Abstract

Bacterial cells utilize small carbohydrate building blocks to construct their peptidoglycan (PG), a mesh-like polymer that serves as a protective coat for the cell. While highly conserved, this material’s production has long been a target for antibiotics while its breakdown is a source for human immune recognition. A key component of bacterial PG, N-acetyl muramic acid (NAM), is a vital element in many synthetically derived immunostimulatory compounds. However, the exact molecular details of these structures as well as how they are generated remains unknown due to the lack of chemical probes surrounding the NAM core. A robust synthetic strategy to generate bioorthogonally tagged NAM carbohydrate units is implemented. These molecules serve as precursors for PG biosynthesis and recycling. E. coli cells are metabolically engineered to incorporate the bioorthogonal NAM probes into their PG network. The chemical probes are subsequently modified using Copper-catalyzed azide alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) to install fluorophores directly into the bacterial PG as confirmed by super-resolution microscopy and high resolution mass spectrometry. Here, synthetic notes for key elements of this process to generate the sugar probes as well as streamlined “user friendly” metabolic labeling strategies for both microbiology and immunological applications are described.

Basic Protocol 1:

Synthesis of Peracetylated 2-Azido Glucosamine (1)

Basic Protocol 2:

Synthesis of 2-azido NAM (2) and 2-alkyne NAM (3)

Basic Protocol 3:

Synthesis of 3-azido NAM methyl ester (4)

Basic Protocol 4:

Bacterial remodeling

Basic Protocol 5:

Mass spectrometry bacterial cell wall remodeling confirmation

Keywords: Carbohydrates, bacterial peptidoglycan, metabolic incorporation, mass spectrometry, microscopy, fluorescent labeling, bioorthogonal chemistry, click chemistry

Introduction

Bacterial peptidoglycan (PG), a component of bacterial cell wall, is one of the essential polymers for life. Bacterial cells are surrounded by this material, which assists in bacterial cell division, maintenance of cell shape and small molecule recognition and signaling (Höltje, 1998). Bacterial species are divided into two classes based on the construction of this polymer: Gram-positive organisms contain a thick PG layer whereas Gram-negative bacteria have a thin PG layer and an outer membrane decorated with such modifications as lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Bacterial PG is composed of alternating β 1–4 linked units of N-acetyl glucosamine (NAG) and N-acetyl muramic acid (NAM), with short peptide chains containing both l and d amino acids present on the muramic acid residue (Figure 1) (Rogers, 1974). The peptides can be further crosslinked and trimmed to reveal the mature PG structure. These molecular building blocks can combine in a variety of ways to produce a range of macromolecular structures, with NAG and NAM remaining constant throughout all bacteria (Figure 1) (Rogers, 1974; D’Ambrosio et al., 2019). These structurally diverse PG elements directly impact human health, as antibiotics are designed to target the polymer’s destruction while the innate immune system senses and responds to bacteria via fragments of PG (Walsh, 2000; Strominger, 2007).

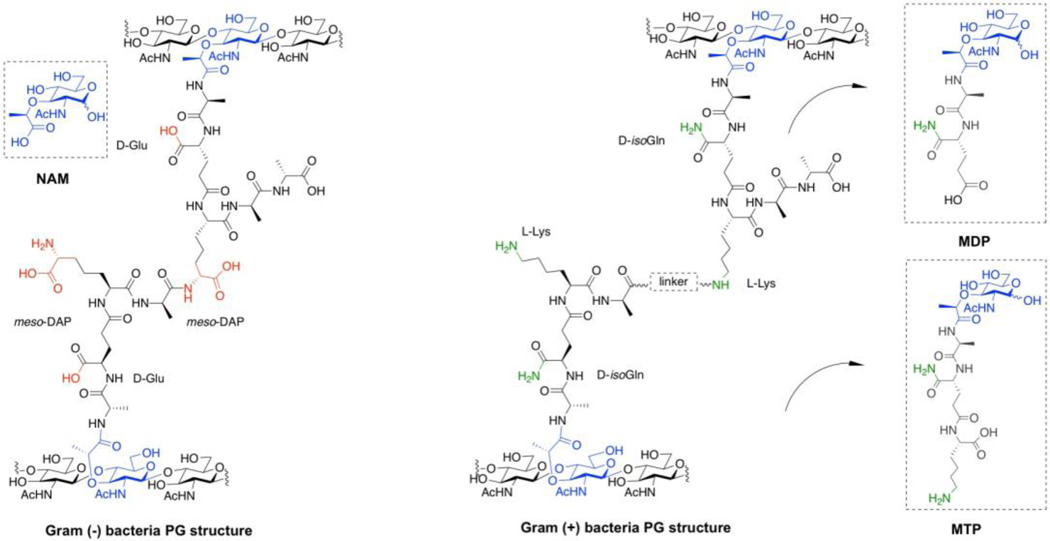

Figure 1. Chemical structure of bacterial PG of both Gram-negative and Gram-positive organisms.

Gram-negative bacterial cells normally use meso-diaminopimelic acid (meso-DAP, red) and d-glutamic acid (d-Glu, red) in their PG structure. In Gram-positive bacteria, the peptide chains normally consist of d-isoglutamine (d-isoGln, green) and l-lysine (l-Lys, green)

Despite variations in mature PG composition (Figure 1), PG biosynthesis is a highly conserved cellular process involving more than ten distinct enzymatic steps. This program begins with the formation of uridine diphosphate NAM (UDP-NAM) through MurA/B and UDP N-acetyl glucosamine (UDP-NAG) (Brown et al., 1995; Pucci et al., 1992). Five peptides are stitched onto the 3-OH position of UDP-NAM to form Park’s nucleotide through enzymes MurC-F (Barreteau et al., 2008; Falk et al., 2002; Bertrand et al., 1997; Gordon et al., 2001; Yan et al., 1999). The peptide structure can vary between Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, but still maintains the alternating l and d amino acid pattern (Rogers, 1974) (Figure 1). MraY links Park’s nucleotide to the cell membrane where MurG then glycosylates this fragment with N-acetyl glucosamine (NAG) to form Lipid II (Bouhss et al., 2004; Bugg and Walsh, 1992). MurJ transports Lipid II into the periplasmic space where transglycosylases (TGases) and transpeptidases (TPases) further cross-link the glycan and peptide portions of this polymer to form the mature PG (Figure 2) (Sham et al., 2014; Ruiz, 2008; van Heijenoort, 2001).

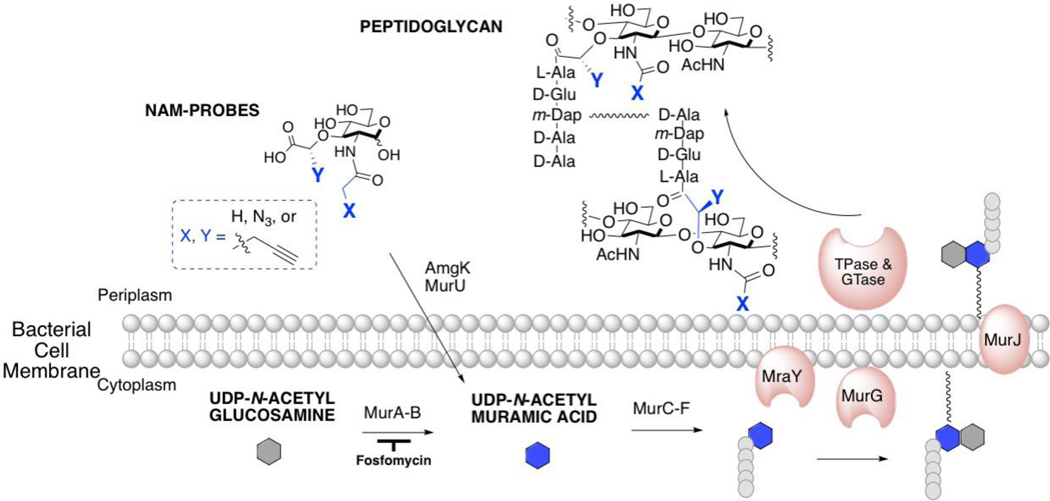

Figure 2. PG biosynthesis begins with the formation of UDP-NAM through MurA/B and UDP-NAG.

Recycling enzymes AmgK/MurU provide another route to synthesize UDP-NAM with NAM as the building block. UDP-NAM is converted into Park’s nucleotide through enzymes MurC-F. MraY links Park’s nucleotide to the cell membrane where MurG then glycosylates this Lipid I fragment to form Lipid II. MurJ transports Lipid II into the periplasmic space where transglycosylases (TGase) and transpeptidases (TPase) further cross-link these molecules to form the mature PG. NAM probes (blue) with biorthogonal functionality either at the 2-N position (X) or 3-lactic acid position (Y) are metabolically incorporated into PG through both recycling and biosynthetic machineries.

To strategically develop a NAM-based labeling method, inspiration was drawn from bacterial PG composition and biosynthesis. The biosynthesis of PG and its molecular intermediates have been known and well characterized since the late 1950s (Strominger et al., 1959). The PG polymer to be modified is highly cross-linked and its synthesis is conserved, involving more than ten distinct enzymatic steps (Figure 2). Motivation to utilize the biosynthetic machinery to tag this polymer was driven from enormous efforts and successes with in vivo labeling of macromolecular structures. Pioneering work conducted by Bertozzi and Mahal introduced bioorthogonal functionality into eukaryotic glycans (Mahal et al., 1997; Saxon et al., 2000; Saxon and Bertozzi, 2000; Aronoff et al., 2016). Bioorthogonal functionalization allows for the incorporation of chemical moieties onto small molecules, proteins, and nucleic acids that subsequently undergo selective chemical reactions to introduce new functionality without disrupting native biochemical cellular processes. These studies showcased the power of biochemical glycoengineering and subsequent chemical manipulation in whole cells. We were interested in applying these fundamental principles to bacterial PG and gathered inspiration from previous efforts to label this polymer (Figure 3): unnatural amino acids including d-amino acid fluorophores and derivatives can be incorporated using metabolic machinery, cell wall targeting antibiotics can deliver probes and proteins embedded in the cell wall can be modified to include a fluorescent dye (Daniel and Errington, 2003; Gale and Brown, 2015; Garner et al., 2011; Kocaoglu et al., 2012; Kuru et al., 2012; Lebar et al., 2014; Liechti et al., 2014; Nelson et al., 2010; Sadamoto et al., 2002; Shieh et al., 2014; Siegrist et al., 2013; Tiyanont et al., 2006). Efforts by Nishimura and colleagues revealed that the NAG unit of PG could potentially be labeled at the 2-N acetyl position in lactic acid bacteria via fluorescent microscopy analysis, but their studies did not include mass spectrometry evidence of probe incorporation (Sadamoto et al., 2008). Previous work from our lab utilized PG O-acetyltransferase B (PatB) and bioorthgonal short N-acetyl cysteamine (SNAc) donors to postsynthetically modify PG of Bacillus subtilis (Wang et al., 2017). While this work allowed us to visualize post-synthetic PG, the labile and bioreactive acetate proved challenging in generating mass spectrometry based evidence for remodeling.

Figure 3. Chemical Modifications of Bacterial PG.

Summary of PG chemical modifications with fluorophores to the peptide and carbohydrate portions of the PG polymer are highlighted in different colors.

Such methods have proven useful in studying bacterial cell wall. However, current methods that label the terminal d -Ala residues of the peptide stems are subject to removal during PG remodeling and these terminal residues are not required for immune activation (Figures 2 and 3)(Inohara et al., 2003; D’Ambrosio et al., 2019). For example, MDP and MTP (Figure 1) do not contain a d -Ala residue. Moreover, extension of the peptide decreases the ability for the fragments to activate innate immune receptors in vitro (Girardin et al., 2003). However, the label at the NAM carbohydrate level will be retained in predicted innate immune agonist structures such as MDP (Figure 2 and 3) (Inohara et al., 2003; Strominger, 2007; Girardin et al., 2003). Unfortunately, the aforementioned methods do not label on the NAM carbohydrate core of the PG polymer. To overcome this concern, we sought to install bioorthogonal functionality on the NAM carbohydrate backbone, which would increase the lifetime of the probe and allow the study of nascent polymer through metabolic labeling. d -Ala probes can be incorporated by exchange reactions in mature cell wall, as well as through a biosynthetic route complicating efforts to measure sites of de novo PG synthesis (Lebar et al., 2014). Furthermore, a NAM-based labeling strategy would allow for the selective incorporation of tag into NAM residues, which are only found in bacterial PG (Inohara et al., 2003; Strominger, 2007; Girardin et al., 2003). Therefore, a scalable and modular chemical synthesis of NAM derivatives was designed (Figure 4 and 5). These derivatives were able to be incorporated into the bacterial cell wall recycling and biosynthetic pathways to fluorescently illuminate cells via click chemistry. Here we outline the detailed protocol for key synthetic intermediates as well as utilization of the methodology (Liang et al., 2017; DeMeester et al., 2018).

Figure 4.: Synthesis of Peracetylated 2-Azido Glucosamine (1).

Figure 5.: Synthesis of 2N- functionalized NAM derivatives.

Basic Protocol 1

Synthesis of Peracetylated 2-Azido Glucosamine (1)

An optimized diazo transfer protocol which demonstrates large-scale production of peracetylated 2-azido glucosamine is outlined. Beginning with commercially available starting material Imidazole, the whole synthetic route including: acylation, selective methylation, azidolation to form the diazo transfer reagent, safely applied diazo transfer to glucosamine, and then peracetylation. The Peractylated 2-azido glucosamine is the precursor to subsequent molecule synthesis. It is advised to produce 50 grams of compound 1 before starting the following synthesis. This methodology offers minimal usage of sodium azide and a robust, safe procedure to warrant reproducible yields.

Synthesis of Sulfuryl Diimidazole (5):

Imidazole is added to a flame dried round bottom flask equipped with a stir bar and purged with N2, then the imidazole is solvated with anhydrous dichloromethane. The solution is then placed in an ice bath and cooled to 0°C. A separate solution of sulfuryl chloride diluted by anhydrous dichloromethane is created, then charged to the reaction flask via needle and syringe. The ice bath is removed, and the reaction proceeds overnight at room temperature for approximately 12 hours. Once completed, the reaction is filtered. The filtrate is collected then evaporated with a rotary evaporator. The crude product is recrystallized with isopropanol alcohol, and the product is collected through filtration.

Materials

Imidazole (Sigma)

Sulfuryl Chloride (Sigma)

Anhydrous Dichloromethane

Nitrogen Supply

Magnetic stir plate and stir bar

1 L round-bottom flask

60 ml syringe with needle

0.5 L Buchner filter

1 L vacuum Erlenmeyer filtration flask

Ice bath

Rotary Evaporator

Protocol (0.36 mol)

Add 150g (6 equiv.) of Imidazole to a 1 L flame dried round bottom flask.

Purge reaction flask with N2.

Dissolve imidazole with 650 ml of anhydrous dichloromethane.

Place reaction flask in an ice bath and cool to 0°C.

Create a separate solution of 100 ml of anhydrous dichloromethane and 30 ml (1 equiv.) of sulfuryl chloride.

Charge the reaction flask with the diluted solution of sulfuryl chloride via needle and syringe.

Remove ice bath and allow the reaction to run for approximately 12 hours.

After completion, filter the reaction through a Buchner filter and collect filtrate.

Condense filtrate with a rotary vacuum at room temperature to yield the crude product.

Recrystallize crude product with 120 mL isopropanol alcohol refluxing at 85°C a Allow precipitate to cool to room temperature and collect product via filtration.

Reaction Performed Twice

Amount Collected = 94g

Approximate Yield = 68%

Synthesis of Methylated Sulfuryl Diimidazole (6):

At 0°C, sulfuryl diimidazole can be dissolved in dichloromethane then charged with methyl triflate. Sulfuryl diimidazole should be added in excess to avoid the formation of dimethylated sulfuryl diimidazole. With adequate stirring, the reaction is completed within 2 hours and comprises an approximate quantitative yield. The product precipitates out of solution and is collected through filtration. Note: Caution should be used to ensure that all traces of dichloromethane are removed from the product (high vacuum) and removal should be confirmed by NMR before continuing the synthesis. Inadequate stirring will result in a decrease of yield. To minimize product degradation, this compound should be stored in a freezer at or below −20°C.

Materials

N, N-sulfuryl diimidazole (from above)

Methyl triflate (Sigma-Aldrich)

Anhydrous Dichloromethane

Nitrogen Source

Magnetic stir plate and stir bar

1 L round-bottom flask

60 mL syringe with needle

Ceramic filter and filter paper

1 L vacuum filtration flask

Ice Bath

Belt-Drive Vacuum Pump

Protocol (0.3 moles)

Add 72 g (1.2 equiv.) of N,N-sulfuryl diimidazole to a flame dried round bottom flask equipped with a stir bar and purge with N2.

Add 700 ml of anhydrous dichloromethane as a solvent.

Place reaction under an ice bath and cool to 0° C.

Add 34 ml (1 equiv.) of methyl triflate dropwise with a 60 mL syringe with needle over 15 mins.

Stir resulting solution adequately for 2 hours at 0° C.

Filter solution with standard filtration setup and collect the precipitate.

Dry precipitate under reduced pressure with no heat and keep dry product at 0° C.

Take HNMR to ensure all dichloromethane is removed from the product.

Store immediately in freezer (−20 °C) and purge with N2.

Amount collected = 108g

Yield = 98%

Generation and Partitioning of imidazole-1-sulfonyl azide (7):

Safety note:

The explosive and toxic nature of azides and unstable diazo transfer reagents have historically hampered the practicality of large-scale diazo transfer reactions. To abate such safety concerns and provide access to peracetylated 2-azido glucosamine in large quantities, the practice of partitioning was employed (i.e no more than 35mmol g of this material was synthesized in one reaction; in order to obtain high amounts multiple reaction products can be combined). From previously prepared methylated N,N-sulfuryldiimidazole, multiple reaction flasks can be prepared with minimal amounts of sodium azide. Each partitioned reaction is complete after 1 hour then extracted with ethyl acetate. The prepared solution of imidazole-1-sulfonyl azide can reside under ice at 0°C until readiness for diazo transfer.

The preparation of the diazo transfer reagent (imidazole-1-sulfonyl azide) begins with cooling a 1:1 solution of ethyl acetate and H2O to 0°C. 1.2 equivalence of methylated sulfuryl diimidazole can be charged to the flask followed by the addition of 1 equivalence of sodium azide. The reaction temperature must be maintained at 0° Celsius for 1 hour, otherwise, safety and the integrity of the product can be compromised. As the reaction proceeds, methyl sulfuryl diimidazole will move to the aqueous layer with the generation of imidazole-1-sulfonyl azide residing in the organic layer. Extraction of imidazole-1-sulfonyl azide can be accomplished through phase separation in a separatory funnel with cold ethyl acetate. A minimal amount of sodium sulfate is used to remove trace amounts of H2O. To ensure complete extraction, the aqueous layer should be washed once with minimal amounts of cold ethyl acetate. To prevent the risk of explosion, the organic layer should not be isolated or concentrated under reduced pressure.

Materials

Methylated sulfuryl diimidazole (from Step 9 above)

Sodium azide (Sigma)

Ethyl acetate

Deionized H20

Anhydrous sodium sulfate

Nitrogen tank

250 mL round bottom flask

Stir bar

Stir plate

250 mL separatory funnel

125 mL Erlenmeyer flask

Ice Bath

Protocol (0.035 moles)

Add 40 mL of ethyl acetate and 40 mL of deionized H2O into a 250 mL round bottom flask.

Place solution in an ice bath, and cool to 0°C.

Stir solution and add 15.5 g of methylated sulfuryl diimidazole.

With caution, slowly add 2.3 g of sodium azide to the reaction flask.

Stir resulting solution for 1 hour at 0°C.

Transfer reaction into a separatory funnel using a funnel to prevent spillage.

Separate organic layer from aqueous layer.

Back extract aqueous layer with additional 10 mL of ethyl acetate.

Collect organic layer in a 125 mL Erlenmeyer flask.

Add sodium sulfate to Erlenmeyer flask.

Place Erlenmeyer flask containing the organic layer in an ice bath until further use.

Diazo Transfer (8):

Imidazole-1-sulfonyl azide solution can be filtered directly into a reaction flask then charged with d-(+)-glucosamine hydrochloride. Methanol is added to help dissolve each reagent. To complete the diazo transfer, catalytic amounts of copper sulfate and excess potassium carbonate is transferred into the flask. The reaction runs overnight for approximately 12 hours at room temperature. Once completed, the reaction is filtered through celite and washed with methanol. To prepare for acetylation, all methanol is removed through reduced pressure.

Materials

Diazo Transfer Reagent (imidazole-1-sulfonyl azide solution from Step 9 above)

d-(+)-glucosamine hydrochloride (Sigma)

Potassium carbonate (Fisher)

Anhydrous copper sulfate (Sigma)

Anhydrous methanol

Nitrogen tank

500 mL Round bottom flask

Stir plate

Stir bar

24/40 Buchner filter

Ice Bath

Celite

Rotary Evaporator

Belt-Drive Vacuum Pump

Protocol (0.035 moles)

Filter diazo transfer reagent (Imidazole-1-Sulfonyl azide solution from previous step 9) directly into a flame dried 500 mL round bottom flask.

Purge reaction flask with nitrogen gas and place in an ice bath.

Stir reaction solution at 0° C and add 9.14 g (1.2 equiv.) of d -(+)-glucosamine hydrochloride.

Add 100 mL of anhydrous methanol to help dissolve both reagents.

Add 0.22g (0.04 equiv.) of copper sulfate.

Add 8.83g (1.8 equiv.) of potassium carbonate to the flask.

Remove the ice bath and allow the reaction to stir overnight at room temperature approximately 12 hours.

Filter reaction through a thin layer of celite, and wash with additional methanol.

Evaporate the filtrate with a rotary evaporator apparatus to dryness.

Dry crude product under reduced pressure from a Belt-Drive Vacuum Pump which removes additional methanol.

Store crude product in a 1L round bottom flask to prep for peracetylation.

Peracetylation (1):

Crude 2-azido glucosamine is solvated with pyridine. A solution of DMAP and acetic anhydride is created separately, then slowly charged to the reaction flask via needle and syringe. To discourage excessive exothermic heat released, the reaction flask is placed under ice while the reaction flask is being charged. The reaction runs at room temperature for approximately 12 hours. Reaction work up includes phase separation with 1 M HCl, brine, and extraction with ethyl acetate. Product is purified through column chromatography. Note: solvation of crude 2-azido glucosamine is not immediate and will progress as reaction proceeds.

Materials

Crude 2-azido glucosamine (from Step 11 above)

Anhydrous pyridine (Sigma)

4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP) (Sigma)

Acetic anhydride (Sigma)

1M Hydrochloric acid (HCl)

Stir bar

Stir plate

Ice bath

1 L round-bottom flask

250 mL round-bottom flask

60 mL syringe with needle

Rotary Evaporator

1L Column (2.5inch D, 18inch L)

Silica gel

Protocol (0.210 moles)

Add 390 mL of anhydrous pyridine directly into a 1L round bottom flask containing crude 2-azido glucosamine.

Place flask in an ice bath.

Add 161 mL of acetic anhydride (8 equiv.) and 2.6g DMAP (0.1 equiv.) to a 250ml round bottom flask and stir the solution.

Transfer solution of DMAP and acetic anhydride slowly using a 60mL syringe with a needle to the 1L round bottom flask containing 2-azido glucosamine.

Remove ice bath.

Stir reaction at room temperature overnight for approximately 12 hours.

Dilute reaction with ethyl acetate (~ 500 mL), and transfer into a 2 L separatory funnel.

Wash organic layer with 1 M HCl until all excess pyridine has been protonated and removed from the organic layer. to remove excess pyridine.

Add brine if phase separation is lost and emulsions form.

Collect organic layer (ethyl acetate) and concentrate on a rotary evaporator.

Load crude product onto silica gel column.

Column proceeds with a 5% incremental gradient of eluent from 0%−30% ethyl acetate in hexanes, yield 63% over steps 7–9. Fully protected glucosamine sugar serves as the glycan source for compounds 2 and 3 used to metabolically label the muramic acid sugars in bacterial peptidoglycan.

Basic Protocol 2:

Synthesis of 2-azido NAM (2) and 2-alkyne NAM (3) )

With the diazo transfer protocol complete, classic carbohydrate protection and deprotection strategies are implemented followed by installation of (S)-2- chloropropionic acid, generating the protected 2 amino muramic acid (Figure 5). Subsequent hydrogenation conditions followed by preparatory HPLC yield the deprotected 2 amino muramic acid (10) which is then poised to undergo NHS coupling chemistry to install either the azide or alkyne N-acetyl functionality. The final sugar compounds can be readily purified through preparatory HPLC, however we note here that final bioorthogonal compounds simply purified through a Maxi-Clean™ SPE C18 plug are still able to undergo bacterial cell wall remodeling.

Materials:

Protected 2-amino muramic acid (Liang, et al 2017, compound 9)

Water

Methanol

Acetic acid

Palladium/Carbon (10% wt) (Sigma)

Celite

Hydrogen gas

Acetonitrile

Formic acid (Sigma)

2,5-dioxopyrrolidin-1-yl 2-azidoacetate (Sigma or Liang et al 2017)

4-pentynoic acid (Sigma, NHS activated in Liang et al 2017)

N hydroxysuccinimide (Sigma)

1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (Sigma)

N-N- dimethylformamide

Diethyl Ether

Sodium carbonate

Stir bar

Stir plate

Vacuum adaptor

500mL round-bottom flask

Filter funnel

Tygon Tubing

Straight vacuum inlet adaptor

10 mL round-bottom flask

60 mL syringe with needle

Rotary Evaporator

Waters prepatory HPLC

Maxi-Clean™ SPE 900mg C18 (Grace)

Rotory Evaporator

Lyopholizer

Synthesis of 2- amino muramic acid (10).

Produce 1 gram of compound 9 as described in the following reference (Liang et al 2017) before step 2.

Suspend intermediate 9 (0.987 g, 2.17 mmol, 1.0 eq) in a solution of 62 mL H2O, 46 mL MeOH and 7.7 mL AcOH under N2 using a straight vacuum inlet adaptor.

Attach a double wrapped balloon to vacuum tubing via Teflon tape and parafilm.

Fill the balloon with H2 gas and clip closed.

Add Pd/C (0.950 g) to the reaction under N2 to ensure no sparking.

Replace the nitrogen hose with the hydrogen balloon tubing, and unclip the balloon to introduce the hydrogen atmosphere.

Stir the reaction at room temperature under H2 for 16 hours.

Confirm product formation with LC/MS ESI pos m/z (M+H) 252.

Clip the H2 balloon, and remove the tubing.

Place reaction back under nitrogen. Carefully release hydrogen gas into the hood.

Transfer the reaction to a filter funnel packed with half an inch of celite. Filter under slow vacuum pull (do not let palladium dry). Wash filter with copious amounts of water.

Concentrate the filtrate using a rotary evaporator and dry on the high vacuum.

Dissolve product in water to make a 50mg/mL solution for preparative HPLC.

Purify product using reverse phase chromatography 0.1% formic acid (50mg/mL), and purify on the Waters preparative HPLC/MS with the method as follows: flow rate 20 mL/min, 0.1% formic acid in Millipore H2O as eluent A and 0.1% formic acid in HPLC grade acetonitrile as eluent B. Inlet file (A/B): 0–2 min 95/5, 2.5 min 20/80, 3–4 min 95/5. The product was collected based on [M+H]+ 252 with a retention time between 1.5–2.25 min.

Combine appropriate fractions and lyophilize to give a white powder (0.350 g, 65% yield,).

Synthesis of 2-azido NAM (2)

Produce 200 mg of NHS activated 2,5-dioxopyrrolidin-1-yl 2-azidoacetate as described in the following reference (Liang et al 2017) before step 2.

Add sodium carbonate Na2CO3 (0.250 g, 2.36 mmol, 6.7 eq) to a 25 mL round bottom flask.

Add 8 mL of anhydrous MeOH to the flask. Charge with N2.

Add 2-amino muramic acid (10) (0.089 g, 0.35 mmol, 1.0 eq) to the flask.

Divide NHS activated 2,5-dioxopyrrolidin-1-yl 2-azidoacetate (0.186 g, 0.94 mmol, 2.7 eq) into 5 portions. Add one portion to the reaction flask every 15 minutes in order to ensure NHS-activated compound reacts with only the amine.

Stir the reaction for a total of 2 hours under N2.

Monitor reaction by TLC (25% MeOH/EtOAc) and LC/MS ESI neg [M-1]- = 333.

Once complete, filter reaction, and evaporate under reduced pressure without heat.

Purify the off-white solid on the Waters preparative HPLC/MS. Dissolve crude oil in DI H2O 0.1% formic acid (50 mg/mL) and purify on the Waters preparative HPLC/MS with the method as follows: flow rate 20 mL/min, 0.1% formic acid in Millipure H2O as eluent A and 0.1% formic acid in HPLC grade acetonitrile as eluent B. Inlet file (A/B): 0 min 95/5, 4 min 5/95, 4.5 min 5/95 and 4.8–5 min 95/5. The product was collected based on [M-H]- ESI neg 333.2 with a retention time between 1.25–1.75 min.

Combine the appropriate fractions, and lyophilize to give an off white crystalline solid (0.073 g, 63% yield).

Synthesis of 2-alkyne N- acetyl muramic acid (3)

Produce 50 mg of NHS activated of 4-pentynoic acid as described in the following reference (Liang et al 2017) before step 2.

Add sodium carbonate Na2CO3 (0.0566 g, 0.534 mmol, 6.7 eq) to a 10 mL round bottom flask.

Add 1.1 mL of anhydrous MeOH under N2.

Add 2 amino muramic acid (0.020 g, 0.080 mmol, 1.0 eq) to the flask.

Divide NHS activated 4-pentynoic acid (0.0417 g, 0.214 mmol, 2.7 eq) into five portions. Add one portion to the reaction flask every 15 minutes.

Monitor reaction by TLC (25% MeOH/EtOAc) and LC/MS.

Once complete, filter the reaction and evaporate under reduced pressure without heat.

Purify the off-white solid on the Waters preparative HPLC/MS with the following method: Crude product was dissolved in either methanol or water as a 50 mg/mL solution and purified on the Waters preparative HPLC/MS with the method as follows: flow rate 20 mL/min, 0.1% formic acid in Millipure H2O as eluent A and 0.1% formic acid in HPLC grade acetonitrile as eluent B. Inlet file (A/B): 0 min 95/5, 4 min 5/95, 4.5 min 5/95 and 4.8–5 min 95/5. Collect the product based on [M-H]- ESI neg 330.2 with a retention time between 1.50–1.80 min.

Combine the appropriate fractions and lyophilize to give an off white crystalline solid (15.7 mg, 62% yield).

Basic Protocol 3

Synthesis of 3-azido NAM methyl ester (4)

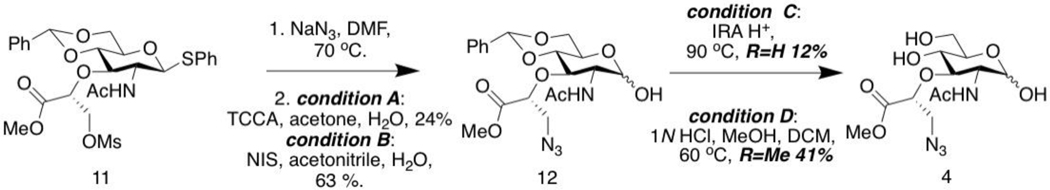

Functionality beyond the 2-N position was desired, as modifications at this moiety may be lost due to natural modifications of select bacteria such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB). In order to expand the probe utility to multiple organisms, we sought to install functionality onto the lactic acid portion of the NAM residue. Classic carbohydrate protection strategies implemented followed by the installation of the modified (S)-2-Chloropropionic acid to generate the protected 3-hydroxyl NAM, 16 (Figure 6). As previously reported, an elimination side reaction occurs during the construction of the azido group (DeMeester et al., 2018) and this product mixture directly processed to the next step without separation. By changing the order of deprotection of the C-1 position under classic or mild oxidation conditions, we are able to more readily separate and purify compound 18 through flash column chromatography (Figure 6, condition A or B, respectively). Selective deprotection of the 4,6-benzylidene now follows the C-1 deprotection under condition A to result in global deprotection rendering the carboxylic acid derivative 19 in comparable yields to those previously reported (DeMeester et al., 2018). However, to optimize these reaction conditions and yields for a more scalable process, a methyl ester form of the 3-azido modification was achieved in this protocol under optimized condition B via 1N HCl, MeOH and DCM. This methodology affords a much higher and stable yield compared to the acid form. The final sugar compounds can be readily purified through preparatory HPLC; however, we note here that final bioorthogonal compounds simply purified through a Maxi-Clean™ SPE C18 plug are still able to undergo bacterial cell wall remodeling (Figure 4). The methyl ester in compound 19 has the ability to be removed in the cell during metabolic PG incorporation by abundant esterases to yield the final 3-azido NAM.

Figure 6. Synthesis of 3-azido NAM methyl ester.

Materials:

Intermediate 17 (DeMeester et. al, 2018)

Sodium Azide (NaN3) (Sigma)

N,N-Dimethylformamide anhydrous (DMF)

Deionized Water

Methanol

Dichloromethane

Acetonitrile

N-Iodosuccinimide (Sigma)

Sodium thiosulfate (Na2S2O3)

Brine

Ethyl acetate

Sodium sulfate anhydrous (Na2SO4)

1N HCl solution

Stir bar

Stir plate

Straight vacuum inlet adaptor

100 mL round-bottom flask

50 mL round-bottom flask

Filter funnel

Air condenser

100 mL separatory funnel

Rotary Evaporator

Silica gel

Silicone oil bath

Waters preparative HPLC

Maxi-Clean™ SPE 900mg C18 (Grace)

Lyophilizer

Synthesis of 3-azido NAM methyl ester with 4,6-benzylidene protected (12).

Produce 700 mg of intermediate 11 as described in the following reference (DeMeester et al., 2018) before step 2.

Add intermediate 11 (638 mg, 1.1 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) into a 100 mL round-bottom flask with an air condenser.

Add NaN3 (715 mg, 11 mmol, 10 equiv.) and 10 mL DMF anhydrous into the flask with a stir bar.

Put the flask into a 70 °C oil bath and stir for 5 hours.

Monitor reaction by TLC (10% Methanol/Dichloromethane) and LC/MS ESI pos [M+1]+= 528.5.

Once complete, cool the reaction to room temperature add 60 mL water until the white solid formation ceases.

Collect the white solid by vacuum filtration. Directly use this crude product for the next step without purification.

Add the previous crude product into a 100 mL round-bottom flask under N2 using a straight vacuum inlet adaptor.

Add 50 mL acetonitrile and 5 mL DI H2O into the flask with a stir bar.

Put the flask to ice-water bath to cool to 0 °C for 30 minutes, then add N-Iodosuccinimide (554 mg, 2.46 mmol, 2.24 equiv.).

Remove the ice-water bath after 30 minutes.

Stir the reaction for a total of 48 hours at room temperature.

Monitor reaction by TLC (10% Methanol/Dichloromethane) and LC/MS ESI pos [M+1]+= 437.

Once complete, add 5 mL 10% Na2S2O3 aqueous solution until the reaction solution become colorless.

Transfer 10 mL ethyl acetate into the flask and add the reaction solution into a separatory funnel, shake it to mix and collect the organic layer. Repeat this procedure for 3 times.

Combine all the organic layers (ethyl acetate). Add 10 mL Brine to wash the organic layer.

Add Na2SO4 anhydrous into the organic layer, filter and evaporate under reduced pressure.

Dry pack the off white solid and purify it by a silica gel column using 2% Methanol/Dichloromethane. Collect the product based on TLC (10% Methanol/Dichloromethane) with Retention Factor (Rf) 0.6.

Combine the appropriate fractions and concentrate to give an off white solid (302 mg, 63% yield).

Synthesis of 3-azido NAM methyl ester (4).

Add intermediate 12 (180 mg, 0.412 mmol) into a 50 mL round-bottom flask under N2 using a straight vacuum inlet adaptor.

Add 14.4 mL methanol and 2.7 mL Dichloromethane into the flask with a stir bar.

Add 450 μL 1N HCl solution.

Put the flask into a silicone oil bath with an air condenser. Heat the oil bath to 60 °C.

After 8 hours, monitor the reaction by LC/MS ESI pos [M+1]+=349.

Once complete, evaporate most of the solvent under reduced pressure without heat.

The crude product was purified by passing Maxi-Clean™ SPE C18 column with 0.1% formic acid.

Purify the off-white solid on the Waters preparative HPLC/MS with the following method: Crude product was dissolved in water as a 50mg/mL solution and purified on the Waters preparative HPLC/MS with the method as follows: flow rate 20 mL/min, 0.1% formic acid in Millipore H2O as eluent A and 0.1% formic acid in HPLC grade acetonitrile as eluent B. Inlet file (A/B): 0 min 95/5, 4 min 5/95, 4.5 min 5/95 and 4.8–5 min 95/5. Collect the product based on [M+Na]+ ESI pos 371.19.

Combine the appropriate fractions and lyophilize to give an off white crystalline solid (58 mg, 41% yield) (Figure 7).

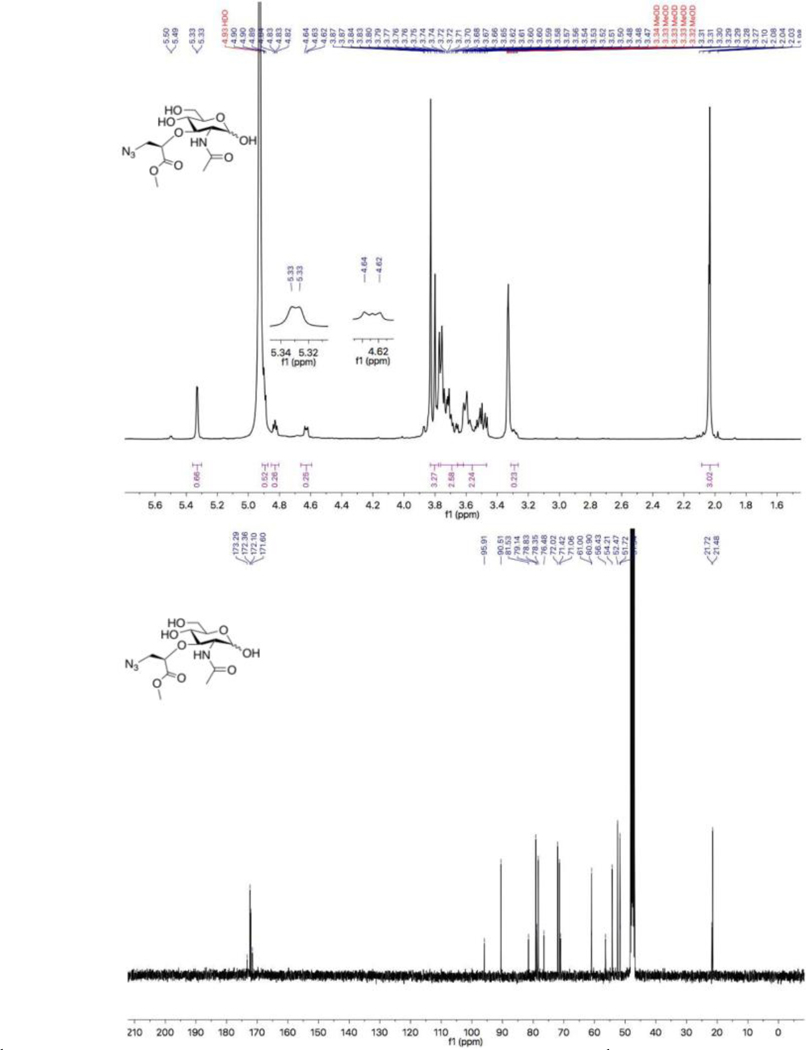

Figure 7.

A) 1HNM spectra of 3-azido NAM methyl ester: 1H NMR (400 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 5.33 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H, α-H1), 4.91 – 4.88 (m, 1H, α-CHCH2CH3), 4.83 (dd, J = 5.2, 3.8 Hz, β-CHCH2CH3), 4.66 – 4.59 (m, β-H1, anomeric ratio α/β=2.57), 3.83 (s, 3H, α-CH3O), 3.80 (s, β-CH3O), 3.77 – 3.65 (m, α and β-C6, α-C2, α-C4 and α-C3), 3.62–3.47(m, α and β-CHCH2N3, β-C2, β-C4, β-C5 and β-C3), 3.31–3.27 (m, α-C5), 2.04 (double singlet, α and β-CH3C(O)NH); B)13C NMR spectra: 13C NMR (101 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 173.29, 172.36, 172.10, 171.60 (carbonyls), 95.91 (β-C1), 90.51 (α-C1), 81.53 (β-C3), 79.14 (α-CHCH2N3), 78.83 (β-CHCH2N3), 78.35 (α-C3), 76.48 (α-C5), 72.02 (β-C5), 71.42 (α-C4), 71.06 (β-C4), 61.00 (β-C6), 60.90 (α-C6), 56.43 (β-C2), 54.21 (α-C2, 52.47 (α and β-CHCH2N3), 51.72 (α-CH3O), 51.54 (β-CH3O), 21.72 (β-CH3C(O)NH), 21.48 (α-CH3C(O)NH).

Basic Protocol 4

Incorporation of NAM Probes into E.coli Bacterial Peptidoglycan

Recycling enzymes AmgK and MurU are introduced to construct E. coli ΔMurQ-KU cells, which can express AmgK and MurU enzymes and therefore recycle NAM derivates into mature PG (Liang et. al, 2017). Under the lethal concentration of fosfomycin, an antibiotic drug that can selectively inhibit the MurA enzyme (Kahan, 1974), E. coli ΔMurQ-KU cells are unable to grow due to the inhibition of natural biosynthesis of UDP-MurNAc. Cell growth of E. coli ΔMurQ-KU can be restored in the presence of fosfomycin when cells are provided with an alternative way to synthesize UDP-MurNAc via the AmgK/MurU pathway and supplemented with the NAM sugars.

To visualize PG, cells are grown in an optimized amount of the NAM derivatives (3–6 mM with the selection condition described above). After incubation, a subsequent Copper (I)-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition, also known as a ‘click’ reaction, is performed to introduce a fluorophore into the remodeled PG polymer. Cells supplemented with the NAM probes (NAM or AzNAMs) are successfully labeled with the corresponding alkyne fluorophore Rhodamine 110 (Alk488) and are visualized through fluorescence microscopy like confocal or structured illumination microscopy (SIM).

Materials

Stock solutions of sugars (0.1 M of NAM, 2-AzNAM, 2-AlkNAM, or 3-AzNAM in Milli-Q® water)

E. coli ΔMurQ-KU cells (see Liang, et. al 2017 2017 for strain construction; for access to strain, contact corresponding author)

Petri Dishes with Clear Lid (Fisher- Catalog ID FB0875712)

Isopropyl-1-thio-β-D-galactoside (IPTG) (Gold Biotechnology-Catalog ID I2481) Lysogeny broth (LB)

Bacto Agar (Fisher)

Chloramphenicol (34 mg/mL stock in Milli-Q® water) (Gold Biotechnology-Catalog ID C-105)

Kanamycin (50 mg/mL stock in Milli-Q® water) (Gold Biotechnology-Catalog ID K-120)

Fosfomycin (10 mg/mL in Milli-Q® water) (Gold Biotechnology- Catalog ID F-470)

1 x Phosphate buffered saline (PBS)

Copper sulfate (CuSO4) (Fisher)

Freshly prepared (+)− sodium (L) ascorbate (Fisher)

Tris[(1-benzyl-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl]amine (TBTA) (Sigma)

Fluor 488-Alkyne (Sigma- Catalog ID61621)

Poly-L-lysine (Sigma)

Milli-Q® water

Cover glasses (Zeiss)

1.5 mL sterile Eppendorf tubes

Prolong Diamond Antifade Mountant (Invitrogen)

Sterile culture tubes

37 °C incubator

Zeiss Elyra PS.1 microscope with Plan-Apochromat × 63/1.4 Oil differential interference contrast (DIC) M27 objective

Plate shaker

UV/Vis Spectrophotometer

Tweezers

Preparation of Stock Bacterial Plate

1. In a 500 mL flask, add 200 mL of Milli-Q® water, 5 g of lysogeny broth, and 4 g of Bacto Agar

2. Stir flask at room temperature until contents are fully dissolved

3. Autoclave flask on liquid cycle.

4. Remove flask from autoclave, and allow to cool down until temperature reaches around 60 °C.

5. With a flame on, add 200 μL of Kanamycin (50 mg/mL stock) and 200 μL Chloramphenicol (34 mg/mL stock) to the flask. Mix well by rotating gently.

6. Pour the contents of the flask on to sterile 10 cm x 10 cm plastic dishes until the medium covers the bottom of the plate. Allow plates to harden at room temperature.

7. Dip spreader in culture of E. coli ΔMurQ-KU and streak in a zig-zag pattern across the entirety of the plate.

8. Place plate in 37 °C plate incubator overnight.

9. Remove plate from incubator, parafilm, and store at 4°C.

Bacterial Growth

10. With a flame on, add 7 mL of autoclaved LB media into an autoclaved glass culture tube.

11. Add 7 μL of Kanamycin (50 mg/mL stock) to the culture tube.

12. Add 7 μL of Chloramphenicol (34 mg/mL stock) to the culture tube.

13. Pick a colony of E. coli ΔMurQ-KU cells grown on a Kanamycin (50 μg/mL)/Chloramphenicol (24 μg/mL final concentration) agar plate. Place colony into LB media. Shake overnight in a 37 °C incubator.

14. Repeat steps 1–3 to prepare fresh media for inoculation.

15. Add 200 μL of the overnight E. coli ΔMurQ-KU cells into the tube containing the media from Step 12.

16. Transfer 50 μL of freshly prepared cell culture into a cuvette.

17. Measure the OD600 using UV-Vis spectrophotometer. Prepare blank using 50 μL of fresh LB. OD600 should be around 0.200. If not, go back and add more of the overnight until OD is 0.200.

18. Incubate cells at 37 °C incubator while shaking at 200 rpm until OD600 reaches 0.600.

-

○

If starting OD600 is around 0.200, it should take about 45–60 mins to reach desired OD.

19. Transfer 1.2 mL of cells into a sterile 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube. Repeat this for each experimental condition.

20. Centrifuge tubes using a benchtop centrifuge at 8,000 rpm for 5 min at room temperature.

Bioorthogonal Cell Labeling Procedures

21. With a flame on, carefully remove supernatant with 1 mL pipette without disturbing the cell pellet.

22. Resuspend pellet in 200 μL of autoclaved LB.

23. Add 4 μL of Fosfomycin (10 mg/mL stock) to the cells.

24. Add 2 μL of IPTG (0.1 M stock IPTG in water) to the cells.

25. Add 12 μL of the 0.1 M NAM sugar stocks (NAM used as a control; 2-AzNAM or 2AlkNAM is typically used for labeling purposes with E. coli ΔMurQ-KU, but if using a species of bacteria that has enzymes known to modify the 2-position on the sugar, 3-AzNAM is the preferred sugar substrate)

26. Incubate cells at 37 °C incubator while shaking at 200 rpm for 45 minutes.

27. Centrifuge cells at 10,000 rpm for 2 min at room temperature.

28. Remove supernatant and discard.

29. Resuspend pellet in 600 μL of 1X PBS.

30. Pipette up and down 20 times to wash, blowing against the back wall of the tube.

31. Spin cells at 10,000 rpm for 2 min at room temperature.

32. Repeat steps 28–31.

33. Remove supernatant and discard.

34. Resuspend cells in 200 μL of 1:2 tert-butanol:water solution to prepare for the click reaction.

35. Add 4 μL of CuSO4 (50 mM stock) to the cells.

36. Add 4 μL of Tris[(1-benzyl-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl]amine (TBTA) to the cells.

37. Add 4 μL of freshly prepared (+)- sodium (L) ascorbate (12 mg/mL stock) to the cells.

38. Add 0.5 μL of Fluor 488-Alkyne (1 mM stock in water).

39. Pipette up and down 3x gently to mix.

40. Incubate cells at room temperature on a shaker for 30 min in the dark.

41. Centrifuge cells at 10,000 rpm for 2 min at room temperature.

42. Remove supernatant and discard.

43. Resuspend the cells in 600 μL of 1 x PBS to wash. Pipette up and down ~30 times as earlier described.

44. Spin 10,000 rpm for 2 min at room temperature. Repeat step 42 to wash cells with 600 μL PBS and once with 200 μL of PBS.

45. Remove supernatant, and discard.

46. Resuspend in 200 μL of 1x PBS. Let sit at room temperature in the dark for 30 min.

47. Centrifuge cells at 10,000 rpm for 2 min at room temperature.

48. Remove supernatant and discard.

49. Resuspend the cells in 200 μL of 1 x PBS for final wash. Centrifuge cells at 10,000 rpm for 2 min at room temperature.

50. Resuspend the cells in 100 μL 1x PBS to prepare for microscopy.

Microscopy Preparation

51. Add 200 μL of 0.1 mg/mL poly-L-lysine to the center of each coverglasses (Zeiss), and let sit for 2 hours at room temperature.

52. Remove poly-L-lysine, and wash the coverglasses with 500 μL of deionized (DI) water. Tap excess water on kim-wipe and Let the cover slip air dry at room temperature.

53. Add 15 μL of the labeled cells from step 49 to the center of the coverglass and spread around the coverglass using a plastic pipette tip. Extra cells can be stored in PBS at 4°C for short term up to 1 week, or in PBS:glycerol 75:25 at −20 for long term storage.

54. Incubate coverglass at room temperature for at least 30 mins to allow cell adherence in the dark.

55. Remove extra cells solution by pipetting excess liquid off of the slide.

56. Add 5 μL of Prolong Diamond Antifade Mountant to glass slide. Using tweezers, invert coverglasses and lay onto glass slide. Use tweezers to carefully push down on slide to remove any air bubbles.

57. Incubate slides overnight at room temperature in the dark. Seal edges of coverglasses with clear nail polish.

Structured illumination microscopy (SIM)

58. Place slide on Zeiss Elyra PS.1 microscope with Plan-Apochromat × 63/1.4 Oil differential interference contrast (DIC) M27 objective.

59. Use laser excitation of 488 to visualize Alk488.

60. Set camera exposure to 100.0 ms.

61. Set z-stack interval to 0.110 μm and ensure raw data has 5 rotations.

62. Reconstruct raw data with Carl Zeiss ZEN 2012 structured illumination processing, keeping processing and filtering setting constant and preserving image intensity by selecting raw image scale option.

63. Generate two-dimensional and three-dimensional images as desired (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Structured illumination microscopy images of cells treated with 2 AzNAM filtered with Waters preparative HPLC/MS or with Maxi-Clean™ SPE C18 plug and clicked with AF-Alk488 (white) (scale bars, 5 μM). Images are representative of a minimum of five fields of view per replicate with at least three technical and biological replicates.

Basic Protocol 5

Mass spectrometry bacterial cell wall remodeling confirmation

To enhance selectivity for PG probe incorporation, fosfomycin antibiotic selection of the E. coli ΔMurQ-KU cells is utilized. Fosfomycin inhibits MurA (Figure 2) from converting UDP NAG into UDP NAM, limiting the uptake of the NAM biorthogonal probe to the recycling pathway. Therefore, the only known NAM source for the bacteria to build their new PG must come from the substrates supplemented to the cells. However, in order to definitively show that the NAM probes are embedded in the PG polymer as suggested, a method to digest and characterize smaller PG fragments is used. As previously described, E. coli ΔMurQ-KU cell growth can be restored and sustained in the presence of a lethal dose of fosfomycin and the NAM probes. E. coli ΔMurQ-KU cells are labeled with the NAM probes and treated with the cell wall digestive enzyme lysozyme. This enzyme is known to specifically degrade PG into distinct disaccharide carbohydrates, and evidence of biorthogonal NAM incorporation in the bacterial cell wall can be observed via high resolution liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (HRLCMS).

Materials

E. coli ΔMurQ-KU cells(see Liang, et. al 2017 for strain construction; for access to strain, contact corresponding author)

1 × PBS

Petri Dishes with Clear Lid (Fisher- Catalog ID FB0875712)

Milli-Q® water Sodium chloride (NaCl)

Tris pH 7.9

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) pH 7.9

Lysozyme from chicken egg (Sigma)

Amicon Ultra 3K Filter Devices

0.1% formic acid in HPLC grade water

0.1% formic acid in HPLC grade acetonitrile

Digestion Buffer (See reagents and solutions)

Acquity UPLC BEH C18 column 2.1 × 50 mm (Waters)

Dionex UHPLC coupled to a Q-Exactive Orbitrap (Thermo Fisher Scientific)

Thermo Xcalibur Qual Browser

Method

In a 500 mL flask, add 200 mL of Milli-Q® water, 5 g of lysogeny broth, and 4 g of Bacto Agar.

Stir flask at room temperature until contents are fully dissolved.

Autoclave flask on liquid cycle.

With a flame on, add 200 μL of Kanamycin (50 mg/mL stock) and 200 Chloramphenicol (34 mg/mL stock) to the flask.

Pour the contents of the flask on to sterile 10 cm x 10 cm plastic dishes. Allow plates to harden at room temperature.

Dip spreader in culture of E. coli ΔMurQ-KU and streak in a zig-zag pattern across the entirety of the plate.

Place plate in 37 °C plate incubator overnight.

Remove plate from incubator, parafilm, and store at 4°C.

With a flame on, add 7 mL of autoclaved LB media into an autoclaved glass culture tube.

Add 7 μL of Kanamycin (50 mg/mL stock) to the culture tube.

Add 7 μL of Chloremphenicol (34 mg/mL stock) to the culture tube.

Pick a colony of E. coli ΔMurQ-KU cells grown on a Kanamycin (50ug/mL)/Chloramphenicol (24 μg/mL final concentration) agar plate. Place colony into LB media. Shake overnight in a 37 °C incubator.

With flame on, add 33.3 mL of autoclaved LB media into a sterile 50 mL conical tube.

Add 33.3 μL of Kanamycin (50 mg/mL stock) to the culture tube.

Add 33.3 μL of Chloremphenicol (34 mg/mL stock) to the culture tube.

Add 1 mL of the overnight E. coli ΔMurQ-KU cells into the tube.

Remove 50 μL of freshly inoculated cells and add to cuvette.

Measure the OD600 using UV-Vis spectrophotometer. Prepare blank using 50 μL of fresh LB. OD600 should be around 0.200. If not, go back and add 100 μL of the overnight until OD600 is 0.200.

-

Incubate cells at 37 °C while shaking at 200 rpm until OD600 is about 0.600.

If starting OD600 is around 0.200, it should take about 45–60 mins to reach desired OD.

Centrifuge tubes at 3000g for 5 min at room temperature.

Carefully remove supernatant without disturbing the cell pellet and discard.

Resuspend pellet in 10 mL of LB.

Add 200 μL of the 0.1M NAM sugar stocks (NAM, 2-AzNAM, 2Alk-NAM, or 3-AzNAM), 20 μL of Fosfomycin (100 mg/mL stock), and 20 μL of 1M IPTG.

Incubate cells at 37 °C while shaking at 200 rpm for 45 minutes.

Centrifuge cells at 3000g for 5 min.

Resuspend pellet in 10 mL of 1xPBS to wash, and centrifuge at 3000g for 5 min at room temperature. Repeat once.

Resuspend pellet in 2.5 mL of digestion buffer (see reagents and solutions section).

Add 20 μL of freshly prepared lysozyme (50 mg/ml stock in water) to each sample.

Shake samples in 37 °C incubator for 3 days while adding 20 μL of freshly prepared lysozyme approximately every 12 hours.

Centrifuge samples for 5 seconds, and add sample to Amicon Ultra 3K Filter Devices.

Spin sample to filter at 3000g for 30 min, collect flowthrough, freeze, and lyophilize overnight.

-

Dissolve lyophilized sample in minimal amount of DI water (20 μL) and load onto an Acquity UPLC BEH C18 column 2.1 × 50 mm (Waters) using a Dionex UHPLC coupled to a Q-Exactive Orbitrap (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Elute with following gradient:

0.5 ml min−1 linear gradient starting from 0% A to 50% B in 4 min.

Eluent A was 0.1% formic acid in water

Eluent B was 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile.

The absorbance of the eluting peaks was measured at 505 nm and further subjected high-resolution mass analysis on the Q-Exactive.

All data were processed and analyzed on a Thermo Xcalibur Qual Browser. (Figure 9).

Analyze data for lysozyme product peaks. Product peaks are disaccharide fragments with various number of amino acids in the chain off of the 3-position. Two examples are drawn out in Figure 9. Peaks are confirmed by observing the proper isotope pattern with the observed mass within +/− 10 ppm of the expected mass over multiple trials of digestion.

Figure 9. Mass spectrometry verification of 3AzNAM incorporation into bacterial PG by lysozyme digestion.

Overall experimental strategy to identify fluorescent PG fragments in E. coli ΔMurQ KU cells remodeled with 3AzNAM methyl ester. Two of the potential lysozyme fragments from the digestion are shown as A and B. Mass spectrometry results are shown for fragment A. Peaks are confirmed by observing the proper isotope pattern with the observed mass within +/− 10 ppm of the expected mass over two technical replicates of 2 biological replicates.

Reagents and Solutions:

Digestion buffer (250 μL of 1M Tris pH 7.9, 25 μL of 5M NaCl, 20 μL of 0.5M EDTA, and 4.75 mL of DI water for 5 mL solution)

Commentary

Background Information:

PG degradation research has shown that during bacterial cell growth a large portion of these degrading intermediates will be reutilized. This cell wall turnover phenomenon was discovered in the early 1960s by Říhová L. and coworkers, and since the activity of cell wall degradation has been discovered from a variety of both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria including Escherichia coli (E. coli) (Chaloupka et al., 2008, 1962; Doyle et al., 1988; Park and Uehara, 2008). Using radio labeled PG from E. coli, Goodell and Schwarz calculated the percentage of PG that is lost during each generation and identified the intermediate molecules from the cell medium (Goodell and Schwarz, 1985; Goodell, 1985). All these findings led to the theory that bacterial PG fragments will be recycled during cell growth and division. It was proposed that E. coli can reutilize about 50% of its PG polymer within one generation (Johnson et al., 2013; Jacobs et al., 1994). Interestingly, the Mayer lab showed some bacteria species can utilize NAG or NAM sugar to build PG in a more direct and efficient way with two newly discovered recycling enzymes (Gisin et al., 2013). Anomeric NAM/NAG kinase (AmgK) converts NAM into MurNAc 1-phosphate, which is then converted to UDP-MurNAc by MurNAc α-1-phosphate uridylyl transferase (MurU) (Gisin et al., 2013). These two recycling enzymes are absent in E. coli but present in many bacterial species including Pseudomonas putida (P. putida) (Gisin et al., 2013). This cell wall recycling shortcut provides another route which bypasses the PG de novo biosynthesis to synthesize UDP-NAM with NAM as the building block. The functionality of these two enzymes provides an effective method to deliver NAM to the bacterial PG.

Critical Parameters:

Diazo Transfer

The installation of azides as protecting groups is a powerful tool in carbohydrate chemistry and unlocks the ability to install late stage amine functionalization onto the small molecules. While these amines can serve as handles for subsequent chemistry and functional group installation via amide bond coupling, safety concerns are present during the installation step of the azide. The literature shows that diazotransfer via an in situ generated imidazole-1-sulfonyl azide onto glucosamine is achievable. In order to adhere to these safety measures while achieving desired starting material quantities in our laboratory, this intermediate should be partitioned between ethyl acetate and water and the organic layer distributed into multiple reaction flasks. The aqueous layer should be washed once with minimal amounts of ethyl acetate, and the organic layer should not be isolated or concentrated under reduced pressure. The use of dichloromethane is prohibited in these steps. This diazotransfer methodology ensures that the reaction can be prepared with minimal amounts of sodium azide while still providing a method to combine manageable and safe quantities in the subsequent acetylation step to large scale 2-azido glucosamine.

Performing the PG cell labeling

It is recommended to perform a concentration gradient screen for the NAM probe being utilized when you start labeling a new bacterial organism. The concentration of NAM probe utilized for E. coli labeling is 6 mM, but a concentration as low as 3 mM can be used for labeling applications (Liang et al 2017). To ensure incorporation of the NAM probe into the bacterial cell wall, the mass spectrometry validation method for incorporation is strongly recommended, especially for new organisms being labeled.

When performing the click reaction, ensure preparation of fresh sodium ascorbate right before usage. Utilizing a stored stock of sodium ascorbate will result in poor labeling. The click reaction using TBTA is recommended to be performed in 1:2 tert-butanol: water to maximize TBTA solubility water.

Troubleshooting:

Formation of methyl ester can occur if the 2-amino NAM compound 10 is heated (Basic Protocol 2). If you observe formation of methyl ester, switch to a different hydrogenation solvent system that does not utilize methanol such as THF or dioxane. Ensure the 2- amino compound is pure before doing the NHS coupling or it could result in low yields. Additionally, add sodium carbonate first to the NHS coupling reaction for higher yields.

In Basic Protocol 3, a low yield of compound 18 can result from too much Na2S2O3 or from heating the reaction, which leads to reduction byproduct. To solve this problem, add 10% Na2S2O3 aqueous solution until the reaction solution turns colorless. Separate the organic layer before rotavapping the solution. A low yield of compound 19 can result from Methyl-1 NAM byproduct formation. In this case, avoid using methanol as a solvent.

Troubleshooting advice for Basic Protocol 4 can be found in Table 1.

Table 1:

Troubleshooting the Bacterial Cell Wall Labeling (Basic Protocol 4)

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No fluorescence visualized after probe incorporation and click chemistry | Cells not growing robustly before addition of unnatural NAM | Option 1: Inoculate new culture from a new overnight. E. coli cells should take 45–60 mins to grow from OD600 0.2 to 0.6. Option 2: Retransform E. coli |

| Poor labeling | Too high fosfomycin concentration causing cell death instead of sugar incorporation | Utilize a lower concentration of fosfomycin |

| Click reaction not working as effectively as possible | Option 1: Ensure use of freshly prepared sodium ascorbate. Option 2: Change ligand for click reaction. TBTA can be substituted with BTTAA. If utilizing BTTAA, click reaction can be done in 1XPBS instead of 1:2 tert-butanol:water |

|

| High background when imaging | Fluorophore not being fully washed away | Add additional wash steps following the click reaction |

| Photobleaching | Option 1: Minimize exposure to laser light and keep in dark when not being imaged. Option 2: Utilize a different fluorophore less susceptible to photobleaching. |

Anticipated Results:

Basic protocol 1 will provide peracetylated 2-azido glucosamine. This precursor can be transformed into 2-azido or 2-alkyne NAM as described in Basic Protocol 2. Basic protocol 3 will result in 3 azido NAM.

Expect fluorescence microscopy results from Basic Protocol 4 are represented in Figure 5. The final 2-AzNAM probe can be purified with utilizing a Waters 2767 Sample Manager with HPLC and SQD2 MS using a Sunfire® Prep C18 OBD 5μm 19×100mm or 4.6×50mm Column or a Maxi-Clean™ SPE C18 plug. Both final purification methods result in labeling of E. coli cell wall (Figure 5). Utilizing the 3-AzNAM probe also results in labeling of the bacteria cells, but the labeling is concentrated to the PG septal division ring as opposed to the entire cell wall with the 2-AzNAM probe. Results from the Basic Protocol 5 show that our NAM probes are being directly incorporated into the bacterial cell wall (Figure 6). Peaks are confirmed by observing the proper isotope pattern with the observed mass within +/− 10 ppm of the expected mass over multiple trials of digestion.

Taken together, these results demonstrate that the synthetic NAM probes with modifications at the 2 and 3 positions can successfully label E. coli cells in order to study aspects of the bacterial cell wall. These probes can be applied to label a wide variety of bacterial organisms contain the recycling enzymes AmgK and MurU and under the presence of a lethal dose of fosfomycin.

Time Considerations:

Depending on synthetic expertise, the total time to access the 2 and 3 bioorthogonally tagged NAMs is approximately 3 weeks. The bacterial labeling can be accomplished in one day, with bacteria inoculation the day before, and imaged in a few hours. The mass spectrometry verification method can be completed in 3 or 4 days with the addition and growth with the sugar taking one day and the addition of lysozyme occurring 6 times over 3 days.

Significance Statement:

Peptidoglycan (PG) is a component of bacterial cell wall that serves as a recognition element for the human innate immune system. Synthetically derived fragments of PG known as muramyl dipeptide (MDP) with the core structure N-acetyl muramic acid (NAM) are known to initiate an immune response. However, naturally derived NAM fragments of PG remained understudied without a NAM based set of molecular probes. We developed methodology to allow for the metabolic incorporation of NAM bioorthogonal tags into the PG of whole bacterial cells. This approach to fluorescently label the NAM carbohydrate residue of PG using click chemistry provides an accessible chemical biology toolbox that is readily available for microbiologists and immunologists to study NAM-PG interactions.

Acknowledgements:

We thank Dr. Papa Nii Asare-Okai, the Director of the MS facility at the University of Delaware, for assistance in MS. We thank Dr. Jeffrey Caplan, the Director of Bioimaging, and the Delaware Biotechnology Institute for assistance with super-resolution microscopy. We thank Dr. Shi Bai for NMR support. For financial support, this project was supported by the NIH U01 Common Fund program with grant number U01CA221230-01; Delaware COBRE program with a grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, NIGMS P20GM104316-01A1. C.L.G. is a Pew Biomedical Scholar, Sloan Scholar, and Cottrell Scholar and thanks the Pew Foundation, Sloan Foundation and the Research Corporation for Science Advancement. K.E.D. and K.A.W. thank the NIH for support through a CBI training grant, 5T32GM008550. K.E.D. also thanks the University of Delaware for their support through the University Dissertation Fellowship program. For instrumentation support, the Delaware COBRE and INBRE programs supported this project with a grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences–NIGMS (5 P30 GM110758-02, P20GM104316-01A1, and P20 GM103446) from the National Institutes of Health.

Literature Cited:

- Aronoff MR, Gold B, and Raines RT 2016. 1,3-Dipolar Cycloadditions of Diazo Compounds in the Presence of Azides. Organic Letters. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreteau H, Kovač A, Boniface A, Sova M, Gobec S, and Blanot D. 2008. Cytoplasmic steps of peptidoglycan biosynthesis. FEMS Microbiology Reviews. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand JA, Auger G, Fanchon E, Martin L, Blanot D, Van Heijenoort J, and Dideberg O. 1997. Crystal structure of UDP-N-acetylmuramoyl-L-alanine:D-glutamate ligase from Escherichia coli. EMBO Journal. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouhss A, Crouvoisier M, Blanot D, and Mengin-Lecreulx D. 2004. Purification and characterization of the bacterial MraY translocase catalyzing the first membrane step of peptidoglycan biosynthesis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown ED, Vivas EI, Walsh CT, and Kolter R. 1995. MurA (MurZ), the enzyme that catalyzes the first committed step in peptidoglycan biosynthesis, is essential in Escherichia coli. Journal of Bacteriology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugg TDH, and Walsh CT 1992. Intracellular steps of bacterial cell wall peptidoglycan biosynthesis: Enzymology, antibiotics, and antibiotic resistance. Natural Product Reports. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaloupka J, Křečková P, and Řfhová L. 1962. The mucopeptide turnover in the cell walls of growing cultures of Bacillus megaterium KM. Experientia. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaloupka J, Křečková P, Říhová L, Халoуика Ю, Кршечкoба П, and Ржпеoба Л. 2008. Changes in the Character of the Cell Wall in Growth ofBacillus megaterium CulturesИ зменения характера клетoчнoй стенки вo время рoста культуры bacillus megaterium. Folia Microbiologica. [Google Scholar]

- D’Ambrosio EA, Drake WR, Mashayekh S, Ukaegbu OI, Brown AR, and Grimes CL 2019. Modulation of the NOD-like receptors NOD1 and NOD2: A chemist’s perspective. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel RA, and Errington J. 2003. Control of cell morphogenesis in bacteria: Two distinct ways to make a rod-shaped cell. Cell. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demeester KE, Liang H, Jensen MR, Jones ZS, D’Ambrosio EA, Scinto SL, Zhou J, and Grimes CL 2018. Synthesis of Functionalized N-Acetyl Muramic Acids to Probe Bacterial Cell Wall Recycling and Biosynthesis. Journal of the American Chemical Society. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle RJ, Chaloupka J, and Vinter V. 1988. Turnover of cell walls in microorganisms. Microbiological reviews. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk PJ, Ervin KM, Volk KS, and Ho H-T 2002. Biochemical Evidence for the Formation of a Covalent Acyl-Phosphate Linkage between UDP- N -Acetylmuramate and ATP in the Escherichia coli UDP- N -Acetylmuramate: l -Alanine Ligase-Catalyzed Reaction † . Biochemistry. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale RT, and Brown ED 2015. New chemical tools to probe cell wall biosynthesis in bacteria. Current Opinion in Microbiology. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner EC, Bernard R, Wang W, Zhuang X, Rudner DZ, and Mitchison T. 2011. Coupled, circumferential motions of the cell wall synthesis machinery and MreB filaments in B. subtilis. Science. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girardin SE, Travassos LH, Hervé M, Blanot D, Boneca IG, Philpott DJ, Sansonetti PJ, and Mengin-Lecreulx D. 2003. Peptidoglycan Molecular Requirements Allowing Detection by Nod1 and Nod2. Journal of Biological Chemistry. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gisin J, Schneider A, Nägele B, Borisova M, and Mayer C. 2013. A cell wall recycling shortcut that bypasses peptidoglycan de novo biosynthesis. Nature Chemical Biology. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodell EW 1985. Recycling of murein by Escherichia coli. Journal of Bacteriology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodell EW, and Schwarz U. 1985. Release of cell wall peptides into culture medium by exponentially growing Escherichia coli. Journal of Bacteriology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon E, Flouret B, Chantalat L, Van Heijenoort J, Mengin-Lecreulx D, and Dideberg O. 2001. Crystal Structure of UDP-N-acetylmuramoyl-L-alanyl-D-glutamate: meso-Diaminopimelate Ligase from Escherichia Coli. Journal of Biological Chemistry. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Heijenoort J. 2001. Formation of the glycan chains in the synthesis of bacterial peptidoglycan. Glycobiology. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Höltje JV 1998. Growth of the stress-bearing and shape-maintaining murein sacculus of Escherichia coli. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inohara N, Ogura Y, Fontalba A, Gutierrez O, Pons F, Crespo J, Fukase K, Inamura S, Kusumoto S, Hashimoto M, et al. 2003. Host recognition of bacterial muramyl dipeptide mediated through NOD2: Implications for Crohn’s disease. Journal of Biological Chemistry. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs C, Huang LJ, Bartowsky E, Normark S, and Park JT 1994. Bacterial cell wall recycling provides cytosolic muropeptides as effectors for beta-lactamase induction. The EMBO journal. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JW, Fisher JF, and Mobashery S. 2013. Bacterial cell-wall recycling. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahan FM, Kahan JS, Cassidy PJ & Kropp H The mechanism of action of fosfomycin (phosphonomycin). Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 235, 364–386 (1974). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocaoglu O, Calvo RA, Sham LT, Cozy LM, Lanning BR, Francis S, Winkler ME, Kearns DB, and Carlson EE 2012. Selective penicillin-binding protein imaging probes reveal substructure in bacterial cell division. ACS Chemical Biology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuru E, Hughes HV, Brown PJ, Hall E, Tekkam S, Cava F, De Pedro MA, Brun YV, and Vannieuwenhze MS 2012. In situ probing of newly synthesized peptidoglycan in live bacteria with fluorescent D-amino acids. Angewandte Chemie - International Edition. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebar MD, May JM, Meeske AJ, Leiman SA, Lupoli TJ, Tsukamoto H, Losick R, Rudner DZ, Walker S, and Kahne D. 2014. Reconstitution of peptidoglycan cross-linking leads to improved fluorescent probes of cell wall synthesis. Journal of the American Chemical Society. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang H, DeMeester KE, Hou CW, Parent MA, Caplan JL, and Grimes CL 2017. Metabolic labelling of the carbohydrate core in bacterial peptidoglycan and its applications. Nature Communications. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liechti GW, Kuru E, Hall E, Kalinda A, Brun YV, Vannieuwenhze M, and Maurelli AT 2014. A new metabolic cell-wall labelling method reveals peptidoglycan in Chlamydia trachomatis. Nature. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahal LK, Yarema KJ, and Bertozzi CR 1997. Engineering chemical reactivity on cell surfaces through oligosaccharide biosynthesis. Science. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JW, Chamessian AG, McEnaney PJ, Murelli RP, Kazmiercak BI, and Spiegel DA 2010. A Biosynthetic Strategy for Re-engineering the Staphylococcus aureus Cell Wall with Non-native Small Molecules. ACS Chemical Biology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JT, and Uehara T. 2008. How Bacteria Consume Their Own Exoskeletons (Turnover and Recycling of Cell Wall Peptidoglycan). Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pucci MJ, Discotto LF, and Dougherty TJ 1992. Cloning and identification of the Escherichia coli murB DNA sequence, which encodes UDP-N-acetylenolpyruvoylglucosamine reductase. Journal of bacteriology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers HJ 1974. PEPTIDOGLYCANS (MUCOPEPTIDES): STRUCTURE, FUNCTION, AND VARIATIONS. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz N. 2008. Bioinformatics identification of MurJ (MviN) as the peptidoglycan lipid II flippase in Escherichia coli. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadamoto R, Matsubayashi T, Shimizu M, Ueda T, Koshida S, Koda T, and Nishimura SI 2008. Bacterial surface engineering utilizing glucosamine phosphate derivatives as cell wall precursor surrogates. Chemistry - A European Journal. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadamoto R, Niikura K, Sears PS, Liu H, Wong CH, Suksomcheep A, Tomita F, Monde K, and Nishimura SI 2002. Cell-wall engineering of living bacteria. Journal of the American Chemical Society. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxon E, Armstrong JI, and Bertozzi CR 2000. A “traceless” Staudinger ligation for the chemoselective synthesis of amide bonds. Organic Letters. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxon E, and Bertozzi CR 2000. Cell surface engineering by a modified Staudinger reaction. Science. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sham LT, Butler EK, Lebar MD, Kahne D, Bernhardt TG, and Ruiz N. 2014. MurJ is the flippase of lipid-linked precursors for peptidoglycan biogenesis. Science. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shieh P, Siegrist MS, Cullen AJ, and Bertozzi CR 2014. Imaging bacterial peptidoglycan with near-infrared fluorogenic azide probes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegrist MS, Whiteside S, Jewett JC, Aditham A, Cava F, and Bertozzi CR 2013. D-amino acid chemical reporters reveal peptidoglycan dynamics of an intracellular pathogen. ACS Chemical Biology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strominger JL 2007. Bacterial cell walls, innate immunity and immunoadjuvants. Nature Immunology. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STROMINGER JL, PARK JT, and THOMPSON RE 1959. Composition of the cell wall of Staphylococcus aureus: its relation to the mechanism of action of penicillin. The Journal of biological chemistry. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiyanont K, Doan T, Lazarus MB, Fang X, Rudner DZ, and Walker S. 2006. Imaging peptidoglycan biosynthesis in Bacillus subtilis with fluorescent antibiotics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh C. 2000. Molecular mechanisms that confer antibacterial drug resistance. Nature. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Lazor KM, DeMeester KE, Liang H, Heiss TK, and Grimes CL 2017. Postsynthetic modification of bacterial peptidoglycan using bioorthogonal n-acetylcysteamine analogs and peptidoglycan o-acetyltransferase B. Journal of the American Chemical Society. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y, Munshi S, Li Y, Pryor KAD, Marsilio F, and Leiting B. 1999. Crystallization and preliminary X-ray analysis of the Escherichia coli UDP-MurNAc-tripeptide D-alanyl-D-alanine-adding enzyme (MurF). Acta Crystallographica Section D: Biological Crystallography. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]