Abstract

Objective:

Early detection of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) can increase access to treatment and assist in advance care planning. However, the development of a diagnostic system that d7oes not heavily depend on cognitive testing is a major challenge. We describe a diagnostic algorithm based solely on gait and machine learning to detect MCI and AD from healthy.

Methods:

We collected “single-tasking” gait (walking) and “dual-tasking” gait (walking with cognitive tasks) from 32 healthy, 26 MCI, and 20 AD participants using a computerized walkway. Each participant was assessed with the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). A set of gait features (e.g., mean, variance and asymmetry) were extracted. Significant features for three classifications of MCI/healthy, AD/healthy, and AD/MCI were identified. A support vector machine model in a one-vs.-one manner was trained for each classification, and the majority vote of the three models was assigned as healthy, MCI, or AD.

Results:

The average classification accuracy of 5-fold cross-validation using only the gait features was 78% (77% F1-score), which was plausible when compared with the MoCA score with 83% accuracy (84% F1-score). The performance of healthy vs. MCI or AD was 86% (88% F1-score), which was comparable to 88% accuracy (90% F1-score) with MoCA.

Conclusion:

Our results indicate the potential of machine learning and gait assessments as objective cognitive screening and diagnostic tools.

Significance:

Gait-based cognitive screening can be easily adapted into clinical settings and may lead to early identification of cognitive impairment, so that early intervention strategies can be initiated.

Keywords: Cognitive decline, machine learning, gait data, Alzheimer’s disease, dual-task assessment

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most common cause of dementia, is one of the most prevalent causes of mortality in the United States. In 2018, AD accounted for 30.5 deaths per 100,000 people nationwide [1]. Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is abnormal cognitive decline beyond expected decline of normal aging that represents a prodromal stage of AD with an estimated community prevalence of 21% for those over age 65 [2]. The rate of progression to AD in people with MCI is an estimated 10-15% per year, which is much higher than the rate of 1% to 2% seen in general population [3] [4]. However, early diagnosis remains a difficult task. By the time AD is diagnosed, sufficient neuronal injury has occurred to the extent that reversal of the disease is unlikely [5]. In this paper, we developed a new method for early diagnosis of MCI and AD that coupled with emerging therapies, could help intervene and slow, or perhaps even halt, the progression [6].

Current clinical practices typically use cognitive tests, such as Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) [7], to screen patients for MCI and AD. The challenge with these cognitive tests is that they may not be efficient at identifying early-stages of cognitive impairment because when applied to general populations, the cutoff scores have to be adjusted for each individual according to education level and cultural background and may be less sensitive to subtle cognitive changes and activities of daily living in the earlier stages of cognitive impairment [8]. Moreover, these tests require training for proper administration and are usually performed after cognitive decline becomes noticeable or is offered as a complaint by the patient or a family member. Less than half of older adults are currently screened and diagnosed for cognitive decline, and impairment is most frequently diagnosed at the mild-to-moderate stages of disease [9]. The focus of this study was to develop an MCI and AD detection method that can be performed by primary providers who may be untrained or uncomfortable performing cognitive assessments [10].

Gait has been shown to have a robust relationship with cognition [11] [12]. Unlike cognitive tests, gait assessment is a common component of physical examinations across a variety of medical disciplines. Walking is a process that requires memory, executive function, motor coordination, and attention, and hence dual-task gait, which refers to walking while performing an attention-demanding task, has shown to be affected more in individuals with cognitive impairment than in those without cognitive deficits [13]. Therefore, the dual-task assessment has been used to detect individuals with an abnormal cognitive decline via assessment of decline in performance from single-(e.g. walking) to dual-task walking tests (e.g., walking while subtracting) [14]. However, most studies investigated the association between gait performance and cognitive decline using statistical approaches [15] [16]. They used methods such as analysis of variance to identify aspects of gait that significantly change with increased cognitive load without providing an aggregated model to discriminate AD or MCI subjects from the healthy controls. We hypothesize that using machine learning approaches we could translate automatically and objectively the gait data from the dual-task assessments into clinically actionable knowledge about an individuals’ cognitive state. Our rationale is that developing a model that does not require cognitive testing and is solely based on gait assessments may lead to more effective cognitive screening and diagnostic tools that can be easily adapted into the clinical care setting [17].

The contribution of this paper is twofold. First, we extract existing and novel gait features from the single and dual-tasking gait data and determine the gait features that are important in developing a machine learning-based detection of healthy, MCI, and AD groups. Second, we develop a machine learning technique that associates these significant gait features from the single and dual-tasking gait to a clinical diagnosis: AD, MCI, or healthy. Our approach is novel because to our best knowledge, no research study has explored the advantage of machine learning techniques on dual-task gait assessment data to detect MCI and AD subjects. Machine learning has been shown to be successful in detecting MCI subjects using different types of subjects’ data such as MRI, diffusion tensor imaging, and electroencephalogram (EEG) (reviewed in [18]). However, these methods rely on expensive clinical protocols to collect data with extensive infrastructure and expensive medical equipment. Our technique can objectively detect subjects with AD or MCI from healthy subjects based on the gait data as the subjects perform a series of single and dual-task assessments. This will enable tools that can be performed by primary providers to detect MCI or AD subjects without using subjective cognitive assessments

2. Materials and Methods

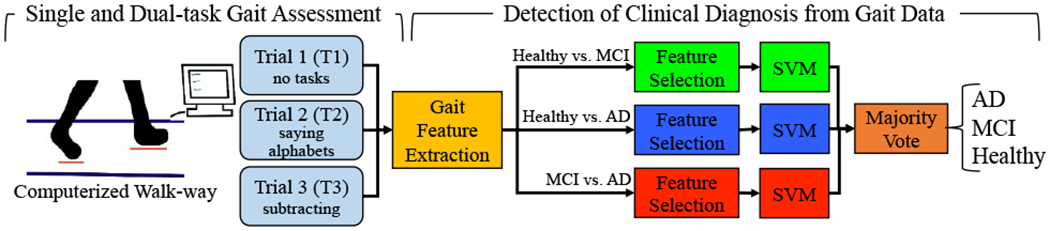

Figure 1 provides an illustrative description of our approach to detect cognitive status based on gait assessments.

Figure 1.

The overall approach for detection of AD, MCI, and healthy subjects from their single and dual-task gait assessment data.

2.1. Dataset

Data from a retrospective cohort of community-dwelling older adults participating in dementia research in an academic research setting were used in this study. The cohort consisted of 78 participants with 32 healthy, 26 MCI, and 20 AD. None of the participants had clinically detectable mobility impairments. Various gait characteristics were measured using a computerized walkway consisting of a pressure sensitive mat with a size of 20 ft. long x 4 ft. wide and a gait analysis software. For 35 subjects, a Zenomat system (ProtoKinetics LLC) was used and a GAITRite system (CIR Systems, PA) for the other 43 participants. Previous studies have shown that the two systems have minimal differences in providing the gait characteristics that were used in our study [19]. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Florida Atlantic University and was completed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

2.2. Procedures

Cognition:

Each subject was assessed with the MoCA test, which assesses performance on several cognitive domains including executive function, memory, orientation, attention, language, and visuospatial abilities, and is commonly used as a measure of global cognitive function. Total scores are derived by summing up individual cognitive domain scores and range from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating better performance. It takes approximately 10 to 12 minutes to complete.

Gait:

Subjects performed a series of single and dual-task assessments as their gait characteristics were measured and recorded using the computerized walkway. Participants were instructed to complete three trials of consecutive walking: single task normal speed walking (normal walking), dual-task normal speed walking while performing a verbal task (saying the alphabet out loud), and a second dual-task normal speed walking while performing a working memory dual-task (counting backward out loud from 100 by 3s). Table 1 provides the participants’ demographics.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics of the Healthy, MCI, and AD Groups

| Characteristic | All (n=78) | Healthy (n=32) | MCI (n=26) | AD (n=20) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 39 (50) | 23 (71.88) | 10 (38.46) | 6 (30) |

| Female | 39 (50) | 9 (28.12) | 16 (61.54) | 14 (70) |

| Age, years, mean±SD | 73.30±10.63 | 65.13±10.53 | 76.81±6.03 | 81.40±5.88 |

| MoCA score, mean±SD | 22.03±6.18 | 26.72±2.44 | 22.42±2.33 | 14.00±5.71 |

| Education, years, mean±SD | 15.07±2.50 | 16.67±1.15 | 15.17±2.56 | 14.00±2.83 |

2.3. Feature Extraction

We used the ProtoKinetics Movement Analysis Software (PKMAS) software to extract gait features from the Zenomat system and GAITRite software for the GAITRite system. For every trial, we extracted the mean, standard deviation (SD), and asymmetry for the following eight gait characteristics: stride time, step time, single support time, swing time, double support time, stance time, stride length, and step length. Asymmetry was calculated as the ratio of the left to right leg mean values. In addition, we calculated velocity (meters per second) and cadence (number of steps per minute) from the gait data of each trial. We also calculated the dual-task cost as the rate of change in each of the above metrics from trial 1 to trial 2 and 3 as well as trial 2 to 3 as (trial i-trial j)/trial i. This process resulted in a total of 108 gait features for every participant.

2.4. Feature Selection

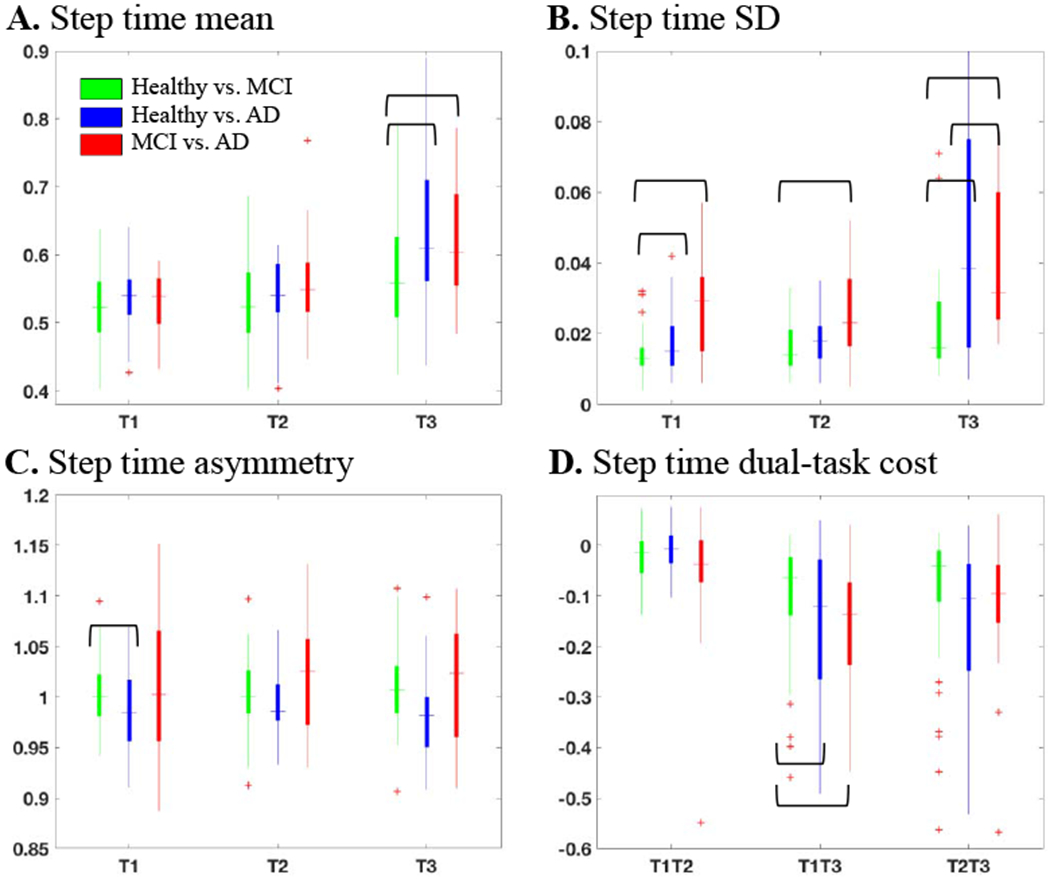

We selected a set of uncorrelated significant features for each of the three classification tasks of: healthy to MCI, healthy to AD, and MCI to AD in two steps. For every classification task, in step 1, we calculated the P-value using chi square (χ2) or t tests (as deemed appropriate) between the two comparison groups and identified the significant features as the ones with a P-value<0.05. Figure 2 shows the step 1 process for identification of the features with a P-valuc<0.05 as indicated by a bracket for the step time gait features.

Figure 2.

Feature distribution of step time (A) mean, (B) standard deviation, and (C) asymmetry at trials T1, T2, and T3 as well as (D) dual-task cost from trial T1 to T2 (T1T2), T1 to T3 (T1T3), and T2 to T3 (T2T3). The outliers are shown as an asterisks. The significant features were identified by brackets.

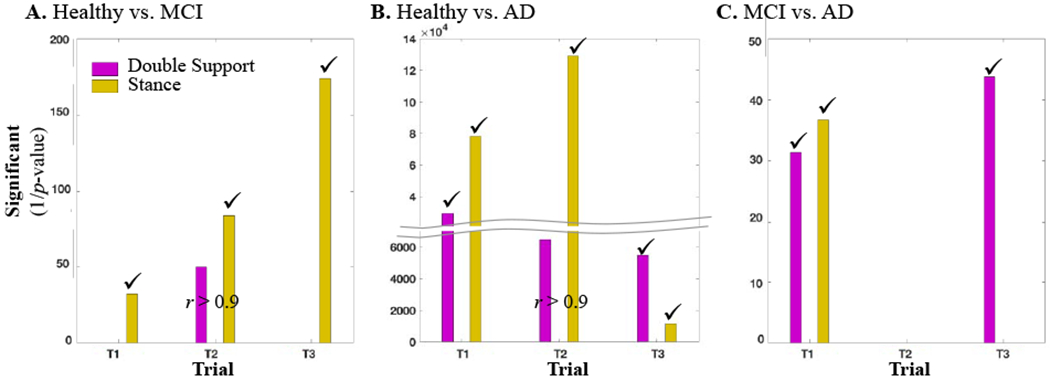

However, given that some of the extracted gait features such as double support and stance time or single support and swing time are correlated, in step 2, we identified the set of significant features with a correlation coefficient of greater than 90% and selected the significant feature with the lowest P-value, which were then used for training the classification model. Figure 3 illustrates the step 2 process for selection of the uncorrelated significant features. For visualization purposes, we are only showing the selection step between the double support and stance mean features in each trial for discrimination of the three classes; however, the concept applies to all the features. To better visualize the significance of each feature, we have shown one over the P-value as the significance value of each feature. Hence, a higher significance value indicates a lower P-value and a more significant feature.

Figure 3.

The significance value of the double support mean and stance mean at trials 1, 2, and 3 for discrimination of (A) healthy from MCI subjects, (B) healthy from AD subjects, and (C) MCI from AD subjects. The selected features are identified by a check mark. “r” stands for correlation coefficient.

2.5. Machine Learning with Gait Features

We used an SVM-based classification technique to detect healthy, MCI, and AD subjects based on their gait features. SVM is a powerful binary classification tool, which consists of a training and a testing stage. In the training stage, SVM uses sample data from both classes to generate a hyperplane in the data feature space, with each side of the hyperplane representing one of the classes. In the testing stage, SVM uses the generated hyperplane to classify new data points. When the data is not linearly separable, SVM uses a kernel function to map the feature vectors to a higher dimensionality space with a better separation. To avoid overfitting, a regularization parameter, C, is introduced as a tradeoff between misclassification and overfitting. The best hyperplane is chosen to maximize the distance between the nearest points of each class to the hyperplane and minimize any generalization errors when new data points are presented to the SVM. In this work, we used three SVMs in a one-vs-one manner. This design will enable the integration of the information learned about the significant features between two groups in developing the classification model. We trained one model for each of the following classification tasks: MCI vs. healthy, AD vs. healthy, and AD vs. MCI. For each classification task, we used the selected gait features for training the SVM classifier. In the testing stage, the three trained SVMs were applied to the gait features of a new subject, and the majority vote of the three SVMs was used to associate a diagnostic label (healthy, MCI, or AD). To account for cases where the three diagnoses are equally voted, we used the approach by Platt et al. [20] to assign a posterior class probability to each classification. Hence, when a subject was equally voted to healthy, MCI, and AD, we assigned the diagnosis with the highest probability as the diagnostic label.

Parameter Selection:

There are several hyperparameters to control the shape of the hyperplane classifier in an SVM: whether a linear separation is sufficient or a kernel is needed; regularization parameter (C); and any parameters that are associated with the kernel. In this work, we used the Gaussian radial basis function (RBF) with a gamma parameter (γ) to control the shape of the kernel. For every SVM, the hyperparameters (linear or an RBF kernel, C ∈ 2{−2,…,2}, and γ ∈ 2{−4,…,4} were selected based on a five-fold validation of the training data.

2.6. Machine Learning with MoCA Score

For comparison purposes, we developed a second SVM-based classifier to detect healthy, MCI, and AD subjects based on their MoCA cognitive assessment scores only. All the training and testing stages as well as the hyperparameters’ selection techniques described in section 2.5 were applied when using the MoCA score.

3. Results

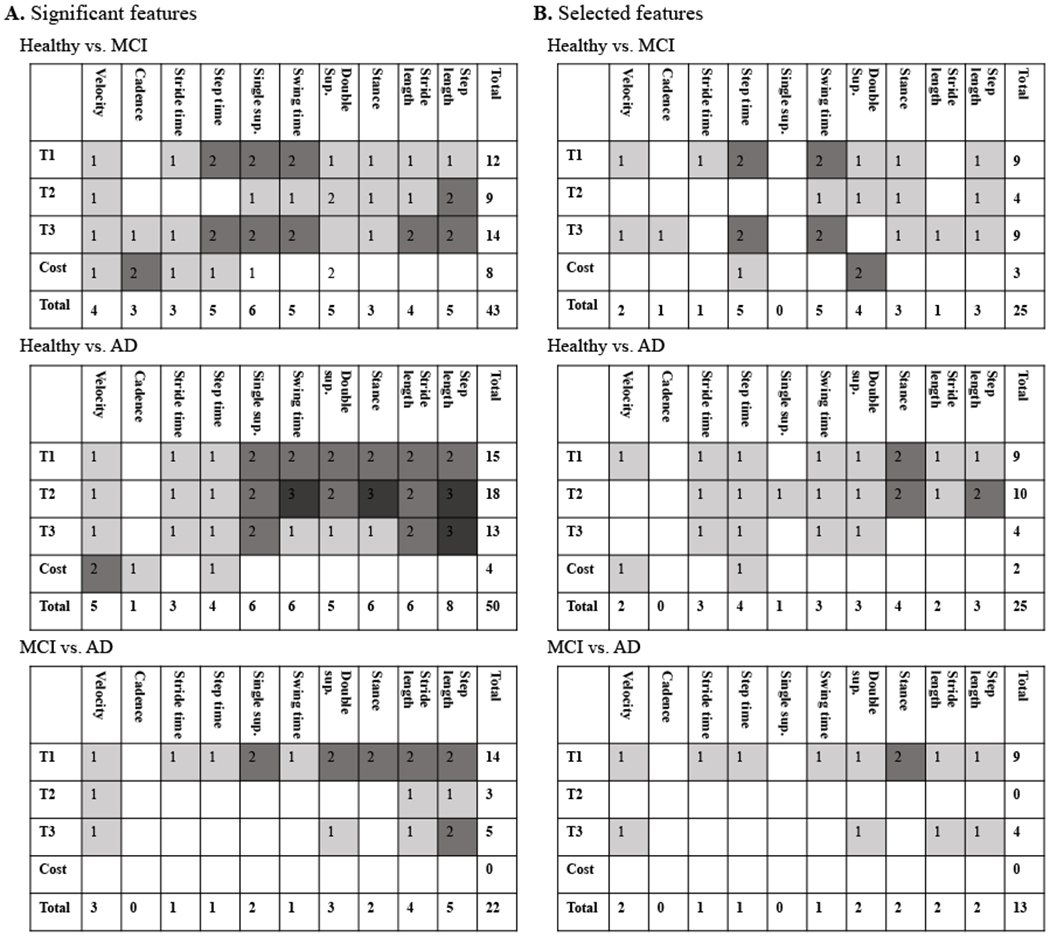

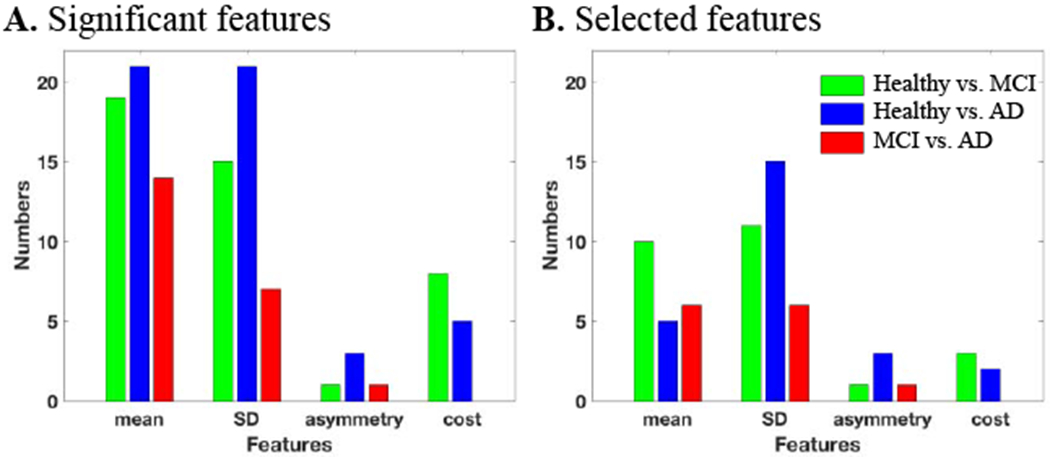

We applied the developed gait feature selection and classification on the single and dual-task gait assessment data explained in Section 2. Presented in Figure 2 are select results from step 1 of the feature identification process. As the figure indicates, the step time mean in trial 3 was larger for the MCI and AD subjects in comparison with the healthy subjects and significant for the discrimination of healthy from the MCI and AD subjects (Figure 2A). However, step time SD significantly increased from healthy to AD at all the three trials and to MCI at trial 1 and 3 (Figure 2B). The step time asymmetry was significant between the healthy and MCI subjects at trial 1 (Figure 2C). There was also a significant decline in the step time from trial 1 to trial 3 when healthy subjects were compared to the MCI and AD groups (Figure 2D). As a result, a total of 11 significant features were identified from the step time gait characteristics, where five of them discriminate healthy vs. MCI, five healthy vs. AD, and one for MCI vs. AD. Step 2 in the process of feature selection is presented in Figure 3, for a select pair of correlated features: double support and stance mean. As indicated in the figure, when separating the healthy from MCI group (Figure 3A), the stance mean-values of all the three trials and the double support mean of trial 2 were significant. However, the double support mean feature from trial 2 was not selected as it has a correlation coefficient of greater than 0.9 with the stance feature but its significance value is less than the stance feature. In a similar process, the double support mean of trial 2 from the healthy vs. AD discrimination was not selected either (Figure 3B). A summary of all the significant features and features selected for the three classification groups is presented in Figure 4. About 40-50% of the significant features had a high correlation with the other features and were not selected for developing the machine learning classifiers.

Figure 4 –

The distribution of the (A) significant features and (B) selected features per different gait features and at different trials. Cost refers to dual-task cost between the trials.

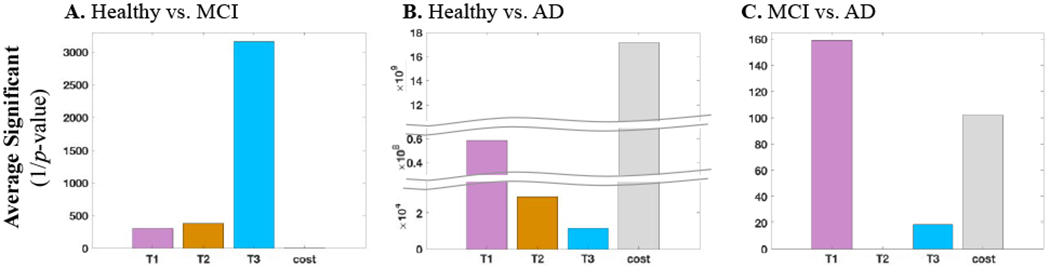

Further investigation as shown in Figure 5 indicated that the correlated features were mostly the mean values and were removed after considering the correlation. Figure 5 shows the distribution of the significant features (Figure 5A) and selected features (Figure 5B) per mean, SD, asymmetry, and dual-task cost. We found that in some cases (healthy vs. AD), over half of the significant features were correlated and not selected. Figure 6 provides the significance of the gait features extracted from every trial as well as the ones representing the dual-task cost. The vertical axes provide the average of the one over P-values of all the selected features in the same category. We found that trial 3 provided the most significant features for differentiating MCI from healthy subjects (Figure 6A), dual-task cost provided the most significant features for differentiating AD from healthy subjects (Figure 6B), while trial 1 was significant in separating AD from MCI subjects (Figure 6C).

Figure 5.

The distribution of the (A) significant features and (B) selected features per feature type of mean, SD, asymmetry, and dual-task cost from one trial to another.

Figure 6.

The average significance value of the selected gait features from each trial as well as the dual-task cost in differentiating between (A) healthy from MCI, (B) healthy from AD, and (C) MCI from AD.

Next, we trained three SVMs based on the selected gait features from 80% of the subjects in each of the healthy, MCI, and AD groups, and tested them on the remaining 20% subjects. For implementation, we used LIBSM toolbox in MATLAB [21]. Repeating this process five times, every time with a different set of training and testing subsets, resulted in an average classification accuracy of 78% and F1-score of 77%. The average classification accuracy and F1-score when using the MoCA scores only were 83% and 84%, respectively. The SVM selected the MoCA cut off of <26 for classifying MCI from healthy, <19 for AD from MCI, and <22 for AD from healthy. Table 2 provides the classification distribution using the MoCA score. For comparison purposes, we repeated the experiment using all the gait features instead of the selected significant features. This experiment resulted in a much lower average accuracy of 69% indicating the importance of one-vs-one classification design used in our approach. In addition to the three classification accuracy results, we combined the MCI and AD as one group and in Table 2 reported the classification results for healthy vs. MCI/AD subjects when using only the gait features and only the MoCA scores.

Table 2.

Classification accuracy of the Healthy, MCI, and AD Groups

| A. Classification based on only gait assessment data | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | Healthy | MCI | AD |

| Healthy | 85 | 13 | 2 |

| MCI | 10 | 70 | 20 |

| AD | 5 | 20 | 75 |

| Diagnosis | Healthy | MCI/AD | |

| Healthy | 85 | 15 | |

| MCI/AD | 13 | 87 | |

| B. Classification based on MoCA scores | |||

| Diagnosis | Healthy | MCI | AD |

| Healthy | 85 | 15 | 0 |

| MCI | 16 | 84 | 0 |

| AD | 0 | 20 | 80 |

| Diagnosis | Healthy | MCI/AD | |

| Healthy | 85 | 15 | |

| MCI/AD | 9 | 91 | |

4. Discussion

Early detection of persons with MCI and AD remains a great challenge, both in primary care and specialty practices. We developed an approach based on dual-tasking gait assessments and machine learning that can detect MCI and AD and discriminate them from healthy subjects. As hypothesized, we were able to use dual-tasking gait assessment data and a machine learning approach and developed the first automated and objective algorithm to detect healthy vs. MCI vs. AD subjects based on only their gait data. Our approach resulted in a plausible average classification accuracy of 78% using only gait assessments (Table 2). We performed a comprehensive investigation of the gait characteristics with respect to the disease stage at MCI and AD and made several interesting observations.

Change in single- and dual-task gait:

Our investigations showed that most of the gait features from single and dual-task gait were significant in discriminating between healthy vs. MCI, healthy vs. AD, and MCI vs. AD subjects. As shown in Figure 4A, more significant changes were associated when comparing the healthy gait to the AD gait (with 50 features) in comparison to the healthy to MCI gait (43 features) and MCI to AD gait (22 features). Velocity was previously reported to have a significant decline in all the three classifications (healthy to MCI or AD [22] and MCI to AD [23]), and we observed a similar behavior (Figure 4A). However, more complex cognitive tasks seem to be required to elicit the gait speed differences between healthy from cognitively declined subjects. The dual-task cost in velocity from trial 1 to trial 2 was not significant in differentiating healthy from MCI or AD, while it was significant from trial 1 to 3. Also, we did not find any significant decline in the velocity from single to dual tasking between the MCI and AD subjects although the velocity was consistency lower for the AD subjects.

Important gait features:

An interesting observation after removing the correlated features is that about 50% of the significant features were correlated, resulting in 25 uncorrelated significant features for healthy vs. MCI and healthy vs. AD and only 13 for MCI vs. AD (Figure 4B). This was expected as some of the extracted features (e.g., stance and double support time, swing and single support time) quantify a similar gait characteristic. Step time, swing time, double support, stance, and step length were the gait characteristics with the most number of features for healthy vs. MCI or AD plus stride time for healthy vs. AD classification. The gait features with the most number of features were velocity, double support, stance, stride length, and step length for MCI vs. AD.

Gait variability:

Gait variability was the most significant feature in detecting cognitive decline (Figure 5). In case of healthy vs. AD, 60% (15 out of 25) of the selected features were from the gait standard deviation, 46% (6 out of 13) for MCI vs. AD and 44% (11 out of 25) for healthy vs. MCI. Beauchet et al. [24] have also shown gait variability increases significantly for cognitively declined subjects, and the work by Sheridan et al. [25] has shown that the effect of cognitive decline on gait variability is larger than the gait mean performance.

Gait asymmetry:

In some studies, gait asymmetry properties have suggested to be useful only in detecting gait pathology with a unilateral onset [26] and have been used in detecting different dementia subtypes [27]. However, our study agrees with the work by Maquet et al. [28], which suggested that healthy subjects have a significantly better symmetry than MCI and AD subjects. In our cohort, we found that the gait asymmetry increases with cognitive decline (Figure 5). Step length asymmetry significantly increased from healthy to MCI and MCI to AD. Stance and swing asymmetry were also significantly higher in AD compared to MCI.

Change in gait performance with disease progression:

Our further investigation shows that there is a more significant decline in the single and dual-task performance as the disease progresses. As shown in Figure 6, the significance value of the healthy vs. AD gait features in all the three trials was higher than the healthy vs. MCI, suggesting that gait impairment as measured by dual-tasking may increase as individuals transition from MCI to AD. In addition, the performance decline of the MCI subjects becomes more evident with the increase of the cognitive load in trial 2 and then trial 3 (Figure 6A), but as the disease advances to AD, the decline becomes more evident even in trial 1 without adding a cognitive load (Figure 6B–C). Moreover, the dual-task cost from trail 1 to trial 2 and to trial 3 increases more for AD subjects than the MCI subjects (Figure 6C). A similar behavior was reported by Montero-Odasso et al. [15], where the authors reported that a significant gait change is associated with AD.

Comparisons with the state-of-the-art:

A few examples of the machine learning applications related to gait characterization and cognitive decline include age-sensitive classification of single vs. dual-task gait [29], estimation of the Mini-Mental State Examination cognitive score from gait [30], and detection of healthy from AD [31]. To the authors’ knowledge, the only machine learning approach directly related to our approach is the work by Costa et al. [31], where healthy subjects were distinguished from AD subjects with an average classification accuracy of 78.9% based on their postural kinematics. We compared our approach to a classification based on cognitive assessment scores. The machine learning algorithm picked a cutoff of 26 for detecting MCI from healthy, which is comparable to the reported 25-26 for screening MCI subjects [32] [33]. The algorithm selected a cut off of 19 for detecting AD from MCI subjects; however, there is no set cutoff in the literature to compare to. The classifier based on MoCA resulted in 83% accuracy. As expected from the fewer selected features (Figure 4), the discrimination of MCI from AD is more challenging using only the gait features. The average classification accuracy of healthy vs. MCI or AD subjects was increased to 86% with an F1-score of 88% when using only the gait features, which is comparable to 88% average accuracy and 90% F1-score with MoCA (Table 2).

5. Conclusion

The aim of this study was to develop an automated and objective method for detecting MCI, and AD subjects and discriminating them from healthy controls. For this purpose, we collected gait data from a total of 78 elderly subjects as they performed a series of single and dual-task walking. We extracted a total of 108 gait features from each subject and identified the uncorrelated significant features. Next, we used a machine learning approach to detect the clinical diagnosis from the selected gait features. The approach resulted in 25 uncorrelated significant gait features for discriminating healthy vs. MCI and healthy vs. AD, and 13 for MCI vs. AD. The five-fold classification accuracy was 78% using the selected gait features, which was slightly lower than 83% when using the cognitive assessment score. This work is the first work towards the selection of important gait features for a machine learning-based classification and developing an automated and objective technique for detection of cognitive decline in MCI and AD subjects based on only gait assessments. Gait-based cognitive screening has practical value as gait assessments are more commonly done, compared with cognitive assessments, in primary care settings where the majority of patients are seen. Using gait as a screen for cognitive impairment can prompt clinicians to conduct further evaluations for diagnosing MCI and AD.

Highlights.

Detection of mild cognitive decline (MCI) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) from dual-task gait

First application of machine learning on dual-task assessment data for MCI and AD

Accuracy of 78% with 77% F1-score for detecting healthy, MCI, and AD using only gait

Accuracy of 86% with 88% F1-score for detecting MCI or AD from healthy using only gait

Provided several interesting insights about gait changes from healthy to MCI to AD

Funding

This work was supported by Ed and Ethel Moore Alzheimer’s Disease Research Program at Florida Department of Health (#AWD-001693) and National Science Foundation (#1942669) to Dr. B. Ghoraani and National Institute on Aging (R01 AG040211), the Harry T. Mangurian Foundation, and Leo and Anne Albert Charitable Trust to Dr. J.E. Galvin.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- [1].Xu JQ, Murphy SL, Kochanek KD and Arias E, “Mortality in the United States, 2018,” National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief, Number 355,, January 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Alzheimer’s Association, “2018 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures,” vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 367–429, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Knopman D, Gottesman R, Sharrett A, Wrack L, Windham B, Coker L, Schneider A, Hengrai S, Alonso A, Coresh J and Albert M, “Mild cognitive impairment and dementia prevalence: the atherosclerosis risk in communities neurocognitive study,” Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment & Disease Monitoring, vol. 2, pp. 1–11, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Akushevich I, Yashkin A, Kravchenko J, Ukraintseva S, Stallard E and Yashin A, “Time trends in the prevalence of neurocognitive disorders and cognitive impairment in the United States: the effects of disease severity and improved ascertainment,” Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, vol. 64, no. 1, pp.137–148, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Borson S, Frank L, Bayley P, Boustani M, Dean M, Lin P, McCarten J, Morris J, Salmon D, Schmitt F and Stefanacci R, “Improving dementia care: the role of screening and detection of cognitive impairment,” Alzheimer’s & Dementia, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 151–159, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Dubois B, Padovani A, Scheltens P, Rossi A and Dell’Agnello G, “Timely diagnosis for Alzheimer’s disease: a literature review on benefits and challenges,” Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, vol. 49, no. 3, pp. 617–631,2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Nasreddine Z, Phillips N, Bédirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, Cummings J and Chertkow H, “The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment,” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, vol. 53, no. 4, pp. 695–699, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hoops S, Nazem S, Siderowf A, Duda J, Xie S, Stem M and Weintraub D, “Validity of the MoCA and MMSE in the detection of MCI and dementia in Parkinson disease,” Neurology, vol. 73, no. 21, pp. 1738–1745,2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Prince M, Comas-Herrera A, Knapp M, Guerchet M and Karagiannidou M, “World Alzheimer report 2016: improving healthcare for people living with dementia: coverage, quality and costs now and in the future,” Alzheimer’s Disease International (ADI), 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Alzheimer’s Association, “Alzheimer Association 2019 Facts and Figures,” Alzheimers Dement, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 321–387, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Morris R, Ford S, Bunce J, Bum D and Rochester F, “Gait and cognition: mapping the global and discrete relationships in ageing and neurodegenerative disease,” Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, vol. 64, pp. 326–345, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Buckley C, Alcock F, McArdle R, Rehman R, Del Din S, Mazzà C, Yamall A and Rochester F, “The role of movement analysis in diagnosing and monitoring neurodegenerative conditions: insights from gait and postural control,” Brain sciences, vol. 9, no. 2, p. 34, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kourtis F, Regele O, Wright J and Jones G, “Digital biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease: the mobile/wearable devices opportunity,” NPJ digital medicine, vol. 2, no. 1, p. 9, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lyons B, Austin D, Seelye A, Petersen J, Yeargers J, Riley T, Sharma N, Mattek N, Wild K, Dodge H and Kaye J, “Pervasive computing technologies to continuously assess Alzheimer’s disease progression and intervention efficacy,” Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, vol. 7, p. 102, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Montero-Odasso M, Sarquis-Adamson Y, Speechley M, Borne M, Hachinski V, Wells J, Riccio P, Schapira M, Sejdic E, Camicioli R and Bartha R, “Association of dual-task gait with incident dementia in mild cognitive impairment: results from the gait and brain study,” JAMA neurology,, vol. 74, no. 7, pp. 857–865,2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ceïde M, Ayers E, Fipton R and Verghese J, “Walking while talking and risk of incident dementia,” The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, vol. 26, no. 5, pp. 580–588, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Belghali M, Chastan F, Cignetti F, Davenne D and Decker L, “Loss of gait control assessed by cognitive-motor dual-tasks: pros and cons in detecting people at risk of developing Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases,” Geroscience, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 305–329, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Alberdi A, Aztiria A and Basarab A, “On the early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease from multimodal signals: A survey,” Artificial intelligence in medicine, vol. 71, pp. 1–29, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Egerton T, Thingstad P and Helbostad J, “Comparison of programs for determining temporal-spatial gait variables from instrumented walkway data: PKmas versus GAITRite,” BMC research notes, vol. 7, no. 1, p.542, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Platt JC, “Probabilistic outputs for support vector machines and comparisons to regularized likelihood methods,” in Advances in Large Margin Classifiers, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Chang C-C and Lin C-J, “LIBSVM : a library for support vector machines,” ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology, vol. 1, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Montero-Odasso M, Bergman H, Phillips N, Wong C, Sourial N and Chertkow H, “Dual-tasking and gait in people with mild cognitive impairment. The effect of working memory.,” BMC geriatrics,, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 1–8, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].König A, Klaming L, Pijl M, Demeurraux A, David R and Robert P, “Objective measurement of gait parameters in healthy and cognitively impaired elderly using the dual-task paradigm,” Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, vol. 29, no. 6, pp. 1181–1189, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Beauchet O, Launay C, Sekhon H, Barthelemy J, Roche F, Chabot J, Levinoff E and Allah G, “Association of increased gait variability while dual tasking and cognitive decline: results from a prospective longitudinal cohort pilot study.,” Geroscience, vol. 39, no. 4, pp. 439–445, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Sheridan P, Solomont J, Kowall N and Hausdorff J, “Influence of executive function on locomotor function: divided attention increases gait variability in Alzheimer’s disease,” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, vol. 51, no. 11, pp. 1633–1637, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Lord S, Galna B, Verghese J, Coleman S, Bum D and Rochester L, “Independent domains of gait in older adults and associated motor and nonmotor attributes: validation of a factor analysis approach,” Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biomedical Sciences and Medical Sciences, vol. 68, no. 7, pp. 820–827, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Me Ardle R, Del Din S, Galna B, Thomas A and Rochester L, “Differentiating dementia disease subtypes with gait analysis: feasibility of wearable sensors?.,” Gait & Posture, vol. 76, pp. 372–376, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Maquet D, Lekeu F, Warzee E, Gillain S, Wojtasik V, Salmon E, Petermans J and Croisier J, “Gait analysis in elderly adult patients with mild cognitive impairment and patients with mild Alzheimer’s disease: simple versus dual task: a preliminary report,” Clinical physiology and functional imaging, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 51–56, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Costilla-Reyes O, Scully P and Ozanyan K, “Age-sensitive differences in single and dual walking tasks from footprint floor sensor data,” IEEE SENSORS , pp. 1–3, 2017.29780437 [Google Scholar]

- [30].Matsuura T, Sakashita K, Grushnikov A, Okura F, Mitsugami I and Yagi Y, “Statistical Analysis of Dual-task Gait characteristics for cognitive Score estimation,” Scientific Reports, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 1–12, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Costa L, Gago M, Yelshyna D, Ferreira J, David Silva H, Rocha L, Sousa N and Bicho E, “Application of machine learning in postural control kinematics for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease,” Computational intelligence and neuroscience, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].O’Caoimh R, Timmons S and Molloy D, “Screening for mild cognitive impairment: comparison of “MCI specific” screening instruments,” Journal of Alzheimer’s disease, vol. 51, no. 2, pp. 619–629., 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Nasreddine Z, Rossetti H, Phillips N, Chertkow H, Lacritz L, Cullum M and Weiner M, “Normative data for the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) in a population-based sample,” Neurology, vol. 78, no. 10, pp. 765–766, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]