Abstract

Background

Alcohol is a well-established risk factor for head and neck cancer (HNC). This study aims to explore the effect of alcohol intensity and duration, as joint continuous exposures, on HNC risk.

Methods

Data from 26 case-control studies in the INHANCE Consortium were used, including never and current drinkers who drunk ≤10 drinks/day for ≤54 years (24234 controls, 4085 oral cavity, 3359 oropharyngeal, 983 hypopharyngeal and 3340 laryngeal cancers). The dose-response relationship between the risk and the joint exposure to drinking intensity and duration was investigated through bivariate regression spline models, adjusting for potential confounders, including tobacco smoking.

Results

For all subsites, cancer risk steeply increased with increasing drinks/day, with no appreciable threshold effect at lower intensities. For each intensity level, the risk of oral cavity, hypopharyngeal and laryngeal cancers did not vary according to years of drinking, suggesting no effect of duration. For oropharyngeal cancer, the risk increased with durations up to 28 years, flattening thereafter. The risk peaked at the higher levels of intensity and duration for all subsites (odds ratio = 7.95 for oral cavity, 12.86 for oropharynx, 24.96 for hypopharynx and 6.60 for larynx).

Conclusions

Present results further encourage the reduction of alcohol intensity to mitigate HNC risk.

Subject terms: Risk factors, Diseases

Background

Worldwide, harmful alcohol consumption causes 3 million deaths each year (5% of all deaths), and it is responsible for ~5% of the global burden of disease and injury.1 In particular, alcohol consumption has been consistently associated with cancer risk at several sites.2 Together with tobacco smoking, alcohol drinking is one the major risk factors for head and neck cancer (HNC), and it is responsible for approximately one third of the cases worldwide.3,4

Epidemiological studies firmly established a clear dose-response relationship between ethanol intake and HNC risk.5,6 However, alcohol drinking has two related dimensions impacting on health outcomes: besides the quantity of alcohol consumed, time-related patterns of consumption, such as age at starting and duration, have a relevant role1 and they may modify the reported association between drinking intensity and cancer risk. Notably, a joint effect of intensity and duration on cancer risk has already been reported for tobacco smoking in HNC7,8 and in other tobacco-related cancers.9–11

In a previous analysis from the International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology (INHANCE) consortium including 15 studies,7 the independent contribution of drinking intensity and duration was estimated through the calculation of drink-years. Similarly to pack-years for tobacco smoking, drink-years represent the lifetime cumulative exposure to alcohol, and it was obtained by multiplying intensity (in drinks/day) by duration (in years). Then, the effect of duration on HNC risk was estimated analysing the risk for drink-years within fixed categories of intensity; this analysis reported an independent effect of drinking duration for all HNC subsites.7

In the absence of a clear relationship between alcohol intensity and duration on the risk of HNC, we investigated their joint effect on the INHANCE database using an extension of the bivariate spline model presented in a previously published analysis on cigarette smoking.8 Differently from the previous INHANCE paper,7 this model allows risks to vary for different combinations of drinking intensity and duration, even when the cumulative drink-years exposure is the same. We will address the following research questions: (1) What are the relationships between intensity and duration of alcohol drinking and the risk of cancer at HNC subsites? (2) Do drinking intensity and duration have a similar impact on HNC risk? (3) Are there meaningful values of drinking intensity or duration where the risk pattern changes?

Methods

The INHANCE Consortium was established in 2004 to elucidate the aetiology of HNC through pooled analyses of individual-level data from several studies on a large scale.12,13 It included invasive cancer cases of the oral cavity, oropharynx, hypopharynx, oral cavity or pharynx not otherwise specified, larynx or unspecified HNC. Cases with cancers of the salivary glands or of the nasal cavity/ear/paranasal sinuses were excluded.14

At the time of this analysis, the INHANCE database (version 1.5) included 25,716 HNC cases and 37,111 controls (http://www.inhance.utah.edu, last access 25 May 2020). The present analysis was restricted to 26 case-control studies (21,384 HNC cases; 30,651 controls) that collected information on alcohol drinking status (i.e. never, former and current), intensity (number of drinks/day) and duration (years) at individual level (Supplementary Table S1).15–40 Cancer sites were grouped according to similar major aetiology: oral cavity (ICD10 codes: C02–C06; n = 6249), oropharynx (ICD10: C01, C09–C10; n = 5499), hypopharynx (ICD10: C13; n = 1798), and larynx (ICD10: C32; n = 5620). The following exclusion criteria were applied: (a) cancers arising in sites other than those mentioned above, or mixed cancer subsites (2218 subjects); (b) missing information on drinking status, intensity or duration (2247 subjects); (c) being former drinkers (i.e. having stopped drinking for at least 1 year before cancer diagnosis or interview for controls; 6993 subjects), as these subjects are more likely to stop drinking for reasons related to medical conditions;41 (d) missing information on major covariates, namely sex, age, education, ethnicity (92 subjects) or on cigarette-smoking status, intensity or duration (392 subjects) (see the flow-chart in Supplementary Fig. S1). In 15 studies15–17,19,21,22,24,25,27,28,33,34,37,38,40 controls were selected among cancer-free patients admitted to hospital for non-oncologic reasons, whereas controls were from the general population in nine studies;18,20,23,29–32,36,39 two multicentre studies26,35 enrolled a combination of hospital and population controls.

To prevent potential estimation distortion due to sparse data or misclassification at the highest levels of the exposure distributions, we further excluded subjects who reported the highest 5% of drinking intensity (i.e. >10 drinks/day) or duration (i.e. >54 years); consequently, 2455 HNC cases (17.3%) and 1637 controls (6.3%) were excluded. Finally, the current analysis included 4085 individuals with cancers of the oral cavity, 3359 oropharynx, 983 hypopharynx, 3340 larynx and 24,234 controls (Supplementary Table S2). For those studies reporting a case-control matching, separate sets of controls were matched for the three cancer subsites. Informed consent was obtained from all study subjects (Supplementary Table S1). The investigations were approved by the relevant Boards of Ethics, according to the regulation in force at time the data were collected.

Available data were harmonised at the Study Coordinating Center.14 While different studies had used different definitions of alcohol drinking status, the current paper defined as never drinkers those individuals who have never had any alcohol (0 ml of ethanol or 0 drinks over lifetime) or were defined as never drinkers by the individual studies. A similar definition was adopted for smoking habits.8 Study subjects were asked to report their drinking habits (drinking status, intensity and duration). Drinking intensity was then expressed in drinks/day of alcoholic beverages. To account for variation of ethanol content across alcoholic beverages and across countries, intensity was harmonised on a standard drink, corresponding to 15.6 ml (i.e. 12 g) of ethanol, weighting intensity by study-specific beverages volume and ethanol intake.14 Average lifetime alcohol intake was calculated as the total intake of wine, beer and hard liquor, taking into account possible intensity modification or quitting periods occurring in subjects’ life. Duration of alcohol drinking was calculated as the period of time between the subject’s age at the start of drinking any alcoholic beverages and the age at cancer diagnosis (or interview, for controls), discarding periods when the subject abstained from any alcoholic beverages.

The dose-response relationship between cancer risk and the joint exposure to alcohol drinking intensity and duration in current drinkers was investigated through bivariate regression spline models,42 as described elsewhere.8,43 In contrast to drink-years, this method allows risks to vary for different combinations of the two continuous exposures intensity and duration, even when the cumulative drink-year exposure is the same (i.e. people drinking 1 drink/day for 10 years are allowed to have a different risk than those drinking 10 drinks/day for one year). Briefly, within a generalised semi-parametric logistic regression model, the two exposures were entered as a joined piecewise polynomial of a linear degree with constraints for continuity at each join point (called knot), together with potential confounders. Knots represented change points, where the slope of the risk surface changes to account for potential departures from linearity. The set of spline regression parameters described the shape of the risk surface. For each cancer subsite, the optimal number of knots, their location, the regression and spline coefficients were jointly estimated within the Bayesian approach.43 Vague prior distributions were assumed on the regression and spline coefficients, with spike-and-slab priors on the spline coefficients managing the choice of the optimal number of knots within a modified Stochastic Search Variable Selection approach.44 The Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC)-type NUTS (No-U-Turn Sampler) algorithm8,45,46 allowed to implement the Stochastic Search Variable Selection approach for identifying the optimal number of knots and then to derive the final joint posterior distribution of all the parameters, with the optimal combination of number of knots previously identified. Convergence was tested by algorithm-specific and generic MCMC diagnostics, reporting low number of divergences, a R-hat statistic <1.05 for each parameter, and a generally high effective sample size, suggesting the chains efficiently explored the posterior distribution. For each subsite, the ORs and their 95% credible intervals (CIs) were derived from the corresponding (final) posterior distribution. The ORs were presented through three-dimensional plots that displayed the surface of risk for any combination of alcohol drinking intensity and duration. In addition, we presented two-dimensional plots that displayed patterns of risks corresponding to one variable exposure for fixed levels of the other exposure. All the models were fitted with the full set of potential confounders, i.e. sex, age, study, race, education, cigarette-smoking status, cigarette-smoking intensity, cigarette-smoking duration and pipe and cigar status (Supplementary Table S2); “Never drinkers” were assumed as the reference category. Calculations were carried out using the open-source Stan program47 within the open-source R program.48

Results

Study subjects were predominantly males (70.7%); the median age was 58 years for controls and for all cases together. Current smoking was reported in the majority of cancer patients (51.5% of oral cavity, 52.4% of oropharyngeal cancers, 63% of hypopharyngeal and 61.2% of laryngeal cancers), but not in the controls (24.2%; Supplementary Table S2).

In the study population (Table 1), patients with cancer of the oral cavity who were current drinkers drank at higher intensities (but not for a longer time period) than controls. The proportion of never drinkers was much lower among patients with oropharyngeal (17.4%), hypopharyngeal (8.9%) and laryngeal (17.8%) cancers; drinking habits in these cancers showed a higher intensity and a longer duration.

Table 1.

Distribution of cases of oral cavity, oropharyngeal, hypopharyngeal and laryngeal cancers, and controls according to intensity and duration of alcohol drinking in current drinkers.

| Controls | Oral cavity | Oropharynx | Hypopharynx | Larynx | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | |

| Total | 24,234 | 4085 | 3359 | 983 | 3340 | |||||

| Never drinkers | 7873 | (32.5) | 1353 | (33.1) | 583 | (17.4) | 87 | (8.9) | 593 | (17.8) |

| Drinking intensity (drinks/day) | ||||||||||

| ≤1 | 6921 | (28.6) | 757 | (18.5) | 801 | (23.8) | 105 | (10.7) | 583 | (17.5) |

| >1–3 | 5470 | (22.6) | 805 | (19.7) | 787 | (23.4) | 242 | (24.6) | 771 | (23.1) |

| >3–10 | 3970 | (16.4) | 1170 | (28.6) | 1188 | (35.4) | 549 | (55.8) | 1393 | (41.7) |

| Drinking duration (years) | ||||||||||

| 1–30 | 6218 | (25.7) | 975 | (23.9) | 889 | (26.5) | 217 | (22.1) | 647 | (19.4) |

| 31–40 | 5061 | (20.9) | 920 | (22.5) | 1049 | (31.2) | 337 | (34.3) | 986 | (29.5) |

| 41–54 | 5082 | (21.0) | 837 | (20.5) | 838 | (24.9) | 342 | (34.8) | 1114 | (33.4) |

| Age at start drinking (years) | ||||||||||

| ≤18 | 5482 | (22.6) | 1047 | (25.6) | 1172 | (34.9) | 324 | (33.0) | 1050 | (31.4) |

| 19–25 | 7016 | (29.0) | 1110 | (27.2) | 1126 | (33.5) | 423 | (43.0) | 1209 | (36.2) |

| 26–35 | 2435 | (10.0) | 332 | (8.1) | 328 | (9.8) | 106 | (10.8) | 331 | (9.9) |

| >35 | 1428 | (5.9) | 243 | (5.9) | 150 | (4.5) | 43 | (4.4) | 157 | (4.7) |

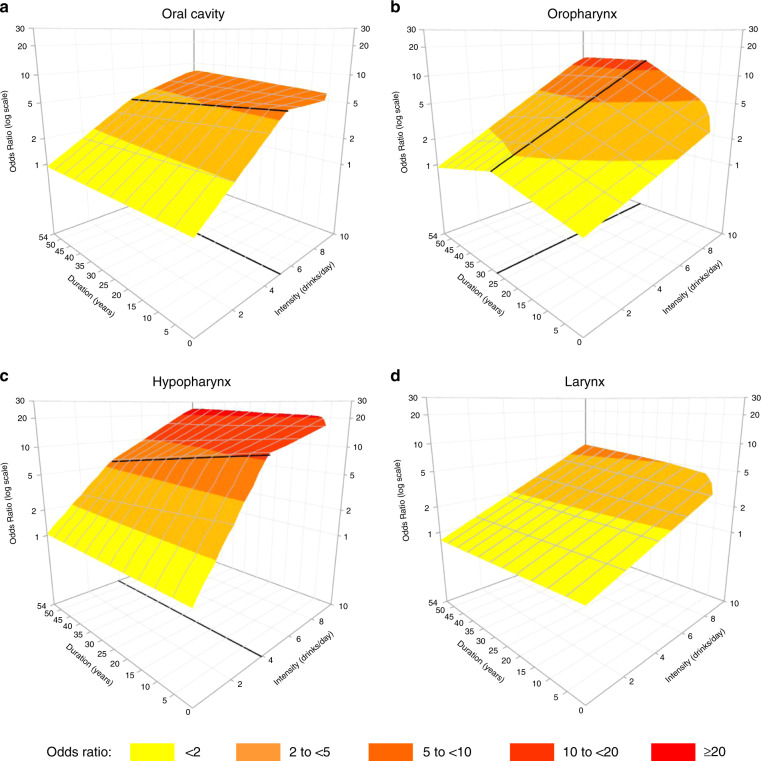

The surfaces of HNC risk for the joint exposure to drinking intensity and duration were displayed in Fig. 1. For all subsites, the risk steeply increased with increasing number of drinks/day, with no appreciable threshold effect at lower intensities. The risk peaked at the higher levels of duration and intensity (i.e. for people drinking 10 drinks/day for 54 years) for all subsites, reaching ORs of 8.0 (95% CI: 4.6–13) for oral cavity, 12.9 (95% CI: 7.2–23.7) for oropharynx, 25.0 (95% CI: 11.6–51.5) for hypopharynx and 6.6 (95% CI: 4.9–9) for larynx. For oral cavity (Fig. 1a) and hypopharynx (Fig. 1c), the risk flattened after 5 and 4 drinks/day, respectively. Moreover, the risk surfaces for cancers of the oral cavity, hypopharynx and larynx (Fig. 1a, c, and d) suggested no effect of drinking duration in addition to intensity: the risk remained stable when duration increased, for fixed levels of intensity. For oropharyngeal cancer (Fig. 1b), the risk increased with increasing years of duration up to 28 years, flattening thereafter; this effect was more marked at higher intensities. A sensitivity analysis conducted excluding only extremely high values (i.e. intensity >28 drink/day or duration >61 years, 1% of study subjects) showed similar results. The same analyses were further conducted in strata of gender (Supplementary Fig. S2): risk surfaces were similar in shape to those in the main analysis, even if cancer risk was slightly higher for women than for men. The subgroup analysis was not performed for the hypopharynx subsite, due to low number of cases.

Fig. 1. Cancer risk for the joint exposure to drinking intensity and duration (3D representation).

Bivariate spline model’s estimates of odds ratios of oral cavity (a), oropharyngeal (b), hypopharyngeal (c), and laryngeal (d) cancers in current drinkers for the joint effect of intensity and duration of alcohol consumption. On the grid, black thicker lines represent knot locations, at 5 drinks/day for oral cavity, at 4 drinks/day for hypopharyngeal cancer and at 28 years for oropharyngeal cancer.

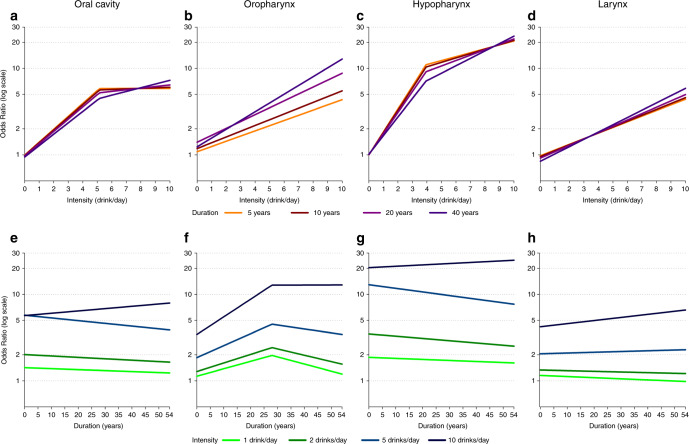

The same effects between alcohol intensity and duration across HNC subsites are also shown in Fig. 2, which presents the risk for increasing intensities at defined duration levels (upper panels), and the risk for increasing durations at defined levels of intensity (lower panels). For cancers of the oral cavity, hypopharynx, and larynx (Fig. 2a, c, and d), the curves for intensity at different durations were largely overlapping and showed an upward trend. This indicated that duration did not substantially modify cancer risk, which was mainly driven by drinking intensity. Figure 2e, g, and h confirmed this conclusion, showing generally flat curves for the three levels of intensities up to 5 drinks/day, as also suggested by the CIs (Supplementary Table S3); a modest upward trend was present at the highest intensity level (i.e. 10 drinks/day). Differently, a joint effect of intensity and duration was found for oropharyngeal cancer risk: the risk increased with increasing intensities, but higher levels of duration raised up the curves to the highest risk (Fig. 2b); duration increased oropharyngeal cancer risk up to ~28 years (Fig. 2f), although the contribution of duration to the risk was particularly evident at the highest level of intensity (i.e. 10 drinks/day).

Fig. 2. Cancer risk for the joint exposure to drinking intensity and duration (2D representation).

Bivariate spline model’s estimates of odds ratios of oral cavity, oropharyngeal, hypopharyngeal and laryngeal cancers in current drinkers for alcohol intensity and fixed levels of alcohol duration (a–d) and for duration and fixed levels of intensity (e–h).

Discussion

The present analyses show that, consistently between genders, drinking intensity was the predominant measure of alcohol affecting the risk of oral cavity, hypopharyngeal and laryngeal cancers, whereas the contribution of duration, for fixed alcohol intensities, was modest. Notably, this suggests that drinking alcohol beverages, even for a short period, increases the risk at these cancer subsites and that duration of alcohol use has little or no consistent effect on the risk of these cancers. Differently, there was a joint effect of drinking intensity and duration in determining oropharyngeal cancer risk.

The direct association between alcohol intensity and HNC risk has been extensively described2,6,49 and potential mechanisms have been proposed.5,50 Ethanol is oxidised to alcohol acetaldehyde (AA), which is a recognised carcinogen.2 Alcohol may also have a local effect, acting as a solvent of cell membranes to enhance the penetration of carcinogens, notably those from tobacco smoking, into the mucosa.50 Further, nutritional deficiencies may occur in alcoholics.50

The relationship between drinking duration and HNC risk was more complex, with a clear association with oropharyngeal cancer risk up to ~28 years of drinking. These results are in agreement with previous findings derived from a standard approach on a smaller set of INHANCE studies (15 studies) including never smokers only, which showed no association with alcohol duration in all HNC subsites but hypo/oropharynx.14 Furthermore, the application of a different statistical approach7 on the 15 INHANCE studies supported the presence of a stronger association with intensity than with duration for HNC risk. Although the lack of association with duration may seem counterintuitive, it has been reported in oesophageal adenocarcinomas, another alcohol-related cancer, in a large pooled analysis on 12 case-control studies.51 Although these results did not allow to draw biological interpretations, they suggest that alcohol intake acts as a late-stage carcinogen.52

A major limitation of the present study was information bias, which may have occurred as a consequence of the complexity of lifetime drinking patterns. Changes in the intensity, in type of alcohol beverages, and temporary quitting are more frequent for alcohol drinking than for other lifestyle habits,53 such as tobacco smoking; lifetime patterns may have an impact on the risk of cancer.54 Therefore, misclassification may have occurred for both intensity and duration. The calculation of lifetime average alcohol intake may have protected against this source of bias, thus not allowing the investigation of specific drinking patterns (e.g. infrequent heavy binge drinking). In addition, the use of linear bidimensional spline models may have contributed too, as they are quite robust with respect to small variations in the predictors, as compared to bidimensional splines of higher degrees. To test for model robustness, we adopted different solutions of truncation or approximation of drinking intensity and duration, and the resulting surface estimates were similar. Further, self-reporting of drinking habits may have led to additional information bias, since higher values of intensity and duration are more prone to inaccurate reporting.55,56 To reduce information bias and residual confounding at the extreme values of the exposure distributions, we excluded subjects reporting higher (>95th percentiles) drinking intensity and/or duration from the present analysis; however, this could have led to a reduced study power and differential exclusion of cases and controls. Finally, our Bayesian approach was computationally time consuming, requiring dedicated server devices.

Although risk estimates were adjusted for tobacco smoking (considering cigarettes, cigars and pipes), some residual confounding may remain. An analysis among never smokers would rule out possible residual confounding due to tobacco smoking. However, considering that the present logistic models includes several covariates, they require large sample sizes to produce precise estimates; thus, we were unable to conduct this subgroup analysis with sufficient precision. Nonetheless, the previously cited INHANCE analysis on never smokers14 reported results similar to the current ones, with HNC risk generally increasing with alcohol intensity and no dose-response relation with drinking duration. Further, the lack of information on infection with human papilloma virus (HPV) has to be accounted among study limitations, considering the recognised role of HPV in oropharyngeal cancer.57 Unfortunately, HPV status was not collected in the majority of studies, since they were conducted before the awareness of the HPV role in oropharyngeal cancer. International representativeness is guaranteed by the large dataset including studies from different geographical areas. On the other hand, the inclusion of heterogeneous populations, in particular that of different genetic origin, may have led to estimation bias. Compared to other populations, East Asians have a much higher frequency of A allele of ALDH2 rs671,58 which slows acetaldehyde metabolism, thus increasing alcohol-related risk. However, the exclusion of East Asian studies16,33 did not substantially modify the risk estimates.

Results of the present study are strengthened by the availability of information on several potential confounding factors. In addition, we applied a Bayesian approach to jointly estimate the optimal knot locations and the ORs of HNC for the joint effect of our continuous predictors.8 As compared to the companion paper on cigarette-smoking intensity and duration, in the current application the optimal number of knots was estimated within a two-step procedure including the Stochastic Search Variable Selection approach.43 To our knowledge, this is the first time that a similar approach is applied within the context of spline models in epidemiology.

In conclusion, findings of the present study indicate that the risk of cancer of the oral cavity, hypopharynx and larynx increases with drinking intensity, whereas the role of duration is complex. The trend is linear for larynx, but it showed a plateau at the highest intensity for cancer of the oral cavity and hypopharynx. The joint effect of intensity and duration increases the risk of oropharyngeal cancer. In addition, no threshold effect is evident at the lowest doses. Although abstinence from alcohol drinking would be the ultimate goal to reduce HNC incidence, these findings suggest that any reduction in alcohol intake59 would be an effective strategy to mitigate HNC risk, as well as the risk of few other neoplasms.60

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Xavier Castellsague, who collected data in the IARC International Multicenter study and passed away in 2016. We thank Mrs Luigina Mei for editorial assistance.

Author contributions

L.D.M., J.P., N.T., F.P., G.D.C., D.S. and V.E. designed research; D.L., L.R., K.M., D.S., Paul Brennah, I.H., W.A., P.L., C.C., L.R., J.P., C.H., K.K., D.I.C., G.J.M., P.T., A.A., A.Z., S.F., R.H., T.N.T., R.A.M., J.M., E.N., V.E., M.V., L.F., M.P.C., A.M., A.W.D., R.K., V.W.F., A.F.O., J.P.Z., E.M.S., G.L., F.L., Z.F.Z., H.M., E.S., P.L., C.L.V., W.G., C.C., S.M.S., T.Z., T.L.V, K.K., M.M.C., S.B., R.B.H., M.P., M.G., S.S., G.P.Y., Paolo Boffetta. and L.D.M. conducted research and provided single-study databases; S.C.C. and Y.A.L. prepared the pooled dataset for the analysis; M.H. and Paolo Boffetta are the scientific coordinators of the INHANCE consortium and pooled data coordinators; G.D.C. and V.E. performed all statistical analyses; F.P. and N.T. provided advice on statistical issues; C.L.V. provided advice on epidemiological issues and interpretation of results; J.P., L.D.M., G.D.C. and V.E. wrote the paper and had primary responsibility for final content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The informed consent and institutional review board approval were obtained within the framework of the original studies, according to the laws in force at the time of data collection. In addition, a central Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from the University of Utah, #42912.

Data availability

Data are available for scientific purposes upon reasonable request to the corresponding authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Funding information

This work was supported by grants from the: National Institutes of Health (NIH) [no grant number provided for the INHANCE Pooled Data Project, grant numbers P01CA068384, K07CA104231 for the New York Multicenter study, grant numbers R01CA048996, R01DE012609 for the Seattle (1985-1995) study, grant number TW001500 for the Fogarty International Research Collaboration Award (FIRCA) supporting the Iowa study, grant number R01CA061188 for the North Carolina (1994–1997) study, grant numbers P01CA068384, K07CA104231, R01DE013158 for the Tampa study, grant numbers P50CA090388, R01DA011386, R03CA077954, T32CA009142, U01CA096134, R21ES011667 for the Los Angeles study, grant numbers R01CA078609, R01CA100679 for the Boston study, grant number R01CA051845 for the MSKCC study, grant number R01CA030022 for the Seattle-Leo study, grant number DE016631 for the Baltimore study, no grant number provided for the Puerto Rico study]; National Cancer Institute (NCI) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) [grant number R03CA113157 for the INHANCE Pooled Data Project, no grant number provided for the Intramural Program supporting the Puerto Rico study, grant number R01CA90731-01 for the North Carolina (2002–2006) study]; National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) [grant number R03DE016611 for the INHANCE Pooled Data Project, grant numbers R01DE011979, R01DE013110 for the Iowa study, no grant number provided for the Intramural Program supporting the Puerto Rico study]; Italian Association for Research on Cancer (AIRC) [no grant number provided for the Milan (1984–1989) study, for the Aviano study, for the Italy Multicenter study, grant number 10068 for the Milan (2006–2009) study]; Italian League against Cancer [no grant number provided for the Aviano and Italy Multicenter studies]; Italian Ministry of Research [no grant number provided for the Italy Multicenter study]; Ministero della Salute Ricerca Corrente [no grant number provided for the Aviano study]; the Swiss Research against cancer/Oncosuisse [grant numbers KFS-700, OCS-1633 for the Switzerland study, grant number KFS1096-09-2000 for the France (1987–1992) study]; European Commission [grant number IC18-CT97-0222 (INCO-DC Program) for the Latin America study]; Veterans Affairs Merit Review Funds [no grant number provided for the Iowa study]; National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) [grant number P30ES010126 for the North Carolina (1994–1997) study, National Cancer Institute (NCI) [grant number R01-CA90731for the North Carolina (2002–2006) study]; Alper Research Program for Environmental Genomics of the UCLA Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center [no grant number provided for the Los Angeles study]; Fondo para la Investigacion Cientifica y Tecnologica Argentina (FONCYT) [no grant number provided for the Latin America study]; Institut Hospital del Mar d’Investigacions Mediquès (IMIM) [no grant number provided for the Latin America study]; Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa no Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) [grant number 01/01768-2 for the Latin America study, grant numbers GENCAPO 04/12054-9, 10/51168-0 for the Sao Paulo study]; Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias (FIS) of the Spanish Government [grant number FIS 97/0024, FIS 97/0662, BAE 01/5013 for the International Multicenter study]; International Union Against Cancer (UICC) [no grant number provided for the International Multicenter study]; Yamagiwa-Yoshida Memorial International Cancer Study Grant [no grant number provided for the International Multicenter study]; European Community (5th Framework Programme) [grant number QLK1-CT-2001-00182 for the Western Europe study]; Scientific Research grant from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, Culture and Technology of Japan [grant number 17015052 for the Japan (2001–2005) study]; Third-Term Comprehensive 10-Year Strategy for Cancer Control from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan [grant number H20-002 for the Japan (2001–2005) study]; Italian Foundation for Cancer Research (FIRC) [no grant number provided for the Milan (2006–2009) study]; Italian Ministry of Education—PRIN 2009 Program [grant number X8YCBN for the Milan study (2006–2009) study]; Fribourg League against Cancer [grant number FOR381.88 for the France (1987–1992) study]; Swiss Cancer Research [grant number AKT 617 for the France (1987–1992) study]; Gustave-Roussy Institute [grant number 88D28 for the France (1987–1992) study]; French National Research Agency (ANR) [no grant number provided for the France Multicenter (2001–2007) study]; French National Cancer Institute (INCA) [no grant number provided for the France Multicenter (2001–2007) study]; French Agency for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health and Safety (ANSES) [no grant number provided for the France Multicenter (2001–2007) study]; French Institute for Public Health Surveillance (InVS) [no grant number provided for the France Multicenter (2001–2007) study]; Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (FRM) [no grant number provided for the France Multicenter (2001–2007) study]; Fondation de France [no grant number provided for the France Multicenter (2001–2007) study]; Fondation ARC pour la Recherche sur le Cancer [no grant number provided for the France Multicenter (2001–2007) study]; French Ministry of Labour (Direction Générale du Travail) [no grant number provided for the France Multicenter (2001–2007) study]; French Ministry of Health (Direction Générale de la Santé) [no grant number provided for the France Multicenter (2001–2007) study]; V.E. was supported by Università degli Studi di Milano ‘Young Investigator Grant Program 2017’.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jerry Polesel, Email: polesel@cro.it.

Luigino Dal Maso, Email: epidemiology@cro.it.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41416-020-01031-z.

References

- 1.World Cancer Research Fund International/American Institute for Cancer Research. Diet, nutrition, physical activity, and cancer: A global perspective. Continuous Update Project Expert Report 2018. https://www.wcrf.org/dietandcancer. (2020).

- 2.International Agency for Research on Cancer. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans Vol. 100E. Personal habits and indoor combustions (IARC Sci Publ, Lyon, 2012). [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Praud D, Rota M, Rehm J, Shield K, Zatoński W, Hashibe M, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality attributable to alcohol consumption. Int. J. Cancer. 2016;138:1380–1387. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Maso M, Bravi F, Polesel J, Negri E, Decarli A, Serraino D, et al. Attributable fractions for multiple risk factors: Methods, interpretation and examples. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2020;29:854–865. doi: 10.1177/0962280219848471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.International Agency for Research on Cancer. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans Vol. 96. Alcohol consumption and ethyl carbamate (IARC Sci Publ, Lyon, 2010). [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Bagnardi V, Rota M, Botteri E, Tramacere I, Islami F, Fedirko V, et al. Alcohol consumption and site-specific cancer risk: a comprehensive dose-response meta-analysis. Br. J. Cancer. 2015;112:580–593. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lubin JH, Purdue K, Kelsey K, Zhang ZF, Winn D, Wei Q, et al. Total exposure and exposure rate effects for alcohol and smoking and risk of head and neck cancer: a pooled analysis of case-control studies. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2009;170:937–947. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Di Credico G, Edefonti V, Polesel J, Pauli F, Torelli N, Serraino D, et al. Joint effects of intensity and duration of cigarette smoking on the risk of head and neck cancer: a bivariate spline model approach. Oral. Oncol. 2019;94:47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2019.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doll R. An epidemiological perspective of the biology of cancer. Cancer Res. 1978;38:3573–3583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lubin JH, Alavanja MC, Caporaso N, Brown LM, Brownson RC, Field RW, et al. Cigarettes smoking and cancer risk: modelling total exposure and intensity. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2007;166:479–489. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Osch FHM, Vlaanderen J, Jochems SHJ, Bosetti C, Polesel J, Porru S, et al. Modelling the complex exposure history of smoking in predicting bladder cancer. A pooled analysis of 15 case-control studies. Epidemiology. 2019;30:458–465. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conway DI, Hashibe M, Boffetta P, INHANCE consortium. Wunsch-Filho V, Muscat J, et al. Enhancing epidemiologic research on head and neck cancer: INHANCE—The international head and neck cancer epidemiology consortium. Oral. Oncol. 2009;45:743–746. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Winn DM, Lee YC, Hashibe M, Boffetta P. INHANCE consortium. The INHANCE consortium: toward a better understanding of the causes and mechanisms of head and neck cancer. Oral. Dis. 2015;21:685–693. doi: 10.1111/odi.12342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hashibe M, Brennan P, Benhamou S, Castellsague X, Chen C, Curado MP, et al. Alcohol drinking in never users of tobacco, cigarette smoking in never drinkers, and the risk of head and neck cancer: pooled analysis in the International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology Consortium. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2007;99:777–789. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franceschi S, Talamini R, Barra S, Barón AE, Negri E, Bidoli E, et al. Smoking and drinking in relation to cancers of the oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, and esophagus in northern Italy. Cancer Res-. 1990;50:6502–6507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zheng TZ, Boyle P, Hu HF, Duan J, Jian PJ, Ma DQ, et al. Dentition, oral hygiene, and risk of oral cancer: a case-control study in Beijing, People’s Republic of China. Cancer Causes Control. 1990;1:235–241. doi: 10.1007/BF00117475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Negri E, La Vecchia C, Franceschi S, Tavani A. Attributable risk for oral cancer in northern Italy. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 1993;2:189–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rogers MA, Thomas DB, Davis S, Vaughan TL, Nevissi AE. A case-control study of element levels and cancer of the upper aerodigestive tract. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 1993;2:305–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muscat JE, Richie JP, Jr., Thompson S, Wynder EL. Gender differences in smoking and risk for oral cancer. Cancer Res. 1996;56:5192–5197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schantz SP, Zhang ZF, Spitz MS, Sun M, Hsu TC. Genetic susceptibility to head and neck cancer: interaction between nutrition and mutagen sensitivity. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:765–781. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199706000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levi F, Pasche C, La Vecchia C, Lucchini F, Franceschi S, Monnier P. Food groups and risk of oral and pharyngeal cancer. Int. J. Cancer. 1998;77:705–709. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980831)77:5<705::aid-ijc8>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith EM, Hoffman HT, Summersgill KS, Kirchner HL, Turek LP, Haugen TH. Human papillomavirus and risk of oral cancer. Laryngoscope. 1998;108:1098–1103. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199807000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayes RB, Bravo-Otero E, Kleinman DV, Brown LM, Fraumeni JF, Jr, Harty LC, et al. Tobacco and alcohol use and oral cancer in Puerto Rico. Cancer Causes Control. 1999;10:27–33. doi: 10.1023/a:1008876115797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olshan AF, Weissler MC, Watson MA, Bell DA. GSTM1, GSTT1, GSTP1, CYP1A1, and NAT1 polymorphisms, tobacco use, and the risk of head and neck cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2000;9:185–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elahi A, Zheng Z, Park J, Eyring K, McCaffrey T, Lazarus P. The human OGG1 DNA repair enzyme and its association with orolaryngeal cancer risk. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:1229–1234. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.7.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herrero R, Castellsagué X, Pawlita M, Lissowska J, Kee F, Balaram T, et al. IARC Multicenter Oral Cancer Study Group. Human papillomavirus and the risk of Human papillomavirus and oral cancer: the International Agency for Research on Cancer multicenter study. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1772–1783. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bosetti C, Gallus S, Trichopoulou A, Talamini R, Franceschi S, Negri E, et al. Influence of the Mediterranean diet on the risk of cancers of the upper aerodigestive tract. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2003;12:1091–1094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benhamou S, Tuimala J, Bouchardy C, Dayer P, Sarasin A, Hirvonen A. DNA repair gene XRCC2 and XRCC3 polymorphisms and susceptibility to cancers of the upper aerodigestive tract. Int. J. Cancer. 2004;112:901–904. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenblatt KA, Daling JR, Chen C, Sherman KJ, Schwartz SM. Marijuana use and risk of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4049–4054. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Z, Shi Q, Liu Z, Sturgis EM, Spitz MR, Wei Q. Polymorphisms of methionine synthase and methionine synthase reductase and risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: a case-control analysis. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2005;14:1188–1193. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peters ES, McClean MD, Liu M, Eisen EA, Mueller N, Kelsey KT. The ADH1C polymorphism modifies the risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck associated with alcohol and tobacco use. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2005;14:476–482. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cui Y, Morgenstern H, Greenland S, Tashkin DP, Mao JT, Cai L, et al. Polymorphism of xeroderma pigmentosum group G and the risk of lung cancer and squamous cell carcinomas of the oropharynx, larynx and esophagus. Int. J. Cancer. 2006;118:714–720. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suzuki T, Wakai K, Matsuo K, Hirose K, Ito H, Kuriki K, et al. Effect of dietary antioxidants and risk of oral, pharyngeal and laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma according to smoking and drinking habits. Cancer Sci. 2006;97:760–767. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00232.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.D’Souza G, Kreimer AR, Viscidi R, Pawlita M, Fakhry C, Koch WM, et al. Case-control study of human papilloma virus and oropharyngeal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;356:1944–1956. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lagiou P, Georgila C, Minaki P, Ahrens W, Pohlabelm H, Benhamou S, et al. Alcohol-related cancers and genetic susceptibility in Europe: the ARCAGE project: study samples and data collection. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2009;18:76–84. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e32830c8dca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Divaris K, Olshan AF, Smith J, Bell ME, Weissler MC, Funkhouser WK, et al. Oral health and risk for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: the Carolina Head and Neck Cancer Study. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21:567–575. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9486-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boing AF, Antunes JL, de Carvalho MB, de Góis Filho JL, Kowalski LP, Michaluart P, Jr, et al. How much do smoking and alcohol consumption explain socioeconomic inequalities in head and neck cancer risk? J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2011;65:709–714. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.097691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Szymańska K, Hung RJ, Wünsch-Filho V, Eluf-Neto J, Curado MP, Koifman S, et al. Alcohol and tobacco, and the risk of cancers of the upper aerodigestive tract in Latin America: a case-control study. Cancer Causes Control. 2011;22:1037–1046. doi: 10.1007/s10552-011-9779-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luce D, Stücker I. ICARE Study Group. Investigation of occupational and environmental causes of respiratory cancers (ICARE): a multicenter, population-based case-control study in France. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:928. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bravi F, Bosetti C, Filomeno M, Levi F, Garavello W, Galimberti S, et al. Foods, nutrients and the risk of oral and pharyngeal cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 2013;109:2904–2910. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sarich P, Canfell K, Banks E, Paige E, Egger S, Joshy G, Korda R, Weber M. A prospective study of health conditions related to alcohol consumption cessation among 97,852 drinkers aged 45 and over in Australia. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2019;43:710–721. doi: 10.1111/acer.13981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ruppert, D., Wand, M. & Carroll, R. Semiparametric Regression(Cambridge Series in Statistical and Probabilistic Mathematics) (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2003).

- 43.Di Credico, G. Some developments in semiparametric and cross-classified multilevel models. PhD Thesis, University of Padua, 2018. (2020).

- 44.O’Hara RB, Sillanpää MJ. A review of Bayesian variable selection methods: what, how and which. Bayesian Anal. 2009;4:85–117. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gelman A., Stern H. S., Carlin J. B. et al. Bayesian Data Analysis (Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2013).

- 46.Gelman A, Hwang J, Vehtari A. Understanding predictive information criteria for Bayesian models. Stat. Comput. 2014;24:997–1016. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stan Development Team. Stan Modeling Language Users Guide and Reference Manual. Version 2.17.0 (2017).

- 48.R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, 2019).

- 49.Polesel J, Talamini R, La Vecchia C, Levi F, Barzan L, Serraino D, et al. Tobacco smoking and the risk of upper aero-digestive tract cancers: a re-analysis of case-control studies using spline models. Int. J. Cancer. 2008;122:2398–2402. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seitz HK, Stickel F, Homann N. Pathogenetic mechanisms of upper aerodigestive tract cancer in alcoholics. Int. J. Cancer. 2004;108:483–487. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lubin JH, Cook MB, Pandeva N, Vaughan TL, Abnet CC, Giffen C, et al. The importance of exposure rate on odds ratios by cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption for adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma in the Barrett’s Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma Consortium. Cancer Epidemiol. 2012;36:306–316. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Franceschi S, Levi F, Dal Maso L, Talamini R, Conti E, Negri E, La Vecchia C. Cessation of alcohol drinking and risk of cancer of the oral cavity and pharynx. Int. J. Cancer. 2000;85(6):787–790. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(20000315)85:6<787::aid-ijc8>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Del Boca FK, Darkes J. The validity of self-reports of alcohol consumption: state of the science and challenges for research. Addiction. 2003;98(Suppl 2):1–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1359-6357.2003.00586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bergmann MM, Rehm J, Klipstein-Grobusch K, Boeing H, Schütze M, Drogan D, et al. The association of pattern of lifetime alcohol use and cause of death in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2013;42:1772–1790. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Poikolanen K. Underestimation of recalled alcohol intake in relation to actual consumption. Br. J. Addict. 1985;80:215–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1985.tb03276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ferraroni M, Decarli A, Franceschi S, La Vecchia C, Enard L, Negri E, et al. Validity and reproducibility of alcohol consumption in Italy. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1996;25:775–782. doi: 10.1093/ije/25.4.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gillison ML, Lowy DR. A causal role for human papillomavirus in head and neck cancer. Lancet. 2004;363:1488–1489. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16194-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brennan P, Lewis S, Hashibe M, Bell DA, Boffetta P, Bouchardy C, et al. Pooled analysis of alcohol dehydrogenase genotypes and head and neck cancer: a HuGE Review. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2004;159:1–6. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wood AM, Kaptoge S, Butterworth AS, Willeit P, Warnakula S, Bolton T, et al. Risk thresholds for alcohol consumption: combined analysis of individual-participant data for 599 912 current drinkers in 83 prospective studies. Lancet. 2018;391:1513–1523. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30134-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.WHO. Global status report on alcohol and health 2018 (World Health Organization, Geneva, 2018).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available for scientific purposes upon reasonable request to the corresponding authors.