Abstract

Introduction

Research is needed to examine trajectories of tobacco use beyond cigarette smoking, particularly during emerging middle young adulthood, and to identify distinct multilevel influences of use trajectories.

Aims and Methods

We examined (1) tobacco use trajectories over a 2-year period among 2592 young adult college students in a longitudinal cohort study and (2) predictors of these trajectories using variables from a socioecological framework, including intrapersonal-level factors (eg, sociodemographics, psychosocial factors [eg, adverse childhood experiences, depressive symptoms, and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms], early-onset substance use), interpersonal factors (eg, social support, parental substance use), and community-level factors (eg, college type, rural vs. urban).

Results

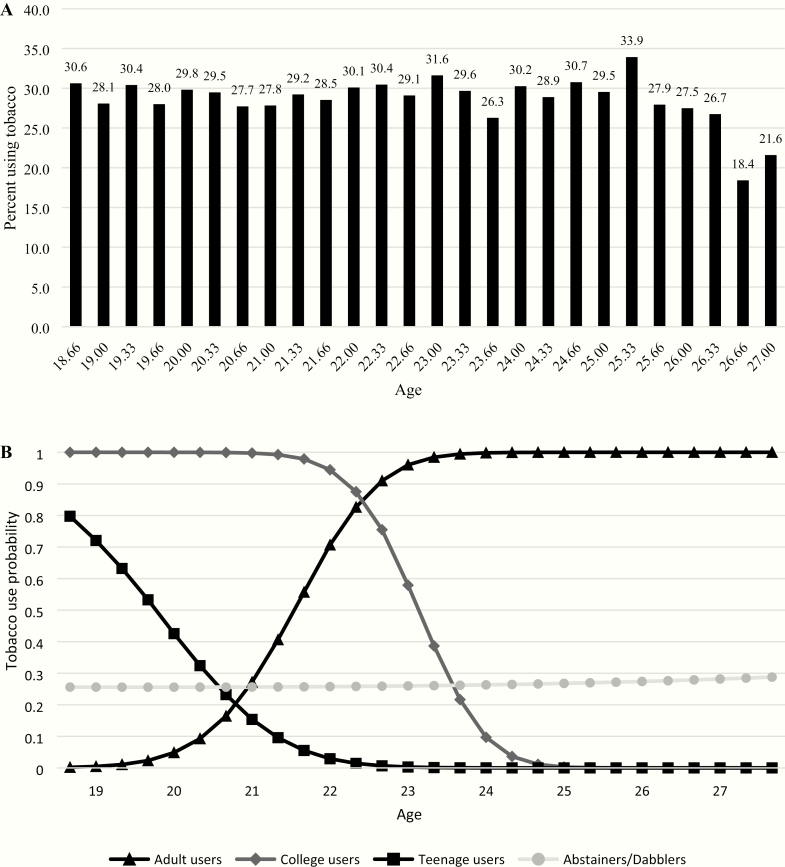

About 64.5% were female and 65.0% were white. From age 18 to 26, 27%–31% of participants reported past 30-day use of any tobacco product. We identified four trajectory classes: Abstainers/Dabblers who never or infrequently used (89.2%); Adult users who began using frequently around age 20 and continued thereafter (5.9%); College Smokers who began using before 19 but ceased use around 25 (2.5%); and Teenage users who used during their teenage years but ceased use by 22 (1.9%). Multinomial regression showed that, compared to Abstainers/Dabblers, significant predictors (p < .05) of being (1) Adult users included being male, earlier onset marijuana use, attending public universities or technical colleges (vs. private universities), and living in urban areas; (2) College users included being male, earlier onset marijuana use, and parental alcohol or marijuana use; and (3) Teenage users included only earlier onset marijuana use.

Conclusion

Distinct prevention and intervention efforts may be needed to address the trajectories identified.

Implications

Among young adult college students, the largest proportion of tobacco users demonstrate the risk of continued and/or progression of tobacco use beyond college. In addition, specific factors, particularly sex, earlier onset marijuana use, parental use of alcohol and marijuana, and contextual factors such as college setting (type of school, rural vs. urban) may influence tobacco use outcomes. As such, prevention and cessation intervention strategies are needed to address multilevel influences.

Introduction

Historically, the US tobacco market was comprised almost exclusively of cigarettes; however, the last decade entailed major shifts to include various alternative tobacco products (ATPs) including combustible tobacco products (eg, little cigars and cigarillos or LCCs) and noncombustible products (eg, electronic nicotine delivery systems [ENDS]).1–3

This new tobacco market has altered tobacco use, particularly among young adults. While cigarette smoking prevalence has decreased, ATP use prevalence has increased.3 Moreover, research has identified different clusters of tobacco users.4–6 One study of college students identified three tobacco use profiles: heavy polytobacco users (7.3% overall), light polytobacco users (17.3%), and LCC/hookah/marijuana co-users (10.4%).5 Another study grouped non-users or low-level users (61.8%), non-hookah tobacco users (6.8%), hookah/marijuana users (12.9%), and polysubstance users (5.6%).6 Another study of young adult California bar patrons identified six latent use classes: cigarette-only users (46.1%), high overall users (14.4%), and those mostly using LCCs (11.9%), smokeless tobacco (SLT, 2.6%), ENDS (12.0%), and hookah (13.1%), respectively.4 In these studies, tobacco use categorization was associated with sociodemographic and psychosocial factors (eg, depressive symptoms, social influences, and tobacco-related attitudes).4–6

This prior research provides cross-sectional snapshots of user profiles but does not address how these user profiles evolve over time, which is particularly important during the 20s, a critical period for tobacco use behavioral trajectories.7 Some prior research, focused almost exclusively on cigarettes, has identified various young adult tobacco use trajectories,8,9 including never-smokers, experimenters, light/occasional smokers, early established smokers, late escalators, and quitters/decliners.9 One analysis of nationally representative, longitudinal data from 9791 young adults (aged 18–34) identified three classes of smoking trajectories: nonsmokers (79.3%), rapid escalators or daily smokers (11.3%), and dabblers (9.4%).10 Other research has documented notable changes in tobacco use in 6 months11 or a year.12 Collectively, the literature indicates various young adult tobacco use trajectories8,9,13 but seldomly included or accounted for ATP use. This is critical given rapid changes in young adult tobacco use within the new tobacco market.12

The current study draws from socioecological developmental14 and social cognitive perspectives15 to examine trajectories of tobacco use, including cigarettes and ATPs, among young adult college students. These perspectives suggest that tobacco use and use trajectories are shaped during this pivotal developmental period by multilevel influences (eg, individual, interpersonal, and community).

In regard to individual-level factors influencing tobacco use, smoking progression is greater among men10,16,17 and those with lower educational attainment and annual income.10 In addition, although the prevalence of smoking among whites is higher than blacks in emerging adulthood (18–25 years), the prevalence declines during the 20s among whites but not blacks,10,18,19 resulting in roughly equal prevalence by age 30.18,19 Regarding psychosocial factors, tobacco use, specifically cigarette use, and development of addiction have been associated with experiencing more adverse childhood events (ACEs; eg, physical or sexual threat or abuse, parental divorce/separation),20,21 as well as having higher depressive22,23 and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms.24,25 With regard to ATPs, several studies have found no associations26–28; however, other cross-sectional research has found that depressive symptoms predict a greater likelihood of being classified in a tobacco use group29 and that LCC use was predicted by greater depressive symptoms, SLT use was predicted by greater ADHD symptoms, but ENDS and hookah use were not predicted by these psychological symptoms.30 In addition, other substance use, particularly the use of alcohol and marijuana (common among young adults31), is correlated with tobacco use.31,32 Moreover, tobacco use characteristics, such as early-onset use33–35 and polytobacco use,36–38 have been associated with the risk of nicotine dependence.

Interpersonal factors, including social support39,40 and parents using tobacco,10,29,33 have been shown to impact tobacco use trajectories. Also, community-level influences on young adult tobacco use may include whether they live in rural or urban areas, whether they attend college, and the type of college they attend1–3,41; for example, compared to 4-year colleges/universities, community/technical colleges have higher student smoking prevalence.41

The current study aimed to extend the literature by examining the trajectories of tobacco use beyond cigarette smoking from emerging young adulthood to middle young adulthood and identifying multilevel influences of use trajectories. Specifically, we examined (1) tobacco use trajectories over a 2-year period among young adult college students in a longitudinal cohort study and (2) predictors of these trajectories including factors at the intrapersonal (ie, sociodemographics, psychosocial factors [ie, ACEs, depressive symptoms, ADHD symptoms], substance use-related factors), interpersonal (ie, social support, parental substance use), and community levels (ie, type of college, rural vs. urban setting).

Methods

Procedures and Participants

The current study was conducted as part of a larger study, Project DECOY (Documenting Experiences with Cigarettes and Other Tobacco in Young Adults), a 2-year, six-wave longitudinal cohort study involving 3418 racially/ethnically diverse students (ages 18–25) from seven Georgia-based colleges/universities beginning in Fall 2014, consisting of self-report assessments via online surveys every 4 months for 2 years (Fall, Spring, and Summer). Two campuses had existing tobacco-free campus policies at the launch of the study, three implemented such policies in 2014, one implemented such a policy in 2015, and one remains without a comprehensive smoke-free policy. Project DECOY was approved by the Emory University and ICF Institutional Review Boards as well as those of the participating colleges/universities.

Detailed information on sampling and recruitment is available elsewhere.42 Briefly, eligible participants were 18–25 years old and able to read English. A list of students was obtained from each institution’s registrar’s office. One public and two private colleges/universities had 3000 students randomly selected from those eligible; the remaining colleges/universities had eligible student bodies less than 3000, so all eligible students were recruited. The invitation e-mails described the study and related incentives. Interested students were routed to the consent form and, once consented, completed the baseline (Wave 1 [W1]) survey.

Recruitment at each school closed after reaching recruitment goals. Response rates ranged from 12.0% to 59.4%, with an overall response rate of 22.9% (N = 3574/15 607) within 72 h at each school, meeting recruitment targets. A week after completing the baseline survey, participants were asked to “confirm” study participation by confirming their consent as a response to an e-mail sent to them reminding them of what the study entailed. They were then provided their first gift card ($30). The response rate after confirmation was 95.6% (N = 3418/3574). The baseline sample was largely representative of each school’s demographic profile, although respondents were disproportionately female.

Participants were e-mailed and texted before each wave of data collection. Retention across waves exceeded 70% (W2: 86.4%; W3: 83.9%; W4: 85.5%; W5: 78.7%; W6: 70.2%). Current analyses focus on the 2952 participants who reported any information regarding tobacco use beyond W1 (86.4% of the baseline sample), as we chose to model tobacco use from W2 to W6. Note that those who only completed the baseline survey (vs. those included in these analyses) were more likely to be Asian (vs. any other race), to attend an HBCU or technical college (vs. private school), and to report baseline past 30-day use of the range of tobacco products (except SLT) and marijuana (ps < .05). No significant differences were found with regard to age, sex, sexual orientation, ethnicity, parental education, or rural/urban setting.

Measures

Outcome

Tobacco use was assessed at W1 by asking, “For each of the following products, indicate if you have ever tried them in your lifetime: cigarettes, flavored little cigars or cigarillos (e.g., Black and Milds, Swisher Sweets cigarillos); chewing tobacco, snuff, or dip (e.g., Redman, Levi Garrett, Beechnut, Skoal, Copenhagen); snus (e.g., Camel/Marlboro Snus); electronic cigarettes, e-cigarettes, or vape pens (e.g., Blu or NJOY), and hookah or waterpipe.” Additionally, those who indicated lifetime use of each product were subsequently asked, “In the past four months, on how many days have you used each of the following products?” with response options ranging from 0 to 120. We categorized flavored little cigars and flavored cigarillos as LCCs and chewing tobacco, snuff, dip, and snus as SLT. Tobacco use was operationalized as any use of at least one of the tobacco products in the past 4 months at each timepoint in order to have data covering the 2-year period. At each wave, we also assessed the number of days of use in the past 30 days; we used this baseline assessment to characterize baseline tobacco use profiles among the user subgroups identified in growth mixture modeling (GMM).

Individual-Level Predictors

At W1, we assessed sociodemographics (eg, age, sex, sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, parental education level). Regarding psychosocial factors, ACEs were measured at W2 using the 10 items from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)-developed ACEs,43 which assess events (eg, parents with mental health or substance use problems, parental interpersonal violence, childhood maltreatment or abuse) occurring prior to age 18 (0 = no, 1 = yes; score range 0–10). Cronbach’s alpha was .75. Depressive symptoms were measured at W1 using the Patient Health Questionnaire—9 item,44 assessing symptoms in the past 2 weeks (0 = not at all to 3 = nearly every day; score range 0–27). Cronbach’s alpha was .87. ADHD symptoms were measured at W2 using the six screening items from the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale Symptom Checklist,45 assessing symptoms (eg, “difficulty getting things in order when a task requires organization”) in the past 6 months (0 = never to 4 = very often; score range 0–24). Cronbach’s alpha was .74.

Age of first use of marijuana, cigarettes, and alcohol was assessed at W1 and used to code early-onset use. Those who reported initiating use of marijuana at ≤18 years old, cigarettes at ≤16, or alcohol at ≤16 were defined as earlier onset users. These cutpoints were determined by examining distributions of the age of initiation across substances per the National Survey on Drug Use or Health.46 In addition, we assessed the past 30-day use of tobacco products (cigarettes, cigars, SLT, e-cigarettes, hookah), marijuana, and alcohol at W1.

At W6, participants were asked to indicate which products they had ever used among the following: cigarettes, large cigars, LCCs, chewing tobacco, snus, e-cigarettes or vapes, and hookah. We calculated the number of products ever used based on this question.

Interpersonal-Level Factors

Social support was measured at W2 using the Interpersonal Support Evaluation List—12 item,47 assessing the perceived social support on a four-point scale (0 = definitely false to 3 = definitely true). Items are summed to yield a total score (range 0–36); three subscales comprised of four items each can also be calculated (appraisal, belonging, tangible; subscale score range 0–12). Cronbach’s alpha was .85. Parental substance use was assessed at W1 by asking participants if any parent currently used marijuana, tobacco (cigarettes, cigars, SLT, e-cigarettes, hookah), or alcohol, respectively.48

Community-Level Factors

Schools were categorized by type (private, public, HBCU, technical college) and as rural or urban.

Data Analysis

First, we calculated descriptive statistics for all variables to screen for outliers or influential data points. Then, GMM was used to analyze tobacco use by age as the time ordering dimension (rather than by wave which would confound age heterogeneity), which facilitated (1) identification of a set of discrete, mutually exclusive latent classes of tobacco use trajectories from age 18 to 28 (using longitudinal data, W2–W6) and (2) variation in trajectories across individuals based on age and estimates mean parameters for each trajectory.49 We fitted linear curves, which identified use trajectory classes, while accounting for the clustering of students in schools. Quadratic models did not yield a solution for two and three class models within 48 h of computing and were thus not pursued further. The number of trajectories that best fit the data was determined using several statistics: relatively lower Akaike’s Information Criterion, nonsignificant likelihood ratio test, relatively higher entropy value, and meaningfully large class sizes N ≥ 50. To assess associations between tobacco trajectory class and participant characteristics, we conducted bivariate analyses to explore first subgroup differences and then multinomial logistic regressions to more robustly test correlates of trajectory class membership.

We conducted the GMM analysis using Mplus 8.0 using Full Information Maximum Likelihood estimation (Los Angeles, CA). Using SAS v. 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC), data cleaning (ie, identifying incomplete or nonsensical data; modifying or correcting data) was done, and then post-GMM multinomial regression analyses were conducted.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Of the 2952 participants included in these analyses, 64.5% were female, 91.7% heterosexual, 65.0% white, and 7.8% Hispanic; 83.0% had parents with bachelor’s degrees or more education (Table 1). Regarding baseline substance use, earlier onset use of cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana was reported by 10.5%, 33.9%, and 29.1%, respectively. Past 30-day use was as follows: cigarettes 9.8%, LCCs 10.2%, SLT 3.4%, ENDS 10.3%, hookah 11.4%, alcohol 62.5%, and marijuana 22.5%. Regarding interpersonal factors, parental tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use was reported by 32.3%, 55.7%, and 6.3%, respectively. In terms of community settings, the majority attended private or public colleges/universities (41.7% and 27.8%, respectively), 58.4% resided in rural settings.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics and Bivariate Analyses Examining Differences Among Tobacco Use Trajectories, n = 2952

| Variable | Total sample, n = 2952 | Abstainers/Dabblers, n = 2703 | Adult users, n = 124 | College users, n = 73 | Teenage users, n = 52 | p a | p b | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n or M | % or SD | n or M | % or SD | n or M | % or SD | n or M | % or SD | n or M | % or SD | |||

| Intrapersonal factors | ||||||||||||

| Sociodemographics | ||||||||||||

| Gender (N, %) | <.001 | .028 | ||||||||||

| Male | 1047 | 35.5 | 911 | 33.7 | 74 | 59.7 | 42 | 58.3 | 20 | 38.5 | ||

| Female | 1901 | 64.5 | 1789 | 66.3 | 50 | 40.3 | 30 | 41.7 | 32 | 61.5 | ||

| Sexual orientation (N, %) | .004 | .097 | ||||||||||

| Heterosexual | 2683 | 91.7 | 2466 | 92.1 | 114 | 91.9 | 59 | 81.9 | 44 | 84.6 | ||

| Not heterosexual | 242 | 8.3 | 211 | 7.9 | 10 | 8.1 | 13 | 18.1 | 8 | 15.4 | ||

| Race (N, %) | .191 | .687 | ||||||||||

| White | 1895 | 65.0 | 1719 | 64.4 | 91 | 74.6 | 50 | 70.2 | 35 | 67.3 | ||

| Asian | 190 | 6.5 | 179 | 6.7 | 4 | 3.3 | 10 | 14.1 | 12 | 23.1 | ||

| Black | 660 | 22.6 | 620 | 23.2 | 18 | 14.8 | 5 | 7.0 | 2 | 3.9 | ||

| Other | 170 | 5.8 | 152 | 5.7 | 9 | 7.4 | 6 | 8.5 | 3 | 5.8 | ||

| Hispanic ethnicity (N, %) | 229 | 7.8 | 210 | 7.8 | 11 | 8.9 | 5 | 6.9 | 3 | 5.8 | .903 | .751 |

| Parental education (N, %) | ||||||||||||

| <Bachelor’s | 495 | 17.0 | 458 | 17.2 | 12 | 9.8 | 17 | 23.3 | 8 | 15.4 | ||

| ≥Bachelor’s | 2420 | 83.0 | 2209 | 82.8 | 111 | 90.2 | 56 | 76.7 | 44 | 84.6 | .079 | .037 |

| Psychosocial factors | ||||||||||||

| Adverse childhood events (M, SD) | 1.32 | 1.82 | 1.29 | 1.80 | 1.36 | 1.74 | 1.95 | 2.05 | 1.82 | 2.32 | .004c | .096 |

| Depressive symptoms (M, SD) | 6.24 | 5.26 | 6.16 | 5.22 | 6.54 | 5.51 | 7.25 | 5.55 | 8.35 | 6.00 | .007c | .150 |

| ADHD symptoms (M, SD) | 9.52 | 4.36 | 9.50 | 4.37 | 10.02 | 3.84 | 9.26 | 4.32 | 9.92 | 5.09 | .491 | .471 |

| Earlier onset substance use (N, %) | ||||||||||||

| Cigarette use (≤16) | 309 | 10.5 | 249 | 9.2 | 27 | 21.8 | 23 | 31.5 | 10 | 19.2 | <.001 | .199 |

| Alcohol use (≤16) | 988 | 33.9 | 868 | 32.5 | 67 | 55.5 | 36 | 49.3 | 17 | 33.3 | <.001 | .039 |

| Marijuana use (≤18) | 840 | 29.1 | 708 | 26.8 | 67 | 55.9 | 39 | 53.4 | 26 | 51.0 | <.001 | .893 |

| Baseline past 30-day use (N, %) | ||||||||||||

| Cigarettes | 290 | 9.8 | 204 | 7.6 | 42 | 33.9 | 41 | 56.2 | 3 | 5.8 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Little cigars and cigarillos | 300 | 10.2 | 236 | 8.7 | 33 | 26.6 | 21 | 28.8 | 10 | 19.2 | <.001 | .460 |

| Smokeless tobacco | 100 | 3.4 | 68 | 2.5 | 20 | 16.1 | 8 | 11.0 | 4 | 7.7 | <.001 | .265 |

| Electronic cigarettes | 305 | 10.3 | 228 | 8.4 | 42 | 33.9 | 23 | 31.5 | 12 | 23.1 | <.001 | .365 |

| Hookah | 336 | 11.4 | 282 | 10.4 | 30 | 24.2 | 16 | 21.9 | 8 | 15.4 | <.001 | .432 |

| Alcohol | 1846 | 62.5 | 1648 | 61.0 | 99 | 79.8 | 65 | 89.0 | 34 | 65.4 | <.001 | .005 |

| Marijuana | 665 | 22.5 | 441 | 16.32 | 45 | 36.3 | 27 | 37.0 | 13 | 25.0 | <.001 | .294 |

| Number of products ever used (M, SD) | 1.82 | 2.00 | 1.61 | 1.87 | 4.19 | 1.90 | 4.22 | 1.93 | 2.40 | 1.73 | <.001c | <.001 |

| Interpersonal factors | ||||||||||||

| Social support (M, SD) | 36.88 | 5.03 | 36.89 | 5.03 | 37.19 | 4.45 | 36.70 | 5.55 | 35.70 | 5.79 | .345 | .221 |

| Appraisal | 12.03 | 2.01 | 12.04 | 2.01 | 12.01 | 1.74 | 12.11 | 1.96 | 11.71 | 2.33 | .684 | .502 |

| Belonging | 11.39 | 1.82 | 11.40 | 1.82 | 11.45 | 1.70 | 11.24 | 1.97 | 11.18 | 1.80 | .720 | .592 |

| Tangible support | 13.44 | 2.34 | 13.45 | 2.34 | 13.73 | 2.02 | 13.30 | 2.49 | 12.76 | 2.81 | .096 | .046 |

| Parental substance use (N, %) | ||||||||||||

| Tobacco use | 952 | 32.3 | 1851 | 68.5 | 48 | 38.7 | 35 | 48.0 | 17 | 32.7 | .010 | .206 |

| Alcohol use | 1645 | 55.7 | 1498 | 55.4 | 76 | 61.3 | 37 | 50.7 | 34 | 65.4 | .224 | .199 |

| Marijuana use | 185 | 6.3 | 158 | 5.9 | 12 | 9.7 | 13 | 17.8 | 2 | 3.9 | <.001 | .039 |

| Community-level factors | ||||||||||||

| School type (N, %) | <.001 | .001 | ||||||||||

| Private | 1232 | 41.7 | 1131 | 41.8 | 61 | 49.2 | 22 | 30.1 | 18 | 34.6 | ||

| HBCU | 323 | 10.9 | 304 | 11.3 | 6 | 4.8 | 7 | 9.6 | 6 | 11.6 | ||

| Public | 821 | 27.8 | 732 | 27.1 | 46 | 37.1 | 22 | 30.1 | 21 | 40.4 | ||

| Technical | 576 | 19.5 | 536 | 19.8 | 11 | 8.9 | 22 | 30.1 | 7 | 13.5 | ||

| Community type (N, %) | .011 | .004 | ||||||||||

| Urban/suburban | 1229 | 41.6 | 1124 | 41.6 | 64 | 51.6 | 20 | 27.4 | 21 | 40.4 | ||

| Rural | 1723 | 58.4 | 1579 | 58.4 | 60 | 48.4 | 53 | 72.6 | 31 | 59.6 |

a p-values comparing all groups, including abstainers/dabblers.

b p-values comparing user subgroups, excluding abstainers/dabblers.

cOnly significant difference between college users and abstainers/dabblers in relation to adverse childhood events; only significant difference between teenage users and abstainers/dabblers in relation to depressive symptoms; all post hoc tests significant except for comparing college and adult users in relation to the number of products used.

Tobacco Use Trajectories

From age 18 to 26, approximately 27%–31% reported past 30-day use of any tobacco product; however, reports of tobacco use declined after age 26 (Figure 1, A). Using Akaike’s Information Criterion, difference tests, and entropy (Supplementary Table S1), we identified four trajectory classes (Figure 1, B). We labeled the first and largest group (91.6%, n = 2703) the Abstainers/Dabblers—those who did not use tobacco, used it once, or used it intermittently during the study period. (We conducted preliminary analyses to determine the appropriateness of categorizing this group together versus separating abstainers from those who used tobacco only once or a couple of occasions; as no significant differences were found, we made this a single category.) The second group was Adult users (4.2%, n = 124), who began using more frequently around age 20 and continued use into adulthood. The third group was College Smokers (2.5%, n = 73), who began using tobacco before age 19, continued during their college years, and ceased use around 25. The fourth group was Teenage users (1.8%, n = 52), who used tobacco during their teenage years but ceased by 22. The curve for Abstainers/Dabblers indicates that the overall probability increased with age from about 25% to 30% from age 19 to 27. In general, few participants were in groups with trajectories of continuous use of tobacco.

Figure 1.

Percent of participants using tobacco by age and tobacco use trajectories. (A) Percent of participants using tobacco by age. (B) GMM tobacco use trajectories.

We then characterized tobacco use among groups (Table 2). The average number of tobacco products ever used among the groups were Dabblers/Abstainers M = 1.61 (SD = 1.87), Adult users M = 4.19 (SD = 1.90), College users M = 4.22 (SD = 1.93), and Teenage users M = 2.40 (SD = 1.73), indicating higher numbers among Adult users (p < .001), College users (p < .001), and Teenage users (p = .004), compared to Dabblers/Abstainers. Compared to Dabblers/Abstainers, Adult and College users were more likely to report any tobacco product use (and use of each tobacco product) as well as alcohol and marijuana use at W1. Teenage users showed fewer differences, with higher reported rates of use of LCCs (p = .011), SLT (p = .028), and e-cigarettes (p < .001), but no other significant differences.

Table 2.

Tobacco Use Characteristics Among Groups Representing Different Tobacco Use Trajectories (Ref: Abstainers/Dabblers, n = 2323)

| Variable | Adult users | College users | Teenage users | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 124 | n = 73 | n = 52 | ||||||||||

| OR | 95% Wald CI | p | OR | 95% Wald CI | p | OR | 95% Wald CI | p | ||||

| Number tobacco products ever used | 1.73 | 1.59 | 1.89 | <.001 | 1.74 | 1.55 | 1.96 | <.001 | 1.22 | 1.07 | 1.40 | .004 |

| Baseline past 30-day use | ||||||||||||

| Cigarettes | 6.27 | 4.21 | 9.34 | <.001 | 15.70 | 9.68 | 25.47 | <.0001 | 0.75 | 0.23 | 2.43 | .631 |

| LCCs | 3.79 | 2.49 | 5.77 | <.001 | 4.22 | 2.50 | 7.13 | <.0001 | 2.49 | 1.23 | 5.02 | .011 |

| Smokeless tobacco | 7.45 | 4.36 | 12.73 | <.001 | 4.77 | 2.20 | 13.33 | <.0001 | 3.23 | 1.13 | 9.21 | .028 |

| E-cigarettes | 5.56 | 3.74 | 8.26 | <.001 | 4.99 | 2.99 | 8.33 | <.0001 | 3.26 | 1.68 | 6.30 | <.001 |

| Hookah | 2.74 | 1.78 | 4.21 | <.001 | 2.41 | 1.37 | 4.25 | .002 | 1.56 | 0.73 | 3.35 | .253 |

| Alcohol | 2.54 | 1.62 | 3.96 | <.001 | 5.20 | 2.49 | 10.88 | <.0001 | 1.21 | 0.68 | 2.15 | .518 |

| Marijuana | 2.92 | 2.00 | 4.27 | <.001 | 3.01 | 1.85 | 4.90 | <.0001 | 1.71 | 0.91 | 3.23 | .098 |

OR = unadjusted odds ratios.

Predictors of Differing Tobacco Use Trajectories

Bivariate analyses comparing characteristics among all subgroups as well as among the user subgroups only are presented in Table 1. Multinomial regression identifying predictors of class membership (Table 3) showed that predictors of being Adult users (vs. Abstainers/Dabblers) included being male (p < .001), earlier onset marijuana use (p < .001), attending public universities or technical colleges (vs. private universities; p = .041 and p = .006, respectively), and living in an urban setting (p = .014). Predictors of being College users included being male (p < .001), earlier onset marijuana use (p = .006), and parental use of alcohol (p = .035) or marijuana (p = .024). Predictors of being Teenage users included only earlier onset marijuana use (p < .001).

Table 3.

Predictors of Groups With Different Tobacco Use Trajectories (Ref: Abstainers/Dabblers, n = 2425)

| Variable | Adult users | College users | Teenage users | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 113 | n = 65 | n = 49 | ||||||||||

| aOR | 95% Wald CI | p | aOR | 95% Wald CI | p | aOR | 95% Wald CI | p | ||||

| Intrapersonal factors | ||||||||||||

| Sociodemographics | ||||||||||||

| Gender (male = ref.) | 0.35 | 0.23 | 0.54 | <.001 | 0.33 | 0.19 | 0.57 | <.001 | 0.81 | 0.43 | 1.54 | .527 |

| Sexual minority (heterosexual = ref.) | 0.76 | 0.35 | 1.63 | .477 | 1.89 | 0.93 | 3.83 | .077 | 1.81 | 0.80 | 4.09 | .153 |

| Race (white = ref.) | ||||||||||||

| Asian | 0.58 | 0.20 | 1.68 | .311 | 1.05 | 0.34 | 3.29 | .929 | 0.74 | 0.17 | 3.34 | .696 |

| Black | 0.99 | 0.49 | 1.97 | .966 | 0.37 | 0.12 | 1.17 | .091 | 0.70 | 0.26 | 1.89 | .483 |

| Other | 1.29 | 0.58 | 2.87 | .530 | 1.16 | 0.41 | 3.29 | .776 | 1.20 | 0.33 | 4.38 | .786 |

| Hispanic (no = ref.) | 1.02 | 0.48 | 2.17 | .950 | 0.80 | 0.26 | 2.47 | .696 | 0.62 | 0.16 | 2.31 | .472 |

| Parental education (<Bachelor’s = ref.) | 1.68 | 0.84 | 3.35 | .143 | 0.89 | 0.47 | 1.71 | .731 | 1.04 | 0.46 | 2.34 | .924 |

| Psychosocial factors | ||||||||||||

| Adverse childhood events | 0.98 | 0.87 | 1.11 | .742 | 1.08 | 0.94 | 1.23 | .277 | 1.09 | 0.94 | 1.26 | .266 |

| Depression | 1.01 | 0.97 | 1.06 | .499 | 1.04 | 0.99 | 1.09 | .157 | 1.05 | 1.00 | 1.11 | .052 |

| ADHD symptoms | 1.00 | 0.95 | 1.05 | .996 | 0.96 | 0.90 | 1.01 | .130 | 0.98 | 0.92 | 1.05 | .552 |

| Earlier onset substance use | ||||||||||||

| Cigarette use (≤16) | 1.41 | 0.80 | 2.46 | .233 | 1.82 | 0.92 | 3.61 | .084 | 1.32 | 0.55 | 3.18 | .541 |

| Alcohol use (≤16) | 1.62 | 1.02 | 2.56 | .042 | 0.98 | 0.53 | 1.80 | .938 | 0.52 | 0.25 | 1.05 | .068 |

| Marijuana use (≤18) | 2.48 | 1.57 | 3.93 | <.001 | 2.31 | 1.27 | 4.21 | .006 | 3.18 | 1.66 | 6.09 | <.001 |

| Interpersonal factors | ||||||||||||

| Social support | 1.02 | 0.98 | 1.06 | .422 | 1.03 | 0.98 | 1.09 | .260 | 0.98 | 0.92 | 1.03 | .397 |

| Parental substance use | ||||||||||||

| Tobacco use | 1.12 | 0.71 | 1.74 | .633 | 1.29 | 0.73 | 2.29 | .388 | 0.91 | 0.47 | 1.74 | .766 |

| Alcohol use | 0.85 | 0.56 | 1.29 | .444 | 0.56 | 0.33 | 0.96 | .035 | 1.44 | 0.77 | 2.71 | .257 |

| Marijuana use | 1.84 | 0.91 | 3.73 | .090 | 2.41 | 1.12 | 5.18 | .024 | 0.40 | 0.09 | 1.80 | .233 |

| Community-level factors | ||||||||||||

| School type (private = ref.) | ||||||||||||

| HBCU | 1.11 | 0.30 | 4.17 | .874 | 1.60 | 0.43 | 5.97 | .484 | 1.68 | 0.40 | 7.00 | .475 |

| Public | 2.21 | 1.03 | 4.74 | .041 | 0.55 | 0.25 | 1.21 | .139 | 1.14 | 0.41 | 3.16 | .798 |

| Technical | 2.80 | 1.34 | 5.84 | .006 | 0.70 | 0.35 | 1.42 | .325 | 2.17 | 0.86 | 5.46 | .101 |

| Rural (urban = ref.) | 0.58 | 0.37 | 0.89 | .014 | 1.41 | 0.76 | 2.62 | .278 | 0.91 | 0.47 | 1.78 | .782 |

aOR = adjusted odds ratios.

Social support was modeled with the full score as neither full nor component scores were significantly related to the trajectory.

Discussion

Current findings extend the literature regarding young adult tobacco use trajectories. Trajectories resembling those previously documented were identified.10,11,29 One group represented those using tobacco during the teenage years and reducing or ceasing early in their college years (Teenage users, 1.9%). Another group represented those using tobacco before age 19, through their college years, and ceasing around age 25 (College Smokers, 2.5%). Unfortunately, the largest tobacco use group included those who began using more frequently around age 20 and continued use regularly into adulthood (Adult users, 5.9%). Not surprisingly, Dabblers/Abstainers and Teenage users reported lower numbers of products ever used on average (1–2.5 products), with College and Adult users having at least tried more on average (4–5 products). Also unsurprisingly, compared to Dabblers/Abstainers, College and Adult users were more likely to report any tobacco product use (and use of each tobacco product) as well as alcohol and marijuana use at baseline, with Teenage users showing fewer differences compared to Abstainers/Dabblers.

Leveraging a socioecological perspective,14 we documented differences in these groups across individual-, interpersonal-, and community-level factors. Compared to Abstainers/Dabblers, several important predictors were found, particularly identifying Adult and College users but to a far lesser extent identifying Teenage users. Marijuana use was a factor that distinguished all three tobacco use trajectories. Specifically, earlier onset marijuana use predicted being Adult, College, and Teenage users. Thus, marijuana use in adolescent years may be the most critical indicator of future risk for tobacco use, continued use, and potential dependence. Males were more likely to be Adult and College users, but not Teenage users. This aligns with prior research, indicating that males are at greater risk of tobacco use progression.10,13,16,17 The fact that being male predicted the later escalation categories but not the category of users at least risk also coincides with this literature.

Three predictors distinguished Adult users (ie, college type, rural/urban) and College users (parental substance use). Adult users more likely attended public universities or technical colleges (vs. private universities) and live in urban settings. In relation to the former, note that we considered including other campus attributes including the time of tobacco-free campus implementation or baseline campus prevalence of smoking. However, these were highly related to school type. Because campus type has been robustly associated with tobacco use,41 we retained school type rather than the others. Regardless of the tobacco control context, tobacco-free policies may have less impact on technical colleges, as these campuses are smaller so students can more easily get off campus to smoke and may also spend less time on campus than traditional college students. Perhaps along these lines, rural areas often have fewer smoke-free policies and higher smoking prevalence. These structural factors may play critical roles in making tobacco use normative and facilitating long-term use and eventual dependence.

Predictors of being College users included parental alcohol or marijuana use, as the literature10,29,33 and our prior research examining cigarette smoking in this sample13 would suggest. However, parental alcohol or marijuana use did not predict Teenage use or Adult use trajectories, and parental tobacco use did not predict tobacco use trajectories. This may reflect the fact that Teenage users resembled Abstainers/Dabblers in terms of their overall risk and risk profile and thus may not have been exposed to parental substance use at significant levels. Moreover, perhaps Adult users are less influenced by parental use behaviors, as their use escalated at times that likely involved less parental influence. Finally, parental tobacco use was most likely to be cigarette smoking, so parental tobacco use may not influence other tobacco product use. This is likely the case, given that parental tobacco use was found to be related to cigarette smoking early in the college years in our prior research.13

Several nonsignificant findings were identified that were not anticipated based on the literature. For example, race, parental education, symptoms of depression or ADHD, ACEs, and social support were not significant predictors of any tobacco use categories. The reasons for these nonsignificant findings are unclear. One reason may be the small numbers (ie, low statistical power) included in the three user categories, particularly the Teenage user and College user categories. This may have limited power to adequately test and detect some potentially significant associations. The literature suggests that being white or Asian would predict college onset smoking13,16,17 and that blacks would show an escalation in the later 20s.10,18,19 This might reflect the fact that different races and ethnicities are at higher risk for using different tobacco products.42 In addition, parental education may be a less robust predictor among college students. Regarding mental health-related factors, these nonsignificant findings may reflect the fact that this college student sample may not have had the level of ACEs or mental health symptoms that would represent the broader young adult population and that social support may be differentially experienced, and thus reported, among young adults.

Study findings have implications for research and practice. Collectively, these findings suggest that traditional predictors of smoking uptake in young adulthood, as documented in the literature, are not particularly relevant when considering the broader array of tobacco products in the current market. Additional research is needed to better understand risk factors for using these ATPs over time and the distinct trajectories. Moreover, it is particularly important to identify predictors of Adult use, as this group represented the highest risk for tobacco-related morbidity and mortality. Other life course factors specific to this time period need further examination. For instance, the research could assess factors related to transiting out of the college years, developing independence, educational and career advancement, and establishing stable relationships (eg, marriage, parenting). This is particularly relevant as transitions to more conventional social roles (eg, work, marriage) in young adulthood predict cessation of risky behaviors, including tobacco use.17 Future research should also assess a broader range of socio-contextual factors (eg, smoking prevalence, social norms, smoke-free air policies) that might influence tobacco use during this time. Qualitative research is also needed to examine how the different ATPs are used and perceived over time among young adults, which are more prevalent over time, and which are the most notable markers for continued or long-term use. In practice, more progressive policies are needed to decrease access to tobacco and other substances among young adults, particularly policies relevant to ATP use such as excise taxes on ATPs and smoke-free air policies that include ATPs. Campus-based services must systematically assess the use of the broad range of substances used by college students and provide appropriate intervention.

Limitations

This study has some notable limitations. First, given the small proportions of participants indicating the use of some ATPs (eg, SLT), we were not able to model use trajectories of each of the ATPs; however, our previous research did examine cigarette smoking trajectories,13 to which we were able to compare current results. Second, this sample included some small trajectory classes, which indicates the need for replication in larger sample sizes with greater representation of certain classes. Third, our measures did not exhaustively assess other psychological characteristics (eg, anxiety). Fourth, our analyses did not consider any interactions across levels of influence due to the large number of predictors included in these analyses (and thus limited power to test for interactions); the small sample sizes in some of the groups identified also limited power to detect significant results. Fifth, the sample was drawn from colleges/universities in Georgia and may have limited generalizability. However, it should be noted our sample is diverse in terms of race/ethnicity, geographic location (urban vs. rural), school types, and socioeconomic backgrounds. We also did not have access to exact sociodemographics of the student populations at each college/university nor the specific sociodemographics of the students represented by each e-mail address provided by registrars. Thus, we were not able to examine statistically questions of selection bias. However, the sample derived at each school was representative of the aggregate data on the student populations regarding race and ethnicity but not sex; other data (eg, age, socioeconomic status) of the student populations were not available. In addition, all waves of data collection were completed by 2403 participants (70.3% of the baseline sample); however, we conducted the GMM analysis using Full Information Maximum Likelihood estimation, which allowed modeling on a larger sample (n = 2952) including participants with some missing data. Finally, these analyses are limited by the self-report nature of the assessments.

Conclusions

Three distinct trajectories of young adult tobacco use were identified, including Teenage, College, and Adult users, with the latter demonstrating the greatest overall tobacco-related risks. Of particular importance is that, while some anticipated factors distinguished the tobacco use categories (eg, being male, earlier marijuana use), few others predicted being in one of the tobacco user groups, and some predictors were specific to the distinct user groups. Thus, more research is needed to identify risk factors for using the broad range of tobacco products, particularly during the different eras of adolescence and young adulthood.

Supplementary Material

A Contributorship Form detailing each author’s specific involvement with this content, as well as any supplementary data, is available online at https://academic.oup.com/ntr.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our Campus Advisory Board members across the state of Georgia in developing and assisting in administering this survey. We also would like to thank ICF Macro for their scientific input and technical support in conducting this research.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (R01CA179422-01; PI: Berg). Dr Berg is also supported by other NCI funding (R01CA215155-01A1; PI: Berg; R01CA239178-01A1; MPIs: Berg, Levine), the US Fogarty International Center/National Cancer Institute (R01TW010664-01; MPIs: Berg, Kegler), and the NIEHS/Fogarty (D43ES030927-01; MPIs: Berg, Marsit, Sturua). The funders had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Harrell PT, Naqvi SMH, Plunk AD, Ji M, Martins SS. Patterns of youth tobacco and polytobacco usage: the shift to alternative tobacco products. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2017;43(6):694–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wang TW, Gentzke A, Sharapova S, Cullen KA, Ambrose BK, Jamal A. Tobacco product use among middle and high school students—United States, 2011–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(22):629–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wang TW, Asman K, Gentzke AS, et al. Tobacco product use among adults—United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(44):1225–1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lisha NE, Thrul J, Ling PM. Latent class analysis to examine patterns of smoking and other tobacco products in young adult bar patrons. J Adolesc Health. 2019;64(1):93–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Haardörfer R, Berg CJ, Lewis M, et al. Polytobacco, marijuana, and alcohol use patterns in college students: a latent class analysis. Addict Behav. 2016;59:58–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Evans-Polce R, Lanza S, Maggs J. Heterogeneity of alcohol, tobacco, and other substance use behaviors in U.S. college students: a latent class analysis. Addict Behav. 2016;53:80–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Johnston L, O’Malley P, Bachman J, Schulenberg J, Miech R.. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2013. Volume II: College Students and Adults Ages 19–55. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Park E, McCoy TP, Erausquin JT, Bartlett R. Trajectories of risk behaviors across adolescence and young adulthood: the role of race and ethnicity. Addict Behav. 2018;76:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dutra LM, Glantz SA, Lisha NE, Song AV. Beyond experimentation: five trajectories of cigarette smoking in a longitudinal sample of youth. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):e0171808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hair E, Bennett M, Williams V, et al. Progression to established patterns of cigarette smoking among young adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;177:77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schweizer CA, Roesch SC, Khoddam R, Doran N, Myers MG. Examining the stability of young-adult alcohol and tobacco co-use: a latent transition analysis. Addict Res Theory. 2014;22(4):325– 335. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Berg CJ, Romero DR, Pulvers K. Perceived harm of tobacco products and individual schemas of a smoker in relation to change in tobacco product use over one year among young adults. Subst Use Misuse. 2015;50(1):90–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Berg CJ, Haardörfer R, Vu M, et al. Cigarette use trajectories in young adults: analyses of predictors across system levels. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;188:281–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(4):351–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31(2):143–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chen P, Jacobson KC. Developmental trajectories of substance use from early adolescence to young adulthood: gender and racial/ethnic differences. J Adolesc Health. 2012;50(2):154–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mendel JR, Berg CJ, Windle RC, Windle M. Predicting young adulthood smoking among adolescent smokers and nonsmokers. Am J Health Behav. 2012;36(4):542–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Watt TT. The race/ethnic age crossover effect in drug use and heavy drinking. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2008;7(1):93–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Keyes KM, Vo T, Wall MM, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in use of alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana: is there a cross-over from adolescence to adulthood? Soc Sci Med. 2015;124:132–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ford ES, Anda RF, Edwards VJ, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and smoking status in five states. Prev Med. 2011;53(3):188–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Windle M, Mason WA. General and specific predictors of behavioral and emotional problems among adolescents. J Emot Behav Disord. 2004;12(1):49–61. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fluharty M, Taylor AE, Grabski M, Munafò MR. The association of cigarette smoking with depression and anxiety: a systematic review. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017;19(1):3–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chaiton MO, Cohen JE, O’Loughlin J, Rehm J. A systematic review of longitudinal studies on the association between depression and smoking in adolescents. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pal A, Balhara YP. A review of impact of tobacco use on patients with co-occurring psychiatric disorders. Tob Use Insights. 2016;9:7–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Elkins IJ, Saunders GRB, Malone SM, et al. Increased risk of smoking in female adolescents who had childhood ADHD. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(1):63–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sterling K, Berg CJ, Thomas AN, Glantz SA, Ahluwalia JS. Factors associated with small cigar use among college students. Am J Health Behav. 2013;37(3):325–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Heinz AJ, Giedgowd GE, Crane NA, et al. A comprehensive examination of hookah smoking in college students: use patterns and contexts, social norms and attitudes, harm perception, psychological correlates and co-occurring substance use. Addict Behav. 2013;38(11):2751–2760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Goodwin RD, Grinberg A, Shapiro J, et al. Hookah use among college students: prevalence, drug use, and mental health. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;141:16–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fuemmeler B, Lee CT, Ranby KW, et al. Individual- and community-level correlates of cigarette-smoking trajectories from age 13 to 32 in a U.S. population-based sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132(1–2):301–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bierhoff J, Haardörfer R, Windle M, Berg CJ. Psychological risk factors for alcohol, cannabis, and various tobacco use among young adults: a longitudinal analysis. Subst Use Misuse. 2019;54(8):1365–1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Behavioral Health Trends in the United States: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2015. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FRR1-2014/NSDUH-FRR1-2014.pdf. Accessed June 11, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ramo DE, Liu H, Prochaska JJ. Tobacco and marijuana use among adolescents and young adults: a systematic review of their co-use. Clin Psychol Rev. 2012;32(2):105–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mays D, Gilman SE, Rende R, Luta G, Tercyak KP, Niaura RS. Parental smoking exposure and adolescent smoking trajectories. Pediatrics. 2014;133(6):983–991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rose JS, Lee CT, Dierker LC, Selya AS, Mermelstein RJ. Adolescent nicotine dependence symptom profiles and risk for future daily smoking. Addict Behav. 2012;37(10):1093–1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhan W, Dierker LC, Rose JS, Selya A, Mermelstein RJ. The natural course of nicotine dependence symptoms among adolescent smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14(12):1445–1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Richardson A, Williams V, Rath J, Villanti AC, Vallone D. The next generation of users: prevalence and longitudinal patterns of tobacco use among US young adults. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(8):1429–1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fagerström K, Eissenberg T. Dependence on tobacco and nicotine products: a case for product-specific assessment. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14(11):1382–1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Etter JF, Eissenberg T. Dependence levels in users of electronic cigarettes, nicotine gums and tobacco cigarettes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;147:68–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Berg C, Choi WS, Kaur H, Nollen N, Ahluwalia JS. The roles of parenting, church attendance, and depression in adolescent smoking. J Community Health. 2009;34(1):56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Flay BR, Petraitis J, Hu FB. Psychosocial risk and protective factors for adolescent tobacco use. Nicotine Tob Res. 1999;1(suppl 1):S59–S65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Berg CJ, An LC, Thomas JL, et al. Smoking patterns, attitudes and motives: unique characteristics among 2-year versus 4-year college students. Health Educ Res. 2011;26(4):614–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Berg CJ, Haardörfer R, Lewis M, et al. DECOY: Documenting Experiences with Cigarettes and Other tobacco in Young adults. Am J Health Behav. 2016;40(3):310–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41(11):1284–1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kessler RC, Adler L, Ames M, et al. The World Health Organization Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS): a short screening scale for use in the general population. Psychol Med. 2005;35(2):245–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. National Survey on Drug Use or Health. Results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (slide 14). National Survey on Drug Use or Health https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/2016_ffr_3_slideshow_v4.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed September 1, 2019.

- 47. Cohen S, Mermelstein R, Kamarck T, Hoberman H. Measuring the functional components of social support. In: Sarason IG, Sarason BR, eds. Social Support: Theory, Research, and Applications. The Hague, Netherlands: Martinus Niijhoff; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Berg CJ, Stratton E, Schauer GL, et al. Perceived harm, addictiveness, and social acceptability of tobacco products and marijuana among young adults: marijuana, hookah, and electronic cigarettes win. Subst Use Misuse. 2015;50(1):79–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Muthén LK, Muthén BO.. Mplus User’s Guide. 7th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Authors; 1998–2012. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.