Abstract

The neuronal control of the immune system is fundamental to the development of new therapeutic strategies for inflammatory disorders. Recent studies reported that afferent vagal stimulation attenuates peripheral inflammation by activating specific sympathetic central and peripheral networks, but only few subcortical brain areas were investigated. In the present study, we report that afferent vagal stimulation also activates specific cortical areas, as the parietal and cingulate cortex. Since these cortical structures innervate sympathetic-related areas, we investigate whether electrical stimulation of parietal cortex can attenuate knee joint inflammation in non-anesthetized rats. Our results show that cortical stimulation in rats increased sympathetic activity and improved joint inflammatory parameters, such as local neutrophil infiltration and pro-inflammatory cytokine levels, without causing behavioral disturbance, brain epileptiform activity or neural damage. In addition, we superposed the areas activated by afferent vagal or cortical stimulation to map common central structures to depict a brain immunological homunculus that can allow novel therapeutic approaches against inflammatory joint diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis.

Keywords: Joint inflammation, Cortical stimulation, Vagus nerve, Neuro-immune interactions, Immunological homunculus

1. Introduction

Joint pain is one of the most common disabling factors in articular inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (Upchurch & Kay, 2012), that can lead to cognitive impairments as anxiety, depression and suicide contributing to arthritic morbidity and mortality (Boyden et al., 2016; Hewlett et al., 2011). There is no cure for rheumatoid arthritis and current clinical treatments are based on the use of disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) that neutralize cytokines (e.g. tumor necrosis factor; TNF) inhibiting activation of leucocytes such as neutrophils (Edrees et al., 2005; Mantovani et al., 2011; Inui and Koike, 2016). Neutrophils are critical for the innate immunity to eliminate microorganisms producing microbicide mediators, but when unregulated, they can cause tissue injury as observed in the joints of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Chronic DMARDs usage causes undesirable side effects, such as systemic immunosuppression, opportunistic infections and malignancies (Favalli et al., 2009). Studies showed that neural stimulation could induce therapeutic advantages by controlling local inflammation in arthritic disorders without provoking systemic side effects (Levine, 1978; Bassi et al., 2015, 2017).

The regulation of the innate immunity by the sympathetic nervous system has been well studied (Elenkov, 1995; Kenney and Ganta, 2011). More recent studies also report the potential of the parasympathetic nervous system to control inflammation (Ulloa and Deitch, 2009; Pavlov and Tracey, 2015). In fact, vagal stimulation has received special attention due to its ability to control the innate immune system and to inhibit systemic inflammation in multiple experimental models, from sepsis to rheumatoid arthritis (Ulloa and Deitch, 2009; Levine et al., 2014; Koopman et al., 2016; Bassi et al., 2017). Anatomical studies indicate that vagal stimulation inhibits systemic TNF levels in experimental sepsis through two peripheral neuroimmune mechanisms: First, vagal stimulation inhibits splenic TNF production in experimental sepsis by activating the sympathetic splenic nerve and inducing neurogenic norepinephrine in the spleen (Rosas-Ballina et al., 2011; Olofsson et al., 2012). Second, vagal stimulation inhibits systemic inflammation in experimental sepsis by inducing the production of dopamine in the adrenal medulla (Torres-Rosas et al., 2014). In addition to these efferent pathways, recent studies also suggested a third mechanism where vagal afferent stimulation must activate central neuronal networks controlling peripheral inflammation (Bratton et al., 2012; Martelli et al., 2014; Bassi et al., 2015; Inoue et al., 2016; Abe et al., 2017; Willemze et al., 2017). We recently reported that vagal stimulation attenuates arthritic joint inflammation through an afferent pathway toward the central nervous system that induces local sympathetic production of norepinephrine in the joints (Bassi et al., 2017). This vagal afferent mechanism required the integrity of the locus coeruleus (LC), a sympathomodulatory structure in the brain, showing, for the first time, the existence of specific inflammatory processing brain centers that can control peripheral inflammation in arthritis (Bassi et al., 2017). In addition to the LC, vagal afferent activity is well known to modulate other critical somatosensory and autonomic areas localized in the lower and upper brainstem, diencephalon and cerebral hemispheres toward direct and indirect polysynaptic connections originated in central vagal nuclei (such as the nucleus of the solitary tract and the dorsomedial nucleus) (Saper and Loewy, 1980; Rutecki, 1990; Guyenet, 1991; Ruggiero et al., 2000; Buller, 2003; Saper, 2011). These connections suggest the existence of other brain immunomodulatory centers that can contribute to the anti-inflammatory effects of the afferent vagal stimulation and inhibit inflammation in arthritic joints without inducing systemic side effects. In the current study, we show that vagal stimulation induced c-Fos expression (a neuronal activity marker) in several brain areas including the parietal cortex. Furthermore, specific stimulation of the parietal cortex inhibits inflammation in arthritic joints without inducing systemic anti-inflammatory side effects. We propose an inflammatory central processing map that includes brain areas activated by both vagal and cortical stimulations that can have immunomodulatory functions, with clinical implications for treating rheumatoid arthritis.

2. Methods

2.1. Animal experiments

Male Wistar rats (250–300 g) were obtained from the main Animal Facility of the Ribeirão Preto Medical School, University of São Paulo, and housed upon arrival at the animal facility in plastic cages under a 12-h light/dark cycle (lights ON at 7 am) at 20 °C ± 1 °C. The animals had unrestricted access to food and drinking water. The number of animals used was the minimum required to ensure reliability of the results, and every effort was made to minimize animal discomfort. All animals were anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine and xylazine (50 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg, respectively) administered into the right posterior calf muscle through a 30G needle. The experimental protocols comply with the recommendations of the SBNeC (Brazilian Society of Neuroscience and Behavior), the Ethical Principles of the Brazilian College of Animal Experimentation (COBEA Protocols 137/2013, 189/2015) and the US National Institutes of Health Guide for The Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

2.2. Surgical procedures

After the confirmation of anesthesia by the lack of response to a foot pinch and corneal reflex, rats were maintained in supine position on a heated pad, and a medial laparotomy was performed, and one of the following surgical procedures was used: for splenectomy (SPX), the spleen was visualized, exposed and then removed after ligation of all splenic blood vessels; in subdiaphragmatic vagotomy (sVNX), the posterior wall of the oesophagus was visualized to find the posterior vagal branch, which was followed until its exit from the oesophageal hiatus, and then 1 to 2 mm length of the nerve was removed; for sympathectomy (SYMPX), the right lumbar sympathetic ganglia (L2–L3 level) were dissected near the renal artery, the L5 ganglion was identified at the level of aorta bifurcation, and all pathways connecting L2 to L5 were excised as we previously described in Bassi et al. (2017); adrenalectomy (ADX) was performed after bilateral dorsal incision followed by visualization of the kidneys, and both adrenal glands were removed. Adrenalectomized animals had free access to 0.9% NaCl to avoid body electrolyte loss. After each surgery, the wounds were carefully closed with sutures using nylon thread. Experiments were performed 7–10 days after the surgeries.

2.3. Zymosan-induced arthritis

Fifty microliters of zymosan suspension (100 μg) in sterile saline (0.9% NaCl; vehicle) were injected into the femorotibial joint (intra-articular; i.a.) of both knees (Keystone et al., 1977; Gegout et al., 1994). Joint experimental score was assessed as follows: 0 = no evidence of inflammation; 1 = edema of the femorotibial cavity (slight edema); 2 = edema involving all joint capsule surrounding the knee (large edema); 3 = the same as 2 plus small hemorrhagic spots along the synovial bursa; 4 = the same as 2 plus large hemorrhagic spots or blood/pus leakage (Bassi et al., 2015, 2017). Joint diameter was measured by a caliper in millimeters (mm). Knee neutrophil recruitment, animals were killed by decapitation and then the knee joint was opened and washed with saline solution containing EDTA (1 mM). Synovial cavities were then opened, washed with a mixture of PBS/EDTA by a micropipette, diluted (1:5) and the total number of leukocytes was determined by means of Neubauer chamber using an optical microscope (400×). The results are depicted as neutrophils/joint cavity.

2.4. Vagal stimulation in anesthetized animals

Rats were anesthetized and maintained in supine position. A midline cervical incision was performed and the right carotid artery was identified. The vagus nerve was carefully dissected from the right carotid artery and bipolar stainless steel electrodes were connected to the stimulation device (MP150, Biopac Systems, Santa Barbara, CA, USA) was placed across the nerve trunk. The right vagus nerve has been chosen by our group because it is consistently more sensitive to electrical stimulation than the left vagus nerve (Hotta et al., 2009). After the end of the stimulation (5 Hz, 0.1ms, 1 V), the electrode was removed and wounds were closed with sutures. In the afferent vagal stimulation group, the right vagus nerve was carefully identified and cut near the sternocleidomastoid muscle and the wounds were closed with sutures. Twenty-four hours later, the animal was re-anesthetized and the proximal end of the right vagus nerve was then carefully identified and a bipolar stainless steel electrode was placed across the afferent nerve trunk. Electrical stimulation of the vagus nerve (VNS) was delivered for 2 min and only animals presenting noticeable reduced breath rate were considered for the experiment. After the end of the stimulation, the electrode was removed and wounds were closed with sutures. The sham group underwent similar surgical procedures but was not subjected to electrical stimulation of the vagus nerve.

2.5. Vagus nerve stimulation in unanesthetized rats

Anesthetized rats were maintained in supine position and the right vagus nerve was carefully dissected from the carotid artery through a ventral approach. Briefly, bipolar stainless steel electrodes were implanted around the vagus nerve and exteriorized through the sternocleidomastoid muscle in the nape of the neck. Next, both electrode and nerve trunk were covered with silicone (Kwik-Sil silicone elastomer; World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, USA). After silicone polymerization, the wounds were closed with sutures. Flunixin meglumine (Banamine, 25 mg/kg, subcutaneous; Schering-Plough, Cotia, SP, Brazil) was injected immediately after the end of surgery. Twenty-four hours later, the animals were individually placed in a circular arena (Ø 37 cm; 50 cm high) in a quiet environment to avoid stress. Vagal electrodes were connected to an external electrical stimulator (1M1C; AVS Projetos, São Carlos, SP, Brazil) and a period of 10 min of free locomotion and exploration was allowed. After this period, rats were subjected to 2 min of vagus nerve stimulation (5 Hz; 0.1 ms; 1 V). This VNS parameter has been chosen by our group because it has anti-inflammatory properties without causing significant cardiovascular alterations (Bassi et al., 2017). Vagal stimulation was confirmed by reduced breath rate and a more steady state behaviour (lack of locomotion, exploration or freezing) that was restored immediately after the end of the stimulation. Five minutes after the stimulation the animals were exposed to the Elevated Plus-Maze test (EPM), an experimental tool to evaluate anxiety (File et al., 2001). Twenty-four hours after the behavioral experiment, the animals were re-stimulated for the c-Fos experiment. In the sham group, the electrodes were implanted around the right vagus nerve and exteriorized in the nape of the neck, but no electrical current was delivered.

2.6. Stereotaxic surgery

Naïve Wistar rats were anesthetized and placed in a stereotaxic frame (David Kopf, Tujunga, CA, USA) for implantation of the screws (stainless steel screw, Ø 1.5 mm; Fine Science Tools, Heidelberg, Germany) and electrode (stainless-steel teflon-isolated microwire; Ø 127 μm; A-M Systems, Sequim, WA, USA). On the left parietal cortex (anteroposterior = 2.7 mm, mediolateral = 5.0 mm, dorsoventral = duramater contact) was implanted a stainless steel screw that served as a stimulation electrode, and in the same contralateral area another stainless steel screw was fixed and used as a recording eletrode. In addition, one bipolar recording electrode was implanted in the left hippocampus (anteroposterior: −6.3 mm, mediolateral = 4.5 mm, dorsoventral = 4.5 mm) and a stainless steel screw was implanted in the frontal bone and welded to a tiny wire to serve as the ground electrode. In other group of animals, an additional tripolar electrode for recording and stimulus (double function) in the left basolateral amygdala (anteroposterior: 6.7 mm, mediolateral = 4.7 mm, dorsoventral = 7.1 mm) was implanted to serve as control group. The frontal bone screw was welded to a tiny wire to serve as the ground and two stainless steel support screws were fixed. All recording and stimulus were monopolar electrodes and their coordinates extracted from the Rat Brain Atlas (Paxinos and Watson, 2007). The screws and electrode were then welded to a RJ11cat6 male plug and fixed to the skull by acrylic resin. At the end of surgery each animal received an intramuscular injection (0.2 mL) of veterinary antibiotic (Pentabiótico, 0.2 mL; Fort Dodge, Campinas, SP, Brazil), followed by an injection of the anti-inflammatory and analgesic banamine (Flunixin Meglumine, 2.5 mg/kg, Schering-Plough, Cotia, SP, Brazil).

2.7. Cortex stimulation in unanesthetized rats

Seven to ten days after the stereotaxic surgery, the animals were individually placed in a circular arena (Ø 37 cm; 50 cm high) and the stimulation cable was connected to the electrodes. A quiet environment was maintained to avoid stress and 10 min period of free locomotion and exploration were allowed to the animals. Brain cortex was electrically stimulated for 2 min by means of a sinusoidal wave stimulator (60 Hz, 0.1 ms, 50 μA) (Reis et al., 2010) continuously monitored by an oscilloscope connected to a 1 kΩ resistor in line to the electrodes. None of the stimulated animals presented alertness, freezing, escape or seizure behaviors during the stimulation. Five minutes after the stimulation the animals were exposed to the EPM. Twenty-four hours after the behavioral experiment, the animals underwent immunological experiments. The sham group underwent similar stereotaxic surgery but no electrical current was delivered.

2.8. Temperature measurement in unanesthetized rats

Tail temperature was measured with a thermal camera (Multi-Purpose Thermal Imager IRI 4010; InfraRed Integrated Systems Ltd. Park Circle, Tithe Barn Way Swan Valley Northampton, UK), placed 50 cm above the animal’s tail, and was plotted as the mean of three measurements recorded at different points throughout the length of the tail. The experiments were conducted in a room kept at 26 ± 1 °C, which is the thermoneutral zone for rats (Gordon, 1990).

2.9. Video and electroencephalogram recording and analysis

To ensure that during cortical electrical stimulation (CES) no aberrant neuronal (epileptiform) activity was produced in cortical or subcortical structures, monopolar electroencephalogram (EEG) recordings of the electrical activity of the ipsilateral hippocampus and contralateral cerebral cortex were analyzed. Each animal was placed individually in an acrylic box (Ø 37 cm; 50 cm high) with a metallic shielded cage (Faraday) and connected to the system through an electric plug (RJ11cat6) in a quiet environment. After 10 min of free exploration, the monophasic cathodic electrical stimulus (60 Hz, 0.1 ms, 50 μA) was applied by 2 min. The EEG was captured using the two channels signal conditioner (CyberAmp 320; Axon Instruments, Union City, CA, USA) coupled to an analog-to-digital interface (PowerLab 3.80; ADInstruments, Bella Vista, Australia). The EEG acquisition parameters were as follow: AC recording, band pass from 0.1 Hz to 1 kHz, total gain of 1000×, and sampling rate of 2 kHz. A video camera (Panasonic, Kadoma, Japan) was used to help coupling the observable animal behaviour (exploration, grooming, locomotion, and eventually abnormal or seizure patterns) in synchrony with the EEG activity. Temporal EEG analysis was digitally made from 0 to 100 Hz and expressed in a power scale in dB, using the software LabChart Pro 8.0 (ADInstruments, Bella Vista, Australia). Visual analysis of wave amplitude, frequency, morphology and eventual primary and secondary recurrent afterdischarges (markers of epileptiform activity) were analyzed similarly to Reis et al. (2010). The EEG patterns were correlated to the animal behaviour before and after the CES. For the positive control of induction of EEG epileptiform activity, the parameters of stimulation for rapid amygdala kindling were: biphasic electrical constant current with intensity of 500 μA (60 Hz, 2 ms) during 10 s (Ebert and Loscher, 1995; Foresti et al., 2008). The electrophysiological signals were recorded 1 min before and 5 min after 1st stimulus for hippocampus and amygdala, respectively. The parameters used for recording were the same. For both recordings (CES and rapid amygdala kindling) spectral analysis were made, including comparisons of amplitudes of EEG signal over the distribution of the frequencies, before and after the stimulus. For the CES, the quantification of the total power (mV2) of the electrographic signal was performed through routine for power spectrum density in order to compare pre-stimulation and post-stimulation EEG epochs (5 min each) in hippocampus and cortex.

2.10. Behavior analysis in the EPM Test

To evaluate whether the electrical stimulation procedures produce anxiety-like behaviors, rats were tested in the EPM 5 min after the end of the VNS or CES. The EPM was made of wood and had two open arms (50 × 10 cm) perpendicular to two enclosed arms of the same size with 50-cm-high walls, with the exception of the central part (10 × 10 cm), where the arms crossed. The apparatus was elevated 50 cm above the floor (File et al., 2001). The behavior of the animals was analyzed using a video camera positioned 100 cm above the maze. An arm entry or exit was defined as all four paws entering or exiting an arm, respectively. These data were used to calculate the percentage of open arm entries and percentage of time spent in the open arms. The following complementary ethological parameters were also analyzed: stretched-attend posture (when the animal stretched to its full length with the forepaws, keeping the hind paws in the same place and turning its back to the anterior position), flat-back approach (locomotion when the animal stretched to its full length and cautiously moved forward), head dipping (dipping the head below the level of the maze floor), and endarm exploration (the number of times the rat reached the end of an open arm) (File et al., 2001; Anseloni and Brandão, 1997). The signal was relayed to a monitor in another room via a closed-circuit television camera to discriminate all forms of behavior. Luminosity at the level of the open arms of the EPM was 20 lx. A total of 5 min of free locomotion and exploration of the maze was allowed. The maze was cleaned thoroughly after each test using damp and dry cloths.

2.11. C-Fos immunolabeling

Twenty four hours after the EPM test and one and a half hours after new vagal or cortical stimulation (see Supplementary Fig. 1B), animals were anesthetized and perfused with 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M PBS. Brains were removed and immersed for 5 h in paraformaldehyde and then stored for 72 h in 40% sucrose in 0.1 M PBS for cryoprotection. The brains were sliced (35 μm) in a cryostat (−20 °C) and collected in 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4) and subsequently processed under free-floating technique using the Vectastain ABC Elite peroxidase rabbit IgG kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). All reactions were performed under agitation at 23 ± 1 °C. The sections were first incubated with 1% H2O2 for 10 min and washed three times with 0.1 M PBS (5 min each). Brain sections were then incubated with 0.1 M PBS enriched with 0.1 M glycine, washed three times with 0.1 M PBS (5 min each), and incubated with 0.1 M PBS enriched with 0.2% Triton-X and 1% bovine serum albumin (PBS + ) for 1 h. After three washes, the sections were incubated overnight with primary Fos rabbit polyclonal IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) at a concentration of 1:1000 (coronal sections) or 1:800 (sagittal sections) in PBS +. Sections were again washed three times (5 min each) with 0.1 M PBS and incubated for 1 h with secondary biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG (H + L; Vectastain, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) at a concentration of 1:400 in PBS +. After another series of three 5 min washes in 0.1 M PBS, the sections were incubated for 1 h with the avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (A and B solution of the kit ABC, Vectastain, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) in 0.1 M PBS at a concentration of 1:200 in 0.1 M PBS and again washed three times in 0.1 M PBS (5 min each). Fos immunoreactivity was revealed by the addition of the chromogen 3,3′-di-aminobenzidine (DAB) (0.02%; Sigma, Saint Louis, MO, USA) to which H2O2 (0.04%) was added before use. Finally, tissue sections were washed twice with 0.1 M PBS, mounted on gelatin-coated slides, dehydrated and cover slipped. Fos-positive (Fos + ) neurons were visualized under bright-field microscopy as a brown reaction product inside the nuclei. Tissue sections were observed under light microscope (DMI6000b; Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). Darker objects with areas between 10 and 80 μm2 were identified and automatically counted by a computerized image analysis system (Fiji; www.fiji.sc). Areas with the same shape and size comprising representative parts of each brain region were used for all rats, and counting of Fos + neurons was performed under a 10× objective. Fos + cells were bilaterally counted in each brain region by a researcher blind to the experimental groups. Nuclei were counted individually and expressed as mean number of Fos + cells per nuclei.

2.12. C-Fos pattern of expression from vagal and cortical stimulated brain sections

After c-Fos quantification of both VNS and CES brain sections the photomicrographs were processed with a photo-editor image software (Photoshop CS6). The images were first desaturated and then the background was carefully removed equally in all sections by adjusting image levels to allow only the visualization of the c-Fos immunolabeling as black spots. The VNS and CES c-Fos immunolabeling was filled with green and red color, respectively. Therefore, similar brain sections were digitally merged and their color contrast was increased. Similar overlaid areas were identified by an orange color (digital co-localization).

2.13. C-Fos semi-quantitative analysis from VNS and CES brain sections

Sections were examined using light microscopy and the number of c-Fos + cells was counted and scored by the same observer based on an intensity scale of 0 to + + + compared to the control (naïve) group: 0 = no difference; +: small difference (≤ 10%); ++: medium difference (>10 and ≤30%); + + +: large difference (> 30%).

2.14. Evaluation of GFAP, ATF3 and Fluoro Jade positive (FJ+) neurons

Forty eight hours after the CES, the animals were perfused and their brains were cut as for the c-Fos immunolabeling protocol. The brain sections were then washed 3 times in PBS (0.01M, pH 7.4) 3 times for 5min each and incubated in 5% normal goat serum and 1% BSA dissolved in PBS with 0.1% Triton × 100 (PBS-T) for 1h. Subsequently, the sections were washed in PBS-T (0.01 M, pH 7.4) 3 times for 5 min and then subjected to immunofluorescence staining with overnight incubation at 4 °C with polyclonal anti-ATF3 (1:1000; catalog # sc-188; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) or anti-GFAP (1:1000; catalog # sc-9065, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). As a control, primary antibodies were omitted from the reaction. After incubation with the primary antibodies, the sections were washed in PBS-T 3 times over 5 min and incubated at room temperature for 2 h with Alexa Fluor 488® goat anti-rabbit IgG (Molecular ProCES, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The sections were washed with PBS-T as described earlier, mounted on glass slides with Fluoromount™ Aqueous Mounting Medium (Sigma, Saint Louis, MO, USA), and then covered with cover slips. For FJ staining, 24 h after the CES, the animals were perfused and the brains were cut. The brain mounted slides were transferred to a solution of 0.06% KMnO4 for 15 min and washed in distilled water three times for 1 min. After 30 min in the staining solution containing 0.0001% FJ C (Fluorojade C; Chemicon International, Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany), the slides were rinsed with distilled water 3 times for 1 min and fully dried. Finally, the slides were immersed in xylene and cover slipped with mounting media. As GFAP control, another group of animals was subjected to cortical electrolytic damage by direct AC current (square wave, 1 mA, 10 s) applied through the electrode. As ATF3 and FJ controls, Status Epilepticus (SE) was induced in another group of animals by systemic injection of methyl-scopolamine (2 mg/kg) followed by i.p. pilocarpine (320 mg/kg) (Castro et al., 2011). Ninety minutes after SE establishment, the animals were killed, perfused and their brains were removed. A confocal microscope (SP5, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) was used to visualize and capture GFAP, ATF3 and FJ stained sections under the same light conditions.

2.15. Cytokines measurement by ELISA

For cytokines assessment the synovial cavities were opened, washed with a mixture of PBS/EDTA (1 mM) by a micropipette and diluted (1:5). The samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70 °C. On the day of the assay, the samples were thawed and maintained in ice until the end of the experiment. The samples were homogenized in 500 μL of the appropriate buffer containing protease inhibitors followed by centrifugation for 10 min at 2000g to collect the supernatant. The supernatant was used to measure the levels of TNF (catalog # DY510), interleukin (IL)-1β (catalog # DY501), and IL-6 (catalog # DY506) by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using Duo set kits from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to the user manual. Cytokine concentrations were expressed in pgmL−1 based on standard curves.

2.16. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Prism 6.0 (GraphPad) software. Neutrophil recruitment to the knee joint, cytokine, behavioral data, and the number of Fos + neurons measurement was statistically analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Tukey’s multiple comparison post hoc test. The time course of joint diameter and clinical score were analyzed with the two-way ANOVA for repeated measures followed by the Bonferroni’s post hoc test when indicated. The analysis of the difference between the two groups was performed by Student’s t-test. The experimental sample n refers to the number of animals and is indicated inside each graph bar and data are expressed as the mean +/− standard error of the mean. Differences were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05. None of the animals with CES and cortical and hippocampal EEG recordings showed any substantial epileptiform-like alteration (2 standard deviations above or below the baseline) by visual examination that would deserve statistical analysis. EEG basal and post periods were analyzed during approximately 5 min before and after stimulus. The signals were analyzed using Matlab (2009 version, The Math Works, Inc) and GraphPad Prism version 5.0. Differences with p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Afferent vagal stimulation reduced knee joint inflammation

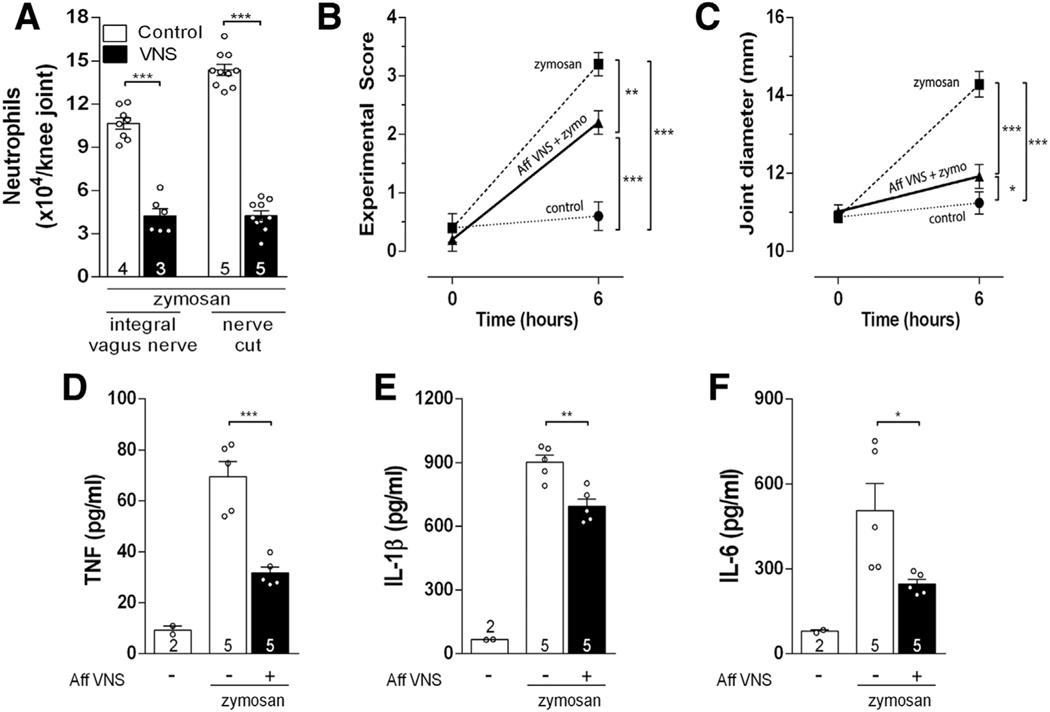

We first analyzed whether selective afferent vagal stimulation controls arthritic join inflammation by itself, without any efferent signal (Supplementary Fig. 1A). Previous studies focused on efferent vagal stimulation directed toward the innervation of peripheral organs (Borovikova et al., 2000; Huston et al., 2006; Matteoli et al., 2013; Torres-Rosas et al., 2014). We performed distal neurectomy of the vagus nerve in order to prevent any potential efferent signal. One day later, vagal afferent electrical stimulation was induced by activating the proximal (afferent) vagal nerve tip. Afferent vagal stimulation (5 Hz, 0.1ms, 1 V) in anesthetized animals reduced neutrophil joint infiltration similar to that induced by control stimulation of the intact vagus nerve (without neurectomy) (Fig. 1A). Afferent vagal stimulation significantly improved the experimental score of arthritis (Fig. 1B), reduced joint diameter (articular edema) (Fig. 1C), and the synovial levels of TNF (Fig. 1D), IL-1β (Fig. 1E), and IL-6 (Fig. 1F). Then, we analyzed whether afferent vagal stimulation controls arthritic joint inflammation through the mechanisms previously described in experimental sepsis. Vagal stimulation controls peripheral inflammation in sepsis by regulating splenic lymphocytes or dopamine production from the adrenal glands (Huston et al., 2006; Pena et al., 2011; Rosas-Ballina et al., 2011; Torres-Rosas et al., 2014). However, in the present study, right vagal afferent stimulation still inhibited arthritic joint inflammation in animals submitted to subdiaphragmatic vagotomy, splenectomy or adrenalectomy (Supplementary Fig. 2A). These results indicated that this vagal afferent mechanism represents a new mechanism of neuro-immune regulation that is independent of the subdiaphragmatic vagus nerve, the spleen and the adrenal glands. Then, we analyzed whether the anti-inflammatory potential of afferent vagal stimulation was mediated by the sympathetic nervous system by performing unilateral removal of the sympathetic chain (L2-L6). The anti-inflammatory potential of afferent vagal stimulation was abolished by ipsilateral, but not contralateral, knee surgical sympathectomy (Supplementary Fig. 2B). These results show that afferent vagal regulation of arthritic joint inflammation is mediated by a central neural pathway and not through the canonical efferent mechanisms previously reported.

Fig. 1.

Afferent vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) reduces articular inflammation by means of local sympathetic modulation. (A) Afferent VNS has the same effect as the intact VNS. Afferent VNS improved knee (B) experimental score, (C) articular edema, (D) neutrophil count (n = 5 for each group), and synovial levels of (E) TNF, (F) IL-1β, and (G) IL-6. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. The number of animals used for each group is displayed at the bottom of the corresponding bar. *p < 0.05; *p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

3.2. Vagal stimulation induced c-Fos expression in brain cortical structures of awaked rats

Next, we investigated the central neuronal structures mediating the vagal regulation of arthritic joint inflammation (Supplementary Fig. 1B). First, we analyzed which brain nuclei were activated by vagal afferent stimulation by using c-Fos expression analysis, a well-established marker of neuronal activity (Morgan et al., 1987). In order to avoid unspecific c-Fos expression due to anesthesia, we stimulated the vagus nerve in awake, unanesthetized animals. As a control, we first confirmed that cervical right vagal stimulation induced bilateral c-Fos expression in the nucleus tract solitary (NTS) (Naritoku et al., 1995; Cunningham et al., 2007; Bassi et al., 2017) (Fig. 2A, B, G). We observed that vagal stimulation also induced c-Fos expression in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN) (Fig. 2C, D, G) and locus coeruleus (LC) (Fig. 2E, F, G). Of note, vagal stimulation also increased c-Fos expression in cortical brain areas such as the cingulate (Fig. 2H, I, L) and the parietal cortex (Fig. 2J, K, L), structures involved with sympathetic modulation and motor functions (Burns and Wyss, 1985; Drew et al., 2008; Tankus et al., 2014). It is important to note that our stimulation protocol did not induce any behavioral modification in rats exposed to the EPM test, since the classical (Fig. 2M) or complementary (Supplementary Fig. 3A–D) ethological parameters remained unchanged.

Fig. 2.

VNS increases c-Fos expression in brain cortical and subcortical areas. VNS increases c-Fos immunolabeling in the (AB) nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS), (CD) locus coeruleus (LC), (EF) hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN) (G), and in the cingulate (HI) (Cg) and (JK) parietal cortex when compared to the control, non-stimulated, group (GL). (M) VNS does not induce behavioral changes of rats exposed to the EPM test. III: third ventricle; IV: fourth ventricle. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test; The number of animals used for each group is displayed at the bottom of the corresponding bar. **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

3.3. Cortical electrical stimulation mimicked vagal c-Fos central expression

In order to design novel therapeutic strategies for rheumatoid arthritis, we studied whether central neurostimulation controls joint inflammation (Supplementary Fig. 1B). We hypothesized that cortical electrical stimulation (CES) of the parietal cortex (see electrodes array in Supplementary Fig. 4A, B) could mimic vagal regulation of arthritic joint inflammation. Cortical stimulation of the left parietal cortex in unanesthetized animals increased c-Fos expression in autonomic control-associated regions bilaterally, such as the PVN and the LC (Fig. 3A–D, G), but not in the NTS (Fig. 3E–G). Similar to vagal stimulation, CES also increased bilateral c-Fos expression in the cingulate (Fig. 3H, I, L) and parietal cortex (Fig. 3J–L). In addition, our cortical stimulation protocol did not produce behavioral modification observed in the EPM test for the classical (Fig. 3M) or complementary (Supplementary Fig. 3E–H) ethological parameters analysis. Since vagal and cortical stimulation induced similar effects, we compared the c-Fos protein expression after these stimulations by making a digital overlay of the brain slices considering localization, intensity and range. These studies showed that the NTS was activated by vagal but not by the CES (Fig. 4). Common activated structures were observed along the neuroaxis, such as LC, PVN, periaqueductal gray matter (PAG), raphe nucleus, amygdala, and the cingulate, parietal and piriform cortex (Fig. 4 yellow overlay). We also plotted a semi-quantitative c-Fos analysis between vagal (n = 4) and cortical (n = 4) stimulation using PTZ-treated animals (n = 2) as positive control (Table 1). We also created an illustrative qualitative analysis showing, in coronal (Supplementary Fig. 5) and sagittal (Supplementary Fig. 6) plates, common brain structures activated by both VNS and CES. We reasoned that these structures must play a critical role controlling arthritic joint inflammation since they were activated by both stimulations.

Fig. 3.

Cortical electrical stimulation (CES) increases c-Fos immunolabeling in brain sympathoexcitatory nuclei. CES (60 Hz, 0.5 ms, 50μA) increases c-Fos expression in the (AB) hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN) and (CD) locus coeruleus (LC), but not in the (EF) nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) (G). CES increases c-Fos expression in the (HI) cingulate cortex and in the (JK) parietal cortex when compared to the control (non-stimulated) group (L). (M) (CES) does not induce behavioral changes of rats exposed to the EPM test. III: third ventricle; IV: fourth ventricle. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. The number of animals used for each group is displayed at the bottom of the corresponding bar. **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; Scale bar = 100 μM.

Fig. 4.

Representative overlay (yellow) of serial coronal rat brain sections from both VNS (green) and CES (red) c-Fos immunolabeling observed along the divisions of the neuroaxis. Cg: cingulate cortex; LC: locus coeruleus; NTS: nucleus of the solitary tract; PAG: periaqueductal gray matter; Pir: piriform cortex; PVN: paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus; Retro: retrosplenial cortex. IA: interaural. Refer to Table 1 for a better c-Fos expression quantification among the different brain structures. The scale of the different brain sections was not maintained to ease visualization. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Table 1.

Semi-quantitative analysis of c-Fos expression along the brain neuro-axis in animals submitted to VNS, CES or PTZ compared to control (naive) rats according to the Rat Brain Atlas (Paxinos and Watson, 2007).

| C-FOS immunolabeling | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| VNS | CES | PTZ | |

| Cortex | |||

| Parietal | + | + | + + + |

| Cingulated 1 | + | + | + + |

| Cingulated 2 | + | + | + + |

| Piriform | + + + | + + + | + + + |

| Occipital | 0 | 0 | + |

| Hipocampus | |||

| Dentate gyrus dorsal | 0 | 0 | + + |

| Dentate gyrus ventral | 0 | 0 | + + |

| Amon’s Horn 1 | 0 | 0 | + + |

| Amon’s Horn 2 | 0 | 0 | + + |

| Amon’s Horn 3 | 0 | 0 | + + |

| Amygdala | |||

| Basolateral | + | 0 | + + |

| Central | 0 | 0 | + + |

| Medial | + | 0 | + + |

| Anterior cortical | 0 | 0 | + + |

| Thalamus | |||

| Lateral posterior | + | 0 | + + |

| Habenula | 0 | 0 | + |

| Hypothalamu | |||

| Paraventricular | + + + | + | + + |

| Lateral ventral | 0 | 0 | + + |

| Medial arcuate | 0 | 0 | + + |

| Nucleus | + | + | + + |

| Mesencephalon | |||

| Ventral PAG | + | + | + + |

| Dorsal PAG dorsal | + | + | + + |

| Raphe nucleus | + | + | + |

| Inferior colliculus | 0 | 0 | + |

| Superior colliculus | 0 | 0 | + |

| Coclear nuclei | + + + | + + + | + + + |

| Brainstem | |||

| Solitary tract nucleus | + + + | 0 | + + + |

| Dorsal motor nucleus | + + | 0 | + + |

| Locus coeruleus | + + + | + + | + + |

0: no difference; +: small difference (< 10%); ++: medium difference (>10 and ≤30%); + + +: large difference (> 30%).

3.4. Cortical electrical stimulation attenuated arthritic joint inflammation

Given that CES increased c-Fos expression in similar brain areas as the VNS, we speculated whether CES could also control arthritic joint inflammation (Supplementary Fig. 1C). Cortical stimulation improved the experimental score of arthritis (Fig. 5A), reduced joint diameter (Fig. 5B), local neutrophil migration (Fig. 5C), and synovial levels of TNF (Fig. 5D), IL-1β (Fig. 5E) and IL-6 (Fig. 5F). Cortical stimulation was a safe procedure to control arthritic joint inflammation since it did not induce: (i) anxiety-related behaviors of animals evaluated in the EPM test (Fig. 3M and Supplementary Fig. 3E–H); (ii) behavioral or electroencephalographic (EEG) epileptiform activity (primary or secondary afterdischarges, spikes, spikes and waves, or bursts) in both the hippocampus or cortex (Supplementary Fig. 6A, B; Power analysis suggests that the electrographic signs of hippocampus (p=0.2351) and cortex (p=0.5578) were similar for both periods analyzed (paired two-tailed test; t=1.679 df=2). See in this Figure, by contrast, a positive control (rapid amygdala kindling) with EEG epileptiform discharges); (iii) brain lesions evaluated by GFAP expression (associated to potential local neuroinflammation) (Supplementary Fig. 7C–E); (iv) nerve injury as determined by ATF3 immunolabeling (a well-known marker for nerve injury) (Tsujino et al., 2000) (Supplementary Fig. 7F–K); or (v) neurodegeneration as detected by Fluoro-Jade-positive (FJ+) histochemistry (Schmued et al., 1997) (Supplementary Fig. 7L–O). These results show the potential of CES to reduce arthritic joint inflammation without inducing noticeable side effects.

Fig. 5.

Cortical electrical stimulation (CES) improves articular inflammatory parameters. (A) Experimental score, (B) joint diameter, (C) neutrophilic infiltration, and synovial levels of (D) TNF, (E) IL-1β, and (F) IL-6 of the femorotibial joint in animals submitted to the CES; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. The number of animals used for each group is displayed at the bottom of the corresponding bar.

3.5. The anti-inflammatory effect of cortical stimulation depends on the integrity of the local sympathetic chain

Given that cortical stimulation activated brain structures involved in the modulation of the autonomic nervous system, such as the LC, PVN, and PAG (Guyenet, 1991; Stern, 2015; Venkatraman et al., 2017), and that the knee joints have substantial sympathetic innervation (Hildebrand et al., 1991; Schaible and Straub, 2014), we examined whether CES requires the articular sympathetic innervations to control joint inflammation (Supplementary Fig. 1D). First, we observed that CES decreased rat’s tail skin temperature (Fig. 6A), suggesting a sympathetic activation. To examine whether local sympathetic innervations were required to control inflammation, we performed unilateral sympathectomy (L2-L6) prior to cortical stimulation. Cortical stimulation reduced neutrophil infiltration in the knee contralateral to the sympathectomy (Contra – SYMPX), but not in the ipsilateral (Ipsi – SYMPX) joint (Fig. 6B). These findings demonstrated that cortical stimulation controls arthritic joint inflammation via local sympathetic innervation of the joint.

Fig. 6.

(A) CES decreases rat tail temperature; (B) CES anti-inflammatory effect is prevented in the ipsilateral joint to the surgical sympathectomy (Ipsi – SYMPX) when compared the contralateral sympathectomized (Contra – SYMPX) knee. ***p < 0.001. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. The number of animals used for each group is displayed at the bottom of the corresponding bar.

4. Discussion

The present study depicts a central neuroimmune map composed by several common brain structures activated by afferent vagal or cortical stimulation which can be harnessed for managing inflammatory disorders such as arthritic inflammation by decreasing local production of inflammatory cytokines and neutrophilic infiltration into the knee joint.

Early studies reported that vagal stimulation controlled joint inflammation in clinical and experimental settings (Levine et al., 2014; Koopman et al., 2016; Bassi et al., 2017). We recently reported that this effect was mediated by afferent vagal signals that activate central sympathomodulatory structures, such as the PVN and LC (Bassi et al., 2017). Despite studies showing that 5 Hz activated both afferent and efferent vagal fibers (Reyt et al., 2010), here we can consider that the anti-inflammatory effect of 5 Hz VNS is due to activation of afferent vagal mechanisms because: 1) Previous studies showed that 5 Hz stimulation of the efferent part of the right vagus nerve induced significant changes in heart rate and systemic mean arterial pressure (Hotta et al., 2009). However, we previously showed that stimulation of the intact right vagus with 5 Hz reduced joint inflammation and activated brain nuclei without inducing significant cardiovascular alterations (Bassi et al., 2017); 2) In the present study, afferent VNS with 5 Hz reduced knee inflammation independently on the integrity of peripheral structures described for experimental sepsis, such as the spleen, celiac vagus, or adrenal glands; 3) the knee joint capsule has no cholinergic innervation (Langford and Schmidt, 1983; Ferreira-Gomes et al., 2010); 4) There was noticeable reduction on the respiratory rate during the VNS, an effect also observed previously during afferent VNS (Bassi et al., 2017), suggesting modulation of central respiratory centers activity. Furthermore, vagal afferent stimulation induced a significant increase in c-Fos expression in cortical brain areas, such as the piriform, cingulate and especially in the parietal cortex. Of note, increased c-Fos expression was also observed in the LC after VNS, suggesting this structure as the direct intermediate between the NTS (vagus nerve) and the cortex (Semeniutin, 1990; Cheyuo et al., 2011; Naritoku et al., 1995; Cunningham et al., 2007). Finally, it is important to comment that different intensities of nerve stimulation can generate different modulatory effects. We recently demonstrated that low VNS intensity (5 Hz, 1 V) in rats reduced joint inflammation but did not produce cardiovascular effects; while higher VNS intensity (20 Hz, 3 V), as commonly performed for clinical epilepsy treatment, induces profound cardiovascular alteration but no anti-inflammatory effect (Bassi et al., 2017).

Direct CES of the parietal cortex induced very similar patterns of brain c-Fos expression in rats exposed to VNS, suggesting common brain structures involved in peripheral inflammation control. In fact, cortical stimulation reduced tail temperature and CES anti-inflammatory effect was abolished by local sympathectomy, suggesting neuroimmune mechanisms dependent on sympathetic mechanisms and innervation. These phenomena can be explained by the increased c-Fos expression in sympathomodulatory brain structures, such as the LC, PVN and PAG observed after CES (Kannan et al., 1989; Plas et al., 1995; Farkas et al., 1998; Samuels and Szabadi, 2008). Together, these results concur with neuroanatomical studies showing a cortex-PAG-PVN or cortex-PAG-LC neural pathways in the modulation of sympathetic signaling (Ennis et al., 1991; Menezes et al., 2009; Ye et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2016). In addition, the activation of other sympathomodulatory brain nuclei, such as the catecholaminergic A5 and C1 neuron clusters, by afferent vagal or brain stimulation are likely to reduce synovial inflammation as seen for LC or cortical stimulation (Abbott et al., 2012; Carlson et al., 1996; Kuroki et al., 2004). In fact, mice are protected from ischemia-reperfusion injury when the C1 neurons are stimulated (Abe et al., 2017).

It is also important to highlight that our experimental neural stimulation techniques were conducted in non-anesthetized animals, suggesting that clinical neural stimulation protocols intended to be used in unanesthetized and unsedated patients, such as transcranial stimulation techniques, may be useful as a low cost therapy for the treatment of inflammatory articular diseases. In addition, non-invasive techniques of brain stimulation can avoid undesirable side effects of intrusive neuromodulatory therapies, such as surgical, device related, or nerve stimulation-induced complications, including post-operative infections, rejection, nerve damage, or behavior/cardiovascular alterations (Tronnier, 2015; Sokolovic and Mehmedagic, 2016). Our results may also explain the central immunomodulatory structures and mechanisms during individual self-stimulation techniques. Studies carried in humans showed that voluntary breath control techniques (brain cortex-modulated) can stimulate the sympathetic functions in order to modulate the innate immunity, suggesting the existence of unknown immunoregulatory encephalic centers (Krogh and Lindhard, 1913; Kox et al., 2012, 2014). In fact, clinical studies have already demonstrated that extra-encephalic stimulatory techniques, such as magnetic or direct current transcranial stimulations, can increase the sympathetic activity (Frank et al., 2010; Chang et al., 2015). The present data may also complement studies about placebo effects in inflammatory diseases. About a third of rheumatic patients may report disease improvement by pharmacologically inert medicines (Beecher, 1955; Langley et al., 1983; Williams et al., 1988). In fact, placebo effect relies on complex biological mechanisms involving the activation of relevant brain areas implicated in emotions, expectations, and classical conditioning (Qiu et al., 2009; Finniss et al., 2010), as observed in neuroimaging studies where increased activity of the cingulate and parietal cortex, PAG, and medullary structures was observed during placebo treatment (Levine, 1978; Bingel et al., 2006). Further, other auto-motivated behavioral techniques that depend on complex interaction of multiple cortical structures, such as voluntary muscular exercises, may produce immunomodulatory effects toward the activation of similar neural cascades that involves motor coordination (e.g.: parietal cortex), motivation (e.g.: cingulate cortex) and autonomic balance (Burns and Wyss, 1985; Hamer, 2006; Drew et al., 2008; Gleeson et al., 2011; Macefield and Henderson, 2015; Shoemaker et al., 2015).

Finally, our data is consistent with several theories related to brain-immune interactions: (i) the existence of the immunological homunculus where the somatotopic organization of the central nervous system can coordinate the immune system (Tracey, 2007; Diamond and Tracey, 2011); (ii) the polyvagal theory where different vagal subsystems, particularly the afferent myelinated components, associated to the so-called “social engagement system”, are critical to control highly cognitive behaviors and emotions (Porges, 2011); and (iii) the neocortical-immune axis where complex cognitive behaviors, such as attitudes, spiritual resources, hopes, ideals, and meditative states may shape immunity (Moshel et al., 2005; Tuohy, 2005; Kox et al., 2012, 2014; van Middendorp et al., 2015). We do not rule out the possibility that all these three complex systems could act in synchrony to control immune response-directed behaviors (Bassi et al., 2011; Filiano et al., 2016). Now, the most compelling and intriguing collection of data comes from coma patients in which VNS (Vagus-NTS-Thalamus-Parietal Cortex connections) and recruitment of complex networks by performing imagery tasks, results in strong alteration in consciousness (even in a patient that spent 15 years in coma) (Corazzol et al., 2017), probably the strongest support to our expectations of anti-inflamamatory effect of yoga, meditation (mindfulness) and activation of the social engagement system, measured by MRI activity. Surely, the coma patients are the highest possible challenge to recruitment of consciousness networks.

In summary, our study provides new data about the dissection of the central inflammatory processing centers (in contrast to the classical cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway) that are activated through overlapped, complex cortical and vagal stimulation (Supplementary Fig. 8) and can be useful in the development of innovative, viable and safe bioelectronic strategies for the treatment of inflammatory joint conditions in a real translational project.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by FAPESP project grants (2007/50261-4, 2011/20343-4, 2012/04237-2, 2013/20549-7 and 2013/08216-2), CAPES-PROEX Physiology and Pharmacology Graduate Programs at FMRP-USP and CNPq project grants (870325/1997-3, 478504/2010-1 and 475715/2012-8). GSB holds a PhD scholarship from CNPq (142068/2012-8). AK holds a PD scholarship from CNPq (118636/2017-0). FQC, HCS, TMC and NGC hold CNPq Research Fellowships.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2018.02.013.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- Abbott SB, Kanbar R, Bochorishvili G, Coates MB, Stornetta RL, Guyenet PG, 2012. C1 neurons excite locus coeruleus and A5 noradrenergic neurons along with sympathetic outflow in rats. J. Physiol. 590, 2897–2915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abe C, Inoue T, Inglis MA, Viar KE, Huang L, Ye H, Rosin DL, Stornetta RL, Okusa MD, Guyenet PG, 2017. C1 neurons mediate a stress-induced anti-inflammatory reflex in mice. Nat. Neurosci. 20, 700–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anseloni VZ, Brandão ML, 1997. Ethopharmacological analysis of behaviour of rats using variations of the elevated plus-maze. Behav. Pharmacol. 8, 533–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassi GS, Kanashiro A, Santin FM, de Souza GEP, Nobre MJ, Coimbra NC,2011. Lipopolysaccharide-induced sickness behaviour evaluated in different models of anxiety and innate fear in rats. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 110, 359–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassi GS, Brognara F, Castania JA, Talbot J, Cunha TM, Cunha FQ, Ulloa L, Kanashiro A, Dias DPM, Salgado HC, 2015. Baroreflex activation in conscious rats modulates the joint inflammatory response via sympathetic function. Brain Behav. Immun. 49, 140–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassi GS, Dias DPM, Franchin M, Talbot J, Reis DG, Menezes GB, Castania JA, Garcia-Cairasco N, Resstel LBM, Salgado HC, Cunha FQ, Cunha TM, Ulloa L, Kanashiro A, 2017. Modulation of experimental arthritis by vagal sensory and central brain stimulation. Brain Behav. Immun. 64, 330–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beecher HK, 1955. The powerful placebo. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 159, 1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingel U, Lorenz J, Schoell E, Weiller C, Büchel C, 2006. Mechanisms of placebo analgesia: rACC recruitment of a subcortical antinociceptive network. Pain 120, 8–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borovikova LV, Ivanova S, Zhang M, Yang H, Botchkina GI, Watkins LR, Wang H, Abumrad N, Eaton JW, Tracey KJ, 2000. Nature 405, 458–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyden SD, Hossain IN, Wohlfahrt A, Lee YC, 2016. Non-inflammatory causes of pain in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep 18 (6), 18–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bratton BO, Martelli D, McKinley MJ, Trevaks D, Anderson CR, McAllen RM,2012. Neural regulation of inflammation: no neural connection from the vagus to splenic sympathetic neurons. Exp. Physiol. 97, 1180–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buller KM, 2003. Neuroimmune stress responses: reciprocal connections between the hypothalamus and the brainstem. Stress 6, 11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns SM, Wyss JM, 1985. The involvement of the anterior cingulate cortex in blood pressure control. Brain Res. 340, 71–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson SL, Beiting DJ, Kiani CA, Abell KM, McGillis JP, 1996. Catecholamines decrease lymphocyte adhesion to cytokine-activated endothelial cells. Brain Behav. Immun. 10, 55–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro OW, Furtado MA, Tilelli CQ, Fernandes A, Pajolla GP, Garcia-Cairasco N, 2011. Comparative neuroanatomical and temporal characterization of FluoroJade-positive neurodegeneration after status epilepticus induced by systemic and intrahippocampal pilocarpine in Wistar rats. Brain Res. 1374, 43–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang W-J, Bennell KL, Hodges PW, Hinman RS, Liston MB, Schabrun SM, 2015. Combined exercise and transcranial direct current stimulation intervention for knee osteoarthritis: protocol for a pilot randomised controlled trial: table 1. BMJ Open 5, e008482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, He ZG, Liu SG, Xiang HB, 2016. Motor cortex-periaqueductal gray-rostral ventromedial medulla neuronal circuitry may involve in modulation of nociception by melanocortinergic-opioidergic signaling. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 9 (8), 7837–7907. [Google Scholar]

- Cheyuo C, Jacob A, Wu R, Zhou M, Coppa GF, Wang P, 2011. The parasympathetic nervous system in the quest for stroke therapeutics. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 31, 1187–1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corazzol M, Lio G, Lefevre A, Deiana G, Tell L, André-Obadia N, Bourdillon P, Guenot M, Desmurget M, Luauté J, Sirigu A, 2017. Restoring consciousness with vagus nerve stimulation. Curr. Biol. 27, R979-R1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham JT, Mifflin SW, Gould GG, Frazer A, 2007. Induction of c-Fos and DeltaFosB immunoreactivity in rat brain by vagal nerve stimulation. Neuropsychopharmacology 33, 1884–1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond B, Tracey KJ, 2011. Mapping the immunological homunculus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 108, 3461–3462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew T, Andujar J-E, Lajoie K, Yakovenko S, 2008. Cortical mechanisms involved in visuomotor coordination during precision walking. Brain Res. Rev. 57, 199–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert U, Löscher W, 1995. Differences in mossy fibre sprouting during conventional and rapid amygdala kindling of the rat. Neurosci. Lett. 190 (3), 199–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edrees AF, Misra SN, Abdou NI, 2005. Anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: correlation of TNF-alpha serum level with clinical response and benefit from changing dose or frequency of infliximab infusions. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 23 (4), 469–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elenkov I, 1995. Modulation of lipopolysaccharide-induced tumor necrosis factor-production by selective - and -adrenergic drugs in mice. J. Neuroimmunol. 61, 123–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennis M, Behbehani M, Shipley MT, van Bockstaele EJ, Aston-Jones G, 1991. Projections from the periaqueductal gray to the rostromedial pericoerulear region and nucleus locus coeruleus: anatomic and physiologic studies. J. Comp. Neurol. 306, 480–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farkas E, Jansen AS, Loewy AD, 1998. Periaqueductal gray matter input to cardiac-related sympathetic premotor neurons. Brain Res. 792, 179–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favalli EG, Desiati F, Atzeni F, Sarzi-Puttini P, Caporali R, Pallavicini FB, Gorla R, Filippini M, Marchesoni A, 2009. Serious infections during anti-TNF treatment in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Autoimmun. Rev. 8, 266–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira-Gomes J, Adães S, Sarkander J, Castro-Lopes JM, 2010. Phenotypic alterations of neurons that innervate osteoarthritic joints in rats. Arthritis Rheum. 62, 3677–3685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- File SE, Lippa AS, Beer B, Lippa MT, 2001. Animal tests of anxiety In: Current Protocols in Neuroscience. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filiano AJ, Xu Y, Tustison NJ, Marsh RL, Baker W, Smirnov I, Overall CC, Gadani SP, Turner SD, Weng Z, Peerzade SN, Chen H, Lee KS, Scott MM, Beenhakker MP, Litvak V, Kipnis J, 2016. Unexpected role of interferon- in regulating neuronal connectivity and social behaviour. Nature 535, 425–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finniss DG, Kaptchuk TJ, Miller F, Benedetti F, 2010. Biological, clinical, and ethical advances of placebo effects. Lancet 375, 686–695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foresti ML, Arisi GM, Fernandes A, Tilelli CQ, Garcia-Cairasco N, 2008. Chelatable zinc modulates excitability and seizure duration in the amygdala rapid kindling model. Epilepsy Res. 79 (2–3), 166–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank E, Eichhammer P, Burger J, Zowe M, Landgrebe M, Hajak G, Langguth B, 2010. Transcranial magnetic stimulation for the treatment of depression: feasibility and results under naturalistic conditions: a retrospective analysis. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 261, 261–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gegout P, Gillet P, Chevrier D, Guingamp C, Terlain B, Netter P, 1994. Characterization of zymosan-induced arthritis in the rat: effects on joint inflammation and cartilage metabolism. Life Sci. 55, PL321–PL326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson M, Bishop NC, Stensel DJ, Lindley MR, Mastana SS, Nimmo MA, 2011. The anti-inflammatory effects of exercise: mechanisms and implications for the prevention and treatment of disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 11, 607–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon CJ, 1990. Thermal biology of the laboratory rat. Physiol. Behav. 47, 963–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyenet PG, 1991. Central noradrenergic neurons: the autonomic connection Prog. Brain Res. 365–380 (Elsevier; ). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamer M, 2006. Exercise and psychobiological processes. Sports Med. 36, 829–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewlett S, Ambler N, Almeida C, Cliss A, Hammond A, Kitchen K, Knops B, Pope D, Spears M, Swinkels A, Pollock J, 2011. Self-management of fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised controlled trial of group cognitive-behavioural therapy. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 70 (6), 1060–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand C, Öqvist G, Brax L, Tuisku F, 1991. Anatomy of the rat knee joint and fibre composition of a major articular nerve. Anat. Rec. 229, 545–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotta H, Lazar J, Orman R, Koizumi K, Shiba K, Kamran H, Stewart M, 2009. Vagus nerve stimulation-induced bradyarrhythmias in rats. Auton. Neurosci. 151, 98–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huston JM, Ochani M, Rosas-Ballina M, Liao H, Ochani K, Pavlov VA, Gallowitsch-Puerta M, Ashok M, Czura CJ, Foxwell B, Tracey KJ, Ulloa L, 2006. Splenectomy inactivates the cholinergic antiinflammatory pathway during lethal endotoxemia and polymicrobial sepsis. J. Exp. Med. 203, 1623–1628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue T, Abe C, Sung SJ, Moscalu S, Jankowski J, Huang L, Ye H, Rosin DL, Guyenet PG, Okusa MD, 2016. Vagus nerve stimulation mediates protection from kidney ischemia-reperfusion injury through 7nAChRmathplus splenocytes. J. Clin. Investig. 126, 1939–1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inui K, Koike T, 2016. Combination therapy with biologic agents in rheumatic diseases: current and future prospects. Ther. Adv. Musculoskelet. Dis. 8, 192–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannan H, Hayashida Y, Yamashita H, 1989. Increase in sympathetic outflow by paraventricular nucleus stimulation in awake rats. Am. J. Physiol. 256, R1325–R1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenney MJ, Ganta CK, 2011. Autonomic nervous system and immune system interactions In: Comprehensive Physiology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keystone EC, Schorlemmer HU, Pope C, Allison AC, 1977. Zymosan—induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 20, 1396–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koopman FA, Chavan SS, Miljko S, Grazio S, Sokolovic S, Schuurman PR, Mehta AD, Levine YA, Faltys M, Zitnik R, Tracey KJ, Tak PP, 2016. Vagus nerve stimulation inhibits cytokine production and attenuates disease severity in rheumatoid arthritis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 113, 8284–8289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kox M, Stoffels M, Smeekens SP, van Alfen N, Gomes M, Eijsvogels TMH, Hopman MTE, van der Hoeven JG, Netea MG, Pickkers P, 2012. The influence of concentration/meditation on autonomic nervous system activity and the innate immune response. Psychosom. Med. 74, 489–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kox M, van Eijk LT, Zwaag J, van den Wildenberg J, Sweep FCGJ, van der Hoeven JG, Pickkers P, 2014. Voluntary activation of the sympathetic nervous system and attenuation of the innate immune response in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, 7379–7384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogh A, Lindhard J, 1913. The regulation of respiration and circulation during the initial stages of muscular work. J. Physiol. 47, 112–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroki K, Takahashi H, Iwagaki H, Murakami T, Kuinose M, Hamanaka S, Minami K, Nishibori M, Tanaka N, Tanemoto K, 2004. 2-adrenergic receptor stimulation-induced immunosuppressive effects possibly through down-regulation of co-stimulatory molecules, ICAM-1, CD40 and CD14 on monocytes. J. Int. Med. Res. 32, 465–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langford LA, Schmidt RF, 1983. Afferent and efferent axons in the medial and posterior articular nerves of the cat. Anat. Rec. 206, 71–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley GB, Sheppeard H, Wigley RD, 1983. Placebo therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 1, 17–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine J, 1978. The mechanism of placebo analgesia. Lancet 312, 654–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine YA, Koopman FA, Faltys M, Caravaca A, Bendele A, Zitnik R, Vervoordeldonk MJ, Tak PP, 2014. Neurostimulation of the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway ameliorates disease in rat collagen-induced arthritis. PLoS One 9, e104530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macefield VG, Henderson LA, 2015. Autonomic responses to exercise: cortical and subcortical responses during post-exercise ischaemia and muscle pain. Auton. Neurosci. 188, 10–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani A, Cassatella MA, Costantini C, Jaillon S, 2011. Neutrophils in the activation and regulation of innate and adaptive immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 11, 519–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martelli D, Yao ST, Mancera J, McKinley MJ, McAllen RM, 2014. Reflex control of inflammation by the splanchnic anti-inflammatory pathway is sustained and independent of anesthesia. AJP 307, R1085-R1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matteoli G, Gomez-Pinilla PJ, Nemethova A, Giovangiulio MD, Cailotto C, van Bree SH, Michel K, Tracey KJ, Schemann M, Boesmans W, Berghe PV, Boeckxstaens GE, 2013. A distinct vagal anti-inflammatory pathway modulates intestinal muscularis resident macrophages independent of the spleen. Gut 63, 938–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menezes RCAD, Zaretsky DV, Fontes MAP, DiMicco JA, 2009. Cardiovascular and thermal responses evoked from the periaqueductal grey require neuronal activity in the hypothalamus. J. Physiol. 587, 1201–1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Middendorp H, Kox M, Pickkers P, Evers AWM, 2015. The role of outcome expectancies for a training program consisting of meditation, breathing exercises, and cold exposure on the response to endotoxin administration: a proof-of-principle study. Clin. Rheumatol. 35, 1081–1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan J, Cohen D, Hempstead J, Curran T, 1987. Mapping patterns of c-fos expression in the central nervous system after seizure. Science 237, 192–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moshel YA, Durkin HG, Amassian VE, 2005. Lateralized neocortical control of T lymphocyte export from the thymus. J. Neuroimmunol. 158, 3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naritoku DK, Terry WJ, Helfert RH, 1995. Regional induction of fos immunoreactivity in the brain by anticonvulsant stimulation of the vagus nerve. Epilepsy Res. 22, 53–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olofsson PS, Rosas-Ballina M, Levine YA, Tracey KJ, 2012. Rethinking inflammation: neural circuits in the regulation of immunity. Immunol. Rev. 248, 188–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlov VA, Tracey KJ, 2015. Neural circuitry and immunity. Immunol. Res. 63, 38–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C, 2007. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates, Sixth Edition: Hard Cover Edition. Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pena G, Cai B, Ramos L, Vida G, Deitch EA, Ulloa L, 2011. Cholinergic regulatory lymphocytes re-establish neuromodulation of innate immune responses in sepsis. J. Immunol. 187, 718–725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plas JVD, Maes FW, Bohus B, 1995. Electrophysiological analysis of midbrain periaqueductal gray influence on cardiovascular neurons in the ventrolateral medulla oblongata. Brain Res. Bull. 38, 447–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porges SW, 2011. The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-regulation (Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology). W. W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Y-H, Wu X-Y, Xu H, Sackett D, 2009. Neuroimaging study of placebo analgesia in humans. Neurosci. Bull. 25, 277–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis GM, Dias QM, Silveira JWS, Vecchio FD, Garcia-Cairasco N, Prado WA, 2010. Antinociceptive effect of stimulating the occipital or retrosplenial cortex in rats. J. Pain 11, 1015–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyt S, Picq C, Sinniger V, Clarendon D, Bonaz B, David O, 2010. Dynamic causal modelling and physiological confounds: a functional MRI study of vagus nerve stimulation. NeuroImage 52, 1456–1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosas-Ballina M, Olofsson PS, Ochani M, Valdes-Ferrer SI, Levine YA, Reardon C, Tusche MW, Pavlov VA, Andersson U, Chavan S, Mak TW, Tracey KJ, 2011. Acetylcholine-synthesizing T cells relay neural signals in a vagus nerve circuit. Science 334, 98–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiero D, Underwood M, Mann J, Anwar M, Arango V, 2000. The human nucleus of the solitary tract: visceral pathways revealed with an “in vitro” postmortem tracing method. J. Auton. Nerv. Syst. 79, 181–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutecki P, 1990. Anatomical, physiological, and theoretical basis for the antiepileptic effect of vagus nerve stimulation. Epilepsia 31, S1–S6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels E, Szabadi E, 2008. Functional neuroanatomy of the noradrenergic locus coeruleus: its roles in the regulation of arousal and autonomic function part I: principles of functional organisation. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 6, 235–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saper CB, 2011. Diffuse cortical projection systems: anatomical organization and role in cortical function In: Comprehensive Physiology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. [Google Scholar]

- Saper CB, Loewy AD, 1980. Efferent connections of the parabrachial nucleus in the rat. Brain Res. 197, 291–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaible H-G, Straub RH, 2014. Function of the sympathetic supply in acute and chronic experimental joint inflammation. Auton. Neurosci. 182, 55–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmued LC, Albertson C, Slikker W, 1997. Fluoro-jade: a novel fluorochrome for the sensitive and reliable histochemical localization of neuronal degeneration. Brain Res. 751, 37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semeniutin AI, 1990. The effect of electrical stimulation of the locus coeruleus on the neuronal activity of the parietal associative cortex. Neirofiziologiia 22, 486–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker JK, Norton KN, Baker J, Luchyshyn T, 2015. Forebrain organization for autonomic cardiovascular control. Auton. Neurosci. 188, 5–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokolovic S, Mehmedagic S, 2016. OS 11–06 the effect of vagus nerve stimulation on arterial hypertension using active implantable device. J. Hypertens. 34, e75. [Google Scholar]

- Stern JE, 2015. Neuroendocrine-autonomic integration in the paraventricular nucleus: novel roles for dendritically released neuropeptides. J. Neuroendocrinol. 27, 487–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tankus A, Fried I, Shoham S, 2014. Cognitive-motor brain-machine interfaces. J. Physiol. Paris 108, 38–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Rosas R, Yehia G, Peña G, Mishra P, del Rocio Thompson-Bonilla M, Moreno-Eutimio MA, Arriaga-Pizano LA, Isibasi A, Ulloa L, 2014. Dopamine mediates vagal modulation of the immune system by electroacupuncture. Nat. Med. 20, 291–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracey KJ, 2007. Physiology and immunology of the cholinergic antiinflammatory pathway. J. Clin. Investig. 117, 289–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tronnier VM, 2015. Vagus nerve stimulation: surgical technique and complications In: Pages 29–38 Progress in Neurological Surgery. Karger AG. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsujino H, Kondo E, Fukuoka T, Dai Y, Tokunaga A, Miki K, Yonenobu K, Ochi T, Noguchi K, 2000. Activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3) induction by axotomy in sensory and motoneurons: a novel neuronal marker of nerve injury. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 15, 170–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuohy VK, 2005. The neocortical-immune axis. J. Neuroimmunol. 158, 1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulloa L, Deitch EA, 2009. Neuroimmune perspectives in sepsis. Crit. Care 13, 133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upchurch KS, Kay J, 2012. Evolution of treatment for rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology(Oxford) 51 (Suppl 6), 28–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatraman A, Edlow BL, Immordino-Yang MH, 2017. The brainstem in emotion: a review. Front. Neuroanat. 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willemze RA, Welting O, van Hamersveld HP, Meijer SL, Folgering JHA, Darwinkel H, Witherington J, Sridhar A, Vervoordeldonk MJ, Seppen J, de Jonge WJ, 2017. Neuronal control of experimental colitis occurs via sympathetic intestinal innervation. Neurogastroenterol. Motil.3 30, e13163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams HJ, Ward JR, Dahl SL, Clegg DO, Willkens RF, Oglesby T, Weisman MH, Schlegel S, Michaels RM, Luggen ME, Polisson RP, Singer JZ, Kantor SM, Shiroky JB, Small RE, Gomez MI, Reading JC, Egger MJ, 1988. A controlled trial comparing sulfasalazine, gold sodium thiomalate, and placebo in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 31, 702–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye D-W, Liu C, Liu T-T, Tian X-B, Xiang H-B, 2014. Motor cortex-periaqueductal gray-spinal cord neuronal circuitry may involve in modulation of nociception: a virally mediated transsynaptic tracing study in spinally transected transgenic mouse model. PLoS One 9, e89486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.