Abstract

Introduction

There is limited data on the experience with insertable cardiac monitors (ICMs) in patients with Brugada syndrome.

Objective

To evaluate the outcome of ICM in symptomatic patients with Brugada syndrome who are at suspected low risk of sudden cardiac death (SCD).

Methods

We conducted a prospective single-center cohort study including all symptomatic patients with Brugada syndrome who received an ICM (Reveal LINQ) between July 2014 and October 2019. The main indication for monitoring was to exclude ventricular arrhythmias as the cause of symptoms and to establish a symptom-rhythm relationship.

Results

A total of 20 patients (mean age, 39 ± 12 years; 55% male) received an ICM during the study period. Nine patients (45%) had a history of syncope (presumed nonarrhythmogenic), and 5 patients had a recent syncope (<6 months). During a median follow-up of 32 months (interquartile range, 11–36 months), 3 patients (15%) experienced an episode of nonsustained ventricular arrhythmia. No patient died suddenly or experienced a sustained ventricular arrhythmia, and no patient had a recurrence of syncope. Overall, 17 patients (85%) experienced symptoms during follow-up, of whom 10 patients had an ICM-detected arrhythmia. In 4 patients (20%), the ICM-detected arrhythmia was an actionable event. ICM-guided management included antiarrhythmic drug therapy for symptomatic ectopic beats (n = 3), pulmonary vein isolation, and oral anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation (n = 1), electrophysiological study for risk stratification (n = 1), and pacemaker implantation for atrioventricular block (n = 1).

Conclusions

An ICM can be used to exclude ventricular arrhythmias in symptomatic patients with Brugada syndrome at low risk of SCD. Furthermore, an ICM-detected arrhythmia changed clinical management in 20% of patients.

Keywords: Syndrome, Insertable cardiac monitor, Syncope, Sudden cardiac death, Ventricular arrhythmia

Introduction

Risk stratification in patients with Brugada syndrome is challenging [1, 2, 3]. Several risk factors for arrhythmic events (sustained ventricular arrhythmia or sudden cardiac death [SCD]) have been identified, but the most robust predictors are a spontaneous type 1 Brugada electrocardiogram (ECG) pattern and presumed arrhythmogenic syncope [1, 2, 3]. There is controversy over the predictive role of inducible sustained ventricular arrhythmia during electrophysiological study (EPS), but it seems to be informative for predicting arrhythmic risk in moderate-risk patients when using less aggressive stimulation protocols (up to double extrastimuli) [1, 2, 3, 4, 5].

The current guidelines recommend an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) in patients with Brugada syndrome with aborted cardiac arrest, documented spontaneous sustained ventricular arrhythmias, or a combination of spontaneous type 1 Brugada ECG pattern and a history of syncope [6, 7]. The downside of ICD therapy is the risk of late complications, inappropriate ICD shocks, and psychological burden [8].

In clinical practice, physicians are confronted with patients with Brugada syndrome who have symptoms such as palpitations, near-syncope, or nonarrhythmic syncope [5, 9]. Some symptoms are caused by anxiety for arrhythmic events, but it may be difficult to differentiate this from clinically relevant arrhythmias. Insertable cardiac monitors (ICM) are increasingly being used in doubtful cases to exclude ventricular arrhythmias as the cause of symptoms [5, 10, 11]. The recent ESC guidelines and expert consensus conference report support the use of ICMs in patients with Brugada syndrome and recurrent unexplained syncope [12, 13]. The aim of the present study is to evaluate the use of ICMs in symptomatic patients with Brugada syndrome who are presumed to be at low risk of SCD.

Methods

Study Design and Population

The present study is a prospective single-center cohort study which included all symptomatic adults with Brugada syndrome who received an ICM between July 2014 and October 2019. The main indication for arrhythmia monitoring was to exclude ventricular arrhythmias as the cause of symptoms. Most patients have received a 24-h Holter monitoring prior to ICM implantation. Patients with high risk features, such as a spontaneous sustained ventricular arrhythmia, a combination of spontaneous type 1 Brugada ECG pattern and arrhythmic syncope, or positive EPS, were not considered for an ICM but were recommended an ICD [6, 14]. Until 2014, we recommended EPS to all patients with spontaneous or drug-induced Brugada ECG pattern. Thereafter, EPS was only proposed to doubtful cases. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Erasmus MC.

Device Programming and Follow-Up

All ICMs (Reveal LINQ, Medtronic) were implanted subcutaneously using the incision and insertion tool. Furthermore, all patients received a handheld activator to indicate their symptoms when necessary. The ICM was programmed according to local settings: tachycardia detection was set to 176 bpm for 16 beats (nominal setting); bradycardia setting to 30 bpm for 8 beats (nominal 4 beats); pause setting to 4.5 s (nominal 3.0 s); and atrial fibrillation (AF) setting to “AF only.” These settings were chosen to improve the signal-to-noise ratio. All devices were connected to the CareLink network (Medtronic) for remote monitoring. Patients were discharged on the same day of implantation. Ten days after implantation, the patients were seen at the outpatient clinic to check their wound and to interrogate the ICM. Afterwards, the patients were seen regularly at the outpatient clinic according to routine patient care. ICM checkups were performed at the outpatient clinic every 6 months or earlier when necessary based on symptoms or transmitted episodes. Remote monitoring was performed on a daily basis during weekdays. Remote monitoring involves automatic unscheduled transmission of alert events.

Classification of Episodes and Endpoints

All patient-activated episodes and automatically detected episodes were classified. In the case of an inappropriate automatically detected episode, the cause of inappropriate detection was specified, if possible. A regular broad complex tachycardia (BCT) was considered a ventricular arrhythmia if there was a sudden onset and a change in the QRS morphology in comparison to the baseline rhythm. An irregular BCT was considered a ventricular arrhythmia if there was a sudden onset and a polymorphic QRS morphology. A regular broad or small complex tachycardia was considered a supraventricular tachycardia if there was a sudden onset and no change in QRS morphology. In the case of doubt, a second electrophysiologist was consulted for the final diagnosis. Finally, it was established whether a detected arrhythmia resulted in a change in patient management (“actionable event”).

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or as median with corresponding 25th and 75th percentile, as appropriate. Categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 21.

Results

Study Population

A total of 20 patients with Brugada syndrome (mean age 39 ± 12 years; 55% male) received an ICM during the study period. Baseline characteristics of the study population are listed in Tables 1 and 2. Symptoms before ICM implantation consisted of syncope suggestive of a nonarrhythmogenic cause (n = 9, 45%), palpitations (n = 7, 35%), or a combination of near-syncope and palpitations (n = 4, 20%). Of the 9 patients with syncope, 7 patients (78%) had only 1 syncopal event, and 5 patients (56%) had a recent syncope (<6 months before ICM implantation). A detailed patient-level description of patient characteristics is presented in Table 2. There were no ICM- or procedure-related complications.

Table 1.

Clinical baseline characteristics

| Total group (n = 20) | |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 39±12 |

| Gender, male | 11 (55) |

| Family history of SCD in first-degree relatives | 8 (40) |

| History of atrial flutter at age <35 years | 1 (5) |

| Symptoms | |

| Palpitations | 11 (55) |

| Syncope | 9 (45) |

| Near syncope | 4 (20) |

| Systemic systolic ventricular function | |

| Normal left ventricular ejection fraction (≥55%) | 20 (100) |

| Genetic variance | |

| No (likely) pathogenic SCN5A variant | 14 (70) |

| No genetic testing | 4 (20) |

| Pathogenic SCN5A variant | 2 (10) |

| Clinical presentation | |

| Ajmaline induced Brugada ECG | 14 (70) |

| Fever induced Brugada ECG | 4 (20) |

| Spontaneous Brugada ECG | 2 (10) |

| Electrocardiography | |

| Sinus rhythm | 20 (100) |

| PR interval, ms | 169±28 |

| QRS duration, ms | 103±18 |

| QTc duration, ms | 391±22 |

| Fragmented QRS | 4 (20) |

| EP study | 7 (35) |

| No inducible sustained VA | 7 (35) |

| VERP <200 ms | 2 (10) |

| Holter monitoring | 16 (80) |

| No PVCs | 10 (50) |

| ≤1% PVCs | 6 (30) |

| Supraventricular tachycardia | 0 |

| Ventricular tachycardia | 0 |

| SA-ECG | 16 (80) |

| Late potentials | 10 (50) |

Data are presented as n (%) or mean ± standard deviation. ECG, electrocardiogram; EP, electrophysiological; PVC, premature ventricular arrhythmia; SCD, sudden cardiac death; VA, ventricular arrhythmia; VERP, ventricular effective refractory period.

Table 2.

Detailed overview of baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes

| Age at diagnosis, years, and gender | Type of Brugada | Symptoms before ICM | SCD first-degree relatives | SCD <35 years first-degree relatives | Proband status | SND | History of inducible VA | SCN5A variant | Symptoms during follow-up | ICM-detected rhythm | Management |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20, M | Ajmaline | Syncope | − | − | + | − | NA | NA | Symptoms (not specified) | SR | − |

| 22, M | Ajmaline | Syncope | + | + | − | − | NA | − | Asymptomatic | − | − |

| 23, M | Ajmaline | Near-syncope, palpitations | − | − | + | − | NA | − | Near-syncope, palpitations | PAC/PVC, SVT, NSVT | AAD, EPS |

| 24, F | Ajmaline | Near-syncope, palpitations | + | − | − | − | − | NA | Asymptomatic | − | − |

| 29, M | Ajmaline | Palpitations | − | − | − | − | − | − | Asymptomatic | ST, SB | − |

| 30, F | Ajmaline | Palpitations | + | − | + | − | NA | − | Symptoms (not specified) | SR | − |

| 35, M | Ajmaline | Palpitations | − | − | + | − | − | − | Palpitations, amaurosis fugax | PAC, AF | AAD, NOAC, PVI |

| 37, M | Ajmaline | Syncope | + | + | + | − | − | − | Palpitations | PAC | − |

| 41, M | Ajmaline | Syncope | + | − | + | − | NA | − | Palpitations | PVC | − |

| 41, F | Ajmaline | Near-syncope, palpitations | + | + | + | − | NA | NA | Palpitations | SR | − |

| 41, F | Ajmaline | Syncope | + | − | + | − | NA | − | Palpitations | PVC, NSVT | − |

| 43, M | Ajmaline | Syncope | + | + | − | − | − | + | Palpitations | SA | − |

| 44, F | Ajmaline | Near-syncope, palpitations | − | − | − | − | − | − | Palpitations | PVC | − |

| 55, F | Ajmaline | Syncope | − | − | + | − | NA | − | Symptoms (not specified) | SR | − |

| 25, F | Fever | Palpitations | − | − | − | − | NA | + | Near-syncope, palpitations | PAC/PVC, SA | − |

| 39, M | Fever | Syncope | − | − | − | − | NA | − | Symptoms (not specified) | SR | − |

| 42, M | Fever | Palpitations | − | − | + | − | − | − | Palpitations | PAC/PVC, NSVT | AAD |

| 50, F | Fever | Syncope | − | − | + | + | NA | − | Near-syncope, palpitations | PAC, SVT, AVB, SA | PM |

| 53, F | Spontaneous | Palpitations | − | − | + | − | NA | − | Symptoms (not specified) | SR | − |

| 63, M | Spontaneous | Palpitations | − | − | + | − | NA | NA | Palpitations | SR | − |

Patients are sorted on age at diagnosis and type of Brugada syndrome. AAD, antiarrhythmic drug therapy; AF, atrial fibrillation; AVB, atrioventricular block; ICM, insertable cardiac monitor; NA, not available; NSVT, nonsustained ventricular tachycardia; PAC, premature atrial complexes; PM, pacemaker; PVC, premature ventricular complexes; SA, sinus arrest; SB, sinus bradycardia; SCD, sudden cardiac death; SND, sinus node disease; SR, sinus rhythm; ST, sinus tachycardia; SVT, supraventricular tachycardia; VA, ventricular arrhythmia. +, present; −, absent.

ICM-Detected Episodes

During a median follow-up of 32 months (IQR, 11–36 months), a total of 1,912 episodes were transmitted to the CareLink network system (Appendix). There were 904 (47%) patient-activated episodes and 1,008 (53%) automatically detected episodes. The majority of patient-activated episodes (98%) comprised sinus rhythm with or without ectopy; thus, only a minority of patient-activated episodes comprised a significant arrhythmia.

Detection of Ventricular Arrhythmia Episodes

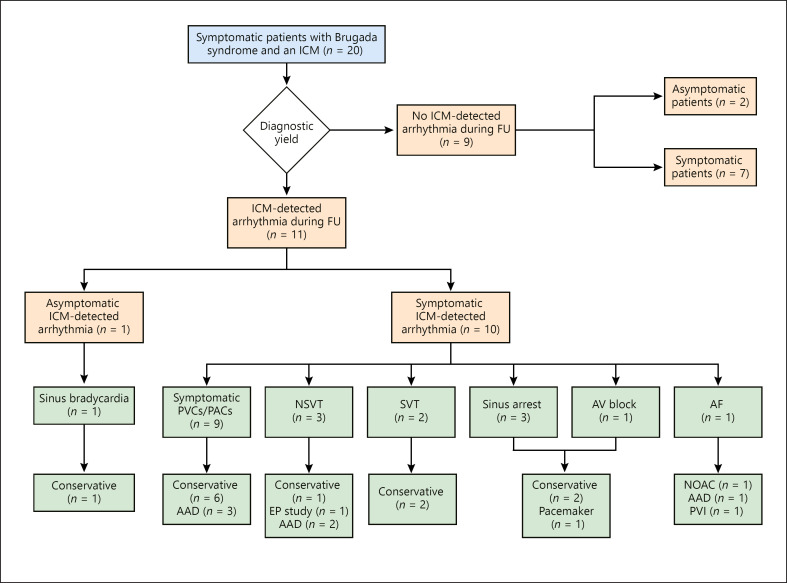

During follow-up, 3 patients (15%) experienced an episode of nonsustained ventricular arrhythmia (Table 2; Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Overview of insertable cardiac monitor (ICM)-detected arrhythmias and the therapeutic management. One patient had both sinus arrest and atrioventricular (AV) block and required a pacemaker. AAD, anti-arrhythmic drug; AF, atrial fibrillation; EP, electrophysiological; NSVT, nonsustained ventricular tachycardia; PAC, premature atrial complex; PVC, premature ventricular complex; PVI, pulmonary vein isolation; SVT, supraventricular tachycardia.

The first patient was a 23-year-old male with ajmaline-induced Brugada syndrome and an anxiety disorder (treated by psychiatrist) who received an ICM due to recurrent unexplained symptoms (i.e., near-syncope and palpitations). During follow-up, he experienced 6 episodes of symptomatic regular slow monomorphic nonsustained ventricular arrhythmia (4–8 beats, patient-activated). It is important to note that the majority of the patient-activated episodes did not show any arrhythmia. The patient underwent an EPS which was negative, and based on the negative EPS, he was treated conservatively.

The second patient was a 41-year-old female with ajmaline-induced Brugada syndrome and a positive family history of SCD who received an ICM for a history of presumed nonarrhythmogenic syncope. She experienced one symptomatic episode of irregular nonsustained ventricular arrhythmia (9 beats, patient-activated) with palpitations 5 months after ICM implantation. It was decided to continue arrhythmia monitoring and to perform an EPS if there was a recurrent ventricular arrhythmia episode.

The third patient was a 42-year-old male with fever-induced Brugada syndrome, fragmented QRS, and a negative EPS who received an ICM for palpitations. He experienced a symptomatic regular monomorphic nonsustained ventricular arrhythmia (7 beats, patient-activated) 16 months after ICM implantation. Because he also had symptomatic ventricular ectopic beats, he was treated successfully with quinidine sulphate. No ventricular arrhythmia was seen thereafter. His ICM was explanted 3.5 years after implantation.

No patient died suddenly or experienced a sustained ventricular arrhythmia.

Symptom-Rhythm Correlation

No patient experienced syncope during a median follow-up of 32 months (IQR, 11–36 months). Overall, 17 patients (85%) experienced any symptom during follow-up (Fig. 1; Table 2). Ten of 17 (59%) symptomatic patients had an ICM-detected arrhythmia. In 4 patients (20%), the ICM-detected arrhythmia was considered an actionable event. ICM-guided management included antiarrhythmic drug therapy for symptomatic ectopic beats (n = 3), pulmonary vein isolation and oral anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation (n = 1), EPS for risk stratification (n = 1), and pacemaker implantation for high-degree atrioventricular block (n = 1).

Two patients with ventricular arrhythmia episodes and actionable events have been described previously. Furthermore, a 35-year-old male with ajmaline-induced Brugada syndrome experienced symptomatic paroxysmal AF detected by the ICM. He was started on oral anticoagulation and sotalol. In addition, he was scheduled for a pulmonary vein isolation.

A 50-year-old female with recurrent syncope, fever-induced Brugada syndrome and a positive family history of SCD at young age (third-degree relative) received a dual-chamber pacemaker after her ICM detected a 10 s pause due to high-degree AV block. During a follow-up of 18 months after pacemaker implantation, no episode of ventricular arrhythmia was documented by her pacemaker.

Overall, in 10 patients (45%) the ICM was explanted. In 9 patients, the ICM was explanted due to end of battery life.

Discussion

The present study is one of the largest case series evaluating the outcome of continuous monitoring in adults with Brugada syndrome with low risk of SCD. During almost 3 years of follow-up, there was a low risk of nonsustained ventricular arrhythmia and an absence of sustained ventricular arrhythmia. In 4 patients (20%), an ICM-guided diagnosis resulted in a change of patient management. No patient required an ICD during follow-up. Thus, an ICM may provide reassurance to a symptomatic patient with Brugada syndrome.

Risk Stratification

Brugada syndrome is characterized by an increased risk of SCD. Several risk factors for SCD have been identified including, among others, spontaneous type 1 Brugada ECG pattern, history of arrhythmogenic syncope, positive EPS, family history of SCD <35 years, fractionated QRS, early repolarization in the peripheral leads, increased Tpeak−Tend interval, sinus node dysfunction, first-degree AV block, and nonsustained ventricular arrhythmia [1, 4]. The role of EPS in patients with Brugada syndrome is controversial. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that ventricular arrhythmia induction using single or double extrastimuli was associated with a 2- to 3-fold increased risk of arrhythmic events [4]. However, it is important to note that a negative EPS alone is not sufficient to preclude arrhythmia risk, especially in patients with clinical high-risk features. Using a recently developed risk score (published in 2017) based on clinical parameters, the risk score in our study population ranged from 0 to 3 points corresponding to an estimated 5-year event rate ranging from 1.6 to 16.6% [1]. The arrhythmic event rate in our study population was 0% during a median follow-up of almost 3 years, supporting the clinical judgment not to implant a prophylactic ICD in our study population.

Role of ICM in Brugada Syndrome

An ICM is a sensitive tool to detect paroxysmal arrhythmias and is particularly useful for establishing a symptom-rhythm correlation. In the general population, there is a clear indication for an ICM in patients with recurrent unexplained syncope [12, 15]. Interestingly, the recent ESC guidelines give a class IIa indication (level of evidence C) for an ICM (instead of an ICD) in Brugada patients with recurrent unexplained syncope who are at low risk of SCD [12]. Currently, there is limited published data on the use of ICM in patients with Brugada syndrome [5, 10, 11, 16, 17, 18]. A few case reports in Brugada patients with presumed nonarrhythmogenic syncope have demonstrated the detection of self-terminating sustained ventricular arrhythmia by the ICM [16, 17]. These patients received a prophylactic ICD. Until now, there are 2 reported case series with >10 patients. In 2012, Kubala et al. [10] reported a retrospective analysis of 11 patients (mean age 44 years) with Brugada syndrome and ICM (Reveal DX, Medtronic). Most patients were symptomatic and had a previous EPS; furthermore, half of the study population had a spontaneous type 1 Brugada ECG pattern. During a mean follow-up of 33 months, no ventricular arrhythmic event was documented in patients with recurrence of symptoms. In 2017, Giustetto et al. [5] reported the experience with ICMs in the Piedmont Brugada registry. In this study, 13 patients with neurally mediated syncope and 14 patients with unexplained, suspected arrhythmia-related syncope received an ICM. During follow-up, no patient had an arrhythmic event (defined as ventricular fibrillation, sustained ventricular arrhythmia, or SCD). Our study expands the experience with ICM in symptomatic patients with Brugada syndrome and is in line with previous studies by demonstrating no sustained ventricular arrhythmias during follow-up. In contrast to previous studies, we reported all ICM-detected arrhythmic events independent of initial symptoms.

Considerations

There seems to be a role to use ICM in selected symptomatic Brugada patients. Patients who are recently diagnosed with Brugada syndrome usually experience increased anxiety considering the increased risk of SCD. The heightened awareness of palpitations or near-syncope may be troublesome for patients, and in this respect an ICM with remote monitoring may provide reassurance by excluding clinically relevant arrhythmias during symptoms.

On the other hand, when using an ICM, there are some limiting factors which should be considered such as device costs, data overload, clinical relevance of device-detected ventricular arrhythmia and medical overuse. The issue of data overload is highlighted by the recording of almost 2,000 episodes in 20 patients in our study population. A dedicated telemonitoring staff with a proper infrastructure is advised before providing such a service to patients.

Study Limitations

Although this is one of the largest reported series on the use of ICM in Brugada patients, the sample size is still relatively small. This may impact on the external validity of the study results. Furthermore, a longer follow-up duration may potentially increase the likelihood of detecting ventricular arrhythmias. However, the average battery life of the Reveal LINQ is 3 years. A longer follow-up would thus require replacement of the ICM. Finally, asymptomatic ventricular arrhythmia episodes which are shorter (<16 beats) or slower (<176 bpm) than the programmed cutoff values will be missed. Therefore, the true incidence of ventricular arrhythmia episodes will most likely be higher in this population.

Conclusion

An ICM can be used to exclude ventricular arrhythmias in symptomatic patients with Brugada syndrome at presumed low risk of SCD, thereby providing reassurance. Furthermore, an ICM-detected arrhythmia changed clinical management in 20% of patients.

Statement of Ethics

The institutional review board of the Erasmus MC reviewed the study, and this study was not subjected to the Dutch Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act. The study was carried out according to the ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects established by Declaration of Helsinki, protecting the privacy of all the participants and the confidentiality of their personal information.

Disclosure Statement

S.C.Y. has received a research grant and consulting fees from Medtronic.

Funding Sources

No funding was received for this study.

Author Contributions

All authors fulfil the ICMJE criteria for authorship. S.C.Y., J.W.R.H., and T.S.T. designed the study. R.S. and A.A. were responsible for acquisition and analysis of data and drafting the paper. D.A.M.J.T., J.M.A.V., and T.S.T. were responsible for interpretation of data. S.C.Y., T.S.T., J.W.R.H., D.A.M.J.T., and J.M.A.V. critically revised the paper. All authors have read and approved the final version of the paper and take responsibility for the work.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Appendix

Overview of ICM-Detected Arrhythmias

| Total episodes (n = 1,912) | |

|---|---|

| Symptom episodes* | 904 (47) |

| Sinus rhythm | 888 (98) |

| without ectopy | 411 |

| with PVCs | 255 |

| with PACs | 222 |

| Regular broad complex tachycardia 8 | (<1) |

| Regular small complex tachycardia 4 | (<1) |

| Atrial fibrillation 4 | (<1) |

| Brady episodes* | 822 (43) |

| Sinus bradycardia | 818 (99) |

| Sinus rhythm | 2 |

| with undersensing of PVCs | 2 |

| Sinus arrest | 2 (<1) |

| Tachycardia episodes* | 121 (6) |

| Sinus rhythm | 121 (100) |

| without ectopy | 98 |

| with oversensing | 13 |

| with noise | 9 |

| with PACs | 1 |

| Pause episodes* | 53 (3) |

| Sinus rhythm | 48 (91) |

| with sudden drop of R-wave | 41 |

| with small R-waves | 6 |

| with undersensing of PVCs | 1 |

| Sinus arrest | 4 (8) |

| AV-block | 1 (2) |

| Atrial tachycardia* | 11 (<1) |

| Sinus rhythm | 11 (100) |

| Atrial fibrillation* | 1 (<1) |

| Sinus rhythm with PACs | 1 (100) |

Data are presented as n (%).

Episode classification by ICM. AV-block, atrioventricular block; PAC, premature atrial complex; PVC, premature ventricular complex; SA, sino-atrial.

References

- 1.Sieira J, Conte G, Ciconte G, Chierchia GB, Casado-Arroyo R, Baltogiannis G, et al. A score model to predict risk of events in patients with Brugada Syndrome. Eur Heart J. 2017 Jun;38((22)):1756–63. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Priori SG, Gasparini M, Napolitano C, Della Bella P, Ottonelli AG, Sassone B, et al. Risk stratification in Brugada syndrome: results of the PRELUDE (PRogrammed ELectrical stimUlation preDictive valuE) registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012 Jan;59((1)):37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Probst V, Veltmann C, Eckardt L, Meregalli PG, Gaita F, Tan HL, et al. Long-term prognosis of patients diagnosed with Brugada syndrome: Results from the FINGER Brugada Syndrome Registry. Circulation. 2010 Feb;121((5)):635–43. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.887026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sroubek J, Probst V, Mazzanti A, Delise P, Hevia JC, Ohkubo K, et al. Programmed Ventricular Stimulation for Risk Stratification in the Brugada Syndrome: A Pooled Analysis. Circulation. 2016 Feb;133((7)):622–30. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.017885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giustetto C, Cerrato N, Ruffino E, Gribaudo E, Scrocco C, Barbonaglia L, et al. Etiological diagnosis, prognostic significance and role of electrophysiological study in patients with Brugada ECG and syncope. Int J Cardiol. 2017 Aug;241:188–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Priori SG, Blomström-Lundqvist C, Mazzanti A, Blom N, Borggrefe M, Camm J, et al. ESC Scientific Document Group 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: The Task Force for the Management of Patients with Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC) Eur Heart J. 2015 Nov;36((41)):2793–867. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Khatib SM, Stevenson WG, Ackerman MJ, Bryant WJ, Callans DJ, Curtis AB, et al. 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for Management of Patients With Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2018 Sep;138((13)):e272–391. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dereci A, Yap SC, Schinkel AF. Meta-Analysis of Clinical Outcome After Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator Implantation in Patients With Brugada Syndrome. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2019 Feb;5((2)):141–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2018.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olde Nordkamp LR, Vink AS, Wilde AA, de Lange FJ, de Jong JS, Wieling W, et al. Syncope in Brugada syndrome: prevalence, clinical significance, and clues from history taking to distinguish arrhythmic from nonarrhythmic causes. Heart Rhythm. 2015 Feb;12((2)):367–75. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kubala M, Aïssou L, Traullé S, Gugenheim AL, Hermida JS. Use of implantable loop recorders in patients with Brugada syndrome and suspected risk of ventricular arrhythmia. Europace. 2012 Jun;14((6)):898–902. doi: 10.1093/europace/eur319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sakhi R, Theuns DA, Bhagwandien RE, Michels M, Schinkel AF, Szili-Torok T, et al. Value of implantable loop recorders in patients with structural or electrical heart disease. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2018 Jul;52((2)):203–8. doi: 10.1007/s10840-018-0354-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brignole M, Moya A, de Lange FJ, Deharo JC, Elliott PM, Fanciulli A, et al. ESC Scientific Document Group 2018 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope. Eur Heart J. 2018 Jun;39((21)):1883–948. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Antzelevitch C, Yan GX, Ackerman MJ, Borggrefe M, Corrado D, Guo J, et al. J-Wave syndromes expert consensus conference report: emerging concepts and gaps in knowledge. Heart Rhythm. 2016 Oct;13((10)):e295–324. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2016.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Priori SG, Wilde AA, Horie M, Cho Y, Behr ER, Berul C, et al. HRS/EHRA/APHRS expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of patients with inherited primary arrhythmia syndromes: document endorsed by HRS, EHRA, and APHRS in May 2013 and by ACCF, AHA, PACES, and AEPC in June 2013. Heart Rhythm. 2013 Dec;10((12)):1932–63. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sakhi R, Theuns DA, Szili-Torok T, Yap SC. Insertable cardiac monitors: current indications and devices. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2019 Jan;16((1)):45–55. doi: 10.1080/17434440.2018.1557046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boule S, Kouakam C, Brigadeau F. Very prolonged episode of self-terminating ventricular fibrillation in a patient with Brugada syndrome. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29((12)):e1741–1743. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamilton G, O'Donnell D, Han HC. Brugada syndrome and undifferentiated syncope: use of an implantable loop recorder to document causation. Med J Aust. 2018 Aug;209((3)):113–4. doi: 10.5694/mja17.01117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Champagne J, Philippon F, Gilbert M, Molin F, Blier L, Nault I, et al. The Brugada syndrome in Canada: a unique French-Canadian experience. Can J Cardiol. 2007;23(Suppl B):71B–75B. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(07)71014-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data