Abstract

Objectives

Dermatological disorders are common in general pediatric practice. This study aimed to examine common skin problems and the manner in which they tend to be misdiagnosed.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted from January 2015 to December 2016 using medical record data from the Pediatric Dermatological Outpatient Unit at Khon Kaen University, Faculty of Medicine.

Results

A total of 1551 visits by 769 patients were documented during the study period. A total of 114 presenting diseases were recorded. The most common skin disease in the study population was dermatitis (unspecified) (88/769, 11.4%), followed by atopic dermatitis (76/769, 9.8%) and infantile hemangioma (72/769, 9.3%). There was a total of 55 (48.2%) misdiagnosed diseases. Some unique cutaneous diseases were undiagnosed because of their rarity. However, the percentages of common cutaneous diseases, such as tinea capitis and molluscum contagiosum, which had been misdiagnosed, were also high (62.50% [95% confidence interval = 24.49–91.48] and 71.43% [95% confidence interval = 29.04–96.33], respectively).

Conclusion

A large percentage of misdiagnoses of common cutaneous diseases may be due to general pediatricians being undereducated in the field of dermatology. Accurate recognition and appropriate management of these conditions should be emphasized for educating general pediatricians in the future.

Keywords: Misdiagnosis, epidemiology, pediatric dermatology, skin disease, dermatitis, infantile hemangioma

Introduction

Dermatological disorders are common in general pediatric practice and usually differ depending on age, region, race, and socioeconomic status.1–4 Pediatricians can diagnose and treat a majority of common, uncomplicated skin problems at a patient’s first visit. However, more complicated skin diseases may require further consultation.5 In Thailand, there are a limited number of pediatric dermatologists, and they mainly work in university hospitals. Therefore, most patients with complicated skin diseases are referred to a tertiary care university hospital, such as our hospital (Khon Kaen University, Faculty of Medicine). In our practice, patients sometimes present with dermatological disorders that had previously been misdiagnosed elsewhere by general pediatricians.

Therefore, the present study aimed to record the prevalence of cutaneous disorders in children who present at our center. Our center is located in northeast Thailand, and this study will be the first to provide data regarding the prevalence of cutaneous disorders in this region. The results of our study will provide basic information regarding common skin problems and the manner in which they tend to be misdiagnosed. These data will be important for general pediatricians that can aid them in diagnosing common diseases in this region. Furthermore, these data can be applied to improve education regarding pediatric skin diseases for general pediatricians and pediatric residents.

Methods

Ethics approval

All experiments in this retrospective investigation were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The study was approved by the Khon Kaen University Faculty of Medicine Ethics Committee (IRB no. HE591323). Informed consent was not required because this was a retrospective study.

Patients

We conducted a cross-sectional epidemiological study from January 2015 to December 2016 using data from medical records from the Pediatric Dermatological Outpatient Unit at Khon Kaen University, Faculty of Medicine, which provides training to pediatric residents at the university hospital.

Clinical diagnosis was made by a pediatric dermatologist, and pathological diagnosis (when necessary) was considered the final diagnosis for dermatological problems. Misdiagnosis was defined as a wrong diagnosis (based on International Classification of Diseases 10th revision guidelines) that was documented in the medical records made by general pediatricians at another hospital and/or pediatric residents who were in training before the patient presented to our pediatric dermatology unit.

Statistical analysis

At the end of the study, the data that we collected were analyzed using STATA software version 10 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Descriptive statistical methods, including means, standard deviations (SDs), medians, and frequencies, were used to analyze the demographic data.

Results

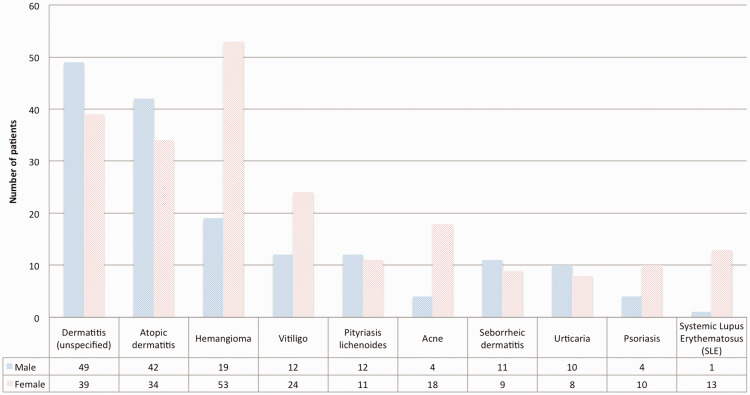

There was a total of 1551 visits by 769 patients with dermatological conditions during the study period. Patients’ ages ranged from 1 month to 18 years. The median age (interquartile range) was 7 years (4–11) and the mean age was 7.75 years (SD = 4.5). There were 348 boys and 421 girls, with a male to female ratio of 0.82. A total of 114 diseases were recorded. The most common skin disease in the study population was dermatitis (unspecified) (88/769 cases, 11.4%), followed by atopic dermatitis (76/769 cases, 9.8%) and infantile hemangioma (72/769 cases, 9.3%). The ten most common diseases are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The 10 most common skin diseases diagnosed by pediatric dermatologists in the study population.

We classified dermatological disorders into 12 subgroups. Eczematous disease was the most common (241/769, 31.3%), followed by vascular and lymphatic disorders (93/769, 12%) and infection (60/769, 7.8%). All dermatological subgroups and particular dermatological disorders included in each subgroup are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Diagnoses of cutaneous disorders classified into subgroups and the percentage of misdiagnosis among the subgroups.

| Subgroups of cutaneous diseases | Most frequent skin disease | Numberof patients | % of misdiagnosesin each subgroup | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eczematousdisease | Dermatitis (unspecified) | 88 | 0.00 | 0.00–4.11 |

| Atopic dermatitis | 76 | 0.00 | 0.00–4.74 | |

| Seborrheic dermatitis | 20 | 0.00 | 0.00–16.84 | |

| Juvenile plantar dermatosis of childhood | 10 | 30.00 | 6.67–65.25 | |

| Nummular eczema | 9 | 0.00 | 0.00–33.63 | |

| Pityriasis alba | 7 | 71.43 | 29.04–96.33 | |

| Dyshidrosis | 6 | 0.00 | 0.00–45.93 | |

| Prurigo nodularis | 5 | 0.00 | 0.00–52.18 | |

| Lichen simplex chronicus | 4 | 0.00 | 0.00–60.24 | |

| Lip-licking dermatitis | 4 | 0.00 | 0.00–16.84 | |

| Keratosis pilaris | 4 | 0.00 | 0.00–16.84 | |

| Lichen striatus | 3 | 100.00 | 29.24–100.00 | |

| Lichen nitidus | 2 | 100.00 | 15.81–100.00 | |

| Lichen simplex chronicus | 2 | 0.00 | 0.00–84.19 | |

| Intertrigo | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00–97.50 | |

| Papulosquamous disease | Pityriasis lichenoides | 23 | 86.96 | 66.41–97.23 |

| Psoriasis | 14 | 0.00 | 0.00–23.16 | |

| Pustular psoriasis | 9 | 100.00 | 66.37–100.00 | |

| Pityriasis rubra pilaris | 9 | 44.44 | 13.70–78.80 | |

| Pityriasis rosea | 2 | 100.00 | 15.81–100.00 | |

| Cutaneous reaction | Urticaria | 18 | 0.00 | 0.00–18.53 |

| Insect bite reaction/papular urticaria | 8 | 0.00 | 0.00–36.94 | |

| Stevens–Johnson syndrome | 2 | 0.00 | 0.00–84.19 | |

| Erythema multiforme | 2 | 0.00 | 0.00–84.19 | |

| Fixed drug eruption | 2 | 0.00 | 0.00–84.19 | |

| Anaphylaxis reaction | 2 | 0.00 | 0.00–84.19 | |

| Erythema nodosum | 2 | 0.00 | 0.00–84.19 | |

| Connective tissue disease | Systemic lupus erythematosus | 14 | 0.00 | 0.00–23.16 |

| Henoch–Schonlein purpura | 6 | 0.00 | 0.00–45.93 | |

| Panniculitis | 6 | 66.67 | 22.28–95.67 | |

| Linear morphea | 6 | 66.67 | 22.28–95.67 | |

| Neonatal lupus | 4 | 100.00 | 39.76–100.00 | |

| Vasculitis | 4 | 0.00 | 0.00–60.24 | |

| Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus | 1 | 100.00 | 2.50–100.00 | |

| Urticarial vasculitis | 1 | 100.00 | 2.50–100.00 | |

| Dermatomyositis | 1 | 100.00 | 2.50–100.00 | |

| Behcet’s disease | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00–97.50 | |

| Vascular and lymphatic disorders | Hemangioma | 72 | 0.00 | 0.00–4.99 |

| Vascular malformation | 5 | 40.00 | 5.28–85.34 | |

| Venolymphatic malformation | 5 | 40.00 | 5.28–85.34 | |

| PHACE syndrome | 2 | 0.00 | 0.00–84.19 | |

| Port wine stain | 2 | 0.00 | 0.00–84.19 | |

| Sturge–Weber syndrome | 2 | 0.00 | 0.00–84.19 | |

| Lymphangioma circumscriptum | 2 | 100.00 | 15.81–100.00 | |

| Pyogenic granuloma | 1 | 100.00 | 2.50–100.00 | |

| Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome | 1 | 100.00 | 2.50–100.00 | |

| Lymphatic malformation | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00–97.50 | |

| Other inherited diseases | Lamellar ichthyosis | 10 | 70.00 | 34.76–93.33 |

| Ectodermal dysplasia | 3 | 0.00 | 0.00–70.76 | |

| Ichthyosis vulgaris | 2 | 0.00 | 0.00–84.19 | |

| Epidermolysis hyperkeratosis | 2 | 100.00 | 15.81–100.00 | |

| Mccune–Albright syndrome | 1 | 100.00 | 2.50–100.00 | |

| Neurofibromatosis | 1 | 100.00 | 2.50–100.00 | |

| Ichthyosis follicularis, alopecia and photophobia syndrome | 1 | 100.00 | 2.50–100.00 | |

| Infection | Bacteria | |||

| Impetigo | 12 | 0.00 | 0.00–26.47 | |

| Folliculitis | 3 | 0.00 | 0.00–70.76 | |

| Ecthyma | 2 | 0.00 | 0.00–84.19 | |

| Skin tuberculosis | 1 | 100.00 | 2.50–100.00 | |

| Virus | ||||

| Molluscum contagiosum | 7 | 71.43 | 29.04–96.33 | |

| Wart | 6 | 0.00 | 0.00–45.93 | |

| Hand, foot, and mouth disease | 5 | 0.00 | 0.00–52.18 | |

| Verruca plana | 1 | 100.00 | 2.50–100.00 | |

| Fungus | ||||

| Tinea capitis | 8 | 62.50 | 24.49–91.48 | |

| Pityriasis versicolor | 3 | 0.00 | 0.00–70.76 | |

| Tinea unguium | 2 | 0.00 | 0.00–84.19 | |

| Candidiasis | 2 | 0.00 | 0.00–84.19 | |

| Pityrosporum folliculitis | 2 | 0.00 | 0.00–84.19 | |

| Tinea corporis | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00–97.50 | |

| Tinea incognito | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00–97.50 | |

| Tinea faciei | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00–97.50 | |

| Vaginal candidiasis | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00–97.50 | |

| Mite | ||||

| Scabies | 2 | 100.00 | 15.81–100.00 | |

| Hair disorders | Alopecia areata/totalis/universalis | 13 | 0.00 | 0.00–24.71 |

| Trichotillomania | 12 | 41.67 | 15.17–72.33 | |

| Telogen effluvium | 4 | 100.00 | 39.76–100.00 | |

| Premature gray hair | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00–97.50 | |

| Nail disorders | Twenty-nail dystrophy | 5 | 100.00 | 47.82–100.00 |

| Onychomadesis | 4 | 100.00 | 39.76–100.00 | |

| Paronychia | 3 | 0.00 | 0.00–70.76 | |

| Onychomycosis | 2 | 0.00 | 0.00–84.19 | |

| Melanonychia | 2 | 100.00 | 15.81–100.00 | |

| Pigmentary disorders | Vitiligo | 36 | 0.00 | 0.00–9.74 |

| Nevus depigmentosus | 5 | 100.00 | 47.82–100.00 | |

| Congenital melanocytic nevus | 9 | 0.00 | 0.00–33.63 | |

| Multiple lentigines | 2 | 0.00 | 0.00–84.19 | |

| Erythema dyschromicum perstans | 2 | 100.00 | 15.81–100.00 | |

| Nevus of Ota | 2 | 0.00 | 0.00–84.19 | |

| Halo nevus | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00–97.50 | |

| Hypomelanosis of Ito | 1 | 100.00 | 2.50–100.00 | |

| Speckled lentiginous nevus | 1 | 100.00 | 2.50–100.00 | |

| Post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00–97.50 | |

| Vesiculobullous diseases | Epidermolysis bullosa | 7 | 42.86 | 9.90–81.60 |

| Chronic bullous dermatosis of childhood | 6 | 33.33 | 4.33–77.72 | |

| Pemphigus vulgaris | 5 | 60.00 | 14.66–94.73 | |

| Incontinentia pigmenti | 2 | 50.00 | 1.26–98.74 | |

| Bullous pemphigoid | 2 | 50.00 | 1.26–98.74 | |

| Miscellaneous | Acne | 22 | 0.00 | 0.00–15.44 |

| Urticaria pigmentosa | 12 | 83.33 | 51.59–97.91 | |

| Nevus sebaceous | 9 | 0.00 | 0.00–33.63 | |

| Epidermal nevus | 8 | 62.50 | 24.49–91.48 | |

| Miliaria rubra | 7 | 57.14 | 18.41–90.10 | |

| Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis | 4 | 100.00 | 39.76–100.00 | |

| Gianotti–Crosti syndrome | 4 | 100.00 | 39.76–100.00 | |

| Juvenile xanthogranuloma | 4 | 100.00 | 39.76–100.00 | |

| Geographic tongue | 4 | 100.00 | 39.76–100.00 | |

| Umbilical granuloma | 3 | 100.00 | 29.24–100.00 | |

| Granuloma annulare | 3 | 100.00 | 29.24–100.00 | |

| Dermoid cyst/inclusion cyst | 3 | 0.00 | 0.00–70.76 | |

| Recurrent oral ulcer | 3 | 0.00 | 0.00–70.76 | |

| Acanthosis nigricans | 3 | 0.00 | 0.00–70.76 | |

| Mycosis fungoides | 1 | 100.00 | 2.50–100.00 | |

| Nevus comedonicus | 1 | 100.00 | 2.50–100.00 | |

| Trichoepithelioma | 1 | 100.00 | 2.50–100.00 |

CI: confidence interval; PHACE: posterior fossae of the brain, arterial anomalies, cardiac anomalies, and eye anomalies.

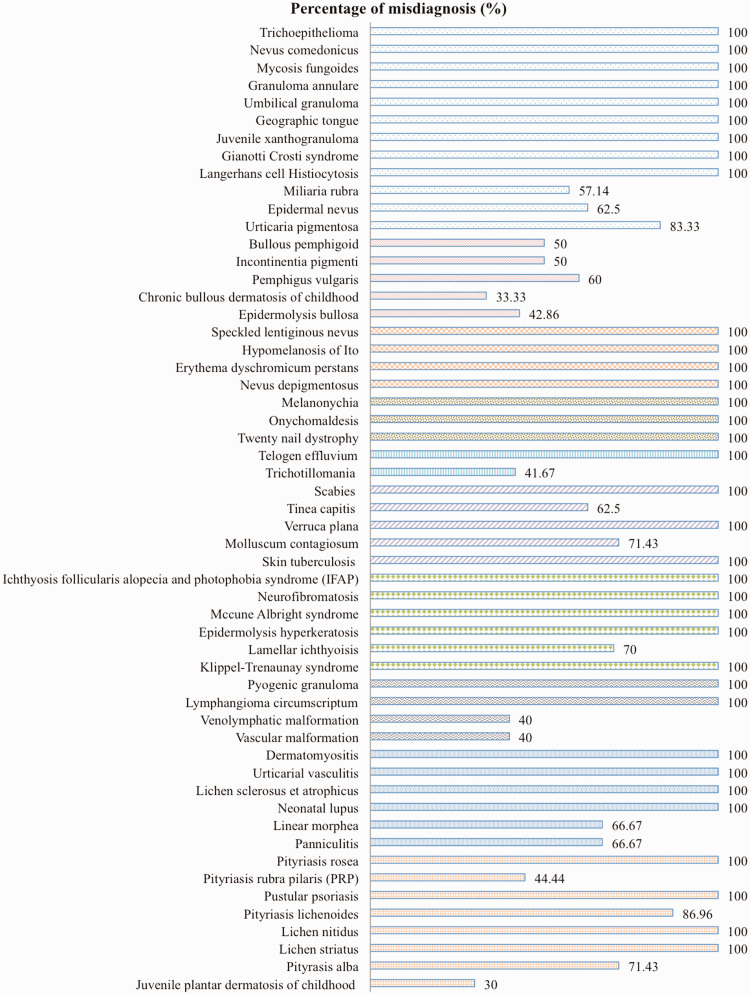

There was a total of 55/114 (48.2%) misdiagnosed diseases, 35 of which had been completely undiagnosed before the patients presented at the Pediatric Dermatology Clinic. Misdiagnosed skin diseases in the study population had particular different presentations, and varied from difficult unique and/or rare skin diseases that were difficult to initially diagnose to common skin diseases, but they were unable to be recognized. Miliaria rubra (57.14%), epidermal nevus (62.5%), tinea capitis (62.5%), molluscum contagiosum (71.43%), and pityriasis alba (71.43%) were some of the common cutaneous diseases that were misdiagnosed in the study population. The percentages of other misdiagnosed skin diseases are shown in Table 1 and Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The percentages of misdiagnosis of each skin disease in the study population.

The prevalence of some cutaneous diseases differed according to sex. Infantile hemangioma (p = 0.016), neonatal lupus erythematosus (p = 0.009), and acne (p = 0.006) were more common in girls than in boys, while chronic bullous dermatosis of childhood was more common in boys than in girls (p = 0.009) in this study population. Other cutaneous diseases of which the prevalence varied by sex are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Prevalence of cutaneous diseases according to sex.

| Cutaneous diseases | Male | Female | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Connective tissue disease | (n = 10) | (n = 34) | |

| Neonatal lupus erythematosus | 0 (0.00) | 0 (30.00) | 0.009 |

| Vascular and lymphatic disorder | (n = 31) | (n = 62) | |

| Hemangioma | 19 (61.29) | 53 (85.48) | 0.016 |

| Other inherited diseases | (n = 5) | (n = 15) | |

| Lamellar ichthyosis | 0 (0.00) | 10 (66.67) | 0.033 |

| Vesiculobullous disease | (n = 5) | (n = 17) | |

| Chronic bullous dermatosis of childhood | 4 (80.00) | 2 (11.77) | 0.009 |

| Miscellaneous | (n = 40) | (n = 50) | |

| Acne | 4 (10.00) | 18 (36.00) | 0.006 |

Values are number (%).

The prevalence of diagnosis was also analyzed on the basis of age group. We classified the study population into four age groups as follows: i) infants and toddlers ( < 3 years old), ii) preschool age (3 to < 6 years old), iii) school age (6 to < 12 years old), and iv) adolescents (12–18 years old). Atopic dermatitis had the lowest prevalence in the school age group (p = 0.031) and acne had a significantly higher prevalence in the adolescent group than in any of the other age groups (p < 0.001). Other presenting cutaneous diseases with significant differences among the age groups (p < 0.05) are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Prevalence of diagnosis in various age groups.

| Cutaneous diseases | Infants and toddlers( < 3 years old) | Preschool age (3 to < 6 years old) | School age (6 to < 12 years old) | Adolescents(12–18 years old) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eczematous dermatitis | (n = 71) | (n = 91) | (n = 56) | (n = 23) | |

| Atopic dermatitis | 28 (39.44)a | 33 (36.26)a | 10 (17.86)b | 5 (21.74)a | 0.031 |

| Juvenile plantar dermatosis of childhood | 0 (0.00)a | 4 (4.40)a | 6 (10.71)b | 0 (0.00)a | 0.017 |

| Seborrheic dermatitis | 18 (25.35)a | 0 (0.00)b | 0 (0.00)b | 2 (8.70)a | <0.001 |

| Dyshidrosis | 0 (0.00)a | 1 (1.10)a | 5 (8.93)b | 0 (0.00)a | 0.005 |

| Prurigo nodularis | 0 (0.00)a | 1 (1.10)a | 0 (0.00)a | 4 (17.39)b | <0.001 |

| Pityriasis alba | 0 (0.00)a | 2 (2.20)ab | 5 (8.93)b | 0 (0.00)a | 0.017 |

| Lichen simplex chronicus | 0 (0.00)a | 0 (0.00)a | 1 (1.79)a | 3 (13.04)b | <0.001 |

| Keratosis pilaris | 0 (0.00)a | 0 (0.00)a | 1 (1.79)a | 3 (13.04)b | <0.001 |

| Papulosquamous diseases | (n = 2) | (n = 10) | (n = 31) | (n = 13) | |

| Pityriasis lichenoides | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 20 (64.52)a | 3 (23.08)b | 0.001 |

| Psoriasis | 0 (0.00) | 2 (20.00)ab | 4 (12.90)a | 8 (61.54)b | 0.006 |

| Pustular psoriasis | 2 (100.00)a | 4 (40.00)a | 2 (6.45)b | 0 (0.00)b | <0.001 |

| Connective tissue diseases | (n = 3) | (n = 4) | (n = 16) | (n = 21) | |

| Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus | 0 (0.00) | 1 (25.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0.017 |

| Neonatal lupus | 3 (100.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0) | 0 (0.00) | <0.001 |

| Dermatomyositis | 0 (0.00) | 1 (25.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0.017 |

| Vascular and lymphatic disorders | (n = 84) | (n = 5) | (n = 2) | (n = 2) | |

| Hemangioma | 72 (85.71) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | <0.001 |

| Vascular malformation | 3 (3.57)a | 2 (40.00)b | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0.006 |

| Venolymphatic malformation | 3 (3.57)a | 1 (20.00)a | 1 (50.00)b | 0 (0.00) | 0.014 |

| Lymphangioma circumscriptum | 1 (1.19)a | 0 (0.00) | 1 (50.00)b | 0 (0.00) | <0.001 |

| Fungal infections | (n = 2) | (n = 1) | (n = 11) | (n = 7) | |

| Tinea capitis | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 8 (72.73) | 0 (0.00) | 0.008 |

| Candidiasis | 2 (100.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | <0.001 |

| Vaginal candidiasis | 0 (0.00) | 1 (100.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | <0.001 |

| Pigmentary disorders | (n = 14) | (n = 7) | (n = 32) | (n = 7) | |

| Vitiligo | 0 (0.00)a | 4 (57.14)b | 30 (93.75)c | 2 (28.57)b | <0.001 |

| Nevus depigmentosus | 3 (21.43)a | 2 (28.57)a | 0 (0.00)b | 0 (0.00)b | 0.015 |

| Vesiculobullous diseases | (n = 9) | (n = 5) | (n = 3) | (n = 5) | |

| Epidermolysis bullosa | 7 (77.78) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0.002 |

| Chronic bullous dermatosis of childhood | 0 (0.00)a | 4 (80.00)b | 2 (66.67)b | 0 (0.00)a | 0.002 |

| Pemphigus vulgaris | 0 (0.00)a | 0 (0.00)a | 1 (33.33)ab | 4 (80.00)b | 0.003 |

| Miscellaneous | (n = 27) | (n = 22) | (n = 15) | (n = 26) | |

| Acne | 0 (0.00)a | 0 (0.00)a | 2 (13.33)a | 20 (76.92)b | <0.001 |

| Urticaria pigmentosa | 0 (0.00)a | 10 (45.45)b | 2 (13.33)a | 0 (0.00)a | <0.001 |

| Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis | 4 (14.81) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0.021 |

Different superscripts (a, b, c, ab) in the same row indicate a significant difference between groups (chi-squared test, multiple comparison test by Bonferroni, p < 0.05).

Eczematous disease was the most prevalent cutaneous disease in the study population. Variation and the distribution of prevalence of diseases in the different age groups were recorded. Prurigo nodularis and keratosis pilaris were significantly more frequently found in the adolescent group compared with the other groups (both p < 0.001), while atopic dermatitis was most frequently observed in the preschool and school age groups. Seborrheic dermatitis was found in the infant and toddler and adolescent groups. The distribution of other various cutaneous diseases in patients with eczematous disease is shown in Table 3.

Discussion

This study showed that the most prevalent skin disease group in our setting was eczematous disease. This result corresponds with a trend found in another university hospital in Central Thailand,3 as well as in school children in Hong Kong6 in which there was a shift away from cutaneous infection to eczematous disease for being the most prevalent pediatric skin disease. However, this pattern differs from that found in some countries, such as India,7 Napal,8 Turkey,9 and Argentina10 where infectious cutaneous diseases are still predominant.

Dermatitis (unspecified) was the most common skin disease found in our study population and atopic dermatitis was the second most common. An increasing prevalence of atopic dermatitis has been observed in many countries worldwide. Therefore, there is great concern regarding the issue of atopic disease in the Thai population. Many patients presented at our hospital to confirm the diagnosis of an allergic disease (e.g., atopic dermatitis) that was made in a skin clinic. Most pediatricians and residents were able to diagnose atopic dermatitis on the basis of clinical diagnostic criteria, and there were no cases of misdiagnosis of this condition during the study period. However, because of over concern for this disease, one case of juvenile dermatomyositis was misdiagnosed. The patient (girl, 4 years old) was treated for atopic dermatitis because her presenting symptom was erythematous patches on the peri-orbital area for at least 6 months before visiting the Pediatric Dermatology Clinic. The lesion on the peri-orbital area was diagnosed as a heliotrope rash, which is a characteristic feature of juvenile dermatomyositis. After a full physical examination and some laboratory tests were performed, the final diagnosis was changed to juvenile dermatomyositis. This example should be emphasized to general pediatricians as a possible pitfall when diagnosing similar cases in the future.

Infantile hemangioma was the third most common skin disease in our study population. The prevalence of infantile hemangioma was relatively high compared with that of other diseases. The reason for this finding may be because our hospital is a tertiary care center and is currently conducting research on infantile hemangioma in this region. Therefore, most hemangioma cases in northeast Thailand, as well as in a neighboring country, Laos PDR, are referred to our hospital for diagnosis and treatment of this disease. Although there were no misdiagnoses of infantile hemangioma during the study period, some other vascular and lymphatic malformations were misdiagnosed (40% of misdiagnoses). This misdiagnosis is currently a major problem in Thailand because the majority of general pediatricians are still unable to distinguish among various types of vascular birthmarks. Some patients who presented with vascular malformation were treated with oral propranolol because the pediatricians misdiagnosed the condition as infantile hemangioma. The Pediatric Dermatology Society of Thailand is currently developing treatment guidelines for infantile hemangioma in Thai children following the publication of the 2019 Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Infantile Hemangiomas.11 This information should be made widely available to encourage general pediatricians to place patients on an early referral track if there is a controversial diagnosis.

Neonatal lupus erythematosus was more prominent in girls than in boys in our study. This finding is similar to that of a previous study, which showed that female patients had a more predominant immune response to SSA/Ro antigens and a higher risk of neonatal lupus erythematosus than did male patients.12 Our finding is also similar to another study of cutaneous lupus erythematosus in children.13 Infantile hemangioma was also more prevalent in female than in male patients, which is consistent with the overall hemangioma data from previous studies conducted in various regions worldwide.14–18

Cutaneous infections were found in 60/769 (7.8%) patients. Impetigo was the most common cutaneous infection. None of the cases of impetigo were misdiagnosed. By contrast, the rate of misdiagnosis of the second most common cutaneous infection, tinea capitis, was as high as 62.50%. High percentages of misdiagnosis were also found in molluscum contagiosum and scabies. The large percentage of misdiagnosed common cutaneous diseases may be due to pediatric residents and general pediatricians being undereducated in the field of dermatology. Accurate recognition and appropriate management of these conditions should be emphasized in the dermatology curriculum for pediatric residents in the future.

A possible limitation of this study is that it was conducted in a university hospital that specializes in treatment for specific dermatological cases. Therefore, our results may not represent the true prevalence of skin diseases among children and adolescents in Northeast Thailand.

Conclusion

Misdiagnosis of common skin diseases should be a concern among general pediatricians. Accurate recognition and appropriate management of these conditions should be emphasized in the education of pediatric residents, as well as planning of dermatological healthcare programs and research that target children in Thailand in the future.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Dylan Southard for acting as an English language consultant.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.AlKhater SA, Dibo R, Al-Awam B. Prevalence and pattern of dermatological disorders in the pediatric emergency service. J Dermatol Dermatol Surg [Internet]. [cited 2016 Jun 29]; Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352241016300068

- 2.Furue M, Yamazaki S, Jimbow K, et al. Prevalence of dermatological disorders in Japan: a nationwide, cross-sectional, seasonal, multicenter, hospital-based study: prevalence of dermatological disorders in Japan. J Dermatol 2011; 38: 310–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wisuthsarewong W, Viravan S. Analysis of skin diseases in a referral pediatric dermatology clinic in Thailand. J Med Assoc Thai 2000; 83: 999–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tamer E, Ilhan MN, Polat M, et al. Prevalence of skin diseases among pediatric patients in Turkey. J Dermatol 2008; 35: 413–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jawade SA, Chugh VS, Gohil SK, et al. A clinico-etiological study of dermatoses in pediatric age group in tertiary health care center in South Gujarat region. Indian J Dermatol 2015; 60: 635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fung WK, Lo KK. Prevalence of skin disease among school children and adolescents in a student health service center in Hong Kong. Pediatr Dermatol 2000; 17: 440–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dogra S, Kumar B. Epidemiology of skin diseases in school children: a study from northern India. Pediatr Dermatol 2003; 20: 470–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poudyal Y, Ranjit A, Pathak S, et al. Pattern of pediatric dermatoses in a tertiary care hospital of Western Nepal. Dermatol Res Pract 2016; 2016: 6306404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Özçelik S, Kulaç İ, Yazıcı M, et al. Distribution of childhood skin diseases according to age and gender, a single institution experience. Turk Pediatri Ars 2018; 53: 105–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dei-Cas I, Carrizo D, Giri M, et al. Infectious skin disorders encountered in a pediatric emergency department of a tertiary care hospital in Argentina: a descriptive study. Int J Dermatol 2019; 58: 288–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krowchuk DP, Frieden IJ, Mancini AJ, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of infantile hemangiomas. Pediatrics 2019; 143: e20183475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miyagawa S, Dohi K, Yoshioka A, et al. Female predominance of immune response to SSA/Ro antigens and risk of neonatal lupus erythematosus. Br J Dermatol 1990; 123: 223–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.AlKharafi NNAH, Alsaeid K, AlSumait A, et al. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus in children: experience from a tertiary care pediatric dermatology clinic. Pediatr Dermatol 2016; 33: 200–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Techasatian L, Sanaphay V, Paopongsawan P, et al. Neonatal birthmarks: a prospective survey in 1000 neonates. Glob Pediatr Health [Internet]. 2019. Mar 29 [cited 2019 Apr 18]; 6. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6442070/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Kollipara R, Odhav A, Rentas KE, et al. Vascular anomalies in pediatric patients: updated classification, imaging, and therapy. Radiol Clin North Am 2013; 51: 659–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hook KP. Cutaneous vascular anomalies in the neonatal period. Semin Perinatol 2013; 37: 40–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fraulin FO, Flannigan RK, Sharma VK, et al. The epidemiological profile of the Vascular Birthmark Clinic at the Alberta Children’s Hospital. Can J Plast Surg 2012; 20: 67–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Léauté-Labrèze C, Prey S, Ezzedine K. Infantile haemangioma: part I. Pathophysiology, epidemiology, clinical features, life cycle and associated structural abnormalities. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol JEADV 2011; 25: 1245–1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]