Abstract

Objective

To compare the effectiveness of the mobile e-Tabac Info Service (e-TIS) application (app) for helping adult smokers quit smoking with current practices.

Design

Pragmatic randomised controlled trial with a 1-year follow-up (2017–2018).

Setting

France, population-wide level.

Participants

2806 adult smokers who wished to quit smoking were recruited via the website of the French National Mandatory Health Insurance fund. Of them, 1400 were randomised to the e-TIS app arm and 1406 were randomised to the current practices arm (control).

Intervention

The app involved personalised interactive contacts that included questionnaires, advice, activities and text messages. All contacts were individually tailored and based on each smoker’s progress.

In the control group, recommended practices for quitting smoking were described on a non-interactive website.

Primary and secondary outcomes measures

The primary outcome was 7-day point prevalence abstinence (PPA) at 6 months. The secondary outcomes included continuous abstinence rates at 6 and 12 months, minimum 24-hour point abstinence at 3 months, minimum 30-day point abstinence at 12 months and number and duration of quit attempts.

Results

There was no difference between the e-TIS and control arms for the primary outcome (12.6% vs 13.7% for 7-day PPA at 6 months, p=0.3949, intention-to-treat analysis). However, e-TIS participants with high levels of exposure to the app, which was defined by the completion of at least eight activities or questionnaires, showed higher rates of smoking cessation than the control participants (17.6% vs 12.9% for 7-day PPA at 6 months, p=0.0169, per-protocol analysis).

Conclusion

Use of the e-TIS app was not associated with a higher rate of smoking cessation. However, high level of exposure to the e-TIS app may have been more effective than current practices.

Trial registration number

Keywords: public health, preventive medicine, clinical trials

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This was a large, national, randomised controlled trial.

This was a pragmatic trial that was conducted under ‘real-life’ conditions.

According to guidelines, the primary outcome was point prevalence abstinence at 6 months.

The main limitation of the study is the high attrition rate.

Findings may have been influenced by contamination between arms due to the unrestricted availability of the e-Tabac Info Service from app stores during the trial.

Introduction

Smoking remains a leading risk factor for early death and disability.1 Thus, there is a need to strengthen support for smoking cessation. In this context, mobile phone applications (apps) are increasingly used and have several advantages in terms of their inexpensiveness, scalability to large populations, interactivity, ability to be used anywhere at any time, to be tailored to individual users, to distract smokers from cravings and to link users with social support.2 Although several apps for smoking cessation are available only a few are theory or evidence based.3 4 Nonetheless, these health apps appear to be used more effectively and for longer periods of time when they offer support that extends beyond motivation maintenance and contributions to self-knowledge.5

In France, a theory-based app for smoking cessation, the e-intervention Tabac Info Service (e-TIS), has been developed by Santé publique France and the Caisse nationale d’assurance maladie.6 This app was designed to provide support to smokers who wish to quit, including those who are not currently involved in a quit attempt, and was based on the effectiveness criteria of online programmes7 and psychosocial and behavioural change theories.8–12 The e-TIS app provides tailored activities, self-report exercises, tips, social and/or psychological support, reassurance and motivational text messages that are adapted to the individual characteristics of the user.13 The present study evaluated the effectiveness of the theory-based smoking cessation e-TIS app in a pragmatic randomised controlled trial conducted in France on a population-wide level.

Methods

This manuscript was written in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials Statement and the EHEALTH checklist.14

Study design

The protocol was previously registered (NCT02841683) and published.13 Participants were randomly assigned (1:1) to either the intervention arm (invitation to use the e-TIS app) or the control arm (current practices for smoking cessation described on a non-interactive website from the French National Mandatory Health Insurance (ameli.fr)). The current practices were based on the guidelines of the Haute Autorité de Santé.15 All participants were recruited between February 2017 and April 2018, then followed up over the subsequent 1-year period.

All participants consented to inclusion in the study and an automated randomisation procedure was carried out following the receipt of all inclusion data. A minimisation software package was employed to reduce the risk of unmatched groups and to stratify the participants based on age and sex, using the following parameters: study arm (e-TIS and control, allocated 50/50), sex (male/female) and age (≤45 years or >45 years).

Study population and sample

When visiting their personal account on the French Mandatory National Health Insurance website, users were invited to participate in the present study via a banner. Users who clicked on the banner were presented with an information sheet, which included a section where they could provide informed consent. The consent form contained the inclusion questionnaire, with the following criteria: (1) adult smoker; (2) completion of the online consent form; (3) agreement to participate in the study; (4) possession of a mobile phone using an iOS or Android system; (5) willingness to use the app; and (6) attempt or consideration of an attempt to quit smoking. If the user provided consent to be enrolled in the study, they were sent an email with a confirmation link. When the participants clicked the confirmation link, they were randomised and invited to fill in the entry questionnaire (T0) for the study.

Intervention arm: e-TIS app

Participants assigned to the intervention arm were invited to download the e-TIS app. In accordance with the relapse prevention model,16 17 the e-TIS app is tailored to each individual smoker based on feedback. Furthermore, the support process in the e-TIS is based on the efficacy criteria of online programmes, which include the frequency and intensity of contacts, short messages, interactivity, appeal, personalisation, credibility of content and sharing functions,7 as well as various theoretical models that are used for withdrawal treatments.8–12 18

The e-TIS app involves personalised interactive (push) contacts that include questionnaires, activities and text messages which are available via mobile phone, the website platform and tablets. In total, the intervention consists of 16 different activities, eight position questionnaires (to adapt the app content to the evolution of one’s willingness to quit or attempt to quit), and a set of roughly 170 email or push-app text messages/notifications with distinct purposes. All contacts are tailored to the answers on the eight position questionnaires and an individual’s progress through the four modules of the app. Each participant began the process within a module that was adapted to his/her individual stage regarding tobacco status. The content has been described in detail elsewhere.13 The present study evaluated e-TIS V.2.0.

Control arm: current practices

Participants assigned to the control arm were invited to visit a pre-existing website page that listed smoking cessation resources that are readily available in France and recommended by the Haute Autorité de Santé.15

Outcomes and other data

The primary outcome in the present study was point prevalence abstinence (PPA) at the 6-month follow-up assessment. The PPA for smoking is a minimum of 7 days.19 In general, the PPA is considered to be the most appropriate measure for evaluating abstinence in intervention evaluation studies.20

Because a large number of participants were lost to follow-up during the study, and due to the need to limit the amount of missing data, the original study protocol was modified as follows before the blinding was lifted: (1) for participants with information regarding smoking status at 12 months but not at 6 months, the 12-month smoking status was used to replace the missing data regarding smoking status at 6 months; (2) for participants with information regarding smoking status at 3 months but not at 6 or 12 months, the 3-month smoking status was used to replace the missing data regarding smoking status at 6 months. Additionally, at the 6-month follow-up assessment, participants with missing data were phoned and reminded of the study. This recalculated criterion was used as the primary outcome. Sensitivity analyses were performed with the original criterion (ie, without imputations for missing data).

Based on previous data and recommendations,2 7 20 21 the secondary outcomes in the present study included continuous abstinence at 6 months, continuous abstinence at 12 months, minimum 24-hour point abstinence at 3 months, minimum 30-day point abstinence at 12 months and number and duration of quit attempts. To further characterise tobacco consumption, the present study also collected data associated with the dependency and determinants of abstinence, described elsewhere.13

Data collection

Data were collected via internet-based self-report questionnaires at inclusion (technical variables), study initiation (initial self-reporting questionnaire) and at 3, 6 and 12 months (three follow-up self-report questionnaires). Application usage data were extracted from the application database and a match with the study data measured whether or not the persons included in both arms used the application.

Statistical analysis

Sample size calculation

The required sample size was calculated based on the hypothesis of a 10% abstinence rate at 6-month follow-up in the control group.22 Given this rate, sample sizes of 1500 participants per group were necessary to show a minimum OR of 1.5 with a power of 90% (α=0.05, bilateral test); thus, a total sample size of 3000 individuals was necessary.23

Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were performed for the intention-to-treat (ITT), per-protocol (PP) and as-treated (AT) populations. The ITT analysis included all participants in the arms to which they were randomised, regardless of adherence to the prescribed intervention. For the PP and AT analyses, exposure to the application was defined as the completion of at least one activity or questionnaire through the app. For the PP analysis, participants in the intervention arm were defined as those randomised to that arm who completed at least one activity or questionnaire. Participants in the control arm were defined as those randomised to that arm who did not complete any activities or questionnaires through the app. For the AT analysis, participants who completed at least one activity or questionnaire through the app, independent of their allocation arm, were regarded as those exposed to the intervention. Participants who did not complete any activities or questionnaires through the application, independent of their allocation arm, were regarded as non-exposed to the intervention.

For the main analysis, participants lost to follow-up (those who did not answer the questionnaires) were defined as smokers, as previously recommended,7 21 24 whereas the secondary analysis only considered participants who were not lost to follow-up. Multivariate analyses, adjusted for baseline characteristics, were performed in the PP and AT populations. To compare the effects of the e-TIS app on smoking cessation in terms of low versus high levels of e-TIS use, participants were categorised based on median use in the present study: that is, the completion of eight activities or questionnaires through the app.

Some subgroup analyses were conducted as defined in the study protocol.13 Other subgroup analyses were added to the initial protocol (before the blinding was lifted): tobacco status at inclusion and plans to have or adopt a child in the following year. Sensitivity analyses were performed using only data from participants with a smoking status at 6 months, without data recovery based on 3-month and/or 12-month smoking status. All statistical analyses were performed in 2019 using SAS V.9.4 Software (SAS Institute).

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination of our research.

Results

Recruitment and baseline characteristics

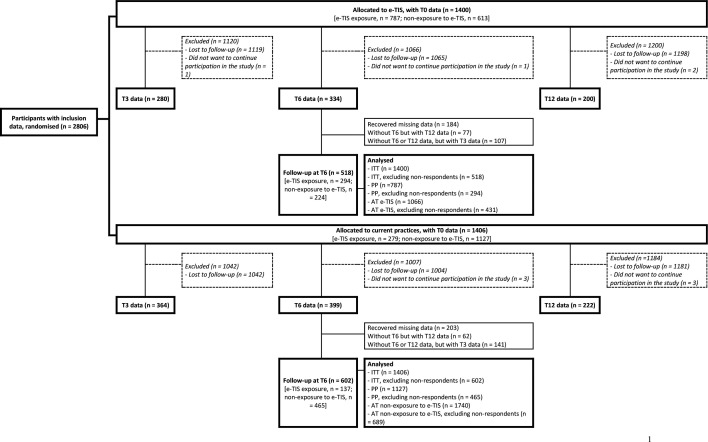

Figure 1 displays the flow chart of the randomisation and follow-up procedures. A total of 2806 participants with inclusion data were randomised for the present study; of these, 1400 were allocated to the e-TIS arm and 1406 were allocated to the control arm. Based on the recovery of missing data, 518 and 602 participants were followed up at 6 months in the e-TIS and control arms, respectively. Figure 1 shows contamination between the groups. Specifically, of the 1400 participants in the e-TIS arm, 787 were exposed to the app, whereas 613 participants were considered to not have been exposed to the app; the 3-month and 6-month usage rates for the app were 10.7% and 5.7%, respectively. Of the 1406 participants in the control arm, 1127 participants were not exposed to the app, whereas 279 participants were considered to have been exposed to the app. The ITT, PP and AT populations used to assess the primary outcome at 6 months in each arm are displayed in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Diagram depicting the flow of participants in the study (n=2806). AT, as-treated; e-TIS, e-intervention Tabac Info Service; ITT, intention-to-treat; PP, per-protocol.

The baseline characteristics of the participants and their exposure levels to the e-TIS app are presented in online supplemental table 1. Of the total participants, most were women, aged 45 years or younger, and current smokers. There were no significant differences between the groups at baseline.

bmjopen-2020-039515supp001.pdf (385.8KB, pdf)

Primary outcome

There were no differences in PPA at 6 months between the e-TIS and control arms in the ITT, PP and AT populations (table 1). When considering only respondents in the total population, 32.9% and 32.4% of participants were quitters in the ITT/AT and PP populations, respectively. When considering non-respondents as smokers, 13.1% and 12.9% of the participants, respectively, were quitters. There were no significant differences in the primary outcome between participants exposed to the e-TIS and participants not exposed to e-TIS in the PP and AT populations (table 2).

Table 1.

Between-group differences in the primary outcome (minimum of 7-day point prevalence abstinence (PPA) at 6 months) in the intention-to-treat (ITT), per-protocol (PP) and as-treated (AT) analyses

| ITT population | |||||||

| Total n=2806 |

e-TIS n=1400 (49.9%) |

Control n=1406 (50.1%) |

P value* | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Minimum of 7-day PPA at 6 months (n=1120)† | 0.4593 | ||||||

| Smokers | 752 | 67.1 | 342 | 66 | 410 | 68.1 | |

| Quitters | 368 | 32.9 | 176 | 34 | 192 | 31.9 | |

| Minimum of 7-day PPA at 6 months (n=2806)‡ | 0.3949 | ||||||

| Smokers | 2438 | 86.9 | 1224 | 87.4 | 1214 | 86.3 | |

| Quitters | 368 | 13.1 | 176 | 12.6 | 192 | 13.7 | |

| PP population | |||||||

| Total n=1914 |

e-TIS n=787 (41.1%) |

Control n=1127 (58.9%) |

P value* | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Minimum of 7-day PPA at 6 months (n=759)† | 0.2196 | ||||||

| Smokers | 513 | 67.6 | 191 | 65 | 322 | 69.2 | |

| Quitters | 246 | 32.4 | 103 | 35 | 143 | 30.8 | |

| Minimum of 7-day PPA at 6 months (n=1914)‡ | 0.7974 | ||||||

| Smokers | 1668 | 87.1 | 684 | 86.9 | 984 | 87.3 | |

| Quitters | 246 | 12.9 | 103 | 13.1 | 143 | 12.7 | |

| AT population | |||||||

| Total n=2806 |

e-TIS n=1066 (38.0%) |

Non-exposure to e-TIS n=1740 (62.0%) |

P value* | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Minimum of 7-day PPA at 6 months (n=1120)† | 0.1745 | ||||||

| Smokers | 752 | 67.1 | 279 | 64.7 | 473 | 68.7 | |

| Quitters | 368 | 32.9 | 152 | 35.3 | 216 | 31.3 | |

| Minimum of 7-day PPA at 6 months (n=2806)‡ | 0.1599 | ||||||

| Smokers | 2438 | 86.9 | 914 | 85.7 | 1524 | 87.6 | |

| Quitters | 368 | 13.1 | 152 | 14.3 | 216 | 12.4 | |

*χ2 test.

†Only respondents considered.

‡Non-respondents considered as smokers.

e-TIS, e-intervention Tabac Info Service.

Table 2.

Minimum of 7-day point prevalence abstinence (PPA) in the per-protocol (PP) and as-treated (AT) populations (multivariate analysis)

| Minimum 7-day PPA at 6 months | Multivariate regression* | ||||||

| n | Quitters | % | ORs | 95% CI | P value | ||

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| PP population | |||||||

| Only considering respondents (n=743/759†)‡ | 0.214 | ||||||

| Control | 453 | 138 | 30.5 | 1 | |||

| e-TIS exposure | 290 | 102 | 35.2 | 1.22 | 0.89 | 1.67 | |

| Considering non-respondents as smokers (n=1831/1914†)§ | 0.6689 | ||||||

| Non-exposure to e-TIS | 1080 | 132 | 12.2 | 1 | |||

| e-TIS exposure | 751 | 99 | 13.2 | 1.06 | 0.8 | 1.41 | |

| AT population | |||||||

| Only considering respondents (n=1095/11202†)‡ | 0.1882 | ||||||

| Non-exposure to e-TIS | 671 | 210 | 31.3 | 1 | |||

| e-TIS exposure | 424 | 150 | 35.4 | 1.19 | 0.92 | 1.54 | |

| Considering non-respondents as smokers (n=2679/28062)§ | 0.1449 | ||||||

| Non-exposure to e-TIS | 1660 | 202 | 12.2 | 1 | |||

| e-TIS exposure | 1019 | 146 | 14.3 | 1.19 | 0.94 | 1.49 | |

*Adjusted for baseline characteristics, with the exception of tobacco status at inclusion. The stepwise variable selection method was used with an input threshold in the model at 0.2 and an output threshold in the model at 0.05. Only factors with a significant association with the 0.2 threshold in the bivariate model were candidates in the multivariate model.

†Due to missing data regarding the variables considered in the multivariate model.

‡Retained variables: expecting a child.

§Retained variables: family situation, level of education, treatment for cardiovascular or respiratory diseases.

e-TIS, e-intervention Tabac Info Service.

Secondary outcomes

There were no significant differences in any of the secondary outcomes between the e-TIS and control arms in the ITT population (online supplemental table 2).

High level of e-TIS use

Table 3 presents the group differences in the primary outcome in the PP and AT populations after considering exposure to the e-TIS. In the PP population when considering non-respondents as smokers, 17.6% of participants in the e-TIS high exposure group were quitters, compared with 12.9% in the control group (p=0.0169). In the AT population when considering non-respondents as smokers, 18.2% of the participants in the e-TIS high exposure group were quitters, compared with 11.8% in the other group (p<0.0001).

Table 3.

Between-group differences in the primary outcome in the per-protocol (PP) and as-treated (AT) populations, which considered exposure to be the completion of at least eight activities or questionnaires through the application

| PP population | |||||||

| Total n=1652 |

e-TIS exposure* n=409 (24.8%) |

Control n=1243 (75.2%) |

P value* | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Minimum 7-day PPA at 6 months (n=704)‡ | 0.0139 | ||||||

| Smokers | 472 | 67 | 106 | 59.6 | 366 | 69.6 | |

| Quitters | 232 | 33 | 72 | 40.4 | 160 | 30.4 | |

| Minimum 7-day PPA at 6 months (n=1652)‡ | 0.0169 | ||||||

| Smokers | 1420 | 86 | 337 | 82.4 | 1083 | 87.1 | |

| Quitters | 232 | 14 | 72 | 17.6 | 160 | 12.9 | |

| AT population | |||||||

| Total n=2806 |

e-TIS exposure† n=572 (20.4%) |

Non-exposure to e-TIS n=2234 (79.60%) |

P value* | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Minimum 7-day PPA at 6 months (n=1120)‡ | 0.0018 | ||||||

| Smokers | 752 | 67.1 | 150 | 59.1 | 602 | 69.5 | |

| Quitters | 368 | 32.9 | 104 | 40.9 | 264 | 30.5 | |

| Minimum 7-day PPA at 6 months (n=2806)§ | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Smokers | 2438 | 86.9 | 468 | 81.8 | 1970 | 88.2 | |

| Quitters | 368 | 13.1 | 104 | 18.2 | 264 | 11.8 | |

*χ2 test.

†Completed at least eight activities or questionnaires through the application.

‡Only respondents considered.

§Non-respondents considered as smokers.

e-TIS, e-intervention Tabac Info Service; PPA, point prevalence abstinence.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses were performed using participants with data at 6 months (no recovery data were used); online supplemental figure 1 presents the corresponding diagram flow. These results were similar to those of the main analysis (online supplemental table 3).

Subgroup analyses

Online supplementary figure 2 illustrates the subgroup analyses performed using the ITT population, which considered non-respondents as smokers. There were no differences in the minimum 7-day PPA between the e-TIS and control arms in any of the identified subgroups.

Similar results were obtained in the ITT population when only respondents were considered, as well as in the PP and AT populations (both cases: non-respondents were considered as smokers and only considering respondents) with the following exceptions (online supplemental table 4 a–r). In the AT population and among smokers at inclusion, quitters were overrepresented among the e-TIS participants, relative to participants who were not exposed to the e-TIS. Therefore, when considering non-respondents as smokers, 11.2% (n=80) of the e-TIS participants were quitters, compared with 8.0% (n=93) of the participants who were not exposed to the e-TIS (p=0.0193). Similar results were obtained when analyses were performed using participants with no recovery data at 6 months in the ITT, PP and AT populations.

Discussion

The present study evaluated the effectiveness of the theory-based smoking cessation e-TIS app. This study was a randomised controlled trial under pragmatic conditions, which enabled evaluation of the effectiveness of e-TIS in real-life situations. The pragmatic situation is particularly relevant for behaviour change interventions.25 Indeed, for these interventions, determinants of choice to participate in the trial may also be determinants of outcome (eg, motivation). This type of intervention may thus have more favourable results within a trial than in a real-life situation.13 It is to limit this major bias that we wanted the inclusion procedure to be the lightest possible in order to recruit smokers who were not selected because of their high motivation to participate in a trial. The major disadvantage of this methodological choice is the high attrition rate we observed. Although a high rate of attrition is quite common in investigations of mHealth tools,26 27 ours is particularly high.

Moreover, the present findings may have been influenced by high levels of contamination between the study arms due to the unrestricted availability of the e-TIS from app stores during the trial. Our results according to the three types of analysis (ie, ITT, PP, AT) are consistent, which is in favour of the robustness of our results in this regard.

The primary outcome was PPA at 6 months. This is the recommended duration. It is justified by the high rate of short-term relapse during smoking cessation.24 PPA is considered to be the most appropriate measure for evaluating abstinence in intervention evaluation studies.20 The continuous abstinence, recommended in clinical trials,24 is not relevant in this context because a planned cessation date was not a criterion for inclusion and patients could stop smoking at any time during follow-up. However, we have retained it as a secondary outcome and results remained unchanged with this outcome. Similarly, our imputation procedures to account for missing data did not change results as shown in sensitivity analyses.

Because the trial is not conclusive given its limitations and because the present results may be explained by multiple hypotheses, the next step of our study will consist of the performance of a process evaluation28 using behavioural change techniques taxonomy,29 30 in order to better understand the e-TIS mechanisms and conditions of efficacy. These conditions relate to the participants; the different components of e-TIS used by the participants; the psychological, social and environmental factors possibly affecting the participants during the study.13

As expected, the participants were mostly young and had a high level of education,31 which is consistent with the nature of the digital intervention.32 Furthermore, more women agreed to participate. Similar rates of female participants were observed in the trials reviewed by Whittaker et al2 that employed similar methods of inclusion.33–35

The present study also revealed a high rate of smoking cessation among all participants. Notably, the rates observed in this study were higher than those in a previous French trial that evaluated the previous TIS modality, which employed email coaching (32.9% in present study vs 24.7%).36 When considering non-respondents as smokers, 12.6% and 13.7% of participants in the e-TIS and control arms, respectively, were quitters. Previous studies have reported that 9% of intervention group populations and 5%–6% of control group populations are quitters.2 It is important to note that the control arm in the present study may not have been considered a true control arm; importantly, the original e-TIS protocol submitted to the ethical committee planned to compare the e-TIS arm with a control arm (no intervention other than standard practices). However, the committee suggested that the control participants be exposed to best evidence-based practices currently in use.15 Thus, the Quitting page of the French National Mandatory Health Insurance website (Ameli) was suggested to the control participants, and some of these participants may have used the various smoking cessation resources which are all considered to be effective. For example, at 6 months, 36.4% of participants in the control arm had used nicotine replacement therapies within the previous 3 months.

The present study also revealed a lack of differences between the e-TIS and control arms in the ITT, PP and AT populations. In a Cochrane systematic review conducted in 2014, Whittaker et al2 concluded that mobile phone-based smoking cessation interventions had a beneficial impact on 6-month outcomes (relative risk: 1.67, 95% CI 1.46 to 1.90; I2=59%; 12 studies included). However, most studies included in that review employed short message service text messaging-based interventions, rather than complex apps; notably, more complex apps use text messaging and other forms of contact. Therefore, direct comparisons between these results may be inappropriate.

Similar to the findings of recent studies that investigated the effectiveness of complex apps,37 38 the present results showed that the results in the intervention and control arms did not differ at 6 months. Baskerville et al37 compared the effectiveness of an evidence-informed self-help guide with a non-intervention arm, which may explain the absence of differences in both arms, and Garrison et al.38 evaluated a mindfulness training app. Although there were no group differences in smoking abstinence at 6 months, the intervention app reduced the associations between craving and smoking, compared with the control app. In contrast, BinDhim et al39 reported that individuals exposed to a smartphone-based decision aid were significantly more likely to exhibit continuous abstinence at 6 months than those exposed to an information-only app. In that study, the intervention app was required to display information regarding quitting options, whereas the control app was not required to display this information.

Furthermore, Brown et al22 found that the StopAdvisor app was more effective than an information-only website for helping participants with a low socioeconomic status stop smoking; it is important to note that this study was designed with sufficient power to separately assess effectiveness within each socioeconomic status subsample. In the present study, there were no differences according to socioeconomic status, based on the reported level of education. Additionally, in the StopAdvisor study, the authors noted that the control website was used less regularly than the StopAdvisor website in terms of logins, page views and time spent on the website. At the 6-month follow-up assessment in the present study, several of the control participants reported that they had been using other forms of smoking cessation support in the three previous months (eg, use of nicotine replacement therapies and/or consultation with a healthcare professional). This could explain the high smoking cessation rate in the present control group (13.7%) versus that in the StopAdvisor study (10%).

Moreover, the effects of health apps remain controversial because they are influenced by numerous factors related to the app components, characteristics of the users (eg, motivation, previous attempts to quit, and uniformity) and the environment of the participant (eg, social support). As a result, some authors have advocated for the use of process evaluations to complement the effectiveness evaluations when assessing this ‘black box’.5 40 41

The present study also found that the numbers of quitters in the PP and AT populations at 6 months were higher among participants exposed to the e-TIS, compared with those not exposed to the app, when e-TIS exposure was defined as the completion of at least eight activities and/or questionnaires (ie, the median exposure). It is tempting to conclude that the e-TIS was effective if used intensively, which would be consistent with previous results on the relationship between use frequency and efficacy.5 42 However, it is likely that the most motivated participants used the app for a longer time; this motivation, rather than the duration or frequency of use, would have improved the results. This idea is consistent with the findings of prior studies, in which the most motivated people were those who used the apps more frequently.5 43 In the same way, it is possible that it is a feedback loop between engagement and effectiveness.44 However, in our population, there is no relationship between motivation at inclusion and subsequent use (data not shown), which is an argument for the effectiveness of exposure to the application. That remains to be confirmed.

Conclusions

In the present study, use of the e-TIS app was not associated with a higher rate of smoking cessation. However, high level of exposure to the e-TIS app may have been more effective than current practices.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: LC and FA managed the scientific coordination of the study. CB coordinated the data management and statistical analysis. AL performed the statistical analyses. CB, PB, ALL, AP and PA contributed to the design and to the interpretation of the results. AA, LC and FA wrote the draft. All authors reviewed and contributed to the article and validated its final version.

Funding: This work was supported by the Caisse nationale d’assurance maladie (Award/Grant number is not applicable)

Competing interests: ALL reports a grant and conference honoraria from Pfizer, as well as a conference honorarium from J&J that was outside the scope of the submitted work. The English in this document has been checked by at least two professional editors, both native speakers of English.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: All participants were required to provide informed consent prior to inclusion in the study and were informed that they could refuse and drop out at any time. The study protocol was reviewed by the Ethical and Deontological Institutional Review Board of the Institut National de Veille Sanitaire on 18 April 2016. All recommendations from the committee were integrated into the amended version of the protocol.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request.

Supplemental material This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1.GBD 2015 Tobacco Collaborators Smoking prevalence and attributable disease burden in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis from the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet 2017;389:1885–906. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30819-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whittaker R, McRobbie H, Bullen C, et al. . Mobile phone-based interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;4:CD006611. 10.1002/14651858.CD006611.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haskins BL, Lesperance D, Gibbons P, et al. . A systematic review of smartphone applications for smoking cessation. Transl Behav Med 2017;7:292–9. 10.1007/s13142-017-0492-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ubhi HK, Kotz D, Michie S, et al. . Comparative analysis of smoking cessation smartphone applications available in 2012 versus 2014. Addict Behav 2016;58:175–81. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.02.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aromatario O, Van Hoye A, Vuillemin A, et al. . How do mobile health applications support behaviour changes? A scoping review of mobile health applications relating to physical activity and eating behaviours. Public Health 2019;175:8–18. 10.1016/j.puhe.2019.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tabac Info Service Webpage for e-TIS intervention downloading. Available: https://www.tabac-info-service.fr/J-arrete-de-fumer/Je-telecharge-l-ecoaching [Accessed 16 Sep 2019].

- 7.Civljak M, Stead LF, Hartmann-Boyce J, et al. . Internet-Based interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;7:CD007078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages of change in the modification of problem behaviors. Prog Behav Modif 1992;28:183–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bandura A. Human agency in social cognitive theory. Am Psychol 1989;44:1175–84. 10.1037/0003-066X.44.9.1175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: preparing people for change. Guildford Press, 2002: 456 p.. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller WR, Rose GS. Toward a theory of motivational interviewing. Am Psychol 2009;64:527–37. 10.1037/a0016830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Janis IL, Mann L. Emergency decision making: a theoretical analysis of responses to disaster warnings. J Human Stress 1977;3:35–48. 10.1080/0097840X.1977.9936085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cambon L, Bergman P, Le Faou A, et al. . Study protocol for a pragmatic randomised controlled trial evaluating efficacy of a smoking cessation e-'Tabac Info service': ee-TIS trial. BMJ Open 2017;7:e013604. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eysenbach G, Group C-E, CONSORT-EHEALTH Group . CONSORT-EHEALTH: improving and standardizing evaluation reports of web-based and mobile health interventions. J Med Internet Res 2011;13:e126. 10.2196/jmir.1923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haute Autorité de Santé Arrêt de la consommation de tabac: du dépistage individuel au maintien de l’abstinence ne premier recours. Recommandations, 2014. Available: https://www.has-sante.fr/portail/upload/docs/application/pdf/2014-11/recommandations_-_arret_de_la_consommation_de_tabac_octobre_2014_2014-11-17_14-13-23_985.pdf [Accessed 7 Feb 2017].

- 16.Marlatt GA, Gordon J. Determinants of relapse: implications for the maintenance of behavior change. in: behavioral medicine: changing health lifestyles. New York: Brunner/Mazel. Davidson PO, Davidson SM, 1980: 410–52. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hendershot CS, Witkiewitz K, George WH, et al. . Relapse prevention for addictive behaviors. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 2011;6:17. 10.1186/1747-597X-6-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beauregard L, Dumont S. La mesure Du soutien social. Serv Soc 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Velicer WF, Prochaska JO, Rossi JS, et al. . Assessing outcome in smoking cessation studies. Psychol Bull 1992;111:23–41. 10.1037/0033-2909.111.1.23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hughes JR, Keely JP, Niaura RS, et al. . Measures of abstinence in clinical trials: issues and recommendations. Nicotine Tob Res 2003;5:13–26. 10.1080/1462220031000070552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.European Medicines Agency Guideline on treatment of smoking, 2009. Available: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2009/09/WC500003509.pdf [Accessed 7 Feb 2018].

- 22.Brown J, Michie S, Geraghty AWA, et al. . Internet-Based intervention for smoking cessation (StopAdvisor) in people with low and high socioeconomic status: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med 2014;2:997–1006. 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70195-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dupont WD, Plummer WD. Power and sample size calculations. A review and computer program. Control Clin Trials 1990;11:116–28. 10.1016/0197-2456(90)90005-m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.West R, Hajek P, Stead L, et al. . Outcome criteria in smoking cessation trials: proposal for a common standard. Addiction 2005;100:299–303. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00995.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Troxel AB, Asch DA, Volpp KG. Statistical issues in pragmatic trials of behavioral economic interventions. Clin Trials 2016;13:478–83. 10.1177/1740774516654862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gordon JS, Armin J, D Hingle M, et al. . Development and evaluation of the see me smoke-free multi-behavioral mHealth APP for women smokers. Transl Behav Med 2017;7:172–84. 10.1007/s13142-017-0463-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pellegrini CA, Verba SD, Otto AD, et al. . The comparison of a technology-based system and an in-person behavioral weight loss intervention. Obesity 2012;20:356–63. 10.1038/oby.2011.13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. . Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008;337:a1655. 10.1136/bmj.a1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Michie S, Wood CE, Johnston M, et al. . Behaviour change techniques: the development and evaluation of a taxonomic method for reporting and describing behaviour change interventions (a suite of five studies involving consensus methods, randomised controlled trials and analysis of qualitative data). Health Technol Assess 2015;19:1–188. 10.3310/hta19990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, et al. . The behavior change technique taxonomy (V1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med 2013;46:81–95. 10.1007/s12160-013-9486-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guignard R, Richard J, Pasquereau A, et al. . Tentatives d’arrêt du tabac au dernier trimestre 2016 et lien avec Mois sans tabac : premiers résultats observés dans le Baromètre santé. 2017. Bull Epidémiol Hebd 2018:298–303. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krebs P, Duncan DT. Health APP use among US mobile phone owners: a national survey. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2015;3:e101. 10.2196/mhealth.4924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Balmford J, Borland R, Benda P, et al. . Factors associated with use of automated smoking cessation interventions: findings from the eQuit study. Health Educ Res 2013;28:288–99. 10.1093/her/cys104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abroms LC, Boal AL, Simmens SJ, et al. . A randomized trial of Text2Quit: a text messaging program for smoking cessation. Am J Prev Med 2014;47:242–50. 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bock B, Heron K, Jennings E, et al. . A text message delivered smoking cessation intervention: the initial trial of TXT-2-Quit: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2013;1:e17. 10.2196/mhealth.2522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nguyen Thanh V, Guignard R, Lancrenon S, et al. . Effectiveness of a fully automated Internet-based smoking cessation program: a randomized controlled trial (stamp). Nicotine Tob Res 2019;21:163–72. 10.1093/ntr/nty016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baskerville NB, Struik LL, Guindon GE, et al. . Effect of a mobile phone intervention on quitting smoking in a young adult population of smokers: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018;6:e10893. 10.2196/10893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garrison KA, Pal P, O’Malley SS, et al. . Craving to quit: a randomized controlled trial of smartphone app-based mindfulness training for smoking cessation. Nicotine Tob Res Off J Soc Res Nicotine Tob 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.BinDhim NF, McGeechan K, Trevena L. Smartphone Smoking Cessation Application (SSC App) trial: a multicountry double-blind automated randomised controlled trial of a smoking cessation decision-aid 'app'. BMJ Open 2018;8:e017105. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cambon L. Health smart devices and applications…towards a new model of prevention? Eur J Public Health 2017;27:390–1. 10.1093/eurpub/ckx019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Petit A, Cambon L. Exploratory study of the implications of research on the use of smart connected devices for prevention: a scoping review. BMC Public Health 2016;16:552. 10.1186/s12889-016-3225-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vaghefi I, Tulu B. The continued use of mobile health Apps: insights from a longitudinal study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019;7:e12983. 10.2196/12983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brown J, Michie S, Raupach T, et al. . Prevalence and characteristics of smokers interested in Internet-based smoking cessation interventions: cross-sectional findings from a national household survey. J Med Internet Res 2013;15:e50. 10.2196/jmir.2342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perski O, Blandford A, West R, et al. . Conceptualising engagement with digital behaviour change interventions: a systematic review using principles from critical interpretive synthesis. Transl Behav Med 2017;7:254–67. 10.1007/s13142-016-0453-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-039515supp001.pdf (385.8KB, pdf)