysiology theories is based upon brainstem neuronal dysfunction during the transition from wakefulness to sleep [7, 11]. Specifically, during this transition, various areas of the brainstem and reticular formation reduce their activity, which normally results in switching off of various parts of the cerebral hemispheres (e.g., motor, visual, and auditory). However, delays in this general switch-off are thought to occur during EHS, resulting in a prominent burst of neuronal activity perceived as deafening sounds, light flashes, and possibly even myoclonus [6].

There are no known precipitating factors for EHS. Denis et al. [12] reported that anxiety, depression, and stress did not predict EHS in multiple logistic regression models among 2 samples. However, the same group reported that insomnia symptoms were associated with EHS in a multiple predictor model [12]. Nevertheless, a more recent study reported that poor sleep quality did not significantly predict EHS [13].

Differential Diagnosis

Even though EHS may not be that rare, most physicians are not familiar with the disorder, which results in underdiagnosis and undertreatment. Medical conditions that may mimic EHS include “idiopathic stabbing headache,” which is a benign headache characterized by brief stabs of pain on the side of the head. However, this headache is more common during wakefulness, although it has been reported at sleep onset [3]. “Hypnic headache syndrome” is another disorder of older people that may also mimic EHS. However, this headache usually occurs 4–6 h after sleep onset, lasts for 30–60 min, and is frequently diffuse or bilateral accompanied by nausea but no autonomic symptoms [3]. Sleep-related headaches, such as migraines, cluster headaches, and nocturnal paroxysmal hemicrania (a severe unbearable unilateral headache usually affecting the region around the eye), may be confused with EHS. However, these disorders are painful, unlike EHS, which is usually painless. Patients with migraine, cluster headache, and hypnic headache usually wake up with an acute bout more frequently during REM sleep than during other stages of sleep, while patients with cluster headache and chronic paroxysmal hemicrania may suffer the bout around the same time of the night almost every night [14].

Simple partial seizures may present with sensory manifestations (may cause alterations to a patient's hearing, vision, or sense of smell), but they do not usually arise at sleep onset. Nocturnal panic attacks may be similar to EHS attacks; however, these are not accompanied by some of the features of EHS, such as a sense of explosion or noise.

Two recent reports demonstrated that sleep paralysis, hypnagogic hallucinations, action-related sleep disorders (sleep-related groaning, sleep-related eating, sleep talking, confusional arousals, and nocturnal eating), and nightmares were associated with the presence of EHS [12, 13]. Therefore, EHS is probably related to some parasomnias and should be entertained in the differential diagnosis, in case of the existence of other abnormal sleep events or disorders, such as sleep paralysis, nightmares, insomnia, and hypnagogic hallucinations.

Treatment

So far, there are no clinical trials available in the literature for the treatment of EHS; the only available evidence is in case reports, case series, and clinical experiences. Since it is a benign condition, pharmacological intervention is often not needed; in many instances, education, sleep hygiene, and assurance result in improvement. Besides, the treatment regimen for any comorbid sleep disorder, such as obstructive sleep apnea, has been reported to induce remission [6, 15]. In our series, 3 out of 6 patients responded well to education, reassurance, and sleep hygiene. However, some subjects may be so distressed by their symptoms that they try to avoid sleep. The following medications have been anecdotally used to treat EHS with success: tricyclic antidepressant clomipramine (50 mg/day taken at night) and amitriptyline (10–50 mg at night), and calcium channel blockers, specifically flunarizine (10 mg/day) and slow-release nifedipine (90 mg/day) [6]. Anticonvulsants have also been prescribed. Topiramate (200 mg/day) [10] did not induce remission of EHS but reduced the intensity of auditory sounds from loud bangs to much softer buzzing sounds [10]. Carbamazepine (200–400 mg/day prescribed 15 min before bedtime) has been used in 3 cases with positive results [16]. Since it is invariably associated with distress, benzodiazepines like clonazepam and clobazam have also been shown to be effective. In our series, 3 patients received amitriptyline, with doses ranging from 10–50 mg. Two out of these 3 patients had complete remission on long-term follow-up, and 1 patient reported a marked decrease in the frequency of the episodes.

Conclusion

EHS is not an uncommon sensory parasomnia, but its relatively poor reporting as a primary complaint and under-recognition of the disorder by the treating physicians result in immense suffering among the patients. Further, not much is known about its etiopathogenesis, which is fraught with theories, resulting in axiomatic conclusions drawn from scarce literature. Henceforth, we need to look further and deeper into this disorder, besides developing reasonable clinical suspicions from patients' history of sleep onset-related complaints. In most cases, education, sleep hygiene, and assurance result in remission. Amitriptyline seems to be effective in persistent cases.

Statement of Ethics

This report received clearance from the ethics committee at King Saud University, and informed consent was obtained from all the patients. The subjects (or their parents or guardians) have given their written informed consent to publish their case (including publication of images).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by the Strategic Technologies Program of the National Plan for Sciences and Technology and Innovation in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (MED511-02-08). The study sponsors played no role in tailoring the study design, collection of data, analysis or interpretation of data, writing of the manuscript, nor decision to submit the manuscript.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the conception or design of the work; the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data for the work; and drafting the work. They all approved the final draft to be published. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Acknowledgement

We thank the Deanship of Scientific Research and RSSU at King Saud University for their technical support.

References

- 1.Pearce JM. Exploding head syndrome. Lancet. 1988 Jul;2((8605)):270–1. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)92551-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goadsby PJ, Sharpless BA. Exploding head syndrome, snapping of the brain or episodic cranial sensory shock? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016 Nov;87((11)):1259–60. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2015-312617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Academy of Sleep Medicine . International classification of sleep disorders: diagnostic and coding manual. 3rd ed. American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fulda S, Hornyak M, Müller K, Cerny L, Beitinger PA, Wetter TC. Development and validation of the Munich Parasomnia Screening (MUPS) Somnologie (Berl) 2008;12((1)):56–65. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sherwood S. Relationship between childhood hypnagogic, hypnopompic, and sleep experiences, childhood fantasy proneness, and anomalous experiences and beliefs: an exploratory www survey. J Am Soc Psych Res. 1999;93((2)):167–97. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharpless BA. Exploding head syndrome. Sleep Med Rev. 2014 Dec;18((6)):489–93. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharpless BA. Characteristic symptoms and associated features of exploding head syndrome in undergraduates. Cephalalgia: an international journal of headache. 2018;38((3)):595–9. doi: 10.1177/0333102417702128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oswald I, Gordon A. Exploding head. Lancet. 1988 Sep;2((8611)):625–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ganguly G, Mridha B, Khan A, Rison RA. Exploding head syndrome: a case report. Case Rep Neurol. 2013 Jan;5((1)):14–7. doi: 10.1159/000346595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palikh GM, Vaughn BV. Topiramate responsive exploding head syndrome. Journal of clinical sleep medicine. 2010 Aug;6((4)):382–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharpless BA. Exploding head syndrome is common in college students. J Sleep Res. 2015 Aug;24((4)):447–9. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Denis D, Poerio GL, Derveeuw S, Badini I, Gregory AM. Associations between exploding head syndrome and measures of sleep quality and experiences, dissociation, and well-being. Sleep (Basel) 2019 Feb;42((2)) doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsy216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirwan E, Fortune DG. Exploding head syndrome, chronotype, parasomnias and mental health in young adults. J Sleep Res. 2020 Apr;:e13044. doi: 10.1111/jsr.13044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Culebras A. Other Neurologic Disorders. In: Kryger M, Roth T, Dement W, editors. Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2018. pp. 951–8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ceriani CE, Nahas SJ. Exploding Head Syndrome: a Review. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2018 Jul;22((10)):63. doi: 10.1007/s11916-018-0717-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Declerck A, Arends J. An exceptional case of parasomnia: the exploding head syndrome. Sleep-Wake Res Neth. 1994;5:41–3. [Google Scholar]