Abstract

Background:

Log odds of positive nodes (LODDS), defined as the log of the ratio between the number of positive nodes and the number of negative nodes, has been recently introduced as a tool in predicting prognosis. This study aims to establish the effective and prognostic value of LODDS in predicting the survival outcome of CRC patients undergoing surgical resection.

Methods:

The study population is represented by 323 consecutive patients with primary colon or rectal adenocarcinoma that underwent curative resection. LODDS values were calculated by empirical logistic formula, log(pnod + 0.5)/(tnod-pnod + 0.5). It was defined as the log of the ratio between the number of positive nodes and the number of negative nodes. The patients were divided into three groups: LODDS0 (≤ −1.36), LODDS1 (> −1.36 ≤ −0.53), LODDS2 (> −0.53).

Results:

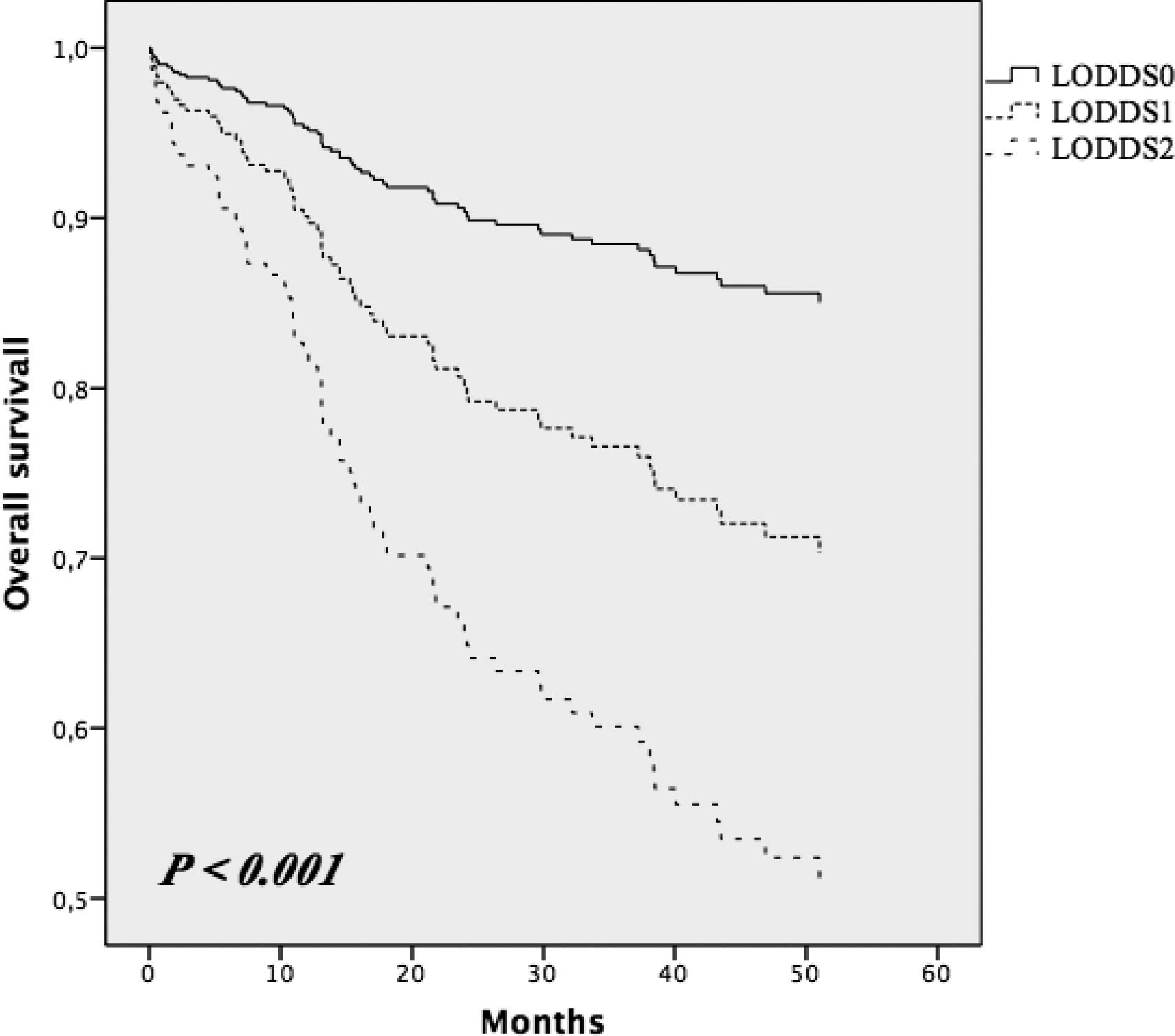

Kaplan-Maier curve analyses showed 3-year OS rates of the patients staged by LODDS classification. These values were 88.3%, 74.8% and 61.8% for LODDS0, LODDS1 and LODDS2, respectively (P= < 0.001). In a multivariate analysis, LODDS is an independent prognostic factor of 3-year OS. This is in contrast to pN stage and lymph node ratio, which shows no statistical significance. ROC analyses showed that LODDS predicted OS better than lymph node ratio.

Conclusion:

LODDS classification has a better prognostic effect than pN stage and lymph node ratio. LODDS offers a finer stratification and accurately predicts survival of CRC patients.

Keywords: colon cancer, rectum cancer, LODDS, adenocarcinoma, lymph nodes

Introduction

Colorectal carcinoma (CRC) is one of the most common causes of cancer-related deaths in Western countries. The 5-year survival rate has been reported to range from 93% in Stage I, 95–75% in Stage II, and 83–44% in Stage III tumors.[1] Approximately 75% of these patients will present with potentially curable disease that is treated by surgical resection. Surgical treatment should include resection of the affected segment of bowel and an en bloc resection of the associated draining lymph nodes to the level of the origin of the primary blood supply involving the segment of bowel.

Primary tumor and lymph node status are important prognostic factors for colorectal cancer patients. In particular, metastasis to the regional lymph nodes (LNs) is the most important indication for postoperative treatment and is an outcome predictor for colorectal patients.[2] In the seventh edition of the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) and the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Tumor Node Metastasis (TNM) staging system, regional lymph nodes are classified as N1 and N2 according to the number of involved nodes.[3]

Because of the high risk for recurrence of colon cancer, the current international guidelines on CRC treatment developed by the American Society of Clinical Oncology and reported by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommend adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with LN metastasis (stage III) and for selected patients without LN metastasis (stage II) with adverse prognostic features, such as T4 tumor, tumor perforation, bowel obstruction, lymph/vascular or perineural invasion by tumor cells, positive margins, poorly differentiated histology, and a number of examined lymph nodes (NELN) less than 12.[4–7]

Several observational studies [8–10] have found that increased survival is associated with the evaluation of an adequate number of LNs (≥ 12). However, a population-based analysis found that only 37% of patients with colon cancer receive adequate lymph node assessment.[11] This may result in understaging and inappropriate treatment. To provide a more accurate nodal staging system than the pN stage of TNM, other parameters have been proposed and investigated. Lymph Node Ratio (LNR) is the ratio of metastatic to examined lymph nodes and appears less influenced by the total number of retrieved nodes.[12]

However, in LN-negative patients, it does not provide more meaningful prognostic evaluation than TNM, because LNR0 is the same as pN0 classification: therefore, N0 patients could not benefit from the ratio-based classification system. Recent studies have suggested the use of metastatic LNR as a prognostic factor in Stage III CRC and some studies have indicated its superiority to the AJCC/UICC N grade.[12–13] Log odds of positive nodes (LODDS), defined as the log of the ratio between the number of positive nodes and the number of negative nodes, has been recently introduced as a tool in predicting prognosis. Until now, only four studies have evaluated the role of LODDS as a prognostic factor for CRC patients.[14–17]

On the basis of this background, this study was conducted and aimed at establishing the effectiveness, as well as the prognostic value, of LODDS in predicting the survival outcome of CRC patients undergoing surgical resection at our Department.

Methods

Overall, we identified 540 CRC patients who had undergone colon or rectal surgery at our Department of Surgery at the Regina Apostolorum Hospital of Albano Laziale (Rome) between October 2010 and December 2015. The study population was represented by 323 consecutive patients with histologically documented primary colon or rectal adenocarcinoma who underwent curative resection. Exclusion criteria were peritoneal dissemination, positive surgical margins, presence of cancer in another organ at the time of surgery and inflammatory bowel disease. Data were prospectively collected and retrospectively reviewed.

The standard surgical resection for the primary tumor included the affected segment of bowel, providing distal and proximal margins of 5 cm or more, and performing an en bloc resection of the associated draining lymph nodes to the level of the origin of the primary blood supply. The histopathology examination of the surgical specimen was confirmed by experienced colorectal pathologists at our hospital.

The cancer-specific data assessed for each patient were clinical, pathological, and surgical variables. The database included the following information: age, gender, tumor site, tumor size, grading, TNM staging, total number of lymph nodes, pT stage, pN stage, pathological prognostic features of the tumor, LNR classification, LODDS classification, adjuvant therapy, postoperative complications and recurrence. Tumor stage and important pathological features of the tumor were determined according to the Tumor Node Metastasis classification system of the AJCC/UICC. Lymph node dissection was considered adequate when at least 12 lymph nodes were examined.[3, 18–19]

For comparative purposes, we classified lymph node status by UICC/AJCC TNM (7th edition), LNR, and LODDS. The LNR was defined as the ratio between the number of positive lymph nodes and the NELN. We chose an LNR system of classification based on the review of previous literature in which patients were divided into three groups: LNR0 (≤ 0.05), LNR1 (> 0.05 ≤ 0.20) and LNR2 (> 0.20). This classification system was considered optimal by the literature.15 The LODDS value identifies the probability of a lymph node being positive when one lymph node is examined. LODDS value was calculated by empirical logistic formula: log (pnod + 0.5)/(tnodpnod + 0.5), where pnod is the number of positive nodes and tnod is the total number of examined nodes, and 0.5 is added to both the numerator and the denominator to avoid an infinite number. Afterwards, patients were divided according to LODDS values, in the following three categories: LODDS0 (≤ −1.36), LODDS1 (> −1.36 ≤ −0.53) and LODDS2 (> −0.53). In order to standardize the procedure and the evaluation, we employed the same cut-off points previously found to be significant to survival in a large population-based study.[15–16]

After discharge, patients were followed up at regular intervals either by clinical examination or by contacting their General Practitioner and Oncologist, to obtain information about progression of disease or cancer death. Local recurrence or distant metastasis was diagnosed by histological or imaging studies. The median follow-up time of the surviving patients was 38 months (range 6–67). The follow-up was conducted until July 2016 and there were no patients lost at follow-up.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical end point of the analyses was OS from the date of surgery. The group distributions for each clinicopathologic trait were compared using the two-tailed Fisher’s exact procedure and the chi-test. Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Survival was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and differences were assessed by means of the log-rank test. Survival was defined as the time from diagnosis to disease-related death and was censored at the last follow-up date if no events had occurred. Hazard ratio for continuous variables were calculated by univariate Cox regression. Multivariate analysis was performed with all variables with a P value of < 0.05 in univariate analysis; in multivariate analyses, Cox’s proportional-hazard model was used to identify the factors with a statistically significant influence on survival. In order to avoid collinearity and to reduce the interference analysis within the same multivariate model, pN stage, LODDS, and LNR were performed in three different models (Model A, B, C). The intent was to study these three parameters separately.

The accuracy of the prognosis assessment of each staging method was compared using the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and the area under the curve (AUC). Values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (22nd edition) software for Mac (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

A total of 323 CRC patients who underwent curative-intent surgery were identified and enrolled in this study. The patient population was composed of 172 men (53.3 %) and 151 women (46.7 %). The mean age at tumor resection was 72±11.2 years (range 20–94). The majority of cancer localization was in the right colon (43.7%), then in the rectum (32.5%), and lastly, in the left colon (23.8%). The mean operative time was 128 minutes (range 35–310) and 52.9% of patients had an operative time (skin to skin) of < 125 minutes.

Out of 41 patients, 25 patients were diagnosed with rectal cancer and underwent neoadjuvant therapy. The positive LNs, LNR and LODDS were 6.2±6.7 (range 1–38), 0.12±0.22 (range 0–0.95), −1.06±0.7 (range −1.91–1.14), respectively. Metastasis most frequently occurred in the liver (10.2%), followed by lung metastasis (2.8%); the other metastatic site was local, distant LNs, brain and peritoneal.

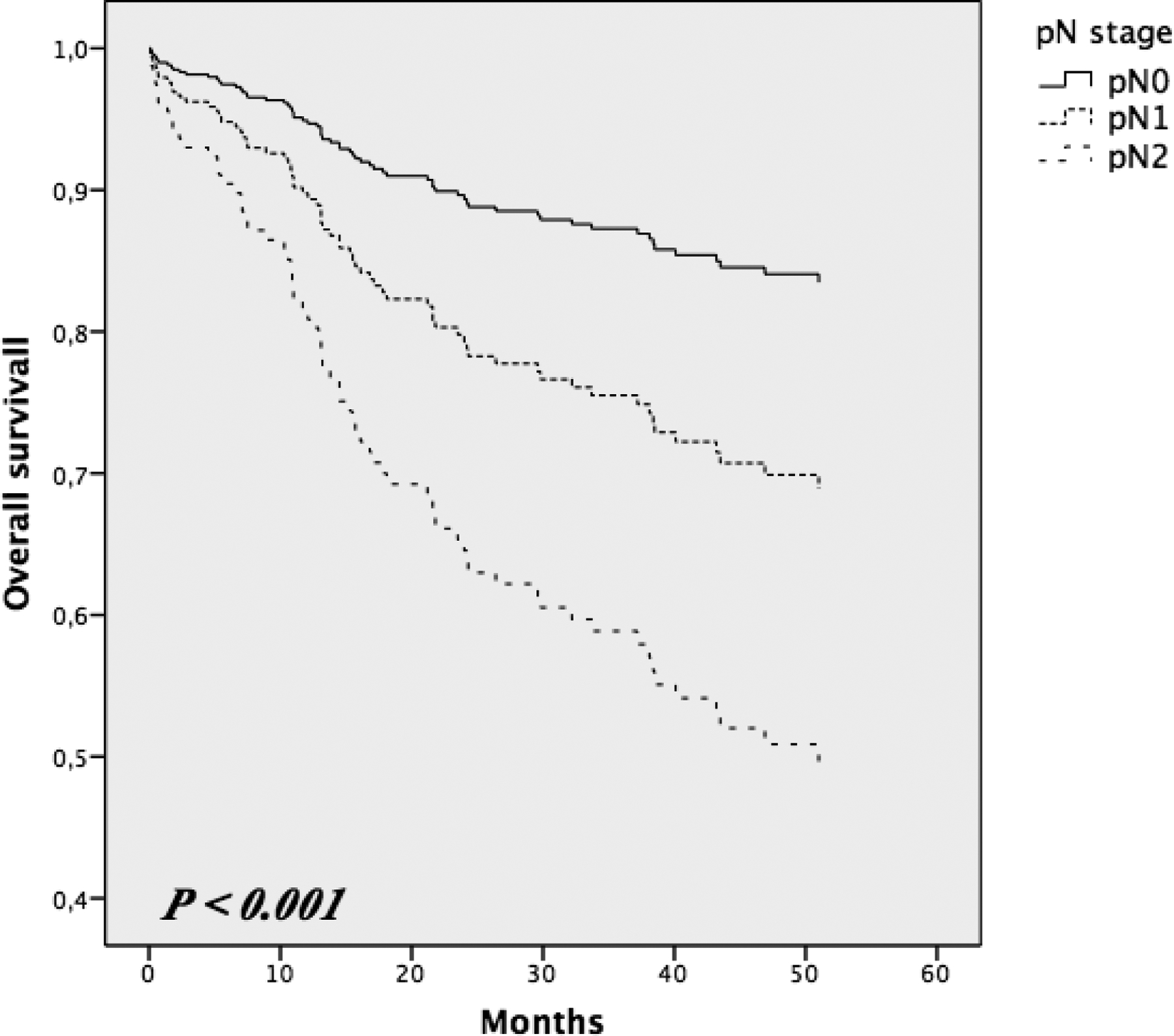

The 1-year and 3-year OS was 90.8% and 78.5%, respectively, for all 323 CRC patients enrolled. The demographic, clinical and histopathological characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Kaplan-Maier curve analyses showed 3-year OS rates of the patients staged by pN stage. The values were 87% for pN0, 72.2 for pN1 and 61.7 for pN2 (P = < 0.001; fig. 1); by LODDS classification were 88.3% for LODDS0, 74.8% for LODDS1, and 61.8% for LODDS2 (P = < 0.001; fig. 2). Three-year OS rates for the different LNR groups were 87.3%, 66.3% and 62.5% (P = < 0.001) for LNR0 (203patients), LNR1 (48 patients) and LNR2 (72 patients), respectively. Moreover, all pN0 patients included in the LODDS0 category had at least 19 lymph nodes retrieved. Whereas, all of the pN0 patients included in the LODDS1 and LODDS2 categories had a mean of 11 retrieved lymph nodes (Table 2). The LODDS was significantly correlated with the number of positive lymph nodes (P = 0.038) and the NELN (P = < 0.001). Table 3 shows the 3-year overall survival on the basis of LNR according to LODDS classification; there was no statistically significant difference encountered.

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic data, observed 3-year survival rate, and univariate analysis of CRC patients undergo to curative resection

| Variable | n (%) | 3 yrs OS (%) | Exp(B) | 95% C.I. | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 151 (46.7) | 77.6 | |||

| 65 yr | 248 (76.8) | 76.3 | |||

| Laparoscopic | 248 (76.8) | 86.4 | |||

| IV | 61 (18.9) | 51.5 | |||

| pT4 | 55 (17.0) | 56.0 | |||

| pN2 | 76 (23.5) | 61.7 | |||

| LNR2 | 72 (22.3) | 62.5 | |||

| LODDS2 | 73 (22.6) | 61.8 | |||

| Positive | 7 (2.2) | 26.8 | |||

| Positive | 23 (7.1) | 21.5 | |||

| 3.5 cm | 83 (25.7) | 88.4 | |||

| G3 | 41 (12.7) | 65.9 | |||

| Positive | 23 (7.1) | 59.1 | |||

| Yes | 164 (50.8) | 70.8 | |||

| Yes | 42 (13.0) | 37.7 |

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Maier curves of overall survival in pN stage groups

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Maier curves of overall survival in LODDS groups

Table 2.

Three-year overall survival on the basis of pN stage according to LODDS classification

| LODDS0 | LODDS1 | LODDS2 | P* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | 3 yrs OS (%) | n (%) | 3 yrs OS (%) | n (%) | 3 yrs OS (%) | ||

| N2 | 0 (0) | - | 16 (5.0) | 45.3 | 60 (18.5) | 63.6 | 0.556 |

| P§ | - | 0.059 | 0.996 | ||||

Comparison of the survival rates between different LODDS groups;

Comparison of the survival rates between different pN groups.

Table 3.

Three-year overall survival on the basis of LNR according to LODDS classification

| LODDS0 | LODDS1 | LODDS2 | P* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | 3 yrs OS (%) | n (%) | 3 yrs OS (%) | n (%) | 3 yrs OS (%) | ||

| 2 | 0 (0) | - | 2 (0.6) | 50.0 | 70 (21.7) | 62.2 | 0.589 |

| P§ | - | 0.294 | 0.480 | ||||

Comparison of the survival rates between different LODDS groups;

Comparison of the survival rates between different LNR groups.

The univariate Cox proportional hazards model identified thirteen variables associated with survival that were statistically significant: type of surgery, TNM staging, pT stage, pN stage, LNR, LODDS, perineural invasion, microvascular invasion, radial tumor margin, tumor grade, postoperative complication, adjuvant chemotherapy and recurrence (Tab. 1). The factors identified as statistically significant in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis. In the later analysis (Tab. 4), the variables which included type of surgery, microvascular invasion, LODDS, postoperative complication and recurrence were demonstrated as independent prognostic factors of OS. In order to avoid collinearity and reduce the interference during analysis within the same multivariate model, pN Stage, LODDS and LNR, we performed three different models (Model, A, B, C) using the Cox Proportional Hazard method. The intent was to study these parameters separately. The results demonstrated that only LODDS was an independent prognostic factor for survival compared to pN Stage and LNR.

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis with Cox Proportional Hazard method (in Model A, B, C, LODDS, LNR and pN Stage are represented separately to analyze significance avoiding collinearity)

| VARIABLES | P | Exp(B) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of surgery | 0,009 | 0,394 | 0,197–0,790 |

| pT stage | 0,205 | 1,490 | 0,804–2,762 |

| Perineural invasion | 0,086 | 2,858 | 0,861–9,493 |

| Microvascular invasion | 0,016 | 2,773 | 1,209–6,363 |

| Radial tumor margin | 0,856 | 1,045 | 0,651–1,676 |

| Tumor grading | 0,074 | 0,554 | 0,290–1,058 |

| Postoperative complication | < 0,001 | 11,072 | 4,672–26,241 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 0,123 | 0,466 | 0,176–1,230 |

| Recurrence | < 0,001 | 7,144 | 4,048–12,610 |

| LNR | |||

| LODDS | |||

| pN stage |

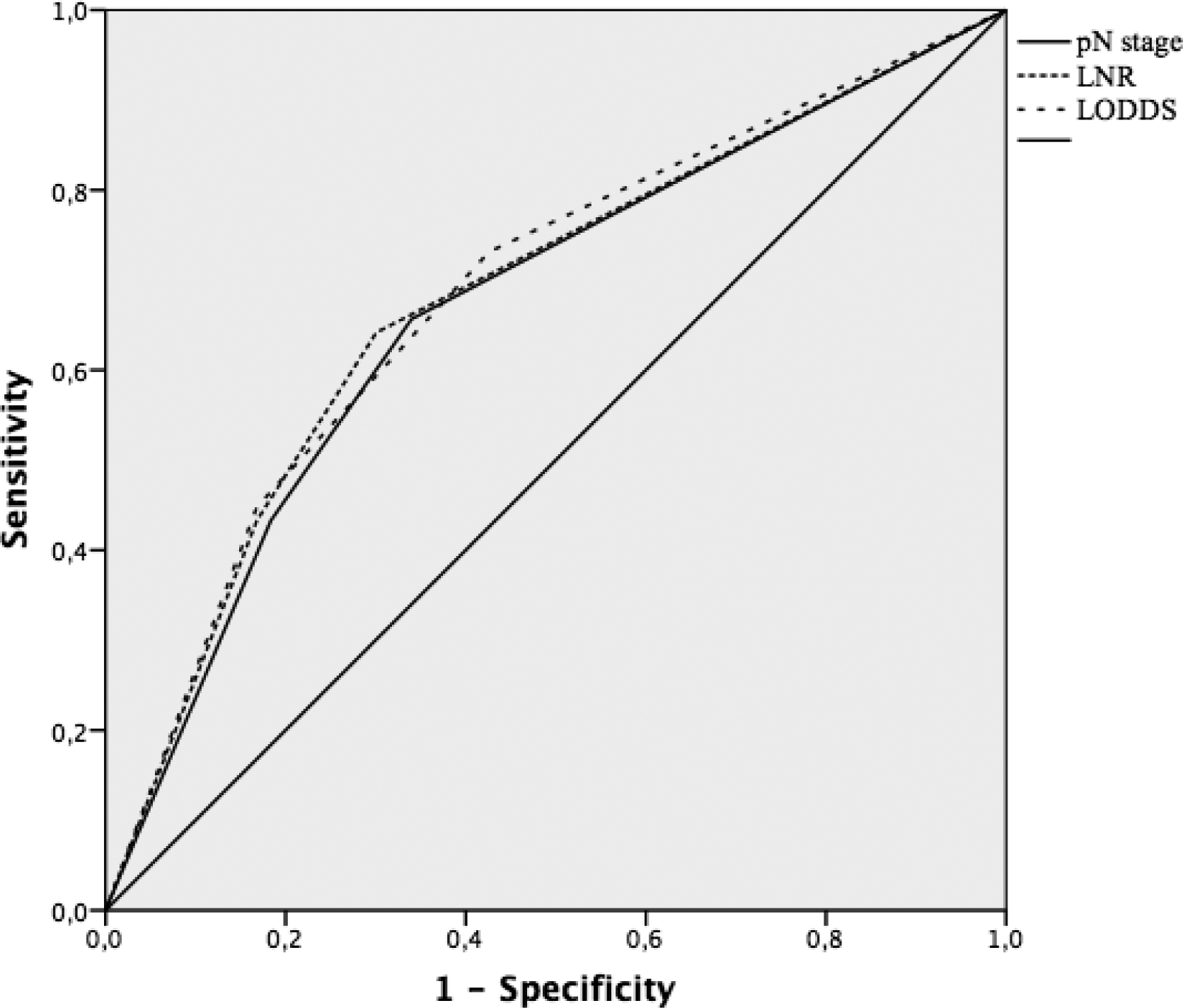

Furthermore, we performed the ROC curve (Fig.3) to compare the accuracy of three staging methods in the prognostic assessment of CRC patients. The corresponding AUC for pN stage, LNR and LODDS was 0.67 (95% CI 0.59–0.74), 0.68 (95% CI 0.61–0.75) and 0.69 (95% CI 0.62–0.76), respectively, with significant difference (P < 0.001). ROC analyses showed LODDS predicted OS better than LNR.

Fig. 3.

ROC curves comparison of pN stage, LNR and LODDS

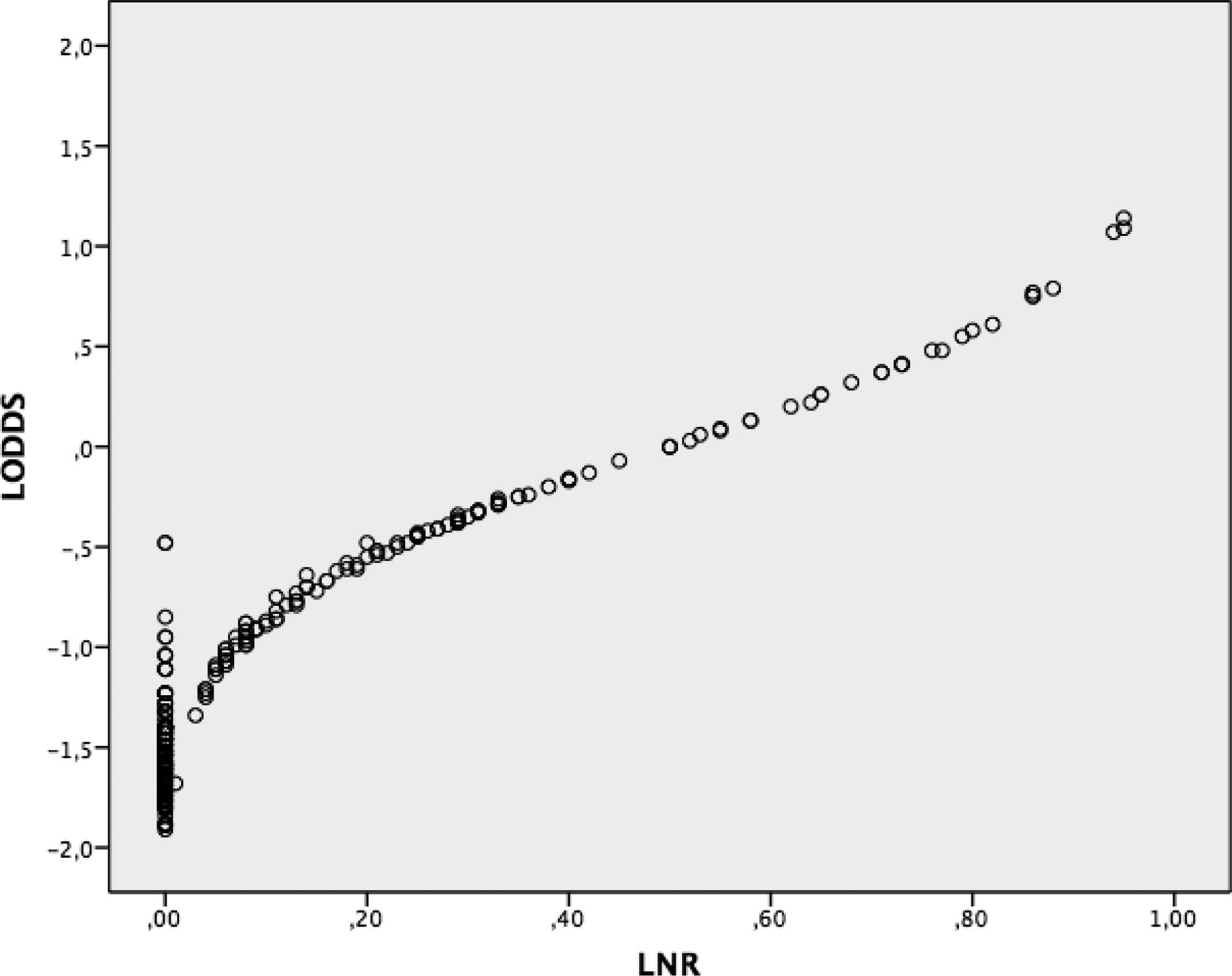

Moreover, we plotted scatter plots to demonstrate the theoretical superiority of LODDS compared to pN stage and LNR. As shown in figure 4, the value of LODDS increased with LNR, indicating that there was a close correlation between LODDS and LNR. However, this correlation was not linear. When the LNR was less than 0.2 or more than 0.8, it increased at a slower rate than LODDS. The most interesting result was that when the LNR was 0 or 1, the value of LODDS was still heterogeneous, indicating that the LODDS system has the potential to discriminate among patients with the same LNR with different prognoses, especially for those whose LNR was 0 and 1.

Fig. 4.

Scatter plot of relationship between LODDS and LNR

Discussion

LNs status is one of the most important factor for OS in CRC patients. Several studies have demonstrated that the involvement of LNs have a strong impact on patient survival. In previous studies on LNR, some authors proposed that LNR had a more precise and apposite prognostic value than pN stage in patients with resected gastric cancer.[20–21]

In the last two decades, LODDS is becoming an important factor in tumor staging, after recognizing the prognostic factor of LNR. The literature regarding the prognostic significance of LODDS remains scarce. Several studies have shown how a novel LN classification method, such as the LODDS, has a strong prognostic ability in patients undergoing surgery for breast cancer and how this parameter can be a complement to the nodal staging in current use. In a retrospective study, Wang et al. enrolled more than of 24,000 patients with stage III colon cancer and demonstrated, the prognostic superiority of LODDS in this specific group of colon cancer patients and suggested that the current AJCC stage III is an unacceptable staging tool in terms of prognosis accuracy.[14] Persiani et al. found that LODDS system was a highly reliable staging system with strong predictive proficiency for patient outcome and compared with other nodal staging systems, the prognostic power of LODDS was less influenced by NELN.[16] Similarly, in gastric cancer patients, authors also found that LODDS showed a prognostic superiority as compared to LNR.[22–23]

The current study demonstrated that LODDS outmatched the conventional UICC/AJCC pN stage and LNR for prognosis.

Indeed, LODDS showed greater prognostic significance when compared to NELN. Moreover, this data further supports the literature regarding the clinical relevance of LODDS stratification on OS, more than that of LNR classification. We found that LODDS could plot survival differences in LNR groups. Furthermore, our data showed that LODDS allows a better stratification of all high-risk CRC patients who otherwise were classified in low-risk groups by other classification methods. This suggest that LODDS may detect some LN characteristics missed when other lymph node classification is used, suggesting that LODDS may be more useful. The results demonstrated that LODDS is an independent prognostic factor of survival, unlike TNM staging and LNR, which is similar to the literature throughout different surgical fields. In patients in which the number of LNs removed was equal to the number of positive LNs, for example LNR1, or in cases with negative LNs, LNR is not able to stratify the sample and there is risk of “migration stage”. This is because LODDS uses a mathematical approach to stage lymph nodes, which takes into account the number of negative LNs and it is not influenced by the extent of lymphadenectomy; therefore, unlike pN stage and LNR, LODDS represents the probability of an examined LN to be metastatic. In our study, as shown in Figure 1, 3-year OS decreases with increasing LODDS results: 85.1% in LODDS0, 72.8% in LODDS1 and 47, 1% LODDS2 groups. In multivariate analysis, the statistical significance of this variable provides the LODDS ability to affect the patient’s prognosis. Therefore, LODDS is an independent prognostic factor of 3-year OS, in contrast to pN stage and LNR which shows no statistical significance (Table 4).

In conclusion, our study stressed that LODDS classification has a better prognostic effect than pN stage and LNR. It is clear that LODDS offers a finer stratification and accurately predicts survival of CRC patients. Therefore, LODDS is a useful and scientifically strong tool to evaluate LN dissection, pathological examination and to consider ratio-based prognostic factors into the staging system of CRC patients. Moreover, it may be useful, as a more accurate stratification tool for use in clinical studies and in evaluating the appropriateness of chemotherapy treatment in homogenous patient groups. Larger cohort studies are needed to understand if it could be superior to pN stage and LNR in prognostic evaluation of patient subgroups and prior to the recommendation for its practical use.

Informed consent:

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the Updates in Surgery.

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, et al. (2010) Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 60:277–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson H, Petrelli N, Carlin A et al. (2001) Guidelines 2000 for colon and rectal cancer surgery. J Natl Cancer Inst 93:583–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sobin LH, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind C. (2010) TNM classification of malignant tumors. 7th edition. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Compton C, Fenoglio-Preiser CM, Pettigrew N, et al. (2000) Colorectal Working Group. American Joint Committee on Cancer prognostic factors consensus conference. Cancer 88:1739–1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Engstrom PF, Benson AB 3rd, Chen YJ et al. (2005) Colon cancer clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 3:468–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Clinical practice guidelines in oncology (NCCN Guidelines TM). Colon Cancer. Version 3.2011. Available at http://www.nccn.org.

- 7.Stocchi L, Fazio VW, Lavery I, et al. (2011) Individual surgeon, pathologist, and other factors affecting lymph node harvest in stage II colon carcinoma. Is a minimum of 12 examined lymph nodes sufficient? Ann Surg Oncol 2 18:405–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldstein NS. (2002) Lymph node recoveries from 2427 pT3 colorectal resec- tion specimens spanning 45 years: recommendations for a minimum number of recovered lymph nodes based on predictive probabilities. Am J Surg Pathol 26:179–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sarli L, Bader G, Iusco D et al. (2005) Number of lymph nodes examined and prognosis of TNM stage II colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer 41:272–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swanson RS, Compton CC, Stewart A et al. (2003) The prognosis of T3N0 colon cancer is dependent on the number of lymph nodes exam- ined. Ann Surg Oncol 10:65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baxter NN, Virnig DJ, Rothenberger DA et al. (2005) Lymph node evaluation in colorectal cancer patients: a population-based study. J Natl Cancer Inst 97:219–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu YJ, Lin PC, Lin CC, et al. (2013) The impact of the lymph node ratio is greater than traditional lymph node status in stage III colorectal cancer patients. World J Surg 37:1927–1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenberg R, Friederichs J, Schuster T, et al. (2008) Prognosis of patients with colorectal cancer is associated with lymph node ratio: A single-center analysis of 3,026 patients over a 25-year time period. Ann Surg 248:968–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang J, Hassett JM, Dayton MT, et al. (2008) The prognostic superiority of log odds of positive lymph nodes in stage III colon cancer. J Gastrointest Surg 12:1790–1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arslan NC, Sokmen S, Canda AE, et al. (2014) The prognostic impact of log odds of positive lymph nodes in colon cancer. Colorectal Dis 16(11):O386–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Persiani R, Cananzi FC, Biondi A, et al. (2012) Log odds of positive lymph nodes in colon cancer: A meaningful ratio-based lymph node classification system. World J Surg March;36:667–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song YX, Gao P, Wang ZN et al. (2011) Which is the most suitable classification for colorectal cancer, log odds, the number or the ratio of positive lymph nodes? PLoS One 6(12):e28937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Compton CC, Fielding LP, Burgart LJ et al. (2000) Prognostic factors in colorectal cancer. College of American Pathologists Consensus Statement 1999. Arch Pathol Lab Med 124:979–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC et al. (2010) AJCC cancer staging manual, 7th ed. Springer, New York. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okusa T, Nakane Y, Boku T et al. (1990) Quantitative analysis of nodal involvement with respect to survival rate after curative gastrectomy for carcinoma. Surg Gynecol Obstet. June;170(6):488–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Siewert JR, Bottcher K, Stein HJ et al. (1998) Relevant prognostic factors in gastric cancer: ten-year results of the German Gastric Cancer Study. Ann Surg. October;228(4):449–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aurello P, Petrucciani N, Nigri GR et al. (2014) Log odds of positive lymph nodes (LODDS): what are their role in the prognostic assessment of gastric adenocarcinoma? J Gastrointest Surg. July;18(7):1254–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun Z, Xu Y, Li de M et al. (2010) Log odds of positive lymph nodes: a novel prognostic indicator superior to the number-based and the ratio-based N category for gastric cancer patients with R0 resection. Cancer. June 1;116(11):2571–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]