Abstract

Background:

A split-mouth longitudinal study was conducted to compare and evaluate the effect of ozonated water and photodynamic therapy (PDT) in nonsurgical management of chronic periodontitis, along with mechanical debridement procedure.

Materials and Methods:

Twenty-two patients diagnosed with chronic generalized periodontitis were subjected to the study. Following the assessment of gingival index, periodontal pocket depth, and clinical attachment loss, all patients underwent full-mouth scaling and root planing. Upper right and left quadrants of each patient were considered as sample sites in the study. Among these split-mouth sites, upper right quadrant of each patient was subjected to ozonated water irrigation with a 22-gauge needle and left upper quadrant was treated with PDT, which involved sulcus irrigation with indocyanine green dye (0.05 mg/ml) followed by low-level diode laser light application at 0.5 W and 810 nm (AMD Picasso) through a fiber-optic tip of 10 mm length, default angle of 60°, and fiber core diameter of 400 μm in noncontact continuous wave mode. Patients were recalled at the 2nd and 4th months regularly, and the therapy was repeated at the same sites in the same manner. Clinical parameters recorded before the study were assessed again at the end of the 2nd- and 6th-month period.

Results:

A statistically significant reduction (P < 0.05) was observed in gingival index scores within both the study groups at all intervals of the study. In Ozone therapy (OT) group, a statistically significant difference was noted for total periodontal pocket depth values between baseline and 2nd month (P = 0.000), baseline and 6th month (P = 0.000), and between 2nd month and 6th month (P = 0.029). In the PDT group, on contrary, a statistically significant difference was noticed in total periodontal pocket probing depth values between baseline and 2nd month (P = 0.000) and baseline to 6th month (P = 0.000), but a similar significant difference was not noticed between 2nd-month and 6th-month periods (P = 0.269). In group OT, a statistically significant difference was noted for total clinical attachment loss between baseline and 2nd month (P = 0.000), baseline and 6 months (P = 0.000), and 2nd month and 6th month (P = 0.019). In group PDT, a statistically significant difference in terms of its improvement was noted at intervals between baseline and 2 months (P = 0.000) and from baseline to 6 months (P = 0.000) but not between 2nd month and 6th month (P = 0.129).

Conclusion:

Results of the study showed that sub-gingival OT and PDT equally improved the clinical outcomes of treatment drastically following mechanical debridement at the end of first 2 months. Thereafter, it was shown to improve steadily throughout the study period, with slightly better results with OT compared with PDT.

Keywords: Chronic periodontitis, nonsurgical therapy, ozone therapy, photodynamic therapy

INTRODUCTION

Periodontal health is a consequence of everyday management of gingival sulcus and surrounding tissue architecture. This needs a constant maintenance therapy regimen specially designed for each individual, especially in patients with deeper gingival sulcus. The limited access to routine oral hygiene measures often hampers achievement of a thorough plaque-free environment. Mechanical debridement with adjunctive use of chemotherapeutic agents has forever been the conventional practice in periodontal therapy.[1] The usage of many such antimicrobial agents resulted in the development of bacterial antimicrobial resistance, inducing undesirable interactions with other drugs to cause adverse effects and even elicited hypersensitivity in host. Thus, the usage of such agents was limited to selected cases, wherein they are deemed inevitable. This has led to the alternative usage of various other adjunctive therapies involving least chemotherapeutic agents along with conventional techniques of scaling and root planing (SRP).

Among the available noninvasive therapies to achieve better plaque control, photodynamic therapy (PDT) and ozonated water therapy (OT) are being widely recognized as two reliable techniques. PDT using low-level laser irradiation is known to selectively target the periodontal pathogens without potentially damaging the host tissues.[2] The reaction of a photosensitizer agent like indocyanine green (ICG), with laser light of appropriate wavelength in the presence of oxygen, helps in generating free radicals and singlet oxygen, which in turn damage DNA and cytoplasmic membrane of the pathogen.[3] Results of several clinical studies have acknowledged the beneficial effects of PDT in patients with chronic periodontitis.[4,5,6]

The unique properties, noninvasive nature, versatility, relatively little side effects, and adverse reactions make ozone therapy an effective tool in the treatment of periodontitis. Ozone therapy, amid its antimicrobial, analgesic, immunostimulating, immune-modulatory, and anti-inflammatory properties, it also oxygenates tissues, elevates their functional activity, and enhances their regeneration potential.[7] Ozonated water at a concentration of 0.5–4 mg/L has been proven to strongly inhibit the formation of dental plaque.[8] It is also an established antimicrobial agent for subgingival irrigation in patients with chronic periodontitis.[9]

These two techniques have been exclusively studied proving its efficacy in nonsurgical therapeutics in managing periodontitis. Little studies have compared the effectiveness of these two systems when used along with normal plaque-control regimen. The present split-mouth study is one of its kind, attempting to ascertain whether OT can assure a similar or comparable clinical result as the complex and expensive PDT, in nonsurgical management of chronic periodontitis.

The aim of the study was to evaluate the therapeutic effect of OT and PDT when used along with mechanical debridement in nonsurgical management of chronic periodontitis. The objectives of the study were (1) to assess and compare the periodontal status of patients following one-time usage of OT and PDT along with conventional mechanical debridement in the management of chronic periodontitis at the end of 2 months and (2) to assess and compare the periodontal status of patients among the OT and PDT groups after 6 months following bi-monthly exclusive application of respective therapy repeated frequently without mechanical debridement in the management of chronic periodontitis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample selection for the study followed the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki on clinical research involving human subjects. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants of the study.

The sample size was calculated as per formula:

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 19 (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA). Patients with chronic generalized periodontitis with at least 4–5 areas having periodontal pockets with depths ranging between 3 mm and 10 mm on both right and left maxillary quadrants were considered for the study. The sample size was fixed to be 22 patients with their both sides of upper arches considered for split-mouth examination. Significance level was set at P ≤ 0.05 (with a 95% level of confidence).

Sample selection criteria: systemically and physically healthy patients between the age groups of 45 and 70 years with all dentition up to second molar teeth present in each upper quadrant were selected for the study. Patients received any antimicrobial therapy in the past 3 months, and patients with ongoing deleterious habits were avoided from the study.

In the first visit, a detailed case history of each patient was recorded to standardize the samples as chronic periodontitis patients as per the classification of periodontal diseases and conditions by the American Academy of Periodontology,[10] by assessing periodontal status of the patient using gingival index,[11] periodontal pocket probing depth, and clinical attachment level scorings.[12] The patients were detailed about the study and rendered proper oral hygiene instructions and asked to report for the therapy. It was a double-blinded study in which all the parameters were assessed and recorded by a single examiner throughout the study.

In the convenient next visit within 2 weeks, all patients were scheduled for respective treatments. The two quadrants in the upper arches were separated into two sample sites, and the gingival index score, periodontal pocket depth, and clinical attachment loss in each quadrant were recorded. Each of these scores was summed up, and a total score of each parameter at respective sites was taken into consideration for future comparisons.

One of the quadrants in every case was considered for PDT and the other quadrant was reserved for OT with equal distribution of right and left quadrants alternatively for both therapies. Adjacent quadrant was isolated each time with cotton rolls when exposing the other site for the study.

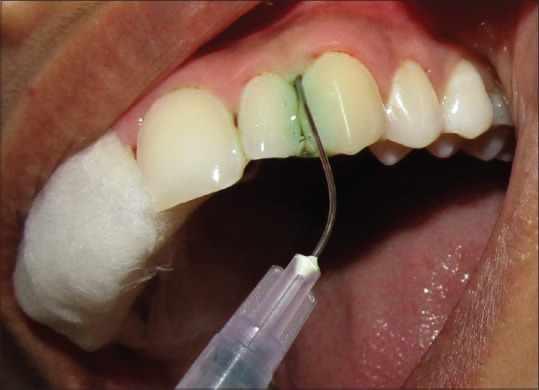

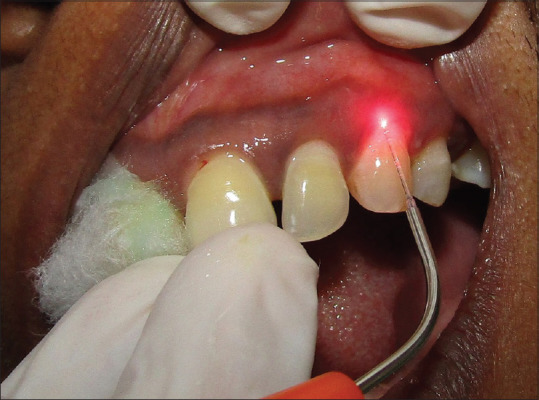

Full-mouth thorough SRP was performed in every case. Following this, one of the quadrants of each case was rinsed with the photosensitizer (ICG dye) for PDT. ICG dye has been used as a photosensitizer owing to its ideal properties and is having a wide optical absorption band from 600 to 810 nm with peak absorption at 800–810 nm. ICG dye is also not found to have a chemical alteration in the body and is rapidly excreted in bile. The dye was delivered using a 22-gauge needle, guided along the bottom of the pocket by continuous horizontal movements to achieve a complete flushing of the pocket. Flushing with the photosensitizer was restricted to 30 s at each site[Figure 1].[13] Following this, pockets were exposed to low-level laser light 810 nm at 0.5 W using an AMD Picasso diode laser equipment (AMD Lasers, LLC; 7405 Westfield Blvd, Indianapolis, IN, USA). The laser was delivered using a fiber-optic application having a tip of 10 mm length, with a default angle of 60°, and fiber core diameter of 400 μm. Irradiation settings employed the standard prescribed method of 0.5 W for 1 min in noncontact continuous wave mode.[13,14,15,16] Laser beam was guided like an ultrasonic probe from the pocket bottom to the gingival margin under continuous horizontal movements in order to ensure that all areas of the pocket were irradiated [Figure 2].[16] Photosensitizer was then removed thoroughly by flushing with sterile water along with vacuum evacuation. Every care of isolation was advocated to prevent the material being contaminating the adjacent quadrants in the same arch. Following this, the other quadrant was prepared for OT. The patient was allowed to wash and gargle the mouth with normal water.

Figure 1.

Irrigation of the sulcus using indocyanine green dye in the upper left quadrant

Figure 2.

Low-level laser application following indocyanine green dye irrigation in the upper left quadrant

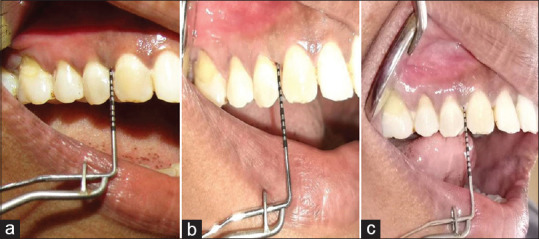

Subgingival irrigation with ozonated water with an oral irrigation device (Kent Ozone Dental Jet TY-820) was performed in this quadrant. The irrigation was delivered using a 22-gauge needle attached to the tip of its nozzle to standardize the method of delivery as done with photosensitizers in laser therapy [Figure 3]. A total time of 5–10 min was spent for irrigation of the sample site.[9] The device possesses an ozone output of 0.082 mg/h, and it was delivered in a single pulsating stream of water. Overflowing ozonated water was evacuated with cotton rolls and high power vacuum suction was used to prevent it from contaminating other sites of the study.

Figure 3.

Ozonated water irrigation in the upper right quadrant

At the completion of 2 months, each of these 22 patients was recalled to estimate gingival index, total periodontal pocket probing depth, and total clinical attachment loss separately on both sides of upper arch under the study in a similar way. After recording and tabulating the same, therapy using the same agents was repeated in the same manner in the respective sites without mechanical debridement.

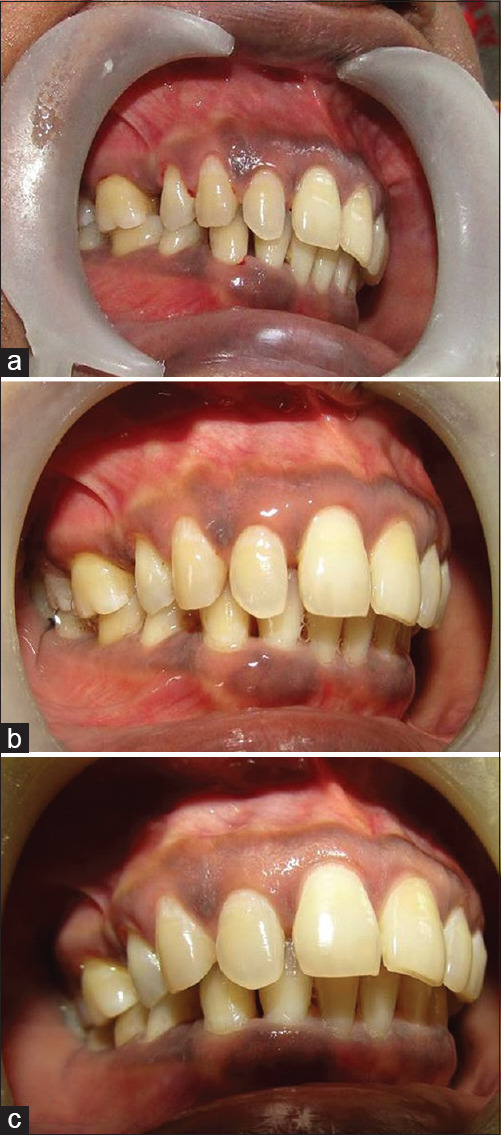

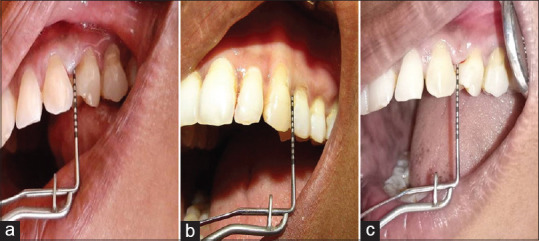

Patients were then recalled at the end of 4th month from the start of study to repeat the therapy in similar way without mechanical debridement. At the end of the 6th month from the start of the study, all parameters were assessed once again. The data were obtained at the beginning of the study when respective therapy was carried out along with mechanical debridement, and the scores at various intervals of the 2nd-, 4th-, and 6th-month time period were tabulated for comparison and evaluation [Figures 4-7].

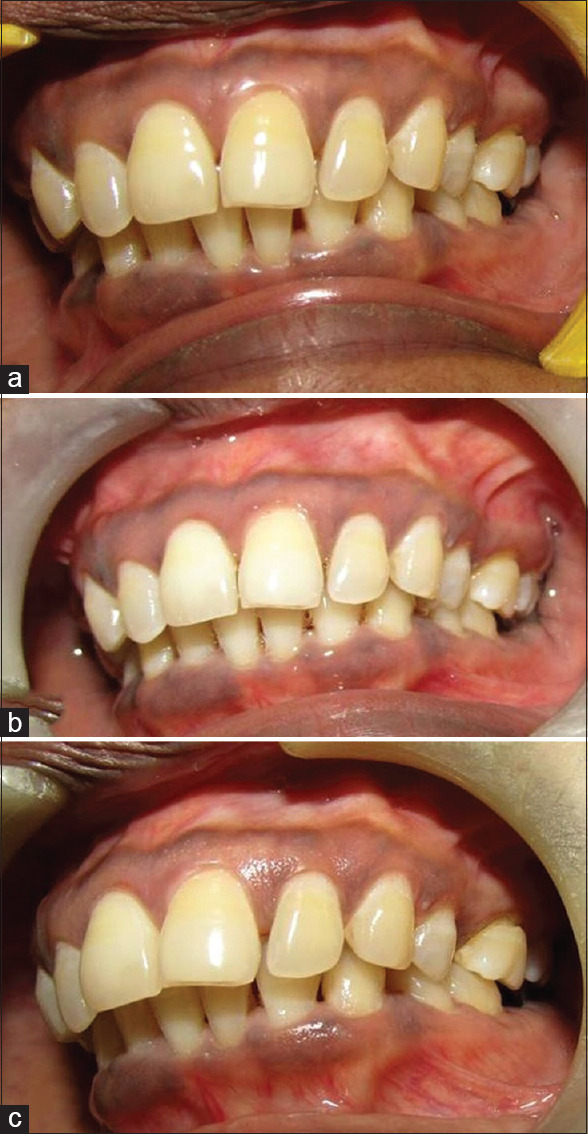

Figure 4.

Case 1 upper right quadrant (ozonated water therapy group) – (a) preoperative view; (b) after 2 months; (c) after 6 months

Figure 7.

Case 2 probing depth evaluation of the upper left quadrant (photodynamic therapy group) – (a) preoperative view; (b) after 2 months; (c) after 6 months

Figure 5.

Case 1 upper left quadrant (photodynamic therapy group) – (a) preoperative view; (b) after 2 months; (c) after 6 months

Figure 6.

Case 2 probing depth evaluation of the upper right quadrant (ozonated water therapy group) – (a) preoperative view; (b) after 2 months; (c) after 6 months

RESULTS

The values of gingival index, periodontal pocket probing depth, and clinical attachment loss of each quadrant of all 22 patients were summed up to obtain the total score following application of each agent. Thereafter, the mean score of this value against the 22 samples was obtained and used for comparison. The repeated measures ANOVA was used to assess the changes in different clinical parameters within the groups at intervals from baseline to 2nd and 6th months. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. The values were also compared among both the groups at all intervals.

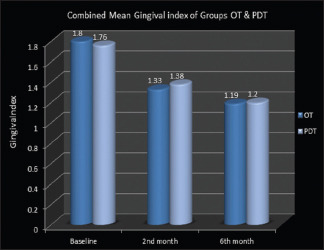

Mean gingival index scores decreased drastically from 1.8041 ± 0.17 to 1.3395 ± 0.25 at the end of the 2nd month and later into 1.1995 ± 0.09 at 6th months in group OT, whereas in group PDT, mean scores reduced from 1.7618 ± 0.18 to 1.385 ± 0.17 in the 2nd month and further to 1.2059 ± 0.11 in 6 months [Graph 1]. Thus, a clear improvement in gingival index scores was noticed over the observation periods of every 2 months (P = 0.000) in both the groups.

Graph 1.

Combined mean gingival index of ozonated water therapy and photodynamic therapy groups

However, split-mouth intercomparison of gingival index scores between the two groups did not reveal much change. Considerable reduction was seen after 2 months and 6 months within both the treatment groups with a greater reduction at the first interval which followed the assessment after mechanical debridement. However, this finding was consistent in both the groups at all intervals.

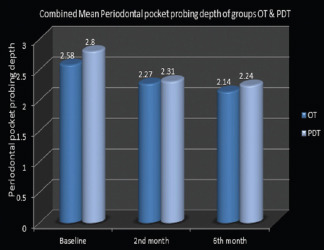

Among the total periodontal pocket probing depth assessment in each quadrant, group OT showed a change in mean total pocket depth values of sample sites from 2.58 ± 0.33 to 2.27 ± 0.27 in the 2nd month and to 2.14 ± 0.28 in the 6th month. Mean pocket depth values reduced from 2.8 ± 0.28 to 2.31 ± 0.30 in 2 months, which again reduced to 2.24 ± 0.33 in 6 months in the PDT group [Graph 2]. In group OT, a statistically significant difference was noted for total periodontal pocket depth values between baseline and 2nd month (P = 0.000), baseline and 6th month (P = 0.000), and 2nd month and 6th month (P = 0.029). In the PDT group, on contrary, a statistically significant difference was noticed in total periodontal pocket probing depth values between baseline and 2nd month (P = 0.000) and from baseline to 6th month (P = 0.000), but a similar significant difference was not noticed between 2nd-month and 6th-month periods (P = 0.269). Intercomparison of total periodontal pocket probing depth values between the two groups did not reveal much changes.

Graph 2.

Combined mean periodontal pocket probing depth of ozonated water therapy and photodynamic therapy groups

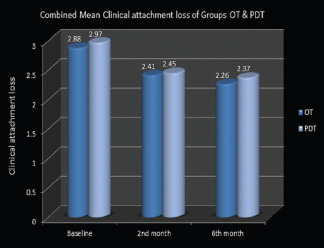

Mean total clinical attachment loss values in group OT reduced from 2.88±0.47 to 2.41±0.37 in two months and again reduced further to 2.26±0.31 in six months. Whereas, in group PDT, mean of total clinical attachment loss values decreased to 2.97 ± 0.34 in the first 2 months from 2.45 ± 0.31, which gradually reduced to 2.37 ± 0.34 at the 6th month [Graph 3]. In group OT, a statistically significant difference was noted for total clinical attachment loss between baseline and 2nd month (P = 0.000), baseline and 6 months (P = 0.000), and 2nd month and 6th month (P = 0.019). In group PDT, a statistically significant difference in terms of its improvement was noted at intervals between baseline and 2 months (P = 0.000) and from baseline to 6 months (P = 0.000) but not between 2nd month and 6th month (P = 0.129).

Graph 3.

Combined mean clinical attachment loss of ozonated water therapy and photodynamic therapy groups

Intercomparison of total clinical attachment loss values among the OT and PDT groups did not exhibit any change like the gingival index and probing depth assessments. Regarding the clinical attachment gain, considerable gain was seen at the 2nd month and at the 6th month in both the treatment groups with a greater reduction at the end of the 2nd month which immediately followed mechanical debridement along with respective therapy.

DISCUSSION

Ozone therapy and PDT are two proven antimicrobial treatment options in patients with chronic periodontitis intended for nonsurgical periodontal therapy. However, studies comparing the effectiveness of these two treatments were hardly found in literature. The present study observed that clinical parameters such as gingival index, total periodontal pocket score, and total clinical attachment loss were found to favor both the techniques almost similarly and exhibited excellent clinical improvements.

Gaseous Ozone has been proven to exhibit strong antibacterial activity against putative periodontopathic microorganisms.[17] An in vitro study by Huth et al. to investigate the antimicrobial potential of ozone in comparison with chlorhexidine gluconate showed that there was no significant difference in the effectiveness of aqueous or gaseous ozone and that of 2% chlorhexidine gluconate.[18] Observations from randomized controlled clinical trial revealed significant reduction in percentage of sites with bleeding on probing, mean plaque index, mean probing pocket depth & mean clinical attachment loss by the adjunctive use of ozonated water irrigation with SRP.[19] Moreover, another study by Kshitish & Laxman reported that ozone might be considered as an alternative management strategy in treatment of periodontitis due to its powerful antimicrobial potency.[9] Statistically significant improvements (P < 0.05) in gingival index values, periodontal pocket probing depth, and attachment gain were found with ozone therapy at all study intervals in the current study. Similar outcomes were demonstrated in a randomized controlled trial by Hayakumo et al., using ozone nanobubble-water therapy, wherein periodontal pocket depth reduction and attachment gain were obtained at 4-week and 8-week intervals.[20] Findings from microbiological assessment also support the use of ozone as an effective adjuvant in managing moderate-to-severe chronic periodontitis.[21] Yilmaz et al. in their investigations suggested that gaseous ozone has an antimicrobial effect equivalent to that of Er:YAG laser.[22]

Several clinical studies have been conducted combining PDT with mechanical debridement and have reported mixed outcomes. Although few studies demonstrated a significant improvement in clinical parameters with the adjunctive use of PDT coupled with SRP compared to SRP alone,[4,5,23] a couple of studies[14,24,25] found that the adjunctive use of PDT yielded no significant benefits. In the current study, it was observed that there was a statistically significant difference in the clinical parameters at the intervals of 2 months and at 6 months following the study, with the baseline parameters obtained before the application of PDT. However, such significant differences were not observed in total periodontal pocket depth and attachment gain between the observations registered after 2 months and that observed after 6 months of the study when PDT was used alone without repeating the SRP. Despite the abundance of promising data on the advantages of their use, there is still controversy regarding the real benefits of PDT in the treatment of periodontal disease.

This study was the first of its kind to investigate the long-term clinical effects of PDT and OT when repeated frequently without mechanical debridement except the first time in nonsurgical management of chronic periodontitis. None of the studies conducted so far have considered a comparative evaluation of these two techniques with application at frequent intervals and in a split-mouth manner. A better study design with added biochemical and microbiological assays and longer duration would be required to evaluate the potential use of OT and PDT as an adjunct to nonsurgical management of chronic periodontitis in routine clinical conditions.

CONCLUSION

Observations made in the present study revealed no statistically significant difference in clinical parameters between OT and PDT when assessed after 2 months, 4 months, and 6 months, though slightly better clinical result was observed in ozone therapy. Improvement in clinical parameters obtained in the current study suggests the beneficial role of repeated application of PDT and OT at frequent intervals of time for needed individuals.

Apart from these limitations observed in the present study, it shall be concluded that ozone therapy and PDT are valuable tools of nearly the same efficiency in nonsurgical treatment of chronic periodontitis, with OT observed to exhibit consistent superior results at all intervals of time over PDT.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gupta M, Abhishek GM. Ozone: An emerging prospect in dentistry. Indian J Dent Sci. 2012;4:47–50. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khan NS, Beegum F. Photodynamic therapy: A targeted therapy in periodontics. Int J Laser Dent. 2014;4:26–30. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Konopka K, Goslinski T. Photodynamic therapy in dentistry. J Dent Res. 2007;86:694–707. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersen R, Loebel N, Hammond D, Wilson M. Treatment of periodontal disease by photodisinfection compared to scaling and root planing. J Clin Dent. 2007;18:34–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braun A, Dehn C, Krause F, Jepsen S. Short-term clinical effects of adjunctive antimicrobial photodynamic therapy in periodontal treatment: A randomized clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35:877–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sgolastra F, Petrucci A, Severino M, Graziani F, Gatto R, Monaco A. Adjunctive photodynamic therapy to non-surgical treatment of chronic periodontitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol. 2013;40:514–26. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seidler V, Linetskiy I, Hubálková H, Stanková H, Smucler R, Mazánek J. Ozone and its usage in general medicine and dentistry. A review article. Prague Med Rep. 2008;109:5–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagayoshi M, Fukuizumi T, Kitamura C, Yano J, Terashita M, Nishihara T. Efficacy of ozone on survival and permeability of oral microorganisms. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2004;19:240–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.2004.00146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kshitish D, Laxman VK. The use of ozonated water and 0.2% chlorhexidine in the treatment of periodontitis patients: A clinical and microbiologic study. Indian J Dent Res. 2010;21:341–8. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.70796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Armitage GC. Development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:1–6. doi: 10.1902/annals.1999.4.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loe H, Silness J. Periodontal disease in pregnancy I Prevalence and severity. Acta Odontol Scand. 1963;21:533–51. doi: 10.3109/00016356309011240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramfjord SP. The periodontal disease index (PDI) J Periodontol. 1967;38(Suppl):602–10. doi: 10.1902/jop.1967.38.6.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagahara A, Mitani A, Fukuda M, Yamamoto H, Tahara K, Morita I, et al. Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy using a diode laser with a potential new photosensitizer, indocyanine green-loaded nanospheres, may be effective for the clearance of Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Periodontal Res. 2013;48:591–9. doi: 10.1111/jre.12042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Polansky R, Haas M, Heschl A, Wimmer G. Clinical effectiveness of photodynamic therapy in the treatment of periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2009;36:575–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.2009.01412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lulic M, Leiggener Görög I, Salvi GE, Ramseier CA, Mattheos N, Lang NP. One-year outcomes of repeated adjunctive photodynamic therapy during periodontal maintenance: A proof-of-principle randomized-controlled clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol. 2009;36:661–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2009.01432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rühling A, Fanghänel J, Houshmand M, Kuhr A, Meisel P, Schwahn C, et al. Photodynamic therapy of persistent pockets in maintenance patients-a clinical study. Clin Oral Investig. 2010;14:637–44. doi: 10.1007/s00784-009-0347-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eick S, Tigan M, Sculean A. Effect of ozone on Periodontopathogenic species – An in vitro study. Clin Oral Investig. 2012;16:537–44. doi: 10.1007/s00784-011-0515-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huth KC, Jakob FM, Saugel B, Cappello C, Paschos E, Hollweck R, et al. Effect of ozone on oral cells compared with established antimicrobials. Eur J Oral Sci. 2006;114:435–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2006.00390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al Habashneh R, Alsalman W, Khader Y. Ozone as an adjunct to conventional nonsurgical therapy in chronic periodontitis: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J Periodontal Res. 2015;50:37–43. doi: 10.1111/jre.12177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayakumo S, Arakawa S, Mano Y, Izumi Y. Clinical and microbiological effects of ozone nano-bubble water irrigation as an adjunct to mechanical subgingival debridement in periodontitis patients in a randomized controlled trial. Clin Oral Investig. 2013;17:379–88. doi: 10.1007/s00784-012-0711-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carinci F, Palmieri A, Girardi A, Cura F, Lauritano D. Aquolab: Ozone-therapy is an efficient adjuvant in the treatment of chronic periodontitis: A case-control study. J Orofac Sci. 2015;7:27–32. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yılmaz S, Algan S, Gursoy H, Noyan U, Kuru BE, Kadir T. Evaluation of the clinical and antimicrobial effects of the Er:YAG laser or topical gaseous ozone as adjuncts to initial periodontal therapy. Photomed Laser Surg. 2013;31:293–8. doi: 10.1089/pho.2012.3379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Christodoulides N, Nikolidakis D, Chondros P, Becker J, Schwarz F, Rössler R, et al. Photodynamic therapy as an adjunct to non-surgical periodontal treatment: A randomized, controlled clinical trial. J Periodontol. 2008;79:1638–44. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.070652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yilmaz S, Kuru B, Kuru L, Noyan U, Argun D, Kadir T. Effect of gallium arsenide diode laser on human periodontal disease: A microbiological and clinical study. Lasers Surg Med. 2002;30:60–6. doi: 10.1002/lsm.10010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Oliveira RR, Schwartz-Filho HO, Novaes AB, Garlet GP, de Souza RF, Taba M, et al. Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy in the non-surgical treatment of aggressive periodontitis: Cytokine profile in gingival crevicular fluid, preliminary results. J Periodontol. 2009;80:98–105. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.070465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]