Abstract

Polymeric nanocarriers have been extensively used to improve the delivery of hydrophobic drugs, but often provide low encapsulation efficiency and percent loading for hydrophilic compounds. In particular, insufficient loading of hydrophilic antiretroviral drugs such as the integrase inhibitor raltegravir (RAL) has limited the development of sustained-release therapeutics or prevention strategies against HIV. To address this, we developed a generalizable prodrug strategy using RAL as a model where loading, release and subsequent hydrolysis can be tuned by promoiety selection. Prodrugs with large partition coefficients increased the encapsulation efficiency up to 25-fold relative to RAL, leading to significant dose reductions in antiviral activity assays. The differential hydrolysis rates of these prodrugs led to distinct patterns of RAL availability and observed antiviral activity. We also developed a method to monitor the temporal distribution of both prodrug and RAL in cells treated with free prodrug or prodrug-NPs. Results of these studies indicated that prodrug-NPs create an intracellular drug reservoir capable of sustained intracellular drug release. Overall, our results suggest that the design of prodrugs for specific polymeric nanocarrier systems could provide a more generalized strategy to formulate physicochemically diverse hydrophilic drugs with a number of biomedical applications.

Keywords: PLGA, nanoparticle, drug-delivery, encapsulation, prodrug, raltegravir, antiretroviral, intracellular concentration, liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry

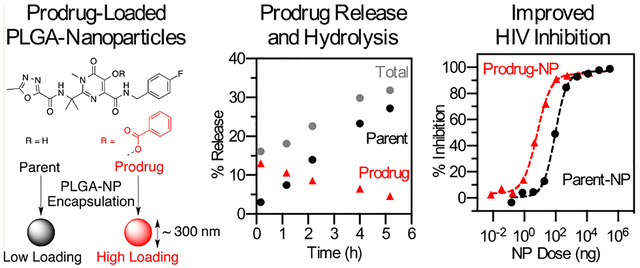

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Biodegradable polyester nanoparticles are attractive drug delivery vehicles because they combine biocompatibility with the improved drug bioavailability, half-life, and toxicity profile of nanocarriers.1–3 Poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) polymers are the most extensively investigated for controlled release technologies, partly due to the ease of altering their molecular weight and monomer composition to tune drug release rates over several days to months.4 Recognized also for their biocompatibility and complete biodegradation into natural and nontoxic metabolites, these FDA approved polymers are currently used clinically for oral, intramuscular, and subcutaneous delivery.5 Sustained release PLGA nanoparticle formulations have primarily been used for hydrophobic drugs or some large biomacromolecules because conventional preparation methods are unable to prevent the rapid and preferential partitioning of water-soluble small molecule drugs into the aqueous phase that excludes the polymer. This leads to low loading and entrapment efficiency of hydrophilic drugs formulated in PLGA nanoparticles. An additional persisting challenge in the development of sustained release PLGA nanoparticle systems is incomplete information regarding the kinetics of intracellular drug release and trafficking. This information is needed to inform rational nanoparticle design to interpret nanoparticle-encapsulated drug activity.

Approaches to formulate water-soluble drugs into PLGA nanoparticles include double-emulsion solvent-evaporation (DES-E) or -diffusion (DES-D) and nanopreciptation.6 These approaches all drive entrapment by bringing the polymer above its solubility limit to precipitate around the drug. To achieve high drug loading, the kinetics of the precipitation process must be faster than the kinetics of drug diffusion to the external aqueous phase. In nanodispersions, diffusion is typically faster than polymer precipitation due to the large surface area and short diffusion path length, which is why microparticles achieve comparably higher drug loading.7 Although several studies have investigated various formulation parameters to increase hydrophilic drug loading into PLGA nanoparticles by DES and nanoprecipitation, they have resulted in only modest improvements of less than 2-fold when these methods are directly compared.8 Moreover, drug loading and encapsulation efficiency can vary widely based on the specific aqueous solubility and ionization state of the drug used.9 Therefore, a more generalized strategy to formulate physicochemically diverse hydrophilic drugs into PLGA nanoparticles would be of significant value for a number of biomedical uses.

Rational design of prodrugs is an emerging strategy to expand nanocarrier drug delivery attributes to a broader range of active pharmaceuticals, including water-soluble compounds. For conventional prodrugs, a labile promoiety is used to modify the bioactive parent compound to improve bioavailability and half-life by transiently tuning aqueous solubility, partition coefficient, and stability during transport through its route of administration.10 In contrast, prodrugs intended for integration with a nanocarrier platform are designed to undergo either polymerization, self-assembly, or encapsulation.11 Prodrugs used for polymerization or self-assembly typically require covalent modification of the drug to a major compositional or structural component of the nanocarrier such as a polymer or an accessory macromolecule. Alternatively, prodrugs may be designed to promote noncovalent association with the polymer phase during nanocarrier formulation, leading to improved encapsulation during polymer precipitation. In this strategy, prodrugs are selected based on advantageous formulation or release properties, rather than for any direct impact on toxicity or pharmacokinetics following release from the nanoparticles. Prodrugs designed for encapsulation are a more generalizable technique amenable to diverse nanocarrier platforms since they are not limited to specific biomaterials and conjugation chemistries. The selection of appropriate promoieties could likely tune the properties of water-soluble drugs to improve their encapsulation and loading in PLGA nanoparticles, but this strategy has not been thoroughly investigated.

PLGA nanoparticles have been investigated for antiretroviral (ARV) drug delivery for HIV but the most successful examples are limited to compounds with reported aqueous solubility of <0.01 g L−1 such as dapivirine, ritonavir, liponavir, and efavirenz.12–16 In the studies where water-soluble and ionizable ARV drugs have been attempted, the measured drug loadings have been ~1 wt %, which is impractical for many biomedical applications.17,18 In our previous work aimed at testing ARV drug combinations, we observed low drug loading for raltegravir, an ionizable integrase inhibitor.17 Raltegravir (RAL) is effective in combination therapies although when used alone it has intrinsically low antiviral potency.19 Low loading of RAL in our previous PLGA nanoparticles precluded us from accessing relevant concentration ranges in our drug combination experiments. Here we show that ester and acetal carbonate derivatives of RAL designed to prevent ionization during PLGA nanoparticle synthesis improve encapsulation efficiencies, and that the selection of an appropriate promoiety produces high drug loading and rapid conversion to the parent drug during release. These derivatives function as prodrugs in antiviral activity assays and yield distinct patterns of activity based on differential rates of release and hydrolysis, leading to significant dose reductions relative to the parent formulation in some cases. To better understand the potential of these prodrug-NP for long acting antiviral activity the intracellular drug content, drug release, and prodrug hydrolysis were monitored using liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry.

Overcoming drug loading limitations and understanding the intracellular release behavior of polymeric nanocarriers for hydrophilic ARV drugs will likely be required to develop sustained-release therapeutics and topical prevention strategies against HIV. The prodrug strategy presented here may provide a generalizable strategy to incorporate hydrophilic drugs into PLGA nanoparticles and to tune and monitor intracellular drug bioavailability based on the kinetics of prodrug release and hydrolysis.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Synthesis.

Detailed synthetic procedures and characterization data for analogs 1–7 are provided in Supporting Information. Briefly, raltegravir (RAL) was isolated as a neutral compound from ISENTRESS tablets (400 mg per tablet, Merck & Co.) via extraction followed by recrystallization from isopropanol. Analogs 1–5 were prepared in one step from RAL with the appropriate acyl chloride by the method of Wang et al.20 Analogs 6–7 were prepared in one step from RAL with the appropriate alkyl chloride following the general scheme of Walji et al.21 All analogs were purified by silica column chromatography and characterized by NMR (1H, 13C, 19F) and mass spectrometry (electrospray ionization in positive ion mode). HPLC chromatographs of purified analogs confirmed the presence of a single species with retention times consistent with that of the analog structure (see below).

Reverse-Phase HPLC.

Reverse-phase HPLC analysis was conducted on an Agilent 1100 series instrument using a Phenomenex Luna 5.0 μm C-18 column (250 × 4.6 mm) operating at 35 °C with UV detection at 300 nm. The mobile phase consisted of isocratic mixtures of ACN and 25 mM KH2PO4 (pH 4.8). The following retention times were observed for analogs using the indicated constant composition ACN:buffer eluent ratios; RAL (40:60, 10.4 min; 55:45, 4.8 min; 65:35, 3.8 min), 1 (40:60, 8.7 min), 2 (55:45, 8.0 min), 3 (65:35, 9.4 min), 4 (55:45, 7.2 min), 5 (55:45, 12.3 min), 6 (55:45, 6.7 min), and 7 (55:45, 6.1 min). For HPLC quantitation reference solutions of 1–7 and RAL were prepared in DMSO by dilution. Standard curves were determined from a minimum of eight concentration points in the range of 0.005 to 1.000 mg/mL and produced linear relationships with R2 values >0.99.

pKa Determination.

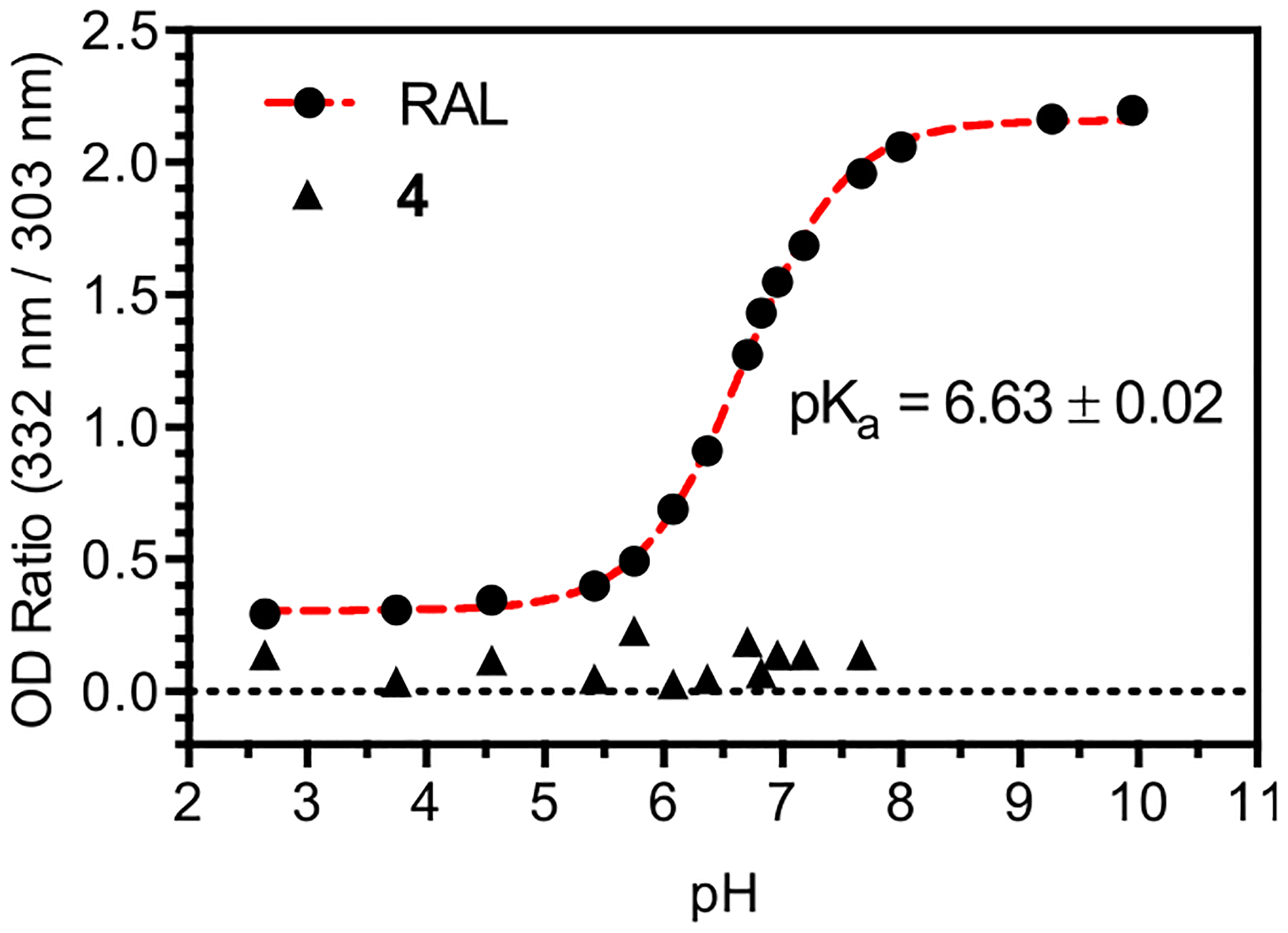

The pKa of RAL was determined by UV–vis titration, monitoring the absorbance at the maximal wavelength of the neutral and ionized form (303 and 332 nm respectively). For each measurement a solution of RAL (1.0 mg/mL in DMSO) was diluted 100-fold into 100 mM buffer (citrate, pH 2.9 to 5.9; phosphate, pH 6.6 to 8.0; glycine pH 9.3 to 10.0). A plot of absorbance ratio (332 nm/303 nm) versus pH was fit to a single ionization model, providing an average pKa value of 6.6 for three triplicate measurements, a value consistent with previous measurements.22 Titrations carried out with analog 4 showed no change in absorbance at pH values below 8.0, and spectra consistent with partial hydrolysis to RAL in glycine buffers above pH 9.0.

Partition Coefficients.

Partition coefficients were measured using 1-octanol as the organic phase and phosphate buffer saline (pH 7.4) as the aqueous phase at 20 °C. For each analog Pow was measured in triplicate using three different ratios of organic to aqueous volumes, following the shake flask method of the OECD.23 The concentration of dissolved analogs was kept below 2.0 mM in both phases and was determined by HPLC following centrifugation using the appropriate standard curve (see above). The same procedure was used for RAL but the value obtained represents a distribution coefficient because RAL is partially ionized at this pH.

Rates of Hydrolysis.

Rates of analog hydrolysis were measured by HPLC analysis at fixed time points following incubation at 20 °C. Analog stocks (10.0 mg/mL in DMSO) were diluted 100-fold into cell culture medium (see composition below) and vortexed. Reactions were sampled at 15 min intervals up to 2 h, then at intervals of longer duration dependent on reaction half-life (sampling times were defined as the time between initial mixing and injection on the HPLC column). The extent of reaction was quantitated by HPLC by converting the area under the curve for both the analog and RAL to nmol using the appropriate standard curve. Percent conversion was calculated as 100[nmol RAL /(nmol analog + nmol RAL)] at each time point and the half-life was estimated by fitting percent conversion curves to a pseudo first-order hydrolysis model.

Fabrication of ARV-Loaded Nanoparticles.

Antiretroviral loaded nanoparticles (ARV-NP) were fabricated using a single emulsion/solvent evaporation method and a nanoprecipitation method.

Single Emulsion/Solvent Evaporation Method.

The “oil”-phase of the emulsion contained 5% w/v PLGA dissolved in dichloromethane and 10 wt % ARV drug (weight of ARV relative to weight of PLGA polymer). This mixture was added dropwise into an aqueous solution containing 5% w/v aqueous poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) while vortexing. The solution was emulsified using a probe sonicator (500W, Ultrasonic Processor GEX 500) with a 3 mm diameter microtip probe for four intervals of 10 s at 38% amplitude with vortexing between each interval. The sonicated emulsion was transferred to a continuously stirred aqueous solution of PVA (0.3% w/v) and all residual dichloromethane was removed by rotary evaporation within 30 min.

Nanoprecipitation Method.

ARV drug (10 wt % relative to PLGA) was codissolved with PLGA (20 mg/mL) in acetone. This organic phase was then added by syringe pump (flow rate 7 mL/min) to a continuously stirred aqueous solution of PVA (0.3% w/v). Immediately after organic phase addition, residual acetone was removed by rotary evaporation.

Nanoparticles formulated by both methods were washed with Milli-Q water three times by centrifugation at 14 000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C to remove residual surfactant and unencapsulated drug. Following these wash steps the nanoparticles were suspended in water, frozen at −80 °C and lyophilized (24 h, 0.133 mbar at −87 °C). Nanoparticles formulated by nanoprecipitation were suspended in water with 20 wt % sucrose as a lyoprotectant. Lyophilized nanoparticles were stored at −80 °C until use.

Characterization of ARV-Loaded Nanoparticles.

ARV-NP size, polydispersity (PDI) and zeta (ζ)-potential were measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS) in Milli-Q water (size, PDI) or 10 mM NaCl (pH 7) (zeta-potential) using a Zetasizer Nano ZS90 (Malvern Instruments). ARV loading was measured by dissolving a known mass of lyophilized ARV-NP in DMSO and quantitating ARV content by HPLC. Percent loading is defined as the ratio of the measured ARV content to the mass of PLGA-NP, and encapsulation efficiency is defined as the ratio of the observed loading to the theoretical loading (assuming no loss of ARV during the fabrication process).

Release Kinetics of ARV-Loaded Nanoparticles.

Release kinetics from ARV-NP were measured in cell culture medium at 37 °C. Nanoparticles were maintained in sink conditions throughout release studies (10-fold more dilute than the solubility of the compound of interest following complete release). For rapidly hydrolyzing analogs, sink conditions were calculated based on 100% hydrolysis to RAL. Release trials were initiated by resuspending ARV-NP in cell culture media and dividing aliquots into individual microcentrifuge tubes. For each time point, one aliquot was pelleted by centrifugation at 14 000 g for 5 min, the supernatant was carefully removed, and the pellet was air-dried. The concentration of both the analog and the RAL produced through hydrolysis was determined in the supernatant immediately after centrifugation by HPLC analysis. The pellet from each time point was then dissolved in DMSO and the unreleased analog was quantitated by HPLC (RAL originating from analog hydrolysis was not observed in the pellet for any analogs). Release curves were normalized to 100% based on the ARV concentration in the supernatant at the first time point where no analog was detected in the pellet.

Subcellular Fractionation and Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry.

For 1, 24, and 48 h time points, TZM-bL cells were incubated with 4 either as free drug or encapsulated in nanoparticles at 1 μM drug concentrations. Cells were plated in separate wells of a 24 well plate for each time point at seeding densities that would yield 500,000 cells for analysis. At each time point, cells were detached and washed with ice cold PBS to remove extracellular nanoparticles. Cells were then lysed and cytoplasm, membrane, soluble nuclear, chromatin-bound nuclear, and cytoskeletal cell fractions were isolated using the Thermo Scientific Subcellular Fractionation Kit for Cultured Cells according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For 3 day, 5 day, and 7 day time points, cells (50 000 cells/well) were incubated with 4 as free drug or encapsulated in nanoparticles at 5 μM drug concentrations in a 24 well plate. On day 3 cells were detached with trypsin, washed with PBS, resuspended in media and replated. This step was intended to remove any nanoparticles or free drug not internalized intracellularly at the time of the wash and also prevented the cells from becoming overconfluent. At each time point, cells were detached with trypsin, washed with PBS, counted using a hemocytometer, and lysed with ice-cold 50:50 acetonitrile: methanol. All samples were spiked with 50 pg of RAL-d6 as an internal standard prior to analysis by LC-MS/MS at the University of Washington Mass Spectrometry Center. Liquid chromatography was performed using a gradient method of 10 mM formic acid in Milli-Q water and 10 mM formic acid in 50:50 ACN:MeOH. Two uL of each sample was injected into the system at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min. Mass spectrometry was performed in electrospray positive mode with a cone voltage of 40 kV. Drugs were detected at the following m/z transitions: 445.35 to 109.10 (RAL), 549.07 to 105.05 (analog 4), and 451.35 to 115.10 (RAL-d6). Data were analyzed based on peak adjusted ratios relative to the internal standard to control for matrix effects and normalized to the number of cells lysed.

Cell Lines and Viruses.

TZM-bL (JC53-BL) cell lines and HIV-1 BaL virus were obtained from the NIH AIDS Research & Reference Reagent Program. TZM-bL cells are a genetically engineered HeLa cell clone that expresses CD4, CXCR4, and CCR5 and contains Tat-responsive reporter genes for firefly luciferase (Luc) and Escherichia coli β-galactosidase under regulatory control of an HIV-1 long terminal repeat, which permits sensitive and accurate measurements of HIV infection. TZM-bL cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 mg/mL streptomycin and 2 mM l-glutamine and 25 mM HEPES. The same cell culture medium was used for analog hydrolysis and ARV-NP release studies. Cells were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 air environment.

Antiviral Activity Assay.

Antiviral activity was measured as a reduction in luciferase reporter gene expression after infection of TZM-bL cells with HIV-1 BaL. All ARV drugs and ARV-NPs were dosed based on molar concentrations of the drug, using the measured percent loading of ARV-NPs to convert between NP dose and ARV concentration. Briefly, TZM-bL cells were seeded at a concentration of 1 × 104 per well in 96-well microplates (~30 000 cells/cm2). After 24h culture, TZM-bL cells were incubated with various concentrations of either free drugs or NP-formulated drugs at 37 °C for 1h prior to virus exposure. After treatment, cell free HIV-1 BaL was added to the cultures at 200 TCID50 (50% tissue culture infective dose) and incubated for an additional 48 h (the total volume of each well was 200 uL following all additions). Untreated cells (100% infected) were used as a positive control. Antiviral activity was measured by luciferase expression using the Promega Luciferase Assay System. Antiviral activity was plotted as a percent inhibition relative to the positive control (100% infection, virus exposure) and cell control (0% infected, no virus exposure). Nonlinear regression was used to fit the data to an inhibition model with a constant Hill coefficient to determine the slope parameter and IC50 value, which is the sample concentration giving 50% of relative luminescence units (RLUs) compared to the virus control after subtraction of background RLUs.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Prodrug Design.

Poor encapsulation of hydrophilic drugs into PLGA-NPs is caused primarily by insufficient partitioning of the drug into the organic phase of the oil-in-water emulsion.9,24 In addition, for drugs containing acidic or basic functional groups, poor partitioning is accentuated by partial or complete ionization in the aqueous phase. The low encapsulation efficiency and loading of RAL into PLGA-NP is driven by both of these factors. RAL exhibits a modest apparent POW across a wide pH range, varying from POW = 10 at pH 1 to POW = 0.03 at pH 9, whereas its aqueous solubility is significant even for the neutral form (1.3 mg/mL).22 Thus, the relatively weak partitioning of RAL in both ionization states leads to low drug loading irrespective of the pH used for the aqueous phase of the emulsion.

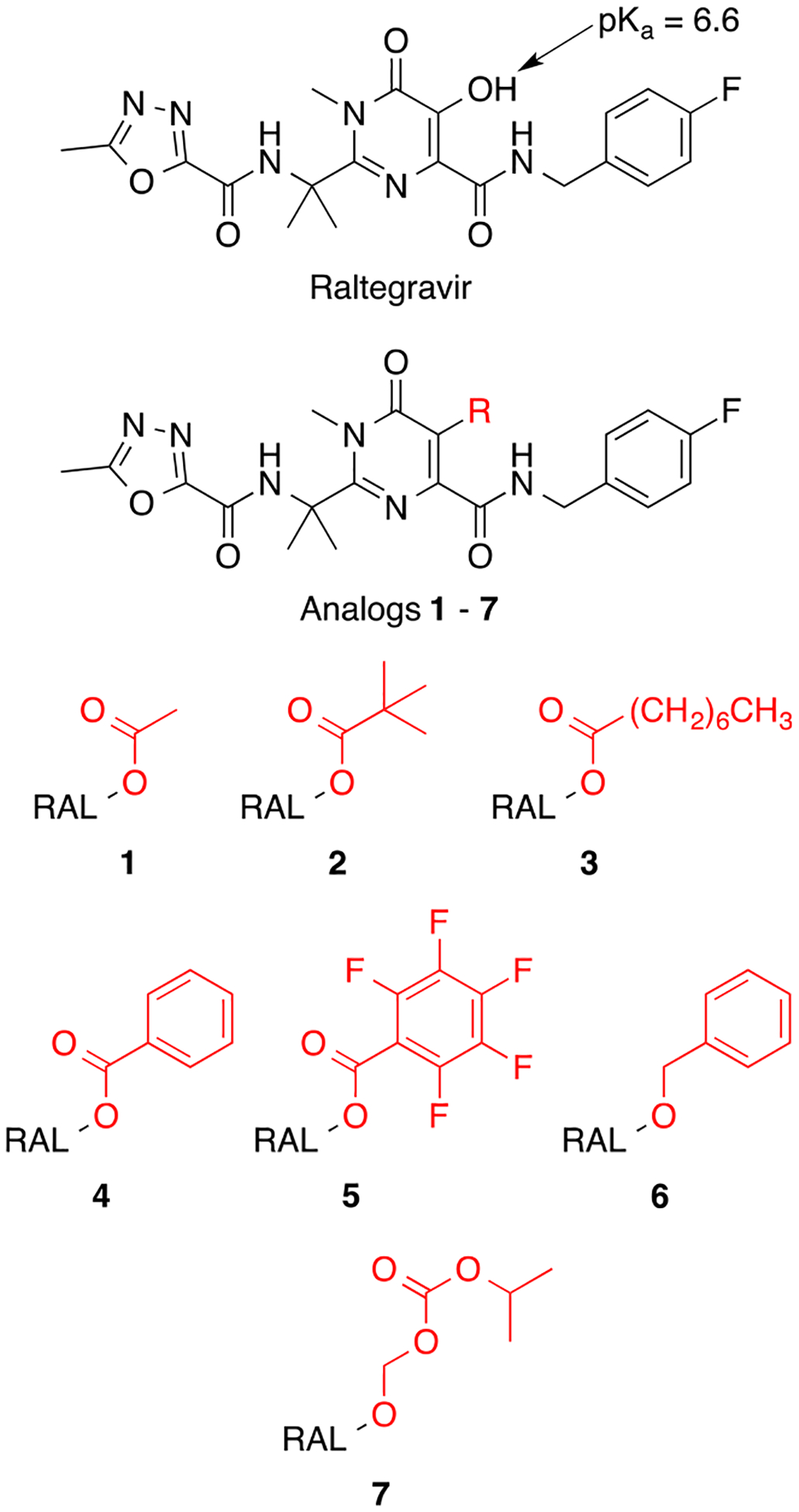

To address poor nanoparticle encapsulation of RAL we pursued a prodrug strategy designed to reversibly mask the ionizable hydroxyl group of the 5,6-dihydroxypyrimidine-4-carboxamide pharmacophore. This functional group is essential for integrase binding and also drives the partitioning of RAL into aqueous phases (Figure 1). Five potential prodrugs belonging to two broad classes were synthesized and evaluated with respect to hydrophobicity and hydrolysis rate (Figure 2). Analogs 1–4 represent simple esters introducing acyl groups with varying degrees of hydrophobicity and steric hindrance, while analog 7 is closely related to an acetal carbonate prodrug currently under development to improve colonic absorption and reduce dosing frequency (Merck & Co.).21 Two control molecules were also synthesized to distinguish between antiviral activity originating before or after prodrug hydrolysis. Compound 6 was designed as a nonhydrolyzable analog of 4, whereas compound 5 contains a promoiety sterically similar to 4 but that is activated with respect to ester hydrolysis (see below). All analogs prevented ionization over relevant pH ranges by masking the relatively acidic hydroxyl group of raltegravir’s 5,6-dihydroxypyrimidine-4-carboxamide core (Figure 3).25

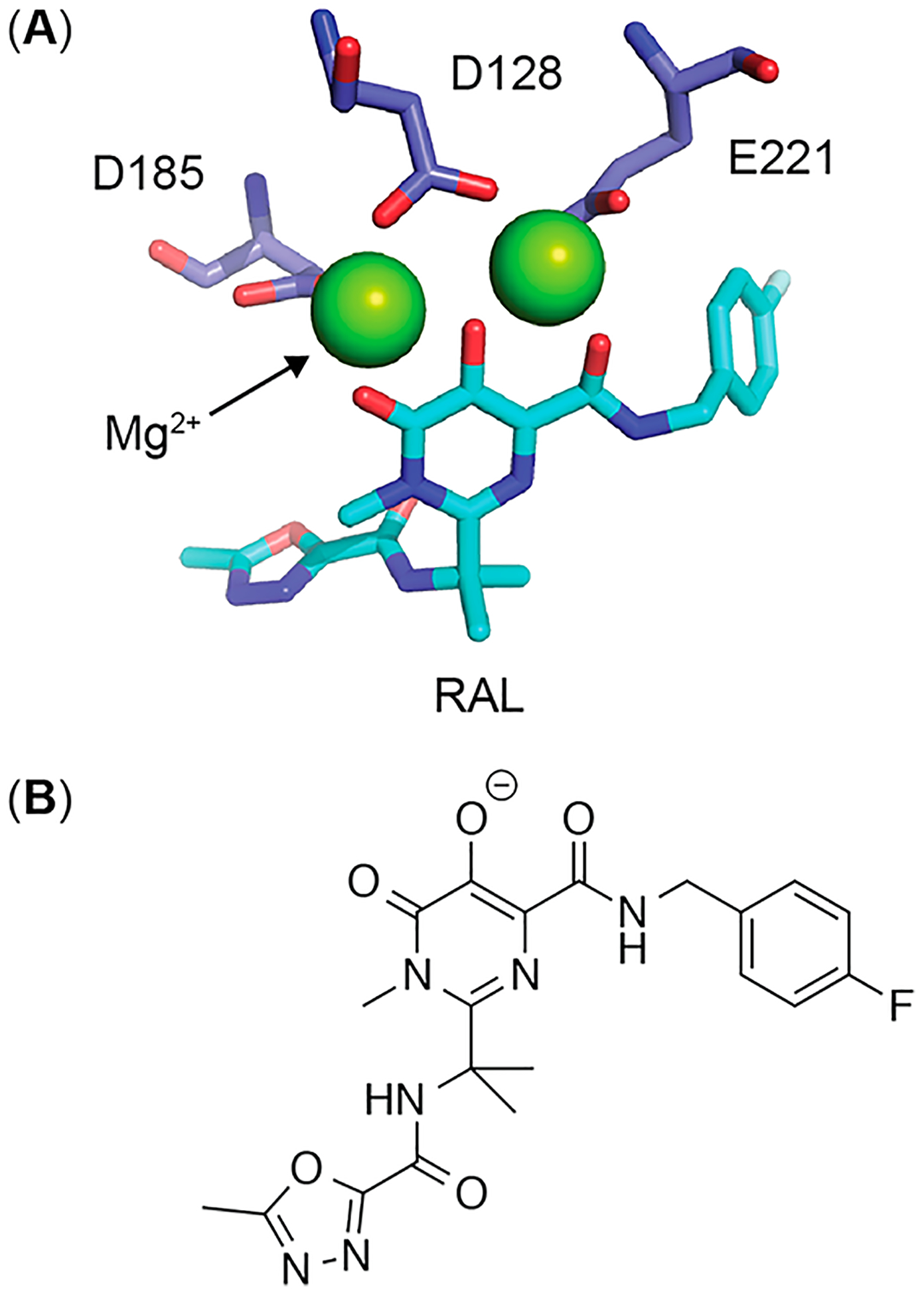

Figure 1.

(A) Active site region of prototype foamy virus integrase bound to raltegravir (cyan) and catalytic Mg2+ ions (green).34 (B) Raltegravir ionization state required for high affinity binding to active site Mg2+ ions.

Figure 2.

Chemical structure of raltegravir and raltegravir analogs 1–7.

Figure 3.

UV–vis titration of RAL and 4. The pKa value of RAL corresponds to ionization of the 5,6-dihydroxypyrimidine-4-carbox-amide ring. No significant change in absorption is observed for 4 across the pH range indicated.

Prodrug Partition Coefficients and Nanoparticle Loading.

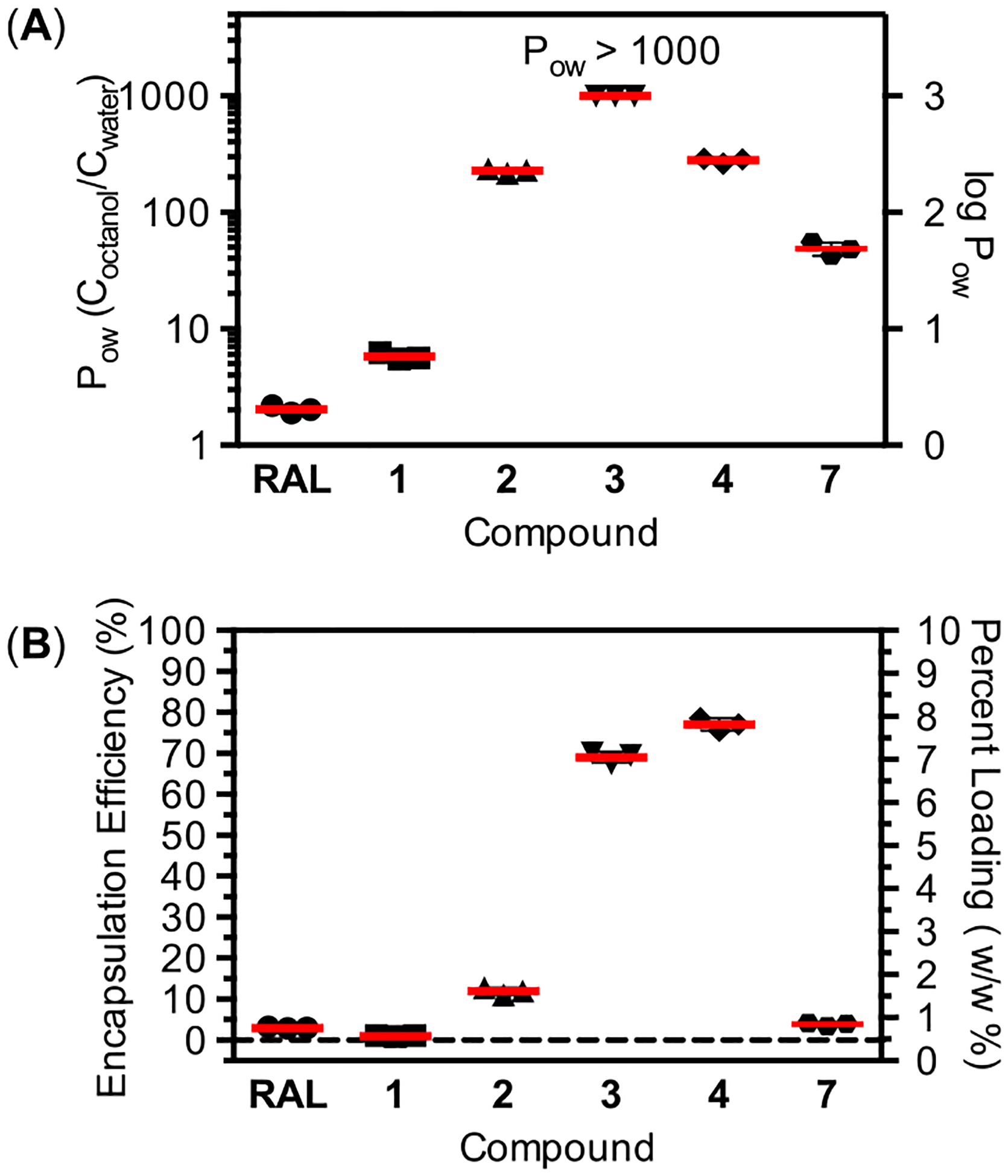

To investigate whether partition coefficients measured under standard conditions could be used to predict ARV-NP loading, we measured POW values for 1–4 and 7 in PBS (pH 7.4) as the aqueous phase (Figure 4A). At neutral pH RAL is >85% ionized (Figure 3) with an apparent POW = 2.0, a value that represents the partitioning of both neutral and ionized forms.22 Conversion of RAL to the acetyl ester 1 prevents ionization while introducing modest changes in hydrophobicity, resulting in a POW that is similar to that observed for RAL in the neutral ionization state (when the aqueous phase pH is well below the pKa of RAL).22 The introduction of ester promoieties of increasing hydrophobicity improves partitioning to the organic phase for 2–4 as expected, leading to at least a 500-fold increase in POW for 3. The concentration of 3 in the aqueous phase was below the limit of detection of our method, providing a lower limit for the value POW. The oxymethyl alkyl carbonate moiety of 7 also masks the ionizable group of RAL, leading to an increase in POW that could likely be tuned by the identity of the alkyl group.

Figure 4.

(A) Partition coefficients for 1–4 and 7. Partition coefficients were measured at pH 7.4 between PBS and 1-octanol. The value reported for RAL represents a distribution coefficient due to partial ionization of RAL at this pH. (B) Measured loading of 1–4 and 7 in PLGA-NP formulated using a double emulsion method with dichloromethane as the organic phase.

We measured the encapsulation efficiency and percent loading of RAL and 1–4 and 7 formulated in PLGA-NPs using a single-emulsion method (Figure 4B). As has been reported previously,17 RAL is poorly formulated in PLGA-NPs by single-emulsion with a resulting encapsulation efficiency of 3.0% and percent loading of 0.3 wt %. Efforts to improve the loading of RAL by adjusting the pH of the single emulsion or employing double-emulsion techniques with the potassium salt of RAL also failed to achieve high loading (unpublished result). In contrast, the introduction of promoieties at the ionizable hydroxyl of RAL had a dramatic and analog dependent effect on encapsulation efficiency and loading (Figure 4B). With the exception of 1, all analogs showed improved encapsulation efficiency and loading relative to RAL under identical PLGA-NP formulation conditions. Notably, 3 and 4 resulted in a 20–25-fold improvement in encapsulation efficiency relative to RAL. These values of encapsulation efficiency and percent loading approach some of the highest values reported for hydrophobic drugs under optimized PLGA-NP formulation conditions.26,27

Although standard POW values provide a basic framework to predict encapsulation efficiencies, the oil-in-water emulsions used to prepare the PLGA-NPs employ organic and aqueous phases that differ from those used for partition measurements in several important ways. In this study, PLGA-NPs were fabricated with an organic phase composed of dichloromethane containing 5% w/v PLGA, whereas the aqueous phase for the emulsion was a 5% w/v poly(vinyl alcohol) solution. The imperfect correspondence between POW values and encapsulation efficiencies for RAL analogs likely originates from differences in the bulk properties of the solvents (1-octanol versus dichloromethane), as well as specific interactions between each analog and the dissolved polymer (particularly as the oil phase concentrates through evaporation). Two interesting observations highlighting this point are the slightly higher encapsulation efficiency of 4 relative to 3 (despite a lower POW value), and the significantly lower encapsulation efficiency of 2 relative to 4 (despite similar POW values). Partition coefficients measured with the same organic solvent as the nanoparticle emulsion would likely show much stronger correlations to encapsulation efficiency. However, even in the absence of a direct relationship, standard POW values appear to provide some predictive power in the design of RAL analogs, namely that a POW > 100 is likely necessary but not sufficient to produce high encapsulation efficiency and loading.

Kinetics of Prodrug Hydrolysis.

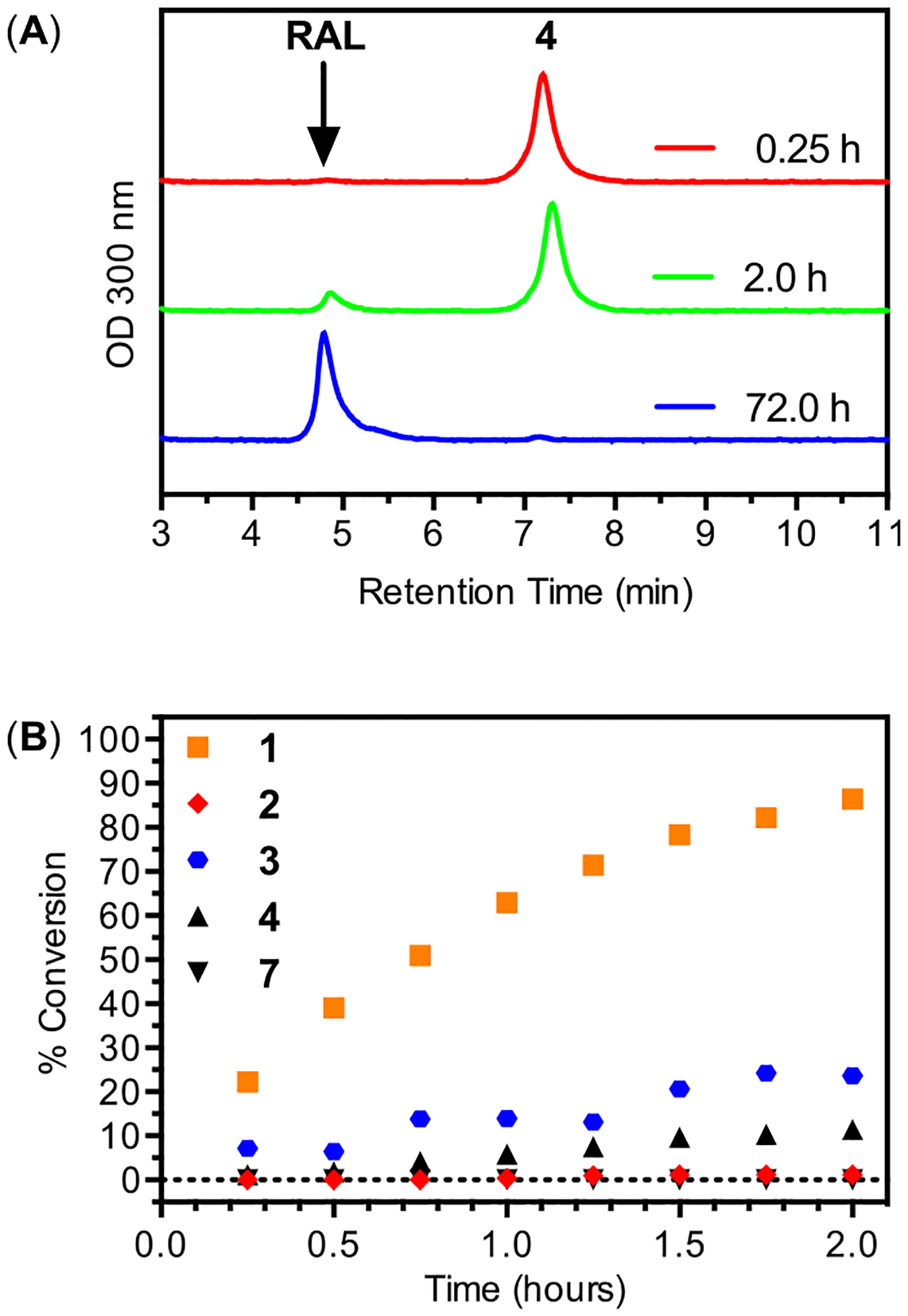

The relatively low pKa value of raltegravir’s ionizable hydroxyl group leads to accelerated rates of chemical hydrolysis for ester analogs 1–4. Although each of these analogs is stable during NP fabrication and in PBS solutions for weeks, hydrolysis studies conducted in solutions containing amino acids, including cell-culture media, led to half-lives in the range of hours (Figure 5 and Table 1). As expected, hydrolysis rates are dependent on ester structure, with the hydrolysis of 1 occurring ~10 times faster than 4 and ~100 times faster than 2, which is consistent with the established dependence of ester hydrolysis rates on sterics.28 Importantly, all RAL prodrugs convert completely to RAL as monitored by HPLC (Figure 5A). In contrast to analogs 1–4, analog 7 exhibits slow hydrolysis in cell culture media. This observation is consistent with the mechanism of oxymethyl alkyl carbonate hydrolysis, where the rate-determining step is carbonate hydrolysis and is not appreciably accelerated by the low pKa value of RAL. Although several of these hydrolysis rates are too rapid for conventional prodrug applications, the use of PLGA-NPs as delivery vehicles protects encapsulated prodrugs from chemical or enzymatic degradation (see below). Interestingly, the interplay between NP release kinetics and chemical hydrolysis rates leads to distinct patterns of drug availability for these analogs.

Figure 5.

(A) Representative HPLC chromatographs during hydrolysis of 4 to RAL in cell culture media at indicated times. (B) Hydrolysis conversion as a function of time for 1–4 and 7 in cell culture media (pH 7.4) at 20 °C.

Table 1.

Hydrolysis Half-Life of Analogs 1–7 in Cell Culture Media (pH 7.4) at 20 °C

Half-life determined by fitting percent conversion to a pseudo first-order rate expression.

No hydrolysis product observed out to 500 h.

Hydrolysis with half-life greater than 500 h. (~5% conversion at 250 h.).

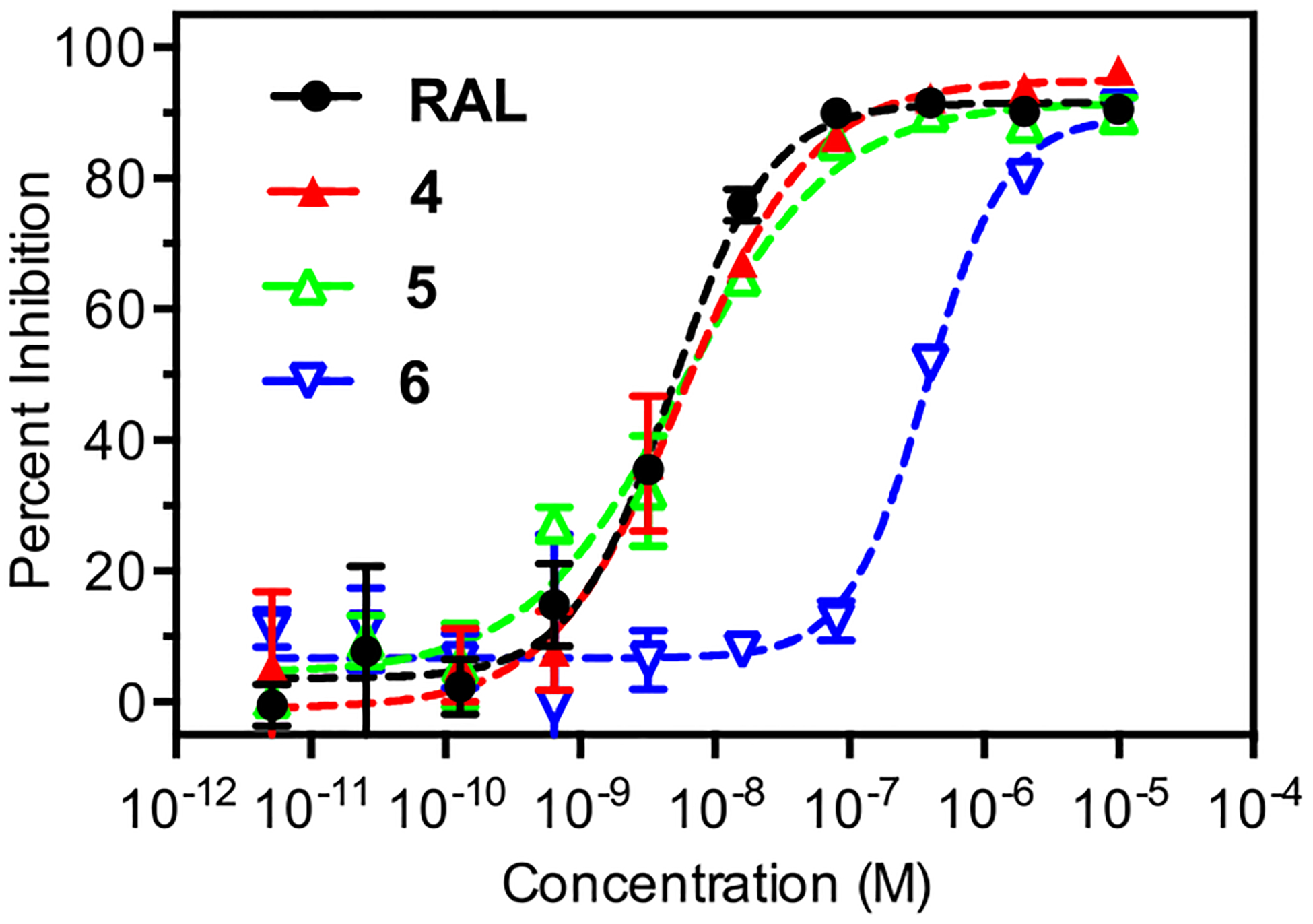

Antiviral Activity of RAL Prodrugs.

Based on the rapid hydrolysis of 1–4, HIV inhibition assays conducted with these analogs should result in IC50 values identical to RAL. However, a previous high-throughput assay identified 4 as a distinct integrase inhibitor with an IC50 value several orders of magnitude lower than RAL.20 This result suggests the ionizable hydroxyl of RAL is nonessential for integrase binding, while the benzoyl ester group of 4 contributes significantly to binding.20 To address this possibility, we synthesized two control molecules related to analog 4 (Figure 2). Analog 5 was designed to have similar sterics to 4, but with an increased rate of hydrolysis due to the electron withdrawing effect of the pentafluoro modification (Table 1). In contrast, analog 6 was designed to have similar sterics to 4, but with a nonhydrolyzable ether linkage (Table 1). If ester hydrolysis improves the antiviral activity of 4, then analog 5 should produce equivalent or better activity in HIV inhibition assays, while analog 6 should show reduced activity. The results of antiviral activity assays with 4–6, dosed in their unformulated forms, confirms the importance of ester hydrolysis (Figure 6). Analogs 4 and 5 produce antiviral activity that is identical to RAL, consistent with nearly complete ester hydrolysis on the time scale of the assay (48 h), whereas 6 exhibits an IC50 ~ 100-fold greater than RAL. Given the significant increase in IC50 for 6 it is possible that some fraction of this activity arises from the incomplete removal of RAL during analog purification (estimated to be less than 1% by NMR, see Figure S14). This pattern of activity suggests the ionizable hydroxyl group produced through hydrolysis is required for antiviral activity, a finding that is supported by the inner-sphere coordination of this oxygen to the catalytic magnesium ions of the integrase active site (Figure 1).

Figure 6.

HIV inhibition curves for RAL and 4–6 dosed as unformulated free compounds. IC50 values calculated from two replicates are as follows; RAL (4.5 ± 0.5 nM), 4 (5.7 ± 0.8 nM), 5 (5.6 ± 0.6 nM), 6 (360 ± 30 nM).

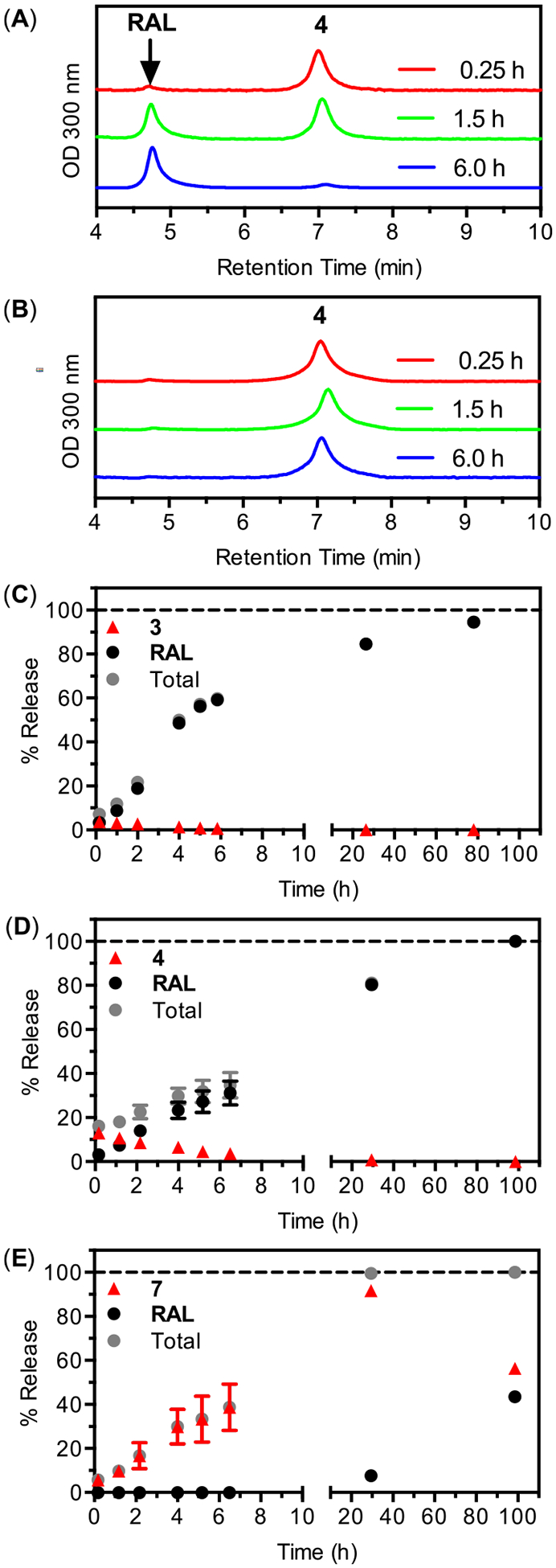

Kinetics of Prodrug Release from PLGA Nanoparticles.

A successful prodrug strategy for ARV-NP formulations must combine complete release over a desired time scale (or multiple time scales) with complete conversion to the parent drug through chemical and/or enzymatic hydrolysis. The process of hydrolysis will impact NP release for some prodrugs since the hydrolysis of hydrophobic prodrugs often produces parent compounds with increased water solubility. To investigate this process, the release kinetics of ARV-NPs containing 3, 4, and 7 were measured in cell culture medium at 37 °C (Figure 7). Each ARV-NP formulation showed release past 24 h, with released prodrug converting to RAL in the supernatant (Figure 7A). ARV-NP collected at time points prior to 100% release showed no evidence of prodrug conversion within the NP (Figure 7B). This observation suggests that prodrug release precedes hydrolysis for these analogs, in contrast to prodrug polymer conjugates where hydrolysis is required for release. Although NP encapsulation protects RAL prodrugs from hydrolysis, the subsequent conversion to RAL in solution has the potential to accelerate prodrug release. Conversion to RAL and prodrug diffusion both contribute to the establishment of a sink condition in these systems, and may be responsible for the relatively rapid release compared to drugs of similar hydrophobicity.

Figure 7.

Release and conversion of 3, 4, and 7 from PLGA nanoparticles incubated in cell culture media at 37 °C. (A) HPLC chromatographs of supernatant removed from nanoparticles containing 4 at various times. (B) HPLC chromatographs of pelleted nanoparticles containing 4, collected by centrifugation and dissolved in DMSO at various times. (C–E) Release kinetics and conversion to RAL as a function of time for 3, 4 and 7.

Interestingly, the observed differences in hydrolysis rates for these analogs produces distinct patterns of RAL availability following release. For analog 3 the composition of released drug is evenly distributed between prodrug and RAL at the earliest times, but shifts toward RAL within the first hour. After this time, accumulated RAL dominates the composition of the supernatant, with unhydrolyzed prodrug comprising an insignificant fraction of the total release past 2 h (Figure 7C). The pattern of release and hydrolysis is similar for 4 (Figure 7D), but with prodrug concentrations dominating at early times and comprising a significant fraction of the total released drug to longer times, likely reflecting the decreased rate of hydrolysis for this analog. In contrast, the release profiles of ARV-NPs containing 7 produce a supernatant composition that is dominated by the prodrug (Figure 7E). Raltegravir is undetectable in the supernatant within the first 6 h for ARV-NPs containing 7, despite significant prodrug release, and constitutes only half of the total released drug at 100 h. The slow chemical hydrolysis of 7 explains this release profile (Table 1) and leads to a distinct pattern of antiviral activity (see below).

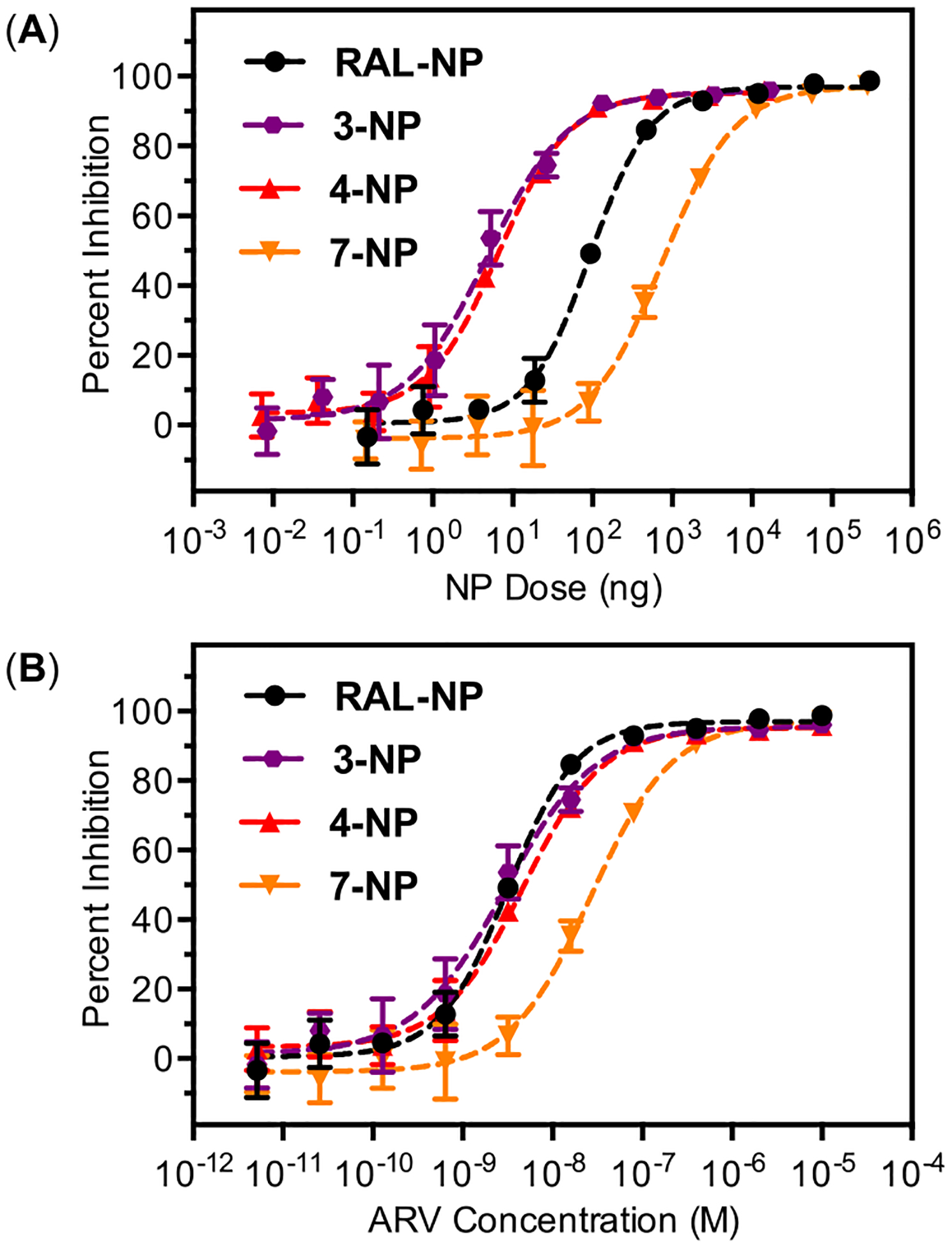

Antiviral Activity of Prodrug Loaded ARV-NP.

Based on the observed conversion of prodrugs to RAL in cell culture media we anticipated the antiviral activity of prodrug loaded ARV-NP would depend on the loading, release kinetics and rates of hydrolysis for each analog. To test this expectation we determined the antiviral activity of ARV-NP formulations containing RAL and analogs 3, 4, and 7 (Figure 8). The antiviral activity of ARV-NPs is expressed as a function of ARV-NP mass (Figure 8A) and as a function of molar ARV concentration calculated from the measured percent loading of the analog (Figure 8B). For a fixed mass of ARV-NPs, analogs 3 and 4 show a significant dose reduction relative to RAL (Figure 8A). This dose reduction arises from the improved loading of these analogs relative to RAL and the release and conversion of relevant amounts of bioactive drug during the time course of the assay. In contrast, ARV-NP loaded with 7 show reduced activity relative to RAL despite very similar loading. The origin of this reduced activity is likely the slow conversion of 7 to RAL following NP release (less than 10% conversion after 24 h in cell culture media). Inhibition curves normalized to drug loading and representing final ARV concentrations highlight this point. When normalized to drug loading, ARV-NPs containing 3 and 4 show nearly identical activity to RAL, consistent with the LC-MS/MS data indicating similar amounts of bioactive RAL for analog-NP and free analog treated cells (see below), whereas the incomplete hydrolysis of 7 leads to a nearly 10-fold decrease in activity (Figure 8B). Although the presence of endogenous esterases in the antiviral assay likely accelerates the conversion of 7 to RAL relative to half-lives measured in cell culture media, this acceleration appears to be insufficient to produce equivalent levels of RAL intracellularly. The differential activity of ARV-NPs loaded with analogs 3, 4, and 7 demonstrates the potential to modulate the activity of nanoparticle formulations through the synthesis and encapsulation of appropriate prodrugs.

Figure 8.

HIV inhibition curves for RAL and 3, 4, and 7 dosed as PLGA nanoparticle formulations (ARV-NP). (A) Inhibition produced by dosing the indicated mass of ARV-NP to assay wells of constant volume (200 μL). (B) Inhibition data scaled by percent loading of ARV-NP to reflect concentration of ARV following 100% release. IC50 values calculated from four replicates are as follows; RAL (3.2 ± 0.2 nM), 3 (2.9 ± 0.4 nM), 4 (4.6 ± 0.3 nM), and 7 (27 ± 2 nM).

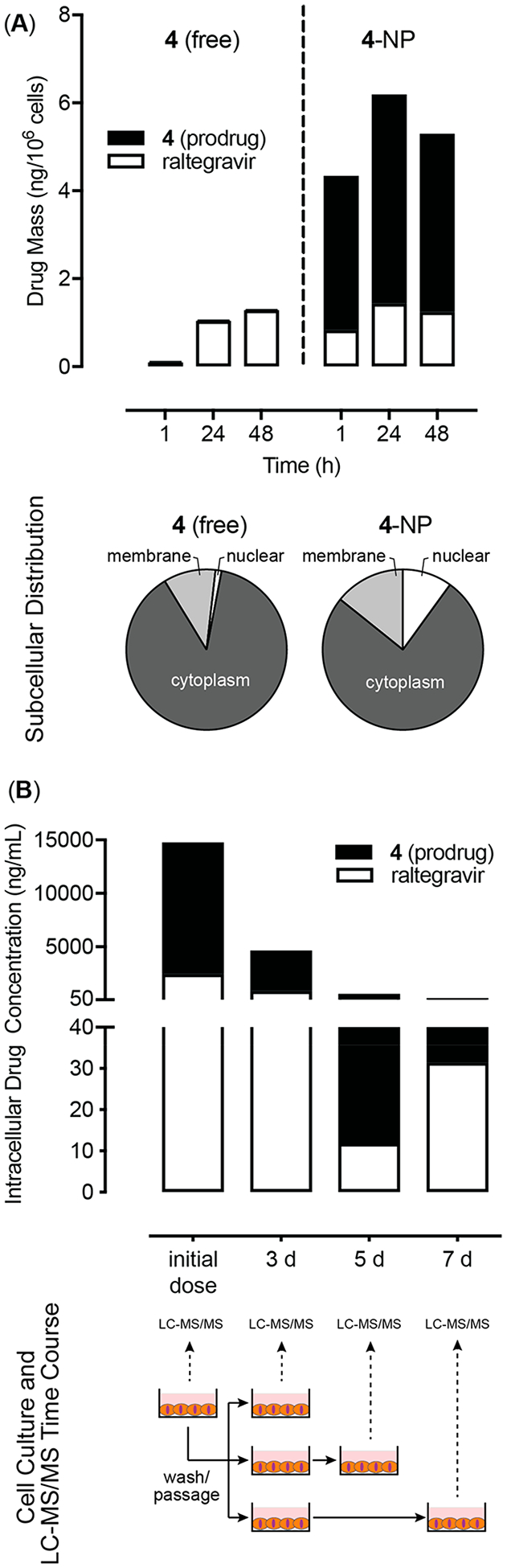

Intracellular Prodrug Release and Hydrolysis Kinetics.

The antiviral activity of prodrug-loaded ARV-NPs is dictated by the kinetics of several simultaneous processes, including the rate of nanoparticle uptake by cells, the rate of prodrug release and hydrolysis, and the rate of particle trafficking or drug diffusion to relevant cellular compartments. To understand how these processes contribute to the observed antiviral activity we used LC-MS/MS to determine the intracellular distribution of 4, as well as RAL produced through the hydrolysis of 4, after incubation with ARV-NPs containing analog 4 (4-NP). Analog 4 was selected for intracellular distribution studies because its pattern of release and hydrolysis provided a method to differentiate particle associated prodrug from released RAL. For this analog only the prodrug remains associated with nanoparticles during release studies (Figure 7B), whereas the composition of released drug is nearly 100% RAL at the time scale of the antiviral activity assay chosen.

On the basis of previous studies of nanoparticle uptake,29–31 we hypothesized that cells treated with 4-NP would exhibit higher total drug concentrations (4 + RAL) compared to cells treated with unformulated analog. We also expected to observe sustained total drug concentrations, with conversion of 4 to RAL over time. Both of these expectations were confirmed via LC-MS/MS analysis of intracellular drug concentrations. Cells treated with 4-NP showed significantly higher total drug concentrations with a higher fraction of prodrug depot at all time points relative to unformulated analog (Figure 9A). The release and subsequent hydrolysis of 4 during these intracellular measurements was slower than that observed in cell media, likely due to the absence of sink conditions inside the cell. This slower intracellular release produces a significant reservoir of NP associated prodrug that persists within the cells well past the 48 h of the antiviral activity assay. The slow decrease in total drug content at longer time scales for ARV-NP treated cells is likely due to a combination of cell division and NP exocytosis.32,33 In contrast, cells treated with equivalent concentrations of unformulated 4 showed much lower total drug concentrations (4 + RAL), with only RAL observed intracellularly by LC-MS/MS analysis. This finding is consistent with the rapid hydrolysis of 4 and the previously measured uptake of free RAL by TZM-bL cells.17 We observed that delivery of unformulated 4 and 4-NP results in similar concentrations of the bioactive RAL in the cytoplasm at the time point of the antiviral assay (t = 48 h), which would explain the similar antiviral activity that was measured (Figure 8). The origin of this similar intracellular concentration of bioactive RAL is expected to arise from diffusive transport of RAL into the cell following delivery and complete hydrolysis of 4 extracellularly. In contrast, a reverse gradient of high intracellular drug concentration arises from a depot of 4-NP releasing the prodrug that is then rapidly hydrolyzed to RAL.

Figure 9.

Nanoparticle uptake, retention and intracellular drug release of 4. (A) Total intracellular conversion of the prodrug (filled) to the bioactive parent compound (open) following delivery of 4 as free (left) or NP-formulated (right). Subcellular biodistribution of total intracellular drug (RAL + 4) for cells dosed with free 4 (left) or 4-NP (right) before any wash and passage steps. (B) Changes in total intracellular 4 (filled) and RAL (open) following treatment with 4-NP. Measurements at days 3, 5, and 7 were preceded by a wash and passage step.

To measure potential drug depots residing in the NPs, we initially dosed cells with the analog 4-NP and cultured them for 3 days. The cells were then extensively washed to remove any nanoparticles not internalized and any free RAL (both intracellular and extracellular, due to the rapid diffusion of RAL across the cell membrane). Following this wash step the only source of RAL in the system is from internalized nanoparticles encapsulating analog 4. The washed cells were then passaged and replated at densities that would reach confluency at specified end points for LC-MS/MS analysis (Figure 9B, bottom). Dosing with 4-NP resulted in both prodrug (NP associated) and bioactive parent RAL (released from NPs) detected intracellularly at all time points (Figure 9B, top). We also found evidence of intracellular depots of 4-NP that gave rise to accumulation of parent RAL on day 5 and 7 following the cell washing steps. In contrast, RAL was detected intracellularly prior to the wash step when the same experiment was conducted with only free 4, and no drug could be detected intracellularly after the wash step as would be expected following diffusive loss (data not shown). LC-MS/MS was also used to determine the subcellular distribution of both prodrug and parent RAL after dosing of either 4 or 4-NP (Figure 9A, bottom). Samples treated with 4-NP contained 5-fold more total drug intracellularly and also showed preferential drug partitioning to the nucleus compared to samples treated with unformulated 4. These preliminary data suggest a potential for persistent and long-acting protection from HIV infection in groups treated with ARV-NP formulations compared to free drug.

Quantitating intracellular drug concentrations by LC-MS/MS provides a better understanding of the origin of antiviral activity for prodrug loaded NPs, particularly relative to unformulated prodrugs or RAL. The slow hydrolysis of NP associated prodrugs allows the technique to distinguish between the bioactive RAL produced through release and hydrolysis and the nanoparticle-associated prodrug primarily responsible for high total drug concentrations. The technique also provides a direct measure of RAL concentrations in relevant cellular compartments. Our LC-MS/MS data suggests that drug release rates from PLGA nanoparticles differ significantly intracellularly compared to in vitro “sink” conditions. We also show that delivery of 4 formulated in PLGA nanoparticles results in intracellular drug depots and preferential partitioning to nuclear compartments whereas the unformulated drug accumulates in the cell cytosol.

CONCLUSION

In principle, the ability to tune the release kinetics and hydrolysis rates of NP encapsulated prodrugs provides a number of unique opportunities to control drug compartmentalization, pharmacokinetics and resulting activity. Unlike prodrugs developed for traditional delivery strategies, the selection of promoieties for NP encapsulation is not constrained by properties related to GI tract stability, absorption kinetics or membrane permeation, since these characteristics are largely controlled by the NP carrier. The ability to combine the favorable attributes of a given NP carrier with a wider diversity of acceptable promoieties should facilitate the design of prodrugs based on optimal release and hydrolysis profiles. These profiles will dictate the spatial and temporal distribution of prodrug and parent compound following NP uptake and intracellular release. We have demonstrated the use of a mass spectrometry method to determine intracellular release and hydrolysis of prodrugs, which could further inform prodrug design and aid in interpretation of antiviral activity.

The pattern of release and hydrolysis observed for analogs 3, 4, and 7 demonstrates that promoiety selection can have a meaningful impact on the kinetics of release, and a dramatic influence on the availability of prodrug and parent compound at multiple time scales. We observed that differences in hydrophobicity and half-life impact the pattern of compartmentalization previously observed for RAL loaded ARV-NP.17 The differential loading of these prodrugs during NP formulation also highlights the potential to modulate the composition of multiple prodrugs exhibiting distinct properties within a single formulation. In principle developing hybrid ARV-NP with multiple RAL prodrugs and characterizing their intracellular release using LC-MS/MS would allow for programmable and sustained intracellular concentrations of RAL.

Although our current set of RAL prodrugs samples a relatively small space with respect to property permutations, larger libraries with variable loading, hydrolysis and release kinetics could easily be synthesized.20,21 Of particular interest is the development of prodrugs that produce high loading with slow rates of hydrolysis, to complement the high loading and rapid hydrolysis observed for analogs 3 and 4. By carefully tuning prodrug properties and their ratios during NP fabrication it should be possible to control the temporal antiviral activity of ARV-NP formulations in a way that is dependent solely on the kinetics of release and hydrolysis, avoiding many of the limitations facing traditional prodrug strategies.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This work was supported by the US National Institutes of Health grant (AI094412) to K.A.W. M.E.E. was supported through the MJ Murdock Charitable Trust (Murdock College Undergraduate Research Award: 201221:HVP). A.M.B. was supported through the Clare Boothe Luce Program and Henry Luce Foundation.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ARV

antiretroviral

- PLGA

poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)

- RAL

raltegravir

- HPLC

high performance liquid chromatography

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- POW

partition coefficient measured with 1-octanol as the organic phase and a defined buffer as the aqueous phase

- NP

nanoparticle

- ARV-NP

antiretroviral loaded nanoparticles

- 4-NP

nanoparticles loaded with compound 4

- PLGA-NP

nanoparticles synthesized from poly-(lactic-co-glycolic acid)

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.9b00658.

Detailed synthetic procedures and characterization data for analogs 1–7 and ARV-NP characterization data (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Danhier F; Ansorena E; Silva JM; Coco R; Le Breton A; Preat V PLGA-based nanoparticles: An overview of biomedical applications. J. Controlled Release 2012, 161 (2), 505–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Panyam J; Labhasetwar V Biodegradable nanoparticles for drug and gene delivery to cells and tissue. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev 2012, 64, 61–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Panyam J; Zhou WZ; Prabha S; Sahoo SK; Labhasetwar V Rapid endo-lysosomal escape of poly(DL-lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticles: implications for drug and gene delivery. FASEB J. 2002, 16 (10), 1217–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Hines DJ; Kaplan DL Poly(lactic-co-glycolic) Acid-Controlled-Release Systems: Experimental and Modeling Insights. Crit. Rev. Ther. Drug Carrier Syst 2013, 30 (3), 257–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Natarajan JV; Nugraha C; Ng XW; Venkatraman S Sustained-release from nanocarriers: a review. J. Controlled Release 2014, 193, 122–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Mundargi RC; Babu VR; Rangaswamy V; Patel P; Aminabhavi TM Nano/micro technologies for delivering macro-molecular therapeutics using poly(D,L-lactide-co-glycolide) and its derivatives. J. Controlled Release 2008, 125 (3), 193–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Freiberg S; Zhu X Polymer microspheres for controlled drug release. Int. J. Pharm 2004, 282 (1–2), 1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Cohen-Sela E; Chorny M; Koroukhov N; Danenberg HD; Golomb G A new double emulsion solvent diffusion technique for encapsulating hydrophilic molecules in PLGA nanoparticles. J. Controlled Release 2009, 133 (2), 90–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Govender T; Stolnik S; Garnett MC; Illum L; Davis SS PLGA nanoparticles prepared by nanoprecipitation: drug loading and release studies of a water soluble drug. J. Controlled Release 1999, 57 (2), 171–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Rautio J; Kumpulainen H; Heimbach T; Oliyai R; Oh D; Jarvinen T; Savolainen J Prodrugs: design and clinical applications. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2008, 7 (3), 255–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Luo C; Sun J; Sun BJ; He ZG Prodrug-based nanoparticulate drug delivery strategies for cancer therapy. Trends Pharmacol. Sci 2014, 35 (11), 556–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Chaowanachan T; Krogstad E; Ball C; Woodrow KA Drug Synergy of Tenofovir and Nanoparticle-Based Antiretrovirals for HIV Prophylaxis. PLoS One 2013, 8 (4), e61416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).das Neves J; Araujo F; Andrade F; Amiji M; Bahia MF; Sarmento B Biodistribution and Pharmacokinetics of Dapivirine-Loaded Nanoparticles after Vaginal Delivery in Mice. Pharm. Res 2014, 31 (7), 1834–1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).das Neves J; Michiels J; Arien KK; Vanham G; Amiji M; Bahia MF; Sarmento B Polymeric Nanoparticles Affect the Intracellular Delivery, Antiretroviral Activity and Cytotoxicity of the Microbicide Drug Candidate Dapivirine. Pharm. Res 2012, 29 (6), 1468–1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Destache CJ; Belgum T; Christensen K; Shibata A; Sharma A; Dash A Combination antiretroviral drugs in PLGA nanoparticle for HIV-1. BMC Infect. Dis 2009, 9, 198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Shibata A; McMullen E; Pham A; Belshan M; Sanford B; Zhou Y; Goede M; Date AA; Destache CJ Polymeric Nanoparticles Containing Combination Antiretroviral Drugs for HIV Type 1 Treatment. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 2013, 29 (5), 746–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Jiang Y; Cao S; Bright DK; Bever AM; Blakney AK; Suydam IT; Woodrow KA Nanoparticle-Based ARV Drug Combinations for Synergistic Inhibition of Cell-Free and Cell-Cell HIV Transmission. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2015, 12 (12), 4363–4374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Date AA; Shibata A; Goede M; Sanford B; La Bruzzo K; Belshan M; Destache CJ Development and evaluation of a thermosensitive vaginal gel containing raltegravir plus efavirenz loaded nanoparticles for HIV prophylaxis. Antiviral Res. 2012, 96 (3), 430–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Jilek BL; Zarr M; Sampah ME; Rabi SA; Bullen CK; Lai J; Shen L; Siliciano RF A quantitative basis for antiretroviral therapy for HIV-1 infection. Nat. Med 2012, 18 (3), 446–U211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Wang ZW; Wang MX; Yao X; Li Y; Qiao WT; Geng YQ; Liu YX; Wang QM Hydroxyl may not be indispensable for raltegravir: Design, synthesis and SAR Studies of raltegravir derivatives as HIV-1 inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem 2012, 50, 361–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Walji AM; Sanchez RI; Clas SD; Nofsinger R; Ruiz MD; Li J; Bennet A; John C; Bennett DJ; Sanders JM; Di Marco CN; Kim SH; Balsells J; Ceglia SS; Dang Q; Manser K; Nissley B; Wai JS; Hafey M; Wang JY; Chessen G; Templeton A; Higgins J; Smith R; Wu YH; Grobler J; Coleman PJ Discovery of MK-8970: An Acetal Carbonate Prodrug of Raltegravir with Enhanced Colonic Absorption. ChemMedChem. 2015, 10 (2), 245–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Moss DM; Siccardi M; Murphy M; Piperakis MM; Khoo SH; Back DJ; Owen A Divalent Metals and pH Alter Raltegravir Disposition In Vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56 (6), 3020–3026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).OECD Test No. 107: Partition Coefficient (N-octanol/water): Shake Flask Method; OECD Publishing: Paris, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- (24).Fessi H; Puisieux F; Devissaguet J; Ammoury N; Benita S Nanocapule formation by interfacial polymer deposition following solvent displacement. Int. J. Pharm 1989, 55 (1), R1–R4. [Google Scholar]

- (25).Summa V; Petrocchi A; Bonelli F; Crescenzi B; Donghi M; Ferrara M; Fiore F; Gardelli C; Paz OG; Hazuda DJ; Jones P; Kinzel O; Laufer R; Monteagudo E; Muraglia E; Nizi E; Orvieto F; Pace P; Pescatore G; Scarpelli R; Stillmock K; Witmer MV; Rowley M Discovery of Raltegravir, a potent, selective orally bioavailable HIV-integrase inhibitor for the treatment of HIV-AIDS infection. J. Med. Chem 2008, 51 (18), 5843–5855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Panyam J; Williams D; Dash A; Leslie-Pelecky D; Labhasetwar V Solid-state solubility influences encapsulation and release of hydrophobic drugs from PLGA/PLA nanoparticles. J. Pharm. Sci 2004, 93 (7), 1804–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Fonseca C; Simoes S; Gaspar R Paclitaxel-loaded PLGA nanoparticles: preparation, physicochemical characterization and in vitro anti-tumoral activity. J. Controlled Release 2002, 83 (2), 273–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Taft RW Polar and Steric Substituent Constants for Aliphatic and O-Benzoate Groups from Rates of Esterification and Hydrolysis of Esters. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1952, 74 (12), 3120–3128. [Google Scholar]

- (29).Shah LK; Amiji MM Intracellular delivery of saquinavir in biodegradable polymeric nanoparticles for HIV/AIDS. Pharm. Res 2006, 23 (11), 2638–2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Sahoo SK; Panyam J; Prabha S; Labhasetwar V Residual polyvinyl alcohol associated with poly (D,L-lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticles affects their physical properties and cellular uptake. J. Controlled Release 2002, 82 (1), 105–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Cartiera MS; Johnson KM; Rajendran V; Caplan MJ; Saltzman WM The uptake and intracellular fate of PLGA nanoparticles in epithelial cells. Biomaterials 2009, 30 (14), 2790–2798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Panyam J; Labhasetwar V Dynamics of endocytosis and exocytosis of poly(D,L-lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticles in vascular smooth muscle cells. Pharm. Res 2003, 20 (2), 212–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Kim JA; Aberg C; Salvati A; Dawson KA Role of cell cycle on the cellular uptake and dilution of nanoparticles in a cell population. Nat. Nanotechnol 2012, 7 (1), 62–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Hare S; Vos AM; Clayton RF; Thuring JW; Cummings MD; Cherepanov P Molecular mechanisms of retroviral integrase inhibition and the evolution of viral resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S. A 2010, 107 (46), 20057–20062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.