Abstract

Introduction

Roxadustat is an oral hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor approved for the treatment of anemia in Japan for patients with dialysis-dependent (DD) chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Objective

Multicenter, randomized, open-label, noncomparative, phase 3 study to evaluate roxadustat for anemia of non-dialysis-dependent (NDD) CKD in Japan.

Methods

Erythropoiesis stimulating agent (ESA)-naïve NDD-CKD patients were randomized to roxadustat (initial dose, 50 or 70 mg 3 times weekly), titrated to maintain hemoglobin (Hb) within 10.0–12.0 g/dL, for ≤24 weeks. Patients with either transferrin saturation of ≥5% or serum ferritin of ≥30 ng/mL during the screening period were eligible. Endpoints included response rate (proportion of patients achieving Hb ≥10.0 or ≥10.5 g/dL and Hb increase ≥1.0 g/dL from baseline) at end of treatment; average Hb (weeks 18–24); change of average Hb from baseline to weeks 18–24; maintenance rate (proportion of patients achieving Hb 10.0–12.0 g/dL at weeks 18–24); rate of rise (RoR) of Hb from weeks 0–4, discontinuation, or dose adjustment. Adverse events were monitored throughout the study.

Results

Of 135 patients who provided informed consent, 100 were randomized and 99 received roxadustat (50 mg, n = 49; 70 mg, n = 50). The mean (SD) dose of roxadustat per intake at week 22 was 36.3 (22.7) mg in the roxadustat 50 mg group and 36.8 (16.0) mg in the roxadustat 70 mg group. Prior medications included oral iron therapy (20.2%) and intravenous iron therapy (1.0%). Overall response rate (95% CI) was 97.0% (91.4, 99.4; Hb ≥10.0 g/dL) and 94.9% (88.6, 98.3; Hb ≥10.5 g/dL). Mean (SD) Hb (weeks 18–24) was 11.17 (0.62) g/dL. Mean (SD) change of Hb from baseline (weeks 18–24) was 1.34 (0.86) g/dL. Maintenance rate (95% CI) was 88.8% (80.3, 94.5) among patients with ≥1 Hb measurement during weeks 18–24. Mean (SD) RoR of Hb was 0.291 (0.197) g/dL/week (50 mg) and 0.373 (0.235) g/dL/week (70 mg). Nasopharyngitis and hypertension were the most common adverse events.

Conclusion

Roxadustat increased and maintained Hb in ESA-naïve, partially iron-depleted NDD-CKD patients with anemia.

Keywords: Roxadustat, Anemia, Chronic kidney disease, Non-dialysis-dependent patients, Erythropoiesis-stimulating agent naïve patients

Introduction

Anemia is a common complication of chronic kidney disease (CKD) mainly associated with reduced synthesis of erythropoietin by the malfunctioning kidneys and iron deficiency, among other factors [1]. Erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) and iron are the standard therapy for anemia of CKD and, although generally effective, safety concerns in patients with cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular comorbidities have led healthcare professionals to adopt lower hemoglobin (Hb) targets when treating patients with ESAs [2, 3]. Moreover, while rates of hyporesponsiveness may vary based on the definition being used, roughly 10% of patients do not adequately respond to ESAs and require higher doses to achieve target Hb levels [4, 5]. ESAs are administered by injection, which may require a hospital visit, thereby acting as a potential obstacle for patients who are non-dialysis-dependent (NDD) and would not otherwise require frequent medical visits.

Roxadustat (ASP1517, FG-4592, AZD9941) is an oral hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor (HIF-PHI) that inhibits HIF prolyl-4-hydroxylase domains 1, 2, and 3 and promotes erythropoiesis by increasing endogenous erythropoietin, improving iron regulation, and reducing hepcidin [6, 7]. In a state of normal cellular oxygen levels, HIF prolyl hydroxylase enzymes are active and degrade HIF-α subunits. During hypoxic conditions, such as those experienced at high altitudes, the activity of these enzymes is suppressed, allowing HIF-α and HIF-β to dimerize and accumulate, which results in increased erythropoiesis and transferrin receptor expression and improved iron metabolism and absorption [8].

Roxadustat has previously demonstrated efficacy and tolerability in phase 2 studies in patients with dialysis-dependent (DD) [9, 10, 11] and NDD [10, 12, 13, 14] anemia of CKD. Phase 3 studies conducted in China [15, 16] and Japan [17] have demonstrated roxadustat's efficacy and safety in both DD-CKD and NDD-CKD patients, and roxadustat has recently been approved in China in DD and NDD patients and in Japan in DD patients. Development is ongoing in Europe, Japan (NDD only), the USA, and other countries in DD and NDD patients [15, 16, 17]. This study investigated the efficacy and safety of oral roxadustat administered at 2 different initial doses and titrated to achieve and maintain target Hb levels in Japanese ESA-naïve NDD-CKD patients with renal anemia.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This was a multicenter, randomized, open-label, noncomparative, phase 3 study conducted at 38 sites in Japan between January 2017 and August 2018. Prescreening assessments were performed to verify that patients satisfied all inclusion/exclusion criteria and were followed by screening assessments 1–10 weeks later. Patients were randomized to oral roxadustat at an initial dose of 50 or 70 mg 3 times a week (TIW) for up to 24 weeks. Because patients' body weight tends to fall within a narrow range in Japan, initial dosing is generally not based on weight, in contrast to the USA and Europe. Therefore, the initial doses of roxadustat used in this study were fixed at 50 or 70 mg, independent of body weight [14]. This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practice, the International Conference on Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use guidelines, and applicable laws and regulations. The protocol was approved by each Institutional Review Board, and all subjects provided written informed consent.

Study Population

Patients were aged ≥20 years with NDD-CKD and were ESA-naïve. Patients must have had (1) an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of ≤89 mL/min/1.73 m2; (2) the mean of the two most recent Hb levels (measured within an interval of at least 1 week) <10.5 g/dL with the absolute difference between the 2 measurements ≤1.3 g/dL; and (3) either transferrin saturation (TSAT) ≥5% or serum ferritin ≥30 ng/mL during the screening period. Patients were excluded if they had received ESAs within 6 weeks before prescreening. A full list of eligibility criteria is reported in the online suppl. Methods; for all online suppl. material, see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000508100.

Study Drug Administration

Oral roxadustat was self-administered as 20, 50, and 100 mg tablets TIW at 2- or 3-day intervals (e.g., Monday-Wednesday-Friday or Tuesday-Thursday-Saturday), as directed by the investigator. Eligible patients were randomized to either an initial dose of 50 or 70 mg roxadustat by the web registration system (EPS Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Dynamic allocation was conducted using a biased-coin minimization approach with study site, body weight just before registration, mean of the 2 most recent Hb levels, and eGFR at prescreening as allocation factors. To maintain Hb levels between 10.0 and 12.0 g/dL, adjustments of the doses of roxadustat were made at every scheduled visit starting from week 4 and were conducted in accordance with the dose-adjustment criteria (online suppl. Tables 1 and 2). The maximum dose of roxadustat was not to exceed 3 mg/kg or 300 mg, whichever was lower, and any adjusted dose had to be maintained for at least 4 weeks before further adjustment. Any phosphate binders were to be dosed at least 1 h before or after roxadustat. Concomitant intravenous iron was allowed only to maintain TSAT ≥5% and/or serum ferritin ≥30 ng/mL when TSAT was <5% or ferritin was <30 ng/mL; oral iron could be used without specific conditions. The use of statins was recommended at doses not exceeding the indicated maximum doses.

Study Outcomes

Efficacy endpoints included (1) response rate from baseline to end of treatment (EoT; proportion of patients who achieved Hb ≥10.0 g/dL or Hb ≥10.5 g/dL and an increase of Hb from baseline of ≥1.0 g/dL); (2) change of average Hb levels from baseline to weeks 18–24; (3) maintenance rate of target Hb level (proportion of patients who achieved the average Hb level of 10.0–12.0 g/dL at weeks 18–24); (4) rate of rise (RoR) in Hb levels (g/dL/week) from week 0 to week 4, discontinuation, or dose adjustment − whichever occurs first; (5) proportion of measurement points that met the target Hb level of 10.0–12.0 g/dL after achievement of Hb 10.0 g/dL in each patient; (6) proportion of patients who achieved, and time to achieve, an Hb level of 10.0 g/dL; (7) proportion of patients who achieved, and time to achieve, an Hb level of 10.5 g/dL; and (8) levels of hematocrit (Ht), iron, ferritin, transferrin, total iron binding capacity (TIBC), soluble transferrin receptor (sTfR), TSAT, and reticulocyte hemoglobin content (CHr), measured at baseline, week 2, week 4, week 6, every 4 weeks thereafter, and at study discontinuation. Treatment compliance was determined by the number of prescribed and returned/lost tablets as recorded in patient diaries. Mean levels of hepcidin were measured as an exploratory endpoint at baseline, week 4, week 12, week 24, and at study discontinuation. Safety was assessed by monitoring treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs), laboratory assessments, vital signs, and 12-lead electrocardiogram.

Statistical Methods

For practical purposes, a sample size of 100 (n = 50, roxadustat 50 mg; n = 50, roxadustat 70 mg) patients was planned. Analyses of efficacy endpoints were performed on the full analysis set (FAS), which comprised all patients who received ≥1 dose of roxadustat and who had ≥1 efficacy measurement during the treatment period. Analysis of safety and compliance was conducted on the safety analysis set (SAF), which comprised all patients who received ≥1 dose of roxadustat. Demographic and baseline characteristics, as well as efficacy and exploratory data, are presented using summary statistics.

Results

Subject Disposition

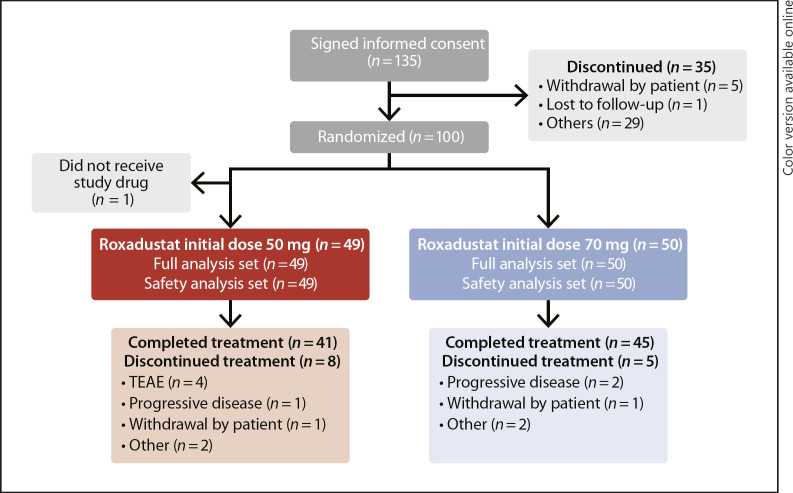

Of 135 patients who provided informed consent, 35 were screen failures, 100 were randomized, and 99 received roxadustat (initial roxadustat 50 mg, n = 49; initial roxadustat 70 mg, n = 50) and were included in the FAS and SAF. A total of 86 (86.0%) patients completed the study, and 14 (14.0%) patients discontinued due to TEAE (n = 4, [4.0%]), progressive disease (n = 3, [3.0%]), withdrawal by patient (n = 2 [2.0%]), and other reasons (n = 5 [5.0%]) (Fig. 1). Patient demographics and baseline variables were similar in the 2 treatment groups (Tables 1 and 2).

Fig. 1.

Disposition of patients. Reasons for discontinuation before randomization: n = 17, did not meet Hb criteria; n = 6, considered ineligible by the investigator; n = 5, withdrawal by patient; n = 3, positive for hepatitis B virus surface antigen or hepatitis C virus antibody at prescreening or positive for human immunodeficiency virus in a past test; n = 1, concurrent retinal neovascular lesion or macular edema requiring treatment; n = 1, treated with ESA, protein anabolic hormone, testosterone enanthate, or mepitiostane within 6 weeks before prescreening; n = 1, history of hospitalization for treatment of stroke, myocardial infarction, or pulmonary embolism within 12 weeks before prescreening; n = 1, lost to follow-up. FAS, full analysis set; SAF, safety analysis set; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and baseline efficacy variables (full analysis set)

| Parameter | Roxadustat 50 mg (n = 49) | Roxadustat 70 mg (n = 50) | All patients (n = 99) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 27 (55.1) | 29 (58.0) | 56 (56.6) |

| Female | 22 (44.9) | 21 (42.0) | 43 (43.4) |

| Age, years | |||

| Mean (SD) | 69.4 (11.5) | 68.2 (11.3) | 68.8 (11.3) |

| Median | 71.0 | 70.0 | 70.0 |

| Min, max | 27, 87 | 32, 91 | 27, 91 |

| Age, n (%) | |||

| <65 years | 14 (28.6) | 16 (32.0) | 30 (30.3) |

| ≥65 years | 35 (71.4) | 34 (68.0) | 69 (69.7) |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2), n (%) | |||

| <15 | 22 (44.9) | 22 (44.0) | 44 (44.4) |

| ≥15 | 27 (55.1) | 28 (56.0) | 55 (55.6) |

| Weight, kg | |||

| Mean (SD) | 60.25 (10.28) | 61.69 (13.43) | 60.97 (11.94) |

| Median | 59.30 | 59.45 | 59.40 |

| Min, max | 40.2, 97.4 | 41.2, 108.5 | 40.2, 108.5 |

| Height, cm | |||

| Mean (SD) | 159.38 (9.22) | 159.74 (8.66) | 159.56 (8.90) |

| Median | 161.30 | 159.40 | 160.60 |

| Min, max | 140.4, 176.1 | 142.0, 180.0 | 140.4, 180.0 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 23.78 (4.06) | 24.09 (4.36) | 23.94 (4.20) |

| Median | 23.26 | 23.66 | 23.47 |

| Min, max | 18.8, 36.3 | 17.2, 39.7 | 17.2, 39.7 |

| Duration of anemia in CKD, months | |||

| n | 38 | 42 | 80 |

| Mean (SD) | 34.49 (49.82) | 25.69 (35.06) | 29.87 (42.67) |

| Median | 16.40 | 11.00 | 14.35 |

| Min, max | 1.7, 276.3 | 0.5, 169.2 | 0.5, 276.3 |

| Primary disease of CKD, n (%) | |||

| Chronic glomerulonephritis | 13 (26.5) | 12 (24.0) | 25 (25.3) |

| Diabetic nephropathy | 12 (24.5) | 16 (32.0) | 28 (28.3) |

| Polycystic kidney disease | 4 (8.2) | 3 (6.0) | 7 (7.1) |

| Nephrosclerosis | 18 (36.7) | 15 (30.0) | 33 (33.3) |

| Others | 2 (4.1) | 4 (8.0) | 6 (6.1) |

| Hemoglobina, g/dL | |||

| Mean (SD) | 9.77 (0.62) | 9.87 (0.51) | 9.82 (0.57) |

| Median | 9.90 | 10.00 | 9.90 |

| Min, max | 7.6, 10.6 | 8.4, 10.7 | 7.6, 10.7 |

| Ironb, μmol/L | |||

| Mean (SD) | 13.5 (3.9) | 13.1 (4.3) | 13.3 (4.1) |

| Median | 13.0 | 13.0 | 13.0 |

| Min, max | 6, 22 | 5, 27 | 5, 27 |

| Ferritin, ng/mL | |||

| Mean (SD) | 113.68 (90.20) | 113.90 (84.45) | 113.79 (86.89) |

| Median | 80.30 | 101.60 | 87.70 |

| Min, max | 10.1, 473.0 | 11.7, 421.0 | 10.1, 473.0 |

| TSAT, % | |||

| Mean (SD) | 28.85 (8.41) | 26.99 (7.97) | 27.91 (8.2) |

| Median | 28.70 | 27.65 | 28.30 |

| Min, max | 11.0, 44.4 | 7.5, 49.5 | 7.5, 49.5 |

| Iron repletion, % | |||

| Ferritin ≥100 ng/mL and TSAT ≥20% | 20 (40.8) | 23 (46.0) | 43 (43.4) |

| Ferritin <100 ng/mL and TSAT ≥20% | 21 (42.9) | 18 (36.0) | 39 (39.4) |

| Ferritin ≥100 ng/mL and TSAT <20% | 2 (4.1) | 2 (4.0) | 4 (4.0) |

| Ferritin <100 ng/mL and TSAT <20% | 6 (12.2) | 7 (14.0) | 13 (13.1) |

| Reticulocyte Hb, pg | |||

| Mean (SD) | 33.93 (1.52) | 33.87 (1.93) | 33.90 (1.73) |

| Median | 33.70 | 34.10 | 33.90 |

| Min, max | 30.6, 36.7 | 29.2, 37.8 | 29.2, 37.8 |

| Transferrin, g/L | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2.009 (0.309) | 2.071 (0.297) | 2.040 (0.303) |

| Median | 2.010 | 2.035 | 2.010 |

| Min, max | 1.36, 2.78 | 1.57, 2.74 | 1.36, 2.78 |

| Hs-CRP, nmol/Lcd | |||

| Mean (SD) | 15.894 (32.158) | 26.647 (108.543) | 21.324 (80.165) |

| Median | 4.490 | 4.385 | 4.430 |

| Min, max | 0.93, 159.05 | 0.48, 763.82 | 0.48, 763.82 |

CKD, chronic kidney disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; Hb, hemoglobin; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; TSAT, transferrin saturation.

Baseline Hb was defined as the mean of 3 Hb values: 2 latest Hb values prior to registration and 1 Hb value at week 0.

Standard reference values for iron: male, lower level of normal range = 10 μmol/L; upper level of normal range = 36 μmol/L; female, lower level of normal range = 9 μmol/L; upper level of normal range = 28 μmol/L.

Upper level of normal = 28.57 nmol/L.

hs-CRP was summarized using the safety analysis set.

Table 2.

Prior and concomitant medications (safety analysis set)

| Parameter | Roxadustat 50 mg (n = 49) | Roxadustat 70 mg (n = 50) | All patients (n = 99) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prior oral iron use | 10 (20.4) | 10 (20.0) | 20 (20.2) |

| Concomitant oral iron use | 16 (32.7) | 14 (28.0) | 30 (30.3) |

| Prior IV iron use | 1 (2.0) | 0 | 1 (1.0) |

| Concomitant IV iron use | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Prior statin use | 28 (57.1) | 26 (52.0) | 54 (54.5) |

| Concomitant statin use | 28 (57.1) | 27 (54.0) | 55 (55.6) |

| Prior phosphate binder use | 3 (6.1) | 1 (2.0) | 4 (4.0) |

| Concomitant phosphate binder use | 7 (14.3) | 7 (14.0) | 14 (14.1) |

Data are presented as n (%). IV, intravenous.

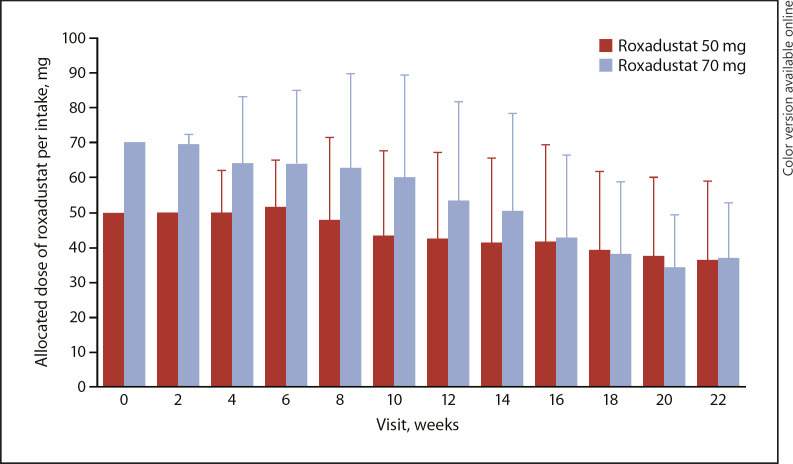

Roxadustat Compliance and Exposure

The mean (SD) overall treatment compliance was 98.83% (2.71). The mean (SD) duration of roxadustat exposure was 147.3 (45.3) days in the roxadustat 50 mg group and 145.5 (42.8) days in the roxadustat 70 mg group. The mean (SD) dose of roxadustat per intake at week 22 was 36.3 (22.7) mg in the roxadustat 50 mg group and 36.8 (16.0) mg in the roxadustat 70 mg group (Fig. 2 and online suppl. Fig. 1). The highest dose of roxadustat per intake that was used overall was 2.7 mg/kg in the 70 mg roxadustat group. The overall mean (SD) number of changes in roxadustat dose per patient was the same in both roxadustat groups (2.7 [1.2]); the mean (SD) number of roxadustat dose increases per patient was 0.9 (0.9) and 0.6 (0.7) in the roxadustat 50 and 70 mg groups, respectively; and the mean (SD) number of roxadustat dose decreases was 1.8 (0.9) and 2.1 (1.0) in the roxadustat 50 and 70 mg groups, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Mean (SD) allocated dose of roxadustat per intake (safety analysis set).

Efficacy Outcomes

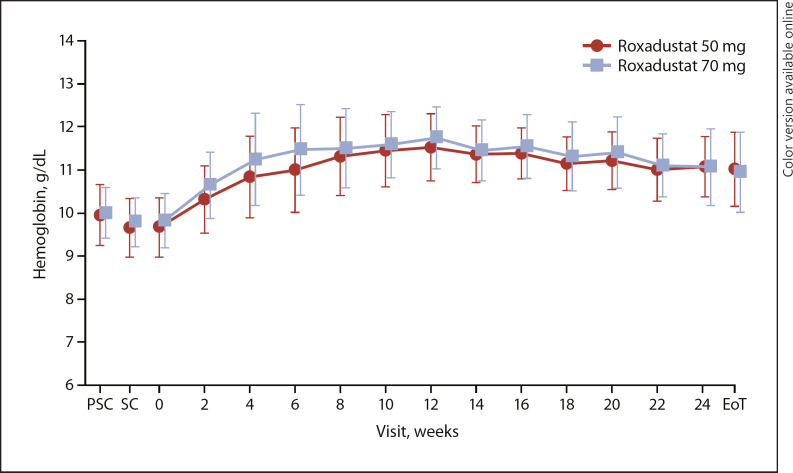

The response rate (proportion of patients who achieved Hb ≥10.0 g/dL and an increase of Hb from baseline of ≥1.0 g/dL) from baseline to EoT was 97.0% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 91.4, 99.4; 93.9% [95% CI: 83.1, 98.7], roxadustat 50 mg; 100.0% [95% CI: 92.9, 100.0], roxadustat 70 mg). The response rate (proportion of patients who achieved Hb ≥10.5 g/dL and an increase of Hb from baseline of ≥1.0 g/dL) from baseline to EoT was 94.9% (95% CI: 88.6, 98.3; 91.8% [95% CI: 80.4, 97.7], roxadustat 50 mg; 98.0% [95% CI: 89.4, 99.9], roxadustat 70 mg). The mean level of Hb increased from week 0 to week 12 and then remained stable within the target range throughout the EoT (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Mean (SD) hemoglobin levels (full analysis set). EoT, end of treatment; PSC, prescreening; SC, screening.

The mean (SD) Hb level of weeks 18–24 was 11.17 (0.62) g/dL (11.12 [0.57] g/dL, roxadustat 50 mg; 11.23 [0.67] g/dL, roxadustat 70 mg). The mean (SD) change of Hb levels from baseline to weeks 18–24 was 1.34 (0.86) g/dL (1.39 [0.93] g/dL, roxadustat 50 mg; 1.30 [0.80] g/dL, roxadustat 70 mg). The maintenance rate (95% CI) of target Hb level for weeks 18–24 was 79.8% (70.5, 87.2) for all patients in the FAS and 88.8% (80.3, 94.5) among patients with ≥1 Hb measurement during weeks 18–24 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Maintenance rate of target Hb level for weeks 18–24 (full analysis set)

| Parameter | Roxadustat 50 mg (n = 49) | Roxadustat 70 mg (n = 50) | All patients (n = 99) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maintenance rate for all patients in the full analysis set | |||

| Maintenance rate, n (%) | 39 (79.6) | 40 (80.0) | 79 (79.8) |

| 95% CI, % | 65.7, 89.8 | 66.3, 90.0 | 70.5, 87.2 |

| Maintenance rate for patients who had at least 1 Hb measurement during weeks 18–24 | |||

| N | 44 | 45 | 89 |

| Maintenance rate, n (%) | 39 (88.6) | 40 (88.9) | 79 (88.8) |

| 95% CI, % | 75.4, 96.2 | 75.9, 96.3 | 80.3, 94.5 |

Target Hb level, 10.0–12.0 g/dL. CI, confidence interval; Hb, hemoglobin.

The mean (SD) RoR in Hb levels from week 0 to week 4, discontinuation, or dose adjustment was 0.332 (0.220) g/dL/week (0.291 [0.197] g/dL/week, roxadustat 50 mg; 0.373 [0.235] g/dL/week, roxadustat 70 mg). The proportion of patients with rate of Hb rise >0.5 g/dL/week was 12.2 and 18.0% in the roxadustat 50 and 70 mg groups, respectively. The proportion of patients with rate of Hb rise ≤0.1 g/dL/week was 14.3 and 12.0% in the roxadustat 50 and 70 mg groups, respectively. The mean (SD) proportion of Hb measurements that met target levels after achievement of Hb of 10.0 g/dL in each patient was 79.52% (22.72) (84.55% [23.25], roxadustat 50 mg; 74.60% [21.29], roxadustat 70 mg). The proportion of patients who achieved the Hb level of 10.0 g/dL increased from week 2 to week 12 and was 89.9% (91.8%, roxadustat 50 mg; 88.0%, roxadustat 70 mg) at EoT. The median time to the first achievement of the Hb level of 10.0 g/dL was 15.0 days for both the roxadustat 50 and 70 mg groups. The proportion of patients who achieved the Hb level of 10.5 g/dL increased from week 2 to week 12 and was 72.7% (79.6%, roxadustat 50 mg; 66.0%, roxadustat 70 mg) at EoT. The median (95% CI) time to the first achievement of the Hb level of 10.5 g/dL was 15.0 (15.0, 29.0) days (29.0 [15.0, 29.0] days, roxadustat 50 mg; 15.0 [15.0, 16.0] days, roxadustat 70 mg).

No remarkable changes in iron status were observed between groups in this largely iron-replete population, when comparing baseline and EoT values. The mean iron levels remained stable throughout the study in both roxadustat groups. An increase was observed in the mean levels of transferrin, TIBC, and sTfR during the first 4 weeks, followed by a slight decrease through EoT, whereas the mean levels of TSAT decreased from week 0 through week 4 and then increased to baseline. The mean ferritin levels decreased from week 0 through week 8 and then slightly increased through EoT (Table 4 and online suppl. Figs. 2345678). The mean hematocrit values increased from week 0 to week 12 and then slightly decreased through EoT. The CHr levels remained stable throughout the study.

Table 4.

Mean and median levels of iron parameters and hepcidin (full analysis set)

| Parameter | Week 0 | EoT | Change from baseline to EoT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Roxadustat 50 mg (n = 49) | |||

| Iron, μmol/L | 13.5 (3.9), 13.0 | 15.4 (6.0), 16.0 | 2.0 (5.9), 3.0 |

| Ferritin, ng/mL | 113.68 (90.20), 80.30 | 85.17 (73.62), 66.30 | −28.51 (41.15), −17.00 |

| Transferrin, g/L | 2.009 (0.309), 2.010 | 2.353 (0.453), 2.300 | 0.344 (0.324), 0.300 |

| TSAT, % | 28.85 (8.41), 28.70 | 28.84 (11.21), 30.60 | −0.01 (11.43), 1.50 |

| Reticulocyte Hb, pg | 33.93 (1.52), 33.70 | 33.64 (2.08), 33.70 | −0.28 (2.27), 0.00 |

| Hepcidin, ng/mL | 23.463 (19.347), 19.400 | 18.144 (16.540), 13.800 | −5.319 (19.746), −5.490 |

| TIBC, μmol/L | 47.3 (6.7), 48.0 | 54.6 (9.7), 53.0 | 7.3 (7.2), 7.0 |

| sTfR, nmol/L | 20.59 (6.19), 18.90 | 25.74 (9.94), 23.70 | 5.15 (8.14), 3.90 |

| Roxadustat 70 mg (n = 50) | |||

| Iron, μmol/L | 13.1 (4.3), 13.0 | 15.2 (4.4), 15.0 | 2.1 (5.1), 2.0 |

| Ferritin, ng/mL | 113.90 (84.45), 101.60 | 87.61 (53.67), 78.00 | −26.29 (51.36), −24.15 |

| Transferrin, g/L | 2.071 (0.297), 2.035 | 2.320 (0.423), 2.275 | 0.249 (0.333), 0.205 |

| TSAT, % | 26.99 (7.97), 27.65 | 28.98 (8.44), 28.50 | 1.99 (9.45), 1.15 |

| Reticulocyte Hb, pg | 33.87 (1.93), 34.10 | 34.33 (1.84), 34.60 | 0.46 (1.64), 0.30 |

| Hepcidin, ng/mL | 24.494 (15.991), 21.700 | 18.335 (18.482), 13.400 | −6.159 (17.231), −6.855 |

| TIBC, μmol/L | 48.8 (6.5), 49.0 | 53.3 (8.7), 52.0 | 4.5 (6.9), 3.5 |

| sTfR, nmol/L | 18.89 (5.32), 17.75 | 20.93 (6.95), 18.85 | 2.04 (6.43), 1.50 |

| All patients (n = 99) | |||

| Iron, μmol/L | 13.3 (4.1), 13.0 | 15.3 (5.2), 15.0 | 2.0 (5.5), 2.0 |

| Ferritin, ng/mL | 113.79 (86.89), 87.70 | 86.40 (64.00), 69.50 | −27.39 (46.36), −21.20 |

| Transferrin, g/L | 2.040 (0.303), 2.010 | 2.337 (0.436), 2.290 | 0.296 (0.330), 0.260 |

| TSAT, % | 27.91 (8.20), 28.30 | 28.91 (9.86), 29.70 | 1.00 (10.47), 1.30 |

| Reticulocyte Hb, pg | 33.90 (1.73), 33.90 | 33.99 (1.98), 34.20 | 0.09 (2.00), 0.20 |

| Hepcidin, ng/mL | 23.984 (17.648), 21.300 | 18.241 (17.458), 13.600 | −5.743 (18.428), −5.660 |

| TIBC, μmol/L | 48.1 (6.6), 48.0 | 54.0 (9.2), 53.0 | 5.9 (7.2), 5.0 |

| sTfR, nmol/L | 19.73 (5.80), 18.40 | 23.31 (8.85), 21.40 | 3.58 (7.45), 3.10 |

Data are presented as mean (SD), median. EoT, end of treatment; Hb, hemoglobin; sTfR, soluble transferrin receptor; TIBC, total iron binding capacity; TSAT, transferrin saturation.

Exploratory Outcome

In this population of NDD-CKD patients with predominately normal hepcidin levels, the mean (SD) levels of hepcidin (ng/mL) decreased by 5.319 (19.746) and 6.159 (17.231) in the 50 and 70 mg groups, respectively, between week 0 (23.463 [19.347] ng/mL, 50 mg; 24.494 [15.991] ng/mL, 70 mg) and EoT (18.144 [16.540] ng/mL, 50 mg; 18.335 [18.482] ng/mL, 70 mg). Hepcidin values were lowest at week 4 in both groups; following week 4, hepcidin values seemed to increase and stabilize until EoT (Table 4 and online suppl. Fig. 9).

Safety

The overall incidence of TEAEs was 62.6% (n = 62/99; 61.2% [n = 30/49], roxadustat 50 mg; 64.0% [n = 32/50], roxadustat 70 mg), and the incidence of serious TEAEs was 11.1% (n = 11/99; 10.2% [n = 5/49], roxadustat 50 mg; 12.0% [n = 6/50], roxadustat 70 mg). TEAEs leading to withdrawal of treatment occurred in 6.1% (6/99; 8.2% [n = 4/49], roxadustat 50 mg; 4.0% [n = 2/50], roxadustat 70 mg) of patients. These included peripheral edema, bile duct stone, hyperkalemia, metabolic acidosis, decreased appetite, rash, azotemia (n = 1 for all), and CKD (n = 2).

The most common TEAEs (≥5%) in all patients were nasopharyngitis (20.2% [n = 20/99]), hypertension (6.1% [n = 6/99]), diarrhea (5.1% [n = 5/99]), and hyperkalemia (5.1% [n = 5/99]). The proportion of patients with hypertension at baseline was balanced between groups (91.8% [n = 45/49], roxadustat 50 mg; 92.0% [n = 46/50], roxadustat 70 mg); across the 24 weeks of treatment, the incidence of treatment-emergent hypertension was not statistically significant between the roxadustat 70 mg (10.0% [n = 5/50]) group and the 50 mg (2.0% [n = 1/49]) group. No deaths occurred during the study (Table 5). No clinically significant changes were observed in clinical laboratory evaluations, 12-lead ECG, or vital signs.

Table 5.

Overview of treatment-emergent adverse events (safety analysis set)

| Roxadustat 50 mg (n = 49) |

Roxadustat 70 mg (n = 50) |

All patients (n = 99) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Any TEAEs | 30 (61.2) | 32 (64.0) | 62 (62.6) |

| Serious TEAEs | 5 (10.2) | 6 (12.0) | 11 (11.1) |

| Drug-related serious TEAEs | 2 (4.1) | 0 | 2 (2.0) |

| TEAEs leading to discontinuation | 4 (8.2) | 2 (4.0) | 6 (6.1) |

| TEAEs occurring in ≥5% of patients by MedDRA v19.0 system organ class and preferred term | |||

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 10 (20.4) | 7 (14.0) | 17 (17.2) |

| Diarrhea | 3 (6.1) | 2 (4.0) | 5 (5.1) |

| Infections and infestations | 15 (30.6) | 15 (30.0) | 30 (30.3) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 9 (18.4) | 11 (22.0) | 20 (20.2) |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 8 (16.3) | 5 (10.0) | 13 (13.1) |

| Hyperkalemia | 3 (6.1) | 2 (4.0) | 5 (5.1) |

| Vascular disorders | 2 (4.1) | 5 (10.0) | 7 (7.1) |

| Hypertension | 1 (2.0) | 5 (10.0) | 6 (6.1) |

Data are presented as n (%). TEAEs, treatment-emergent adverse events.

Discussion

The results of this study suggest that roxadustat with oral administration TIW is effective in increasing and maintaining Hb levels within the target range of 10.0–12.0 g/dL in anemic Japanese NDD-CKD patients who were ESAs-naïve, and no remarkable differences were observed between patients randomized to the initial dose of either 50 or 70 mg roxadustat. High response rates were observed at both Hb cutoffs (≥10.0 g/dL [97.0%, 95% CI: 91.4, 99.4] and ≥10.5 g/dL [94.9%, 95% CI: 88.6, 98.3]) and were slightly higher for the roxadustat 70 mg group. In both roxadustat dose groups, the Hb levels increased from week 0 to week 12 and then remained stable until EoT, with a mean (SD) Hb of 11.17 (0.62) g/dL at weeks 18–24. The overall mean (SD) change of Hb from baseline to weeks 18–24 was 1.34 (0.86) g/dL and was similar at both initial doses of roxadustat. The maintenance rate of target Hb level for weeks 18–24 (among patients with at least 1 Hb measurement during weeks 18–24) was 88.8% (95% CI: 80.3, 94.5) and was similar at both initial doses of roxadustat.

The Japanese Society for Dialysis Therapy recommends a rate of change of Hb not to exceed 0.5 g/dL/week because at higher rates increased cardiovascular risk cannot be excluded when managing anemia with ESAs [18, 19]. The overall mean (SD) RoR in Hb levels from week 0 to week 4, discontinuation, or dose adjustment was 0.332 (0.220) g/dL/week; a higher mean RoR was observed with an initial roxadustat dose of 70 mg than with 50 mg (0.373 g/dL/week vs. 0.291 g/dL/week). Moreover, a higher proportion of patients in the initial roxadustat 70 mg group had a RoR in Hb > 0.5 g/dL/week compared with the roxadustat 50 mg group (18.0 vs. 12.2%). Overall, 72.7% of patients achieved the Hb level of 10.5 g/dL by EoT with a higher percentage of patients in the initial roxadustat 50 mg group than in the 70 mg group (79.6 vs. 66.0%). However, the median time to achieve the Hb level of 10.5 g/dL for the first time was longer for the initial roxadustat 50 mg (29.0 days) group than for the 70 mg (15.0 days) group. Most iron parameters remained clinically stable throughout the treatment period in the presence of robust erythropoiesis and with no patients receiving intravenous iron. Ferritin levels decreased between week 0 and week 8 and then slightly increased through EoT. A decrease in the levels of hepcidin was also observed throughout the study. Overall, these findings confirm those of previous studies in ESA-naïve patients [17] (CL-0308) and patients converted from ESAs [17] (307 and 312) and suggest that treatment with roxadustat improves iron metabolism and mobilization.

In line with previous studies, roxadustat was generally well tolerated in NDD-CKD patients who were ESA-naïve [14, 17]. Common TEAEs were nasopharyngitis (20.2%), hypertension (6.1%), diarrhea (5.1%), and hyperkalemia (5.1%), and no deaths occurred throughout the study. No difference was observed between the 50 and 70 mg groups in the mean (SD) duration of roxadustat exposure (147.3 [45.3] days vs. 145.5 [42.8] days) and in the mean (SD) allocated dose of roxadustat per intake at week 22 (36.3 [22.7] mg vs. 36.8 [16.0] mg). Similarly, the mean (SD) number of changes in roxadustat dose per patient was 2.7 (1.2) in both groups, and treatment compliance was nearly 99%.

The efficacy results in this study are similar to those reported in previous phase 2 and phase 3 studies conducted in China, the USA, and Japan [10, 12, 13, 14]. A study conducted in the USA showed that the response rate (proportion of patients with Hb change from baseline ≥1 g/dL) after a 6-week treatment with 1.5 mg/kg roxadustat TIW in NDD-CKD patients was 91% and a Hb response was achieved in a median time of 14 days [12]. A Chinese study of roxadustat at doses comparable to those used in this study, and conducted on NDD-CKD patients who were ESA-naïve, showed a trend in Hb levels similar to that reported in this study, although the time to reach the Hb target was longer (6 weeks vs. 15 days) [10]. A Japanese phase 2 study of NDD-CKD patients who were ESA-naïve showed a similar response rate after a 24-week treatment with roxadustat 50 mg (81.5%) and 70 mg (100%). The same study reported RoR of Hb for roxadustat 50 mg (0.200 g/dL/week) and 70 mg (0.453 g/dL/week) that were comparable to those found in this study; however, the proportion of patients with Hb RoR exceeding 0.5 g/dL/week was higher for the roxadustat 70 mg group compared to those reported in this study (34.6 vs. 18.0%), but not for the roxadustat 50 mg group (3.7 vs. 12.2%) [14].

This study has some limitations. The lack of a placebo or a comparator group may limit the interpretation of the efficacy and safety findings. Moreover, due to the open-label design, the study may have been subject to bias. Since patients enrolled in this study were exclusively Japanese, the findings can provide practical directions for physicians in Japan but might not be generally applicable to patients of other ethnicities or geographic locations. Overall, this study showed that treatment with oral roxadustat TIW initiated at doses of 50 mg or 70 mg was effective in maintaining Hb within target levels and was generally well tolerated in Japanese NDD-CKD patients with anemia who were ESA-naïve and partially iron-depleted, suggesting that either dose of roxadustat may be appropriate for initiation of therapy in NDD-CKD patients with anemia.

Statement of Ethics

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practice, the International Conference on Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use guidelines, and applicable laws and regulations. The protocol was approved by each Institutional Review Board, and all subjects provided written informed consent.

Disclosure Statement

Tadao Akizawa reports personal fees from Astellas during the conduct of the study and personal fees from Bayer Yakuhin, Ltd.; Japan Tobacco, Inc.; GlaxoSmithKline; Kissei Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; Fuso Pharmaceutical Industries, Ltd.; Nipro Corporation; Kyowa Kirin; Torii Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; Sanwa Chemical; and Otsuka outside of the submitted work. Michael Reusch is an employee of Astellas Pharma Europe B.V. Tetsuro Otsuka and Yusuke Yamaguchi are employees of Astellas Pharma, Inc., and Tetsuro Otsuka owns stock at Astellas Pharma, Inc.

Funding Sources

This study was funded by Astellas Pharma, Inc. Medical writing and editorial support for this article were also funded by Astellas Pharma, Inc.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: T.A. and T.O.; acquisition of data: T.O.; analysis and interpretation of the data: T.A., Y.Y., and T.O.; drafting of the article: T.A., Y.Y., T.O., and M.R.; critical revision of the article: T.A., Y.Y., T.O., and M.R.; final approval of the article: T.A., Y.Y., T.O., and M.R.

Data Sharing Statement

Researchers may request access to anonymized participant level data, trial level data, and protocols from Astellas sponsored clinical trials at www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com. For the Astellas criteria on data sharing, see https://clinicalstudydatarequest.com/Study-Sponsors/Study-Sponsors-Astellas.aspx.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Acknowledgements

Roxadustat is being developed by FibroGen, AstraZeneca, and Astellas. Financial support for this article, including writing and editorial assistance by Patrick Tucker, PhD, and Elizabeth Hermans, PhD, of OPEN Health Medical Communications (Chicago, IL, USA), was provided by Astellas Pharma, Inc. We would like to thank the investigators associated with this trial: Takayuki Fujii (Seirei Sakura Citizen Hospital), Yuichiro Makita (Koshigaya City Hospital), Toshifumi Sakaguchi (Rinku General Medical Center), Ryoichi Andou (Japanese Red Cross Musashino Hospital), Yasuhiro Onodera (Sapporo Tokushukai Hospital), Takayasu Otake (Shonan Kamakura General Hospital), Yosuke Saka (Kasugai Municipal Hospital), Chikako Nose (Toyama Prefectural Central Hospital), Shigeki Ando (Tohoku Medical and Pharmaceutical University Wakabayashi Hospital), Taihei Yanagida (Steel Memorial Yawata Hospital), Hideo Araki (Fukui Prefectural Hospital), Kazuhiko Funabiki (Juntendo University Juntendo Tokyo Koto Geriatric Medical Center), Hajime Fujisawa (Yokohama City Minato Red Cross Hospital), Hiroaki Kobayashi (Ibaraki Prefectural Central Hospital), Teruki Kondo (Nagano Chuo Hospital), Yoshitaka Maeda (JA Toride Medical Center), Taishi Yamakawa (Toyohashi Municipal Hospital), Tetsuro Takeda (Dokkyo Medical University Saitama Medical Center), Hiroya Takeoka (Hyogo Prefectural Amagasaki General Medical Center), Tadashi Iitsuka (Ibaraki Seinan Medical Center Hospital), Kenjiro Kimura (Japan Community Healthcare Organization Tokyo Takanawa Hospital), Tatsushi Sugiura (Seiwa Clinic), Shigeru Miyazaki (Shinrakuen Hospital), Yasushi Asano (Japanese Red Cross Koga Hospital), Kenichiro Kojima (Ageo Central General Hospital), Jun Soma (Iwate Prefectural Central Hospital), Yukio Yokoyama (Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital and Atomic-Bomb Survivors Hospital), Masaru Nakayama (National Hospital Organization Kyushu Medical Center), Nobuyoshi Nasu (National Hospital Organization Oita Medical Center), Kiyoki Kitagawa (National Hospital Organization Kanazawa Medical Center), Takashi Sekikawa (Matsuyama Shimin Hospital), Takashi Kihara (Hiroshima City Hiroshima Citizens Hospital), Takayuki Toda (Tsuchiura Kyodo General Hospital), and Kei Matsushita (National Hospital Organization Yokohama Medical Center).

References

- 1.Fishbane S, Spinowitz B. Update on anemia in ESRD and earlier stages of CKD: core curriculum 2018. Am J Kidney Dis. 2018;71((3)):423–35. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akizawa T, Okumura H, Alexandre AF, Fukushima A, Kiyabu G, Dorey J. Burden of anemia in chronic kidney disease patients in Japan: a literature review. Ther Apher Dial. 2018;22((5)):444–56. doi: 10.1111/1744-9987.12712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Del Vecchio L, Locatelli F. An overview on safety issues related to erythropoiesis-stimulating agents for the treatment of anaemia in patients with chronic kidney disease. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2016;15((8)):1021–30. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2016.1182494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson DW, Pollock CA, Macdougall IC. Erythropoiesis-stimulating agent hyporesponsiveness. Nephrology (Carlton) 2007;12((4)):321–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2007.00810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Locatelli F, Del Vecchio L. Will there still be a role for the originator erythropoiesis-simulating agents after the biosimilars and the hypoxia-inducible factor stabilizers approval? Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2018;27((5)):339–44. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Becker K, Saad M. A new approach to the management of anemia in CKD patients: a review on roxadustat. Adv Ther. 2017;34((4)):848–53. doi: 10.1007/s12325-017-0508-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Locatelli F, Fishbane S, Block GA, Macdougall IC. Targeting hypoxia-inducible factors for the treatment of anemia in chronic kidney disease patients. Am J Nephrol. 2017;45((3)):187–99. doi: 10.1159/000455166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta N, Wish JB. Hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors: a potential new treatment for anemia in patients with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;69((6)):815–26. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Besarab A, Chernyavskaya E, Motylev I, Shutov E, Kumbar LM, Gurevich K, et al. Roxadustat (FG-4592): correction of anemia in incident dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27((4)):1225–33. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015030241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen N, Qian J, Chen J, Yu X, Mei C, Hao C, et al. Phase 2 studies of oral hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor FG-4592 for treatment of anemia in China. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32((8)):1373–86. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfx011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Provenzano R, Besarab A, Wright S, Dua S, Zeig S, Nguyen P, et al. Roxadustat (FG-4592) versus epoetin alfa for anemia in patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis: a phase 2, randomized, 6- to 19-week, open-label, active-comparator, dose-ranging, safety, and exploratory efficacy study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;67((6)):912–24. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Besarab A, Provenzano R, Hertel J, Zabaneh R, Klaus SJ, Lee T, et al. Randomized placebo-controlled dose-ranging and pharmacodynamics study of roxadustat (FG-4592) to treat anemia in nondialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease (NDD-CKD) patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30((10)):1665–73. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfv302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Provenzano R, Besarab A, Sun CH, Diamond SA, Durham JH, Cangiano JL, et al. Oral hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor roxadustat (FG-4592) for the treatment of anemia in patients with CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11((6)):982–91. doi: 10.2215/CJN.06890615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akizawa T, Iwasaki M, Otsuka T, Reusch M, Misumi T. Roxadustat treatment of chronic kidney disease-associated anemia in Japanese patients not on dialysis: a phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Adv Ther. 2019;36((6)):1438–54. doi: 10.1007/s12325-019-00943-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen N, Hao C, Liu BC, Lin H, Wang C, Xing C, et al. Roxadustat treatment for anemia in patients undergoing long-term dialysis. N Engl J Med. 2019;381((11)):1011–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1901713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen N, Hao C, Peng X, Lin H, Yin A, Hao L, et al. Roxadustat for anemia in patients with kidney disease not receiving dialysis. N Engl J Med. 2019;381((11)):1001–10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1813599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akizawa T, Otsuka T, Reusch M, Ueno M. Intermittent oral dosing of roxadustat in peritoneal dialysis chronic kidney disease patients with anemia: a randomized, phase 3, multicenter, open-label study. Ther Apher Dial. 2019;24((2)):115–25. doi: 10.1111/1744-9987.12888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsubakihara Y, Nishi S, Akiba T, Hirakata H, Iseki K, Kubota M, et al. 2008 Japanese Society for Dialysis Therapy: guidelines for renal anemia in chronic kidney disease. Ther Apher Dial. 2010;14((3)):240–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-9987.2010.00836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh AK. The FDA's perspective on the risk for rapid rise in hemoglobin in treating CKD anemia: quo vadis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5((4)):553–6. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00490110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data