Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic radically and rapidly changed the world, including the world of business economists. Eight NABE members employed in a wide variety of fields discuss how their lives and work were transformed.

Keywords: COVID, Pandemic, Economists, NABE

Diane Swonk

For this special edition of the Economics at Work section, I tapped a broad spectrum of economists to share how the COVID-19 pandemic has reshaped what we do. I hope you will find the insights and inspiration that I have in reading and working with these extraordinary individuals. They warned us that it was the course of the virus, not lockdowns alone, that would determine how the economy weathered the storm unleashed by COVID-19. They saw the role that fear played in our collective decision-making and the lingering effects that uncertainty could have on our ability to move past the initial shock. They revealed the inequality that COVID-19 magnified and exacerbated, not least in our own profession. They showed how systemic biases undermine our potential to grow, not just as individuals but as an economy. They taught us that what we do requires heavy doses of humility and humanity to execute effectively.

Lisa Cook

During and after the Great Recession, I was on the Obama-Biden Transition Team and at the White House at the Council of Economic Advisers from 2011 to 2012. Contributing analysis as an economist during the coronavirus recession has been at once harder than, easier than, and the same as during the Great Recession.

It has been more difficult to provide economic analysis for at least a couple of reasons. First, the pandemic is the reason for the economic dislocation and slowdown in economic activity. Therefore, it governs economic policy responses. Most macroeconomists are not experts in health and, more specifically, epidemiology, and have likely never dealt with such a sudden stop in economic activity that has been so protracted.

The coronavirus recession has required us to be more nimble, curious, open-minded, imaginative and comfortable with thinking about newly binding constraints and uncertainty along many dimensions. Second, the coronavirus recession evolved at breakneck speed. Unprecedented declines and changes in the composition of economic activity happened at an unprecedented pace. That required that the Federal Reserve, Congress, and the Administration act swiftly and without flinching. They did, at least early in the crisis.

Doing economic analysis in this environment has been less difficult than in the wake of the Great Recession. This mainly relates to the frequency and availability of data relevant for the crisis. Real-time data, both government and private data, are being collected and shared like never before. On the government side, the U.S. Census Pulse Surveys are weekly surveys of households and small businesses. Data from the pulse surveys have been useful for learning how consumer spending is evolving, such as food, rent or mortgage payments, in light of additional federal unemployment assistance and direct relief or stimulus payments.

From the private sector, firms, like OpenTable and Yelp, are making their data public, or their websites are being scraped for data related to restaurants and other small businesses on daily, weekly, and monthly bases. Homebase, software for small businesses to set schedules for workers, has made its data on hours worked public; these data have been analyzed by researchers to understand the impact of state and local social-distancing measures and other orders. The best publicly available data on small businesses I used during the Great Recession (Gallup surveys) were published infrequently. The current data sources help give a timely, accurate picture of recent developments in the economy to inform policy.

Some elements of economic analysis are neither more nor less difficult during the COVID recession than during the Great Recession. First, economists have to be voracious consumers of whatever data are available. We must be able to use, analyze and interpret the data we have and not the data we wish we had. We also have to believe the empirical results that are emerging, which are not always consistent with theory (or the simplest versions of theory) and may challenge fundamental economic principles or conventional wisdom. This is a reminder that economics is not religion. We cannot be dogmatic about data, assumptions, models or conclusions. We must be comfortable with nuance and deviations from behavior predicted by first principles. Second, as in the Great Recession, I have had to draw on every aspect of my training in economics as well as my lived experience. In crises, lived experience is even more important to inform policy because it helps economists create and weigh policy options. It also gives me empathy and a sense of urgency.

To match the speed of the pandemic’s effect on the economy, an economist with the lived experience of having been a health-care worker (phlebotomist) during a hepatitis outbreak, like I was, may be a little more informed and humble about the primacy of addressing the pandemic first and more motivated to encourage fast action that will lead to a faster recovery. Further, being an economist who happens to be a Black woman means that I have experienced the health-care system from the other side, where systemic racism that leads to disparities in health-care outcomes exists. Such an experience helped me to quickly see and investigate the disproportionate effect of the COVID crisis and recession on different groups in the economy.

A final similarity between analyzing the Great Recession and the coronavirus recession is the pattern of policy making. Congress acted on providing stimulus during the Great Recession, then imposed austerity when it was clear that the economy was beginning to recover. That was a substantial mistake that precipitated a protracted recovery.

With the expiration of provisions of the CARES Act at the end of July, including additional unemployment insurance (UI) payments of $600 per week, Congress is repeating itself and allowing increases in human suffering that will prolong recovery, including by forcing people to make suboptimal decisions, which will likely increase the spread of disease that will likely deepen the economic crisis. It is disappointing to see Congress repeating history. With little or no sense of urgency to pass another relief bill, a wave of evictions, mortgage defaults, homelessness and bankruptcies is likely to follow in the coming weeks based on the data related to rental households and businesses that cannot pay their rent. It is reminiscent of the Great Depression.

Finally, I hope a couple of features of analyzing the coronavirus recession outlive it. An important trait the pandemic has honed is being humble when faced with an exogenous event and a pandemic to which economics can make only a limited contribution relative to the contribution that public health experts can make.

I am fortunate to have had some modest preparation with factors similar to these and have brought these experiences from emerging markets and developing countries to bear to inform policy now. Writing a dissertation in Russia during the turbulent 1990s led me to have a healthy skepticism of data generated by all entities and to approach an economy that was in shock with humility and curiosity. My experience advising the Government of Rwanda for its first post-genocide IMF program has informed how I would shape policy in an environment where sudden, traumatic change happens and where uncertainty is a more prominent feature than usual at all levels of decision-making.

I hope that another lasting feature of economic analysis that does not depart with the pandemic is the knowledge of and attention to distributional issues and how systemic racism affects them. Macroeconomic analysis should pay attention to distribution and inequality, not just levels, especially related to who and which sectors and businesses are being disproportionately affected. These structural issues need to be addressed urgently and cannot wait for the next crisis.

Julia Coronado

Every recession is different yet shares common elements and dynamics. The challenge for forecasters is to know which tools apply to a given situation while flexibly adapting to new circumstances. Among the current challenges, I highlight two that have particular influences on the current cycle and have changed my approach to forecasting the outlook. First, the COVID-19 recession is the first global pandemic any current forecaster has encountered and adds a significant health policy element to the macro outlook. Second, the Federal Reserve has reformulated its reaction function in a way that changes the relationship between financial conditions and the macro economy.

A global pandemic is an entirely new element for economic forecasters to grapple with. While economists are not epidemiologists, the understanding of externalities and public goods is a standard part of our toolkit. An infectious disease is a clear example of a negative externality whose effects will inevitably affect behavior. Sound public health policy is a public good with positive benefits that can’t be outsourced to the private sector and the profit motive.

Economists have generally been early and steadfast in stressing that first and foremost the virus and public health response will determine the outlook and shape of the recovery. Unfortunately, it proved too tempting for politicians reeling from the sudden stop in the economy to think they could beat science. States that reopened for business before the virus was contained saw it roar back in the summer months, leading to the reclosure of segments of their economies with their consumers hunkering down and voluntarily limiting activity to avoid getting sick.

The U.S. also failed to use the shutdowns to formulate a federal plan to test and provide support through protective supplies and guidelines. As a result, the U.S. economy is learning to operate with a high prevalence of COVID-19 and associated social distancing. That decision is deepening the degree of structural disruption and ensuring that the U.S. must face a more typical recession, with longer lasting pain, than many imagined at the outset.

One benefit of having a clear, external shock such as a pandemic is that it concentrated the focus and response by monetary and fiscal policy makers early on. The Federal Reserve had been engaged in a structural review of its policy strategy and tools before the COVID-19 pandemic hit and was able to put into action some of the lessons learned from the Global Financial Crisis of 2008–2009 and the slow recovery that followed. Two conclusions reached early in the Fed’s framework review were: (1) The Fed’s balance sheet policy is now a standard tool to be deployed in any recession; (2) that it is better to act aggressively than tentatively when the economy is sliding into recession and deploy all available tools simultaneously.

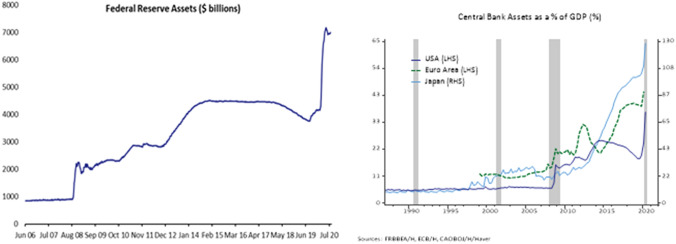

As financial markets seized in March 2020, the Fed acted quickly: It cut interest rates to the effective lower bound of zero; announced a large, open-ended program of Treasury and mortgage bond purchases; and, activated emergency liquidity facilities developed during the financial crisis of 2008. Other central banks around the world took similar steps. (See Fig. 1.)

Fig. 1.

Central banks moved early and aggressively and will continue expanding their balance sheets

The Fed’s bold actions stopped the health and economic crisis from metastasizing into a financial crisis. Their actions have been so effective that yields on Treasuries and mortgage rates hit all-time lows while the S&P 500 Index regained ground lost.

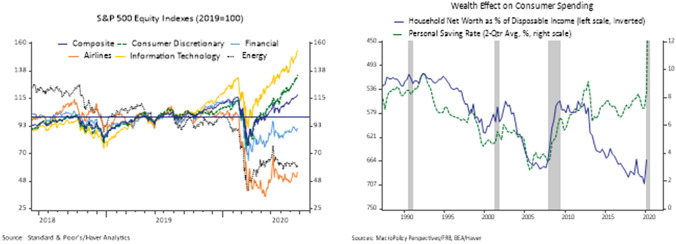

It is too strong a conclusion to say that markets are totally disconnected from the reality of a deep recession and an uncertain recovery. The left panel of Figure 2 shows that the equity market recovery has been narrowly focused on a handful of technology and consumer companies, while the majority of the companies in the index have valuations well below their pre-COVID levels.

Fig. 2.

Markets are Buoyant but still picking winners and losers, financial conditions have asymmetric impact

The Fed’s policies have been very effective in supporting a recovery in financial markets and limiting the negative feedback loop that takes hold during recessions. If companies’ valuations and consumer wealth plunge as a recession takes hold, they pull back on hiring, investing and spending that further deepen the hole out of which the economy must climb. Monetary and fiscal policy focus on breaking and reversing that negative cycle. The goal is to blunt the worst in losses and, ultimately, trigger a more virtuous cycle of hiring, spending and investment.

In a macro forecasting framework, financial conditions are a leading indicator of economic growth. However, that relationship has become increasingly asymmetric; while supporting financial markets helps short-circuit a negative feedback loop, it doesn’t translate as forcefully as it used to in increased growth. The right side of Figure 2 highlights that the personal saving rate used to rise and fall in an inverse relationship with wealth. As wealth rises, individuals tend to spend more freely and save less, and vice versa. In the past decade, rising wealth was not accompanied by falling saving rates, likely reflecting a combination of increased caution in the aftermath of the financial crisis, an aging population not adequately prepared for retirement and an increasingly unequal distribution of wealth. (Very wealthy people tend to save more of their gains in wealth.)

In the current context, that leads me to conclude that while the Fed’s policies have effectively limited the damage of the COVID-19 shock, a robust recovery will likely require more direct fiscal support to small businesses that do not benefit from the Fed’s policies and for consumers who are still experiencing double-digit unemployment.

The Fed’s policies have been wildly successful in keeping financial conditions well supported and credit flowing. An unintended consequence of that success may very well be increased complacency in Congress; market turmoil has traditionally served as a catalyst for action. Gridlock in Washington has united members of the Fed in their calls for additional fiscal support to speed up the recovery and provide more direct help for the millions who are still unemployed.

Emily Kolinski Morris

My team of economists at Ford Motor Company has a running joke—I’m sure not unique to our shop—about demand for economists being countercyclical: We are most essential to the business when the economy hits a rough patch. And so, I didn’t think I’d ever again be as busy as we were during the Great Recession. I was wrong.

It was the first company update of the new year when I initially wrote “coronavirus” into our submission. Some colleagues hadn’t heard of it yet. We briefly debated whether it made the cut to be highlighted for our senior team. It did make the cut, though at the time it was signaling risk specifically for our China business. We all know how the rest of the story goes. Two months later, my team was packing up as part of a remote work exodus unlike anything we could have imagined.

I am grateful to work for a company like Ford with the foresight, global reach and resources to be proactive when events like this emerge. I wasn’t the only one raising the red flag in January. Within a week of that first review, we were engaged in active planning sessions with our leadership team and experts from key functions to address fallout from the virus in different scenarios.

Over the course of my career, I’ve learned enough to be dangerous about many new topics as they emerged to impact our business environment, from artificial intelligence to shale oil production. So with some trepidation I became an amateur epidemiologist as it became clear we could not evaluate the path of the economy without anticipating the path of the virus itself. We relied on our internal experts, including our medical director and teams on the ground in hot spots around the world, as well as identifying the most credible sources of external expertise. No one had the answer, but we learned enough to manage our way through the staggering peaks of cases and deaths as the virus progressed around the world.

Another way in which economists are countercyclical, or perhaps contrarian is a better word here, is that we are often trying to point others, in the midst of a boom or a bust, to the next turn in the cycle. So from highlighting the risk of a distant and unheard of virus, we moved to calming fears of a protracted global recession as businesses, including our own dealers, were forced to close and unemployment jumped into the double digits. It was a sharp contrast with the experience in 2008–2009. For as breathtaking as it felt at the time, it took our industry 18 months to get from a healthy monthly sales rate of 16.5 million units (SAAR) down to the trough of 9.2 million in February 2009. This time, we found the bottom in just two months, from 17.3 million in February to a disconcertingly similar low of 9.1 million units in April.

The normal lagging relationship of unemployment to the economy was turned on its head, too. Instead of a slow march up in the unemployment rate, we were forecasting a huge spike followed by a recovery that defied characterization using any existing letter of the alphabet. When new vehicle sales hit their trough in February 2009, the unemployment rate was at 8.3% and still on its way up to the eventual peak of 10% in October of that year. It was a surreal story problem: If we sold 9 million vehicles then, with the unemployment rate at 8%, what could we expect when unemployment was expected to be double that rate? We couldn’t rely on existing models for this work. We had to construct granular scenarios based on conditions on the ground. We tracked dealership closures, regional lockdown measures and efforts to learn new ways of doing business (in our case, online sales and delivery models and contactless service and repair) starting with China’s provinces and ultimately moving on to U.S. states.

It is a mixed blessing serving as an economist in the auto industry because our industry itself is a leading indicator of the economy. So we had few other data points to rely on as we watched our own sales in China first plummet, but then rebound, giving us some confidence in the promise of better days ahead. We’re still not there yet; new vehicle sales remain 10–20% below their precrisis levels in many markets. We haven’t achieved the prerequisite for sustained economic recovery—getting the virus under control—in key markets, including the U.S. Some markets that appeared to have achieved containment are seeing a renewed increase in cases. But we’ve come a long way from the darkest days of February and March. Even in the absence of a vaccine, we are seeing more effective therapies and learned public health interventions (Please wear your mask!), which help us reengage in at least some precrisis activities.

On a personal note, forecasting through this crisis was different than anything I’ve experienced in my career. Learning about the virus wasn’t just about doing my job; it was understanding how it would impact my family and what I could do to protect my loved ones. The data we were tracking weren’t just statistics; they were people suffering in hospital rooms and families losing loved ones. It had a profoundly personal and emotional weight that was sometimes overwhelming.

That is why, throughout this crisis, the opportunity to engage with a network of friends and colleagues through organizations like NABE has never been more meaningful. While I miss gathering in person and exchanging handshakes and hugs, a virtual NABE is infinitely better than no NABE at all. I look forward to the next chapter of our collective history as we write it.

Anna Paulson1

The last time I was at the Chicago Federal Reserve building was on Sunday, March 15, 2020 for an unscheduled video meeting of the FOMC, when the committee decided to lower the fed funds target to zero and take dramatic actions in an effort to stabilize the market for Treasuries and agency mortgage-backed securities. I definitely had the sense that I had a front-row seat at an historic event. After the meeting, I toured the darkened research department looking at empty cubicles and offices, thinking about the people who inhabited them and wondering when we would all be there again.

Since March, my “office” has been a spare bedroom and the streets surrounding my house. I’ve spent hours on video calls and walking and talking on the phone with colleagues. Initially, those conversations were focused on understanding the instability in Treasury markets and what could be done to fix it. Then they pivoted to figuring out how to get real-time insights about an economy buffeted by a virus with the potential to spread exponentially and activity that could come to a halt overnight with stay-at-home orders.

As the weeks at home have continued, conversations about economic developments and monetary policy have been a place of familiarity and comfort, relative to the challenges that I’ve experienced in the other part of my job: leading 150 people in a new and highly uncertain environment. Our work has been intense and demanding as we’ve been living through the same disruptions to “normal” life as the rest of the country. Responding to economic and financial crises is part of the Fed’s mission, but doing so from home adds a whole new twist.

Together, we’ve made important and consequential contributions to the Fed’s mission. We've also hunted for toilet paper and hand sanitizer, baked, helped kids navigate online school, waited for the results of COVID-19 tests, celebrated graduations, engagements and new babies, welcomed new colleagues and said good-bye to those who are retiring, mourned the deaths of parents, experienced moments of laughter and felt lonely and isolated.

For me, a critical moment came after George Floyd’s murder. How should I respond? What could I say to the 150 people for whom I felt responsible? I’m pretty good at writing and describing economic and financial developments, but what could I say about that? I started and closed many emails, struggling to find the right words to acknowledge the pain and anguish that I suspected many were feeling. An email from a junior, and much wiser, colleague provided the nudge that I needed. He told me that people needed to hear something and that it didn’t matter if I got the words right. That thought has stayed with me and inspires me to be braver.

The past five months have been messy and imperfect as new challenges continue to emerge, but I feel grateful for my colleagues and proud of what we have been able to contribute collectively to the Fed’s mission and to the country during this time of crisis. I’m also extremely proud of all we are doing to stay connected to one another.

In an email to employees on the last day that we were all together working from 230 S. LaSalle Street, I wrote:

For many of us at the Chicago Fed, there have been moments in our professional lives that have stood out as extraordinary. Today’s decision to move to an extended remote work arrangement to protect our employees and the community will likely prove to be another one of those moments.

At the time, I wondered if I was being a little melodramatic. As I look back on those words today, I think if anything, I underestimated the significance of what we and the rest of the country were and are continuing to grapple with.

James Poterba

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a historic impact on the U.S. and the global economy and raised a fundamental set of public health and economic policy challenges. It has also led to an extraordinary and unprecedented redirection of economic research activity. Since the onset of the crisis, economists have launched a broad spectrum of research initiatives, which include: interactions between economic activity and COVID-19 infection rates, the impact of the pandemic and pandemic-related policies on the labor market, the financial decisions of households and firms and the potential monetary and fiscal policy responses to the pandemic.

Between March and August 2020, the nearly 1600 academic researchers affiliated with the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) distributed more than 225 pandemic-related studies via the NBER working paper series. This body of work, which represents only a small fraction of the research that has been carried out by economists in business, government and the academic community, provides a lens through which to view the broader research response to the pandemic. This comment describes several prominent strands of this emerging research program.

The economics profession’s first responders to the pandemic were macroeconomic modelers who drew on epidemiological research. They analyzed the trade-offs between economic activity and the rate of virus diffusion, building on two insights: (1) The virus can spread via interpersonal interactions that arise in the course of usual working and consuming; and, (2) A larger stock of infected workers reduces an economy’s output. Stylized models described how various public health-motivated policies, such as shutdowns of different stringencies and lengths, could alter the trajectories of virus cases and economic activity. These models could be calibrated with information on a few key parameters drawn from the epidemiological literature. Second-generation models recognized the different degrees of interpersonal contact and virus transmission risk in different industries and age groups. Both refinements suggested potential benefits from targeted rather than broad-based shutdown policies.

Quite distinct from the modeling exercises, a second line of research focused on describing the performance of the economy at various stages of the pandemic. The dramatic decline in economic activity during March 2020 was the result of a reluctance by consumers and companies to risk infection by engaging in in-person activities and the actual shutdowns. The speed with which economic conditions were changing and the significant lags in release of official measures such as the unemployment rate and GDP created greater-than-usual demand for high-frequency data.

Many researchers turned to data collected by private sector firms to track the economy. Data from private payroll processors were used to describe the decline in employment. Information on credit and debit card usage provided early readings on the magnitude of the fall in consumer spending. These data sources indicated the number of jobs lost and the magnitude of the spending drop and supported more refined insights on the economic dislocation. For example, the decline in employment was greater at small than at large firms, varied substantially across industries and was concentrated among lower wage workers. Consumer spending data captured the differential experience across sectors with outlays on hospitality, entertainment, and recreation particularly hard hit, while spending on groceries rose sharply during several weeks in March. Consumer spending by low-income households also seemed to rebound faster as the economy reopened than spending by their higher-income counterparts.

One of the challenges of analyzing administrative data from private sector firms is assessing the representativeness of these data for the broader economy. Data from payroll processors only reflect the experiences of the employers who use these services; they may not capture the employment patterns at small or new firms. Credit card clearings do not capture consumer spending that is paid for in cash or by check, which may omit some potentially important items such as rent.

Researchers have worked to calibrate broader economic aggregates with data that could be observed at a high frequency. They developed partnerships with state and local governments, such as the agencies that process unemployment insurance (UI) claims, to study the disaggregate patterns in UI claims. The weekly data were an important source of information on the evolution of the labor market between the monthly estimates of unemployment. In some states, researchers were able to link UI claims with other sources of administrative data. They documented claim patterns by weekly earnings, education level and geographic location. ZIP code-level data revealed differences in how the economic consequences of the pandemic played out.

A third strand of research, which did not begin to emerge until several months into the pandemic, examined the consequences of public policies that were adopted to provide relief. The most prominent are the CARES Act $600 per week federal supplement to state-provided UI benefits and the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) that provided firms with potentially forgivable loans. For many workers, after-tax income exceeded prior earnings while unemployed, raising the question of whether workers would return to work. The initial research suggests that supplements to UI did not deter most workers from returning. Research on the PPP program showed that its effects varied by the size and industry of the firm. The decline in demand in some industries was so great that the PPP loan was not sufficient to avert layoffs. In some industries, it was just enough to retain workers.

Our detailed knowledge of the economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, so soon after the start of the crisis, is a tribute to the availability of rich, new data sources. Partnerships between economic researchers and data providers in both the private and public sectors permitted almost real-time tracking of the economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. The research to date is just a start, which will enhance our understanding of the economy and better guide policy responses to future crises.

Claudia Sahm

My life as a macro policy expert during the COVID-19 crisis brings back memories from my “birth” as Fed forecaster in the Great Recession. In the past six months, I have used everything I know about the economic lives of people and every technical skill I have. I did not realize how much I had been training for ‘The Big One’ until it arrived. Over a decade of forecasts, current analysis, memos, briefings and research at the Fed and the White House paid off. Nothing could have fully prepared me for the tragedy we have lived this year, but I knew what to do when I saw the heartbreaking numbers.

I have had many opportunities to advise on economic policy. On March 11, the former CEA Chair for President Barack Obama, Jason Furman, and I spoke in front of the House Democrats on the looming economic disaster. I argued for a large relief package, including direct payments to families. I had worked at the Federal Reserve through the Great Recession and its slow recovery. I knew the stakes were high. I knew Congress had to go big, go fast and go wide. I knew it had to stay the course until the American people, all of them, were back on their feet.

I also knew I was scarred as a forecaster from the prior recession and its far-too-slow recovery. The night before my talk, I was second-guessing myself. Maybe I was being too pessimistic? Others were not as worried. Jason called and told me to “Be myself.” Good; that’s all I know how to be. I went with my gut and my expertise. I gave the House Democrats a full-throated appeal to get money out. I even got an “Amen” from one of my heroes in Congress as I spoke. I did my job that day. Sadly, I was right; the optimists in March were wrong. COVID led to economic suffering not seen since the Great Depression. The economic freefall in the spring was unprecedented and crushing. It was worse than 2008. I could hardly believe what I was seeing.

COVID destroyed every sense of normalcy, including the passage of time. The destruction from recessions normally arrives in months or quarters; this one came within weeks. During the Great Recession, it took over a year for the unemployment rate to hit 10%. During COVID, it shot up toward 20% within a month.

Thankfully, the policy response in D.C. was fast and furious. On March 15, 2020, I was standing at the stove making dinner for my kids and listening to Federal Reserve Chairman Jay Powell’s impromptu Sunday night press conference. I almost dropped to the floor when Powell said the word “recession.” In my second forecast in March 2008, the Fed staff put in the recession call. Our forecast meetings and briefings that round were ‘invite only.’ We were told not to utter the “R” word, even in the building. In 2020, Powell, said it to the world and then the Fed cut rates for the second time in a week. By the end of the month, Congress delivered a $2.2 trillion relief package. I did not sleep until it passed the Senate; we needed it. It was generous support, especially for the unemployed, at least initially.

I was encouraged by the initial relief from D.C., but did not rest easy. My biggest worry was that policy makers would not stay the course. I was right again. The Federal Reserve’s lending facilities for medium-sized businesses and municipalities have made only a handful of loans so far. Once again, the Fed did not try to save Main Street. Congress went home in August without passing a new relief package. In the spring, Congress had assumed that the pandemic would be under control by now and the economy well on its way to recovery. They were wrong on both counts. After the Great Recession, Congress stopped providing relief, citing mounting costs and negative side effects. I have watched this train wreck twice. The COVID recession went from “unprecedented” to “same old, same old” in months.

Now is not the time for the experts to throw in the towel. We know how to fight a recession from start to finish. We know how to help families, businesses and communities in need. We know what works. I left the Fed last November so I could advise policy makers in Congress on automatic stabilizers. I had developed a new recession indicator—the Sahm rule—that uses a small jump in the unemployment rate to ‘turn on’ relief in a recession automatically. I have helped develop rules that would turn it off when unemployment returns near precrisis levels.

I and many others are trying hard to get Congress to do more. I had been working nonstop with many offices on the Hill. I talk with anyone—in Congress, in the press and on social media—who will listen. I say, “Get more money out, a lot more money and put relief on autopilot.” Policy makers must continue to fight for us until the virus is under control and we are all back on track.

In short, being an expert on macro policy in this crisis has been a privilege and a nightmare. I take long walks in the morning; I call home to mom every day; and, I think about advice I received in 2008. In the depths of 2008, Dave Stockton, my Division Director at the Fed, told staff, “Put your head down and do your work. The Board needs your best analysis. You cannot deliver it if you are freaking out.” It is hard advice to follow, especially when traumatic data rolls in. I do my best. I try to help. I do not give up.

At the time, I wondered if I was being a little melodramatic. As I look back on those words today, I think if anything, I underestimated the significance of what the rest of the country was and is continuing to grapple with.

Michael Strain

Being an economist during the pandemic has been particularly challenging because, like all economists, I am not just an economist. I am the father of two young kids who were home this spring and summer. And, my wife has a demanding job.

My last day at the office was March 13. The balance of that month was chaos and is still a blur. I grew a pandemic beard, not because I chose to in any deliberate sense, but because any nonessential activity, including shaving, immediately went out the window. Every minute of each day was spent parenting or working. Sometimes both. I would irritate some of my colleagues by scheduling phone calls during times when I had to do the dishes. I remember one time I called a colleague about a routine work matter at 9.30pm on a Friday. She thought there was an emergency; I just didn’t have a firm handle on the day of the week or the time.

Eventually my family settled into a rhythm, but it was a very different rhythm than in the Before Times. I got used to doing work that didn’t require my full attention while also keeping an eye on the kids. I got used to switching quickly between work and parenting, hanging up a Zoom and walking downstairs to put my son down for a nap. I got used to ending my workday early (for me), around 5pm, having dinner with my family, doing bedtime and starting a three-hour block of work at 8pm. (I’m writing this essay during that block.)

I mention all this because the subject of my work has never intersected so directly with my personal experience. Over the past five months, I have advanced research projects on the Paycheck Protection Program, the earned-income tax credit, labor unions, minimum wages and technological automation. But I haven’t taken a PPP loan, received the EITC, belonged to a union or faced any real risk from automation. And, I haven’t worked a minimum-wage job since I was in high school.

I don’t know if direct exposure to working during the lockdown with kids at home has changed my thinking about pandemic response or altered my approach to my work. But it’s something I’ve thought about.

My perspective on the bounds of public policy has certainly changed due to the pandemic. I would not have thought Congress would ever create a program to replace a portion of the revenue lost by small businesses. I would not have thought Congress would increase the incomes of most unemployed workers above what they were making in their previous jobs. Whether or not you support these policies, you have to be impressed by their audacity. This makes me wonder whether we have been too timid about policy design in normal times.

Most of the policy advice I offer is well grounded in empirical economics research. One of the challenges of assessing current economic conditions, trying to get a handle on where the economy is headed and attempting to offer policy advice is the absence of a body of evidence to draw on that closely applies to this situation. This has led me to rely much more on basic economic theory than I normally would, but also on conversations with practitioners, business owners, corporations, trade and industry groups and Hill staff. I’ve found this to be an invaluable emphasis and one I hope to continue post-pandemic.

Information overload has been a challenge. I’ve found that falling back on traditional media has been helpful. Rather than trying to keep up with things in real time with Twitter or news webpages, I just wait until the end of the day and watch the news. Nightly news broadcasts and daily newspapers aggregate information, decide what is important and present it on a fixed schedule: an invaluable service.

My approach to economic recovery policy is straightforward and can be summarized in three sentences. We need to alleviate human suffering and remember our special obligation to the poor and the vulnerable. We need to preserve the productive capacity of the economy. We need to transition from a depression-level economy to a recession-level economy to a healthy economy as quickly as possible.

So we should strengthen the safety net and plug its holes. Small businesses that were profitable pre-pandemic should be given support by policy to adjust to today’s economy because the possibility of wasteful liquidations in that sector is so real. But that support should be time-limited. Small businesses that can’t figure out how to survive should not be propped up indefinitely by the government.

We should not bail out large firms because the threat of wasteful liquidation is much less severe. Shareholders shouldn’t be prioritized ahead of taxpayers for avoiding losses. The federal government should give grants to state and local governments to keep them from laying off workers and to keep the unemployment rate as low as possible.

We should not slow down the process of reallocation and adjustment by requiring small businesses to maintain pre-pandemic employment levels, propping up special industries or paying people more in unemployment benefits than they’ll make in their jobs. We should encourage business investment and entrepreneurship as a way for the economy to heal. And, the case for federal support of basic scientific research has never been stronger.

My perspective on how bad things can be has changed. I never thought I’d see depression-level unemployment. Living through history is a strange thing. The thought of my grandchildren decades from now asking me about the Pandemic of 2020 for their school projects is haunting.

The worst thing to happen to American in a century has uncovered many of the dark aspects of our politics and society—but in many cases it has brought out the best in our nation, as well. I have been struck by how courageous, flexible and creative so many workers and businesses have been in the face of this historic threat, rising to meet this unprecedented challenge. They will lead our rebuilding. We are in good hands.

Ellen Zentner

In economic downturns, the demand for market economists increases. And severe downturns oftentimes become career-defining moments for our profession.

We may not always be the best at identifying crises before they happen (COVID-19 is a prime example), but we can potentially add value by offering a framework for how folks should be thinking about all the possible outcomes as well as advising on solutions for getting families back on their feet quickly. In this way, the economist seeks to be the voice of reason in the room, providing calm in the midst of chaos.

COVID-19 has presented an unusual set of challenges for me, and all economists, compared to typical recessions. The expectations around COVID-19 of Morgan Stanley’s biotech analysts underpin the path of my medium-term forecasts for U.S. GDP. The evolution of the virus itself over the next 18 months holds the key to the economic outlook over the next five years, so their views are critically important to my numbers.

The support from U.S. fiscal policy came fast and furiously in April with nearly the entire country shut down. The shape of that support and how long it continues are key inputs to my forecasts. Thankfully, our U.S. public policy team has its finger on the pulse of Capitol Hill and can keep me apprised of developments that shape my team’s expectations for federal government, consumer and business spending.

My job is made easier by the deep collaboration among our teams, which allows me to lean heavily on areas of expertise where I am lacking. In the end, my forecasts are made more robust because I draw on the expertise of my colleagues across our research department.

Through my various advisory roles, I am able to take part in conversations that help shape monetary policy and I am grateful for the opportunity. As Morgan Stanley’s Fed watcher, I was impressed by the decisiveness of Chairman Jay Powell and the FOMC in acting aggressively to ease illiquid markets and financial conditions since March 2020.

I have been a practicing economist for more than 20 years and have been deeply humbled by COVID-19. Let’s just say that my uncertainty bands have grown quite wide, to use a favored term in economic forecasting. As in the aftermath of the Great Financial Crisis, the Great COVID-19 Recession has led me to scrap traditional forecasting models in favor of a deeper, qualitative analysis that takes me back to my theoretical roots and away from statistical models, proving once again that statistics can only get you so far in volatile and highly uncertain times.

On the more personal side, as an economist, I tend to lean toward an objective, dispassionate approach to life, but COVID-19 has tossed that tendency on its head. I have experienced the fear of the unknown much as many others have, with simple day-to-day actions like getting out of an apartment building safely becoming a heroic task. Still, I am humbled by the stark inequity of COVID-19 and the added stress it has placed on our essential workers. I have set up shop to work from home for the foreseeable future, experiencing the frustrations of connectivity and managing a team virtually, but recognize that I am fortunate to have the option of working from home.

On the other side of COVID-19, I will add this experience to my folio, which will make me a better forecaster. I will learn from this experience, as we all will. And most importantly for our profession, I will try to use this experience to impart wisdom to young economists entering the profession. We may be the dismal scientists, but those of us that live and practice through COVID-19 can strive to produce good from it.

Biographies

Diane Swonk

is Managing Director, Chief Economist, Grant Thornton LLC, where she sits on the Executive Leadership and Growth Strategy teams. She is an advisor to the Federal Reserve Board in Washington, D.C., sits on the Economic Advisory Panel of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, the Economic Advisory Group of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and is a member of the Council on Foreign Relations. Swonk sits on the Economic Advisory Board to the Economics Department of the University of Michigan and just completed three terms sitting on the Council for the Booth School of Business at the University of Chicago. She is a member of the Board for the NABE Foundation and the Chicago Advisory Board for the Posse Foundation. She is a past president of NABE and Certified Business Economist.

Lisa D. Cook

is Professor of Economics and International Relations at Michigan State University. Cook is Research Associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research. She is currently Director of the American Economic Association Summer Program. In 2019, she was elected to the Executive Committee of the American Economic Association.

Julia Coronado

is President and Founder of Macropolicy Perspectives. Coronado is a Clinical Associate Professor of Finance at the University of Texas at Austin and blogs for the Rutgers Business School. She is a member of the Economic Advisory Panel of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the Board of Directors of NABE, the Economic Studies Council at the Brookings Institution and the Board of Directors of Robert Half International. She serves on the Advisory Boards of the Pension Research Council at the Wharton School and the Cleveland Fed’s Center for Inflation Research. She is a Certified Business Economist.

Emily Kolinski Morris

is Chief Global Economist, Ford Motor Company. Kolinski is on the board of the Council for Economic Education. She previously served on the Board of Directors of NABE, was a past president of the Detroit chapter and is a Certified Business Economist.

Anna Paulson

is Executive Vice President and Director of Research at The Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. Paulson also has responsibility for the bank’s Public Affairs and Community, Development and Policy Studies departments. She attends meetings of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) and serves on the bank’s Executive Committee.

James M. Poterba

is the Mitsui Professor of Economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the President and CEO of the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). Poterba serves as a trustee of the College Retirement Equity Fund and the TIAA-CREF mutual funds. He is the past president of the National Tax Association and the Eastern Economic Association.

Claudia Sahm

runs her own consulting business and writes op-eds on economic policy for The New York Times and Bloomberg. While working as Section Chief at the Federal Reserve Board in Washington, D.C., she developed the “Sahm Rule,” a reliable early signal of recessions as a way to automatically trigger stimulus payments to individuals during a recession.

Michael R. Strain

is the Arthur F. Burns Scholar in Political Economy and Director of Economic Policy Studies at the American Enterprise Institute. Dr. Strain’s latest book, The American Dream is Not Dead: (But Populism Could Kill It) was published on February 28, 2020.

Ellen Zentner

is Managing Director, Chief US Economist, Morgan Stanley. Zentner is involved in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Economic Advisory panel, the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago’s Academic Advisory Panel, the American Bankers’ Association Economic Advisory Committee and the Economic Advisory Group to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. Zentner also sits on the Board of Directors of NABE and was president of the New York chapter.

Footnotes

These are the views of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago or the Federal Reserve System.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.