Abstract

Objective

Although the rate of stillbirth has decreased globally, it remains unacceptably high in developing countries. Today, only 10 countries share the burden of more than 65% of the global rate of stillbirth and these include Ethiopia. Ethiopia ranks seventh in terms of high rate of stillbirths. Exploring the spatial distribution of stillbirth is critical to developing successful interventions and monitoring public health programmes. However, there is no study on the spatial distribution and the associated factors of stillbirth in Ethiopia. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the spatial distribution and the associated factors of stillbirth.

Methods

Secondary data analysis was conducted based on the 2016 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey data. A total weighted sample of 11 375 women were included in the analysis. The Bernoulli model was fitted using SaTScan V.9.6 to identify hotspot areas and ArcGIS V.10.6 to explore the spatial distribution of stillbirth. For associated factors, a multilevel binary logistic regression model was fitted using STATA V.14 software. Variables with a p value of less than 0.2 were considered for the multivariable multilevel analysis. In the multivariable multilevel analysis, adjusted OR (AOR) with 95% CI was reported to reveal significantly associated factors of stillbirth.

Results

The spatial analysis showed that stillbirth has significant spatial variation across the country. The SaTScan analysis identified significant primary clusters of stillbirth in the Northeast Somali region (log likelihood ratio (LLR)=13.4, p<0.001) and secondary clusters in the border area of Oromia and Amhara regions (LLR=8.8, p<0.05). In the multilevel analysis, rural residence (AOR=4.83, 95% CI 1.44 to 16.19), primary education (AOR=0.39, 95% CI 0.20 to 0.74), no antenatal care (ANC) visit (AOR=2.77, 95% CI 1.70 to 4.51), caesarean delivery (AOR=5.07, 95% CI 1.65 to 15.58), birth interval <24 months (AOR=1.95, 95% CI 1.20 to 3.10) and height <150 cm (AOR=2.73, 95% CI 1.45 to 4.97) were significantly associated with stillbirth.

Conclusion and recommendation

In Ethiopia, stillbirth had significant spatial variations across the country. Residence, maternal stature, preceding birth interval, caesarean delivery, education and ANC visit were significantly associated with stillbirth. Therefore, public health interventions that enhance maternal healthcare service utilisation and maternal education in hotspot areas of stillbirth are crucial to reducing stillbirth in Ethiopia.

Keywords: stillbirth, Ethiopia, multilevel analysis, spatial analysis

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study was done based on the weighted Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) data to ensure representativeness and to obtain reliable estimates, and therefore the study findings have the potential to inform policymakers and programmers and also aid in designing appropriate interventions at national and regional levels.

As the study was cross-sectional, it was unable to show a temporal relationship; however, multilevel modelling was employed to take into account clustering effect in order to obtain reliable estimates and SE.

The EDHS survey did not incorporate clinically confirmed data, rather it relied on mothers’ or caregivers’ verbal autopsy, and therefore there is a possibility of social desirability and recall bias.

The SaTScan detected only circular clusters, while irregularly shaped clusters were not detected.

Background

The WHO defines stillbirth as fetal death (ie, death before the complete expulsion or extraction of a product of conception from its mother) in the third trimester (≥28 completed weeks of gestation) or with birth weight ≥1000 g or length ≥35 cm.1 2 Stillbirth remains a global public health problem, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and South Asia (SA).3 Globally, an estimated 2.6 million stillbirths occur annually, 98% of which are in developing countries.4

Most of the stillbirths occur during the intrapartum period, which can be prevented by improving maternal healthcare services.5 More than half of the 2.6 million stillbirths occur during labour and delivery,6 and stillbirths are considered an indicator of poor access to and quality of obstetric care.7 According to the most recent global estimate of WHO, the average global rate of stillbirth is 18.4 per 1000 births,8 while developing countries have rates of stillbirth tenfold higher than developed countries.9 In SSA the rate of stillbirth is 28.3 per 1000 births.10

The rate of stillbirth varies across countries and remains a huge challenge to achieving the Every Newborn Action Plan target of 12 or fewer stillbirths per 1000 births by 2030.1 Even though many high-income and upper-middle-income countries have already met this target, developing countries, particularly Africa, will have to register more than double the present progress to reach this target.1 Despite the various international and national commitments to improving newborn and maternal health,11 stillbirth has been grossly under-reported and not included in policies and programmes worldwide.12 Like many countries in SSA, stillbirth is not routinely recorded and monitored in Ethiopia. Its rate has decreased more slowly than maternal and under-5 mortality and remains not included in national policies.13

The death of a fetus in utero or at birth is a devastating experience for affected mothers and families.14 It has been associated with extensive psychosocial consequences for parents and the family and has been linked to post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, depression, suicide, fear of next pregnancy and deteriorating relationship with partners.15 16 In Ethiopia, a study conducted based on the 2011 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) reported a stillbirth rate of 25.5 per 1000 births, with significant variability across regions, and researchers recommended spatial analysis to investigate spatial variability in experiencing stillbirth in the country.17 A study done in Amhara region based on the Ethiopian Mini Demographic and Health Survey in 2014 reported a stillbirth rate of 85 per 1000 births.18 Previous studies on stillbirth showed that rural residence, parity, educational status, mode of delivery, antenatal care (ANC) utilisation, place of delivery, maternal nutritional status and maternal obstetric factors were significantly associated with stillbirth.14 19–21

The rates of stillbirth have significantly varied across the country.17 22 It is highly concentrated among rural, poor and marginalised societies.12 Thus, identification of geographical areas with a high rate of stillbirth using geographical information system (GIS) and spatial scan statistical analysis (SaTScan) has become fundamental to guide targeted public health interventions. However, previous studies in Ethiopia have been focused on the prevalence and the associated factors of stillbirth18 23 24 using standard logistic regression models despite the hierarchical structure of the EDHS data. These could result in biased estimates since the data were nested within clusters and violate independent assumptions.17 The findings of these studies were insufficient and limited to capture the spatial distribution of stillbirth and its associated community-level factors. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the spatial distribution and the associated factors of stillbirth in Ethiopia using spatial and multilevel analysis.

Methods and materials

Study design, setting and period

Secondary data analysis was done based on the EDHS 2016 data. This survey was the fourth survey conducted in the country. Ethiopia is situated in the Horn of Africa, and is the 13th in the world and 2nd in Africa’s most populous country. There are nine regional states (Afar, Amhara, Benishangul-Gumuz, Gambela, Harari, Oromia, Somali, Southern Nations, Nationalities, and People’s Region (SNNPR), and Tigray) and two administrative cities (Addis Ababa and Dire-Dawa) in its territory. In Ethiopia, 84% of the population live in rural areas and more than 80% of the country’s total population live in the regional states of Amhara, Oromia and SNNPR.25 The number of hospitals in Ethiopia varies across regions in response to differences in population size.26

Sample and population

All births from women of reproductive age within 5 years before the survey in Ethiopia were the source of population for this study, whereas all births from women of reproductive age in the selected enumeration areas (EAs) within 5 years before the survey were the study population. In EDHS, a two-stage stratified cluster sampling technique was employed using the 2007 Population and Housing Census as a sampling frame. Stratification was achieved by separating each region into urban and rural areas. In total, 21 sampling strata have been created. In the first stage, 645 EAs (202 in urban areas) were chosen with probability sampling proportional to the size of the EAs, with independent selection in each sampling stratum. In the second stage, on average, 28 households were systematically selected. The detailed sampling procedure has been presented in the full EDHS 2016 report.27

Study variables

Outcome variables

The 2016 EDHS asked women to report any pregnancy loss that occurred in the last 5 years preceding the survey. The duration of pregnancy was reported for every pregnancy separately which did not result in a live birth. Pregnancy losses occurring after seven completed months of gestation were considered as stillbirth.28 The response variable for this study was the occurrence of stillbirth among mothers of childbearing age (15–49 years). The response variable for the ith mother was represented by a random variable Yi, with two possible values coded as 1 and 0. So the response variable of the ith mother Yi was measured as a dichotomous variable with possible values Yi=1 if ith mother had experienced stillbirth and Yi=0 if the mother had a live birth.

Independent variables

Consistent with the objective of the study and given the hierarchical structure of EDHS data where women were nested within the cluster/community, two levels of independent variables were considered. Level 1 contained individual sociodemographic and economic factors (age, marital status, religion, maternal education, paternal education, wealth index, maternal occupation and maternal working status), pregnancy and pregnancy-related factors (mother’s height, body mass index, ANC visit, parity, preceding birth interval, contraceptive use, place of delivery, birth order, mode of delivery, wanted pregnancy and maternal anaemia) and behavioural factors (smoking and media exposure). The community-level factors, region, residence, community women education, community poverty, community media exposure and community ANC utilisation, were considered level 2 variables. In the EDHS data, there is no variable collected at the cluster level except region and place of residence. Therefore, individual-level variables were aggregated at the cluster level to generate community-level variables, to see whether cluster-level variables had an effect on stillbirth, and were categorised as higher or lower based on national median value since these were not normally distributed. The community-level variables used in the analysis were from two sources: direct community-level variables that were used without any manipulation (residence and region) and aggregated community-level variables (community media exposure, community poverty, community ANC utilisation and community women education) created by aggregating individual-level variables at the cluster level.

Data collection procedure

The study was conducted based on the 2016 EDHS data and geographical coordinate data, which were accessed from the official database of the Demographic and Health Surveys programme (https://dhsprogram.com/) after permission was granted to an online request that explains the objective of our study. We used the EDHS 2016 birth record data set for this study. Geographical coordinate data (longitude and latitude coordinates) were taken at the cluster level/EA level. During the period of data collection, there was no conflict across the country. A total of 645 EAs were selected and the data were collected in all of the selected EAs. However, the geographical coordinate file of 21 EAs was wrongly recorded (the latitude and longitude were recorded as 0), and when we locate these EAs the point was located out of Ethiopia and therefore we dropped the 21 EAs from spatial analysis. However, for the associated factors we used all 645 EAs. With regard to spatial analysis, we used the Kriging interpolation technique to predict stillbirth in unsampled areas since it optimises the prediction level by considering the distance decline effect (inverse distance weighting) and therefore predicts the prevalence of stillbirth in unsampled areas located between the sampled areas where the measurement was taken. Extrapolation may be prone to bias because it predicts beyond the distance limit, whereas in our study interpolation was used to predict stillbirth in unsampled areas.

Data management and analysis

Data were weighted using sampling weight, primary sampling unit and strata before any statistical analysis to restore the representativeness of the survey and take into account the sampling design to obtain reliable statistical estimates. The sampling statisticians determined how many samples are needed in each region to obtain reliable estimates in EDHS; some regions were oversampled and some undersampled. To obtain statistics that are representative of Ethiopia, the distribution of women in the sample needs to be weighted (mathematically adjusted) such that it resembles the true distribution in Ethiopia, using sampling weight (v005), primary sampling unit (v021) and strata (v022). Descriptive and summary statistics were conducted using STATA V.14 software.

Spatial analysis

For the spatial analysis, ArcGIS V.10.6 software and SaTScan V.9.6 software were used. Incremental spatial autocorrelation was done to obtain the maximum peak distance where stillbirth clustering is more pronounced. It measures spatial autocorrelation for a series of distances and creates a line graph of those distances and their corresponding z-score. The maximum peak distance is the distance where maximum spatial autocorrelation occurs and this was used as a distance band for hotspot analysis. In total, 10 distance bands were identified, with a starting distance of 121 803 m, first peak at 136 586.06 m and maximum peak (clustering) observed at 166 152.17 m. The maximum peak was used as the distance band for the hotspot analysis.

Spatial autocorrelation analysis

Spatial autocorrelation (Global Moran’s I) was done to test whether or not there was significant spatial clustering of stillbirth. Moran’s I is a statistics that measures whether stillbirth patterns were dispersed, clustered or randomly distributed in the study area29 by taking the entire data set and producing a single output value which ranges from −1 to +1. Moran’s I values close to −1 indicate spatial distribution of stillbirth was dispersed, whereas Moran’s I values close to +1 indicate spatial distribution of stillbirth was clustered, and an I value of 0 means stillbirth is distributed randomly. A statistically significant Moran’s I (p<0.05) leads to rejection of the null hypothesis (stillbirth is randomly distributed) and indicates the presence of significant spatial autocorrelation/spatial dependence.

Hotspot analysis of stillbirth

Anselin Local Moran’s I is used to investigate whether the local-level cluster is positively correlated (high-high and low-low) or negatively correlated (high-low and low-high) with regard to the prevalence of stillbirth. A positive Moran’s I value indicates that a case had neighbouring cases with similar values. A negative Moran’s I value indicates that a case was surrounded by cases with dissimilar values.30 Spatial scan statistical analysis (SaTScan) using the Bernoulli model was employed to test for the presence of statistically significant spatial clusters of stillbirth using Kulldorff’s31 SaTScan V.9.6 software. The spatial scan statistics uses a circular scanning window that moves across the study area. Women who had a stillbirth were taken as cases and those who had live birth as controls to fit the Bernoulli model. The number of cases in each location had a Bernoulli distribution and the model required data for cases, controls and geographical coordinates. The default maximum spatial cluster size of <50% of the population was used as an upper limit, which allowed both small and large clusters to be detected, while clusters that contained more than the maximum limit are ignored.

For each potential cluster, likelihood ratio (LR) test statistics and p values were used to determine if the number of observed stillbirths within the potential cluster was significantly higher than expected or not. The scanning window with the maximum likelihood was the most likely performing cluster, and a p value was assigned to each cluster using Monte Carlo hypothesis testing by comparing the rank of the maximum likelihood from the real data with the maximum likelihood from the random data sets. The primary and secondary clusters were identified and assigned p values and ranked based on their LR test, based on 999 Monte Carlo replications.31 In the Bernoulli model in the SaTScan analysis, we used the Monte Carlo hypothesis testing procedure for statistical inference of the clusters detected. Under the null hypothesis, we generated a large number of data sets by randomly permuting the locations of observations. Then, we calculated the maximum values of test statistics for each data set. In this way, we obtained empirical null distributions of the proposed test statistics. The Monte Carlo-based p value for the detected cluster is the rank of the maximum value of the test statistics from the real data set among all data sets divided by the number of all data sets. Monte Carlo testing was performed to determine whether or not the identified clusters were significant.

Spatial interpolation

It is very expensive and laborious to collect reliable data in all areas of a country to know the burden of a certain event. Therefore, part of a certain area can be predicted using observed data and using a method called interpolation. The spatial interpolation technique was used to predict stillbirths in unsampled areas in the country based on sampled EA measurements. There are various deterministic and geostatistical interpolation methods. Among all of the methods, ordinary Kriging and empirical Bayesian Kriging are considered the best methods since they incorporate spatial autocorrelation and statistically optimise the weight.32 Ordinary Kriging spatial interpolation method was selected for this study to predict stillbirths in unobserved areas of Ethiopia since it had the smallest root mean square error value and residuals.

Associated factors of stillbirth

In the EDHS data, women are nested within a cluster and we expect that women within the same cluster were more similar to each other than women in the rest of the country. It violates the standard regression model assumptions, which are the independence of observations and the equal variance across cluster assumptions. This implies the need to take into account between-cluster variability by using an advanced model. Therefore, a multilevel random intercept logistic regression model was fitted to estimate the association between individual-level and community-level variables and the likelihood of experiencing stillbirth. Model comparison was done based on deviance (−2 log likelihood) since the models were nested. LR test and intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) were computed to measure the variation between clusters. The ICC quantifies the degree of heterogeneity of stillbirths between clusters (the proportion of the total observed variation in stillbirth that is attributable to between-cluster variations).33

Multilevel random intercept logistic regression was used to analyse factors associated with stillbirth at two levels to take into account the hierarchical nature of the data, at the individual and at the community level. Four models were constructed for the multilevel logistic regression analysis. The first model (a multilevel random intercept logistic regression model without covariates) was the null model without any explanatory variables, to determine the extent of cluster variations in stillbirth. The second model (a multilevel model with level 1 independent variables) was adjusted with individual-level variables. The third model (a multilevel model with level 2 variables) was adjusted for community-level variables, while the fourth model was fitted with both individual-level and community-level variables simultaneously. The final model was the best fitted model since it had the lowest deviance value.

Variables with p value ≤0.2 in the bivariable analysis for both individual-level and community-level factors were fitted in the multivariable model. Adjusted OR (AOR) with 95% CI and p<0.05 in the multivariable model were used to reveal significantly associated factors of stillbirth. Multicollinearity was checked using the variance inflation factor (VIF), which indicates that there is no multicollinearity because all variables have VIF <5 and tolerance greater than 0.1.

Patient and public involvement

There was no patient and public involvement in this study since we conducted a secondary data analysis based on already available DHS data, which were collected to provide estimates of common health and health-related indicators. For the original project, data were obtained by engaging patients and the public, which was essential since biomarker data such as anaemia, HIV testing and anthropometric measurements were collected.34

Results

Sociodemographic and economic characteristics of respondents

A total of 11 375 women who gave birth within 5 years preceding the survey were included in the analysis. Of these, 10 149 (89.2%) women were rural residents and half (49.2%) were aged 20–29 years. With regard to maternal educational status, 7606 (66.9%) had no formal education (table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of women who gave birth within 5 years before the survey in Ethiopia, 2016

| Variables | Category | Unweighted frequency (%) | Weighted frequency (%) |

| Residence | Urban | 1994 (18.0) | 1226 (10.8) |

| Rural | 9091 (82.0) | 10 149 (89.2) | |

| Region | Tigray | 1021 (9.2) | 709 (6.2) |

| Afar | 1102 (9.9) | 119 (1.0) | |

| Amhara | 1004 (9.1) | 2122 (18.7) | |

| Oromia | 2617 (23.6) | 5280 (46.4) | |

| Somali | 1623 (14.6) | 554 (4.9) | |

| Benishangul-Gumuz | 962 (8.7) | 133 (1.2) | |

| SNNPR | 1334 (12.0) | 2402 (21.1) | |

| Gambella | 789 (7.1) | 29 (0.3) | |

| Harari | 633 (5.7) | 27 (0.2) | |

| Religion | Orthodox | 3127 (28.2) | 3844 (33.8) |

| Muslim | 5710 (51.5) | 4696 (41.3) | |

| Catholic and Protestant | 2248 (20.3) | 2835 (24.9) | |

| Maternal education | No education | 7241 (65.3) | 7606 (66.9) |

| Primary education | 2708 (24.4) | 2961 (26.0) | |

| Secondary and higher education | 1136 (10.3) | 808 (7.1) | |

| Maternal age (years) | <20 | 395 (3.6) | 374 (3.3) |

| 20–29 | 5556 (50.1) | 5599 (49.2) | |

| 30–39 | 4234 (38.2) | 4381 (38.5) | |

| ≥40 | 900 (8.1) | 1021 (9.0) | |

| Husband education | No education | 5331 (51.2) | 5339 (49.6) |

| Primary education | 3260 (31.3) | 4139 (38.5) | |

| Secondary and higher education | 1817 (17.5) | 1284 (11.9) | |

| Maternal occupation status | Had occupation | 6584 (59.4) | 6352 (55.8) |

| No occupation | 4501 (40.6) | 5023 (44.2) | |

| Wealth status | Poor | 6081 (54.9) | 5360 (47.1) |

| Middle | 1512 (13.6) | 2318 (20.4) | |

| Rich | 3492 (31.5) | 3697 (32.5) |

SNNPR, Southern Nations, Nationalities, and People’s Region.

Pregnancy and maternal health service-related characteristics of respondents

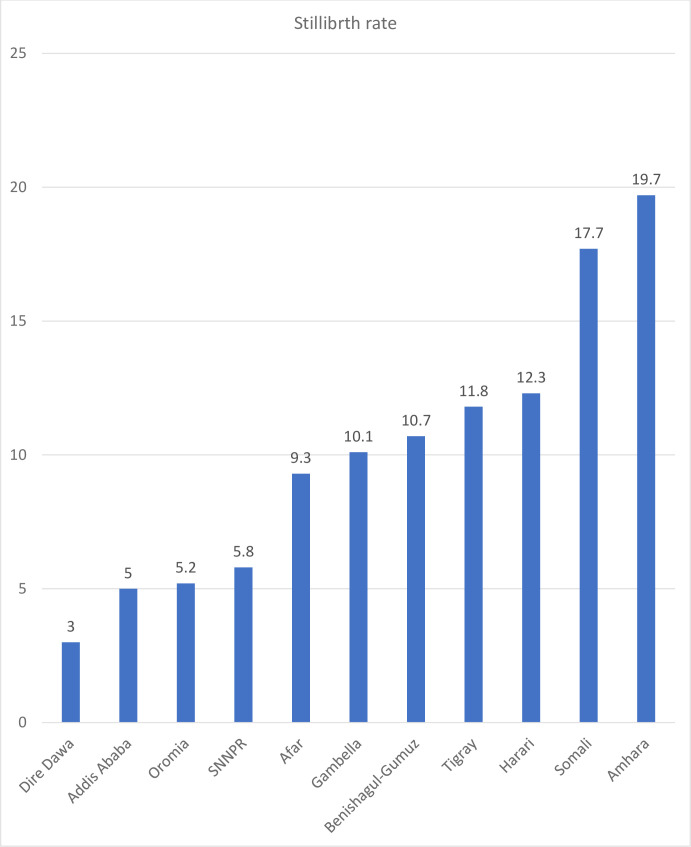

Two-thirds (65.7%) of women gave birth at home and 194 (1.7%) gave birth via caesarean section. Of the women, 2602 (22.9%) had no ANC visit during pregnancy (table 2). The overall rate of stillbirth in Ethiopia was found to be 9.2 (95% CI 7.9 to 11.1) per 1000 births. It was highest in the Amhara region and lowest in Dire-Dawa (figure 1).

Table 2.

Pregnancy and health service-related characteristics of women who gave birth within 5 years preceding the survey in Ethiopia, 2016

| Variable | Category | Unweighted frequency (%) | Weighted frequency (%) |

| Pregnancy and maternal service-related factors | |||

| Place of delivery | Home | 6737 (60.8) | 7468 (65.7) |

| Health facility | 4348 (39.2) | 3907 (34.3) | |

| Parity | Only 1 birth | 1435 (13.0) | 1419 (12.5) |

| 2–4 births | 5042 (45.5) | 5022 (44.1) | |

| ≥5 births | 4608 (41.5) | 4934 (43.4) | |

| Birth order | 1–3 | 5806 (52.4) | 5703 (50.1) |

| 4–5 | 2584 (23.3) | 2655 (23.4) | |

| ≥6 | 2695 (24.3) | 3017 (26.5) | |

| BMI | Thin | 2981 (26.9) | 2483 (21.8) |

| Normal | 7106 (64.1) | 8164 (71.8) | |

| Overweight | 998 (9.0) | 728 (6.4) | |

| Maternal height (cm) | <150 | 1018 (9.2) | 1228 (10.8) |

| ≥150 | 10 067 (90.8) | 10 147 (89.2) | |

| ANC visit | None | 2321 (20.9) | 2602 (22.9) |

| 1–3 | 1917 (17.3) | 2145 (18.9) | |

| ≥4 | 6847 (61.8) | 6628 (58.2) | |

| Preceding birth interval (months) | <24 | 2347 (21.2) | 2145 (18.9) |

| ≥24 | 8738 (78.8) | 9230 (81.1) | |

| Maternal anaemia | Not anaemic | 6696 (60.4) | 7590 (66.7) |

| Anaemic | 4389 (39.6) | 3785 (33.3) | |

| Ever use of contraceptive | Yes | 4101 (37.0) | 5238 (46.0) |

| No | 6984 (63.0) | 6137 (54.0) | |

| Mode of delivery | Vaginal delivery | 10 813 (97.5) | 11 181 (98.3) |

| Caesarean delivery | 272 (2.5) | 194 (1.7) | |

| Number of gestations | Single | 10 798 (97.4) | 11 072 (97.3) |

| Twin | 287 (2.6) | 303 (2.7) | |

| Behavioural and community-level factors | |||

| Smoking cigarettes | Yes | 10 976 (99.0) | 11 286 (99.2) |

| No | 109 (1.0) | 89 (0.8) | |

| Media exposure | Yes | 9747 (87.9) | 10 020 (88.1) |

| No | 1338 (12.1) | 1355 (11.9) | |

| Community media exposure | Lower | 5503 (49.6) | 4640 (40.8) |

| Higher | 5582 (50.4) | 6735 (59.2) | |

| Community poverty | Lower | 6909 (62.3) | 7617 (67.0) |

| Higher | 4176 (37.7) | 3758 (33.0) | |

| Community ANC utilisation | Lower | 5387 (48.6) | 6665 (58.6) |

| Higher | 5698 (51.4) | 4710 (41.4) | |

| Community women education | Lower | 6909 (62.3) | 7617 (67.0) |

| Higher | 4176 (37.7) | 3758 (33.0) | |

ANC, antenatal care; BMI, body mass index.

Figure 1.

Rates of stillbirth across regions in Ethiopia, 2016. SNNPR, Southern Nations, Nationalities, and People’s Region.

Spatial analysis

Spatial global autocorrelation

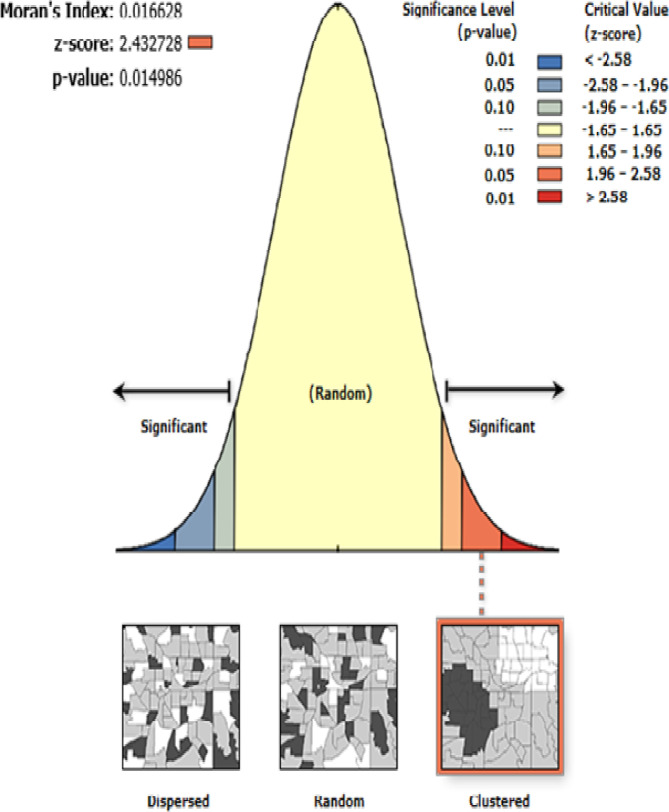

The spatial analysis revealed that the spatial distribution of stillbirth significantly varied across the country, with Global Moran’s I value of 0.017 (p<0.05). A z-score of 2.4 indicated that there is less than 1.5% likelihood that this clustered pattern could be the result of chance (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Global spatial autocorrelation of stillbirths in Ethiopia, 2016.

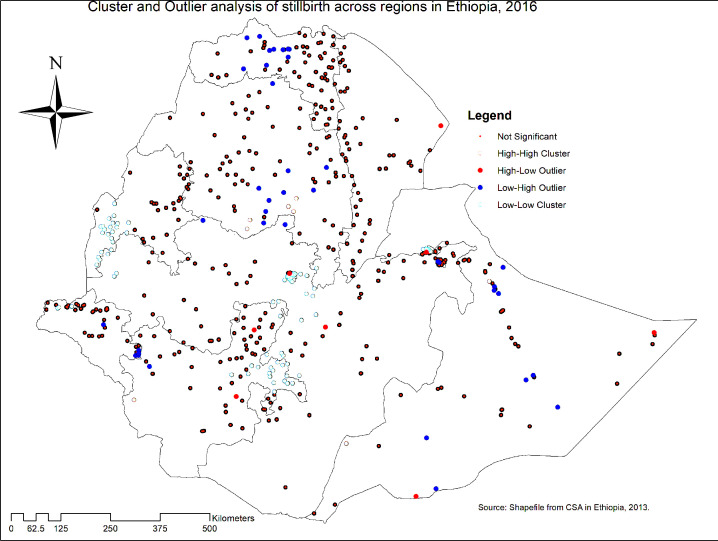

Hotspot analysis of stillbirth

In the cluster and outlier analyses, a significant cluster was detected in Tigray, Amhara, Oromia, Addis Ababa, SNNPR, Benishangul-Gumuz, Somali and Gambella regions. Hotspot areas of stillbirth were found in Southwest Somali, Southern Amhara and West SNNPR, while cold spot areas of stillbirth were found in South and West Benishangul-Gumuz, Addis Ababa, Southwest of Oromia region, West Gambella and Northeast SNNPR regions. The outliers were found in the Central and Southern parts of Amhara, North Tigray, Southeast Gambella and Somali regions (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Cluster and outlier analyses of stillbirths in Ethiopia, 2016. Source: Central Statistical Agency, Ethiopia, 2013. SNNPR, Southern Nations, Nationalities, and People’s Region.

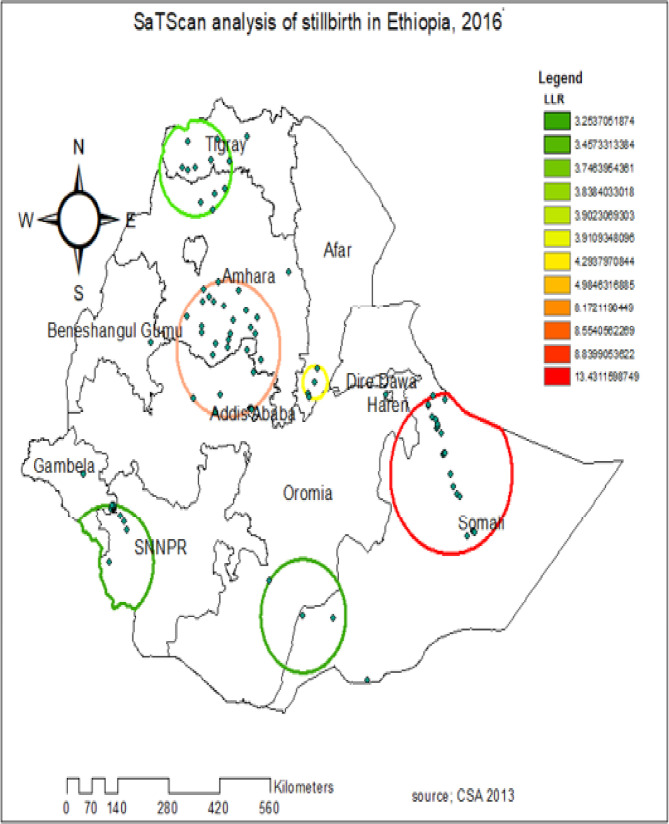

In the spatial scan statistical analysis, a total of 56 significant clusters of stillbirth were identified, of which 22 clusters were primary (most likely clusters) and 34 were secondary clusters. The primary cluster spatial window was located in the Northeast Somali region centred at 7.829198 N, 43.706264 E of geographical location, with a 166.48 km radius, a relative risk of 22.5 and a log likelihood ratio of 13.4, at p<0.001. It showed that women within the spatial window had 22.5 times higher risk of experiencing stillbirth than women outside the window. The secondary cluster scanning spatial window was located in the border area of the South Amhara region and the North Oromia region and Southern Afar region (table 3 and figure 4). The red circular ring indicates that the most statistically significant spatial window contains the primary cluster of stillbirths. Women within the circular window had a higher likelihood of experiencing stillbirth than women outside the spatial window (figure 4).

Table 3.

SaTScan analysis results of stillbirth in Ethiopia, 2016

| Cluster | Enumeration area (cluster) identified | Coordinate/radius | Population | Case | RR | LLR | P value |

| 1 | 497, 95, 198, 521, 588, 553, 458, 171, 214, 251, 573, 239, 116, 22, 543, 490, 492, 92, 568, 33, 277, 527 | 7.829198 N, 43.706264 E/166.48 km | 532 | 17 | 22.5 | 13.4 | 0.00069 |

| 2 | 350, 229, 482, 531, 218, 510, 206, 10, 474, 267, 375, 423, 120, 176, 572, 517, 460, 24, 403, 429, 38, 3, 485, 456, 274, 167, 463, 112, 399, 532 | 10.195460 N, 38.150574 E/142.05 km | 384 | 14 | 3.6 | 8.84 | 0.04 |

| 3 | 564, 39, 230, 51 | 9.555410 N, 40.326165 E/34.04 km | 50 | 4 | 8.83 | 8.55 | 0.05 |

LLR, log likelihood ratio; RR, relative risk.

Figure 4.

Spatial scan statistical analysis of hotspot areas of stillbirth in Ethiopia, 2016. Source: Central Statistical Agency, Ethiopia, 2013. LLR, log likelihood ratio; SNNPR, Southern Nations, Nationalities, and People’s Region.

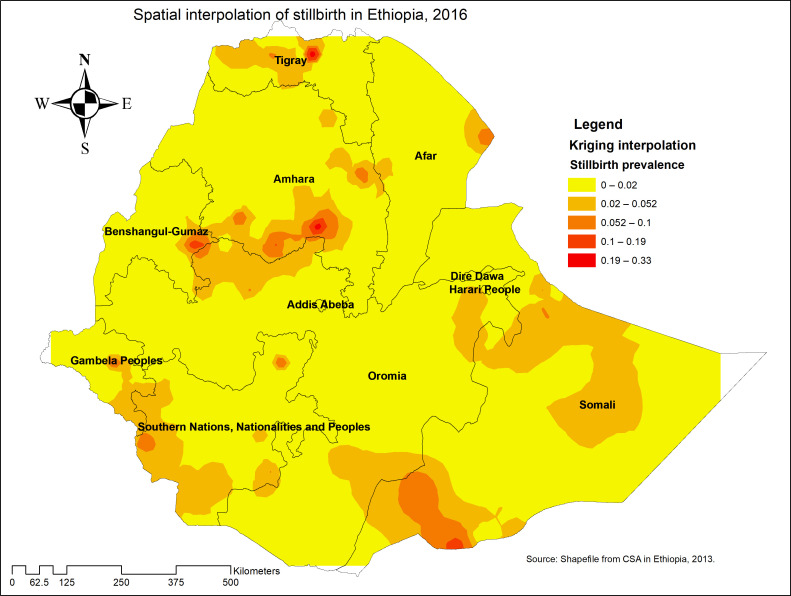

Interpolation of stillbirth

Northwest Tigray, Northern and Northwest Oromia, East and South Amhara, East Benishangul-Gumuz, East Gambella, Harari, and Northwest SNNPR were predicted as the riskiest areas for stillbirth compared with other regions, whereas the predicted low-risk areas for stillbirth were identified in Oromia, Afar and Gambella regions (figure 5).

Figure 5.

Kriging interpolation of stillbirth in Ethiopia, 2016. Source: Central Statistical Agency, Ethiopia, 2013. SNNPR, Southern Nations, Nationalities, and People’s Region.

Factors associated with stillbirth

ICC and LR tests were checked, and the multilevel model was the best fitted model for the data. Therefore, the two-level multilevel logistic regression model was used to obtain an unbiased SE and make a valid inference. Deviance was used for model comparison and the final model was the best fitted model with the lowest deviance value (table 4).

Table 4.

Multivariable multilevel logistic regression analysis results of both individual-level and community-level factors associated with stillbirth in Ethiopia, EDHS 2016

| Individual-level and community-level characteristics | Null model | Model II AOR (95% CI) |

Model III AOR (95% CI) |

Model IV AOR (95% CI) |

| Residence | ||||

| Urban | 1 | 1 | ||

| Rural | 3.75 (1.33 to 10.56) | 4.83 (1.44 to 16.19) | ||

| Region | ||||

| Amhara | 1 | 1 | ||

| Tigray | 0.54 (0.18 to 1.63) | 0.63 (0.19 to 2.17) | ||

| Afar | 0.28 (0.08 to 0.94) | 0.24 (0.05 to 1.06) | ||

| Oromia | 0.20 (0.07 to 0.55) | 0.25 (0.07 to 0.83) | ||

| Somali | 0.84 (0.32 to 2.21) | 0.98 (0.27 to 3.56) | ||

| Benishangul-Gumuz | 0.25 (0.07 to 0.92) | 0.37 (0.09 to 1.53) | ||

| SNNPR | 0.21 (0.06 to 0.69) | 0.56 (0.14 to 2.18) | ||

| Gambella | 0.26 (0.06 to 1.07) | 1.02 (0.20 to 5.22) | ||

| Harari | 0.71 (0.19 to 2.63) | 0.77 (0.16 to 3.72) | ||

| Religion | ||||

| Orthodox | 1 | 1 | ||

| Muslim | 0.59 (0.31 to 1.12) | 0.75 (0.32 to 1.77) | ||

| Protestant/Catholic | 0.12 (0.04 to 0.35) | 0.11 (0.03 to 0.37)* | ||

| Wealth status | ||||

| Poor | 1.12 (0.60 to 2.11) | 0.87 (0.45 to 1.69) | ||

| Middle | 1.58 (0.78 to 3.19) | 1.21 (0.60 to 2.47) | ||

| Rich | 1 | 1 | ||

| Women’s education | ||||

| No education | 1 | 1 | ||

| Primary education | 0.39 (0.21 to 0.75) | 0.39 (0.20 to 0.74)* | ||

| Secondary and higher education | 0.49 (0.18 to 1.33) | 0.63 (0.23 to 1.71) | ||

| Birth order | ||||

| 1–3 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 4–5 | 0.49 (0.24 to 1.03) | 0.50 (0.24 to 1.03) | ||

| 6 and above | 0.66 (0.25 to 1.75) | 0.66 (0.25 to 1.73) | ||

| Parity | ||||

| Only 1 birth | 1 | 1 | ||

| 2–4 births | 0.68 (0.37 to 1.28) | 0.65 (0.35 to 1.22) | ||

| ≥5 births | 0.45 (0.16 to 1.28) | 0.42 (0.15 to 1.20) | ||

| ANC visit | ||||

| No ANC visit | 2.85 (1.76 to 4.62) | 2.77 (1.70 to 4.51)* | ||

| 1–3 visits | 1.22 (0.68 to 2.19) | 1.11 (0.62 to 2.00) | ||

| 4 and above visits | 1 | 1 | ||

| Media exposure | ||||

| Yes | 1 | 1 | ||

| No | 2.11 (0.85 to 5.24) | 1.63 (0.66 to 4.04) | ||

| Maternal height | ||||

| <150 cm | 2.66 (1.47 to 4.79) | 2.73 (1.50 to 4.97)* | ||

| ≥150 cm | 1 | 1 | ||

| Contraceptive use | ||||

| Yes | 0.74 (0.43 to 1.26) | 0.72 (0.41 to 1.24) | ||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| Preceding birth interval | ||||

| <24 months | 1.92 (1.19 to 3.07) | 1.93 (1.20 to 3.10)* | ||

| ≥24 months | 1 | 1 | ||

| Mode of delivery | ||||

| Vaginal delivery | 1 | 1 | ||

| Caesarean delivery | 4.00 (1.35 to 11.85) | 5.07 (1.65 to 15.58)* | ||

| Community media exposure | ||||

| Lower community exposure | 1 | 1 | ||

| Higher community exposure | 0.96 (0.51 to 1.80) | 1.02 (0.51 to 2.04) | ||

| Community women’s education | ||||

| Lower community education | 1 | 1 | ||

| Higher community education | 1.28 (0.61 to 2.7) | 1.88 (0.80 to 4.42) | ||

| Constant | 0.003 (0.002 to 0.005) | 0.003 (0.001 to 0.01) | 0.002 (0.0005 to 0.009) | 0.001 (0.0002 to 0.01) |

| Model comparison and random effects | ||||

| ICC | 0.47 (0.35 to 0.59) | |||

| Log likelihood | −599.02 | −551.2 | −584.36 | −540.50 |

| Deviance | 1198.04 | 1102.2 | 1168.72 | 1081 |

*p<0.05.

ANC, antenatal care; AOR, adjusted OR; EDHS, Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey; ICC, intraclass correlation; SNNPR, Southern Nations, Nationalities, and People’s Region.

The ICC value was 47% in the null model; it showed that 47% of the total variability in stillbirths was attributable to between-cluster/EA variability, with the remaining 53% attributable to individual differences (table 4).

In the multivariable multilevel logistic regression model, residence, region, religion, preceding birth interval, caesarean delivery, maternal height, ANC visit and maternal education were significantly associated with stillbirth. At the community level (level 2), two variables were significantly associated with stillbirth. The odds of experiencing stillbirth among women residing in rural areas were 4.83 times (AOR=4.83, 95% CI 1.44 to 16.19) higher than women residing in urban areas. The odds of experiencing stillbirth among women in Tigray, Afar, Somali, SNNPR, Benishangul-Gumuz, Gambella and Harari regions were not significantly different from that of experiencing stillbirth in the Amhara region. The odds of experiencing stillbirth among women who live in the Oromia region decreased by 75% (AOR=0.25, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.83) compared with women in the Amhara region.

At the individual level, six variables were significantly associated with stillbirth. Women who were Protestant and Catholic religious followers had 89% (AOR=0.11, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.37) decreased odds of experiencing stillbirth than Orthodox Christian religious followers. Women’s educational level was significantly associated with stillbirth. Although women who attained secondary education and higher had no significant difference in experiencing stillbirth, the odds of experiencing stillbirth among women who attained primary education decreased by 61% (AOR=0.39, 95% CI 0.20 to 0.74) compared with women who did not have formal education. Also, women who had no ANC visits during pregnancy had 2.77 times (AOR=2.77, 95% CI 1.70 to 4.51) higher odds of experiencing stillbirth than women who had four and above ANC visits during pregnancy. Women who gave birth via caesarean delivery had 5.07 times (AOR=5.07, 95% CI 1.65 to 15.58) higher odds of experiencing stillbirth than women who gave birth through vaginal delivery.

The preceding birth interval was a significant predictor of stillbirth. Women with preceding birth interval less than 24 months had 1.93 times (AOR=1.93, 95% CI 1.20 to 3.10) higher odds of experiencing stillbirth compared with women with preceding birth interval 24 months and above. Also, mothers whose height was less than 150 cm had 2.73 times (AOR=2.73, 95% CI 1.50 to 4.97) higher odds of experiencing stillbirth compared with mothers whose height was greater than or equal to 150 cm (table 4).

Discussion

The rate of stillbirth in Ethiopia was 9.2 per 1000 births, with marked spatial heterogeneity. The spatial distribution of stillbirth significantly varied across the country. The SaTScan analysis detected a total of three statistically significant spatial windows with high stillbirth rates. The significant hotspot areas of stillbirth were identified in the Northeast Somali, South Afar, South Amhara and North Oromia regions. The possible explanation for this could be because these areas are more of a pastoralist area, where people do not have permanent residence and therefore health facilities are not accessible and available compared with agrarian people and those from cities. Besides, these areas are more rural and therefore had poor network of health facilities. This could also be attributed to the disparity in the distribution of maternal health service and the inaccessibility of infrastructure in the border areas of regions.35 Meanwhile, the cold spot areas of stillbirth were found in South and West Benishangul-Gumuz, Addis Ababa, Southwest of Oromia region, West Gambella and Northeast SNNPR. This could be due to these areas having relatively better availability and accessibility to health services (Addis Ababa, Dire-Dawa),36 and therefore women are more likely to use ANC and institutional delivery services, which could contribute to a decrement in antepartum and intrapartum stillbirths. The results provide insights that public health planners and programmers can use in designing effective public health interventions for hotspot areas of stillbirth identified in the study.

In the multilevel analysis, different individual and community factors were significantly associated with stillbirth. Among the community-level variables, it was found that the odds of stillbirth among women residing in the Oromia region were lower than in the Amhara region. This might be due to the availability and accessibility of maternal health facilities since the Oromia region is relatively around Addis Ababa and Dire-Dawa, where health facilities are accessible compared with other regions. Moreover, there is high turnover of health professionals in the Amhara region, particularly physicians, where they do not stay in their districts and choose to work in the capital city (Addis Ababa). These may lead to a high intrapartum stillbirth rate in the region due to the lack of trained health professionals.37 The study has shown that the odds of stillbirth were higher among women who lived in rural areas, and this was consistent with findings from previous studies in South Africa,38 African Great lake Regions,12 Nigeria,19 Northern Ghana14 and Ethiopia.17 This could be attributed to the disparity in mothers’ healthcare-seeking behaviour and in the availability and accessibility of health facilities. Women in urban areas relatively had improved health-seeking behaviour than rural residents.35 Moreover, urban residents have better awareness of maternal health services, while in rural areas health facilities may not be easily reachable and thus could result in poor pregnancy outcomes during emergency cases.39

Among the individual-level factors, being Catholic and Protestant religious followers was significantly associated with lower odds of stillbirth compared with being Orthodox religious followers. This might be related to the misperception of religious followers towards maternal healthcare service utilisation, as religion shapes their reproductive health decision making and practices and thereby governs women’s desire to use maternal health services.40 It could also be related to women’s feeding practices. Orthodox religious followers commonly do not eat animal products during pregnancy especially during the period of fasting, which could result in poor fetal outcome.41 Animal products are the main source of micronutrients and macronutrients such as folate and iron. Moreover, Orthodox religious followers consider women who give birth at home are blessed and using contraceptives is a sin. Also, women do not expose their body to health professionals during delivery. These are possible reasons that need further qualitative study.

This study identified lower odds of stillbirth among women who attained primary education compared with women who had no formal education. This finding is in line with previous studies in Kenya42 and Nigeria.19 It might be attributed to the reality that education can improve healthcare-seeking behaviour, such as timely decision to seek healthcare during pregnancy, providing better care for their health and their fetus, awareness of the danger signs of pregnancy and maternal health service utilisation.43

The odds of stillbirth were higher among women of short stature. A similar finding was reported in Pakistan.21 This might be because women of short stature are prone to adverse pregnancy outcomes such as cephalopelvic disproportion, contracted pelvis, intrauterine growth restriction, intrauterine fetal death and birth injury. Short stature reflects long-standing malnutrition or childhood infection that starts in utero or during early childhood; these women may end up with poor pregnancy outcome unless they are screened to be at risk during ANC follow-up.44

Having no ANC visit had a significant association with increased stillbirth, and this was consistent with previous findings in low-income to middle-income countries,45 Ghana46 and Kenya.42 ANC follow-up could help pregnant women seek early treatment for possible pregnancy-associated complications and undergo early screening for underlying medical conditions, which could improve birth outcomes.46 47 On the other hand, women who did not have longer ANC follow-up may not benefit from basic ANC packages.

Consistent with studies done in Nigeria19 and Gambia,48 caesarean deliveries in this study showed higher odds of stillbirth when compared with normal vaginal delivery. This might be because in developing countries, including Ethiopia, maternal health services are not available and reachable, particularly caesarean section which is done in tertiary hospitals. Caesarean section is done to save the life of newborns from high-risk pregnancies. In Ethiopia, more than 84% of the population are from rural areas, where tertiary hospitals are not accessible due to transportation problems. Caesarean sections not done in a timely manner due to transportation problems could result in fetal death. High-risk deliveries such as birth asphyxia, malpresentation, fetal stress and antepartum haemorrhage (APH) that require caesarean delivery are referred from health centres and health posts, and women may not arrive at hospitals for caesarean section in a timely manner, which could increase the risk of stillbirth.49 50 Overall, in Ethiopia, since majority of pregnant women are from rural areas, women undergo caesarean section too late since most are referred from distant health facilities.

Caesarean section delivery when performed timely is primarily done to save the life of the baby as well as the mother. However, in Ethiopia, more than 84% of the population are rural residents and healthcare facilities are not easily accessible and available. Only health posts and health centres are relatively accessible and women are too far to avail of services from hospitals where caesarean section is offered. In real scenario, in developing countries including Ethiopia, majority of deliveries occur at health centres and at home, and for complicated pregnancies such as birth asphyxia, fetal distress and APH women are referred to hospitals; however, hospitals are not easily reachable and transportation is not easily accessible. Therefore, even if women arrive at the hospital and caesarean section performed, there remains the possibility of newborns dying since caesarean section was performed too late due to delay in decision making or in transportation.

In this study, having a short interpregnancy interval was associated with higher odds of stillbirth. This was consistent with findings from studies done in SSA,51 Bangladesh52 and Amhara region.18 This could be because women with short preceding birth intervals are less able to provide nourishment for the fetus since their body had less time to recuperate from the previous pregnancy and the uterus had less time to recover. Furthermore, lactation will deplete maternal nutrition, which could result in poor pregnancy outcomes.52

The strength of this study was the use of weighted data to ensure representativeness at the national and regional level. Therefore, it can be generalised to all women who gave birth in Ethiopia during the study period. Moreover, the use of GIS and SaTScan statistical tests helped to detect similar and statistically significant hotspot areas of stillbirth and will help to design effective public health programmes. However, the SaTScan only detected circular clusters, while irregularly shaped clusters were not detected. Furthermore, the EDHS survey did not incorporate clinically confirmed data, rather it relied on mothers’ or caregivers’ verbal autopsy, and therefore there is a possibility of social desirability and recall bias.27

The findings of this study have valuable policy implications for health programme design and interventions. High-risk areas for stillbirth can be easily identified to make effective local interventions. In general, these findings are of supreme importance for the minister of health, regional health bureaus and non-governmental organisations when designing intervention programmes to reduce stillbirth in hotspot areas identified by the study. To reduce the overall rate of stillbirth in Ethiopia, Somali, Afar, Amhara and Oromia regions, developing local intervention strategies, such as improving accessibility and availability of maternal health facilities, should be emphasised in these identified SaTScan clusters.

Conclusions

In Ethiopia, stillbirth had spatial variations across the country. Statistically significant hotspot areas of stillbirth were found in the Central and Southern parts of Amhara, West SNNPR, South and North Tigray, and Southwest Somali region, whereas cold spot areas were found in Addis Ababa, Central Oromia and East SNNPR. Short preceding birth interval, short maternal stature, ANC visit, rural residence, region, religion, maternal education and caesarean delivery were significant predictors of stillbirth. Therefore, public health programmes that enhance maternal healthcare service utilisation and maternal education should target the hotspot areas of stillbirth to reduce its incidence in the country.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Measure DHS programme for providing the data set.

Footnotes

Contributors: Conceptualisation: GAT. Data curation: GAT. Funding acquisition: GAT. Investigation: GAT, LDG, SGN. Methodology: GAT, LDG, SGN. Project administration: GAT, LDG, SGN. Resources: GAT, LDG, SGN. Software: GAT, LDG, SGN. Supervision: GAT, LDG, SGN. Validation: GAT, LDG, SGN. Visualisation: GAT, LDG, SGN. Writing: GAT. Review and editing: GAT, LDG, SGN.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Map disclaimer: The depiction of boundaries on the map(s) in this article does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ (or any member of its group) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. The map(s) are provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Institute of Public Health, CMHS and the University of Gondar. Permission for data access was obtained from major demographic and health survey through an online request from http://www.dhsprogram.com. The data used for this study were publicly available with no personal identifier.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available in a public, open access repository. Data are available online and can be accessed at www.measuredhs.com.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Every newborn: an action plan to end preventable deaths, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith GCS, Fretts RC. Stillbirth. Lancet 2007;370:1715–25. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61723-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lawn JE, Gravett MG, Nunes TM, et al. . Global report on preterm birth and stillbirth (1 of 7): definitions, description of the burden and opportunities to improve data. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2010;10(Suppl 1):S1. 10.1186/1471-2393-10-S1-S1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lawn JE, Blencowe H, Waiswa P, et al. . Stillbirths: rates, risk factors, and acceleration towards 2030. Lancet 2016;387:587–603. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00837-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawn JE, Blencowe H, Pattinson R, et al. . Stillbirths: where? When? Why? How to make the data count? Lancet 2011;377:1448–63. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62187-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Temmerman M, Lawn JE. Stillbirths count, but it is now time to count them all. Lancet 2018;392:1602–4. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32342-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Admasu K, Haile-Mariam A, Bailey P. Indicators for availability, utilization, and quality of emergency obstetric care in Ethiopia, 2008. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2011;115:101–5. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blencowe H, Cousens S, Jassir FB, et al. . National, regional, and worldwide estimates of stillbirth rates in 2015, with trends from 2000: a systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2016;4:e98–108. 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00275-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saleem S, Tikmani SS, McClure EM, et al. . Trends and determinants of stillbirth in developing countries: results from the global network's population-based birth registry. Reprod Health 2018;15:100. 10.1186/s12978-018-0526-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McClure EM, Pasha O, Goudar SS, et al. . Epidemiology of stillbirth in low-middle income countries: a global network study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2011;90:1379–85. 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01275.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bamford L. Maternal, newborn and child health: service delivery. South African Health Review 2012;2012:49–66. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akombi BJ, Ghimire PR, Agho KE, et al. . Stillbirth in the African great lakes region: a pooled analysis of demographic and health surveys. PLoS One 2018;13:e0202603. 10.1371/journal.pone.0202603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.You D, Hug L, Ejdemyr S, et al. . Global, regional, and national levels and trends in under-5 mortality between 1990 and 2015, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis by the UN Inter-agency group for child mortality estimation. Lancet 2015;386:2275–86. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00120-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Badimsuguru AB, Nyarko KM, Afari EA, et al. . Determinants of stillbirths in Northern Ghana: a case control study. Pan Afr Med J 2016;25:18. 10.11604/pamj.supp.2016.25.1.6168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ogwulu CB, Jackson LJ, Heazell AEP, et al. . Exploring the intangible economic costs of stillbirth. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015;15:188. 10.1186/s12884-015-0617-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meaney S, Everard CM, Gallagher S, et al. . Parents' concerns about future pregnancy after stillbirth: a qualitative study. Health Expect 2017;20:555–62. 10.1111/hex.12480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berhie KA, Gebresilassie HG. Logistic regression analysis on the determinants of stillbirth in Ethiopia. Matern Health Neonatol Perinatol 2016;2:10. 10.1186/s40748-016-0038-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lakew D, Tesfaye D, Mekonnen H. Determinants of stillbirth among women deliveries at Amhara region, Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017;17:375. 10.1186/s12884-017-1573-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dahiru T, Aliyu AA. Stillbirth in Nigeria: rates and risk factors based on 2013 Nigeria DHS. OAlib 2016;3:1–12. 10.4236/oalib.1102747 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ali AAA, Adam I. Anaemia and stillbirth in Kassala Hospital, eastern Sudan. J Trop Pediatr 2011;57:62–4. 10.1093/tropej/fmq029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Badshah S, Mason L, Lisboa PJ. Risk factors associated with stillbirths in Public-Hospitals in Peshawar, Pakistan. J Human Soc Sci 2011;19:15. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berhan Y, Berhan A. Perinatal mortality trends in Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci 2014;24(Suppl):29–40. 10.4314/ejhs.v24i0.4S [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Welegebriel TK, Dadi TL, Mihrete KM. Determinants of stillbirth in Bonga general and Mizan Tepi university teaching hospitals southwestern Ethiopia, 2016: a case-control study. BMC Res Notes 2017;10:713. 10.1186/s13104-017-3058-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tilahun D, Assefa T. Incidence and determinants of stillbirth among women who gave birth in Jimma university specialized Hospital, Ethiopia. Pan Afr Med J 2017;28:299. 10.11604/pamj.2017.28.299.1269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Central Statistical Agency(CSA) and ICF Ethiopian demographic and health survey. Addis Abeba: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: CSA and ICF, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adugna A. Health institutions and services. Addis Abeba, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 27.CSA and ICF Ethiopia demographic and health survey 2016. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Rockville, maryland, USA: CSA and ICF, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldenberg RL, McClure EM, Bhutta ZA, et al. . Stillbirths: the vision for 2020. Lancet 2011;377:1798–805. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62235-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Waldhör T. The spatial autocorrelation coefficient Moran's I under heteroscedasticity. Stat Med 1996;15:887–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsai P-J, Lin M-L, Chu C-M, et al. . Spatial autocorrelation analysis of health care hotspots in Taiwan in 2006. BMC Public Health 2009;9:464. 10.1186/1471-2458-9-464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kulldorff M. SaTScanTM user guide. Boston, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bhunia GS, Shit PK, Maiti R. Comparison of GIS-based interpolation methods for spatial distribution of soil organic carbon (SOC). J Saudi Soc Agricult Sci 2018;17:114–26. 10.1016/j.jssas.2016.02.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rodríguez G, Elo I. Intra-class correlation in random-effects models for binary data. Stata J 2003;3:32–46. 10.1177/1536867X0300300102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.CSA and ICF Ethiopia demographic and health survey 2016. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: CSA and ICF, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adugna A. Health instituition and services in Ethiopia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Asefa A, Bekele D. Status of respectful and non-abusive care during facility-based childbirth in a hospital and health centers in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Reprod Health 2015;12:33. 10.1186/s12978-015-0024-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Assefa T, Haile Mariam D, Mekonnen W, et al. . Physician distribution and attrition in the public health sector of Ethiopia. Risk Manag Healthc Policy 2016;9:285–95. 10.2147/RMHP.S117943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nfii FN. Levels, trends and household determinants of stillbirths and miscarriages in South Africa (2010-2014), 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Babalola S, Fatusi A. Determinants of use of maternal health services in Nigeria--looking beyond individual and household factors. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2009;9:43. 10.1186/1471-2393-9-43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tarekegn SM, Lieberman LS, Giedraitis V. Determinants of maternal health service utilization in Ethiopia: analysis of the 2011 Ethiopian demographic and health survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014;14:161. 10.1186/1471-2393-14-161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dugan B. Religion and food service. Cornell hotel and restaurant administration Quarterly 1994;35:80–5. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cheptum JJ, Oyore JP, Okello Agina BM. Poor pregnancy outcomes in public health facilities in Kenya. Afr J Midwifery Womens Health 2012;6:183–8. 10.12968/ajmw.2012.6.4.183 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ahmed S, Creanga AA, Gillespie DG, et al. . Economic status, education and empowerment: implications for maternal health service utilization in developing countries. PLoS One 2010;5:e11190. 10.1371/journal.pone.0011190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liselele HB, Boulvain M, Tshibangu KC, et al. . Maternal height and external pelvimetry to predict cephalopelvic disproportion in nulliparous African women: a cohort study. BJOG 2000;107:947–52. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb10394.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McClure EM, Saleem S, Goudar SS, et al. . Stillbirth rates in low-middle income countries 2010 - 2013: a population-based, multi-country study from the Global Network. Reprod Health 2015;12(Suppl 2):S7. 10.1186/1742-4755-12-S2-S7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Afulani PA. Determinants of stillbirths in Ghana: does quality of antenatal care matter? BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016;16:132. 10.1186/s12884-016-0925-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bhutta ZA, Darmstadt GL, Haws RA, et al. . Delivering interventions to reduce the global burden of stillbirths: improving service supply and community demand. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2009;9(Suppl 1):S7. 10.1186/1471-2393-9-S1-S7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jammeh A, Vangen S, Sundby J. Stillbirths in rural hospitals in the Gambia: a cross-sectional retrospective study. Obstet Gynecol Int 2010;2010:186867. 10.1155/2010/186867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tita ATN, Landon MB, Spong CY, et al. . Timing of elective repeat cesarean delivery at term and neonatal outcomes. N Engl J Med 2009;360:111–20. 10.1056/NEJMoa0803267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith GCS, Pell JP, Dobbie R. Caesarean section and risk of unexplained stillbirth in subsequent pregnancy. Lancet 2003;362:1779–84. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14896-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tolefac PN, Tamambang RF, Yeika E, et al. . Ten years analysis of stillbirth in a tertiary hospital in sub-Sahara Africa: a case control study. BMC Res Notes 2017;10:447. 10.1186/s13104-017-2787-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.DaVanzo J, Hale L, Razzaque A, et al. . Effects of interpregnancy interval and outcome of the preceding pregnancy on pregnancy outcomes in Matlab, Bangladesh. BJOG 2007;114:1079–87. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01338.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.