Abstract

Objective

To describe the frequency of cardiac complications during pregnancy related to parity in women with congenital heart defects.

Methods

A retrospective tertiary single-center study at the Adult Congenital Heart Disease Centre that followed 307 women with congenital heart disease during the years 1997–2015 in Gothenburg, Sweden. Maternal cardiac complications were noted for each pregnancy using medical and obstetric records. The CARPREG I and modified WHO (mWHO) risk classifications were used. Twin pregnancies, miscarriages before gestational week 13, and pregnancy terminations were excluded.

Results

Five hundred seventy-one deliveries and 9 late miscarriages were analyzed. The mean parity was 1.74 per woman (range 1–8). Eighty-four (14.6%) maternal cardiac complications were experienced; arrhythmia (5.7%) and heart failure (4.4%) being the most prevalent, and there was 1 maternal death. Heart failure occurred during the first pregnancy in 12 women (3.9%), in the second pregnancy in 8 women (4.3%), and in the third pregnancy in 4 women (7.7%). CARPREG I and mWHO scores were associated with an increased risk of having a cardiac complication, while parity per se was not associated. The OR for having a maternally uneventful second pregnancy if the first pregnancy was without cardiac complications was 5.47 (95% CI 1.76–16.94) after controlling for CARPREG I and mWHO scores.

Conclusion

The risk of severe maternal cardiac complications during pregnancy in women with congenital heart disease is low. In this largest analysis to date with a focus on parity in 307 women, the risk classification predicts the maternal outcome more than parity per se. If the first pregnancy is uneventful, the OR is 5.5 for an uneventful second pregnancy if CARPREG I and mWHO scores remain unchanged.

Keywords: Pregnancy, Parity, Outcome

Introduction

Recent studies show that women with congenital heart disease often tolerate pregnancy well [1, 2, 3]. Nevertheless, a small group of patients with a high maternal risk may be advised against pregnancy [4]. The available risk classifications and scoring systems combine diagnosis, findings, and cardiac history [5, 6, 7, 8]; however, the importance of parity, that is, the number of previous deliveries, or the risk of maternal cardiac complications during pregnancy in women with congenital heart disease is less well described. In prepregnancy counselling, women want to know the cardiac risk of having another pregnancy. In previous studies on parity, the reported outcomes have been mainly obstetric and neonatal complications in general population cohorts [9]. In the literature on congenital heart defects, either the cohorts often only include nulliparous women or the actual number of previous deliveries is not reported in cohorts with multiparous women. We conducted a retrospective analysis following the STROBE criteria (Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) [10] for observational studies in a cohort of pregnant patients with adult congenital heart disease (ACHD) with the aim of studying the effect of parity on maternal cardiac complications during each pregnancy. To our knowledge, our data to date comprise the largest series on women with congenital heart disease to evaluate the effect of parity on cardiac complications during pregnancy.

Methods

All consecutive pregnant patients with ACHD at the tertiary Adult Congenital Heart Disease Centre at Östra, Sahlgrenska University Hospital (Gothenburg, Sweden) between 1997 and 2015 were included. The population of the catchment area for this tertiary service is 4–5 million inhabitants from western and northern Sweden, but the majority of the participants live in the Gothenburg and western Sweden regions, with approximately 1.5 million inhabitants. Baseline data were collected from medical and obstetrical records and also include data reported in a previous work from our group [3]. In this study, parity was defined as the number of previous pregnancies reaching viable gestational age (including live births and stillbirths) and late miscarriage after 13 gestational weeks. Twin pregnancies (n = 6) were excluded. Miscarriages before gestational week 13 were excluded because the hemodynamic changes affecting heart function had not been longstanding and the aim of this study was to evaluate cardiac complications in relation to the supposed physiological changes from repeated pregnancies. All terminations of pregnancy were prior to gestational week 13 and were reported separately. Cardiac diagnosis, previous operations, age at pregnancy, data on previous pregnancies, biometric data, and smoking habits at the first antenatal visit were noted. One author (E.F.) retrospectively scored the patients using the CARPREG I and modified WHO (mWHO) risk classifications [5, 7]. See online supplementary Appendix 1 (for all online suppl. material, see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000508649) for details of the scoring classifications. Cardiac complications during pregnancy and within 42 days postpartum were noted for each pregnancy. We obtained additional information during 2 years of follow-up on maternal death, heart intervention, and new-onset heart failure. Data on deliveries and late miscarriages before the first visit to the ACHD centre were obtained from medical and obstetric records. AT baseline, patients with an atrial septum defect (ASD) were classified as “operated” if they had been operated on during childhood and as “nonoperated” if they were >18 years old when the ASD was closed. Some women with late repair of ASD had pregnancies before and after closure; therefore, we analyzed the outcome of every individual woman, and not the outcome of ASD pregnancies, to distinguish between the effects of longstanding hemodynamic stress in the women with late repair of ASD compared to short-term stress in the women with early repair of ASD. All patients with an operated ventricular septum defect or persistent ductus arteriosus had been operated on before the age of 18 years. Women with an operated ventricular septum defect and persistent ductus arteriosus were classified as one group at baseline because the hemodynamic effects of the defects are similar. Operated ASD and partial anomalous pulmonary vein drainage were classified as one group for the same reason. The “other complex” category includes: 7 women with an Ebstein anomaly, 1 with a total cavopulmonary connection, 2 with congenitally corrected transpositions, 2 with Eisenmenger syndrome, 1 with a nonoperated tetralogy of Fallot, 1 with carnitine deficiency, and 1 with cardiomyopathy of unknown cause. In the outcome analyses, the patients were classified by their CARPREG I and mWHO risk scores and were not analyzed according to the anatomic diagnosis because of the small number of patients in each diagnosis group.

Outcome Definitions

Cardiac complications during pregnancy and peripartum were defined as a composite of: (1) clinical signs of heart failure; (2) arrhythmia as documented by an electrocardiogram or a history regarded as significant by the ACHD cardiologist at the time of the event; (3) thromboembolic event documented in medical records; (4) echocardiographic changes during pregnancy not reversed at first follow-up; (4) syncope during pregnancy, regarded as potentially cardiac syncope by the ACHD cardiologist at the time of the event; (5) aortic dissection or rupture; or (6) maternal death within 42 days after delivery. Cardiac complications during 2 years of follow-up after delivery were defined as: (1) maternal death, (2) cardiac intervention (surgery or catheter), or (3) clinical signs of new-onset heart failure. Hypertensive disorders during pregnancy were not included in the cardiac complications. Obstetric outcomes included preterm birth (<37 gestational weeks), a low birth weight (<2,500 g), and perinatal mortality and postpartum hemorrhage (>1,000 mL). This study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board of Western Sweden.

Statistical Analysis

The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess normality among the continuous variables (age and BMI at the first antenatal visit). Where appropriate, normally distributed data are presented as means (±SD), and nonnormally distributed data are presented as medians (1st and 3rd IQR). The Fisher exact tests were conducted on categorical demographic data (i.e., CARPREG I, mWHO score, and smoking status) to compare cardiac complications versus no cardiac complications. The Student t test or the Mann-Whitney test (for nonnormally distributed data) was used for continuous variables in relation to cardiac complications at each pregnancy up to 42 days postpartum. All descriptive statistic analyses and significance testing were conducted using IBM SPSS statistical package version 25 (IBM SPSS, Armonk, NY, USA). In a nonadjusted longitudinal model, cardiac complications during the second childbirth were predicted from cardiac complications during the first childbirth, and cardiac complications during the third to eighth childbirths were predicted from cardiac complications during the second childbirth.

Three separate multivariable logistic regression analyses were conducted to estimate the effects of the continuous and categorical variables on cardiac complications using the Mplus MLR estimator [11]. The multicollinearity assumption was tested, since CARPREG I and WHO scores could be highly correlated. These correlations were found to be modest (ranging from 0.31 to 0.39) and variance inflation factor values indicated no problem with multicollinearity. The women were assigned to parity groups, that is, parity 1, 2, and ≥3. The parity 3–8 group was analyzed together as a common group because of the few women with numerous pregnancies. The missing data for BMI and smoking are reported in Table 1. The missing data on cardiac complications for each parity are reported in Figure 1. There was 1 missing CARPREG I score and no missing mWHO scores. The missing data and nonnormality in the models were estimated using robust full maximum-likelihood estimation. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Diagnosis | Parity |

Total, n | Mean age (SD, range), years | Median BMI, (IQR, range) | Smoking, n/total (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||||

| VSD (nonop) | 36 | 17 | 2 | 1 | 57 | 29.8 (5.7, 16–47) | 24.0 (4.3, 17–41) | 6/37 (16) |

| VSD/PDA (op) | 15 | 9 | 2 | 0 | 26 | 30.0 (5.4, 19–42) | 23.6 (4.4, 18–35) | 2/20 (10) |

| ASD (nonop) | 24 | 16 | 6 | 2 | 50 | 29.2 (5.3, 17–40) | 24.5 (5.7, 18–37) | 4/28 (14) |

| ASD, PAPVR (op) | 17 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 28.5 (4.6, 20–41) | 24.3 (4.1, 21–37) | 1/13 (8) |

| AVSD (op) | 18 | 10 | 3 | 0 | 31 | 28.4 (5.0, 19–43) | 23.0 (6.9, 19–32) | 2/14 (14) |

| HCM | 8 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 14 | 32.1 (4.9, 22–39) | 21.5 (11.6, 20–35) | 0/4 (0) |

| Aortic valve stenosis | 20 | 14 | 6 | 3 | 45 | 29.5 (5.9, 20–42) | 24.9 (8.3, 18–43) | 2/34 (6) |

| AS/AR combined | 6 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 15 | 27.8 (6.6, 15–39) | 34.7 (16.0, 21–40) | 0/4 (0) |

| Aortic valve regurgitation | 15 | 12 | 3 | 2 | 35 | 30.9 (5.7, 20–42) | 23.2 (4.0, 20–46) | 2/16 (12) |

| Mitral stenosis | 7 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 15 | 30.9 (6.0, 20–43) | 25.3 (7.1, 22–33) | 0/9 (0) |

| Mitral regurgitation | 12 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 25 | 29.4 (7.7, 18–41) | 22.0 (6.5, 19–39) | 0/10 (0) |

| PS/PR combined | 26 | 18 | 9 | 3 | 62 | 29.3 (5.8, 17–42) | 22.6 (4.9, 18–42) | 1/26 (4) |

| Tetralogy of Fallot (op) | 14 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 23 | 29.0 (4.9, 21–38) | 30.1 (13.4, 18–39) | 1/10 (10) |

| Pulmonary atresia | 7 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 14 | 27.6 (4.8, 20–36) | 21.2 (8.9, 16–29) | 0/6 (0) |

| Coarctatio aortae | 33 | 20 | 4 | 1 | 58 | 30.1 (5.2, 21–44) | 23.6 (4.5, 16–37) | 3/38 (8) |

| Aortic disease | 26 | 16 | 3 | 1 | 46 | 29.5 (4.7, 21–38) | 22.9 (4.0, 16–35) | 1/34 (3) |

| Transposition (dTGA) | 8 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 14 | 26.8 (4.4, 18–34) | 25.0 (9.2, 21–32) | 0/6 (0) |

| Other complexa | 15 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 24 | 29.4 (5.7, 20–39) | 23.9 (6.6, 19–33) | 0/11 (0) |

| Total | 307 | 186 | 52 | 17 | 580 | 29.5 (5.5, 15–47) | 23.7 (5.4, 16–46) | 25/320 (8) |

Diagnoses, parity, and total number of pregnancies are shown. Age, BMI, and smoking are reported for each cohort of diagnoses. There were missing data on the BMI (n = 261) and smoking habits (n = 260) of 580 pregnancies. Pulmonary atresia only includes women operated on to a 2-chamber system. dTGA, transposition of the great arteries; all were operated atrial switch or Rastelli. op, operated; nonop, nonoperated; PDA, persistent ductus arteriosus; ASD, atrial septum defect; PAPVR, partial anomalous pulmonary vein return; AVSD, atrioventricular septum defect; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; PS/PR, pulmonary stenosis and/or pulmonary regurgitation.

Includes 7 women with an Ebstein anomaly, 1 total cavopulmonary connection, 2 congenitally corrected transposition, 2 cases of Eisenmenger syndrome, 1 nonoperated tetralogy of Fallot, 1 carnitine deficiency, and 1 cardiomyopathy of unknown cause.

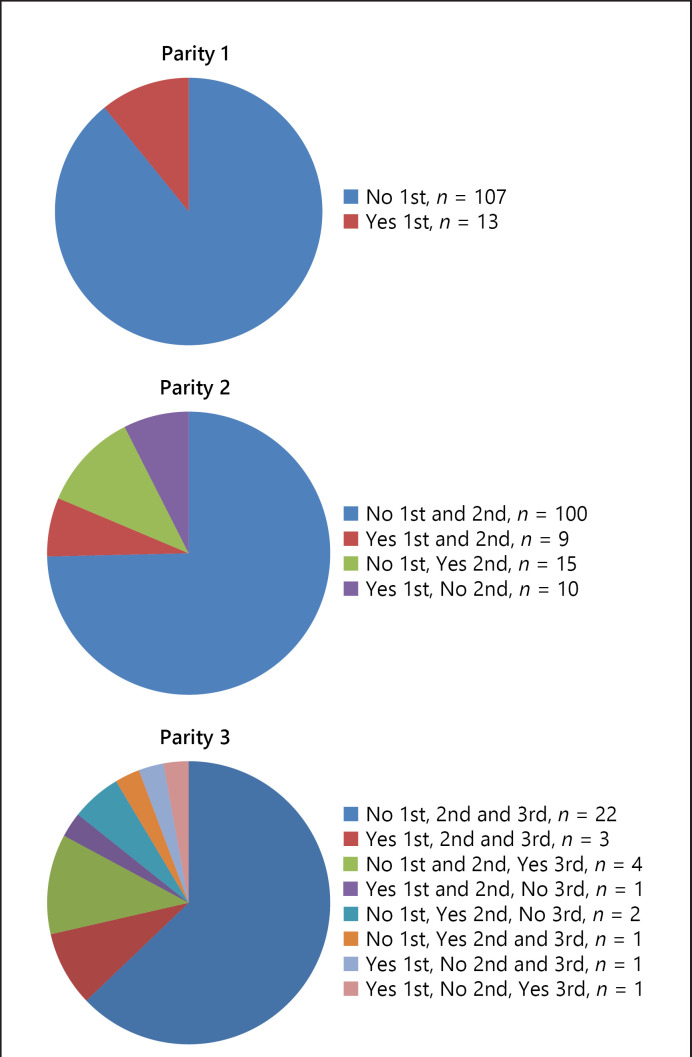

Fig. 1.

The distribution of maternal complications (Yes or No) during first (1st), second (2nd) or third (3rd) pregnancy in women with one, two or three pregnancies: Parity 1 (n = 120), Parity 2 (n = 134) or Parity 3 (n = 35).

Results

We identified 307 women with 571 deliveries and 9 late miscarriages. The mean parity was 1.74 per woman (SD 1.07, range 1–8). One hundred twenty women had 1 pregnancy, 134 women had 2 pregnancies, and 35 women had >2 pregnancies. The baseline data on cardiac diagnoses, parity and number of pregnancies, age, BMI, and smoking habits are reported in Table 1. In 22% of the pregnancies, the women were on cardiac medication, with the most common being β-blockers. For details, see online supplementary Appendix 2.

Cardiac Outcome during Pregnancy

Data on cardiac complications during pregnancy and within 42 days postpartum were available in 574 of the 580 pregnancies. There were 84 (14.6%) cardiac complications, with arrhythmia (n = 33; 5.7%) and heart failure (n = 25; 4.4%) being the most prevalent. There was 1 maternal death in gestational week 23 in a woman with a mechanical aortic prosthesis who also had a coronary embolus in gestational week 5. She was on therapeutic doses of low-molecular-weight heparin at the time of death and died from bleeding caused by a spontaneous rupture of an abdominal wall vessel. Vitality information on maternal life or death was obtained for all women. None of the women had an aortic dissection or rupture. Table 2 describes the distribution of age, BMI, risk scores (CARPREG I and mWHO), and smoking habits according to parity in women with or without cardiac complications during pregnancy. Age, BMI, and smoking did not differ between women with and without cardiac complications. The CARPREG I score was higher in women with cardiac complications in the first, second, and third pregnancies compared to women without complications. The mWHO classification was associated with cardiac complications in the first and third pregnancies.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for women during first, second and third pregnancies without (no) and with (yes) cardiac complication

| First (n = 305) |

Second (n = 185) |

Third (n = 51) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| no | yes | no | yes | No | yes | |

| Agea, years | 28.6 (5.5) | 28.5 (5.0) | 30.2 (4.8) | 31.4 (4.7) | 30.6 (6.4) | 32.7 (5.9) |

| BMIb (IQR) | 23.3 (4.4) | 22.6 (9.1) | 23.7 (4.6) | 24.7 (10.0) | 24.4 (5.6) | 28.1 (10.7) |

| Smokingc | ||||||

| Nonsmokers | 139 (86) | 14 (82) | 68 (85) | 17 (90) | 18 (78) | 5 (100) |

| Current smokers | 10 (6) | 2 (11) | 4 (5) | 1 (5) | 3 (13) | 0 (0) |

| Ex-smokers | 13 (8) | 1 (6) | 8 (10) | 1 (5) | 2 (9) | 0 (0) |

| CARPREG I riskc | ||||||

| 0 | 225 (82) | 14 (47) | 117 (79) | 14 (38) | 34 (90) | 4 (31) |

| 1 | 48 (18) | 13 (43) | 31 (21) | 20 (51) | 2 (8) | 9 (69) |

| 2 | 1 (0) | 2 (7) | 0 (0) | 3 (8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 3 | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| mWHO riskc | ||||||

| 1 | 116 (42) | 5 (17) | 66 (45) | 7 (19) | 22 (58) | 2 (15) |

| 2 | 74 (27) | 6 (20) | 34 (23) | 11 (30) | 8 (21) | 2 (15) |

| 2–3 | 67 (24) | 9 (30) | 38 (26) | 14 (38) | 6 (16) | 6 (46) |

| 3 | 17 (6) | 8 (27) | 10 (7) | 4 (11) | 2 (5) | 3 (21) |

| 4 | 1 (0) | 2 (7) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Values are presented as means ± SD or numbers (%) unless otherwise stated. The cohort includes 9 late miscarriages and 6 intrauterine deaths. Age, BMI, and smoking did not show a statistically significant difference between women with or without cardiac complications. Women with a cardiac complication had higher CAR-PREG I scores and mWHO scores (p < 0.05) than women without complications, except for mWHO scores in the second pregnancy, with p = 0.013. There were missing data on BMI (n = 261) and smoking (n = 260).

Student t test.

Mann-Whitney U test.

Fisher exact test.

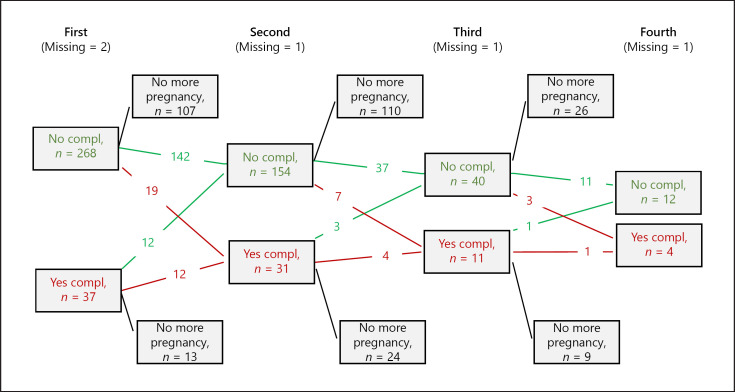

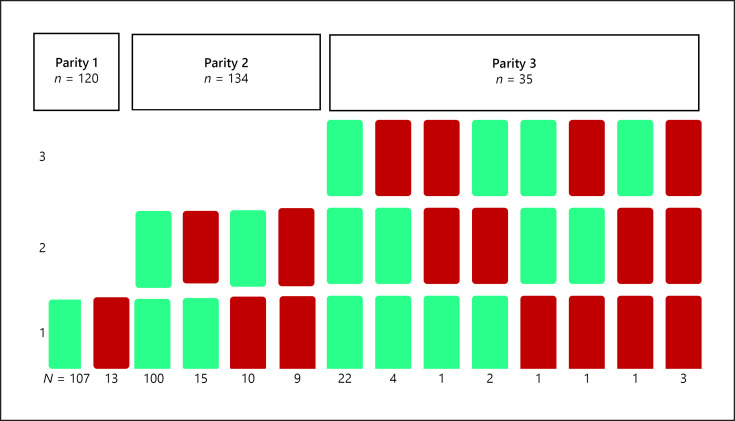

Data on cardiac outcomes during pregnancy in the 3 parity groups are reported in Table 3 and Figure 1. The proportion of women with cardiac complications at any pregnancy increased by parity from 12% of women in the parity 1 group, 17% in the parity 2 group, and 22% in the parity ≥3 group. Heart failure occurred during the first pregnancy in 12 women (3.9%), in the second pregnancy in 8 women (4.3%), and in the third pregnancy in 4 women (7.7%). Twenty-three women shifted from a lower to a higher CARPREG I score with increasing parity, while 12 women shifted from a lower to a higher mWHO score. There were 13 women who shifted from a higher to a lower mWHO score (e.g., when an ASD had been closed). Figure 2 presents a flowchart of the maternal outcome of each pregnancy. The missing data on cardiac complications were reported separately for each parity group. The distribution of maternal complications according to parity groups (1, 2, or ≥3) is shown in Figure 3. In our cohort, 17 women with >3 pregnancies had a total of 35 additional pregnancies. We could obtain data for 31 of these pregnancies, with 5 having maternal cardiac complications.

Table 3.

Bivariable (unadjusted) logistic regression analysis of the relationship between cardiac complications in the parity 1 group, the parity 2 group, and the parity 3–8 group and predictors

| Parity 1 |

Parity 2 |

Parity 3–8 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Age (years) | 1.02 | 0.96–1.08) | 1.05 | 0.97–1.14 | 1.03 | 0.93–1.14 |

| BMI | 1.03 | 0.93–1.14 | 1.02 | 0.91–1.15 | 1.00 | 0.84–1.19 |

| Smoking | ||||||

| Nonsmoker | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Ex-smoker | 0.65 | 0.08–5.29 | 0.71 | 0.08–6.27 | 1.80 | 0.13–24.16 |

| Smoker | 1.69 | 0.34–8.39 | 1.25 | 0.13–12.04 | 0.00 | NA |

| CARPREG I | ||||||

| Risk 0 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Risk 1 | 6.55* | 3.08–13.92 | 4.38* | 1.96–9.78 | 5.91* | 1.55–22.53 |

| Risk 2–3 | 42.56* | 4.19–432.78 | NA | NA | ||

| mWHO score | ||||||

| 1 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| 2 | 2.24 | 0.77–6.55 | 3.18* | 1.05–9.68 | 1.10 | 0.10–12.27 |

| 2–3 | 2.92* | 1.01–8.40 | 3.42* | 1.19–9.79 | 12.27* | 2.38–63.36 |

| 3 | 10.50* | 3.30–33.44 | 4.67* | 1.12–19.47 | 11.50* | 1.33–99.33 |

| 4 | 56.00* | 5.04–622.00 | NA | NA | ||

Age, BMI, and smoking habits were not associated with an increased risk of cardiac complications while CARPREG I and mWHO scores were statistically significant.

Significant (p < 0.05). Due to the small number of observations for some CARPREG scores and mWHO scores, it was not possible to retrieve any estimates. NA, not available.

Fig. 2.

Flowchart on cardiac complications in first (n = 307), second (n = 186), third (n = 52), and fourth (n = 17) pregnancy. 120 women had only one pregnancy, 134 women had two, and 35 women had three pregnancies. The missing data refer to cardiac complications except for death, where there are no missing data. Red arrows indicate cardiac complication in the next pregnancy; green arrows indicate no complication.

Fig. 3.

The distribution of cardiac complications during 1st, 2nd and/or 3rd pregnancies according to parity group for women in the groups Parity 1 (n = 120), 2 (n = 134) or 3 (n = 35) pregnancies. Green indicates no cardiac complications; red indicates yes cardiac complications.

In Table 3, a bivariable unadjusted logistic regression analysis shows the relationship between possible predictors of cardiac complications during the second pregnancy compared to the first pregnancy and for the third to eighth pregnancies compared to the second pregnancy. Age, BMI, and smoking habits were not associated with the risk of cardiac complications. Only variables that were significantly associated with complication in bivariate analysis for each time point were selected for the multiple regression analysis (i.e., CARPREG and WHO score).

The overall OR for having the same outcome, regarding cardiac complications, during the second pregnancy compared to the first pregnancy was 5.47 (95% CI 1.76–16.94), which is numerically smaller and not significant between the second and third to eighth childbirths (OR = 3.03; 95% CI 0.58–16.44) after controlling for CARPREG I and mWHO scores and considering all parities. Thus, if the woman had a first pregnancy without cardiac complications, it is likely that a second pregnancy will have the same outcome if the risk score remains unchanged.

Cardiac Outcome within 2 Years of Follow-Up

There were no maternal deaths within 2 years postpartum. The follow-up data on cardiac complications 2 years after the last pregnancy were available in 540 pregnancies (93%), with the majority of missing data being in women classified as CARPREG I = 0 and mWHO = I. During that interval, 13 women (4.2%, 13/307) underwent a heart intervention, with the majority (n = 9) being for closure of an ASD. The interventions were done either by surgery (n = 9) or via a catheter (n = 4) after the first (n = 6) or second (n = 7) pregnancy. New-onset heart failure affected 6 women within 2 years; 5 women were classified as mWHO III or IV at their latest pregnancy and 4 of the 6 women developed heart failure after their first pregnancy.

Obstetric Outcomes

Nine of the pregnancies ended with late miscarriage between 15 and 21 gestational weeks, but without maternal cardiac complications. There were 28 women with 36 terminations; 20 of the terminations were the woman's first pregnancy. Two of the terminations (before gestational week 13) were in women with previously unknown severe heart defects, i.e., 1 in the first pregnancy and 1 in the third pregnancy. Both had successful pregnancies after surgery. One termination was due to fetal noncardiac malformation. The majority of terminations were in women with low CARPREG I and mWHO scores during their subsequent pregnancy (28 with CARPREG I = 0 and 24 with mWHO lower than II–III). We found 88 (15%) obstetric complications in the cohort and 83 (15%) neonatal complications. The most prevalent obstetric complication was postpartum hemorrhage >1,000 mL (n = 57; 10%), and preterm birth (<37 gestational weeks) was the most prevalent neonatal complication (n = 46; 8%); 6 patients were iatrogenic. There were 38 (7%) neonates with a low birthweight <2,500 g. The mean birthweight was slightly higher (205 g) in the second pregnancy (3,485 g; SD = 38) compared to the first (3,280 g; SD = 41) pregnancy in the total cohort. There were 6 intrauterine fetal deaths between gestational weeks 22 and 36. Five of these 6 women did not have a cardiac complication. One intrauterine death was in the woman who died during her fourth pregnancy. The other 5 were in the women's first pregnancies and 3 of them had successful subsequent pregnancies during the observation time.

Discussion

We report the largest series to date of 307 women with congenital heart disease to evaluate the effect of parity on cardiac complications during pregnancy. The parity in our cohort (1.74 per woman) was similar to that in the general population in Sweden during the same period (1997–2015), i.e., 1.76 per woman [12]. We only included women with ACHD who had had at least 1 pregnancy. Some women have infertility problems or chose not to have children due to their heart defect. The parity among a general ACHD population might therefore be even lower. Women are likely to have a cardiac event-free second pregnancy if their first pregnancy was without cardiac complication. In contrast, when their first pregnancy was complicated by a cardiac maternal event, then the risk is quite high that women will also have a cardiac complication during their second pregnancy. Similar results were found in a study on women with cardiac disease with at least 2 pregnancies where the risk for cardiac complications during the first and second pregnancies was studied [13]. Of the 77 women with cardiac disease in that study, 9% had cardiac complications during the first pregnancy and 6% had cardiac complications during the second pregnancy; the difference was not statistically significant. We found that the CARPREG I and mWHO risk scores were associated with higher OR of cardiac complications with higher scoring as described previously [14]. There was no clear signal indicating that parity per se was associated with a higher risk of having a cardiac complication during subsequent pregnancies, which is valuable information in prepregnancy counselling (Table 3). There was an increasing proportion of women with cardiac complications with parity, which indicates that there may be a shift from lower to higher scoring by time and/or previous pregnancies. Cardiac interventions, which might increase the possibility of favorable outcomes during the next pregnancy, as well as heart failure, which obviously decrease the chances, occurred within 2 years after the last pregnancy. It seems reasonable to rescore patients after every pregnancy. Obesity, advanced maternal age and smoking are known risk factors for adverse obstetric and neonatal outcomes [15, 16, 17]. We could not show an association between these factors and an adverse cardiac outcomes, but our study was limited to a certain degree by missing data on BMI and smoking habits. An association between parity and late ischemic heart disease has been described previously [18]. We analyzed cardiac complications for every pregnancy in this study, but we did not analyze late cardiac complications.

Study Limitations and Strengths

The scoring into risk classifications was retrospective, which is a limitation. We did not have all of the data to be able to classify all patients according to CARPREG II scores. Searching medical and obstetrical records is possible due to the Swedish individual 10-digit social security number. Information on previous history can be found in most cases, which is why we believe that the scores are correct. We had relatively few women in the highest risk classifications, which is why the overall risk for cardiac complications may be underestimated. There were few women with a parity >3, which affected the analyses. The missing data on BMI and smoking habits makes it difficult to interpret their impact on these results.

We had no missing data on age or mortality (up to 2 years postpartum) and there were few missing data on cardiac complications. We reported the number of women and not the number of pregnancies because data from individuals are easier to interpret when giving prepregnancy counselling. This is a single-center study; therefore, we could identify every woman from their medical records and reliably report on their parity status and cardiac complication rates.

Future research on the long-term effects of cardiac complications during pregnancy, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, and parity in women with congenital heart disease will improve prepregnancy counselling.

Conclusion

In this single-cente cohort study, the risk of severe maternal cardiac complications during pregnancy in women with congenital heart disease is low. In this largest analysis to date including 307 women with a focus on parity, the risk classification predicts maternal outcomes more than parity per se. If the first pregnancy was uneventful, the OR is 5.5 for an uneventful second pregnancy if CARPREG I and mWHO scores remain unchanged.

Statement of Ethics

This study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board of Western Sweden and it was conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association's 2013 Declaration of Helsinki.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Funding Sources

This study was financed by grants from the Swedish state under the ALF agreement between the Swedish government and county councils (grant No. 236611). This study was also financed by the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation (grant No. 20150774). These funding sources were not involved in the data collection, analysis, or interpretation of the results.

Author Contributions

The authors contributed to the design of this study, and to revision and approval of this paper, and they are are accountable for all aspects of this work. The authors take responsibility for all aspects of the reliability and freedom from bias of the data presented and their discussed interpretations.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Acknowledgements

We thank Elias Johannesson (University of Gothenburg) for statistics, Marie Jussila (ACHD/GUCH, Sahlgrenska University Hospital/Östra) for database registration, and Helena Dellborg and Görel Hultsberg-Olsson (Sahlgrenska University Hospital/Östra) for database administration.

References

- 1.Roos-Hesselink JW, Ruys TP, Stein JI, Thilén U, Webb GD, Niwa K, et al. ROPAC Investigators Outcome of pregnancy in patients with structural or ischaemic heart disease: results of a registry of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2013 Mar;34((9)):657–65. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jastrow N, Meyer P, Khairy P, Mercier LA, Dore A, Marcotte F, et al. Prediction of complications in pregnant women with cardiac diseases referred to a tertiary center. Int J Cardiol. 2011 Sep;151((2)):209–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Furenäs E, Eriksson P, Wennerholm UB, Dellborg M. Effect of maternal age and cardiac disease severity on outcome of pregnancy in women with congenital heart disease. Int J Cardiol. 2017 Sep;243:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.04.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Regitz-Zagrosek V, Roos-Hesselink JW, Bauersachs J, Blomström-Lundqvist C, Cífková R, De Bonis M, et al. ESC Scientific Document Group 2018 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy. Eur Heart J. 2018 Sep;39((34)):3165–241. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siu SC, Sermer M, Colman JM, Alvarez AN, Mercier LA, Morton BC, et al. Cardiac Disease in Pregnancy (CARPREG) Investigators Prospective multicenter study of pregnancy outcomes in women with heart disease. Circulation. 2001 Jul;104((5)):515–21. doi: 10.1161/hc3001.093437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drenthen W, Boersma E, Balci A, Moons P, Roos-Hesselink JW, Mulder BJ, et al. ZAHARA Investigators Predictors of pregnancy complications in women with congenital heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2010 Sep;31((17)):2124–32. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thorne S, MacGregor A, Nelson-Piercy C. Risks of contraception and pregnancy in heart disease. Heart. 2006 Oct;92((10)):1520–5. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.095240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silversides CK, Grewal J, Mason J, Sermer M, Kiess M, Rychel V, et al. Pregnancy Outcomes in Women With Heart Disease: the CARPREG II Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 May;71((21)):2419–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luke B, Brown MB. Elevated risks of pregnancy complications and adverse outcomes with increasing maternal age. Hum Reprod. 2007 May;22((5)):1264–72. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, STROBE Initiative The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg. 2014 Dec;12((12)):1495–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User's Guide, 8 ed. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Statistiska Centralbyrån Statistiska Centralbyrån. 2019. [updated 20190301. Available from: http://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/sv/ssd/START__BE__BE0101__BE0101H/FoddaK.

- 13.Gelson E, Curry R, Gatzoulis MA, Swan L, Lupton M, Steer PJ, et al. Maternal cardiac and obstetric performance in consecutive pregnancies in women with heart disease. BJOG. 2015 Oct;122((11)):1552–9. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim YY, Goldberg LA, Awh K, Bhamare T, Drajpuch D, Hirshberg A, et al. Accuracy of risk prediction scores in pregnant women with congenital heart disease. Congenit Heart Dis. 2019 May;14((3)):470–8. doi: 10.1111/chd.12750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Catalano PM, Shankar K. Obesity and pregnancy: mechanisms of short term and long term adverse consequences for mother and child. BMJ. 2017 Feb;356:j1. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heazell AE, Newman L, Lean SC, Jones RL. Pregnancy outcome in mothers over the age of 35. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Dec;30((6)):337–43. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crume T. Tobacco Use During Pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Mar;62((1)):128–41. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lawlor DA, Emberson JR, Ebrahim S, Whincup PH, Wannamethee SG, Walker M, et al. British Women's Heart and Health Study. British Regional Heart Study Is the association between parity and coronary heart disease due to biological effects of pregnancy or adverse lifestyle risk factors associated with child-rearing? Findings from the British Women's Heart and Health Study and the British Regional Heart Study. Circulation. 2003 Mar;107((9)):1260–4. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000053441.43495.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data