Abstract

Background and Aims

Only little is known about blood groups other than ABO blood groups and Rhesus factors in Arabian countries and Iran. During the last years, increased migration to Central Europe has put a focus on the question how to guarantee blood supply for patients from these countries, particularly because hemoglobinopathies with the need of regular blood support are more frequent in patients from that region. Therefore, blood group allele frequencies should be determined in individuals from Arabian countries and Iran by molecular typing and compared to a German rare donor panel.

Methods

1,111 samples including 800 individuals from Syria, 147 from Iran, 123 from the Arabian Peninsula, and 41 from Northern African countries were included in a MALDI-TOF MS assay to detect polymorphisms coding for Kk, Fy(a/b), Fy<sub>null</sub>, C<sub>w</sub>, Jk(a/b), Jo(a+/a–), Lu(a/b), Lu(8/14), Ss, Do(a/b), Co(a/b), In(a/b), Js(a/b), Kp(a/b), and variant alleles RHCE*c.697C>G and RHCE *c.733C>G. Yt(a/b), S–s–U–, Vel<sub>null</sub>, Co<sub>null</sub>, and RHCE *c.667G>T were tested by PCR-SSP.

Results

Of the Arabian donors, 2% were homozygous for the FY *02.01N allele (Fy<sub>null</sub>), and 15.7% carried the heterozygous mutation. However, 0.8% of the German donors also carried 1 copy of the allele. 3.6% of all and 29.3% of Northern African donors were heterozygous for the RHCE *c.733C>G substitution, 0.4% of the Syrian probands were heterozygous for DO *01/DO *01.-05, a genotype that was lacking in German donors. Whereas the KEL *02.06 allele coding for the Js(a) phenotype was missing in Germans; 0.8% of the Syrian donors carried 1 copy of this allele. 1.8% of the Syrian but only 0.3% of the German donors were negative for YT *01. One donor from Northern Africa homozygously carried the GYPB *270+5g>t mutation, inducing the S–s–U+<sup>w</sup> phenotype, and in 2 German donors a GYPB *c.161G>A exchange, which induces the Mit+ phenotype, caused a GYPB *03 allele dropout in the MALDI assay. The overall failure rate of the Arabian panel was 0.4%.

Conclusions

Some blood group alleles that are largely lacking in Europeans but had been described in African individuals are present in Arabian populations at a somewhat lower frequency. In single cases, it could be challenging to provide immunized Arabian patients with compatible blood.

Keywords: Arabian donors, Blood groups, Donor screening, PCR, Genotyping, MALDI-TOF MS, Molecular blood group typing

Introduction

The main goal in transfusion medicine is to provide compatible blood products for each patient. Blood supply can be a challenging if the patient has got immunized to high-frequency blood group alloantigens (HFA) [1, 2]. Special national and international rare donor panels and the ISBT working party on rare donors support transfusion specialists to identify donors with rare blood groups [3]. Particularly, if a patient with an alloantibody to HFA belongs to another ethnicity than the major donor population it can be cumbersome to find a compatible donor. During the last years, a higher number of individuals migrated from Arabian countries like Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq, the Maghreb states, and other African countries to Europe. Since 2015, more than 3 million people arrived at the European Union [4], and about 1.68 million refugees applied for asylum in Germany, most of them originating from Syria [5, 6]. The impact of migration on patient-centered care was reported in a longitudinal study over 4 decades [7], and an increase in hemoglobinopathies like thalassemia and sickle cell disease was observed in Europe [8]. Unfortunately, only little is known about frequencies of blood groups other than ABO and Rhesus factors in Arabian countries. Available ABO and Rhesus phenotyping data demonstrate different frequencies even in geographically adjacent regions, which might be explained by the presence of rather closed populations without admixture [9, 10, 11, 12]. For example, a French-Afghan study that applied multiplex PCR and SnapShot typing to different blood group systems in Afghan and Pakistani populations could demonstrate slightly varying allele frequencies for most examined blood groups [13]. An Israeli study showed that the Fynullphenotype on red blood cells, which is caused by the FY *-67t>c promoter mutation, varies between 0% in Ashkenazi and Sephard Jews and 10% in Muslim Arabs [14]. In some sub-Saharan regions, the Fynullphenotype predominates since deficiency in the Fy antigen prevents red blood cells and their precursors from being infected by Plasmodium vivax, an elicitor of Malaria tertiana [15, 16]. Single divergent data were reported on the Kell blood groups K and Jsa[10, 13, 14, 17, 18].

Although single reports on blood group antigen frequencies exist, no comprehensive overview from Syria is available. Thus, we aimed to determine blood group frequencies other than ABO, Rhesus D, C, c, E, or e predominantly in donors from Syria and other Arabian countries. Extensive phenotyping is cumbersome due to the shortage of typing sera, whereas molecular high-throughput typing gained importance during the last years [13, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24]. We and others successfully applied MALDI-TOF MS for blood group screening of our donor population in order to identify rare donors who are negative for special HFA [25, 26, 27]. In the present study, our existing panel was slightly modified and completed by PCR-SSP to type for blood group alleles in donors from Arabian countries and Iran.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Between June 2016 and April 2018, a total of 1,111 blood samples were collected from volunteers originating from Syria, Iran, and further 14 countries in Northern Africa and the Arabian Peninsula (Table 1). In terms of a simplified description, this whole collective is named Arabian panel. Attribution to mother countries was performed due to self declaration. Out of these, 266 were Syrian volunteers that were recruited at social venues for refugees in Rhineland-Palatinate from June 2016 till October 2017. After informed consent had been obtained, they only gave 8 mL of EDTA anticoagulated blood for the study. The remaining 845 donors from different countries presented from July 2017 to April 2018 at regular blood collections of the German Red Cross Blood Service West in North Rhine-Westphalia, Rhineland-Palatinate, and Saarland. There was no preselection concerning ABO blood groups and Rhesus factors. All subjects had given informed consent, and the study on blood group frequencies in Arabian individuals was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Chamber of Rhineland-Palatinate in Mainz, Germany.

Table 1.

Countries of origin of the probands

| Country | Probands, n | Total, n |

|---|---|---|

| Syria | 800 | 800 |

| Iran | 147 | 147 |

| Northern Africa | 41 | |

| Libya | 1 | |

| Morocco | 19 | |

| Tunisia | 7 | |

| Algeria | 5 | |

| Egypt | 9 | |

| Arabian Peninsula | 123 | |

| Saudi Arabia | 4 | |

| Yemen | 2 | |

| Jordan | 7 | |

| Iraq | 49 | |

| United Arab Emirates | 1 | |

| Israel | 6 | |

| Lebanon | 48 | |

| Palestine | 5 | |

| Oman | 1 | |

| German rare donor panel | ||

| Germany | 2,821–20,529 | |

The total number of probands of the German rare donor panel was 20,529, but not each blood group was tested for each donor.

A further 20,529 blood samples from regular repetitive blood donors of the German Red Cross Blood Service West were collected from June 2012 to June 2019. The aim of this continuing, subsequently called German rare donor panel is to identify donors with rare blood groups. The predominant majority of these donors is of Middle European origin, but very few individuals might have another ethnic background. However, blood donors do not regularly define their ethnicity in the donor questionnaire, which aggravates the identification of donors of non-Middle European origin. In the case that no unambiguous origin was available, this was deduced from the donor names. The rare blood group donors were preselected according to blood group O (rarely A, B, or AB), CCD.ee, ccD.EE, ccddee, and K negative.

DNA Isolation

DNA was isolated from EDTA anticoagulated blood either manually by the Gentra Pugene blood kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) or with an automated magnetic bead technology (MSM1; Chemagen, Perkin Elmer, Baesweiler, Germany) according to the manufacturers' instructions. DNA concentration was adjusted to 15–25 ng/µL for the Arabian panel; for the German rare donor panel, it typically was in the range of 20–45 ng/µL without adjustment.

MALDI-TOF MS Genotyping

All samples were typed by in-house MALDI-TOF MS methods. Different multiplex assays were established to screen for regular blood donors within the German rare donor panel and for the study on blood group frequencies in Arabian donors (Table 2). The AgenaCx assay Design Suite V2.0 online tool (Agena Bioscience, Hamburg, Germany) was used as the basis to superplex the already existing German rare donor assay for specific needs for Arabian donors. In both cases, due to economic reasons, the precondition was to include as many SNPs in 1 well as possible, accepting the risk to lose single SNPs in favor for other new SNPs.

Table 2.

Blood group SNPs included in the MALDI-TOF MS assays

| Blood group system | ISBT No. | Blood group | Gene | Allele 1 | Allele 2 | NT 1 | NT 2 | Amino acid exchange | db SNP rs No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assay 1 (German rare donor panel) | |||||||||

| MNS | 002 | M/N | GYPA | GYPA*01 (rf) | GYPA*02 | 71G, 72T | 71A, 72G | Gly24Glu | rs7687256 |

| rs7658293 | |||||||||

| MNS | 002 | S/s | GYPB | GYPB*03 | GYPB* 04 (rf) | 143T | 143C | Met48Thr | rs7683365 |

| Rhesus | 004 | C/Cw | RHCE | RHCE*C | RHCE*Cw | 122A | 122G | Gln41Arg | rs138268848 |

| Lutheran | 005 | Lua/Lub | BCAM | LU*01 | LU*02 (rf) | 230A | 230G | His77Arg | rs28399653 |

| Lutheran | 005 | Lu8/Lu14 | BCAM | LU*02 (rf) | LU02.14 | 611T | 611A | Met204Lys | rs28399656 |

| Kell | 006 | Kpa/Kpb | KEL | KEL*02.03 | KEL*02 (rf) | 841T | 841C | Trp281Arg | rs176059 |

| Duffy | 008 | Fya/Fyb | ACKR1 | FY*01 | FY*02 (rf) | 125G | 125A | Gly42Asp | rs12075 |

| Duffy | 008 | Fyb/Fynull | ACKR1 | FY*02 (rf) | FY*02N.01 | −67t | −67c | Protein | rs2814778 |

| (Promoter) | absent | ||||||||

| on RBC | |||||||||

| Kidd | 009 | Jka/Jkb | SLC14A1 | JK*01 | JK*02 (rf) | 838G | 838A | Asp280Asn | rs1058396 |

| Cartwright | 011 | Yta/Ytb | ACHE | YT*01 (rf) | YT*02 | 1057C | 1057A | His353Asn | rs1799805 |

| Dombrock | 014 | Doa/Dob | ART4 | DO*01 (rf) | DO*02 | 793A | 793G | Asn265Asp | rs11276 |

| Colton | 015 | Coa/Cob | AQP1 | CO*01 (rf) | CO*02.01 | 134C | 134T | Ala45Val | rs28362692 |

| Colton | 015 | Coa/Conull | AQP1 | CO*01 (rf) | CO*01N.06 | 601G | 601delG | Val201stop | rs28362737 |

| Vel | 034 | Vel/Velnull | SMIM1 | VEL*01 (rf) | VEL*-01 | 64_80del | Gln22fs | rs566629828 | |

| Assay 2 (Arabian panel) | |||||||||

| MNS | 002 | S/s | GYPB | GYPB*03 | GYPB* 04 (rf) | 143T | 143C | Met48Thr | rs7683365 |

| Rhesus | 004 | C/Cw | RHCE | RHCE*C | RHCE*Cw | 122A | 122G | Gln41Arg | rs138268848 |

| Rhesus | 004 | e/part. e or e+w | RHCE | RHCE* 01 (rf) | RHCE*697C>G | 697C | 697G | Gln233Glu | rs142246017 |

| Rhesus | 004 | e/part. e | RHCE | RHCE* 01 (rf) | RHCE*733C>G | 733C | 733G | Leu245Val | rs1053361 |

| Lutheran | 005 | Lua/Lub | BCAM | LU*01 | LU*02 (rf) | 230A | 230G | His77Arg | rs28399653 |

| Lutheran | 005 | Lu8/Lu14 | BCAM | LU*02 (rf) | LU02.14 | 611T | 611A | Met204Lys | rs28399656 |

| Kell | 006 | K/k | KEL | KEL*01.01 | KEL*02 (rf) | 578T | 578C | Met193Thr | rs8176058 |

| Kell | 006 | Kpa/Kpb | KEL | KEL*02.03 | KEL*02 (rf) | 841T | 841C | Trp281Arg | rs176059 |

| Kell | 006 | Jsa/Jsb | KEL | KEL* 02.06 | KEL*02 (rf) | 1790C | 1790T | Pro597Leu | rs176038 |

| Duffy | 008 | Fya/Fyb | ACKR1 | FY*01 | FY*02 (rf) | 125G | 125A | Gly42Asp | rs12075 |

| Duffy | 008 | Fyb/Fynull | ACKR1 | FY*02 | FY*02N.01 | −67t | −67c | Protein | rs2814778 |

| absent | |||||||||

| on RBC | |||||||||

| Kidd | 009 | Jka/Jkb | SLC14A1 | JK*01 | JK*02 (rf) | 838G | 838A | Asp280Asn | rs1058396 |

| Dombrock | 014 | Doa/Dob | ART4 | DO*01 (rf) | DO*02 | 793A | 793G | Asn265Asp | rs11276 |

| Dombrock | 014 | Jo(a+)/ Jo(a–) | ART4 | DO*01 (rf) | DO*01.–05 or | 350C | 350T | Thr117Ile | rs28362798 |

| or DO*02 | DO*02.–05 | ||||||||

| Colton | 015 | Coa/Cob | AQP1 | CO*01 (rf) | CO*02.01 | 134C | 134T | Ala45Val | rs28362692 |

| Indian | 023 | Ina/Inb | CD44 (IN) | IN*01 | IN*02 (rf) | 137C | 137G | Pro46Arg | rs369473842 |

Each of both assays was performed in 1 well. For panel 2 (Arabian donors), RHCE*667G>T, CO*601delG (Conull), VEL*64–80del (Velnull), and YT*01/YT*02 were determined by PCR-SSP. rf, reference allele; fs, frameshift.

The basics of MALDI-TOF MS blood groups screening have been described before [23, 26]. All primers were synthesized and HPLC cleaned up by TibMolbiol (Berlin, Germany) for the Arabian panel and by Metabion (Munich, Germany) for the German rare donor panel. Primer sequences will be available upon request from the authors. Instructions how to prepare the primer mix, the master mix, and PCR cycler protocol to generate the templates for the 2nd step had been provided as a Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheet by Agena Bioscience. After cleanup of the amplicon mix with shrimp alkaline phosphatase (included in the iPLEX® Pro kit), the mixture was used as template for the elongation of unextended primers.

The single base extension reaction using iPLEX® Pro reagents (Agena Bioscience) was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. After cleaning the reaction with an anion exchange resin, the samples were spotted automatically onto Spectro chips in a MassARRAY Nano Dispenser RS1000 (Agena Bioscience).

Extended primer masses were determined in the MassARRAY Dx Analyzer 4 (Agena Bioscience). All data assigning relevant masses to the respective alleles could be read by the assay editor of the MassARRAY Typer 4.0 and 4.1 software, respectively. Translation of the determined genotyping data into predicted blood group information was performed by algorithms programmed to in-house Microsoft Excel spreadsheets, or in case of the German rare donor panel, csv files were directly embedded into the blood bank laboratory software system by the MassARRAY Typer 4.0 tool/Hemo IDTMPanel Report.

The German rare donor assay had been validated before by at least one alternative method like serology, commercial PCR-SSP reaction (BAG Healthcare, Lich, Germany, and Innotrain, Kronberg, Germany), or sequence-based typing, dependent on the availability of typing sera or commercial test kits. All blood group SNPs included within the MALDI-TOF MS assays are listed in Table 2. The study on blood groups in Arabian countries was validated using repeated testing of 70 donor samples with a known rare blood group typing based on either serology and/or PCR-SSP or Sanger sequencing. Sixteen biallelic polymorphisms were included. The known blood groups covered 29 of 32 alleles without any discrepancies. No pretyping results were available for DO *01.-05 (encoding the antithetical glycoprotein of Joa) and the IN *01 and IN *02 alleles so that the presence of rare alleles during the screening should be confirmed by PCR-SSP or Sanger sequencing. One validation sample with a known RHCE *c.733C>G SNP additionally carried a heterozygous ART4 *c.350C>T mutation that induces DO *01.-05. Three control samples with a known S–s–U– phenotype due to a deficiency in GYPB exons 2–5 were reported as “no call” results in MALDI TOF, which corresponds to the expected value.

The SMIM1 *c.64–80del mutation, inducing the Velnullphenotype, the AQP1 *c.601delG mutation inducing the Conullphenotype, and the YT *01/YT *02 polymorphism that were included in assay 1 (German rare donors) were not compatible with the primer chemistry of assay 2 (Arabian donors), so that genotyping was performed separately by PCR-SSP. Additionally, RHCE *c.667G>T (RHCE *01.07, RHCE *ceMO) and the GYPB deletion that is associated with the S–s–U– phenotype were tested by in-house PCR-SSP. The S–s–U– PCR-SSP included 2 preparations specific for GYPB wild-type (wt) positions within introns 2 and 5, the latter being specific for GYPB *270+5g. In case of a homozygous GYPB *270+5g>t substitution, which induces a S–s–U+weakphenotype, the reaction would result in a homozygous amplicon loss, and the sample would be subjected to DNA sequencing. In short, 40–100 ng of DNA were added to a master mix including 0.5–1.0 U of Green Go Taq in Flexi buffer (Promega, Mannheim, Germany), between 1.5 and 3.0 mM MgCl2, 500 nM allele-specific sense and antisense primer each, 125 nM HGHI and HGHII internal control primer (all primers TibMolbiol), and 0.2 mM dNTP each (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). The Conull-PCR reaction included CRP I and CRPII primers as internal controls. All primers are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Primer sequences for PCR-SSP reactions and sequencing

| Gene | Primer name | Primer sequence | Usage |

|---|---|---|---|

| RHCE | CE_E5_F_Amp3 CE-E5_R_Amp4 D_E5_F_Seq |

5′-ACTACCACATGAACCTGAG-3′ 5′-TATGTGTGCTAGTCCTGTTAGAC-3′ 5′-AGACCTTTGGAGCAGGAGTG-3′ |

Amplification RHCE e5 Sequencing RHCE, e5, sense |

| RHCE | D_667T_F_Amp CE_667G_F_Amp CE_E5_R_Amp2 |

5′-GTGGATGTTCTGGCCAAGTT-3′ 5′-GTGGATGTTCTGGCCAAGTG-3′ 5′-TCTCACCTAGGTTTAGCCTCTGA-3′ |

PCR-SSP RHCE*667G, sense PCR-SSP RHCE*667G>T, sense PCR-SSP common, antisense |

| RHCE | CE_667G_F_Amp CE_733G_R |

5′-GTGGATGTTCTGGCCAAGTG-3′ 5′-GTCACCACACTGACTGCTAC-3′ |

PCR-SSP, sense PCR-SSP, antisense |

| ACKR1/FY | FY_AF FY_AR FY_S_F1 |

5′-CTTTTGAACTGCCTTTCCTTGG-3′ 5′-CTTCCCCACCACTGTCCTAATC-3′ 5′-GATGGAGGAGCAGTGAGAGTC-3′ |

Amplification FY Sequencing FY 5'UTR, sense |

| ACHE/YT | YTA_pos_se YTA_neg_se YT_com_anti-s |

5′-CATCAACGCGGGAGACTTCC-3′ 5′-CATCAACGCGGGAGACTTCA-3′ 5′-GGGAGGACTTCTGGGACTTC-3′ |

PCR-SSP Yta+, sense PCR-SSP Yta-, sense PCR-SSP common, antisense |

| ART4/DO | ART4_E2_F ART4_E2_R ART4_E2_F ART4_E2_F2 ART4_E2_R |

5′-CTGCAACCACATTCACCATC-3′ 5′-CCCAAAAACCCACTGAGAAA-3′ 5′-CTGCAACCACATTCACCATC-3′ 5′-GTGGCAAAAAGCCCACTTAG-3′ 5′-CCCAAAAACCCACTGAGAAA-3′ |

Amplification ART4 e2 Sequencing ART4 e2, sense Sequencing ART4 e2, sense Sequencing ART4 e2, antisense |

| AQP1/CO | CO-pos2_se CO-neg2_se CO 2 anti_se |

5′-GTCCTTTGGCTCCGCGG-3′ 5′-GTCCTTTGGCTCCGCGT-3′ 5′-TTCCTGTCCTCTGGCTGTCT-3′ |

PCR-SSP CO*601G, sense PCR-SSP CO*601delG, sense PCR-SSP common, antisense |

| SMIMl/Vel | VEL-pos1_anti-se VEL-neg1_anti-se VEL_1_se |

5′-GCCTCTTCTGTGCTGGACA-3′ 5′-GCCTCTTCTGTGCTGGACT-3′ 5′-CTCAGAGGGGGTCTTGACTG-3′ |

PCR-SSP Vel wt, antisense PCR-SSP Vel64-80del, antisense PCR-SSP common, sense |

| GYPB/Ss | GYPB_I5_G* GYBP_I5_R2 GYPB_E2_Def_F2 GYPB_E2_Def_R |

5′-TCGCCGACTGATAAAGGTGAG-3′ 5′-ATTTTATGCAGTTCTGTTTCTCTTC-3′ 5′-CTCCGAAATCATTTTTGTGATGT-3′ 5′-CAGAGGCTAGAATTCCTCTGTAGTAA-3′ |

PCR-SSP wt i5, sense PCR-SSP wt i5, antisense PCR-SSP wt i2, sense PCR-SSP wt i2, antisense |

Both, a missing GYPB exon 5 and a GYPB*270+5g>t substitution, which induces a S–s–U+weakphenotype, will result in an amplicon loss. e, exon; i, intron.

Some rare results of the MALDI-TOF MS analysis like RHCE mutations, KEL *02.06 or DO *01.-05 were counter checked by Sanger sequencing. In the case of discrepancies between MALDI-TOF MS genotyping and serological phenotyping within the German rare donor panel, either commercial PCR-SSP or DNA sequencing were added for further determination.

Statistics

All data were calculated as percent samples with homo- or heterozygosity for the 2 alternative alleles referring to the number of samples with unambiguous results. Typing failures (no calls) were not included in the frequency calculation. Absolute allele frequencies within each group (German rare donors and Arabian donors, respectively) were calculated by direct allele counting according to Hardy-Weinberg proportions. In cases were only 1 allele was determined, homozygosity was postulated, and the allele was counted twice.

Differences in allele numbers (calculated per group) between the different Arabian panels and the German rare donor panel were calculated by χ22 × 2 contingency table with Yates correction for frequencies of n < 5 and calculation in Microsoft Excel.

Results

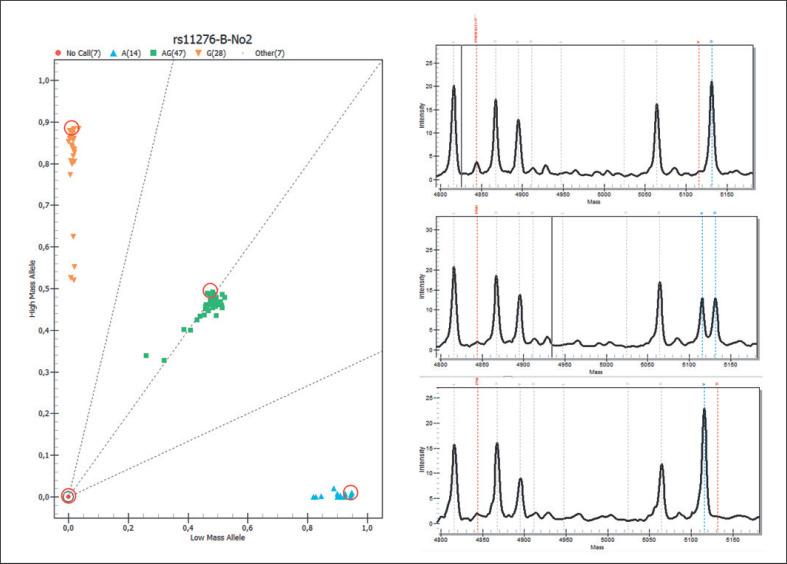

Blood group genotyping by MALDI-TOF MS proved to be reliable, efficient, and time saving. Within the rare donor panel, 20,529 samples were included, but not each sample was tested for each allele. Some samples were repeatedly included as controls and thus were excluded for the final evaluation. Only 1 sample produced no call results in all but 1 of the tested blood groups. Related to the single SNP pairs, the rate of no calls ranged between 1 (0.01%) for CO *01.01/CO *02.01 (Coa/Cob), JK *01/JK *02 (Jka/Jkb), RHCE *C/RHCE *Cw (C/Cw), IN *01/IN *02 (Ina/Inb), and KEL *01.01/KEL *02 (K/k) and 17 (1.5%) for GYPB *03/GYPB *04 (Ss) (Table 4). The overall failure rate over all samples and all alleles was 0.4% for the Arabian panel. Except for IN *01/ *IN *02 and the CO *601delG allele, 2 different genotypes could be observed for each polymorphism over all samples. As an example, the DO *01/ *02 (DO *A/DO *B) cluster plot from 1 plate and the detail panes of 3 samples are shown in Figure 1.

Table 4.

Genotyping results of different blood group polymorphisms in individuals from Arabian countries and Iran and Germany

| ISBT No. | Blood group polymorphism | Syria (n = 800), | Arabian Peninsula | Northern Africa | Iran (n = 147), | All Arabian/Iranian | German rare donor panel |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | (n = 123), n (%) | (n = 41), n (%) | n (%) | (n = 1,111), n (%) | n (%) | total n | |||

| 002 | GYPB*03/*03 (SS) | 106 (13.5) | 21 (17.2) | 2 (4.9) | 20 (13.8) | 149 (13.6) | 2,097 (10.3) | 20,499 | |

| GYPB*03/*04 (Ss) | 340 (43.3) | 39 (32.0) | 19 (46.3) | 62 (42.8) | 460 (42.1) | 8,730 (42.7) | |||

| GYPB*04/*04 (ss) | 340 (43.2) | 62 (50.8) | 20 (48.8) | 63 (43.4) | 485 (44.3) | 9,595 (47.0) | |||

| No call | 14 (1.8) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.4) | 17 (1.5) | 77 (0.4) | |||

| 004 | RHCE*C/*C# | 795 (99.4) | 122 (99.2) | 40 (100) | 144 (98.0) | 1,101 (99.2) | 7,322 (96.6) | 7,579 | |

| RHCE*C/*Cw | 5 (0.6) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.0) | 9 (0.8) | 248 (3.3) | |||

| RHCE*Cw*/Cw | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (0.1) | |||

| No call | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 3 (0.0) | |||

| RHCE*c.667G/G (wt) | 797 (99.6) | 122 (99.2) | 41 (100) | 147 (100) | 1,107 (99.6) | n.t. | |||

| RHCE*c.667G/T | 3 (0.4) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.4) | n.t. | |||

| RHCE*c.667T/T | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | n.t. | |||

| No call | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | n.t. | |||

| RHCE*c.697C/C (wt) | 794 (99.7) | 122 (100) | 40 (100) | 145 (100) | 1,101 (99.8) | n.t. | |||

| RHCE*c.697C/G | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.2) | n.t. | |||

| RHCE*c.697G/G | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | n.t. | |||

| No call | 4 (0.5) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (2.4) | 2 (1.4) | 8 (0.7) | n.t. | |||

| RHCE*c.733C/C (wt) | 769 (97.0) | 120 (98.4) | 28 (70.0) | 141 (97.9) | 1,058 (96.3) | n.t. | |||

| RHCE*c.733C/G | 23 (2.9) | 2 (1.6) | 12 (30.0) | 3 (2.1) | 40 (3.6) | n.t. | |||

| RHCE*c.733G/G | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | n.t. | |||

| No call | 7 (0.9) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (2.4) | 3 (2.0) | 12 (1.1) | n.t. | |||

| 005 | LU*01/*01 (Lua/Lua) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.8 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.2) | 26 (0.1) | 20,499 | |

| LU*01/*02 (Lua/Lub) | 19 (2.4) | 4 (3.3) | 2 (4.9) | 8 (5.4) | 33 (3.0) | 1,311 (6.5) | |||

| LU*02/*02 (Lub/Lub) | 777 (97.5) | 117 (95.9) | 39 (95.1) | 139 (94.6) | 1,072 (96.8) | 18,987 (93.4) | |||

| No call | 3 (0.4) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.4) | 175 (0.9) | |||

| LU*02/*02 (Lu8/Lu8) | 762 (95.4) | 121 (99.2) | 40 (100) | 142 (96.6) | 1,065 (96.1) | 19,187 (96.5) | 20,499 | ||

| LU*02/*02.14 (Lu8/Lu14) | 37 (4.6) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (3.4) | 43 (3.9) | 680 (3.4) | |||

| LU*02.14/*02.14 (Lu14/Lu14) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (0.1) | |||

| No call | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (2.4)) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.3) | 622 (3.0) | |||

| 006 | KEL*02/*02 (k/k) | 747 (93.4) | 114 (92.7 | 38 (95.0) | 137 (93.2) | 1,036 (93.3) | n.t. | ||

| KEL*02/*01.01 (k/K) | 50 (6.3) | 9 (7.3) | 2 (5.0) | 8 (5.4) | 69 (6.2) | n.t. | |||

| KEL*01.01./*01.01 (K/K) | 3 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.4) | 5 (0.5) | n.t. | |||

| No call | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | n.t. | |||

| KEL*02.03/*02.03 (Kpa/Kpa) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) | 20,494 | ||

| KEL*02.03/*02 (Kpa/Kpb) | 4 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (0.5) | 340 (1.7) | |||

| KEL*02/*02 (Kpb/Kpb) | 792 (99.5) | 122 (100) | 39 (97.5) | 145 (100) | 1,098 (99.5) | 20,083 (98.3) | |||

| No call | 4 (0.5) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (2.4) | 2 (1.4) | 8 (0.7) | 70 (0.3) | |||

| KEL* 02.06/*02.06 (Jsa/Jsa) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2,821 | ||

| KEL*02.06/*02 (Jsa/Jsb) | 6 (0.8) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) | 8 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| KEL* 02/* 02 (Jsb/Jsb) | 792 (99.2) | 122 (99.2) | 40 (100) | 145 (99.3) | 1,099 (99.3) | 2,790 (100) | |||

| No call | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.4) | 1 (0.7) | 4 (0.4) | 31 (1.1) | |||

| 008 | FY*01/*01 (Fya/Fya) | 139 (17.4) | 27 (22.0) | 6 (14.6) | 39 (26.5) | 211 (19.0) | 3,951 (19.3) | 20,510 | |

| FY*01/*02 (Fya/Fyb) FY*02/*02 (Fyb/Fyb) | 384 (48.1) | 48 (39.0) | 11 (26.8) | 70 (47.6) | 513 (46.2) | 9,896 (48.5) | |||

| 276 (34.5) | 48 (39.0) | 24 (58.5) | 38 (25.9) | 386 (34.8) | 6,574 (32.2) | ||||

| No call | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 89 (0.4) | |||

| FY*02N.01/*02N.01 (Fynull) | 10 (1.2) | 4 (3.3) | 8 (20.0) | 0 (0.0) | 22 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7,579 | ||

| FY*02N.01/*01 (Fynull/ Fya) | 75 (9.4) | 3 (2.4) | 3 (7.3) | 1 (0.7) | 82 (7.4) | 23 (0.3) | |||

| FY*02N.01/*02 (Fynull/ Fyb) | 75 (9.4) | 8 (6.5) | 11 (26.8) | 4 (2.7) | 98 (8.8) | 38 (0.5) | |||

| FY wt | 639 (80.0) | 108 (87.8) | 18 (45.0) | 142 (96.6) | 907 (81.8) | 7,513 (99.2) | |||

| No call | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.2) | 5(0.1) | |||

| 009 | JK*01/*01 (Jka/Jka) | 226 (28.3) | 34 (27.6) | 15 (37.5) | 32 (21.8) | 307 (27.7) | 5,472 (26.8) | 20,510 | |

| JK*01/*02 (Jka/Jkb) | 393 (49.1) | 67 (54.5) | 21 (52.5) | 90 (61.2) | 571 (51.4) | 10,225 (50.1) | |||

| JK*02/*02 (Jkb/Jkb) | 181 (22.6) | 22 (17.9) | 4 (10.0) | 25 (17.0) | 232 (20.9) | 4,707 (23.1) | |||

| No call | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 106 (0.5) | |||

| 011 | YT*01/*01 (Yta/Yta) | 607 (76.5) | 105 (86.1) | 41 (100) | 127 (86.4) | 878 (79.7 | 18,431 (90.2) | 20,499 | |

| YT*01/*02 (Yta/Ytb) | 172 (21.7) | 16 (13.1) | 0 (0.0) | 18 (12.2) | 206 (18.8 | 1,939 (9.5) | |||

| YT*02/*02 (Ytb/Ytb) | 14 (1.8) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.4) | 17 (1.5) | 63 (0.3) | |||

| No call | 7 (0.9) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (0.7) | 66 (0.3) | |||

| 014 | DO*01/*01 (Doa/Doa) | 157 (19.7) | 13 (10.7) | 8 (20.0) | 28 (19.2) | 206 (18.6) | 3,067 (15.0) | 20,515 | |

| DO*01/*02 (Doa/Dob) | 384 (48.2) | 75 (61.5) | 22 (55.0) | 76 (52.0) | 557 (50.4) | 9,522 (46.7) | |||

| DO*02/*02 (Dob/Dob) | 255 (32.0) | 34 (27.8) | 10 (25.0) | 42 (28.8) | 342 (31.0) | 7,820 (38.3) | |||

| No call | 3 (0.4) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (2.4) | 1 (0.7) | 5 (0.5) | 106 (0.5) | |||

| DO*01/*01 (Joa+/Joa+) | 797 (99.7) | 123 (100) | 40 (100) | 145 (100) | 1,105 (99.8) | 2,790 (100) | 2,821 | ||

| DO *01/*01.-05 (Joa+/Joa-) | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.0) | |||

| DO*01.-05/*01.-05 (Joa-/Joa-) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| No call | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.4) | 2 (1.4) | 4 (0.4) | 30 (1.1) | |||

| 015 | CO*01/*01 (Coa/Coa) | 791 (98.9) | 118 (95.9) | 40 (100) | 145 (98.6) | 1,094 (98.6) | 18,632 (91.6) | 20,529 | |

| CO*01/02.01 (Coa/Cob) | 9 (1.1) | 5 (4.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.4) | 16 (1.4) | 1,663 (8.2) | |||

| CO*02.01/*02.01 (Cob/Cob) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 46 (0.2) | |||

| No call | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 188 (0.9) | |||

| CO*01/*01 (Coa/Coa) | 795 (100) | 121 (100) | 41 (100) | 147 (100) | 1,106 (100) | 17,683 (100) | 17,868 | ||

| CO*01/*01N.06 (Coa/Conull) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| CO*01N.06/*01N.06 (Conull/Conull) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| No call | 5 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (0.5) | 185 (1.0) | |||

| 023 | IN*01/IN*01 (Ina/Ina) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | n.t. | ||

| IN*01/IN*02 (Ina/Inb) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | n.t. | |||

| IN*02/IN*02 (Inb/Inb) | 800 (100) | 123 (100) | 41 (100) | 147 (100) | 1,110 (100) | n.t. | |||

| No call | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.1) | n.t. | |||

| 034 | Vel*01/*01 (Vel/Vel) | 782 (97.9) | 121 (98.4) | 39 (95.1) | 146 (99.3) | 1,088 (98.0) | 16,916 (96.2) | 17,868 | |

| Vel*01/*-01 (Vel/Velnull) | 16 (2.0) | 2 (1.6) | 2 (4.9) | 1 (0.7) | 21 (1.9) | 644 (3.7) | |||

| Vel*-01/*-01 (Velnull/Velnull) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 10 (0.1) | |||

| No call | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 298 (1.7) | |||

Results from PCR-SSP typing are italicized. Calculation of genotype percentages is based on the total number of samples with a definite result. n.t., not tested.

Probands were not tested for C or c, but because the RHCE*c. 122A>G substitution in most cases is associated with Cwand not cw, the polymorphism is reported as C/Cw. FY*-67t>c was exclusively rated as FY*02.01N.

Fig. 1.

Cluster plot and detail panes of MALDI-TOF MS analysis. The cluster plot of 1 plate for the DO *01/ *02 polymorphism is shown on the left side with the samples homozygous for the lower mass (5115.4 Da) in light blue, those with homozygosity for the higher mass (5131.4 Da) in orange, and the heterozygotes in green squares. Three of the “no call” results belong to negative control samples. The detail panes of 3 samples (marked by red circles within the cluster plot) are shown on the right side. Peak heights and positions of the unextended primer (very low, because the primer was nearly completely consumed), the extended DO *01 -specific primer (nucleotide A), and the extended DO *02 -specific primer (nucleotide G) are marked.

Most apparent were differences in the FY frequencies. Twenty-two of 1,111 donors (2%) of the Arabian panel homozygously carried the FY promoter mutation FY *-67t>c (FY *02.01N/ *02.01N; Table 4). All these donors were also homozygous for FY *02 (FY *B). Thus, FY *-67t>c was exclusively rated as FY *02.01N. Of the 180 samples with heterozygosity for the FY *02.01N allele, 98 (54%) were homozygous for the FY *02 allele, too, whereas 82 (46%) carried FY *01/ *02. The overall allele frequency in the Arabian panel was 0.101 for FY *02.01N (all allele frequencies in Table 5). The highest frequency was found in Northern African donors with 0.375, and nearly 20% of them were homozygous for the mutation. This was in accordance with a higher FY *B frequency in this group (f = 0.720) compared to the German rare donor panel (f = 0.564, p < 0.01). Within the German rare donor panel, only 0.8% (n = 61) were heterozygous for FY *-67t>c (f = 0.004; p < 0.001 vs. the Arabian panel), with 23 (38%) of these being heterozygous for FY *01 and FY *02, while 38 (62%) carried an additional FY *02 wt allele. No single German rare donor individual was found with the homozygous mutation. Deduced from the donor names, it could be assumed that 30 of these donors were not of Middle European origin with a special impact of the FY *02/FY *02N.01 genotype on African or Arabian individuals (n = 17). But even when these donors were included, the differences in allele frequencies between the German rare donor panel and individuals from Syria or from Northern Africa were highly significant (p < 0.001 each, for the Syrian and the Northern African panel vs. the German rare donor panel).

Table 5.

Allele frequencies within the different groups

| ISBT No. | Allele | Syria (n = 800) | Arabian Peninsula (n = 123) | Northern Africa (n = 41) | Iran (n = 147) | All Arabian/ Iranian (n = 1,111) | German rare donor panel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 002 | GYPB*03 (S) | 0.351 | 0.332 | 0.280 | 0.352 | 0.346 | 0.316 |

| GYPB*04 (s) | 0.649 | 0.668 | 0.720 | 0.648 | 0.654 | 0.684 | |

| 004 | RHCE*02 (C) | 0.997 | 0.996 | 1.000 | 0.990 | 0.996 | 0.983 |

| RHCE*02.08.01 (Cw) | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.000 | 0.010 | 0.004 | 0.017 | |

| RHCE*c.667G (wt) | 0.998 | 0.996 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.998 | n.t. | |

| RHCE*c.667T | 0.002 | 0.004 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.002 | n.t. | |

| RHCE*c.697C (wt) | 0.999 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.999 | n.t. | |

| RHCE*c.697G | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | n.t. | |

| RHCE*c.733C (wt) | 0.984 | 0.992 | 0.850 | 0.990 | 0.981 | n.t. | |

| RHCE*c.733G | 0.016 | 0.008 | 0.150 | 0.010 | 0.019 | n.t. | |

| 005 | LU*A (LU*01) | 0.013 | 0.025 | 0.024 | 0.027 | 0.017 | 0.034 |

| LU*B (LU*02) | 0.987 | 0.975 | 0.976 | 0.973 | 0.983 | 0.966 | |

| LU*08 | 0.977 | 0.996 | 1.000 | 0.983 | 0.981 | 0.982 | |

| LU*14 (LU*02.14) | 0.023 | 0.004 | 0.000 | 0.017 | 0.019 | 0.018 | |

| 006 | KEL*01.01 (K) | 0.035 | 0.037 | 0.025 | 0.041 | 0.036 | n.t. |

| KEL*02 (k) | 0.965 | 0.963 | 0.975 | 0.959 | 0.964 | n.t. | |

| KP*B (KEL*02) | 0.997 | 1.000 | 0.987 | 1.000 | 0.998 | 0.992 | |

| KPA* (KEL*02.03) | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.013 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.008 | |

| JS*A (KEL*02.06) | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.004 | n.t. | |

| JS*B (KEL*02) | 0.996 | 0.996 | 1.000 | 0.997 | 0.996 | n.t. | |

| 008 | FY*A (FY*01) | 0.414 | 0.415 | 0.280 | 0.503 | 0.421 | 0.436 |

| FY*B (FY*02) | 0.586 | 0.585 | 0.720 | 0.497 | 0.579 | 0.564 | |

| Fy*-67t (wt) | 0.894 | 0.923 | 0.625 | 0.983 | 0.899 | 0.996 | |

| FY*02N.01 (Fy*null) | 0.106 | 0.077 | 0.375 | 0.017 | 0.101 | 0.004 | |

| 009 | JK*A (JK*01) | 0.528 | 0.549 | 0.637 | 0.524 | 0.534 | 0.519 |

| JK*B (JK*02) | 0.472 | 0.451 | 0.363 | 0.476 | 0.466 | 0.481 | |

| 011 | YT*A (YT*01) | 0.874 | 0.926 | 1.000 | 0.925 | 0.891 | 0,949 |

| YT*B (YT*02) | 0.126 | 0.074 | 0.000 | 0.075 | 0.109 | 0.051 | |

| 014 | DO*A (DO*01) | 0.438 | 0.414 | 0.475 | 0.452 | 0.438 | 0.384 |

| DO*B (DO*02) | 0.562 | 0.586 | 0.525 | 0.548 | 0.562 | 0.616 | |

| DO*01 (Joa+) | 0.999 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.999 | 1.000 | |

| DO*01–5 (Joa−) | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | |

| 015 | CO*A (CO*01) | 0.994 | 0.980 | 1.000 | 0.993 | 0.993 | 0.957 |

| CO*B (CO*02.01) | 0.006 | 0.029 | 0.000 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.043 | |

| CO wt | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

| CO*01N.06 (Conull) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 023 | IN*A (IN*01) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | n.t. |

| IN*B (IN*02) | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | n.t. | |

| 034 | VEL*01 (Vel) | 0.989 | 0.992 | 0.976 | 0.997 | 0.991 | 0.981 |

| VEL*–01 (Velnull) | 0.011 | 0.008 | 0.024 | 0.003 | 0.009 | 0.019 | |

Number of donors tested in the German rare donor panel varies between 2,821 and 20,529 for the different blood groups. n.t., not tested.

A special focus was put on RHCE mutations within the Arabian panel. A total of 47 samples with RHCE exon 5 mutations other than RHCE *c.676G (e) and RHCE *c.676C (E) were found. Forty samples typed heterozygous for the RHCE *c.733C>G mutation by MALDI-TOF MS, and 1 Syrian sample was homozygous. Applying a PCR-SSP approach with RHCE *c.676G- and *c.733G -specific amplification primers (Table 3), it could be demonstrated that both SNPs were in 1 haplotype within each of these 41 samples, that is, the RHCE *c.773G allele was a mutation of Rhesus e. The RHCE *c.733G allele frequency was highest in Northern African probands with f = 0.150, followed by Syrians with 0.016, and lowest in individuals from the Arabian Peninsula with 0.008. Contrary, RHCE *Cw was less frequent in the Arabian panel than in the German rare donor panel (Table 4; p < 0.001).

The Vel *c.64–80del mutation (VEL *-01) that is the main basis of the Velnullphenotype was found with allele frequencies between 0.003 in donors from Iran and 0.024 in Northern African donors, which was in the same range as for the German donors (f = 0.019). All but 1 individual from Syria carried only 1 copy of the mutated allele, so that a Vel-positive phenotype was predicted.

The LU *14 allele was present heterozygously in 37 out of 800 donors from Syria (4.6%) and 5 of 147 (3.4%) from Iran (f = 0.023 and 0.017, respectively), and thus the frequency was comparable with the German panel (f = 0.018). The LU *B and LU *A rates were comparable within the different groups.

Distribution of the DO alleles DO *01 and DO *02 showed higher differences between the Arabian panels than between these panels and the German rare donor panel (Table 4). Only 2 Syrian individuals (0.3%, allele frequency f = 0.001) heterozygously carried the DO *01.-05 allele. In both samples, the mutation was confirmed by DNA sequencing. One sample was DO *01/ *01 and the other one was DO *01/ *02, but it is not known whether the *c.350C>T substitution in both samples was in 1 haplotype with DO *01 or whether, alternatively, a rare DO *02.-05 allele was present in the DO *01/ *02 donor.

Contrary to the German rare donor panel where no KEL *02.06 -positive sample was detected, 0.8% of the Syrian donors and those from the Arabian Peninsula were heterozygous for KEL *02.06/ *02 (Jsa/Jsb; p < 0.001).

YT *B was more frequent in Syrian probands (f = 0.126) than in Northern Africans (f = 0.000) with 1.8% of the Syrians carrying YT *B homozygously. The frequency within the German rare donor panel was in between (f = 0.051; p < 0.001 for Syrian vs. German rare donor panel).

The GYPB *03 and *04 alleles (S and s) were distributed rather similar between the different groups with a slight overrepresentation of GYPB *04 within Syrian donors (p < 0.01). One Northern African donor was typed as GYPB *04/ *04 (ss) by mass spectrometry, but the GYPB intron 5-specific PCR-SSP reaction with a wt GYPB *270+5g -specific primer was negative. DNA sequencing demonstrated a homozygous GYPB *270+5g>t mutation that induces the S–s–U+weakphenotype independent of the presence of the GYPB *03 (S) or GYPB *04 (s) allele. No donor with a complete lack of GYPB was identified by GYPB intron 2- and 5-specific PCR-SSP, but 17 samples produced no call results in the MALDI assay. In order to test for possible additional mutations within primer annealing sites that might cause an allele dropout, 16 of these samples were genotyped by DNA sequencing. Eleven samples typed as GYPB *03/ *04 and 5 as GYPB *04/ *04. No additional mutation was found.

Two samples from the German rare donor panel that were determined as GYPB *04/ *04 (ss) by MALDI were known to be positive for the presence of S (GYPB *03) from earlier serology typing. DNA sequencing in both samples identified the presence of both, GYPB *03 (S) and GYPB *04 (s) alleles and a heterozygous GYPB *c.161G>A substitution that is known to induce a Mit+ (MNS:24) phenotype. One of the 2 samples additionally exhibited a heterozygous GYPB *249C>G exchange that induces a p. Tyr83stop.

All samples with a reported result were homozygous for the wt IN *02/IN *0 2. None of the 1,111 Arabian and 17,683 German rare donor samples carried the CO *601delG mutation that induces a Conullphenotype (Table 4). Mass spectrometry demonstrated the presence of CO *01 (CO *A) in each sample of the Arabian panel with allele frequencies between 0.993 and 1.000, whereas 0.2% of the German rare donors were homozygous for CO *02.01 (p < 0.001 for the Arabian vs. the German rare donor collective). Between 0.0% (Northern Africa) and 4.1% (Arabian Peninsula) carried 1 CO *02.01 (CO *B) copy, which is less than in the German rare donor panel (8.2%).

All other blood groups were equally distributed between the different groups.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that molecular typing for blood groups other than ABO and Rhesus CDE has been performed on a larger panel of blood donors from Arabian countries and Iran with a special emphasis on Syria. Identification of donors with rare blood groups is a challenge when the local donor population differs from the genetic background of patients. Since the increase in migration of people from Arabian countries, especially from Syria, to Europe in 2015, a higher number of patients suffering from hemoglobinopathies has been observed. Hemoglobinopathies have been addressed as a major migration-related aspect in blood supply [7]. Contrary to ABO and Rhesus CDE [9, 10, 11, 12, 17, 28], frequency information on further blood groups in these countries is largely missing, except for a French-Afghan-Pakistan collaboration on 15 biallelic polymorphisms in 13 Afghan and Pakistani populations (n = 599) [13].

The results of the German rare donor panel with >20,000 samples served as controls but did not include each allele tested by the Arabian assay [25]. It enabled to spot rare alleles within the local donor population like CO *01 negative (n = 46), YT *01 negative (n = 63), LU *02 negative (n = 26), LU *08 negative (n = 10), VEL *01 negative (n = 10), and KEL *02.03 homozygous (n = 1).

The Arabian Peninsula was the initial site of the out-of-Africa migrations between 60,000 and 125,000 years ago. These indigenous Arabs are the most distant relatives of all other contemporary non-Africans and are direct descendants of the first Eurasian populations established by the out-of-Africa bottleneck migrations [29]. For this reason, we put a special focus on African blood group mutations that also might be present in modern Arabian populations at a higher frequency than in European populations.

We clearly demonstrated that especially the Fy silencing mutation FY *-67t<c is more frequent in Arabian countries than in our donor population. The frequency was highest within the small group of 41 individuals from Northern Africa (20% being homozygous for the mutation). Only the mother country but not the ethnicities of these individuals, who might be mostly of African black ancestry, is known. Because the Northern African group was the smallest, relevance of the observations is restricted. FY *-67t<c allele frequencies in our Arabian panels decreased from 0.375 (Northern Africa) to 0.017 (Iran) with growing distance from Central Africa. About 1.2% of Syrian individuals were homozygous for FY *02N.01, which corresponds to the findings in Afghan and other western Asian populations [13, 28], but is lower than in Israeli Arabs [14]. Because each of these individuals carried at least 1 FY *02 allele, the mutation in general was assigned to the FY *02N.01 allele. However, it cannot completely be excluded that in single cases a FY *01 allele was affected by the FY *-67t>c mutation (FY *01N.01 allele), as it was demonstrated in rare cases in Papua New Guinea [18]. Interestingly, 61 of 7,579 German rare blood group donors also carried the mutation that was described as very rare in Central Europe [16, 18]. None of these donors was homozygous for the mutation, so that none would carry the Fy(a-b-) phenotype. Twenty-three of these were heterozygous for FY *01 and FY *02 with a predicted Fy(a+b–) phenotype, while 38 carried an additional FY *02 wt allele that is predicted to result in the Fy(a–b+) phenotype. Our donor registry does not systematically record the ethnicity of donors. Half of the individuals with the FY *-67t>c mutation can be assigned to an African or Arabian ancestry due to their names, but 31 donors with typical German names remained. Of course, names are not an unequivocal proof for the ethnicity, but this might be a hint for the presence of the FY silencing mutation in donors with Middle European ancestry as it had been calculated even before the correct mutation had been decoded [28]. On the other hand, these findings clearly demonstrate that a small minority of individuals represented in the German rare donor panel is not of Middle European ancestry, as also demonstrated for a Swiss cohort [23].

Our MALDI-TOF MS panel did not include typing of Rhesus C, c, E, and e because these blood groups can be easily determined by serology. RHCE mutations like RHCE *c.667G>T(p.Val223Phe), *c.697C>G(p.Gln233Glu), and *c.733C>G (p.Leu245Val) are rather frequent in African individuals and were therefore included in molecular screening [30, 31, 32]. Especially the RHCE *c.733C>G substitution was detected in 41 individuals of the Arabian panel (f = 0.019), and, in each case, a RHCE *c.676G (RHCE *e)-specific PCR-SSP approach demonstrated the presence of RHCE *c.676G and *c.733G in 1 haplotype. The substitution that can be associated with different further RHCE mutations is reported in partial c, partial e phenotypes that can be of clinical significance [18]. In contrast, the RHCE *c.122A>G substitution (Cw) was less frequent in the Arabian panel.

Between 5.0% (Northern Africans) and 7.3% (Arabian Peninsula) of donors from the Arabian Panel were positive for the KEL *01.01 allele that codes for k (cellano; f = 0.025–0.041), which is in contrast to previous findings of up to 25% in Arabs [18] but corresponds with allele frequencies of about 0.034 in Western Asia [28]. Antibodies to Jsbare very rare but can cause hemolytic transfusion reactions [33]. Eight individuals with heterozygosity for the KEL *02.06 allele (f = 0.004; encoding Jsa) were identified within the Arabian panel, which is in the range of a study on Israeli Arabs [14]. The allele is very rare within Caucasians (<0.01%) but rather frequent within Blacks [18]. In contrast to a Swiss study, no carrier of the KEL *02.06 allele was detected within the German rare donor panel [24].

Intrapanel frequency variation in YT *01 (Yta) and YT *02 (Ytb) was higher within the Arabian panel than the German rare donor panel with YT *02 frequencies between 0.000 in Northern Africans up to 0.126 in Syrians and 0.051 in Germans. The frequency in Syrians is within the same range as for Israelis [18]. Homozygosity for YT *02 might enable immunization to Yta, but the antibodies are supposed to be of minor clinical effects [18].

Samples with homozygosity for the VEL *-01 allele with a predicted Vel-negative phenotype showed a comparable frequency in both the Arabian and the German rare donor panel with about 0.055%, which seems to be within the same range as data reported from different regions in Switzerland and Southwestern Germany [34, 35]. We did not test for further reported SMIM1 mutations like rs1175550 and rs143702418, which both induce mutations within the noncoding region of intron 2 and independently modulate Vel antigen expression [36].

IN *01 and CO *01N.06 were not detected in any sample, not even within the Iranian collective, although these mutations seem to have originated in Southern Asia or Iran [18, 37]. This again can be attributed to the rather low number of samples from Iran. Because no IN *01 samples were available for validation of the assay, it could only be deduced from the peak heights and the areas under the peaks that the assay per se did work, but we cannot exclude that we might have missed an IN *01 -positive sample. The CO *01N.06 allele was not at all detected. The mutation was described before in German and Spanish Roma with a Co(a–b–) phenotype so that samples were available for validation [38]. Because Roma migrated from north/northwestern India to Europe about 1,500 years ago via the Near or Middle East and the Balkans, presence of the mutation at least within individuals from Iran was considered [37], but the absolute number of individuals was too low taking into account an allele frequency of 0.0036 in Spanish Roma [39]. We aimed to analyze at least 1,000 samples of Arabian donors in order to identify alleles with a frequency of 0.05 with sufficient probability. The complete panel of 1,111 donors achieves this requirement, but discrimination between smaller subcollectives cannot warrant identification of rare alleles.

Because in rare cases the U-negative phenotype has been the cause of hemolytic transfusion reactions in African individuals, and GYPB mutations can either induce the S–s–U– or the S–s–U+varphenotype [18, 40, 41], we included both, the MALDI-TOF MS screening of the GYPB *03/ *04 (Ss) polymorphism and PCR-SSP determination of the wt GYPB *270+5g in intron 5 in our screening of the Arabian panel. One Northern African donor was typed as GYPB *04/ *04 (ss) by mass spectrometry, but the GYPB intron 5 (counting including pseudo exon 3)-specific PCR-SSP reaction with a GYPB *270+5g -specific primer was negative. The suspected GYPB *270+5g>t mutation that predicts the S–s–U+weakphenotype was confirmed by DNA sequencing. This fact clearly demonstrates that both, single base extension reactions and PCR-SSP only are designed to detect specific SNPs. Polymorphisms other than those covered by the specific assay may remain undetected, and thus phenotypes can only be predicted but not unambiguously determined. The GYPB *270+5g>t allele frequency could not be determined because we only tested for the wt allele and thus only detected the homozygous mutation. Two further samples from the German rare donor panel attracted attention because the samples were known as S positive (GYPB *03) from serological testing but typed as GYPB *04/ *04 by MALDI-TOF MS. DNA sequencing in both samples identified the presence of both, GYPB *03 (S) and GYPB *04 (s) alleles. An additional heterozygous GYPB *c.161G>A substitution seems to have induced an allele dropout and a false-negative GYPB *04 result. One of the 2 samples additionally carried a heterozygous GYPB *c.249C> G (Tyr83stop) mutation, but it is not known which of the 2 alleles was affected by the truncation; 17 samples from the Arabian panel failed in MALDI-TOF MS but were positive in the GYPB *270+5g PCR-SSP reaction, and demonstrated regular GYPB *03 and *04 alleles in DNA sequencing, thus excluding amplification failures due to mutations within the MALDI primer annealing sites.

Allele dropouts caused by mutations within the primer annealing sequences, as shown for the GYPB *c.161G>A substitution and further unrecognized mutations in general, might be considered disadvantages of molecular typing that are designed to detect SNPs. For the majority of the Arabian panel samples, no phenotype data except for ABO, Rhesus, and Kell exist, and thus false-negative results caused by allele dropouts may be undetected. However, extended blood group typing by serology is not applicable for high sample numbers, especially when rare typing sera are not available. During the last decade, different molecular strategies for extended blood group typing have been developed. These include multiplex PCR-SSP and TaqMan reactions, PCR oligonucleotide extension assays with fluorescent terminator nucleotides, and pooled capillary electrophoresis with fluorescent dyes [19, 42, 43, 44]. MALDI-TOF MS has been applied to type thousands of blood donors [23, 24, 34]. Besides the high accuracy and interlaboratory concordance, this methodology has the advantage of a high flexibility for the user that enables adjusted combinations of blood group SNPs within 1 multiplex assay [23, 24] that correspond to the requirements of the blood service. We introduced MALDI-TOF MS genotyping in our blood service in 2012 and, over the years, adapted the assay design to include as many clinically relevant blood group SNPs as possible within 1 well in order to lower the costs per allele. Up to 36 SNPs and more can be included provided that the assay designer can assign amplicon primers and single base extension primers that do not impede each other and enable mass discriminations of at least 16 Da within a detection range of 4,300–9,000 Da. Failure rates within the Arabian panel with 0.1–1.5% were very low and comparable to published data [34].

Next-generation sequencing has been introduced to perform high-throughput multiplex blood group typing with a coverage of either whole genes or at least complete exon sequencing [45, 46, 47, 48]. Despite the rather time-consuming procedure, the rapidly decreasing costs make next-generation sequencing attractive for blood group genotyping because it minimizes detection failures due to allele dropout and does not only identify known blood group SNPs of interest, but can also detect novel alleles that might be of clinical relevance [49]. However, the phenotype of new or rare alleles can only be predicted and requires confirmation by means of serology.

Altogether, we presented clinically relevant blood group frequencies in individuals from Arabian countries and Iran in comparison to the local German donor population. The study may help to provide transfusion centers with information regarding the transfusion support of patients from these regions.

Statement of Ethics

All subjects provided informed consent, and the study on blood group frequencies in Arabian individuals was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Chamber of Rhineland-Palatinate in Mainz, Germany.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Funding Sources

The study was supported by in-house grants of the German Red Cross Blood Service West.

Author Contributions

B.K.F initiated and coordinated the study, evaluated data and wrote the manuscript. V.S. analyzed samples, acquired and evaluated data, and carefully revised the manuscript. B.J. initiated and coordinated the German rare donor study, evaluated data and carefully revised the manuscript. A.O. and T.Z. initiated and supervised the study, discussed the topic and revised the manuscript. O.O. coordinated and supervised provision of Arabian donor samples. A.J. and M.S. organized the provision of samples from Syrian donors, managed the laboratory work flow and data acquisition, and performed the experiments.

Acknowledgment

The authors are grateful to Natalie Wolffsdorf for data collection and technical expertise.

References

- 1.Daniels G. Human Blood Groups. Oxford: Blackwell; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seltsam A, Wagner FF, Salama A, Flegel WA. Antibodies to high-frequency antigens may decrease the quality of transfusion support: an observational study. Transfusion. 2003 Nov;43((11)):1563–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2003.00565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nance S, Scharberg EA, Thornton N, Yahalom V, Sareneva I, Lomas-Francis C. International rare donor panels: a review. Vox Sang. 2016 Apr;110((3)):209–18. doi: 10.1111/vox.12357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.UNHCR 2019. https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/mediterranean#_ga=2.153274680.1029811591.1559134435-1974819020.1559134435(Last accessed 29.05.2019.

- 5.BPB Asylum Applicants in Germany. 2019. https://www.bpb.de/gesellschaft/migration/flucht/265708/asylantraege-und-asylsuchende(Last accessed 29.05.2019.

- 6.BAmf Actual data asylum. 2019. http://www.bamf.de/DE/Infothek/Statistiken/Asylzahlen/AktuelleZahlen/aktuelle-zahlen-asyl-node.html(Last accessed 29.05.2019.

- 7.Kohne E, Kleihauer E. Hemoglobinopathies: a longitudinal study over four decades. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2010 Feb;107((5)):65–71. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2010.0065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aguilar Martinez P, Angastiniotis M, Eleftheriou A, Gulbis B, Mañú Pereira MM, Petrova-Benedict R, et al. Haemoglobinopathies in Europe: health & migration policy perspectives. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014 Jul;9((1)):97. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-9-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El-Wahhab SY, Alhawary AS, Shbair AS, et al. Frequency of ABO and Rh(D) blood groups in five governorates in Gaza-Strip. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2007;23:924–7. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karim F, Moiz B, Muhammad FJ, Ausat F, Khurshid M. Rhesus and Kell Phenotyping of Voluntary Blood Donors: Foundation of a Donor Data Bank. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2015 Oct;25((10)):757760–760. doi: 10.2015/JCPSP.757760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.AL-Ubadi AEM Genetic analysis of ABO and Rh(D) blood groups in Arab Baghdadi Ethnic Groups. Al-Mustansiriyah J Sci. 2015;24:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia-Hejl C, Martinaud C, de Rudnicki S, Sanmartin N, Clavier B, Chianea D, et al. Blood group antigens frequencies in Kabul, Afghanistan. Transfus Apheresis Sci. 2014 Apr;50((2)):307–8. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mazières S, Temory SA, Vasseur H, Gallian P, Di Cristofaro J, Chiaroni J. Blood group typing in five Afghan populations in the North Hindu-Kush region: implications for blood transfusion practice. Transfus Med. 2013 Jun;23((3)):167–74. doi: 10.1111/tme.12038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sandler SG, Kravitz C, Sharon R, Hermoni D, Ezekiel E, Cohen T. The Duffy blood group system in Israeli Jews and Arabs. Vox Sang. 1979;37((1)):41–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.1979.tb02267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Höher G, Fiegenbaum M, Almeida S. Molecular basis of the Duffy blood group system. Blood Transfus. 2018 Jan;16((1)):93–100. doi: 10.2450/2017.0119-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howes RE, Patil AP, Piel FB, Nyangiri OA, Kabaria CW, Gething PW, et al. The global distribution of the Duffy blood group. Nat Commun. 2011;2((1)):266. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keramati MR, Shakibaei H, Kheiyyami MI, Ayatollahi H, Badiei Z, Samavati M, et al. Blood group antigens frequencies in the northeast of Iran. Transfus Apheresis Sci. 2011 Oct;45((2)):133–6. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reid ME, Lomas-Francis C. The Blood Group Antigen Facts Book. 2nd ed. London, Amsterdam, Burlington, San Diego: Elsevier; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Portegys J, Rink G, Bloos P, Scharberg EA, Klüter H, Bugert P. Towards a Regional Registry of Extended Typed Blood Donors: Molecular Typing for Blood Group, Platelet and Granulocyte Antigens. Transfus Med Hemother. 2018 Oct;45((5)):331–40. doi: 10.1159/000493555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seltsam A, Doescher A. Sequence-Based Typing of Human Blood Groups. Transfus Med Hemother. 2009;36((3)):204–12. doi: 10.1159/000217322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Schoot CE, de Haas M, Engelfriet CP, Reesink HW, Panzer S, Jungbauer C, et al. Genotyping for red blood cell polymorphisms. Vox Sang. 2009 Feb;96((2)):167–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2008.01131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wagner FF, Bittner R, Petershofen EK, Doescher A, Müller TH. Cost-efficient sequence-specific priming-polymerase chain reaction screening for blood donors with rare phenotypes. Transfusion. 2008 Jun;48((6)):1169–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gassner C, Meyer S, Frey BM, Vollmert C. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation, time-of-flight mass spectrometry-based blood group genotyping—the alternative approach. Transfus Med Rev. 2013 Jan;27((1)):2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meyer S, Vollmert C, Trost N, Brönnimann C, Gottschalk J, Buser A, et al. High-throughput Kell, Kidd, and Duffy matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization, time-of-flight mass spectrometry-based blood group genotyping of 4000 donors shows close to full concordance with serotyping and detects new alleles. Transfusion. 2014 Dec;54((12)):3198–207. doi: 10.1111/trf.12715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Just B, Reil A, Deitenbeck R, Flesch BK. Molecular blood group typing by means of MALDI-TOF MS. In: Hemother TM, editor. 52 Annual Meeting of the German Society for Transfusion Medicine and Immunohematology Lübeck. Germany: 2018. p. 78. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyer S, Trost N, Frey BM, Gassner C. Parallel donor genotyping for 46 selected blood group and 4 human platelet antigens using high-throughput MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1310:51–70. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2690-9_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jongruamklang P, Gassner C, Meyer S, Kummasook A, Darlison M, Boonlum C, et al. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry analysis of 36 blood group alleles among 396 Thai samples reveals region-specific variants. Transfusion. 2018 Jul;58((7)):1752–62. doi: 10.1111/trf.14624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hubert W. Populationsgenetik der Blutgruppensysteme des Menschen. Stuttgart: E Schweizerbart'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodriguez-Flores JL, Fakhro K, Agosto-Perez F, Ramstetter MD, Arbiza L, Vincent TL, et al. Indigenous Arabs are descendants of the earliest split from ancient Eurasian populations. Genome Res. 2016 Feb;26((2)):151–62. doi: 10.1101/gr.191478.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pham BN, Peyrard T, Juszczak G, Beolet M, Deram G, Martin-Blanc S, et al. Analysis of RhCE variants among 806 individuals in France: considerations for transfusion safety, with emphasis on patients with sickle cell disease. Transfusion. 2011 Jun;51((6)):1249–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.02970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pham BN, Peyrard T, Juszczak G, Dubeaux I, Gien D, Blancher A, et al. Heterogeneous molecular background of the weak C, VS+, hr B-, Hr B- phenotype in black persons. Transfusion. 2009 Mar;49((3)):495–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.02005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Westhoff CM, Vege S, Horn T, Hue-Roye K, Halter Hipsky C, Lomas-Francis C, et al. RHCE*ceMO is frequently in cis to RHD*DAU0 and encodes a hr(S) -, hr(B) -, RH:-61 phenotype in black persons: clinical significance. Transfusion. 2013 Nov;53((11 Suppl 2)):2983–9. doi: 10.1111/trf.12271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yuan S, Ewing NP, Bailey D, Salvador M, Wang S. Transfusion of multiple units of Js(b+) red blood cells in the presence of anti-Jsb in a patient with sickle beta-thalassemia disease and a review of the literature. Immunohematology. 2007;23((2)):75–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gassner C, Degenhardt F, Meyer S, Vollmert C, Trost N, Neuenschwander K, et al. Low-Frequency Blood Group Antigens in Switzerland. Transfus Med Hemother. 2018 Jul;45((4)):239–50. doi: 10.1159/000490714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wieckhusen C, Rink G, Scharberg EA, Rothenberger S, Kömürcü N, Bugert P. Molecular Screening for Vel- Blood Donors in Southwestern Germany. Transfus Med Hemother. 2015 Nov;42((6)):356–60. doi: 10.1159/000440791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Christophersen MK, Jöud M, Ajore R, Vege S, Ljungdahl KW, Westhoff CM, et al. SMIM1 variants rs1175550 and rs143702418 independently modulate Vel blood group antigen expression. Sci Rep. 2017 Jan;7((1)):40451. doi: 10.1038/srep40451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mendizabal I, Lao O, Marigorta UM, Wollstein A, Gusmão L, Ferak V, et al. Reconstructing the population history of European Romani from genome-wide data. Curr Biol. 2012 Dec;22((24)):2342–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Flesch BK, Just B, Deitenbeck R, Reil A, Bux J, Nogués N, et al. The AQP1 mutation c.601delG causes the Co-negative phenotype in four patients belonging to the Romani (Gypsy) ethnic group. Blood Transfus. 2014 Jan;12((1)):73–7. doi: 10.2450/2013.0067-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flesch BK, Morar B, Comas D, Muñiz-Diaz E, Nogués N, Kalaydjieva L. The AQP1 del601G mutation in different European Romani (Gypsy) populations. Blood Transfus. 2016 Nov;14((6)):580–1. doi: 10.2450/2016.0274-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang CH, Johe K, Moulds JJ, Siebert PD, Fukuda M, Blumenfeld OO. Delta glycophorin (glycophorin B) gene deletion in two individuals homozygous for the S—s—U— blood group phenotype. Blood. 1987 Dec;70((6)):1830–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Storry JR, Reid ME, Fetics S, Huang CH. Mutations in GYPB exon 5 drive the S-s-U+(var) phenotype in persons of African descent: implications for transfusion. Transfusion. 2003 Dec;43((12)):1738–47. doi: 10.1046/j.0041-1132.2003.00585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jungbauer C, Hobel CM, Schwartz DW, Mayr WR. High-throughput multiplex PCR genotyping for 35 red blood cell antigens in blood donors. Vox Sang. 2012 Apr;102((3)):234–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2011.01542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Denomme GA, Van Oene M. High-throughput multiplex single-nucleotide polymorphism analysis for red cell and platelet antigen genotypes. Transfusion. 2005 May;45((5)):660–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2005.04365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wagner FF, Doescher A, Bittner R, Müller TH. Extended Donor Typing by Pooled Capillary Electrophoresis: Impact in a Routine Setting. Transfus Med Hemother. 2018 Jul;45((4)):225–37. doi: 10.1159/000490155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Belsito A, Magnussen K, Napoli C. Emerging strategies of blood group genotyping for patients with hemoglobinopathies. Transfus Apheresis Sci. 2017 Apr;56((2)):206–13. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2016.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fichou Y, Audrézet MP, Guéguen P, Le Maréchal C, Férec C. Next-generation sequencing is a credible strategy for blood group genotyping. Br J Haematol. 2014 Nov;167((4)):554–62. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tilley L, Green C, Poole J, Gaskell A, Ridgwell K, Burton NM, et al. A new blood group system, RHAG: three antigens resulting from amino acid substitutions in the Rh-associated glycoprotein. Vox Sang. 2010 Feb;98((2)):151–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2009.01243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu Z, Liu M, Mercado T, Illoh O, Davey R. Extended blood group molecular typing and next-generation sequencing. Transfus Med Rev. 2014 Oct;28((4)):177–86. doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tilley L, Grimsley S. Is Next Generation Sequencing the future of blood group testing? Transfus Apheresis Sci. 2014 Apr;50((2)):183–8. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2014.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]