Abstract

Background

The Dupuytren disease is a benign fibroproliferative disorder that leads to the formation of the collagen knots and fibres in the palmar fascia. The previous studies reveal different levels of Dupuytren’s prevalence worldwide; hence, this study uses meta-analysis to approximate the prevalence of Dupuytren globally.

Methods

In this study, systematic review and meta-analysis have been conducted on the previous studies focused on the prevalence of the Dupuytren disease. The search keywords were Prevalence, Prevalent, Epidemiology, Dupuytren Contracture, Dupuytren and Incidence. Subsequently, SID, MagIran, ScienceDirect, Embase, Scopus, PubMed and Web of Science databases and Google Scholar search engine were searched without a lower time limit and until June 2020. In order to analyse reliable studies, the stochastic effects model was used and the I2 index was applied to test the heterogeneity of the selected studies. Data analysis was performed within the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Software version 2.0.

Results

By evaluating 85 studies (10 in Asia, 56 in Europe, 2 in Africa and 17 studies in America) with a total sample size of 6628506 individuals, the prevalence of Dupuytren disease in the world is found as 8.2% (95% CI 5.7–11.7%). The highest prevalence rate is reported in Africa with 17.2% (95% CI 13–22.3%). According to the subgroup analysis, in terms of underlying diseases, the highest prevalence was obtained in patients with type 1 diabetes with 34.1% (95% CI 25–44.6%). The results of meta-regression revealed a decreasing trend in the prevalence of Dupuytren disease by increasing the sample size and the research year (P < 0.05).

Conclusion

The results of this study show that the prevalence of Dupuytren disease is particularly higher in alcoholic patients with diabetes. Therefore, the officials of the World Health Organization should design measures for the prevention and treatment of this disease.

Keyword: Dupuytren, Prevalence, Meta-analysis

Background

Dupuytren disease is a benign fibroproliferative disorder that results in the formation of collagen knots and fibres in the palmar fascia. The disease was discovered by Felix Plotter in 1614, yet later attributed to Baron Guillaume Dupuytren, a French physician in 1831 [1–3]. Dupuytren disease usually progresses gradually over the years and is irreversible. Dupuytren leads to abnormal flexion of the fingers, involvement of the metocarpophalangeal joints (MCP) and proximal interphalangeal joints (PIP) and can also involve the distal interphalangeal joint (DIP) [3].

In Dupuytren disease, fibrosis usually begins in the palm of the hand and extends to the fingers (the most common involved finger is the ring finger, followed by the little finger, thumb, middle finger and index finger, respectively) [4]. Dupuytren is not usually painful; however, it gradually restricts the movements of fingers in a curved manner by forming firm bands on the palms and fingers [4, 5].

The main cause of Dupuytren is not yet known, but due to the increase in immune cells and associated phenomena in the infected tissue, it is possible that the disease is related to the immune system [5]. However, numerous studies have been conducted on the factors that cause this disease, in which various genetic and environmental factors have been mentioned [4, 6]. Environmental risk factors include alcohol abuse, smoking, hand injuries, aging and intense physical occupations which involve hands [7, 8].

Also, in some diseases, such as hypertension, alcoholism, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, ischemic heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), pulmonary tuberculosis, epilepsy and rheumatoid arthritis (RA), high prevalence of Dupitren has been reported [6–10].

The Dupuytren disease is the most common genetic disorder in connective tissues, and studies have revealed that there is a significant association between the Dupuytren disease, genetics and family history. However, compared to the environmental factors, family history and masculinity have the greatest impact on the disease. The age of onset of Dupuytren disease in people with a positive family history is lower than in patients without a positive family history [11, 12].

Although the disease is not dangerous, it can cause disability in patients. People with Dupuytren face many difficulties including washing, picking up objects, wearing gloves, holding objects with hands, putting hands in pockets, keeping hands straight and pain [13]. These difficulties can reduce the quality of life of the patients [14].

Various studies have been conducted on the prevalence of the Dupuytren disease, which have reported a prevalence of between 0.2 and 56% [15]. However, there is a lack of a comprehensive study with generalized statistics on the prevalence. Considering the significance of this disease and its negative impacts on patients’ quality of life, the present study evaluates the prevalence of the Dupuytren disease in the world by using systematic review and meta-analysis.

Methods

In this systematic review and meta-analysis study, the SID, MagIran, ScienceDirect, Embase, Scopus, PubMed and Web of Science databases and the Google Scholar search engine were searched for related articles. To access the targeted articles, the following search keywords were used: Prevalence, Prevalent, Epidemiology, Dupuytren Contracture, Dupuytren and Incidence. In addition, all possible combinations of these words have been searched. No time constraints were considered in the search process and all related studies were identified and the information of these studies was transferred to the EndNote X8 bibliography management software. Therefore, all possible related articles published by June 2020 were identified and their information were transferred and analysed. In order to maximize the comprehensiveness of the search, the lists of sources used in all relevant articles found in the above search were manually reviewed.

Inclusion criteria

The studies that examined the prevalence of the Dupuytren disease in the world, the studies that were observational (non-interventional studies), and studies that their full texts were available were included in our analysis.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria were as follows: unrelated studies, studies without sufficient data, duplicate articles and studies with an unclear methodology.

Selection process

Initially, the studies that were repeated in various searched databases were excluded from this study. Subsequently, a list of the titles of all the remaining articles was prepared. In next step, the eligible articles were selected by evaluating the articles in this list. In next step, the screening was conducted by carefully reviewing the title and abstract of the remaining articles and subsequently, irrelevant articles were removed in accordance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria. In the second stage, the evaluation of the suitability of the studies, the full text of the possible relevant articles remaining from the screening stage was examined based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and at this stage, unrelated studies were omitted. To avoid bias, all steps of reviewing sources and extracting data were performed by two reviewers independently. In the case of excluding an article, the reason was documented. In cases where there was a disagreement between the two reviewers, the article was reviewed by a third reviewer.

Qualitative evaluation

In order to validate and evaluate the credibility of the articles (i.e., methodological validity and results), a checklist related to the type of study was used. STROBE checklists are commonly used to critically evaluate the observational studies such as the present study. The STROBE checklist consists of six general items including title, abstract, introduction, methods, findings and discussion. Some of these items have subitems, and in total this checklist entails 32 items. In fact, these 32 items describe different methodological aspects of a study including title, problem statement, study objectives, type of study, statistical population of the study, sampling method, the appropriate sample size, definition of variables and procedures, data collection tools, statistical analysis methods and findings. Accordingly, the maximum score that can be obtained from the qualitative evaluation in the STROBE is 32 and the cut-off point’s score is 16. Articles with the scores of 16 and above are considered articles with medium or high methodological quality. On the other hand, articles with the score of less than 16 are considered low quality [16]; low-quality articles were excluded from our work.

Data extraction

The information of all finalized articles included in the systematic review and meta-analysis processes were extracted using a pre-prepared checklist. This checklist included following fields: title of article, name of first author, year of publication, place of study, sample size, prevalence of Dupuytren disease and age.

Statistical analysis

To evaluate the heterogeneity of the selected studies, the I2 index was used (heterogeneities were divided into three categories: less than 25% (low heterogeneity), 25–75% (moderate heterogeneity) and more than 75% (high heterogeneity)). In order to test the publication bias and also due to the high volume of samples included in the study, Begg’s test was used at a significance level of 0.1, and corresponding funnel plots were drawn. Statistical sensitivity analysis was conducted to evaluate the effect of individual studies on the final results. In this study, meta-regression was used for additional analysis, to examine the relationship between the prevalence of the Dupuytren disease with the sample size and the year of the study. Data analysis was performed using the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Software (version 2.0).

Results

The data extracted from the previous studies on the prevalence of the Dupuytren disease were evaluated using a systematic review and meta-analysis. The work has been conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Based on the initial search in the databases, 895 potentially related articles were identified and transferred into the EndNote bibliography management software. Seventeen further studies were also added through other sources. Of the total 912 studies identified, 74 were duplicates and were therefore excluded. In the screening phase, out of 838 remaining studies, 588 articles were removed through the study of titles and abstracts and according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. In the eligibility evaluation stage, out of the remaining 250 studies, 162 articles were omitted due to irrelevance and after examining the full text of the article and similarly by considering the inclusion and exclusion criteria. At the quality evaluation stage, by reviewing the full text of the article and based on the score obtained from the STROBE checklist, out of the remaining 88 studies, 3 studies were excluded due to low methodological quality. These articles obtained the scores of less than 16 based on the STROBE checklist (Fig. 1). Hence, the total number of 85 articles was included in the final analysis stage.

Fig. 1.

The flowchart on the stages of including the studies in the systematic review and meta-analysis (PRISMA 2009)

Based on the results from the I2 99.9 test and considering the heterogeneity of the selected studies, the random effects model was used to amalgamate the results of the selected studies to approximate the common prevalence. The heterogeneity of the studies could be due to the differences in sample size, sampling error, year of the study or place of study. Of the 85 included articles in systematic review and meta-analysis with a sample size of 6628506 people, 10 studies were conducted in Asia, 56 in Europe, 2 in Africa and 17 in the Americas. The lowest and highest sample sizes were related to the studies of Ardic et al. (n = 37) [61] and Nordenskjöld et al. (n = 1,300,000), respectively [27]. The characteristics of the included studies in meta-analysis are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristic of included studies prevalence of Dupuytren

| Author, year, reference | Age (years) | Country | Sample size total | Sample size male | Sample size female | Prevalence % | Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asia | |||||||

| Agrawal et al., 2014, [17] | 3783 ≤ 50, 1949 ≥ 50 | India | 5732 | 2516 | 3216 | 7.2 | Diabetic population |

| Kiani et al., 2014, [18] | 54.0 ± 13.2 Fe, 51.6 ± 16.5 Ma | Iran | 432 | 134 | 298 | 7.4 | Diabetic population |

| Al-Matubsi et al., 2011, [19] | 51.82 ± 11.68 | Jordan | 187 | 77 | 110 | 17.6 | Diabetic population |

| Lee et al., 2018, [20] | 54 men, 49.5 women (mean) | South Korea | 16630 | - | - | 3.2 | General population |

| Rajendran et al. (1), 2010, [21] | 53.8 ± 8.2 | India | 206 | 98 | 108 | 84.0 | Diabetic population |

| Rajendran et al. (2), 2010, [21] | 52.4 ± 8.3 | India | 203 | 106 | 97 | 58.6 | General population |

| Tajica et al., 2014, [22] | 66.7 (40–92) | Japan | 401 | 163 | 238 | 7.0 | General population |

| Yeh et al., 2015, [23] | 60.7 ± 18.4 (men), 53.7 ± 15.5 (women) | China | 1078 | 681 | 397 | 8.9 | General population |

| Pandey et al. (1), 2013, [24] | 51.8 ± 11.5 (19–65) | India | 200 | 102 | 98 | 19.0 | Diabetic population |

| Pandey et al. (2), 2013, [24] | 53.1 ± 12.5 (19–65) | India | 200 | 99 | 101 | 6.0 | General population |

| Europe | |||||||

| Degreef et al., 2010, [25] | ≥ 50 | Belgium | 500 | 265 | 235 | 31.6 | General population |

| Gumundsson et al., 1999, [26] | 46–74 | Norway | 1297 | 1297 | 0 | 19.2 | General population |

| Nordenskjöld et al., 2017, [27] | Over 20 | Sweden | 1300000 | 5208 | 1299 | 0.5 | General population |

| Wijnen et al., 2017, [28] | Born between 1900 and 1999 | Belgium | 215251 | 451 | 274 | 0.3 | General population |

| Arafa et al. (1), 1984, [29] | Over 30 | England | 392 | 131 | 261 | 6.4 | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| Arafa et al. (2), 1984, [29] | Over 30 | England | 555 | 254 | 301 | 16.0 | General population |

| Arafa et al. (3), 1991, [30] | Over 30 | England | 342 | 177 | 165 | 12.0 | David Lewis Center Of Epilepsy Patient |

| Arafa et al. (4), 1991, [30] | Over 30 | England | 373 | 241 | 132 | 37.8 | Chalfont Center Of Epilepsy Patient |

| Arkkila et al., 1996, [31] | 33.2 ± 9.9 type I; 61.1 ± 12.4 type II | Finland | 425 | 200 | 225 | 13.9 | Diabetic population |

| Arkkila et al., 2000, [32] | 43.4 ± 9.5 | Finland | 28 | 28 | 0 | 32.1 | Diabetes type I |

| Attali et al. (1), 1987, [33] | 54 ± 18 | France | 432 | 246 | 186 | 28 | Different groups which are named |

| Attali et al. (2), 1987, [33] | 58.9 ± 22.7 | France | 174 | 77 | 97 | 12.6 | General population |

| Bergenudd et al., 1993, [34] | 55 years old | Sweden | 574 | 255 | 319 | 6.3 | Light, moderate and heavy physical workers |

| French et al., 1990, [35] | 23–56 | England | 50 | 50 | 0 | 6.0 | Patients with HIV |

| Bennett (1), 1982, [36] | 15–64 | UK | 216 | 216 | 0 | 7.4 | Manual workers in bagging and packing plant |

| Bennett (2), 1982, [36] | 15–64 | UK | 84 | 84 | 0 | 1.2 | Workers in no bagging or packing |

| Broekstra et al. (1), 2016, [37] | 65–71 | Netherlands | 169 | 169 | 0 | 51.5 | Hockey players aged over 60 years |

| Broekstra et al. (2), 2016, [37] | 59–71 | Netherlands | 156 | 156 | 0 | 13.5 | General population |

| Burke et al., 2005, [38] | 25–99 | UK | 97537 | 97537 | 0 | 8.1 | Miners |

| Descatha et al., 2012, | 20–59 | France | 2161 | 2161 | 0 | 1.2 | Manual workers |

| Descatha et al., 2013, [39] | 59–73 | France | 13587 | 3570 | 1017 | 7.4 | General population |

| Edington et al. (1), 1991, [40] | 62 ± 9 | UK | 200 | 124 | 76 | 23.5 | Diabetic population |

| Edington et al. (2), 1991, [40] | 58 ± 6 | UK | 170 | 103 | 67 | 24.7 | General population |

| Finsen et al., 2001, [41] | Over 50 | Norway | 456 | 261 | 195 | 7.7 | General population |

| Gamstedt et al., 1993, [42] | 19–62 (mean 42) | Sweden | 99 | 49 | 50 | 16.2 | Diabetic population |

| Kristján et al., 2000, [43] | Over 45 | Iceland | 2165 | 1297 | 868 | 13.3 | General population |

| Carson et al., 1993, [44] | 65 to 97 (mean 76.2) | UK | 400 | 400 | 0 | 13.8 | Ex-military service pensioners |

| Khan et al., 2004, [45] | Over 40 | England and Wales | 502493 | 502493 | 0 | 0.03 | General population |

| Kovacs et al. (1), 2012, [46] | 52.46 ± 13.56 | Romania | 187 | 93 | 94 | 26.7 | Diabetic population |

| Kovacs et al. (2), 2012, [46] | 51.19 ± 16.21 | Romania | 197 | 97 | 100 | 5.6 | General population |

| Lanting et al., 2013, | 50–89 | Netherlands | 763 | 348 | 415 | 22.1 | General population |

| Lennox et al., 1993, [47] | Over 60 | Scotland | 200 | 100 | 100 | 30.0 | Consecutive geriatric patients |

| Noble et al. (1), 1992, [48] | Over 30 | England | 100 | 28.0 | Alcoholic patients | ||

| Noble et al. (2), 1992, [48] | Over 30 | England | 82 | 22.0 | Hepatic non-alcoholic patient | ||

| Noble et al. (3), 1992, [48] | Over 30 | England | 100 | 8.0 | General population | ||

| Palmer et al., 2015, [49] | 16–64 | UK | 4969 | 4969 | 0 | 1.4 | General population |

| Patri et al., 1986, [50] | 20–90 | France | 155 | 76 | 79 | 9.0 | General population |

| Ramchurn et al., 2009, [51] | 55 | UK | 96 | 60 | 36 | 12.5 | Diabetic population |

| Thomas and Clarke, 1992, [52] | 25–85 | UK | 500 | 499 | 1 | 13.6 | General population |

| Caffiniire et al., 1983, [53] | 20–65 | France | 5206 | 5206 | 0 | 3.8 | Iron workers |

| Zerajic and Finsen, 2004, [54] | Over 50 | Bosnia and Herzegovina | 1207 | 610 | 597 | 25.2 | General population |

| Bulfoni (1), 1980, [55] | - | Italy | 125 | - | - | 72.0 | Alcoholic cirrhosis |

| Bulfoni (2), 1980, [55] | - | Italy | 185 | - | - | 37.8 | Hepatic alcoholic involvement without cirrhosis |

| Bulfoni (3), 1980, [55] | - | Italy | 163 | - | - | 23.9 | Alcoholism without hepatic involvement |

| Diris et al., 2003, [56] | - | France | 100 | - | - | 7.0 | Diabetic population |

| Renard et al. (1), 1994, [57] | - | France | 60 | 35.0 | Diabetic type I | ||

| Renard et al. (2), 1994, [57] | - | France | 60 | 30.0 | Diabetic type II | ||

| Renard et al. (3), 1994, [57] | - | France | 120 | 6.7 | General population | ||

| Stradner et al., 1987, [58] | - | UK | 100 | 42.0 | Diabetic population | ||

| Trybus et al., 2012, [59] | - | Poland | 101 | 14.9 | General population | ||

| Sari, 2013, [60] | 51.14 ± 15.85 | Turkey | 21450 | 6477 | 14973 | 0.04 | Physiotherapy and rehabilitation |

| Ardic et al. (1), 2002, [61] | 57.8 ± 11.9 (32–81) | Turkey | 78 | 23 | 55 | 21.8 | Diabetic population |

| Ardic et al. (2), 2002, [61] | 55.7 ± 11.5 (30–79) | Turkey | 37 | 10 | 27 | 2.7 | General population |

| Aydeniz et al. (1), 2008, [62] | 58.0 ± 9.1 | Turkey | 102 | 44 | 58 | 12.7 | Diabetic population |

| Aydeniz et al. (2), 2008, [62] | 60.1 ± 7.6 | Turkey | 101 | 50 | 51 | 3.9 | General population |

| Cakir et al., 2003, [63] | 46 ± 12 (20–76) | Turkey | 137 | 26 | 11 | 8.8 | Thyroid disease |

| Africa | |||||||

| Beighton and Valkenburg, 1974, [64] | Over 35 | South Africa | 111 | 63 | 48 | 13.5 | General population |

| Mustafa et al., 2016, [65] | 57.8 ± 9.5 (range 23–88) | South Africa | 1000 | 478 | 522 | 18.6 | Diabetic population |

| America | |||||||

| Barton and Barton (1), 2012, [66] | 48 ± 13 M/51 ± 14 W | USA | 294 | 188 | 106 | 1.0 | Hemochromatosis probands with HFE C282Y homozygosity |

| Barton and Barton (2), 2012, [66] | 48 ± 13 M/51 ± 15 W | USA | 67 | 39 | 28 | 1.5 | Hemochromatosis probands with C282y/H63d compound heterozygosity |

| Dibenedetti et al., 2011, [67] | Over 18 | USA | 23103 | 11420 | 11683 | 2.0 | General population |

| Diep et al., 2015, [68] | Over 18 | USA | 827 | 353 | 474 | 37.0 | Asymptomatic patients |

| Robert et al., 1977, [69] | 29–80 (mean 57) | USA | 55 | 13 | 42 | 10.9 | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| Larkin et al., 2014, [70] | 52.2 ± 6.9 | USA | 1217 | 633 | 584 | 8.6 | Diabetes type I |

| Patel et al., 2014, [71] | 59.1 ± 12.90 | USA | 97 | 51 | 46 | 19.6 | Patients with psoriasis |

| Alesia et al., 1999, [72] | Over 25 | USA | 324300 | 0.3 | General population | ||

| Su et al. (1), 1972, [73] | - | USA | 142 | 142 | 0 | 12.0 | General population |

| Su et al. (2), 1972, [73] | - | USA | 130 | 130 | 0 | 19.2 | Alcoholic without cirrhosis |

| Su et al. (3), 1972, [73] | - | USA | 133 | 133 | 0 | 18.0 | Alcoholic with cirrhosis |

| Weinstein et al. (1), 2011, [74] | Over 40 | USA | 220748 | - | - | 0.5 | Hispanic population |

| Weinstein et al. (2), 2011, [74] | Over 40 | USA | 137205 | - | - | 0.3 | Black population |

| Weinstein et al. (3), 2011, [74] | Over 40 | USA | 118909 | - | - | 0.3 | White population |

| Weinstein et al. (4), 2011, [74] | Over 40 | USA | 70058 | - | - | 0.3 | Asian population |

| Weinstein et al. (5), 2011, [74] | Over 40 | USA | 2055 | - | - | 0.3 | Native American |

| Weinstein et al. (6), 2011, [74] | Over 40 | USA | 607119 | - | - | 0.4 | Other population |

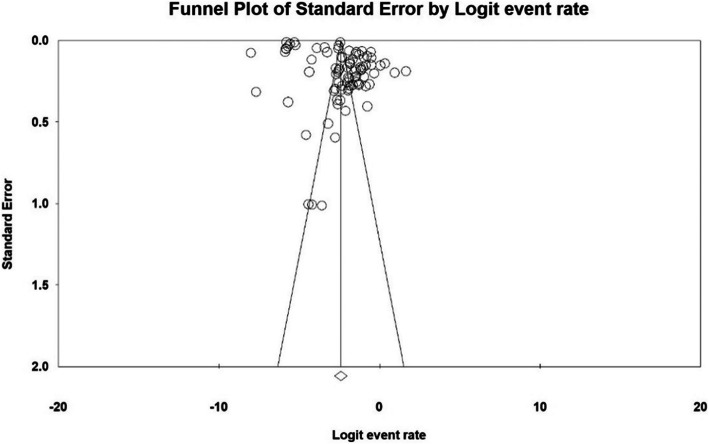

The probability of publication bias in the dissemination of the results of Dupuytren disease in the world was performed by Begg’s test (Begg and Mazumdar) at a significance level of 0.1, and through examining the corresponding Funnel plots. The results revealed no publication bias in the present study (P = 0.989) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Funnel plot’s results for the prevalence of Dupuytren in the world

According to the results of the present study, the prevalence rate of the Dupuytren disease in the world is 8.2% (95% CI 5.7–11.7%). The midpoint of each segment shows the prevalence in each study and the diamond shape shows the prevalence in the population of the entire studies (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

The global prevalence of the Dupuytren disease at 95% confidence interval

Meta-regression test

In order to investigate the effects of potential factors affecting the heterogeneity of the prevalence of the Dupuytren disease, meta-regression was used for the two factors of sample size and year of study (Figs. 4 and 5). According to Fig. 4, by increasing of sample size, the prevalence of the Dupuytren in the world decreases, which has a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05). Moreover, as reported in Fig. 5, with the increase of the year of the study, the prevalence of the Dupuytren in the world decreases; this difference is also statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Fig. 4.

Meta-regression diagram of the prevalence of Dupuytren disease in the world by sample size

Fig. 5.

Meta-regression diagram of the prevalence of Dupuytren disease in the world by year of study

Subgroup analysis

Table 2 reports the variations of the prevalence of the Dupuytren disease in different continents. The highest ratio is 17.2% which belongs to Africa (95% CI 13–22.3%). Table 3 reports the prevalence of the Dupuytren disease based on the underlying diseases. These variations are reported in the general population; diabetic population; patients with diabetic type I, diabetic type II and rheumatoid arthritis; and alcoholic patients. The highest rate is among patients diagnosed with type 1 diabetes with 34.1% (95% CI 25–44.6%).

Table 2.

The prevalence of the Dupuytren in the population of different continents

| Continents | Number of articles | Sample size | I2 | Begg and Mazumdar test | Prevalence % (95 % CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asia | 10 | 25269 | 99.3 | 1.000 | 15.3 (95 % CI 7.5–28.5) |

| Europe | 56 | 2176967 | 99.8 | 0.012 | 10.3 (95 % CI 6.4–16.2) |

| Africa | 2 | 1111 | 42 | - | 17.2 (95 % CI 13–22.3) |

| America | 17 | 4425159 | 99.8 | 0.773 | 2.3 (95 % CI 1.4–3.8) |

Table 3.

Prevalence of Dupuytren disease in the population by underlying diseases

| Continents | Number of articles | Sample size | I2 | Begg and Mazumdar test | Prevalence % (95 % CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetic population | 15 | 10161 | 97.9 | 0.843 | 18.1 (95 % CI 11.8–26.7) |

| General population | 32 | 5329922 | 99.9 | 0.011 | 6.4 (95 % CI 3.8–10.5) |

| Diabetic type I | 2 | 88 | 0 | - | 34.1 (95 % CI 25–44.6) |

| Diabetic type II | 2 | 260 | 3.3 | - | 25.1 (95 % CI 20.1–31) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 2 | 447 | 33.1 | - | 7.5 (95 % CI 4.6–12) |

| Alcoholic patient | 5 | 693 | 81.4 | 0.220 | 24.0 (95 % CI 17.2–32.3) |

Discussion

Dupuytren is a hand deformity that usually progresses over several years. This condition affects a layer of tissue under the skin of the palm. Tissue knots form under the skin and eventually create a thick cord that can bend one or more fingers. This results in the patient not being able to completely straighten the affected fingers [20]. Dupuytren can make it difficult to use hands to perform certain tasks. Since the thumb and the forefinger are not usually affected, many people do not have much discomfort or inability to perform motor activities such as writing. Yet, with the progression of the disease, the ability to use the hands becomes limited [37]. The risk factors for Dupuytren include aging (Dupuytren usually occurs after the age of 50), gender, smoking and alcohol consumption, diabetes, family history and geographic location [28]. Due to the significance of this disease and the lack of general statistics on its status worldwide, the aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of the Dupuytren disease in the world through a systematic review and meta-analysis study.

According to the present study, the prevalence of Dupuytren disease in the world is 8.2% (95% CI 5.7–11.7%). The highest prevalence of Dupuytren disease was related to the study of Rajendran et al. [21] with 84% and the lowest prevalence was related to the study of Weinstein et al. [74] with 0.3%. In a meta-analysis conducted by Lanting et al. [75], the prevalence of Dupuytren in the Western countries was reported as 6–6.31% [75]. Also, Carloni et al. [76], using a meta-analysis work, reported this rate as 1–5.9% [76]. Our study findings are almost in line with these research works. However, the cause of the minor differences between the present study and these pieces of research can be justified based on the number of articles reviewed in the present study which is higher (85 articles in the present study vs. 17 articles in the study of Carloni et al. [76] and 23 articles in the study of Lanting et al. [75]). Moreover, the present study examined patients with different races and geographical locations worldwide.

Due to the change in the demographics in different countries around the world, it is essential to carefully examine the prevalence of Dupuytren disease to acknowledge policy-makers. This can lead to raise more awareness to the disease’s processes and consequences. Therefore, according to the subgroups analysis based on different continents, the highest rate of the prevalence of Dupuytren is related to the African continent with 17.2% (95% CI 13–22.3%), and the lowest is related to the American continent with 2.3% (95% CI 1.4–3.8%).

According to the subgroup’s analysis of the underlying diseases, the highest prevalence is primarily in patients with type I diabetes with 34.1%. The second highest rate is among patients with type II diabetes with 25.1%. Diabetes is one of the most common metabolic diseases, in which hyperglycemia causes pathophysiological changes in various organs. Diabetes is a disease with systemic involvement which includes musculoskeletal problems such as Dupuytren. This is more common in diabetic patients compared to the general population [77]. Dupuytren disease is somewhat preventable and treatable, but not completely cured [78]. Therefore, diagnosis, prevention and treatment of this complication are essential. It is recommended that musculoskeletal examination is included as part of periodic care in diabetic patients.

Furthermore, according to the subgroup’s analysis of the underlying diseases, the highest prevalence of the disease, after diabetic patients, is related to alcoholic patients (24%). Various studies reveal that the prevalence of Dupuytren in alcoholics is higher than the general population; however, the cause is still not clear [79, 80]. Alcohol consumption and its misuse as a social harm have complex interconnected economic, social and cultural causes and have serious safety and health consequences for the society. Therefore, it requires a comprehensive and unified plan along with cooperation between various governing departments.

The most comprehensive study in terms of sample size is the research work conducted by Nordenskjöld et al. in Sweden [27]. They reported prevalence of Dupuytren disease as 0.5% which differs from the findings of our work. However, it is consistent with the results of meta-regression analysis, which revealed that by increasing the sample size and study year, the prevalence rate in the world decreases. According to the results of meta-regression, with the increase of the study year, the prevalence of the world decreases. This reduction can be associated with appropriate preventive measures such as controlling diabetes and blood sugar, avoiding smoking and alcohol consumption and treatment of liver disease.

Dupuytren disease has considerable negative consequences for the patients. Hence, it is important to take measures to achieve effective or supportive treatments to reduce the symptoms of the disease. In addition, in recent years, studying musculoskeletal conditions have been considered an important issue in health care. Since these studies can provide useful information for health care providers and enhance health and therapeutic interventions to improve the quality of services. Ultimately these could lead to improving the quality of life of the patients [81–83].

Limitations

It can be highlighted that some samples were not based on random selection which, to some extent, appeared as a limitation. Also, other limitations can be signified such as variations in presenting the findings of articles, implementation methods and inaccessibility of the full text of the papers which are presented at the conferences.

Implication

The results of this study reveal that the prevalence of Dupuytren disease is high, particularly in alcoholic patients with diabetes. Therefore, the officials of the World Health Organization (WHO) are required to develop measures for the prevention and treatment of this disease.

Acknowledgements

We hereby express our gratitude and appreciation to the Student Research Committee of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences.

Abbreviations

- WHO

World Health Organization

- MCP

Metocarpophalangeal

- PIP

Proximal interphalangeal

- DIP

Distal interphalangeal

- COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- RA

Rheumatoid arthritis

- SID

Scientific Information Database

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis

- STROBE

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology for cross-sectional Study

Authors’ contributions

ND, MBH, MH and MK contributed to the design. MM contributed to the statistical analysis and participated in most of the study steps. NF, MN and YS prepared the manuscript. SHSH and AD assisted in designing the study and helped in the interpretation of the study. All authors have read and approved the content of the manuscript.

Funding

By Deputy for Research and Technology, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences (IR) (3010357), and it had no role in the study process.

Availability of data and materials

Datasets are available through the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Nader Salari, Email: n_s_514@yahoo.com.

Mohammadbagher Heydari, Email: mb_heydari@kums.ac.ir.

Masoud Hassanabadi, Email: masoud.hassanabadi@northampton.ac.uk.

Mohsen Kazeminia, Email: mohsenkaz221@gmail.com.

Nikzad Farshchian, Email: n.farshchian@kums.ac.ir.

Mehrdad Niaparast, Email: niaparast@razi.ac.ir.

Yousef Solaymaninasab, Email: yousef.1375@gmail.com.

Masoud Mohammadi, Email: Masoud.mohammadi1989@yahoo.com.

Shamarina Shohaimi, Email: shamarina@upm.edu.my.

Alireza Daneshkhah, Email: ac5916@coventry.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Peimer CA, Blazar P, Coleman S, Kaplan FTD, Smith T, Tursi JP, et al. Dupuytren contracture recurrence following treatment with collagenase clostridium histolyticum (CORDLESS Study): 3-Year Data. J Hand Surgery. 2013;38(1):12–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pess GM, Pess RM, Pess RA. Results of needle aponeurotomy for Dupuytren contracture in over 1,000 fingers. J Hand Surgery. 2012;37(4):651–656. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peimer CA, Blazar P, Coleman S, Kaplan FTD, Smith T, Lindau T. Dupuytren contracture recurrence following treatment with collagenase clostridium histolyticum (CORDLESS [Collagenase Option for Reduction of Dupuytren Long-Term Evaluation of Safety Study]): 5-Year Data. Journal of Hand Surgery. 2015;40(8):1597–1605. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2015.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Michou L, Lermusiaux J-L, Teyssedou J-P, Bardin T, Beaudreuil J, Petit-Teixeira E. Genetics of Dupuytren’s disease. Joint Bone Spine. 2012;79(1):7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2011.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shih B, Bayat A. Scientific understanding and clinical management of Dupuytren disease. Nature Reviews Rheumatology. 2010;6(12):715–726. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eckerdal D, Nivestam A, Dahlin LB. Surgical treatment of Dupuytren’s disease – outcome and health economy in relation to smoking and diabetes. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:117–123. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-15-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morelli I, Fraschini G, Banfi AE. Dupuytren’s Disease: Predicting factors and associated conditions. A single center questionnaire-based case-control study. Archives of Bone and Joint Surgery. 2017;5(6):384–393. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Descatha A, Bodin J, Ha C, Goubault P, Lebreton M, Chastang JF, et al. Heavy manual work, exposure to vibration and Dupuytren’s disease? Results of a surveillance program for musculoskeletal disorders. Occupational and environmental medicine. 2012;69(4):296–299. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2011-100319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Broekstra DC, Groen H, Molenkamp S, Werker PM, van den Heuvel ER. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the strength and consistency of the associations between Dupuytren disease and diabetes mellitus, liver disease, and epilepsy. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2018;141(3):367–379. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000004120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lanting R, van den Heuvel ER, Westerink B, Werker PMN. Prevalence of Dupuytren disease in the Netherlands. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2013;132(2):394–403. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182958a33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Becker K, Tinschert S, Lienert A, Bleuler P, Staub F, Meinel A, et al. The importance of genetic susceptibility in Dupuytren’s disease. Clinical genetics. 2015;87(5):483–487. doi: 10.1111/cge.12410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dolmans GH, de Bock GH, Werker PM. Dupuytren diathesis and genetic risk. The Journal of Hand Surgery. 2012;37(10):2106. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodrigues J, Zhang W, Scammell B, Davis T. What patients want from the treatment of Dupuytren’s disease—is the Unité Rhumatologique des Affections de la Main (URAM) scale relevant? Journal of Hand Surgery (European Volume). 2015;40(2):150–154. doi: 10.1177/1753193414524689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilburn J, McKenna S, Perry-Hinsley D, Bayat A. The impact of Dupuytren disease on patient activity and quality of life. The Journal of hand surgery. 2013;38(6):1209–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2013.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hindocha S, McGrouther DA, Bayat A. Epidemiological evaluation of Dupuytren’s disease incidence and prevalence rates in relation to etiology. Hand. 2009;4(3):256–269. doi: 10.1007/s11552-008-9160-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salari N, Mohammadi M, Vaisi-Raygani A, Abdi A, Shohaimi S, Khaledipaveh B, Daneshkhah A, Jalali R. The prevalence of severe depression in Iranian older adult: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. BMC Geriatrics. 2020;20(1):39–49. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-1444-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agrawal RP, Gothwal S, Tantia P, Agrawal R, Rijhwani P, Sirohi P, et al. Prevalence of rheumatological manifestations in diabetic population from North-West India. The Journal of the Association of Physicians of India. 2014;62(9):788–792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kiani J, Goharifar H, Moghimbeigi A, Azizkhani H. Prevalence and risk factors of five most common upper extremity disorders in diabetics. Journal of research in health sciences. 2014;14(1):92–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Matubsi HY, Hamdan F, Alhanbali OA, Oriquat GA, Salim M. Diabetic hand syndromes as a clinical and diagnostic tool for diabetes mellitus patients. Diabetes research and clinical practice. 2011;94(2):225–229. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee KH, Kim JH, Lee CH, Kim SJ, Jo YH, Lee M, et al. The epidemiology of Dupuytren’s disease in Korea: a nationwide population-based study. Journal of Korean medical science. 2018;33(31):e204. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2018.33.e204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ravindran Rajendran S, Bhansali A, Walia R, Dutta P, Bansal V, Shanmugasundar G. Prevalence and pattern of hand soft-tissue changes in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes & metabolism. 2011;37(4):312–317. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tajika T, Kobayashi T, Kaneko T, Tsunoda D, Tsunoda K, Sutou T, et al. Epidemiological study for personal risk factors and quality of life related to Dupuytren’s disease in a mountain village of Japan. Journal of orthopaedic science : official journal of the Japanese Orthopaedic Association. 2014;19(1):64–70. doi: 10.1007/s00776-013-0478-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yeh C-C, Huang K-F, Ho C-H, Chen K-T, Liu C, Wang J-J, et al. Epidemiological profile of Dupuytren’s disease in Taiwan (Ethnic Chinese): a nationwide population-based study. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2015;16(1):20–27. doi: 10.1186/s12891-015-0476-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pandey A, Usman K, Reddy H, Gutch M, Jain N, Qidwai S. Prevalence of hand disorders in type 2 diabetes mellitus and its correlation with microvascular complications. Annals of medical and health sciences research. 2013;3(3):349–354. doi: 10.4103/2141-9248.117942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Degreef I, De Smet L. A high prevalence of Dupuytren’s disease in Flanders. Acta orthopaedica Belgica. 2010;76(3):316–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guomundsson KG, Arngrímsson R, Sigfússon N, Jónsson T. Prevalence of joint complaints amongst individuals with Dupuytren’s disease - from the Reykjavik study. Scand J Rheumatol. 1999;28(5):300–304. doi: 10.1080/03009749950155481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nordenskjöld J, Englund M, Zhou C, Atroshi I. Prevalence and incidence of doctor-diagnosed Dupuytren’s disease: a population-based study. The Journal of hand surgery, European volume. 2017;42(7):673–677. doi: 10.1177/1753193416687914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Degreef I. Comorbidity in Dupuytren disease. Acta orthopaedica Belgica. 2016;82(3):643–648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arafa M, Steingold RF, Noble J. The incidence of Dupuytren’s disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. The Journal of Hand Surgery: British & European Volume. 1984;9(2):165–166. doi: 10.1016/S0266-7681(84)80020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arafa M, Noble J, Royle SG, Trail IA, Allen J. Dupuytren’s and epilepsy revisited. J Hand Surg (GBR). 1992;17(2):221–224. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681(92)90095-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arkkila PET, Kantola IM, Viikari JSA, Rönnemaa T. Shoulder capsulitis in type I and II diabetic patients: association with diabetic complications and related diseases. ANN RHEUM DIS. 1996;55(12):907–914. doi: 10.1136/ard.55.12.907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arkkila PET, Koskinen PJ, Kantola IM, Rönnemaa T, Seppänen E, Viikari JS. Dupuytren’s disease in type I diabetic subjects: investigation of biochemical markers of type III and I collagen. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2000;18(2):215–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Attali P, Ink O, Pelletier G, Vernier C, Jean F, Moulton L, et al. Dupuytren’s contracture, alcohol consumption, and chronic liver disease. Archives of internal medicine. 1987;147(6):1065–1067. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1987.00370060061012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bergenudd H, Lindgärde F, Nilsson BE. Prevalence of Dupuytren’s contracture and its correlation with degenerative changes of the hands and feet and with criteria of general health. Journal of hand surgery (Edinburgh, Scotland). 1993;18(2):254-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.French PD, Kitchen VS, Harris JR. Prevalence of Dupuytren’s contracture in patients infected with HIV. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 1990;301(6758):967–977. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6758.967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bennett B. Dupuytren’s contracture in manual workers. BR J IND MED. 1982;39(1):98–100. doi: 10.1136/oem.39.1.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Broekstra DC, van den Heuvel ER, Lanting R, Harder T, Smits I, Werker PMN. Dupuytren disease is highly prevalent in male field hockey players aged over 60 years. British journal of sports medicine. 2018;52(20):1327–1331. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burke FD, Proud G, Lawson IJ, McGeoch KL, Miles JN. An assessment of the effects of exposure to vibration, smoking, alcohol and diabetes on the prevalence of Dupuytren’s disease in 97,537 miners. The Journal of hand surgery, European volume. 2007;32(4):400–406. doi: 10.1016/J.JHSE.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Descatha A, Carton M, Mediouni Z, Dumontier C, Roquelaure Y, Goldberg M, et al. Association among work exposure, alcohol intake, smoking and Dupuytren’s disease in a large cohort study (GAZEL) BMJ Open. 2014;4(1):e004214. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eadington DW, Patrick AW, Frier BM. Association between connective tissue changes and smoking habit in type 2 diabetes and in non-diabetic humans. Diabetes research and clinical practice. 1991;11(2):121–125. doi: 10.1016/0168-8227(91)90101-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Finsen V, Dalen H, Nesheim J. The prevalence of Dupuytren’s disease among 2 different ethnic groups in northern Norway. The Journal of hand surgery. 2002;27(1):115–117. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.2002.29486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gamstedt A, Holm-Glad J, Ohlson CG, Sundström M. Hand abnormalities are strongly associated with the duration of diabetes mellitus. Journal of internal medicine. 1993;234(2):189–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1993.tb00729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gudmundsson KG, Arngrímsson R, Sigfússon N, Björnsson A, Jónsson T. Epidemiology of Dupuytren’s disease: clinical, serological, and social assessment. The Reykjavik Study. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2000;53(3):291–296. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(99)00145-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carson J, Clarke C. Dupuytren’s contracture in pensioners at the Royal Hospital Chelsea. Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of London. 1993;27(1):25–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khan AA, Rider OJ, Jayadev CU, Heras-Palou C, Giele H, Goldacre M. The role of manual occupation in the aetiology of Dupuytren’s disease in men in England and Wales. The Journal of Hand Surgery: British & European Volume. 2004;29(1):12–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsb.2003.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kovacs D, Demian L, Babeş A. Prevalence and risk of Dupuytrèn disease in patients with diabetes versus non-diabetic patients. Rom J Diabetes Nutr Metab Dis. 2012;19(4):373–380. doi: 10.2478/v10255-012-0043-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lennox IA, Murali SR, Porter R. A study of the repeatability of the diagnosis of Dupuytren’s contracture and its prevalence in the grampian region. Journal of hand surgery (Edinburgh, Scotland). 1993;18(2):258-61. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Noble J, Arafa M, Royle SG, McGeorge G, Crank S. The association between alcohol, hepatic pathology and Dupuytren’s disease. The Journal of Hand Surgery: British & European Volume. 1992;17(1):71–74. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681(92)90015-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Palmer KT, D’Angelo S, Syddall H, Griffin MJ, Cooper C, Coggon D. Dupuytren’s contracture and occupational exposure to hand-transmitted vibration. Occup Environ Med. 2014;71(4):241–245. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2013-101981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Patri B, Gatto A. Raynaud’s syndrome, Dupuytren’s contracture, force of prehension and sensibility of the hand. A study of the age related variations. Annales de Chirurgie de la Main. 1986;5(2):144–147. doi: 10.1016/S0753-9053(86)80029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ramchurn N, Mashamba C, Leitch E, Arutchelvam V, Narayanan K, Weaver J, et al. Upper limb musculoskeletal abnormalities and poor metabolic control in diabetes. European journal of internal medicine. 2009;20(7):718–721. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thomas PR, Clarke D. Vibration white finger and Dupuytren’s contracture: are they related? Occupational medicine (Oxford, England). 1992;42(3):155-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.de la Caffinière JY, Wagner R, Etscheid J, Metzger F. Travail manuel et maladie de dupuytren: Résultat d’une enquête informatisée en milieu sidérurgique. Annales de Chirurgie de la Main. 1983;2(1):66–72. doi: 10.1016/S0753-9053(83)80084-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zerajic D, Finsen V. Dupuytren’s disease in Bosnia and Herzegovina. An epidemiological study. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2004;5:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-5-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bulfoni A. Vascular spiders, palmar erythema and Dupuytren’s contracture during alcoholic hepatic cirrhosis. ARCH SCI MED. 1980;137(2):355–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Diris N, Colomb M, Leymarie F, Durlach V, Caron J, Bernard P. Non infectious skin conditions associated with diabetes mellitus: a prospective study of 308 cases. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2003;130(11):1009–1014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Renard E, Jacques D, Chammas M, Poirier JL, Bonifacj C, Jaffiol C, et al. Increased prevalence of soft tissue hand lesions in type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus: various entities and associated significance. Diabete & metabolisme. 1994;20(6):513–521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stradner F, Ulreich A, Pfeiffer KP. Dupuytren’s plamar contraction as an attendant disease of diabetes mellitus. WIEN MED WOCHENSCHR. 1987;137(4):89–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Trybus M, Bednarek M, Budzyński P, Gniadek M, Lorkowski J. Concomitance of Ledderhose’s disease with Dupuytren’s contracture. Own experience. Prz Lek. 2012;69(9):663–666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sari Z, Yurdalan SU, Polat MG, Horoz H, Camcioǧlu B. Prevalence of isolated hand problems in physiotherapy and rehabilitation centres in Istanbul. Fiz Rehab. 2013;24(1):88–92. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ardic F, Soyupek F, Kahraman Y, Yorgancioglu R. The musculoskeletal complications seen in type II diabetics: predominance of hand involvement. Clin Rheumatol. 2003;22(3):229–233. doi: 10.1007/s10067-003-0704-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Aydeniz A, Gursoy S, Guney E. Which musculoskeletal complications are most frequently seen in type 2 diabetes mellitus? The Journal of international medical research. 2008;36(3):505–511. doi: 10.1177/147323000803600315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cakir M, Samanci N, Balci N, Balci MK. Musculoskeletal manifestations in patients with thyroid disease. Clinical endocrinology. 2003;59(2):162–167. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2003.01786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Beighton P, Valkenburg HA. Bone and joint disorders on Tristan da Cunha. S AFR MED J. 1974;48(17):743–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mustafa KN, Khader YS, Bsoul AK, Ajlouni K. Musculoskeletal disorders of the hand in type 2 diabetes mellitus: prevalence and its associated factors. International journal of rheumatic diseases. 2016;19(7):730–735. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.12617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Barton JC, Barton JC. Dupuytren’s contracture in Alabama HFE hemochromatosis probands. Clinical medicine insights Arthritis and musculoskeletal disorders. 2012;5:67–75. doi: 10.4137/CMAMD.S9935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dibenedetti DB, Nguyen D, Zografos L, Ziemiecki R, Zhou X. Prevalence, incidence, and treatments of Dupuytren’s disease in the United States: results from a population-based study. Hand (New York, NY). 2011;6(2):149-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 68.Diep GK, Agel J, Adams JE. Prevalence of palmar fibromatosis with and without contracture in asymptomatic patients. Journal of plastic surgery and hand surgery. 2015;49(4):247–250. doi: 10.3109/2000656X.2015.1034724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gray RG, Gottlieb NL. Hand flexor tenosynovitis in rheumatoid arthritis. Prevalence, distribution, and associated rheumatic features. Arthritis and rheumatism. 1977;20(4):1003–1008. doi: 10.1002/art.1780200414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Larkin ME, Barnie A, Braffett BH, Cleary PA, Diminick L, Harth J, et al. Musculoskeletal complications in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes care. 2014;37(7):1863–1869. doi: 10.2337/dc13-2361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Patel M, Freeman NR, Dhaliwal S, Wright N, Daoud Y, Ryan C, et al. The prevalence of Dupuytren contractures in patients with psoriasis. Clinical and experimental dermatology. 2014;39(8):894–899. doi: 10.1111/ced.12424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Saboeiro AP, Pokorny JJ, Shehadi SI, Virgo KS, Johnson FE. Racial distribution of Dupuytren’s disease in Department of Veterans Affairs patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;106(1):71–75. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200007000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Su CK, Patek AJ., Jr Dupuytren’s contracture: its association with alcoholism and cirrhosis. Arch Intern Med. 1970;126(2):278–281. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1970.00310080084012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Weinstein AL, Haddock NT, Sharma S. Dupuytren’s disease in the Hispanic population: a 10-year retrospective review. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2011;128(6):1251–1256. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318230bf0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lanting R, Broekstra DC, Werker PM, van den Heuvel ER. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the prevalence of Dupuytren disease in the general population of Western countries. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2014;133(3):593–603. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000438455.37604.0f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Carloni R, Gandolfi S, Elbaz B, Bonmarchand A, Beccari R, Auquit-Auckbur I. Dorsal Dupuytren’s disease: a systematic review of published cases and treatment options. Journal of Hand Surgery (European Volume). 2019;44(9):963–971. doi: 10.1177/1753193419852171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shardha AK, Vaswani AS, Faraz A, Alam MT, Kumar P. Frequency and risk factors associated with hypomagnesaemia in hypokalemic type-2 diabetic patients. Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons--Pakistan : JCPSP. 2014;24(11):830–835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zamani B, Matini SM, Jamali R, Taghadosi M. Frequency of musculoskeletal complications among the diabetic patients referred to Kashan diabetes center during 2009-10. KAUMS Journal (FEYZ). 2011;15(3):225–231. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sakai A, Zenke Y, Menuki K, Yamanaka Y, Tajima T, Uchida S. Current smoking is associated with delayed wound healing but not with improvement of contracture after the open palm technique for Dupuytren’s disease. The Journal of Hand Surgery (Asian-Pacific Volume). 2019;24(01):65–71. doi: 10.1142/S2424835519500127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Grazina R, Teixeira S, Ramos R, Sousa H, Ferreira A, Lemos R. Dupuytren’s disease: where do we stand? EFORT Open Reviews. 2019;4(2):63–69. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.4.180021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Leung R, Capstick R, Lei A, Nour D, Rozen WM, Hunter-Smith DJ. Morbidity of interventions in previously untreated Dupuytren disease: a systematic review. European Journal of Plastic Surgery. 2019;42(2):111–118. doi: 10.1007/s00238-018-1490-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Eiriksdottir A, Atroshi I. A new finger-preserving procedure as an alternative to amputation in recurrent severe Dupuytren contracture of the small finger. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2019;20(1):323. doi: 10.1186/s12891-019-2701-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kan HJ, Verrijp FW, Hovius SE, van Nieuwenhoven CA, Group DD. Selles RW. Recurrence of Dupuytren’s contracture: a consensus-based definition. PloS one. 2017;12(5):e0164849. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Datasets are available through the corresponding author upon reasonable request.