Background: At the start of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, many national health organizations emphasized nonpharmacologic interventions, such as quarantining or physical distancing. In the United Kingdom, strict self-isolation (“shielding”) was advised for those deemed to be clinically extremely vulnerable on the basis of the presence of selected medical conditions or at the discretion of their general practitioners.

Down syndrome features on neither the U.K. shielding list nor the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention list of groups at “increased risk.” However, it is associated with immune dysfunction, congenital heart disease, and pulmonary pathology and, given its prevalence, may be a relevant albeit unconfirmed risk factor for severe COVID-19 (1).

Objective: To evaluate Down syndrome as a risk factor for death from COVID-19 through a comprehensive analysis of individual-level data in a cohort study of 8.26 million adults (aged >19 years), as part of a wider COVID-19 risk prediction project commissioned by the U.K. government (2).

Methods and Findings: We used QResearch, a population-level primary care database that has collected data for more than 35 million persons in England since 1998 and is linked at the individual patient level to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) testing results from Public Health England, hospital episode statistics, and the Office of National Statistics death registry. Data extracted included age, sex, ethnicity, alcohol intake, smoking status, body mass index (BMI), a range of preexisting comorbid conditions, and concurrent medications. The primary outcome of interest was COVID-19 mortality in or out of the hospital, defined as confirmed or suspected COVID-19 on the death certificate or death within 28 days of a confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in the study period. The secondary outcome of interest was hospital admission related to COVID-19. The study period was 24 January 2020 (first confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in the United Kingdom) to 30 June 2020. We used Cox proportional hazards models to estimate adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% CIs, accounting for death from non–COVID-19 causes as a competing event by censoring all persons who did not have the outcome of interest at the study end date. We tested for interactions between Down syndrome and age, BMI, and sex.

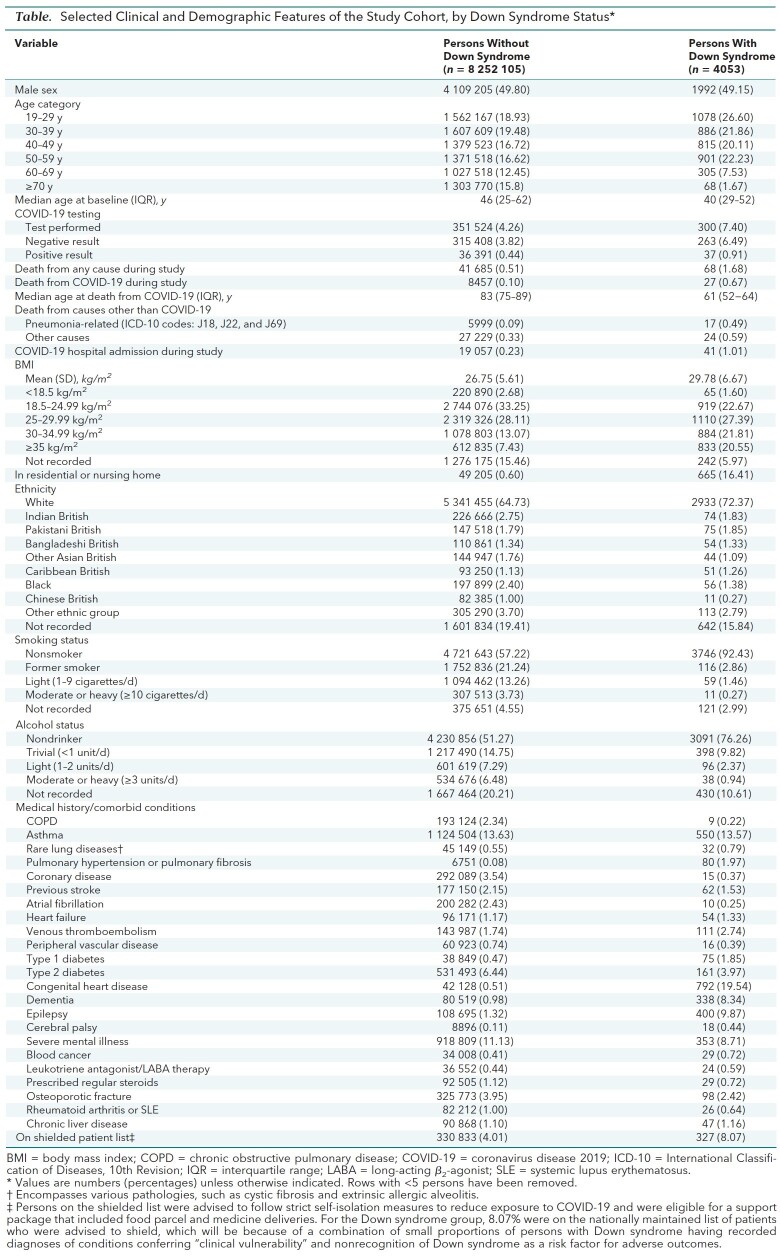

The Table shows selected demographic and clinical characteristics for the cohort. Of 8.26 million adults in the study cohort, 4053 had Down syndrome. Sixty-eight persons with Down syndrome died, 27 (39.7%) of COVID-19, 17 (25.0%) of pneumonia or pneumonitis, and 24 (35.3%) of other causes. Of the 8 252 105 persons without Down syndrome, 41 685 died, 8457 (20.3%) of COVID-19, 5999 (14.4%) of pneumonia or pneumonitis, and 27 229 (65.3%) of other causes.

Table. Selected Clinical and Demographic Features of the Study Cohort, by Down Syndrome Status*.

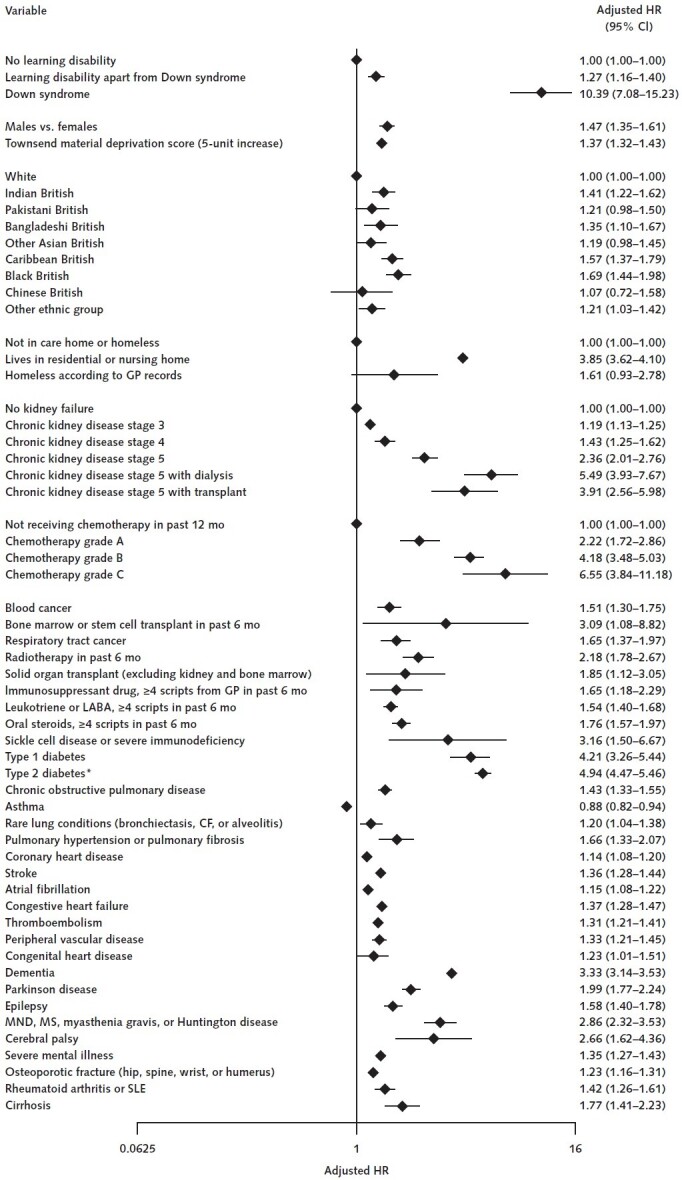

Adjusted for age and sex, the HR for COVID-19–related death in adults with versus without Down syndrome was 24.94 (95% CI, 17.08 to 36.44). After adjustment for age, sex, ethnicity, BMI, dementia diagnosis, care home residency, congenital heart disease, and a range of other comorbid conditions and treatments (Table), the HR for COVID-19–related death was 10.39 (CI, 7.08 to 15.23); for hospitalization, it was 4.94 (CI, 3.63 to 6.73) (Figure). There was no evidence of interactions between Down syndrome and age, sex, or BMI. The HR for death was not affected by further adjustment for smoking status and alcohol intake (HR, 10.12 [CI, 6.90 to 14.84]). For those with learning disabilities other than Down syndrome, the adjusted HR for COVID-19–related death was 1.27 (CI, 1.16 to 1.40).

Figure. Adjusted HR (95% CI) for the association between Down syndrome and death from COVID-19.

Adjusted for the variables shown, deprivation, fractional polynomial terms for body mass index (BMI), and age. The model includes fractional polynomial terms for age, BMI, and interaction terms between age terms and type 2 diabetes. We used the QResearch database, version 44. The study period was 24 January 2020 to 30 June 2020. CF = cystic fibrosis; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; GP = general practitioner; HR = hazard ratio; LABA = long-acting β2-agonist; MND = motor neurone disease; MS = multiple sclerosis; SLE = systemic lupus erythematosus.

* HR for type 2 diabetes reported at mean age.

Discussion: We estimated a 4-fold increased risk for COVID-19–related hospitalization and a 10-fold increased risk for COVID-19–related death in persons with Down syndrome, a group that is currently not strategically protected. This was after adjustment for cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases and care home residence, which our results suggest explained some but not all of the increased risk. These estimated adjusted associations do not have a direct causal interpretation because some adjusted variables may lie on causal pathways, but they can inform policy and motivate further investigation. Participation in day care programs or immunologic deficits could be implicated, for example. Down syndrome is the most common genetic cause of intellectual disability, with multiorgan manifestations (3). Predisposition to pneumonias and acute respiratory distress syndrome in children, airway anomalies, pulmonary hypoplasia, and inhibited pulmonary angiogenesis have been reported (4, 5).

We are unaware of the effects of Down syndrome on COVID-19 outcomes being reported elsewhere yet during this pandemic. Novel evidence that specific conditions may confer elevated risk should be used by public health organizations, policymakers, and health care workers to strategically protect vulnerable individuals.

Footnotes

This article was published at Annals.org on 21 October 2020

References

- 1.Espinosa JM. Down syndrome and COVID-19: a perfect storm? Cell Rep Med. 2020;1:100019. [PMID: 32501455] doi:10.1016/j.xcrm.2020.100019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Development of a COVID-19 risk prediction model. Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. 2020. Accessed at www.phc.ox.ac.uk/research/primary-care-epidemiology/covid-19-risk-tool on 23 June 2020.

- 3.Antonarakis SE, Skotko BG, Rafii MS, et al. Down syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6:9. [PMID: 32029743] doi:10.1038/s41572-019-0143-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Colvin KL, Yeager ME. What people with Down syndrome can teach us about cardiopulmonary disease. Eur Respir Rev. 2017;26. [PMID: 28223397] doi:10.1183/16000617.0098-2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Ram G, Chinen J. Infections and immunodeficiency in Down syndrome. Clin Exp Immunol. 2011;164:9-16. [PMID: 21352207] doi:10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04335.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]