Despite the administration of antiretroviral therapy (ART), HIV persists in treated individuals and ART interruption is associated with viral rebound. Persistent chronic immune activation and inflammation contribute to disease morbidity. Whereas monocytes are infected by HIV/SIV, their role as viral reservoirs (VRs) in visceral tissues has been poorly explored. Our work demonstrates that monocyte cell subsets in the blood, spleen, and intestines do not significantly contribute to the establishment of early VRs in SIV-infected rhesus macaques treated with ART. By preventing the infection of these cells, early ART reduces systemic inflammation. However, following ART interruption, monocytes are rapidly reinfected. Altogether, our findings shed new light on the benefits of early ART initiation in limiting VR and inflammation.

KEYWORDS: HIV, SIV, viral reservoir, antiretroviral therapy, monocytes, CD4, spleen, intestine, IL-18, IL-1ra, inflammation

ABSTRACT

Despite early antiretroviral therapy (ART), treatment interruption is associated with viral rebound, indicating early viral reservoir (VR) seeding and absence of full eradication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV‐1) that may persist in tissues. Herein, we address the contributing role of monocytes in maintaining VRs under ART, since these cells may represent a source of viral dissemination due to their ability to replenish mucosal tissues in response to injury. To this aim, monocytes with classical (CD14+), intermediate (CD14+ CD16+), and nonclassical (CD16+) phenotypes and CD4+ T cells were sorted from the blood, spleen, and intestines of untreated and early-ART-treated simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-infected rhesus macaques (RMs) before and after ART interruption. Cell-associated SIV DNA and RNA were quantified. We demonstrated that in the absence of ART, monocytes were productively infected with replication-competent SIV, especially in the spleen. Reciprocally, early ART efficiently (i) prevented the establishment of monocyte VRs in the blood, spleen, and intestines and (ii) reduced systemic inflammation, as indicated by changes in interleukin-18 (IL-18) and IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra) plasma levels. ART interruption was associated with a rebound in viremia that led to the rapid productive infection of both CD4+ T cells and monocytes. Altogether, our results reveal the benefits of early ART initiation in limiting the contribution of monocytes to VRs and SIV-associated inflammation.

IMPORTANCE Despite the administration of antiretroviral therapy (ART), HIV persists in treated individuals and ART interruption is associated with viral rebound. Persistent chronic immune activation and inflammation contribute to disease morbidity. Whereas monocytes are infected by HIV/SIV, their role as viral reservoirs (VRs) in visceral tissues has been poorly explored. Our work demonstrates that monocyte cell subsets in the blood, spleen, and intestines do not significantly contribute to the establishment of early VRs in SIV-infected rhesus macaques treated with ART. By preventing the infection of these cells, early ART reduces systemic inflammation. However, following ART interruption, monocytes are rapidly reinfected. Altogether, our findings shed new light on the benefits of early ART initiation in limiting VR and inflammation.

INTRODUCTION

Monocytes that develop in the bone marrow from dividing monoblasts are released into the bloodstream and exhibit developmental plasticity, with the capability of in vivo and in vitro differentiation into either macrophages or dendritic cells (DCs), depending on the cytokine milieu (1, 2). Blood monocytes consist of subsets with distinct phenotypic and functional characteristics. The expression of CD14 (lipopolysaccharide [LPS] coreceptor) and CD16 (FcγRIII) distinguishes classical (CD14++ CD16−), intermediate (CD14++ CD16+), and nonclassical (CD14+/− CD16+) monocyte subsets (3). The CD16 subset expresses CX3CR1 and migrates into the tissues in response to CX3CL1, whereas the CD14 population expresses CCR1 and CCR2 and migrates in response to CCL2 and CCL3 (4). There is some evidence that monocytes in the blood are essential for the replenishment of macrophages in the intestines, in which CCR2 is also essential (5, 6). In addition, the pool of splenic monocytes represents a large reservoir of undifferentiated cells that can be mobilized in response to injury (7). The recruitment of monocytes into lymphoid tissues and their local differentiation can be induced in response to inflammatory reactions, particularly during microbial infections (8). Overall, monocytes are innate sentinels that are essential to effective host protection against microbial infections (9).

Monocytes express both the CD4 molecule and chemokine coreceptors, which are important for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infections (10–12). During HIV infection, the population of CD14+ monocyte subsets expressing CD16 is increased (13) and associated with neuropathogenesis (14, 15). These cells, which exhibit phenotypic and functional dendritic cell-like characteristics (16, 17), can efficiently transfer HIV to activated CD4+ T cells (18). HIV‐1 DNA is present in <1% of blood monocytes in infected patients (19, 20) and is detected early after infection (21). Whereas levels of viral DNA are similar between the different subsets of monocytes, the levels of viral RNA are higher in blood CD14+ monocytes than in the other subsets (22–25). Although blood monocytes are noncycling and nonproliferating cells, it has been established that productive infection coincides with entry into the G1/S phase of the cell cycle, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) is one of the main cytokines that promotes and sustains productive infection (21, 26–29). Importantly, in vivo myeloid cells support high levels of viral replication, especially during bacterial infection (30) or when T cells have been depleted (31–33). It was also previously reported that the extent of viral production by myeloid cells discriminated macaques developing encephalitis, but not the level of viral DNA (34). Studies in humanized mouse models devoid of T cells have also indicated the role of tissue macrophages in sustaining viral replication (35). These results can be consistent with the observation that levels of monocyte activation, as judged by either bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation or Ki-67 expression, are increased early after infection and remain elevated during the progression to AIDS (36–38). Thus, the extent of viral RNA in monocytes is a marker of viral pathogenesis.

The administration of antiretroviral drugs has an enormous positive impact on mortality and morbidity in HIV-1 infections. In HIV-infected individuals under antiretroviral treatment (ART) with prolonged viral suppression, low‐levels of viral replication in blood monocytes have been reported (22, 39–41), preferentially in CD16+ monocytes (42). Recently, results obtained by Cattin et al. from a cohort of ART-treated individuals indicated that the presence of HIV DNA in myeloid cells from the blood or the sigmoid colon is rare (43). In contrast, Honeycutt et al. indicated the absence of viral DNA in peripheral blood monocytes of HIV-infected individuals receiving ART (35). Nevertheless, people living with HIV still present persistent chronic immune activation and inflammation that contribute to disease morbidity, thus supporting an indirect role of myeloid cells in HIV pathogenesis (44, 45) and, eventually, viral reservoir (VR) persistence in CD4+ T cells. Interruption of ART (ATI) is associated with viral rebound (46), even after early ART initiation (47–49), indicating the absence of full eradication of HIV‐1 that may persist in tissues. Using a model of humanized myeloid-only mice, it has been proposed that persistent infection of myeloid cells is essential and responsible for viral rebound (35). Furthermore, a recent report indicates that despite ART administered in SIV-infected rhesus macaques (RMs), viral DNA persists in macrophages in the blood and lungs (50). Therefore, regarding the lower risk of development of non-AIDS morbidities observed after early ART (51), a key question is the role of early ART on the clearance of infection in myeloid cells. Whereas most of the previous studies have been performed on peripheral blood, few studies have addressed the contributing role of splenic monocytes, which may represent a major source of viral dissemination due to their physiological role in replenishing the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) in response to injury (7). Because testing this cannot be easily performed in human subjects, particularly to measure the impact of early ART on viral dissemination in such myeloid cells, we decided to analyze these events in a model of nonhuman primates infected with SIVmac251.

Here, we examined viral DNA and RNA in monocyte subsets isolated from SIV-infected RMs. Because VRs are established early after infection, animals were also treated with a cocktail of antiretroviral drugs administered at day 4 postinfection. We provide evidence that early ART initiation efficiently controls the viral infection of monocytes, both in the spleen and intestines, and reduces systemic inflammation. Thus, monocytes in these compartments cannot contribute to viral rebound observed after ATI. Concomitantly with viral rebound, we observed early viral infection of monocytes, which display both viral DNA and RNA. Also, our results indicate that monocytic cell subsets, with their short life span, cannot be potent VRs after early ART but instead are early targets of infection once ART is interrupted.

RESULTS

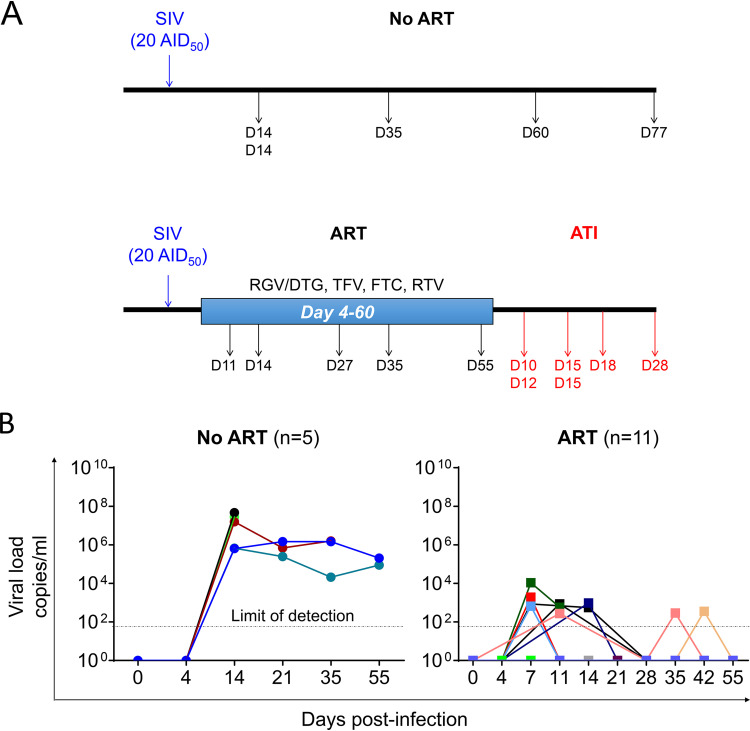

Viral dynamics in SIV-infected RMs upon early ART initiation.

Recent reports have shown that treatment administered early after infection did not completely eradicate the viral reservoir in RMs, as proven by viral rebound after ATI (47–49). In the work described herein, at day 4 postinfection, we administered a cocktail of ART to SIVmac251-infected RMs of Chinese origin (20 AID50 [50% animal infectious dose] of SIVmac251 was used to infect animals by the intravenous route). ART consisted of the administration of tenofovir (TFV, 20 mg/kg of body weight; Gilead), emtricitabine (FTC, 40 mg/kg; Gilead), raltegravir (RGV, 20 mg/kg; Merck) or dolutegravir (DTG, 5 mg/kg; ViiV), and ritonavir (RTV, 20 mg/kg; Abbvie) (Fig. 1A). Whereas ART-naive RM viremia reached 106 to 108 copies/ml, as expected, viremia was strongly decreased in the presence of ART (Fig. 1B). Among the 11 ART-treated RMs, only half demonstrated a blip, and viral load (VL) in most cases reached 102 copies/ml. Five RMs were sacrificed while under ART (at days 11, 14, 27, 35, and 55 postinfection). Only one RM, R110806, which was sacrificed at day 11 after infection and treated with only 7 daily doses of ART, had a detectable VL (5.8 102 copies/ml). All the other animals had negative VLs at the time of sacrifice (the limit of detection is 50 copies/ml) (Table 1).

FIG 1.

Study protocol and viral loads. (A) Sixteen rhesus macaques (RMs) were infected intravenously with SIVmac251 (20 AID50). At day 4 postinfection, 11 were treated with tenofovir (TFV, 20 mg/kg; Gilead) and emtricitabine (FTC, 40 mg/kg; Gilead) subcutaneously and raltegravir (RGV, 20 mg/kg; Merck) or dolutegravir (DTG, 5 mg/kg; ViiV) and ritonavir (RTV, 20 mg/kg; Abbvie) by the oral route. RMs were sacrificed at different time points postinfection during natural infection (No ART) (n = 5), under ART (ART) (n = 5), and after ART interruption (ATI) (n = 6). (B) Levels of viral load in the sera of SIV-infected RMs were quantified by qRT-PCR during natural infection (No ART) and under ART (ART). Each symbol represents the value for an individual. Results are expressed as viral load copies per ml.

TABLE 1.

Virological and immune parameters measured in the blood of SIV-infected RMsa

| Treatment status, animal | Days p.i. (No ART, ART) or post-ART (ATI) | Viral load (copies/ml) | % CD3+ CD4+ | % CD3+ CD8+ | CD4/CD8 ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No ART | |||||

| PB041 | 14 | 8.94E+06 | 65.8 | 34.2 | 1.9 |

| PB051 | 14 | 4.67E+07 | 73.8 | 26.2 | 2.8 |

| 9051222 | 35 | 1.58E+06 | 34.3 | 65.7 | 0.5 |

| 9082012 | 60 | 6.34E+03 | 27.7 | 72.3 | 0.4 |

| 122070R | 77 | 7.55E+05 | 34.8 | 65.2 | 0.5 |

| ART | |||||

| R110806 | 11 | 5.83E+02 | 60.4 | 39.6 | 1.5 |

| 111466R | 14 | <50 | 44.7 | 55.3 | 0.8 |

| R110562 | 27 | <50 | 49.4 | 50.6 | 1.0 |

| R110360 | 35 | <50 | 54.7 | 45.3 | 1.2 |

| 121836R | 55 | <50 | 41.9 | 58.1 | 0.7 |

| ATI | |||||

| R110482 | 10 | 1.10E+05 | 59.0 | 41.0 | 1.4 |

| 121888R | 12 | 7.66E+05 | 60.0 | 40.0 | 1.5 |

| R110804 | 15 | 3.71E+03 | 47.6 | 52.4 | 0.9 |

| 131134R | 15 | 3.49E+07 | 70.3 | 29.7 | 2.4 |

| 11-1430R | 18 | 3.08E+05 | 60.5 | 39.5 | 1.5 |

| 131878R | 28 | 1.48E+03 | 45.7 | 54.3 | 0.8 |

Sixteen RMs were infected with SIVmac251 and sacrificed at different time points postinfection (p.i.) in ART-naive RMs (No ART, n = 5), under ART administered at day 4 (ART, n = 5), and after ART interruption (ATI, n = 6). The table indicates the day of sacrifice, the viral load at the time of death, the frequencies of CD4 and CD8 T cells, and the ratio of CD4/CD8 in the blood.

Thus, our results are consistent with previous reports (47–49) in which ART administered early after infection was effective in controlling blood viremia.

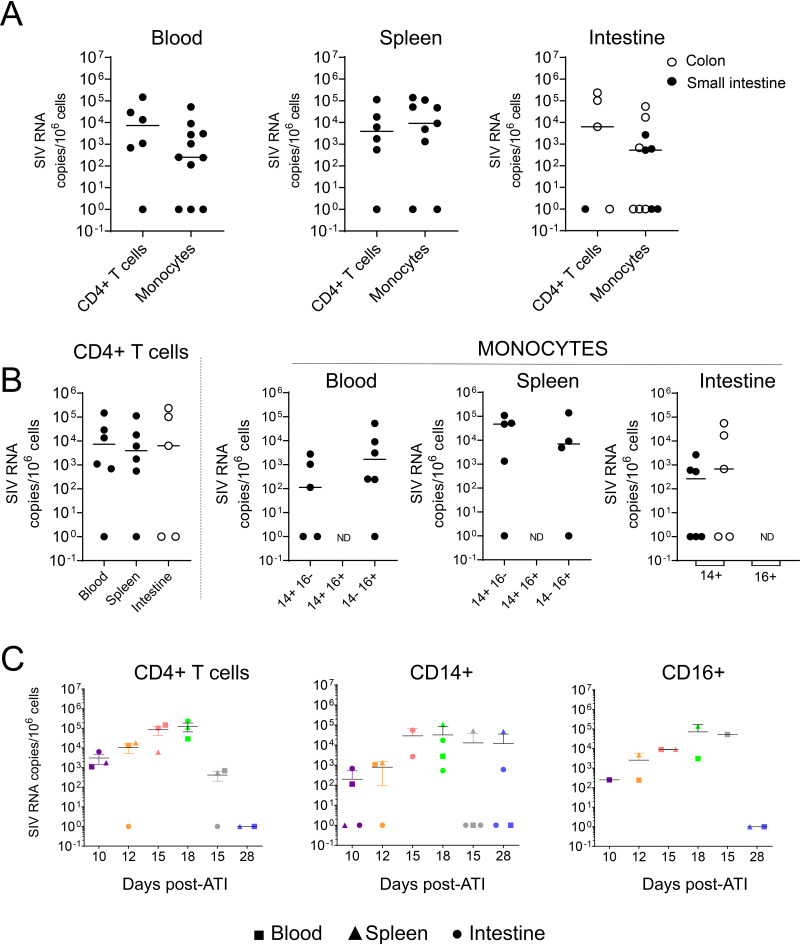

Cell-associated SIV DNA and RNA in acutely SIV-infected RMs.

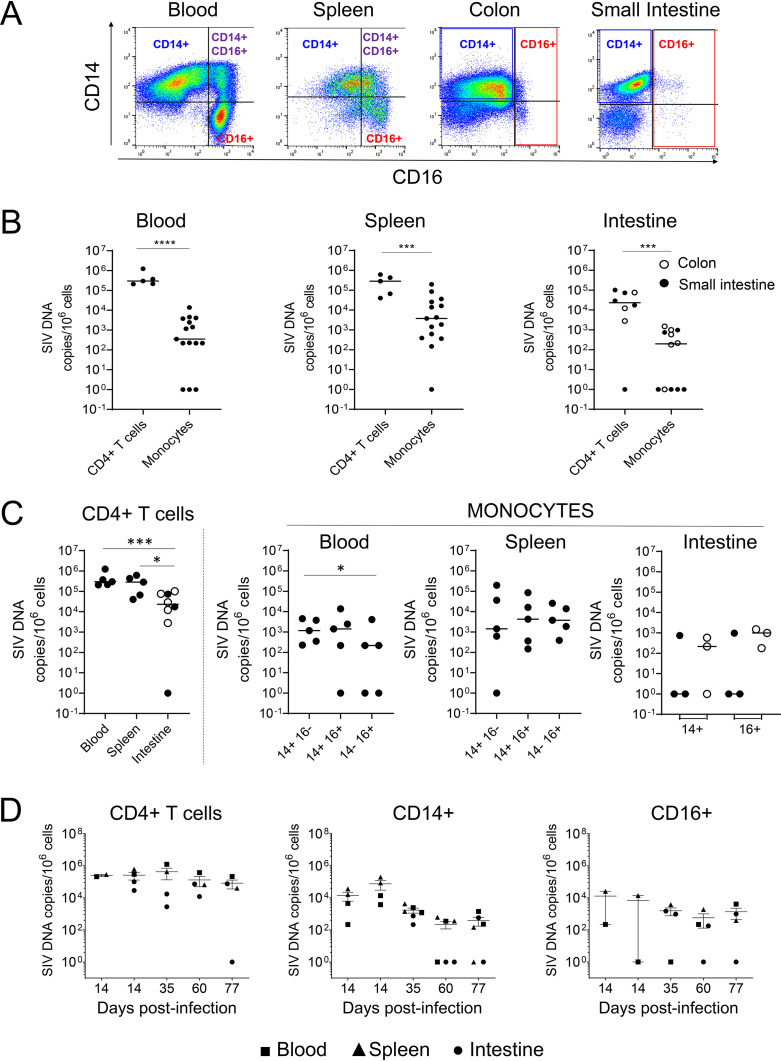

To determine the contributing role of monocyte subsets in early viral seeding, five SIV-infected RMs were sacrificed at days 14, 35, 60, and 77 postinfection (Table 1). Cells were isolated from peripheral blood, spleen, and intestines (including ileum, jejunum, and colon), stained with specific antibodies, and sorted. Cell suspensions of ileum and jejunum were pooled, due to the limited amounts of cells recovered. Monocyte cell subsets included classical (CD14++ CD16−), intermediate (CD14++ CD16+), and nonclassical (CD14+/− CD16+). Due to the low frequency of CD14+ CD16+ cells in the intestines, monocytes were separated into CD14++ and CD16+ populations. To isolate CD14+ monocytes from the intestines, we used a purification method that preserves the expression of CD14 on the cell surface (Fig. 2A) and differs from that of previous reports, where neutral protease digestion was used to isolate cells from intestinal tissues (52, 53).

FIG 2.

Frequencies of cell-associated SIV DNA in ART-naive SIV-infected RMs. (A) Myeloid cell sorting. Representative dot plots depicting the expression of CD14 and CD16 from cells derived from blood, spleen, colon, and small intestine. Gated cells are CD3− CD20− cells, which are then separated into HLA-DR+ cells and CD11b+ cells, leading to three different monocyte cell subsets. Thus, cells were identified as CD14+ CD16−, CD14+ CD16+, and CD14− CD16+. (B to D) Frequencies of SIV DNA in sorted CD4+ T cells and monocyte cell subsets (CD14+, CD14+ CD16+, and CD16+) from blood and spleen. For intestines (small intestine, including jejunum/ileum, closed symbols; colon, open symbols), only two monocyte populations, CD14+ and CD16+, were sorted from SIV-infected RMs. Each symbol represents the value for one individual. Due to the limited amounts of cells, some RMs were not tested for all conditions. Results are expressed as copies per 106 cells. The Mann-Whitney test was performed. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001.

In quiescent cells, HIV initiates reverse transcription but remains mostly linear and unintegrated, particularly in myeloid cells, in which the nonintegrated DNA form persists for at least 1 month (54, 55). Therefore, total viral DNA was assessed in monocytes in comparison to CD4+ T cells. Viral DNA levels were 3.5 × 102 copies/106 monocytes in the blood and 3.7 × 103 copies/106 monocytes in the spleen (Fig. 2B), lower than DNA levels in CD4+ T cells from the same organs (blood, 2.9 × 105 copies/106 cells, and spleen, 2.8 × 105 copies/106 cells) (Fig. 2B). Although we did not notice a significant difference between the frequencies of viral DNA in CD14− CD16+ versus CD14+ CD16− monocytes, in two individuals, we observed that the CD14− CD16+ population was negative for viral DNA in the blood but positive in the spleen (Fig. 2C). Due to limited amounts of cells being isolated from the intestine, cells from only 3 individuals out of 5 were successfully sorted. The low level of viral DNA of CD4 T cells in the intestine compared to the blood (Fig. 2B and C) could be consistent with the rapid depletion of memory cells in the intestine (56), arguing that CD4 T cells in the effector sites (lamina propria) do not constitute the main source of SIV (57) compared to the inductive sites, such as mesenteric lymph nodes (LNs) (31, 58). A lower frequency of infected cells in the intestine was reported in SIV-infected RMs that were progressing faster compared to the frequency in long-term nonprogressors (59). The amount of viral DNA in the intestines reached 2.1 × 102 copies/106 monocytes (Fig. 2B), a value that is 100-fold lower than in CD4+ T cells (2.3 × 104 copies/106 cells). Both CD14+ and CD16+ cell subsets in the colon were positive for viral DNA, whereas only one individual had detectable SIV DNA in the small intestine (Fig. 2C). Interestingly, the viral DNA amounts observed in colic CD16+ cells were similar to those in CD16+ cells isolated from the blood (Fig. 2C). Although this was not a longitudinal analysis, we plotted the extent of infection according to the date of sacrifice (Fig. 2D). The frequencies of viral DNA in CD4+ T cells versus monocytes in RMs sacrificed at day 14, corresponding to the peak of VL, were similar, consistent with a previous report (21). Thereafter, we observed a contraction phase in the extent of cell-associated viral DNA in monocytes compared to the extent in CD4+ T cells.

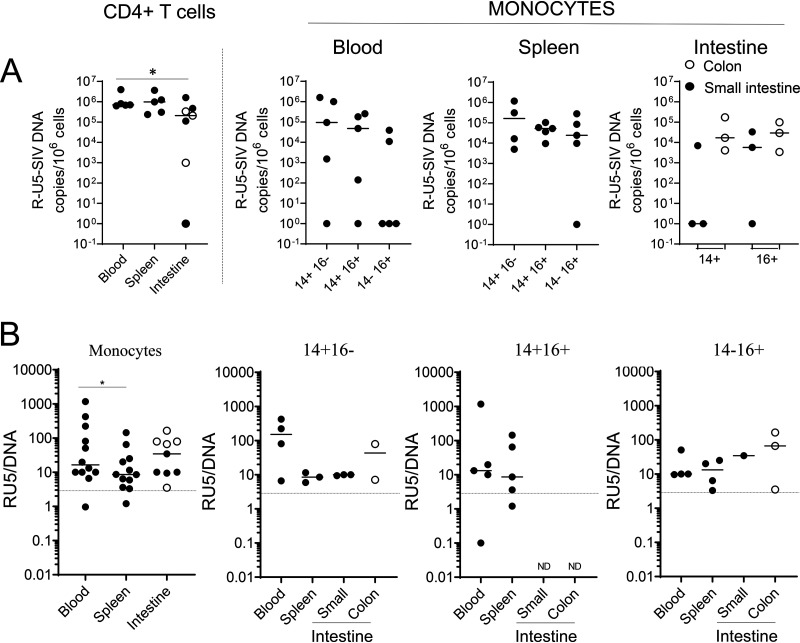

Furthermore, we quantified the levels of R-U5 transcripts, which may be indicative of recent infection (Fig. 3A). Indeed, after HIV entry into cells, the DNA minus strand is copied from the initial R-U5 sequence of the viral RNA genome (early reverse transcripts). Because these primers can also detect viral DNA due to the 2 long terminal repeats (LTRs), a ratio higher than 3 can be considered significant in comparing early reverse transcripts and viral DNA. We found that monocytes of all subsets were recently infected in the blood, spleen, small intestine, and colon, with the overall highest ratio in the blood (Fig. 3B), suggesting that these circulating cells may have been infected in the tissues.

FIG 3.

Frequencies of cell-associated SIV R-U5 in ART-naive SIV-infected RMs. (A) Frequencies of SIV R-U5 in CD4+ T cells and monocyte cell subsets (CD14+, CD14+ CD16+, and CD16+) sorted as described in the legend to Fig. 2. Each symbol represents the value for one individual. Results are expressed as copies per 106 cells. (B) Ratios of SIV R-U5 against viral DNA. Ratios in blood, spleen, and intestines (small intestine, closed symbol; colon, open symbol) and the different monocytic cell subsets are shown. A ratio higher than 3, represented by a dashed line, is considered significant. The Mann-Whitney test was performed. *, P < 0.05; ND, not done due to small amounts of cells.

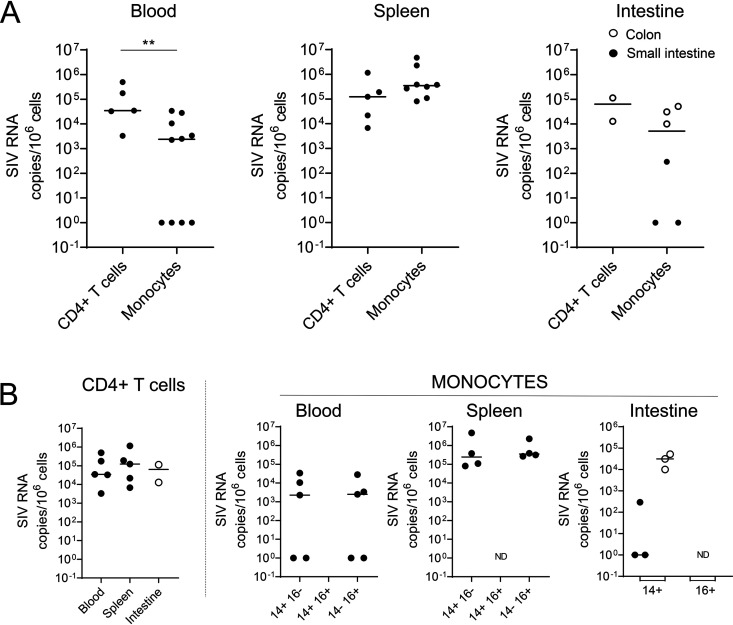

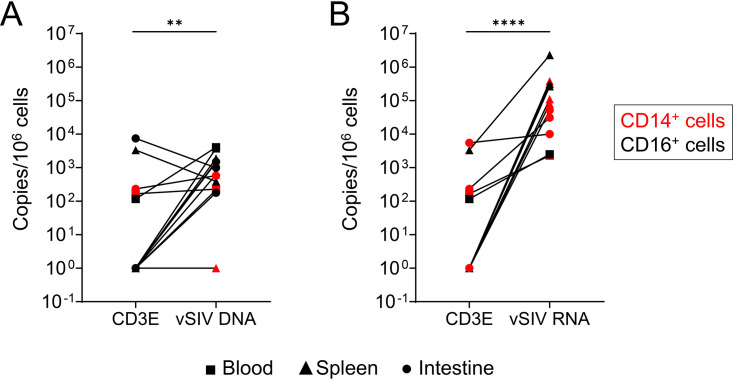

Because we privileged viral DNA quantification and due to the small amounts of certain monocyte subsets, we were unable to perform all SIV RNA quantifications (Fig. 4). By comparing the levels of viral RNA in CD4+ T cells and monocytes, it is of interest that our results demonstrated that the spleen is the main organ in which the levels of viral replication are higher in monocytes than in CD4+ T cells (Fig. 4A). Nevertheless, our results highlighted that both CD14+ CD16− and CD14− CD16+ monocyte subsets in the spleen express viral RNA, reaching 2.4 × 105 copies per 106 cells and 3.5 × 105 copies per 106 cells, respectively (Fig. 4B). Similarly, viral RNA was detected in the colon (CD14+cells, 3.1 × 104 copies per 106 cells). In the blood, the frequencies of viral RNA were lower than in the spleen (less than 1 × 104 copies per 106 cells) (Fig. 4A and B). CD4+ T cells isolated from the different tissues also harbored viral RNA, and the amounts of cell-associated viral RNA were similar in the blood and spleen, as well as in the colon, although only two individuals were tested (RMs 9082012 and 9051222) (Fig. 4B). Because monocytes/macrophages can phagocytose dying infected cells (60, 61), we measured the frequencies of CD3E gene transcripts in sorted monocyte subsets. Our results indicated that the frequencies of both viral DNA and RNA are 10- to 103-fold higher than the frequency of CD3E, supporting the absence of CD4+ T cell contamination (Fig. 5).

FIG 4.

Frequencies of cell-associated SIV RNA in ART-naive SIV-infected RMs. (A and B) Frequencies of SIV RNA in CD4+ T cells and monocyte cell subsets (CD14+, CD14+ CD16+, and CD16+) sorted as described in the legend to Fig. 2. Each symbol represents the value for one individual. Results are expressed as copies per 106 cells. The Mann-Whitney test was performed. **, P < 0.01; ND, not done due to small amounts of cells.

FIG 5.

Levels of CD3E in sorted monocytic cell subsets. The expression of CD3E mRNA was quantified by qRT-PCR in sorted monocytic cell subsets (including CD14+ CD16−, CD14+ CD16+, and CD14− CD16+) from blood and spleen. The frequencies were compared with the viral DNA (A) and viral RNA (B) frequencies. Results are expressed as copies per 106 cells. Paired t test was performed. **, P < 0.01; ****, P < 0.0001.

Altogether, these observations demonstrated early seeding of SIV in which splenic monocytes may contribute to the establishment of reservoirs and viral dissemination in tissues.

Early ART prevents the establishment of monocyte VRs and inflammation.

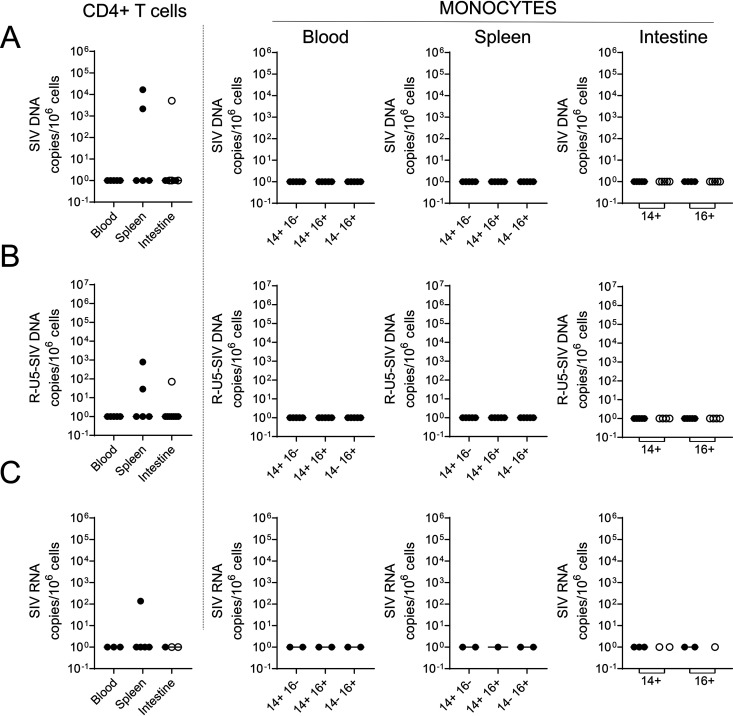

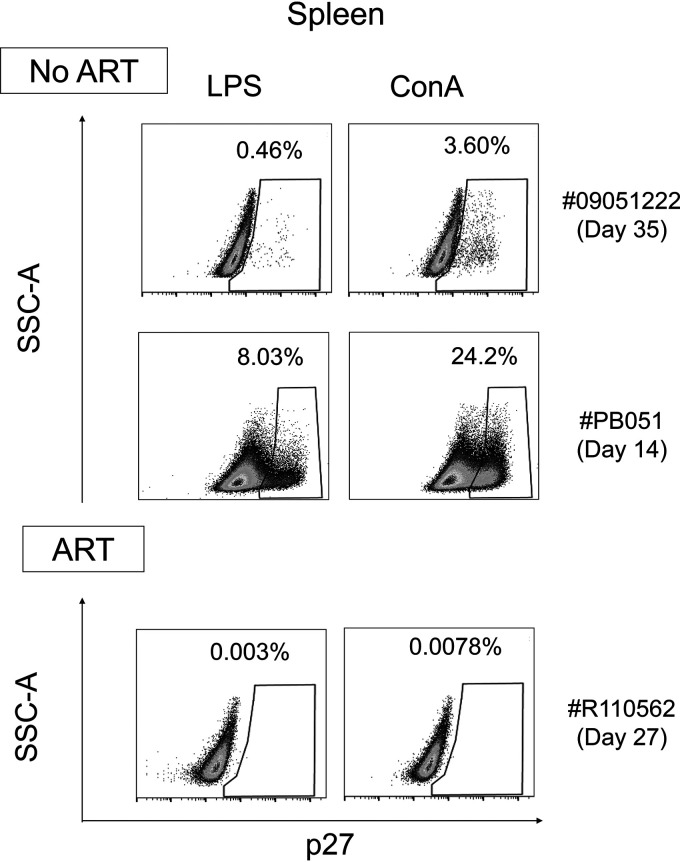

Next, we determined the impact of early ART administration on the viral infection of monocytes (Fig. 1). Our results demonstrated the absence of viral DNA detection in the spleen, blood, and intestines, including the small intestine and the colon (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, and consistent with previous reports (47–49), early ART drastically reduced viral infection of CD4+ T cells in the peripheral blood (Fig. 6A). In two individuals (RMs 111466R and R110360), viral DNA was detected in CD4+ T cells isolated from the spleen, and in only one RM, in the small intestine (RM R110806). In ART-treated RMs, no viral DNA, R-U5, or viral RNA was detected in monocytes from the blood, spleen, and intestines (Fig. 6B and C). To confirm the absence of fully infectious SIV under ART, cells from the spleen of an ART-treated RM (RM R110562, day 27 postinfection) were activated with either LPS, a Toll-like receptor agonist, or ConA, a T cell stimulus. ART-naive SIV-infected RMs (RM 9051222, day 35 postinfection, and RM PB051, day 14 postinfection) were used as controls. Viral outgrowth was performed by adding CEMx174 cells after 1 day of activation, and detection of p27 antigen was assessed by flow cytometry at day 14. Our results indicated the presence of productive infected cells from the spleen of ART-naive SIV-infected RMs (Fig. 7) stimulated with either LPS or ConA, which is consistent with the observation of viral DNA and RNA. RMs with lower viral loads (Table 1) displayed lower levels of viral outgrowth (RM 9051222, LPS, 0.46%, and ConA, 3.60%) compared to RM with higher VLs (RM PB051, LPS, 8.03%, and ConA, 24.2%). On the contrary, no viral outgrowth was observed for ART-treated RMs, which is consistent with the absence of viral DNA detected in the spleen (Fig. 4), as well the absence of viremia (Table 1).

FIG 6.

Frequencies of cell-associated SIV DNA and RNA in ART-treated RMs. Frequencies of SIV DNA (A), SIV R-U5 (B), and SIV RNA (C) were quantified by qRT-PCR in CD4+ T cells and monocytic cell subsets sorted as described in the legend to Fig. 2. Each symbol represents the value for one individual. Results are expressed as copies per 106 cells.

FIG 7.

Replication-competent SIV. SIV p27 levels in cocultures of splenocytes (1.5 × 106 cells) stimulated with either LPS (10 ng/ml) or ConA (2 μg/ml) with CEMx174 cells after 2 weeks. At day 1, cells were cocultured with the cell line CEMx174 (104 cells). Splenocytes are derived from two ART-naive RMs (RM 09051222, day 35 postinfection, and RM PB051, day 14 postinfection) and one ART-treated RM (RM R110562, day 27 postinfection). Viral p27 antigen was quantified by flow cytometry. SSC, side scatter.

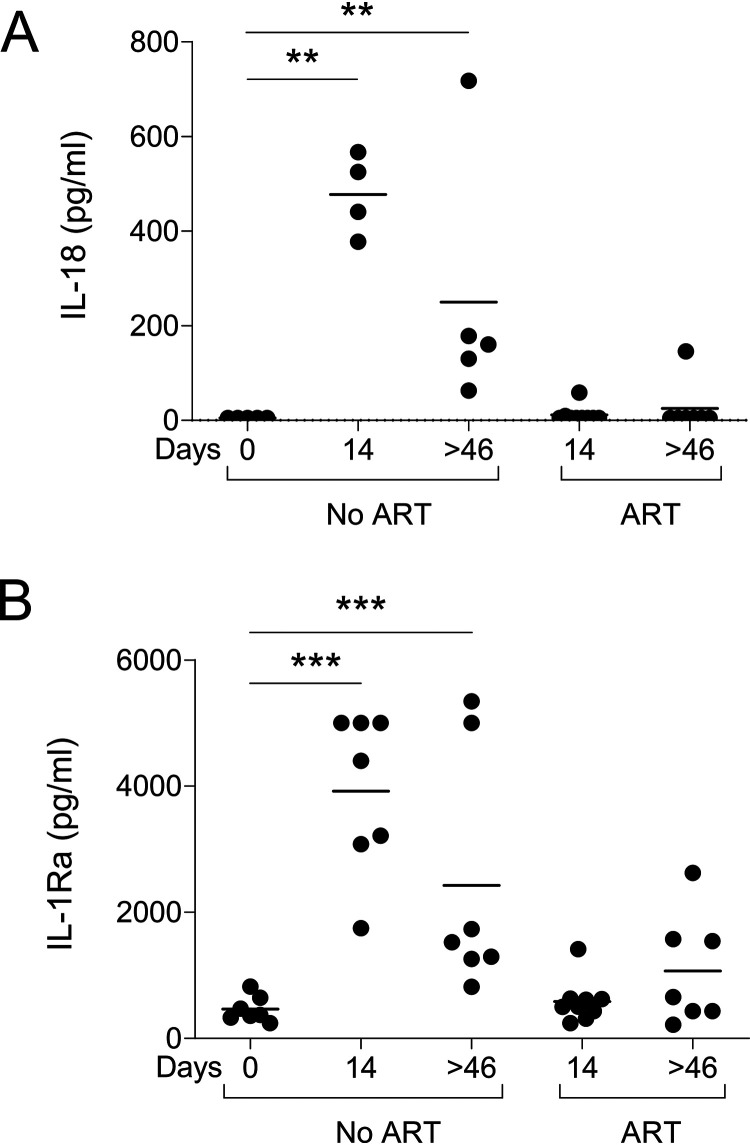

During the acute phase, a cytokine storm, arising in response to HIV/SIV infection, was reported (62–64). We have previously reported higher levels of IL-18 early after SIV infection (65, 66). Here, IL-18 peaked at day 14 and thereafter plateaued at lower levels that remained higher than those observed before infection (Fig. 8A). Of importance, early ART completely blunted IL-18 expression, which remained at a low level under ART, similar to the level observed before infection (Fig. 8A). IL-1 receptor antagonist protein (IRAP, IL-1Ra) has been proposed as an “innate immune set point” that can be used in clinical practice as an early surrogate marker for disease progression and is expressed in lymphoid tissues (67–69). However, little is known about IL-1Ra expression during the acute phase of infection. Herein, we demonstrated higher levels of IL-1Ra early after infection that persisted during the chronic phase, similarly to IL-18 (Fig. 8B). Early ART reduced the expression of IL-1Ra at day 14, but we observed higher levels of IL-1Ra in 3 ART-treated RMs at day 46 (Fig. 8B).

FIG 8.

Levels of IL-18 and IL-1Ra in SIV-infected RMs. (A and B) IL-18 (A) and IL-1Ra (B) were quantified by ELISA in uninfected RMs (day 0), ART-naive RMs (at days 14 and >46), and ART-treated RMs (at days 14 and >46). Results are expressed as picograms per milliliter of serum. Each symbol represents the value for one individual. In ART-naive RMs, we included additional samples, given that RMs were sacrificed earlier. The Mann-Whitney test was performed. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

Altogether, these results demonstrated that ART administered early after infection was efficient in preventing the establishment of monocyte VRs and inflammation.

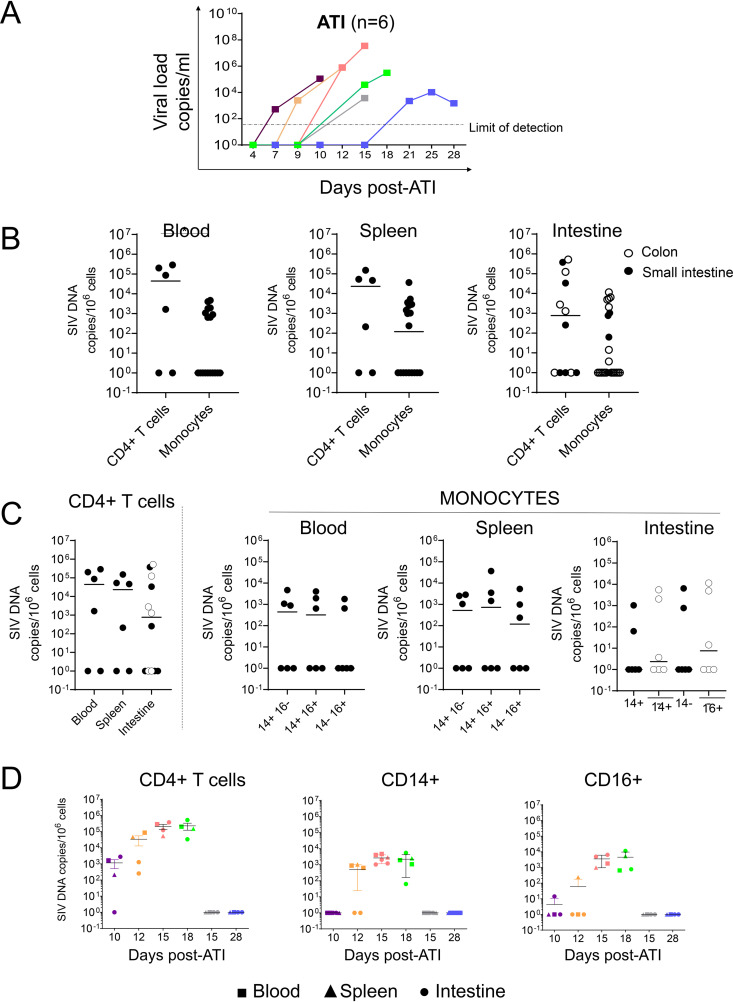

Monocytes are infected early after ATI.

After 8 weeks of daily doses of ART, VL was undetectable in all RMs at this time point. Therefore, we decided to interrupt ART administration and to analyze the dynamic of viral rebound, as well as the infection of monocytes. We observed viral rebounds at days 7 (RM R110482), 9 (RM 121888R), 11 (RM 131134R), 15 (RMs R110804 and 111430R), and 21 (RM 131878R) (Fig. 9A). Thus, our results are consistent with previous reports in which viral rebound is described to occur 2 to 3 weeks after ATI (47–49). To quantify monocyte infection in tissues, RMs were sacrificed 2 to 3 days after viremia detection. The levels of VL at sacrifice were between 103 to 107 copies/ml (Fig. 9A, Table 1). After ATI, we detected viral DNA in monocytes of three RMs out of six. For comparison, CD4+ T cells were positive for viral DNA in four RMs out of six (Fig. 9B), with levels of viral DNA 100- to 1,000-fold higher than those observed in monocytic cell subsets (Fig. 9B). Classical (CD14+ CD16−), intermediate (CD14+ CD16+), and nonclassical (CD14− CD16+) monocytes all expressed viral DNA, and the frequencies were similar in the blood and spleen, reaching 103 to 104 copies/106 cells (Fig. 9C). In the intestines, viral DNA was also detected both in the colon and small intestine, from both CD14+ and CD16+ cells (Fig. 9B and C). We then plotted the frequencies of cell-associated SIV DNA in relation to the date of sacrifice (Fig. 9D). In RMs sacrificed early after ATI (day 10), viral DNA was mostly observed in CD4+ T cells (Fig. 9D). Viral DNA detection in monocyte subsets (CD14+ versus CD16+) was either negative (day 10) or yielded lower levels than were observed in CD4+ T cells (Fig. 9D). Interestingly, in the two animals in which the VL was low (RM R110804 and RM 131878R, sacrificed at days 15 and 28, respectively), we did not detect viral DNA in monocytes, which may be indicative of the presence of additional VRs contributing to viral rebound (Fig. 9D).

FIG 9.

Viral loads and frequencies of cell-associated SIV DNA after ART interruption (ATI). (A) Viral loads after ATI were quantified by qRT-PCR. Each color represents the data for one individual. (B to D) Frequencies of SIV DNA were quantified by qRT-PCR in CD4 cells and monocytes sorted as described in the legend to Fig. 2. Each symbol represents the value for one individual. Results are expressed as copies per 106 cells. A Mann-Whitney test was performed. *, P < 0.05.

Extending the analysis to viral RNA, we observed the presence of viral RNA in monocytes isolated from the spleen, blood, and intestines (Fig. 10A). Viral RNA was also detected in CD4+ T cells from the blood, spleen, and intestines (Fig. 10A), and interestingly, the levels of viral RNA in CD4+ T cells and monocytes were similar in the spleen. Thus, by comparing the frequencies of viral DNA versus RNA in splenic monocytes and CD4+ T cells, we observed that, in monocytes, viral RNA copy numbers were 100-fold higher than viral DNA copy numbers. In contrast, CD4+ T cells carried 10 times more viral DNA than RNA. Thus, and similarly to what was observed in untreated RMs, splenic monocytes may also represent a major site for productively SIV-infected cells following treatment interruption. Interestingly, both CD14+ and CD16+ subsets expressed viral RNA in blood and spleen, and no major difference was observed between the two populations (Fig. 10B). In the intestines, only CD14+ cells were analyzed, due to the limited numbers of other cells recovered. Furthermore, in the two RMs sacrificed at days 15 and 28 (RMs R110804 and 131878R), for which we did not detect viral DNA (Fig. 9D) either in CD4+ T cells or in monocytes, we detected viral RNA that could be indicative of the presence of virions in these cells (Fig. 10C).

FIG 10.

Frequencies of cell-associated SIV RNA after ART interruption (ATI). Frequencies of cell-associated SIV RNA in individual RMs sacrificed at each time point as in Fig. 9. Each symbol represents the value for one individual. Results are expressed as copies per 106 cells. ND, not done due to small amounts of cells. The Mann-Whitney test was performed, and no statistically significant difference was observed.

Thus, we demonstrated that monocytes are early targets for SIV infection once ART is interrupted.

DISCUSSION

There is considerable evidence that monocytes replenish intestinal macrophages during inflammation and microbial clearance and after tissue injury (5, 6, 70–75). Our observation that early ART annihilates the infection of monocytes is of crucial importance. By blocking not only the infection of blood monocytes, which are derived from bone marrow, but also of splenic monocytes, which are considered to be a major cellular reservoir mobilized early after trauma, early ART can limit viral dissemination and the recruitment of infected monocytes that normally maintain tissue macrophage homeostasis. ART is also essential to reduce innate immune activation and inflammation, as shown by the absence of IL-18 and IL-1Ra in treated RMs. Indeed, inflamed tissues favor the recruitment of monocytes. We also demonstrated that ATI was associated with the resurgence of SIV, leading to a rebound in viremia that targeted not only CD4 T cells but also monocytes in the different compartments analyzed. Thus, in less than 2 weeks after ATI, monocytes became infected and capable of expressing viral RNA, particularly in the spleen.

In untreated HIV-infected individuals, as well as SIV-infected RMs, accumulation of myeloid cells is observed in the intestines and associated with increased inflammation and turnover correlating with the progression to AIDS (37, 38, 76–79). We observed that the amount of viral DNA in splenic monocytes was 100-fold higher than the amounts in the blood and colon. It has been assumed that the majority of macrophages containing viral DNA are derived from the phagocytosis of infected, dying cells (60, 61), and therefore, they may acquire HIV/SIV indirectly from CD4+ T cells in the surrounding tissue. By comparing the frequency of viral DNA in infected CD4+ T cells to its frequencies in monocyte subsets, we found this ratio to be around 10 to 100, which would correspond to a situation where 1% to 10% of monocytes may have phagocytosed infected CD4+ T cells. By measuring CD3E mRNA expression in purified monocyte cell subsets, the frequency of measured CD3E was found to be too low (1/5,000) to explain the high frequency of viral DNA observed in monocytes. The “eat me” signals included CD36/Croquemort, milk fat globule-epidermal growth factor 8 (MFG-E8), and Tim4 as a phosphatidylserine receptor (80–83). However, the observation that classical (CD14+) and nonclassical (CD16+) monocytes displayed similar levels of viral DNA, whereas only the former are prone to phagocytosis related to the expression of “eat me” molecules, supports alternative mechanisms of infection (84, 85). Therefore, our results may provide important insight about viral infection of monocytes and suggest that various monocyte cell subsets are productively infected in various anatomical compartments. A possible caveat in comparing the SIVmac251-based studies here to HIV is the potential difference in coreceptor usage. Whereas CCR5 and CXCR4 are used by HIV for entry, only the first is used for myeloid cell infection. In this context, it is worth mentioning that SIVmac251 uses CCR5 and not CXCR4 for entry. It is assumed that monocytes from the intestines are resistant to SIV/HIV due to low levels of CCR5 expression (52, 53, 86). However, we detected viral DNA and RNA in monocytes isolated from either the spleen or the intestines, including the large and small intestines. Furthermore, a role has also been proposed for postentry blocks (87) linked to the pool of modulated deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP), which is modulated by SAMHD1 (88, 89). Whereas HIV-1 expresses the Vpr protein, SIVmac expresses the Vpx protein, which has been shown to facilitate viral infectivity by counteracting SAMHD1 activity in myeloid cells in vitro (88, 89). Interestingly, Calantone et al. (61), using SIVs that do or do not express Vpx, found no measurable effect on the presence of viral DNA within myeloid cells compared to its presence in CD4 T cells, although the levels of viral DNA from RMs infected by Vpx-defective SIVs were lower in both subsets.

Herein, we also demonstrated our ability to isolate infected CD14+ cells from the small intestine and colon. Contrary to previous reports using neutral protease digestion to isolate monocytes derived from the lamina propria, our protocol preserved the expression of CD14. The CD14 molecule is highly sensitive to protease and is shed after immune activation or apoptosis (90–92). Other molecules, such as NKT cell markers (65), are also susceptible to protease digestion, rendering their identification by flow cytometry difficult following classical cell isolation procedures. Thus, our results are consistent with other reports describing the presence of productively infected myeloid cells in vivo, both in the small intestine and colon (31, 93–95). However, the spleen clearly represents a major organ in SIV pathogenesis, where frequencies of infected cell subsets are higher than in the intestines and similar to those observed in CD4+ T cells. Furthermore, we demonstrated that infected monocytes from the spleen can produce fully infectious viruses after Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) stimulation. Thus, the spleen represents a privileged site of infected monocytes. This could be critical to pathogenesis, since monocytes from the spleen can be mobilized early and deployed after trauma (7). We found that CD14+ and CD16+ cell subsets both contain viral DNA, supporting the idea that both populations may contribute to viral dissemination and production. Inflammatory monocytes have been shown to infiltrate the brain, which is itself considered to be an important VR, a process that is enhanced by the depletion of CD4 T cells (33). Therefore, persistence of infected monocytes in the spleen could contribute to viral dissemination through the migration of infected cells to various sites of inflammation, fueling the fire from a distance. Our results demonstrated that early ART prevented viral infection of monocytes in the different compartments analyzed. Recent reports have indicated that ART administration after the peak of infection (days 12 to 14 postinfection) did not completely abolish viral infection of CD11b+ cells in the spleen and blood of SIV-infected pigtail and juvenile monkeys (96). This difference could be due either to differences in the timing of ART administration or to the fact that the latter monkeys are more sensitive than adult Chinese RMs. Our results are consistent with a recent report indicating that HIV-1 is rarely detected in blood monocytes and colon of ART-treated HIV-infected individuals (43). Therefore, administering ART as soon as possible after infection or treating individuals for a long time may interrupt the vicious cycle of viral dissemination, by impairing viral infection of monocytes.

Chronic inflammation is associated with a proportional increase of non-AIDS-related events, such as cardiovascular, liver, and renal diseases (97–100). IL-1Ra has been proposed to be an innate immune set point, expressed in lymphoid tissues (67–69), and was recently demonstrated as a predictive marker of myocardial infarction in HIV-infected individuals (101). Because in vitro monocytes infected with HIV induce IL-1Ra secretion at a mean level 1,000-fold higher than that of IL-1α/β (102), the detection of IL-1Ra could be a marker of viral persistence under ART. Herein, we demonstrated that early ART, by impairing monocyte infection, also drastically reduced IL-1Ra production, which remained elevated in 3 ART-treated RMs. Initially described in mice preconditioned with Propionibacterium acnes (103), IL-18 (104), which is a substrate of caspase and a marker of inflammasome activation, has also been associated with faster disease progression and clinical ART failure (105–107). IL-18 augments the Fas ligand (108), which is expressed in HIV-infected individuals (109) and SIV-infected RMs (21). We have previously demonstrated that the administration of caspase inhibitors prevented the release of IL-18 and progression to AIDS in vivo (66). Therefore, early ART, by preventing the infection of monocytes, also prevents IL-18 release, which itself is detrimental to HIV-infected individuals (110–113).

Consistent with previous reports, and despite the administration of early ART, which controls viremia and the infection of monocytes, a viral rebound was observed occurring 2 to 3 weeks after ATI (47–49). We demonstrated that monocytes could be infected and express viral RNA following ATI, a process in which the spleen, among the tissues analyzed, represented one of the main anatomical sites. Thus, monocytes, which have a short half-life compared to that of resident macrophages, cannot be a VR under ART but can instead be an early viral target once therapy is interrupted. During the last decade, long-lived myeloid cells, derived from the yolk sac, have been found to be able to self-renew and to be essential for tissue homeostasis, including in the brain, liver, or lung (9, 114). Thus, it has been proposed that viruses persist in the brain, lung, and liver and in adipocytes in SIV-infected RMs treated at the chronic phase (50, 115–117). Although it remains to be explored whether these long-lived myeloid cells can be early targets and represent potential VRs despite early ART, we recently demonstrated that T follicular helper cells can also be potent VRs in visceral tissues (58) and could contribute to viral rebound after ATI.

In conclusion, our results revealed that the administration of early ART can reduce the infection of monocytes, not only in the blood but also in the spleen and intestine, and prevent inflammation, which remains a major health problem for HIV-infected individuals under ART. Whereas monocytes may not be major VRs under ART, they can be infected again rapidly after ATI. Therefore, it will be of crucial importance for a cure to achieve a full prevention of monocyte infection, particularly in lymphoid tissues.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals, viral inoculation, and sample collection.

Sixteen rhesus macaques (RMs) seronegative for SIV, simian T leukemia virus type 1 (STLV-1), simian type D retrovirus 1 (SRV-1), and herpes B viruses were infected intravenously with SIVmac251 (20 AID50). At day 4 postinfection, 11 RMs were treated with tenofovir (TFV, 20 mg/kg; Gilead) and emtricitabine (FTC, 40 mg/kg; Gilead) subcutaneously and raltegravir (RGV, 20 mg/kg; Merck) or dolutegravir (DTG, 5 mg/kg; ViiV) and ritonavir (RTV, 20 mg/kg; Abbvie) by the oral route. RMs were sacrificed at different time points postinfection during natural infection (no ART, n = 5), under ART (ART, n = 5), and after ART interruption (ATI, n = 6) as shown in Fig. 1A and Table 1. Blood, spleen, and intestines (ileum, jejunum, and colon) were recovered immediately after euthanasia. Cells were isolated after mechanical processing (118). Tissues were not digested with collagenase or other proteases to limit negative effects on the expression of cell surface markers, particularly for CD14 shedding.

Ethics statement.

RMs were housed at University Laval in accordance with the rules and regulations of the Canadian Council on Animal Care (http://www.ccac.ca). The protocol was approved by the Laval University Animal Protection Committee (project number 106004). Animals were fed standard monkey chow diet, supplemented daily with fruit and vegetables and water ad libitum. Social enrichment was delivered and overseen by a veterinary staff, and overall animal health was monitored daily. Animals were evaluated clinically and were humanely euthanized using an overdose of barbiturates according to the guidelines of the Veterinary Medical Association.

Cell sorting.

Cells derived from blood, spleen, or intestines (108 cells) were sorted using a BD Influx cell sorter (BD Biosciences) with specific antibodies, i.e., anti-CD3, anti-CD4, anti-CD20, anti-HLA-DR, anti-CD14, and anti-CD16 monoclonal antibodies (MAbs), purchased from either BD Biosciences or Biolegend. Briefly, non-CD3 and non-CD20 cells were separated into HLA-DR+ and HLA-DR− cells. Three different monocyte subsets were sorted from CD11b+ HLA-DR+ cells, i.e., CD14+ CD16−, CD14+ CD16+, and CD14− CD16+. Due to the low frequency of CD14+ CD16+ cells in the intestines, monocytes were separated into CD14+ and CD16+ populations (Fig. 2A). CD4+ T cells were sorted from the CD3+ CD20− population. Samples were preserved at −80°C until used.

Viral RNA quantification.

Viral loads in the sera of SIV-infected RMs were quantified by reverse transcriptase quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) using a PureLink viral RNA/DNA kit (Invitrogen). The PCR mixture was composed of 4× TaqMan fast virus 1-step master mix (Applied Biosystems), 750 nM primers, and 200 nM probe. Primers and probe included the following: SIVmac-F, GCA GAG GAG GAA ATT ACC CAG TAC; SIVmac-R, CAA TTT TA CCC AGG CAT TTA ATG TT; and SIVmac-Probe, 6FAM TGT CCA CCT GCC ATT AAG CCC GA TAMRA (6FAM, 6-carboxyfluorescein; TAMRA, 6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine). A plasmid bearing the gag gene of SIVmac251 was used as a standard. Serial 10-fold dilutions of SIVmac251 plasmid were performed to generate a standard curve, starting at 109 copies/μl of SIV. Amplifications were carried out with a QuantStudio 6 flex real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems), using the following parameters: 50°C for 5 min, 95°C for 20 s, and 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. Samples were run in duplicate, and results are expressed as SIV RNA copies/ml (62).

Cell-associated SIV RNA and DNA quantification.

(i) Cell-associated viral RNA. Quantification of cell-associated viral RNA was performed from 105 sorted cells. Viral RNA was extracted with a TRIzol procedure according to the manufacturer’s instructions and resuspended in 50 μl of RNase-free water (Invitrogen). DNA traces were eliminated from RNA samples using a Turbo DNA-free kit (Invitrogen). For RNA quantification, 5 μl of RNA was amplified by RT-qPCR. Eukaryotic 18S rRNA endogenous control mix (Applied Biosystems) was used to estimate cell numbers in each sample. Samples were run in duplicate, and the results are expressed as numbers of SIV RNA copies per 106 cells.

(ii) Cell-associated viral DNA. Quantification of cell-associated viral DNA was performed from the same sorted populations (105 to 106 cells). DNA was purified using a genomic DNA tissue kit (Macherey-Nagel). DNA was eluted with 50 μl of buffer elution, and 10 μl of DNA eluate was amplified by nested PCR with SIV251-specific primers surrounding the nef coding region to increase the sensitivity of viral detection (118). Thus, a first round of PCR was performed using 50 nM preco (CAG AGG CTC TCT GCG ACC CTA C) and K3 (AC TGA ATA CAG AGC GAA ATG C) primers, 10× PCR buffer, 2 mM MgCl2, 1.25 U of AmpliTaq (Applied Biosystems), and 0.8 mM dNTPs (Invitrogen) in a Biometra thermocycler using the following parameters: 95°C for 1 min 45 s, 45 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min 10 s, and a final step of 72°C for 6 min. Five microliters of the PCR product was reamplified using 250 nM SIV DNA primers and probe (SIV DNA-F, TCC CTA GGA GGA TTA GAC AAG G; SIV DNA-R, CTC TCT TCA GCT GGG TTT CTC; SV DNA probe, 56FAM AGC TCA CTC ZEN TCT TGT GAG GGA CAG A 3IABkFQ) and 2× PrimeTime gene expression master mix (IDT) in a QuantStudio 6 flex real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). PCR amplification parameters were 95°C for 3 min and 45 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. Samples were run in quadruplicate due to the low levels of viral DNA under ART, and the results are expressed as numbers of SIV DNA copies per 106 cells. For DNA quantitation, serial dilutions of a plasmid were performed to generate a standard curve instead of using SIV1C, which contains more than one copy of total viral DNA, leading to a lower estimation of the amount of viral DNA.

(iii) SIV R-U5 DNA quantification. From eluate DNA, 5 μl was amplified in duplicate using 2× QuantiTect SYBR green PCR kit (Qiagen) and 250 nM specific primers in a QuantStudio 6 flex real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) (SIV R-U5-F, AAG CTA GTG TGT GTT CCC ATC T; SIV R-U5-R, CTT CGG TTT CCC AAA GCA GAA). The following parameters were used: 50°C for 2 min, followed by 95°C for 15 min and 40 cycles of 94°C for 15 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 35 s, followed by a dissociation stage. A plasmid containing the SIV R-U5 DNA sequence was used to generate a standard curve. Results are expressed as SIV R-U5 DNA copies/106 cells.

To estimate the cell numbers in each sample and as an internal control, ribosomal 18S DNA was amplified in parallel (ADN18S-F, CCT CCA ATG GAT CCT CGT TA; ADN18S-R, AAA CGG CTA CCA CAT CCA AG), using the same parameters and thermocycling settings as for SIV R-U5 DNA quantification. A standard curve was used to estimate the cell numbers, and the results were expressed as SIV DNA copies per 106 cells.

Viral outgrowth assay.

To evaluate the ability of monocytes to produce fully infectious viruses, splenocytes (1.5 × 106 cells) were activated with a Toll-like receptor agonist, LPS-B5 ultrapure (10 ng/ml; Invivogen) or with concanavalin A (2 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) and IL-2 (10 ng/ml; R&D Systems). At day 1, activated cells were cocultured with the cell line CEMx174 (104 cells). At day 14 of coculture, SIV viral gag antigen was quantified by flow cytometry using a specific anti-p27 antibody kindly provided by the NIH AIDS Reagent Program.

IL-18 and IL-1Ra quantifications.

IL-18 and IL-1Ra were quantified in the sera of RMs using a human IL-18 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (product number 7620; MBL) and a human IL-1ra/IL-1F3 Quantikine ELISA kit (catalog number DRA00B; R&D Systems). The optical density was measured at 450 nm, and the concentrations determined using standard curves. Results are expressed as picograms per ml of sera.

CD3E quantification.

Quantification of the expression of CD3E mRNA in monocytic cells was performed using RNA from eluate. Ten microliters of RNA was retrotranscribed into cDNA using a SuperScript II kit (Invitrogen) with 0.5 mM dNTPs, 0.01 M dithiothreitol (DTT), 200 U SuperScript II reverse transcriptase, 50 ng random primers (Invitrogen), and 40 U RiboLock RNase inhibitor (ThermoFisher). The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 10 min, followed by one cycle of 42°C for 50 min and 70°C for 15 min in a Biometra thermal cycler. cDNA was amplified using 2× QuantiTect SYBR green PCR kit (Qiagen) using specific primers in a QuantStudio 6 flex real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) (CD3E-F, GCT CCC ACT TCT AAA TGA GAA CA; CD3E-R, AAT GAG ATC ACG CAC GTC CT). The following parameters were used: 50°C for 2 min, followed by 95°C for 15 min and 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 35 s, followed by a dissociation stage. A plasmid containing a CD3E sequence was used to generate a standard curve. Results are expressed as CD3E copies/106 cells. The number of cells used for viral RNA quantification was used to estimate the cell number in each sample.

Statistical analysis.

Statistics were performed using GraphPad Prism 8 software. The nonparametric Mann-Whitney test and the paired t test were used for comparison, as indicated in the figure legends. P values of <0.05 indicate a significant difference.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) (grant numbers HBF-123682, HBF-126786, and MOP-133476), the ANRS (France), and the Canadian HIV Cure Enterprise (grant number HIG-133050 from the CIHR partnership with CANFAR and IAS to J.E.). H.R. was supported by a fellowship from Laval University (Pierre-Jacob-Durand Grant and Fonds de Recherche sur le Sida), CHU de Québec (Formation Desjardins pour la Recherche et l’Innovation), and Fonds de Recherche du Québec—Santé (FRQS). J.C. was supported by a fellowship from Laval University (Pierre-Jacob-Durand Grant and Fonds de Recherche sur le Sida). C.B. was supported by ANRS. J.E. also thanks the Canada Research Chair program for financial assistance.

We thank Merck, ViiV, and Gilead for providing antiretroviral drugs to J.E. We also thank Daphnée Veilleux-Lemieux and Anne-Marie Catudal for their help at the nonhuman primate center (Quebec City).

H.R., J.C., G.R., G.A., G.B.-L., C.B., O.Z.-A., and J.E. conducted the experiments. H.R., J.C., T.M., F.M., P.A., and J.E. designed the experiments and wrote the paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Geissmann F, Manz MG, Jung S, Sieweke MH, Merad M, Ley K. 2010. Development of monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. Science 327:656–661. doi: 10.1126/science.1178331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gordon S, Taylor PR. 2005. Monocyte and macrophage heterogeneity. Nat Rev Immunol 5:953–964. doi: 10.1038/nri1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ziegler-Heitbrock L, Ancuta P, Crowe S, Dalod M, Grau V, Hart DN, Leenen PJ, Liu YJ, MacPherson G, Randolph GJ, Scherberich J, Schmitz J, Shortman K, Sozzani S, Strobl H, Zembala M, Austyn JM, Lutz MB. 2010. Nomenclature of monocytes and dendritic cells in blood. Blood 116:e74–e80. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-258558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geissmann F, Jung S, Littman DR. 2003. Blood monocytes consist of two principal subsets with distinct migratory properties. Immunity 19:71–82. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(03)00174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bain CC, Scott CL, Uronen-Hansson H, Gudjonsson S, Jansson O, Grip O, Guilliams M, Malissen B, Agace WW, Mowat AM. 2013. Resident and pro-inflammatory macrophages in the colon represent alternative context-dependent fates of the same Ly6Chi monocyte precursors. Mucosal Immunol 6:498–510. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bain CC, Bravo-Blas A, Scott CL, Perdiguero EG, Geissmann F, Henri S, Malissen B, Osborne LC, Artis D, Mowat AM. 2014. Constant replenishment from circulating monocytes maintains the macrophage pool in the intestine of adult mice. Nat Immunol 15:929–937. doi: 10.1038/ni.2967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swirski FK, Nahrendorf M, Etzrodt M, Wildgruber M, Cortez-Retamozo V, Panizzi P, Figueiredo JL, Kohler RH, Chudnovskiy A, Waterman P, Aikawa E, Mempel TR, Libby P, Weissleder R, Pittet MJ. 2009. Identification of splenic reservoir monocytes and their deployment to inflammatory sites. Science 325:612–616. doi: 10.1126/science.1175202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luster AD, Alon R, von Andrian UH. 2005. Immune cell migration in inflammation: present and future therapeutic targets. Nat Immunol 6:1182–1190. doi: 10.1038/ni1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ginhoux F, Jung S. 2014. Monocytes and macrophages: developmental pathways and tissue homeostasis. Nat Rev Immunol 14:392–404. doi: 10.1038/nri3671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewin SR, Sonza S, Irving LB, McDonald CF, Mills J, Crowe SM. 1996. Surface CD4 is critical to in vitro HIV infection of human alveolar macrophages. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 12:877–883. doi: 10.1089/aid.1996.12.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naif HM, Li S, Alali M, Sloane A, Wu L, Kelly M, Lynch G, Lloyd A, Cunningham AL. 1998. CCR5 expression correlates with susceptibility of maturing monocytes to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Virol 72:830–836. doi: 10.1128/JVI.72.1.830-836.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tuttle DL, Harrison JK, Anders C, Sleasman JW, Goodenow MM. 1998. Expression of CCR5 increases during monocyte differentiation and directly mediates macrophage susceptibility to infection by human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol 72:4962–4969. doi: 10.1128/JVI.72.6.4962-4969.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thieblemont N, Weiss L, Sadeghi HM, Estcourt C, Haeffner-Cavaillon N. 1995. CD14lowCD16high: a cytokine-producing monocyte subset which expands during human immunodeficiency virus infection. Eur J Immunol 25:3418–3424. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830251232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams KC, Corey S, Westmoreland SV, Pauley D, Knight H, deBakker C, Alvarez X, Lackner AA. 2001. Perivascular macrophages are the primary cell type productively infected by simian immunodeficiency virus in the brains of macaques: implications for the neuropathogenesis of AIDS. J Exp Med 193:905–915. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.8.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fischer-Smith T, Croul S, Sverstiuk AE, Capini C, L’Heureux D, Regulier EG, Richardson MW, Amini S, Morgello S, Khalili K, Rappaport J. 2001. CNS invasion by CD14+/CD16+ peripheral blood-derived monocytes in HIV dementia: perivascular accumulation and reservoir of HIV infection. J Neurovirol 7:528–541. doi: 10.1080/135502801753248114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ancuta P, Weiss L, Haeffner-Cavaillon N. 2000. CD14+CD16++ cells derived in vitro from peripheral blood monocytes exhibit phenotypic and functional dendritic cell-like characteristics. Eur J Immunol 30:1872–1883. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Randolph GJ, Sanchez-Schmitz G, Liebman RM, Schakel K. 2002. The CD16(+) (FcgammaRIII(+)) subset of human monocytes preferentially becomes migratory dendritic cells in a model tissue setting. J Exp Med 196:517–527. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ancuta P, Autissier P, Wurcel A, Zaman T, Stone D, Gabuzda D. 2006. CD16+ monocyte-derived macrophages activate resting T cells for HIV infection by producing CCR3 and CCR4 ligands. J Immunol 176:5760–5771. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.10.5760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ho DD, Rota TR, Hirsch MS. 1986. Infection of monocyte/macrophages by human T lymphotropic virus type III. J Clin Invest 77:1712–1715. doi: 10.1172/JCI112491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McElrath MJ, Steinman RM, Cohn ZA. 1991. Latent HIV-1 infection in enriched populations of blood monocytes and T cells from seropositive patients. J Clin Invest 87:27–30. doi: 10.1172/JCI114981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laforge M, Campillo-Gimenez L, Monceaux V, Cumont MC, Hurtrel B, Corbeil J, Zaunders J, Elbim C, Estaquier J. 2011. HIV/SIV infection primes monocytes and dendritic cells for apoptosis. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002087. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu T, Muthui D, Holte S, Nickle D, Feng F, Brodie S, Hwangbo Y, Mullins JI, Corey L. 2002. Evidence for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication in vivo in CD14(+) monocytes and its potential role as a source of virus in patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Virol 76:707–716. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.2.707-716.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim WK, Sun Y, Do H, Autissier P, Halpern EF, Piatak M Jr, Lifson JD, Burdo TH, McGrath MS, Williams K. 2010. Monocyte heterogeneity underlying phenotypic changes in monocytes according to SIV disease stage. J Leukoc Biol 87:557–567. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0209082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patterson BK, Mosiman VL, Cantarero L, Furtado M, Bhattacharya M, Goolsby C. 1998. Detection of HIV-RNA-positive monocytes in peripheral blood of HIV-positive patients by simultaneous flow cytometric analysis of intracellular HIV RNA and cellular immunophenotype. Cytometry 31:265–274. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams K, Westmoreland S, Greco J, Ratai E, Lentz M, Kim WK, Fuller RA, Kim JP, Autissier P, Sehgal PK, Schinazi RF, Bischofberger N, Piatak M, Lifson JD, Masliah E, Gonzalez RG. 2005. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy reveals that activated monocytes contribute to neuronal injury in SIV neuroAIDS. J Clin Invest 115:2534–2545. doi: 10.1172/JCI22953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Folks TM, Justement J, Kinter A, Dinarello CA, Fauci AS. 1987. Cytokine-induced expression of HIV-1 in a chronically infected promonocyte cell line. Science 238:800–802. doi: 10.1126/science.3313729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gartner S, Markovits P, Markovitz DM, Kaplan MH, Gallo RC, Popovic M. 1986. The role of mononuclear phagocytes in HTLV-III/LAV infection. Science 233:215–219. doi: 10.1126/science.3014648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gendelman HE, Orenstein JM, Martin MA, Ferrua C, Mitra R, Phipps T, Wahl LA, Lane HC, Fauci AS, Burke DS. 1988. Efficient isolation and propagation of human immunodeficiency virus on recombinant colony-stimulating factor 1-treated monocytes. J Exp Med 167:1428–1441. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.4.1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perno CF, Yarchoan R, Cooney DA, Hartman NR, Webb DS, Hao Z, Mitsuya H, Johns DG, Broder S. 1989. Replication of human immunodeficiency virus in monocytes. Granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) potentiates viral production yet enhances the antiviral effect mediated by 3′-azido-2′3′-dideoxythymidine (AZT) and other dideoxynucleoside congeners of thymidine. J Exp Med 169:933–951. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.3.933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pomerantz RJ, Feinberg MB, Trono D, Baltimore D. 1990. Lipopolysaccharide is a potent monocyte/macrophage-specific stimulator of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 expression. J Exp Med 172:253–261. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.1.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cumont MC, Monceaux V, Viollet L, Lay S, Parker R, Hurtrel B, Estaquier J. 2007. TGF-beta in intestinal lymphoid organs contributes to the death of armed effector CD8 T cells and is associated with the absence of virus containment in rhesus macaques infected with the simian immunodeficiency virus. Cell Death Differ 14:1747–1758. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Igarashi T, Brown CR, Endo Y, Buckler-White A, Plishka R, Bischofberger N, Hirsch V, Martin MA. 2001. Macrophage are the principal reservoir and sustain high virus loads in rhesus macaques after the depletion of CD4+ T cells by a highly pathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus/HIV type 1 chimera (SHIV): implications for HIV-1 infections of humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98:658–663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.021551798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Micci L, Alvarez X, Iriele RI, Ortiz AM, Ryan ES, McGary CS, Deleage C, McAtee BB, He T, Apetrei C, Easley K, Pahwa S, Collman RG, Derdeyn CA, Davenport MP, Estes JD, Silvestri G, Lackner AA, Paiardini M. 2014. CD4 depletion in SIV-infected macaques results in macrophage and microglia infection with rapid turnover of infected cells. PLoS Pathog 10:e1004467. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bissel SJ, Wang G, Trichel AM, Murphey-Corb M, Wiley CA. 2006. Longitudinal analysis of monocyte/macrophage infection in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected, CD8+ T-cell-depleted macaques that develop lentiviral encephalitis. Am J Pathol 168:1553–1569. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Honeycutt JB, Wahl A, Baker C, Spagnuolo RA, Foster J, Zakharova O, Wietgrefe S, Caro-Vegas C, Madden V, Sharpe G, Haase AT, Eron JJ, Garcia JV. 2016. Macrophages sustain HIV replication in vivo independently of T cells. J Clin Invest 126:1353–1366. doi: 10.1172/JCI84456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sugimoto C, Merino KM, Hasegawa A, Wang X, Alvarez XA, Wakao H, Mori K, Kim WK, Veazey RS, Didier ES, Kuroda MJ. 2017. Critical role for monocytes/macrophages in rapid progression to AIDS in pediatric simian immunodeficiency virus-infected rhesus macaques. J Virol 91:e00379-17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00379-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burdo TH, Soulas C, Orzechowski K, Button J, Krishnan A, Sugimoto C, Alvarez X, Kuroda MJ, Williams KC. 2010. Increased monocyte turnover from bone marrow correlates with severity of SIV encephalitis and CD163 levels in plasma. PLoS Pathog 6:e1000842. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hasegawa A, Liu H, Ling B, Borda JT, Alvarez X, Sugimoto C, Vinet-Oliphant H, Kim WK, Williams KC, Ribeiro RM, Lackner AA, Veazey RS, Kuroda MJ. 2009. The level of monocyte turnover predicts disease progression in the macaque model of AIDS. Blood 114:2917–2925. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-204263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Furtado MR, Callaway DS, Phair JP, Kunstman KJ, Stanton JL, Macken CA, Perelson AS, Wolinsky SM. 1999. Persistence of HIV-1 transcription in peripheral-blood mononuclear cells in patients receiving potent antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med 340:1614–1622. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199905273402102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crowe SM, Sonza S. 2000. HIV-1 can be recovered from a variety of cells including peripheral blood monocytes of patients receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy: a further obstacle to eradication. J Leukoc Biol 68:345–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lambotte O, Taoufik Y, de Goer MG, Wallon C, Goujard C, Delfraissy JF. 2000. Detection of infectious HIV in circulating monocytes from patients on prolonged highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 23:114–119. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200002010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ellery PJ, Tippett E, Chiu YL, Paukovics G, Cameron PU, Solomon A, Lewin SR, Gorry PR, Jaworowski A, Greene WC, Sonza S, Crowe SM. 2007. The CD16+ monocyte subset is more permissive to infection and preferentially harbors HIV-1 in vivo. J Immunol 178:6581–6589. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.10.6581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cattin A, Wiche Salinas TR, Gosselin A, Planas D, Shacklett B, Cohen EA, Ghali MP, Routy JP, Ancuta P. 2019. HIV-1 is rarely detected in blood and colon myeloid cells during viral-suppressive antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 33:1293–1306. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deeks SG, Lewin SR, Havlir DV. 2013. The end of AIDS: HIV infection as a chronic disease. Lancet 382:1525–1533. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61809-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sereti I, Krebs SJ, Phanuphak N, Fletcher JL, Slike B, Pinyakorn S, O’Connell RJ, Rupert A, Chomont N, Valcour V, Kim JH, Robb ML, Michael NL, Douek DC, Ananworanich J, Utay NS, RV254/SEARCH 010, RV304/SEARCH 013, and SEARCH 011 protocol teams. 2017. Persistent, albeit reduced, chronic inflammation in persons starting antiretroviral therapy in acute HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis 64:124–131. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ho DD, Zhang L. 2000. HIV-1 rebound after anti-retroviral therapy. Nat Med 6:736–737. doi: 10.1038/77447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Borducchi EN, Cabral C, Stephenson KE, Liu J, Abbink P, Ng’ang’a D, Nkolola JP, Brinkman AL, Peter L, Lee BC, Jimenez J, Jetton D, Mondesir J, Mojta S, Chandrashekar A, Molloy K, Alter G, Gerold JM, Hill AL, Lewis MG, Pau MG, Schuitemaker H, Hesselgesser J, Geleziunas R, Kim JH, Robb ML, Michael NL, Barouch DH. 2016. Ad26/MVA therapeutic vaccination with TLR7 stimulation in SIV-infected rhesus monkeys. Nature 540:284–287. doi: 10.1038/nature20583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fennessey CM, Pinkevych M, Immonen TT, Reynaldi A, Venturi V, Nadella P, Reid C, Newman L, Lipkey L, Oswald K, Bosche WJ, Trivett MT, Ohlen C, Ott DE, Estes JD, Del Prete GQ, Lifson JD, Davenport MP, Keele BF. 2017. Genetically-barcoded SIV facilitates enumeration of rebound variants and estimation of reactivation rates in nonhuman primates following interruption of suppressive antiretroviral therapy. PLoS Pathog 13:e1006359. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Whitney JB, Hill AL, Sanisetty S, Penaloza-MacMaster P, Liu J, Shetty M, Parenteau L, Cabral C, Shields J, Blackmore S, Smith JY, Brinkman AL, Peter LE, Mathew SI, Smith KM, Borducchi EN, Rosenbloom DI, Lewis MG, Hattersley J, Li B, Hesselgesser J, Geleziunas R, Robb ML, Kim JH, Michael NL, Barouch DH. 2014. Rapid seeding of the viral reservoir prior to SIV viraemia in rhesus monkeys. Nature 512:74–77. doi: 10.1038/nature13594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abreu CM, Veenhuis RT, Avalos CR, Graham S, Queen SE, Shirk EN, Bullock BT, Li M, Metcalf Pate KA, Beck SE, Mangus LM, Mankowski JL, Clements JE, Gama L. 2019. Infectious virus persists in CD4+ T cells and macrophages in ART-suppressed SIV-infected Macaques. J Virol 93:e00065-19. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00065-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.INSIGHT START Study Group, Lundgren JD, Babiker AG, Gordin F, Emery S, Grund B, Sharma S, Avihingsanon A, Cooper DA, Fatkenheuer G, Llibre JM, Molina JM, Munderi P, Schechter M, Wood R, Klingman KL, Collins S, Lane HC, Phillips AN, Neaton JD. 2015. Initiation of antiretroviral therapy in early asymptomatic HIV infection. N Engl J Med 373:795–807. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith PD, Smythies LE, Mosteller-Barnum M, Sibley DA, Russell MW, Merger M, Sellers MT, Orenstein JM, Shimada T, Graham MF, Kubagawa H. 2001. Intestinal macrophages lack CD14 and CD89 and consequently are down-regulated for LPS- and IgA-mediated activities. J Immunol 167:2651–2656. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.5.2651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smythies LE, Sellers M, Clements RH, Mosteller-Barnum M, Meng G, Benjamin WH, Orenstein JM, Smith PD. 2005. Human intestinal macrophages display profound inflammatory anergy despite avid phagocytic and bacteriocidal activity. J Clin Invest 115:66–75. doi: 10.1172/JCI19229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Crowe S, Zhu T, Muller WA. 2003. The contribution of monocyte infection and trafficking to viral persistence, and maintenance of the viral reservoir in HIV infection. J Leukoc Biol 74:635–641. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0503204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kelly J, Beddall MH, Yu D, Iyer SR, Marsh JW, Wu Y. 2008. Human macrophages support persistent transcription from unintegrated HIV-1 DNA. Virology 372:300–312. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Veazey RS, Tham IC, Mansfield KG, DeMaria M, Forand AE, Shvetz DE, Chalifoux LV, Sehgal PK, Lackner AA. 2000. Identifying the target cell in primary simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection: highly activated memory CD4(+) T cells are rapidly eliminated in early SIV infection in vivo. J Virol 74:57–64. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.1.57-64.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lay MD, Petravic J, Gordon SN, Engram J, Silvestri G, Davenport MP. 2009. Is the gut the major source of virus in early simian immunodeficiency virus infection? J Virol 83:7517–7523. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00552-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rabezanahary H, Moukambi F, Palesch D, Clain J, Racine G, Andreani G, Benmadid-Laktout G, Zghidi-Abouzid O, Soundaramourty C, Tremblay C, Silvestri G, Estaquier J. 2020. Despite early antiretroviral therapy effector memory and follicular helper CD4 T cells are major reservoirs in visceral lymphoid tissues of SIV-infected macaques. Mucosal Immunol 13:149–160. doi: 10.1038/s41385-019-0221-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ling B, Mohan M, Lackner AA, Green LC, Marx PA, Doyle LA, Veazey RS. 2010. The large intestine as a major reservoir for simian immunodeficiency virus in macaques with long-term, nonprogressing infection. J Infect Dis 202:1846–1854. doi: 10.1086/657413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Baxter AE, Russell RA, Duncan CJ, Moore MD, Willberg CB, Pablos JL, Finzi A, Kaufmann DE, Ochsenbauer C, Kappes JC, Groot F, Sattentau QJ. 2014. Macrophage infection via selective capture of HIV-1-infected CD4+ T cells. Cell Host Microbe 16:711–721. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Calantone N, Wu F, Klase Z, Deleage C, Perkins M, Matsuda K, Thompson EA, Ortiz AM, Vinton CL, Ourmanov I, Lore K, Douek DC, Estes JD, Hirsch VM, Brenchley JM. 2014. Tissue myeloid cells in SIV-infected primates acquire viral DNA through phagocytosis of infected T cells. Immunity 41:493–502. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Campillo-Gimenez L, Laforge M, Fay M, Brussel A, Cumont MC, Monceaux V, Diop O, Levy Y, Hurtrel B, Zaunders J, Corbeil J, Elbim C, Estaquier J. 2010. Nonpathogenesis of simian immunodeficiency virus infection is associated with reduced inflammation and recruitment of plasmacytoid dendritic cells to lymph nodes, not to lack of an interferon type I response, during the acute phase. J Virol 84:1838–1846. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01496-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Keating SM, Heitman JW, Wu S, Deng X, Stacey AR, Zahn RC, de la Rosa M, Finstad SL, Lifson JD, Piatak M Jr, Gauduin MC, Kessler BM, Ternette N, Carville A, Johnson RP, Desrosiers RC, Letvin NL, Borrow P, Norris PJ, Schmitz JE. 2016. Magnitude and quality of cytokine and chemokine storm during acute infection distinguish nonprogressive and progressive simian immunodeficiency virus infections of nonhuman primates. J Virol 90:10339–10350. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01061-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kornfeld C, Ploquin MJ, Pandrea I, Faye A, Onanga R, Apetrei C, Poaty-Mavoungou V, Rouquet P, Estaquier J, Mortara L, Desoutter JF, Butor C, Le Grand R, Roques P, Simon F, Barre-Sinoussi F, Diop OM, Muller-Trutwin MC. 2005. Antiinflammatory profiles during primary SIV infection in African green monkeys are associated with protection against AIDS. J Clin Invest 115:1082–1091. doi: 10.1172/JCI23006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Campillo-Gimenez L, Cumont MC, Fay M, Kared H, Monceaux V, Diop O, Muller-Trutwin M, Hurtrel B, Levy Y, Zaunders J, Dy M, Leite-de-Moraes MC, Elbim C, Estaquier J. 2010. AIDS progression is associated with the emergence of IL-17-producing cells early after simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J Immunol 184:984–992. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Laforge M, Silvestre R, Rodrigues V, Garibal J, Campillo-Gimenez L, Mouhamad S, Monceaux V, Cumont MC, Rabezanahary H, Pruvost A, Cordeiro-da-Silva A, Hurtrel B, Silvestri G, Senik A, Estaquier J. 2018. The anti-caspase inhibitor Q-VD-OPH prevents AIDS disease progression in SIV-infected rhesus macaques. J Clin Invest 128:1627–1640. doi: 10.1172/JCI95127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chensue SW, Warmington KS, Berger AE, Tracey DE. 1992. Immunohistochemical demonstration of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist protein and interleukin-1 in human lymphoid tissue and granulomas. Am J Pathol 140:269–275. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chevalier MF, Petitjean G, Dunyach-Remy C, Didier C, Girard PM, Manea ME, Campa P, Meyer L, Rouzioux C, Lavigne JP, Barre-Sinoussi F, Scott-Algara D, Weiss L. 2013. The Th17/Treg ratio, IL-1RA and sCD14 levels in primary HIV infection predict the T-cell activation set point in the absence of systemic microbial translocation. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003453. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kreuzer KA, Dayer JM, Rockstroh JK, Sauerbruch T, Spengler U. 1997. The IL-1 system in HIV infection: peripheral concentrations of IL-1beta, IL-1 receptor antagonist and soluble IL-1 receptor type II. Clin Exp Immunol 109:54–58. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1997.4181315.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dunay IR, Damatta RA, Fux B, Presti R, Greco S, Colonna M, Sibley LD. 2008. Gr1(+) inflammatory monocytes are required for mucosal resistance to the pathogen Toxoplasma gondii. Immunity 29:306–317. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Grainger JR, Wohlfert EA, Fuss IJ, Bouladoux N, Askenase MH, Legrand F, Koo LY, Brenchley JM, Fraser ID, Belkaid Y. 2013. Inflammatory monocytes regulate pathologic responses to commensals during acute gastrointestinal infection. Nat Med 19:713–721. doi: 10.1038/nm.3189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Iijima N, Mattei LM, Iwasaki A. 2011. Recruited inflammatory monocytes stimulate antiviral Th1 immunity in infected tissue. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:284–289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005201108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Little MC, Hurst RJ, Else KJ. 2014. Dynamic changes in macrophage activation and proliferation during the development and resolution of intestinal inflammation. J Immunol 193:4684–4695. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.van Furth R, Cohn ZA. 1968. The origin and kinetics of mononuclear phagocytes. J Exp Med 128:415–435. doi: 10.1084/jem.128.3.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zigmond E, Varol C, Farache J, Elmaliah E, Satpathy AT, Friedlander G, Mack M, Shpigel N, Boneca IG, Murphy KM, Shakhar G, Halpern Z, Jung S. 2012. Ly6C hi monocytes in the inflamed colon give rise to proinflammatory effector cells and migratory antigen-presenting cells. Immunity 37:1076–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Allers K, Fehr M, Conrad K, Epple HJ, Schurmann D, Geelhaar-Karsch A, Schinnerling K, Moos V, Schneider T. 2014. Macrophages accumulate in the gut mucosa of untreated HIV-infected patients. J Infect Dis 209:739–748. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cassol E, Rossouw T, Malfeld S, Mahasha P, Slavik T, Seebregts C, Bond R, Du Plessis J, Janssen C, Roskams T, Nevens F, Alfano M, Poli G, van der Merwe SW. 2015. CD14(+) macrophages that accumulate in the colon of African AIDS patients express pro-inflammatory cytokines and are responsive to lipopolysaccharide. BMC Infect Dis 15:430. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-1176-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ortiz AM, DiNapoli SR, Brenchley JM. 2015. Macrophages are phenotypically and functionally diverse across tissues in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected and uninfected Asian macaques. J Virol 89:5883–5894. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00005-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Swan ZD, Wonderlich ER, Barratt-Boyes SM. 2016. Macrophage accumulation in gut mucosa differentiates AIDS from chronic SIV infection in rhesus macaques. Eur J Immunol 46:446–454. doi: 10.1002/eji.201545738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Franc NC, Dimarcq JL, Lagueux M, Hoffmann J, Ezekowitz RA. 1996. Croquemort, a novel Drosophila hemocyte/macrophage receptor that recognizes apoptotic cells. Immunity 4:431–443. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80410-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hanayama R, Tanaka M, Miwa K, Shinohara A, Iwamatsu A, Nagata S. 2002. Identification of a factor that links apoptotic cells to phagocytes. Nature 417:182–187. doi: 10.1038/417182a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Miyanishi M, Tada K, Koike M, Uchiyama Y, Kitamura T, Nagata S. 2007. Identification of Tim4 as a phosphatidylserine receptor. Nature 450:435–439. doi: 10.1038/nature06307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Savill J, Hogg N, Ren Y, Haslett C. 1992. Thrombospondin cooperates with CD36 and the vitronectin receptor in macrophage recognition of neutrophils undergoing apoptosis. J Clin Invest 90:1513–1522. doi: 10.1172/JCI116019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cros J, Cagnard N, Woollard K, Patey N, Zhang SY, Senechal B, Puel A, Biswas SK, Moshous D, Picard C, Jais JP, D’Cruz D, Casanova JL, Trouillet C, Geissmann F. 2010. Human CD14dim monocytes patrol and sense nucleic acids and viruses via TLR7 and TLR8 receptors. Immunity 33:375–386. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]