Abstract

Objectives

To investigate mothers’ knowledge and utilisation of antenatal and perinatal support services as well as predictors of knowledge and service utilisation.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

Prospective birth cohort in Regensburg, Eastern Bavaria, Germany.

Participants

2455 mothers after delivery.

Outcome measures

Participants’ knowledge of distinct antenatal and perinatal support services (poor vs good, defined by median split). Participants’ use of antenatal services provided by midwife (yes, no) and of any other antenatal support services (yes, no).

Results

The vast majority of mothers knew at least some support services. Two-thirds of women (68.4%) reported to have used the services provided by midwives. 23.6% of women reported to have used at least one of the other antenatal services. Good knowledge of services was associated with higher education (OR 1.37, 95% CI 1.13 to 1.67), no migration background (OR 2.26, 95% CI 1.76 to 2.90), better health literacy (OR 1.04, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.06), while being primiparous (OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.60 to 0.86) and being unmarried/living with a partner (OR 0.71, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.89) reduced the chance. Predictors of service utilisation differed with regard to the services considered.

Conclusions

Overall, mothers had a good level of knowledge of antenatal and perinatal support services. However, we found that some groups of women were less well informed. This inequality in social predictors of knowledge of services was also partly reflected in differences in service utilisation during pregnancy.

Keywords: epidemiology, maternal medicine, community child health, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study used data from a large sample of mothers who were comprehensively characterised.

This study succeeded at assessing data at a crucial point of time—during the first days after delivery of a child.

A large variety of different support services was considered.

Findings on service utilisation must be interpreted with caution as women’s objective need for service use was not assessed in the study.

The study sample is restricted to women who agreed to participate with their newborn child in a birth cohort study and selection bias cannot be excluded.

Introduction

Pregnancy and the transition to parenthood are important life events for expectant parents. While these periods are characterised by manifold requirements and adjustments of everyday life for all expectant parents some people may also be confronted with major psychosocial challenges. Problems can arise from the health of the woman or the child, partnership, financial situation, consequences of parenthood for employment and housing as well as dealing with expectations of family members and the society. Particularly vulnerable women may experience an exacerbation of problems during pregnancy and could potentially benefit from professional support during the antenatal and perinatal period.

In Germany, medical antenatal care for pregnant women is typically provided by physicians specialised in obstetrics/gynaecology. These services are highly used1; the majority of women are using even more than the recommended antenatal care visits.2 After childbirth, child health check-up examinations are provided by paediatricians or general practitioners. Overall, utilisation of child health check-ups is high, particularly for those examinations which are directed to very young children: according to the representative KiGGS survey (wave 1: 2009–2012), 97.5% of children participated in the examination scheduled for the fourth week of life.3 Pregnant women are also encouraged to engage a midwife and to participate in antenatal classes, mostly provided by midwives or nurses. Midwives are working in private practice and the costs for midwifery care are reimbursed by mandatory statutory or private health insurance. In addition to these offers from healthcare providers, various other support and counselling services exist in Germany intended to cover the needs of women and families during the antenatal and perinatal period.4 These services are mostly run by the municipalities, entail both health-related and social services, some of them with low barrier, others more difficult to access.

A previous study by Eickhorst and colleagues investigated parents’ knowledge and use of a wide variety of services for pregnancy and early childhood in Germany.5 Between 2014 and 2015, about 8000 parents of children between 4 weeks and 3 years of age were included in the study; recruitment of parents took place during their visit to a paediatrician. The authors found a social gradient in knowledge of services and programmes—parents with a higher level of education (considering both school and professional education) knew more of the services and programmes—and a differential effect of education on utilisation of programmes: while services provided from midwives and educational classes for parents were more often used by families with higher level of education, families with lower level of education more often used counselling services such as pregnancy counselling centre or family support services. That study has dealt with knowledge and utilisation of parents during their child’s first years of life when parents might have had many contacts to healthcare providers and might have had manifold opportunities to learn about services and programmes. In contrast, the present study focuses on the situation of mothers immediately after the birth of a child. We consider this a crucially important point in time: mothers are about to be discharged from hospital to their home and have to manage the transition to parenthood. It is of uppermost importance that they know which support services are available for them. Therefore, we aimed at describing which services are known by mothers after the birth of a child and which services were already used during pregnancy, using data from a large birth cohort study. In addition, predictors of knowledge and utilisation of services were explored.

Methods

Design

The KUNO-Kids health study is an ongoing birth cohort study situated in Regensburg, Eastern Bavaria (Germany). Rationale and design of the study have already been described elsewhere.6 Briefly, adult mothers giving birth in the St Hedwig Clinic (the university maternity and children’s hospital in the study region) are asked to participate in the study. Basic German language proficiency is considered necessary for understanding the study procedures. There are no exclusion criteria with regard to health or illness of mother or child. Data collection includes an interview with questions about knowledge and utilisation of antenatal and perinatal services as well as questions regarding sociodemographic and psychosocial information. Data are collected by trained medical students using a computer-assisted personal interview during the hospital stay of mother and child after birth.

Sample

The study sample includes mothers who gave birth between July 2015 and June 2018. Two thousand five hundred and twenty mothers were included in the study sample, of whom 2494 participated in data assessment relevant for this analysis.

Measurement of outcomes and predictors

Outcomes: knowledge of antenatal and perinatal support services as well as utilisation of antenatal support services was assessed. Mothers were asked whether they knew a specific service (yes, no) and—for those services which can be used during pregnancy—whether they had used them (yes, no). The services considered in this study comprised:

Midwife: antenatal and perinatal healthcare for mother and child.

Paediatric nurse: care and support for families with infants with disabilities or diseases.

Pregnancy counselling centre: counselling services with a focus on financial support, family conflicts and unwanted pregnancy.

Counselling centre for breast feeding: counselling for breast feeding and child nutrition.

Counselling centre for infant crying: counselling for families with infants who cry intensely and persistently.

Family centre/family support services: counselling and advice for families.

Coordinating child protection office (‘KOKI’): comprehensive support for families at risk.

Youth welfare office: counselling with focus on care, education and protection of the child.

Education counselling centre: counselling with focus on child care and education.

Community centre/projects: various offers, located in the neighbourhood.

‘Fit for family’: regional programmes provided by nurses/midwives during pregnancy and infancy.

Other.

The selection of services considered in this study reflects the offers widely available in Germany and additionally those offers which are particularly available in the study region.

Further, it was assessed through which sources mothers received information about these services (obstetrician/gynaecologist, midwife, hospital, paediatrician, family/friends, searching for oneself, other).

Predictors of knowledge and utilisation of services: sociodemographic information, parity, health literacy and health insurance status were considered potentially predictive variables of knowledge and utilisation of services. Sociodemographic variables included age (years), marital status (married and living with husband, unmarried and living together with partner, unmarried and living without partner/divorced/widowed), migration background (born in Germany, born outside of Germany), educational level (<10 years of schooling, 10 years of schooling, university entrance level) and employment before giving birth (yes, no). Parity was categorised into primiparous versus multiparous. Women’s health literacy was assessed using the healthcare scale of the European Health Literacy Survey questionnaire (HLS-EU).7 Health insurance status was categorised into statutory health insurance versus private or other health insurance.

Statistics

Characteristics of the study sample are described using means and SD for metric variables and percentages and frequencies for categorical variables. Missing values were not imputed. First, knowledge and utilisation of services as well as information sources about services are presented by descriptive statistics. Then, variables on knowledge and utilisation of services were aggregated in order to use them as outcome variables in prediction modelling. A variable indicating the total number of services known was created. Median split was used to derive two categories (poor vs good knowledge). Regarding the use of services, two variables were built: the use of services provided by midwives (yes, no) and the use of any other antenatal service (yes, no). Finally, predictive regression modelling was performed for analysing predictors of knowledge and utilisation of services. For all predictors, univariable logistic regression models with knowledge and utilisation as outcomes were calculated, respectively. Variables which were associated with the outcome in univariable analysis (criterion p≤0.2) were entered into the multivariable model. All analyses were performed using SPSS V.23.

Patient and public involvement

Parents were not involved in the design and conduct of this study. Findings of this study will be disseminated to study participants by regular newsletters which summarise novel findings gained from the KUNO-Kids health study.

Results

Descriptive results

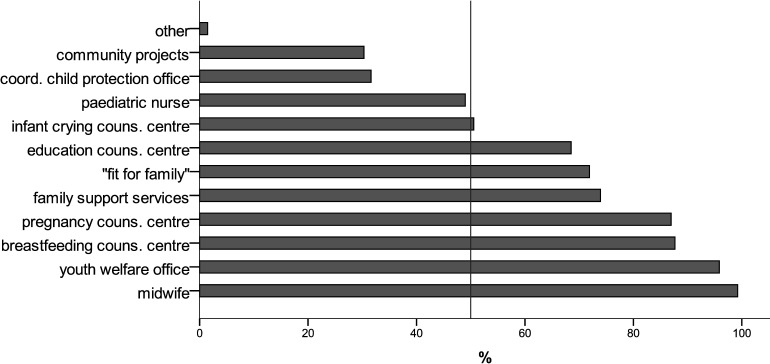

The characteristics of the study sample are summarised in the online supplemental table 1. Two thousand four hundred and fifty-five women provided data on knowledge and utilisation of antenatal and perinatal social and health-related services (see figure 1). More than 90% of mothers knew the services offered by midwives and youth welfare offices; however, only about 30% knew the coordinating child protection office and community projects. The median number of services known was 8 (IQR: 6–9).

Figure 1.

Proportions of women who knew specific antenatal and perinatal health and social services (n=2455).

bmjopen-2020-037745supp001.pdf (49.5KB, pdf)

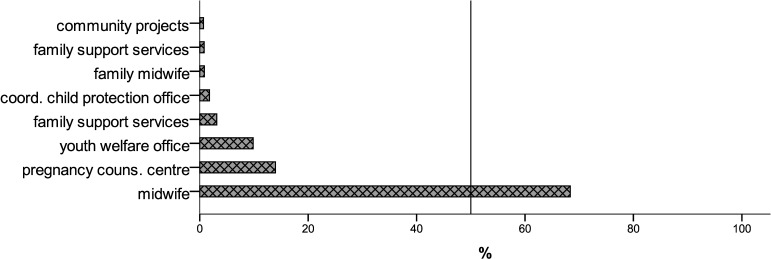

Figure 2 gives an overview on which of the social and health-related services had already been used by study participants during pregnancy. By far, the most frequently used services were those provided by midwives: two-thirds of women (68.4%) reported to have used them. Pregnancy counselling office and the youth welfare service were used by 14.0% and 9.9% of mothers, respectively. 23.6% of women reported to have used at least one of the antenatal services (excluding the use of midwives).

Figure 2.

Proportions of women who used specific antenatal health and social services (n=2455).

When mothers were asked about the sources of information they had used to learn about the various social and health-related services the most frequently reported answer was that they had researched on their own (72.8%), followed by information provided through family and friends (56.3%). Healthcare professionals were named as information source by 20%–50% of study participants: gynaecologist/obstetrician (46.9%), paediatrician (13.1%), hospital (30.2%) and midwife (30.8%). Overall, two-thirds of women reported that they had been informed about antenatal and perinatal social and health-related services by a healthcare professional.

Analytical results

Tables 1–3 show the results of the univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses.

Table 1.

Predictors of good knowledge of antenatal and perinatal social services: univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses

| Univariable | Multivariable | |||||

| OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Age (years) | 1.05 | 1.03 to 1.07 | <0.001 | 1.02 | 1.00 to 1.04 | 0.055 |

| Primiparous (vs multiparous) | 0.69 | 0.60 to 0.81 | <0.001 | 0.72 | 0.60 to 0.86 | <0.001 |

| Marital status* | ||||||

| Married, living together with husband | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Unmarried, living together with partner | 0.66 | 0.54 to 0.81 | <0.001 | 0.71 | 0.57 to 0.89 | 0.003 |

| Unmarried and without partner, divorced or widowed | 0.83 | 0.50 to 1.39 | 0.482 | 0.99 | 0.57 to 1.71 | 0.960 |

| Educational level† | ||||||

| Low (<10 years of schooling) | 0.60 | 0.45 to 0.79 | <0.001 | 0.68 | 0.51 to 0.92 | 0.011 |

| Medium (10 years of schooling) | Ref | Ref | ||||

| High (university entrance level) | 1.39 | 1.17 to 1.66 | <0.001 | 1.37 | 1.13 to 1.67 | 0.002 |

| Employed before giving birth | 1.28 | 1.01 to 1.63 | 0.041 | 1.12 | 0.86 to 1.47 | 0.389 |

| Born in Germany | 2.19 | 1.75 to 2.75 | <0.001 | 2.26 | 1.76 to 2.90 | <0.001 |

| Statutory health insurance (vs private or other health insurance) | 0.58 | 0.46 to 0.73 | <0.001 | 1.20 | 0.93 to 1.53 | 0.163 |

| Health literacy | 1.05 | 1.04 to 1.06 | <0.001 | 1.04 | 1.03 to 1.06 | <0.001 |

Multivariable analysis: n=2349; Nagelkerke’s R2: 0.10.

Good knowledge of services was defined by median split as knowledge of at least eight services.

Health literacy refers to healthcare scale of the HLS-EU questionnaire.

*Univariable analysis: omnibus test: χ2=16.22 (df=2), p<0.001.

†Univariable analysis: omnibus test: χ2=44.94 (df=2), p<0.001.

HLS-EU, European Health Literacy Survey; Ref, reference category.

Table 2.

Predictors of utilisation of services provided by midwives during pregnancy: univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses

| Univariable | Multivariable | |||||

| OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Age (years) | 1.00 | 0.98 to 1.02 | 0.741 | |||

| Primiparous (vs multiparous) | 1.81 | 1.52 to 2.15 | <0.001 | 1.77 | 1.48 to 2.12 | <0.001 |

| Marital status* | ||||||

| Married, living together with husband | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Unmarried, living together with partner | 0.93 | 0.75 to 1.16 | 0.543 | 0.85 | 0.68 to 1.07 | 0.180 |

| Unmarried and without partner, divorced or widowed | 0.55 | 0.32 to 0.92 | 0.024 | 0.63 | 0.37 to 1.08 | 0.091 |

| Educational level† | ||||||

| Low (<10 years of schooling) | 0.62 | 0.47 to 0.82 | 0.001 | 0.67 | 0.50 to 0.89 | 0.006 |

| Medium (10 years of schooling) | Ref | Ref | ||||

| High (university entrance level) | 1.38 | 1.14 to 1.67 | 0.001 | 1.37 | 1.12 to 1.67 | 0.002 |

| Employed before giving birth | 1.41 | 1.10 to 1.80 | 0.007 | 1.09 | 0.83 to 1.41 | 0.539 |

| Born in Germany | 1.56 | 1.24 to 1.95 | <0.001 | 1.53 | 1.20 to 1.95 | 0.001 |

| Statutory health insurance (vs private or other health insurance) | 0.71 | 0.55 to 0.91 | 0.008 | 1.12 | 0.86 to 1.47 | 0.399 |

| Health literacy | 0.99 | 0.98 to 1.01 | 0.394 | |||

Multivariable analysis: n=2428; Nagelkerke’s R2: 0.06.

Health literacy refers to healthcare scale of the HLS-EU questionnaire.

*Univariable analysis: omnibus test: χ2=5.15 (df=2), p=0.076.

†Univariable analysis: omnibus test: χ2=37.92 (df=2), p<0.001.

HLS-EU, European Health Literacy Survey; Ref, reference category.

Table 3.

Predictors of utilisation of any antenatal social service (excluding midwives): univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses

| Univariable | Multivariable | |||||

| OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Age (years) | 0.92 | 0.90 to 0.94 | <0.001 | 0.94 | 0.92 to 0.97 | <0.001 |

| Primiparous (vs multiparous) | 2.13 | 1.75 to 2.60 | <0.001 | 1.61 | 1.28 to 2.03 | <0.001 |

| Marital status* | ||||||

| Married, living together with husband | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Unmarried, living together with partner | 6.42 | 5.15 to 8.00 | <0.001 | 5.48 | 4.36 to 6.90 | <0.001 |

| Unmarried and without partner, divorced or widowed | 9.75 | 5.68 to 16.73 | <0.001 | 10.78 | 6.15 to 18.87 | <0.001 |

| Educational level† | ||||||

| Low (<10 years of schooling) | 1.76 | 1.30 to 2.39 | <0.001 | 1.28 | 0.90 to 1.82 | 0.165 |

| Medium (10 years of schooling) | Ref | Ref | ||||

| High (university entrance level) | 1.12 | 0.91 to 1.39 | 0.274 | 1.44 | 1.13 to 1.84 | 0.003 |

| Employed before giving birth | 0.77 | 0.59 to 1.01 | 0.059 | 0.76 | 0.55 to 1.05 | 0.095 |

| Born in Germany | 0.92 | 0.71 to 1.18 | 0.512 | |||

| Statutory health insurance (vs private or other health insurance) | 1.83 | 1.35 to 2.48 | <0.001 | 0.64 | 0.46 to 0.90 | 0.009 |

| Health literacy | 1.00 | 0.99 to 1.01 | 0.946 | |||

Multivariable analysis: n=2400; Nagelkerke’s R2: 0.22.

Health literacy refers to healthcare scale of the HLS-EU questionnaire.

*Univariable analysis: omnibus test: Χ2=319.05 (df=2), p<0.001.

†Univariable analysis: omnibus test: Χ2=13.07 (df=2), p=0.001.

HLS-EU, European Health Literacy Survey; Ref, reference category.

Good knowledge of services was defined by median split as knowing at least eight distinct services. In the multivariable model, higher education (OR 1.37, 95% CI 1.13 to 1.67), no migration background (OR 2.26, 95% CI 1.76 to 2.90) and better health literacy (OR 1.04, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.06) significantly increased the chance of good knowledge of services, while being primiparous (OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.60 to 0.86), being unmarried/living with a partner (OR 0.71; 95% CI 0.57 to 0.89) and lower education significantly reduced the chance (OR 0.68, 95% CI 0.51 to 0.92) (see table 1).

The utilisation of antenatal services provided by a midwife was significantly associated with parity, education and migration background. In the multivariable model, first-time mothers (OR 1.77, 95% CI 1.48 to 2.12) were more likely to have used the services of midwives as well as women who were born in Germany (OR 1.53, 95% CI 1.20 to 1.95). When compared with medium educational level a higher educational level was associated with an increased chance of service utilisation (OR 1.37, 95% CI 1.12 to 1.67) and a lower educational level was associated with a decreased chance (OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.50 to 0.89) (see table 2).

For the utilisation of any antenatal service (excluding the services provided by midwives), the multivariable model yielded statistically significant associations for age, parity, marital status, educational level and health insurance status, with higher age (OR 0.95, 95% CI 0.92 to 0.97) and having a statutory health insurance (OR 0.64, 95% CI 0.46 to 0.90) decreasing the chance of any service utilisation, while being primiparous (OR 1.61, 95% CI 1.28 to 2.03), being unmarried/living with a partner (OR 5.48, 95% CI 4.36 to 6.90), living without a partner/being divorced/widowed (OR 10.78, 95% CI 6.15 to 18.87) and having a higher educational level (OR 1.44, 95% CI 1.13 to 1.84) (compared with a medium level of education) increased the chance of service utilisation (see table 3).

Discussion

This study investigated knowledge and utilisation of antenatal and perinatal support services among a large sample of mothers of newborns. The most important findings are as follows: knowledge of support services was high and the vast majority of mothers knew at least a few services. However, some specific services were not well known and sociodemographic factors were found to be associated with both knowledge and utilisation of services. The most frequently reported source of information about support services was women’s own research and information seeking.

Our study revealed a social gradient: women with a higher level of education and without migration background were more likely to have good knowledge of the support services considered in our study. These results corroborate previous findings by Eickhorst and colleagues who investigated knowledge of services among parents of children between 0 and 3 years of age in Germany5 and found that education and migration background were determinants of knowledge of psychosocial support services.

Depending on which services were considered our study yielded different factors associated with the utilisation of services. While the use of a midwife during pregnancy was associated with variables indicative of higher social status (higher education, no migration background) the most important predictor for the use of any other support service was marital status. Women who were divorced or living without a partner were much more likely to have used any antenatal social service. A possible explanation for this finding is that these women experienced and also anticipated strains they could not have coped with without a partner.

Moreover, we found that first-time mothers were less likely to have good knowledge of the different support services suggesting that mothers develop a more comprehensive knowledge about services during parenthood. However, despite first-time mothers’ poorer knowledge they were also more likely to use both the midwife or any other antenatal service. This corresponds to the results of a study from Sweden which analysed parity and health service utilisation and found that first-time mothers used child health services more often.8

Overall, the predictive models for knowledge or utilisation of services in our study explained only small proportions of the variance observed between study participants (6%–22%). This indicates that variables beyond individual characteristics and social factors considered in our study are likely to be relevant for the prediction of knowledge and use of antenatal and perinatal services.

The services provided by midwives are of particular interest since these services were by far the best known and also the most used services investigated in our study. This is in line with findings from the above-mentioned study from Germany.5 Nevertheless, about one-third of women in our study reported to have not used the services of a midwife before delivery. As already mentioned, antenatal midwifery care is reimbursed by health insurance in Germany; however, pregnant women are supposed to engage a midwife on their own. Our findings do not allow to draw conclusions as to whether women did not wish to engage a midwife or whether there were other barriers. While the association with parity suggests that mothers who had already given birth to a child before might have had the perception to be less in need of a midwife there were also associations with lower level of education and migration background suggesting difficulties in accessibility of services. With regard to the latter a focus group with pregnant women and mothers revealed that the knowledge about specific offers and competences of midwives is scarce and that access to and availability of midwives can be limited in Germany.9

Remarkably, our findings on information sources about social services which were recalled by mothers show that the medical professions and institutions were not the predominant source for information. Less than half of study participants mentioned that their gynaecologist/obstetrician had provided information on support services.

Findings on knowledge and utilisation of support services must not be interpreted without considering the context of the national healthcare and welfare system: in Germany, on the one hand, the situation for pregnant women and mothers of infants is characterised by the availability of comprehensive and highly specialised medical and social care services whose use is free of charge or reimbursed by (mandatory) health insurance. On the other hand, the system is very complex and—despite some efforts during the past years—still remarkably fragmented. This applies to the division between the medical and the social sector, ambulatory and stationary healthcare, as well as to providers from different professional backgrounds who might pursue distinct goals and assume different perspectives.10 Fragmentation can cause overutilisation since people use different services simultaneously and important information for patient care and counselling can be lost if transitions are not standardised and communication between providers is not clearly structured. In addition, navigating through the system may be challenging for some women as pertaining inequalities in service utilisation suggest: large-scale surveys found a social gradient in utilisation of medical antenatal visits,11 non-medical antenatal visits12 and of health check-up examinations for children.3 Women’s difficulties in accessing antenatal and postnatal care were also described by qualitative studies.9 13

In the light of this, already in 2006, the Early Childhood Intervention Programme (‘Frühe Hilfen’) was implemented in Germany.4 It aims at the provision of psychosocial services by establishing structures which facilitate the cooperation of different service providers. However, collaboration and cooperation across and between sectors and disciplines remains a challenge,14 corroborating findings from other countries and health systems.15 16 Only about one-third of participants in our study knew the institution which coordinates the services of the Early Childhood Intervention Programme (coordinating child protection office).

One might argue as to whether women are really supposed to know all the different services which are available to pregnant women and mothers. Provided that all health/social care professionals are well trained and have the capabilities to recognise the different needs of women (eg, practical support, medical care, mental healthcare) and given that utilisation rates of medical antenatal care1 and child health check-up examinations are very high3 it does not seem to be necessary that every woman is an expert herself for all antenatal and perinatal services available. However, the services differ widely in scope and not all providers of services are equally equipped for meeting the different needs: for instance, paediatricians in Germany were found to be reluctant and to struggle to address psychosocial problems during the child health check-up examinations.17 18 This was also shown for other health professionals in studies from Ireland and Canada: midwives and nurses experienced many barriers when dealing with mental health issues of their patients.19 20

It would be desirable for the health and social care system to be designed in a way that enables women to identify and to access support so that access becomes less dependent on individual women’s capacity. Different approaches which strengthen the continuity of care or even foster integrated care have been proposed.21 22 While many studies from Germany and other countries with fragmented health services unravelled that mothers prefer continuous and coordinated care,9 23 24 such approaches have not yet been fully implemented in Germany. They would require a reorientation of health and social services and build on the local and regional infrastructures. Within the existing system the potential for collaboration between the service providers is not sufficiently exploited. Our finding that a remarkable proportion of participants did not receive information about support services through health professionals points in this direction.

Strengths and limitations

This study succeeded at assessing mothers’ knowledge of services at a crucial point of time: interviews were performed at the first days after delivery, before mother and newborn were referred from the hospital to their home. It is important to understand whether mothers are aware of the services available when they return to their home with their newborn child. The large sample size allowed to perform multivariable analysis considering various predictive factors of knowledge and service utilisation.

The inclusion criteria applied in KUNO-Kids health study led to the exclusion of underaged mothers and of mothers who could not understand the information on study procedures presented in German language. Regarding knowledge and utilisation of antenatal and perinatal services, this approach might have excluded women with particular need for those services and our study might overestimate the extent of both knowledge and utilisation of services. All data were assessed using self-report measurement instruments which might be prone to social desirability and/or recall bias. Despite data collection was comprehensive and covered many variables potentially relevant for service knowledge or use the proportion of variance explained was small. We cannot exclude that our regression models lacked important predictor variables which would have changed the resulting prediction models remarkably. Moreover, caution must be taken when interpreting our findings on the frequency of service utilisation. The women’s need for service was not assessed in our study and we cannot draw any conclusions about whether the proportion of women who used services was adequate or too low with regard to objective need factors as assessed by psychosocial risk screening.

It must be emphasised that both the cross-sectional design of this observational study and the predictive modelling strategy employed do not allow to draw any causal conclusions. Due to the lack of a theoretical model and prespecified analytical pathways our findings on predictors of knowledge and utilisation of services cannot be interpreted in terms of single risk factors. However, the study’s findings have policy implications and might be useful to inform the development of causal models which should be explored in future studies.

Conclusion

Mothers of infants have a good level of knowledge of antenatal and perinatal support services. However, some services are only known by about one-third of mothers. Social determinants of knowledge and of utilisation of services suggest inequality with regard to the preconditions for service utilisation. We propose better cooperation between the different service providers. This might help in facilitating access to support services during pregnancy and early childhood. Particularly, first-time mothers and socially disadvantaged women who were found to have poorer knowledge of services could benefit from such measures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the families who participated in the KUNO-Kids birth cohort study as well as all medical students, nurses, midwives, physicians and researchers who facilitated the recruitment of participants and data collection. Further, we thank all members of the KUNO-Kids study group.

Footnotes

Collaborators: The KUNO-Kids study group: Petra Arndt (ZNL Transfercenter of Neuroscience and Learning, University of Ulm, Ulm, Germany), Andrea Baessler (Department of Internal Medicine II, Regensburg University Medical Center, Regensburg, Germany), Mark Berneburg (Department of Dermatology, University Medical Centre Regensburg, Regensburg, Germany), Stephan Böse-O’Reilly (Institute and Clinic for Occupational, Social and Environmental Medicine, University Hospital, LMU Munich, Munich, Germany), Romuald Brunner (Clinic of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Psychosomatics and Psychotherapy, Bezirksklinikum Regensburg (medbo), Regensburg, Germany), Wolfgang Buchalla (Department of Conservative Dentistry and Periodontology, University Hospital Regensburg, University of Regensburg, Regensburg, Germany), Sara Fill Malfertheiner (Clinic of Obstetrics and Gynecology St. Hedwig, University of Regensburg, Regensburg, Germany), Andre Franke (Institute of Clinical Molecular Biology, Christian-Albrechts-University of Kiel, Kiel, Germany), Sebastian Häusler (Clinic of Obstetrics and Gynecology St. Hedwig, University of Regensburg, Regensburg, Germany), Iris Heid (Department of Genetic Epidemiology, University of Regensburg, Regensburg, Germany), Caroline Herr (Bavarian Health and Food Safety Authority (LGL), Munich, Germany), Wolfgang Högler (Department of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Johannes Kepler University Linz, Linz, Austria), Sebastian Kerzel (Department of Pediatric Pneumology and Allergy, University Children's Hospital Regensburg, St. Hedwig Campus, Regensburg, Germany), Michael Koller (Center for Clinical Studies, University Hospital Regensburg, Regensburg, Germany), Michael Leitzmann (Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, University of Regensburg, Regensburg, Germany), David Rothfuß (City of Regensburg, Coordinating Center for Early Interventions, Regensburg, Germany), Wolfgang Rösch (Department of Pediatric Urology, University Medical Center, Regensburg, Germany), Bianca Schaub (Pediatric Allergology, Dept of Pediatrics, Dr. von Hauner Children's Hospital, University Hospital, LMU Munich, Munich, Germany), Bernhard H.F. Weber (Institute of Human Genetics, University of Regensburg, Regensburg, Germany), Stephan Weidinger (Department of Dermatology, Venereology and Allergy, University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, Campus Kiel, Kiel, Germany) and Sven Wellmann (Children's Hospital St. Hedwig, University of Regensburg, Regensburg, Germany).

Contributors: SB designed the study, performed data analysis, interpreted the study findings, drafted the manuscript and critically evaluated the manuscript. DR contributed to the design of the study, helped interpret the study findings, critically evaluated the manuscript and approved the final manuscript. BSG and MM contributed to data collection, critically evaluated the manuscript and approved the final manuscript. MK contributed to the design of the study and data collection. He critically evaluated the manuscript and approved the final manuscript. CA designed the study, interpreted study findings and drafted the manuscript. He critically evaluated the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The KUNO-Kids health study was funded by research grants of the EU (HEALS: 603946). Further financial support was provided by the University Children’s Hospital Regensburg (KUNO-Clinics) and the clinic ‘St Hedwig’ (Hospital ‘Barmherzige Brüder Regensburg’).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Regensburg (file number: 14-101-0347). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request. Deidentified participant data which were analysed for this manuscript can be obtained upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Supplemental material This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1.Brenne S, David M, Borde T, et al. Are women with and without migration background reached equally well by health services? The example of antenatal care in Berlin. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2015;58:569–76. 10.1007/s00103-015-2141-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schäfers R, Kolip P. Zusatzangebote in der Schwangerschaft: sichere Rundumversorgung oder Geschäft mit der Unsicherheit? : Böcken J, Braun B, Meierjürgen R, Gesundheitsmonitor 2015. Berlin: Verlag Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2015: 119–50. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rattay P, Starker A, Domanska O, et al. Trends in the utilization of outpatient medical care in childhood and adolescence: results of the KiGGS study - a comparison of baseline and first follow up (KiGGS Wave 1). Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2014;57:878–91. 10.1007/s00103-014-1989-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Renner I, Saint V, Neumann A, et al. Improving psychosocial services for vulnerable families with young children: strengthening links between health and social services in Germany. BMJ 2018;363:k4786. 10.1136/bmj.k4786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eickhorst A, Schreier A, Brand C, et al. Knowledge and use of different support programs in the context of early prevention in relation to family-related psychosocial burden. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2016;59:1271–80. 10.1007/s00103-016-2422-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brandstetter S, Toncheva AA, Niggel J, et al. KUNO-Kids birth cohort study: rationale, design, and cohort description. Mol Cell Pediatr 2019;6:1. 10.1186/s40348-018-0088-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sørensen K, Van den Broucke S, Pelikan JM, et al. Measuring health literacy in populations: illuminating the design and development process of the European health literacy survey questionnaire (HLS-EU-Q). BMC Public Health 2013;13:948. 10.1186/1471-2458-13-948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lagerberg D, Magnusson M. Utilization of child health services, stress, social support and child characteristics in primiparous and multiparous mothers of 18-month-old children. Scand J Public Health 2013;41:374–83. 10.1177/1403494813484397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mattern E, Lohmann S, Ayerle GM. Experiences and wishes of women regarding systemic aspects of midwifery care in Germany: a qualitative study with focus groups. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017;17:389. 10.1186/s12884-017-1552-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reiss K, Flothkötter M, Greif NP, et al. Acceptance of recommendations of “healthy start - young family network” on infant nutrition and nutrition for breastfeeding mothers. A survey of different professional groups. Gesundheitswesen 2018;80:482–8. 10.1055/s-0042-116587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koller D, Lack N, Mielck A. Social differences in the utilisation of prenatal screening, smoking during pregnancy and birth weight-empirical analysis of data from the perinatal study in bavaria (Germany). Gesundheitswesen 2009;71:10–18. 10.1055/s-0028-1082310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ludwig A, Miani C, Breckenkamp J, et al. Are social status and migration background associated with utilization of non-medical antenatal care? analyses from two German studies. Matern Child Health J 2020;24:943–52. 10.1007/s10995-020-02937-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henry J, Beruf C, Fischer T. Access to health care for pregnant arabic-speaking refugee women and mothers in Germany. Qual Health Res 2020;30:437–47. 10.1177/1049732319873620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Renner I, Scharmanski S, van Staa J, et al. The health sector and early childhood intervention: intersectoral collaboration in research. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2018;61:1225–35. 10.1007/s00103-018-2805-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wieczorek CC, Marent B, Dorner TE, et al. The struggle for inter-professional teamwork and collaboration in maternity care: Austrian health professionals’ perspectives on the implementation of the baby-friendly hospital initiative. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:91. 10.1186/s12913-016-1336-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Psaila K, Schmied V, Fowler C, et al. Discontinuities between maternity and child and family health services: health professional's perceptions. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:4. 10.1186/1472-6963-14-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krippeit L, Belzer F, Martens-Le Bouar H, et al. Communicating psychosocial problems in German well-child visits. what facilitates, what impedes pediatric exploration? A qualitative study. Patient Educ Couns 2014;97:188–94. 10.1016/j.pec.2014.07.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barth M. Pediatrician-parent interaction and early prevention: a review about the limits in addressing psychosocial risks during well-child visits. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2016;59:1315–22. 10.1007/s00103-016-2426-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Viveiros CJ, Darling EK. Perceptions of barriers to accessing perinatal mental health care in midwifery: a scoping review. Midwifery 2019;70:106–18. 10.1016/j.midw.2018.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins A, Downes C, Monahan M, et al. Barriers to midwives and nurses addressing mental health issues with women during the perinatal period: the mind mothers study. J Clin Nurs 2018;27:1872–83. 10.1111/jocn.14252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sandall J, Soltani H, Gates S, et al. Midwife-led continuity models versus other models of care for childbearing women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;4:CD004667. 10.1002/14651858.CD004667.pub5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.D'Haenens F, Van Rompaey B, Swinnen E, et al. The effects of continuity of care on the health of mother and child in the postnatal period: a systematic review. Eur J Public Health 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kurth E, Krähenbühl K, Eicher M, et al. Safe start at home: what parents of newborns need after early discharge from hospital - a focus group study. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:82. 10.1186/s12913-016-1300-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rayment-Jones H, Harris J, Harden A, et al. How do women with social risk factors experience United Kingdom maternity care? A realist synthesis. Birth 2019;46:461–74. 10.1111/birt.12446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-037745supp001.pdf (49.5KB, pdf)