Abstract

Background:

Determining whether repigmentation within or adjacent to lentigo maligna or lentigo maligna melanoma (LM/LMM) scars represents recurrence of melanoma is challenging. The use of reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) and dermoscopy may aid in differentiating true melanoma recurrence from other causes of repigmentation.

Objectives:

To describe the characteristics of repigmentation within or adjacent to LM/LMM scars observable on RCM and dermoscopy.

Methods:

We retrospectively analysed patients who presented with new pigmentation within or adjacent to scars from surgically treated LM/LMM between January 2014 and December 2018. Clinical and demographic characteristics and time to recurrence were recorded. RCM was used to evaluate areas of pigmentation before biopsy. If available, dermoscopic images were evaluated.

Results:

In total, 30 confocal studies in 29 patients were included in the study cohort. Twenty-one patients had biopsy-confirmed recurrent LM/LMM; the remainder had pigmented actinic keratosis (n=4) or hyperpigmentation/solar lentigo (n=5). RCM had sensitivity of 95.24% (95% CI, 76.18%-99.88%), specificity of 77.7% (95% CI, 39.99%-97.19%), positive predictive value of 90.91% (95% CI, 74.58%-97.15%), and negative predictive value of 87.5% (95% CI, 50.04%-98.0%). The most common dermoscopic feature observed among patients with recurrent LM/LMM was focal homogeneous or structureless areas of light-brown pigmentation (92.8% vs 37.5% in patients with other diagnoses; P=0.009). LM-specific dermoscopic criteria were present in only 28.5% of patients with recurrent LM/LMM.

Conclusions:

RCM and dermoscopy are valuable tools for the comprehensive evaluation of repigmentation within or adjacent to LM scars.

Keywords: lentigo maligna, melanoma, reflectance confocal microscopy, recurrence, dermoscopy, dermatoscopy, pigmentation, repigmentation

Introduction

Lentigo maligna and lentigo maligna melanoma (LM/LMM) are the most common melanoma subtypes on the head and neck.1 LM/LMM often harbour subclinical extensions, which contribute at least in part, to the higher rates of local recurrence, compared with other melanoma subtypes.1-5 As LM/LMM develops on chronically sun-exposed areas, hyperpigmentation and formation of lentigines around melanoma scars is not uncommon. This new pigmentation within or adjacent to an LM/LMM surgical scar may pose a diagnostic challenge in differentiating recurrent melanoma from other diagnoses.3-6 Although biopsy remains the gold standard for diagnosing recurrent LM/LMM, limitations of biopsy include additional scarring, cost, time, and potential sampling error leading to false-negative diagnosis.

Reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) and dermoscopy are noninvasive imaging modalities that have high accuracy for diagnosis of primary LM/LMM.7,8 The use of RCM and dermoscopy for the diagnosis of recurrent LM/LMM is now being explored.9-11 Cinotti et al. showed that RCM had a higher sensitivity than dermoscopy for recurrent LM when compared to benign pigmented facial macules.11 Herein, we evaluated the role of RCM and dermoscopy in identifying LM/LMM recurrence in consecutive patients with recurrent pigmentation within or adjacent to a scar resulting from the surgical removal of LM/LMM.

Patients and methods

The institutional review board at Memorial Sloan Kettering approval this study (#99-099). All patients gave written informed consent. We reviewed our database from January 2014 to December 2018 for patients that presented with a clinical diagnosis of “possible recurrent LM” based on new areas of pigmentation within or adjacent to a surgical scar from a previous LM/LMM excision. Patients with a diagnosis of LM/LMM who were initially treated with nonsurgical techniques, such as imiquimod or radiation, were excluded from this study as they have been analysed previously.10 Initial surgical treatment was performed either at our cancer center or elsewhere. Demographics, clinical information, estimated size of repigmentation (diameter), images (clinical, dermoscopic, and RCM), and pathology reports were retrieved from patient medical charts. Clinical and dermoscopic images were acquired using the same digital camera (Veos DS3; Canfield Scientific, NJ, USA).

RCM evaluation:

RCM images were obtained prior to biopsy using a handheld RCM device (VivaScope 3000, Caliber ID, Rochester, NY) by 3 investigators (C.N-D, M.C., and K.L). Single images, stacks (from corneal layer to superficial dermis), and videos were obtained from the areas of pigmentation with the aid of paper rings, as previously described.12 The number of images/stacks/videos obtained varied case-by-case with the intent to evaluate the complete area of repigmentation. The pigmented areas were evaluated for the presence or absence of RCM-specific melanoma criteria, including bright large nucleated (dendritic or roundish) cells at the dermoepidermal junction (DEJ), suprabasal epidermis or superficial dermis, with or without perifollicular localization.13,14 RCM images were deemed “RCM-positive” or “RCM-negative” based on the Guitera et al criteria.7 RCM images were evaluated by 3 investigators (C.N.-D., M.C., and K.L.) who were blinded to the final histopathologic diagnosis.

Dermoscopic examination

Dermoscopic images were evaluated for LM/LMM-specific criteria, including circles (regular or irregular), circles within circles, annular-granular structures, angulated lines, and obliteration of hair follicles.8 Images were also analysed for the dermoscopic criteria described in the latest consensus by Kittler et al.15 Evaluation was performed for consensus by 2 investigators (C.N.-D. and A.A.M.) who were blinded to the final histopathologic diagnosis.

Histopathologic analysis

Biopsy specimens were obtained under RCM guidance from areas deemed to be concerning for melanoma on the basis of RCM criteria.7 All biopsy specimens were reviewed by an expert dermatopathologist (K.J.B.). Cases were labelled “melanoma” or “other diagnosis.” Results from RCM and dermoscopy were correlated with the final histopathologic diagnosis to evaluate the correlation between histopathologic examination and RCM or dermoscopy.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS 23.0 (SPSS, Armonk, NY, USA). Unless otherwise noted, all values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Fisher’s square test was used for categorical variables. Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated. Independent-samples student’s t test was performed for comparisons of continuous variables. A 2-tailed P<0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of the RCM findings and final histopathological diagnosis was calculated.

Results

We performed 30 RCM examinations on 29 patients who presented with new areas of pigmentation within or adjacent to scars from prior excision of LM/LMM. One patient presented with a second repigmentation 2 years apart (Supplementary Table 1). Twenty-nine out of thirty lesions (96.6%) were located on the head and neck area: One patient had a lesion on the lower leg. Age at initial diagnosis of melanoma was 64.5 ± 11.2 years (46-86 years). The male:female ratio was 1:1. Mean repigmentation size was 1.75 cm ± 1.2; range 0.5 – 5.0 cm). Eight melanomas (26.7%) were invasive. The median Breslow thickness among invasive melanomas was 0.25 ± 0.35 mm (0.15-1.2 mm). Demographic data are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Clinical features and histopathologic diagnosis

Details of the cohort, by histopathologic diagnosis, are listed in Table 1. All patients presented with pigmented macules within or adjacent to the original scar. Definitive diagnosis of recurrent LM/LMM in areas of pigmentation was histologically confirmed for 21 (70.0%) of the 30 cases. The remaining 9 patients (30.0%) had a non-LM diagnosis: 4 with pigmented actinic keratosis (pAK) and 5 with a background of hyperpigmentation/solar lentigo. Age at recurrence of pigmentation was 71.1 ± 12.0 years among patients with LM/LMM and 70.7 ± 7.0 years among those with other diagnoses (P=0.92). Time to recurrence of pigmentation was 68.1 ± 43.4 months (13-180 months) among LM/LMM patients and 52.4 ± 39.1 months among those with other diagnoses (P=0.36). There was no difference between size and diagnosis (p=0.45).

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical, dermoscopic, and reflectance confocal microscopy characteristics of patients with recurrent pigmentation within a lentigo maligna surgical scar. Data are mean (standard deviation) or proportion (%). Significant P values are in bold type. DEJ = dermoepidermal junction; LM = lentigo maligna; LMM = lentigo maligna melanoma; RCM = reflectance confocal microscopy; SD = standard deviation. *One patient had 2 RCM examinations due to a second repigmentation (first diagnosis was recurrent LM, second diagnosis was solar lentigo; RCM correctly identified the diagnosis in the two occasions).

| Characteristic | Recurrent melanoma (n=21*) |

Other causes of pigmentation (n=9*) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at first diagnosis of LM/LMM, years (SD) | 64.05 (12.1) | 65.7 (9.3) | 0.723 |

| Age at recurrence of pigmentation, years (SD) | 71.1 (12.0) | 70.7 (7.0) | 0.921 |

| Time to recurrence of pigmentation, months (SD) | 68.1 (43.4) | 52.4 (39.2) | 0.362 |

| Male sex (%) | 8/21 (38.1%) | 7/9 (77.7%) | 0.109 |

| Size of repigmentation area, cm (SD) | 1.86 (1.3) | 1.47 (1.1) | 0.45 |

| Dermoscopic findings (n=22*) | |||

| Irregular circles | 4/14 (28.5%) | 1/8 (12.5%) | 0.613 |

| Circles within circles | 2/14 (14.2%) | 1/8 (12.5%) | 0.515 |

| Annular-granular pattern | 2/14 (14.2%) | 0/8 | 0.515 |

| Rhomboids/angulated lines | 2/14 (14.2%) | 0/8 | 0.515 |

| Regression/peppering | 0/14 (0%) | 1/8 (12.5%) | 0.364 |

| Homogeneous or structureless brown areas | 13/14 (92.8%) | 3/8 (37.5%) | 0.009 |

| Scale | 0/14 | 1/8 (12.5%) | 0.364 |

| Pseudonetwork | 0/14 | 2/8 (25%) | 0.121 |

| Fingerprinting | 2/14 (14.2%) | 3/8 (37.5%) | 0.309 |

| Fine network | 3/14 (21.4%) | 0/8 | 0.273 |

| Irregular dots | 1/14 (7.1%) | 0/8 | 1.0 |

| Irregular globules | 1/14 (7.1%) | 0/8 | 1.0 |

| RCM features (n=30*) | |||

| Atypical honeycomb | 9/21 (42.8%) | 4/9 (44.4%) | 1.0 |

| Cobblestone pattern | 7/21 (33.3%) | 8/9 (88.8%) | 0.014 |

| Polycyclic dermal papillae | 3/21 (14.2%) | 5/9 (55.5%) | 0.032 |

| Bright large nucleated cells DEJ/suprabasal epidermis | 20/21 (95.2) | 2/9 (22.2%) | <0.001 |

| Folliculotropism | 18/21 (85.7%) | 1/9 (11.1%) | <0.001 |

| Round cells | 8/21 (38.1%) | 0 | 0.067 |

| Dendritic cells | 18/21 (85.7%) | 2/9 (22.2%) | 0.002 |

| Pleomorphic cells | 8/21 (38.1%) | 0 | 0.067 |

| Atypical cells dermis | 6/21 (28.5%) | 0 | 0.141 |

| Dermal nests | 1/21 (4.7%) | 0 | 1.0 |

| Plump cells | 7/21 (33.3%) | 2/9 (22.2%) | 0.681 |

| Inflammation | 14/21 (66.6%) | 2/9 (22.2%) | 0.046 |

RCM features:

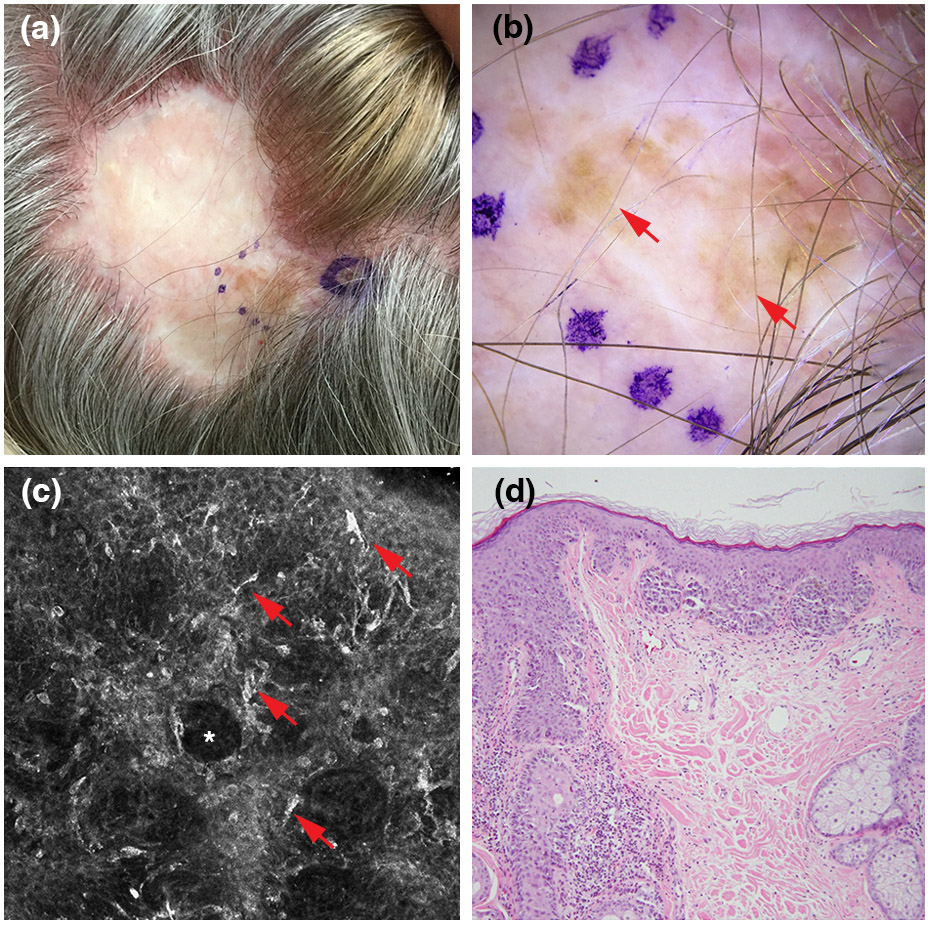

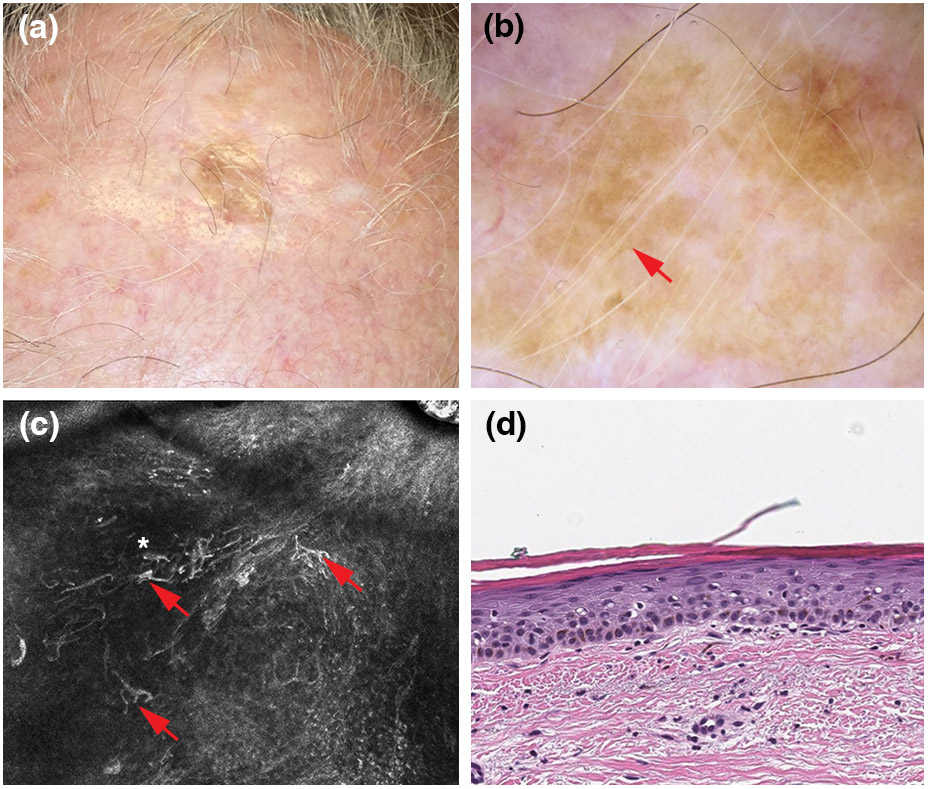

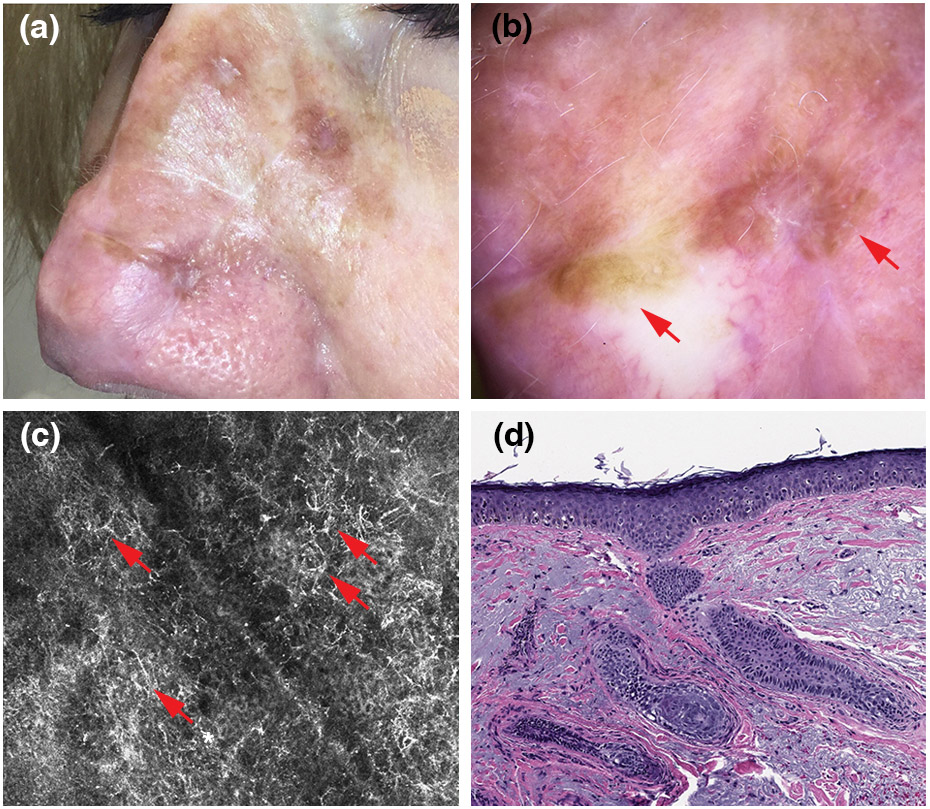

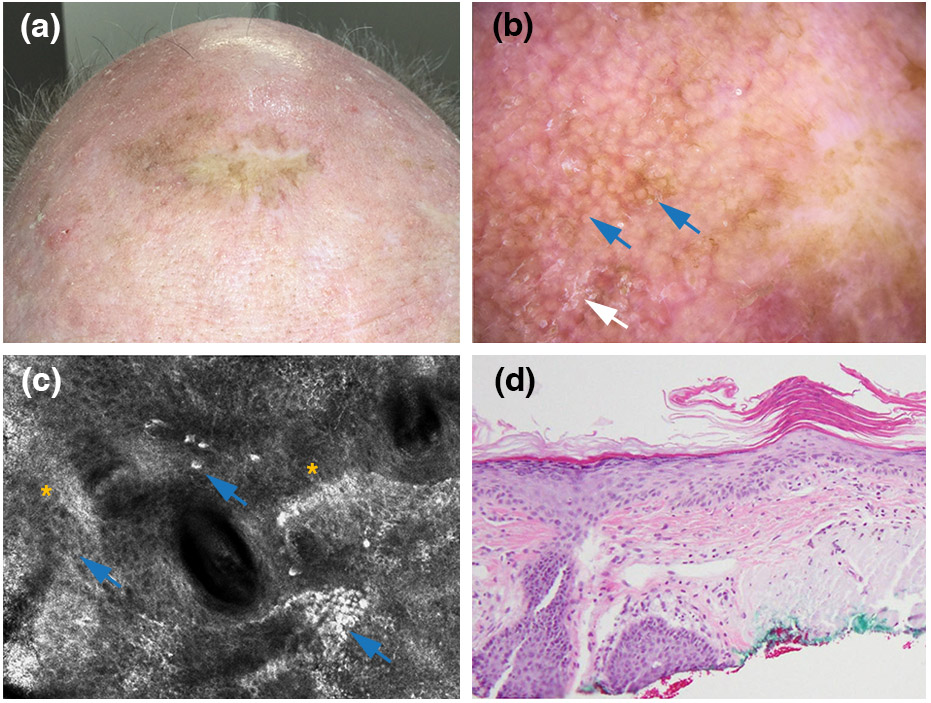

RCM had an overall diagnostic accuracy of 90.0% (95% CI, 73.47%-97.89%) and correctly identified true recurrent LM/LMM from other causes in 20 (95.2%) of 21 cases (Table 1; Figs 1-4). The OR for diagnosis of recurrent LM/LMM with RCM was 70.0 (95% CI, 5.46-896.59) with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.865. RCM had sensitivity of 95.24% (95% CI, 76.18%-99.88%), specificity of 77.7% (95% CI, 39.99%-97.19%), positive predictive value of 90.91% (95% CI, 74.58%-97.15%), and negative predictive value of 87.5% (95% CI, 50.04%-98.0%). On RCM, 20 (95.2%) of the 21 patients with LM/LMM had bright large nucleated cells at the DEJ/suprabasal epidermis (Figures 1 and 2). Of the 9 examinations with other diagnoses, 2 (22.2%; both with pAK) had bright large nucleated cells at the DEJ (P<0.001; Figures 3 and 4). Nucleated cells with folliculotropism were observed in 18 (85.7%) of the 21 cases of LM/LMM and in 1 of the 9 cases of other diagnosis (11.1%) (P<0.001). Of the 9 patients with non-LM/LMM diagnoses, 8 (88.8%) had a cobblestone pattern (P=0.014) and 4 (44.4%) had an atypical honeycomb pattern (P=1.0). Bright nucleated cells above the suprabasal layer were seen more commonly in larger lesions (2.1 cm vs 0.9 cm; p=0.01). No other RCM feature was associated with size of recurrent pigmentation in the recurrent melanoma group (data not shown).

Fig 1.

Recurrent lentigo maligna. (a) Clinical picture showing pigment extends beyond the graft margins. (b) Dermoscopic findings, showing homogeneous or structureless brown areas (red arrows; polarized light dermoscopy; original magnification, 10X). (c) Reflectance confocal microscopy findings, showing round and dendritic bright nucleated cells (red arrows) surrounding hair follicles (white asterisk) (750 x 750 μm). (d) Histopathologically confirmed recurrent lentigo maligna melanoma (Breslow thickness, 0.4 mm; haematoxylin and eosin; magnification, 20X).

Fig 4.

Pigmented actinic keratosis arising within a lentigo maligna surgical scar. (a) Clinical picture showing pigment extends into the grafted area. (b) Dermoscopic findings, showing a structureless brown pattern (red arrow). No scale is seen. (polarized light dermoscopy; original magnification, 10X) (c) Reflectance confocal microscopy findings, displaying bright large nucleated dendritic cells (red arrows) in a disarranged dermoepidermal junction/suprabasal epidermis (white asterisk) (750 x 750 μm). (d) Histopathologically confirmed pigmented actinic keratosis (haematoxylin and eosin; magnification, 20X).

Fig 2.

Recurrent lentigo maligna. (a) Clinical picture showing multiple foci of pigment along the scar of a complex reconstruction site (flap and graft) area on the nose. (b) Dermoscopic findings, showing homogeneous/structureless brown areas (red arrows; polarized light dermoscopy; original magnification, 10X). (c) Reflectance confocal microscopy findings, showing large widespread pagetoid dendritic cells (red arrows; 750 x 750 μm). (d) Histopathologically confirmed recurrent lentigo maligna (red arrow).

Fig 3.

Pigmented actinic keratosis arising within a lentigo maligna surgical scar. (a) Clinical picture showing pigment extends beyond the graft margins. (b) Dermoscopic findings, showing a pseudonetwork (blue arrows) and scale (white arrow) (polarized light dermoscopy; original magnification, 10X). (c) Reflectance confocal microscopy findings, showing pigmented keratinocytes (blue arrows) and an overall atypical honeycomb pattern (yellow asterisks) (750 x 750 μm). (d) Histopathologically confirmed pigmented actinic keratosis (haematoxylin and eosin; magnification, 20X).

Dermoscopic features:

Dermoscopic images were available for 22 (69.2%) of the 26 cases (Table 1). The most common dermoscopic feature in patients with recurrent LM/LMM was ‘focal homogeneous or structureless areas of light-brown pigmentation’ (92.8% vs 37.5% in patients with other diagnoses; P=0.009). LM-specific dermoscopic criteria were present in only 28.6% (4/14) of patients with recurrent LM/LMM (Table 1). Patients with non-LM causes of pigmentation commonly had fingerprinting and a pseudonetwork identified on dermoscopy (37.5% vs 14.2% and 25% vs 0% in patients with LM/LMM, respectively; these results were not statistically significant P=0.309 and 0.121). No dermoscopic feature was associated with size of recurrent pigmentation in the recurrent melanoma group (data not shown).

Discussion:

Evaluation of new areas of pigmentation within or adjacent to surgically excised LM/LMM scars can be challenging. The differential diagnosis includes lentigines, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, pAK, and melanoma recurrence. Poikilodermatous changes within the scar often contribute to the diagnostic confusion. Until recently, the decision to biopsy an area of repigmentation within or adjacent to an LM/LMM scar has commonly been based on clinical suspicion, with or without the aid of dermoscopy. Dermoscopy was of limited benefit in our cohort. In two-thirds of cases, only a homogeneous or structureless light-brown pigment, without any melanoma-specific structures, was identifiable under dermoscopy. In contrast, positive findings on RCM were strongly associated (OR, 70.0) with the final histopathologic diagnosis, confirming that RCM may play a role in differentiating recurrent LM/LMM from other causes of pigmentation. Scar tissue did not appear to hinder the detection of recurrent LM/LMM by RCM: The sensitivity and specificity for detecting recurrent LM/LMM associated with scars in this cohort was similar to previous studies assessing LM/LMM with no associated scars.7,11,16

Recurrence appears to be a late phenomenon in patients with LM/LMM, as it can occur 5 to 10 years after initial surgery.3,6,17 We observed a mean time to recurrence of repigmentation of 5.6 years, with 1 patient experiencing a melanoma recurrence 16 years after initial treatment.18 The mean age at recurrence was 71.1 years; these patients have a long-life expectancy, and the management of recurrent melanoma is complex. RCM and dermoscopy can be used as complementary tools for surveillance in cases where recurrence is suspected.

Previous studies evaluating RCM features in patients with recurrent LM after surgery have included 1 case report9 and 1 small case-series.17 Guitera et al.14 demonstrated that RCM is a useful tool to detect treatment failure after nonsurgical therapies (e.g., radiotherapy, imiquimod), with sensitivity of 94% and specificity of 100%. Our results are similar to those of a prospective study evaluating RCM for the diagnosis of flat facial lesions that included LM/LMM, which found an overall sensitivity of 95% and specificity of 82%.16 Additionally, a study by Cinotti et al included 17 recurrent LM/LMM in a series of 223 facial lesions. They compared recurrent LM to any pigmented facial macules arising on normal skin as controls and found a sensitivity of 75% and a specificity of 46%.10 Our comparison group, however, included repigmentation arising on/within scars and not pigmented facial macules arising on normal skin. Overall, these studies highlight that evaluation of recurrent lesions arising within scars may be complex.

Additionally, RCM can be used to select the optimal biopsy site within the scar. Selecting the optimal biopsy site in large areas of pigmentation may be challenging and can lead to false-negative results due to sampling error. Many of our patients presented with complex prior reconstructions (e.g., flaps, grafts) at the surgery site and/or large lesions that were commonly located on highly cosmetic and functional areas—evaluation of these sites may be difficult by the naked eye alone. RCM can be used to scout large lesional areas and select the site with the most concerning features for biopsy. This was highlighted by Mataca et al., they found that RCM could be used to select biopsy sites containing more LM histopathologic criteria in comparison to those identified by the naked eye.19

We identified ‘homogeneous or structureless light-brown areas of pigmentation’ as an important dermoscopic feature for the diagnosis of recurrent LM/LMM. Interestingly, more than two-thirds of cases in our cohort lacked classical dermoscopic criteria for LM/LMM.8 We hypothesize that this homogeneous or structureless light-brown pigmentation occurs because of a lentiginous proliferation of pigmented melanocytes in an epidermis with attenuated rete ridges and few adnexal openings, possibly due to previous inflammation and scarring. Most of the classic LM/LMM-specific features are related to the hair follicles (e.g., asymmetrical follicular openings, circles within circles, angulated lines, rhomboid structures); however, in patients with scar tissue (which is nearly devoid of hair follicles) from previous treatment of LM/LMM, melanoma-specific features would not be apparent on dermoscopy. It is important to recognize diffuse structureless pigmentation as a common feature seen under dermoscopy, and not to expect the classic dermoscopic features of facial melanoma to avoid missing a recurrent LM/LMM. In a previous study of 5 cases of recurrent LM analysed by dermoscopy, “diffuse pigmentation” was identified in 4 (80%) cases, and only 1 had melanoma-specific criteria.17 Cinotti et al. reported a sensitivity of 61% and specificity of 92% for detection of LM by dermoscopy; however, the sensitivity and specificity of dermoscopy decreased to 55% and 56% for recurrent LM, respectively.10 This underscores the limitations and lack of specificity of dermoscopy for detecting recurrent LM/LMM. Diffuse homogeneous light-brown pigmentation was not exclusively seen in melanomas, as it was associated with other lesions arising in a previous scar. This pigmentation was seen in 3 of our cases with other causes of pigmentation (Figure 4).

False negatives and false positives under RCM:

RCM had sensitivity of ~95% in our study. One case of recurrent melanoma was misclassified as non-LM (false-negative) by RCM: a 51-year-old woman who presented to our clinic with a recurrent pigmentation appearing on a previously treated 0.3-mm LMM on the neck. The recurrence occurred 54 months after the initial surgery. RCM examination revealed only diffuse inflammatory cells as bright dots and plump cells. On further review, one or two isolated large dendritic cells were observed at the DEJ in the periphery; however, no round or dendritic bright large cells with perifollicular distribution were seen. Histopathologic analysis revealed an early recurrent LM. Dermoscopy showed a homogeneous brown pigmented area that, on the basis of our results, should prompt a biopsy. In such cases, RCM and dermoscopy should be used as complementary tools.

In our study, the most common cause of misclassification of cases as false-positives by RCM was pAK: 2 cases of pAK fulfilled the criteria for LM on RCM described by Guitera et al. (Figure 4).7 pAK is considered by many to be one of the most challenging differentials of LM/LMM by both dermoscopy20 and confocal microscopy.21,22 pAKs have been previously shown to display large dendritic cells under RCM in a similar manner to LM/LMM, with a specificity of only 53% in nonsurgically treated sites, making their differentiation challenging.22,23 Accordingly, when the RCM differential includes these two diagnoses in a previously treated LM/LMM, we suggest performing a biopsy to avoid missing a melanoma. In our study, only 1 case of pAK had folliculotropism. As suggested by Persechino et al., presence of folliculotropism may help to distinguish the two diagnoses.22 In the same study, atypical honeycomb pattern was not a reliable criterion for differentiation between LM/LMM and AK. In our series, atypical honeycomb was seen similarly in both groups (~40%; p=1.0). The diagnostic challenge in differentiating pAK and solar lentigo from a true melanoma recurrence is not limited to RCM, as differentiation on histopathologic analysis can also be challenging.22,24 It could be that RCM is able to detect subtle repigmentation earlier, thus adding to the number of false-positives.

Limitations

This was a retrospective study from a tertiary cancer center: Our population tends to be biased toward more-complex cases, and hence, our cohort included a higher proportion of recurrent melanomas than benign cases of scar repigmentation. It is possible that in a less complex setting, the proportion of benign causes of pigmentation may be higher. This is important since pAK may be confused with LM clinically, dermoscopically, and under RCM, and further studies on larger numbers of cases are required to better understand the differences between pAK and LM in association with scars.23,25 In addition, we had a relatively small sample size; however, to the best of our knowledge, this is the largest study to evaluate the use of RCM for recurrent melanoma after surgery to date. This is a rare and complicated scenario; as such, our results could help improve management of these complex cases. Finally, there was no correlation with the level of follicular involvement (i.e. infundibulum, isthmus); future studies should consider stratifying the level of involvement to correlate different RCM patterns given the frequent follicular involvement seen in LM.26

Conclusions

Recurrent LM/LMM often present with homogeneous or structureless light-brown pigmentation devoid of melanoma-specific structures on dermoscopy. RCM can help identify true recurrent LM/LMM on the basis of the presence of bright large nucleated cells at the DEJ/suprabasal epidermis with perifollicular localization. RCM can also assist in selecting the optimal area to biopsy with the highest likelihood of containing histopathologic features of LM. When faced with evaluating these diagnostically challenging cases, dermoscopy and RCM should be used as complementary tools.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

David B. Sewell, of the Memorial Sloan Kettering Department of Surgery, provided editorial assistance.

Funding source:This research was funded, in part, by National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748. The funder played no role in any aspect of the study.

Footnotes

Disclosures:

A. A. Marghoob: Received honorarium from 3GEN for dermoscopy lectures, royalties from publishing companies for books and book chapters, dermoscopy equipment for testing and feedback, and payment from the American Dermoscopy Meeting for organizing and lecturing at the annual meeting.

A. Rossi: Dr. Rossi has no relevant conflicts of interest related to this manuscript but has received grant funding from The Skin Cancer Foundation and the A.Ward Ford Memorial Grant for research related to this work. He also served on advisory board, as a consultant, or given educational presentations: for Allergan, Inc; Galderma Inc; Evolus Inc; Elekta; Biofrontera, Quantia; Merz Inc; Dynamed; Skinuvia, Perf-Action, and LAM therapeutics.

References

- 1.Fosko SW, Navarrete-Dechent CP, Nehal KS. Lentigo Maligna-Challenges, Observations, Imiquimod, Confocal Microscopy, and Personalized Treatment. JAMA Dermatol. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Osborne JE, Hutchinson PE. A follow-up study to investigate the efficacy of initial treatment of lentigo maligna with surgical excision. Br J Plast Surg. 2002;55(8):611–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Connolly KL, Nijhawan RI, Dusza SW, Busam KJ, Nehal KS. Time to local recurrence of lentigo maligna: Implications for future studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(6):1247–1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hazan C, Dusza SW, Delgado R, Busam KJ, Halpern AC, Nehal KS. Staged excision for lentigo maligna and lentigo maligna melanoma: A retrospective analysis of 117 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(1):142–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kunishige JH, Brodland DG, Zitelli JA. Surgical margins for melanoma in situ. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(3):438–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Connolly KL, Hibler BP, Lee EH, Rossi AM, Busam KJ, Nehal KS. Locally Recurrent Lentigo Maligna and Lentigo Maligna Melanoma: Characteristics and Time to Recurrence After Surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43(6):792–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guitera P, Pellacani G, Crotty KA, et al. The impact of in vivo reflectance confocal microscopy on the diagnostic accuracy of lentigo maligna and equivocal pigmented and nonpigmented macules of the face. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130(8):2080–2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schiffner R, Schiffner-Rohe J, Vogt T, et al. Improvement of early recognition of lentigo maligna using dermatoscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(1 Pt 1):25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Longo C, Moscarella E, Pepe P, et al. Confocal microscopy of recurrent naevi and recurrent melanomas: a retrospective morphological study. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165(1):61–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guitera P, Haydu LE, Menzies SW, et al. Surveillance for treatment failure of lentigo maligna with dermoscopy and in vivo confocal microscopy: new descriptors. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170(6):1305–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cinotti E, Labeille B, Debarbieux S, et al. Dermoscopy vs. reflectance confocal microscopy for the diagnosis of lentigo maligna. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marino ML, Rogers T, Sierra Gil H, Rajadhyaksha M, Cordova MA, Marghoob AA. Improving lesion localization when imaging with handheld reflectance confocal microscope. Skin Res Technol. 2016;22(4):519–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Segura S, Puig S, Carrera C, Palou J, Malvehy J. Development of a two-step method for the diagnosis of melanoma by reflectance confocal microscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61(2):216–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guitera P, Menzies SW, Longo C, Cesinaro AM, Scolyer RA, Pellacani G. In vivo confocal microscopy for diagnosis of melanoma and basal cell carcinoma using a two-step method: analysis of 710 consecutive clinically equivocal cases. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132(10):2386–2394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kittler H, Marghoob AA, Argenziano G, et al. Standardization of terminology in dermoscopy/dermatoscopy: Results of the third consensus conference of the International Society of Dermoscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(6):1093–1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wurm E, Pellacani G, Longo C, et al. The value of reflectance confocal microscopy in diagnosis of flat pigmented facial lesions: a prospective study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(8):1349–1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Erfan N, Kang HY, Cardot-Leccia N, et al. Reflectance confocal microscopy for recurrent lentigo maligna. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37(10):1519–1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donigan JM, Hyde MA, Goldgar DE, Hadley ML, Bowling M, Bowen GM. Rate of Recurrence of Lentigo Maligna Treated With Off-Label Neoadjuvant Topical Imiquimod, 5%, Cream Prior to Conservatively Staged Excision. JAMA Dermatol. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mataca E, Migaldi M, Cesinaro AM. Impact of Dermoscopy and Reflectance Confocal Microscopy on the Histopathologic Diagnosis of Lentigo Maligna/Lentigo Maligna Melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akay BN, Kocyigit P, Heper AO, Erdem C. Dermatoscopy of flat pigmented facial lesions: diagnostic challenge between pigmented actinic keratosis and lentigo maligna. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163(6):1212–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Carvalho N, Farnetani F, Ciardo S, et al. Reflectance confocal microscopy correlates of dermoscopic patterns of facial lesions help to discriminate lentigo maligna from pigmented nonmelanocytic macules. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173(1):128–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Persechino F, De Carvalho N, Ciardo S, et al. Folliculotropism in pigmented facial macules: Differential diagnosis with reflectance confocal microscopy. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27(3):227–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moscarella E, Rabinovitz H, Zalaudek I, et al. Dermoscopy and reflectance confocal microscopy of pigmented actinic keratoses: a morphological study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(2):307–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farrahi F, Egbert BM, Swetter SM. Histologic similarities between lentigo maligna and dysplastic nevus: importance of clinicopathologic distinction. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32(6):405–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen LM. The starburst giant cell is useful for distinguishing lentigo maligna from photodamaged skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(6):962–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Connolly KL, Giordano C, Dusza S, Busam KJ, Nehal K. Follicular involvement is frequent in lentigo maligna: Implications for treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(2):532–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.