Abstract

Objective

Suboptimal health status (SHS), a third state between good health and disease, can easily develop into chronic diseases, and can be influenced by lifestyle and health consciousness. No study has surveyed the intermediation of health consciousness on the relationship between lifestyle and SHS. This study aimed to analyse the association of lifestyle and SHS, and intermediation of health consciousness in Chinese urban residents.

Design

A cross-sectional face-to-face survey using a four-stage stratified sampling method.

Participants

We investigated 5803 Chinese urban residents aged 18 years and over. We measured SHS using the Sub-Health Measurement Scale V1.0. We adopted a structural equation model to analyse relationships among lifestyle, health consciousness and SHS. We applied a bootstrapping method to estimate the mediation effect of health consciousness.

Results

Lifestyle had stronger indirect associations with physical (β −0.185, 95% CI −0.228 to −0.149), mental (β −0.224, 95% CI −0.265 to −0.186) and social SHS (β −0.216, 95% CI −0.257 to −0.179) via health consciousness than direct associations of physical (β −0.144, 95% CI −0.209 to −0.081), mental (β −0.146, 95% CI −0.201 to −0.094) and social SHS (β −0.130, 95% CI −0.181 to −0.077). Health consciousness has a strong direct association with physical (β 0.360, 95% CI 0.295 to 0.427), mental (β 0.452, 95% CI 0.392 to 0.510) and social SHS (β 0.434, 95% CI 0.376 to 0.490). Ratio of mediating effect of health consciousness to direct effect of lifestyle with physical, mental and social SHS was 1.28, 1.53 and 1.66, respectively.

Conclusions

Health consciousness was more important in preventing physical, mental and social SHS than lifestyle. Therefore, it might be useful in changing unhealthy lifestyle and reducing the influence of poor lifestyle on physical, mental and social SHS.

Keywords: public health, health policy, risk management

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The participants, who were recruited through a cross-sectional survey using a four-stage stratified sampling method, were representative of Chinese urban residents.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first representative analysis of the mediating effect of health consciousness on the association of lifestyle with physical, mental and social suboptimal health status.

Although we used a four-stage stratified sampling method, sampling errors are still inevitable.

This study only included the seven most common lifestyle factors.

Introduction

In 1946, the WHO1 defined health as ‘a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’. It is reported that non-communicable diseases (NCDs) account for an estimated 80% of the total deaths and 70% of the total number of disability-adjusted life-years in the early twentieth century.2 Moreover, NCD increase steadily with urbanisation and ageing,3 being attributed with more than 88% of total deaths in China in 2019.4 Furthermore, a study pointed out that NCDs accounted for 18 of the 20 leading causes of age-standardised years lived with disability on a global scale.5 The preclinical status of NCDs and its early detection have become major issues in the promotion of basic health service in the reform of healthcare.6

Suboptimal health status (SHS), an intermediate status between chronic disease and health, is believed to be a subclinical and reversible stage of chronic disease.7 People in SHS, although without a diagnosable condition, are characterised by a decline in vitality and physiological function, ambiguous health complaints, general weakness and lack of vitality. In fact, it has become a new public health challenge in China.8 9

It is reported that SHS can be measured objectively using microbiome,10 telomere length,11 plasma stress hormones,12 plasma metabolites13 and glycan.14 However, these objective measures are not easily accessible, and sometimes may not be obvious, especially when people have uncomfortable feelings without abnormal symptoms. A self-rated method that uses a questionnaire is widely applicable in assessing SHS. In China, the Sub-Health Measurement Scale (SHMS V1.0), Suboptimal Health Status Questionnaire (SHSQ-25)15 and Chinese Sub-Health Scale (CSHES)16 were widely used for assessing SHS. However, compared with the other questionnaires, SHMS V1.0 assesses of the physical, mental and social aspects of SHS, which is in accordance with the health concept proposed by WHO in 1947.

SHS has a prevalence of above 65% in China,17–20 and has become an increasingly concerning problem in many countries.21 22 Moreover, its prevalence may be severely underestimated since many individuals are not aware that they suffer from SHS. For instance, in an investigation involving 6000 Chinese self-reported ‘healthy people,’ 72.8% were in ‘suboptimal health status.’23 Thus, identifying the influencing factors of SHS is important in preventing it, and would provide important information for first-level prevention of NCD.24 In accordance with the definition released by the WHO, SHS has three dimensions: physical, mental and social adaption.25 SHS concept is mainly based on Transitional Chinese Medicine and prevention is important.26 27

Lifestyle is an important factor associated with SHS. This includes smoking, alcohol use, skipping breakfast, poor nutrition, lack of exercise and sleep problems.28 29 The first SHS study on urban Chinese population9 pointed that SHS was associated with risk factors of chronic diseases and contributed to the development of them. In SHS, individuals can prevent a chronic disease by modifying their poor lifestyles, as supported by China’s Blue Book on Self-Care.30 Although, it is a given fact that individuals ought to change their bad lifestyles when experiencing adverse health issues, this is difficult to achieve in practice.31 32 Studies revealed that better knowledge and strong beliefs improve the adherence to lifestyle changes33 34 and prevent and control chronic diseases;35 36 better knowledge and strong beliefs are important expressions of health consciousness.

Health consciousness is a psychological construct that corresponds to the awareness about one’s health, and the willingness to change one’s behaviours in order to improve it.37 38 Moreover, it is related to anxiety, stress, depression and non-treatable diseases.39 However, to our knowledge, there are no studies on the association of health consciousness to SHS. People may present different suboptimal health states in their physical, mental and social adaptation; thus, it is necessary to analyse SHS separately. We aimed to investigate whether improved health consciousness is associated with better lifestyle and less physical, mental and social SHS. Moreover, we aimed to discover the possible mediating effect of health consciousness on the association of lifestyle with physical, mental and social SHS. Thus, we used structural equation models to clarify these questions, on the basis of a representative sample of Chinese urban residents.

Methods

Study design and population

We conducted a cross-sectional survey using a four-stage stratified sampling method from December 2017 to October 2018. In the first stage, we chose one province each from five administrative divisions in China; we selected Guangdong province, Heilongjiang province, Sichuan province, Gansu province and Tianjin city. Second, we chose three to four cities from each province by considering their level of economic development and regional distribution. Subsequently, we randomly selected two to four streets in the selected urban areas. Lastly, we investigated the urban residents who conveniently qualified from each street.

This study included individuals aged 18 years and older, who lived in an urban area for more than 6 months, and volunteered in our investigation. We excluded individuals who had a confirmed disease in the last 2 months, were unable to complete the questionnaire due to visual or hearing impairment and with missing values in lifestyle, health consciousness and SHS items. We investigated a total of 6578 individuals and excluded 775. Thus, we analysed a total of 5803 urban residents. Among them, 1704, 1328, 954, 925 and 892 participants were from Guangdong, Heilongjiang, Sichuan, Gansu and Tianjin provinces, respectively. All participants that volunteered provided their verbal consent prior to data collection, and were given the option to cease from participating anytime. They were also invited to give advices regarding the questionnaire. All data were kept strictly confidential.

Patient and public involvement

The participants were not involved in the development of the research question or design of this study. However, we disseminated the results of this analysis through public conferences, including summarised statements and open access to the published reports.

Survey instrument

We used a self-designed questionnaire for investigation, which is comprised of four parts: general demographic characteristics, which included age, gender, marital status, highest education level, per capita monthly household income and insurance; lifestyle, which included smoking, bad diet habit, alcohol intake, breakfast consumption, physical exercise, early to bed (before 11 p.m.) and sleep time; health consciousness, which included health knowledge, care for health and effect of leisure promoting health; and SHMS V1.0. Each volunteer completed the questionnaire within 30 min. Verbal consents were deemed to be sufficient because the participants had volunteered for the study and could refuse to take part if they wished. The objective of the survey was to study the health status of the participants rather than intervene. All data were kept strictly confidential. The ethics committee approved the consent procedure.

SHS assessment

We performed SHS assessment using SHMS V1.0, which was developed by our research group. It comprised of 39 items25 that were proven to have high reliability and validity in a Chinese population.40 SHMS V1.0 consists of three subscales: physical suboptimal health status (PS), mental suboptimal health status (MS), and social suboptimal health status (SS). PS consists of 14 items that comprises four factors: physical condition, organ function, body movement function and vigour. MS consists of 12 items that comprises three factors: positive emotion, psychological symptoms and cognitive function. SS consists of 9 items that comprises three factors: social adjustment, social resources and social support. For each item, there are five response categories (1=none, 2=occasionally, 3=sometimes, 4=constantly and 5=always) that correspond to the frequency of occurrence of each symptom. We asked the participants regarding the uncomfortable symptoms that they had during the previous month. We then calculated the total scores. A low total score represents a low estimate of SHS (ie, poor health). The cut-off value for suboptimal health assessment referred to norms of SHMS V1.0 for Chinese urban residents were established by our research group.41

Lifestyle evaluation

Smoking was comprised of none smokers, past smokers and current smokers. Bad diet habit was divided into ‘yes’ (if any one of the following seven situations exist: irregular eating time, dieting, overeating, dietary bias or pickiness, salty tasty, spicy tasty and using snacks instead of meals), and ‘no’. Alcohol intake was divided into ‘never’, ‘occasionally’, ‘little everyday’ and ‘much everyday’. Breakfast consumption was comprised of ‘never’, ‘occasionally’ (ie, 1 or 2 days a week), ‘sometimes’ (ie, 3 or 4 days a week), ‘frequently’ (ie, 5 or 6 days a week) and ‘everyday’. Physical exercise was divided into ‘everyday’, ‘frequently’ (ie, 5 or 6 days a week), ‘sometimes’ (ie, 3 or 4 days a week) and ‘occasionally’ (ie, 1 or 2 days a week, and no physical exercise). Sleep time were divided into three groups, ‘<7 hours/day’, ‘7 to 9 hours/day’ and ‘≥9 hours/day’.

Health consciousness evaluation

Health knowledge and attention to health consisted of ‘very few/low’, ‘few/low’, ‘general’, ‘much/high’ and ‘very much/high’. Effect of leisure on health consisted of ‘no effect’, ‘some effect’ and ‘very effective’.

Quality control and data management

The investigators for each site were trained through face-to-face, video conferencing and telephone. Before the conduct of the investigation, we made sure that its purpose and importance were explained to the participants in detail, and obtained their verbal informed consent. The respondents answered the questionnaires independently and according to their own understanding, while missing data were re-answered after checking by the investigators. Before data coding and entry, suspicious duplicate questionnaires, which are those with a repetition rate higher than 80% and completion rate lower than 80% were excluded. All questionnaire data were double-entered using EpiData 3.1 software. The two data sets were cross compared for validity and errors.

Statistical analysis

Description was using means (SD) and proportions. We used a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with least significant difference test for multiple comparisons. Cluster effect nested within sampling regions was examined by using interclass correlation coefficient (ICC) calculated in a two-level linear multilevel model. We used structural equation modelling (SEM) to analyse the complexity of associations between lifestyle, health consciousness and SHS (Model 1: SEM model of lifestyle, health consciousness and PS; Model 2: SEM model of lifestyle, health consciousness and MS; Model 3: SEM model of lifestyle, health consciousness and SS). Mediating effect of health consciousness was the same with indirect association of lifestyle and SHS via health consciousness. Ratio of mediating effect of health consciousness to direct effect of lifestyle (indirect effect divided by direct effect) and proportion of mediating effect of health consciousness to total effect (indirect effect divided by total effect multiply by a hundred) of lifestyle with physical, mental and social SHS were also calculated. We used the relative χ2 minimum discrepancy per degree of freedom (CMIN/DF), root mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI), goodness-of-fit index (GFI), and adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI) to assess the model fit. We applied the bootstrapping method of repeat sampling by 2000 times to verify statistical significance and calculate the CIs for the direct, indirect and total effects. Participants with missing data were deleted from analysis. All p values were two-sided, with values <0.05 considered as statistically significant. We used IBM SPSS Statistics 20.0 for descriptive analysis. Lastly, we conducted SEM analysis with AMOS (SPSS Statistics V.20·0, SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

Participants’ demographic characteristics

Baseline characteristics of all study participants are presented in table 1. Of the 5803 participants, 2772 (47.77%) were men and 3031 (52.23%) were women. The mean age was 40.90±15.46 years. Most of the participants (65.98%) were married. Moreover, 3320 (57.21%) of the participants have a per capita monthly household income (RMB) of less than 5000 RMB. Participants with compulsory school (up to grade 9), high school, junior college and university degree and above were 1343 (23.14%), 1298 (22.37%), 1374 (23.68%) and 1786 (30.78%), respectively.

Table 1.

Participant’s demographic characteristics (n=3535)

| Characteristic | N | % |

| Gender | ||

| Man | 2772 | 47.77 |

| Woman | 3031 | 52.23 |

| Married status | ||

| Unmarried | 1556 | 26.81 |

| Married | 3829 | 65.98 |

| Divorced or widows | 386 | 6.65 |

| Information missing | 32 | 0.55 |

| Per capita monthly household income (RMB) | ||

| <5000 | 3320 | 57.21 |

| >=5000 | 2419 | 41.69 |

| Information missing | 64 | 1.10 |

| Highest education level | ||

| Compulsory school (through grade 9) | 1343 | 23.14 |

| High school graduation | 1298 | 22.37 |

| Junior college degree | 1374 | 23.68 |

| University degree and above | 1786 | 30.78 |

| Information missing | 2 | 0.03 |

Association of lifestyle, health consciousness and SHS

The mean (SD) of the overall SHS, PS, MS and SS transformed scores were 67.15 (11.99), 70.92 (12.67), 67.01 (14.55) and 61.46 (15.56), respectively. The ANOVA results showed that various groups of lifestyle and health consciousness differed on physical SHS, mental SHS and social SHS (table 2). People who never smoked had the highest physical and social SHS scores; however, participants who quit smoking had lower physical, mental and social SHS scores than participants who were still smoking. People who had bad diet habits and consumed the most alcohol had the lowest physical, mental and social SHS scores. Physical, mental and social SHS scores were higher for participants who regularly consumed breakfast, engaged in regular physical exercise, had early bedtimes (ie, before 11 p.m.) and longer sleep duration.

Table 2.

Group comparisons of lifestyle, health consciousness and suboptimal health status

| Variates | N | PS mean (SE) | MS mean (SE) | SS mean (SE) |

| Smoking | ||||

| Never | 3987 | 71.56 (12.48)†, ‡ | 67.13 (14.46)† | 62.15 (15.16)†, ‡ |

| Quit | 614 | 68.32 (13.49)*, ‡, § | 65.41 (15.11)*, ‡, § | 58.38 (17.2)*, ‡ |

| <20 cigarettes/day | 1027 | 70.31 (12.67)*, † | 67.4 (14.44)† | 60.93 (15.53)*, † |

| ≥20 cigarettes/day | 164 | 70.85 (12.90)† | 68.26 (15.44)† | 61.02 (17.86) |

| Bad diet habits | ||||

| No | 3357 | 73.1 (12.52)† | 70.2 (14.14)† | 64.19 (14.77)† |

| Yes | 2446 | 67.92 (12.25)* | 62.64 (13.97)* | 57.71 (15.84)* |

| Alcohol intake | ||||

| Never | 2077 | 71.93 (13.13)†, ‡, §, ¶ | 68.18 (14.66)†, ‡, §, ¶ | 62.61 (15.78)†, ‡, ¶ |

| Occasionally | 3099 | 70.86 (12.06)*, ‡, §, ¶ | 66.55 (14.21)*, ¶ | 61.15 (15.11)*, ¶ |

| Little everyday | 421 | 68.85 (13.65)*, †, ¶ | 66.29 (15.75)*, ¶ | 59.93 (16.69)*, ¶ |

| Some everyday | 106 | 68.35 (12.88)*, †, ¶ | 65.17 (13.79)*, ¶ | 60.27 (14.29)¶ |

| Much everyday | 72 | 63.47 (14.37)*, †, ‡, § | 60.1 (16.45)*, †, ‡, § | 53.97 (20.69)*, †, ‡, § |

| Breakfast consumption | ||||

| Never | 139 | 67.93 (15.07)§, ¶ | 62.4 (17.25)§, ¶ | 53.46 (19.83)‡, §, ¶ |

| Occasionally | 600 | 66.88 (12.63)§, ¶ | 62.69 (14.12)§, ¶ | 55.79 (16.70)§, ¶ |

| Sometimes | 830 | 68.03 (11.99)§, ¶ | 61.81 (13.07)§, ¶ | 56.37 (15.38)*, §, ¶ |

| Frequently | 1539 | 71.07 (11.94)*, †, ‡, ¶ | 66.48 (14.01)*, †, ‡, ¶ | 61.75 (14.52)*, †, ‡, ¶ |

| Everyday | 2671 | 72.91 (12.73)*, †, ‡, § | 70.22 (14.46)*, †, ‡, § | 64.69 (14.75)*, †, ‡, § |

| Physical exercise | ||||

| Never | 848 | 68.55 (13.27)†, ‡, §, ¶ | 64.24 (14.4) †, ‡, §, ¶ | 58.21 (15.68)†, ‡, §, ¶ |

| Occasionally | 2338 | 70.43 (11.78)*, §, ¶ | 65.54 (13.92)*, ‡, §, ¶ | 60.36 (14.45)*, ‡, §, ¶ |

| Sometimes | 1373 | 71.26 (13.11)*, ¶ | 67.54 (14.53)*, †, § | 61.51 (16.75)*, †, §, ¶ |

| Frequently | 608 | 71.77 (13.03)*, †, ¶ | 68.72 (14.85)*, †, ‡ | 64.57 (15.24)*, †, ‡, ¶ |

| Everyday | 627 | 74.73 (12.73)*, †, ‡, § | 73.53 (14.82)*, †, ‡, § | 67.12 (15.11)*, †, ‡, § |

| Early to bed | ||||

| Never | 947 | 70.29 (12.36)§, ¶ | 64.8 (14.74)§, ¶ | 59.72 (15.61)§, ¶ |

| Occasionally | 1512 | 70.3 (11.94)§, ¶ | 65.57 (13.71)§, ¶ | 60.08 (15.33)§, ¶ |

| Sometimes | 1224 | 70.01 (12.84)§, ¶ | 65.84 (14.46)*, †, §, ¶ | 60.47 (15.99)§, ¶ |

| Frequently | 997 | 71.49 (12.76)*, †, ‡, ¶ | 68.36 (14.46)*, †, ‡, ¶ | 63.07 (14.79)*, †, ‡, ¶ |

| Everyday | 1113 | 72.98 (13.39)*, †, ‡, § | 70.99 (14.84)*, †, ‡, § | 64.52 (15.49)*, †, ‡, § |

| Sleep time | ||||

| <3 hours/day | 35 | 62.96 (12.11)‡, §, ¶ | 58.87 (13.81)‡, §, ¶ | 49.68 (20.42)‡, §, ¶ |

| <5 hours/day | 145 | 62.44 (12.88)‡, §, ¶ | 56.97 (14.78)‡, §, ¶ | 48.51 (18.88)‡, §, ¶ |

| <7 hours/day | 1377 | 67.89 (12.34)*, †, §, ¶ | 64.88 (14.09)*, †, §, ¶ | 59.86 (15.83)*, †, §, ¶ |

| <9 hours/day | 3748 | 72.47 (12.29)*, †, ‡, ¶ | 68.14 (14.38)*, †, ‡ | 62.65 (14.82)*, †, ‡ |

| ≥9 hours/day | 492 | 71.09 (13.67)*, †, ‡, § | 68.15 (15.30)*, †, ‡ | 61.95 (16.59)*, †, ‡ |

| Health knowledge | ||||

| Very few | 1332 | 70.27 (12.55)§, ¶ | 65.17 (14.79)‡, §, ¶ | 58.31 (15.43)†, ‡, §, ¶ |

| Few | 1794 | 70.38 (12.51) §, ¶ | 65.77 (14.27)‡, §, ¶ | 60.13 (15.41)*, ‡, §, ¶ |

| General | 1913 | 70.71 (12.52)§, ¶ | 67.54 (14.37)*, †, §, ¶ | 62.55 (15.13)*, †, §, ¶ |

| Much | 628 | 74.11 (12.58)*, †, ‡ | 71.47 (13.79)*, †, ‡, ¶ | 67.2 (14.62)*, †, ‡, ¶ |

| Very much | 120 | 74.65 (15.97)*, †, ‡ | 75.26 (15.28)*, †, ‡, § | 70.61 (18.46)*, †, ‡, § |

| Care for health | ||||

| Very low | 329 | 67.73 (14.32)‡, §, ¶ | 61.09 (16.65)‡, §, ¶ | 55.25 (17.71)‡, §, ¶ |

| Low | 789 | 67.61 (13.11)‡, §, ¶ | 62.33 (14.42)‡, §, ¶ | 56.1 (16.47)‡, §, ¶ |

| General | 2485 | 69.5 (11.9)*, †, §, ¶ | 65.37 (13.69)*, †, §, ¶ | 59.76 (14.35)*, †, §, ¶ |

| High | 1752 | 73.66(12)*, †, ‡, ¶ | 70.3 (13.74)*, †, ‡, ¶ | 65.28 (14.44)*, †, ‡, ¶ |

| Very high | 437 | 76.86 (13.36)*, †, ‡, § | 76.27 (14.12)*, †, ‡, § | 70.57 (15.73)*, †, ‡, § |

| Effect of leisure promoting health | ||||

| No effect | 733 | 65.7 (12.87)†, ‡ | 60.94 (14.56)†, ‡ | 54.24 (17.22)†, ‡ |

| Some effect | 3870 | 70.37 (12.04)*, ‡ | 66.1 (13.76)*, ‡ | 60.68 (14.39)*, ‡ |

| Very effective | 1163 | 76.39 (12.75)*, † | 74.11 (14.58)*, † | 69 (15.28)*, † |

Transformed scores were analysed here. Statistical analysis included a one-way analysis of variance followed by least significant difference multiple comparisons test.

*p< 0.05 as compared to answer code 1.

†p<0.05 as compared to answer code 2.

‡p<0.05 as compared to answer code 3.

§p<0.05 as compared to answer code 4.

¶p<0.05 as compared to answer code 5.

MS, mental suboptimal health status; PS, physical suboptimal health status; SS, social suboptimal health status.

SEM analysis of lifestyle, health consciousness and SHS

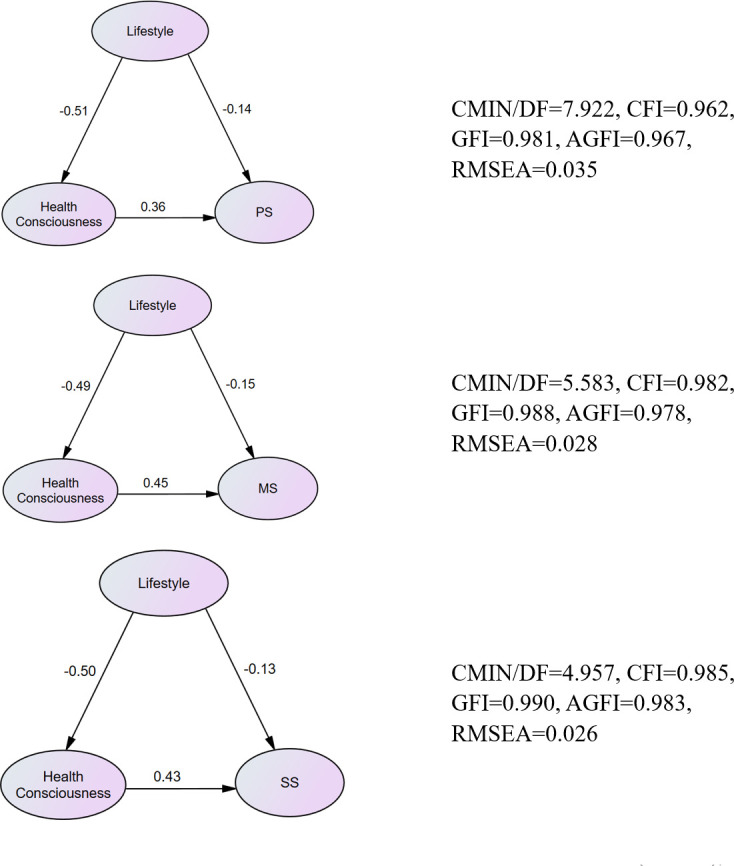

Because we used the multistage sampling method in this study, there might be a cluster effect nested within sampling regions. We examined ICC and its significance using a two-level linear multilevel model. For physical, mental and social SHS, there was no cluster effect in the regions, while the ICC was 0.028, 0.01 and 0.035, with p values of 0.085, 0.103 and 0.084, respectively. Thus, traditional SEM models could be used in the analysis of the association of lifestyle, health consciousness and SHS (figure 1). Three models fit reasonably well to the data. As shown in the models: (1) all indicator variables that we hypothesised as predictors were significantly related to their respective latent factors, p<0.001; (2) lifestyle had a direct negative association with PS (β −0.144, p<0.001), MS (β −0.146, p<0.001) and SS (β −0.130, p 0.001); (3) health consciousness had direct positive association with PS (β 0.360, p<0.001), MS (β 0.452, p<0.001) and SS (β 0.434, p<0.001), and mediating effects on the association of lifestyle with PS, MS and SS.

Figure 1.

Structural equation model of lifestyle, health consciousness and PS (model 1), MS (model 2) or SS (model 3). All the standardised regression coefficients are presented as single-headed arrows, and statistically significant at 0.05 significance level. AGFI, adjusted goodness-of-fit index; CFI, comparative fit index; CMIN/DF, minimumdiscrepancy per degree of freedom; GFI, goodness-of-fit index; MS, mental suboptimal health status; PS, physical suboptimal health status; RMSEA, root mean-square error of approximation; SS, social suboptimal health status.

The association paths of lifestyle and health consciousness on SHS are presented in table 3. Although lifestyle and health consciousness were both associated with SHS, health consciousness had larger associations with PS (β 0.360), MS (β 0.452) and SS (β 0.434) than lifestyle (β –0.329, –0.370 and −0.345 respectively). Association of lifestyle and PS could be direct (β −0.144, 95% CI −0.209 to −0.081) and indirect (β −0.185, 95% CI −0.228 to −0.149), with faintly larger indirect association than direct association. However, the indirect association (β −0.224, 95% CI −0.265 to −0.186) of lifestyle and MS was obviously higher than direct association (β −0.146, 95% CI −0.201 to −0.094). The same higher indirect association (β −0.216, 95% CI −0.257 to −0.179) was found in the association of lifestyle and SS than direct association (β −0.130, 95% CI −0.181 to −0.077). Ratio of mediating effect of health consciousness to direct effect of lifestyle with physical, mental and social SHS was 1.28, 1.53 and 1.66, respectively. Proportion of mediating effect of health consciousness to total effect of lifestyle with physical, mental and social SHS was 56.23%, 60.54% and 62.61%, respectively.

Table 3.

Influencing path of lifestyle and health consciousness on SHS

| SHS | Pathway | Mean standardised effects | 95% CI | P value | |

| Lower bound | Upper bound | ||||

| PS | |||||

| Lifestyle—PS (total) | −0.329 | −0.385 | −0.278 | <0.001 | |

| Lifestyle—PS (direct) | −0.144 | −0.209 | −0.081 | <0.001 | |

| Lifestyle—health consciousness—PS (indirect) | −0.185 | −0.228 | −0.149 | <0.001 | |

| Health consciousness—PS | 0.360 | 0.295 | 0.427 | <0.001 | |

| MS | |||||

| Lifestyle—MS (total) | −0.370 | −0.408 | −0.330 | <0.001 | |

| Lifestyle—MS (direct) | −0.146 | −0.201 | −0.094 | 0.001 | |

| Lifestyle—health consciousness—MS (indirect) | −0.224 | −0.265 | −0.186 | <0.001 | |

| Health consciousness—MS | 0.452 | 0.392 | 0.510 | <0.001 | |

| SS | |||||

| Lifestyle—SS (total) | −0.345 | −0.383 | −0.308 | <0.001 | |

| Lifestyle—SS (direct) | −0.130 | −0.181 | −0.077 | 0.001 | |

| Lifestyle—health consciousness—SS (indirect) | −0.216 | −0.257 | −0.179 | <0.001 | |

| Health consciousness—SS | 0.434 | 0.376 | 0.490 | <0.001 | |

MS, mental suboptimal health status; PS, physical suboptimal health status; SHS, suboptimal health status; SS, social suboptimal health status.

Discussion

In this large cross-sectional study involving a representative sample, we found that lifestyle health consciousness showed significantly mediating effects on the association of lifestyle with PS, MS and SS. The direct associations of PS, MS and SS with health consciousness were all significantly higher than lifestyle. However, the indirect associations of lifestyle with PS, MS and SS were higher than indirect associations via health consciousness.

SHS is a subjective feeling that lacks objective clinical diagnostics; thus, a self-assessed questionnaire is the most appropriate method of determining it. SHMS V1.0 is a multidimensional scale that includes physical, mental and social dimensions that correspond to the WHO’s more comprehensive definition of health.42 Moreover, it is widely used in China for assessing SHS in urban residents, workers and students.17 18 25 29 We found that Chinese urban residents had low scores in PS, MS and SS, which means that they are at high risk to SHS in physical, mental and social adaption. This result is in accordance with other studies involving young and middle-aged intellectuals in Guangzhou,43 Chinese migrant workers44 and those that use other SHS evaluation questionnaires in China, such as the SHSQ-25.6 9 Similarly, African14 and Caucasian45 studies showed the same SHS rate.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first representative analysis of the mediating effect of health consciousness on the association of lifestyle with physical, mental and social SHS. All variables included in lifestyle and health consciousness were accordingly significantly associated. Urban residents who engage in unhealthy lifestyle practices, such as smoking, alcohol intake, bad diet habits, irregular breakfast consumption, less physical exercises, less frequent early to bed and short sleep time were more likely to get into PS, MS and SS. A study42 revealed that breakfast eating habits are significantly associated with lifestyle, and appear to be a useful predictor of a healthy lifestyle; people who skip breakfast are prone to unhealthy behaviours, such as limited exercise.46 Moreover, insufficient sleep is associated with several health-risk behaviours,47 such as not meeting physical activity recommendations,48 using cigarettes and alcohol, and feeling sad or hopeless.49 Furthermore, poor diet was the third greatest influencing factor for physical and social health, which was in line with previous studies.50 51

This study investigated the significant associations of health consciousness with PS, MS and SS, which were relatively more significant than those of lifestyle. Moreover, in this study, health consciousness, included health knowledge, attention to health and effect of leisure on health. As the internal power of healthy behaviour, health consciousness is the most important and fundamental factor in promoting health. In fact, individuals who had more health knowledge believed that they had control over their health.52

The most important finding was that health consciousness played a mediating effect in the relationship of lifestyle with physical, mental and social SHS, which was higher than direct effect of lifestyle. Studies have shown that health consciousness is correlated with health behaviour, information seeking and health coping.53 Modifying the attitudes is effective in promoting changes in health behaviour,54 since health-conscious people are attentive to health warnings regarding the risks of having an unhealthy lifestyle.55

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, although we used face-to-face interviews, all data were collected from a respondent-completed questionnaire; thus, responses may have a level of inherent inaccuracy or bias. Second, although we used a four-stage stratified sampling method, sampling errors are still inevitable. Lastly, this study only included the seven most common lifestyle factors.

Conclusion

In this large representative cross-sectional study of Chinese urban residents, we found that direct association of lifestyle with physical, mental and social SHS were smaller than direct association and mediating effect of health consciousness. Moreover, health consciousness was more important in preventing physical, mental and social SHS than lifestyle, and might be useful in changing unhealthy lifestyle and reducing the influence of poor lifestyle on physical, mental and social SHS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all study participants. We also thank the investigators and students for their assistance in this research.

Footnotes

Contributors: JX developed the questionnaire and study design, supervised the analysis and contributed to the final version of the manuscript. YX did the analyses and wrote the first draft. GL, YF, MX, YL and LJ were in charge of the investigation. All authors contributed to and read the final draft of the manuscript.

Funding: This research was supported by the National Natural Science Fund, National Natural Science Foundation of China (No: 71673126), the Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangzhou City of China (No: 201803010089) and a Grant from Public Health Service System Construction Research Foundation of Guangzhou (2018–2020). The sponsors of the study had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis or data interpretation. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval to collect the patients’ data was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Nanfang Hospital of Southern Medical University (NFEC-2019-196).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request. Readers can contact Xu Jun (drugstat@163.com) to submit raw data access requirements.

References

- 1.World Health Organization What is the WHO definition of health? World Health Organization, 2020. Available: http://www.who.int/suggestions/faq/en/

- 2.Strong K, Mathers C, Leeder S, et al. Preventing chronic diseases: how many lives can we save? Lancet 2005;366:1578–82. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67341-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang L, Kong L, Wu F, et al. Preventing chronic diseases in China. Lancet 2005;366:1821–4. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67344-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Transcript of press conference of the office of health China action promotion committee on July 31, 2019. Available: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/s7847/201907/0d95adec49f84810a6d45a0a1e997d67.shtml

- 5.GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet 2016;388:1459–544. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Y, Ge S, Yan Y, et al. China suboptimal health cohort study: rationale, design and baseline characteristics. J Transl Med 2016;14:291–302. 10.1186/s12967-016-1046-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang W. Suboptimal health: a potential preventive instrument for non-communicable disease control and management. J Transl Med 2012;10:A45 10.1186/1479-5876-10-S2-A45 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yan Y-X, Liu Y-Q, Li M, et al. Development and evaluation of a questionnaire for measuring suboptimal health status in urban Chinese. J Epidemiol 2009;19:333–41. 10.2188/jea.JE20080086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yan YX, Dong J, Liu YQ, et al. Association of suboptimal health status and cardiovascular risk factors in urban Chinese workers. J Urban Health 2012;89:329–38. 10.1007/s11524-011-9636-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun Q, Xu X, Zhang J, et al. Association of suboptimal health status with intestinal microbiota in Chinese youths. J Cell Mol Med 2020;24:1837–47. 10.1111/jcmm.14880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alzain MA, Asweto CO, Zhang J, et al. Telomere length and accelerated biological aging in the China suboptimal health cohort: a case-control study. OMICS 2017;21:333–9. 10.1089/omi.2017.0050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan Y-X, Wu L-J, Xiao H-B, et al. Latent class analysis to evaluate performance of plasma cortisol, plasma catecholamines, and SHSQ-25 for early recognition of suboptimal health status. Epma J 2018;9:299–305. 10.1007/s13167-018-0144-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang H, Tian Q, Zhang J, et al. Population-Based case-control study revealed metabolomic biomarkers of suboptimal health status in Chinese population-potential utility for innovative approach by predictive, preventive, and personalized medicine. Epma J 2020;11:147–60. 10.1007/s13167-020-00200-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adua E, Memarian E, Russell A, et al. Utilization of N-glycosylation profiles as risk stratification biomarkers for suboptimal health status and metabolic syndrome in a Ghanaian population. Biomark Med 2019;13:1273–87. 10.2217/bmm-2019-0005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan YX, Dong J, Li M, et al. Establishment of cut off point for suboptimal health status using SHSQ-25. Chi J Health Statistics 2011;28:256–8. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu L, HM N, Shen HY, et al. Item selection in development of Chinese sub-health state evaluation scale. Chi J Health Statistics 2012;29:10–13. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xue YL, Xu J, Liu GH, et al. Study of association between personality and sub-health status among urban residents aged more than 14 years old in 4 cities in China. J Southern Med Univ 2019;39:443–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xue YL, Xu J, Liu GH, et al. The mediating effect of adversity quotient on the correlation between stressful life events and sub-health status. Modern Preventive Medicine 2019;46:82–5. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun X, Wei M, Zhu C, et al. The epidemiological investigation of sub-health status in Guangdong. Shandong Med J 2008;48:59–60. [Google Scholar]

- 20.J X, HB L, Zhu H, et al. Prevalence and influence factors of sub-health status among urban residents in Tianjin. Chin J Public Health 2016;32:76–80. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sou J, Goldenberg SM, Duff P, et al. Recent im/migration to Canada linked to unmet health needs among sex workers in Vancouver, Canada: findings of a longitudinal study. Health Care Women Int 2017;38:492–506. 10.1080/07399332.2017.1296842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dunstan RH, Sparkes DL, Roberts TK, et al. Development of a complex amino acid supplement, fatigue Reviva™, for oral ingestion: initial evaluations of product concept and impact on symptoms of sub-health in a group of males. Nutr J 2013;12:115. 10.1186/1475-2891-12-115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Z, Li M. The third state and psychosomatic medicine research. Med Philosophy 2001;22:36–8. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kupaev V, Borisov O, Marutina E, et al. Integration of suboptimal health status and endothelial dysfunction as a new aspect for risk evaluation of cardiovascular disease. Epma J 2016;7:19. 10.1186/s13167-016-0068-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bi J, Huang Y, Xiao Y, et al. Association of lifestyle factors and suboptimal health status: a cross-sectional study of Chinese students. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005156. 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang W, Russell A, Yan Y. Global health epidemiology reference group (GHERG). traditional Chinese medicine and new concepts of predictive, preventive and personalized medicine in diagnosis and treatment of suboptimal health. Epma J 2014;5:4–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang W, Yan Y. Suboptimal health: a new health dimension for translational medicine. Clin Transl Med 2012;1:1–28. 10.1186/2001-1326-1-28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lolokote S, Hidru TH, Li X. Do socio-cultural factors influence college students’ self-rated health status and health-promoting lifestyles? A cross-sectional multicenter study in Dalian, China. BMC Public Health 2017;17:478 10.1186/s12889-017-4411-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen J, Xiang H, Jiang P, et al. The role of healthy lifestyle in the implementation of regressing suboptimal health status among college students in China: a nested case-control study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017;14:240 10.3390/ijerph14030240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang Y, Yang DK, Wang RJ. 2015 annual report on the development of China's investment. China: Shanghai University of Finance and Economics Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Siripitayakunkit A, Hanucharurnkul S, Melkus GDE, et al. Factors contributing to integrating lifestyle in Thai women with type 2 diabetes. Thai J Nurs Res 2008;12:166–78. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barclay C, Procter KL, Glendenning R, et al. Can type 2 diabetes be prevented in UK general practice? A lifestyle-change feasibility study (ISAIAH). Br J Gen Pract 2008;58:541–7. 10.3399/bjgp08X319701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alm-Roijer C, Stagmo M, Udén G, et al. Better knowledge improves adherence to lifestyle changes and medication in patients with coronary heart disease. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2004;3:321–30. 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2004.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jasmine TJX, Wai-Chi SC, Hegney DG. The impact of knowledge and beliefs on adherence to cardiac rehabilitation programs in patients with heart failure: a systematic review. JBI Libr Syst Rev 2012;10:399–470. 10.11124/jbisrir-2012-53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kitson A, Brook A, Harvey G, et al. Using complexity and network concepts to inform healthcare knowledge translation. Int J Health Policy Manag 2017;7:231–43. 10.15171/ijhpm.2017.79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gazmararian JA, Williams MV, Peel J, et al. Health literacy and knowledge of chronic disease. Patient Educ Couns 2003;51:267–75. 10.1016/S0738-3991(02)00239-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gould SJ. Consumer attitudes toward health and health care: a differential perspective. J Consum Aff 1988;22:96–118. 10.1111/j.1745-6606.1988.tb00215.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Michaelidou N, Hassan LM. The role of health consciousness, food safety concern and ethical identity on attitudes and intentions towards organic food. Int J Consum Stud 2008;32:163–70. 10.1111/j.1470-6431.2007.00619.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dumitrescu AL, Kawamura M, Dogaru B, et al. Investigating the relationship between self-reported oral health status, oral health-related behaviours and self-consciousness in Romania. Oral Health Prev Dent 2008;6:95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lu Y, Xu J, Cai YJ, et al. Reliability and validity of shs measurement scale version 1.0 for measuring the shs of urban residents in three districts. Chin J Health Psychol 2013;21:707–8. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu J, Xue YL, Liu GH, et al. Establishment of the norms of Sub-Health measurement scale version 1.0 for Chinese urban residents. J South Med Univ 2019;39:271–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen J, Cheng J, Liu Y, et al. Associations between breakfast eating habits and health-promoting lifestyle, suboptimal health status in southern China: a population based, cross sectional study. J Transl Med 2014;12:348 10.1186/s12967-014-0348-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cui ZG, Xu J, WX W, et al. Study of status and its impacting factors of sub-health in young and middle-aged intellectuals in Guangzhou. Chin Med Herald 2015;12:12–16. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang XW, Xu J, WX W, et al. Status and influencing factors of Sub-health in new generation of Chinese migrant workers in pearl River delta of China. Chin Gen Prac 2017;20:95–103. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adua E, Roberts P, Wang W. Incorporation of suboptimal health status as a potential risk assessment for type II diabetes mellitus: a case-control study in a Ghanaian population. Epma J 2017;8:345–55. 10.1007/s13167-017-0119-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keski-Rahkonen A, Kaprio J, Rissanen A, et al. Breakfast skipping and health-compromising behaviors in adolescents and adults. Eur J Clin Nutr 2003;57:842–53. 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ma C, Xu W, Zhou L, et al. Association between lifestyle factors and suboptimal health status among Chinese college freshmen: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2018;18:105 10.1186/s12889-017-5002-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stea TH, Knutsen T, Torstveit MK. Association between short time in bed, health-risk behaviors and poor academic achievement among Norwegian adolescents. Sleep Med 2014;15:666–71. 10.1016/j.sleep.2014.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zahra J, Ford T, Jodrell D. Cross-Sectional survey of daily junk food consumption, irregular eating, mental and physical health and parenting style of British secondary school children. Child Care Health Dev 2014;40:481–91. 10.1111/cch.12068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nielsen MB, Gjerstad J, Frone M. Alcohol use among Norwegian workers: associations with health and well-being. Occup Med 2018;68:96–8. 10.1093/occmed/kqy014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Steele J, Fisher J, Skivington M, et al. A higher effort-based paradigm in physical activity and exercise for public health: making the case for a greater emphasis on resistance training. BMC Public Health 2017;17:300 10.1186/s12889-017-4209-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhubing S, Zhenyi W. A correlation research of university students’ lifestyle behaviors and psychological sub-health in Guizhou. J Nanjing Univ Nat Sci 2014;13:155–60. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Espinosa A, Kadić-Maglajlić S. The role of health consciousness, patient-physician trust, and perceived physician's emotional appraisal on medical adherence. Health Educ Behav 2019;46:991–1000. 10.1177/1090198119859407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sheeran P, Maki A, Montanaro E, et al. The impact of changing attitudes, norms, and self-efficacy on health-related intentions and behavior: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol 2016;35:1178–88. 10.1037/hea0000387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kaskutas LA, Greenfield TK. The role of health consciousness in predicting attention to health warning messages. Am J Health Promot 1997;11:186–93. 10.4278/0890-1171-11.3.186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.