Abstract

Background:

Bi/multiracial youth face higher risk of engaging in substance use than most monoracial youth.

Objectives:

This study contrasts the prevalence of substance use among bi/multiracial youth with that of youth from other racial/ethnic groups, and identifies distinct profiles of bi/multiracial youth by examining their substance use risk.

Methods:

Using data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (collected between 2002 and 2014), we analyze data for 9,339 bi/multiracial youth ages 12 to 17 living in the United States. Analyses use multinomial regression and latent class analysis.

Results:

With few exceptions, bi/multiracial youth in general report higher levels of tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, and other illicit drug use compared to other youth of color. Bi/multiracial youth also report higher levels of marijuana use compared to non-Hispanic white adolescents. However, latent class modeling also revealed that a majority (54%) of bi/multiracial youth experience high levels of psychosocial protection (i.e., strong antidrug views and elevated parental engagement) and low levels of psychosocial risk (i.e., low peer substance use, school-related problems, and social-environmental risk), and report very low levels of substance use. Substance use was found to be particularly elevated among a minority of bi/multiracial youth (28%) reporting elevated psychosocial risk and low levels of protection. Bi/multiracial youth characterized by both elevated psychosocial risk and elevated psychosocial protection (22%) reported significantly elevated substance use as well.

Conclusions:

While bi/multiracial youth in general exhibit elevated levels of substance use, substantial heterogeneity exists among this rapidly-growing demographic.

Keywords: alcohol and drug abuse, bi/multiracial youth, risk and protective factors, adolescents, substance use

Bi/multiracial youth are individuals younger than 18 years who identify as having two [i.e., biracial] or three or more [i.e., multiracial] racial/ethnic backgrounds. There exists substantial confusion in the literature regarding the use of the term “multiracial.” In some instances, this term is used to apply to individuals who identify with more than one racial and/or ethnic group (e.g., African American and Hispanic). Others use the term specifically in reference to individuals identifying with more than one race (e.g., African American and Asian). Moreover, some scholars include biracial individuals (i.e., those who identify with two racial groups) under the umbrella of the multiracial category, whereas others clearly distinguish between the biracial and multiracial (i.e., those who identify with three or more racial groups) categories. Given this confusion, and the nature of the data used in the present study, we utilize the more inclusive term of bi/multiracial by including youth identifying with two or three or more racial and ethnic groups into a singular category.

Bi/multiracial youth comprise the fastest growing racial youth group in the United States (Pew Research Center, 2015). Between 2000 and 2010, the U.S. bi/multiracial population grew from 6.8 million to 9 million people, an increase of approximately 32% (Humes, Jones, & Ramirez, 2011; Jones & Bullock, 2012). The bi/multiracial population now represents 2.9% of the U.S. population (Jones & Bullock, 2012) and is expected to triple by 2050 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2008), which will translate to 1 of every 5 Americans identifying as bi/multiracial (Lee & Bean, 2004; Smith & Edmonston, 1997).

Many recent studies have examined substance use among bi/multiracial youth in comparison with youth from other racial/ethnic groups and the general population. Such research suggests that, as compared with most monoracial youth, bi/multiracial youth are at higher risk of engaging in substance use and other risky behaviors (Choi, Harachi, Gillmore, & Catalano, 2006; Udry, Li, & Hendrickson-Smith, 2003). For example, a 2013 comparison by racial/ethnic group of the rates of current illicit drug use among those 12 years older indicated a rate of 3.1% among Asians, 8.8% among Hispanics, 9.5% among Whites, 10.5% among Blacks, 12.3% among American Indians or Alaska Natives, 14% among Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders, and 17.4% among the bi/multiracial population.

Bi/multiracial youth may be at elevated risk for engaging in substance use for various reasons. For instance, in one study, with a large youth sample that included 225 bi/multiracial youth, the bi/multiracial youth reported higher levels of socioeconomic disadvantage, single-parent household status, peer substance use, and antisocial friends as compared with the monoracial youth; these findings partially explained the higher rates of substance use found among bi/multiracial youth (Choi et al., 2012). Bi/multiracial youth may also use substances to cope with stressors such as peer rejection (Funderburg, 1994) and an unsupportive family (Jackson & LeCroy, 2009).

Recent research has advanced the understanding of substance use risk among bi/multiracial youth. However, most prior studies share a common shortcoming of being rooted in the de facto assumption that bi/multiracial youth are a homogeneous group. This is critical for a number of reasons. First, the assumption of homogeneity runs contrary to an emerging body of research that has pointed to the fundamental asymmetry in youth risk behaviors, including substance use (Clark, Corneille, & Coman, 2013; Clark, Nguyen, & Kropko, 2013). Although scholars often speak of racial/ethnic groups in broad terms, again and again we see evidence that heterogeneity is the norm (Clark, Salas-Wright, Vaughn, & Whitfield, 2015). Second, bi/multiracial youth are, by definition, a diverse and heterogeneous group, even with respect to the defining characteristics of group membership. As such, it is simply reasonable to suspect that distinct and substantively meaningful subgroups of bi/multiracial youth exist.

The Present Study

The present study aimed to address the aforementioned gaps by using data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), which is a population-based study of adolescents living in the United States. To begin, we compare the prevalence of alcohol and illicit drug use among bi/multiracial youth with that of youth from other racial/ethnic categories. While the focus of the study is primarily on heterogeneity within bi/multiracial youth, this basic group-level analysis was conducted in order to provide background context to be used in order to interpret the modeling of heterogeneity among bi/multiracial youth. Next, we conducted a person-centered analysis (i.e., latent class analysis) to identify subgroups of bi/multiracial youth based on risk and protective factors associated with the likelihood of substance use during adolescence. In turn, we examined the relationship between membership in the identified latent subgroups and the risk of past-month and past-year tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, and other illicit drug use. Simply, our objective was to move beyond the de facto assumption that bi/multiracial youth are a homogenous group by first identifying distinct profiles of bi/multiracial youth and then systematically examining substance-use risk among the subgroups that make up this rapidly-growing and understudied population.

Method

This study used public use NSDUH data. All public use NSDUH data are de-identified by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAHMSA); as such, this study was considered exempt from institutional review board (IRB) review at the lead author’s home institution. However, the NSDUH study was reviewed, following guidelines from the US Department of Health and Human Service’s Office for Human Research Protections, by RTI International’s IRB (SAMHSA, 2016). Informed consent and assent were given by study participants.

Sample

The current study examined public-use data collected between 2002 and 2014 as part of the NSDUH. The NSDUH provides population estimates for an array of substance use and health-related behaviors in the US general population. NSDUH participants included household residents, civilians residing on military bases, and residents of shelters and group homes. The NSDUH design and methods are briefly summarized here; however, a detailed description has been published elsewhere (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration, 2014, 2016). In all, 723,283 respondents have completed the NSDUH since 2002. The current study restricted analyses to NSDUH adolescent respondents between the ages of 12 and 17 (n = 230,452).

Measures

Substance Use.

We examined past 30-day and past 12-month use of tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, and illicit drugs other than marijuana. For each of these items, youth reporting one or more instances of use were coded as 1 and all others coded as 0.

Risk factors.

Peer substance use.

Youth were asked three questions relating to peer substance use, including “How many of the students in your grade at school would you say smoke cigarettes?” Identical questions were asked regarding use of “marijuana or hashish” and drinking “alcoholic beverages.” Consistent with the NSDUH codebook, responses were coded dichotomously, with none of them/a few of them coded as 0 and most of them/all of them coded as 1.

School difficulty.

We examined three variables related to school difficulty: negative views toward school, academic difficulty, and truancy. The negative views variable was based on the question, “Which of the statements below best describes how you felt overall about going to school during the past 12 months?” Consistent with the NSDUH codebook, responses of liked/ kind of liked going were coded 0 and didn’t like/hated going were coded 1. Academic difficulty was based on youth self-reports of their grades for the last grading period with responses of A/B average coded 0 and C/D average coded 1. Truancy was based on the question, “During the past 30 days, how many whole days did you miss school because you skipped or ‘cut’ or just didn’t want to be there?” Consistent with recent NSDUH-based studies (Maynard, Salas-Wright, Vaughn, & Peters, 2012), youth reporting one or more instances of truancy were coded as 1 and all other youth were coded 0.

Social environment.

We examined three variables related to social environmental risk: residential instability, easy drug access, and exposure to drug offers. Residential instability was based on youth self-reports of the frequency of moves over the past 5 years. Consistent with research on residential instability (see Ziol-Guest & McKenna, 2009), responses of zero or one-to-two times were coded 0 and three or more times were coded 1. Drug access was based on the question, “How difficult or easy would it be for you to get some marijuana, if you wanted some?” Responses indicating difficulty (i.e., probably impossible/very difficult/fairly difficult ) were coded 0 whereas responses of fairly easy/very easy were coded 1. Drug offers was based on the yes/no question, “In the past 30 days, has anyone approached you to sell you an illegal drug?” Affirmative responses were coded as 1 and negative responses were coded as 0.

Protective Factors

Substance use views.

Two sets of questions examined youth disapproval and perceived risk related to use of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana. Substance use disapproval was measured by the question, “How do you feel about someone your age smoking one or more packs of cigarettes a day?” Similarly worded questions were asked for “trying marijuana or hashish once or twice” and “having one or two drinks of an alcoholic beverage nearly every day.” For each item, response options of neither approve nor disapprove / somewhat disapprove were coded 0 and strongly disapprove was coded 1. The variable for perceived risk was measured via the question, “How much do people risk harming themselves physically and in other ways when they smoke one or more packs of cigarettes per day?” Similarly worded questions were asked for having “four or five drinks of an alcoholic beverage once or twice a week” and smoking “marijuana once a month.” For each item, response options of no risk/slight risk/moderate risk were coded 0 and responses of great risk were coded 1. Our coding approach is consistent with recent research highlighting the importance of unequivocal views related to adolescent substance use (Salas-Wright, Vaughn, Todic, Córdova, & Perron, 2015).

Parental engagement.

We examined three variables in the parental domain: parental conflict, parental limit setting, and parental discussions of the dangers of substance use. Limited parental conflict was based on the question, “During the past 12 months, how many times have you argued or had a fight with at least one of your parents?” Respondents reporting no conflict or one to two instances of conflict were coded as 1 and youth reporting more frequent conflict (i.e., 3 to 5 times or more) were coded as 0. Consistent parental limit setting was based on the question, “During the past 12 months, how often did your parents limit the amount of time you went out with friends on school nights?” Responses of never/seldom/sometimes were coded as 0 and responses of always were coded as 1. Parental discussion of the dangers of substance use was based on the yes/no question, “During the past 12 months, have you talked with at least one of your parents about the dangers of tobacco, alcohol, or drug use?” Responses indicating no parental discussions (i.e., no) were coded as 0 and responses affirming youth had spoken with their parents (yes) were coded as 1.

Sociodemographic factors.

The sociodemographic characteristics included age group (12–14, 15–17 years), gender (male, female), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic African American, Hispanic, non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander, and non-Hispanic bi/multiracial [i.e., selected more than one racial identity]), annual household income (less than $20,000, $20,000-$39,999, $40,000-$74,999, and $75,000 or higher), and father in household (yes/ no).

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were carried out in several sequential steps. First, we used multinomial regression to contrast the prevalence of substance use between bi/multiracial youth and youth from other racial and ethnic groups while adjusting for sociodemographic confounds. Next, we conducted a latent class analysis (LCA) with the subsample of bi/multiracial youth (n = 9,339) to identify latent subgroups of youth on the basis of 18 dichotomous variables that tapped risk and protective factors relevant to adolescent substance use. LCA is a statistical procedure—designed for use with categorical data—that assigns subjects or cases to their most likely subgroup based on observed variables. To identify the class solution, we generated a series of latent class models ranging from one to five subgroups using Latent GOLD 5.0 (Vermunt & Magidson, 2013). We used statistical criteria to identify the best fitting model, including log likelihood (LL), the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), Akaike’s information criterion (AIC), consistent Akaike’s information criterion (CAIC), and entropy (McLachlan & Peel, 2004). Equally important, in addition to these statistical criteria, the parsimony and substantive interpretability of latent class solutions are also evaluated in identifying the optimal modeling of the heterogeneity of the data.

After identifying a latent class solution, multinomial regression was used to examine the association between class membership and sociodemographic and substance-use variables. As is customary, the largest class was specified as the reference category. Using multinomial regression, we estimated relative risk ratios (RR) and confidence intervals (CI). Statistical procedures involving multinomial regression models were conducted using Stata 14.1 MP survey data functions, which implements a Taylor series linearization to adjust standard errors of estimates for complex survey sampling design effects, including clustered multistage data (StataCorp, 2015). Given that multiple survey years were combined to increase the analytic sample size, we followed the protocol for pooled data detailed in the NSDUH codebook in generating a new weight variable by dividing the single year person-level sample weight variable (ANALWT_C) by the total number of survey years (13).

Results

Substance Use among Bi/multiracial Youth

Table 1 displays the prevalence of tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, and other illicit drug use by racial/ethnic group, along with relative risk ratios in comparison to bi/multiracial youth. With the exception of alcohol use among Hispanic adolescents, the prevalence of substance use among bi/multiracial youth was significantly greater—controlling for age, gender, family income, and father in household—compared to other youth of color (i.e., African-American, Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander). Moreover, while risk of tobacco and alcohol use was slightly greater among non-Hispanic white youth in comparison to bi/multiracial youth, non-Hispanic white adolescents were at lower risk of reporting past month (RR = 0.79, 95% CI = 0.70–0.89) and past year (RR = 0.81, 95% CI = 0.74–0.90) marijuana use, compared to bi/multiracial youth.

Table 1.

Prevalence of Substance Use among Multiracial and Other Adolescents in the United States

| Non-Hispanic White (n = 138,152) |

African American (n = 31,595) |

Hispanic (n = 39,646) |

Asian/Pacific Islander (n = 8244) |

Multiracial (n = 9339) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) / RR |

95% CI | N (%) / RR |

95% CI | N (%) / RR |

95% CI | N (%) / RR |

95% CI | N (%) / RR |

95% CI | |

| Past Month Use | ||||||||||

| Tobacco | 20,074 (14.28) |

14.0–14.5 | 2430 (7.17) |

6.8–7.5 | 3800 (8.34) |

7.9–8.7 | 453 (4.17) |

3.7–4.7 | 1280 (12.02) |

11.0–13.1 |

| Relative Risk | 1.31 | 1.18–1.46 | 0.44 | 0.40–0.50 | 0.60 | 0.54–0.68 | 0.32 | 0.26–0.38 | 1.00 | -- |

| Alcohol | 23,961 (17.07) |

16.8–17.3 | 3433 (10.26) |

9.8–10.7 | 6090 (14.27) |

13.8–14.7 | 709 (7.44) |

6.8–8.1 | 1456 (13.46) |

12.5–14.5 |

| Relative Risk | 1.32 | 1.21–1.45 | 0.67 | 0.61–0.74 | 1.10 | 0.99–1.21 | 0.50 | 0.43–0.58 | 1.00 | -- |

| Marijuana | 10,897 (7.77) |

7.6–8.0 | 2356 (6.81) |

6.5–7.2 | 2985 (6.83) |

6.5–7.1 | 314 (3.11) |

2.7–3.6 | 398 (9.73) |

8.8–10.8 |

| Relative Risk | 0.79 | 0.70–0.89 | 0.56 | 0.50–0.64 | 0.65 | 0.57–0.74 | 0.30 | 0.24–0.36 | 1.00 | -- |

| Other Illicit Drugs | 6578 (4.77) |

4.6–4.9 | 1327 (4.02) |

3.8–4.3 | 1914 (4.59) |

4.3–4.9 | 262 (2.69) |

2.2–3.2 | 533 (5.36) |

4.7–6.1 |

| Relative Risk | 0.95 | 0.82–1.11 | 0.64 | 0.54–0.75 | 0.82 | 0.68–0.97 | 0.51 | 0.40–0.66 | 1.00 | -- |

| Past Year Use | ||||||||||

| Tobacco | 31,314 (22.34) |

22.0–22.6 | 4159 (12.40) |

12.0–12.9 | 6906 (16.03) |

15.5–16.6 | 793 (7.99) |

7.2–8.9 | 1996 (19.23) |

18.0–20.6 |

| Relative Risk | 1.28 | 1.17–1.40 | 0.48 | 0.44–0.53 | 0.75 | 0.68–0.82 | 0.35 | 0.30–0.41 | 1.00 | -- |

| Alcohol | 46,445 (33.25) |

32.9–33.5 | 7723 (23.5) |

22.9–24.1 | 12,470 (30.04) |

29.5–30.6 | 1664 (17.83) |

16.8–18.9 | 2994 (29.29) |

27.9–30.7 |

| Relative Risk | 1.20 | 1.11–1.30 | 0.66 | 0.61–0.72 | 1.06 | 0.98–1.15 | 0.48 | 0.43–0.53 | 1.00 | -- |

| Marijuana | 20,366 (14.63) |

14.4–14.8 | 4339 (12.77) |

12.3–13.2 | 5702 (13.39) |

12.9–13.8 | 630 (16.18) |

5.6–6.8 | 1684 (17.38) |

15.2–18.7 |

| Relative Risk | 0.81 | 0.74–0.90 | 0.58 | 0.52–0.64 | 0.70 | 0.63–0.78 | 0.30 | 0.26–0.34 | 1.00 | -- |

| Other Illicit Drugs | 16,699 (12.09) |

18.9–12.3 | 2946 (9.04) |

8.6–9.5 | 4749 (11.28) |

10.8–11.8 | 634 (6.58) |

5.9–7.4 | 1300 (13.02) |

11.9–14.2 |

| Relative Risk | 0.97 | 0.87–1.07 | 0.59 | 0.53–0.66 | 0.83 | 0.74–0.92 | 0.49 | 0.42–0.57 | 1.00 | -- |

Note. All percentages are survey adjusted column percentages. Survey adjusted prevalence estimates in bold represent significant (p < .05) differences in relative risk compared with multiracial youth. Significance determined by means of multinomial regression analyses with multiracial youth specified as reference group. Regression analyses were adjusted for age, gender, family income, and father in househol

Identification of Latent Subgroups

An analysis of the latent class models indicated that a three class solution was the optimal modeling of the data on risk and protective factors among bi/multiracial youth (see Table 2). While the LL was greater and the BIC, AIC, and CAIC were lower for the four and five class solutions, the accelerated flattening of the differences in these criteria between the 3, 4, and 5 class solutions suggests that the addition of a fourth or fifth class would not be parsimonious.

Table 2.

Fit Indices for Latent Class Models

| Class Solution | Log Likelihood | BIC | AIC | CAIC | Entropy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Class | −104646.37 | 209459.18 | 209328.74 | 209477.18 | n/a |

| 2 Classes | −96742.60 | 193882.83 | 193571.21 | 193925.83 | .80 |

| 3 Classes | −94767.60 | 190163.99 | 189671.20 | 190231.99 | .79 |

| 4 Classes | −93382.71 | 187625.38 | 186951.43 | 187718.38 | .78 |

| 5 Classes | −92715.22 | 186521.58 | 185666.45 | 186639.58 | .77 |

Note: BIC = Bayesian Information Criterion, AIC = Akaike’s Information Criterion, CAIC = Consistent Akaike’s Information Criterion.

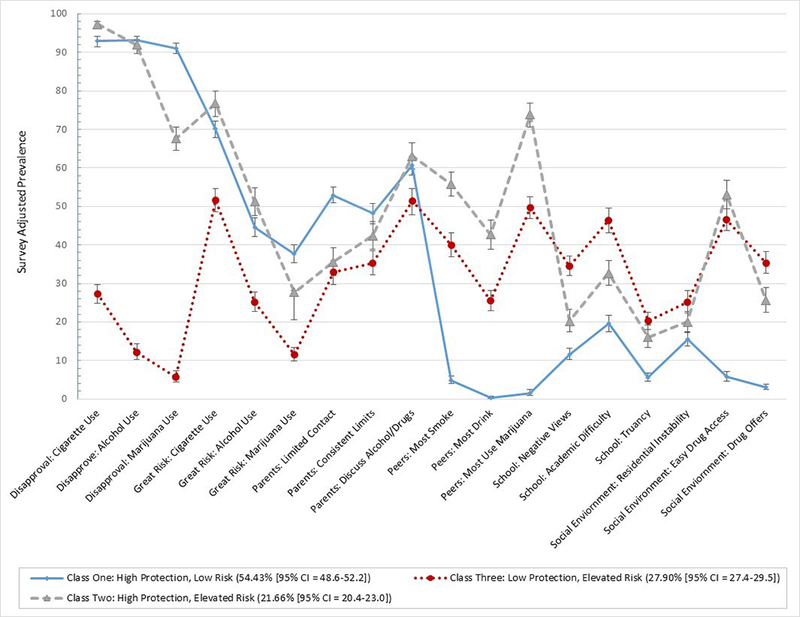

Figure 1 displays the survey adjusted prevalence estimates for each of the three latent classes with respect to risk and protective factors related to substance use. The three class solution is comprised of a “high protection, low risk” class (Class One: 54.43%), a “high protection, elevated risk” class (Class Two: 21.66%), and a “low protection, elevated risk” class (Class Three: 27.90%). These classes are clearly distinguishable from one another and are substantively interpretable. Class One represents just over half of the total sample and is characterized by an elevated proportion of youth endorsing protective factors (i.e., antidrug views and elevated parental engagement) and the near absence of psychosocial risk in the domains of peer substance use, school difficulty, and the social environment. Class Two, which constitutes roughly one in five (23%) bi/multiracial youth, is very similar to Class One with respect to protective factors, but is distinct in the sense that a substantial proportion of youth in this class report psychosocial risk in terms of peer substance use, school difficulty, and the social environment. Class Three, which represents roughly one in four (28%) bi/multiracial youth, is distinct from the first two classes inasmuch as youth in this class report relatively low levels of psychosocial protection in combination with elevated levels of psychosocial risk.

Figure 1.

Latent classes.

Sensitivity Analyses

For purposes of comparison, we also conducted latent class modeling—using the same indicator variables—to examine the size and characteristics of subgroups among non-Hispanic white youth and youth of color. These supplementary analyses yielded comparable results to those for bi/multiracial youth; however, the “high protection, low risk” class was found to be slightly larger among non-Hispanic white youth (56%) than among bi/multiracial youth (54%). Additionally, the “high protection, elevated risk” was found to be smaller among non-Hispanic white youth (17%) and youth of color (19%) as compared to bi/multiracial youth (22%). Notably, the “low protection, elevated risk” class in non-Hispanic white (27%) and youth of color (27%) samples was similarly in size to that of bi/multiracial youth (27%).

These findings support the latent modeling presented for bi/multiracial youth, while also underscoring small but noteworthy differences in relative size of psychosocial profiles between bi/multiracial youth and youth from other racial/ethnic groups. We also conducted supplementary analyses where we specified survey year as an indicator covariate in order to account for any secular changes between 2002 and 2014. These analyses yielded a class modeling that did not differ substantively—in terms of class size or composition—from results presented in Figure 1.

Sociodemographic and Substance Use Characteristics of the Latent Classes

Table 3 displays the sociodemographic characteristics of the bi/multiracial youth in the three latent classes. Clear differences can be observed with respect to age. Youth in Class One are predominately younger adolescents (i.e., ages 12 to 14) as those in Class Two (RR = 13.94, 95% CI = 11.4–17.1) and Class Three (RR = 6.15, 95% CI = 5.39–7.03) were found to be significantly more likely to be between ages 15–17 than members of Class One. No gender differences were observed between Class One and Class Three. However, youth in Class Two were significantly less likely to be male compared to youth in Class One. Notably, compared to youth in Class One, those in Class Two and Class Three were significantly more likely to reside in households earning less than $50,000 per year and to live without their father in the home.

Table 3.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Bi/Multiracial Youth in Latent Classes

| Class 1: “High Protection, Low Risk” 50.43% [48.6–52.2]) |

Class 2: “High Protection, Elevated Risk” (21.66% [20.4–23.0]) |

Class 3: “Low Protection, Elevated Risk” (27.9% [26.4–29.5]) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (95% CI) | % | (95% CI) | RR | (95% CI) | % | (95% CI) | RR | (95% CI) | |

| Demographic | ||||||||||

| Factors | ||||||||||

| Age | ||||||||||

| 12–14 Years | 75.31 | 73.3–77.2 | 18.77 | (16.4–21.4) | 1.00 | (1.25–1.75) | 33.76 | (31.6–36.0) | 1.00 | (1.25–1.75) |

| 15–17 Years | 24.69 | (22.8–26.7) | 81.23 | (78.6–83.6) | 13.94 | (11.4–17.1) | 66.24 | (64.0–68.4) | 6.15 | (5.39–7.03) |

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Female | 48.40 | (46.1–50.7) | 62.47 | (59.0–65.8) | 1.00 | -- | 47.26 | (44.3–50.2) | 1.00 | -- |

| Male | 51.60 | (49.3–53.9) | 37.53 | (34.2–41.0) | 0.52 | (0.44–0.61) | 52.74 | (49.7–55.7) | 0.98 | (0.84–1.15) |

| Family Income | ||||||||||

| Less than $20,000 | 15.60 | (14.0–17.3) | 21.99 | (19.0–25.3) | 1.81 | (1.33–2.48) | 20.29 | (17.8–23.0) | 1.55 | (1.20–2.00) |

| $20,000-$49,999 | 32.14 | (29.9–34.4) | 35.34 | (31.8–39.0) | 1.40 | (1.08–1.81) | 36.44 | (33.3–39.6) | 1.39 | (1.09–1.77) |

| $50,000-$74,999 | 19.41 | (17.7–21.2) | 18.03 | (15.7–20.6) | 1.25 | (0.93–1.68) | 18.67 | (16.5–21.1) | 1.29 | (0.98–1.69) |

| $75,000 or greater | 32.85 | (30.4–35.4) | 24.64 | (21.9–27.6) | 1.00 | -- | 24.60 | (22.2–27.1) | 1.00 | -- |

| Father in Household | ||||||||||

| Yes | 71.59 | (69.3–73.8) | 63.17 | (60.1–66.1) | 1.00 | -- | 60.73 | (58.1–63.3) | 1.00 | -- |

| No | 28.41 | (26.2–30.7) | 36.83 | (33.9–39.9) | 1.17 | (1.06–1.30) | 39.27 | (36.7–41.9) | 1.25 | (1.15–1.34) |

Note. All percentages are survey adjusted column percentages. Reference class in multinomial regression analyses specified as Class 1 (i.e., “High Protection, Low Risk”). Relative risk ratios (RR) adjusted for age, gender family income, and father in household. RR in bold represent a significant difference at p < .05 and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) that do not overlap with 1.00.

Table 4 displays a clear pattern of differences between the latent classes with respect to the use of tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, and other illicit drugs. Indeed, we see not only a uniform pattern of significant differences, but also we see noteworthy effects with respect to the magnitude of the relative risk ratios. As a point of reference, Chen and colleagues (2010) suggest that odds ratios, which are comparable but not identical to risk ratios, can be classified as small (1.68), medium (3.47), or large (6.71 or greater). With Class One as the reference category, we see—even controlling for age, gender, family income, and father in the household—medium to large risk ratios for Class Two and large to very large risk ratios for Class Three, indicating a severity gradient of increased substance use risk.

Table 4.

Substance Use Characteristics of the Latent Class Models

| Class 1: “High Protection, Low Risk” 50.43% [48.6–52.2]) |

Class 2: “High Protection, Elevated Risk” (21.66% [20.4–23.0]) |

Class 3: “Low Protection, Elevated Risk” (27.9% [26.4–29.5]) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (95% CI) | % | (95% CI) | RR | (95% CI) | % | (95% CI) | RR | (95% CI) | |

| Past Month Use | ||||||||||

| Tobacco | ||||||||||

| No | 98.53 | (98.0–98.9) | 89.95 | (87.7–91.8) | 1.00 | 69.23 | (66.7–71.6) | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 1.47 | (1.08–1.99) | 10.05 | (8.16–12.32) | 4.62 | (2.97–7.19) | 30.77 | (28.4–33.2) | 21.47 | (15.6–29.43) |

| Alcohol | ||||||||||

| No | 96.88 | (96.0–97.5) | 85.98 | (83.9–87.8) | 1.00 | 68.41 | (65.5–71.2) | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 3.12 | (2.5–4.0) | 14.02 | (12.2–16.1) | 2.85 | (2.07–3.93) | 31.59 | (28.8–34.5) | 9.81 | (7.40–12.99) |

| Marijuana | ||||||||||

| No | 99.41 | (98.9–99.69) | 89.28 | (86.5–91.5) | 1.00 | 76.06 | (73.4–78.5) | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 0.59 | (0.31–1.10) | 10.72 | (8.5–13.47) | 12.90 | (6.26–26.56) | 23.94 | (21.5–26.6) | 38.19 | (20.48–71.2) |

| Other Illicit Drugs | ||||||||||

| No | 98.40 | (97.8–98.8) | 93.97 | (91.5–95.8) | 1.00 | 88.17 | (86.3–89.8) | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 1.60 | (1.19–2.15) | 6.03 | (4.2–8.5) | 3.28 | (1.77–6.08) | 11.83 | (10.2–13.69) | 7.75 | (4.99–12.04) |

| Past Year Use | ||||||||||

| Tobacco | ||||||||||

| No | 95.57 | (94.5–96.4) | 79.07 | (76.1–81.7) | 1.00 | 57.67 | (55.1–60.2) | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 4.43 | (3.57–5.47) | 20.93 | (18.3–23.9) | 3.57 | (2.59–4.92) | 42.33 | (39.8–44.9) | 11.39 | (8.83–14.71) |

| Alcohol | ||||||||||

| No | 90.22 | (88.8–91.5) | 61.27 | (57.5–64.9) | 1.00 | 43.95 | (41.4–46.5) | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 9.78 | (8.5–11.23) | 38.73 | (35.1–42.5) | 3.26 | (2.63–4.03) | 56.05 | (53.5–58.6) | 8.37 | (6.95–10.08) |

| Marijuana | ||||||||||

| No | 97.95 | (97.3–88.5) | 78.16 | (75.1–81.0) | 1.00 | 60.97 | (58.1–63.8) | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 2.05 | (1.5–2.74) | 21.84 | (19.0–24.9) | 7.57 | (5.36–10.70) | 39.03 | (36.2–41.9) | 20.86 | (15.3–28.4) |

| Other Illicit Drugs | ||||||||||

| No | 95.47 | (94.6–96.2) | 84.58 | (81.6–87.1) | 1.00 | 74.09 | (71.5–76.5) | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 4.53 | (3.8–5.36) | 15.42 | (12.8–18.4) | 3.27 | (2.38–4.49) | 25.91 | (23.4–28.5) | 6.77 | (5.30–8.63) |

Note. All percentages are survey adjusted column percentages. Reference class in multinomial regression analyses specified as Class 1 (i.e., “High Protection, Low Risk”). Relative risk ratios (RR) adjusted for age, gender, family income, and father in household. RR in bold represent a significant difference at p < .05 and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) that do not overlap with 1.00.

Discussion

Results from our study confirm that, with few exceptions, bi/multiracial youth in general report higher levels of tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, and other illicit drug use compared to other youth of color. Bi/multiracial youth also report higher levels of marijuana but lower levels of tobacco and alcohol use compared to non-Hispanic white youth. However, latent class modeling also reveals that a majority (54%) of bi/multiracial youth experience high levels of psychosocial protection (i.e., strong antidrug views, elevated parental engagement) and low levels of psychosocial risk (i.e., low peer substance use, school-related problems, and social-environmental risk), and report very low levels of substance use. This finding is consistent with prior research suggesting that most youth report little-to-no involvement in substance use and other problem behaviors as teenagers (Salas-Wright, Lombe, Vaughn, & Maynard, 2016; Salas-Wright, Nelson, Vaughn, Reingle Gonzalez, & Córdova, 2017; Vaughn, Salas-Wright, DeLisi, & Maynard, 2014).

Importantly, we also identified two additional subgroups of bi/multiracial youth based on salient psychosocial risk and protective factors. The first of these two classes was a group of adolescents (roughly 22%) characterized by elevated levels of psychosocial protection in concert with elevated psychosocial risk. The second group we identified (roughly 28%) was marked by low psychosocial protection and elevated risk. Not only were these two classes markedly distinct from the high protection/low risk class in terms of past month and past year substance use, but we also observed important differences between these two at-risk classes. Indeed, as compared with youth classified as high protection/elevated risk, the youth reporting low protection/elevated risk had 2 to 5 times the prevalence of tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, and other illicit drug use. Again, this finding underscores that bi/multiracial youth are a heterogeneous group, and this heterogeneity has important implications for substance use risk.

Findings from the present study may have a number of important implications for prevention and intervention efforts designed to target bi/multiracial youth. First, study findings clearly suggest that, although bi/multiracial youth in general seem to experience greater risk for substance use, bi/multiracial youth are anything but a monolithic group. This fact is critical to keep in mind as prevention scientists take steps to advance the development of prevention programs designed for this rapidly-growing population. Second, our findings provide compelling evidence that beyond targeting only risk or only protective factors, prevention and intervention programs would do well to enhance and support psychosocial protections just as they aim to ameliorate sources of psychosocial risk (Salas-Wright, Vaughn, & Reingle Gonzalez, 2017). This implication is consistent with the insights from holistic youth development programs, such as the Strong African American Families Program (Brody et al., 2004) and Communities That Care (Hawkins, Catalano, & Kuklinski, 2014), that are designed to simultaneously account for risk and protective processes in the lives of young people. Third, our findings also suggest that in the face of exposure to psychosocial risk factors such as peer substance use and easy drug access, the buffering effect of psychosocial protections should not be underestimated. Often times it is not feasible to quickly eliminate sources of social risk; nevertheless, findings from the present study suggest that focusing on supporting or enhancing psychosocial protections is worthwhile (Catalano, Hawkins, Berglund, Pollard, & Arthur, 2002; Rutter, 1987; Vera & Shin, 2006).

Study Limitations

Findings should be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, the NSDUH public use data file provides imperfect measurement of bi/multiracial identity. Specifically, while non-Hispanic youth who select more than one race on the survey were grouped into a singular category, the NSDUH does not allow researchers to distinguish between biracial (i.e., two racial backgrounds) and multiracial (i.e., three or more racial backgrounds) categories. Moreover, researchers are not able to identify which racial backgrounds a particular youth selected. Second, although we pooled data collected between 2002 and 2014 to increase the size of our analytic sample and to ensure the stability of prevalence estimates, the NSDUH data are fundamentally cross-sectional. Therefore, we cannot make causal interpretations based on these data. Last, the NSDUH does not include genetic or other biological data that we know to be critical in understanding adolescent risk behavior (Vaughn, Salas-Wright, & Reingle-Gonzalez, 2016). Future studies should seek to remedy these shortcomings by using multiple data collection methods, the use of prospective designs, and the integration of biological measures relevant to substance use and behavioral risk.

Conclusions

Results from our study confirm that bi/multiracial youth in general report, with few exceptions, higher levels of tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, and other illicit drug use compared to other youth of color. Bi/multiracial youth also report higher levels of marijuana use than non-Hispanic white youth. We identified, using person-centered analytic methods, three distinct subgroups of bi/multiracial adolescents that differ significantly across a range of established risk and protective factors for substance use. Notably, more than half (54%) of bi/multiracial youth in the sample were classified as experiencing high levels of psychosocial protection and low levels of psychosocial risk, and reported very low levels of substance use.

That being said, a significant proportion of bi/multiracial youth did, in fact, face elevated levels of substance use risk. More precisely, two subgroups of youth—which, notably, tended to be older and to reside in low income households—reported greater levels of psychosocial risk and varying levels of protection, and reported substantially higher levels of substance use. Substance use was particularly elevated among the subset of youth reporting elevated psychosocial risk (i.e., peer substance use, school-relate problems, social environmental risk) and low levels of protection (i.e., permissive antidrug views, low levels of parental engagement). While universal prevention programs offer many benefits, future efforts to address substance use among bi/multiracial youth would do well to also develop prevention programs designed to address the psychosocial needs of those youth most at risk.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest: This research was supported in part by the National Institute on Drug Abuse at the National Institutes of Health (K01 DA035895 and P30 DA027827). The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest associated with this manuscript.

References

- Brody GH, Murry VM, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Molgaard V, McNair L, ... Chen YF (2004). The Strong African American Families program: Translating research into prevention programming. Child Development, 75(3), 900–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Hawkins JD, Berglund ML, Pollard JA, & Arthur MW (2002). Prevention science and positive youth development: competitive or cooperative frameworks?. Journal of Adolescent Health, 31(6), 230–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Cohen P, & Chen S (2010). How big is a big odds ratio? Interpreting the magnitudes of odds ratios in epidemiological studies. Communications in Statistics—Simulation and Computation, 39(4), 860–864. [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y, He M, Herrenkohl TI, Catalano RF, & Toumbourou JW (2012). Multiple identification and risks: Examination of peer factors across multiracial and single-race youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41(7), 847–862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y, Harachi TW, Gillmore MR, & Catalano RF (2006). Are multiracial adolescents at greater risk? Comparisons of rates, patterns, and correlates of substance use and violence between monoracial and multiracial adolescents. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 76(1), 86–97. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.76.1.86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark TT, Corneille M, & Coman E (2013). Developmental trajectories of alcohol use among monoracial and biracial Black adolescents and adults. Journal of psychoactive drugs, 45(3), 249–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark TT, Nguyen AB, & Kropko J (2013). Epidemiology of drug use among biracial/ethnic youth and young adults: results from a US population-based survey. Journal of psychoactive drugs, 45(2), 99–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark TT, Salas-Wright CP, Vaughn MG, & Whitfield KE (2015). Everyday discrimination and mood and substance use disorders: A latent profile analysis with African Americans and Caribbean Blacks. Addictive Behaviors, 40, 119–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funderburg L (1994). Black, white, other. New York: Morrow. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, & Kuklinski MR (2014). Communities that care In Bruinsma G & Weisburd D (Eds.), Encyclopedia of criminology and criminal justice (pp. 393–408). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Humes K,R, Jones NA, & Ramirez RR (2011). Overview of race and Hispanic origin: 2010. 2010 Census Briefs Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-02.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KF, & LeCroy C (2009).The influence of race on substance use and negative activity involvement among monoracial and multiracial adolescents of the Southwest. Journal of Drug Education, 39, 195–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones NA, & Bullock JJ (2012). The two or more races population: 2010 (Pub. No. C2010BR-13). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; Retrieved http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-13.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, & Bean FD (2004). America’s changing color lines: Race/ethnicity, immigration, and multiracial identification. Annual Review of Sociology, 30, 221–242. [Google Scholar]

- Maynard BR, Salas-Wright CP, Vaughn MG, & Peters KE (2012). Who are truant youth? Examining distinctive profiles of truant youth using latent profile analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41, 1671–1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan G, & Peel D (2004). Finite mixture models. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. (2015). Multiracial in America: Proud, diverse, and growing numbers. Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2015/06/11/multiracial-in-america/

- Rutter M (1987). Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 57(3), 316–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1987.tb03541.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas-Wright CP, Lombe M, Vaughn MG, & Maynard BR (2016). Do adolescents who regularly attend religious services stay out of trouble? Results from a national sample. Youth & Society, 48(6), 856–881. [Google Scholar]

- Salas-Wright CP, Nelson E, Vaughn MG, Reingle Gonzalez JM & Córdova D (2017).Trends in fighting and violence among adolescents in the United States, 2002–2014. American Journal of Public Health, 107(6), 977–982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas-Wright CP, Vaughn MG, & Reingle Gonzalez JM (2017). Drug abuse and antisocial behavior: A biosocial life-course approach. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Salas-Wright CP, Vaughn MG, Todic J, Córdova D, & Perron BE (2015). Trends in the disapproval and use of marijuana among adolescents and young adults in the United States: 2002–2013. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 41, 392–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J, & Edmonston B (Eds). (1997). The new Americans: Economic, demographic, and fiscal effects of immigration. Washington, DC: National Research Council, National Academy Press. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. (2015). Stata statistical software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2014). National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2014.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2016). Retrieved January 1, 2017 from: https://nsduhweb.rti.org/respweb/confidentiality.html

- Udry JR, Li RM, & Hendrickson-Smith J (2003). Health and behavior risks of adolescents with mixed-race identity. American Journal of Public Health, 93, 1865–1870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U. S. Census Bureau. (2008). An older more diverse national by midcentury. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb08-123.html

- Vaughn MG, Salas-Wright CP, DeLisi M, & Maynard BR (2014). Violence and externalizing behavior among youth in the United States: Is there a severe 5%? Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 12(1), 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn MG, Salas-Wright CP, & Reingle-Gonzalez JM (2016). Addiction and crime: The importance of asymmetry in offending and the life-course. Journal of Addictive Diseases. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2016.1189658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vera EM, & Shin RQ (2006). Promoting strengths in a socially toxic world: Supporting resiliency with systemic interventions. The Counseling Psychologist, 34(1), 80–89. [Google Scholar]

- Vermunt JK, & Magidson J (2013). Latent GOLD 5.0 upgrade manual. Belmont, MA: Statistical Innovations. [Google Scholar]

- Ziol-Guest KM, & McKenna C (2009). Early childhood residential instability and school readiness: Evidence from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study. Center for Research on Child Wellbeing Working Paper 2009–21-FF. [Google Scholar]