Abstract

Objective

We investigated the feasibility and safety of fertility-sparing surgery (FSS) in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) with dense adhesions.

Methods

Patients were divided into cases with and without dense adhesions in this retrospective study.

Results

Of the 95 eligible patients, 29 patients had dense adhesions. Mean age, proportion of staging procedure, distribution of histologic type, and co-presence of endometriosis were different (p=0.003, 0.033, 0.011, and 0.011, respectively). The median follow-up period was 57.8 (0.4–230.0) months. There were no differences in the rates of recurrence (21.2% vs. 20.7%, p=1.000) or death (16.7% vs. 6.9%, p=0.332) between the 2 groups. There was no difference in the pattern of recurrence or in disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) between the 2 groups. In multivariate analysis, pretreatment cancer antigen-125 >35 U/mL and International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics stage IC were significant factors of worse DFS and OS, while dense adhesion was not a prognostic factor for both DFS (hazard ratio [HR]=0.9; 95% confidence interval [CI]=0.3–2.7; p=0.792) and OS (HR=0.2; 95% CI=0.1–1.8; p=0.142), nor were age, proportion of staging procedure, histologic type, and co-presence of endometriosis. Moreover, the distribution of those 2 significant prognostic factors was not different between the 2 groups. Dense adhesions were subgrouped into non-tumor and tumor associated dense adhesions for further analysis and the results were same.

Conclusion

FSS is feasible and safe in EOC, regardless of the presence of dense adhesions.

Keywords: Tissue Adhesions, Ovarian Neoplasms, Fertility Preservation, Gynecologic Surgery

INTRODUCTION

Epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) is one of the most common causes of gynecological cancer death worldwide [1]. It is also the second most common gynecologic cancer in women of reproductive age in Korea, with a steady increase in incidence the last 10 years, and it is estimated that it will be the ninth most common cancer-related cause of death in 2015 [2,3,4]. Most women with EOC are diagnosed at an advanced stage due to a lack of early symptoms and effective screening methods. Debulking surgery including hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, peritoneal washing with suspicious site sampling, omentectomy, and lymph node dissection followed by paclitaxel and platinum chemotherapy is the standard management for EOC [5].

At the same time, approximately 30% of EOC patients are diagnosed at an apparently localized early stage [6,7]. In total, 3%–17% of all EOCs are diagnosed in women younger than 40 years, many of whom desire preservation of their reproductive function [6,8]. Initially, fertility-sparing surgery (FSS) in these cases was considered only in highly selected patients [5]. Thereafter, according to the guidelines of the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO, 2008) and the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists (ACOG, 2007), FSS was proposed for International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage I non-clear cell type EOC, tumor grade I/II, and with no dense adhesions with close follow-up [9,10].

Dense adhesions around the EOC and the adjacent pelvic structures occur relatively frequently in these patients and previous studies have included the presence of dense adhesions as one of the prognostic factors of early-stage EOC, but all of the patients in these studies were treated with comprehensive debulking surgery, and the results of these studies are conflicting [11,12,13,14]. Thus, the revised FIGO staging system recommended that dense adhesions with histologically proven tumor cells in an adhesion band can justify upgrading to stage II [15]. There has been no previous report that has focused specifically on the clinical impact of dense adhesions on FSS for EOC. We therefore investigated this in our current study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Patients

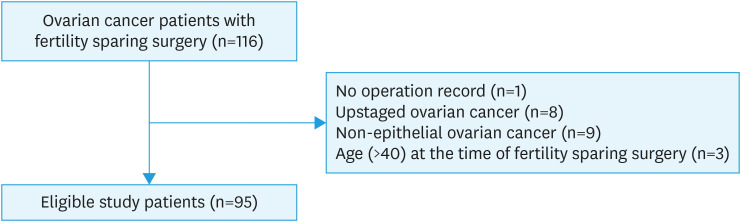

With approval from the Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center (#2015-0114), the electronic medical records of 116 patients with early stage ovarian cancer who underwent FSS from 1990 to 2013 at Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Korea, were retrospectively reviewed. Patients ≤40 years who underwent FSS for FIGO stage I EOC with/without dense adhesions were included. Study patients included not only those who underwent primary surgery at Asan Medical Center, but also those who were referred to Asan Medical Center for complete staging surgery after incomplete surgery in another hospital. Patients with non-epithelial ovarian tumors, follow-up loss, missing medical records, and those who previously received radiotherapy to the abdomen and/or pelvis were excluded. In total, 95 eligible patients were enrolled in this study (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Flow diagram of the selection process for the patients included in this study.

EOC, epithelial ovarian cancer; FSS, fertility-sparing surgery.

The study patients were divided into 2 groups, patients with dense adhesions between the EOC and its surrounding structures and patients with no dense adhesions. These groups were compared in terms of clinicopathologic characteristics and survival outcomes. This was a retrospective study and sample size calculation was statistically unnecessary. Dense adhesion was defined as any adherence with the ovarian tumor identified by the surgeon requiring sharp dissection to be mobilized from surrounding structures. No dense adhesion was defined as the absence of adhesions determined by the surgeon. Patients with high-risk factors (clear cell histological type, high tumor grade, tumor growth through the capsule with surface excrescences, malignant cells in peritoneal washing or ascitic fluid, and preoperative rupture) were treated with adjuvant chemotherapy. Although, these patients were not an indication for FSS, it was performed under informed consent when there was a strong patient's desire for fertility preservation. Staging procedure was defined as FSSs that included exploration of the whole peritoneal cavity including followings: peritoneal washings; multiple biopsies of suspicious peritoneal site; appendectomy; and omentectomy. Pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy was optional choice. In our hospital, complete staging procedure is a principle of management in early stage EOC patients. But lymphadenectomy is not routinely performed in early stage EOC patients with mucinous histologic type, and was omitted by the situation because of its favorable prognosis with no difference in recurrence according to extent of surgery [16], which was in concordance with other institutions [17,18,19,20]. Follow-up after surgery included physical/pelvic examination, assessment of tumor markers, and imaging by ultrasonography, computed tomography, positron emission tomography, and/or positron emission tomography/computed tomography. Regular follow-up and assessment of patients in an outpatient clinic were performed every 3 months during the first 2 years, every 6 months during the next 3 years, and yearly thereafter after the completion of primary treatment.

2. Statistical analysis

Mean and median values of variables were analyzed by the Student's t-test and Mann Whitney U test. Fisher's exact/χ2 tests were used to compare the distributions of the frequencies of the clinicopathologic characteristics of patients.

Disease-free survival (DFS) was calculated from the date of surgery to the date of recurrence or the date of last follow-up in patients without recurrence. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the date of surgery to the date of death or the date of last follow-up in patients who were alive. DFS and OS were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method and survival differences were compared using the log rank test. A multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression was used to determine independent prognostic factor. Data were statistically analyzed using SPSS software (version 21.0; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Differences were considered statistically significant when the p-value was less than 0.05.

RESULTS

1. Clinicopathological characteristics of the study patients

Of 95 EOC patients with FSS, 29 (30.5%) had dense adhesions. There was no difference between the 2 groups in terms of parity, tumor size, cancer antigen-125 (CA-125) at the time of diagnosis, FIGO stage, recurrence, or death. The mean age of the dense adhesion group was higher than that of the no dense adhesion group. The dense adhesion group had a higher proportion of the co-presence of endometriosis than the no dense adhesion group. The no dense adhesion group had a higher proportion of the mucinous histologic type and lower proportion of the mixed histologic type than the dense adhesion group (Table 1).

Table 1. Clinicopathological characteristics of the study patients.

| Characteristics | Total (n=95) | No dense adhesions (n=66) | Dense adhesions (n=29) | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 28.0±6.8 (10–40) | 26.7±6.9 (10–40) | 31.2±5.4 (17–40) | 0.003 | |||

| ≤28 | 51 (53.7) | 41 (62.1) | 10 (34.5) | 0.015 | |||

| >28 | 44 (46.3) | 25 (37.9) | 19 (65.5) | ||||

| Para | |||||||

| 0 | 80 (84.2) | 57 (86.4) | 23 (79.3) | 0.379 | |||

| ≥1 | 15 (15.8) | 9 (13.6) | 6 (20.7) | ||||

| Tumor size (cm) | 14.3±8.0 (1.0–33.0) | 15.2±8.0 (1.0–33.0) | 12.4±7.7 (2.2–30.0) | 0.109 | |||

| ≤14.3 | 52 (54.7) | 33 (50.0) | 19 (65.5) | 0.185 | |||

| >14.3 | 43 (45.3) | 33 (50.0) | 10 (34.5) | ||||

| CA-125 (median, U/mL) | 34.7 (5.9–3,410.0) | 32.7 (5.9–1,020.0) | 39.9 (6.1–3,410.0) | 0.162 | |||

| ≤35 | 50 (52.6) | 36 (54.5) | 14 (48.3) | 0.658 | |||

| >35 | 45 (47.4) | 30 (45.5) | 15 (51.7) | ||||

| Co-presence of endometriosis | 0.011 | ||||||

| No | 60 (63.2) | 48 (72.7) | 12 (41.4) | ||||

| Yes | 27 (28.4) | 13 (19.7) | 14 (48.3) | ||||

| Not available | 8 (8.4) | 5 (7.6) | 3 (10.3) | ||||

| Histologic type | 0.011 | ||||||

| Serous | 8 (8.4) | 6 (9.1) | 2 (6.9) | 1.000 | |||

| Mucinous | 55 (57.9) | 44 (66.7) | 11 (37.9) | 0.013 | |||

| Endometrioid | 13 (13.7) | 8 (12.1) | 5 (17.2) | 0.527 | |||

| Clear cell | 16 (16.8) | 8 (12.1) | 8 (27.6) | 0.078 | |||

| Mixed | 3 (3.2) | 0 (0) | 3 (10.3) | 0.026 | |||

| Grade | 0.093 | ||||||

| I | 59 (62.1) | 46 (69.7) | 13 (44.8) | 0.038 | |||

| II | 12 (12.6) | 6 (9.1) | 6 (20.7) | 0.177 | |||

| III | 23 (24.2) | 13 (19.7) | 10 (34.5) | 0.129 | |||

| Clear cell | 13 (13.7) | 8 (12.1) | 5 (17.25) | ||||

| Non-clear cell | 10 (10.5) | 5 (7.6) | 5 (17.25) | ||||

| Unclassified | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0) | 1.000 | |||

| FIGO stage | 0.814 | ||||||

| IA | 58 (61.1) | 41 (62.1) | 17 (58.6) | ||||

| IB | 2 (2.1) | 1 (1.5) | 1 (3.4) | ||||

| IC | 35 (36.8) | 24 (36.4) | 11 (37.9) | ||||

| Substage | 0.669 | ||||||

| IC1 | 23 (24.2) | 16 (24.2) | 7 (24.1) | ||||

| IC2 | 8 (8.4) | 6 (9.1) | 2 (6.9) | ||||

| Tumor on ovarian surface | - | 4 (6.1) | 2 (6.9) | ||||

| Preoperative rupture | - | 2 (3.0) | 0 (0) | ||||

| IC3 | 4 (4.2) | 2 (3.0) | 2 (6.9) | ||||

| Recurrence | 20 (21.1) | 14 (21.2) | 6 (20.7) | 1.000 | |||

| Loco-regional | 6 (30.0) | 3 (21.4) | 3 (50.0) | 0.373 | |||

| Distant | 7 (35.0) | 6 (42.9) | 1 (16.7) | ||||

| Both | 7 (35.0) | 5 (35.7) | 2 (33.3) | ||||

| Death | 13 (13.7) | 11 (16.7) | 2 (6.9) | 0.332 | |||

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation or number (%).

CA-125, cancer antigen-125; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

2. Type of FSS and adjuvant therapy of the study patients

There were no differences in terms of the method of adnexal surgery, intra-operative blood transfusion, operation time, surgical approach, lymph node sampling and/or dissection, omentectomy, restaging surgery, adjuvant chemotherapy, adjuvant chemotherapy regimen, and number of cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy. Patients with dense adhesion had a higher proportion of staging procedures compared to patients with no dense adhesion (Table 2).

Table 2. Type of fertility-sparing surgery and adjuvant therapy of the study patients.

| Characteristics | Total (n=95) | No dense adhesions (n=66) | Dense adhesions (n=29) | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method of adnexal surgery | 0.266 | ||||||

| Cystectomy | 3 (3.2) | 1 (1.5) | 2 (6.9) | ||||

| Both ovarian cystectomy | 2 (2.1) | 2 (3.0) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Oophorectomy | 6 (6.3) | 6 (9.1) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Salpingo-oophorectomy | 51 (53.7) | 33 (50.0) | 18 (62.1) | ||||

| Oophorectomy with cystectomy or wedge resection of contralateral ovary | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Salpingo-oophorectomy with cystectomy or wedge resection of contralateral ovary | 32 (33.7) | 23 (34.8) | 9 (31.0) | ||||

| Surgical complexity | |||||||

| Intra-operative blood transfusion | 0.643 | ||||||

| Yes | 2 (2.1) | 1 (1.5) | 1 (3.4) | ||||

| No | 83 (87.4) | 59 (89.4) | 24 (82.8) | ||||

| Not available | 10 (10.5) | 6 (9.1) | 4 (13.8) | ||||

| Operation time (mean, min) | 137.9±70.2 (40–377) | 134.5±70.7 (40–377) | 145.0±70.0 (50–327) | 0.519 | |||

| Not available | 8 (8.4) | 7 (10.6) | 1 (3.4) | 0.428 | |||

| Surgical approach | 0.632 | ||||||

| Open surgery | 66 (69.5) | 47 (71.2) | 19 (65.5) | ||||

| Laparoscopy | 29 (30.5) | 19 (28.8) | 10 (34.5) | ||||

| Staging operation | 0.033 | ||||||

| No | 32 (33.7) | 27 (40.9) | 5 (17.2) | ||||

| Yes | 63 (66.3) | 39 (59.1) | 24 (82.8) | ||||

| Lymph node sampling and/or dissection | 0.822 | ||||||

| No | 55 (57.9) | 39 (59.1) | 16 (55.2) | ||||

| Yes | 40 (42.1) | 27 (40.9) | 13 (44.8) | ||||

| PLNS | 10 (25.0) | 8 (29.6) | 2 (15.4) | 0.481 | |||

| PLND | 5 (12.5) | 4 (14.8) | 1 (7.7) | ||||

| PLND & PALNS | 15 (37.5) | 10 (37.0) | 5 (38.5) | ||||

| PLND & PALND | 10 (25.0) | 5 (18.5) | 5 (38.5) | ||||

| Omentectomy | 0.073 | ||||||

| No | 44 (46.3) | 35 (53.0) | 9 (31.0) | ||||

| Yes | 51 (53.7) | 31 (47.0) | 20 (69.0) | ||||

| Partial | 37 (72.5) | 22 (71.0) | 15 (75.0) | 1.000 | |||

| Total | 14 (27.5) | 9 (29.0) | 5 (25.0) | ||||

| Restaging surgery | 0.268 | ||||||

| No | 76 (80.0) | 55 (83.3) | 21 (72.4) | ||||

| Yes | 19 (20.0) | 11 (16.7) | 8 (27.6) | ||||

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | |||||||

| No | 30 (31.6) | 22 (33.3) | 8 (27.6) | 0.639 | |||

| Yes | 65 (68.4) | 44 (66.7) | 21 (72.4) | ||||

| Regimen | 0.789 | ||||||

| Taxane/platinum | 37 (56.9) | 26 (59.1) | 11 (52.4) | ||||

| Other | 28 (43.1) | 18 (40.9) | 10 (47.6) | ||||

| Cycles | 0.095 | ||||||

| ≤3 | 23 (35.4) | 19 (43.2) | 4 (19.0) | ||||

| >3 | 42 (64.6) | 25 (56.8) | 17 (81.0) | ||||

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation or number (%).

PALND, para-aortic lymph node dissection; PALNS, para-aortic lymph node sampling; PLND, pelvic lymph node dissection; PLNS, pelvic lymph node sampling.

3. Characteristics of the dense adhesions

Most of the dense adhesions were loco-regional type. Adhesions with a distant extrapelvic structure were found in 13.8% of the patients with dense adhesions, and all of these patients had an adhesion with the omentum. Most of the dense adhesions involved a single site (Table 3). Approximately, one third of the patients had previous history which can be the cause of dense adhesion. One (3.4%) had previous history of intraperitoneal inflammatory disease and 8 (27.6%) had previous history of abdominal surgery.

Table 3. Characteristics of the dense adhesions in the study patients (n=29).

| Characteristics | No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Site of dense adhesion | |||

| Loco-regional pelvic structure | 25 (86.2) | ||

| Broad ligament (fallopian tube, mesovarium, and mesosalpinx) | 4 (13.8) | ||

| Pelvic wall | 5 (17.2) | ||

| Rectum | 3 (10.3) | ||

| PCDS | 4 (13.8) | ||

| Uterus + broad ligament | 1 (3.4) | ||

| Broad ligament + pelvic wall | 1 (3.4) | ||

| Rectum + pelvic wall | 1 (3.4) | ||

| Uterus + pelvic wall | 3 (10.3) | ||

| Broad ligament + pelvic wall + rectum | 1 (3.4) | ||

| Broad ligament + pelvic wall + PCDS | 1 (3.4) | ||

| Broad ligament + pelvic wall + uterus | 1 (3.4) | ||

| Distant organ | 2 (6.9) | ||

| Omentum | 2 (6.9) | ||

| Both | 2 (6.9) | ||

| Pelvic wall + omentum | 1 (3.45) | ||

| Rectum + omentum | 1 (3.45) | ||

| No. of dense adhesion sites of tumor with an adjacent structure | |||

| Single | 18 (62.1) | ||

| Multiple | 11 (37.9) | ||

| Previous history in patients with dense adhesion | |||

| Previous history of inflammatory disease | 1 (3.4) | ||

| Previous history of surgery | 8 (27.6) | ||

| Tumor itself | 20 (69.0) | ||

PCDS, posterior cul de sac.

4. Survival outcomes of patients with EOC with/without dense adhesions

In total, the median follow-up period was 57.8 (0.4–230.0) months. There was no difference in the median follow-up period between patients with EOC with no dense adhesions and those with dense adhesions (55.6 months vs. 58.8 months, respectively; p=0.774). Fourteen (21.2%) and 6 (20.7%) patients recurred in the no dense adhesion and dense adhesion groups, respectively (p=1.000). In total, the mean time to recurrence was 20.9±17.7 (4.5–54.1) months. There was no difference in the mean time to recurrence between patients with EOC with no dense adhesions and those with dense adhesions (22.5 months vs. 17.1 months, respectively; p=0.548). There was also no difference between the 2 groups in terms of the pattern of recurrence (Table 1). Eleven (16.7%) and 2 (6.9%) patients died of disease in the no dense adhesion and dense adhesion groups, respectively (p=0.332).

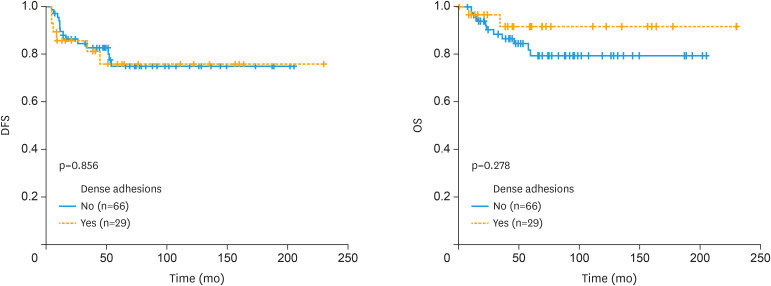

There was no significant difference in the DFS (160.2±10.6 months, 95% confidence interval [CI]=139.4–181.1 months vs. 178.9±18.5 months, 95% CI=142.7–215.0 months, p=0.856) and OS (169.4±9.8 months, 95% CI=150.3–188.5 months vs. 212.7±11.8 months, 95% CI=189.5–235.9 months, p=0.278) outcomes between patients with EOC with no dense adhesions and those with dense adhesions (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Disease-free and overall survival outcomes of patients with epithelial ovarian cancer with/without dense adhesions.

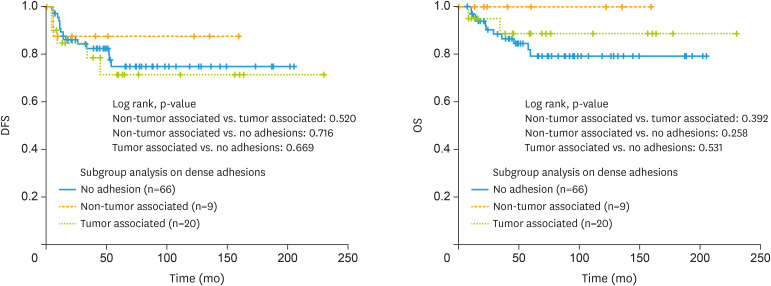

Further, dense adhesions were subgrouped into non tumor and tumor associated dense adhesions for further analysis. Dense adhesions with previous history of inflammatory disease or surgery were defined as non-tumor associated group. Dense adhesions with tumor as a possible cause of dense adhesions were defined as tumor associated group and there were no survival differences between these 3 groups (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Disease-free and overall survival outcomes of patients with epithelial ovarian cancer with/without non tumor and tumor associated dense adhesions.

Finally, a multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis was performed. Dense adhesions were not a statistically independent prognostic factor for both DFS (hazard ratio [HR]=0.9; 95% CI=0.3–2.7; p=0.792) and OS (HR=0.2; 95% CI=0.1–1.8; p=0.142) (Table 4).

Table 4. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis of the study patients.

| Variables | DFS (%) | HR (95% CI) | p | OS (%) | HR (95% CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean; yr) | |||||||

| ≤28 vs. >28 | 80.4 vs. 77.3 | 2.1 (0.7–6.6) | 0.214 | 82.4 vs. 90.9 | 0.7 (0.1–5.2) | 0.751 | |

| CA-125 (median; U/mL) | |||||||

| ≤35 vs. >35 | 92.0 vs. 64.4 | 11.8 (2.4–57.2) | 0.002 | 92.0 vs. 80.0 | 9.4 (1.8–50.5) | 0.009 | |

| Co-presence of endometriosis | |||||||

| No vs. Yes | 83.3 vs. 77.8 | 1.9 (0.4–8.4) | 0.391 | 85.0 vs. 96.3 | 0.3 (0.1–5.8) | 0.436 | |

| Histologic type | |||||||

| Non-mucinous vs. mucinous | 80.0 vs. 77.5 | 2.3 (0.5–9.7) | 0.257 | 90.0 vs. 83.6 | 3.8 (0.4–38.6) | 0.262 | |

| Grade | |||||||

| I–II vs. III | 81.7 vs. 69.6 | 0.4 (0.1–2.3) | 0.328 | 87.3 vs. 82.6 | 3.9 (0.3–50.3) | 0.297 | |

| FIGO stage | |||||||

| IA–IB vs. IC | 83.3 vs. 71.4 | 4.1 (1.1–15.2) | 0.037 | 90.0 vs. 80.0 | 6.1 (1.2–32.4) | 0.032 | |

| Method of adnexal surgery | |||||||

| Non-USO vs. USO | 75.0 vs. 79.5 | 1.1 (0.2–5.1) | 0.951 | 83.3 vs. 86.7 | 1.2 (0.1–12.2) | 0.851 | |

| Staging operation | |||||||

| No vs. yes | 81.3 vs. 77.8 | 1.5 (0.4–5.7) | 0.524 | 87.5 vs. 85.7 | 1.8 (0.4–8.5) | 0.430 | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | |||||||

| No vs. yes | 83.3 vs. 76.9 | 0.3 (0.1–1.5) | 0.141 | 86.7 vs. 86.2 | 0.2 (0.1–1.1) | 0.063 | |

| Dense adhesion | |||||||

| No vs. yes | 78.8 vs. 79.3 | 0.9 (0.3–2.7) | 0.792 | 83.3 vs. 93.1 | 0.2 (0.1–1.8) | 0.142 | |

CA-125, cancer antigen-125; CI, confidence interval; DFS, disease-free survival; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; HR, hazard ratio; OS, overall survival; USO, unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.

DISCUSSION

In total, 30.5% of our current study cohort had dense adhesions around the early-stage EOC, which is similar to the findings of previous reports [13,14,21]. In total, the DFS and OS rates were 78.9% and 86.3%, respectively, which is similar to the FSS survival rates reported previously [17,19,22]. In our current study, patients with pretreatment CA-125 >35 U/mL and FIGO stage IC were significant factors of worse DFS and OS, while dense adhesion was not a prognostic factor for both DFS and OS, nor were age, proportion of staging procedure, histologic type, and co-presence of endometriosis. Moreover, the distribution of those 2 significant prognostic factors was not different between the 2 groups. Dense adhesions were subgrouped into non-tumor and tumor associated dense adhesions for further analysis and the results were same.

Many previous studies have investigated the variables that may affect the feasibility of FSS in EOC, such as FIGO stage, tumor grade, and histologic subtype, reporting that these variables are important prognostic factors [5,17,19,22,23,24,25,26]. No study to date has investigated whether the presence of dense adhesions around the tumor can be a prognostic factor in this setting, although this may be an important issue. Defining the dense adhesion belongs to subjective territory even one defines it strictly, and analyses would probably have been more difficult than evaluations of clearly determined pathologic data and outcomes.

Nonetheless, even considering these difficulties, we believe that there should be a detailed investigation of the oncologic safety of FSS in early-stage EOC with dense adhesions because the FIGO staging system was unable to offer a clear guideline for distinguishing the stage in this situation. In the guidelines of the ESMO (2008) and ACOG (2007), stage I EOC with non-clear cell type, grade I/II with no dense adhesion is an indication for FSS [9,10]. Dense adhesions in stage I EOC have been reported, but none of the patients enrolled in these studies underwent FSS [11,12,13,14]. Additionally, dense adhesions were not the main focus of these investigations, being just one of the characteristics of the patients. In one recent study, recurrence according to the revised FIGO stage, histologic type, and tumor grade in early-stage EOC, and speculated that FSS may be feasible in FIGO stage IC1 EOC, unless the tumor has a dense tumor-associated adhesion. However, there was no investigation or analysis of dense adhesions in that study, and the definition of a dense adhesion was not determined [18]. To our knowledge, our current study is the first focused investigation of the feasibility and safety of FSS in stage I EOC with dense adhesions (Table 5).

Table 5. Definitions of dense adhesions and results of previous studies.

| Authors | Dense adhesion definition | Primary focus of the study | Fertility-sparing surgery | Dense adhesion presence was an independent prognostic factor | FIGO stage | Frequency of patients with dense adhesions in the cohort (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dembo et al. [11] | When sharp dissection was required to mobilize the tumor, when a raw area was left in the place of adherence, or when cyst rupture resulted from dissecting free the adhesions, or direct tumor invasion of adjacent structures was observed | Predictive factors of relapse | No | Yes | I, II, III | 12.3 (in stage I) |

| Vergote et al. [21] | Any adherence requiring sharp dissection | Prognostic factors, including DNA ploidy | No | No | I | 36.2 |

| Tropé et al. [14] | Any adherence requiring sharp dissection | Role of adjuvant chemotherapy and prognostic value of DNA ploidy | No | No | I | 48.8 |

| Vergote et al. [13] | Any adherence requiring sharp dissection | Identification of prognostic indicators | No | No | I | 23 |

| Seidman et al. [12] | When sharp dissection was required to mobilize the tumor, when a raw area was left in the place of adherence, or when cyst rupture resulted from dissecting free the adhesions | Comparison of pathologic stage I and surgical-pathologic stage II | No | No | I, II (pathologic stage I vs. surgical-pathologic stage II) | 100 (comparing the character of dense adhesion itself) |

| Current series | Any adherence requiring sharp dissection to be mobilized from surrounding structures | Dense adhesions | Yes | No | I | 30.5 |

FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

In FIGO stage I, the EOC tumor is confined to the ovary. If there is any pelvic extension or implantation, the EOC is considered to be stage II. It is difficult to distinguish stage I from stage II in EOCs that are macroscopically confined to the ovary but have dense adhesions. Previous FIGO staging recommendations had no clear guidelines on how to intraoperatively assign the stage and interpret what appears to be stage I EOC with dense adhesions [27]. Recently, the revised FIGO staging system upgraded stage I to stage II only when malignant cells are confirmed histologically in the adhesion band [15]. However, it is still unknown whether stage upgrading based on dense adhesions is warranted. The upgrading of stage I to stage II lesions because of dense adhesions around the ovary and its surrounding structures is performed at only some of several major cancer institutions in the Europe and United States [12].

Seidman et al. [12] investigated the effect of dense adhesions in ovarian cancer by comparing patients with tumor cells that have extended to adjacent pelvic structures (surgical-pathologic stage II) with patients without those features (pathologic stage I). The 5-year OS was significantly lower for surgical-pathologic stage II than pathologic stage I. Additionally, Dembo et al. [11] and Ozols et al. [28] revealed that the recurrence rate was similar to that of FIGO stage II ovarian cancer if the adhesions were dense. At the same time, Vergote et al. [13] found no difference in their large-scale multicenter study. Compared with Dembo et al. [11], Vergote et al. [13] and Tropé et al. [14] did not find the presence of dense adhesions to be an independent prognostic factor of DFS. As Vergote et al. [13] stated in their previous study, Dembo et al. [11] defined dense adhesions also when adjacent pelvic structures surrounding the ovarian cancer had a direct tumor invasion [11], which equals FIGO stage II, and this may be the reason for the different results of these studies including current series (Table 5).

The frequency of microscopic tumor cells in the adhesion band was not reported in previous studies because most operations were performed before the announcement of the revised FIGO staging system [11,13,14]. In our current study, the frequency of microscopic tumor cells was pathologically investigated in 11 of 30 patients (36.7%) who had dense adhesions between the tumor and its surrounding structures. Of these, only one patient had tumor-positive cells in adhesion band and was excluded from this study (upstaged to stage II according to the revised FIGO staging system). If we had these results for the remaining patients, we would have been able to compare the impact of the presence of tumor cells in the adhesion band (stage II according to the revised FIGO staging system) with that of no tumor cells (stage I) by subgrouping the cases with dense adhesions around the tumor. In addition, we could have compared the survival outcomes of FSS in stage II EOCs with an apparent pelvic extension or implantations with that of upgraded stage II EOCs with microscopic tumor cells in the adhesion band if these data had been available. Thus, it might be too early to draw the conclusion that FSS is generally safe in EOC with dense adhesion. We believe that there should be a pathological report on the adhesion band in all future cases to gain a more accurate staging of early EOC. Moreover, if FSS is feasible and safe in upgraded stage II EOCs only because of tumor cells in the adhesion band, the indications for FSS in EOC could be broadened in this setting and redefined.

In our current study series, the frequency of the staging procedure was higher in the dense adhesion group compared to the no dense adhesion group. There was a lower proportion of the mucinous type in our dense adhesion group compared with the no adhesion group, as previously reported [12]. These were one of the clinicopathologic differences between the 2 groups, but even after adjusting for these factors there was no difference in survival outcome between the 2 groups.

Kajiyama et al. [18] performed lymphadenectomy and omentectomy in 5.3% and 14.9% of the cohort, respectively. Fruscio et al. [19] performed these procedures in 15% and 31%, and Satoh et al. [17] performed 26.1% and 41.7% of their cohorts, respectively. In our present patient series, 42.1% and 53.7% of the cohort underwent lymphadenectomy and omentectomy, respectively, and there were no differences between these 2 groups.

There may be a possibility that some of the patients who did not receive these procedures may have a higher stage tumor that is not indicated for FSS like above mentioned studies [17,18,19]. Ditto et al. [29] recently investigated the oncologic safety of FSS in high-risk early-stage EOC and found that there was no difference in frequency of upstaging or survival outcome between the FSS group and the standard radical surgical procedure group. Also, observing high staging procedure proportion compared to previous series [17,18,19], we believe there is a minimal obstacle for investigating the effect of dense adhesions on FSS on early-stage EOC.

As Dembo et al. [11] remarked in their previous study, we also acknowledge that although we made an effort to strictly define dense adhesions, there may be many other factors, such as differing opinions or subjectivity of the surgeons and characteristics of retrospective chart review study, that could have biased the classification. Also, limited information on presence of microscopic tumor in dissected margin of surgical field, area of dense adhesions, and adhesion status on other part of pelvic structure due to retrospective chart review study design is another shortcoming of this series. Although, a multivariate statistical adjustment for possible confounders were performed, comparable survival rates of both groups still could come from the imbalance of background prognostic factors (mean age, proportion of staging procedure, and distribution of histologic type). Further, there is a possibility of type II error because of relatively small study number due to the rarity of patients. There might also be inconsistencies in the adjuvant chemotherapy regimens, surgical policy, and approach to dense adhesions between reports because we included patients who underwent FSS more than 10 years ago.

A notable strength of our study is that we minimized the bias that can occur when multiple factors are examined by focusing on dense adhesions. The participation of a limited number of gynecologic oncologists who are dedicated to their subspecialties should have minimize the bias derived from differences in opinions about dense adhesions, which may have occurred in previous nationwide or worldwide multicenter studies. Moreover, our results are one of the largest number of patients from a single institution with long-term data evaluated to date who underwent FSS for EOC.

FSS in early-stage EOC was a feasible and safe treatment approach in our current patient series, regardless of the presence of dense adhesions around the tumor. We conclude from our analyses that dense adhesions in early-stage EOC are not an obstacle to FSS.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

- Conceptualization: P.J.Y., K.J.H., K.Y.M., K.Y.T.

- Data curation: B.M.H., P.J.Y., K.Y.M.

- Formal analysis: B.M.H.

- Investigation: B.M.H.

- Methodology: B.M.H.

- Project administration: P.J.Y., K.J.H., K.Y.T.

- Supervision: P.J.Y., K.D.Y., S.D.S., K.J.H., K.Y.M., K.Y.T.

- Validation: P.J.Y., K.D.Y., K.Y.M.

- Visualization: B.M.H., P.J.Y., S.D.S., K.Y.T.

- Writing - review & editing: B.M.H.

References

- 1.Greenlee RT, Hill-Harmon MB, Murray T, Thun M. Cancer statistics, 2001. CA Cancer J Clin. 2001;51:15–36. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.51.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jung KW, Won YJ, Kong HJ, Oh CM, Cho H, Lee DH, et al. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2012. Cancer Res Treat. 2015;47:127–141. doi: 10.4143/crt.2015.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lim MC, Moon EK, Shin A, Jung KW, Won YJ, Seo SS, et al. Incidence of cervical, endometrial, and ovarian cancer in Korea, 1999-2010. J Gynecol Oncol. 2013;24:298–302. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2013.24.4.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jung KW, Won YJ, Oh CM, Kong HJ, Cho H, Lee DH, et al. Prediction of cancer incidence and mortality in Korea, 2015. Cancer Res Treat. 2015;47:142–148. doi: 10.4143/crt.2015.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morice P, Leblanc E, Rey A, Baron M, Querleu D, Blanchot J, et al. Conservative treatment in epithelial ovarian cancer: results of a multicentre study of the GCCLCC (Groupe des Chirurgiens de Centre de Lutte Contre le Cancer) and SFOG (Société Francaise d'Oncologie Gynécologique) Hum Reprod. 2005;20:1379–1385. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.FIGO (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics) annual report on the results of treatment in gynecological cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;83(Suppl 1):ix–xxii. 1–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paik ES, Lee YY, Lee EJ, Choi CH, Kim TJ, Lee JW, et al. Survival analysis of revised 2013 FIGO staging classification of epithelial ovarian cancer and comparison with previous FIGO staging classification. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2015;58:124–134. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2015.58.2.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Plaxe SC, Braly PS, Freddo JL, McClay E, Kirmani S, Howell SB. Profiles of women age 30-39 and age less than 30 with epithelial ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;81:651–654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aebi S, Castiglione M ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Epithelial ovarian carcinoma: ESMO clinical recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(Suppl 2):ii14–6. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin. Management of adnexal masses. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:201–214. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000263913.92942.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dembo AJ, Davy M, Stenwig AE, Berle EJ, Bush RS, Kjorstad K. Prognostic factors in patients with stage I epithelial ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75:263–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seidman JD, Cosin JA, Wang BG, Alsop S, Yemelyanova A, Fields A, et al. Upstaging pathologic stage I ovarian carcinoma based on dense adhesions is not warranted: a clinicopathologic study of 84 patients originally classified as FIGO stage II. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;119:250–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vergote I, De Brabanter J, Fyles A, Bertelsen K, Einhorn N, Sevelda P, et al. Prognostic importance of degree of differentiation and cyst rupture in stage I invasive epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Lancet. 2001;357:176–182. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03590-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tropé C, Kaern J, Hogberg T, Abeler V, Hagen B, Kristensen G, et al. Randomized study on adjuvant chemotherapy in stage I high-risk ovarian cancer with evaluation of DNA-ploidy as prognostic instrument. Ann Oncol. 2000;11:281–288. doi: 10.1023/a:1008399414923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prat J FIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology. Staging classification for cancer of the ovary, fallopian tube, and peritoneum. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2014;124:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cho YH, Kim DY, Kim JH, Kim YM, Kim KR, Kim YT, et al. Is complete surgical staging necessary in patients with stage I mucinous epithelial ovarian tumors? Gynecol Oncol. 2006;103:878–882. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Satoh T, Hatae M, Watanabe Y, Yaegashi N, Ishiko O, Kodama S, et al. Outcomes of fertility-sparing surgery for stage I epithelial ovarian cancer: a proposal for patient selection. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1727–1732. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.8617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kajiyama H, Mizuno M, Shibata K, Yamamoto E, Kawai M, Nagasaka T, et al. Recurrence-predicting prognostic factors for patients with early-stage epithelial ovarian cancer undergoing fertility-sparing surgery: a multi-institutional study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;175:97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2014.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fruscio R, Corso S, Ceppi L, Garavaglia D, Garbi A, Floriani I, et al. Conservative management of early-stage epithelial ovarian cancer: results of a large retrospective series. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:138–144. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schlaerth AC, Chi DS, Poynor EA, Barakat RR, Brown CL. Long-term survival after fertility-sparing surgery for epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19:1199–1204. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e31819d82c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vergote IB, Kaern J, Abeler VM, Pettersen EO, De Vos LN, Tropé CG. Analysis of prognostic factors in stage I epithelial ovarian carcinoma: importance of degree of differentiation and deoxyribonucleic acid ploidy in predicting relapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169:40–52. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90129-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kajiyama H, Shibata K, Suzuki S, Ino K, Nawa A, Kawai M, et al. Fertility-sparing surgery in young women with invasive epithelial ovarian cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2010;36:404–408. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park JY, Kim DY, Suh DS, Kim JH, Kim YM, Kim YT, et al. Outcomes of fertility-sparing surgery for invasive epithelial ovarian cancer: oncologic safety and reproductive outcomes. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;110:345–353. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raspagliesi F, Fontanelli R, Paladini D, di Re EM. Conservative surgery in high-risk epithelial ovarian carcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;185:457–460. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(97)00066-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zanetta G, Chiari S, Rota S, Bratina G, Maneo A, Torri V, et al. Conservative surgery for stage I ovarian carcinoma in women of childbearing age. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:1030–1035. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1997.tb12062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zapardiel I, Diestro MD, Aletti G. Conservative treatment of early stage ovarian cancer: oncological and fertility outcomes. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40:387–393. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2013.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heintz AP, Odicino F, Maisonneuve P, Quinn MA, Benedet JL, Creasman WT, et al. Carcinoma of the ovary. FIGO 26th annual report on the results of treatment in gynecological cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;95(Suppl 1):S161–92. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(06)60033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ozols RF, Rubin SC, Thomas GM, Robboy SJ. Epithelial ovarian cancer. In: Hoskins WJ, Perez CA, Young RC, Barakat R, Markman M, Randall M, editors. Principles and practice of gynecologic oncology. 4th ed. New York: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2003. p. 927. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ditto A, Martinelli F, Lorusso D, Haeusler E, Carcangiu M, Raspagliesi F. Fertility sparing surgery in early stage epithelial ovarian cancer. J Gynecol Oncol. 2014;25:320–327. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2014.25.4.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]