Abstract

Background

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a neglected chronic inflammatory disease with long delay in diagnosis. Besides pain, purulent discharge, and destruction of skin architecture, HS patients experience metabolic, musculoskeletal, and psychological disorders.

Objectives

To determine the delay in HS diagnosis and its consequences for patients and the healthcare system.

Methods

This was a prospective, multicenter, epidemiologic, non-interventional cross-sectional trial carried out in Germany and based on self-reported questionnaires and medical examinations performed by dermatologists. In total, data of 394 adult HS patients were evaluated.

Results

The average duration from manifestation of first symptoms until HS diagnosis was 10.0 ± 9.6 (mean ± SD) years. During this time, HS patients consulted on average more than 3 different physicians − most frequently general practitioners, dermatologists, surgeons, gynecologists − and faced more than 3 misdiagnoses. Diagnosis delay was longer in younger and non-smoking patients. In most cases, HS was correctly diagnosed by dermatologists. The longer the delay of diagnosis, the greater the disease severity at diagnosis. Delayed HS diagnosis was also associated with an increased number of surgically treated sites, concomitant diseases, and days of work missed.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates an enormous delay in the diagnosis of HS, which results in more severe disease. It also shows for the first time that a delay in diagnosis of a chronic inflammatory disease leads to a higher number of concomitant systemic disorders. In addition to the impaired health status, delayed diagnosis of HS was associated with impairment of the professional life of affected people.

Keywords: Acne inversa, Hidradenitis suppurativa, Comorbidity, Diagnosis, Healthcare system

Introduction

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS; also designated as acne inversa) is a debilitating chronic inflammatory disease that affects the intertriginous skin, especially at axillary, inguinal, and perianal sites [1]. The estimated prevalence of HS is about 1% and HS skin lesions usually appear after puberty, thus mainly burdening the working population [2]. Approximately one third of patients are genetically predisposed [1]. Moreover, lifestyle factors like smoking and obesity play a crucial role in the clinical course of HS [3, 4, 5].

HS starts with the formation of single painful inflamed nodules or abscesses, defined as Hurley stage I. Without adequate therapy, the abscesses may recur and build fistulae that discharge malodorous purulent secretion (Hurley stage II). Finally, inflammation leads to the destruction of skin architecture, visible as a diffuse involvement of large areas with multiple abscesses, interconnected fistulae, and stiff, undermined or hypertrophic scars (Hurley stage III). Pain is the symptom that most strongly affects the everyday life of patients with HS [6]. Furthermore, odorous purulent discharge and aesthetic alterations profoundly impair patients' quality of life and scarring with formation of contractures causes limitation in mobility [1]. Therefore, untreated HS leads to embarrassment, social isolation, low self-esteem, and sexual life impairment [7, 8, 9]. It affects not only interpersonal relationships but also education and professional activity, producing a strongly disadvantaged population also at the socioeconomic level [7, 10]. Importantly, a high proportion of HS patients experience metabolic and endocrinologic disorders, including hypertriglyceridemia and hyperglycemia [11, 12]. As a consequence of cardiovascular events, such as myocardial infarction or stroke, the life expectancy of patients with HS is significantly reduced [13]. Additionally, HS patients frequently experience spondyloarthritis [14, 15].

Although the exact pathogenetic mechanisms are not yet understood, a relative deficiency of antibacterial proteins, bacterial propagation, and local uncontrolled immune activation have been postulated [16]. In fact, HS lesions contain elevated levels of numerous pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-1β, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IL-17, IL-36, and interferon γ [16, 17, 18, 19, 20]. These pro-inflammatory cytokines might induce chemokines leading to immune cell infiltration into the skin and purulent discharge as well as enzymes leading to extracellular matrix degradation and fistulae formation [20, 21, 22]. Locally produced IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-17 reach the bloodstream and might play a substantial role in systemic inflammatory comorbidities [23, 24, 25]. Therefore, early diagnosis of HS is of major importance for a prompt lifestyle change and the initiation of proper therapy limiting the inflammation and propagation of skin destruction and systemic comorbidities. However, worldwide more than 7 years seem to pass between the appearance of the first HS symptoms and correct diagnosis, as recently reported [26]. Furthermore, this data was almost exclusively gathered from HS specialized clinics suggesting that the real-world situation may appear even worse. In this paper, we aimed to determine the length of delay in diagnosis and its impact on the patients' life and the healthcare system, based on data collected from a wide spectrum of dermatological settings.

Patients and Methods

A prospective, epidemiologic, non-interventional, cross-sectional trial (PIRANHA) with HS patients was conducted in 64 German sites. All patients that fulfilled the inclusion criteria (see online suppl. material, www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000508787) and agreed on the trial were considered for participation. For data collection, supervised paper-based self-reported questionnaires and documented examination by dermatologists were used.

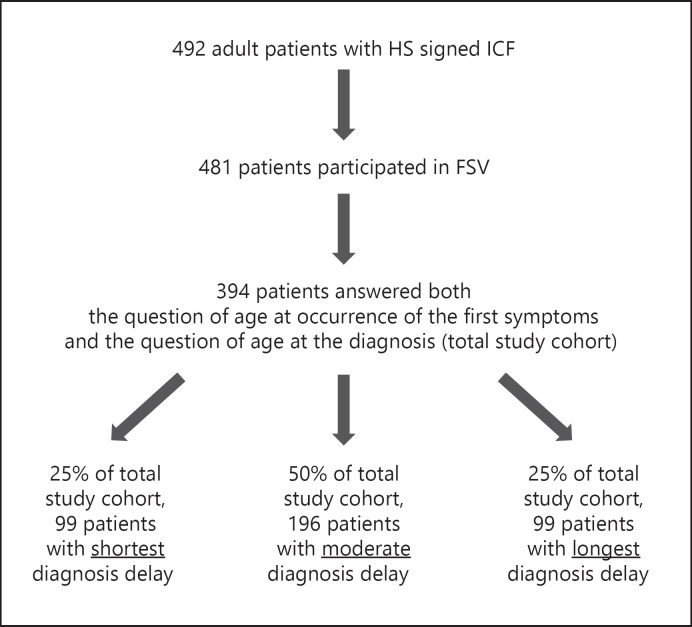

For further details, see Figure 1 and the online supplementary material.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of Patients and Methods demonstrating patient participation in this study. HS, hidradenitis suppurativa; ICF, informed consent form; FSV, first study visit.

Results

Since the correct diagnosis is the first requirement for adequate therapy, we determined the time between occurrence of first HS symptoms and HS diagnosis. Respective data were available from 394 participants (total study cohort) of the PIRANHA study (Fig. 1). The analyzed population comprised HS patients cared for by physicians in private practice, local hospitals, and university clinics, which may adequately represent the entire spectrum of patients with HS in Germany. Occurrence of first symptoms, as reported by the patients, was at an average age (mean ± SD) of 24.6 ± 10.5 years (Table 1). Notably, the mean age at diagnosis was 34.6 ± 11.2 years (Table 1), making the average duration between HS disease manifestation and diagnosis 10.0 ± 9.6 years (Fig. 2a). The mean age of the study population at inclusion was 39.2 ± 11.4 years (Table 1), indicating an average disease duration of 14.6 ± 10.4 years.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study cohort (n = 394)

| Age, years | |

| Mean ± SD | 39.2±11.4 |

| Range | 18.0–73.0 |

| Female, % | 53.3 |

| Male, % | 46.7 |

| BMI | |

| Mean ± SD | 31.2±7.0 |

| Range | 18.1–60.9 |

| Smoker, % | 60.3 |

| Ex-smoker, % | 24.4 |

| Never-smoker, % | 15.3 |

| Hurley stage | |

| Mean ± SD | 2.05±0.72 |

| Range | 1–3 |

| Age at first symptoms, years | |

| Mean ± SD | 24.6±10.5 |

| Range | 1.0–73.0 |

| Age at diagnosis, years | |

| Mean ± SD | 34.6±11.2 |

| Range | 5.2–72.7 |

| Disease duration, years | |

| Mean ± SD | 14.6±10.4 |

| Range | 0.0–46.0 |

BMI, body mass index.

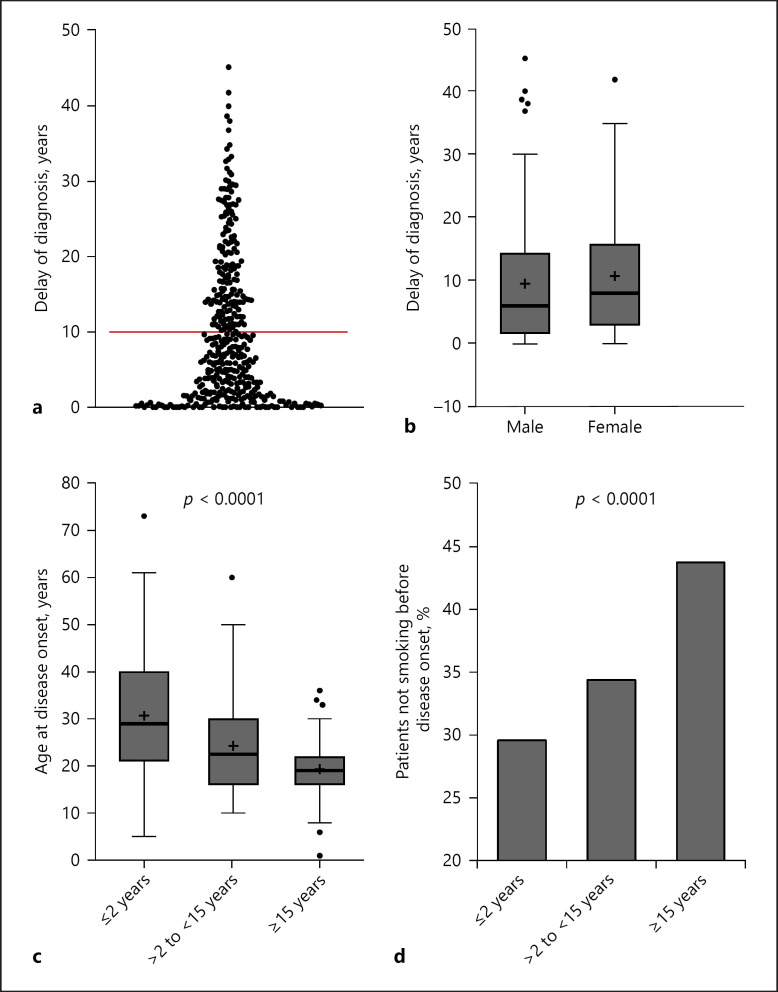

Fig. 2.

Delay of diagnosis in patients with HS. a Distribution of time in years from occurrence of first HS symptoms until diagnosis (n = 394). b Years between first symptoms and HS diagnosis in male and female patients (n = 394). c Age at disease onset in 3 patient groups with different delays in diagnosis of HS (≤2 years; >2 to <15 years; ≥15 years) since first symptoms occurred (p value of ANOVA) presented in Tukey-type box plots, with the box extending from the 25th to 75th percentiles of values, the line in the middle of the box and “+” representing the median and the mean, respectively, the maximum length of box whiskers corresponding to 1.5 times the interquartile distance, and the values plotted individually representing outliers (n = 394). d Percentage of patients in the 3 patient groups with different delay in diagnosis (n = 394), who were non-smokers before disease onset (p value of chi-square test). HS, hidradenitis suppurativa.

First, we examined the patient characteristics regarding their association with delayed diagnosis and observed that the length of delay for male versus female patients was similar (Fig. 2b). The division of the total study cohort into the 3 groups (25/50/25% of the total study cohort) according to the duration of the delay in diagnosis (short/moderate/long diagnosis delay) produced the following thresholds: “diagnosis 2 years after first symptoms” (threshold between cohorts with short and moderate delay) and “diagnosis 15 years after first symptoms” (threshold between cohorts with moderate and long delay; Fig. 1). Analyzing these groups with respect to numerous parameters, we found that the age at disease onset influenced the time until correct diagnosis. The patients with short delay were older at the time of first symptoms (Fig. 2c). Accordingly, the age at disease onset negatively correlated with the length of diagnosis delay (rS = −0.392, p < 0.0001). Interestingly, there was also an association between smoking behavior at disease onset and diagnostic delay; a significantly larger proportion of non-smokers was detected in the group with the longest delay (Fig. 2d). In contrast, we did not detect any significant differences between these 3 patient groups regarding the localization and nature of first cutaneous symptoms.

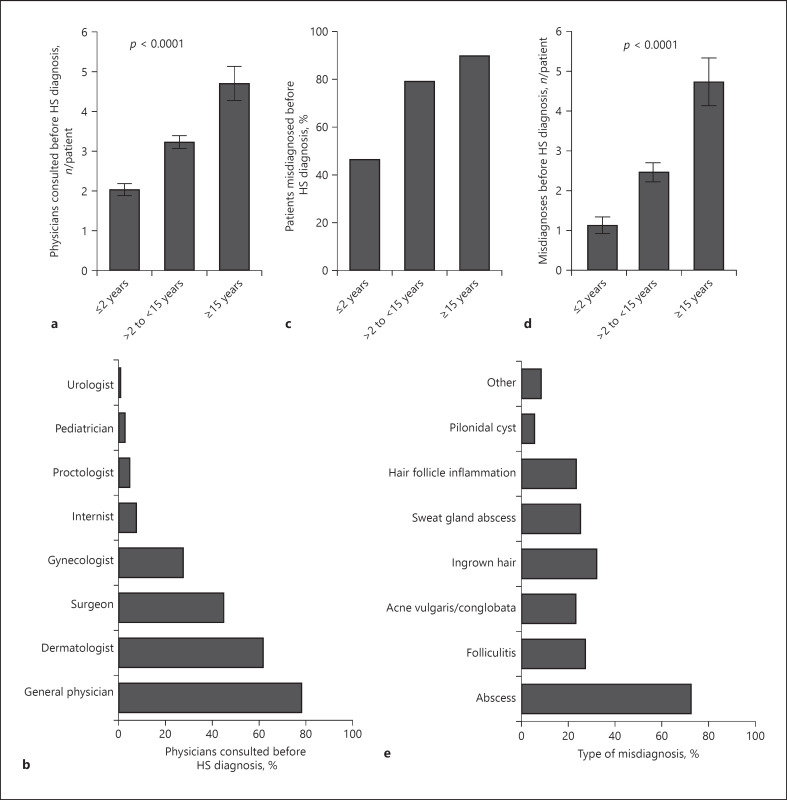

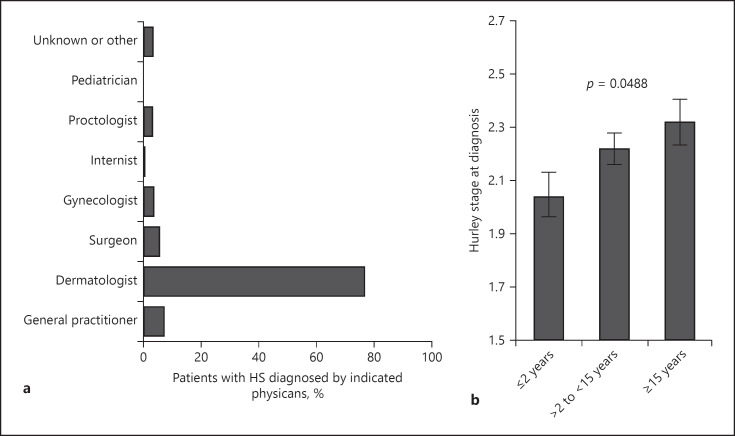

The in-depth analysis further revealed that the length of diagnosis delay positively correlated with the number of physicians that the patient consulted before HS diagnosis (rS = 0.383, p < 0.0001). Accordingly, patients with the longest delay in HS diagnosis had consulted almost 5 physicians on average, significantly more than patients with short diagnostic delays (Fig. 3a). The majority of the patients had seen general practitioners, followed by dermatologists, surgeons, and gynecologists. Patients rarely visited internists, proctologists, pediatricians, or urologists (Fig. 3b). Although the diagnostic criteria for HS have been well established, almost 80% of the patients with HS with moderately late diagnosis and almost 90% of those with late diagnosis had been misdiagnosed compared with 46.5% of patients with early HS diagnosis (Fig. 3c). Moreover, patients with late diagnosis experienced, on average, almost 5 misdiagnoses (Fig. 3d). Generally, the length of diagnosis delay positively correlates with the number of misdiagnoses (rS = 0.291, p < 0.0001). Abscesses, ingrown hairs, and folliculitis were the most common false diagnoses. Other misdiagnoses included acne conglobata or even acne vulgaris (Fig. 3e). Although different physicians examined the patients during diagnosis lag, dermatologists diagnosed the disease in the majority of cases (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 3.

Preceding misdiagnosis in patients with HS. a Number of consulted physicians (mean ± SEM) per patient before HS diagnosis in the 3 patient groups with different delay in diagnosis (n = 380, p value of ANOVA). b Percentage of patients visiting respective physicians before HS diagnosis. c Percentage of misdiagnosed patients in the 3 patient groups with different delay in diagnosis (n = 390). d Number of misdiagnoses (mean ± SEM) experienced before HS diagnosis in the 3 patient groups with different delay in diagnosis (n = 341, p value of ANOVA). e Percentage of specific misdiagnoses before HS was confirmed. HS, hidradenitis suppurativa.

Fig. 4.

Physicians involved in diagnosis and disease severity at diagnosis. a Percentage of patients whose HS was correctly diagnosed by the indicated specialist physicians. b Disease severity reflected by Hurley stage (mean ± SEM) in the 3 patient groups with different delay in diagnosis at time of HS diagnosis based on patients' information (n = 299, p value of ANOVA). HS, hidradenitis suppurativa.

Our further investigation focused on the consequences of HS diagnosis delay. Importantly, the length of diagnosis delay positively correlated with the HS severity at the time of diagnosis (rS = 0.161, p = 0.005). Accordingly, the Hurley stage at diagnosis was significantly higher in patients with delayed diagnosis compared with those with earlier diagnosis (Fig. 4b).

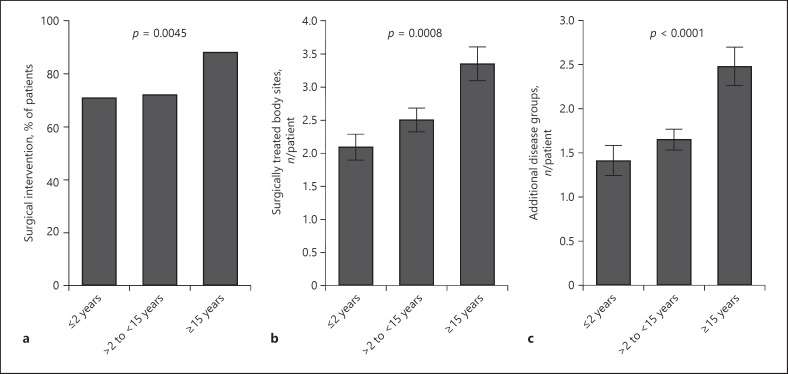

At study enrollment, 75.6% of all patients had experienced at least one surgical intervention. This was most evident in patients with the most delayed HS diagnosis, approximately 90% of whom underwent surgery (Fig. 5a). Moreover, the number of surgically treated sites per patient in this group was higher than in patient groups with earlier diagnosis (Fig. 5b). Accordingly, the length of diagnosis delay positively correlated with the number of surgically treated sites in the total study cohort (rS = 0.212, p < 0.0001). This was particularly prominent if abscess incision was used as the surgical intervention (rS = 0.204, p < 0.0001).

Fig. 5.

Consequences of diagnosis delay regarding surgery history and current concomitant diseases. a Percentage of patients in the 3 patient groups with different delay in diagnosis who underwent surgical interventions before study enrollment (n = 394, p value of chi-square test). b Number of surgically treated sites (mean ± SEM) per patient before study enrollment in the 3 patient groups with different delays in diagnosis (n = 391, p value of ANOVA). c Number of concomitant diseases (mean ± SEM) per patient at time of study enrollment in the 3 patient groups with different delays in diagnosis (n = 394, p value of ANOVA). HS, hidradenitis suppurativa.

As a high proportion of HS patients suffer from comorbidities, we investigated the association between diagnosis delay and concomitant diseases. At study enrollment, patients with delayed HS diagnosis experienced more comorbidities than patients with earlier diagnosis (Fig. 5c). Accordingly, the length of diagnosis delay positively correlated with the number of concomitant diseases (rS = 0.209, p < 0.0001). The largest difference between the subgroups with the shortest and the longest diagnosis delays was observed in musculoskeletal system disorders (25.3 vs. 41.4%, respectively; p < 0.016) and mental impairments (11.1 vs. 25.3%; p < 0.010). Interestingly, the delay of diagnosis positively correlated with the depression score of Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) collected at study enrollment (rS = 0.116, p < 0.02). As expected, there was no difference in the incidence of accidents (13.1 vs. 16.3%; p < 0.547). Even when adjusted for age at study enrollment and smoking status, the delay in diagnosis was significantly associated with the number of comorbidities (p = 0.0370). When compared with the group with the shortest diagnosis delay (≤2 years), the expected number of comorbidities in the group with longest delay (≥15 years) increased by a factor of 1.44 (p = 0.0102).

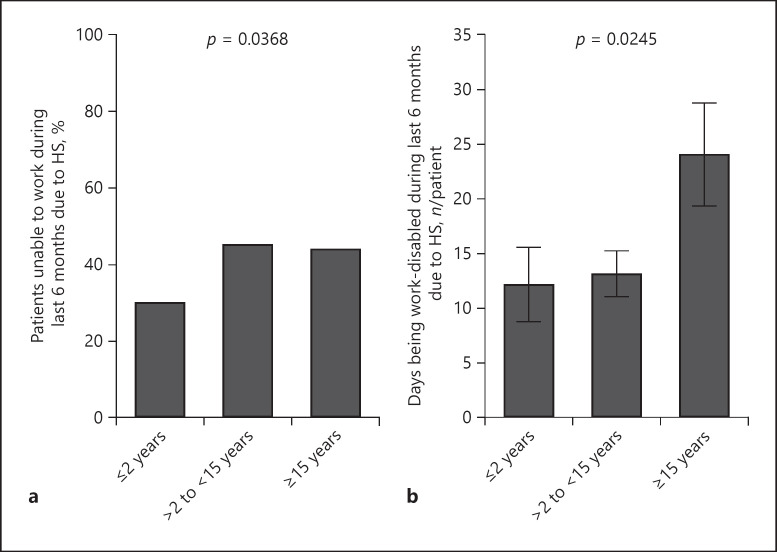

Considering the above-mentioned associations between the delay in HS diagnosis and its consequences for patient health status, we aimed to explore the effect of delay on patient professional life. In doing so we found that patients with longer delays in HS diagnosis reported an inability to work during the last 6 months before study enrolment more frequently than those with shorter delay (Fig. 6a). Moreover, the number of days being work-disabled because of HS during these 6 months significantly increased with delay of diagnosis (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6.

Association of diagnosis delay with patients' work disability. a Percentage of patients unable to work owing to HS in the last 6 months in 3 patient groups with different delay in diagnosis (n = 388, p value of chi-square test). b Number of days (mean ± SEM) during which patients in the 3 patient groups with different delays in diagnosis were unable to work owing to HS in the last 6 months (n = 381, p value of ANOVA). HS, hidradenitis suppurativa.

Discussion

This is the first real-world data-based, prospective study in patients with HS that assessed the burden of late diagnosis, not only on disease progress but also on the professional lives of patients and the healthcare system in Germany. In contrast, previously published data were based on information gathered either from specialized HS units or from insurances [26, 27]. In our study cohort that may represent the entire spectrum of patients with HS, the first symptoms of disease appeared at an average age of 24.6 ± 10.5 years. Ten years later, HS patients in Germany obtained the diagnosis, which implies an almost 2-year longer delay than in neighboring France [27]. The comparison to psoriasis, another TNF-α/IL-17 inflammatory skin disease [28], where diagnosis can last up to 1.6 ± 4.8 years [26], impressively showed how dramatic the situation in care of HS patients currently is. In our study, patients with delayed HS diagnosis were younger. One possible explanation for this is that physicians often associate HS with chronicity and, therefore, suspect the disease in older people. Thus, age should not be a criterion for HS diagnosis. Similarly, in non-smoking patients, HS was diagnosed later than in patients who smoked, perhaps because HS is considered as a disease of smokers. However, about 35% of our patients were non-smokers at disease onset, strongly suggesting that smoking habits do not clearly help with diagnosing HS.

Our study points out several consequences of the delay in HS diagnosis. First, the longer the delay, the higher the number of physicians that were visited before diagnosis. This suggests that patients with HS make an effort to find the correct diagnosis and the appropriate therapy. The physicians visited in that context mainly comprised general physicians, dermatologists, surgeons, and gynecologists. Internists, proctologists, pediatricians, or urologists were visited less frequently. The diversity of the visited physicians reflects the complexity of the disease. However, the reason for failing to diagnose HS remains unclear. Since well-established diagnostic criteria have simplified the accurate diagnosis of HS, we assume that medical care providers were not familiar with the disease. As a consequence of visiting diverse physicians, patients experience several misdiagnoses, inevitably leading to patient frustration, increased costs, or even inappropriate therapy. On average, almost 5 incorrect diagnoses have been made for patients with a delay in HS diagnosis of >15 years. Furthermore, the incorrect diagnosis in combination with the simultaneous appearance of new lesions might result in anxiety and depression and that could explain the positive correlation between length of diagnosis delay and the depression score of HADS.

The importance of early recognition and diagnosis of HS is emphasized by the fact that during the time lost until HS diagnosis, the disease progresses from inflammatory manifestations to tissue destruction. In our cohort, Hurley stage gradually increased with diagnosis delay. Patients with delayed diagnosis also reported more surgically treated sites, increasing the burden for patients. Importantly, the number of treated sites most significantly correlated with diagnosis delay, when abscess incision was the applied surgical intervention. Abscess incision is a minimal intervention that leads to rapid and effective pain relief [1]. However, it has no influence on the long-term course of HS, as inflammatory skin alterations reoccur promptly [1, 29]. Furthermore, frequent surgical interventions increase the medical care costs. Even when compared with patients with severe psoriasis, HS patients showed greater utilization of high-cost medical services, such as emergency department and inpatient care [30]. Importantly, besides the disease severity itself, an increase in the number of comorbidities was associated with the delay of HS diagnosis. This might be caused by the fact that HS patients until diagnosis did not obtain systemic medical treatments to control inflammation. In fact, as already reported for psoriasis, the TNF-α/IL-17-dominated inflammation increases the risk for cardiovascular comorbidity [23, 31]. Notably, the continuous systemic anti-TNF-α or anti-IL-17 therapy seems to be capable to reduce the risk [24]. Similarly, early detection and inflammation reducing treatment of HS might be of major importance in preventing comorbidities.

Recently published data show a higher rate of unemployment in patients with HS compared with control population (25.1 vs. 5.9%) [32]. The increased unemployment rates may explain the lower socioeconomic status of patients with HS, as deduced from their mean household incomes and home values on a neighborhood level [33]. In a limited cohort of patients with HS, the number of work days lost per year has been estimated to be 33.6 ± 26.1 [10]. In our study, the total average number of lost work days during 6 months was 16.2 ± 36.23, matching excellently the previous data. In this context, we have shown that the delay in HS diagnosis has an effect on the number of lost work days. In fact, the average number of lost work days over a 6-month period significantly increased from approximately 12 for patients with <15 years of diagnosis delay to approximately 25 for patients with ≥15 years of diagnosis delay. Disease severity, operations, and secondary diseases are all associated with delays in diagnosis and can be responsible for this restriction of the work ability.

By including HS patients visiting a wide spectrum of medical care settings without any selection, we intended to receive representative data for the entire spectrum of patients with HS. However, patients not seeking medical care, for example, because of mild disease or spontaneous remission were not captured in this trial. Further limitations of the study design include recall bias and self-reporting questionnaires; however, in order to improve data collection and avoid missing or ambiguous data, questionnaire completion was supervised. In conclusion, this study provides a detailed insight into HS diagnosis and the consequences of its delay. Our results highlight the need for increased awareness and early recognition of HS in order to ensure prompt therapy initiation for those disadvantaged patients. This can be achieved by continuous education focused on physicians treating HS patients, like general practitioners, gynecologists, or surgeons, as well as by increasing the public awareness for HS.

Key Message

There is an enormous delay in the diagnosis of hidradenitis suppurativa, which is associated with an increased number of concomitant diseases and impairment of the patients' professional life.

Statement of Ethics

The Ethics Committee of Charité − Universitätsmedizin Berlin approved the study protocol. All patients provided written informed consent. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki on Ethical Principles for Medical Research and has been registered in the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS-ID: DRKS00013778).

Conflict of Interest Statement

G.K. has received honoraria for participation in advisory boards, in clinical trials, and/or as speaker from AbbVie Deutschland GmbH & Co. KG, Abbott GmbH, Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd., Basilea Pharmaceutica Ltd., Bayer AG, Biogen IDEC GmbH, Celgene GmbH, Janssen-Cilag GmbH, LEO Pharma GmbH, Lilly Deutschland GmbH, MSD Sharp & Dohme GmbH, Novartis Pharma GmbH, Parexel International GmbH, Pfizer Deutschland GmbH, and UCB Pharma GmbH. K.W. has received research grants, travel grants, consulting honoraria, and/or lecturer honoraria from AbbVie Inc., AbbVie Deutschland GmbH & Co. KG, Bayer Schering Pharma AG, Celgene GmbH, Flexopharm GmbH & Co. KG, Generon Corporation Ltd., Janssen Pharmaceutica NV, Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Services LLC, Novartis Pharma GmbH, Pfizer Deutschland GmbH, and UCB Pharma GmbH. S.S.-B. has received honoraria for participation in advisory boards, in clinical trials and/or as speaker from AbbVie Inc., AbbVie Deutschland GmbH & Co. KG, Novartis Pharma GmbH, and Pfizer Deutschland GmbH. S.K. has no conflicts of interest to declare. S.G.-K. is an employee of AbbVie Deutschland GmbH & Co. KG. S.B. is a former employee of AbbVie Deutschland GmbH & Co. KG. R.S. has received research grants, scientific awards, or honoraria for participation in advisory boards, clinical trials, or as speaker for one or more of the following: AbbVie Inc., AbbVie Deutschland GmbH & Co. KG, Bayer Schering Pharma AG, Biogen IDEC GmbH, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH & Co. KG, Celgene GmbH, Celgene International II Sàrl, Charité Research Organisation GmbH, Dr. Willmar Schwabe GmbH & Co. KG, Flexopharm GmbH & Co. KG, Generon Corporation ltd., JanssenCilag GmbH, La Roche-Posay Laboratoire Dermatologique Deutschland, Novartis Pharma GmbH, Parexel International GmbH, Pfizer Deutschland GmbH, Sanofi-Aventis Deutschland GmbH, TFS Trial Form Support GmbH, UCB Pharma GmbH.

Funding Sources

This study was supported by AbbVie Deutschland GmbH & Co. KG.

Author Contributions

S.B., R.S., and S.S.-B.: substantial contributions to the conception and design of the PIRANHA study. R.S. and G.K.: substantial contributions to the conception or design of the manuscript. S.G.-K., S.B., and R.S.: substantial contributions to the acquisition of data for the manuscript. S.K., R.S., K.W., S.G.-K., and G.K.: substantial contributions to the analysis and interpretation of data for the manuscript. G.K., K.W., and R.S.: drafting the manuscript. S.K., S.G.-K., S.S.-B., and S.B.: revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors finally approved the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Susanne Weste, who is a former AbbVie employee, for her appreciated support in organizing and conducting this trial. Susanne Weste's contributions were performed while she was an AbbVie employee. We thank Julia Triebus (Charité) for assisting with the figure preparation. The design, study conduct, and financial support for the study were provided by AbbVie. AbbVie participated in the interpretation of data, review, and approval of the publication.

References

- 1.Sabat R, Jemec GB, Matusiak Ł, Kimball AB, Prens E, Wolk K. Hidradenitis suppurativa. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020 Mar;6((1)):18. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-0149-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ingram JR, Jenkins-Jones S, Knipe DW, Morgan CL, Cannings-John R, Piguet V. Population-based Clinical Practice Research Datalink study using algorithm modelling to identify the true burden of hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2018 Apr;178((4)):917–24. doi: 10.1111/bjd.16101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kromann CB, Deckers IE, Esmann S, Boer J, Prens EP, Jemec GB. Risk factors, clinical course and long-term prognosis in hidradenitis suppurativa: a cross-sectional study. Br J Dermatol. 2014 Oct;171((4)):819–24. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garg A, Papagermanos V, Midura M, Strunk A. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa among tobacco smokers: a population-based retrospective analysis in the U.S.A. Br J Dermatol. 2018 Mar;178((3)):709–14. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karagiannidis I, Nikolakis G, Sabat R, Zouboulis CC. Hidradenitis suppurativa/Acne inversa: an endocrine skin disorder? Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2016 Sep;17((3)):335–41. doi: 10.1007/s11154-016-9366-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horváth B, Janse IC, Sibbald GR. Pain management in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015 Nov;73((5 Suppl 1)):S47–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolkenstein P, Loundou A, Barrau K, Auquier P, Revuz J, Quality of Life Group of the French Society of Dermatology Quality of life impairment in hidradenitis suppurativa: a study of 61 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007 Apr;56((4)):621–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.08.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurek A, Peters EM, Chanwangpong A, Sabat R, Sterry W, Schneider-Burrus S. Profound disturbances of sexual health in patients with acne inversa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67((3)):422–8 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schneider-Burrus S, Jost A, Peters EM, Witte-Haendel E, Sterry W, Sabat R. Association of Hidradenitis Suppurativa With Body Image. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Apr;154((4)):447–51. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.6058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matusiak L, Bieniek A, Szepietowski JC. Hidradenitis suppurativa markedly decreases quality of life and professional activity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62((4)):706–8 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sabat R, Chanwangpong A, Schneider-Burrus S, Metternich D, Kokolakis G, Kurek A, et al. Increased prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with acne inversa. PLoS One. 2012;7((2)):e31810. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller IM, Ellervik C, Vinding GR, Zarchi K, Ibler KS, Knudsen KM, et al. Association of metabolic syndrome and hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2014 Dec;150((12)):1273–80. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Egeberg A, Gislason GH, Hansen PR. Risk of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events and All-Cause Mortality in Patients With Hidradenitis Suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2016 Apr;152((4)):429–34. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.6264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richette P, Molto A, Viguier M, Dawidowicz K, Hayem G, Nassif A, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa associated with spondyloarthritis— results from a multicenter national prospective study. J Rheumatol. 2014 Mar;41((3)):490–4. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.130977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schneider-Burrus S, Witte-Haendel E, Christou D, Rigoni B, Sabat R, Diederichs G. High Prevalence of Back Pain and Axial Spondyloarthropathy in Patients with Hidradenitis Suppurativa. Dermatology. 2016;232((5)):606–12. doi: 10.1159/000448838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolk K, Warszawska K, Hoeflich C, Witte E, Schneider-Burrus S, Witte K, et al. Deficiency of IL-22 contributes to a chronic inflammatory disease: pathogenetic mechanisms in acne inversa. J Immunol. 2011 Jan;186((2)):1228–39. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van der Zee HH, de Ruiter L, van den Broecke DG, Dik WA, Laman JD, Prens EP. Elevated levels of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-10 in hidradenitis suppurativa skin: a rationale for targeting TNF-α and IL-1β. Br J Dermatol. 2011 Jun;164((6)):1292–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hessam S, Sand M, Gambichler T, Skrygan M, Rüddel I, Bechara FG. Interleukin-36 in hidradenitis suppurativa: evidence for a distinctive proinflammatory role and a key factor in the development of an inflammatory loop. Br J Dermatol. 2018 Mar;178((3)):761–7. doi: 10.1111/bjd.16019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lima AL, Karl I, Giner T, Poppe H, Schmidt M, Presser D, et al. Keratinocytes and neutrophils are important sources of proinflammatory molecules in hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2016 Mar;174((3)):514–21. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Witte-Händel E, Wolk K, Tsaousi A, Irmer ML, Mößner R, Shomroni O, et al. The IL-1 Pathway Is Hyperactive in Hidradenitis Suppurativa and Contributes to Skin Infiltration and Destruction. J Invest Dermatol. 2019 Jun;139((6)):1294–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2018.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolk K, Wenzel J, Tsaousi A, Witte-Händel E, Babel N, Zelenak C, et al. Lipocalin-2 is expressed by activated granulocytes and keratinocytes in affected skin and reflects disease activity in acne inversa/hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2017 Nov;177((5)):1385–93. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsaousi A, Witte E, Witte K, Röwert-Huber HJ, Volk HD, Sterry W, et al. MMP8 Is Increased in Lesions and Blood of Acne Inversa Patients: A Potential Link to Skin Destruction and Metabolic Alterations. Mediators Inflamm. 2016;2016:4097574. doi: 10.1155/2016/4097574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boehncke WH. Systemic Inflammation and Cardiovascular Comorbidity in Psoriasis Patients: causes and Consequences. Front Immunol. 2018 Apr;9:579. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elnabawi YA, Dey AK, Goyal A, Groenendyk JW, Chung JH, Belur AD, et al. Coronary artery plaque characteristics and treatment with biologic therapy in severe psoriasis: results from a prospective observational study. Cardiovasc Res. 2019 Mar;115((4)):721–8. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvz009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taams LS, Steel KJ, Srenathan U, Burns LA, Kirkham BW. IL-17 in the immunopathogenesis of spondyloarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2018 Aug;14((8)):453–66. doi: 10.1038/s41584-018-0044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saunte DM, Boer J, Stratigos A, Szepietowski JC, Hamzavi I, Kim KH, et al. Diagnostic delay in hidradenitis suppurativa is a global problem. Br J Dermatol. 2015 Dec;173((6)):1546–9. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loget J, Saint-Martin C, Guillem P, Kanagaratnam L, Becherel PA, Nassif A, et al. sous l'égide de « ResoVerneil » [Misdiagnosis of hidradenitis suppurativa continues to be a major issue. The R-ENS Verneuil study] Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2018 May;145((5)):331–8. doi: 10.1016/j.annder.2018.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sabat R, Wolk K, Loyal L, Döcke WD, Ghoreschi K. T cell pathology in skin inflammation. Semin Immunopathol. 2019 May;41((3)):359–77. doi: 10.1007/s00281-019-00742-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ritz JP, Runkel N, Haier J, Buhr HJ. Extent of surgery and recurrence rate of hidradenitis suppurativa. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1998;13((4)):164–8. doi: 10.1007/s003840050159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khalsa A, Liu G, Kirby JS. Increased utilization of emergency department and inpatient care by patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015 Oct;73((4)):609–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piaserico S, Osto E, Famoso G, Zanetti I, Gregori D, Poretto A, et al. Treatment with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors restores coronary microvascular function in young patients with severe psoriasis. Atherosclerosis. 2016 Aug;251:25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2016.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Theut Riis P, Thorlacius L, Knudsen List E, Jemec GB. A pilot study of unemployment in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa in Denmark. Br J Dermatol. 2017 Apr;176((4)):1083–5. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deckers IE, Janse IC, van der Zee HH, Nijsten T, Boer J, Horvath B, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is associated with low socioeconomic status (SES): a cross-sectional reference study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75((4)):755–9.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.04.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data

Supplementary data