Abstract

Emergency medicine (EM) in most of Europe is a much newer specialty than in the United States. Until recently, emergency departments (EDs) in Norway were staffed with unsupervised interns, leading to a government report in 2008 that called for change. From the establishment of the Norwegian Society for Emergency Medicine in 2010 to the creation of the specialty in 2017 and the approval of the first emergency physician in Norway in 2019, our review article describes how a small group of physicians were able to work with politicians and the media to get an emergency medicine specialty approved despite resistance from a much larger group of existing specialists. Norway faced many of the same obstacles as the United States did with implementing the specialty 60 years ago. This article serves as a review of the conflict that may ensue when enacting a change in public policy and a resource to those countries that have yet to implement an emergency medicine specialty.

Keywords: efficacy, emergency medicine development, NORSEM, Norway, Norwegian Society for Emergency Medicine, specialty implementation

1. INTRODUCTION

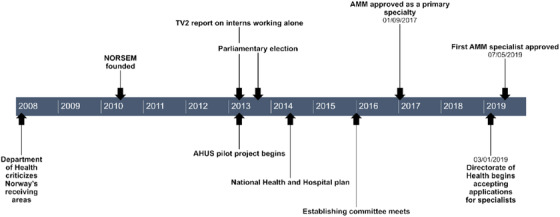

The efficacy of an emergency medicine specialty is well established. 1 Although emergency medicine has been recognized as an independent medical specialty for over half a century in the United States 2 , 3 and the United Kingdom 4 , 5 and since 1984 in Australia, 6 the specialty is a much newer concept in Europe. 4 , 7 The European Society of Emergency Medicine (EuSEM) was founded in 1994 and administered its first European Board Examination in Emergency Medicine (EBEEM) in 2013. 8 When it comes to Scandinavia, Iceland was extremely early in implementing emergency medicine as a primary medical specialty in 1992, 9 followed by Sweden in 2012 10 and Finland in 2013. 11 Denmark and Norway lagged behind. 12 In January 2017, however, the Norwegian Minister of Health declared emergency medicine a primary specialty. In this paper, we provide an account of the development of emergency medicine in Norway. See Figure 1 for an overview.

FIGURE 1.

Emergency Medicine in Norway Timeline

2. BACKGROUND

Norway has a population of 5.4 million and a gross domestic product of approximately $400 billion US dollars (or $75,000 per capita), making it the fourth wealthiest country in the world today. 13 , 14 Its government is a parliamentary representative democratic constitutional monarchy. Like other Nordic countries, Norway has a free market economy with a strong welfare system. It has one of the world's best healthcare systems, with universal health insurance and a well‐organized primary care system that functions as a gatekeeper to specialty care. Patients who require inpatient treatment are referred to the hospital's akuttmottak or “acute receiving area” where patients would be processed for admission by an intern. The primary care physician (PCP) or legevakt, which means “doctor on call,” is required to refer patients to a specialty service at the hospital, such as medicine, surgery, orthopedics, neurology, gynecology, psychiatry, or pediatrics. Approximately 30% of patients arrive by ambulance, where out‐of‐hospital personnel determine the specialty service. Problems arise when patients are referred to the wrong specialty, such as an abdominal aortic aneurysm with back pain being referred to orthopedics; when patients have problems that span different specialties, such as a patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with respiratory distress referred to surgery for a bowel obstruction; or when a patient has nonspecific symptoms such as dizziness. Acute receiving areas are primarily staffed by nurses and resident physicians with an average of 6 months experience.

In 2007, the Norwegian Department of Health (Helsetilsynet) performed an assessment of half of Norway's 54 acute receiving areas, and in 2008, published their report “While we are waiting….” 15 There were many criticisms, but attention was drawn to unsupervised interns in the acute receiving areas and a failure in leadership. This started the debate in Norway regarding how to best rectify these problems.

The Norwegian Society for Emergency Medicine (NORSEM) was established in 2010 by Lars Petter Bjørnssen, a Norwegian physician who completed his residency training in emergency medicine in the United States. With the motto “knowledge saves lives,” the goal of this organization was to improve emergency medicine knowledge for better patient care and to promote the concept of emergency medicine as a primary specialty. Annual conferences were held through 2016. In 2013, NORSEM petitioned the national doctor's union, Den Norske Legeforening (DNLF), to be recognized as a specialist union. This was met with little to no resistance from other specialist unions. 16 NORSEM also coordinated a letter writing campaign, receiving attestations from the International Federation of Emergency Medicine (IFEM), the EuSEM, Iceland, Sweden, and Denmark regarding the importance of a primary specialty in emergency medicine. In 2018, NORSEM became a full voting member of IFEM.

In early April 2013, one of Norway's national television stations, TV2, reported on the situation with inexperienced interns working alone in the country's receiving areas. The investigating reporters had telephoned all of the receiving areas and discovered that 80% of the time, patients were first seen by interns, out of medical school only 5 months on average. More frighteningly, 71% of these interns were on call alone during the evenings and nights, with supervision available only by telephone. They also reported on a hospital that was trying to change this by placing experienced physicians up front to be the first to see patients as they arrive in the receiving area. 17

Simultaneously, the Icelandic chief executive officer (CEO) at Norway's largest acute receiving area, Akershus University Hospital (AHUS), which had the worst reputation for patient complaints and adverse events, started a pilot project modeled after the US/UK/Australian model of staffing the medical receiving area with supervising physicians in an attempt to improve the quality of care. This project was led by Kåre Løvstakken, a Norwegian anesthesiologist with emergency and retrieval experience from Australia. Nine attending physicians from various specialties, including 3 American‐trained emergency physicians, 3 Norwegian internists, a pediatrician, an anesthesiologist, and a surgeon, began to work in the medical division of the receiving area. From day 1, the media was invited to document this project. By the summer of 2013, the project was in full swing with decreased wait times, decreased patient complaints to the ombudsman, and no unexpected deaths. This pilot project was featured on a national television documentary series on the Norwegian healthcare system, “På Liv og Død” (of Life and Death).

This project was not without conflict, however. It was started as an initiative from the hospital's highest leadership (CEO and medical division director) without buy‐in from other specialists. Furthermore, it pertained only to the medical acute receiving area, which was under the leadership of the medicine department, rather than being an independent department. Turf battles ensued. Although attending cardiologists did not want to come down to the acute receiving area to treat patients, they did not want other attending physicians to treat cardiac patients there either. They did not understand the scope of practice of foreign‐trained emergency physicians whose specialty was not yet recognized in Norway. Anesthesiologists argued that only they were trained to evaluate and manage the most acutely ill medical and trauma patients. However, these “blue‐light” patients accounted for only 3% of patients presenting to the receiving area. Additionally, anesthesia insisted that only they could perform intubation and procedural sedation. In October 2013, the CEO was forced out because of a nursing staffing conflict. The acting CEO required the approval of the majority of the medical staff to become the new CEO. However, the vast majority of the medical staff were against the emergency medicine pilot project. What ensued was a reorganization of the receiving area. If there was a disagreement between the emergency physician at the bedside and the specialist upstairs or taking call from home, the authority was given to the recognized specialist rather than the emergency physician. The nurses who staffed the receiving area held a meeting with the hospital's leadership and wrote a letter to protest. They supported having their own attending physicians in the receiving area and had noted a marked improvement in patient safety since the pilot project was started. This fell on deaf ears. By the end of March 2014, after only 1 year, the project was dismantled. 18

2013 also happened to be a parliamentary election year in Norway. Rather than relying on DNLF to approve a new specialty, which seemed unlikely, or creating emergency medicine as a subspecialty of internal medicine, as Sweden had done with little success, the project leader at AHUS chose to bet on a political strategy instead. Politicians, including the future minister of health, the woman who would become chair of the Norwegian National Healthcare Committee, local politicians, and the patient care advocate for the Directorate of Health all visited AHUS. One prominent political leader donned hospital scrubs and observed during a shift in AHUS's receiving area. This was strategically documented by the media. The politicians, patient care advocate, and media all had the common goal of improved emergency care in Norway's receiving areas. Seven of the 9 political parties that won seats in parliament that year pledged their support for a new emergency medicine specialty.

In September 2014, the same leader of the Healthcare Committee who had visited AHUS took the committee to Australia to learn about emergency medicine from a country with a proven track record in this specialty. Now that they had seen firsthand how an emergency medicine specialty could function, opponents had difficulty with their argumentation. Later that year, the Norwegian government prepared the National Health and Hospital Plan and committed to create a new physician specialty geared toward hospitals’ acute receiving areas. 19 An emergency medicine specialty was now written in stone, so to speak. Early in 2015, the Directorate of Health met with stakeholders including internists and NORSEM to develop a new specialty that (1) would apply to all hospitals, regardless of the size; (2) would include observation medicine for the largest hospitals; and (3) be able to take inpatient calls at the small hospitals. 20

3. BARRIERS TO AN EMERGENCY MEDICINE SPECIALTY

In mid‐2015, Dagens Medisin, a Norwegian online medical forum, published back‐to‐back debates. First, an article, “We do not need an emergency medicine specialty,” was written by a group of anesthesiologists. 21 They argued that anesthesiologists already competently manage critically ill patients in both the out‐of‐hospital setting and in the receiving area and proposed that Norway should use the specialties that already exist and send the attending physicians down to the receiving area to supervise the residents on their service. Furthermore, they pointed to problems that Sweden and Denmark had with recruiting and retaining physicians in a new emergency medicine specialty. The following week, “We need a new emergency medicine specialty” was published. 22 This was written by the board members of NORSEM and argued that emergency medicine was more than the critically ill “blue‐light” patients that anesthesia had described. The other 97% of patients were being managed by unsupervised residents with very little clinical experience. And although up to 66% of patients in the receiving area are internal medicine patients, up to 70% of patients present with undifferentiated symptoms, making it sometimes difficult to determine the appropriate specialty upon presentation. NORSEM supported a new specialty that would be in line with IFEM's definition that “emergency medicine is a field of practice based on knowledge and skills required for the prevention, diagnosis and management of acute and urgent aspects of illness and injury affecting patients of all age groups with a full spectrum of episodic undifferentiated physical and behavioral disorders.” 23

A similar debate later took place in the Norwegian doctors union publication, with an anesthesiologist claiming that emergency physicians are not needed in Norway because patients are initially evaluated by their PCP or legevakt, 24 and NORSEM leadership pointing out the importance of having a regular group of emergency physicians in the receiving area who have a broad knowledge base that is based on EuSEM's curriculum. 25

Also in 2015, while the debate was raging in the media, a working group of 9 physicians, with backgrounds from internal medicine, emergency medicine, anesthesia, surgery, and radiology, was established to develop the framework of the new specialty. The leader of this group was an internal medicine specialist from Oslo who lobbied for an acute internal medicine specialty, Mottaks‐ og Indremedisin (MIM). It was noted that there was strong disagreement within this group regarding the specialty. The NORSEM members wanted an internationally recognized EM specialty that included pediatrics, otolaryngology, obstetrics and gynecology, ophthalmology, and dermatology, Akutt‐ og Mottaksmedisin (AMM), whereas the internal medicine specialists wanted MIM. It was agreed that the new specialty would not involve out‐of‐hospital care nor critically ill trauma, stroke, and acute myocardial infarction patients, as these groups were already adequately managed by anesthesia, who already referred to themselves as emergency physicians. This group met several times over the latter half of 2015 but could not agree on the 2 different possibilities (AMM or MIM). A new group was created by the Directorate of Health and eventually created the curriculum based on that of EuSEM, with some features unique to Norway, such as being able to take internal medicine calls at smaller hospitals. Overall, EuSEM's curriculum is virtually identical to that of the American, British, and Australian models.

The vast majority (95%) of physicians in Norway belong to the Norwegian Physicians Union, Den Norske Legeforening (DNLF). In 2016, DNLF opened a hearing period and requested that each specialty union submit their opinions on a new EM specialty. None of the specialty unions were supportive of a new emergency medicine specialty. 16 The existing specialists argued that the curriculum was too broad and that they were already most capable of treating patients who pertained to their particular specialty. Pediatrics and neurology were supportive of a new specialty, as long as it pertained to internal medicine.

4. LESSONS LEARNED

It came as no surprise that trying to establish a new specialty would be met with resistance from existing specialists. Although the pilot project at AHUS blended specialists from abroad with local physicians from a variety of specialties, the group was still viewed as outsiders. It was unfortunate that the pilot project was initiated from the top without buy‐in from the existing specialists, but this would have been unlikely to happen regardless, and time was of the essence to make a radical change to prevent mortality and morbidity in Norway's largest receiving area. In addition, the pilot project was under the division of internal medicine, rather than its own department. It would have been ideal to start as its own department, but that was not possible. The pilot project would have more likely been sustainable had the Icelandic CEO behind the project remained in her position. Her departure was an unfortunate turn of events that could not have been predicted. Despite these obstacles, an emergency medicine specialty in Norway was bound to occur eventually. Norway was one of the last remaining countries in Europe and Scandinavia without the specialty. The framework had already been laid with the formation of NORSEM several years prior. In addition, many other countries and IFEM were able to encourage the Norwegian government by sharing their past successes with an emergency medicine specialty. Furthermore, those who fought for the specialty were able to demonstrate that they acted in the best interest of patient health and safety. Through calculated media campaigns, this was clearly communicated with politicians and the public. Another major obstacle to the establishment of the specialty was the inclusion that AMM specialists be able to take internal medicine call at smaller hospitals. This was a compromise between emergency medicine purists and internal medicine to have the specialty established under the government's National Hospital Plan. Initially celebrated as a win for AMM, it became a sticking point when the Establishing Committee met to hash out the details and resulted in an AMM specialty with a heavy training focus on internal medicine. Interestingly, Norway's smaller hospitals have been quicker to embrace the new AMM specialty than the larger hospitals. Ironically, many of those who have been grandfathered in as specialists do not fully know the background that lead to their new specialty.

5. THE FUTURE OF EM IN NORWAY

On January 9, 2017, the Minister of Health announced that AMM would be a new primary specialty in Norway, the first clinical specialty since orthopedics was recognized in 1997. In March 2019, the Directorate of Health began accepting applications from physicians who wished to be grandfathered in as AMM specialists. Documentation of time spent in the acute receiving area and a broad knowledge base with focus on internal medicine was required. It was also required that physicians be able to document rotations/observation on various specialty services. The first AMM specialist, Jørn Rasmussen, was approved on July 5, 2019. 26 At the time of this publication, ≈40 physicians have applied to be grandfathered in as AMM specialists and 18 hospitals have applied to be training sites. Thirty specialists have been approved. The next step in this process will be to approve training sites for residents, although several hospitals have already begun training programs.

In Norway, as in the rest of Europe, medical school training requires 6 years of study that begins after high school graduation. Specialty training is then broken down into 3 parts. Part 1 must be completed by all physicians and typically takes 18 months. Revisions to Part 1 curriculum went into effect in 2020 and include rotations in internal medicine, surgery, psychiatry, and community health. Part 2 training varies according to one's chosen specialty. For AMM, Part 2 consists of internal medicine training, which typically takes 3 years. Part 3 is specific to AMM training and typically takes 2 years to complete. In addition to working in the acute receiving area, trainees will rotate through other specialties including surgery, orthopedics, anesthesia, ophthalmology, otolaryngology, pediatrics, and obstetrics and gynecology. Currently, there is no exit exam that is required to demonstrate one's competency in emergency medicine at the completion of training, but this is up for debate and will eventually be decided by the new AMM specialist union, which is still in the process of being formed. Two AMM specialists have taken the EBEEM. Both are also certified by the American Board of Emergency Medicine (ABEM). The format and content are similar among the 2 exams. Board certification exams are not a part of the postgraduate training culture in Norway. Rather, there are shorter exams at the end of each rotation as well as various courses that must be completed along the way. It is unclear if the EBEEM will be a requirement for AMM specialists in Norway. Because a certification exam is not required for other specialists, it may prove difficult to have this requirement for only 1 specialty.

The next step in the process of AMM development in Norway is to develop an AMM section under DNLF. This group will be composed of the newly approved AMM specialists. NORSEM, internal medicine, and anesthesia have each been asked to nominate potential members. Once this has been established, NORSEM can be dissolved as its mission will be complete. Hospitals are starting to develop training programs and are awaiting certification from the Directorate of Health. Research relevant to emergency medicine will need to continue and develop.

6. CONCLUSION

Although not without challenges, the establishment of emergency medicine as a new specialty in Norway occurred in a relatively short period of time; 7 years from the establishment of NORSEM until the Minister of Health declared emergency medicine would be a recognized specialty. It helped to have government and media focus on the problem of unsupervised and disorganized care in the acute receiving areas. From the publication of the national report “While we are waiting…” in 2008, until the first specialists were approved took 11 years.

Using Brian Zink's book, 2 Anyone, Anything, Anytime—A History of Emergency Medicine, as a playbook and international support for the specialty, a handful of visionaries were able to overcome much larger and more powerful groups of skeptics. This was accomplished by first and foremost doing what is best for the patient and clearly demonstrating this goal to politicians and policymakers as well as the general population through methodical use of the media.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

GG and KL both contributed to this article.

Galletta G, Løvstakken K. Emergency medicine in Norway: The road to specialty recognition. JACEP Open. 2020;1:790–794. 10.1002/emp2.12197

Supervising Editor: Chadd K. Kraus, DO, DrPH.

Funding and support: By JACEP Open policy, all authors are required to disclose any and all commercial, financial, and other relationships in any way related to the subject of this article as per ICMJE conflict of interest guidelines (see www.icmje.org). The authors have stated that no such relationships exist.

REFERENCES

- 1. Holliman CJ, Mulligan TM, Suter RE, et al. The efficacy and value of emergency medicine: a supportive literature review. Int J Emerg Med. 2011;4:44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zink B. Anyone, Anything, Anytime ‐ A History of Emergency Medicine. 2nd ed ACEP; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3. American College of Emergency Physicians. www.acep.org. Accessed February 22, 2020.

- 4. Totten V, Bellou A. Development of emergency medicine in Europe. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20(5):514‐521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. The Royal College of Emergency Medicine. www.rcem.ac.uk. Accessed February 22, 2020.

- 6. Australasian Society of Emergency Medicine. www.emergencymedicine.org.au. Accessed February 22, 2020.

- 7. European Society for Emergency Medicine. www.eusem.org. Accessed February 22, 2020.

- 8. Petrino R, Brown R, Härtel C, et al. European Board Examination in Emergency Medicine (EBEEM): assessment of excellence. Eur J Emerg Med. 2014;21(2):79‐80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Baldursson J, Björnsson HM, Palomäki A. Emergency medicine for 25 years in Iceland—history of the specialty in a nutshell. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2018;26(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hallas P, Ekelund U, Bjørnsen LP, Brabrand M. Hoping for a domino effect: a new specialty in Sweden is a breath of fresh air for the development of Scandinavian emergency medicine. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2013;21:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Naskali J, Lehtonen J, Palomäki A. Specialist training of Emergency Medicine in Finland. Duodecim. 2016;132(24):2389‐2393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kurland L, Graham CA. Emergency medicine development in the Nordic countries. Eur J Emerg Med. 2014;21(3):163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. World Bank . www.worldbank.org. Accessed May 4, 2020.

- 14. OECD . www.oecd.org. Accessed May 4, 2020.

- 15. Helsetilsynet. “Mens Vi Venter…” forsvarlig pasientbehandling i akuttmottakene? Oppsummering av landsomfattenende tilsyn i 2007 med forsvarlighet of kvalitet i akuttmottak i somatisk spesialisthelsetjeneste. Oslo; 2008.

- 16. Legeforening . www.legeforening.no. Accessed February 22, 2020.

- 17. Kirkevold F. Ferske turnusleger alene på landets akuttmottak. https://www.tv2.no/a/4019532; Accessed July 13, 2020. April 2, 2013.

- 18. Galletta G. Akuttmedisin: Hvordan har Ahus ført an? Dagens Medisin. February 14, 2014. https://www.dagensmedisin.no/artikler/2014/02/14/akuttmedisin-hvordan-har-ahus-fort-an/. Accessed July 13, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Regjeringen . Nasjonal helse‐ og sykehusplan. 2020. https://www.regjeringen.no/no/tema/helse-og-omsorg/sykehus/nasjonal-helse-og-sykehusplan2/id2461509/. Accessed July 13, 2020.

- 20. Melend C, Roald S. Ny spesialitet innrettet på akuttmottak ‐ utdypet oppdrag. Helse‐ og Omsorgsdepartement. Date 11/3/2015.

- 21. Nystad D, Brattebø G, Wisborg T, Gisvold S, Gilbert M. Vi trenger ikke en ny akuttmedisinsk spesialitet. Dagens Medisin. May 25, 2015. https://www.dagensmedisin.no/artikler/2015/05/25/vi-trenger-ikke-en-ny-akuttmedisinsk-spesialitet/. Accessed July 13, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Uleberg O, Lillebo B, Achterberg H, Løvstakken K, Galletta G. Vi trenger en ny akuttmedisinsk spesialitet. Dagens Medisin. June 3, 2015. https://www.dagensmedisin.no/artikler/2015/06/03/vi-trenger-en-ny-akuttmedisinsk-spesialitet/. Accessed July 13, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 23. International Federation of Emergency Medicine. www.ifem.cc. Accessed February 22, 2020.

- 24. Buskop C. Debatten om akuttmedisin i Norge. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen. 2016;4(136):296‐297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bjørnsen LP, Uleberg O. [The emergency department needs their own specialists]. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2015;135(14):1230‐1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vestreviken. Norges første spesialist i akutt‐ og mottaks medisin. 2019. https://vestreviken.no/om-oss/nyheter/norges-forste-spesialist-i-akutt-og-mottaksmedisin. Accessed May 4, 2020.