Abstract

Emergency medicine has increasingly focused on addressing social determinants of health (SDoH) in emergency medicine. However, efforts to standardize and evaluate measurement tools and compare results across studies have been limited by the plethora of terms (eg, SDoH, health‐related social needs, social risk) and a lack of consensus regarding definitions. Specifically, the social risks of an individual may not align with the social needs of an individual, and this has ramifications for policy, research, risk stratification, and payment and for the measurement of health care quality. With the rise of social emergency medicine (SEM) as a field, there is a need for a simplified and consistent set of definitions. These definitions are important for clinicians screening in the emergency department, for health systems to understand service needs, for epidemiological tracking, and for research data sharing and harmonization. In this article, we propose a conceptual model for considering SDoH measurement and provide clear, actionable, definitions of key terms to increase consistency among clinicians, researchers, and policy makers.

Keywords: emergency medicine, social determinants of health

1. EXISTING TERMINOLOGY

Social determinants of health (SDoH) have been defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the “conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life. These forces and systems include economic policies and systems, development agendas, social norms, social policies, and political systems.” 1 SDoH have been used to describe both individual and neighborhood‐level data. 2 Several Medicaid programs use SDoH and “social risk” interchangeably when discussing the individual‐level factors, such as access to food and housing, that affect health. 3 Other Medicaid programs, such as MassHealth, separate SDoH from other neighborhood‐based predictors of health in risk prediction models. 4 The National Academy of Sciences uses the term “health‐related social needs” 5 to describe screening questions to assess 5 core domains (housing, food, transportation, utilities, and safety), whereas some authors have termed this concept “social risk.” 6 Several papers have suggested that screening should be based on desire for assistance rather than the identification of unmet needs. 7 , 8 This desire for assistance is termed a “social need” by some authors. 6 , 9 The use of these multiple, somewhat overlapping, terms (SDoH, health‐related social needs, social needs, and social risk) has hindered communication within the field of social emergency medicine (SEM), which “considers the interplay between social forces and the emergency care system as they together influence the health of individuals and their communities.” 10

2. IMPORTANCE OF SDOH IN THE EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT

Increased attention has been focused on social and systemic factors that influence health in emergency department (ED) settings. 10 A recent systematic review found a high prevalence of material needs among patients in several ED studies. 11 In addition, studies have shown a strong association between SDoH and ED utilization. 12 , 13 For example, during the first year of life, children who experienced homelessness were significantly more likely to visit the ED. 14 Using insurance billing data for an adult sample, 1 study found that patients with incomes less than the national median had a significantly increased risk of ED visits for hypoglycemia in the last week of the month (when food benefits would be expected to run out) compared to earlier weeks. 15 Health disparity populations, including racial/ethnic minorities, those with public insurance beneficiaries, and those with chronic disease also have higher rates of ED use. 16 Patients with low socioeconomic status are also more likely to rely on the ED as a usual source of care. 17

The combination of a high prevalence of needs in the ED patient population and the likelihood that many ED patients are not seen in primary care means that ED‐based screening has the potential to reach many vulnerable patients. Recent changes in state public insurance programs have placed additional emphasis on the importance of social factors, with several states requiring screening for SDoH or health‐related social needs. 18 , 19 Although social screening in primary care has been shown to be feasible in both adult 20 and pediatric 21 , 22 settings, it has not been widely implemented in the ED setting. Before the initiation of ED screening, it is critically important to define what is being screened for and why. One particular challenge is the significant discrepancy between those who screen positive using a tool and those who actually request help. One study in a pediatric clinic focused on food insecurity and found that 36% of caregivers reported a food‐related issue: 4% reported food insecurity but did not request help, 15% requested help but did not report food insecurity, and 17% both reported food insecurity and requested help. 8

Implementation of ED screening is complicated by the heterogeneity of screening tools and the lack of a goldstandard to identify SDoH. 7 In addition, different programs have used different terms for similar concepts including SDoH, 2 , 20 , 23 health‐related social needs, 5 , 24 social needs, 25 , 26 and social risk. 27 , 28 , 29 ED clinicians, researchers, and policy makers, need a consistent terminology to identify patients who screen positive and those who are requesting assistance. In addition, an appropriate terminology would allow clinicians and researchers to have increased clarity about the goals of individual screening programs (eg, service, epidemiology, risk stratification), allow for improved comparison across studies, and allow policy makers and researchers to more effectively communicate and therefore more rapidly disseminate research.

3. PROPOSED TERMINOLOGY

3.1. SDoH are universal and neither inherently positive nor negative

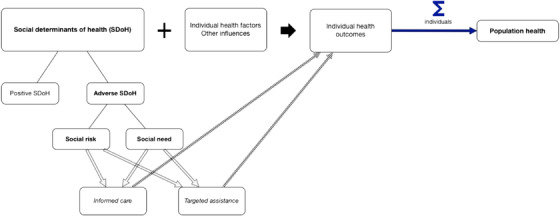

Guided by the SDoH Lexicon provided by Alderwick et al, 6 we propose a simplified terminology around SDoH for emergency medicine clinicians, researchers, and policy makers (Figure 1). We begin with the WHO definition as the “conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life.” 1 These can include both individual‐level factors (such as education and employment) and neighborhood‐level factors (such as transportation systems). All individuals are affected by SDoH, which can shape health for better or worse. For example, positive SDoH include high income and neighborhood cohesion. In contrast, adverse SDoH include individual poverty and neighborhood isolation (lack of transportation links). Examples of positive SDoH include improved infant mortality rates in counties with higher percentages of Hispanic residents 30 or pediatric respiratory health benefits in neighborhoods with high density of immigrants. 31 In contrast, examples of negative social determinants include both individual and neighborhood poverty, which are associated with medication nonadherence. 32 Thus, the term “SDoH” is applicable to screening studies where the prevalence and influence of specific determinants, risks, and needs are unknown. Risk factors can be individual or group level and may be causal in nature (lead to disease) or correlated markers of underlying causal factors that are more difficult to measure (eg, race is often referred to as a “risk factor” for poor health outcomes, which are likely mediated by the effects of structural, systemic, and individual racism). 33

FIGURE 1.

Terminology of SDoH. Across the top of the figure, SDoH and other factors combine to influence individual health outcomes. These outcomes, summed across the individuals, make up the health of the population. SDoH can be positive or adverse; adverse SDoH include both social risk (specific adverse social conditions associated with poor health) and social need (individual preferences and priorities regarding assistance). Both social risk and social need can be used to inform care and target assistance. Abbreviation: SDoH—social determinants of health

3.2. Risk versus need

Within the category of adverse SDoH, the proposed terminology separates social risk and social need. Social risks are the “specific adverse social conditions associated with poor health” as measured at the individual level, 6 whereas social needs are determined by the individual preferences and priorities. 6 For example, a social risk would be a positive screen for food insecurity, whereas a social need would be a request for food assistance. An individual can have multiple social risks and fewer social needs, or vice versa. 9 Assessments of social risk may be most important for epidemiology, risk adjustment for payment models, or the design and deployment of programs to address social risks. Understanding the population at risk for homelessness (social risk) may help policy makers and city administrators plan shelter beds, but ED clinicians are likely to be more focused on patients requesting housing during their ED visit (social need). Both social risk and social need can be used to inform care decisions (eg, selecting location of follow‐up appointments) and to target assistance to address adverse SDoH directly (eg, providing transportation to follow‐up appointments). Importantly, the term “health‐related social needs,” which was often used to describe risk factors rather than needs, would be replaced by “social risk.” The Appendix (Online Supplement) shows examples of how the terminology can be applied to the core domains of housing, food, transportation, and utilities. We do not provide a figure for safety because our prior work suggested wide variation in how people defined this concept. 34

3.3. SDoH versus population health

As much of the SDoH work has been done under the auspices of population health and population health management, it is important to clarify that SDoH are not the same as population health. Population health has several different definitions, including conceptual frameworks for thinking about differences in health outcomes between populations and measurement of the health of a population. Population health also involves the study of “health outcomes and their distribution in the population…achieved by patterns of health determinants (such as medical care, public health, socioeconomic status, physical environment, individual behavior and genetics) over the life course.” 35 Overall, population health focuses on the impact of the health of the group, which can be defined by geography (eg, city), membership (eg, health plan), or other characteristics. 35 SDoH focus primary on the subset of non‐genetic, non‐behavioral factors that mediate overall population health and are critical to incorporate when assessing population health outcomes.

4. FUTURE WORK

In parallel with this effort to improve the terminology of SEM among clinicians, researchers, and policy makers, we encourage future work in several areas. There is an urgent need to standardize and incentivize the collection of SDoH data within electronic health records to support important research on how to best intervene. 36 Individuals collecting SDoH data should choose data collection tools (eg, PhenX Toolkit) 37 with specific attention to whether they wish to collect social risk, social need, or both. Additional work is needed to guide best practices for extracting data for research, quality improvement, and payment reform/risk adjustment models. 38 Although many sources have suggested using billing and diagnosis codes, specifically International Classification of Diseases‐10 (ICD‐10) Z codes, they do not yet have a one‐to‐one link with any of the social risk screening tools, and several Z codes lack specificity. For example, “lack of adequate food and safe drinking water (Z59.4)” could include both people with a lack of resources to purchase food and those who live in neighborhoods without access to healthy food sources, 38 two problems that suggest very different interventions. Increased specificity in ICD coding regarding specific social risks and coordination with existing measures of social risk will increase the ease of such documentation. In addition to developing a system to collect SDoH data within the health care system, further work is needed to develop an infrastructure to share data with social care organizations, such as shelters or food pantries. 39 More robust research is needed on the effectiveness of screening programs for SDoH in acute care settings, including their impact on patient‐centered outcomes (eg, well‐being, insecurity) outside of downstream ED utilization. 40 Finally, additional research is needed into how to best combine data collection and intervention to improve clinical decisionmaking, health care access, and ultimately patient outcomes. 7

Supporting information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information

APPENDIX 1.

Online supplement

Appendix Figures: Examples of the terminology for housing, food, utilities, and transportation

Appendix A: Housing

Appendix B: Food

Appendix C: Utilities

Appendix D: Transportation

Abbreviation: SDoH, social determinants of health

Samuels‐Kalow ME, Ciccolo GE, Lin MP, Schoenfeld EM, Camargo CA. The terminology of social emergency medicine: Measuring social determinants of health, social risk and social need. JACEP Open. 2020;1:852–856. 10.1002/emp2.12191

Funding and support: Dr. Samuels‐Kalow is supported by the Harvard Catalyst. The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health Award UL 1TR002541) and financial contributions from Harvard University and its affiliated academic health care centers. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Harvard Catalyst, Harvard University and its affiliated academic health care centers, or the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Schoenfeld is supported by a K08 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (5K08HS025701‐02). Dr. Lin is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI/NIH) award K23 HL143042.

Supervising Editor: Marna Rayl Greenberg, DO, MPH.

REFERENCES

- 1. Social determinants of health. World Health Organization. Available, at https://www.who.int/social_determinants/en/.) Accessed March 29, 2020. 2018.

- 2. Gottlieb LM, Francis DE, Beck AF. Uses and misuses of patient‐ and neighborhood‐level social determinants of health data. Perm J. 2018;22:18‐078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Measuring Social Determinants of Health among Medicaid Beneficiaries: Early State Lessons. Hamilton, NJ: Center for Health Care Strategies, Inc., 2016.Available at https://www.chcs.org/media/CHCS-SDOH-Measures-Brief_120716_FINAL.pdf. Accessed March 7, 2020.

- 4. Ash, AS , Mick E. UMass Risk Adjustment Project for MassHealth Payment and Care Delivery Reform: Describing the 2017 Payment Model Worcester, MA: Center for Health Policy and Research, UMass Medical School; https://www.mass.gov/files/documents/2017/11/07/1610-umass-modeling-sdh-summary-report.pdf?_ga=2.43011297.598289181.1585478385-303339415.1585478385.) 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Billioux A, Verlander K, Anthony S, Alley D. Standardized screening for health‐related social needs in clinical settings: the accountable health communities screening tool. Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine. 2017.

- 6. Alderwick H, Gottlieb LM. Meanings and misunderstandings: a social determinants of health lexicon for health care systems. The Milbank Quarterly. 2019;97:407‐419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Garg A, Sheldrick RC, Dworkin PH. The inherent fallibility of validated screening tools for social determinants of health. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18:123‐124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bottino CJ, Rhodes ET, Kreatsoulas C, Cox JE, Fleegler EW. Food insecurity screening in pediatric primary care: can offering referrals help identify families in need? Acad Pediatr. 2017;17:497‐503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. When Talking About Social Determinants, Precision Matters. Health Affairs Blog, October 29, 2019. Available at https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20191025.776011/full/. Accessed December 3, 2019.

- 10. Anderson ES, Hsieh D, Alter HJ. Social emergency medicine: embracing the dual role of the emergency department in acute care and population health. Ann Emerg Med 2016;68:21‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Malecha PW, Williams JH, Kunzler NM, Goldfrank LR, Alter HJ, Doran KM. Material needs of emergency department patients: a systematic review. Acad Emerg Med. 2018;25:330‐359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kersten EE, Adler NE, Gottlieb L, et al. Neighborhood child opportunity and individual‐level pediatric acute care use and diagnoses. Pediatrics. 2018;141(5):e20172309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Taylor T, Salyakina D. Health care access barriers bring children to emergency rooms more frequently: a representative survey. Popul Health Manag. 2019;22:262‐71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Clark RE, Weinreb L, Flahive JM, Seifert RW. Infants exposed to homelessness: health, health care use, and health spending from birth to age six. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38:721‐728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Basu S, Berkowitz SA, Seligman H. The monthly cycle of hypoglycemia: an observational claims‐based study of emergency room visits, hospital admissions, and costs in a commercially insured population. Med Care. 2017;55:639‐645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tang N, Stein J, Hsia RY, Maselli JH, Gonzales R. Trends and characteristics of US emergency department visits, 1997–2007. JAMA. 2010;304:664‐670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kangovi S, Barg FK, Carter T, Long JA, Shannon R, Grande D. Understanding why patients of low socioeconomic status prefer hospitals over ambulatory care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32:1196‐1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Prioritizing social determinants of health in Medicaid ACO programs: a conversation with two pioneering states. Hamilton, NJ: Center for Health Care Strategies, Inc; May 2, 2018. Available at https://www.chcs.org/prioritizing-social-determinants-health-medicaid-aco-programs-conversation-two-pioneering-states/. Accessed June 13, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Massachusetts’ Medicaid ACO makes a unique commitment to addressing social determinants of health. Hamilton, NJ: Center for Health Care Strategies, Inc; December 19, 2016. Available at https://www.chcs.org/massachusetts-medicaid-aco-makes-unique-commitment-addressing-social-determinants-health/. Accessed June 13, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Buitron de la Vega P, Losi S, Sprague Martinez L, et al. Implementing an EHR‐based screening and referral system to address social determinants of health in primary care. Med Care 2019;57 Suppl 6 Suppl 2:S133‐S9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gottlieb L, Hessler D, Long D, Amaya A, Adler N. A randomized trial on screening for social determinants of health: the iScreen study. Pediatrics. 2014;134:e1611‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gottlieb LM, Hessler D, Long D, et al. Effects of social needs screening and in‐person service navigation on child health: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr 2016;170:e162521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gold R, Bunce A, Cowburn S, et al. Adoption of social determinants of health EHR tools by community health centers. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16:399‐407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Engelberg Anderson JK, Jain P, Wade AJ, Morris AM, Slaboda JC, Norman GJ. Indicators of potential health‐related social needs and the association with perceived health and well‐being outcomes among community‐dwelling Medicare beneficiaries. Qual Life Res. 2020;29(6):1685‐1696.[Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nau C, Adams JL, Roblin D, Schmittdiel J, Schroeder E, Steiner JF. Considerations for identifying social needs in health care systems: a commentary on the role of predictive models in supporting a comprehensive social needs strategy. Med Care. 2019;57:661‐666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Beck AF, Cohen AJ, Colvin JD, et al. Perspectives from the Society for Pediatric Research: interventions targeting social needs in pediatric clinical care. Pediatr Res. 2018;84:10‐21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Byhoff E, De Marchis EH, Hessler D, et al. Part II: a qualitative study of social risk screening acceptability in patients and caregivers. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57:S38‐S46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vaz LE, Wagner DV, Ramsey KL, et al. Identification of caregiver‐reported social risk factors in hospitalized children. Hosp Pediatr. 2020;10:20‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Navathe AS, Zhong F, Lei VJ, et al. Hospital readmission and social risk factors identified from physician notes. Health Serv Res. 2018;53:1110‐36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shaw RJ, Pickett KE. The health benefits of Hispanic communities for non‐Hispanic mothers and infants: another Hispanic paradox. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:1052‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kim YA, Collins TW, Grineski SE. Neighborhood context and the Hispanic health paradox: differential effects of immigrant density on childrens wheezing by poverty, nativity and medical history. Health Place. 2014;27:1‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hensley C, Heaton PC, Kahn RS, et al., Poverty, transportation access, and medication nonadherence. Pediatrics. 2018;141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sheets L, Johnson J, Todd T, Perkins T, Gu C, Rau M. Unsupported labeling of race as a risk factor for certain diseases in a widely used medical textbook. Acad Med. 2011;86:1300‐1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ciccolo GE, Curt A, Camargo C, Samuels‐Kalow M. Improving understanding of screening questions for social risk and social need for emergency department patients. West J Emerg Med. 2020;in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kindig DA. Understanding population health terminology. Milbank Q. 2007;85:139‐161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cantor MN, Thorpe L. Integrating data on social determinants of health into electronic health records. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37:585‐590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hamilton CM, Strader LC, Pratt JG, et al. The PhenX Toolkit: get the most from your measures. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174:253‐260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gottlieb L, Tobey R, Cantor J, Hessler D, Adler NE. Integrating social and medical data to improve population health: opportunities and barriers. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35:2116‐2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bibbins‐Domingo K. Integrating social care into the delivery of health care. JAMA. 2019;322:1763‐1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Abir M, Hammond S, Iovan S, Lantz PM. Why More Evidence Is Needed on the Effectiveness of Screening for Social Needs Among High‐Use Patients in Acute Care Settings. Health Affairs Blog. May 23, 2019. Available at https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20190520.243444/full/. Accessed May 13, 2020

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information