Abstract

Objectives

The outcome of emergency medicine (EM) training is to produce physicians who can competently run an emergency department (ED) shift. However, there are few tools with supporting validity evidence specifically designed to assess multiple key competencies across an entire shift. The investigators developed and gathered validity evidence for a novel entrustment‐based tool to assess a resident’s ability to safely run an ED shift.

Methods

Through a nominal group technique, local and national stakeholders identified dimensions of performance that are reflective of a competent ED physician and are required to safely manage an ED shift. These were included as items in the Ottawa Emergency Department Shift Observation Tool (O‐EDShOT), and each item was scored using an entrustment‐based rating scale. The tool was implemented in 2018 at the University of Ottawa Department of Emergency Medicine, and quantitative data and qualitative feedback were collected over 6 months.

Results

A total of 1,141 forms were completed by 78 physicians for 45 residents. An analysis of variance demonstrated an effect of training level with statistically significant increases in mean O‐EDShOT scores with each subsequent postgraduate year (p < 0.001). Scores did not vary by ED treatment area. Residents rated as able to safely run the shift had significantly higher mean ± SD scores (4.8 ± 0.3) than those rated as not able (3.8 ± 0.6; p < 0.001). Faculty and residents reported that the tool was feasible to use and facilitated actionable feedback aimed at progression toward independent practice.

Conclusions

The O‐EDShOT successfully discriminated between trainees of different levels regardless of ED treatment area. Multiple sources of validity evidence support the O‐EDShOT as a tool to assess a resident’s ability to safely run an ED shift. It can serve as a stimulus for daily observation and feedback making it practical to use within an EM residency program.

The emergency department (ED) is a front‐line clinical microsystem in which immediate medical care and stabilization are provided to the acutely ill and injured. As a vital health care safety net and a major gateway to the hospital system, the ED and its unpredictable and often chaotic nature pose practice challenges that require unique skill sets. 1 Emergency medicine (EM) physicians work shifts of varying lengths in the ED. The ability to effectively run an ED shift (i.e., manage the various clinical, administrative, and educational responsibilities of the shift) is a defining attribute of any practicing emergency physician and represents a key outcome of EM specialty training. 2 , 3 With the widespread adoption of competency‐based medical education (CBME), the focus of assessment has shifted from using proxy measures of competence to measuring outcomes of training. 4 , 5 Therefore, if the pragmatic goal of EM training is ultimately to produce physicians capable of safely managing an ED shift, a method to assess a resident’s readiness to do so is needed.

To determine how a trainee is performing, he or she needs to be assessed while engaged in the complexities of real‐world practice. 6 Workplace‐based assessments (WBAs) align with the outcomes‐based nature of CBME by focusing on the top tier of Miller’s pyramid—what a trainee “does” in authentic clinical settings. 7 , 8 Daily encounter cards (DECs) have become a principle form of WBA used in the ED setting to assess the performance of trainees. 9 , 10 DECs facilitate the simultaneous assessment of multiple key competencies based on observation of performance during an entire shift. 9 , 10 DECs are typically completed at the end of each shift by the supervisor, therefore minimizing recall bias, while serving as a stimulus for frequent formative feedback and enabling multiple assessments of performance over time. 9 , 10 , 11 Despite their widespread use, evidence suggests that the quality of assessments being documented on DECs is poor. 12 , 13 A study by Bandiera and Lendrum 11 found that DECs were subject to leniency or range restriction effects wherein supervisors provided “inflated” or overly favorable assessments leading to indiscriminate ratings. Sherbino et al. 14 found that DEC items were not well understood by front‐line supervisors, resulting in poor reliability and questionable validity of the scores. While other assessments have been developed to assess performance during an ED shift, a systematic review of the literature demonstrates a paucity of validity evidence for most of these WBAs. 15 To that end, there is still a need for a tool with strong validity evidence that can be used to assess a trainee’s ability to safely run an ED shift.

A major threat to the validity of many existing WBAs is the lack of alignment between how supervisors cognitively construct judgments of the trainee and the way in which they are expected to document these judgments. 16 Recent work suggests that the poor psychometric performance of WBAs may not be due to disagreements about what has been observed, but instead be a consequence of differences in how raters interpret the questions and the scales used. 17 Many of the existing WBAs in EM apply rating scales anchored to a predetermined level of training (e.g., “below, meets, or above expectations”). However, these scales are subject to the rater’s expectation of performance for a particular level of training. Entrustability scales use the standard of competence or independent performance as the top end of the rating scale anchors. 18 The specific wording of the descriptive anchors and how they are referred to in the literature vary (e.g., entrustability, entrustment, and independence anchors). However, they are conceptually similar in that they are behaviorally anchored ordinal scales based on progression of competence that reflect increasing levels of independence. 18 These construct‐aligned scales appear to improve the reliability of assessments. 17 , 19 , 20 The Ottawa Surgical Competency Operating Room Evaluation (O‐SCORE) is a WBA tool that uses a particular set of entrustment anchors for its rating scale. 21 , 22 Given the strong psychometric properties of the O‐SCORE, these anchors have subsequently been used for two different WBA tools, the Ottawa Clinic Assessment Tool (OCAT) and the Ontario Bronchoscopy Assessment Tool (OBAT), which have similarly demonstrated strong psychometric properties. 23 , 24 , 25

The ED shift is the unit of work of an emergency physician. Accordingly, a key outcome of EM training is to produce graduates who can safely manage an ED shift. However, a tool with strong validity evidence to assess this outcome is lacking. The purpose of this study is to develop a WBA tool that incorporates the O‐SCORE entrustment anchors to assess an EM resident’s ability to safely manage an ED shift and to gather validity evidence to support its use.

Methods

Study Design and Ethics

This study consisted of three phases: 1) tool development, 2) data collection and psychometric analysis, and 3) tool refinement. Modern validity theory was used as a framework to guide the development of this tool. 26 In this framework, evidence from a number of sources is collected to help interpret the results of an assessment tool. Data from Phase I provided content‐related evidence. Data from Phase II provided evidence related to the internal structure and relationship to other variables, and data from Phase III provided evidence related to both response processes and consequences. Ethics approval was obtained for this study from the Ottawa Health Science Network Research Ethics Board (Protocol ID 20170417).

Phase I: Tool Development

Participants

Stakeholders were identified using purposeful sampling with the aim of identifying a range of senior and junior emergency physicians and residents, as well as clinician educators 27 and clinician teachers from the Department of Emergency Medicine at the University of Ottawa. Thirteen faculty and 10 residents participated in one of two consensus groups, consisting of 11 and 12 participants, respectively.

Procedures

Using a nominal group technique, 28 the goal of each consensus group was to generate a list of abilities required to safely run an ED shift. A nominal group technique was chosen because it facilitates generation of a large number of ideas and allows for potential discussion and debate. 28 The consensus group was facilitated by an experienced researcher (ND), and a second researcher (WJC) took notes. The facilitator began the consensus group by asking participants: “What abilities are necessary to run an emergency department shift?” Participants were given 10 minutes to individually generate items and write them down. The facilitator then invited participants share their items in a round‐robin session and each unique response was recorded and displayed. Items were added to the list until no new ideas were generated. Participants were then given examples of commonly used ED WBA tools and asked to comment on and discuss the form structure and items included. They were then given an opportunity to contribute additional items. Participants then voted anonymously on whether to keep each item on the list. Items that did not reach 80% consensus were further discussed. Items were only kept if there was 80% consensus in the group after discussion. Three rounds of discussion were required in both groups to reach consensus.

An e‐mail survey of intentionally sampled EM clinician educators on the national specialty committee was distributed to gather additional items and add geographical generalizability. This national group was given the combined list of items generated from the two local consensus groups and asked to add any items they deemed necessary. Responses generated from the e‐mail survey that were not already captured during the consensus groups were added to the item list. This list was reviewed by the research team and items representing similar constructs were combined. All items on this final list were included in the new tool.

The initial version of the tool included 12 items. The 5‐point anchored O‐SCORE rating scale was used to score each item. Minor modifications were made to the descriptions of each anchor to ensure they applied to the ED context. 21 A “not applicable” option was included for six items that are not always clinically applicable on every shift. Two additional questions asking supervisors to indicate (yes/no) if there were any concerns about the resident’s self‐awareness and professionalism were also included. A global assessment asking supervisors to judge (yes/no) whether the resident could have safely managed the shift independently was included along with a mandatory narrative section asking supervisors to document at least one aspect of the performance that was done well and at least one specific suggestion for improvement.

Faculty and residents were provided an orientation and training on how to use the new tool at two department meetings and one grand rounds. A 4‐week pilot was conducted in the Department of Emergency Medicine at the University of Ottawa, and feedback was collected on the design and clarity of the tool. Minor revisions were made to the format and wording of items based on this feedback. The tool was named the Ottawa Emergency Department Shift Observation Tool (O‐EDShOT). The initial version of the O‐EDShOT is available in Data Supplement S1 (available as supporting information in the online version of this paper, which is available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/aet2.10419/full).

Phase II: Data Collection and Psychometric Analysis

Setting and Data Collection

Data collection was conducted at two urban, tertiary care, academic EDs of The Ottawa Hospital. Each ED consists of three treatment areas: urgent care (low acuity), observation (moderate acuity), and resuscitation (high acuity). During a shift, residents worked in one of the three ED treatment areas with a single supervising faculty. During a 6‐month period (July 2018– December 2018), the O‐EDShOT replaced the previous DEC as the mandatory end‐of‐shift assessment form. The O‐EDShOT was completed for each resident at the end of every shift by their supervising faculty.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS Statistics version 24 and G_String software. 29 Descriptive statistics and interitem correlations were calculated. Mean O‐EDShOT scores were calculated for each form by averaging the scores for items that had been rated.

A generalizability analysis was used to determine the reliability of the scores. This model used mean O‐EDShOT score as the dependent measure, and consisted of a factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA) with training year (y), residents within year (r:y), and forms (f:r:y) as factors. In this model, “r:y” was the object of measurement. The mean O‐EDShOT score was used for this analysis because including items as an explicit factor in the analysis would have led to a considerable amount of missing data as some items were not rated on every shift. The variance components from this analysis were used to generate a reliability coefficient. A dependability analysis was conducted to determine the number of forms per resident needed to obtain a reliability of 0.70 and 0.80, respectively. A subsequent analysis was conducted to examine the internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) of the six mandatory O‐EDShOT items.

The effect of training level was determined by conducting an ANOVA with postgraduate year (PGY‐1 to ‐5) as the between‐subjects variable and mean O‐EDShOT score as the dependent variable. A second ANOVA was conducted with ED treatment area (urgent care, observation, resuscitation) as the between‐subjects variable to examine whether O‐EDShOT scores varied by acuity zone of the ED. To examine the effect of supervisors’ judgments of a resident’s ability to safely manage the ED shift independently, a 5 × 2 factorial ANOVA was conducted with safety to independently run the shift (yes, no) and training level (PGY‐1 to ‐5) as the between‐subject variables and mean O‐EDShOT score as the dependent variable. Bonferroni post hoc tests were conducted to analyze differences for the above ANOVAs.

Phase III: Tool Refinement

Phase III was designed to collect evidence related to both response processes and consequences. An e‐mail survey was distributed to faculty and residents within the Department of Emergency Medicine to gather feedback on the clarity, utility, and feasibility of the O‐EDShOT. Additionally, two 1‐hour feedback sessions were held in February 2019. During these sessions, items demonstrating high interitem correlations were discussed to determine if they should remain. Based on this feedback the tool was revised to the final version of the O‐EDShOT.

Results

A total of 1,141 O‐EDShOTs were completed over 6 months by 79 supervising faculty for 46 residents, with an average of 20 forms per resident (range = 10 to 54).

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for the initial 12 items rated on the 5‐point O‐SCORE scale. Scores for each item ranged from 1 to 5. Items 5 and 6 and 9 through 12 were not rated on every shift as they were not always clinically applicable. Of the 1,141 forms collected, very few noted concerns about resident self‐awareness (n = 10, 0.9%) or professionalism (n = 4, 0.4%). Interitem correlations ranged from r = 0.48 to r = 0.97. High correlations (r > 0.9) were observed between items 5 and 6, 7 and 8, 10 and 11, and 11 and 12.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of the Initial 12 O‐EDShOT Items

| Rating | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | SD |

| 1 | 1141 | 1 | 5 | 4.23 | 0.80 |

| 2 | 1141 | 1 | 5 | 3.89 | 0.86 |

| 3 | 1141 | 1 | 5 | 4.06 | 0.88 |

| 4 | 1141 | 1 | 5 | 4.24 | 0.79 |

| 5 | 740 | 1 | 5 | 4.15 | 0.99 |

| 6 | 886 | 1 | 5 | 3.76 | 1.04 |

| 7 | 1141 | 1 | 5 | 4.46 | 0.72 |

| 8 | 1141 | 1 | 5 | 4.45 | 0.73 |

| 9 | 588 | 1 | 5 | 4.26 | 1.00 |

| 10 | 289 | 1 | 5 | 4.02 | 1.17 |

| 11 | 186 | 1 | 5 | 4.06 | 1.30 |

| 12 | 129 | 1 | 5 | 3.97 | 1.29 |

O‐EDShOT = Ottawa Emergency Department Shift Observation Tool.

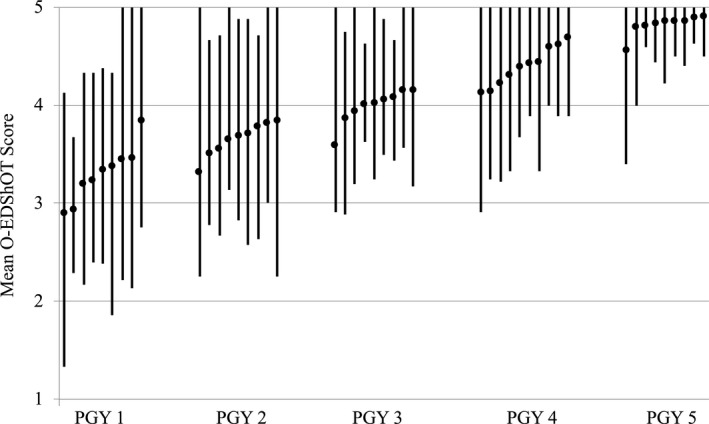

Generalizability Analysis

Table 2 displays the variance components derived from the generalizability analysis. Training level accounted for the majority of variance (58%), indicating differences in scores between each postgraduate year. The r:y facet accounted for only 5% of the variance, indicating that within a training level, residents received similar scores. However, the f:r:y facet, which accounted for a large proportion of the variance (38%), suggests that within a resident there was variation in scores across forms. This variation was confirmed by examining the range of mean scores for each resident (Figure 1). For a given resident, there was a range in mean scores and an overlap in means with high scores in one training level overlapping with low scores in the level above. The reliability of the O‐EDShOT was 0.74 with an average of 20 forms per resident. Thirteen forms per resident would be required to achieve a reliability of 0.70 and 33 forms for a reliability of 0.80. The internal consistency of the six mandatory items was 0.93.

Table 2.

Generalizability Analysis

| Facet | Variance | Variance (%) | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| y | 0.33 | 58 | Variance attributable to differences between training levels |

| r:y | 0.03 | 5 | Variance attributable to difference between residents within a training level |

| f:r:y | 0.57 | 38 | Variance attributable to differences between forms within a resident plus random error |

y = training year; r = resident; f = form.

Figure 1.

Range of mean O‐EDShOT scores for each resident by postgraduate training year. O‐EDShOT = Ottawa Emergency Department Shift Observation Tool.

Effect of Training Level

The mean O‐EDShOT scores for each training level are displayed in Table 3. There was a significant main effect of training level (F(4,1136) = 310; p < 0.001, partial eta squared = 0.52). A subsequent pairwise comparison demonstrated that there was a statistically significant increase in mean O‐EDShOT scores with each subsequent postgraduate year (p < 0.001), indicating that the O‐EDShOT was able to discriminate performance between training levels.

Table 3.

Mean O‐EDShOT Score by Training Level

| Training Year | Mean | N | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| PGY‐1 | 3.24 | 120 | 0.75 |

| PGY‐2 | 3.66 | 214 | 0.52 |

| PGY‐3 | 3.97 | 120 | 0.48 |

| PGY‐4 | 4.38 | 266 | 0.42 |

| PGY‐5 | 4.83 | 158 | 0.24 |

| Total | 4.07 | 878 | 0.71 |

O‐EDShOT = Ottawa Emergency Department Shift Observation Tool.

Effect of ED Treatment Area

Mean ± SD O‐EDShOT scores for urgent care (4.1 ± 0.7), observation (4.0 ± 0.7), and resuscitation (4.0 ± 0.7) differed (F(2,863) = 13; p < 0.001); however, the magnitude of the absolute differences was small (partial eta squared = 0.03). A subsequent pairwise comparison demonstrated no significant differences in mean scores between ED treatment areas.

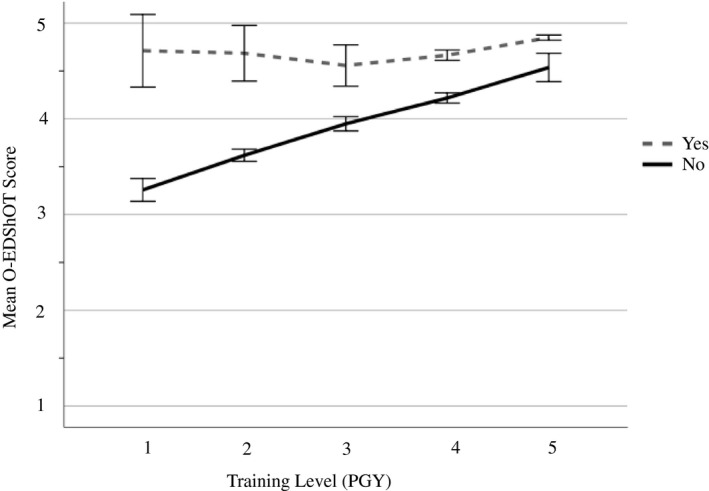

Safety to Independently Manage a Shift

Residents rated as able to safely run the ED shift independently had statistically significant higher mean ± SD O‐EDShOT scores (4.8 ± 0.3) compared to those rated as not able (3.8 ± 0.6; p < 0.001). A greater proportion of senior residents were judged as able to safely manage the ED shift compared to junior residents (Data Supplement S1, Table S1). The correlation between the response on this global judgment and the mean O‐EDShOT score was r = 0.65 (p < 0.001), indicating a moderately high relationship. There was a significant interaction between training level and ability to safely manage the shift independently (F(4,1131) = 11; p < 0.001; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison of mean O‐EDShOT scores (with 95% CIs) for each postgraduate year by ability to safely run the ED shift independently (yes/no). O‐EDShOT = Ottawa Emergency Department Shift Observation Tool.

Tool Refinement

Qualitative data from the survey and feedback sessions indicated that faculty and residents found the O‐EDShOT feasible to use and required less time to complete compared to the previous DEC. Both groups reported that items were easily understood and generated useful formative feedback.

Faculty reported that the O‐SCORE rating scale was practical and less subjective than the normative scale used on the previous DEC. Residents explained that for each item, the scale served as a stimulus to improve performance because it was based on progression toward independence—a concrete goal. Both residents and faculty also commented that the scale better reflected the realities of clinical supervision, and therefore residents were more accepting of lower scores.

Residents and faculty agreed that the item: “Follow‐up on test results on discharged patients” was most often performed outside of the shift and was infrequently observed. Based on this feedback and the high interitem correlation, the item was removed leaving a total of 11 items on the final version of the O‐EDShOT. Based on additional feedback, descriptors for the “not applicable” options were added to three items to improve clarity. The final version of the O‐EDShOT is available as supplemental material accompanying the online article (available as supporting information in the online version of this paper, which is available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/aet2.10419/full).

Discussion

An ED shift is the unit of work of any emergency physician. Accordingly, a key outcome of EM training is to produce graduates who possess the spectrum of competencies necessary to run an ED shift unsupervised. The O‐EDShOT was developed to measure multiple competencies across an entire shift, not just a single patient encounter. Multiple sources of validity evidence support the use of the tool for assessing a resident’s ability to safely manage an ED shift. Our results demonstrate that the O‐EDShOT was able to differentiate between residents of varying training levels and scores did not vary based on ED treatment area, indicating that the O‐EDShOT can be used to assess a resident’s ability to run an ED shift regardless of which acuity area they are assigned. Furthermore, front‐line faculty and residents report that the O‐EDShOT is feasible and helpful for stimulating feedback aimed at progression toward independent practice.

A challenge with many WBAs, including DECs, is range restriction, which limit the utility of the assessment. 11 , 30 , 31 Our results, in contrast, demonstrate that raters were willing to use the entire rating scale for each item, and a range of mean O‐EDShOT scores within a resident was observed. These findings are consistent with recent WBA literature demonstrating that assessors provide more discriminating ratings and make greater use of the entire scale when tools incorporate entrustment‐type anchors compared to traditional anchors. 17 , 32 , 33 In our focus groups, faculty and residents indicated that they were more comfortable providing and receiving lower ratings because the behavioral anchors of the O‐SCORE scale more accurately represented the resident’s actual clinical performance based on the degree of supervision required. Similar findings have been reported in studies of other WBA tools that have incorporated the O‐SCORE scale. 21 , 23 , 24 Faculty and residents in our study also reported that the scale was more pragmatic and objective than the normative scale previously used (e.g., below, meets, exceeds expectation), which required the assessor to translate judgments of the trainee’s performance into abstract anchors based on poorly understood expectations for the resident’s level of training. 18 , 21 These notions are supported by literature, which suggests that entrustability scales are construct‐aligned and reflect the priorities of the clinician‐assessor. 17 , 18 , 19 Additionally, ratings on entrustability scales are perceived by trainees to be more transparent and justified because the language of entrustment anchors are framed around progression toward independent practice, making the link between clinical assessment and developing ability in the workplace more explicit. 32

The statistically significant correlation observed between items on the O‐EDShOT and the yes/no judgment of ability to safely run the shift suggests the scores are measuring the construct we intended. This moderately high correlation also suggests that the tool could be shortened to a single item asking: “Was the resident able to run the shift unsupervised?” as has been demonstrated with other WBA tools. 34 , 35 While this question encompasses a key outcome of training, keeping the formative goals of the O‐EDShOT in mind, we believe that the responses to all items remain a valuable source for feedback and discussion. 36 The items on the O‐EDShOT highlight to the resident the abilities required to run an ED shift, as determined by a national group of practicing EM physicians and educators. The items also aid assessors in identifying areas for improvement, and residents in our study indicated that item ratings served as a springboard for specific and actionable formative feedback targeting progression toward the concrete goal of independent practice. Congruent with these results, Dudek et al. 32 found that alignment of the language of entrustment anchors with training outcomes promoted more useful feedback conversations between assessor and trainee. Furthermore, Dolan and colleagues 33 noted an increase in documented feedback once an entrustment language was adopted. Although beyond the scope of this study, future inquiry should build on this literature to examine whether adopting an entrustability scale results in improvements to the quality of documented feedback.

As with other daily assessments, the O‐EDShOT is primarily intended to be a formative assessment tool. As such, a reliability of 0.70 is likely appropriate. 37 Thirteen forms per person, the number needed to achieve this reliability, can be easily collected during a single 4‐week rotation. In addition, faculty felt the O‐EDShOT was feasible and appropriate for daily observation and feedback making it a practical tool to use within the context of a residency program. However, one can also consider utilizing daily assessment tools in a more summative manner within the larger program of assessment. Given that the O‐EDShOT captures the essential skills of an EM physician, it could be used to assess specific entrustable professional activities in the transition to practice stage of training that relate to managing the ED and inform decisions made by the clinical competency committee about a resident’s readiness for independent practice. For these higher‐stakes decisions, 33 forms (equivalent to two to three rotations of data) would be required for a reliability of 0.80. 37 This would be particularly applicable for residents nearing the end of their training for whom decisions about readiness for independent practice need to be made.

In this study we did not provide additional rater training beyond introducing the tool to faculty and residents during department meetings and grand rounds. For the majority of faculty this appears to be adequate as evidenced by the strong psychometric performance of the tool. However, there is evidence that not all faculty are using the tool as intended. Faculty raters judged first‐year residents as able to safely run the ED shift unsupervised on a small proportion of forms. This finding is surprising because one would not expect a junior trainee to be able to independently manage the complex clinical and administrative responsibilities of a shift until their more senior years. It is possible that the case mix of patients seen on those shifts was unusually straightforward or that the outlying forms represent of a few very high‐performing junior residents. However, closer examination of the data reveals that within a resident, these were isolated occurrences and not consistent with the rest of the resident’s O‐EDShOT data. Instead, these forms were completed by the same four faculty, and item ratings demonstrate range restriction to the right of the scale. This suggests that the outlying data may be more likely due to rater idiosyncrasies than case‐mix or resident factors and that these specific faculty require additional targeted rater training to improve assessment quality. With implementation of the O‐EDShOT, idiosyncratic scores should be monitored to help identify focused individual faculty development needs.

Limitations

Assessors in the study were not blinded to the resident’s level of training. The literature on rater cognition suggests that unblinded raters may provide biased scores of performance based on expectations for level of training or relative to exemplars. 38 Blinding assessors would have been logistically challenging as it would have required external clinician‐assessors to observe and supervise our residents during entire shifts. To demonstrate that residents were not scored according to year of training by our unblinded raters, we would ideally have demonstrated in our generalizability analysis that the influence of forms within a resident contributed to a large proportion of the variance in O‐EDShOT scores. However, every O‐EDShOT item was not observed and rated on each shift, reflecting the realities of working in the ED environment. As a result, O‐EDShOT items could not be included as a factor in the generalizability analysis, which makes it difficult to determine how much of the error term can be attributed to variation in forms within a resident. However, taking a pragmatic approach, we observed that any given resident received a range of mean O‐EDShOT scores and that the range of mean scores between training levels overlapped, suggesting that residents were not scored according to year of training, even though the assessors were unblinded.

The other limitation is that we have only provided validity evidence for use of the O‐EDShOT at a single institution comprising two urban academic EDs. It is certainly possible that these results may not generalize to other contexts that have different assessment cultures. Future work will study the use of the O‐EDShOT at different institutions to address this concern.

Conclusions

A key outcome of emergency medicine training is to produce physicians who can competently run an ED shift without supervision. To that end, a method to assess a resident’s readiness to do so is needed. The results of this study provide multiple sources of validity evidence for the use of the O‐EDShOT, a novel WBA tool designed to measure a resident’s ability to safely manage an ED shift. Both faculty and residents report that the tool is feasible and practical to use and that it facilitates actionable feedback aimed at progression toward independent practice. Furthermore, residency training programs may use O‐EDShOT data collected over several rotations to inform decisions made by the clinical competency committee about which trainees are ready for unsupervised practice.

Supporting information

Data Supplement S1. Supplemental material.

AEM Education and Training 2020;4:359–368

Presented at the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians Conference, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, May 2019 (Top Education Innovation Award); and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Annual Meeting, Las Vegas, NV, May 2019.

Supported by the Wooster Family Grant in Medical Education, Canadian Association for Medical Education; and the Health Professions Education Research Grant, University of Ottawa Department of Innovation in Medical Education.

The authors have no potential conflicts to disclose.

Author contributions: WJC—study concept and design, acquisition of the data, analysis and interpretation of the data, drafting the manuscript, obtaining funding; TJW—analysis and interpretation of the data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, statistical expertise; WG—study concept and design, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; SD—critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; obtained funding; ND—study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of the data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, study supervision.

References

- 1. Moskop JC, Geiderman JM, Marshall KD, et al. Another look at the persistent moral problem of emergency department crowding. Ann Emerg Med 2019;74:357–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Definition of Emergency Medicine. Irving, TX: American College of Emergency Physicians , 2015.

- 3. Position Statement on Emergency Medicine Definitions. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians , 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Carraccio CL, Englander R. From Flexner to competencies: reflections on a decade and the journey ahead. Acad Med 2013;88:1067–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Carraccio C, Wolfsthal SD, Englander R, Ferentz K, Martin C. Shifting paradigms: from Flexner to competencies. Acad Med 2002;77:361–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kogan JR, Holmboe E. Realizing the promise and importance of performance‐based assessment. Teach Learn Med 2014;2013:S68–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Norcini J. Work based assessment. Br Med J 2003;326:753–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Frank JR, Snell LS, Cate OT, et al. Competency‐based medical education: theory to practice. Med Teach 2010;32:638–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Frank JR, Lee C, Bandiera G. Encounter Cards In: Bandiera G, Sherbino J, Frank JR, editors. The CanMEDS Assessment Tool Handbook. An Introductory Guide to Assessment Methods for the CanMEDS Competencies. Ottawa, ON: The Royal College of Physicians & Surgeons of Canada, 2006. p. 39–42. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sherbino J, Bandiera G, Frank J. Assessing competence in emergency medicine trainees: an overview of effective methodologies. Can J Emerg Med 2008;10:365–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bandiera G, Lendrum D. Daily encounter cards facilitate competency‐based feedback while leniency bias persists. Can J Emerg Med 2008;10:44–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cheung WJ, Dudek N, Wood TJ, Frank JR. Daily encounter cards ‐ evaluating the quality of documented assessments. J Grad Med Educ 2016;8:601–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cheung WJ, Dudek NL, Wood TJ, Frank JR. Supervisor–trainee continuity and the quality of work‐based assessments. Med Educ 2017;51:1260–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sherbino J, Kulasegaram K, Worster A, Norman GR. The reliability of encounter cards to assess the CanMEDS roles. Adv Heal Sci Educ 2013;18:987–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kogan JR, Holmboe ES, Hauer KE. Tools for direct observation and assessment of clinical skills of medical trainees: a systematic review. JAMA 2009;302:1316–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Regehr G, Eva K, Ginsburg S, Halwani Y, Sidhu R. Assessment in postgraduate medical education: trends and issues in assessment in the workplace. Members of the FMEC PG Consortium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Crossley J, Johnson G, Booth J, Wade W. Good questions, good answers: construct alignment improves the performance of workplace‐based assessment scales. Med Educ 2011;45:560–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rekman J, Gofton W, Dudek N, Gofton T, Hamstra SJ. Entrustability scales: outlining their usefulness for competency‐based clinical assessment. Acad Med 2015;91:186–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Crossley J, Jolly B. Making sense of work‐based assessment: ask the right questions, in the right way, about the right things, of the right people. Med Educ 2012;46:28–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Weller JM, Jones A, Merry AF, Jolly B, Saunders D. Investigation of trainee and specialist reactions to the mini‐Clinical Evaluation Exercise in anaesthesia: implications for implementation. Br J Anaesth 2009;103:524–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gofton WT, Dudek NL, Wood TJ, Balaa F, Hamstra SJ. The Ottawa Surgical Competency Operating Room Evaluation (O‐SCORE): a tool to assess surgical competence. Acad Med 2012;87:1401–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. MacEwan MJ, Dudek NL, Wood TJ, Gofton WT. Continued validation of the O‐SCORE (Ottawa Surgical Competency Operating Room Evaluation): use in the simulated environment. Teach Learn Med 2016;28:72–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Voduc N, Dudek N, Parker CM, Sharma KB, Wood TJ. Development and validation of a bronchoscopy competence assessment tool in a clinical setting. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2016;13:495–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rekman J, Hamstra SJ, Dudek N, Wood T, Seabrook C, Gofton W. A new instrument for assessing resident competence in surgical clinic: the Ottawa Clinic Assessment Tool. J Surg Educ 2016;73:575–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Halman S, Rekman J, Wood T, Baird A, Gofton W, Dudek N. Avoid reinventing the wheel: implementation of the Ottawa Clinic Assessment Tool (OCAT) in internal medicine. BMC Med Educ 2018;18:218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, National Council on Measurement in Education . Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing. Washington, DC: AERA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sherbino J, Frank JR, Snell L. Defining the key roles and competencies of the clinician‐educator of the 21st century: a national mixed‐methods study. Acad Med 2014;89:783–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Humphrey‐Murto S, Varpio L, Gonsalves C, Wood TJ. Using consensus group methods such as Delphi and nominal group in medical education research. Med Teach 2017;39:14–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. McMaster Education Research, Innovation & Theory . G_String. c2017. Available at: http://fhsperd.mcmaster.ca/g_string/index.html. Accessed January 16, 2017.

- 30. Streiner D, Norman G. Health Measurement Scales. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Govaerts MJ, Schuwirth LW, Van der Vleuten CP, Muijtjens AM. Workplace‐based assessment: effects of rater expertise. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2011;16:151–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dudek N, Gofton W, Rekman J, McDougall A. Faculty and resident perspectives on using entrustment anchors for workplace‐based assessment. J Grad Med Educ 2019;11:287–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dolan BM, O’Brien CL, Green MM. Including entrustment language in an assessment form may improve constructive feedback for student clinical skills. Med Sci Educ 2017;27:461–4. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Saliken D, Dudek N, Wood TJ, MacEwan M, Gofton WT. Comparison of the Ottawa Surgical Competency Operating Room Evaluation (O‐SCORE) to a single‐item performance score. Teach Learn Med 2019;31:146–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Williams RG, Verhulst S, Mellinger JD, Dunnington GL. Is a single‐item operative performance rating sufficient? J Surg Educ 2015;72:e212–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dudek NL, Marks MB, Wood TJ, Lee A. Assessing the quality of supervisors’ completed clinical evaluation reports. Med Educ 2008;42:816–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Downing SM. Reliability: on the reproducibility of assessment data. Med Educ 2004;38:1006–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gauthier G, St‐Onge C, Tavares W. Rater cognition: review and integration of research findings. Med Educ 2016;50:511–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Supplement S1. Supplemental material.