Abstract

Treatment of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacterial pathogens represents a critical clinical need. Here, we report a novel γ-lactam pyrazolidinone that targets penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs) and incorporates a siderophore moiety to facilitate uptake into the periplasm. The MIC values of γ-lactam YU253434, 1, are reported along with the finding that 1 is resistant to hydrolysis by all four classes of β-lactamases. The druglike characteristics and mouse PK data are described along with the X-ray crystal structure of 1 binding to its target PBP3.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

At the present time, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is creating significant economic hardships, impacting public health, and is leading to untreatable infections that are associated with significant morbidity and mortality. In the United States alone, more than two million infections each year are caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria, resulting in approximately 35,000 deaths and more than $20 billion in healthcare cost.1 The global impact is staggering with an estimated cumulative economic cost of $100 trillion by 2050 and 10 million deaths resulting from multidrug-resistant (MDR) infections.2 In particular, MDR Gram-negative bacterial pathogens are associated with mortality rates up to 30–70% and are classified by the WHO as priority 1 pathogens.3–7

The “hard-to-treat” nature of these infections is often due to extensive antibiotic-resistant phenotypes that allow pathogens to overcome many standard-of-care antibiotic therapies.8 Despite the increasing public health threat, few truly novel agents are in development to treat such infections as large pharmaceutical companies have withdrawn from antibacterial research.3,4,9,10 Government agencies are aware of the ever-growing issue of AMR and are responding with several initiatives in an effort to incentivize renewed efforts in antibiotic development.11 These initiatives include public–private partnerships highlighting the urgency and need for novel treatment solutions.

Resistance in MDR Gram-negative organisms is multicausal due not only to reduced permeability observed with all Gram-negative pathogens but also to efficient and diverse efflux pumps.12,13 Of particular concern are WHO priority 1 pathogens, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacterales5 that possess plasmid-mediated carbapenemases (β-lactamases (blas): NDM-1, KPC, and OXA-type class D carbapenemases), making them nearly untreatable with β-lactam antibiotics.1 Nevertheless, β-lactam antibiotics remain a mainstay treatment for infections and are often used in combination with β-lactamase inhibitors. Clearly, new antibacterial agents are needed to effectively treat infections caused by MDR pathogens.

The search for new antibiotic targets is crucial but not a prerequisite for success. In this report, we exploit a well-known target, the penicillin binding proteins (PBPs), using a new non-β-lactam pyrazolidinone chemical scaffold. These pyrazolidinones, coupled with a siderophore for penetration, irreversibly inhibit PBPs by acylating the catalytic serine. Importantly pyrazolidinones are poorly hydrolyzed by all four classes of β-lactamases, thus avoiding the Achilles’ heel of β-lactam antibiotics, including those used as last resort treatments. Herein, we report the attributes of one such pyrazolidinone, YU253434, 1.

More than 30 years ago, pyrazolidinones that demonstrated potent Gram-positive bacterial activity, low oral bioavailability, and suboptimal Gram-negative activity were discovered.14–17 These agents did not progress to the clinic as the focus of antibacterial research at that time was on developing broad-spectrum oral agents17 with potent Gram-positive activity. Early compounds displayed some Gram-negative activity when aminothiazoleoxime-type side chains were employed, especially when combined with very strongly electron-withdrawing C(3) substituents like a cyano group (Figure 1).16,17 The effect of C(3) substituents on activity and stability has been established.16,17 Broadly, MIC correlates with the electron withdrawing nature of the σp value of the C(3) substituent and is tunable for reactivity and stability.14,18 Here, we use only a mildly electron-withdrawing amide group at C(3), which imparts low reactivity and remarkable stability, while simultaneously using the amide to append a siderophore moiety (Figure 1).

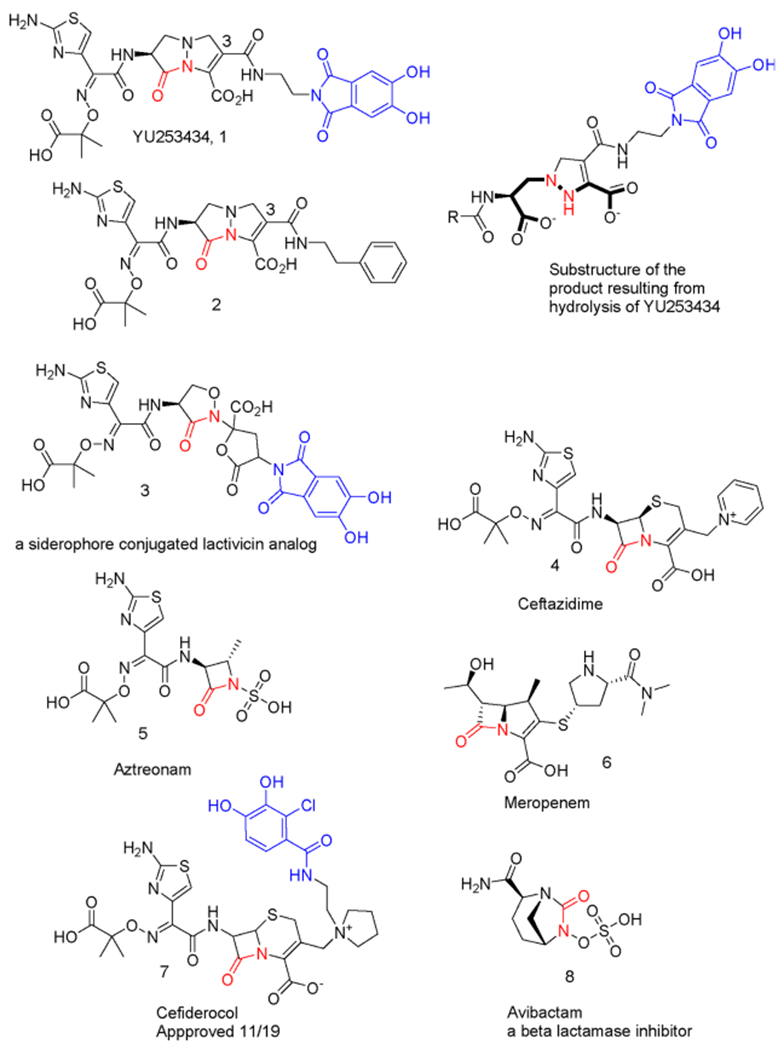

Figure 1.

Comparator agents and select siderophore containing PBP inhibitors as well as the β-lactamase inhibitor avibactam. Highlighted in red is the site that covalently modifies the PBP or β-lactamase catalytic serine. When a siderophore mimic is present, it is highlighted in blue.

To improve cell uptake, we strategically exploit the notion that bacteria have highly developed methods for acquiring iron, which is crucial to their survival in their native environment as well as in hosts.19 Generally, the siderophore is synthesized and released by the bacterium to acquire iron and effectively compete with other siderophores, from other bacterial species or with endogenous iron binding proteins of the host. Once the siderophore has complexed with iron, it is actively imported through a variety of specialized receptors.20,21 Often, the small-molecule natural siderophores are structurally complex and species-selective. To utilize the import receptors, the siderophores fortunately can be much simpler siderophore mimics. Previously, such mimics were used to import antibacterial agents into the Gram-negative periplasmic space where PBP targets reside, colloquially known as a Trojan Horse strategy. Only one such agent, cefiderocol (Figure 1), has received recent approval.22

The design, synthesis, and in vitro characterization of 1, a novel pyrazolidinone antibiotic containing a dihydroxyphthalimide siderophore mimetic, is reported herein.23 Antimicrobial activity is described in comparison to current β-lactam antibiotics against select clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa, K. pneumoniae, and Escherichia coli as well as the compound’s PBP binding characteristics and 2.4 Å resolution crystal structure in complex with P. aeruginosa PBP3. The chemical structures of 1 and comparator agents are shown in Figure 1.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Syntheses.

The synthesis of 1 (Scheme 1) follows, in part, the previous synthesis of pyrazolidinones and begins with conversion of Boc-l-serine to the known cyclic hydrazide 9.14,17 The reaction of this hydrazide with the known acryl phosphonate results in the addition of the nucleophilic amine to cleanly give the substituted phosphonohydrazide 10. The phosphonohydrazide, 10, could be used in the crude form but was often purified by silica gel chromatography. The reaction of 10 with tert-butyl-2-chloro-2-oxoacetate in dichloromethane with excess Hunig’s base resulted in acylation followed by slow ring closure to the pyrazolidinone nucleus 11. Selective deprotection of the allyl ester provides the intermediate acid, 12, in six steps with one chromatographic purification. Intermediate 12 is suitably differentiated to allow incorporation of a diverse set of amide-linked siderophores and PBP recognition elements (see below). To this end, the acid 12 was converted to its acid chloride with oxalyl chloride and reacted in situ with the known siderophore23 13, which was best solubilized and transiently protected using N-methyl-N-(trimethylsilyl) trifluoroacetamide (MSTFA) to give 14. Deprotection of 14 with trifluoroacetic acid in dichloromethane using triethylsilane as a scavenger gave the amino acid intermediate 15. The acid chloride of the suitably protected aminothiazole 16 was formed using oxalyl chloride and reacted with the amine 15 that had been protected and solubilized using MSTFA to give the acylated product 17. Crude 17 was deprotected with trifluoroacetic acid in dichloromethane using triethylsilane as a scavenger to give 1. The chiral purity of 1 was not assessed after the synthesis was completed although Boc-l-serine was employed as the starting material.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of YU253434, 1a.

a(a) Allyl 2-(diethoxyphosphoryl)acrylate, DCM, RT, 1 h, 98%; (b) tert-butyl 2-chloro-2-oxoacetate, DCM, 0 °C to RT, Hunig’s base, 18 h, 100% crude; (c) acetonitrile, triethylsilane, Pd(PPh3)4, 0 °C to RT, 65%; (d) (i) oxalyl chloride, 12, (ii) MSTFA, Hunig’s base, 13, 38%; (e) 2:1 DCM/TFA, triethylsilane, 0 °C to RT, 3.5 h, 100% crude; (f) (i) oxalyl chloride, catalytic DMF, 16, (ii) MSTFA, Hunig’s base, 15, 3.5 h, 100% crude; (g) 2:1 DCM/TFA, triethylsilane, 0 °C to RT, 1.5 h, toluene chase, reverse-phase MPLC C18, 0 to 60% acetonitrile 0.1% formic acid/water with 0.1% formic acid, 38%.

Antimicrobial Activity.

Pyrazolidione 1 was tested against large panels of P. aeruginosa (197 previously described clinical isolates),24 K. pneumoniae (100 previously described clinical isolates),25 and E. coli (100 previously described clinical isolates).26,27 A summary of the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) are presented in Figure 2 and Table 1.

Figure 2.

Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of 1 against P. aeruginosa (197 clinical isolates), K. pneumoniae (100 clinical isolates), and E. coli (100 clinical isolates).

Table 1.

MIC50 and MIC90 Values (μg/mL) for 1 and Comparator Antibiotics for P. aeruginosa (197 Clinical Isolates), K. pneumoniae (100 Clinical Isolates), and E. coli (100 Clinical Isolates)a

|

P. aeruginosa |

K. pneumoniae |

E. colib |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compound | MIC50 | MIC90 | MIC50 | MIC90 | MIC50 | MIC90 |

| 1 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| aztreonam (5) | 8 | >16 | >32 | >32 | ≤2 | >16 |

| ceftazidime (4) | 4 | >16 | >64 | >64 | 2 | >16 |

| meropenem (6) | 2 | >8 | 16 | >64 | ≤1 | 8 |

| ceftolozane/tazobactam | 1 | >32 | 64 | >64 | NA | NA |

| ceftazidime/avibactam (8) | 4 | >32 | 0.5 | 2 | NA | NA |

All strains used are from previously described collections. The reported comparator antibiotic MICs are from the original studies.

Data for comparator antibiotics only available for 90 (aztreonam), 98 (ceftazidime), or 99 (meropenem) of the 100 samples in the test panel; NA: no data available.

The MICs compare favorably to representative β-lactam agents currently used in the clinic to treat MDR Gram-negative infections including aztreonam (5, monobactam), ceftazidime (4, antipseudomonal cephalosporin), and meropenem (6, carbapenem). Additional MICs for 15 of the P. aeruginosa isolates can be found in Table S10.1. MICs were also determined for additional clinical K. pneumoniae (16 isolates) and E.coli (14 isolates) and can be found in Tables S10.2 and S10.3.

The effects of iron concentration on the MICs of 1 were also evaluated against representative strains of P. aeruginosa (laboratory strain PAO1 and a clinical isolate). Previously, the concentration of free iron in the culture medium was shown to inversely correlate with antimicrobial activity of siderophore-containing β-lactam antibiotics including BAL3007228 and cefiderocol.29 As shown in Table 2, the addition of soluble iron to the culture medium caused a similar concentration-dependent decrease in 1’s activity in both strains. This effect was observed for cefiderocol 7, which also contains a catechol moiety that has been shown to drive its cellular uptake and antimicrobial activity.29 As a control, ceftazidime 4, which does not have an iron-chelating ability, showed MICs independent of media iron concentration. These results are consistent with the Trojan Horse mechanism of siderophore antibiotics, and for this reason, iron-depleted media were used for all MIC determinations. The low-iron media follow CLSI protocols for testing siderophore-containing antibacterial agents as the modified broth is thought to replicate the low-iron environment found in vivo. To further confirm that 1 is transported via a siderophore uptake mechanism, the isosteric phenethyl amide analog 2, expected to have no siderophore transport qualities, was synthesized in a manner parallel to 1. Testing in an abbreviated MIC panel of Gram-negative isolates showed that the MIC values of 2 were all >64 μg/mL, the upper concentration tested, while 1 displayed significant activity (data not shown).

Table 2.

Effect of Iron Concentration on MIC Values for 1 and Comparator Antibiotics versus P. aeruginosa PAO1 and the Clinical Isolate

| MIC (μg/mL)a |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAO1 |

clinical isolate |

|||||

| added iron (μg/mL) | 1 | ceftazidime 4 | cefiderocol 7 | 1 | ceftazidime 4 | cefiderocol 7 |

| 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.06 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.13 |

| 0.1 | 2 | 1 | 0.25 | 4 | 1 | 0.13 |

| 1.0 | 16 | 1 | 0.5 | >16 | 1 | 0.25 |

| 10 | >16 | 1 | 2 | >16 | 1 | 1 |

MICs were determined using iron-depleted cation-adjusted Mueller–Hinton broth that was supplemented with iron (as ferric chloride) as indicated. The initial iron-depleted media were prepared by the standard treatment with cation-exchange resin, which has been reported to reduce iron concentrations to 0.02 μg/mL.29 Therefore, the total media iron concentrations as tested are expected to be 0.02, 0.12, 1.02, and 10.02 μg/mL.

β-Lactamase Stability.

Appending the phthalimide siderophore mimic from the C(3) amide of the pyrazolidinone was deliberate and designed to occupy space allowed by the enzyme target PBP3. Prospectively, when 1 was modeled in class A serine β-lactamases in a transition state presumed for hydrolysis, we observed the pyrazolidine ring with its additional methylene group projects the aminothiazole side chain in a different direction when compared to the aminothiazole group in β-lactams like ceftazidime. The consequence is that the γ-lactam in 1 positions the aminothiazole in a manner where it is predicted to sterically clash with the omega loop of the class A β-lactamases. (Figure S1) This could be one of the reasons why 1 is not hydrolyzed by class A β-lactamases and also perhaps the related class C and class D serine β-lactamases. In fact, testing against isolates that express class A, C, and D β-lactamases, 1 shows significant resistance to hydrolysis (enzyme stability). This important observation is further supported by testing against representative β-lactamases: KPC-2 (class A carbapenemase), OXA-23 and OXA-24 (class D carbapenemases); PER-2 (class A extended-spectrum β-lactamase); and PDC-3 (P. aeruginosa class C β-lactamase). In all cases, hydrolysis was not detected. The observed β-lactamase stability correlates with the MIC data (Table 1 and Figure 2) as most tested isolates had their β-lactamase genes identified by whole-genome sequencing or rapid molecular diagnostics, and there was no correlation of the presence of any class of enzymes with the susceptibility of the organism (see Supplemental Information, Tables S9.1–S9.3). The clinical implications from this analysis suggest a clinical niche for this agent.

For the class B β-lactamases (metallo-enzymes), resistance to hydrolysis was not anticipated. Interestingly, 1 is a poor substrate for NDM-1, VIM-2, and IMP-1 as compared with imipenem (Table 3). This central observation is supported by the MIC results where 1 has low MIC values against isolates expressing class B β-lactamases. Although we did not anticipate the poor hydrolysis of 1 in advance, we do recognize that the product of the hydrolysis (Figure 1) has a unique hydrazide and carboxylate functionality (bold bonds), which are suitable for zinc chelation and as such could form inhibitory interactions in class B β-lactamase active sites.

Table 3.

Susceptibility of 1 to β-Lactamase Hydrolysisa

| 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| metallo-β-lactamase | kcat (s−1) | Km (μM) | kcat/Km (μM−1 s−1) |

| NDM-1 | 7 ± 1 | 292 ± 25 | 0.020 ± 0.002 |

| VIM-2 | 20 ± 2 | 840 ± 180 | 0.020 ± 0.002 |

| IMP-1 | 5 ± 1 | 76 ± 8 | 0.070 ± 0.010 |

| Imipenem | |||

| metallo-β-lactamase | kcat (s−1) | Km (μM) | kcat/Km (μM−1 s−1) |

| NDM-1 | 173 ± 18 | 65 ± 7 | 2.7 ± 0.3 |

| VIM-2 | 57 ± 6 | 8.5 ± 0.9 | 6.7 ± 0.7 |

| IMP-1 | 36 ± 4 | 11 ± 1 | 3.2 ± 0.4 |

Steady-state reactions of 1 were monitored against purified enzymes: KPC-2, OXA-23, OXA-24, PER-2, PDC-3, NDM-1, VIM-2, and IMP-1. Kinetic parameters are provided below. Imipenem was used as a control. No reaction was detected for KPC-2, OXA-23, OXA-24, or PER-2 using a 200 nM enzyme concentration and 100 μM 1.

Druglike Attributes.

Pyrazolidinone 1 has many characteristics that are favorable for potential administration either by IV or inhalation routes as 1 has a solubility of >100 μM in pH 7.5 phosphate buffer as measured by nephelometry. In this same buffer, 1 has remarkable stability with only ~4% hydrolysis to the ring-opened product after 2 weeks at room temperature. Meropenem in comparison is known to be unstable after reconstitution in IV bags, often showing >30% degradation in 24 h after reconstitution. The stability of 1 is a reflection of the mild electron-withdrawing nature of the C(3) amide group, as mentioned earlier.18 Although highly soluble, 1 has poor Caco-2 permeability and would not be expected to have oral bioavailability. Stability to both human and CD-1 mouse microsomes is notable with a half-life of >60 min in both preparations. Furthermore, 1 does not inhibit any of the eight CYP enzymes it was tested against at a 30 μM concentration. The pharmacokinetics (PK) of 1 were evaluated both subcutaneously and by intravenous administration at a dose of 50 mg/kg in CD-1 mice (Table 4). Both routes of dosing result in nearly identical PK data.

Table 4.

Plasma PK Parameters after IV Administration of 1 at 50 mg/kg in Mice

| animal | t1/2 (h) | C0 (ng/mL) | AUClast (h ng/mL) | AUCINF (h ng/mL) | AUC extr (%) | MRT (h) | Vss (L/kg) | CL (mL/min/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IV Mouse | 11 | 200,844 | 55,866 | 57,791 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 14 |

The clearance is rapid but is similar to intravenous β-lactam antibiotics and may be driven by excretion through urine, which was not measured. Blood levels of 1 are maintained above 1 μg/mL at the 2 h time point (Figure 3). Notably, 1 μg/mL is the MIC50 of 1 against the P. aeruginosa, K. pneumoniae, and E. coli strains tested. Toxicity was also not found when 1 was tested against primary human hepatocytes at the maximum concentration of 100 μM after 72 h of incubation. We further tested 1 against 44 enzyme receptors and channels that might be of a safety concern at a maximum dose of 30 μM and found only 63 and 66% inhibition of COX-1 and PDE3A, respectively, in this panel. Further examination of ion channels shows that 1 does not bind to hERG at 30 μM concentrations nor to seven other tested ion channels. Collectively, these data demonstrate promising characteristics of 1 and the pyrazolidinone scaffold as new antibacterial agents (Supplementary Information).

Figure 3.

Mean plasma concentration–time profile of 1 after IV (50 mg/kg) administration in mice.

PBP Binding.

Previous investigations proposed that pyrazolidinones targeted the crucial PBP3 enzyme. To verify that 1 could effectively target relevant PBPs consistent with its antimicrobial activity, kinetic studies were performed using a homogeneous preparation of P. aeruginosa PBP3, an essential transpeptidase following a previously established protocol using bocillin, a fluorescent penicillin analog.30 As shown in Figure 4, increasing concentrations of 1 inhibited bocillin’s ability to fluorescently label the protein, with an IC50 of 2.5 μM (Figure 3). This value is comparable to a previously published value for doripenem (IC50 = 2.3 ± 0.5 μM, Acinetobacter baumanni PBP3).30

Figure 4.

Determination of the IC50 for P. aeruginosa PBP3 using a competitive assay. Bocillin, a fluorescent substrate of PBP3, was reacted with an enzyme that had been pre-incubated with increasing concentrations of 1. The IC50 was calculated as the concentration of 1 required to reduce the fluorescence intensity of the bocillin-labeled protein by 50%.

DSF Thermal Shift Analysis of Ligand Binding to PBP3.

To further support the fact that 1 binds PBP3, we next examined the stabilizing effect of 1 binding to P. aeruginosa PBP3 using the DSF thermal shift assay. Pyrazolidinone 1 binding increased the melting temperature of P. aeruginosa PBP3 (with 1% DMSO) from 44.1 ± 0.14 to 51.0 ± 1.13 °C (Figure 5), an ~7 °C increase. Ceftazidime (4) yielded a larger stabilizing effect; the melting temperature of its P. aeruginosa PBP3 complex was 56.5 ± 0.14 °C (Figure 5). Despite the differences in increases in melting temperature between the two ligands, we could not discern whether there was a correlation of the magnitude of melting temperature increases with the affinity of ligands for proteins due to other effects such as entropy loss upon binding.

Figure 5.

DSF assay of 1 and ceftazidime binding to P. aeruginosa PBP3. The derivative of the change in fluorescence is plotted versus temperature.

PBP3 Crystal Structure Complexed with 1.

To probe the mechanism of PBP3 inhibition by the pyrazolidinone γ-lactam, including how an additional carbon atom in the lactam ring can be accommodated, we determined the 2.4 Å resolution crystal structure of 1 bound to P. aeruginosa PBP3. The PDB ID code is 6VOT.

The crystallographic refinement of the P. aeruginosa PBP3 structure revealed strong difference density for the 1 ligand, indicating that the catalytic S294 was acylated by the ligand (Figure 6, 6VOT). A clear electron density is present for most of 1 including the aminothiazole moiety, the amide moiety adjacent to the carbonyl bond, and the dihydropyrazole-carboxyl moiety (Figure 6). A weaker density is present for the other moieties, in particular the dihydroxyphthalimide siderophore mimic. This latter group’s main function is to promote uptake via the iron uptake/catechol pathway. The density for the 2-methylpropanoic acid of 1 is also not particularly strong (Figure 6). The active site protein residues are generally well ordered around the ligand 1 (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Electron density of 1 in the active site of P. aeruginosa PBP3. (A) Unbiased electron difference density (|Fo|–|Fc|) showing the density for a covalently bound 1 in the active site. Density is contoured at the 3σ level. Prior to map calculation, 10 cycles of Refmac refinement were carried out with 1 removed from the structure. The S349 side chain was observed in two conformations (labeled 1 and 2, refined with occupancies of 0.6 and 0.4, respectively). 1 is shown with cyan-colored carbon atoms. (B) Same as in (A) but the view is rotated ~100° around the x axis. (C) Stereodiagram of the 2|Fo|–|Fc| density map of the active site region; density is contoured at the 1σ level. PDB ID 6VOT.

The pyrazolidinone 1, when covalently bound in the active site of PBP3, makes several important interactions (Figure 7). A covalent bond is formed between the carbonyl carbon of 1 and the side chain of the catalytic S294. Several hydrogen bonds are made and include hydrogen bonds of the aminothiazole with residues E291 and backbone nitrogen and oxygen atoms of R489. The aminothiazole ring also makes hydrophobic interactions with A488, Y409, and G293. The amide moiety forms hydrogen bonds across the width of the active site with N351 and the backbone oxygen of T487. The carbonyl oxygen is situated in the oxyanion hole making hydrogen bonds with the backbone nitrogen atoms of S294 and T487. The carboxyl moiety attached to the dihydropyrazole ring makes hydrogen bonds with S485, T487, and S349 (conformation 2 of the S349 side chain; see Figure 6A): this pocket is the conserved carboxyl binding pocket. The amide moiety attached to the dihydropyrazole ring is less well defined, but the structure does suggest a water-mediated hydrogen bond with water W#1 (Figure 7). The dihydroxyphthalimide siderophore mimic does not make any direct hydrogen bonding interactions and points to the solvent in this structure.

Figure 7.

Interactions of 1 in the active site of P. aeruginosa. PBP3. Hydrogen bonds are depicted as black dashed lines. Water molecules are shown as round red spheres. Key active site residues are labeled.

Structural comparison of the 1 and ceftazidime complexes of P. aeruginosa PBP3.

The entire left-hand side of 1 is chemically similar to ceftazidime (4, Figure 1). Previously, the structure of ceftazidime bound to P. aeruginosa PBP3 was determined.32 We, therefore, compared 1 and ceftazidime (4) covalently bound to PBP3 structures via superposition (Figure 8). This analysis showed that the aminothiazole moieties in both bound 1 and ceftazidime are in a similar although slightly shifted position (shifted by ~0.5 Å), making almost identical interactions in the PBP3 active site (Figure 8). The minor shift of the aminothiazole away from the center of the active site is also apparent for the adjacent amide moiety in 1. These shifts in those moieties of 1 are likely due to accommodation of the extra methylene group in 1 since it contains a γ-lactam, not a β-lactam found in ceftazidime (4) or other approved PBP-targeting antibiotics. The superposition showed that the carboxyl moiety attached to the dihydropyrazole ring is in a similar position to the equivalent carboxyl group in ceftazidime; the oxygens are making hydrogen bonds with both S485 and T487 in both structures (Figure 8). Despite making similar hydrogen bonds, one of the oxygens of this carboxyl group in 1 is slightly shifted, allowing it to also make a hydrogen bond with the side chain of S349 in conformation 2 (Figure 8). The five-membered and six-membered rings attached to the carboxyl moieties in 1 and ceftazidime, respectively, are in similar positions although of different sizes. The prime side of the ligands is chemically very different. Compound 1 has a 5,6-dihydroxyphthalimide siderophore mimic connected via an amide-containing linker, whereas ceftazidime contains a pyridine ring at that position (Figure 1). This pyridine ring was not included in the model of the ceftazidime–PBP3 complex (PDB ID 3PBO),32 perhaps resulting from a lack of density due to conformational heterogeneity or due to possible pyridine elimination, which can occur for ceftazidime.38

Figure 8.

Comparison of the 1 and ceftazidime (4)-bound structures of P. aeruginosa PBP3. (A) Superposition of the PBP3–1 complex (gray protein carbon atoms) onto the PBP3–ceftazidime structure (gold-colored carbon atoms). The ligands are depicted in a ball-and-stick model, and 1 is shown with cyan carbon atoms. (B) Same as in (A) but a close-up view of the active site region near the covalent bond with S294 to highlight differences in the β-lactam (ceftazidime, 4)- and γ-lactam (1)-based ligands. Hydrogen bonds of 1 and ceftazidime with their corresponding PBP3 coordinates are shown as black and gray dashed lines, respectively.

An additional difference between the 1- and ceftazidime-bound PBP3 structures is that the 2-methylpropanoic acid of 1 does not make a salt bridge interaction with the side chain of R489. The R489 side chain is more distant compared to that in the ceftazidime-bound structure (Figure 8). This could be because this region of the protein and the ligand are in general more flexible or perhaps due to an ~0.5 Å shift relative to ceftazidime in that section of the 1 compound. Data collection and refinement statistics for the structure of P. aeruginosa PBP3 complexed with 1 can be found in Table 5.

Table 5.

Data Collection and Refinement Statistics for Crystal Structure of P. aeruginosa PBP3 Complexed to 1a

| wavelength (Å) | 0.97946 |

| resolution range (Å) | 50.00–2.40 (2.44–2.40) |

| space group | P21 21 21 |

| unit cell (Å; °) | 68.107, 83.813, 89.74; 90, 90, 90 |

| total reflections | 167,804 |

| unique reflections | 20,549 (987) |

| multiplicity | 8.2 (6.8) |

| completeness (%) | 99.7 (100) |

| mean I/sigma (I) | 16.1 (4.1) |

| Wilson B factor | 31.60 |

| R merge (%) | 13.6 (58.8) |

| reflections used in refinement | 20,503 (1922) |

| reflections used for Rfree | 1057 (80) |

| R-work | 0.182 (0.239) |

| Rfree | 0.236 (0.290) |

| number of non-hydrogen atoms | 3951 |

| macromolecules | 3866 |

| solvent | 85 |

| protein residues | 500 |

| RMS (bonds, Å) | 0.014 |

| RMS (angles, °) | 1.85 |

| Ramachandran favored (%) | 97.78 |

| Ramachandran allowed (%) | 2.22 |

| Ramachandran outliers (%) | 0.00 |

Statistics for the highest-resolution shell are shown in parentheses.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, we described a novel non-β-lactam penicillin binding protein (PBP) inhibitor, Compound 1, that contains a γ-lactam moiety whose carbonyl group covalently modifies the catalytic serine of the target PBPs (PBP3). The pyrazolidinone 1 has excellent chemical stability and remarkable activity against WHO priority 1 pathogens such as P. aeruginosa and Enterobacterales. Furthermore, 1 has been found to be stable in all four classes of β-lactamases. X-ray crystallography helps to define where further optimization can occur and illustrate unique interactions with P. aeruginosa PBP3. Additionally, 1 was found to have druglike characteristics. Further testing of 1 and the design and synthesis of additional analogs are planned.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations (MICs).

Bacterial strains used were from previously described collections. MICs were determined using the general recommendations of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Standard broth microdilution methods were followed but with a slightly lower inoculum (6 × 104 CFU/mL), which afforded no difference in MICs in our testing. MICs were also performed using iron-depleted cation-adjusted Mueller–Hinton broth, except as mentioned elsewhere, using a standard protocol used with other siderophore-containing antibiotics.

PBP Binding Kinetics.

A method was adapted from the work using purified, soluble P. aeruginosa PBP3 and bocillin, a fluorescent β-lactam and substrate.30 Reactions were conducted in 10 mM phosphate-buffered saline at pH 7.4 using 1.6 μM P. aeruginosa PBP3 incubated with increasing concentrations of 1. To ensure that equilibrium between 1 and PBP3 occurred, the enzyme was preincubated with the compound for 20 min at 37 °C before addition of 50 μM bocillin and then incubated for an additional 20 min. The reactions were stopped by adding an SDS-PAGE loading dye and boiling for 2 min. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and the gel was illuminated at λ = 365 nm and imaged with a Fotodyne gel imaging system. ImageJ analysis software was used to assign fluorescence intensity (FI). The IC50 was calculated as the concentration of 1 required to reduce the FI of the bocillin-labeled protein by 50%.

β-Lactamase Stability Testing.

Steady-state reactions were followed with purified enzymes (KPC-2, OXA-23, OXA-24, PER-2, PDC-3, NDM-1, VIM-2, and IMP-1) using an Agilent diode array spectrophotometer (model 8453) as previously described.31 Assays were performed at 25 °C (room temperature) using either 10 mM PBS, pH 7.4 (KPC-2, PER-2, and PDC-3), 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer supplemented with 20 mM sodium bicarbonate (OXA-23, OXA-24), or 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 0.2 M NaCl, 50 μg/mL bovine serum albumin, and 50 μM Zn (NDM-1, VIM-2, and IMP-1).

Compound 1 was used as a substrate at excess molar concentrations to establish pseudo-first-order kinetics and imipenem (IMI) was used as a control. The following extinction coefficients were used: 1, Δε336 = −5500 M−1 cm−1; IMI, Δε300 = −9000 M−1 cm−1. For velocity determinations, a 1 cm path length quartz cuvette was employed. A nonlinear least square fit of the data (Henri–Michaelis–Menten equation) using Origin 8.1 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA) was employed to obtain the steady-state kinetic parameters Vmax, kcat, and Km according to eqs 1 and 2

| (1) |

| (2) |

Summary of Rodent PK Screening.

Species.

CD-1 mouse species were used.

Protocol Summary for PK in Rodents (In-Life and Bioanalysis).

For plasma sample collection from mice (parallel sampling), compound 1 was administered to groups of 24 animals. Blood aliquots (300–400 μL) are collected via cardiac puncture from individual mice anesthetized with isoflurane vapor. For untreated control animals, blood was collected from anesthetized animals by cardiac puncture. Blood was drawn into tubes coated with lithium heparin or K2EDTA, mixed gently, then kept on ice and centrifuged at 2500 × g for 15 min at 4 °C in 1 h of collection. The plasma was then harvested and kept frozen at −70 °C until further processing.

Quantitative Bioanalysis (Plasma).

The plasma samples are processed using acetonitrile precipitation and analyzed by HPLC-MS/MS.

A plasma calibration curve with an internal standard was generated. Aliquots of drug-free plasma were spiked with the test compound at the specified concentration levels. The spiked plasma samples were processed together with the unknown plasma samples using the same procedure. The processed plasma samples are stored at −70 °C until HPLC-MS/MS analysis at which time peak areas were recorded, and the concentrations of the test compound in the unknown plasma samples were determined using the respective calibration curve. The reportable linear range of the assay is determined along with the lower limit of quantitation (LLQ).

Pharmacokinetics.

Plots of plasma concentration of the compound versus time were constructed. The fundamental pharmacokinetic parameters of each compound after intravenous and oral dosing (AUClast, AUCINF, T1/2, Cl, Vz, Vss, Tmax, and Cmax) were obtained from the noncompartmental analysis (NCA) of the plasma data using WinNonlin. The oral bioavailability will be calculated.

Animal use complies with the International Guiding Principles for Biomedical Research (CIOMS) and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) that operates in accordance with “Regulation for Establishing the Committee of Care and Use of Laboratory Animals”. The facility and our procedures have been fully accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International (AAALAC International) in 2014 and 2017 (#001553). We have a current Foreign Assurance from the Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare (#A5890-01), issued by the PHS/NIH for vertebrate animal studies.

Structure Determination.

His-tagged P. aeruginosa PBP3 was expressed, purified, and crystallized as described previously.32 To obtain the complex of PBP3, compound 1 was soaked into apo PBP3 crystals for 15 min before freezing the crystal in liquid nitrogen. In these experiments, 5 mM 1 in mother liquor for 15 min was used for the soaking experiments.

A 2.4 Å resolution diffraction data set was collected at the SSRL synchrotron in Stanford and processed using HKL-3000 (data collection statistics are listed in Table 4).33 The structure was solved by Molecular Replacement using PHASER34 with the PBP3 protein coordinates as the starting model.33 The structure was refined using REFMAC5,35 and model building was carried out using COOT.36 After refining the protein coordinates, strong difference density was present in the active site for the 1 compound (Figure 2). Topology and parameter files for an acylated 1 ligand were generated using PRODRG;37 coordinates for 1 were included in subsequent cycles of refinement, being covalently attached to S294. The final model included PBP3 residues 53–491 and 501–560, a single 1 ligand, and 84 water molecules and was refined to an R factor/Rfree of 0.182/0.236 (additional refinement statistics in Table 4). Figures were generated using Pymol (www.pymol.org). The coordinates and structure factors of the PBP3:YU253434 complex were deposited with the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID = 6VOT). Authors will release the atomic coordinates upon article publication.

Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF) to Probe 1 Binding to PBP3.

DSF experiments were carried out with the purified PBP3 at 3 μM protein concentration in 14 mM Tris pH 8.0, 280 mM NaCl, 7% glycerol, 10X SYPRO Orange, and with or without 1 mM 1. As a positive control, 0.2 mM ceftazidime was used. The negative control reaction without ligands also included 1% DMSO to match the DMSO concentration in the ligand containing experiments. Experiments were carried out in duplicate using a CFX96 Touch real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad), and the temperature was ramped from 25 to 95 °C.

Synthesis.

The reagents and solvents used for synthesis were of reagent-grade quality. Dry solvents were purchased and used as such. All compounds were individually purified by chromatography on silica gel or by recrystallization and were of >95% purity for characterization purposes as determined by LCMS using UV absorption at 220 or 280 nM and/or NMR integration. Each of the synthesis steps has been replicated by more than one individual in the lab. In practice, compounds were not always purified to >95% purity prior to use in the next synthetic step and often crude material was of sufficient purity and was carried forward.

Synthesis of tert-Butyl-(S)-(1-hydrazineyl-3-hydroxy-1-oxopropan-2-yl)carbamate.

To l-Boc-Ser-OMe (25 g, 114 mmol) in methanol (100 mL) was added hydrazine hydrate (25 mL, 402 mmol). The solution was stirred at 50 °C overnight. The following day, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the resulting solid dried under hi-vac to a constant weight to give tert-butyl (S)-(1-hydrazineyl-3-hydroxy-1-oxopropan-2-yl)carbamate (23.4 g, 93.7%). NMR DMSO 9.0 (s, 1H), 6.5 (d, 1 H), 4.8 (s, 1H), 4.2 (s, 2H), 3.9 (m, 1 H), 3.5 (s, 2 H), 1.4 (s, 9H).

Synthesis of tert-Butyl-(S)-(3-hydroxy-1-oxo-1-(2-(2,2,2-trifluoroacetyl)hydrazineyl)propan-2-yl)carbamate.

tert-Butyl-(S)-(1-hydrazineyl-3-hydroxy-1-oxopropan-2-yl)carbamate (25 g, 114 mmol) and S-ethyl trifluorothioacetate (22 mL, 171 mmol) were combined in ethanol (150 mL). The reaction was stirred at room temperature overnight under a stream of nitrogen. The reaction was concentrated further to a thick residue, which was crystallized from Et2O/hexanes to give tert-butyl-(S)-(3-hydroxy-1-oxo-1-(2-(2,2,2-trifluoroacetyl)hydrazineyl)propan-2-yl)carbamate (27.5 g, 76.4%). 1H-NMR DMSO 11.5 (s, 1 H), 10.3 (s, 1H), 6.8 (d, 1H), 4.9 (s, 1H), 4.1 (m, 1 H), 3.6 (d, 2 H), 1.4 (s, 9H).

Synthesis of tert-Butyl-(S)-(3-oxo-1-(2,2,2-trifluoroacetyl)-pyrazolidin-4-yl)carbamate.

tert-Butyl-(S)-(3-hydroxy-1-oxo-1-(2-(2,2,2-trifluoroacetyl)hydrazineyl)propan-2-yl)carbamate (20.0 g, 63.4 mmol) and triphenylphosphine (20.0 g, 76.1 mmol) in THF (200 mL) were cooled in an ice bath. Diethyl azodicarboxylate (31.8 mL, 69.8 mmol, 40% solution in toluene) was added dropwise, keeping the internal temperature below 10 °C. The reaction was allowed to slowly come to room temperature and stirred overnight. The following day, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the residue was taken up in 300 mL of EtOAc. This mixture was extracted with 3 × 100 mL of saturated NaHCO3 solution. The combined aqueous layers were washed with 3 × 100 mL of EtOAc. The aqueous layer was carefully brought to pH 5.0 with 4 M HCl solution to give a white precipitate, which was filtered and air-dried to give tert-butyl-(S)-(3-oxo-1-(2,2,2-trifluoroacetyl)pyrazolidin-4-yl)-carbamate (17.6 g, 93% yield). Mass spectrum [M + H]+(-tBu) = 242.0.

Synthesis of tert-Butyl-(S)-(3-oxopyrazolidin-4-yl)-carbamate (9).

tert-Butyl-(S)-(3-oxo-1-(2,2,2-trifluoroacetyl)-pyrazolidin-4-yl)carbamate (25.7 g, 86.6 mmol) was suspended in 50 mL of H2O, and NaOH solution (124 mL, 1 M solution) was added. The reaction was stirred at room temperature for 5 h at which point all materials were in solution. The reaction was neutralized to pH values between 6 and 7 using 4 M HCl solution. A solid began to precipitate, and the solution was cooled in an ice bath to facilitate precipitation. The solid was filtered, washed with cold water, and air-dried to give tert-butyl-(S)-(3-oxopyrazolidin-4-yl)carbamate (7.3 g, 41.7% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.21 (s, 1H), 7.01 (d, J = 8.89 Hz, 1H), 4.42–4.02 (m, 1H), 3.53–3.19 (m, 2H), 2.90 (t, J = 10.94 Hz, 1H), 1.39 (s, 9H). Mass spectrum [M + H]+ = 202.1.

Synthesis of Allyl-2-(diethoxyphosphoryl)acrylate.

A solution of paraformaldehyde (2.24 g, 74.5 mmol) and piperidine (184 μL, 1.86 mmol) in ethanol (50 mL) was heated at reflux for 1 h. To this was added allyl-2-(diethoxyphosphoryl)acetate (11.0 g, 46.6 mmol), and the solution was refluxed for 72 h, adding additional piperidine (184 μL, 1.86 mmol) and paraformaldehyde (250 mg, 8.3 mmol) after 24 and 48 h. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure, and the reaction was taken up in toluene (60 mL). To this was added p-toluenesulfonic acid monohydrate (140 mg, 0.81 mmol). The reaction was distilled to remove ethanol and toluene. Kugelrohr distillation of the remaining material provided allyl-2-(diethoxyphosphoryl)acrylate (7.37 g, 64% yield), which was stored as a 0.5 M solution in benzene at 0 °C. NMR CDCl3 7.02 (d, 1H), 6.77 (d, 1H), 5.95 (m, 1 H), 5.40 (d, 1H), 5.27 (d, 1H), 4.72 (m, 2H) 4.17 (q, 4H), 1.34 (t, 6H).

Synthesis of Allyl-3-((S)-4-((tert-butoxycarbonyl)ammo)-3-oxopyrazolidin-1-yl)-2-(diethoxyphosphoryl)propanoate (10).

To a suspension of tert-butyl-(S)-(3-oxopyrazolidin-4-yl)carbamate (5.0 g, 24.8 mmol) in DCM (40 mL) was added allyl-2-(diethoxyphosphoryl)acrylate (7.40 g, 29.8 mmol, 0.5 M solution in benzene). The reaction was stirred for 1 h at room temperature. The reaction solution was directly injected into a silica gel column equilibrated with DCM. The column was run at 0–10% MeOH/DCM to give allyl-3-((S)-4-((tert-butoxycarbonyl)amino)-3-oxopyrazolidin-1-yl)-2-(diethoxyphosphoryl)propanoate (11.0 g, 98% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 8.10 (d, J = 89.11 Hz, 1H), 5.93 (ddt, J = 5.77, 11.03, 16.42 Hz, 1H), 5.50–5.22 (m, 2H), 5.14 (d, J = 21.10 Hz, 1H), 4.84–4.65 (m, 2H), 4.59 (d, J = 35.26 Hz, 1H), 4.25–4.10 (m, 4H), 3.91–3.72 (m, 1H), 3.56–2.94 (m, 4H), 1.46 (s, 9H), 1.42–1.19 (m, 6H). Mass spectrum [M + H]+ = 450.2.

Synthesis of 2-Allyl-3-(tert-butyl)-(S)-6-((tert-butoxycarbonyl)amino)-5-oxo-6,7-dihydro-1H,5H-pyrazolo-[1,2-a]pyrazole-2,3-dicarboxylate (11).

Allyl-3-((S)-4-((tert-butoxycarbonyl)amino)-3-oxopyrazolidin-1-yl)-2-(diethoxyphosphoryl)propanoate (4.0 g, 8.94 mmol) was dissolved in anhydrous DCM (55 mL) and cooled to 0 °C. A solution of tert-butyl-2-chloro-2-oxoacetate (1.91 g, 11.6 mmol) in anhydrous DCM (5 mL) was added dropwise. After 5 min, Hunig’s base (4.22 mL, 24.2 mmol) was added dropwise. The reaction was slowly warmed to room temperature. After 2 h, additional tert-butyl-2-chloro-2-oxoacetate (250 mg, 1.5 mmol) was added as a solution in DCM (0.5 mL). The reaction was left to stir at room temperature overnight. The following day, the reaction was diluted with DCM (100 mL) and the reaction was washed with 1 M H2SO4 (75 mL) solution, water (75 mL), and brine (50 mL). The organic layer was dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure to give crude 2-allyl-3-(tert-butyl)-(S)-6-((tert-butoxycarbonyl)-amino)-5-oxo-6,7-dihydro-1H,5H-pyrazolo[1,2-a]pyrazole-2,3-dicarboxylate, which was used as is for the subsequent reaction. 1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 5.92 (ddt, J = 5.75, 10.40, 17.17 Hz, 1H), 5.50–5.21 (m, 2H), 5.11 (s, 1H), 4.77 (s, 1H), 4.69 (dt, J = 1.40, 5.81 Hz, 2H), 4.36 (d, J = 12.07 Hz, 1H), 4.09 (dd, J = 8.19, 16.37 Hz, 1H), 3.91 (d, J = 12.02 Hz, 1H), 2.85 (t, J = 9.86 Hz, 1H), 1.60 (s, 9H), 1.47 (s, 9H). Mass spectrum [M + H]+ = 424.1.

Synthesis of (S)-3-(tert-Butoxycarbonyl)-6-((tert-butoxycarbonyl)amino)-5-oxo-6,7-dihydro-1H,5H-pyrazolo-[1,2-a]pyrazole-2-carboxylic Acid (12).

2-Allyl-3-(tert-butyl)-(S)-6-((tert-butoxycarbonyl)amino)-5-oxo-6,7-dihydro-1H,5H-pyrazolo-[1,2-a]pyrazole-2,3-dicarboxylate (3.79 g, 8.95 mmol) was dissolved in ACN (100 mL), flushed with N2, and cooled to 0 °C. Triethylsilane (1.72 mL, 10.7 mmol) was added dropwise followed by Pd(PPh3)4 (827 mg, 0.7 mmol). The reaction was stirred at 0 °C for 30 min, then warmed to room temperature, and stirred for an additional 4 h. The reaction was quenched by addition of 0.1 M HCl solution (10 mL) and stirred for 30 min. The reaction was diluted with EtOAc (250 mL), and the aqueous layer was discarded. The organics were extracted with 50% saturated NaHCO3 solution (2 × 100 mL). The combined aqueous layers were neutralized with 1 M H2SO4 and extracted with EtOAc (3 × 100 mL). The combined organics were washed with brine, dried over MgSO4, and concentrated under reduced pressure to give (S)-3-(tert-butoxycarbonyl)-6-((tert-butoxycarbonyl)amino)-5-oxo-6,7-dihydro-1H,5H-pyrazolo[1,2-a]pyrazole-2-carboxylic acid (2.22 g, 65% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 5.16 (s, 1H), 4.78 (s, 1H), 4.54–4.37 (m, 1H), 4.11 (d, J = 11.07 Hz, 1H), 3.91 (d, J = 13.07 Hz, 1H), 2.87 (t, J = 10.06 Hz, 1H), 1.67 (s, 9H), 1.47 (s, 9H). Mass spectrum [M + H]+ = 384.2.

Synthesis of tert-Butyl-(2-(5,6-bis((4-methoxybenzyl)oxy)-1,3-dioxoisoindolin-2-yl)ethyl)arbamate.

To a solution of 5,6-bis((4-methoxybenzyl)oxy)isobenzofuran-1,3-dione (5.0 g, 11.9 mmol) in EtOH (50 mL) was added N-Boc-ethylenediamine (3.81 g, 23.8 mmol). The solution was heated to reflux for 3 h. The reaction was cooled to room temperature to yield a white precipitate. Water (25 mL) was added to the reaction, the mixture was cooled to 0 °C, and the solid was filtered and air-dried to give tert-butyl (2-(5,6-bis((4-methoxybenzyl)oxy)-1,3-dioxoisoindolin-2-yl)ethyl)-carbamate (4.26 g, 64% yield). Mass spectrum [M + H]+ = 507.2 (-tBu).

Synthesis of 2-(2-Aminoethyl)-5,6-dihydroxyisoindoline-1,3-dione (13).

tert-Butyl-(2-(5,6-bis((4-methoxybenzyl)oxy)-1,3-dioxoisoindolin-2-yl)ethyl)carbamate (3.85 g, 6.84 mmol) was suspended in DCM (150 mL) and cooled to 0 °C. To this was added triethylsilane (5.46 mL, 34.2 mmol) followed by trifluoroacetic acid (26 mL, 340 mmol). Stirring was continued at 0 °C for 1 h. The reaction was diluted with toluene (50 mL) to give a white solid, which was filtered and air-dried to give 2-(2-aminoethyl)-5,6-dihydroxyisoindoline-1,3-dione (2.11 g, 96% yield) as the TFA salt. Mass spectrum [M + H]+ = 223.0.

Synthesis of Intermediate tert-Butyl-(S)-6-((tert-butoxycarbonyl)amino)-2-((2-(5,6-dihydroxy-1,3-dioxoisoindolin-2-yl)ethyl)carbamoyl)-5-oxo-6,7-dihydro-1H,5H-pyrazolo[1,2-a]pyrazole-3-carboxylate (14).

Starting material carboxylic acid 12 (694 mg, 1.81 mmol) was dissolved in dichloromethane (5 mL) with catalytic DMF and cooled in an ice bath. To this solution was added oxalyl chloride as a solution in dichloromethane (1.1 mL of 2.0 M solution, 2.2 mmol), and the reaction was stirred for 1 h. In a second flask, the amine 2-(2-aminoethyl)-5,6-dihydroxyisoindoline-1,3-dione, 13 (608 mg, 1.81 mmol), was dissolved in dry acetonitrile (10 mL) cooled in an ice bath and treated with MSTFA (2.0 mL, 10.9 mmol) and then Hunig’s base (1.26 mL, 7.24 mmol). After stirring for 30 min, all the amine was in solution. The dichloromethane solution was then added to the amine solution with the use of a syringe, and the combined reaction mixture was stirred for 2 h. Product formation was confirmed by TLC. The reaction was poured into ethyl acetate, acidified and washed with 0.3 N sulfuric acid, extracted two times with ethyl acetate and combined organics washed with brine to give 1.92 g of a crude yellow solid. Chromatography MPLC (40–70% (ethyl acetate/methanol/acetic acid, 93.8:6:0.2)) in DCM provides a product that elutes at ~60%. The product tert-butyl-(S)-6-((tert-butoxycarbonyl)amino)-2-((2-(5,6-dihydroxy-1,3-dioxoisoindolin-2-yl)ethyl)carbamoyl)-5-oxo-6,7-dihydro-1H,5H-pyrazolo[1,2-a]-pyrazole-3-carboxylate 14 was obtained as a yellow foam (408 mg, 38%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 8.62 (d, J = 5.85 Hz, 1H), 7.19 (s, 2H), 5.25 (s, 1H), 4.75 (s, 1H), 4.47 (dd, J = 3.63, 14.10 Hz, 1H), 4.01 (s, 1H), 3.78 (d, J = 22.87 Hz, 3H), 3.63 (s, 2H), 2.89–2.73 (m, 1H), 1.49 (s, 9H), 1.46 (s, 9H). Mass spectrum [M + H]+ = 588.2.

Synthesis of Intermediate (S)-6-Amino-2-((2-(5,6-dihydroxy-1,3-dioxoisoindolm-2-yl)ethyl)carbamoyl)-5-oxo-6,7-dihydro-1H,5H-pyrazolo[1,2-a]pyrazole-3-carboxylic Acid (15).

Starting material 14 (397 mg, 0.68 mmol) was dissolved in dichloromethane (10 mL), and triethyl silane (540uL, 3.4 mmol) was added. The reaction was cooled in an ice bath, and trifluoroacetic acid (5.0 mL, 68 mmol) was added. The cooled reaction was stirred for 1.5 h and at room temperature for 15 min. Toluene (15 mL) was added, and the reaction was evaporated to dryness to give the product (S)-6-amino-2-((2-(5,6-dihydroxy-1,3-dioxoisoindolin-2-yl)ethyl)carbamoyl)-5-oxo-6,7-dihydro-1H,5H-pyrazolo[1,2-a]pyrazole-3-carboxylic acid, 15, as a yellow foam that was used crude in the next reaction. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.35 (s, 2H), 8.63 (s, 2H), 8.31–8.12 (m, 1H), 7.13 (d, J = 1.84 Hz, 2H), 4.92–4.51 (m, 1H), 4.15 (d, J = 12.88 Hz, 1H), 4.06–3.77 (m, 2H), 3.77–3.48 (m, 3H), 3.48–3.22 (m, 2H), 3.08 (td, J = 7.74, 10.89, 11.57 Hz, 1H). Mass spectrum [M + H]+ = 432.0.

Synthesis of Intermediate (S,Z)-6-(2-(((1-(tert-Butoxy)-2-methy-1-oxopropan-2-yl)oxy)immo)-2-(2-(tritylammo)-thiazol-4-yl)acetamido)-2-((2-(5,6-dihydroxy-1,3-dioxoisoindolin-2-yl)ethyl)carbamoyl)-5-oxo-6,7-dihydro-1H,5H-pyrazolo[1,2-a]pyrazole-3-carboxylic Acid (17).

Commercial starting material (Z)-2-(((1-(tert-butoxy)-2-methyl-1-oxopropan-2-yl)oxy)imino)-2-(2-(tritylamino)thiazol-4-yl)acetic acid 16 (436 mg, 0.76 mmol) in dry dichloromethane and catalytic DMF was cooled in an ice bath and treated with oxalyl chloride (382 uL of 2.0 M solution, 0.76 mmol) and stirred for 1 h. In a second flask, starting material 15 (299 mg, 0.69 mmol) in acetonitrile (4 mL) was cooled in an ice bath and MSTFA (769 uL, 4.2 mmol) and Hunig’s base (472 uL, 2.7 mmol) was added. After stirring for 20 min, all of the starting material 15 was in solution. During this time, the dichloromethane from the acid chloride-forming reaction was evaporated and placed on a high vacuum to give a colorless foam. This foam was dissolved in dry DCM (5 mL) and added to the MSTFA-treated amine followed by the addition of Hunig’s base (250 uL, 1.4 mmol). The reaction was allowed to warm to room temperature over 1 h and stirred for an additional 1 h. Ethyl acetate was added, and the solution was washed with 0.3 N sulfuric acid, water, and then brine to give the crude product (S,Z)-6-(2-(((1-(tert-butoxy)-2-methyl-1-oxopropan-2-yl)oxy)imino)-2-(2-(tritylamino)-thiazol-4-yl)acetamido)-2-((2-(5,6-dihydroxy-1,3-dioxoisoindolin-2-yl)ethyl)carbamoyl)-5-oxo-6,7-dihydro-1H,5H-pyrazolo[1,2-a]-pyrazole-3-carboxylic acid 17 as a yellow foam that was used directly in the next reaction. Mass spectrum [M + H]+ = 985.2.

Synthesis of (S,Z)-6-(2-(2-Aminothiazol-4-yl)-2-(((2-carboxypropan-2-yl)oxy)imino)acetamido)-2-((2-(5,6-dihydroxy-1,3-dioxoisoindolin-2-yl)ethyl)carbamoyl)-5-oxo-6,7-dihydro-1H,5H-pyrazolo[1,2-a]pyrazole-3-carboxylic Acid (1).

The starting material 10 (1.24 g, 1.26 mmol), crude from the previous reaction, was dissolved in dichloromethane (20 mL), and triethyl silane (1.0 mL, 6.3 mmol) was added. The solution was cooled in an ice bath, and trifluoroacetic acid (9.6 mL, 126 mmol) was added. It was removed from the ice bath after 30 min, and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 h. Toluene (25 mL) was added, and the reaction mixture was evaporated to dryness. The crude reaction mixture was dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide, diluted with water, and chromatographed using reverse-phase C18 MPLC eluting with 0 to 30% acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid in water with 0.1% formic acid to give the product (S,Z)-6-(2-(2-aminothiazol-4-yl)-2-(((2-carboxypropan-2-yl)oxy)imino)acetamido)-2-((2-(5,6-dihydroxy-1,3-dioxoisoindolin-2-yl)ethyl)carbamoyl)-5-oxo-6,7-dihydro-1H,5H-pyrazolo[1,2-a]pyrazole-3-carboxylic acid, 1, as a yellow powder after lyophilization (333 mg, 38%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.53 (s, 1H), 10.32 (s, 3H), 8.86 (d, J = 8.44 Hz, 1H), 7.29 (d, J = 2.46 Hz, 2H), 7.13 (s, 3H), 6.94 (s, 1H), 5.03 (dt, J = 8.24, 11.52 Hz, 1H), 4.13 (d, J = 12.40 Hz, 1H), 3.98–3.75 (m, 2H), 3.58 (t, J = 5.93 Hz, 2H), 3.15–2.99 (m, 1H), 1.41 (d, J = 1.58 Hz, 6H). Mass spectrum [M + H]+ = 687.1. HRMS (ESI/QTOF) calcd for C27H26N8O12S1 682.1391, found [M + H]+ 687.1469.

Synthesis of (S,Z)-6-(2-(2-Aminothiazol-4-yl)-2-(((2-carboxypropan-2-yl)oxy)imino)acetamido)-5-oxo-2-(phenethylcarbamoyl)-6,7-dihydro-1H,5H-pyrazolo[1,2-a]pyrazole-3-carboxylic Acid (2).

Compound 2 was synthesized in a manner parallel to the synthesis of 1 but only using phenethyl amine rather than amine 13. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.48(s, sH), 8.83 (d, J = 8.26 Hz, 1H), 8.04 (q, J = 4.98, 5.69 Hz, 1H), 7.28–7.17 (m, 3H), 7.18–7.09 (m, 4H), 6.87 (s, 1H), 4.96 (dt, J = 8.18, 11.35 Hz, 1H), 4.15 (d, J = 12.67 Hz, 1H), 3.90–3.67 (m, 2H), 3.33–3.13 (m, 3H), 3.13–2.97 (m, 1H), 2.72–2.59 (m, 3H), 1.44–1.26 (m, 6H). Mass spectrum [M + H]+ = 586.1. HRMS (ESI/QTOF) calcd for C25H27N7O8S1 585.1642, found [M + H]+ 586.1617.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

R.A.B.: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Nos. R01AI100560, R01AI063517, and R01AI072219. This study was also supported in part by funds and/or facilities provided by the Cleveland Department of Veterans Affairs, Award Nos. 1I01BX002872 to K.M.P.-W. and 1I01BX001974 to R.A.B. from the Biomedical Laboratory Research & Development Service of the VA Office of Research and Development, and the Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center VISN 10 (R.A.B.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the Department of Veterans Affairs. L.K.L.: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the NIH under Award No. K08AI112506. B.M.K.: Research reported in this publication was supported by a grant from the NIH, R01AI090155. R.A.B. wishes to gratefully thank the Antimicrobial Resistance Leadership Group (ARLG) for the use of the isolates. The research described in this publication is supported, at least in part, by a grant from the NIH through Duke University and the findings, opinions, and recommendations expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of Duke University or the NIH. Bacterial isolates provided herein and identified as “ARLG” were provided by the ARLG. This study is also supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the NIH under Award No. UM1AI104681. F.V.D.A. wishes also to thank Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) for help with data collection. Use of the SSRL, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Contract No. DE-AC02-76SF00515. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research and by the NIH, National Institute of General Medical Sciences (including P41GM103393). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIGMS or the NIH.

Funding

M.S.P.: Financial support was provided by the Program in Innovative Therapeutics for Connecticut’s Health grant by the Connecticut Bioscience Innovation Fund, administered by the Connecticut Innovations and Yale University.

ABBREVIATIONS USED

- PBP

penicillin-binding protein

- MIC

minimal inhibitory concentration

- AMR

antimicrobial resistance

- MDR

multidrug-resistant

- MSTFA

N-methyl-N-(trimethylsilyl)-trifluoroacetamide

- DSF

differential scanning fluorimetry

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- LCMS

liquid chromatography mass spectrometry

- DMSO

dimethylsulfoxide

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00255.

Additional tables and figures representing toxicity values, mouse plasma PK, chemistry methods, compound modeling, and β-lactamase genes of isolates tested, molecular formula strings, and MICs (PDF)

Accession Codes

PDB code for P. aeruginosa PBP3 with bound YU253434 is 6VOT. Authors will release the atomic coordinates upon article publication.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00255

Contributor Information

Joel A. Goldberg, Research Service, Louis Stokes Cleveland Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Cleveland, Ohio 44106, United States

Ha Nguyen, Department of Biochemistry, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio 44106, United States.

Vijay Kumar, Department of Biochemistry, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio 44106, United States.

Elizabeth J. Spencer, Yale Center for Molecular Discovery, West Haven, Connecticut 06516, United States

Denton Hoyer, Yale Center for Molecular Discovery, West Haven, Connecticut 06516, United States.

Emma K. Marshall, Research Service, Louis Stokes Cleveland Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Cleveland, Ohio 44106, United States

Anna Cmolik, Research Service, Louis Stokes Cleveland Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Cleveland, Ohio 44106, United States.

Margaret O’Shea, Research Service, Louis Stokes Cleveland Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Cleveland, Ohio 44106, United States.

Steven H. Marshall, Research Service, Louis Stokes Cleveland Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Cleveland, Ohio 44106, United States

Andrea M. Hujer, Research Service, Louis Stokes Cleveland Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Cleveland, Ohio 44106, United States; Department of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio 44106, United States

Kristine M. Hujer, Research Service, Louis Stokes Cleveland Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Cleveland, Ohio 44106, United States; Department of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio 44106, United States

Susan D. Rudin, Research Service, Louis Stokes Cleveland Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Cleveland, Ohio 44106, United States; Department of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio 44106, United States

T. Nicholas Domitrovic, Research Service, Louis Stokes Cleveland Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Cleveland, Ohio 44106, United States; Department of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio 44106, United States.

Christopher R. Bethel, Research Service, Louis Stokes Cleveland Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Cleveland, Ohio 44106, United States

Krisztina M. Papp-Wallace, Research Service, Louis Stokes Cleveland Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Cleveland, Ohio 44106, United States; Department of Biochemistry and Department of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio 44106, United States

Latania K. Logan, Department of Pediatrics, Rush University Medical Center, Rush Medical College, Chicago, Illinois 60612, United States; Cook County Health and Hospital Systems, Chicago, Illinois 60612, United States

Federico Perez, Research Service and Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Center, Louis Stokes Cleveland Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Cleveland, Ohio 44106, United States; Department of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio 44106, United States.

Michael R. Jacobs, Department of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio 44106, United States; Department of Pathology, University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, Division of Clinical Microbiology, Cleveland, Ohio 44106, United States

David van Duin, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27514, United States.

Barry M. Kreiswirth, Center for Discovery and Innovation, Hackensack Meridian Health, Nutley, New Jersey 07601, United States

Robert A. Bonomo, Research Service and Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Center, Louis Stokes Cleveland Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Cleveland, Ohio 44106, United States; Department of Biochemistry, Department of Medicine, and Departments of Pharmacology, Molecular Biology & Microbiology, and Proteomics & Bioinformatics, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio 44106, United States; CWRU-Cleveland VAMC Center for Antimicrobial Resistance and Epidemiology (Case VA CARES), Cleveland, Ohio 44106, United States.

Mark S. Plummer, Yale Center for Molecular Discovery, West Haven, Connecticut 06516, United States

Focco van den Akker, Department of Biochemistry, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio 44106, United States.

REFERENCES

- (1).(a) Ctrol and Prevention (2019) Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2019 AR Threats Report https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/biggest-threats.html (accessed Mar 11, 2020) [Google Scholar]; (b) Cassini A; Högberg LD; Plachouras D; Quattrocchi A; Hoxha A; Simonsen GS; Colomb-Cotinat M; Kretzschmar ME; Devleesschauwer B; Cecchini M; Ouakrim DA; Oliveira TC; Struelens MJ; Suetens C; Monnet DL; Burden of AMR Collaborative Group. Attributable deaths and disability-adjusted life-years caused by infections with antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the EU and the European Economic Area in 2015: a population-level modelling analysis. Lancet Infectious Disease 2019, 19, 56–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).World Health Organization. Antimicrobial Resistance: Global Report on Surveillance, 2014. https://www.who.int/antimicrobial-resistance/publications/surveillancereport/en/ (accessed Mar 11, 2020).

- (3).Spellberg B; Guidos R; Gilbert D; Bradley J; Boucher HW; Scheld WM; Bartlett JG; Edwards J Jr.; The Infectious Diseases Society of America. The epidemic of antibiotic-resistant infections: a call to action for the medical community from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis 2008, 46, 155–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Boucher HW; Talbot GH; Bradley JS; Edwards JE; Gilbert D; Rice LB; Scheld M; Spellberg B; Bartlett J Bad bugs, no drugs: no ESKAPE! An update from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis 2009, 48, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).World Health Organization. Global Priority List of Antibiotic-resistant Bacteria to Guide Research, Discovery, and Development of New Antibiotics, 2017. https://www.who.int/medicines/publications/global-priority-list-antibiotic-resistant-bacteria/en/ (accessed Mar 11, 2020).

- (6).Peleg AY; Hooper DC Hospital-acquired infections due to Gram-negative bacteria. N. Engl. J. Med 2010, 362, 1804–1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Sydnor ERM; Perl TM Hospital epidemiology and infection control in acute-care settings. Clin. Microbiol. Rev 2011, 24, 141–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Hassani M The crisis of Gram-negative bacterial resistance: is there any hope for ESKAPE? Clin. Res. Infect. Dis 2014, 1, 1005–1009. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Silver LL Challenges of antibacterial discovery. Clin. Microbiol. Rev 2011, 24, 71–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Payne DJ; Gwynn MN; Holmes DJ; Pompliano DL Drugs for bad bugs: confronting the challenges of antibacterial discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 2007, 6, 29–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).So AD; Gupta N; Brahmachari SK; Chopra I; Munos B; Nathan C; Outterson K; Paccaud JP; Payne DJ; Peeling RW; Spigelman M; Weigelt J Towards new business models for R&D for novel antibiotics. Drug Resist. Updat 2011, 14, 88–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Livermore DM Multiple mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: our worst nightmare? Clin. Infect. Dis 2002, 34, 634–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Tomas M; Doumith M; Warner M; Turton JF; Beceiro A; Bou G; Livermore DM; Woodford N Efflux pumps, OprD porin, AmpC beta-lactamase, and multiresistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from cystic fibrosis patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2010, 54, 2219–2224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Ternansky RJ; Draheim SE [4.3.0] Pyrazolidinones as potential antibacterial agents. Tetrahedron Lett. 1988, 29, 6569–6572. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Allen NE; Hobbs JN Jr.; Preston DA; Turner JR; Wu CYE Antibacterial properties of the bicyclic pyrazolidinones. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 1990, 43, 92–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Ternansky RJ; Draheim SE Structure-activity relationship within a series of pyrazolidinone antibacterial agents. 1. Effect of nuclear modification on in vitro activity. J. Med. Chem 1993, 36, 3219–3223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Ternansky RJ; Draheim SE; Pike AJ; Counter FT; Eudaly JA; Kasher JS Structure-activity relationship within a series of pyrazolidinone antibacterial agents. 2 Effect of side-chain modification on in vitro activity and pharmacokinetic parameters. J. Med. Chem 1993, 36, 3224–3229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Boyd DB Application of the hypersurface iterative projection method to bicyclic pyrazolidinone antibacterial agents. J. Med. Chem 1993, 36, 1443–1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Cornelis P; Matthijs S; Van Oeffelen L Iron uptake regulation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biometals 2009, 22, 15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).(a) Wilson BR; Bogdan AR; Miyazawa M; Hashimoto K; Tsuji Y Siderophores in iron metabolism: from mechanism to therapy potential. Trends Mol. Med 2016, 22, 1077–1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Schalk IJ; Mislin GLA Bacterial iron uptake pathways: gates for the import of bactericide compounds. J. Med. Chem 2017, 60, 4573–4576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Luscher A; Moynié L; Auguste PS; Bumann D; Mazza L; Pletzer D; Naismith JH; Köhler T TonB-Dependent receptor repertoire of Pseudomonas aeruginosa for uptake of siderophore-drug conjugates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2018, 62, e00097–e00118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Hackel MA; Tsuji M; Yamano Y; Echols R; Karlowsky JA; Sahm DF In vitro activity of the siderophore cephalosporin, Cefiderocol, against a recent collection of clinically relevant Gram-negative bacilli from North America and Europe, including carbapenem-nonsusceptible isolates (SIDERO-WT-2014 Study). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2017, 61, e00093–e00117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).(a) Starr J; Brown MF; Aschenbrenner L; Caspers N; Che Y; Gerstenberger BS; Huband M; Knafels JD; Megan Lemmon M; Li C; McCurdy SP; McElroy E; Rauckhorst MR; Tomaras AP; Young JA; Zaniewski RP; Shanmugasundaram V; Han S Siderophore receptor-mediated uptake of lactivicin analogues in Gram-negative bacteria. J. Med. Chem 2014, 57, 3845–3855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Baudart M-G; Hennequin LF Synthesis and biological activity of C-3′ ortho dihydroxyphthalimido cephalosporins. J Antibiot. 1993, 46, 1458–1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Evans SR; Tran TTT; Hujer AM; Hill CB; Hujer KM; Mediavilla JR; Manca C; Domitrovic TN; Perez F; Farmer M; Pitzer KM; Wilson BM; Kreiswirth BN; Patel R; Jacobs MR; Chen L; Fowler VG; Chambers HF; Bonomo RA; Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group (ARLG). Rapid molecular diagnostics to inform empiric use of Ceftazidime/Avibactam and Ceftolozane/Tazobactam against Pseudomonas aeruginosa: PRIMERS IV. Clin. Infect. Dis 2019, 68, 1823–1830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Henig O; Cober E; Richter SS; Perez F; Salata RA; Kalayjian RC; Watkins RR; Marshall S; Rudin SD; Domitrovic TN; Hujer AM; Hujer KM; Doi Y; Evans S; Fowler VG Jr.; Bonomo RA; van Duin D; Kaye KS; Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group. A prospective observational study of the epidemiology, management, and outcomes of skin and soft tissue infections due to carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae. Open Forum Infect Dis 2017, 4, ofx157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Logan LK; Hujer AM; Marshall SH; Domitrovic TN; Rudin SD; Zheng X; Qureshi NK; Hayden MK; Scaggs FA; Karadkhele A; Bonomo RA Analysis of β-lactamase resistance determinants in enterobacteriaceae from Chicago children: A multicenter survey. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2016, 60, 3462–3469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Evans SR; Hujer AM; Jiang H; Hujer KM; Hall T; Marzan C; Jacobs MR; Sampath R; Ecker DJ; Manca C; Chavda K; Zhang P; Fernandez H; Chen L; Mediavilla JR; Hill CB; Perez F; Caliendo AM; Fowler VG Jr.; Chambers HF; Kreiswirth BN; Bonomo RA; Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group. Rapid molecular diagnostics, antibiotic treatment decisions, and developing approaches to inform empiric therapy: PRIMERS I and II. Clin. Infect. Dis 2016, 62, 181–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Page MGP; Dantier C; Desarbre E In vitro properties of BAL30072, a novel siderophore sulfactam with activity against multiresistant Gram-negative bacilli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2010, 54, 2291–2302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Ito A; Nishikawa T; Matsumoto S; Yoshizawa H; Sato T; Nakamura R; Tsuji M; Yamano Y Siderophore cephalosporin Cefiderocol utilizes ferric iron transporter systems for antibacterial activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2016, 60, 7396–7401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Papp-Wallace KM; Senkfor B; Gatta J; Chai W; Taracila MA; Shanmugasundaram V; Han S; Zaniewski RP; Lacey BM; Tomaras AP; Skalweit MJ; Harris ME; Rice LB; Buynak JD; Bonomo RA Early insights into the interactions of different β-lactam antibiotics and β-lactamase inhibitors against soluble forms of Acinetobacter baumannii PBP1a and Acinetobacter sp. PBP3. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2012, 56, 5687–5692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Levitt PS; Papp-Wallace KM; Taracila MA; Hujer AM; Winkler ML; Smith KM; Xu Y; Harris ME; Bonomo RA Exploring the role of a conserved class A residue in the Ω-loop of KPC-2 β-lactamase: A mechanism for ceftazidime hydrolysis. J. Biol. Chem 2012, 287, 31783–31793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Han S; Zaniewski RP; Marr ES; Lacey BM; Tomaras AP; Evdokimov A; Miller JR; Shanmugasundaram V Structural basis for effectiveness of siderophore-conjugated monocarbams against clinically relevant strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci USA. 2010, 107, 22002–22007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Minor W; Cymborowski M; Otwinowski Z; Chruszcz M HKL-3000: the integration of data reduction and structure solution–from diffraction images to an initial model in minutes. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr 2006, 62, 859–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).McCoy AJ; Grosse-Kunstleve RW; Adams PD; Winn MD; Storoni LC; Read RJ Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr 2007, 40, 658–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Murshudov GN; Skubák P; Lebedev AA; Pannu NS; Steiner RA; Nicholls RA; Winn MD; Long F; Vagin AA REFMAC5 for the refinement of macromolecular crystal structures. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr 2011, 67, 355–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Emsley P; Cowtan K Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr 2004, 60, 2126–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Schüttelkopf AW; van Aalten DMF PRODRG: a tool for high-throughput crystallography of protein-ligand complexes. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr 2004, 60, 1355–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Sparbier K; Schubert S; Weller U; Boogen C; Kostrzewa M Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry-based functional assay for rapid detection of resistance against beta-lactam antibiotics. J. Clin. Microbiol 2012, 50, 927–937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.