Abstract

SUMMARY

Background:

Bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (VRd) is a standard therapy for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM). Carfilzomib, a next-generation proteasome inhibitor, in combination with lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (KRd) has shown excellent efficacy in phase II trials and may improve outcomes compared with VRd.

Methods:

In this randomized, open label, phase 3 trial, we recruited patients with NDMM, aged 18 years and older, who were not planned for immediate autologous stem-cell transplant (ASCT). Key inclusion was absence of the following high-risk features (del17p, t(14;16), t(14;20), plasma cell leukemia) and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0–2. Patients were randomized (1:1) to receive VRd or KRd for 36 weeks followed by a 2nd randomization (1:1) to indefinite versus 2 years of lenalidomide maintenance. Allocation was stratified by intent to ASCT at disease progression and was not masked to investigators and patients. VRd regimen included bortezomib 1·3 mg/m2 on days 1, 4, 8, and 11 (d 1, 8 for cycles 9–12), lenalidomide 25 mg daily on days 1–14, and dexamethasone 20 mg on days 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 9, 11, 12 for twelve 3-week cycles. KRd regimen included carfilzomib 36 mg/m2 on days 1, 2, 8, 9, 15, 16, lenalidomide 25 mg daily on days 1–21 and dexamethasone 40 mg on days 1, 8, 15, and 22 for nine 4-week cycles. The primary endpoint was progression-free survival, defined as the time from first randomization to disease progression or death, analyzed by intention to treat. Safety was assessed in patients who received at least one dose of their assigned treatment. Study recruitment is complete, all patients have completed induction therapy, and patients continue on maintenance as per second randomization and follow up is ongoing. The trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov:NCT01863550.

Findings:

Between December 6, 2013 and February 6, 2019, we randomly assigned 1087 patients at 272 participating institutions (542 to VRd, 545 to KRd). At an estimated median (IQR) follow-up of 9 (5–23) months from randomization, median PFS was 34·4 (95% CI 30·1-NE) months for VRd compared with 34·6 (95% CI 28·8–37·8) months for KRd; the PFS treatment hazard ratio (HR=KRd/VRd) was 1·04 (95% CI 0·83–1·31); P=0·74. The most common grade 3–4 non-hematologic adverse events included fatigue (34 [6%] vs. 29 [6%]), hyperglycemia (23 [4%] vs. 34[7%]), peripheral neuropathy (44 [8%]vs. 4 [<1%]), dyspnea (9 [2%] vs. 38 [7%]) and thromboembolic events (11 [2%]vs. 26 [5%]), for the VRd (n=426) and KRd (n=527) arms, respectively. The overall non-hematologic grade ≥3 toxicities were 218 (41%) and 254 (48%) including composite rates of 25 (5%) and 84 (16%) cardiac, pulmonary and renal toxicity, and 43 (8%) and 5 (1%) peripheral neuropathy, for the VRd and KRd arms, respectively. Serious adverse events were reported in 116 (22%) patients in VRd arm and in 234 (45%) patients in KRd arm. Treatment related deaths occurred in 2(<1%) of VRd and 11 (2%) of KRd patients.

Interpretation:

In this randomized phase 3 trial, KRd did not improve PFS compared with VRd in NDMM. A significantly higher rate of cardio-pulmonary and renal toxicity was observed with KRd and neuropathy with VRd. VRd remains the standard triplet induction regimen for standard and intermediate risk NDMM, and a suitable backbone for 4-drug combinations.

Funding:

The trial was funded by the US National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, and Amgen.

INTRODUCTION

The approach to initial treatment of active multiple myeloma (MM) has evolved considerably over the past 2 decades with the introduction of proteasome inhibitors (PI) and immunomodulatory (IMiD) drugs, and more recently monoclonal antibodies, often used in various combinations.1,2 The initial therapy plays a critical role in determining the long-term outcomes, especially by enabling rapid disease control and decreasing the risk of toxicity and early death.3 Improvements in depth and duration of response as well as supportive care have significantly improved the survival for MM in the recent years.4,5 This progress is noted both in transplant eligible, as well as in older patients not eligible for autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT).

Bortezomib, lenalidomide, dexamethasone (VRd) is a standard triplet regimen used for initial therapy of myeloma, and data from phase II trials as well as randomized phase III trials have shown evidence of long-term efficacy and safety.6–10 The SWOG trial S0777 demonstrated that VRd improves progression free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) compared with lenalidomide and dexamethasone (Rd), without a significant increase in the toxicity.8 In the Intergroupe Francophone du Myelome (IFM) 2009 trial, VRd with or without ASCT, had an excellent 4-year OS of over 80%.9 VRd is effective in providing rapid, deep, and durable responses when used for initial treatment with or without ASCT consolidation.6–9,11 However, the high rate of bortezomib induced peripheral neuropathy (PN), although less with subcutaneous administration, often precludes long-term administration. More importantly, there is clearly a need to improve on long-term outcomes of NDMM since PFS with VRd is typically shorter than 4 years, and almost all patients eventually relapse.8,9

Carfilzomib is a second-generation PI approved for the treatment of relapsed MM that selectively and irreversibly binds to the proteasome and may be more potent than bortezomib.12 In phase II trials in newly diagnosed MM (NDMM), carfilzomib, lenalidomide, dexamethasone (KRd) has shown high overall response rates and deep durable responses, suggesting that KRd may provide superior outcomes to VRd.13,14 Based on these results and its efficacy in relapsed MM, this triplet combination is increasingly being adopted into clinical practice for initial therapy of NDMM, without a phase III trial demonstrating improved efficacy over VRd. However, a prior randomized phase III trial comparing carfilzomib, melphalan and prednisone to bortezomib, melphalan, and prednisone failed to show a benefit for carfilzomib when used as primary therapy in older, transplant ineligible patients.15 The goal of this investigator-initiated intergroup randomized phase 3 trial was to determine if KRd is superior to VRd in the treatment of newly diagnosed MM among patients who were not being considered for upfront ASCT. In addition, the trial has an independent longer-term goal comparing OS with lenalidomide maintenance given indefinitely till progression versus 2 years limited duration, to better define the ideal duration of initial therapy for MM in the non-transplant setting. We report the final analysis of the first primary endpoint comparing VRd versus KRd as initial therapy for newly diagnosed MM.

METHODS

Study design and participants

This was a randomized, open label, phase 3 trial, that was conducted by the ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group (ECOG-ACRIN) and run through the National Clinical Trials Network (NCTN) in collaboration with the US cooperative groups, enrolling patients from 272 sites (appendix p51) between November 2013 and January 2019. The study was developed in collaboration with the Cancer Therapy and Evaluation Program (CTEP) of the National Cancer Institute and funded by the NCI. The study was approved by the Central Institutional Review Board of the NCI and by independent ethics committee or institutional review board at each participating site as required. The entire study protocol is available with the full text of this article in the appendix. The trial was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonization of Good Clinical Practice guidelines. All the patients provided written informed consent. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Patients with newly diagnosed MM, aged 18 years or older, who were considered ineligible to undergo ASCT or not intending to proceed to immediate stem cell transplant (as part of initial therapy), were enrolled provided they had measurable or evaluable disease confirmed by one of the following: (a) serum monoclonal protein >/=1·0 g/dL by serum protein electrophoresis, (b) >/=200 mg/24 hours of monoclonal protein on a 24-hour urine protein electrophoresis, (c) involved free light chain (FLC) >/=10 mg/dL AND abnormal serum immunoglobulin kappa to lambda FLC ratio (<0·26 or >/=1·65, or (d) monoclonal bone marrow plasmacytosis >/=30% (evaluable disease). Patients could receive up to one cycle (4 weeks or less) of prior chemotherapy, provided they had no more than 160 mg of dexamethasone for treatment of symptomatic MM, and had no prior exposure to lenalidomide, bortezomib or carfilzomib. Patients with high-risk MM as defined by one of the following: (a) t(14;16), t(14;20) or deletion 17p on FISH, (b) serum LDH >2xULN, (c) more than 20% circulating plasma cells on peripheral blood smear differential or 2000 plasma cells/microliter on WBC differential of peripheral blood, or (d) high-risk GEP70 signature by gene expression if tested, were not enrolled. We elected to exclude these patients with high risk multiple myeloma as a parallel phase 3 trial (NCT01668719) in the US cooperative group was exploring more intense regimens in that patient group. Patients were eligible if they had ECOG PS 0, 1 or 2 (PS 3 allowed if secondary to pain), hemoglobin level ≥ 8·0 g per deciliter, an absolute neutrophil count of ≥1000/mm3, a platelet count of ≥75,000/mm3, aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase levels < 2·5 times the upper limit of the normal range, a total bilirubin level ≤ 1·5 mg/dL, and creatinine clearance of ≥30 ml/min. Patients with peripheral neuropathy grade 2 or higher, evidence of congestive heart failure (NYHA Class III or IV) or myocardial infarction within the previous 6 months are excluded. Additional eligibility criteria are listed in the appendix p9. All screening assessments were done by the enrolling institution using commercial laboratories and no central review was required. The FISH testing required that probes for all high risk markers were included in the panel: t(14;16), t(14;20), del17p.

Randomization and masking

Patients were randomly assigned with equal allocation to receive induction therapy with bortezomib plus lenalidomide and dexamethasone (VRd; twelve 3-week cycles) or carfilzomib plus lenalidomide and dexamethasone (KRd; nine 4-week cycles) for 36 weeks (appendix p12). Patients completing induction phase were randomized a second time with equal allocation to indefinite versus 2 years of lenalidomide maintenance. Patients were stratified by intent for transplant at disease progression for the first randomization and by the induction therapy received for the second randomization. The permuted blocks algorithm was used to balance treatment assignment within strata, with dynamic balancing on main ECOG-ACRIN institutions. Investigators and patients were not masked to study treatment but the Data Safety and Monitoring Committee (DSMC) was masked to treatment allocation during assessment of efficacy at predefined analysis timepoints. Randomization procedures were developed and maintained at the ECOG-ACRIN data management center.

Procedures

Patients in VRd arm received bortezomib 1·3 mg/m2 administered subcutaneously or intravenously on days 1, 4, 8, and 11 (d 1, 8 for cycles 9–12), lenalidomide 25 mg orally daily on days 1–14, and dexamethasone 20 mg orally on days 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 9, 11, 12 of a 3-week cycle for 12 cycles. Dexamethasone was reduced to 10 mg on days 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 9, 11, 12 for cycle 5–8 and 10 mg days 1, 2, 8, and 9 in cycles 9–12. Patients assigned to KRd arm received carfilzomib 36 mg/m2 intravenously on days 1, 2, 8, 9, 15, 16 (carfilzomib was given at 20 mg/m2 on days 1 and 2 of cycle 1) along with lenalidomide 25 mg orally once daily on days 1–21 and dexamethasone 40 mg orally once weekly on days 1, 8, 15, and 22 of a 4-week cycles for 9 cycles. Dexamethasone was reduced to 20 mg PO days 1, 8, 15, 22 for cycles 5–9. Overall, the lenalidomide dose translated to 27 weeks and 24 weeks of lenalidomide in the KRd and VRD arms over 36 weeks of induction therapy, respectively. In both arms, starting dose of lenalidomide was reduced to 10 mg in patients with creatinine clearance of 30–59 ml/min. If the clearance improved to ≥ 60 ml/min, the dose could be increased to 25 mg (or the next dose level from current dose) provided the patient had not experienced any of the toxicities that would have required a dose reduction for lenalidomide. Dose modifications were allowed for all drugs for adverse events, which were at least possibly related to drug. Supportive care for specific drug related toxicities were left to the individual institution’s standard practice, given that all drugs are currently approved for treatment of myeloma. Patients who were registered to maintenance portion of the trial and randomized received 15 mg lenalidomide orally, once daily on days 1–21 of a 4-week cycle, continued for two years or indefinitely till progression based on the randomization. Stem cell collection was permitted at investigator discretion after completing 12 weeks of induction therapy, with up to 5 weeks of treatment interruption allowed for apheresis. Patients came off treatment for disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, initiation of non-protocol therapy or withdrawal of consent.

Disease assessments included serum and 24-hour urine protein electrophoresis were performed after every cycle during the induction phase and every three cycles during the maintenance phase. Patients who had serum free light chain only measurable disease had the FLC assay performed at the same frequency. Bone marrow examination was performed after 12 and 36 weeks and for documentation of a complete response when serum and urine immunofixations became negative. If measurable disease was only present in bone marrow, biopsies were done after the first 2 cycles of therapy and then every 3–4 cycles per investigator discretion. All patients, including those who discontinued assigned induction treatment early whether or not proceeding to non-protocol therapy, were followed for response until disease progression and for survival every 3 months for 2 years, then every 6 months through year 5, and then annually through year 15.

Adverse events were graded according to NCI Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), version 4. Treatment attribution of possibly or higher defined treatment-related and any attribution defined treatment-emergent adverse events. We followed standard practice in reporting serious adverse events (SAEs) as defined per protocol. Reporting of grades 1–3 hematologic and grades 1–2 non-hematologic events were not part of the required reporting.

During the induction phase, QOL assessments were performed at 4 timepoints: for the VRd arm, at the end of cycles 1, 4, 8 and 12 and for the KRd arm, at the end of cycles 1, 3, 6 and 9. QoL was also assessed at early discontinuation of induction therapy for any reason.

Outcomes

The primary endpoint for the induction phase of the trial was progression-free survival, defined as the time from the induction randomization (R1) until the earlier of progression or death due to any cause. Only deaths that occurred within 3 months of the last disease evaluation are considered events. Patients alive without disease progression are censored at date of last disease evaluation. PFS follow-up is based on adequate documentation that the patient is progression-free as assessed by central review by the ECOG-ACRIN data management team. Patients proceeding to stem cell transplantation (SCT) or alternative therapy prior to progression remain censored at the time of last disease evaluation (progression-free). Secondary efficacy endpoints included overall response rate (ORR), time to progression (TTP), duration of response (DOR), overall survival, (OS) and minimal residual disease (MRD) negative rate measured by flow cytometry. Disease response and progression were assessed according to the International Myeloma Working Group uniform response criteria (appendix p49); ORR was defined as partial response or better .16 OS was defined as the time from induction randomization (R1) to death due to any cause or censored at the date last known alive. TTP was defined as the time from the induction randomization (R1) to progression or censored at the date of last disease evaluation for those without progression reported. DOR (analysis not completed) was defined as the time from first objective response (partial response or better) since induction randomization (R1) until progression or censored at date of last disease evaluation for those without progression. MRD was estimated per established methods as described in the Supplementary appendix p8. Quality of Life (QoL) assessments were performed using four validated scales [FACT-Physical, FACT-Functional (F), FACT-Neurotoxicity (Ntx), and FACT-Multiple Myeloma (MM)] to assess the differential impact of induction treatment on patient reported health-related QoL. Compliance was measured as the percentage of patients on treatment submitting adequate data per FACT scoring guidelines. Change in the FACT-Ntx Trial Outcomes Index (TOI) to the end induction from baseline was the primary endpoint for the induction QoL studies with a minimally important difference (MID) of 6–8 points pre-specified parallel to half of the reported standard deviation of the instrument in a similar setting.

Statistical analysis

This two-stage randomized study was originally designed and powered to investigate two questions: whether induction with KRd was superior to VRd in terms of PFS and whether following induction with a proteasome inhibitor–IMiD combination, indefinite lenalidomide maintenance therapy is superior to limited duration (2 year) maintenance. To implement these two comparisons, 756 patients were planned to be enrolled. Given a lower than anticipated number of patients proceeding to the second randomization and in order to make the PFS following induction as a co-primary endpoint with maintenance OS, the study was revised with an enrollment target of 1080 patients (June 2018, appendix p5).

The primary analysis for PFS comparison was performed in the intention-to-treat population, which included all randomized patients (appendix p2). The Kaplan-Meier (KM) method was used to estimate survival distributions by arm using all data, while ignoring maintenance.17 A stratified log-rank test was used to compare survival distributions between induction arms. 18 Treatment hazard ratios (HR; KRd/VRd) were estimated with the use of stratified Cox proportional hazards (PH) regression model.19 Sensitivity analyses and post-hoc subgroup analyses were done using similar methods. With 1,080 patients randomized at induction and 5 years of follow-up (399 PFS events), there was 80% power at a 1-sided 0·025 significance level to detect a 25% reduction in the hazard rate: hypothesized median PFS on VRd of 3 years versus 4 years on KRd (HR=0.75). Sequential monitoring of PFS was incorporated with three interim analyses (IA) at 54% (n=215 events), 68% (n=272 events) and 84% (n=333 events) of full information, expected at 3.5, 4 and 4.5 years from R1, to evaluate efficacy and futility of the PFS comparison. Critical values for efficacy evaluation at each IA were based on truncated version of the Lan-DeMets error spending function corresponding to the O’Brien-Fleming boundaries.20 The Wieand rule was used for futility (HR≥1).21 In separate PFS sensitivity analyses, the eligible and treated population is evaluated, patients are censored at time of alternative therapy or SCT, patients are censored at date of last contact instead of date of last disease assessment, or all deaths are counted as events. Furthermore, Cox PH multivariable model was run with treatment and SCT as a time-varying covariate. For the PFS analyses of the treatment effect within subgroups, proportional hazards was examined using Schoenfeld residuals and no major concerns were identified. The safety population included all patients receiving at least one treatment dose and, of note, grade 3 hematologic toxicity was not required reporting. Response also was evaluated in the treated population. The Chi square statistic was calculated for 2×2 contingency tables of response and toxicity rates by treatment arm (1 degree of freedom). Comparison of change in QoL score over induction was assessed using the Wilcoxon test. All reported p-values are two-sided, and CIs are at the 95% level. Analyses were performed using SAS (version 4) and R (version 3.4.3).

The trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT01863550.

Role of the funding source

The NCI provided input on the design of the trial, but had no role in the analysis, interpretation, decision to publish, or writing of the report. The manufacturer of carfilzomib (Amgen Corporation, San Francisco, USA) was not involved in the design, analysis, interpretation, or writing of this trial. The corresponding author (SKK) and statistician (SJ) had full access to all the data in the study and the final responsibility to submit for publication.

RESULTS

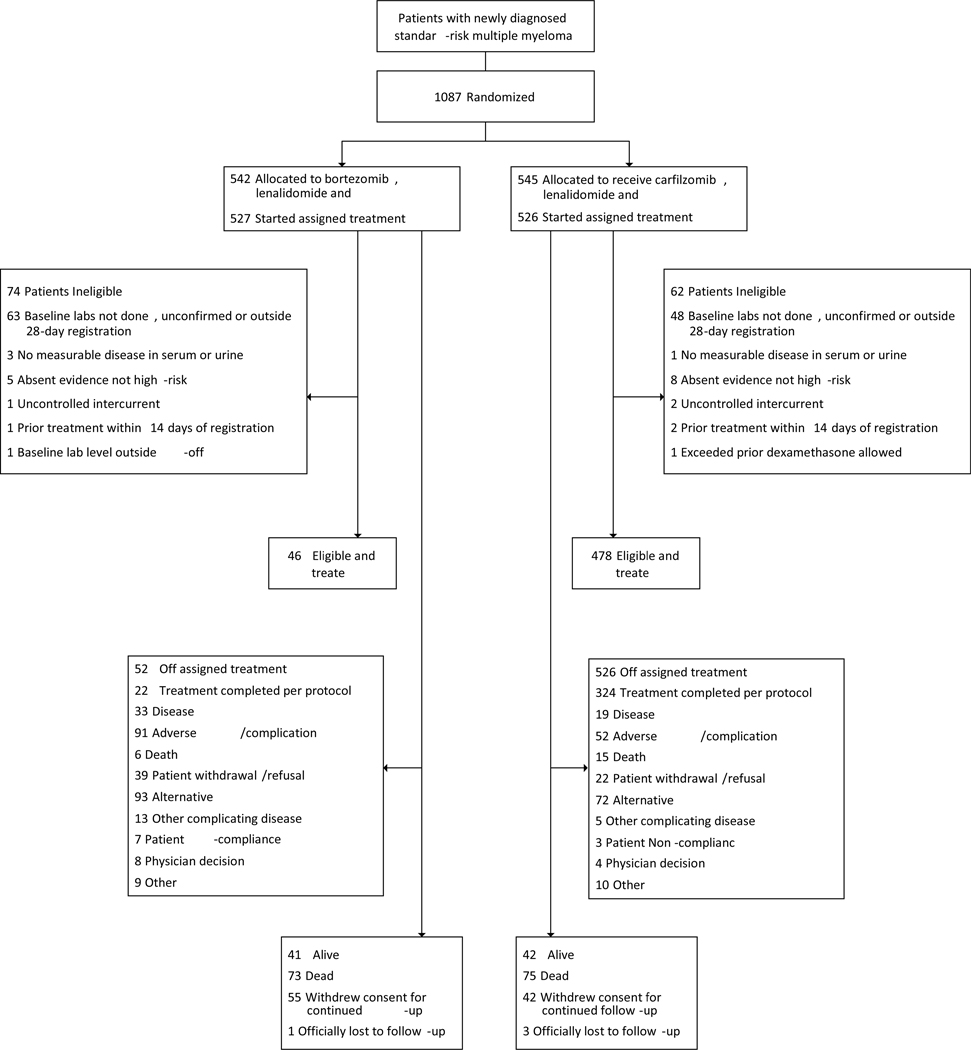

From December 6, 2013 to February 6, 2019, 1087 patients were randomly assigned to induction therapy with VRd (n=542) or KRd (n=545) and were included in the intention to treat population. Assigned treatment was started in 1053 (97%) of the randomized patients; 527 (97%) in the VRD arm and 526 (97%) in the KRd arm and were included in the response assessable and safety populations (Figure 1). Demographic and clinical characteristics were well balanced between the two arms (Table 1). The median age of the study population was 65 years (range 32–88). Either before or after starting assigned therapy, 136 (12.5%) of 1087 enrolled patients were deemed ineligible (74 [14%] on VRd and 62 [11%] on KRd), most commonly for inadequate baseline data either not done, unconfirmed or outside the 28-day registration window. 12 patients have unknown eligibility status with queries pending resulting in an eligible and treated population of 939 (86%) of 1087 enrolled patients. Cutoff date for the analysis was January 7, 2020, at which time all patients have been off induction phase, with 516 (48%) of 1087 enrolled patients randomized to lenalidomide maintenance (260 to indefinite maintenance and 256 to 2-year maintenance). All planned cycles of induction therapy were completed in 552 (52%) of 1053 treated patients including 228 (43%) of the 527 treated VRd patients and 324 (62%) of the 526 treated KRd patients (Figure 1). The reasons for early discontinuation of induction therapy are as shown overall (appendix p25) and by age (appendix p26). The median (IQR) duration of induction therapy was 7·1 (3·4–8·9) months for the VRd arm and 8·5 (5·0–9·1) months for the KRd arm; for patients not proceeding to second randomization (309 in VRd and 227 in KRd), it was 3·8 months (2·7–5·5) for the VRd arm and 4·5 months (2·8–6·8) for the KRd arm. Overall, 298 (27%) of 1087 enrolled patients have proceeded to ASCT [152 (28%) of 542 enrolled VRD patients, 146 (27%) of 545 enrolled KRd patients] at a median (IQR) duration from randomization of 6·5 (4·8–10·4) months in the VRd arm and 8·9 (6·0–15·1) months in the KRd arm.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram showing the patient disposition

Table 1.

Baseline Patient & Disease Characteristics

| VRd (n=542) | KRd (n=545) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 64 (57–71) | 65 (59–71) | |

| >/=70 years | 167 (31%) | 177 (33%) | |

| Time from Diagnosis (wks) | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–4) | |

| Gender | Male | 315 (58%) | 327 (60%) |

| Female | 227 (42%) | 218 (40%) | |

| Race | White | 443 (85%) | 448 (86%) |

| Black | 68 (13%) | 59 (11%) | |

| Other | 13 (2%) | 12 (2%) | |

| Missing/Unk | 18 | 26 | |

| Non-White | 81 (15%) | 71 (14%) | |

| ECOG PS | PS0 | 212 (39%) | 241 (44%) |

| PS1 | 270 (50%) | 249 (46%) | |

| PS2 | 50 (9%) | 45 (8%) | |

| PS3 | 10 (2%) | 10 (2%) | |

| PS>0 | 330 (61%) | 304 (56%) | |

| Intent to Transplant at PD | Yes | 396 (73.1) | 398 (73.0) |

| ISS Stage | I | 213 (39%) | 184 (34%) |

| II | 188 (35%) | 199 (37%) | |

| III | 138 (26%) | 159 (29%) | |

| Missing | 3 | 3 | |

| I-II | 401 (74%) | 383 (71%) | |

| Measurable Disease Type | SPEP&UPEP | 115 (21%) | 114 (21%) |

| SPEP | 305 (56%) | 296 (54%) | |

| UPEP | 57 (11%) | 79 (14%) | |

| FLC | 58 (11%) | 51 (9%) | |

| Bone Marrow | 4 (<1%) | 4 (<1%) | |

| Not Measurable | 3 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) | |

| Cytogenetics* | Normal | 326 (72%) | 331 (72%) |

| Abnormal | 128 (28%) | 127 (28%) | |

| Missing | 88 | 67 | |

| FISH | Normal | 115 (21%) | 115 (21%) |

| Abnormal | 423 (79%) | 427 (79%) | |

| Missing | 4 | 3 | |

| Plasma cell (%) | 52 (30–75) | 51 (30–72) | |

| Missing | 8 | 3 | |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3·8 (3·4–4·2) | 3·8 (3·4–4·2) | |

| Missing | 1 | 2 | |

| Beta2microglobulin (ug/mL) | 3·6 (2·6–5·6) | 3·9 (2·8–6) | |

| Missing | 2 | 1 | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 11·0 (9·6–12·4) | 11·2 (9·8–12·6) | |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 9·3 (8·9–9·8) | 9·4 (8·9–9·8) | |

| Missing | 1 | 0 | |

Data are median (IQR) or N (%); Missing data are excluded from calculations

Metaphase cytogenetics was considered positive in the presence of any abnormality

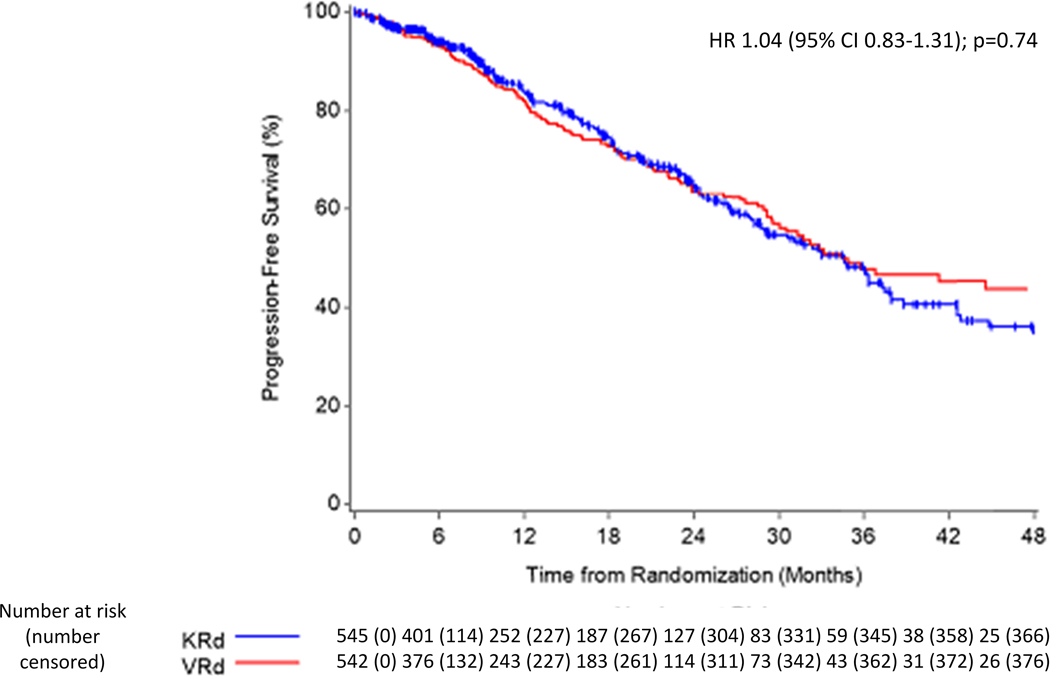

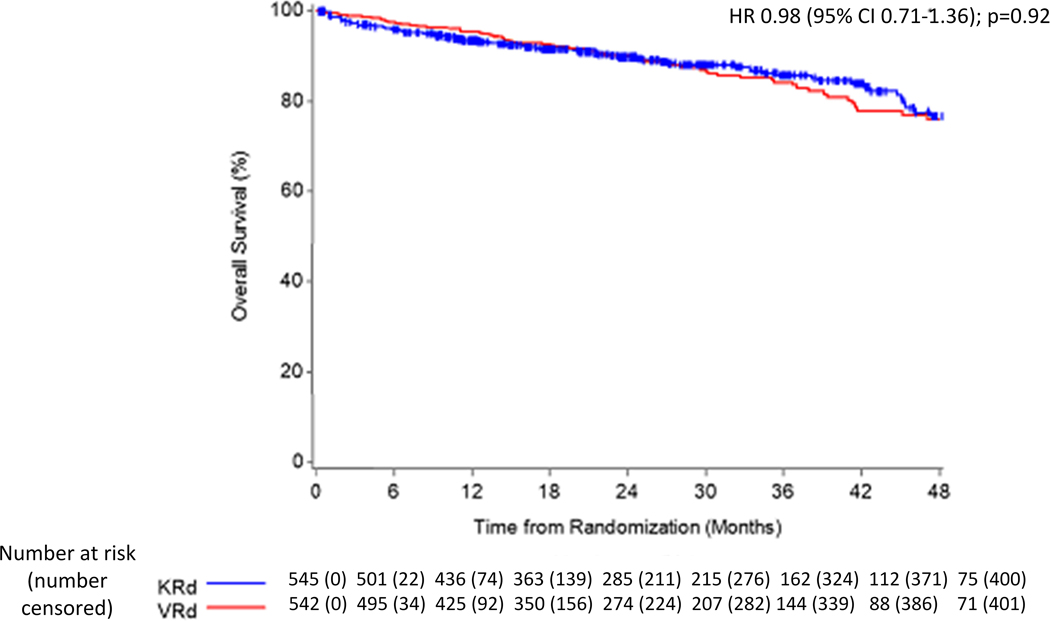

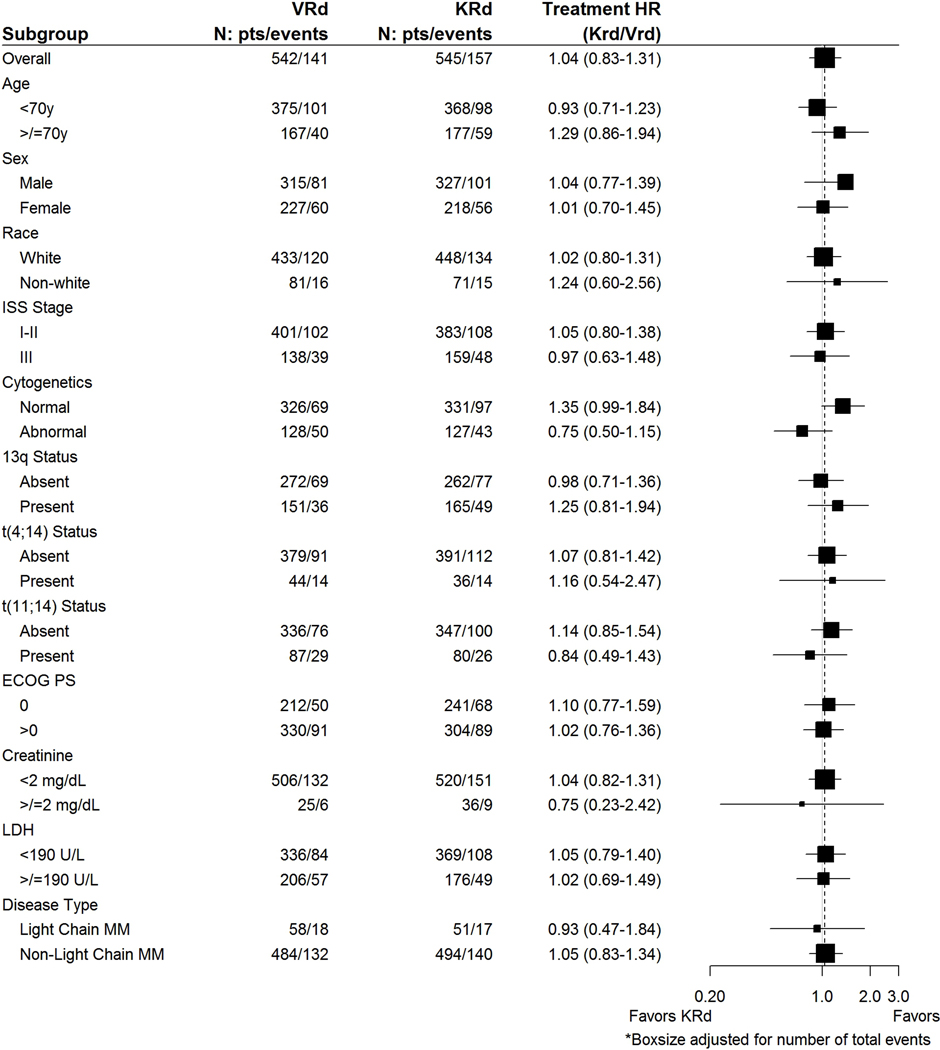

At an estimated median (IQR) follow-up of 9 (5–23) months from randomization, disease progression or death as per the event definition has been observed in 298 (27%) of 1087 enrolled patients: 141 (26%) for VRd and 157 (29%) for KRd. KM estimate for median PFS was 34·4 (95% CI 30·1-NE) months for VRd compared with 34·6 (95% CI 28·8–37·8) months for KRd; the PFS treatment hazard ratio (HR=KRd/VRd) was 1·04 (95% CI 0·83–1·31); P=0·74 (Figure 2a). The DSMC recommended release of data based on futility. The PFS remained comparable between arms among all subgroups examined (Figure 3, appendix p31). Among the patients over 70 years, the median PFS was 37 months (95% CI 29-NE) in the VRd arm and 28 months (95% CI 24–36) in the KRd arm (appendix p31). The 3-year cumulative incidence of progression considering death as a competing risk was 43% in each treatment arm (appendix p17). PFS results were similar in the eligible and treated subset (appendix p33). Importantly, when patients receiving SCT or alternative therapy were censored at that time [42 fewer events; median follow-up 9·4 months], the median PFS was 31·7 (95% CI 28·5–44·6) months for VRd and 32·8 (95% CI 27·2–37·5) months for KRd; HR=0·98 (95% CI 0·77–1·25) (appendix p33). In the adjusted Cox PH model with SCT as a time-varying covariate, the results for the treatment effect were consistent with the primary analysis [HR=1·01 (95% CI 0·81–1·27)] even though ASCT was significantly associated with PFS and showed a clinically meaningful impact [HR=0·61 (p=0·01)](data not shown). Results of KRd not conferring a PFS benefit were consistent for all other PFS sensitivity analyses (appendix p33). The median time to progression was 44.6 (95% CI 32·2-NE) months on the VRd arm and 36.3 (95% CI 31·7–42·8) months on the KRD arm [HR=0·97 (95% CI 0·75–1·24)] (appendix p16).

Figure 2.

Panel A: Progression-free survival from randomization in the intention-to-treat population. The results represent data at the second of the three planned interim analysis, with 298 PFS events (75% of 399 planned). HR=hazard ratio.

Panel B: Overall survival in the intention-to-treat population. The results represent data as of the cut-off date used in the planned interim analysis for the primary PFS endpoint.

Figure 3.

Subgroup analysis of progression-free survival. Shown are the results of an analysis of progression-free survival in specific subgroups based on stratified Cox proportional hazards regression. The International Staging System (ISS) disease stage, based on serum β2-microglobulin and albumin levels, consists of three stages. Cytogenetics represent conventional metaphase karyotype analysis. Presence of deletion 13q and t(4;14) were determined on fluorescence in situ hybridization performed on tumor cells at baseline. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status is scored on a scale from 0 to 5, with 0 indicating no symptoms and higher scores indicating increasing disability. The subgroup analysis for the type of multiple myeloma was performed on data from patients who had measurable disease in serum.

Best overall response of partial response or better (objective response rate, ORR) during induction was achieved by 444 (84%) of 527 treated VRd patients and 456 (87%) of 526 treated KRd patients (p=0·26); corresponding rates of VGPR or better were 65% (341/527) versus 74% (388/526), respectively, (p<0·01) (Table 2). A complete response or better was observed in 78 (15%) of treated VRD patients versus 96 (18%) of treated KRd patients, (p=0·13). The median time (IQR) to first response was 1·0 (0·8–1·5) months for VRd and 1·2 (1·1–1·5) months for KRd; ORR at 12 weeks was 80% (422/527) and 82% (433/526) for VRd and KRd, respectively (appendix p34). MRD negativity (in CR) was seen in 38 (7%) of treated VRd patients versus 54 (10%) of treated KRd patients (p=0·08).

Table 2.

Induction Best Overall Response

| VRd | KRd | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| (n=527) | (n=526) | ||

| Category | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Stringent Complete Response | 21 (4%) | 31 (6%) | |

| Complete Response | 57 (11%) | 65 (12%) | |

| Very Good Partial Response | 263 (50%) | 292 (56%) | |

| Partial Response | 103 (20%) | 68 (13%) | |

| Stable Disease | 40 (8%) | 34 (7%) | |

| Progressive Disease | 1 (<1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Unevaluable/Insufficient | 42 (8%) | 36 (7%) | |

| Rates | N (%) | N (%) | Chi sq p-value |

| MRD Negative | 38 (7%) | 54 (10%) | p=0.08 |

| (95% CI) | (5%−10%) | (8%−13%) | |

| CR | 78 (15%) | 96 (18%) | p=0.13 |

| (95% CI) | (12%−18%) | (15%−22%) | |

| VGPR | 341 (65%) | 388 (74%) | p<0.01 |

| (95% CI) | (61%−69%) | (70%−77%) | |

| PR | 444 (84%) | 456 (87%) | p=0.26 |

| (95% CI) | (81%−87%) | (84%−90%) | |

With median (IQR) OS follow-up of 26 (15–39) months [24 (15–38) for the VRd arm and 27 (15–40) for the KRd arm], 148 (14%) of 1087 enrolled patients have died; 73 (14%) of 542 VRd patients and 75 (14%) of 545 KRd patients (Figure 2b). The KM estimate for 3-year OS probability is 0·84 (95% CI 0·80–0·88) for VRd and 0·86 (95% CI 0·82–0·89) for KRd. The median OS has not been reached in either arm; patients continue on long term follow up for overall survival. The hazard ratio for death in the KRd arm compared to the VRD arm was 0·98 (95% CI 0·71–1·36); P=0·92.

All 1053 treated patients (527 in the VRd arm and 526 in the KRd arm) were assessed for adverse events. More grade 3 or higher non-hematologic treatment-related adverse events (TRAE) were observed in the KRd arm with 254 (48%; 95% CI 44%−53%) of 527 treated KRd patients versus 218 (41%; 95% CI 37%−46%) of 526 treated VRd patients (appendix p35)· Grade 3 or higher TRAE reported in at least 1% of patients during induction are shown in Table 3. Grade 4–5 hematologic plus non-hematologic TRAEs were reported in 61 (12%) of treated VRd patients and 70 (13%) of treated KRd patients (appendix p35). Full details of all treatment-emergent AEs in a minimum of 1% of patients on either arm are reported in the appendix (p37). A grade 3 or higher composite CPR toxicity was noted among 84 (16%) KRd treated patients compared with 25 (5%) of VRd treated patients, p<0·001; including 5 deaths with KRd and 1 with VRd and led by the difference in frequency of dyspnea and heart failure (appendix p40). As shown in the appendix (p42), treatment-related non-hematologic toxicity rates were higher in older patients but the difference in CPR rates between age subgroups dichotomized at 70 years was not as substantial. Grade 3–5 serious adverse events were reported in 116 (22%) of the 527 treated patients in VRd arm and in 234 (45%) of the 526 treated patients in KRd arm (appendix p43). Overall, 91 (17.3%) patients in the VRd arm and 52 (9.9%) patients in the KRd arm discontinued therapy for adverse events. There were 25 deaths unrelated to disease progression per protocol during induction (9 VRd and 16 KRd), including 13 (2 VRd and 11 KRd) considered treatment related (appendix p43); causes of death are as in appendix p44. Overall, causes of death in the VRd arm included sepsis (3), disease progression (1), myocardial infarction (1), myelodysplastic syndrome (1), acute kidney injury (1), second neoplasm (1), and cardiac arrest (1) while in the KRd arm respiratory failure (3), thromboembolic event (2), acute kidney injury (2), myocardial infarction (1), hepatic failure (1), sinus bradycardia (1), hypoxia (1), lung infection (1), sudden death nos (1), sinus bradycardia (1), cardiac arrest (1) and stroke (1) were the reported causes of death.

Table 3.

Induction Treatment-Related Non-Hematologic Toxicity

| Adverse Event Type^ | Treatment Arm | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VRd (n=527) | KRd (n=526) | |||||

| Grade | Grade | |||||

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Febrile neutropenia | 2 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) | - | 5 (1%) | 1 (<1%) | - |

| Atrial fibrillation | 2 (<1%) | - | - | 7 (1%) | - | - |

| Heart failure | 6 (1%) | - | - | 14 (3%) | 5 (1%) | - |

| Myocardial infarction | 1 (<1%) | - | 1 (<1%) | 3 (1%) | 1 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) |

| Diarrhea | 22 (4%) | 1 (<1%) | - | 16 (3%) | - | - |

| Nausea | 5 (1%) | - | - | 4 (1%) | - | - |

| Fatigue | 34 (6%) | - | - | 29 (6%) | - | - |

| Edema limbs | 11 (2%) | - | - | 12 (2%) | - | - |

| Infusion related reaction | - | - | - | 3 (1%) | 3 (1%) | - |

| Infections and infestations - Other | 5 (1%) | - | - | 2 (<1%) | - | - |

| Sepsis | - | 3 (1%) | - | - | 9 (2%) | - |

| Skin infection | 3 (1%) | - | - | 5 (1%) | - | - |

| Lung infection | 9 (2%) | - | - | 27 (5%) | - | - |

| Creatinine increased | 2 (<1%) | - | - | 6 (1%) | 1 (<1%) | - |

| Weight loss | 5 (1%) | - | - | 3 (1%) | - | - |

| Ejection fraction decreased | - | - | - | 8 (2%) | 1 (<1%) | - |

| Anorexia | 5 (1%) | - | - | 2 (<1%) | - | - |

| Dehydration | 9 (2%) | - | - | 4 (1%) | - | - |

| Hyperglycemia | 18 (3%) | 5 (1) | - | 29 (6%) | 5 (1%) | - |

| Hypokalemia | 5 (1%) | - | - | 7 (1%) | 1 (<1%) | - |

| Hyponatremia | 7 (1%) | 1 (<1) | - | 6 (1%) | 1 (<1%) | - |

| Back pain | 5 (1%) | - | - | 1 (<1%) | - | - |

| Pain in extremity | 5 (1%) | - | - | - | - | - |

| Generalized muscle weakness | 12 (2%) | - | - | 3 (1%) | - | - |

| Dizziness | 7 (1%) | - | - | - | - | - |

| Peripheral motor neuropathy | 5 (1%) | - | - | 1 (<1%) | - | - |

| Peripheral sensory neuropathy | 39 (7%) | - | - | 3 (1%) | - | - |

| Syncope | 8 (2%) | - | - | 5 (1%) | - | - |

| Insomnia | 12 (2%) | - | - | 11 (2%) | - | - |

| Acute kidney injury | 3 (1%) | - | - | 9 (2%) | 4 (1%) | 1 (<1%) |

| Dyspnea | 9 (2%) | - | - | 32 (6%) | 6 (1%) | - |

| Hypoxia | 2 (<1%) | - | - | 6 (1%) | 1 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) |

| Pneumonitis | 2 (<1%) | - | - | 5 (1%) | - | - |

| Respiratory failure | - | - | - | - | 5 (1%) | - |

| Rash acneiform | 10 (2%) | - | - | 12 (2%) | - | - |

| Rash maculo-papular | 7 (1%) | - | - | 18 (3%) | - | - |

| Hypertension | 11 (2%) | - | - | 21 (4%) | 1 (<1%) | - |

| Hypotension | 11 (2%) | - | - | 6 (1%) | - | - |

| Thromboembolic event | 7 (1%) | 4 (1%) | - | 23 (4%) | 3 (1%) | - |

| WORST DEGREE | 197 (37%) | 20 (4%) | 1 (<1%) | 211 (40%) | 36 (7%) | 7 (1%) |

Grade 3–5 non-hematologic adverse events at least possibly attributable to treatment occurring at least 1% in either arm

Excluding non-invasive cancers, there were 14 and 18 cases of second primary cancers in the VRd and KRd arms, respectively (appendix p45). The 3-year cumulative incidence rates for invasive second primary cancers were 3·6% in 527 treated VRd patients compared with 3·6% in 526 treated KRd patients (appendix p19).

Bortezomib was dose reduced in 245 (46%) of 527 treated patients and carfilzomib was dose reduced in 174 (33%) of 526 treated patients (appendix p27). Regarding dose intensity, 130 (57%) of 229 patients on bortezomib by end of induction cycle 12 received over 75% of planned bortezomib dose versus 204 (64%) of 320 patients on carfilzomib by end of induction cycle 9 (appendix p28). Exposure classification for lenalidomide and dexamethasone by induction cycle is also provided (appendix pp29–30). Mean dose intensity for all drugs over induction is also provided in (appendix pp13–15).

The QoL compliance rate by the end of induction was 97% (539 of 552 patients reaching that timepoint). The trends in the scores are as shown in appendix pp20–24 and pp46–48. No difference was observed between the arms in terms of the physical or functional well-being scores or MM specific symptom scores over induction treatment, with scores demonstrating stability to slight improvement in both groups. Some decrease was noted on the neurotoxicity scores in VRd arm. Scores from the FACT-NTx TOI scale showed a decrease by end of cycle 4 on VRd arm (12 weeks) compared with KRd, maintained similar difference at end of cycle 8 (24 weeks), and then started improving by end of induction (36 weeks) (primary QoL endpoint p=0.09).

DISCUSSION

Results of the current trial show that KRd is not superior to VRd for initial treatment of newly diagnosed standard or intermediate risk MM in patients who are ineligible for ASCT or did not intend to have early ASCT. Progression free survival was similar between the two regimens, as was the overall survival at 3 years. While overall response rates were comparable between the regimens, deeper responses occurred more often with KRd. Grade 3 or higher toxicities were seen more often with KRd, and was associated with more cardiac, pulmonary and renal toxicity while VRd was associated with more neurotoxicity. There were more on study deaths with KRd compared to VRd. To our knowledge, this is the first randomized trial to compare KRd to VRd in patients with NDMM. Unlike many recent randomized trials in MM that have examined addition of a new drug to existing doublet combinations (comparing 3 versus 2 drugs), this trial directly compares two 3-drug combinations with the goal of informing clinical practice.

Based on a prior single arm phase 2 studies of KRd in NDMM, we had anticipated that KRd will improve outcomes compared to VRd. In a phase 2 trial of 53 patients with NDMM, 78% of patients completing 8 or more cycles of KRd achieved near CR or better, and 61% had stringent CR.13 The 24-month PFS estimate was 92%. In another phase 2 study of 45 patients, the best overall response rate was 98%, and CR rate was 67%. The median PFS was 67 months.22 Similar excellent response rates were also noted with KRd in the randomized phase 2 FORTE trial. Importantly, grade 3 or higher non-hematological toxicity was more frequent with KRd. The ORR, VGPR or better rates, and PFS for VRd in the current trial resemble the SWOG S0777 clinical trial and to the non-transplant arm of the IFM2009 trial, while that of KRd were less than expected based on phase 2 trials. A strict comparison is not possible given the patient characteristics in the current trial with the exclusion of certain high-risk patients. One might have anticipated a longer PFS for VRd in the current trial with exclusion of the high-risk patients, but the patients in the current trial were older than in both S0777 and IFM2009, at least partly explaining this finding. Even though the VGPR or better rate was significantly higher with KRD, this did not translate into improvements in the PFS. This likely reflects the impact of the toxicity related to therapy which may have led to delays in treatment and dose modifications compromising the overall efficacy. It is very likely that the smaller phase 2 trials of KRd included highly selected patients, at academic centers with better expertise at managing carfilzomib related toxicities. Results from the current trial, performed largely in community-based oncology practices, provide a better assessment of the real-world efficacy of these regimens. The comparable results seen in the younger and older patient group in the current trial with a median age of 65 years, reflective of the overall myeloma patient population, clearly demonstrates no advantage for replacing bortezomib with carfilzomib in either age-group.

The results of prior comparisons of carfilzomib with bortezomib have produced conflicting results. In the ENDEAVOR trial, carfilzomib combined with dexamethasone appeared superior to bortezomib and dexamethasone, but this trial used a higher dose of carfilzomib than was used in the initial trials.23 The results we observe here compares well with the observations from the CLARION trial, where carfilzomib was compared to bortezomib in an older transplant ineligible population, but in combination with melphalan and prednisone. In that study, with comparable number of patients enrolled, no benefit was seen with carfilzomib over bortezomib in terms of response rates or progression free survival outcomes.15

The neurotoxicity observed with VRd in our trial is similar to that reported with subcutaneous bortezomib administration, with 8% of patients developing grade 3 or higher PN.8,24 We observed a higher rate of cardiopulmonary and renal toxicity with carfilzomib, consistent with the observations from the CLARION trial and other studies.25 Additionally, the death related to toxicity was higher in the KRD arm likely impacting the short- and long-term outcomes with KRd, resulting in PFS outcomes inferior to that anticipated based on prior phase II trials with more selected patients. The distribution of non-protocol therapies, including use of ASCT, did not differ between the arms suggesting that that subsequent therapy is unlikely to have confounded the results. While there was high discontinuation rate in both arms, more patients in the VRd arm discontinued therapy due to AEs or for alternative therapy, a trend akin to that seen in the CLARION trial.

Our study has some limitations. Although we did not exclude t(4;14) translocation (a known adverse prognostic factor in myeloma), we did exclude certain high risk subsets since the trial was intended for standard and intermediate risk patients, in an effort to compliment and not compete with the parallel effort led by SWOG to improve outcomes in high risk MM with more aggressive 4-drug combinations. It is possible that carfilzomib has better efficacy in high risk MM, but that remains unclear based on what we have observed here.26 Second, as in prior trials, we enrolled patients who were ineligible for ASCT or were eligible for ASCT but wished to delay to procedure until relapse.8 There was an intent to transplant at relapse in over 70% of patients, majority of who may have been transplanted in other practice settings such as in Europe. However, transplant eligibility was purely based on the investigator determination as there were no specific criteria laid out in the study. We elected to use the current approach given that nearly 50% of transplant eligible patients with NDMM in the US practice decide to defer transplant to relapse given lack of OS impact in recent phase 3 trials. Our trial therefore does not address the role of KRd as pre-transplant induction therapy. However, based on the response rate and depth of response, it seems unlikely that 3–4 cycles of induction with KRd will improve outcomes over VRd, particularly given the lack of meaningful differences with longer therapy. Third, the overall discontinuation rate was relatively high in the study with a higher proportion discontinuing induction therapy early in the VRd arm compared to the KRd arm. The higher discontinuation rate in the VRd arm did not seem to affect the PFS, which may be related to several factors, particularly the nature and severity of the adverse events. While neuropathy may have led to discontinuation of VRd, the cardiac, pulmonary and renal toxicity seen with KRd may only have led to significant dose modifications leading to reduced efficacy. It is also important to note that this was not a blinded trial and while carfilzomib was provided by the trial, bortezomib was commercially obtained thus increasing the incentive to stay on trial if on KRd arm. Another important reason is the increased deaths seen in the KRd arm. The higher discontinuation rate with VRD for alternate therapy is unlikely to have affected the results as additional sensitivity analyses using different censoring approaches do not appear to impact the PFS comparison. Finally, more follow up is needed to see if OS differences emerge.

Our results have major implications for clinical practice and further research, though it is unlikely to affect current practice outside of the US, where there has been some adoption of KRd as initial therapy based on phase 2 trial data. First, along with the previous trials, this study shows that VRd remains one of the best regimens for NDMM. It is unclear how the new triplet of daratumumab, a CD38 targeting monoclonal antibody, with lenalidomide and dexamethasone (DRd) compares to VRd.27 DRd was recently approved for the treatment of NDMM based on the MAIA trial, and has shown impressive results. We need randomized trials comparing these two triplet regimens. Second, despite these results, we still need to improve on outcomes for NDMM. Efforts are underway to develop quadruplet regimens that contain a monoclonal antibody such as daratumumab.28,29 Finally, our results highlights the need to wait for randomized trial results before moving into clinical practice based on data from single-arm studies.30 Given the efficacy, safety, convenience, and cost, VRd should remain the standard of care for newly diagnosed patients considered for treatment with a PI-IMiD-based triplet, as well as the backbone to build quadruplet regimens.

Supplementary Material

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT.

Evidence before this study

We searched PubMed, MEDLINE, Embase, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and references from relevant articles with the search terms “untreated” “multiple myeloma”, “proteasome inhibitor”, “immunomodulatory drug”, “randomized” and “phase III”. We also reviewed all recent reviews on myeloma treatment. We included all studies written in English and published between January 1985, and December 2019. In a randomized phase 3 trial, the combination of bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (VRd) had superior progression free and overall survival compared with lenalidomide and dexamethasone, making this triplet the standard initial therapy for treatment of newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Carfilzomib is a next generation proteasome inhibitor that has demonstrated high response rates and deep responses when used in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone (KRd) in small phase two clinical trials.

Added value of this study

In the current clinical study, we demonstrate that replacing bortezomib in the VRd triplet with carfilzomib does not lead to an improved progression free survival even though the rate of deeper responses were higher with the use of carfilzomib. We also demonstrate that carfilzomib, used in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone may be associated with higher rates of severe cardiac, pulmonary, and renal toxicities. These results will inform the clinical practice and makes the case for not routinely using carfilzomib combinations for initial treatment of standard and intermediate risk newly diagnosed myeloma.

Implications of all the available evidence

Results of the current trial supports the continued use of bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone triplet as a standard of care for initial treatment of standard and intermediate risk newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. It also suggests that future four-drug combinations incorporating newer drugs such as monoclonal antibodies should build on this triplet as the backbone.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The study was funded by NIH, NCI and Amgen.

This study was conducted by the ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group (Peter J. O’Dwyer, MD and Mitchell D. Schnall, MD, PhD, Group Co-Chairs) and supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under the following award numbers: U10CA180820, U10CA180794, UG1CA189828, UG1CA232760, UG1CA189956, UG1CA233277, UG1CA189863, U10CA180888, UG1CA233337, UG1CA189821, U10CA180821, UG1CA189858, UG1CA189956, UG1CA189830, UG1CA233340, UG1CA233163, UG1CA189957, UG1CA233247, UG1CA233180, and UG1CA233329. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations does not imply endorsement by the U.S. government. We thank the patients who volunteered to participate in this trial, their families, and the staff members at the trial sites who cared for them.

We would also like to thank Amgen, Inc. for their support of the study.

No commercial writers were involved in the manuscript writing process.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

SKK reports grants and other from Amgen, during the conduct of the study; grants and other from BMS/Celgene, grants and other from Takeda, grants and other from Abbvie, grants and other from Roche, grants from Medimmune, grants from Tenebio, grants from Carsgen, personal fees from Oncopeptides, grants and other from Janssen, outside the submitted work

SJJ has nothing to disclose

ADC reports personal fees from Celgene, personal fees from Takeda, grants and personal fees from Bristol Meyers Squibb, personal fees from Janssen, grants from Novartis, personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline, personal fees from Kite Pharma, personal fees from Oncopeptides, personal fees from Seattle Genetics, outside the submitted work.

MW has nothing to disclose

NSC has nothing to disclose.

AKS has nothing to disclose.

TLP has nothing to disclose.

AM has nothing to disclose.

AZY has nothing to disclose.

BMP reports personal fees from Amgen, personal fees from Celgene/BMS, outside the submitted work

PK has nothing to disclose

PK reports grants from Sanofi, grants from Abbvie, grants from Takeda, grants from Janssen, grants from Amgen, other from Pharmacyclics, other from Cellectar, other from Karyopharm, outside the submitted work.

ASR has nothing to disclose

JAZ reports grants from Celgene, personal fees from Takeda, personal fees from Amgen, grants from BMS, personal fees from Janssen, personal fees from Pharmacyclics, outside the submitted work.

EAF disclose personal fees from Amgen, Celgene, Kite and Janssen.

SL reports personal fees from Amgen, personal fees from Takeda, personal fees from Celgene, personal fees from BMS, personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from GSK, personal fees from Sanofi, personal fees from Janssen, outside the submitted work; and above consulting is all <5k per year per company Serve as a member of the board of directors for TG therapeutics with stock ownership.

KCA reports personal fees from Celgene, personal fees from millennium Takeda, personal fees from Gilead, personal fees from Janssen, personal fees from Sanofi-Aventis, personal fees from Bristol Myers Squibb, outside the submitted work.

PGR reports grants from BMS, grants and honoraria (advisory committee member) from Oncopeptides, Celgene, Takeda, and Karyopharm, honoraria (advisory committee member) from Janssen, Sanofi, and SecuraBio outside the submitted work.

RZO declares laboratory research funding from BioTheryX, and clinical research funding from CARsgen Therapeutics, Celgene, Exelixis, Janssen Biotech, Sanofi-Aventis, Takeda Pharmaceuticals North America, Inc. Also, RZO has served on advisory boards for Amgen, Inc., Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, EcoR1 Capital LLC, Forma Therapeutics, Genzyme, GSK Biologicals, Ionis Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Janssen Biotech, Juno Therapeutics, Kite Pharma, Legend Biotech USA, Molecular Partners, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Sanofi-Aventis, Servier, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals North America, Inc. Finally, RZO is a Founder of Asylia Therapeutics, Inc., with associated patents and an equity interest but these are outside the scope of the current research.

LIW Dr. Wagner reports personal fees from Celgene, outside the submitted work.

SVR has nothing to disclose.

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at www.thelancet.com.

DATA SHARING

The NCTN/NCORP Data Archive is a centralized, controlled-access database housing deidentified individual patient data from NCI-funded randomized phase 3 clinical trials (including randomized phase 2/3 trials that progressed to phase 3). De-identified data sets and data dictionaries, tied ot a specific publication, are transferred to the archive under a data transfer agreement made by and between the NCI and ECOGACRIN. An investigator who wishes to use an ECOG-ACRIN data set deposited in the NCTN/NCORP Data Archive must make a formal request to NCI. Guidance on how to make such a request can be found in the document “NCTN Data Archive Usage Guide” (posted at https://nctn-dataarchive.nci.nih.gov/user). An investigator who wishes to use an ECOG-ACRIN data set that is not covered by the NCTN

Data Archive must make a formal request to ECOG-ACRIN. The detailed data sharing policy of ECOG-ACRIN is available online at ECOG-ACRIN website.

Footnotes

A complete list of enrolling sites in the ENDURANCE trial is provided in the Appendix.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kumar SK, Rajkumar SV. The multiple myelomas - current concepts in cytogenetic classification and therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2018; 15(7): 409–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dimopoulos MA, Jakubowiak AJ, McCarthy PL, et al. Developments in continuous therapy and maintenance treatment approaches for patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J 2020; 10(2): 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Costa LJ, Brill IK, Omel J, Godby K, Kumar SK, Brown EE. Recent trends in multiple myeloma incidence and survival by age, race, and ethnicity in the United States. Blood Adv 2017; 1(4): 282–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar SK, Dispenzieri A, Lacy MQ, et al. Continued improvement in survival in multiple myeloma: changes in early mortality and outcomes in older patients. Leukemia 2014; 28(5): 1122–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Munshi NC, Avet-Loiseau H, Rawstron AC, et al. Association of Minimal Residual Disease With Superior Survival Outcomes in Patients With Multiple Myeloma: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol 2017; 3(1): 28–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richardson PG, Weller E, Lonial S, et al. Lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone combination therapy in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Blood 2010; 116(5): 679–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar S, Flinn I, Richardson PG, et al. Randomized, multicenter, phase 2 study (EVOLUTION) of combinations of bortezomib, dexamethasone, cyclophosphamide, and lenalidomide in previously untreated multiple myeloma. Blood 2012; 119(19): 4375–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Durie BG, Hoering A, Abidi MH, et al. Bortezomib with lenalidomide and dexamethasone versus lenalidomide and dexamethasone alone in patients with newly diagnosed myeloma without intent for immediate autologous stem-cell transplant (SWOG S0777): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017; 389(10068): 519–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Attal M, Lauwers-Cances V, Hulin C, et al. Lenalidomide, Bortezomib, and Dexamethasone with Transplantation for Myeloma. N Engl J Med 2017; 376(14): 1311–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Donnell EK, Laubach JP, Yee AJ, et al. A phase 2 study of modified lenalidomide, bortezomib and dexamethasone in transplant-ineligible multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol 2018; 182(2): 222–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joseph NS, Kaufman JL, Dhodapkar MV, et al. Long-Term Follow-Up Results of Lenalidomide, Bortezomib, and Dexamethasone Induction Therapy and Risk-Adapted Maintenance Approach in Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma. J Clin Oncol 2020: JCO1902515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuhn DJ, Chen Q, Voorhees PM, et al. Potent activity of carfilzomib, a novel, irreversible inhibitor of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, against preclinical models of multiple myeloma. Blood 2007; 110(9): 3281–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jakubowiak AJ, Dytfeld D, Griffith KA, et al. A phase 1/2 study of carfilzomib in combination with lenalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone as a frontline treatment for multiple myeloma. Blood 2012; 120(9): 1801–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Korde N, Roschewski M, Zingone A, et al. Treatment With Carfilzomib-Lenalidomide-Dexamethasone With Lenalidomide Extension in Patients With Smoldering or Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma. JAMA Oncol 2015; 1(6): 746–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Facon T, Lee JH, Moreau P, et al. Carfilzomib or bortezomib with melphalan-prednisone for transplant-ineligible patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Blood 2019; 133(18): 1953–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar S, Paiva B, Anderson KC, et al. International Myeloma Working Group consensus criteria for response and minimal residual disease assessment in multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol 2016; 17(8): e328–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1958; 53: 457–81. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mantel N Evaluation of survival data and two new rank order statistics arising in its consideration. Cancer Chemother Rep 1966; 50(3): 163–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables. J R Stat Soc [B] 1972; 34: 187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Brien PC, Fleming TR. A multiple testing procedure for clinical trials. Biometrics 1979; 35: 549–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wieand S, Schroeder G, O’Fallon JR. Stopping when the experimental regimen does not appear to help. Stat Med 1994; 13(13–14): 1453–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kazandjian D, Korde N, Mailankody S, et al. Remission and Progression-Free Survival in Patients With Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma Treated With Carfilzomib, Lenalidomide, and Dexamethasone: Five-Year Follow-up of a Phase 2 Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol 2018; 4(12): 1781–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dimopoulos MA, Moreau P, Palumbo A, et al. Carfilzomib and dexamethasone versus bortezomib and dexamethasone for patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (ENDEAVOR): a randomised, phase 3, open-label, multicentre study. Lancet Oncol 2016; 17(1): 27–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moreau P, Coiteux V, Hulin C, et al. Prospective comparison of subcutaneous versus intravenous administration of bortezomib in patients with multiple myeloma. Haematologica 2008; 93(12): 1908–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Danhof S, Schreder M, Rasche L, Strifler S, Einsele H, Knop S. ‘Real-life’ experience of preapproval carfilzomib-based therapy in myeloma - analysis of cardiac toxicity and predisposing factors. Eur J Haematol 2016; 97(1): 25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mina R, Bonello F, Petrucci MT, et al. Carfilzomib, cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone for newly diagnosed, high-risk myeloma patients not eligible for transplant: a pooled analysis of two studies. Haematologica 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Facon T, Kumar S, Plesner T, et al. Daratumumab plus Lenalidomide and Dexamethasone for Untreated Myeloma. N Engl J Med 2019; 380(22): 2104–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moreau P, Attal M, Hulin C, et al. Bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone with or without daratumumab before and after autologous stem-cell transplantation for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (CASSIOPEIA): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet 2019; 394(10192): 29–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mateos MV, Dimopoulos MA, Cavo M, et al. Daratumumab plus Bortezomib, Melphalan, and Prednisone for Untreated Myeloma. N Engl J Med 2018; 378(6): 518–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kapoor P, Rajkumar SV. MAIA under the microscope - bringing trial design into focus. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2019; 16(6): 339–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.