Abstract

Background:

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) individuals face considerable health disparities, often due to a lack of LGBTQ-competent care. Such disparities and lack of access to informed care are even more staggering in rural settings. As the state medical school for the Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, and Idaho (WWAMI) region, the University of Washington School of Medicine (UWSOM) is in a unique position to train future physicians to provide healthcare that meets the needs of LGBTQ patients both regionally and nationally.

Objective:

To describe our methodology of developing a student-driven longitudinal, region-wide curriculum to train medical students to provide high-quality care to LGBTQ patients.

Methods:

A 4-year LGBTQ Health Pathway was developed and implemented as a student-led initiative at the UWSOM. First- and second-year medical students at sites across the WWAMI region are eligible to apply. Accepted Pathway students complete a diverse set of pre-clinical and clinical components: online modules, didactic courses, longitudinal community service/advocacy work, a scholarly project, and a novel clinical clerkship in LGBTQ health developed specifically for this Pathway experience. Students who complete all requirements receive a certification of Pathway completion. This is incorporated into the Medical Student Performance Evaluation as part of residency applications.

Results:

The LGBTQ Health Pathway is currently in its fourth year. A total of 43 total students have enrolled, of whom 37.3% are based in the WWAMI region outside of Seattle. Pathway students have completed a variety of scholarly projects on LGBTQ topics, and over 1000 hours of community service/advocacy. The first cohort of 8 students graduated with a certificate of Pathway completion in spring 2020.

Conclusions:

The LGBTQ Health Pathway at UWSOM is a novel education program for motivated medical students across the 5-state WWAMI region. The diverse milestones, longitudinal nature of the program, focus on rural communities, and opportunities for student leadership are all strengths and unique aspects of this program. The Pathway curriculum and methodology described here serve as a model for student involvement and leadership in medical education. This program enables medical students to enhance their training in the care of LGBTQ patients and provides a unique educational opportunity for future physicians who strive to better serve LGBTQ populations.

Keywords: LGBTQ health, diversity and inclusion, undergraduate medical education

Introduction

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) individuals make up a significant percentage (3-12%) of the United States population, and face considerable disparities with regards to health, risk behaviors, and access to competent healthcare.1 Rates of smoking, alcohol consumption, drug abuse, high-risk sexual activity, poor mental health, and suicidality are significantly higher in LGBTQ communities than in the general population.2,3 LGBTQ individuals also have higher rates of various cancers and face disparities across the cancer care continuum.3 Many of these disparities are exacerbated by a lack of access to healthcare providers who can appropriately care for LGBTQ patients.3-5 For example, men who have sex with men often fail to receive proper screening for cancers and sexually transmitted infections.3,4 Transgender patients in particular report a shortage of healthcare providers knowledgeable about transgender medicine as the largest barrier to healthcare access, and physicians themselves report a lack of training and knowledge regarding transgender medicine.6,7 While it is clear that LGBTQ patients require healthcare that is tailored to their needs, physicians with little to no training in LGBTQ healthcare are ill-prepared to provide this care.

Medical students with greater LGBTQ clinical experience provide higher quality care to LGBTQ patients than students with less experience.8 However, medical education in LGBTQ healthcare is often limited or absent, which severely restricts the number of physicians with competence in LGBTQ healthcare. One study of US and Canadian medical schools showed the median time spent on LGBTQ healthcare was only 5 hours.9 Additionally, 33% of medical schools failed to cover any LGBTQ content during clinical years and 7% of schools lacked any LGBTQ training during pre-clinical years.9 Subsequent work revealed that many physicians do not feel comfortable providing quality care to LGBTQ patients and hold biases against these populations.10 The lack of LGBTQ curricula represents a failure of medical schools to prepare future physicians to care for these populations, and an adverse learning environment for medical students who identify as LGBTQ. One-third of LGBTQ medical students remain “in the closet” while in medical school, and 40% are fearful of anti-LGBTQ discrimination from their peers.11 All physicians, regardless of specialty, interact with LGBTQ patients; therefore, training opportunities in LGBTQ healthcare is essential for improving the quality of life for both LGBTQ patients and medical students.

The University of Washington School of Medicine (UWSOM) is unique in that it serves as the state medical school for a 5-state region: Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, and Idaho (WWAMI). Medical students who train at the University of Washington often return to these states after the completion of their training to practice.12 In the state of Washington, several UW Medicine hospitals are designated as “Leaders in LGBTQ Healthcare Equality” by the Human Rights Campaign; however, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, and Idaho lack any healthcare facilities with this designation.13

To address these gaps, we sought to develop an elective, longitudinal undergraduate medical education program that enables medical students to gain more exposure to LGBTQ healthcare. This innovative LGBTQ Health Pathway at the UWSOM, a medical student-led initiative, aims to increase the number of LGBTQ-competent physicians both regionally and nationally, while fostering an inclusive and accepting learning environment for medical students.

Methods

Needs assessment

We first performed a needs assessment to determine whether medical students at UWSOM supported the development of an LGBTQ Health Pathway. In an anonymous, online survey sent to the entire medical student body, 46 out of 48 students who responded (95.8%, approximately 5% response rate) agreed that an LGBTQ Health Pathway would be an “important addition to medical education at UWSOM.” Students offered many suggestions for educational components of the Pathway that were considered in developing educational milestones. While the low response rate limits our interpretation of this study, it demonstrated student support for further development of this Pathway.

Pathway development, goals, and objectives

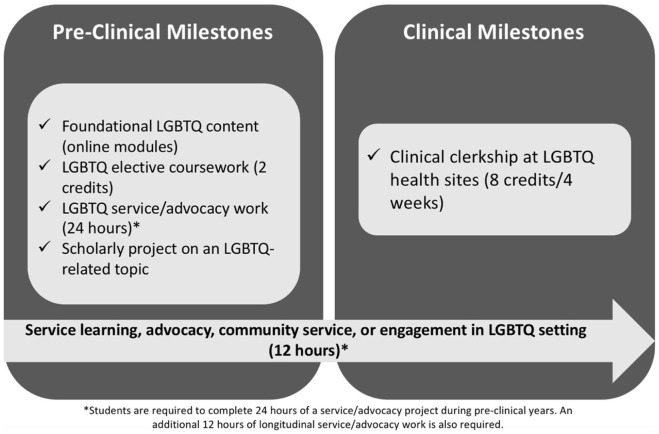

The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) highlights the importance of medical student-led initiatives for the enhancement of LGBTQ healthcare education and offers resources for the implementation of these projects.14 With this guidance, we formed an LGBTQ Health Pathway committee to develop pre-clinical and clinical milestones that address specific learning goals and objectives (Table 1). This committee was comprised of medical students, physicians with expertise in LGBTQ healthcare, community representatives from LGBTQ advocacy organizations, and staff from the Center for Health Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (CEDI) at UWSOM. A physician faculty member board-certified in family medicine with extensive experience including a practice devoted to LGBTQ health was appointed to serve as the LGBTQ Health Pathway Director. Medical students serve as committee chairs and lead Pathway initiatives (an overview of the LGBTQ Health Pathway committee is provided in Supplementary Material 1). CEDI provides partial salary support for the Pathway Director, administrative support, and additional funds for networking and mentorship events. The Pathway committee developed the curriculum over the course of several months, and existing CEDI Pathways focused on underserved populations (Latinx Health Pathway, Indian Health Pathway) served as a template in designing the LGBTQ Health Pathway curriculum. The UWSOM Curriculum Committee approved the curriculum as a pilot in 2016 and the Pathway (Figure 1) was permanently implemented 2017.

Table 1.

Goals, objectives, and milestones for the LGBTQ Health Pathway at the University of Washington School of Medicine.

| Learning goals and objectives | Pre-clinical milestones | Clinical milestones |

|---|---|---|

| 1: Develop an awareness of the health disparities that face the LGBTQ community | • 3 interactive online modules introduce

students to topics on addressing assumptions and biases,

gender identity/expression, sexuality and attraction,

communicating with LGBTQ patients, and real-world needs and

issues faced by LGBTQ communities. • 2 courses (LGBTQ Health and Health Disparities, and the Clinical Management of Transgender Patients) expose students to specific LGBTQ health and healthcare disparities. These courses also teach students the nuances of caring for LGBTQ patients. |

• During their LGBTQ-focused clinical clerkship,

students learn from physicians and patients about the

disparities of LGBTQ populations. In addition, students gain

experience directly addressing these disparities in a

clinical setting. • Under the mentorship of experienced providers of LGBTQ healthcare, students practice caring for and managing large panels of LGBTQ patients at various clinics. |

| 2: Learn to provide effective and compassionate medical care to LGBTQ patients and address their unique health concerns | ||

| 3: Develop skills to be an effective, multi-disciplinary advocate for the LGBTQ community | • Students complete 24 hours LGBTQ-focused

community service/advocacy work during their pre-clinical

years, which allows students to gain experience providing

for the LGBTQ community in a non-clinical

setting. • Pathway students engage with LGBTQ organizations as part of their service/advocacy work. In addition, LGBTQ community partners help with the development of Pathway content and connect with students during the self-reflection component of the online modules. |

• Students complete an additional 12 longitudinal service hours throughout both their pre-clinical and clinical years. This allows students to obtain long-term exposure to LGBTQ advocacy. |

| 4: Learn more about community programs that can provide support for LGBTQ individuals | ||

| 5: Gain insight into how research can help illuminate and address LGBTQ health issues | • Pathway students complete scholarly projects that focus on LGBTQ issues, with mentorship from experienced researchers and providers of LGBTQ healthcare. | • Clerkships at sites focusing on LGBTQ healthcare provide students opportunities to apply their scholarly work to clinical practice. |

| 6: Learn to deliver non-judgmental care through understanding and empathy for LGBTQ patients | • Online modules introduce students to the importance of

understanding and empathy when caring for LGBTQ

patients. • Through pre-clinical coursework, students learn from LGBTQ patient panels and patient narratives about experiences and needs of LGBTQ individuals navigating the healthcare system. |

• Students develop empathy for LGBTQ patients through

continuous interactions with LGBTQ individuals in clinical

settings. • Mentorship from experienced clinicians allows students to learn from mistakes, observe culturally competent care, and develop a deeper understanding of LGBTQ patient experiences. |

Figure 1.

Overview of the LGBTQ Health Pathway experience.

Admission to the Pathway is decided by the LGBTQ Health Pathway committee, which strives to create cohorts of students with diverse backgrounds, identities, prior exposure to LGBTQ issues, and represent WWAMI regional sites. Application materials include a statement of interest, motivation for applying, educational and career goals, specific areas of interest within LGBTQ health, and prior experience with LGBTQ populations. Medical students who complete all of the Pathway components are awarded a certificate of completion, which is listed on the students’ transcripts. Pathway participation is also highlighted in the Medical Student Performance Evaluation (MPSE, formerly known as the dean’s letter) and submitted as part of residency program applications.

Pre-clinical milestones

The pre-clinical educational experience for students in the LGBTQ Health Pathway begins with the completion of 3 online modules that focus on: “Addressing Assumptions”, “Gender, Sex, and Attraction”, and “Real World Applications.” A Seattle community partner, the Ingersoll Gender Center, was contracted to assist with module development. Modules are designed to introduce LGBTQ topics prior to formal coursework and clinical interactions. These modules also introduce students to the importance of understanding intersectional identities, a topic covered further in the elective coursework. After module completion, Pathway students participate in a 2-hour reflection seminar led by members of the LGBTQ Health Pathway committee. Students meet regularly with the Pathway Director and faculty committee members who provide mentorship and discuss personal goals and plans for completing Pathway milestones.

Pathway students are required to complete 2 elective courses offered by CEDI and taught by physician faculty with expertise in LGBTQ healthcare: “LGBTQ Health & Health Disparities” and “Clinical Management of Transgender Patients.” Descriptions of these courses are detailed in Supplementary Material 2. Both the modules and courses are available to all medical students, as well as students in the other health sciences schools at UW. In addition, Pathway students must also complete 24 hours of LGBTQ community service/advocacy.

Finally, while all students at UWSOM are required to complete a scholarly project, students in the LGBTQ Health Pathway must complete their project with a focus on LGBTQ health. A strength of the community service and scholarly project milestones is that they can be accomplished in a variety of ways, ranging from rural community interventions to global and public health research. Approval from the Pathway Director is required to ensure students engage in a suitable service experience and complete a project with sufficient educational depth and breadth. Examples and resources for completing the service learning and scholarly project milestones are provided for students on the Pathway website.15

Clinical milestones

Pathway students are required to complete a 4-week clinical clerkship at sites recognized for providing outstanding care to LGBTQ patients, under the supervision of experienced clinicians. We collaborated with the Departments of Family Medicine and Internal Medicine to develop a novel, multiple-provider elective clerkship specifically focused on LGBTQ healthcare. To develop this clerkship, several physicians in the Seattle area were identified, site visits were arranged, and a formal clerkship curriculum was assembled. Medical students rotate through several clinics on a weekly basis to obtain hands-on exposure to the care and management of a large panel of LGBTQ patients. Specific learning goals and objectives for this clerkship are outlined in Supplementary Material 3. The LGBTQ Health clerkship is available to all medical students who have completed the pre-clinical elective coursework, with Pathway students receiving priority registration. To ensure maximum flexibility for students, other select clerkships at UWSOM known for providing high-quality care to a large panel of LGBTQ patients (as approved by the LGBTQ Health Pathway Committee) can satisfy this clinical requirement.

In addition to the clerkship, Pathway students must also engage in 12 hours of longitudinal service learning/advocacy during their clinical years. UWSOM students complete clinical rotations throughout the 5-state region, and Pathway students are encouraged to complete this milestone through involvement with rural LGBTQ advocacy organizations, health outreach programs, and community activism. Thus, students have the opportunity to engage with regional communities most in need of advocacy for LGBTQ issues.

Student and program evaluations

Students in the LGBTQ Health Pathway are evaluated at several points as they progress through the Pathway curriculum. Students receive feedback from Pathway committee members during the module reflection session, as well as during annual meetings with the Pathway Director. Students are given feedback throughout the didactic courses, after which they are formally graded on a pass/fail basis and must receive a passing grade (Supplementary Material 2). The clinical clerkship serves as an important opportunity to get feedback from experienced providers over a 4-week period. Further, students receive written evaluations at the conclusion of the clerkship and must also receive a passing grade (Supplementary Material 4). Beginning with the 2020 to 2021 academic year, a survey will be administered upon Pathway admission and Pathway completion to assess the efficacy of the overall Pathway curriculum and examine students’ perspectives of their LGBTQ clinical competencies (Supplemental Material 5).

Results

The first cohort of students (n = 6) who entered the Pathway in 2016 completed a short survey following completion of pre-clinical milestones to examine their impressions of the Pathway curriculum and its impact on their medical education. All 6 students (100%) reported that the LGBTQ Health Pathway was having a positive impact on their medical education and career goals. Moreover, all 6 students (100%) felt that the education and training they were receiving from the Pathway had improved their abilities to care for LGBTQ patients.

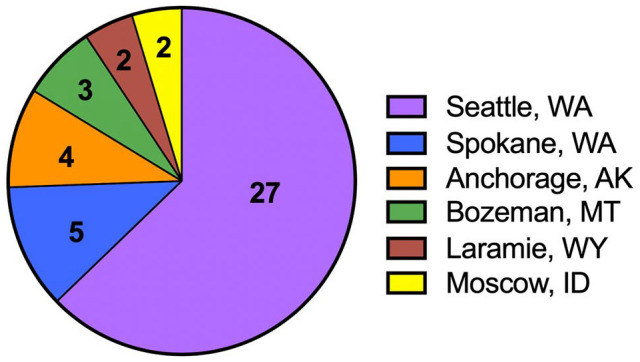

The Pathway is currently comprised of 43 students (Figure 2). For the pilot year of the Pathway (2016-2017), acceptances were capped at 6 first-year students and increased to 10 to 15 first- or second-year students in subsequent years. The Pathway committee receives approximately 10-20 applications per year, and any students who are not admitted are encouraged to re-apply the following year. Students from each UWSOM WWAMI site participate in the Pathway, and students outside of Seattle comprise 37.2% of the Pathway student body: 5 students from Spokane, WA, 4 students from Anchorage, AK, 3 students from Bozeman, MT, 2 students from Laramie, WY, and 2 students from Moscow, ID. The remaining 27 students (62.8%) are based in Seattle, WA. Additionally, 20 out of the 43 students (46.5%) had experience working with LGBTQ populations prior to entering the Pathway.

Figure 2.

WWAMI site representation within the student body of the LGBTQ Health Pathway.

All Pathway students to date have completed the 3 online modules and passed the pre-clinical didactic courses. Students have undertaken scholarly projects on diverse LGBTQ health-related topics (Table 2) and completed over 1000 total hours of community service and advocacy. In addition, 100% of students (n = 6) who completed the LGBTQ Health clerkship received a passing grade. In the UWSOM graduating class of 2020, 8 students will receive certificates of LGBTQ Health Pathway completion.

Table 2.

Selected scholarly projects completed by LGBTQ Health Pathway students.

| Scholarly project titles |

|---|

|

Improving Competence of Providers Caring for Transgender

Patients

Developing a Survey to Evaluate the Efficacy of the Advanced LGBTQ Primary Care Clerkship Strategies to Reduced Mental Health Outcomes in Rural LGBTQ+ Populations Comparative Cost Analysis of Point-of-Care versus Laboratory-Based Testing to Initiate and Monitor HIV Treatment in South Africa Emergency Department Trauma-Informed Care Examining the Medical-Legal Partnership with a pediatrician at Seattle Children’s Hospital and a lawyer with the Lavender Rights Project (LGBTQ legal services) in Seattle |

Discussion

Sexual and gender minorities face numerous health and healthcare disparities, and managing LGBTQ patients is often difficult for physicians with little or no training in LGBTQ healthcare.1-7 Exposure to LGBTQ health topics during undergraduate medical education is limited, and 4 out of the 5 states served by the University of Washington do not have any healthcare facilities designated as Leaders in Healthcare Equality.9,13 To combat these issues, we created a multi-state medical education program designed to train future physicians to care for LGBTQ patients.

The LGBTQ Health Pathway represents a medical student-led initiative from inception to implementation. Throughout the development of the Pathway, medical students worked with faculty and staff to draft curricula, develop goals and objectives, and establish acceptance criteria and milestones. New Pathway initiatives are now being led by current Pathway students. Thus, this training program not only provides education focused on LGBTQ healthcare, but also enables students to gain valuable experience in leadership, curriculum development, and administration. New students who take on leadership roles have opportunities to implement new ideas and initiatives with oversight from faculty, which further improve the Pathway experience for future cohorts. Ultimately, our Pathway serves as a model for how student involvement and leadership can create innovative opportunities for medical education.

Pathway implementation required overcoming several institutional barriers, including the need for formal approval of new curricula, time investments from faculty and staff, and continued administrative and financial support. Early in the pathway development process, student leadership arranged several meetings with faculty members on the School of Medicine Curriculum committee who served as advocates and provided guidance throughout the curriculum design and approval process. Specifically, student leadership worked with faculty to draft specific learning goals and objectives, as well as a curriculum outline, which were required by the School of Medicine prior to approval. The Pathway committee also partnered with several student affinity groups, including the Q-Med (Queers in Medicine) group, to further develop the curriculum and advocate for Pathway approval and support. Financial support for the pathway was one of the largest barriers to implementation. Student leadership met with CEDI leadership during pathway development to develop a plan for continued administrative and financial support for the pathway. Memoranda of understanding were drafted to formalize School of Medicine support for pathway faculty and staff. Currently, this support includes 10% full-time equivalent (FTE) for the Director’s salary, 20% FTE for the pathway administrator, and a $2000 per year operating budget. However, clerkship preceptors, didactic course lecturers, and student leadership represent volunteered time without compensation.

The LGBTQ Health Pathway serves the 5-state WWAMI region. This provides a unique opportunity for students from areas with less LGBTQ exposure to gain experience working with these populations. In fact, more than one-third of current Pathway students are based in the WWAMI region outside of Seattle and over half of the students had no prior experience working with LGBTQ populations. A major goal of the LGBTQ Health Pathway is to increase the number of LGBTQ-competent physicians throughout the 5-state region. Medical students in the Pathway are encouraged to participate in healthcare, advocacy, and public health initiatives related to LGBTQ issues in areas outside of Seattle throughout their Pathway experience. Indeed, the opportunity to engage in social justice, advocacy, and public health activities during medical school, particularly in rural settings, represents a key benefit of Pathway participation.

Because the Pathway is longitudinal, with training taking place throughout their medical school experience, students have a diversity of educational experiences from which to draw during their graduate medical education and future clinical practices. These experiences build on each other and reinforce previous lessons during each phase of students’ medical education. The Pathway begins with online modules and coursework that solidify students’ knowledge of LGBTQ topics prior to hands-on patient care during the LGBTQ Health clerkship. All students who enrolled in the novel LGBTQ Health elective clerkship successfully completed the rotation, signifying that Pathway students are gaining the pre-requisite knowledge and successfully applying that knowledge to the care of LGBTQ patients.

While this Pathway provides a unique opportunity for students specifically interested in LGBTQ medicine, training in LGBTQ healthcare is essential for all medical students. All of the resources described here are available to every student at UWSOM. Nonetheless, components of the Pathway are not a part of the core curriculum. As a result, many students do not gain exposure to Pathway content and experiences. Gradual incorporation of Pathway content into the general curriculum is an important goal moving forward (see Future Directions). Another limitation of the LGBTQ Health Pathway is that admission is limited by clerkship availability. The LGBTQ Health clerkship can accommodate 1 student per month, and other clerkships that satisfy Pathway requirements do not give priority registration to Pathway students, which limits admission to 10 to 15 students per year. This means that the Pathway committee is not able to admit approximately 5-10 applicants each year, who are encouraged to re-apply the following year. Thus, expanding clinical opportunities, and consequently the number of Pathway slots, is another ambition of Pathway leadership. Finally, although success and competencies of Pathway students are evaluated at several points throughout the Pathway, we have not formally assessed overall Pathway efficacy. This is in part because the first cohort of students have only recently completed the Pathway. Formal evaluation before and after Pathway completion will be performed each year for all entering and graduating students (Supplemental Material 5).

Future Directions

In the coming years, as more students move through the Pathway curriculum, it will be critical to examine students’ self-assessments (Supplementary Material 5) as well as clinical LGBTQ competencies after completion of clinical milestones. Matched self-assessments at admission and completion of the Pathway will reveal strengths and areas for improvement of the overall Pathway curriculum. Specifically, these assessments will highlight topics in need of additional coverage during the modules, coursework, and clinical clerkship. A systematic evaluation of LGBTQ clinical competencies could be accomplished by assessing Pathway students’ interactions with standardized patients in an LGBTQ-focused clinical scenario as part of the Observed Structured Clinical Exams (OSCEs). A comparison of Pathway versus non-Pathway student clinical performance would highlight areas in need of improvement and provide a measure of Pathway efficacy, specifically with regards to learning goals and objectives 1, 2, and 6 outlined in Table 1. Finally, it will be beneficial to partner with pathway faculty to develop a formal assessment of LGBTQ-focused clinical knowledge. This assessment would involve clinical vignettes and could be administered at both the beginning and end of students’ pathway experience.

It will also be necessary to find ways to incorporate material covered in Pathway courses and modules into the general medical school curriculum. As this occurs over time, we plan to continuously enhance Pathway-specific material so that both Pathway and non-Pathway students will be better prepared to care for their future LGBTQ patients. In particular, we aim to implement new online modules for Pathway students that focus on more nuanced topics such as LGBTQ legal issues and health insurance, the history of LGBTQ healthcare, and tools for activism and advocacy in rural settings. Another goal is to enhance the clinical opportunities for medical students by adding additional clerkship sites, including a gender-affirming surgical experience with providers in the Seattle area.

One of the defining features of the LGBTQ Health Pathway is the participation of medical students from across the 5-state region, who can play a vital role in improving LGBTQ care in these communities. While students from across the region have access to all Pathway resources, finding mentorship from providers of LGBTQ healthcare for students in areas outside of Seattle remains challenging. As such, it will be important to identify additional mentors in more rural areas, as well as increase student participation across the 5 states, in order to further support the practice of rural LGBTQ medicine. Through engagement with healthcare providers throughout the region, Pathway students themselves can help achieve these goals. Furthermore, while discussions with the Pathway Director serves as an important resource to prepare students who may face LGBTQ-unwelcome communities, it is nonetheless critical to continue developing training and support programs to address this issue.

Conclusion

A lack of LGBTQ-competent healthcare providers contributes heavily to the disparities faced by LGBTQ communities. In addition, the 5-state region served by the UWSOM lacks sufficient physicians and facilities that provide high-quality LGBTQ care. We seek to address these issues through a program for medical students that offers a substantial depth and breadth of training in multiple aspects of healthcare for LGBTQ patients, with the goal of increasing the number of LGBTQ-competent physicians both regionally and nationally. Through milestones that include online modules, didactic courses, community service, scholarly projects, and a novel clinical clerkship, medical students in the LGBTQ Health Pathway at UWSOM receive unique training opportunities and elective milestones that will ultimately enable them to effectively care for LGBTQ patients.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, suppl_material for A Novel Curriculum for Medical Student Training in LGBTQ Healthcare: A Regional Pathway Experience by Alec W Gibson, Theodore A Gobillot, Kevin Wang, Elizabeth Conley, Wendy Coard, Kim Matsumoto, Holly Letourneau, Shilpen Patel, Susan E Merel, Tomoko Sairenji, Mark E Whipple, Michael R Ryan, Leo S Morales and Corinne Heinen in Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Atom Lesiak and the Ingersoll Gender Center for their contributions to the online modules, Dr. Angela Primbas for her contributions to Pathway inception and development, NormaAlicia Pino for her invaluable administrative support, Ivan Henson for his contributions to the LGBTQ health clerkship, and the faculty and staff at the University of Washington School of Medicine, the Department of Family Medicine, and the Center for Health Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion for their continuing support of the Pathway.

Footnotes

Funding:The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: A.W.G. was partially supported by National Institutes of Health grant F30DA043941; T.A.G. was partially supported by National Institutes of Health grant F30AI142870.

Declaration of conflicting interests:The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: All authors contributed to the conception, design, and implementation of the Pathway curriculum. A.W.G and T.A.G. wrote the manuscript with feedback from all authors. All authors gave final approval of the submitted manuscript.

ORCID iDs: Alec W Gibson  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5709-4146

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5709-4146

Theodore A Gobillot  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4313-3204

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4313-3204

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Quinn GP, Sanchez JA, Sutton SK, et al. Cancer and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender/transsexual, and queer/questioning (LGBTQ) populations. CA Cancer J Clin 2015;65:384-400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dilley JA, Simmons KW, Boysun MJ, Pizacani BA, Stark MJ. Demonstrating the importance and feasibility of including sexual orientation in public health surveys: health disparities in the Pacific Northwest. Am J Public Health 2010;100:460-467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gibson AW, Radix AE, Maingi S, Patel S. Cancer care in lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer populations. Future Oncol 2017;13:1333-1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Johnson CV, Mimiaga MJ, Reisner SL, et al. Health care access and sexually transmitted infection screening frequency among at-risk Massachusetts men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health 2009;99:S187-S192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Clift JB, Kirby J. Health care access and perceptions of provider care among individuals in same-sex couples: findings from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS). J Homosex 2012;59:839-850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sanchez NF, Sanchez JP, Danoff A. Health care utilization, barriers to care, and hormone usage among male-to-female transgender persons in New York City. Am J Public Health 2009;99:713-719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Snelgrove JW, Jasudavisius AM, Rowe BW, Head EM, Bauer GR. “Completely out-at-sea” with “two-gender medicine”: a qualitative analysis of physician-side barriers to providing healthcare for transgender patients. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sanchez NF, Rabatin J, Sanchez JP, Hubbard S, Kalet A. Medical students’ ability to care for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered patients. Fam Med 2006;38:21-27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Obedin-Maliver J, Goldsmith ES, Stewart L, et al. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender-related content in undergraduate medical education. JAMA 2011;306:971-977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Eckstrand KL, Potter J, Bayer CR, Englander R. Giving context to the physician competency reference set: adapting to the needs of diverse populations. Acad Med 2016;91:930-935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mansh M, White W, Gee-Tong L, et al. Sexual and gender minority identity disclosure during undergraduate medical education: “in the closet” in medical school. Acad Med 2015;90:634-644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. UW Medicine. WWAMI: a five-state medical education creating national impact. https://www.uwmedicine.org/school-of-medicine/md-program/wwami. Updated 2020. Accessed June 4, 2020.

- 13. Human Rights Campaign. Healthcare equality index. https://www.hrc.org/hei. Published 2019. Accessed June 4, 2020.

- 14. American Association of Medical Colleges. Implementing curricular and institutional climate changes to improve health care for individuals who are LGBT, gender nonconforming, or born with DSD: a resource for medical educators. https://store.aamc.org/implementing-curricular-and-institutional-climate-changes-to-improve-health-care-for-individuals-who-are-lgbt-gender-nonconforming-or-born-with-dsd-a-resource-for-medical-educators.html. Published 2014. Accessed June 4, 2020.

- 15. UW Medicine. LGBTQ Health Pathway. http://cedi-web01.s.uw.edu/pathways-electives/lgbtq-health-pathway/. Published 2020. Accessed June 4, 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, suppl_material for A Novel Curriculum for Medical Student Training in LGBTQ Healthcare: A Regional Pathway Experience by Alec W Gibson, Theodore A Gobillot, Kevin Wang, Elizabeth Conley, Wendy Coard, Kim Matsumoto, Holly Letourneau, Shilpen Patel, Susan E Merel, Tomoko Sairenji, Mark E Whipple, Michael R Ryan, Leo S Morales and Corinne Heinen in Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development