Abstract

In a single day, six of 150 (4%) asymptomatic visitors were diagnosed with COVID-19 at a hospital with a universal masking policy. Two inpatients (contacts) subsequently developed symptoms. More rigorous protective measures during visitation periods may need to be included in infection control practices to reduce nosocomial transmissions.

Keywords: Visitors, Nosocomial, Sarscov2, Universal mask, Asymptomatic

Introduction

The burden of asymptomatic Coronavirus Disease-2019 (COVID-19) on clinical practice and epidemiological control remains a challenge, particularly due to the high potential of transmission (Al-Sadeq and Nasrallah, 2020, Arons et al., 2020). While several nosocomial outbreaks have been reported (Arons et al., 2020, Roxby et al., 2020), most studies focused on the role of asymptomatic hospitalized patients (Passarelli et al., 2020, Rhee et al., 2020). However, hospital visitors’ impact on viral shedding in healthcare facilities remains underestimated.

Methods

On August 29th, 2020, visitors of hospitalized patients at São Paulo Hospital in São Paulo, Brazil, were enrolled for COVID-19 screening with reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) on nasopharyngeal specimens.

All subjects were assessed for COVID-19 symptoms (including fever [≥37.8 °C], cough, anosmia, dysgeusia, dyspnea, myalgia, headache, and nasal discharge) and were asymptomatic at enrollment. This hospital receives around 150 visitors daily, and COVID-19 restrictions had been implemented: only one visitor per patient was allowed. According to universal masking policies, all visitors and patients had to wear face masks (cloth or surgical), as did the healthcare staff (surgical). Since no visitor was symptomatic of COVID-19 and had no known exposure to confirmed cases, visitations were normally allowed, and outcomes were subsequently monitored via telephone until test results were obtained. If positive, they were assessed for symptoms and alert signs and oriented accordingly. Relevant clinical information was collected at the time of enrollment. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee from the Federal University of São Paulo, and all individuals signed written informed consent forms.

Samples’ RNA was purified with Quick-RNA Viral Kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA), and viral detection was performed with AgPath-ID One-Step RT-PCR reagents (ThermoFisher Scientific, Austin, TX, USA), according to manufacturers’ instructions. A 20 μL total reaction volume containing 5.0 μL purified RNA, 400 nM primers, and 200 nM probes following the CDC USA protocol targeted the N1 and N2 sequences of the SARS-CoV-2 nucleoprotein gene (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020b), with a sensitivity of 75–80% (Alcoba-Florez et al., 2020). Cycle thresholds <40 were considered positive.

Data were summarized as percentages and medians (ranges); 95% confidence intervals were calculated via the binomial method using Free Statistics Software (version 4.0).

Results

One hundred and fifty asymptomatic visitors were screened for COVID-19. The median age was 39 years (range, 15–75), and 109 (72,6%) were women. Five individuals (3,33%) had previously been diagnosed with COVID-19.

Six asymptomatic visitors (4%, 95% CI, 1,48%–8,50%) had a positive RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2 (Table 1 ). Four of them (66,7%) were asymptomatic until assessment fourteen days after testing. One patient (16,6%) developed mild symptoms the following day, and the other (16,6%) had been diagnosed with COVID-19 by RT-PCR twenty days prior but remained positive despite no residual symptoms. Two visited patients (33,3%) developed symptoms on the following day and had COVID-19 confirmed by RT-PCR, but were discharged without complications. The other four patients/contacts (66,6%) were not infected on this occasion.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of asymptomatic hospital visitors screened for COVID-19 and their contacts’ outcomes (inpatients).

| Visitor | Age, years | Gender | Previous COVID-19 | Symptoms afterward | Visited Inpatient’s Outcome After Contact | Visited inpatient’s length of stay, days |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 16 | Female | No | Yesa | Discharge | 1 |

| 2 | 26 | Female | No | No | Discharge | 1 |

| 3 | 33 | Female | Yes | No | Dischargeb | 5 |

| 4 | 21 | Male | No | No | Discharge | 1 |

| 5 | 34 | Male | No | No | Dischargeb | 10 |

| 6 | 56 | Male | No | No | Discharge | 1 |

Patient presented headache on the following day, without other symptoms.

Diagnosed with nosocomial COVID-19.

Discussion

While most studies have focused on the role of both symptomatic and asymptomatic COVID-19 for nosocomial infections (Passarelli et al., 2020, Rhee et al., 2020), our study shows a possible contribution by visitors to viral shedding in healthcare facilities.

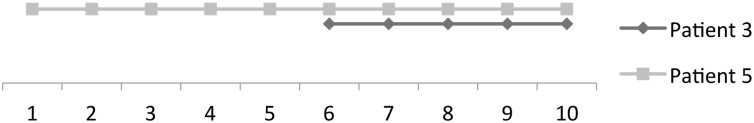

Contacts of visitors 3 and 5 (Table 1) were also diagnosed with COVID-19, so this was considered a possible source of exposure, despite the use of face covering. The repetitive contact during visitations on multiple occasions possibly accounted for higher risk in these cases (Figure 1 ). Moreover, visitor 3 was the patient’s spouse and had been diagnosed twenty days prior, without residual symptoms at the time of enrollment in this study. There was close contact between them before and during hospitalization. One possibility is that transmission happened beforehand since longer incubation periods and transmission from asymptomatic individuals have been reported (Al-Sadeq and Nasrallah, 2020). Although it is not possible to completely exclude transmissions related to other patients or hospital staff (Al-Sadeq and Nasrallah, 2020, Arons et al., 2020, Roxby et al., 2020, Passarelli et al., 2020), no other contacts developed symptoms before or afterward.

Figure 1.

Squares and rhombi represent the periods of visitation/exposure (30 min each day) during hospitalization days for patients 3 and 5. Visitors of both patients tested positive on day nine. Patients developed symptoms on day ten.

Healthcare-related outbreaks of COVID-19 have been reported (Arons et al., 2020, Roxby et al., 2020) mostly when institutions had not implemented adequate infection control measures (Rhee et al., 2020). A recent large US study showed a low incidence of hospital-acquired COVID-19 (Rhee et al., 2020). However, nosocomial infections still occur and may be closely related to asymptomatic and presymptomatic individuals' potential for transmission (Passarelli et al., 2020).

While the implementation of universal masking does reduce transmissions (Passarelli et al., 2020, Rhee et al., 2020, Howard et al., 2020), they might also induce a false perception of protection that could lead to neglect of other critical protective measures (Howard et al., 2020). The risk of SARS-CoV-2 introduction into facilities by visitors increases, the more community transmission is widespread (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020a); therefore, the occurrence of outbreaks could be mitigated with restriction of time and physical contact during visitation periods, and reassurance of adequate and frequent hand hygiene, as well as personal protective equipment, when necessary. Active screening of visitors might need to be considered part of infection control protocols (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020a).

In summary, surveillance of asymptomatic visitors with a rigorous implementation of protective measures during visitation periods may need to be included in infection control practices to reduce transmissions in healthcare settings.

Funding

This work received support from the Brazilian Coordination<GS1> for the <GS1>Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) and the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq). No financial grants were received for the research, authorship, or publication of this work.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Local Ethics Committee (CAAE: 29429720.1.1001.5505).

Authors’ contributions

Concept, design, administration, and writing: VCP, NB. Investigation and interpretation of data: VCP, KFF, AHP, GRB, DDC, LVLM, JMAC, APC, CC, NB. Supervision: NB.

All authors approved the final version of this manuscript .

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thank Raquel Pimentel, Ane Caroline Silva de Jesus, Denilson Souza da Silva, Maria Betania Jesus, Bruna Fernandes Damas, Rute Roque Cardoso, Silvia Renata Galli for logistic assistance and support.

References

- Alcoba-Florez J., Gil-Campesino H., Artola D.G., González-Montelongo R., Valenzuela-Fernández A., Ciuffreda L. Sensitivity of different RT-qPCR solutions for SARS-CoV-2 detection. Int J Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.07.058. [E-pub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sadeq D., Nasrallah G. The incidence of the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 among asymptomatic patients: a systematic review. Int J Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.06.098. [E-pub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arons M.M., Hatfield K.M., Reddy S.C., Public Health–Seattle and King County and CDC COVID-19 Investigation Team Presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections and transmission in a skilled nursing facility. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(22):2081–2090. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2008457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; Atlanta, GA: 2020. Management of Visitors to Healthcare Facilities in the Context of COVID-19: Non-US Healthcare Settings. [Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/non-us-settings/hcf-visitors.html#visitors-healthcare-facilities] [Google Scholar]

- https://www.fda.gov/media/134922/downloadCenters for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC 2019-Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Real-Time RT-PCR Diagnostic Panel. [Available at: .].

- Howard J., Huang A., Li Z., Tufekci Z., Zdimal V., van der Westhuizen H. Face masks against COVID-19: an evidence review. Preprints. 2020 doi: 10.20944/preprints202004.0203.v1. 2020040203 [E-pub] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passarelli V.C., Faico-Filho K., Moreira L., Luna L., Conte D., Camargo C. Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections in hospitalized patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020:1–9. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee C., Baker M., Vaidya V. Incidence of nosocomial COVID-19 in patients hospitalized at a large US academic medical center. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.20498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roxby A.C., Greninger A.L., Hatfield K.M. Outbreak investigation of COVID-19 among residents and staff of an independent and assisted living community for older adults in Seattle, Washington. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(8):1101–1105. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]