The activation of innate immunity is essential for host cells to restrict the spread of invading viruses and other pathogens. IRF3 plays a critical role in the innate immune response to RNA viral infection. However, whether IRF1 plays a role in innate immunity is unclear. In this study, we demonstrated that IRF1 promotes the innate immune response to viral infection. IRF1 is induced by viral infection. Notably, IRF1 targets and augments the phosphorylation of IRF3 by blocking the interaction between IRF3 and PP2A, leading to the upregulation of innate immunity. Collectively, the results of our study provide new insight into the regulatory mechanism of IFN signaling and uncover the role of IRF1 in the positive regulation of the innate immune response to viral infection.

KEYWORDS: innate immunity, IRF1, IRF3, PP2A, interferon, virus

ABSTRACT

Innate immunity is an essential way for host cells to resist viral infection through the production of interferons (IFNs) and proinflammatory cytokines. Interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) plays a critical role in the innate immune response to viral infection. However, the role of IRF1 in innate immunity remains largely unknown. In this study, we found that IRF1 is upregulated through the IFN/JAK/STAT signaling pathway upon viral infection. The silencing of IRF1 attenuates the innate immune response to viral infection. IRF1 interacts with IRF3 and augments the activation of IRF3 by blocking the interaction between IRF3 and protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A). The DNA binding domain (DBD) of IRF1 is the key functional domain for its interaction with IRF3. Overall, our study reveals a novel mechanism by which IRF1 promotes the innate immune response to viral infection by enhancing the activation of IRF3, thereby inhibiting viral infection.

IMPORTANCE The activation of innate immunity is essential for host cells to restrict the spread of invading viruses and other pathogens. IRF3 plays a critical role in the innate immune response to RNA viral infection. However, whether IRF1 plays a role in innate immunity is unclear. In this study, we demonstrated that IRF1 promotes the innate immune response to viral infection. IRF1 is induced by viral infection. Notably, IRF1 targets and augments the phosphorylation of IRF3 by blocking the interaction between IRF3 and PP2A, leading to the upregulation of innate immunity. Collectively, the results of our study provide new insight into the regulatory mechanism of IFN signaling and uncover the role of IRF1 in the positive regulation of the innate immune response to viral infection.

INTRODUCTION

Innate immunity is the first line of defense against pathogen invasion. Host cells recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) by pathogen recognition receptors (PRRs) such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs), RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs), NOD-like receptors (NLRs), and intracellular DNA sensors. Viral double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) in the endosome or bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is recognized by TLR3 or TLR4, while cytoplasmic viral dsRNA is sensed by RIG-I, MDA5, or protein kinase R (PKR) (1–3). With the recognition of PAMPs, the N-terminal tandem caspase activation recruitment domain of RIG-I and MDA5 interacts with MAVS and subsequently activates TANK binding kinase 1 (TBK1) and IκB kinase ε (IKKε). The kinases TBK1 and IKKε phosphorylate interferon (IFN) regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) at Ser386 and Ser396 (4–7). In turn, IRF3 dimerizes and transfers into the nucleus to induce IFNs (8). IFNs can be recognized by the IFN receptor to induce the expression of IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs), which play an essential role in antiviral activity through the JAK/STAT signaling pathway (9).

IRF3 phosphorylation is a crucial step in the induction of IFNs (10–12). Previous studies have suggested many ways in which posttranslational regulation impacts the IFN signaling pathway by regulating IRF3. TRIM26, FoxO1, or RBCK1 interacts with IRF3 and promotes K48-linked polyubiquitination and degradation of IRF3 to inhibit innate immunity (13–15). PRMT6 inhibits the TBK1-IRF3 interaction and subsequently impairs the activation of IRF3 and IFN production (16). Protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) is an important phosphatase for IRF3. Host factors may regulate the phosphorylation of IRF3 by influencing the interaction between IRF3 and PP2A. RACK1 and FBXO17 recruit PP2A to restrict type I IFN signaling by inhibiting the phosphorylation of IRF3 (17, 18). Long noncoding RNA leucine-rich repeat-containing 55 (lncLrrc55-AS) promotes IRF3 phosphorylation by inhibiting the interaction between IRF3 and PP2A (17–19). How host proteins regulate IRF3 activity is still obscure.

IRF1 is the first identified IRF (20), which is involved in various physiological and pathological aspects, including viral infection, tumor immune surveillance, proinflammatory injury, the development of the immune system, and autoimmune diseases (21). IRF1 deficiency significantly increases the incidence of developing tumors in combination with other genetic alterations (22). However, whether IRF1 can induce the production of IFN in response to viral infection remains controversial. IRF1 binds to the IFN-β promoter (23), while a recent study showed that IRF1 knockout (KO) mice fail to impair IFN-β production (24). IRF1 controls the induction of type III IFN by many pathogens (25, 26). IRF1 and IRF3 are activated independently of each other (27). One recent study showed that IRF1 binds to the promoter region of STAT1 to induce the transcription of ISGs, thus inhibiting hepatitis E virus (HEV) replication (28).

In this study, we found that the induction of IRF1 by viral infection depends on IFN/JAK/STAT signaling. IRF1 promotes the production of IFNs and ISGs triggered by RNA and DNA viruses. However, IRF1 fails to enhance the activation of STAT1 phosphorylation and the induction of ISGs by IFN-α. IRF1 interacts with IRF3 to augment the phosphorylation and dimerization of IRF3. IRF1 blocks the interaction between IRF3 and PP2A, thereby enhancing IRF3 activation and IFN production. The DNA binding domain (DBD) of IRF1 plays a key role in enhancing IRF3 activation and IFN production. Thus, IRF1 may serve as a possible target for the treatment of emerging virus-associated disorders.

RESULTS

Induction of IRF1 by viral infection relies on the IFN/JAK/STAT signaling pathway.

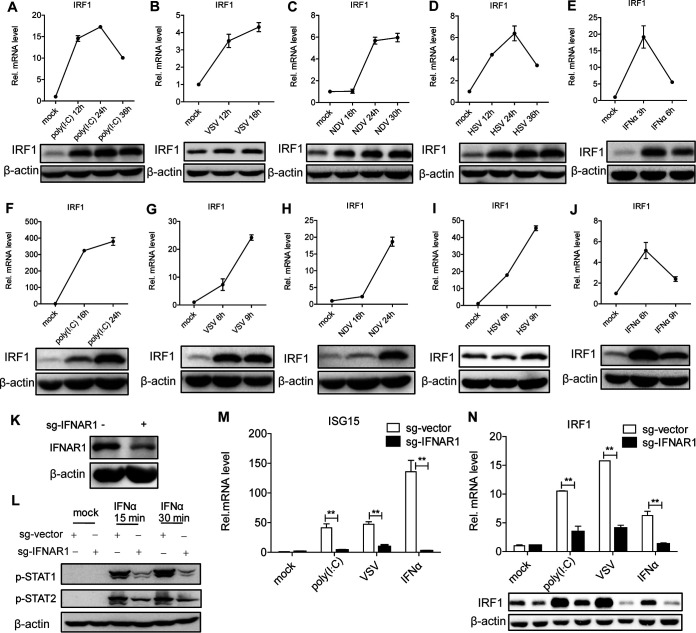

To identify the association between IRF1 and viral infection, we examined IRF1 mRNA and protein in human hepatocytes stimulated with the nucleic acid mimic poly(I·C). The levels of IRF1 mRNA and protein were upregulated in Huh7 cells with poly(I·C) treatment (Fig. 1A). To test IRF1 levels in the context of viral infection, we infected Huh7 cells with an RNA virus (vesicular stomatitis virus [VSV] or Newcastle disease virus [NDV]) or a DNA virus (herpes simplex virus [HSV]). Either RNA or DNA virus induced IRF1 mRNA and protein in Huh7 cells (Fig. 1B to D). To rule out the possibility of cell specificity, we performed the above-described experiments in HLCZ01 cells supporting the entire life cycle of hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) (29). IRF1 was also induced by poly(I·C) or viral infection in HLCZ01 cells (Fig. 1F to I). These data suggested that a DNA or RNA virus can induce the expression of IRF1, indicating a potential role of IRF1 in the innate immune response to viral infection.

FIG 1.

IRF1 can be induced by viral infection in a JAK/STAT signaling-dependent way. (A to J) Huh7 (A to E) or HLCZ01 (F to J) cells were transfected with poly(I·C) (200 ng); infected with NDV (multiplicity of infection [MOI] = 0.05), VSV (MOI = 0.5), or HSV (MOI = 1); or treated with IFN-α (200 U/ml) for the indicated times. IRF1 mRNA (top) and protein (bottom) were detected by real-time PCR and Western blotting, respectively. (K) IFNAR1 was knocked down in HLCZ01 cells. IFNAR1 protein was detected by Western blotting. sg-IFNAR1, single guide RNA specifically targeted on IFNAR1. (L) Immunoblot analysis of the indicated proteins in IFNAR1 knockdown HLCZ01 or control cells treated with IFN-α (200 U/ml) for 15 or 30 min. (M and N) IFNAR1-silenced HLCZ01 or control cells were treated with poly(I·C) (200 ng) for 16 h, VSV (MOI = 0.5) for 6 h, or IFN-α (200 U/ml) for 16 h. ISG15 mRNA (M) and IRF1 protein (N) were detected by real-time PCR and Western blotting, respectively. Experiments were independently repeated two or three times, with similar results. Data are presented as means ± SD with from biological replicates. **, P < 0.01 versus the control (by Student’s two-sided t test).

Viral infection induces the expression of IFNs. IFNs recognize their receptors to activate the JAK/STAT signaling pathway and induce ISGs, thereby limiting viral infection. To examine whether the induction of IRF1 by virus depends on the JAK/STAT signaling pathway, we measured the levels of IRF1 mRNA in Huh7 and HLCZ01 cells stimulated with IFN-α. IRF1 can be induced by IFN-α in Huh7 or HLCZ01 cells (Fig. 1E and J), indicating that the induction of IRF1 by viral infection may rely on the JAK/STAT pathway. To further confirm our speculation, we silenced IFNAR1 in HLCZ01 cells. IFNAR1 was knocked down effectively (Fig. 1K). To ensure the functional efficiency of IFNAR1 knockdown, we detected the phosphorylation of STAT1 and STAT2 with IFN-α treatment. The phosphorylation of STAT1 and STAT2 was impaired in IFNAR1-silenced cells compared to control cells following IFN-α treatment (Fig. 1L). The silencing of IFNAR1 decreased the induction of ISG15 by IFN-α, poly(I·C), or viral infection (Fig. 1M). Importantly, IFNAR1 knockdown significantly decreased the levels of IRF1 mRNA and protein in HLCZ01 cells under IFN-α treatment or viral infection (Fig. 1N). All the data demonstrated that the induction of IRF1 by viral infection depends on the IFN/JAK/STAT signaling pathway.

IRF1 promotes the innate immune response to viral infection and exhibits antiviral activity.

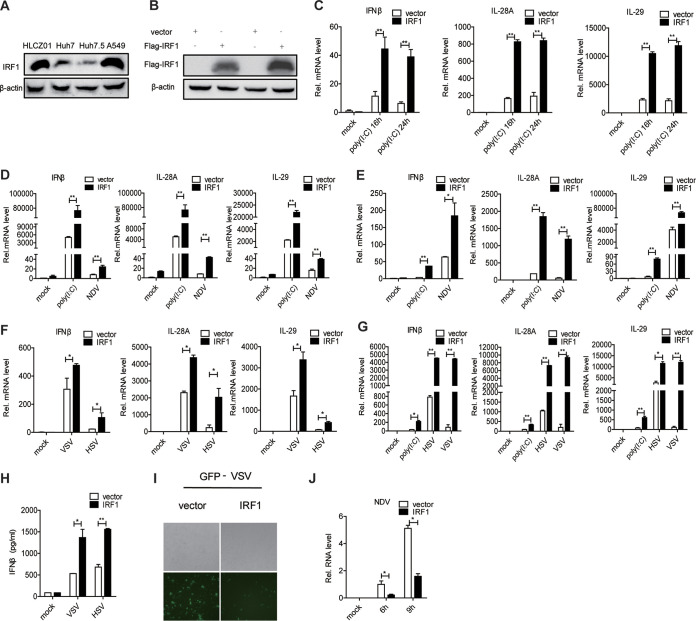

IRF1 was induced by viral infection, and its production required the IFN/JAK/STAT signaling pathway. We thought that IRF1 may play an important role in the innate immune response to viral infection. To assess this hypothesis, we measured the levels of IFNs via the ectopic expression of IRF1 in human hepatocytes. Upon stimulation with poly(I·C), the overexpression of IRF1 markedly augmented the expression of type I IFN (IFN-β) and type III IFN (interleukin-28A [IL-28A] and IL-29) in Huh7.5 cells (Fig. 2A to C). The delivery of IRF1 into HLCZ01 cells significantly enhanced the expression of IFN-β, IL-28A, and IL-29 upon stimulation with poly(I·C) or infection with NDV (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, we performed the above-described experiments in Huh7 (Fig. 2E and F) and A549 (Fig. 2G) cells and observed similar results in these cells upon poly(I·C) treatment or DNA or RNA virus infection. The IFN-β protein level in the supernatant was enhanced by IRF1 in A549 cells upon VSV or HSV infection (Fig. 2H). Consistent with these results, the ectopic expression of IRF1 decreased the abundance of VSV or NDV in Huh7 cells (Fig. 2I and J).

FIG 2.

Ectopic expression of IRF1 promotes the innate immune response to viral infection and exhibits antiviral activity. (A) IRF1 was detected by Western blotting in HLCZ01, Huh7, Huh7.5, and A549 cells. (B) Huh7.5 cells were transfected with pFlag-IRF1 or the control vector, and Flag-IRF1 protein was detected by Western blotting. (C) Huh7.5 cells were transfected with pFlag-IRF1 or the control vector and then transfected with poly(I·C) (200 ng) for the indicated times. The levels of IFN-β, IL-28A, and IL-29 mRNAs were examined by real-time PCR and normalized to the level of GAPDH. (D) HLCZ01 cells were transfected with p3×Flag-CMV-vector or p3×Flag-CMV-IRF1 for 36 h and then treated with poly(I·C) (200 ng) or infected with NDV (MOI = 0.1) for 16 h. The levels of IFN-β, IL-28A, and IL-29 mRNAs were examined by real-time PCR and normalized to the level of GAPDH. (E and F) Huh7 cells were transfected with p3×Flag-CMV-vector or p3×Flag-CMV-IRF1 for 36 h and then treated with poly(I·C) (200 ng) or infected with NDV (MOI = 0.05), HSV (MOI = 1), or VSV (MOI = 0.5). The levels of IFN-β, IL-28A, and IL-29 mRNAs were examined by real-time PCR and normalized to the level of GAPDH. (G) A549 cells were transfected with p3×Flag-CMV-vector or p3×Flag-CMV-IRF1 for 36 h and then treated with poly(I·C) (200 ng) or infected with HSV (MOI = 1) or VSV (MOI = 0.5). The levels of IFN-β, IL-28A, and IL-29 mRNAs were examined by real-time PCR and normalized to the level of GAPDH. (H) A549 cells were transfected with p3×Flag-CMV-vector or p3×Flag-CMV-IRF1 for 36 h and then infected with HSV (MOI = 1) or VSV (MOI = 0.5). IFN-β protein in the supernatant was examined by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). (I) Microscopy imaging of IRF1-overexpressing Huh7 cells infected with VSV carrying green fluorescent protein (VSV-GFP) (MOI = 0.01) for 16 h. (J) NDV RNA was detected by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) in IRF1-overexpressing Huh7 cells infected with NDV (MOI = 0.05) for 6 or 9 h. Experiments were independently repeated two or three times, with similar results. Data are presented as means ± SD from three biological replicates. *, P < 0.05 versus the control; **, P < 0.01 versus the control (by Student’s two-sided t test).

To further verify the role of IRF1 in innate immunity, we constructed stable IRF1-silenced cells using Huh7 cells. IRF1 was knocked down effectively in Huh7 cells (Fig. 3A). IRF1 knockdown inhibited the induction of IFN-β, IL-28A, and IL-29 by poly(I·C) or NDV (Fig. 3B). When we silenced IRF1 in Huh7 cells using small interfering RNA (siRNA) (Fig. 3C), the induction of IFN-β, IL-28A, and IL-29 by poly(I·C), NDV, VSV, or HSV was attenuated (Fig. 3D and E). To rule out the possibility of cell specificity, we performed the above-described experiments in A549 cells and observed similar results (Fig. 3F). The activation of IFN signaling by IRF1 prompted us to further explore the role of IRF1 in the cellular antiviral response. The replication of VSV and NDV was enhanced in IRF1-silenced Huh7 cells (Fig. 3G and H). All the data demonstrated that IRF1 promotes the innate immune response to viral infection and exhibits antiviral activity.

FIG 3.

Silencing of IRF1 inhibits antiviral immunity. (A and B) Huh7 cells were transfected with pshIRF1. (A) IRF1 protein was tested by Western blotting. The cells were transfected with 200 ng poly(I·C) or infected with NDV for 16 h. (B) The levels of IFN-β, IL-28A, and IL-29 mRNAs were examined by real-time PCR and normalized to the level of GAPDH. (C) Huh7 cells were transfected with IRF1 siRNA, and IRF1 protein was tested by Western blotting. (D and E) Huh7 cells were transfected with negative-control (nc) or IRF1 siRNA and then treated with poly(I·C) (200 ng) or infected with NDV (MOI = 0.05), VSV (MOI = 0.5), or HSV (MOI = 1). The levels of IFN-β, IL-28A, and IL-29 mRNAs were examined by real-time PCR and normalized to the level of GAPDH. (F) A549 cells were transfected with negative-control or IRF1 siRNA and then treated with poly(I·C) (200 ng) or infected with VSV (MOI = 0.5) or HSV (MOI = 1). The levels of IFN-β, IL-28A, and IL-29 mRNAs were examined by real-time PCR and normalized to the level of GAPDH. (G) Microscopy imaging of IRF1-silenced Huh7 cells infected with VSV-GFP (MOI = 0.01) for 16 h. (H) NDV RNA was detected by qRT-PCR in IRF1-silenced Huh7 cells infected with NDV (MOI = 0.1) for 6 or 9 h. Experiments were independently repeated two or three times, with similar results. Data are presented as means ± SD from three biological replicates. *, P < 0.05 versus the control; **, P < 0.01 versus the control; ***, P < 0.001 versus the control (by Student’s two-sided t test).

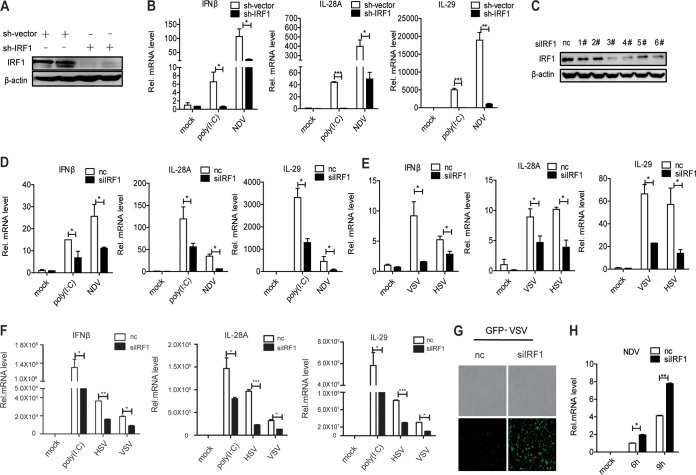

IRF1 enhances the expression of ISGs induced by poly(I·C) and viral infection but not IFN-α.

Viral infection induces the production of IFNs. IFN recognizes its receptors to activate the JAK/STAT pathway, thereby inducing ISGs to participate in the host antiviral response. Considering the role of IRF1 in the induction of IFNs by viral infection, we next investigated whether IRF1 would affect the activation of the JAK/STAT signaling pathway triggered by IFN-α. The forced expression of IRF1 augmented the induction of ISG15 and MX1 by poly(I·C) but not IFN-α in Huh7.5 (Fig. 4A) and HLCZ01 (Fig. 4B) cells. The silencing of IRF1 decreased the production of ISG15 and MX1 stimulated by poly(I·C) and NDV but not IFN-α in Huh7 cells (Fig. 4C). Similar results were also observed in A549 cells (Fig. 4D). The overexpression or silencing of IRF1 in Huh7 cells had no effect on the induction of ISGs by IFN-α at 3 or 6 h (Fig. 4E and F). Moreover, IRF1 lost its positive role in the production of ISGs triggered by poly(I·C) in an IFNAR1 knockdown cell line (Fig. 4G).

FIG 4.

IRF1 enhances the expression of ISGs induced by poly(I·C) and viral infection but not IFN-α. (A and B) Huh7.5 cells (A) or HLCZ01 cells (B) were transfected with p3×Flag-CMV-IRF1 or the control vector and then treated with poly(I·C) (200 ng) or IFN-α (200 U/ml) for 16 h. The levels of MX1 and ISG15 mRNAs were examined by real-time PCR and normalized to the level of GAPDH. (C) Huh7 cells were transfected with IRF1 siRNA or control siRNA for 36 h and then treated with poly(I·C) or IFN-α (200 U/ml) or infected with NDV (MOI = 0.05). The levels of MX1 and ISG15 mRNAs were examined by real-time PCR and normalized to the level of GAPDH. (D) A549 cells were transfected with IRF1 siRNA or control siRNA for 36 h and then treated with IFN-α (200 U/ml) or infected with VSV (MOI = 0.1) or HSV (MOI = 0.2). The levels of MX1 and ISG15 mRNAs were examined by real-time PCR and normalized to the level of GAPDH. (E and F) IRF1 was overexpressed (E) or knocked down (F) in Huh7 cells for 36 h, and the cells were then treated with IFN-α (200 U/ml) for 3 or 6 h. The levels of MX1 and ISG15 mRNAs were examined by real-time PCR and normalized to the level of GAPDH. (G) IFNAR1-silenced HLCZ01 or control cells were transfected with p3×Flag-CMV-IRF1 or the control vector for 36 h and then treated with poly(I·C) (200 ng) for 16 h. The levels of MX1and ISG15 mRNAs were examined by real-time PCR and normalized to the level of GAPDH. (H) Stable IRF1-silenced Huh7 cells or control cells were treated with IFN-α (200 U/ml) for 15 or 30 min, respectively. The indicated proteins were detected by Western blotting. Experiments were independently repeated two or three times, with similar results. Data are presented as means ± SD from three biological replicates. *, P < 0.05 versus the control; **, P < 0.01 versus the control; ns, not significant (by Student’s two-sided t test).

Finally, to investigate the impact of IRF1 on the JAK/STAT signaling pathway, we constructed stable IRF1-silenced Huh7 cells. We found that IRF1 has no effect on the activation of STAT1 and STAT2 by IFN-α (Fig. 4H). Taken together, the results show that IRF1 promotes the induction of IFNs by viral infection and that IRF1 is not involved in the activation of JAK/STAT signaling by IFN-α.

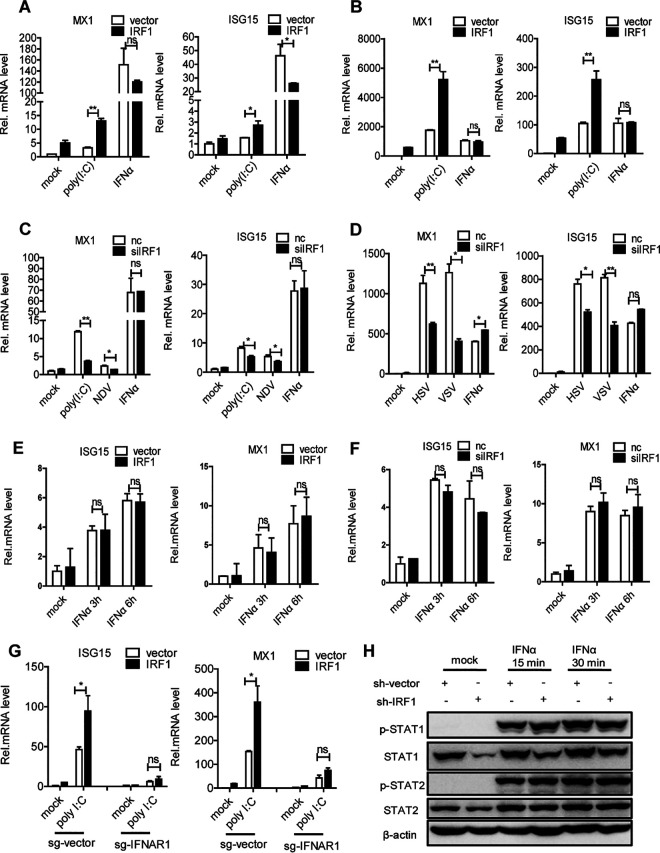

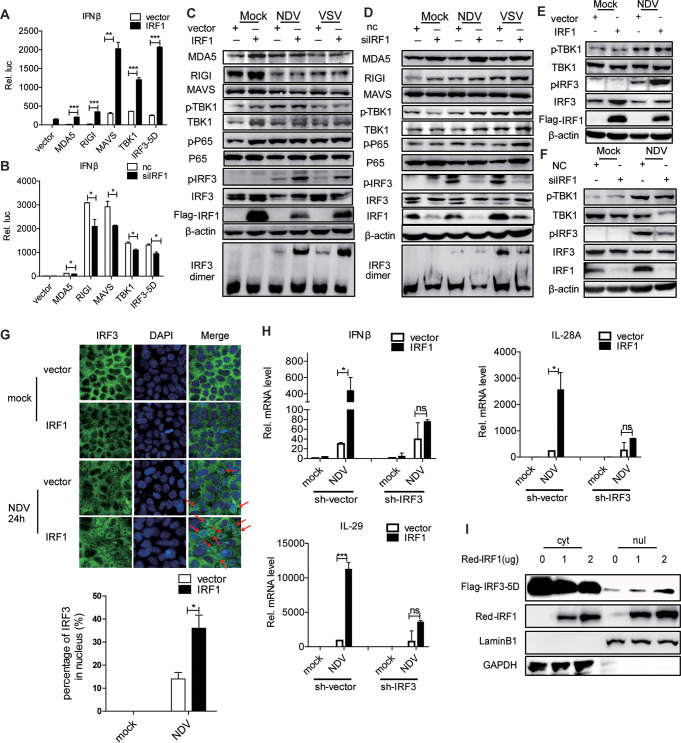

IRF1 promotes the activation of IRF3 by viral infection.

Upon viral infection, RIG-I or MDA5 recruits MAVS and activates TBK1, promoting IRF3 activation. The induction of IFNs by viral infection relies on the activation of IRF3. The phosphorylation of TBK1 promotes the activation of IRF3 phosphorylation. Phosphorylated IRF3 undergoes homodimerization and translocates to the nucleus, inducing ISGs. To investigate which component of the IFN signaling pathway could be targeted by IRF1, we cotransfected plasmids encoding IRF1 and various candidates with an IFN-β–luciferase (Luc) reporter assay system in HEK293T (Fig. 5A) and Huh7 (Fig. 5B) cells. Interestingly, the ectopic expression of IRF1 or the silencing of IRF1 enhanced or decreased, respectively, the activation of the IFN-β promoter by RIG-I, MDA5, MAVS, TBK1, or IRF3-5D (S385D, S386D, S396D, S398D, S402D, S404D, and S405D) (Fig. 5A and B). These data indicated that IRF1 may target elements downstream of IRF3 to promote the IFN signaling pathway. Interestingly, the ectopic expression or knockdown of IRF1 enhanced or attenuated the activation IRF3 (phosphorylation and dimerization) by viral infection in Huh7 (Fig. 5C and D) or HLCZ01 (Fig. 5E and F) cells, while it had no effect on the protein levels of MDA5, RIG-I, and MAVS and the activation of TBK1 and p65. The immunofluorescence data further supported that IRF1 augments the activation of IRF3 by viral infection (Fig. 5G). Importantly, the silencing of IRF3 abolished the induction of IFNs by viral infection in IRF1-overexpressing cells (Fig. 5H). Active IRF3-5D is widely used for IFN induction. Our data showed that IRF1 promoted the expression of IFN-β luciferase activity induced by IRF3-5D and the phosphorylation of IRF3. To determine the concealed mechanism, we cotransfected IRF3-5D–Flag and IRF1-red fluorescent protein (RFP) and found that IRF1 overexpression increased the nucleic translocation of IRF3-5D and decreased IRF3-5D in the cytoplasm (Fig. 5I). Based on the observations of the regulatory function of IRF1 described above, we speculated that IRF1 may function by interacting with IRF3.

FIG 5.

IRF1 promotes the activation of IRF3 by viral infection. (A and B) Luciferase activity of lysates of HEK293T (A) and Huh7 (B) cells transfected for 24 h with IFN-β–Luc plus Flag–RIG-I, Flag-MDA5, Flag-MAVS, Flag-TBK1, or Flag–IRF3-5D along with p3×Flag-CMV-IRF1 and an empty vector (A) or IRF1 siRNA or control siRNA (B). The results are presented relative to the luciferase activity in control cells. (C and D) Huh7 cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids (C) or IRF1 siRNA (D) for 36 h and then infected with NDV (MOI = 0.05) for 24 h or VSV (MOI = 0.5) for 6 h. Immunoblot assays were performed with the indicated antibodies. (E and F) HLCZ01 cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids (E) or IRF1 siRNA (F) for 36 h and then infected with NDV (MOI = 0.1) for 24 h. Immunoblot assays were performed with the indicated antibodies. (G) Huh7 cells were transfected with p3×Flag-CMV-IRF1 or an empty vector for 24 h and then infected with NDV (MOI = 0.05) for 24 h. (Top) The subcellular localization of endogenous IRF3 was analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. The arrows highlight the nuclear localization of IRF3 by immunofluorescence staining. (Bottom) Quantitative analysis of IRF3 localization in the nucleus. (H) Huh7 cells were infected with lentivirus for silencing IRF3 for 24 h and then transfected with p3×Flag-CMV-IRF1 or an empty vector. The cells were infected with NDV (MOI = 0.05) for 24 h. The levels of IFN-β, IL-28A, and IL-29 mRNAs were examined by real-time PCR and normalized to the level of GAPDH. (I) Immunoblot analysis of nuclear (nul) and cytoplasmic (cyt) extracts of HEK293T cells cotransfected with IRF3-5D and p3×Flag-CMV-vector or p3×Flag-CMV-IRF1. Experiments were independently repeated two or three times, with similar results. Data are presented as means ± SD from three biological replicates. *, P < 0.05 versus the control; **, P < 0.01 versus the control; ***, P < 0.001 versus the control (by Student’s two-sided t test).

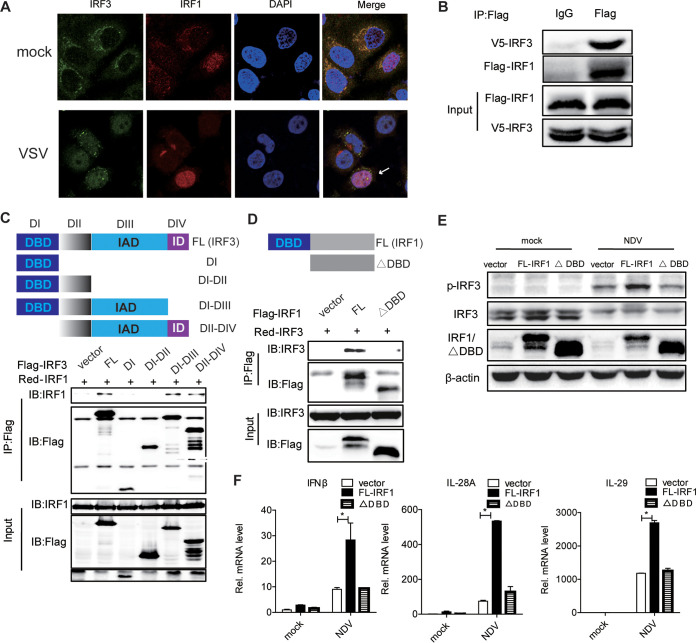

IRF1 promotes the innate immune response to viral infection by targeting IRF3.

To test our hypothesis, we performed the following experiments. First, we detected the locations of the IRF1 and IRF3 proteins in the cells. The immunofluorescence data demonstrated that IRF1 colocalized with IRF3 in the cytoplasm. IRF3 translocated to the nucleus and colocalized with IRF1 in the nucleus after VSV infection (Fig. 6A). Second, coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) assays confirmed that IRF1 interacted with IRF3 in HEK293T cells (Fig. 6B). To better understand the molecular mechanism of IRF1-mediated IRF3 function, we constructed a series of truncations of IRF3 and cotransfected them with full-length IRF1 in HEK293T cells (Fig. 6C). We found that IRF1 interacts with the IRF association domain (IAD) of IRF3 (Fig. 6C). The depletion of the DBD of IRF1 influenced the interaction between IRF1 and IRF3, suggesting that the DBD of IRF1 is responsible for the interaction between IRF1 and IRF3 (Fig. 6D). Our data supported that IRF1 targets IRF3 and that the DBD of IRF1 is sufficient for its interaction with the DBD of IRF3. Functionally, the DBD of IRF1 is necessary for the activation of the phosphorylation of IRF3 and the induction of IFNs by viral infection (Fig. 6E and F). Taken together, our data suggested that IRF1 promotes the innate immune response to viral infection by targeting IRF3.

FIG 6.

IRF1 interacts with IRF3. (A) The subcellular localization of endogenous IRF1 and IRF3 was analyzed by fluorescence microscopy in Huh7 cells infected with VSV or not. The arrows highlight the nuclear colocalization of IRF3 and IRF1 by immunofluorescence staining. (B) HEK293T cells were cotransfected with pIRF1-Flag and pIRF3-V5 for 48 h. IP and immunoblot assays were performed with the indicated antibodies. (C and D) HEK293T cells were cotransfected with pIRF1-RFP and pIRF3-Flag mutants (C) or with pIRF3-RFP and pIRF1-Flag mutants (D) for 48 h. IP and immunoblot (IB) assays were performed with the indicated antibodies. DI, domain I; FL, full length; ID, inhibitory domain of IRF3. (E) Huh7 cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids for 24 h and then infected with NDV for 24 h. Immunoblot assays were performed with the indicated antibodies. (F) Huh7 cells were treated as described above for panel E. The levels of IFN-β, IL-28A, and IL-29 mRNAs were examined by real-time PCR and normalized to the level of GAPDH. Experiments were independently repeated two or three times, with similar results. Data are presented as means ± SD from three biological replicates. *, P < 0.05 versus the control (by Student’s two-sided t test).

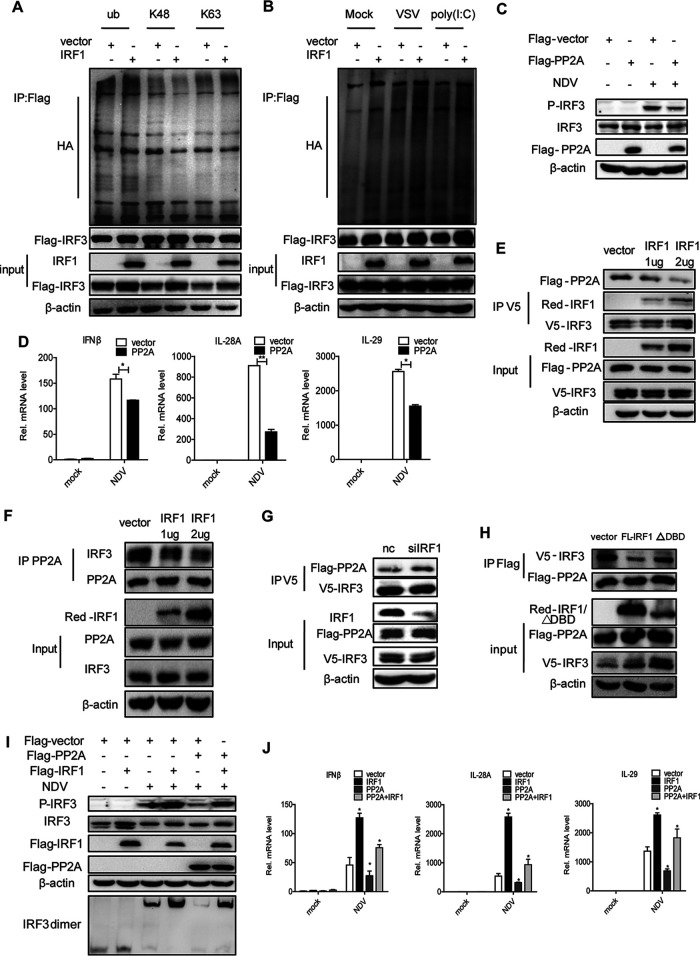

IRF1 promotes the innate immune response to viral infection by blocking the IRF3-PP2A interaction and subsequently augmenting the activation of IRF3.

Previous studies demonstrated that the ubiquitination of IRF3 may affect its activity. Our data showed that the ectopic expression of IRF1 did not impact the ubiquitination of IRF3 on K48 and K63 and the ubiquitination of IRF3 induced by VSV and poly(I·C) (Fig. 7A and B). Next, we focused on the serine and threonine protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), which is a phosphatase for IRF3. To verify the function of PP2A on phosphorylated IRF3, we delivered pFlag-PP2A into Huh7 cells and infected the cells with NDV. Our data confirmed that PP2A indeed attenuated the activation of phosphorylated IRF3 by viral infection (Fig. 7C). Consistently, PP2A also impaired the production of IFNs triggered by viral infection (Fig. 7D). Interestingly, the overexpression of IRF1 abolished the interaction between PP2A and IRF3 in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 7E and F). The silencing of IRF1 augmented the PP2A and IRF3 interaction (Fig. 7G). The depletion of the DBD of IRF1 led to a loss of its negative role in the interaction between PP2A and IRF3 (Fig. 7H). Based on the above-described data, we speculated that IRF1 enhances the phosphorylation of IRF3 by suppressing the interaction between IRF3 and PP2A. Consistent with our assumption, the overexpression of IRF1 impaired the ability of PP2A to block the activation of phosphorylated IRF3 (Fig. 7I) and the production of IFNs triggered by viral infection (Fig. 7J). All the data suggested that IRF1 blocks the IRF3-PP2A interaction and subsequently augments the activation of IRF3, thereby enhancing the innate immune response to viral infection.

FIG 7.

IRF1 promotes the innate immune response to viral infection by blocking the IRF3-PP2A interaction and subsequently augmenting the activation of IRF3. (A) HEK293T cells were cotransfected with the indicated plasmids for 42 h and treated with 25 μM MG132 for an additional 6 h. Ubiquitination (ub) and immunoblot assays were performed with the indicated antibodies. (B) HEK293T cells were cotransfected with the indicated plasmids for 36 h, induced with poly(I·C) or VSV, and treated with 25 μM MG132 for an additional 6 h. Ubiquitination and immunoblot assays were performed with the indicated antibodies. (C and D) Huh7 cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids for 24 h and then infected with NDV for 24 h. (C) Immunoblot assays were performed with the indicated antibodies. (D) The levels of IFN-β, IL-28A, and IL-29 mRNAs were examined by real-time PCR and normalized to the level of GAPDH. (E to H) HEK293T (E and H) and Huh7 (F and G) cells were cotransfected with the indicated plasmids for 48 h. IP and immunoblot assays were performed with the indicated antibodies. (I and J) Huh7 cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids for 24 h and then infected with NDV for 24 h. (I) Immunoblot assays were performed with the indicated antibodies. (J) The levels of IFN-β, IL-28A, and IL-29 mRNAs were examined by real-time PCR and normalized to the level of GAPDH. Experiments were independently repeated two or three times, with similar results. Data are presented as means ± SD from three biological replicates. *, P < 0.05 versus the control; **, P < 0.01 versus the control (by Student’s two-sided t test).

DISCUSSION

Our recent studies show that both TRIM21 and long noncoding RNA ITPRIP-1 (lncITPRIP-1) promote the innate immune response to viral infection. TRIM21 promotes the innate immune response via K27-linked polyubiquitination of MAVS, thereby inhibiting viral infection (30). lncITPRIP-1 enhances the innate immune response to viral infection through the promotion of the oligomerization and activation of MDA5 (31). To disclose new factors that regulate the innate immune response to viral infection, we performed RNA sequencing and found that IRF1 might be involved in the innate immune response.

The present study shows that IRF1 promotes the innate immune response to viral infection by enhancing the activation of IRF3, thereby inhibiting viral infection. Our study provides five solid lines of evidence that IRF1 plays an important role in innate immunity. First, IRF1 can be induced by DNA and RNA virus infections in a JAK/STAT pathway-dependent manner, suggesting that IRF1 may play a role in the IFN signaling pathway. Second, the ectopic expression or silencing of IRF1 enhances or attenuates the production of IFNs and ISGs triggered by viral infection, respectively, pointing out that IRF1 promotes the innate immune response to viral infection. Third, IRF1 augments the activation of IRF3 by viral infection. Fourth, the DBD of IRF1 is necessary for the activation of the phosphorylation of IRF3 and the induction of IFNs by viral infection. IRF1 promotes the innate immune response to viral infection by targeting IRF3. Fifth, PP2A attenuates the activation of phosphorylated IRF3 by viral infection. The overexpression of IRF1 impairs the ability of PP2A to block the activation of phosphorylated IRF3.

The function of IRF1 in innate immunity has received great attention recently. Whether IRF1 can induce the production of IFN in response to viral infection remains controversial. IRF1 KO mice fail to impair IFN-β production (24). IRF1 controls the induction of type III IFN by many pathogens (25, 26). IRF1 and IRF3 are activated independently of each other (27). One recent study showed that constitutively expressed IRF1 provides intrinsic antiviral protection independent of MAVS, IRF3, and STAT1 signaling (32). No report has described the mechanism of IRF1 in inducing the production of IFN. Our study shows that IRF1 induces type I and type III IFNs upon viral infection.

The regulation of IRF3 activity is a key step in innate immunity. The activity of IRF3 can be regulated by ubiquitination and the upstream kinases TBK1 and IKKε (16). Our study demonstrates that IRF1 has no effect on the ubiquitination of IRF3 and the interaction between IRF3 and TBK1. Our data show that IRF1 knockdown inhibits the phosphorylation of IRF3 activated by viral infection.

In this study, we found that IRF1 can be induced by viral infection in a JAK-STAT-dependent manner. IRF1 promotes the antiviral immune response by augmenting the phosphorylation of IRF3 and the production of IFNs triggered by viral infection. Mechanistically, IRF1 blocks the interaction between IRF3 and PP2A to enhance IRF3 activation (Fig. 8). Collectively, the results of our study provide new insight into the regulation of IRF3 signaling and uncover the role of IRF1 in the positive regulation of the innate immune response to viral infection.

FIG 8.

Schematic model of IRF1-mediated promotion of the innate immune response to viral infection. IRF1 is induced by viral infection. IRF1 targets and augments the phosphorylation of IRF3 by blocking the interaction between IRF3 and PP2A, thereby promoting the innate immune response to viral infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and reagents.

The HLCZ01 cell line, a hepatoma cell line supporting the entire life cycle of HCV and HBV, was previously established in our laboratory (29). HEK293T cells were purchased from Boster. Huh7 and A549 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. HLCZ01 cells were cultured in collagen-coated tissue culture plates containing Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM)–F-12 medium supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco), 40 ng/ml of dexamethasone (Sigma), insulin-transferrin-selenium (ITS) (Lonza), penicillin, and streptomycin. Other cells were propagated in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, l-glutamine, nonessential amino acid, penicillin, and streptomycin.

Antibodies.

Monoclonal antibodies against β-actin, the Flag tag, and the hemagglutinin (HA) tag were obtained from Sigma. The V5 tag monoclonal antibody was purchased from Invitrogen. Monoclonal antibody against MAVS was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. The antibodies for IRF1, MDA5, RIG-I, TBK1, p-IRF3, IRF3, p-p65, and p65 and the secondary antibody goat anti-rabbit IgG-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP secondary antibody was purchased from Merck.

Plasmids construction.

The short hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting IRF1 was constructed in the pSilencer-neo plasmid (Ambion). The target sequence of IRF1 shRNA was 5′-GCTAGAGATGCAGATTAAT-3′. Multiple domains of IRF1 and IRF3 were amplified from the templates of full-length IRF1 and IRF3, which were cloned into p3×FLAG-CMV. The primers for amplifying these genes are listed in Table 1. The IFN-β–luciferase plasmid was purchased from InvivoGen. pFlag-MDA5 and pGL3-NF-κB-Luciferase were kindly shared by Jianguo Wu (Wuhan University, Wuhan, China). The plasmid pFlag-IRF3-5D was a gift from Deyin Guo (Wuhan University, Wuhan, China). The plasmids pFlag-TBK1 and pHA-Ub (K48 and K63) were kindly provided by Zhengfan Jiang (Peking University, Beijing, China).

TABLE 1.

Primers for the construction of plasmidsa

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| IRF1 (F) | 5′-CGGAATTCATGCCCATCACTCGGATGCG-3′ |

| IRF1 (R) | 5′-GCTCTAGACGGTGCACAGGGAATGGCCT-3′ |

| IRF1 ΔDBD (F) | 5′-CGGAATTCATGACCAAGAACCAGAGAAAAGA-3′ |

| IRF1 ΔDBD (R) | 5′-GCTCTAGACGGTGCACAGGGAATGGCCT-3′ |

| IRF3 (F) | 5′-CGGAATTCATGGGAACCCCAAAGCCACG-3′ |

| IRF3 (R) | 5′-GCTCTAGAGCTCTCCCCAGGGCCCTGGA-3′ |

| IRF3-DI (F) | 5′-CGGAATTCATGGGAACCCCAAAGCCACG-3′ |

| IRF3-DI (R) | 5′-GCTCTAGATGGCTGGGAAAAGTCCCCAA-3′ |

| IRF3-DI-DII (F) | 5′-CGGAATTCATGGGAACCCCAAAGCCACG-3′ |

| IRF3-DI-DII (R) | 5′-GCTCTAGAGTTCTCAGAGGGCCCCAGGT-3′ |

| IRF3-DI-DIII (F) | 5′-CGGAATTCATGGGAACCCCAAAGCCACG-3′ |

| IRF3-DI-DIII (R) | 5′-GCTCTAGAGGAGGCACCCCCTACCCGGG-3′ |

| IRF3-DII-DIV (F) | 5′-CGGAATTCATGGGAACCCCAAAGCCACG-3′ |

| IRF3-DII-DIV (R) | 5′-CGGAATTCATGGACACCTCTCCGGACACCAA-3′ |

| PP2A (F) | 5′-CGGAATTCATGGACGAGAAGGTGTTCAC-3′ |

| PP2A (R) | 5′-CGGGATCCCAGGAAGTAGTCTGGGGTAC-3′ |

F, forward; R, reverse.

Real-time PCR assay.

Total cellular RNA was extracted by using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The SuperScript III first-strand synthesis kit for the reverse transcription of RNA was purchased from Invitrogen. After RQ1 DNase (Promega) treatment, extracted RNA was used as the template for reverse transcription-PCR. Real-time PCR was performed as described previously (29). The primers for IRF1, NDV, IFN-β, IL-28A, IL-29, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), MX1, and ISG15 are presented in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Primers for qRT-PCR

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| IRF1 (F) | 5′-ACCCTGGCTAGAGATGCAGA-3′ |

| IRF1 (R) | 5′-TGCTTTGTATCGGCCTGTGT-3′ |

| IFNβ (F) | 5′-CAGCAATTTTCAGTGTCAGAAGC-3′ |

| IFNβ (R) | 5′-TCATCCTGTCCTTGAGGCAGT-3′ |

| IL-28A (F) | 5′-GCCTCAGAGTGTTTCTTCTGC-3′ |

| IL-28A (R) | 5′-AAGGCATCTTTGGCCCTCTT-3′ |

| IL-29 (F) | 5′-CGCCTTGGAAGAGTCACTCA-3′ |

| IL-29 (R) | 5′-GAAGCCTCAGGTCCCAATTC-3′ |

| GAPDH (F) | 5′-GCACCGTCAAGGCTGAGAAC-3′ |

| GAPDH (R) | 5′-TGGTGAAGACGCCAGTGGA-3′ |

| NDV (F) | 5′-TCACAGACTCAACTCTTGGG-3′ |

| NDV (R) | 5′-CAGTATGAGGTGTCAAGTTCTTC-3′ |

| MX1 (F) | 5′-CAACCTGTGCAGCCAGTATGA-3′ |

| MX1 (R) | 5′-AGCCCGCAGGGAGTCAAT-3′ |

| ISG15 (F) | 5′-CACCGTGTTCATGAATCTGC-3′ |

| ISG15 (R) | 5′-CTTTATTTCCGGCCCTTGAT-3′ |

Western blotting.

Cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer including 150 mM sodium chloride, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, and 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) supplemented with 2 μg/ml of aprotinin, 2 μg/ml of leupeptin, 20 μg/ml of phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). Protein was resolved in an SDS-PAGE gel, transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane, and probed with appropriate primary and secondary antibodies. The bound antibodies were detected by using the SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Luciferase assay.

Luciferase activity was measured with the dual-luciferase reporter assay system (Promega). The luciferase activity in cells was normalized to the protein concentration determined by Bradford assays (33).

IP and immunoblotting.

Cells were washed three times with ice-cold PBS and lysed in lysis buffer supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail. The cell lysates were incubated at 4°C for 30 min and centrifuged at 12,000 × g at 4°C for 15 min. Lysates were diluted to a concentration of 2 μg/μl with PBS before immunoprecipitation. Lysates (400 μg) were immunoprecipitated with the indicated antibodies. The immunocomplex was captured by adding a protein G-agarose bead slurry. The protein binding to the beads was boiled in 2× Laemmli sample buffer and then subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE.

Native PAGE.

Native PAGE for the detection of IRF3 dimerization was performed on a 7.5% acrylamide gel without SDS. Cells were harvested with 60 μl ice-cold lysis buffer including 50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.5% NP-40 containing a protease inhibitor cocktail. After centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 15 min, the protein in the supernatant was quantified and diluted with 5× native PAGE sample buffer (312.5 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 75% glycerol, 0.25% bromophenol blue). The gel was prerun for 30 min at 40 mA on ice with 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.4) and 192 mM glycine with or without 1% deoxycholate in the cathode chamber or anode chamber, respectively. The unboiled total protein was added to the gel for 80 min at 25 mA on ice.

Nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction.

Cells were washed once with ice-cold PBS and lysed in lysis buffer A (150 mM KCl, 25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 5 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM DTT) supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail. The cell lysates were incubated at 4°C for 15 min and centrifuged at 1,000 × g at 4°C for 5 min. The supernatant is cytoplasmic, and the sediment was washed three times with ice-cold PBS and vibrated three times. Next, the sediment was lysed in lysis buffer B (500 mM KCl, 25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 2 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, 0.1% SDS). Nuclear and cytoplasmic lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 17,000 × g for 10 min.

Immunofluorescence staining.

Cells were seeded in a glass-bottom dish and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde fix solution for 15 min at room temperature. The cells were washed with PBS, permeabilized for 15 min with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS, blocked with goat serum for 30 min at room temperature, and then incubated for 2 h with mouse monoclonal anti-IRF3 antibody (diluted in PBS to 1:10) and rabbit monoclonal anti-IRF1 antibody (diluted in PBS to 1:200). The cells were stained with fluorescence-labeled secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) (diluted in PBS to 1:500) for 2 h at room temperature. The cells were extensively washed, and the nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA). Fluorescence images were obtained under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Japan).

Statistical analysis.

Experiments were independently repeated two or three times, with similar results. Statistical analysis was performed by Student’s two-sided t test, and data are presented as means ± standard deviations (SD) with three biological replicates.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Charles M. Rice for Huh7.5 cells. We appreciate Chen Liu, Hongbing Shu, Jianguo Wu, Zhengfan Jiang, and Deyin Guo for kindly sharing research materials.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81730064, 81571985, and 81902069) and the National Science and Technology Major Project (2017ZX10202201).

REFERENCES

- 1.Liu J, Cao X. 2016. Cellular and molecular regulation of innate inflammatory responses. Cell Mol Immunol 13:711–721. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2016.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cao X. 2016. Self-regulation and cross-regulation of pattern-recognition receptor signalling in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol 16:35–50. doi: 10.1038/nri.2015.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takeuchi O, Akira S. 2010. Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell 140:805–820. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kawai T, Takahashi K, Sato S, Coban C, Kumar H, Kato H, Ishii KJ, Takeuchi O, Akira S. 2005. IPS-1, an adaptor triggering RIG-I- and Mda5-mediated type I interferon induction. Nat Immunol 6:981–988. doi: 10.1038/ni1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meylan E, Curran J, Hofmann K, Moradpour D, Binder M, Bartenschlager R, Tschopp J. 2005. Cardif is an adaptor protein in the RIG-I antiviral pathway and is targeted by hepatitis C virus. Nature 437:1167–1172. doi: 10.1038/nature04193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seth RB, Sun L, Ea CK, Chen ZJ. 2005. Identification and characterization of MAVS, a mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein that activates NF-kappaB and IRF 3. Cell 122:669–682. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu LG, Wang YY, Han KJ, Li LY, Zhai Z, Shu HB. 2005. VISA is an adapter protein required for virus-triggered IFN-beta signaling. Mol Cell 19:727–740. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoneyama M, Kikuchi M, Natsukawa T, Shinobu N, Imaizumi T, Miyagishi M, Taira K, Akira S, Fujita T. 2004. The RNA helicase RIG-I has an essential function in double-stranded RNA-induced innate antiviral responses. Nat Immunol 5:730–737. doi: 10.1038/ni1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borden EC, Sen GC, Uze G, Silverman RH, Ransohoff RM, Foster GR, Stark GR. 2007. Interferons at age 50: past, current and future impact on biomedicine. Nat Rev Drug Discov 6:975–990. doi: 10.1038/nrd2422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tailor P, Tamura T, Ozato K. 2006. IRF family proteins and type I interferon induction in dendritic cells. Cell Res 16:134–140. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoneyama M, Suhara W, Fujita T. 2002. Control of IRF-3 activation by phosphorylation. J Interferon Cytokine Res 22:73–76. doi: 10.1089/107999002753452674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hiscott J. 2007. Triggering the innate antiviral response through IRF-3 activation. J Biol Chem 282:15325–15329. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700002200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang P, Zhao W, Zhao K, Zhang L, Gao C. 2015. TRIM26 negatively regulates interferon-beta production and antiviral response through polyubiquitination and degradation of nuclear IRF3. PLoS Pathog 11:e1004726. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lei CQ, Zhang Y, Xia T, Jiang LQ, Zhong B, Shu HB. 2013. FoxO1 negatively regulates cellular antiviral response by promoting degradation of IRF3. J Biol Chem 288:12596–12604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.444794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang M, Tian Y, Wang RP, Gao D, Zhang Y, Diao FC, Chen DY, Zhai ZH, Shu HB. 2008. Negative feedback regulation of cellular antiviral signaling by RBCK1-mediated degradation of IRF3. Cell Res 18:1096–1104. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang H, Han C, Li T, Li N, Cao X. 2019. The methyltransferase PRMT6 attenuates antiviral innate immunity by blocking TBK1-IRF3 signaling. Cell Mol Immunol 16:800–809. doi: 10.1038/s41423-018-0057-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Long L, Deng Y, Yao F, Guan D, Feng Y, Jiang H, Li X, Hu P, Lu X, Wang H, Li J, Gao X, Xie D. 2014. Recruitment of phosphatase PP2A by RACK1 adaptor protein deactivates transcription factor IRF3 and limits type I interferon signaling. Immunity 40:515–529. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou Y, Li M, Xue Y, Li Z, Wen W, Liu X, Ma Y, Zhang L, Shen Z, Cao X. 2019. Interferon-inducible cytoplasmic lncLrrc55-AS promotes antiviral innate responses by strengthening IRF3 phosphorylation. Cell Res 29:641–654. doi: 10.1038/s41422-019-0193-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peng D, Wang Z, Huang A, Zhao Y, Qin FX. 2017. A novel function of F-box protein FBXO17 in negative regulation of type I IFN signaling by recruiting PP2A for IFN regulatory factor 3 deactivation. J Immunol 198:808–819. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watanabe N, Sakakibara J, Hovanessian AG, Taniguchi T, Fujita T. 1991. Activation of IFN-beta element by IRF-1 requires a posttranslational event in addition to IRF-1 synthesis. Nucleic Acids Res 19:4421–4428. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.16.4421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dou L, Liang HF, Geller DA, Chen YF, Chen XP. 2014. The regulation role of interferon regulatory factor-1 gene and clinical relevance. Hum Immunol 75:1110–1114. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2014.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nozawa H, Oda E, Nakao K, Ishihara M, Ueda S, Yokochi T, Ogasawara K, Nakatsuru Y, Shimizu S, Ohira Y, Hioki K, Aizawa S, Ishikawa T, Katsuki M, Muto T, Taniguchi T, Tanaka N. 1999. Loss of transcription factor IRF-1 affects tumor susceptibility in mice carrying the Ha-ras transgene or nullizygosity for p53. Genes Dev 13:1240–1245. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.10.1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miyamoto M, Fujita T, Kimura Y, Maruyama M, Harada H, Sudo Y, Miyata T, Taniguchi T. 1988. Regulated expression of a gene encoding a nuclear factor, IRF-1, that specifically binds to IFN-beta gene regulatory elements. Cell 54:903–913. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(88)91307-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reis LF, Ruffner H, Stark G, Aguet M, Weissmann C. 1994. Mice devoid of interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF-1) show normal expression of type I interferon genes. EMBO J 13:4798–4806. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06805.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ueki IF, Min-Oo G, Kalinowski A, Ballon-Landa E, Lanier LL, Nadel JA, Koff JL. 2013. Respiratory virus-induced EGFR activation suppresses IRF1-dependent interferon lambda and antiviral defense in airway epithelium. J Exp Med 210:1929–1936. doi: 10.1084/jem.20121401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siegel R, Eskdale J, Gallagher G. 2011. Regulation of IFN-lambda1 promoter activity (IFN-lambda1/IL-29) in human airway epithelial cells. J Immunol 187:5636–5644. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Odendall C, Dixit E, Stavru F, Bierne H, Franz KM, Durbin AF, Boulant S, Gehrke L, Cossart P, Kagan JC. 2014. Diverse intracellular pathogens activate type III interferon expression from peroxisomes. Nat Immunol 15:717–726. doi: 10.1038/ni.2915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu L, Zhou X, Wang W, Wang Y, Yin Y, Laan LJ, Sprengers D, Metselaar HJ, Peppelenbosch MP, Pan Q. 2016. IFN regulatory factor 1 restricts hepatitis E virus replication by activating STAT1 to induce antiviral IFN-stimulated genes. FASEB J 30:3352–3367. doi: 10.1096/fj.201600356R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang D, Zuo C, Wang X, Meng X, Xue B, Liu N, Yu R, Qin Y, Gao Y, Wang Q, Hu J, Wang L, Zhou Z, Liu B, Tan D, Guan Y, Zhu H. 2014. Complete replication of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus in a newly developed hepatoma cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:E1264–E1273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320071111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xue B, Li H, Guo M, Wang J, Xu Y, Zou X, Deng R, Li G, Zhu H. 2018. TRIM21 promotes innate immune response to RNA viral infection through Lys27-linked polyubiquitination of MAVS. J Virol 92:e00321-18. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00321-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xie Q, Chen S, Tian R, Huang X, Deng R, Xue B, Qin Y, Xu Y, Wang J, Guo M, Chen J, Tang S, Li G, Zhu H. 2018. Long noncoding RNA ITPRIP-1 positively regulates the innate immune response through promotion of oligomerization and activation of MDA5. J Virol 92:e00507-18. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00507-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamane D, Feng H, Rivera-Serrano EE, Selitsky SR, Hirai-Yuki A, Das A, McKnight KL, Misumi I, Hensley L, Lovell W, Gonzalez-Lopez O, Suzuki R, Matsuda M, Nakanishi H, Ohto-Nakanishi T, Hishiki T, Wauthier E, Oikawa T, Morita K, Reid LM, Sethupathy P, Kohara M, Whitmire JK, Lemon SM. 2019. Basal expression of interferon regulatory factor 1 drives intrinsic hepatocyte resistance to multiple RNA viruses. Nat Microbiol 4:1096–1104. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0425-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bradford MM. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]