The review presents the discovery of new dengue inhibitors by a phenotype-based approach.

The review presents the discovery of new dengue inhibitors by a phenotype-based approach.

Abstract

Dengue fever is the world's most prevalent mosquito-borne viral disease caused by the four serotypes of dengue virus, which are widely spread throughout tropical and sub-tropical countries. There has been an urgent need to identify an effective and safe dengue inhibitor as a therapeutic and a prophylactic agent for dengue fever. Most clinically approved antiviral drugs for the treatment of human immunodeficiency syndrome-1 (HIV-1) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) target virally encoded enzymes such as protease or polymerase. Inhibitors of these enzymes were typically identified by target-based screening followed by optimization via structure-based design. However, due to the lack of success to date of research efforts to identify dengue protease and polymerase inhibitors, alternative strategies for anti-dengue drug discovery need to be considered. As a complementary approach to the target-based drug discovery, phenotypic screening is a strategy often used in identification of new chemical starting points with novel mechanisms of action in the area of infectious diseases such as antibiotics, antivirals, and anti-parasitic agents. This article is an overview of recent reports on dengue phenotypic screens and discusses phenotype-based hit-to-lead chemistry optimization. The challenges encountered and the outlook on dengue phenotype-based lead discovery are discussed at the end of this article.

1. Introduction

Dengue is a mosquito-borne viral infection that causes flu-like symptoms, occasionally developing into potentially lethal severe dengue hemorrhagic fever or dengue shock syndrome. Until 1970, only 9 countries in tropical and sub-tropical regions experienced severe dengue outbreaks; however, the global incidence of dengue has dramatically increased over recent decades because of uncontrolled urban development, geometric growth of the human population, increased number of international travellers, wide spread of vector mosquitoes, and climate changes due to global warming. Currently, about half of the world's population is exposed to the risk of dengue infection.1,2 The first dengue vaccine, Dengvaxia®, developed by Sanofi-Pasteur, was licensed in December 2015 and has now been approved by 20 countries. It has been shown in clinical trials to be efficacious and safe for persons who have had a previous dengue infection. However, it has been reported to increase the risk of developing severe dengue and hospitalization in those who experience their first natural dengue infection after vaccination.3 As such, Dengvaxia® is currently restricted for use in endemic areas in persons ranging from 9 to 45 years.4 Vector control can be an option to prevent dengue disease; however, there are concerns about the environmental impact of mosquito spray and evolution of mosquito resistance to insecticides. There is no specific treatment available for dengue fever. Current treatment entirely relies on supportive therapy such as maintenance of the patients' body fluid volume and aggressive monitoring. Therefore, a potent and safe small-molecule dengue inhibitor can offer not only treatment of patients but also prophylactic use as a complementary approach to vaccines for travellers to endemic regions as well as for populations living in endemic areas. Small molecules that have entered into dengue clinical trials include chloroquine, celgosivir, balapiravir, prednisolone, lovastatin, ivermectin, ribavirin, and UV4; however, none of them showed antiviral activity and clinical benefits in dengue patients.5 Notably, all these compounds were repurposed from existing drugs or previously developed compounds for other viruses. None of the compounds specifically designed for dengue inhibitors have advanced to clinical trials, to our best knowledge. Therefore, discovery of a small-molecule dengue inhibitor would be a noteworthy breakthrough.6–9

The dengue virus (DENV) belongs to the genus Flavivirus of the family Flaviviridae and is divided into four closely related but distinct serotypes, all of which cause the disease. Infection with one serotype provides life-long immunity; however, cross-immunity to the other serotypes is only partial and temporary. It is known that a secondary infection by a different serotype can increase the risk of developing severe dengue.10 Hence, a dengue vaccine and a dengue antiviral should be equally effective across all four serotypes.

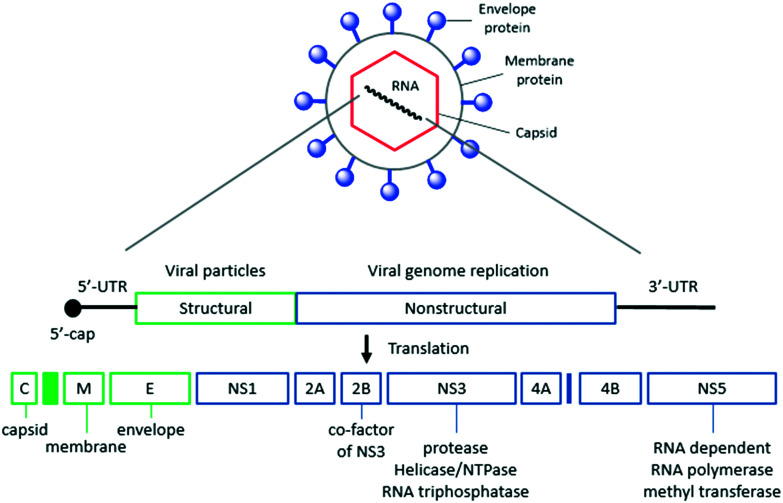

Dengue virus is a spherical enveloped virus, which is composed of viral RNA surrounded by a nucleocapsid and covered by a lipid envelope that contains the viral glycoproteins. The dengue viral genome is a single-stranded RNA of about 11 000 nucleotides and encodes three structural proteins (capsid, membrane precursor and envelope) and seven nonstructural proteins (NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, and NS5) (Fig. 1). The structures of five out of the ten proteins – C, M, E, NS3 (protease, NTPase and helicase) and NS5 (MTase and RdRp) – have been solved by X-ray or NMR. This structural information has provided a solid support for a target-based approach. Various academic and industry groups have actively pursued the discovery of dengue enzyme inhibitors such as NS3/NS2B protease, NS3 helicase, NS5 methyl transferase, and NS5 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase through enzyme activity-based high-throughput screening (HTS), fragment-based screening, virtual screening, and structure-based design. Although target-based approaches yielded clinically used drugs for the treatment of HIV and HCV, the discovery of dengue enzyme inhibitors has encountered limited progress due to lack of potent anti-dengue activity in cell-based assays.6–9

Fig. 1. Schematic structure of the dengue virus and outline of genome organization. UTR: untranslated region.

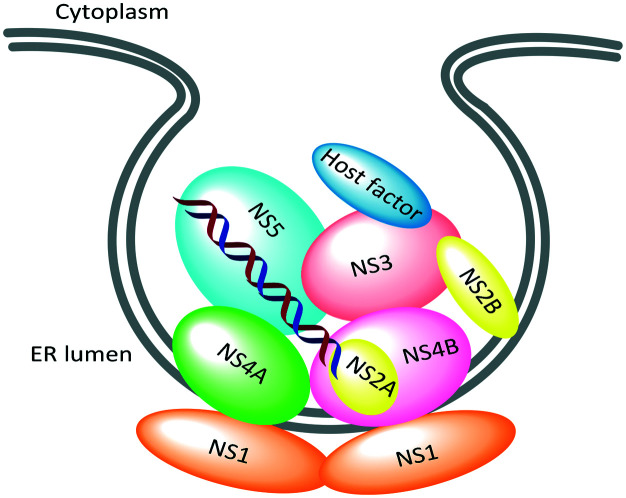

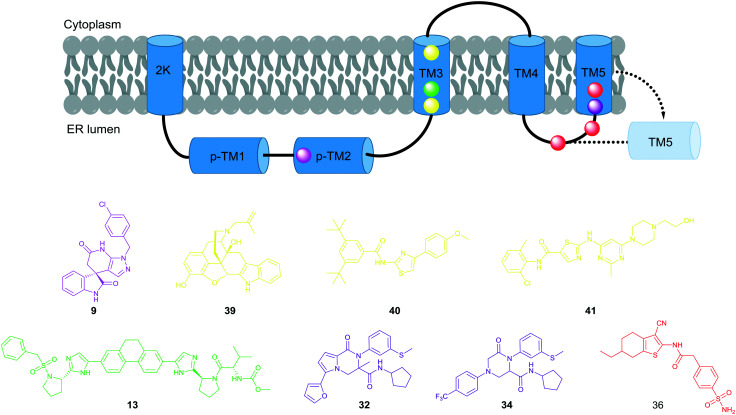

In recent years, there has been a resurgence of interest in a phenotype-based drug discovery approach based on its potential to address incomplete understanding of the complexity of diseases, advances in the tools for cell-based phenotypic screens, and the recent analysis that the majority of small-molecule first-in-class drugs discovered between 1999 and 2008 were discovered using phenotypic assays.11 There have been several reports of dengue phenotypic screens using whole virus infection assays and dengue subgenomic replicon cells.8,12 This phenotype-based approach has yielded a variety of inhibitor classes that act on host targets and complex viral targets such as PPI, membrane proteins, and replication complexes (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Schematic depiction of dengue viral replication complex.13.

Interestingly, none of the hits from phenotypic screens inhibit NS5 methyl transferase or polymerase. In phenotypic screens, the probability of identifying host target inhibitors is much higher than that of identifying viral target inhibitors because a much higher number of host proteins are involved in the dengue infection cycle as compared to the ten viral proteins. Host targeting inhibitors offer the advantage of a higher barrier to emergence of resistance as well as pan-serotype/-antiviral activities as compared with viral targeting inhibitors; however, it would be challenging to identify compounds that selectively inhibit the function of the host protein involved in the viral replication without affecting its normal cellular function to address safety concerns. As researchers have mainly used the dengue-2 assay for phenotypic screens, hit compounds do not necessarily exhibit pan-serotype inhibition due to lack of conservation of the amino acid sequence in some viral proteins. Therefore, a dengue phenotypic screen requires a strict filter to identify a viral targeting pan-serotypic active hit. Even if selected hits pass through the strict filters, it is a significant challenge for medicinal chemists to understand and rationalize structure–activity relationships (SARs) in the cell-based hit-to-lead optimization because structural changes may change not only target engagement but also cellular penetration and may hit multiple targets. In addition, compound cytotoxicity can have a profound effect on the viral replication process and may lead to inaccurate measurement of antiviral activity. As a consequence, the medicinal chemistry approach tends to be largely empirical and synthesis driven. This article strives to give an overview of medicinal chemistry optimization from phenotypic screening hits to identify their lead compounds and discusses the challenges and perspectives of phenotype-based dengue drug discovery.

2. New dengue inhibitors identified from phenotypic screens

The following sections will provide an overview of scientific accounts and patents describing dengue cell-based screening campaigns reported since 2014 and will summarize hit-to-lead medicinal chemistry toward lead candidates. This work is limited to the compounds which have reported their potency against all four serotypes and genetic validation to confirm potential viral targeting compounds. Compounds acting on host proteins will not be discussed here.

2.1. Thienopyridines

SIGA Technologies conducted a HTS of a 200 000 small-molecule library using a DENV-2 virus-induced cytopathic effect (CPE) assay to identify four discrete series of thienopyridine-2-carboxamide derivatives (Fig. 3).14–16

Fig. 3. Thienopyridine scaffolds identified from HTS by SIGA Technologies.

One of the hit series, ST-148 (1), displayed potent activity against DENV-2 with an EC50 of 0.016 μM and selective inhibition of dengue within the Flaviviridae family, suggesting that it could act on a virus target. ST-148 (1) was found to target the DENV capsid protein based on the compound resistance mapping.14 Additional biochemical and virological studies suggested that ST-148 (1) stabilizes the capsid protein self-interaction via binding to the dimer–dimer interface, thereby perturbing the assembly and disassembly of viral nucleocapsids by inducing structural rigidity.17 While ST-148 (1) showed anti-dengue activity for all four serotypes, its potency exhibited a broad range of EC50 of 0.20 to 2.59 μM. ST-148 (1) was supposed to suffer from low aqueous solubility considering its chemical structural features. Hit-to-lead chemistry efforts from ST-148 (1) were pursued to improve the potency with narrower EC50s across the four serotypes and to increase the aqueous solubility. Introducing the carboxylate function increased the DENV-2 potency to an EC50 of 0.006 μM but still had >20 fold weaker potency against DENV-1, -3, and -4 (compound 2). Incorporating the ionizable amine into the tricyclic core yielded compound 3, which showed equipotent activity against DENV-1, -2, and -3 with an EC50 range of 0.04 to 0.07 μM. As scaffold D was the most potent series with several analogs such as compound 4 and 5 possessing pan-serotype anti-dengue activity, this series emerged to be the lead sub-series. In particular, compound 5 exhibited single-digit nM potency across all four serotypes (Fig. 4).15,16

Fig. 4. SAR of selected thienopyridine analogs.

Although the structure of the lead compound has not been disclosed, it displayed pan-serotypic activity with EC50s of 0.002 to 0.010 μM without significant cytotoxicity (CC50 >25 μM). The lead compound is stable in liver and intestinal S9 and plasma and also negative in Ames and hERG assays. However, it had no detectable solubility in water, SGF, or pH 6.8 buffer. When this lead compound was dosed orally at 50 mg kg–1 once a day in a pharmacokinetic study in mice, Clast(24 h) exceeded the EC90 with an oral bioavailability of 13%. This compound demonstrated ∼1.5 log viremia reduction in an oral treatment of 50 mg kg–1 once a day in AG129 mice infected with DENV-2.15

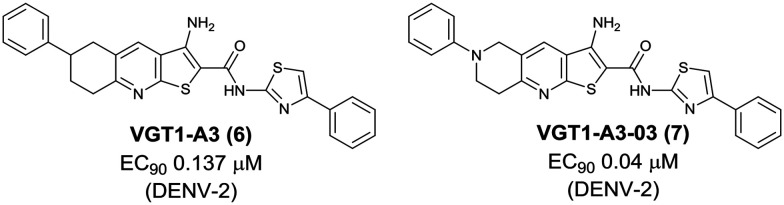

The group of Oregon Health & Science University independently identified the thienopyridine dengue inhibitor, VGT1-A3 (6), with an EC90 of 0.137 μM from a high-content immunofluorescence-based screen using DENV-2-infected HEK293 cells (human embryonic kidney 293 cells). Through SAR exploration with 39 new analogs, VGT1-A3-03 (7) was identified with improved potency (EC90 0.04 μM) and solubility (data not stated). While the antiviral activity of VGT1-A3 (6) was limited to DENV-2, VGT1-A3-03 (7) was active against DENV-1 and -4 as well as DENV-2. Like the ST-148 series, this compound class was confirmed to bind the dengue capsid pocket, which is involved in dimerization and associates with secreted virus particles (Fig. 5).18

Fig. 5. Thienopyridine dengue inhibitors identified by Oregon Health & Science University.

2.2. Spiropyrazolopyridones

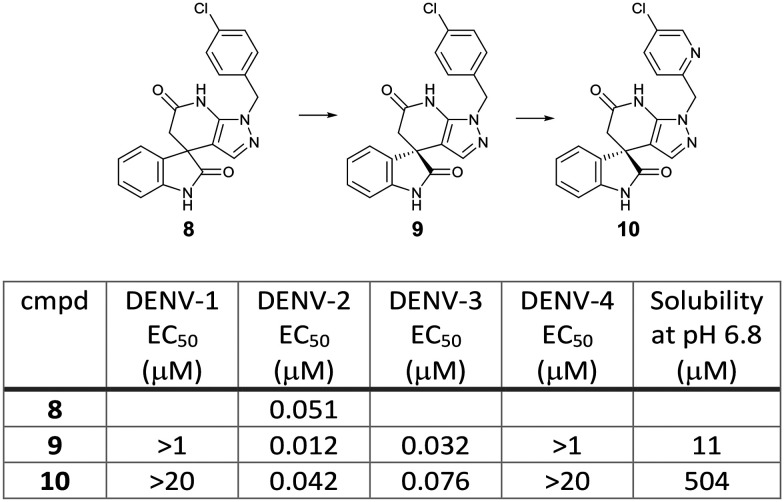

Novartis performed a phenotypic screening of a 1.8 million in-house compound library by using a DENV-2 replicon assay with HCV replicon as a counter assay to identify inhibitors that selectively suppress DENV replication. This screening campaign provided a spiropyrazolopyridone hit, 8, which potently inhibited the DENV-2 replicon (EC50 0.014 μM) but not the HCV replicon (EC50 >5 μM). A chiral HPLC separation of the hit compound 8 revealed that its R enantiomer, 9 (EC50 0.012 μM), was much more potent than the S enantiomer (EC50 >1 μM). Medicinal chemistry optimization of the spiropyrazolopyridone series yielded compound 10 with improved aqueous solubility and in vivo pharmacokinetic properties (EC50 0.042 μM, solubility 504 μM at pH 6.8). Compound 10 achieved 1.9 log viremia reduction at 3 × 50 mg kg–1 (BID) or 3 × 100 mg kg–1 (QD) oral doses started on day 0 post-infection in the AG129/DENV-2 mouse model. This compound still displayed efficacy in a delayed treatment at 10 or 24 hours after infection, but its efficacy turned to be not significant at 48 hours delayed treatment. The major issue of this class of compound is the lack of potency against DENV-1 and -4 despite being potent for both DENV-2 and -3. Resistance analysis showed that a mutation at valine-63 in DENV-2 NS4B protein (a nonenzymatic transmembrane protein and a component of the viral replication complex) conferred the resistance to compound 9, suggesting that the NS4B protein is a molecular target of the spiropyrazolopyridones. Sequence alignment of the NS4B among flaviviruses showed that valine-63 was conserved in DENV-2 and -3 but different in DENV-1 and -4 as well as the other flaviviruses. This result supported the DENV-2 and -3 specific activity of the spiropyrazolopyridone series (Fig. 6).19,20

Fig. 6. Spiropyrazolopyridone derivatives identified by Novartis.

Shi and Zhou et al. at the University of Texas Medical Branch followed up on this chemical series and pursued SAR optimization mainly focused on the N-substituents of the two amide moieties to acquire potency against all four serotypes. This research resulted in the identification of JMX0254 (11), which was active against DENV-1, -2, and -3 with EC50s of 0.78, 0.16, and 0.035 μM, respectively. JMX0254 (11) showed 2.4 log viremia reduction when it was orally dosed to the AG129 mouse model at 100 mg kg–1 (BID) for 3 days. However, JMX0254 (11) still suffered from the lack of potency against DENV-4 (EC50 >5 μM). The biotinylated compound enriched NS4B protein from cell lysates, and resistance studies further validated NS4B as the target of this class of compounds. Sequencing of the resistant viruses caused by compound 12 revealed that the amino acid was changed at the same position, valine-63 of the NS4B protein (Fig. 7).21

Fig. 7. Follow-up analogs of the spiropyrazolopyridone series identified by Shi and Zhou et al.

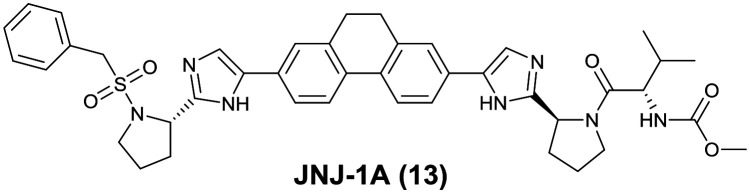

2.3. JNJ-1A

Janssen Pharmaceuticals screened their anti-HCV compound collection in a DENV-2 luciferase reporter replicon inhibition assay and selected compounds with single-digit micromolar potency. A hit-to-lead chemistry optimization from the selected compounds resulted in the identification of the lead compound, JNJ-1A (13), which inhibited the DENV-2 replicon with an EC50 of 0.7 μM. JNJ-1A (13) displayed equipotent activity against DENV-1, -2, and -4 with an EC50 value of 1–3 μM in an antiviral assay using RT-qPCR as read-out, but lacked activity against DENV-3. Resistance selection experiments with JNJ-1A (13) induced mutation at threonine-108 to isoleucine in NS4B, suggesting a mechanism of action linked to this protein. JNJ-1A (13) showed >25-fold increase in the EC50 value against the double mutant P104L/A119T, which was caused by the other NS4B inhibitor, NITD-618 (see Fig. 15). Due to the lack of pan-serotype activity, further medicinal chemistry efforts on this compound were stopped (Fig. 8).22

Fig. 15. Resistance to anti-dengue inhibitor mapping to NS4B protein.

Fig. 8. Structure of JNJ-1A identified by Janssen Pharmaceuticals.

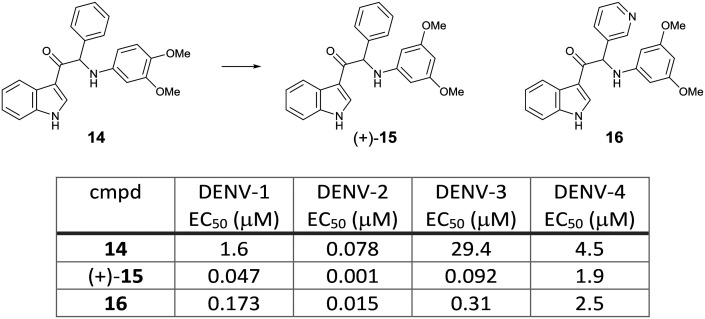

2.4. 3-Acyl-indoles

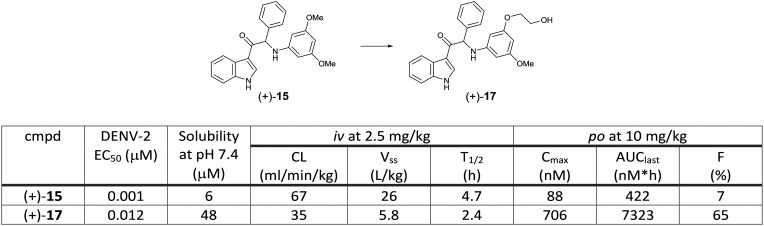

3-Acyl indole derivative 14 was identified from a phenotypic screening using a DENV-2 induced CPE assay by KU Leuven. Compound 14 showed potent in vitro activity against DENV-2 with an EC50 of 0.078 μM using a virus yield reduction assay (RT-qPCR read-out). Selection of in vitro drug resistance to this class of compounds led to the identification of multiple mutations in the NS4B protein (positions of the amino acid are not stated). A SAR study on the aniline moiety revealed that one methoxy group in the meta position was required to achieve potent activity. The 3,5-dimethoxy aniline analog 15 resulted in the most potent compound against DENV-2 (EC50 0.007 μM). A chiral HPLC separation of the racemic 15 provided the two enantiomers, which showed a marked difference in potency, with the (+)-enantiomer being more potent than the (–)-enantiomer. Next, a variety of modifications on the phenyl head part was investigated to identify the 3-pyridyl analog 16 with an EC50 of 0.015 μM. The hit compound and the selected compounds were evaluated against all serotypes. While the hit compound 14 showed potent activity against DENV-2, it had weak potency against the other three serotypes. The newly synthesized compounds (+)-15 and 16 improved the potency against DENV-2 as well as DENV-1 and -3; however, their DENV-4 EC50s still remained in the micromolar range (Fig. 9). Compound (+)-15 had the issue of high in vitro clearance in hepatocytes and low solubility, both of which were suspected to influence high clearance and low oral bioavailability in in vivo rat PK studies. To improve the solubility and metabolic stability, further optimization by introducing polar side chains let to the identification of compound (+)-17, which showed improved solubility and PK profile in rats (Fig. 10).23

Fig. 9. Pan-serotype activity of selected 3-acyl indole analogs identified by KU Leuven.

Fig. 10. Rat pharmacokinetic parameters of compounds (+)-15 and (+)-17.

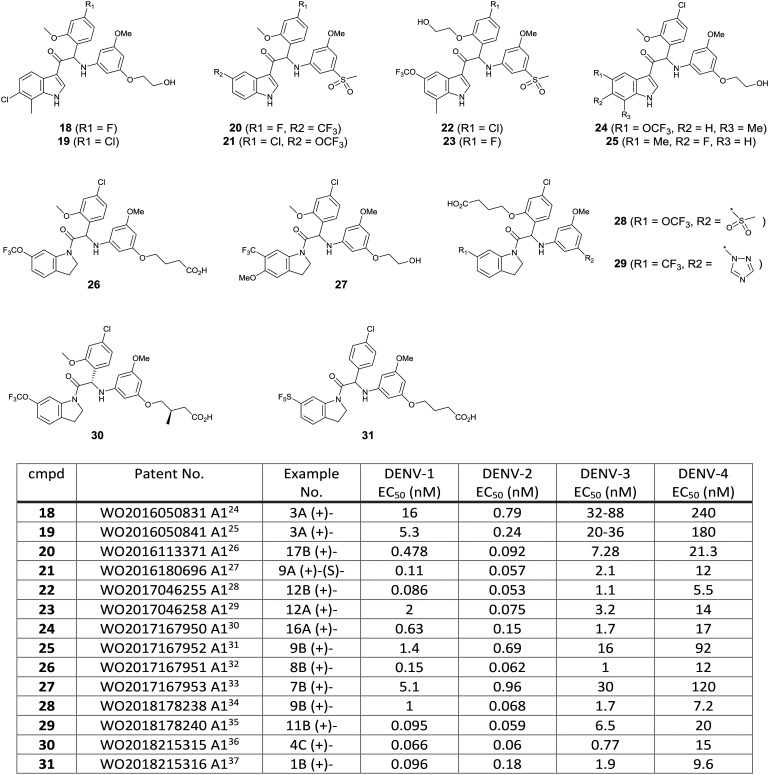

A total of 14 patent applications relating 3-acyl indole and N-acyl tetrahydroindole dengue virus inhibitors have been disclosed by KU Leuven and Janssen Pharmaceuticals jointly since 2016. Based on the exemplified structures and their EC50 results in these patents, it appeared that optimization around compound (+)-17 was pursued to balance out potency and physicochemical properties by introducing polar moieties such as alcohol, carboxylic acid, sulfone, and triazole (Fig. 11). Out of this compound series, compound 21 obtained an FDA orphan drug designation for the treatment of dengue virus infection on December 30, 2017, and it was advanced to the preclinical stage.

Fig. 11. Exemplified compounds included in the patent applications by KU Leuven and Janssen Pharmaceuticals.24–37 .

2.5. 2-Oxopiperazines

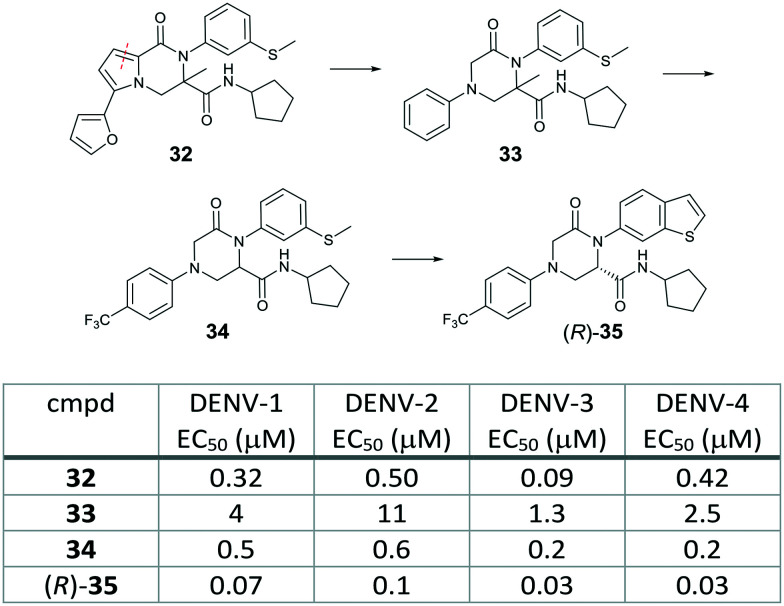

To identify new potent and pan-serotypic chemotypes, Novartis revamped their cell-based screen flow chart which turned to end up with the DENV-2 and -3 specific spiropyrazolopyridone scaffold. They conducted a HTS using a CPE-based DENV-2 infected Huh-7 cell line as a primary screen. Active hits were followed by testing for activity against all four serotypes using an A549 cell-based flavivirus immunodetection (CFI) assay with a high content imaging read-out. To help rule out host-targeting hits, their new flow chart also included a high content imaging based counter screen against Chikungunya virus, a closely related virus from the Alphaviridae family, as well as cytotoxicity assays using HepG2 and Huh-7 cells. This screening campaign led to the identification of two scaffolds as validated hits, one of which was a pyrrolopiperazinone (32) with sub-micromolar potency against all four serotypes (EC50 0.09–0.5 μM) without cytotoxicity (CC50 >50 μM). Resistance analysis showed that mutation at threonine-203 in NS4B conferred resistance to compound 32. A follow-up hit to lead chemistry from 32 by taking a scaffold morphing approach resulted in 2-oxopiperazine 33, which had single-digit micromolar potency with a good cytotoxicity window. Systematic SAR investigation around the 2-oxopiperazine core was started with the phenyl ring. The para-CF3 analog 34 gave a >6-fold improvement in the potency. It is noteworthy that the cross resistant analysis of 34 confirmed that NS4B remained the target of the 2-oxopiperazine analogs obtained via scaffold morphing from the HTS hit 32. The phenylthioether was replaced with the benzothiophene to identify compound (R)-35, which exhibited further improved potency with an EC50 of <0.1 μM for all four serotypes (Fig. 12). Its (S) enantiomer showed significant lower potency. Although the 2-oxopiperazine series provided potent pan-serotypic activity, it could not be further developed due to its limited solubility and high lipophilicicity.38

Fig. 12. Scaffold morphing to identify 2-oxopiperazine analogs from the dengue phenotypic screening hit by Novartis.

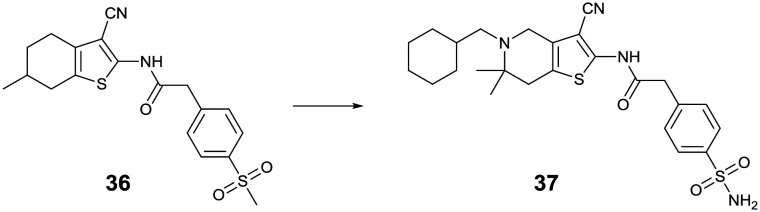

2.6. Tetrahydrothienopyridines

The other validated hit from the Novartis HTS was the tetrahydrobenzothiophene analog 36, which was also suggested to target the NS4B protein based on its resistance analysis. Extensive SAR investigation as well as optimization of its physicochemical properties identified an N-substituted tetrahydrothienopyridine derivative 37, which showed potent pan-serotypic activity and excellent oral efficacy in the DENV-2 infected AG129 mouse model with >1 log viremia reduction when orally dosed at 30 mg kg–1 once daily for three days (Fig. 13).39,40

Fig. 13. Tetrahydrothienopyridine dengue inhibitors identified by Novartis.

2.7. Benzimidazole

Shionogi performed a HTS of about 7000 compounds from their antiviral compound library using a DENV-2 infected baby hamster kidney (BHK-21) cell-based assay with a CPE read-out. This screening campaign obtained a benzimidazole hit, 38, which exhibited antiviral activity against all four dengue serotypes with an EC50 of 1.32–4.12 μM. Compound 38 also showed anti-DENV-2 activity in human kidney cell lines (A549). No antiviral activity against the other flaviviruses (WNV, JEV, YFV, ZKV) was observed, indicating that the antiviral activity of compound 38 is dengue specific. Compound 38 induced resistant virus associated with C87S mutation in the NS4A protein region, which was suggested to be the target of compound 38. Although compound 38 is the first compound targeting NS4A, medicinal chemistry effort around this compound has not been reported (Fig. 14).41

Fig. 14. Benzimidazole dengue NS4A inhibitor identified by Shionogi.

3. Outlook: challenges and opportunities for a phenotype-based approach to identify a new candidate for anti-dengue drug

Over the past five years, various research groups have disclosed structurally diverse scaffolds identified from their DENV phenotypic HTS campaigns. Resistance generation coupled with genome sequencing revealed that these newly identified chemical series act on the viral protein, capsid, NS4A, or NS4B, which does not exert any enzymatic activity. The dengue capsid protein is a structural element required for the nucleocapsid assembly that shelters the viral RNA genome. The thienopyridine capsid inhibitor, ST-148 (1), was proposed to stabilize capsid self-interactions based on docking and MD simulation studies. The NS4A and NS4B proteins are known to be implicated in the formation of the replication complex with the other non-structural proteins (Fig. 2); however, the mechanism of their inhibitors remains unknown. Considering their lack of enzymatic activity and their unknown exact functions, it is unlikely to identify these protein target inhibitors using target-based biochemical assays. On the other hand, no inhibitors to dengue methyl transferase or polymerase have been identified from phenotypic screens. These retrospective observations support the possibility that a phenotype-based approach would offer an opportunity to identify a first-in-class dengue inhibitor with a complex mode of action. Interestingly, the NS4B protein is the most frequently targeted by several structurally distinct compounds identified from phenotypic screens (Fig. 15). Notably, JNJ-1A (13), SDM25N (39),42 NITD-618 (40),43 and dasatinib (41)44 shared virus-resistant phenotypes, suggesting that they interact with the same sites (T108I, P104L, A119T) in the transmembrane domain-3 of NS4B despite their structural dissimilarity. Due to 60–80% homology of the NS4B protein across the four serotypes, not all hits from phenotypic screens exhibit pan-serotypic activity. For example, the spiropyrazolopyridone analogs showed the lack of potency for DENV-1 and -4 despite being potent for DENV-2 and -3. Resistance analysis suggests that they bind to the amino acid at position 63 of NS4B, which is not conserved across the four serotypes. The NS4B amino acids of the resistant mutants caused by the 2-oxopiperazine or the tetrahydrothienopyridine series (32, 34, and 36) are conserved across the four serotypes, reflecting the potent pan-serotypic activity exhibited by the optimized compounds, (R)-35 and 37 from these series. Based on these reported experiences, it appears to be hard to gain pan-serotypic activity starting from serotype-specific NS4B hits by cell-based chemical modifications. In the target-based drug discovery research, structural information has been used to build in selectivity over other targets and there are examples where structure was used to make multi-target compounds.45 This suggests that structural information can be used to optimize for multiple targets and should be relevant for pan-serotypic compounds as well. An X-ray structure of an isolated NS4B protein with the biologically relevant form, which is part of a replication complex assembly, has not been solved. A dengue NS4B binding assay has not been reported, while it could be developed like an HCV NS4B binding assay.46 Such atomic-level structural information or target-specific in vitro read-out may help to lead to NS4B pan-serotypic inhibitors as well as to NS4B-specific optimization. Otherwise, it would be critical to confirm pan-serotypic activity during the hit characterization stage in the phenotype-based approach. Based on lessons learned from the literature of DENV phenotype-based lead discovery, stringent hit selection criteria using all four serotype assays and extensive counter screenings are required to identify viral targeting compounds with pan-serotypic activity. A new assay technology such as high content imaging with automated microscopy enables rapid and robust screening of a large compound collection against all four serotypes and cytotoxicity.47,48

Unfavourable physicochemical properties (low solubility, high lipophilicity, high metabolic clearance) were often observed in compounds identified from a phenotype-based approach. This appears to be reflected in the results that most of the phenotypic screening hits act through lipophilic regions of the viral proteins such as capsid, NS4A, and NS4B. Nevertheless, medicinal chemistry optimization on 3-acyl indole and tetrahydrothieopyridine NS4B inhibitors led to the identification of lead compounds (+)-17 and 37 with improved solubility and pharmacokinetic properties. The lead compound JNJ-8359 (21) in the 3-acyl-indole series was designated as an orphan drug by FDA and was advanced to the preclinical stage. Although NS4B still needs to be validated clinically as an anti-dengue target, it is plausible to develop orally available DENV NS4B drugs with continued medicinal chemistry efforts, as seen for the development of HCV NS5A inhibitors.49 The thienopyridine capsid inhibitors have low aqueous solubility, which could restrict their drug development, although the lead compound demonstrated potent pan-serotypic anti-dengue activity along with good oral PK and efficacy. Further medicinal chemistry and/or formulation efforts are required to address the solubility issue for the discovery of a developable capsid inhibitor. While a deeper understanding of how the dengue capsid protein works during the viral life cycle will offer additional confidence in the design of capsid inhibitors, the recent preclinical data on the HIV-1 capsid inhibitor together with emerging phase I study results would also encourage development of a dengue capsid inhibitor not only for treatment but also for prophylactic use.50

Historically, the focus on anti-dengue drug discovery research has been centered on viral enzymes such as protease, polymerase, and methyl transferase; however, none of them have been advanced to clinical trials. To complement the enzyme target-based approach, the multifunctional protein target inhibitors which were identified from phenotypic screens may provide an even more promising candidate for the treatment of dengue fever. Given that DENV affects >100 countries worldwide and no dengue-specific treatment is available, it is hopeful that a new class of anti-dengue inhibitor will be advanced rapidly to the clinic.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Acknowledgments

I thank former and current colleagues who worked on dengue drug discovery at the Novartis Institute for Tropical Diseases (Singapore, Emeryville in USA) as well as colleagues in the Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research (Basel, CH; Cambridge, USA; Emeryville, USA), and the Genomics Institute of the Novartis Research Foundation (San Diego, USA) for invaluable discussions and insights. I am grateful to Dr. Christopher Sarko (Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research) for his critical reading of this manuscript. I also thank Dr. Jim Burgeson (SIGA Technologies, Inc.) for kindly sharing the reprint of their poster presentation, cited in ref. 15.

Biography

Fumiaki Yokokawa

Fumiaki Yokokawa is a senior principal scientist at Novartis Institute for Tropical Diseases (NITD), Emeryville, California. He joined NITD in Singapore in 2009. Since then he has been working on various drug discovery projects to identify preclinical development candidates for tuberculosis, dengue fever, and malaria. Before joining NITD, he worked for the CMC Development Laboratories at Shionogi & Co. Ltd. in Osaka, Japan, in 2008. From 2002 to 2008, he worked for Novartis Tsukuba Research Institute, where he worked on chronic pain and hypertension projects.

References

- Wilder-Smith A., Ooi E.-E., Horstick O., Wills B. Lancet. 2019;393:350–363. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32560-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO|Dengue and severe dengue, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dengue-and-severe-dengue.

- Halstead S. B. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2018;14:2158–2162. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2018.1445448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO Vaccine. 2017;35:1200–1201. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.10.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low J. G., Gatsinga R., Vasudevan S. G. and Sampath A., in Dengue and Zika: Control and Antiviral Treatment Strategies. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, ed. S. Hilgenfeld and S. Vasudevan, Springer, Singapore, 2018, vol. 1062, pp. 319–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnam M. A. M., Nitsche C., Boldescu V., Klein C. D. J. Med. Chem. 2016;59:5622–5649. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Y.-S., Zhou Y., Takagi T., Kameoka M., Kawashita N. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2018;66:191–206. doi: 10.1248/cpb.c17-00794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim S. P. Antiviral Res. 2019;163:156–178. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2018.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dighe S. N., Ekwudu O., Dua K., Chellappan D. K., Katavic P. L., Collet T. A. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019;176:431–455. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzman M. G., Alvarez M., Halstead S. B. Arch. Virol. 2013;158:1445–1459. doi: 10.1007/s00705-013-1645-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffat J. G., Vincent F., Lee J. A., Eder J., Prunoto M. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2017;16:531–543. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q.-Y., Zou B., Teague S. J., Shi P.-Y. and Desai M. C., Successful Strategies for the Discovery of Antiviral Drugs, ed. N. A. Neanwell, RSC Drug Discovery Series No. 32, RSC, 2013, pp. 63–80. [Google Scholar]

- Shi P.-Y. Science. 2014;343:849–850. doi: 10.1126/science.1251249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryd C. M., Dai D., Grosenbach D. W., Berhanu A., Jones K. F., Cardwell K. B., Schneider C., Wineinger K. A., Page J. M., Harver C., Stavale E., Tyavanagimatt S. R., Stone M. A., Bartenschlager R., Scaturro P., Hruby D. E., Jordan R. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013;57:15–25. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01429-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgeson J. R., Dai D., Berhanu A., Grosenbach D. W., Jones K. F., Cardwell K. B., Schneider C., Wineinger K. A., Page J. M., Harver C., Stavale E., Lovejoy C., Tyavanagimatt S. R., Jordan R., Byrd C. and Hruby D. E., 251th Am. Chem. Soc. (ACS) Natl. Meet., (March 13–17, San Diego) 2016, Abst. MEDI 130.

- Dai D., Burgeson J. R., Tyavanagimatt S. R., Bryd C. M. and Hruby D. E., WO2014089378A1, 2014.

- Scaturro P., Trist I. M. L., Paul D., Kumar A., Acosta E. G., Bryd C. M., Jordan R., Brancale A., Bartenschlager R. J. Virol. 2014;88:11540–11555. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01745-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. L., Sheridan K., Parkins C. J., Frueh L., Jemison A. L., Strode K., Dow G., Nilsen A., Hirsch A. J. Antiviral Res. 2018;155:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2018.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou B., Chan W. L., Ding M., Leong S. Y., Nilar S., Seah P. G., Liu W., Karuna R., Blasco F., Yip A., Chao A., Susila A., Dong H., Wang Q. Y., Xu H. Y., Chan K., Wan K. F., Gu F., Diagana T. T., Wagner T., Dix I., Shi P. Y., Smith P. W. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2015;6:344–348. doi: 10.1021/ml500521r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q. Y., Dong H., Zou B., Karuna R., Wan K. F., Zou J., Susila A., Yip A., Shan C., Yeo K. L., Xu H. Y., Ding M., Chan W. L., Gu F., Seah P. G., Liu W., Lakshminarayana S. B., Kang C. B., Lescar J., Blasco F., Smith P. W., Shi P. Y. J. Virol. 2015;89:8233–8244. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00855-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J., Xie X., Ye N., Zou J., Chen H., White M. A., Shi P. Y., Zhou J. J. Med. Chem. 2019;62:7941–7960. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Morales I., Geluykens P., Clynhens M., Strijbos R., Goethals O., Megens S., Verheyen N., Last S., McGowan D., Coesemans E., Boeck B. D., Stoops B., Devogelaere B., Pauwels F., Vandyck K., Berke J. M., Raboisson P., Simmen K., Lory P., Loock M. V. Antiviral Res. 2017;147:149–158. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardiot D., Koukni M., Smets W., Carlens G., McNaughton M., Kaptein S., Dallmeier K., Chaltin P., Neyts J., Marchand A. J. Med. Chem. 2018;61:8390–8401. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesteleyn B. R. R., Bofanti J.-F., Jonckers T. H. M., Raboisson P. J.-M. B., Bardiot D. A. M.-E. and Marchand A. D. M., WO2016050831A1, 2016.

- Kesteleyn B. R. R., Bofanti J.-F., Jonckers T. H. M., Raboisson P. J.-M. B., Bardiot D. A. M.-E. and Marchand A. D. M., WO2016050841A1, 2016.

- Kesteleyn B. R. R., Bofanti J.-F., Jonckers T. H. M., Raboisson P. J.-M. B., Bardiot D. A. M.-E. and Marchand A. D. M., WO2016113371A1, 2016.

- Kesteleyn B. R. R., Bofanti J.-F., Jonckers T. H. M., Raboisson P. J.-M. B., Bardiot D. A. M.-E. and Marchand A. D. M., WO2016180696A1, 2016.

- Kesteleyn B. R. R., Raboisson P. J.-M. B., Bofanti J.-F., Jonckers T. H. M., Bardiot D. A. M.-E. and Marchand A. D. M., WO2017046255A1, 2017.

- Kesteleyn B. R. R., Raboisson P. J.-M. B., Bofanti J.-F., Jonckers T. H. M., Bardiot D. A. M.-E. and Marchand A. D. M., WO2017046258A1, 2017.

- Bardiot D. A. M.-E., Bofanti J.-F., Kesteleyn B. R. R., Marchand A. D. M. and Raboisson P. J.-M. B., WO2017167950A1, 2017.

- Bardiot D. A. M.-E., Bofanti J.-F., Coesemans E., Kesteleyn B. R. R., Marchand A. D. M. and Raboisson P. J.-M. B., WO2017167952A1, 2017.

- Kesteleyn B. R. R., Raboisson P. J.-M. B., Bofanti J.-F., Bardiot D. A. M.-E. and Marchand A. D. M., WO2017167951A1, 2017.

- Bardiot D. A. M.-E., Bofanti J.-F., Kesteleyn B. R. R., Marchand A. D. M. and Raboisson P. J.-M. B., WO2017167953A1, 2017.

- Bardiot D. A. M.-E., Kesteleyn B. R. R., Bofanti J.-M., Raboisson P. J.-M. B. and Marchand A. D. M., WO2018178238A1, 2018.

- Kesteleyn B. R. R., Bofanti J.-F., Coesemans E., Raboisson P. J.-M. B., Marchand A. D. M. and Bardiot D. A. M.-E., WO2018178240A1, 2018.

- Bofanti J.-F., Kesteleyn B. R. R., Bardiot D. A. M.-E., Marchand A. D. M., Coesemans E., Fortin J. M. C., Mercey G. J. M. and Raboisson P. J.-M. B., WO2018215315A1, 2018.

- Bofanti J.-F., Kesteleyn B. R. R., Bardiot D. A. M.-E., Marchand A. D. M., Coesemans E., DeBoeck B. C. A. G. and Raboisson P. J.-M. B., WO2018215316A1, 2018.

- Kounde C. S., Yeo H.-Q., Wang Q.-Y., Wan K. F., Dong H., Karuna R., Dix I., Wagner T., Zou B., Simon O., Bonamy G. M. C., Yeung B. K. S., Yokokawa F. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017;27:1385–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kounde C., Sim W. L. S., Simon O., Wang G., Yeo H. Q., Yeung B. K. S., Yokokawa F. and Zou B., WO2019244047A1, 2019.

- Yokokawa F., Simon O., Sim S., Zou B., Ding M., Chan W.-L., Kounde C. S., Yeo H.-Q., Wang G., Wang Q.-Y., Wan K. F., Dong H., Karuna R., Lim S. P., Lakshminarayana S. B., Moquin S., Lee C. B., Chan K., Chao A., Sarko C., Yeung B. K. S. and Gu F., 68th Annu. Meet Am. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. (Nov 20–24, National Harbor) 2019, Abst 181. Detailed manuscript in preparation.

- Nobori H., Toba S., Yoshida R., Hall W. W., Orba Y., Sawa H., Sato A. Antiviral Res. 2018;155:60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2018.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Cleef K. W. R., Overheul G. J., Thomassen M. C., Kaptein S. J. F., Davidson A. D., Jacobs M., Nytes J., van Kuppeveld F. J. M., van Rij R. O. Antiviral Res. 2013;90:165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie X., Wang Q.-Y., Xu H. Y., Qing M., Kramer L., Yuan Z., Shi P.-Y. J. Virol. 2011;85:11183–11195. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05468-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wispelaere M., LaCroix A. J., Yang P. L. J. Virol. 2013;87:7367–7381. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00632-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Yosief H. O., Dai L., Huang H., Dhawan G., Zhang X., Muthengi A. M., Roberts J., Buckley D. L., Perry J. A., Wu L., Bradner J. E., Qi J., Zhang W. J. Med. Chem. 2018;61:7785–7795. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shotwell J. B., Baskaran S., Chong P., Creech K. L., Crosby R. M., Dickson H., Fang J., Garrido D., Mathis A., Maung J., Parks D. J., Pouliot J. J., Price D. J., Rai R., Seal, III J. W., Schmitz U., Tai V. W. F., Thomson M., Xie M., Xiong Z. Z., Peat A. J. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2012;3:565–569. doi: 10.1021/ml300090x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shum D., Smith J. L., Hirsch A. J., Bhinder B., Radu C., Stein D. A., Nelson J. A., Früh K., Djaballah H. Assay Drug Dev. Technol. 2010;8:553–570. doi: 10.1089/adt.2010.0321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodin P., Christophe T. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2011;15:534–539. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2011.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belema M., Lopez O. D., Bender J. A., Romine J. L., Laurent D. R. St., Langley D. R., Lemm J. A., O'Boyle, II D. R., Sun J.-H., Wang C., Fridell R. A., Meanwell N. A. J. Med. Chem. 2014;57:1643–1672. doi: 10.1021/jm401793m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yant S. R., Mulato A., Hansen D., Tse W. C., Niedziela-Majika A., Zhang J. R., Stepan G. J., Jin D., Wong M. H., Perreira J. M., Singer E., Papalia G. A., Hu E. Y., Zheng J., Lu B., Schroeder S. D., Chou K., Ahmadyar S., Liclican A., Yu H., Novikov N., Paoli E., Gonik D., Ram R. R., Hung M., McDougall W. M., Brass A. L., Sundquist W. I., Cihlar T., Link L. O. Nat. Med. 2019;25:1377–1384. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0560-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]