Abstract

Objective

This study is concerned with helping to improve the health and care of newborn babies in Bangladesh by exploring adverse maternal circumstances and assessing whether these are contributing towards low birth weight (LBW) in neonates.

Study designs and settings

Data were drawn and analysed from the Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey, 2014. Any association between LBW and adverse maternal circumstances were assessed using a Chi-square test with determinants of LBW identified by multivariate logistic regression analysis.

Participants

The study is based on 4728 children aged below 5 years and born to women from selected households.

Results

The rate of LBW was around 19.9% (199 per 1000 live births) with the highest level found in the Sylhet region (26.2%). The rate was even higher in rural areas (20.8%) and among illiterate mothers (26.6%). Several adverse maternal circumstances of the women included in the survey were found to be significant for increasing the likelihood of giving birth to LBW babies. These circumstances included the women being underweight (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) 1.26, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.49); having unwanted births (AOR 1.22, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.44); had previous pregnancies terminated (AOR 1.28, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.57); were victims of intimate partner violence (AOR 1.23, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.45) and taking antenatal care <4 times (AOR 1.23, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.48). Other important risk factors that were revealed included age at birth <18 years (AOR 1.42, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.83) and intervals between the number of births <24 months (AOR 1.25, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.55). When taking multiple fertility behaviours together such as, the ages of the women at birth (<18 years with interval <24 months (AOR 1.26, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.57) and birth order (>3 with interval <24 months (AOR 1.68, 95% CI 1.18 to 2.37), then the risk of having LBW babies significantly increased.

Conclusion

This study finds that adverse maternal circumstances combined with high-risk fertility behaviours are significantly associated with LBW in neonates. This situation could severely impede progress in Bangladesh towards achieving the sustainable development goal concerned with the healthcare of newborns.

Keywords: neonatology, community child health, nutrition

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Analysing the nationally representative data set helped to provide a wide picture of society in Bangladesh and provided more reliable results.

A limitation of the data set occurred where the low birth weight was recorded based on the perceptions of the mothers as to the size of their children at birth instead of their actual birth weights due to the unavailability of official data.

The study outcome and predictors were based on self-reporting and recall bias is commonly found with this type of data collection procedure.

The use of secondary datasets limited our freedom to select variables for the analysis and perform model adjustment.

Introduction

Low birth weight (LBW) is a critical global concern particularly in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs).1 2 A newborn weighing less than 2.5 kg (5.5 pounds) is classed as an LBW baby.3 It is one of the key underlying contributors for potentially increasing the risk of infant mortality, susceptibility to severe childhood illness1 4 and malnutrition,5 and can impede the future cognitive development of the baby.6 Unfortunately, around 20 million (15.5%) babies worldwide are born each year with LBW with around 96% of these in LMICs7 like Bangladesh. Regional statistics illustrate that the global burden of LBW is severely skewed towards South Asia that has the highest prevalence (28%) followed by sub-Saharan African countries (13%), then the Caribbean and Latin America (9%) and the Pacific and Eastern Asia (6%).3 The National Low Birth Weight Survey of Bangladesh reported that the prevalence of LBW decreased from around 36% in 2004 to 22.6% in 20151 8 providing an indication of improvement.

Previous studies confirm that LBW contributes significantly to neonatal and infant mortality7 with 60%–80% of neonatal deaths worldwide occurring within 28 days of life.7 Infants with a significant LBW (<1500 g) are around 20 times more likely to die in infancy than those born within normal weight limits.9 LBW is also accelerating the risk of mortality in later childhood and adolescence due to congenital malformations and perinatal factors.9 Further adverse health and growth problems associated with LBW and identified in other studies include chronic disease such as childhood asthma,10 attention-deficit or hyperactivity disorder,11 post-natal growth failure,12 stunting, wasting and being underweight.13 These negative health aspects can extend into adulthood and increase the risk of developing chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease14 15 and respiratory diseases.15 16 The importance of preventing LBW therefore is vital for reducing the mortality and morbidity risk in childhood and adulthood.

Worldwide efforts have been made to reveal the aetiology and identify the risk factors of LBW but these can be complex and vary among regions. Previous research findings from developed and developing regions suggest that potential risk factors for LBW include a history of premature delivery,17 maternal younger age (<18 years) and advanced age (>34 years) at childbirth,17 18 insufficient prenatal care,1 18 19 underweight mother,18 20 shorter birth interval,20 hard work and low nutritious food consumption during pregnancy,17 antepartum haemorrhage and anaemia,19 hypertension disorder and diabetes during pregnancy.21 Various sociodemographic factors affecting mothers such as living in rural territories,1 illiteracy,1 18 poor economic status1 20 and victims of any kind of intimate partner violence (IPV) either physical, sexual or mental22 are also significantly associated with risk factors for LBW. Therefore, an understanding of the aetiology of LBW and various other factors affecting the health of newborns is vital for the development of effective prevention programmes.

The WHO set a goal of a 30% reduction in the rate of LBW worldwide to be achieved by 2025 in order to meet its sustainable development goals (SDGs). In common with other countries in South Asia, the lack of a monitoring and surveillance system, a well-developed birth registry system, and quality data on birth weight in Bangladesh pose key challenges for the country. This study aims to help redress this situation. This study analysed a nationwide population survey to explore the prevalence of LBW and also assess the association of various adverse maternal circumstances with LBW in Bangladesh.

Methodology

Data sources and sampling procedure

This study analysed data extracted from the 2014 Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey (BDHS). A detailed explanation of the survey has been published elsewhere23 but briefly, it is based on a two-stage stratified sampling procedure where the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics divided the country into several primary sampling units (PSUs)23 and the survey was then carried out in each of the seven administrative divisions of Bangladesh. In the first sampling stage, 600 enumeration areas (EA) were selected as the PSU based on a probability proportional to their size (207 EAs in urban areas and 393 EAs in rural areas). In the second stage, 30 households were selected in each PSU by systematic random sampling.23 Following this process, the BDHS identified 18 245 ever-married women of reproductive-age (15–49 years) from 18 000 households. There was an overall response rate of around 98% with 17 863 women interviewed and a wide range of data collected on women and their children covering a range of indicators including health and nutrition. The survey also collected data on 7886 children that were born to women interviewees within 5 years prior to the year of the survey. This study excluded 3158 individuals because of unavailability of data regarding birth weight or size. The eligible sample size for the analysis was n=4728.

Outcome variable

LBW was considered to be the main outcome variable, dichotomised as yes=1 (baby born with LBW) and no=0 (otherwise). A great number of deliveries in LMICs generally, including in Bangladesh, occur at home without appropriate measurement of birth weight.24 The BDHS retrospectively gathered data on birth size based on the perceptions of the mothers, and questioned all women who had given birth within 5 years prior to the year of the survey. The question they were asked was: ‘was the baby very large, larger than average, average, smaller than average or very small at the time of birth?’. The reporting of baby size at birth as ‘very small’ or ‘smaller than average’ were considered useful proxies for LBW.23 24 Studies using other demographic and health survey data estimated that perceptions of mothers towards the birth weights of their babies were correct around 75% of the time.24 25

Explanatory variables

The sociodemographic and adverse maternal circumstances of mothers including being under or overweight, having unwanted births, IPV, previous pregnancy terminations and maternal high-risk fertility behaviours were considered as explanatory variables of occurrence and non-occurrence of LBW in newborns. A complete list of explanatory variables is presented in table 1. The selection process for these variables followed BDHS guidelines and also reviews of previous literature.1 17 23 26–31

Table 1.

A complete list and details of explanatory variables

| Variables | Collected data | Answer category |

| Sociodemographic variables | ||

| Maternal education* | Maternal highest level of education | 1=No education; 2=Primary; 3=Secondary and above |

| Residence | Place of residence | 1=Urban; 2=Rural |

| Economic status | Wealth index of the family | 1=Poor; 2=Middle; 3=Rich |

| Employment status | Employment status of the individuals | 1=Unemployed; 2=Employed |

| Adverse maternal characteristics | ||

| Underweight mother | The nutritional status (BMI) of mother was measured and if BMI was less than 18.5 kg/m2 then she was underweight | 0=No; 1=Yes |

| Overweight/obese mother | The nutritional status (BMI) of mother was measured and if BMI was higher than 25.0 kg/m2 then she was overweight and BMI was higher than 30.0 kg/m2 then she was obese | 0=No; 1=Yes |

| Unwanted birth | The child birth was not wanted at that time | 0=No; 1=Yes |

| Ever had a terminated pregnancy | The mother had a previous pregnancy termination history (abortion, miscarriage, etc) | 0=No; 1=Yes |

| Victim of intimate partner violence (IPV) | The mother who were a victim of IPV such as beaten in front of child, beaten by husband when refuse to intercourse or burn food etc | 0=No; 1=Yes |

| ANC <4 times | The mother who had used ANC less than four times during pregnancy | 0=No; 1=Yes |

| Maternal high-risk fertility behaviours† | ||

| Maternal age at birth <18 years | The mother whose age at the time of the birth was less than 18 years | 0=No; 1=Yes |

| Maternal age at birth >34 years | The mother whose age at the time of the birth was greater than 34 years | 0=No; 1=Yes |

| Birth interval <24 months | The mother who gave birth with a birth interval of less than 24 months | 0=No; 1=Yes |

| Birth order >3 | The mother whose birth order was higher than 3 | 0=No; 1=Yes |

| Maternal age at birth <18 years and birth interval <24 months‡ | The mother whose age at the time of the birth was less than 18 years with an interval of less than 24 months | 0=No; 1=Yes |

| Maternal age at birth >34 years and birth interval <24 months§ | The mother whose age at the time of the birth was greater than 34 years with an interval of less than 24 months | 0=No; 1=Yes |

| Birth interval <24 months and birth order >3 | The mother whose birth order was higher than 3 with interval of less than 24 months | 0=No; 1=Yes |

The analysis was restricted for children who were born within 5 years prior to the survey. High-risk fertility behaviour variables categorisation followed Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey (BDHS) standard measure.

*Primary and secondary education is defined as completing grade 5 and 10, respectively.

†Followed standard BDHS measure.

‡Includes the categories ‘age at birth <18 years with birth order >3’ and ‘age at birth <18 years with interval <24 months and birth order>3’.

§Includes the categories ‘age at birth <34 years with interval <24 months’ and ‘age at birth <34 years with interval <24 months and birth order >3’.

ANC, antenatal care; BMI, body mass index.

Statistical analysis

The prevalence of LBW was measured for the entire study population. The association between LBW and different sociodemographic and adverse maternal circumstances including high-risk fertility behaviours were assessed by χ2 tests (set at p<0.05 level of significance). A binary logistic regression model was then fitted as the outcome variable had binary categories, and ORs, both unadjusted and adjusted, were estimated in order to measure the effect of explanatory variables on the outcome variable. Each of the ORs were assessed for 95% CIs to help identify their levels of significance. The dataset had fewer than 5% of missing variables. Multiple imputation techniques using linear regression were applied to known values in order to provide an estimate of the missing values.32 This analysis was intended to ensure representativeness and to prevent misinterpretation or any bias.32 Place of residence, education, economic status and employment status were used as covariates. The analysis for this study took into account complex survey design and sample weights (svy: command in Stata) and was performed using the computer programme Stata in Windows V.13.0.

Patient and public involvement

The BDHS 2014 questionnaires were based on the MEASURE DHS model questionnaires with. patients not directly involved in the study. The country representative survey was conducted in seven administrative divisions of Bangladesh involving women of reproductive age. Information collected about the birth weight of the children was based on the perceptions of the mothers. While it was not possible to disseminate the study results to the survey participants, the results will be used by health researchers and policy makers.

Results

Prevalence and distribution of LBW

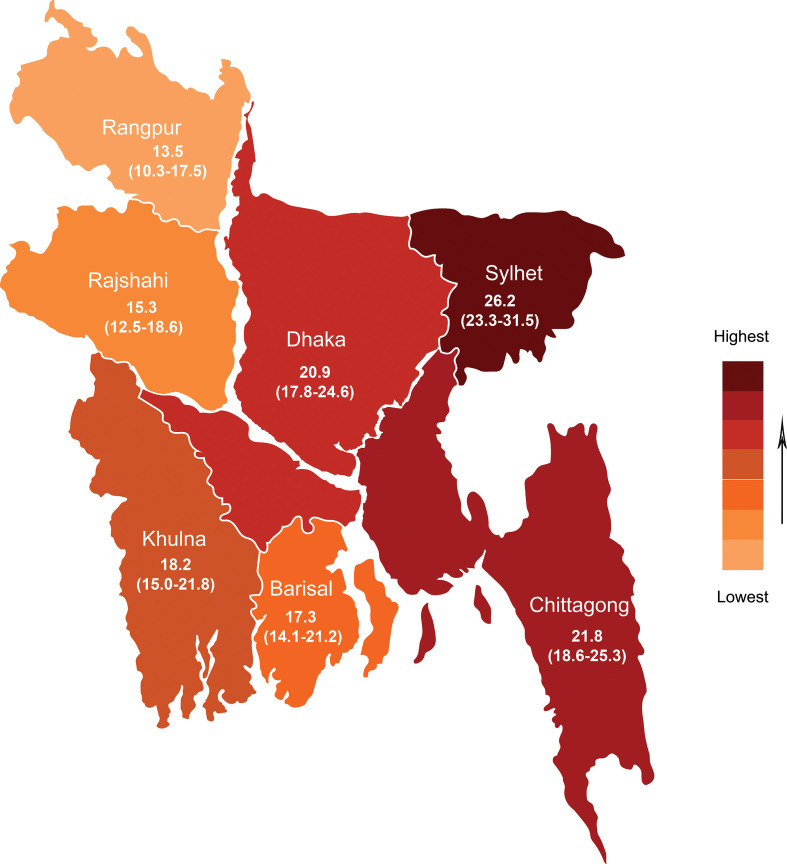

The prevalence of LBW and its association with several adverse maternal circumstances are presented in table 2. The prevalence of LBW in newborns in Bangladesh was found to be at 19.9%. The geographical prevalence of LBW across the seven administrative regions, based on the 2014 BDHS dataset, is presented in figure 1 that shows the highest prevalence of LBW occurred in the Sylhet region (26.2%) while the lowest prevalence was found in the Rangpur region (13.5%). Prevalence was also noticeably higher in the Dhaka (20.9%) and Chittagong (21.8%) regions.

Table 2.

The prevalence of low birth weight and its association with sociodemographic risk factors, adverse maternal characteristics including maternal high-risk fertility behaviours in Bangladesh, Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2014

| Background characteristics | Low birth weight (%, 95% CI) |

P value |

| Overall | 19.9 (18.5 to 21.5) | |

| Sociodemographic variables | ||

| Residence | <0.001 | |

| Urban | 17.5 (15.1 to 20.2) | |

| Rural | 20.8 (18.9 to 22.8) | |

| Maternal education | <0.001 | |

| No education | 26.6 (22.2 to 31.5) | |

| Primary | 21.1 (18.2 to 24.3) | |

| Secondary and above | 17.7 (16.0 to 19.7) | |

| Economic status | <0.001 | |

| Poor | 22.3 (19.8 to 24.9) | |

| Middle | 19.7 (15.8 to 24.3) | |

| Rich | 17.7 (15.5 to 20.1) | |

| Employment status | 0.683 | |

| Unemployed | 19.6 (17.7 to 21.6) | |

| Employed | 21.1 (18.1 to 24.4) | |

| Adverse maternal characteristics | ||

| Underweight mother | <0.001 | |

| No | 18.4 (16.6 to 20.2) | |

| Yes | 24.9 (21.9 to 28.1) | |

| Overweight/obese mother | 0.004 | |

| No | 20.8 (19.1 to 22.5) | |

| Yes | 15.9 (12.9 to 19.3) | |

| Taken ANC <4 times | <0.001 | |

| No | 16.3 (14.4 to 18.4) | |

| Yes | 21.6 (19.6 to 23.7) | |

| Unwanted birth | 0.002 | |

| No | 19.0 (17.4 to 20.7) | |

| Yes | 24.6 (20.9 to 26.6) | |

| Ever had a terminated pregnancy | 0.096 | |

| No | 19.5 (17.9 to 21.2) | |

| Yes | 22.8 (18.8 to 27.2) | |

| Victim of intimate partner violence | 0.014 | |

| No | 19.5 (17.8 to 21.4) | |

| Yes | 21.0 (18.6 to 23.6) | |

| Maternal high-risk fertility behaviours | ||

| Maternal age at birth <18 years | <0.001 | |

| No | 18.5 (17.0 to 20.2) | |

| Yes | 29.2 (25.1 to 33.7) | |

| Maternal age at birth >34 years | 0.204 | |

| No | 19.5 (18.1 to 21.2) | |

| Yes | 23.0 (19.9 to 30.9) | |

| Birth interval <24 months | <0.001 | |

| No | 17.9 (16.7 to 19.7) | |

| Yes | 26.6 (23.5 to 29.8) | |

| Birth order >3 | 0.008 | |

| No | 19.3 (17.7 to 21.0) | |

| Yes | 24.0 (20.2 to 28.3) | |

| Maternal age at birth <18 years and birth interval <24 months | <0.001 | |

| No | 18.8 (17.3 to 20.5) | |

| Yes | 22.4 (19.6 to 25.5) | |

| Maternal age at birth >34 years and birth interval <24 months | 0.003 | |

| No | 18.8 (17.2 to 20.5) | |

| Yes | 27.1 (23.1 to 31.5) | |

| Birth order >3 and birth interval <24 months | 0.011 | |

| No | 19.7 (18.3 to 21.4) | |

| Yes | 24.5 (18.0 to 32.5) | |

The sample was weighted. ‘No’ values for low birth weight was omitted from the table and calculated for row percentage.

ANC, antenatal care.

Figure 1.

Geographical prevalence (%, 95% CI) of low birth weight according to seven administrative divisions in Bangladesh (using data Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2014).

The prevalence of LBW was observed to be significantly higher in rural territories (20.8%), in poor households (22.3%) and among uneducated mothers (26.6%). Several adverse maternal circumstances were significantly related to the higher prevalence of LBW including underweight mothers (24.9%), women who did not have antenatal care (ANC) at least four times (21.6%) during pregnancy, unwanted births (24.6%) and mothers who were victims of IPV (21.0%). Similarly, the LBW prevalence was also observed to be remarkably higher for women with high-risk fertility behaviours such as aged <18 years at the time of birth (29.2%), and for women whose birth interval was <24 months (26.6%). The prevalence of LBW in newborns was noticeably increased if multiple characteristics of high-risk fertility behaviours were taken together. For instance, LBW in newborns was found among mothers aged <18 years at the time of childbirth with birth intervals <24 months (22.4%); maternal age at birth >34 years with birth interval <24 months (27.1%) and birth order >3 with birth interval <24 months (24.5%).

Association of adverse maternal situations with LBW

Table 3 illustrates a logistic regression analysis that assessed the effect that several adverse maternal circumstances can have on LBW. The risk was shown to be higher in rural territories (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) 1.22, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.46) compared with urban areas. Maternal education, however, was found to offer some protection against LBW. The likelihood of women giving birth to LBW babies decreased for those with primary (AOR 0.72, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.90) and secondary and above levels of education (AOR 0.57, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.73) compared with uneducated women. The odds of having an LBW baby were significantly increased for underweight mothers (AOR 1.26, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.49), and for mothers who did not use ANC at least four times (AOR 1.23, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.48) during pregnancy compared with their counterparts. The risk of LBW also increased in the case of unwanted births (AOR 1.22, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.44), a history of pregnancy terminations (AOR 1.28, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.57), and victims of IPV (AOR 1.23, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.45) compared with their counterparts. A young age at childbirth (<18 years) and birth intervals <24 months indicated that these women had a 1.42 times (95% CI 1.11 to 1.83) and a 1.26 times (95% CI 1.02 to 1.57) increased risk of LBW in their newborns respectively, compared with women that did not have such risky fertility behaviour. Other risk factors could also have an effect on LBW such as birth order >3 with interval <24 months (AOR 1.68, 95% CI 1.18 to 2.37).

Table 3.

UOR and AOR to measure the association size of adverse maternal characteristics on newborn’s low birth weight in Bangladesh, Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2014

| Background characteristics | Low birth weight | |

| UOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

| Sociodemographic variables | ||

| Residence | ||

| Urban(RC) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Rural | 1.34 (1.16 to 1.61)‡ | 1.22 (1.02 to 1.46)* |

| Maternal education | ||

| No education(RC) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Primary | 0.73 (0.59 to 0.90)† | 0.72 (0.57 to 0.90)† |

| Secondary and above | 0.54 (0.44 to 0.66)‡ | 0.57 (0.45 to 0.73)‡ |

| Economic status | ||

| Poor(RC) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Middle | 0.87 (0.71 to 1.06) | 1.03 (0.84 to 1.26) |

| Rich | 0.68 (0.58 to 0.80)‡ | 0.97 (0.79 to 1.18) |

| Employment status | ||

| Unemployed(RC) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Employed | 1.04 (0.88 to 1.23) | 1.02 (0.86 to 1.21) |

| Adverse maternal characteristics | ||

| Underweight mother | ||

| No(RC) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 1.48 (1.25 to 1.72)‡ | 1.26 (1.06 to 1.49)† |

| Overweight/obese mother | ||

| No(RC) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 0.74 (0.61 to 0.91)† | 0.98 (0.78 to 1.23) |

| Taken ANC <4 times | ||

| No(RC) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 1.44 (1.23 to 1.70)‡ | 1.23 (1.03 to 1.48)* |

| Unwanted birth | ||

| No(RC) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 1.29 (1.10 to 1.51)† | 1.22 (1.03 to 1.44)* |

| Ever had a terminated pregnancy | ||

| No(RC) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 1.18 (0.97 to 1.43) | 1.28 (1.05 to 1.57)† |

| Victim of intimate partner violence | ||

| No(RC) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 1.22 (1.04 to 1.42)† | 1.23 (1.05 to 1.45)* |

| Maternal high-risk fertility behaviours | ||

| Maternal age at birth <18 years | ||

| No(RC) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 1.81 (1.50 to 2.19)‡ | 1.42 (1.11 to 1.83)† |

| Maternal age at birth >34 years | ||

| No(RC) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 1.23 (0.89 to 1.71) | 0.93 (0.63 to 1.39) |

| Birth interval <24 months | ||

| No(RC) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 1.54 (1.32 to 1.80)‡ | 1.25 (1.01 to 1.55)* |

| Birth order >3 | ||

| No(RC) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 1.30 (1.07 to 1.59)† | 1.04 (0.83 to 1.33) |

| Maternal age at birth <18 years and birth interval <24 months | ||

| No(RC) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 1.31 (1.12 to 1.53)‡ | 1.26 (1.02 to 1.57)† |

| Maternal age at birth >34 years and birth interval <24 months | ||

| No(RC) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 1.34 (1.11 to 1.64)† | 1.22 (0.97 to 1.54) |

| Birth order >3 and birth interval <24 months | ||

| No(RC) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 1.50 (1.09 to 2.06)* | 1.68 (1.18 to 2.37)† |

Model was adjusted for all the predictors included in this table.

*p<0.05.

†p<0.01.

‡p<0.001.

ANC, antenatal care; AOR, adjusted odds ratio; RC, Reference category; UOR, unadjusted odds ratio.

Discussion

This study analysed a country representative sample size of 4728 and found that various types of sociodemographic and adverse maternal factors, including high-risk fertility behaviours, are significantly increasing the likelihood of giving birth to an LBW child. The prevalence of LBW in Bangladesh was observed to be around 20% and the regional burden varying significantly with a very high prevalence in the Sylhet region and comparatively low prevalence in the Rangpur region. Though a significant reduction of the LBW rate in Bangladesh has been noted, it is still much higher than the global average.1 7 8 According to this study, the burden is comparatively higher in rural areas and within the illiterate community. Another study in a LMIC had similar findings to this study by identifying that illiterate and poor women had a significantly higher risk of giving birth to an LBW baby.33 Other research projects have found a significant association of LBW with a household’s economic situation, but this study did not discover any corroborative evidence for this particular finding.18 34

A well-established risk factor for giving birth to an LBW baby is for mothers to be underweight29 35 and this study corroborates earlier research findings where underweight mothers were found to be at higher risk than their counterparts.29 30 36 In underweight mothers, a deficiency of micronutrients and calories can impede the proper growth of the fetus so leading to an LBW newborn.37 In order to reduce this risk, the importance of proper maternal nutrition comes to the fore and taking ANC ≥4 times can help mitigate the incidence of LBW. The findings of this study regarding the higher chance of giving birth to an LBW baby among mothers who used ANC <4 times is consistent with other study results.18 38 In general, ANC provides the appropriate care required for both mother and newborn babies by addressing all forms of maternal health complications.25 34 38 In Ethiopia, Assefa et al. noted that women who did not use at least one ANC during pregnancy had a 1.6 times higher risk of giving birth to an LBW baby.34 A key challenge for reducing such risk is to reach those women and newborns in the greatest need.

Wado et al39 and Shah et al31 discovered that the risk of LBW in newborns was higher for unwanted births so supporting the findings in this study. Unwanted pregnancy also profoundly increases the risk of antenatal depression that is a crucial predictor of LBW.39 40 An unwanted pregnancy can cause a woman to feel anxiety, fear, excitement and happiness that may all fluctuate over the course of the pregnancy period and may cause variation in birth outcomes.31 41 The findings of this study indicate there is a higher likelihood for women who had ever had a pregnancy terminated of giving birth to LBW babies that resonates with other research projects.27 42 However, contrary to these findings, Ke et al43 observed no significant association between induced abortion and LBW for first-time mothers among southern Chinese women. This study’s findings of the high likelihood of women giving birth to LBW babies that had experienced any form of IPV, either physical or sexual, is supported by earlier study results.22 34 44 45 The LBW burden is much higher for women that experienced both physical and sexual IPV.22 IPV can also increase the risk of unintended pregnancies and be responsible for pregnancy complications that can both lead to LBW babies.31 46 47 Unintended pregnancies and IPV have direct connections with chronic psychosocial stress in women, that leads to a higher risk of giving birth to LBW babies.48

This study shows that a number of maternal high-risk fertility behaviours such as, young maternal age when giving birth (<18 years) and birth interval <24 months, are significantly increasing the risk of LBW in newborns49 that has also been shown in other research projects.17 28 50 Childbirth in adolescence is detrimental for child health due to maternal socioeconomic factors, immature behaviour and biological factors as women have comparatively underdeveloped reproductive systems.50 Consequently, a woman of this age cluster is often unable to handle the complexities of pregnancy and the fetus can be deprived of adequate nutrition required for proper growth and development.50 Giving birth again within a short interval (<24 months) markedly increases the risk of women having LBW babies that is consistent with previous findings.20 51 52 In northern Tanzania, a retrospective cohort study concluded that a shorter interpregnancy interval (<24 months) was 1.61 times more likely to increase the risk of giving birth to an LBW infant compared with an interpregnancy interval of 24–36 months.51 Among those women with a shorter interpregnancy interval, the depletion of iron and folic acid is observed that is related to an increased risk of foetal growth restriction.53 The risks of giving birth to an LBW baby is further increased if multiple high-risk behaviours are considered together. For example, if a woman gives birth during adolescence (<18 years) with a shorter birth interval (<24 months), then it is highly likely that the newborn will have a LBW. A similar risk was observed for a maternal higher birth order (>3) compared with a lower birth interval. It can be concluded, therefore, that maternal high-risk fertility behaviours are significantly associated with women giving birth to LBW babies.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The strengths of this study include the use of nationally representative data involving a large sample size that enabled the study to show reliable and precise results. In addition, the 2014 BDHS used a globally standardised method that enabled the results of this study to be compared with research in other countries that used a similar methodology. The study analysis took into account the complex survey design and sample weights that helped to provide greater accuracy in representing the country. However, some important limitations of this study should be mentioned. The measurement of LBW was defined by using a mother’s perception of the size of their child at birth instead of the actual birth weight due to the unavailability of official data. This therefore meant that under-reporting was likely as many mothers could only remember if LBW was a factor if the newborn was very small in size. In addition, the study outcome and predictors were based on self-reporting and past events were related through the recall method. Data collected through these methods mean that recall bias is common. The cross-sectional nature of the 2014 BDHS data did not allow for any causal inferences to be drawn between outcome variables and predictors and the use of secondary data limits the analysis in variable selection. For example, preterm birth is responsible for a large no. of LBW babies, but the dataset had no information about gestational age.

Conclusion

The high prevalence of LBW indicates a serious health hazard for newborn babies in Bangladesh. This study has explored the risk factors that may increase the prevalence of LBW in newborns and can be used as a basis for developing prevention strategies. This study also suggests that several socio-demographic and adverse maternal circumstances along with multiple high-risk fertility behaviours may impact on a newborn baby’s birth weight thereby increasing the risk of LBW. These findings highlight the vital importance of early screening and interventions targeted at all women. This study recommends that policymakers and public health authorities address these adverse maternal factors when designing prevention interventions to reduce LBW in newborns. In this regard, reproductive health promotion programmes among targeted individuals could be introduced to help in limiting adverse factors as well as LBW. In conclusion, adverse maternal circumstances can impede progress towards achieving the SDG target regarding newborn healthcare. There is no doubt that a continued effort for reducing the LBW prevalence in Bangladesh is of paramount importance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the Demographic and Health Survey programme for granting permission to use the data. Authors would like to express their gratitude to Dr. Helen Findlay for final checking and editing of the manuscript. The author Prof. Hafiz T. A. Khan is thankful to the Oxford Institute of Population Ageing, University of Oxford, UK, for academic support.

Footnotes

Contributors: MAK conceptualised the study and designed the analytical approach. MAK, GM and SK performed the data analyses and interpreted the findings. MAK and GM drafted the manuscript. RI, and HTAK helped in variable selection, revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and helped in the final approval of the version to be submitted. All authors helped to write the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Map disclaimer: The depiction of boundaries on this map does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ (or any member of its group) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. This map is provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available in a public, open access repository. Data are available upon reasonable request. The data sets used for the current study are publicly available upon request at dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm.

References

- 1.Khan JR, Islam MM, Awan N, et al. Analysis of low birth weight and its co-variants in Bangladesh based on a sub-sample from nationally representative survey. BMC Pediatr 2018;18:100. 10.1186/s12887-018-1068-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katz J, Lee AC, Kozuki N, et al. Mortality risk in preterm and small-for-gestational-age infants in low-income and middle-income countries: a pooled country analysis. Lancet 2013;382:417–25. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60993-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO Global nutrition targets 2025: low birth weight policy brief (WHO/NMH/NHD/14.5). 8 Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilcox AJ. On the importance-and the unimportance-of birthweight. Int J Epidemiol 2001;30:1233–41. 10.1093/ije/30.6.1233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saville NM, Shrestha BP, Style S, et al. Impact on birth weight and child growth of participatory learning and action women's groups with and without transfers of food or cash during pregnancy: findings of the low birth weight South Asia cluster-randomised controlled trial (LBWSAT) in Nepal. PLoS One 2018;13:e0194064. 10.1371/journal.pone.0194064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Veena SR, Krishnaveni GV, Wills AK, et al. Association of birthweight and head circumference at birth to cognitive performance in 9- to 10-year-old children in South India: prospective birth cohort study. Pediatr Res 2010;67:424–9. 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181d00b45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO Who | care of the preterm and low-birth-weight newborn: World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. Available: https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/newborns/prematurity/en/

- 8.National Nutrition Services (NNS) National low birth weight survey (NLBWS) Bangladesh, 2015. Dhaka, Bangladesh: National Nutrition Services, Institute of public health nutrition, Directorate general of health services, Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watkins WJ, Kotecha SJ, Kotecha S. All-Cause mortality of low birthweight infants in infancy, childhood, and adolescence: population study of England and Wales. PLoS Med 2016;13:e1002018. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brooks AM, Byrd RS, Weitzman M, et al. Impact of low birth weight on early childhood asthma in the United States. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2001;155:401–6. 10.1001/archpedi.155.3.401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franz AP, Bolat GU, Bolat H, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and very preterm/very low birth weight: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2018;141:e20171645. 10.1542/peds.2017-1645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee SM, Kim N, Namgung R, et al. Prediction of postnatal growth failure among very low birth weight infants. Sci Rep 2018;8:3729. 10.1038/s41598-018-21647-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christian P, Lee SE, Donahue Angel M, Sania A, Fall CH, Victora CG, et al. Risk of childhood undernutrition related to small-for-gestational age and preterm birth in low- and middle-income countries. Int J Epidemiol 2013;42:1340–55. 10.1093/ije/dyt109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tian J, Qiu M, Li Y, et al. Contribution of birth weight and adult waist circumference to cardiovascular disease risk in a longitudinal study. Sci Rep 2017;7:9768–68. 10.1038/s41598-017-10176-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Belbasis L, Savvidou MD, Kanu C, et al. Birth weight in relation to health and disease in later life: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. BMC Med 2016;14:147. 10.1186/s12916-016-0692-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mebrahtu TF, Feltbower RG, Greenwood DC, et al. Birth weight and childhood wheezing disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health 2015;69:500–8. 10.1136/jech-2014-204783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma SR, Giri S, Timalsina U, et al. Low birth weight at term and its determinants in a tertiary hospital of Nepal: a case-control study. PLoS One 2015;10:e0123962. 10.1371/journal.pone.0123962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahumud RA, Sultana M, Sarker AR. Distribution and determinants of low birth weight in developing countries. J Prev Med Public Health 2017;50:18–28. 10.3961/jpmph.16.087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feresu SA, Harlow SD, Woelk GB. Risk factors for low birthweight in Zimbabwean women: a secondary data analysis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0129705. 10.1371/journal.pone.0129705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silveira MF, Victora CG, Horta BL, et al. Low birthweight and preterm birth: trends and inequalities in four population-based birth cohorts in Pelotas, Brazil, 1982–2015. Int J Epidemiol 2019;48:i46–53. 10.1093/ije/dyy106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rao J, Fan D, Wu S, et al. Trend and risk factors of low birth weight and macrosomia in South China, 2005-2017: a retrospective observational study. Sci Rep 2018;8:3393. 10.1038/s41598-018-21771-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferdos J, Rahman MM. Maternal experience of intimate partner violence and low birth weight of children: a hospital-based study in Bangladesh. PLoS One 2017;12:e0187138. 10.1371/journal.pone.0187138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National institute of population research and training (NIPROT) 2016. Bangladesh demographic and health survey 2014 National institute of population research and training (NIPROT), Mitra and Associates, Dhaka, Bangladesh and ICF International, Calverton, Maryland, USA.

- 24.Rahman MS, Howlader T, Masud MS, et al. Association of Low-Birth weight with malnutrition in children under five years in Bangladesh: do mother's education, socio-economic status, and birth interval matter? PLoS One 2016;11:e0157814. 10.1371/journal.pone.0157814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raysul Haque SM, Tisha S, Huq N. Poor birth size a badge of low birth weight accompanying less antenatal care in Bangladesh with substantial divisional variation: evidence from BDHS-2011. Birth 2015;1:33–8. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rahman M, Islam MJ, Haque SE, et al. Association between high-risk fertility behaviours and the likelihood of chronic undernutrition and anaemia among married Bangladeshi women of reproductive age. Public Health Nutr 2017;20:305–14. 10.1017/S136898001600224X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown JS, Adera T, Masho SW. Previous abortion and the risk of low birth weight and preterm births. J Epidemiol Community Health 2008;62:16–22. 10.1136/jech.2006.050369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dennis JA, Mollborn S. Young maternal age and low birth weight risk: an exploration of racial/ethnic disparities in the birth outcomes of mothers in the United States. Soc Sci J 2013;50:625–34. 10.1016/j.soscij.2013.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.He Z, Bishwajit G, Yaya S, et al. Prevalence of low birth weight and its association with maternal body weight status in selected countries in Africa: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2018;8:e020410. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karim MR, Mondal MNI, Rana MM, et al. Maternal factors are important predictors of low birth weight: evidence from Bangladesh demographic & health survey-2011. Mal J Nutr 2016;22:257–65. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shah PS, Balkhair T, Ohlsson A, et al. Intention to become pregnant and low birth weight and preterm birth: a systematic review. Matern Child Health J 2011;15:205–16. 10.1007/s10995-009-0546-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sterne JAC, White IR, Carlin JB, et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ 2009;338:b2393. 10.1136/bmj.b2393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mahumud RA, Sultana M, Sarker AR. Distribution and determinants of low birth weight in developing countries. J Prev Med Public Health 2017;50:18–28. 10.3961/jpmph.16.087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Assefa N, Berhane Y, Worku A. Wealth status, mid upper arm circumference (MUAC) and antenatal care (Anc) are determinants for low birth weight in Kersa, Ethiopia. PLoS One 2012;7:e39957. 10.1371/journal.pone.0039957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Britto RPdeA, Florêncio TMT, Benedito Silva AA, et al. Influence of maternal height and weight on low birth weight: a cross-sectional study in poor communities of northeastern Brazil. PLoS One 2013;8:e80159. 10.1371/journal.pone.0080159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patel A, Prakash AA, Das PK, et al. Maternal anemia and underweight as determinants of pregnancy outcomes: cohort study in eastern rural Maharashtra, India. BMJ Open 2018;8:e021623. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-021623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Razak F, Finlay JE, Subramanian SV. Maternal underweight and child growth and development. The Lancet 2013;381:626–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60344-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pinzón-Rondón Ángela María, Gutiérrez-Pinzon V, Madriñan-Navia H, et al. Low birth weight and prenatal care in Colombia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015;15:118. 10.1186/s12884-015-0541-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wado YD, Afework MF, Hindin MJ. Effects of maternal pregnancy intention, depressive symptoms and social support on risk of low birth weight: a prospective study from southwestern Ethiopia. PLoS One 2014;9:e96304. 10.1371/journal.pone.0096304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Niemi M, Falkenberg T, Petzold M, et al. Symptoms of antenatal common mental disorders, preterm birth and low birthweight: a prospective cohort study in a semi-rural district of Vietnam. Trop Med Int Health 2013;18:687–95. 10.1111/tmi.12101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sable MR, Spencer JC, Stockbauer JW, et al. Pregnancy wantedness and adverse pregnancy outcomes: differences by race and Medicaid status. Fam Plann Perspect 1997;29:76–81. 10.2307/2953366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kc S, Hemminki E, Gissler M, et al. Perinatal outcomes after induced termination of pregnancy by methods: a nationwide register-based study of first births in Finland 1996-2013. PLoS One 2017;12:e0184078. 10.1371/journal.pone.0184078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ke L, Lin W, Liu Y, et al. Association of induced abortion with preterm birth risk in first-time mothers. Sci Rep 2018;8:5353. 10.1038/s41598-018-23695-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Henriksen L, Schei B, Vangen S, et al. Sexual violence and neonatal outcomes: a Norwegian population-based cohort study. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005935. 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chambliss LR. Intimate partner violence and its implication for pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2008;51:385–97. 10.1097/GRF.0b013e31816f29ce [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rahman M, Sasagawa T, Fujii R, et al. Intimate partner violence and unintended pregnancy among Bangladeshi women. J Interpers Violence 2012;27:2999–3015. 10.1177/0886260512441072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ferdos J, Rahman MM, Jesmin SS, et al. Association between intimate partner violence during pregnancy and maternal pregnancy complications among recently delivered women in Bangladesh. Aggress Behav 2018;44:294–305. 10.1002/ab.21752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Borders AEB, Grobman WA, Amsden LB, et al. Chronic stress and low birth weight neonates in a low-income population of women. Obstet Gynecol 2007;109:331–8. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000250535.97920.b5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rahman M, Hosen A, Khan MA. Association between maternal high-risk fertility behavior and childhood morbidity in Bangladesh: a nationally representative cross-sectional survey. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2019;101:929–36. 10.4269/ajtmh.19-0221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fall CHD, Sachdev HS, Osmond C, et al. Association between maternal age at childbirth and child and adult outcomes in the offspring: a prospective study in five low-income and middle-income countries (cohorts collaboration). Lancet Glob Health 2015;3:e366–77. 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00038-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mahande MJ, Obure J. Effect of interpregnancy interval on adverse pregnancy outcomes in northern Tanzania: a registry-based retrospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016;16:140. 10.1186/s12884-016-0929-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Veloso HJF, da Silva AAM, Bettiol H, et al. Low birth weight in São Luís, northeastern Brazil: trends and associated factors. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014;14:155. 10.1186/1471-2393-14-155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Winkvist A, Rasmussen KM, Habicht JP. A new definition of maternal depletion syndrome. Am J Public Health 1992;82:691–4. 10.2105/AJPH.82.5.691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- National institute of population research and training (NIPROT) 2016. Bangladesh demographic and health survey 2014 National institute of population research and training (NIPROT), Mitra and Associates, Dhaka, Bangladesh and ICF International, Calverton, Maryland, USA.