Abstract

BACKGROUND

Intraoperative magnetic resonance imaging (IO-MRI) provides real-time assessment of extent of resection of brain tumor. Development of new enhancement during IO-MRI can confound interpretation of residual enhancing tumor, although the incidence of this finding is unknown.

OBJECTIVE

To determine the frequency of new enhancement during brain tumor resection on intraoperative 3 Tesla (3T) MRI. To optimize the postoperative imaging window after brain tumor resection using 1.5 and 3T MRI.

METHODS

We retrospectively evaluated 64 IO-MRI performed for patients with enhancing brain lesions referred for biopsy or resection as well as a subset with an early postoperative MRI (EP-MRI) within 72 h of surgery (N = 42), and a subset with a late postoperative MRI (LP-MRI) performed between 120 h and 8 wk postsurgery (N = 34). Three radiologists assessed for new enhancement on IO-MRI, and change in enhancement on available EP-MRI and LP-MRI. Consensus was determined by majority response. Inter-rater agreement was assessed using percentage agreement.

RESULTS

A total of 10 out of 64 (16%) of the IO-MRI demonstrated new enhancement. Seven of 10 patients with available EP-MRI demonstrated decreased/resolved enhancement. One out of 42 (2%) of the EP-MRI demonstrated new enhancement, which decreased on LP-MRI. Agreement was 74% for the assessment of new enhancement on IO-MRI and 81% for the assessment of new enhancement on the EP-MRI.

CONCLUSION

New enhancement occurs in intraoperative 3T MRI in 16% of patients after brain tumor resection, which decreases or resolves on subsequent MRI within 72 h of surgery. Our findings indicate the opportunity for further study to optimize the postoperative imaging window.

Keywords: Brain tumors, Gadolinium, Glioblastoma, Magnetic resonance imaging

ABBREVIATIONS

- EP-MRI

early postoperative magnetic resonance imaging

- GBM

glioblastoma multiforme

- GTR

gross total resection

- LP-MRI

late postoperative magnetic resonance imaging

- LGG

low-grade gliomas

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- IO-MRI

intraoperative magnetic resonance imaging

- 3T

3 Tesla

- TPRE

transient procedure-related enhancement

- WHO

World Health Organization

Gross total resection (GTR) of glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) has been shown to be a significant prognostic factor for overall survival.1-6 This therapeutic benefit of maximal resection has been shown to extend to other primary and secondary brain tumors as well, improving overall survival, prolonging disease-free interval, and reducing local recurrence.7-10 Accurate intraoperative assessment of degree of resection by the neurosurgeon has been shown to be difficult, particularly in patients with infiltrative tumors.11 Early postoperative contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), typically obtained less than 72 h post-op, is the test of choice for determining extent of resection of enhancing tumors, but does not provide the opportunity for further resection without a second surgery.12 Intraoperative MRI (IO-MRI) provides imaging assessment of residual tumor while the patient is still under anesthesia, allowing additional resection within the same surgical session.13 Multiple studies have demonstrated the benefit of IO-MRI guidance to assist in maximizing GTR in patients with glioma,14-16 but a number of studies have reported the presence of new enhancement on IO-MRI immediately after mass resection.17,18 Thought to be caused by leakage of contrast into the resection cavity and/or iatrogenic blood-brain barrier disruption, this new enhancement can make assessment of residual tumor challenging. A better understanding of the frequency and temporal evolution of such new IO-MRI enhancement may help improve interpretation of IO-MRI and hence completeness and safety of brain tumor resection. Understanding these issues may also improve interpretation of early postoperative MRI (EP-MRI), on which detection of residual tumor is an important prognostic factor and can guide decisions regarding adjuvant therapy.19

Studies carried out on 1.5-Tesla MRI systems have shown that imaging patients within 72 h of surgery allows accurate assessment for residual tumor, because postoperative contrast enhancement related to granulation tissue, typically is not observed until after 72 h.19,20 More recent research on higher field 3 Tesla (3T) MRI, has demonstrated postoperative reactive enhancement in approximately one-third of patients even within 72 h of surgery,21 but the frequency of this new reactive enhancement on 3T IO-MRI remains to be determined.

The aim of this study was to determine the frequency of new postoperative enhancement during brain tumor resection using high-field 3T IO-MRI. We hypothesized that new contrast enhancement would be detectable in a subset of patients undergoing IO-MRI and would have resolved in most cases on EP-MRI performed within 72 h of surgery. A secondary aim was to study the frequency of new enhancement on EP-MRI performed within 72 h of surgery in order to explore whether the 72-h remains an optimal postoperative imaging window for 3T MRI following tumor resection.

METHODS

Patient Population

This retrospective study was Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act compliant and approved by the Institutional Review Board. All patients provided consent for inclusion in this retrospective study. Consecutive intraoperative brain MRI examinations performed at our hospital from January 2011 to March 2018, yielding an initial group of 257 patients. A manual review was then performed to select examinations for which intravenous contrast was administered (N = 143). Inclusion criteria consisted of all patients with the working diagnosis of an enhancing intra-axial brain tumor. Of these patients, those not undergoing open biopsy or resection were removed. A final sample size (N = 64) consisted of patients with intra-axial lesions with attempted biopsy and/or resection at the time of the intraoperative contrast-enhanced MRI (IO-MRI) (35 male/29 female). Of this group, a subset (N = 42) had an early postoperative contrast-enhanced MRI performed within 72 h postsurgery (EP-MRI). Also, of this group, a subset (N = 35) had late postoperative contrast-enhanced MRI performed more than 120 h and within 8 wk of surgery (late postoperative MRI (LP-MRI)). The average age at the time of surgery was 52.5 yr (range 20-75 yr). A total of 29 of 64 (45%) patients had a history of prior craniotomy for mass resection.

Lesion pathology included the following groups: high-grade glial tumors, low-grade glial tumors, intraparenchymal metastases, and vasculitis. The high-grade glial-tumor subset consisted of World Health Organization (WHO) grade III or IV glioma (N = 44 patients). There were 12 patients with low-grade gliomas (LGG), consisting of WHO grade I or II tumors. There were 7 patients with brain metastases. One patient had an enhancing lesion with postresection pathology demonstrating activate vasculitis consistent with amyloid angiopathy.

MRI Parameters

Preoperative MRI, EP-MRI, and LP-MRI were performed on 1.5 or 3.0 T systems. All imaging for IO-MRI was performed on a 3.0 T MAGNETOM Verio MRI (Siemens Healthcare GmbH, Erlangen, Germany). Depending on the imaging needs of the procedure, IO-MRI was performed at varying stages of the tumor resection or immediately at the end of the procedure images were acquired with the patient's head turned in the operative position and secured in an MRI compatible 3-point pin fixation head holder (IMRIS, Minnetonka, Minnesota). At the time of imaging, the surgical resection was paused. The surgical cavity was filled with normal saline and skin edges temporarily approximated without the underlying bone flap. An 8-channel flexible receive only phased array coil was secured around the patient's head. After a brief safety pause to ensure all MRI incompatible equipment was removed, the MRI scanner was brought into the operating room. IO-MRI included pre- and postcontrast axial T1-weighted spin echo sequences (TR 608-782 msec, TE 10-20 msec, and slice thickness 3.75-5 mm), and/or axial T1-weighted Magnetization Prepared Rapid Acquisition Gradient Echo sequences (TR 1540-1900 msec, TE 2.67-3.41 msec, and slice thickness 0.9-1.5 mm). Gadolinium-based contrast agents (Gadavist or Magnevist; Bayer Pharma AG, Leverkusen, Germany) were administered with a standard weight-based dose of 0.1 mmol per kg. All IO-MRI images were jointly reviewed by the neurosurgeon and neuroradiologist at the time of surgical resection in the operating suite to determine residual tumor burden prior to pursing further resection.

Contrast delay was estimated by calculating the time difference in minutes between the earliest performed postcontrast-enhanced sequence and latest performed precontrast sequence if available.

Assessment of Enhancement Characteristics

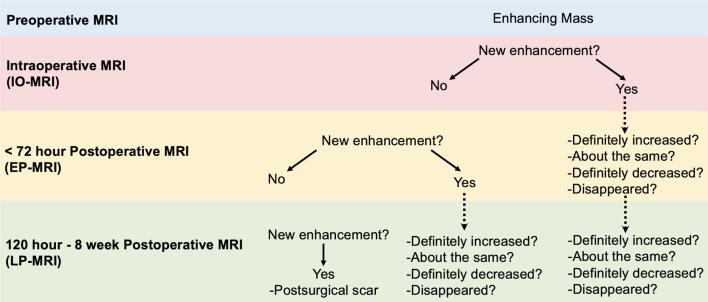

Three blinded readers, 2 subspecialty trained neuroradiologists with 23 (G.S.Y) and 13 yr (R.Y.H.) of radiology experience, and a neuroradiology fellow with 5 yr of radiology experience (M.E.C) independently assessed each of the scans for the 64 patients. New enhancement present on the IO-MRI was assessed on EP-MRI. Similarly, new enhancement on EP-MRI was assessed on LP-MRI. This new enhancement on IO-MRI or EP-MRI was evaluated on EP-MRI or LP-MRI, respectively, and reported as “definitively increased, stayed the same, definitively decreased”, or “resolved.” Enhancing tumor seen on preoperative MRI was deemed residual disease on IO-MRI. New enhancement on LP-MRI compared to EP-MRI was deemed manipulation-related contrast enhancement given this has been shown to develop starting 72 h after surgery.19,20,22 New enhancement of the dura mater was ignored for our study given that this phenomenon is often observed, especially for intraparenchymal lesions near the dura.23 The assessment of enhancement characteristics for each of the patient's scans is demonstrated visually by the workflow displayed in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Procedural workflow for each patient series of exams. Note: EP-MRI and LP-MRI was used for comparison when available.

Data Analysis

The consensus assessment for presence or absence of new enhancement on IO-MRI and EP-MRI was determined by the majority response. Inter-rater agreement was assessed using percentage agreement. For the determination of significant factors seen in the subset with new enhancement on IO-MRI compared to the patient sample the chi-squared test was used.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Patient characteristics are included in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Patient Demographics

| Age at time of surgery | Gender | Pathology of brain tumor |

|---|---|---|

| Mean, 52.5 yr | Female, 29 | High-grade glioma (44) |

| Range, 20 to 75 yr | Male, 35 | LGG (12) |

| Metastasis (7) | ||

| Vasculitis (1) |

Scan Intervals

The time interval between the preoperative contrast-enhanced MRI and the IO-MRI was on average 11.4 d, with a standard deviation of 10.5 d (0.2-45.1 d). EP-MRI was performed on average 37 h postsurgery, with a standard deviation of 12 h (range 9-59 h). LP-MRI was performed on average 28.1 d postsurgery, with a standard deviation of 10.7 d (range 13.3-49.1 d). The proportion of exams from each time point performed at 1.5 and 3T is displayed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Magnet Strength Breakdown of Each Exam

| Preoperative MRI | IO-MRI | EP-MRI | LP-MRI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total exams | 64 | 64 | 42 | 33 |

| 3T (%) | 34 (53.1%) | 64 (100%) | 21 (50%) | 20 (60.6%) |

| 1.5T (%) | 30 (46.9%) | 0 (0%) | 21 (50%) | 13 (39.4%) |

Proportion of exams from each time point performed at 1.5T and 3T.

IO-MRI = intraoperative MRI; EP-MRI = early postoperative MRI; LP-MRI = late postoperative MRI.

Inter-Rater Agreement

For the assessment of new enhancement on the IO-MRI, agreement was 74% among the 3 readers. For the assessment of new enhancement on the EP-MRI, agreement was 81% among the 3 readers.

Assessment of New Enhancement on IO-MRI

In all 16% (10/64) of the patients demonstrated new enhancement on the IO-MRI, detected on either spin echo, magnetization prepared rapid gradient echo, or both sequences. With the exception of type of contrast agent, chi-squared test demonstrated no statistical difference in the detection of new enhancement in comparing multiple factors, as detailed in Table 3. Of those 10 patients, 7 patients also had an EP-MRI that was used to assess the change in enhancement, 5 of which had decreased and 2 of which had resolved on either 3T or 1.5T imaging (Figures 2 and 3). These 10 patients consisted 6 with high-grade glial tumors, 2 with low-grade glial tumors, 1 with brain metastasis, and 1 with vasculitis. The sites of new enhancement were seen at 2 locations on the 10 exams: the margins of the resection cavity and along the surgical tract.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of Imaging Parameters in Patients with New Intraoperative Enhancement

| Demographic | TPRE on IO-MRI n = 10 | No-TPRE n = 54 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average age at surgery (years) | 56.4 | 51.8 | .36 |

| Pathology | |||

| High-grade glioma | 6 (60%) | 38 (70%) | .53 |

| LGG | 2 (20%) | 10 (19%) | .94 |

| Metastasis | 1 (10%) | 6 (11%) | .93 |

| Vasculitis | 1 (10%) | 0 (0%) | .02 |

| Prior craniotomy | 2 (20%) | 27 (50%) | .08 |

| Contrast Agent | |||

| Gadavist ®* | 8 (80%) | 15 (28%) | .002 |

| Magnevist ®* | 1 (10%) | 21 (39%) | .08 |

| Constrast volume (mL) | 9.8 | 13.1 | .09 |

| Average calculated contrast delay (minutes) | 18.9 | 16.2 | .25 |

| T1 SE postcontrast only (no MP-RAGE) | 1 (10%) | 11 (20%) | .46 |

| IO-MRI imaging time points | |||

| Pre-resection | 0 (0%) | 6 (9.3%) | .32 |

| Mid-resection | 8 (80%) | 45 (83%) | .82 |

| Post-resection | 2 (20%) | 25 (46%) | .13 |

Demographics comparing the patients for which new TPRE was seen on 3T intraoperative MRI (IO-MRI) compared to those for which TPRE was not seen.

SE = spin echo; MP-RAGE = magnetization prepared rapid gradient echo.

*For data available

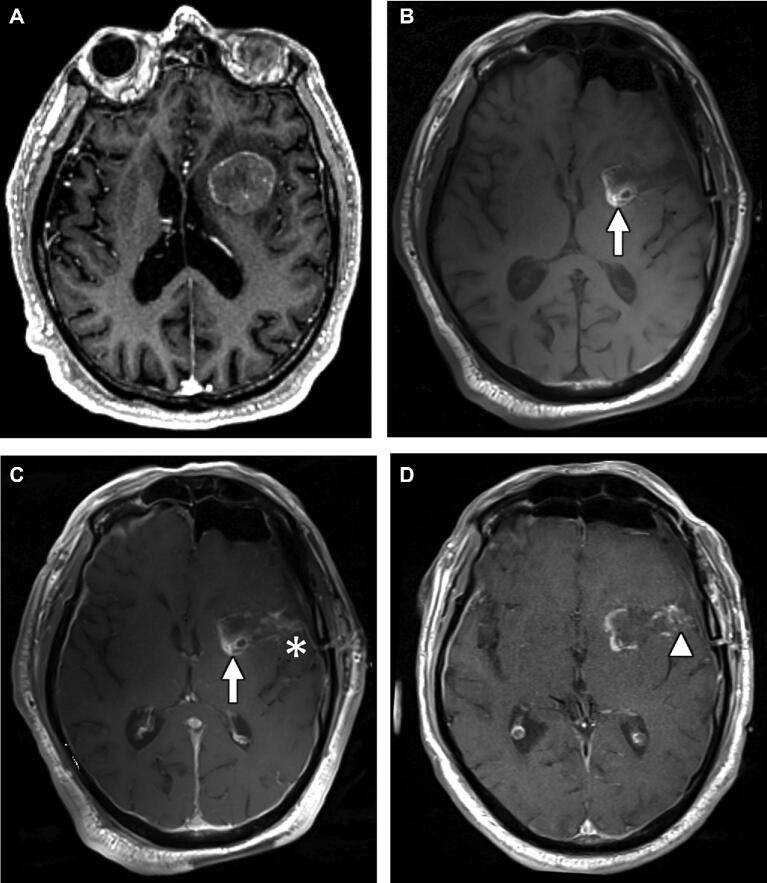

FIGURE 2.

A 73-yr-old man with esophageal adenocarcinoma with brain metastasis. A, Axial T1 postcontrast image from preoperative MRI demonstrating enhancing mass centered at the left insular cortex. Axial T1 precontrast B and postcontrast C images from intraoperative exam showing T1-shortening at the medial aspect of the resection cavity representing packing material (arrow), and new enhancement along the lateral margin of the surgical tract compared to presurgical MRI (asterisk), which decreased on T1 postcontrast sequence of EP-MRI D (arrowhead).

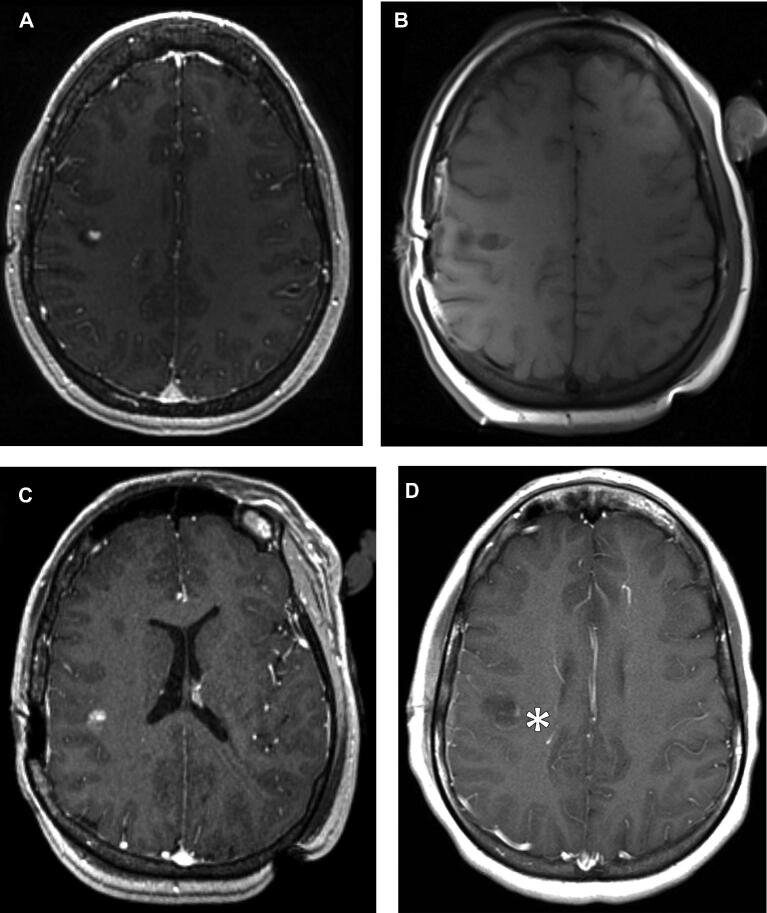

FIGURE 3.

A 29-yr-old female with recurrent low-grade glial tumor. A, Axial T1 postcontrast image from preoperative MRI demonstrating enhancing focus representing recurrent tumor at the resection cavity along the right central sulcus. Axial T1 precontrast B and postcontrast C images from intraoperative exam, demonstrating new enhancement within the resection cavity (arrow), which decreased on the T1 postcontrast sequence from EP-MRI D (asterisk).

Postcontrast Injection Time Delay

The estimated time delay between contrast injection and postcontrast imaging was on average 17 min, with a standard deviation of 7.1 min (range 5-35 min). Chi-squared test demonstrated no statistically significant outlier in injection time delay for any of the patients with new enhancement on IO-MRI.

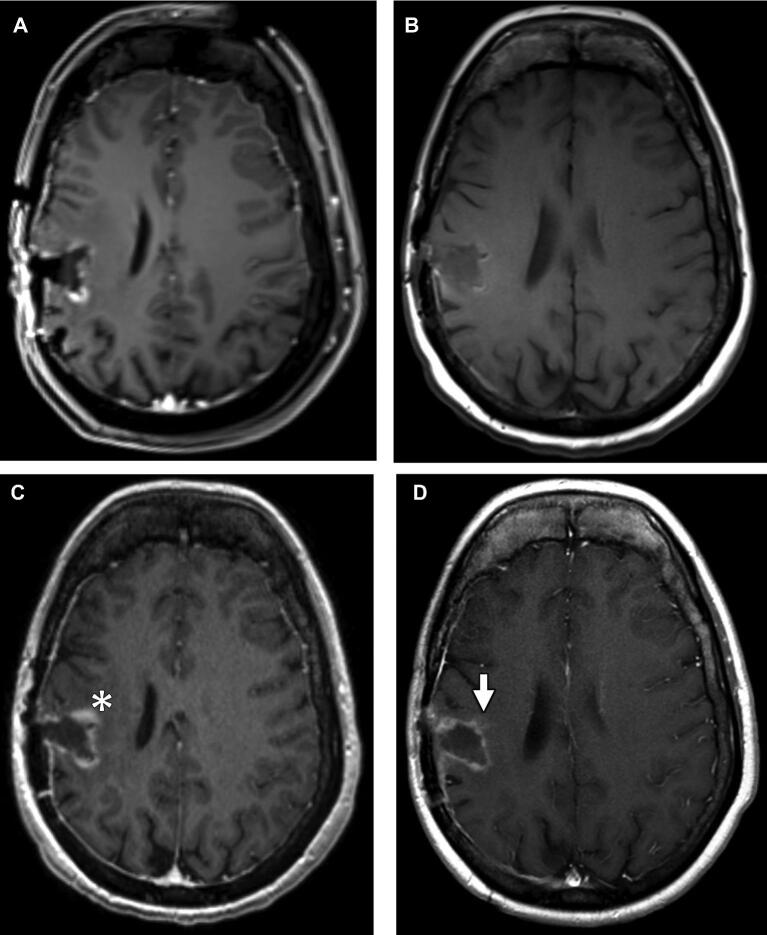

Exploratory Analysis of EP-MRI

One of the 42 patients for which EP-MRI was available demonstrated new enhancement. This 3T exam was performed 49 h after surgery. This new enhancement seen on EP-MRI decreased on the associated 1.5T LP-MRI (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

A 26-yr-old female with glioblastoma multiforme. A, Axial T1 postcontrast image from intraoperative MRI demonstrating marginal linear enhancement at the right frontoparietal resection cavity not definitively new from preoperative imaging. Axial T1 pre- B and postcontrast C images from EP-MRI demonstrating minimal T1-shortening along the margins of the surgical cavity likely representing blood products, and new enhancement along the anteromedial aspect of the surgical tract compared to intraoperative MRI (asterisk). This enhancement was noted to decrease on T1 postcontrast image D from late postoperative MRI performed 27 d afterwards (arrow).

DISCUSSION

Our results support the hypothesis that new enhancement is seen in a subset of 3T IO-MRI patients (16% in our brain tumor resection series) and typically resolves by the time of subsequent EP-MRI. In our series, all cases of new IO-MRI enhancement resolved by the time of early EP-MRI. We also observed new enhancement on EP-MRI that was not seen on IO-MRI in 1 patient, suggesting that this is very rare at 3T. Like the transient procedure-related enhancement (TPRE) on IO-MRI, this new EP-MRI enhancement decreased on subsequent imaging.

Despite the undeniable utility of IO-MRI, our results demonstrate that TPRE can potentially confound accurate assessment of residual tumor burden on 3T MRI. This phenomenon highlights one component of the difficulty of accurate IO-MRI interpretation, which is also complicated by susceptibility artifacts from craniotomy and gas, presence of intraoperative hemorrhage and packing materials, and operative margin infarction. The neuroradiologist must integrate these findings, coupled with the location and configuration of this TPRE to distinguish it from residual enhancing tumor.24 As a result, we feel that these findings further support the neuroradiologist as a key member of the treatment team, ensuring regions of transient enhancement are not mistaken for residual enhancing tumor.

Prior work has demonstrated the greatest utility of EP-MRI in evaluating residual tumor burden and delineating residual tumor from postoperative inflammatory, ischemic, and vascular enhancement.25-27 In addition, patients with low residual tumor volumes at this <72-h time point have been shown to have a significant survival benefit.10 As such, it is reassuring that we detected new TPRE in only one patient's 3T EP-MRI. These findings support the practice of performing postoperative 3T MRI in 24 to 72-h postsurgery window originally established using 1.5T MRI. In the case of new TPRE observed on EP-MRI within 72 h, follow-up imaging within 8 wk may be prudent to differentiate transient postoperative enhancement from unusually rapid tumor progression.

A previous study demonstrated new reactive enhancement in 32.6% of patients after surgery on 3T MRI; however, this study was concerned with new dural and leptomeningeal enhancement.28 We intentionally discounted dural and local leptomeningeal new enhancement, because it is known to be frequently observed after surgery and is easily distinguished from residual tumor.23 Our results are in line with a recent study, which also demonstrated the presence of TPRE in a minority of patients after brain tumor resection. Masuda et al21 demonstrated new enhancement in 36% of patients on intraoperative MRI and 54.5% of patients on EP-MRI, performed within 24 h of surgery. Our study differs in that ours includes a larger number of patients (n = 64), all IO-MRI were performed on the same high-field 3T MRI scanner, and the inclusion of patients with metastases and low-grade glial tumors. These attributes make our experience a relevant guide for typical neurosurgical practices that make use of 3T MRI to assess patients with both primary and metastatic brain tumors. In combination with our findings, these results support the utility of 3T EP-MRI performed at 24 to 72 h post-op for confirming expected evolution of early postoperative enhancement seen on 3T IO-MRI.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, this study is retrospective, with associated variance in the multiple imaging time intervals, including the time interval between preoperative to IO-MRI. It is possible that in patients with a long interval between pre- and IO-MRI, apparent new enhancement could represent residual disease new from preoperative imaging. However, the chances of this are minimized given the majority of patients had available preoperative imaging within 2 wk of surgery.

Another limitation to this study is the potential error of inaccurate assessment of new enhancement on IO-MRI and EP-MRI by the readers secondary to obscuration from either intrinsic T1 shortening around the resection cavity and/or significant residual disease around the cavity. Similarly, patients with hemorrhage and/or packing material within the surgical cavity, intrinsic T1 shortening could make it difficult to detect new enhancement in comparison to the preoperative scan. As a result of these phenomena, readers are suspected to be more likely to accurately assess for new enhancement when it is distant from sites of residual disease and hemorrhage. We sought to minimize the likelihood of this error by having readers interrogate preoperative imaging alongside IO-MRI and EP-MRI studies.

We note that the average postcontrast time delay on IO-MRI was longer than expected for what is typically utilized for contrast-enhanced MRI imaging. Interestingly, despite this finding, we observed no significant difference in contrast injection time delay between those patients for which we see TPRE vs those without TPRE. This suggests that despite this longer than expected postinjection time delay in imaging, it did not increase the likelihood of detecting new foci of enhancement on IO-MRI. Our finding that the TPRE decreased or resolved on subsequent EP-MRI is consistent with a prior study that demonstrated intraoperative MRI abnormal enhancement to be markedly reduced or absent on subsequent imaging.29 Thus, the shorter postinjection time delay on EP-MRI compared with IO-MRI in our study may contribute to the resolution of the TPRE but seems unlikely to completely explain it.

We found an association between the administration of Gadavist and the detection of TPRE on IO-MRI, compared with the administration of Magnevist. Prior research has demonstrated increased brain tumor enhancement with Gadavist compared with Magnevist. As a result, the actual incidence of TPRE on IO-MRI is potentially slightly underestimated in our study.

Furthermore, this study lacks a gold standard for assessment of new contrast enhancement on MRI. We sought to minimize this potential variability by using 3 blinded physicians with neuroradiology subspecialty training.

CONCLUSION

New TPRE occurs in a minority (roughly 16%) of patients during 3T intraoperative MRI after brain tumor resection and in our series always decreased or resolved by the time of EP-MRI performed within 72 h. We confirm that new enhancement very rarely occurs on 3T EP-MRI performed within 72 h and either decreases or resolves on subsequent imaging. In combination with recent complementary data showing frequent early postoperative enhancement on MRI performed within 24 h, our study supports the practice of imaging at 24 to 72 h post-op when using 3T MRI and suggests that 3T MRI at 24 to 72 postresection can be used to confirm expected evolution of new enhancement seen on 3T IO-MRI.

Disclosures

This work was supported by the following NIH-sponsored grants: R01LM012434-02, R01NS049251, P41-EB015898, and P41-EB015902-20. The authors have no personal, financial, or institutional interest in any of the drugs, materials, or devices described in this article.

Notes

This work was presented as an oral paper presentation at the American Society of Neuroradiology (ASNR) Annual Meeting on May 18-23, 2019, in Boston, Massachusetts.

Contributor Information

Nityanand Miskin, Department of Radiology, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Medical School, Harvard University, Boston, Massachusetts.

Prashin Unadkat, Department of Radiology, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Medical School, Harvard University, Boston, Massachusetts; Department of Neurosurgery, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Medical School, Harvard University, Boston, Massachusetts; Department of Surgery, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Medical School, Harvard University, Boston, Massachusetts.

Michael E Carlton, Department of Radiology, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Medical School, Harvard University, Boston, Massachusetts.

Alexandra J Golby, Department of Radiology, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Medical School, Harvard University, Boston, Massachusetts; Department of Neurosurgery, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Medical School, Harvard University, Boston, Massachusetts.

Geoffrey S Young, Department of Radiology, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Medical School, Harvard University, Boston, Massachusetts.

Raymond Y Huang, Department of Radiology, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Medical School, Harvard University, Boston, Massachusetts.

REFERENCES

- 1. Sanai N, Polley M-Y, McDermott MW, Parsa AT, Berger MS. An extent of resection threshold for newly diagnosed glioblastomas. JNS. 2011;115(1):3-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chaichana KL, Jusue-Torres I, Navarro-Ramirez R et al.. Establishing percent resection and residual volume thresholds affecting survival and recurrence for patients with newly diagnosed intracranial glioblastoma. Neuro-Oncol. 2014;16(1):113-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Li YM, Suki D, Hess K, Sawaya R. The influence of maximum safe resection of glioblastoma on survival in 1229 patients: can we do better than gross-total resection? JNS. 2016;124(4):977-988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schucht P, Murek M, Jilch A et al.. Early re-do surgery for glioblastoma is a feasible and safe strategy to achieve complete resection of enhancing tumor. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(11):e79846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stummer W, Pichlmeier U, Meinel T et al.. Fluorescence-guided surgery with 5-aminolevulinic acid for resection of malignant glioma: a randomised controlled multicentre phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7(5):392-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stummer W, Reulen H-J, Meinel T et al.. Extent of resection and survival in glioblastoma multiforme: identification of and adjustment for bias. Neurosurgery. 2008;62(3):564-576; discussion 564-576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yoo H, Kim YZ, Nam BH et al.. Reduced local recurrence of a single brain metastasis through microscopic total resection. JNS. 2009;110(4):730-736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Aizer AA, Bi WL, Kandola MS et al.. Extent of resection and overall survival for patients with atypical and malignant meningioma. Cancer. 2015;121(24):4376-4381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Smith JS, Chang EF, Lamborn KR et al.. Role of extent of resection in the long-term outcome of low-grade hemispheric gliomas. JCO. 2008;26(8):1338-1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Roelz R, Strohmaier D, Jabbarli R et al.. Residual tumor volume as best outcome predictor in low grade glioma - a nine-years near-randomized survey of surgery vs. biopsy. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):32286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shaw EG, Berkey B, Coons SW et al.. Recurrence following neurosurgeon-determined gross-total resection of adult supratentorial low-grade glioma: results of a prospective clinical trial. JNS. 2008;109(5):835-841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ekinci G, Akpinar IN, Baltacioğlu F et al.. Early-postoperative magnetic resonance imaging in glial tumors: prediction of tumor regrowth and recurrence. Eur J Radiol. 2003;45(2):99-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Senft C, Bink A, Franz K, Vatter H, Gasser T, Seifert V. Intraoperative MRI guidance and extent of resection in glioma surgery: a randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(11):997-1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kuhnt D, Becker A, Ganslandt O, Bauer M, Buchfelder M, Nimsky C. Correlation of the extent of tumor volume resection and patient survival in surgery of glioblastoma multiforme with high-field intraoperative MRI guidance. Neuro-Oncol. 2011;13(12):1339-1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Olubiyi OI, Ozdemir A, Incekara F et al.. Intraoperative magnetic resonance imaging in intracranial glioma resection: a single-center, retrospective blinded volumetric study. World Neurosurg. 2015;84(2):528-536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schneider JP, Trantakis C, Rubach M et al.. Intraoperative MRI to guide the resection of primary supratentorial glioblastoma multiforme–a quantitative radiological analysis. Neuroradiology. 2005;47(7):489-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Walker M, Khawar S, Shaibani A, Reddy S, Ganju A, Gupta M. Gadolinium leakage into the surgical bed mimicking residual enhancement following spinal cord surgery. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2004;100(3 Suppl Spine):291-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zaidi HA, Chowdhry SA, Wilson DA, Spetzler RF. The dilemma of early postoperative magnetic resonance imaging. Neurosurgery. 2014;74(3):E335-E340; discussion E340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Albert FK, Forsting M, Sartor K, Adams HP, Kunze S. Early postoperative magnetic resonance imaging after resection of malignant glioma: objective evaluation of residual tumor and its influence on regrowth and prognosis. Neurosurgery. 1994;34(1):45-60; discussion 60-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Henegar MM, Moran CJ, Silbergeld DL. Early postoperative magnetic resonance imaging following nonneoplastic cortical resection. J Neurosurg. 1996;84(2):174-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Masuda Y, Akutsu H, Ishikawa E et al.. Evaluation of the extent of resection and detection of ischemic lesions with intraoperative MRI in glioma surgery: is intraoperative MRI superior to early postoperative MRI? J Neurosurg. 2018:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Forsyth PA, Petrov E, Mahallati H et al.. Prospective study of postoperative magnetic resonance imaging in patients with malignant gliomas. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1997;15(5):2076-2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wilms G, Lammens M, Marchal G et al.. Prominent dural enhancement adjacent to nonmeningiomatous malignant lesions on contrast-enhanced MR images. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1991;12(4):761-764. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ginat DT, Swearingen B, Curry W, Cahill D, Madsen J, Schaefer PW. 3 Tesla intraoperative MRI for brain tumor surgery. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2014;39(6):1357-1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kumar AJ, Leeds NE, Fuller GN et al.. Malignant gliomas: MR imaging spectrum of radiation therapy- and chemotherapy-induced necrosis of the brain after treatment. Radiology. 2000;217(2):377-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ulmer S, Braga TA, Barker FG, Lev MH, Gonzalez RG, Henson JW. Clinical and radiographic features of peritumoral infarction following resection of glioblastoma. Neurology. 2006;67(9):1668-1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brandsma D, Stalpers L, Taal W, Sminia P, van den Bent MJ. Clinical features, mechanisms, and management of pseudoprogression in malignant gliomas. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(5):453-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lescher S, Schniewindt S, Jurcoane A, Senft C, Hattingen E. Time window for postoperative reactive enhancement after resection of brain tumors: less than 72 hours. FOC. 2014;37(6):E3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Knauth M, Aras N, Wirtz CR, Dörfler A, Engelhorn T, Sartor K. Surgically induced intracranial contrast enhancement: potential source of diagnostic error in intraoperative MR imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20(8):1547-1553. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]