Abstract

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is a deadly disease, whose main molecular trait is the MAPK pathway activation due to KRAS mutation, which is present in 90% of cases.

The genetic landscape of KRAS wild type PDAC can be divided into three categories. The first is represented by tumors with an activated MAPK pathway due to BRAF mutation that occur in up to 4% of cases. The second includes tumors with microsatellite instability (MSI) due to defective DNA mismatch repair (dMMR), which occurs in about 2% of cases, also featuring a high tumor mutational burden. The third category is represented by tumors with kinase fusion genes, which marks about 4% of cases. While therapeutic molecular targeting of KRAS is an unresolved challenge, KRAS-wild type PDACs have potential options for tailored treatments, including BRAF antagonists and MAPK inhibitors for the first group, immunotherapy with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 agents for the MSI/dMMR group, and kinase inhibitors for the third group.

This calls for a complementation of the histological diagnosis of PDAC with a routine determination of KRAS followed by a comprehensive molecular profiling of KRAS-negative cases.

Keywords: KRAS, BRAF, MSI, dMMR, fusion genes, pancreatic cancer

Background

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is the seventh leading cause of global cancer-related deaths in industrialized countries, projected to become the second most common in the next decade worldwide [1–3]. More than 80% of PDAC patients present with locally advanced or metastatic disease, not amenable to surgical resection with curative intent, at the time of diagnosis [3, 4]. Despite progress in the chemotherapeutic treatment of PDAC, long-term survival remains dismal, with less than 10% of patients alive 5 years after diagnosis [5, 6]. To improve PDAC survival significantly, new therapeutic strategies are needed. One of the most promising tools is represented by the integration of histology with molecular pathology, to identify potential molecular targets for tailored treatments [7].

From a genetic point of view, PDAC is a composite disease, showing a very complex network of point mutations, epigenetic alterations and chromosomal structural variants [8, 9]. Within this complexity, however, the master driver is the KRAS (Kirsten rat sarcoma) oncogene [8–10], mutationally activated in over 90% of cases and recently reported to be more common in older (≥50 years) and female patients [11]. Notably, KRAS mutations can be detected with reliable sensitivity and specificity also through liquid biopsy in PDAC patients [12].

KRAS encodes a small GTPase, which acts as a transducer-effector, cooperating with cell surface receptor tyrosine kinases [10]. Once triggered, it activates different intracellular pathways involved in carcinogenesis, such as proliferation and cell migration, evasion of the immune system, and block of apoptosis [10]. Among the different pathways interrelating with KRAS function, the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway is a crucial one [8–10].

Although many therapeutic efforts have been made to target the function of mutated KRAS oncoprotein, they have been unsuccessful in substantially modifying PDAC prognosis. For example, three recent phase 2 trials evaluated MAPK inhibitors alone or in combination with gemcitabine in locally advanced and/or metastatic PDAC, and failed to show any survival benefit [13–16]. Other efforts include 4 studies that evaluated KRAS vaccines in PDAC patients: three studies that looked at RAS peptide vaccines and one that used GI-4000, a tarmogen (targeted molecular immunogen) designed to target cells with mutant KRAS [17–21]. Furthermore, the targeted drug tipifarnib that inhibits the Ras-dependent growth of cancer cells was tested in a large phase 3 trial and a phase 1 dose escalation trial in combination with gemcitabine in advanced PDAC [22, 23]. However, none of these studies achieved significant survival benefits in PDAC patients. Notably, a recent report regarding extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK) in KRAS-mutated PDAC, based on cell lines, pancreatic cancer organoids, and xenograft mouse-models, showed that ERK inhibition in cancer-associated stromal cells can suppress cancer-stromal interactions and PDAC metastatic potential [24]. Along these lines, Sun and colleagues, reported that inhibition of the phosphorylation of transgelin-2, a novel target of KRAS-ERK signaling, may be a potential therapeutic strategy for targeting PDAC with KRAS mutation, using PDAC cell lines, immunohistochemistry on PDAC tissues, and xenograft-mouse models [25]. Although promising, such findings are exploratory and still without a direct clinical translation. These points highlight the difficulties in targeting KRAS, and this situation still represents one of the most important reasons that can explain the high-mortality rate of PDAC also in the era of precision oncology [10, 26]. Moreover, Kim and colleagues reported that PDAC patients with KRAS mutations display a worse response to gemcitabine-based chemotherapy and shorter overall survival than those with KRAS wild-type [27]. Along the same lines, Windon and colleagues confirmed a survival disadvantage for KRAS mutant patients, showing that such adverse prognostic effect was independent of mismatch repair status and the specific chemotherapy regimen employed [28]. These findings warrant further investigation, as they may support new strategies for implementing precision oncology in PDAC patients. For example, using a specific gene signature for KRAS dependency, recently led to the identification and validation of decitabine as a potent inhibitor of growth in KRAS-dependent pancreatic cancer cells and patient-derived xenograft models [29], an approach that is now being translated to the clinic.

Intriguingly, a not-negligible proportion of PDAC (about 8–12%) does not harbor KRAS mutations [3, 8, 9, 11]. The definition of the genetic landscape of KRAS wild-type PDAC has been recently improved by whole-genome sequencing studies [8, 11], which highlighted the occurrence of several genetic alterations representing potential targets for tailored therapy. At this time, KRAS wild-type tumors are the molecular PDAC subgroup that might receive the highest prognostic benefits from precision oncology.

Molecular pathology and therapeutic opportunities

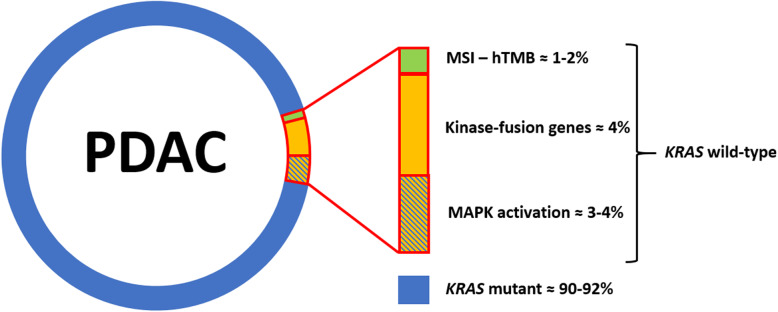

The genetic landscape of KRAS-wild type PDAC can be subdivided into three different groups: i) PDAC with the presence of an activated-MAPK in the absence of a KRAS mutation, ii) PDAC with microsatellite instability/defective DNA mismatch repair, and iii) PDAC with kinase-fusion genes. These alterations dominate the KRAS wild type PDAC genetic landscape, and occur in different proportions (Fig. 1). This review will focus on molecular pathology and therapeutic opportunities in these specific PDAC molecular settings.

Fig. 1.

The genetic landscape of KRAS wild-type pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is shown. The vast majority of cases harbored KRAS mutations, but about 8–10% of cases show other molecular alterations, including microsatellite instability (MSI) – high tumor mutational burden (hTMB), kinase fusion genes, and activation of the MAPK pathway without KRAS involvement

The MAPK pathway and the role of BRAF (B-Raf proto-oncogene)

The MAPK pathway is the most important core signaling pathway in PDAC [3, 8, 9, 11, 26], in which the activation of RAS is a crucial step. Such activation is mediated by a guanine nucleotide exchange factor [30]. Active RAS is self-inactivated by intrinsic GTPase activity, based on a GTPase-activating protein [31]. KRAS mutations in PDAC often involve codons 12, 13 and 61; most of them are G12D or G12R substitutions, which decrease the intrinsic GTPase activity, thus resulting in prolonged activation of RAS [31].

Notably, the activation of MAPK pathway is possible also in the absence of KRAS mutations [30]. A recent study by Singhi et al. definitively demonstrated that the MAPK signaling is activated in about one third of KRAS wild-type PDAC [11]. In this cohort, BRAF alterations were the most prevalent, and included activating missense mutations, amplification and kinase fusions. BRAF mutations were mutually exclusive with those of KRAS; furthermore, kinase fusions in BRAF were not present in KRAS mutant cases [11]. BRAF encodes for the B-RAF proto-oncogene, a serine/threonine kinase belonging to a family of MAPK kinases [30]. The most common mutations in BRAF usually involve codon 600 and often results in a V600E substitution, leading to constitutive activation of its kinase function, which is the results also of the other aforementioned alterations [32, 33]. The mutual exclusivity of KRAS and BRAF mutations in PDAC suggests that the activating mutations of these genes can compensate for each other in PDAC oncogenesis via activation of the MAPK pathway [30]. Recent data also suggest that other molecular alterations may modulate cancer cell (including PDAC) susceptibility to MAPK inhibition: indeed, PTEN loss was shown to portend intrinsic resistance to MEK inhibitors and synergistic activity of combined MAPK/phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase (PI3K) pathway inhibition [34]; however, combined MAPK/PI3K inhibition did not prove effective in either cell line models of PDAC [35] or PDAC patients [36], presumably owing to the lack of PTEN alterations.

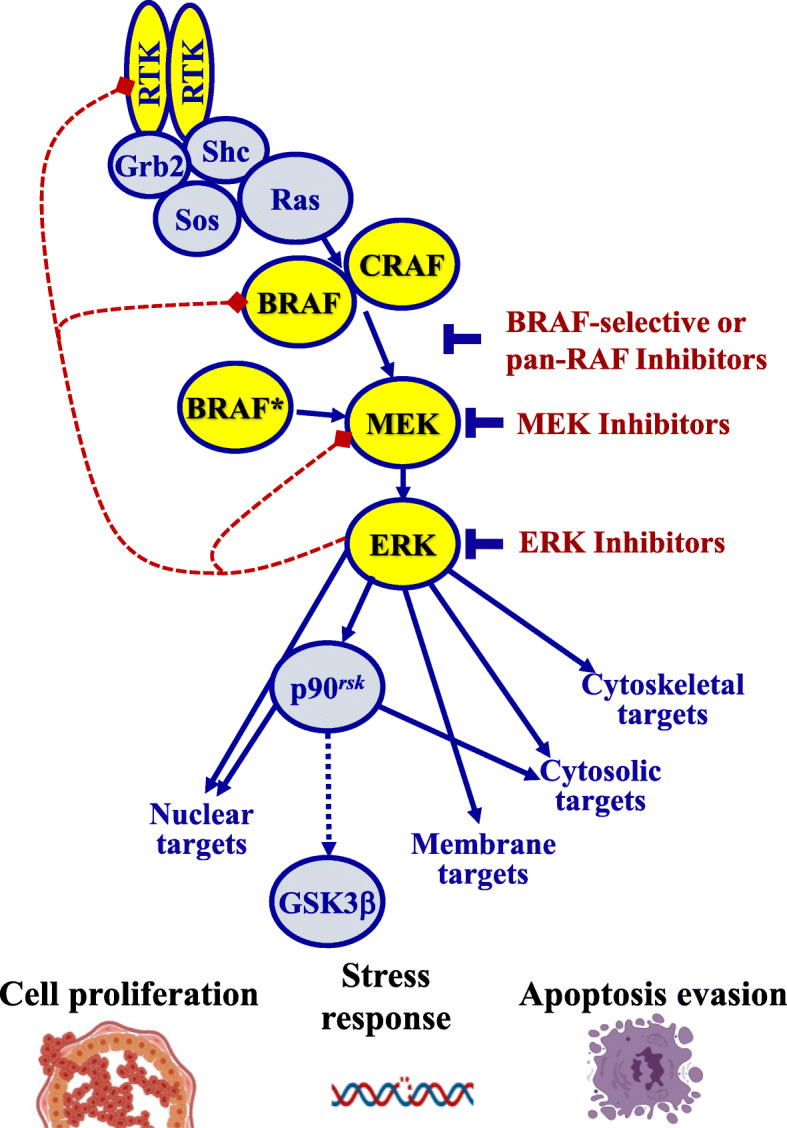

B-RAF is immediately downstream of RAS and triggers MAP2K1/MEK, which activates MAPK1/ERK2, important mediators of the MAPK pathway. Then, the activating signal is passed on by a chain of kinase reactions, overall establishing MAPK signaling pathway [30]. Consequently, activating mutations of KRAS and BRAF produce at last the activation of this pathway, which is crucial for pancreatic cancer (Fig. 2). Interestingly, MAPK kinases are classified into three classes based on their distinctive effectors: extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK), Jun amino-terminal kinases (JNK) and p38-mitogen-activated protein kinases (p38MAPK) [37]. Each class regulates distinct functions: ERK is involved in proliferation, JNK in apoptosis and differentiation and p38MAPK in stress responses [37]. To enact specific cell responses, activated MAPK kinases translocate into the nucleus, where, through phosphorylation of different transcription factors, they can directly modulate the expression of different genes [30, 38]. Additional mechanisms that may replace KRAS/BRAF function for RTK/RAS/MAPK activation included mutations or amplifications of GNAS, EGFR, ERBB2, MET, ERBB3 and FGFR2 [9].

Fig. 2.

A schematic representation of the MAPK pathway is here shown. As highlighted, B-RAF is an immediately downstream of RAS and triggers MAP 2 K1/MEK, which activates MAPK1/ERK2, important mediators of the entire MAPK pathway. The overall effects include block of apoptosis, stress response and cell proliferation

Regarding therapeutic approaches to MAPK pathway targeting, in addition to the above described MAPK inhibitors, some other interesting data come from a large, multicenter, non-randomized trial of 581 PDAC patients, as part of the so-called “Know Your Tumor” initiative [39]. In this cohort, wild-type KRAS tumors accounted for 8% of the whole PDAC cohort, and a significant proportion (24%) of these had alterations in other MAPK pathway effectors, including BRAF activating alterations. In this setting, patients who received molecular target therapy, including MAPK inhibitors and BRAF-targeted drugs, achieved an improved progression-free survival and median overall survival [38]. Other data regarding direct BRAF inhibitors come from a recent study, which reported a 6-months remission of a BRAF- mutant PDAC patient treated with the inhibitor dabrafenib [40]. Moreover, preclinical data indicate that even wt-BRAF might constitute a suitable therapeutic target in PDAC, taking advantage of the therapeutic synergism of “vertical” combination strategies simultaneously targeting BRAF and MEK along the same pathway, regardless of KRAS mutational status [41].

From the point of view of molecular pathology, an important consideration regards the specific BRAF mutation to be encountered in PDAC. Indeed, mutations that are the most common in other tumor types, including melanoma and thyroid carcinoma, are not frequently present in PDAC. Singhi and colleagues [11] reported typical V600E and V600K BRAF mutations in only about 1/5 of PDAC with BRAF alterations. This point requires the adoption of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies in clinical practice to guarantee in-depth analysis of the coding regions of BRAF, coupled with the possibility to investigate other BRAF alterations, such as the presence of fusion genes.

Microsatellite instability (MSI) / defective mismatch repair (dMMR)

Another genetic alteration enriched in KRAS wild-type PDAC is microsatellite instability (MSI)/defective mismatch repair (dMMR) [11, 42–45]. A recent study has definitively demonstrated that MSI/dMMR PDAC harbor KRAS mutations less frequently than conventional PDAC, reaching statistically significant values [42]. However, it should be acknowledged that about one third of MSI/dMMR PDAC can present KRAS mutations [43, 44]. Microsatellites are short, repetitive DNA sequences of 1–6 base pairs present throughout the genome, mostly in noncoding regions [35]. Their repetitive nature renders them very sensitive to DNA mismatching errors, which can occur during DNA replication or iatrogenic damage [45]. Cancers harboring a dMMR are very often hypermutated and typically accumulate mutations in microsatellites: this condition is termed MSI [45].

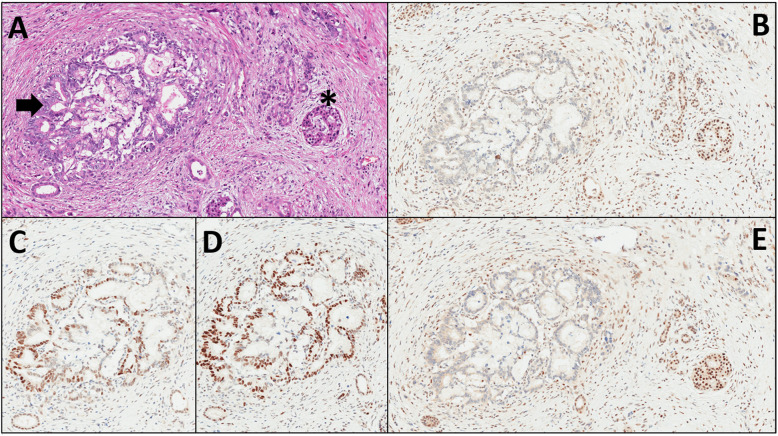

The MSI phenotype was first described in the familial cancer condition known as Lynch syndrome (LS), where the MMR genes MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 or PMS2 harbor germline mutations and portend marked susceptibility to develop several types of cancer, including PDAC [43]. MSI can be tested using immunohistochemistry (IHC) and molecular tests, including classic polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and next-generation sequencing (NGS) [45–47]. Immunohistochemical analysis is more reliable for cancers belonging to the spectrum of LS [43], where the loss of expression of the heterodimers MLH1-PMS2 and/or MSH2-MSH6 represent a very reliable surrogate of dMMR [44, 45]. For other cancer types, PCR or NGS approaches appear more robust for MSI/dMMR assessment and should be used instead of IHC. In PDAC, the use of IHC appears a reliable method (Fig. 3), although this cancer type does not represent one of the most common malignancies in LS patients [44, 45].

Fig. 3.

This is a classic example of a conventional pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) with microsatellite instability, assessed by immunohistochemistry. a An infiltrating PDAC gland is centrally located on the left (arrow), and a normal endocrine islet is on the right (asterisk). Hematoxylin-Eosin staining, original magnification X10. b Loss of expression of the MMR protein MLH1 with immunohistochemistry. The infiltrating PDAC gland is totally negative (loss of protein expression), and the same time the endocrine cells of the islet are positive, as well as lymphocytes, endothelial and stromal cells in the periphery (the expression of the MMR proteins in non-neoplastic cells is used as an internal control demonstrating the reliability of the immunohistochemical analysis). Original magnification X10. c, d Conserved expression of the MMR proteins MSH2 (c) and MSH6 (d). Original magnification X10. e Loss of expression of the MMR protein PMS2 with immunohistochemistry. The infiltrating gland is totally negative (loss of expression), and the same time the endocrine cells of the islet as well as lymphocytes, endothelial and stromal cells in the periphery are positive. Original magnification X10

MSI in PDAC has been described with variable frequencies, with a prevalence ranging approximatively from 0.1 to 7% in the most recent investigations on large cohorts of patients [30, 48–51]. However, a recent comprehensive seminal paper has established its prevalence in PDAC at around 1–2% [44]. Highest values of MSI prevalence have been reached in specific PDAC subtypes, such as medullary variant, mucinous/colloid variant and IPMN-derived carcinomas [40, 44, 51]. Among conventional PDAC, Humphris et al., who interrogated 385 pancreatic cancer genomes for mutational signatures inferring defects in DNA repair, identified MSI in 1% of tumors [48]. Along this line, Hu et al., using an NGS assay designed to perform targeted deep sequencing of cancer-associated genes, found a 0.8% MSI frequency in a cohort of 833 PDAC [50]. Although it is a rare condition, the new frontiers of immunotherapy have opened new important therapeutic opportunities for tumors with this molecular alteration. Indeed, because of the defective mismatch repair machinery, tumors with MSI are hypermutated neoplasms; this genetic alteration leads to the synthesis of several (up to 50 times more than microsatellite stable tumors) aberrant and potentially immunogenic neo-antigens by the tumor cells [52]. An important self-response to the presence of these neo-antigens is a diffuse infiltration of the tumor area by cytotoxic T-cell lymphocytes (CTLs) [52]. Recent studies have highlighted the concomitant expression of multiple active immune checkpoint markers, such as the Programmed Cell Death Protein 1 (PD-1) and its ligand PD-L1. Their interaction cause T cells functional exhaustion and unresponsiveness [53]. Based on this discovery, Le et al. evaluated in 2015 the clinical activity of pembrolizumab, an anti-PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor, in a cohort of metastatic colorectal and non-colorectal carcinoma patients with or without MSI [54]. However, no patient with PDAC was included in this study. The results of this phase 2 trial clearly showed that MSI status was able to predict clinical benefits from immune checkpoint blockade therapy with pembrolizumab [55, 56]. In 2017, the same group published the “KEYNOTE-158” trial, investigating PD-1 blockade efficacy in patients with advanced dMMR cancers across different tumor types, including also PDAC [57]. If initially the objective response rate was similar between colorectal versus other tumor subtypes, an update of the trial including a total of 22 MSI/dMMR PDAC patients, showed only 4 of 22 patients with objective responses, which represented the lowest objective response among the different cancers investigated [58]. These findings highlight the complex biology of PDAC and call for further investigations in this field.

Of interest, tumor mutational burden (TMB) is another important variable in this setting, since it has been strictly correlated to the response to immunotherapy. TMB is a value that represents the rate of mutations in a tumor, and is expressed as the number of mutations per megabase. In PDAC, a high TMB is a rare finding and very often occurs simultaneously with MSI [11, 47, 50]. New NGS approaches can provide simultaneously data on MSI and TMB, with potentially immediate consequences on therapeutic opportunities for these specific PDAC molecular subgroups.

From the point of view of molecular pathology, it is important to acknowledge that IHC, performed using the antibodies for all 4 MMR proteins (MLH1, PMS2, MSH2 and MSH6) represents a very reliable methodology to assess MSI in PDAC. However, in cases of doubtful IHC results, MSI/dMMR should be assessed with PCR-based MSI or NGS. In cases with limited tissue (e.g.: endoscopic/ultrasound guided fine needle biopsy), NGS should be adopted as the first choice, as highlighted by a recent study on this topic [44]. Due to the potential importance associated with a diagnosis of MSI/dMMR in the context of PDAC, including eligibility for immunotherapy trials, it is of primary importance that all methodologies for MSI/dMMR assessment follow standardized protocols (including all pre-analytical phases) and up to date recommendations [45].

Kinase fusion genes

The most important original report on this topic is a recent massive sequencing-based paper with a cohort of 3594 PDAC, where Singhi et al. showed that kinase fusion genes are one of the most frequent putative driver alterations in KRAS wild-type PDACs [11]. They found specific kinase fusions in FGFR2 (12 cases), RAF (7 cases), ALK (5 cases), RET (4 cases), MET (2 cases), NTRK1 (2 cases), ERBB4 (1 case) and FGFR3 (1 case), representing about 7.6% of genetic alterations of all KRAS wild-type PDAC. In the majority of fusion genes, a serine/threonine kinase or tyrosine kinase catalytic domain was fused to an oligomerization domain, which may represent a mutual mechanism of activation [11]. All these kinase fusions were mutually exclusive and, similar to BRAF, they were not present in PDACs with KRAS alterations [11].

Regarding the therapeutic approach to PDAC patients with kinase fusions, there are still limited data in the literature. Interestingly, a previous research identified 4 PDAC patients with ALK fusions; 3 of them showed stable disease with normalization of serum CA19-9 levels after treatment with an ALK inhibitor [59]. Notably, Pishvaian et al. recently described 2 PDAC patients with NTRK1 fusions; such patients were already metastatic at the time of diagnosis but showed partial responses to the specific targeted drug entrectinib [60]. Regarding BRAF and RAF fusions, these molecular alterations have not been described in PDAC but in another exocrine pancreatic cancer, which is acinar cell carcinoma [61]. Intragenic/in-frame deletions in BRAF represent other potential driver alterations in KRAS wild-type PDAC. Although also in this case there are limited data, Aguirre et al. reported a single PDAC patient with oncogenic BRAF deletion with response to the pathway inhibitor trametinib [62].

In the last few years, several studies have detected neuregulin 1 (NRG1) fusion genes across different cancer types, particularly in invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma (IMA) of the lung and PDAC. Moreover, NRG1 fusions have been detected with several fusion partners [63]. The NRG1 gene encodes for a member of the epidermal growth factor (EGF) family, which binds to ERBB3, thereby causing its heterodimerization with ERBB2. NRG1 gene fusions are generally in-frame and generate fusion proteins that maintain the extracellular EGF domain of NRG1 and the transmembrane domain of the rearrangement partner. Thus, the EGF domain of the fusion protein can constitutively bind to its partner and activate signaling through MAPK, PI3K-AKT, and NF-kB, increasing tumor proliferation and survival [63, 64]. In patients affected by PDAC, NRG1 fusions are detected only in KRAS wild-type tumors and usually in the absence of other concomitant driver gene mutations, suggesting that the rare NRG1 fusions act as an oncogenic driver in this tumor. In addition, some studies have demonstrated the actionability of NRG1 fusions in PDAC. Indeed, when patients affected by heavily pretreated PDAC carrying NRG1 fusion received matched therapy with afatinib, an irreversible ERBB1–4 inhibitor, clinical benefit and objective responses were documented [65, 66]. However, Drilon at al recently reported four patients affected by IMA of the lung with NRG1 fusion that did not respond to afatinib, but showed an extraordinary clinical response to treatment with a new monoclonal antibody targeting ERBB3 [67].

From a molecular pathology perspective, the necessity to identify fusion genes further highlights the importance of introducing NGS into clinical practice. For PDAC patients, this point represents an urgent need, at least for KRAS wild-type PDAC. The final pathology report for PDAC should integrate morphology with molecular pathology, following the model of a next-generation histopathologic diagnosis [68].

Clinical considerations and conclusions

Therapeutic management of pancreatic cancer remains an important clinical challenge and a clearly unmet medical need. With the notable exception of PDAC arising in the context of germline BRCA1/2 mutations [69], no effective targeted therapies have been developed for this deadly disease and no routine molecular pathology testing is currently indicated at diagnosis. Even worse, in the past 20 years we have witnessed the failure of an awfully long list of clinical trials testing intriguing and pre-clinically sound molecularly targeted agents. Among many methodological faults that prevented the successful transition of many agents/combinations from early phase trials to phase III documentation of efficacy and registration [70], the most striking finding is that out of 37 trials involving biological agents, only one employed a biomarker-based population enrichment strategy. Testing targeted drugs in unselected PDAC populations has not met with clinical success, leading to a largely avoidable waste of time, resources and, most importantly, patients’ lives. In addition, it may have led to the dismissal of agents/strategies with potential efficacy in specific populations of patients. This is the case, using an example relevant to the topic discussed in this review, for the addition of trametinib (a potent allosteric MEK inhibitor) to gemcitabine as first-line treatment of advanced PDAC patients [13]: while ineffective in the entire (unselected) trial population, it might have benefitted the small (n = 40) population of KRAS wild type patients, in whom the risk of death was reduced by approximately 40% by the addition of trametinib, although with results that did not reach statistical significance [13].

As discussed here, KRAS-wild type PDAC may represent a distinct molecular subtype of pancreatic cancer. The genetic hallmarks in this category are represented by the presence of an activated MAPK, of MSI/dMMR, and of kinase-fusion genes in variable proportions. Differently from conventional PDAC, if appropriately selected based on their individual genomic and molecular features, these special PDAC subtypes can be treated with specific therapeutic strategies (see Table 1 for a list of selected ongoing trials with agents targeting molecular aberrations that are enriched in KRAS wild type PDAC), representing an important step towards the establishment of precision oncology for patients with pancreatic cancer [71]. As exemplified by the recently reported “Know Your Tumor” initiative experience in PDAC [72], only a minority of patients might currently benefit from extended molecular profiling (46 out of 1223–4% - profiled patients received matched therapy in their experience). That said, the evidences reviewed and discussed on these topics may call for a complementation of PDAC histological diagnosis with routine determination of KRAS mutational status, followed by comprehensive molecular profiling of KRAS wild-type cases.

Table 1.

Selected trials targeting molecular aberrations enriched in KRAS-wt PDAC

| Target | Tested drug | Phase trial | Population | Primary Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALK | ceritinib |

Phase I |

Dose escalation (ALK negative) and expansion cohort (ALK positive) in advanced solid tumors in combination with standard chemotherapy Expansion cohort 2E: advanced pancreatic cancer ALK positive in combination with gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel |

MTD, RP2D |

| BRAF |

binimetinib + encorafenib |

Phase II |

Pancreatic cancer BRAF mutated (V600E) after progression disease to at least one line of chemotherapy | ORR |

| MEK | cobimetinib or olaparib trametinib + hydroxychloroquine |

Early Phase 1 Phase I |

Diagnosis of pancreatic cancer (resectable, borderline resectable, or advanced) are eligible Participants may be treatment naive or have received prior therapy Arm I: cobimetinib Arm II: Olaparib Pretreated Advanced Pancreatic Cancer |

Assess the feasibility of collecting tumor tissue for biomarker evaluation prior to and after window therapy with either cobimetinib or olaparib DLT, RP2D |

| RET |

selpercatinib sunitinib |

EAP Phase IV |

Solid tumors RET activated RET fusion positive, FGFR2 fusion/FGFR mutation refractory solid tumor |

- PFS |

| NTRK/ROS1 | entrectinib |

Phase II (STARTRK2) |

Solid tumors with NTRK1/2/3, ROS1, ALK gene rearrangments | ORR |

| NTRK | VDM-928 |

Phase I |

Expansion phase: Solid tumors with NTRK1 gene fusions or amplification |

AEs |

| NTRK/ROS1 | DS-6051b |

Phase I |

advanced solid tumors harboring ROS1 or NTRK1, NTRK2, or NTRK3 rearrangement | DLT |

| NRG1 |

zenocutuzumab (MCLA-128) |

Phase I/II |

Dose escalation (NRG1 negative) and dose expansion (NRG1 positive) in advanced solid tumors Dose expansion Group G: pancreatic cancer with NRG1 fusion |

AEs / SAEs ORR DOR Biomarkers analysis |

| HER2 | A116 |

Phase I/II |

Relapsed/Refractory Cancers Expressing HER2 Antigen or Having Amplified HER2 Gene |

Phase I: MTD Phase II: ORR |

| ACE1702 |

Phase I NCT0431975 |

Advanced or Metastatic HER2-expressing Solid Tumors |

Safety, DLT, MTD, RP2D |

|

| T-DXd |

Phase2 |

cohort six: patient with no satisfactory alternative treatment option affected by advanced pancreatic cancer with HER2 amplification | ORR | |

| afatinib + capecitabine |

Phase I/IB |

Phase I: pretreated solid tumor Phase IB: pretreated advanced pancreatic and biliary tract cancer |

DLT, MTD, RP2D |

|

| ERK | LY3214996 +/− hydroxychloroquine |

Phase II |

Advanced pancreatic cancer | DCR |

| ulixertinib/Palbociclib |

Phase I |

Dose escalation cohorts: histologically confirmed advanced refractory solid tumor | MTD | |

| Expansion: metastatic pancreatic cancer patients | OS | |||

| MSI | dostarlimab |

Phase I |

Part 2B: Cohort F non-endometrial dMMR/MSI-H or POLE-Mutated solid tumors, that have progressed following up to 2 prior lines of systemic for advanced disease | AE |

| FGFR | pemigatinib |

Phase II |

Cohort A Previously Treated Locally Advanced/Metastatic or Surgically Unresectable Solid Tumor Malignancies Harboring Activating FGFR 1–3 fusion | ORR |

| infigratinib |

Phase II |

Cohort 1–2: solid tumor harboring FGFR1–3 fusion/translocation who have progressed on or are intolerant to standard of care | ORR | |

| erdafitinib |

Phase II |

Pretreated advanced solid tumor malignancy FGFR mutation or gene fusion | ORR | |

| debio 1347 |

Phase II |

Pretreated Solid Tumors Harboring a Fusion of FGFR1, FGFR2 or FGFR3 | ORR |

MTD maximum tolerated dose, RPD2 recommended phase II dose, ORR objective response rate, DLT dose-limiting toxicity, PFS progression free survival, AEs adverse events, SAEs serious adverse events, DOR duration of response, OS overall survival

Acknowledgements

None to be declared.

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication

Not applicable (review).

Abbreviations

- PDAC

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- IMA

invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma

- JNK

Jun amino-terminal kinase

- p38MAPK

p38-mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MSI

microsatellite instability

- dMMR

defective mismatch repair

- MMR

mismatch repair

- LS

Lynch syndrome

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- NGS

next-generation sequencing

- CTLs

cytotoxic T-cell lymphocytes

- PD-1

programmed cell death protein 1

- PD-L1

programmed cell death protein 1 – ligand

- TMB

tumor mutational burden

Authors’ contributions

CL, RTL, MM, AS: study conception and design; CL, GP, PM: literature review; all authors: data interpretation and discussion; CL, GP, PM, RTL, MM, AS: manuscript writing; all authors: final editing and approval of the manuscript in its present form.

Funding

This study is supported by Associazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC 5 × 1000 n. 12182) and Fondazione Cariverona: Oncology Biobank Project “Antonio Schiavi” (prot. 203885/2017).

Availability of data and materials

All data presented in this review are totally available and present in the text.

Competing interests

Claudio Luchini is a paid expert-consultant on microsatellite instability for BioScience Communications (New York, NY, USA). The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rahib L, Smith BD, Aizenberg R, Rosenzweig AB, Fleshman JM, Matrisian LM. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: the unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res. 2014;74:2913–2921. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamisawa T, Wood LD, Itoi T, Takaori K. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet. 2016;388:73–85. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00141-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luchini C, Capelli P, Scarpa A. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and its variants. Surg Pathol Clin. 2016;9:547–560. doi: 10.1016/j.path.2016.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.I numeri del cancro in Italia 2019. https://www.aiom.it/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/2019_Numeri_Cancro-operatori-web.pdf. Accessed 11 May 2020.

- 7.Herbst B, Zheng L. Precision medicine in pancreatic cancer: treating every patient as an exception. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4:805–810. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30175-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waddell N, Pajic M, Patch AM, Chang DK, Kassahn KS, Bailey P, et al. Whole genomes redefine the mutational landscape of pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2015;518:495–501. doi: 10.1038/nature14169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bailey P, Chang DK, Nones K, Johns AL, Patch AM, Gingras MC, et al. Genomic analyses identify molecular subtypes of pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2016;531:47–52. doi: 10.1038/nature16965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pylayeva-Gupta Y, Grabocka E, Bar-Sagi D. RAS oncogenes: weaving a tumorigenic web. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:761–774. doi: 10.1038/nrc3106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singhi AD, George B, Greenbowe JR, Chung J, Suh J, Maitra A, et al. Real-time targeted genome profile analysis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas identifies genetic alterations that might be targeted with existing drugs or used as biomarkers. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:2242–2253. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luchini C, Veronese N, Nottegar A, Cappelletti V, Daidone MG, Smith L, Parris C, Brosens LAA, Caruso MG, Cheng L, Wolfgang CL, Wood LD, MilellaM, Salvia R, Scarpa A. Liquid biopsy as surrogate for tissue for molecular profiling in pancreatic cancer: A meta-analysis towards precision medicine. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11:1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Infante JR, Somer BG, Park JO, Li CP, Scheulen ME, Kasubhai SM, et al. A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of trametinib, an oral MEK inhibitor, in combination with gemcitabine for patients with untreated metastatic adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:2072–2081. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2014.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Cutsem E, Hidalgo M, Canon JL, Macarulla T, Bazin I, Poddubskaya E, et al. Phase I/II trial of pimasertib plus gemcitabine in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. Int J Cancer. 2018;143:2053–2064. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Laethem JL, Riess H, Jassem J, Haas M, Martens UM, Weekes C, et al. Phase I/II study of refametinib (BAY 86–9766) in combination with gemcitabine in advanced pancreatic cancer. Target Oncol. 2017;12:97–109. doi: 10.1007/s11523-016-0469-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bodoky G, Timcheva C, Spigel DR, La Stella PJ, Ciuleanu TE, Pover G, et al. A phase II open-label randomized study to assess the efficacy and safety of selumetinib (AZD6244 [ARRY-142886]) versus capecitabine in patients with advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer who have failed first-line gemcitabine therapy. Investig New Drugs. 2012;30:1216–1223. doi: 10.1007/s10637-011-9687-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dueland S, Valle JW, Bell K, Faluyi O, Staiger H, Gjertsen TJ, et al. TG01/GM-CSF and adjuvant gemcitabine in patients with resected RAS-mutant adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:v227–v228. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx369.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eriksen JA, Gladhaug IP, Rosseland A, Risberg Handeland K, Buanes T. An observational clinical study with RAS peptide vaccine TG01 evaluating immune response, safety and overall survival in patients with non-resectable pancreatic cancer. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:v409–v410. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx376.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richards D, Muscarella P, Bekaii-Saab T, Wilfong L, Rosemurgy A, Ross S, et al. A phase 2 adjuvant trial of GI-4000 plus gemcitabine vs. gemcitabine alone in ras+ patients with resected pancreas cancer: R1 subgroup analysis. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:iv5. doi: 10.1016/S0923-7534(19)66467-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weden S, Klemp M, Gladhaug IP, Moller M, Eriksen JA, Gaudernack G, et al. Long term follow-up of patients with resected pancreatic cancer following vaccination against mutant K-ras. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:1120–1128. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh RR, Goldberg J, Varghese AM, Yu KH, Park W, O'Reilly EM. Genomic profiling in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and a pathway towards therapy individualization: a scoping review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2019;75:27–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2019.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laheru D, Shah P, Rajeshkumar NV, McAllister F, Taylor G, Goldsweig H, et al. Integrated preclinical and clinical development of S-trans, trans-Farnesylthiosalicylic acid (FTS, Salirasib) in pancreatic cancer. Investig New Drugs. 2012;30:2391–2399. doi: 10.1007/s10637-012-9818-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Cutsem E, van de Velde H, Karasek P, Oettle H, Vervenne WL, Szawlowski A, et al. Phase III trial of gemcitabine plus tipifarnib compared with gemcitabine plus placebo in advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1430–1438. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.10.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yan Z, Ohuchida K, Fei S, Zheng B, Guan W, Feng H, et al. Inhibition of ERK1/2 in cancer-associated pancreatic stellate cells suppresses cancer-stromal interaction and metastasis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2019;38:221. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1226-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun Y, Peng W, He W, Luo M, Chang G, Shen J, et al. Transgelin-2 is a novel target of KRAS-ERK signaling involved in the development of pancreatic cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2018;37:166. doi: 10.1186/s13046-018-0818-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waters AM, Der CJ. KRAS: the critical driver and therapeutic target for pancreatic cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2018;8:a031435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Kim ST, Lim DH, Jang KT, Lim T, Lee J, Choi YL, et al. Impact of KRAS mutations on clinical outcomes in pancreatic cancer patients treated with first-line gemcitabine-based chemotherapy. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10:1993–1999. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Windon AL, Loaiza-Bonilla A, Jensen CE, Randall M, Morrissette JJD, Shroff SG. A KRAS wild type mutational status confers a survival advantage in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2018;9:1–10. doi: 10.21037/jgo.2017.10.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mottini C, Tomihara H, Carrella D, Lamolinara A, Iezzi M, Huang JK, et al. Predictive signatures inform the effective repurposing of Decitabine to treat KRAS-dependent pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 2019;79:5612–5625. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-0187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Furukawa T. Impacts of activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in pancreatic cancer. Front Oncol. 2015;5:23. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2015.00023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thatcher JD. The Ras-MAPK signal transduction pathway. Sci Signal. 2010;3:tr1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Gibbs JB, Sigal IS, Poe M, Scolnick EM. Intrinsic GTPase activity distinguishes normal and oncogenic ras p21 molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81:5704–5708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.18.5704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, Stephens P, Edkins S, Clegg S, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 2002;417:949–954. doi: 10.1038/nature00766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Milella M, Falcone I, Conciatori F, Matteoni S, Sacconi A, De Luca T, et al. PTEN status is a crucial determinant of the functional outcome of combined MEK and mTOR inhibition in cancer. Sci Rep. 2017;7:43013. doi: 10.1038/srep43013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ciuffreda L, Del Curatolo A, Falcone I, Conciatori F, Bazzichetto C, Cognetti F, et al. Lack of growth inhibitory synergism with combined MAPK/PI3K inhibition in preclinical models of pancreatic cancer. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:2896–2898. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chung V, McDonough S, Philip PA, Cardin D, Wang-Gillam A, Hui L, et al. Effect of Selumetinib and MK-2206 vs Oxaliplatin and fluorouracil in patients with metastatic pancreatic Cancer after prior therapy: SWOG S1115 study randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:516–522. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson GL, Lapadat R. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways mediated by ERK, JNK, and p38 protein kinases. Science. 2002;298:1911–1912. doi: 10.1126/science.1072682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brunet A, Roux D, Lenormand P, Dowd S, Keyse S, Pouyssegur J. Nuclear translocation of p42/p44 mitogen activated protein kinase is required for growth factor-induced gene expression and cell cycle entry. EMBO J. 1999;18:664–674. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.3.664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pishvaian MJ, Bender RJ, Halverson D, Rahib L, Hendifar AE, Mikhail S, et al. Molecular profiling of patients with pancreatic cancer: initial results from the know your tumor initiative. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24:5018–5027. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-0531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wrzeszczynski KO, Rahman S, Frank MO, Arora K, Shah M, Geiger H, Felice V, Manaa D, Dikoglu E, Khaira D, Chimpiri AR, Michelini VV, JobanputraV, Darnell RB, Powers S, Choi M. Identification of targetable BRAF ΔN486_P490 variant by whole-genome sequencing leading to dabrafenib-induced remission of a BRAF-mutant pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud. 2019;5:a004424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Del Curatolo A, Conciatori F, Cesta Incani U, Bazzichetto C, Falcone I, Corbo V, et al. Therapeutic potential of combined BRAF/MEK blockade in BRAF-wild type preclinical tumor models. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2018;37:140. doi: 10.1186/s13046-018-0820-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilentz RE, Goggins M, Redston M, Marcus VA, Adsay NV, Sohn TA, et al. Genetic, immunohistochemical, and clinical features of medullary carcinoma of the pancreas: a newly described and characterized entity. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:1641–1651. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65035-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lupinacci RM, Bachet JB, André T, Duval A, Svrcek M. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma harboring microsatellite instability / DNA mismatch repair deficiency. Towards personalized medicine. Surg Oncol. 2019;28:121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2018.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Luchini C, Brosens LA, Wood LD, Chatterjee D, Shin J, Sciammarella C, et al. Comprehensive characterization of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma with microsatellite instability: histology, molecular pathology and clinical implications, gut. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Luchini C, Bibeau F, Ligtenberg MJL, Singh N, Nottegar A, Bosse T, et al. ESMO recommendations on microsatellite instability testing for immunotherapy in cancer, and its relationship with PD-1/PD-L1 expression and tumour mutational burden: a systematic review-based approach. Ann Oncol. 2019;30:1232–1243. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Middha S, Zhang L, Nafa K, Jayakumaran G, Wong D, Kim HR, Sadowska J, Berger MF, Delair DF, Shia J, Stadler Z, Klimstra DS, Ladanyi M, Zehir A, Hechtman JF. Reliable pan-cancer microsatellite instability assessment by using targeted next-generation sequencing data. JCO Precis Oncol. 2017;2017:PO.17.00084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Salipante SJ, Scroggins SM, Hampel HL, Turner EH, Pritchard CC. Microsatellite instability detection by next generation sequencing. Clin Chem. 2014;60:1192–1199. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2014.223677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Humphris JL, Patch AM, Nones K, Bailey PJ, Johns AL, McKay S, et al. Hypermutation in pancreatic Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:68–74. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.09.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Salem ME, Puccini A, Grothey A, Raghavan D, Goldberg RM, Xiu J, et al. Landscape of tumor mutation load, mismatch repair deficiency, and PD-L1 expression in a large patient cohort of gastrointestinal cancers. Mol Cancer Res. 2018;16:805–812. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-17-0735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hu ZI, Shia J, Stadler ZK, Varghese AM, Capanu M, Salo-Mullen E, et al. Evaluating mismatch repair deficiency in pancreatic adenocarcinoma: challenges and recommendations. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24:1326–1336. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-3099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lupinacci RM, Goloudina A, Buhard O, Bachet JB, Maréchal R, Demetter P, et al. Prevalence of microsatellite instability in Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:1061–1065. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lothe RA, Peltomaki P, Meling GI, Aaltonen LA, Nyström-Lahti M, Pylkkänen L, et al. Genomic instability in colorectal cancer: relationship to clinicopathological variables and family history. Cancer Res. 1993;53:5849–5852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Llosa NJ, Cruise M, Tam A, Wicks EC, Hechenbleikner EM, Taube JM, et al. The vigorous immune microenvironment of microsatellite instable colon cancer is balanced by multiple counter-inhibitory checkpoints. Cancer Discov. 2015;5:43–51. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, Bartlett BR, Kemberling H, Eyring AD, et al. PD-1 blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2509–2520. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQ, Hwu WJ, Topalian SL, Hwu P, et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2455–2465. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Royal RE, Levy C, Turner K, Mathur A, Hughes M, Kammula US, et al. Phase 2 trial of single agent Ipilimumab (anti-CTLA-4) for locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Immunother. 2010;33:828–833. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181eec14c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Le DT, Durham JN, Smith KN, Wang H, Bartlett BR, Aulakh LK, et al. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science. 2017;357:409–413. doi: 10.1126/science.aan6733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marabelle A, Le DT, Ascierto PA, Di Giacomo AM, De Jesus-Acosta A, Delord JP, et al. Efficacy of Pembrolizumab in patients with noncolorectal high microsatellite instability/mismatch repair-deficient Cancer: results from the phase II KEYNOTE-158 study. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:1–10. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Singhi AD, Ali SM, Lacy J, Hendifar A, Nguyen K, Koo J, et al. Identification of targetable ALK rearrangements in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2017;15:555–562. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pishvaian MJ, Rolfo CD, Liu SV, Multani PS, Maneval EC, Garrido-Laguna I. Clinical benefit of entrectinib for patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer who harbor NTRK and ROS1 fusions. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(4_suppl):521.

- 61.Chmielecki J, Hutchinson KE, Frampton GM, Chalmers ZR, Johnson A, Shi C, et al. Comprehensive genomic profiling of pancreatic acinar cell carcinomas identifies recurrent RAF fusions and frequent inactivation of DNA repair genes. Cancer Discov. 2014;4:1398–1405. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Aguirre AJ, Nowak JA, Camarda ND, Moffitt RA, Ghazani AA, Hazar-Rethinam M, et al. Real-time genomic characterization of advanced pancreatic cancer to enable precision medicine. Cancer Discov. 2018;8:1096–1111. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-0275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jonna S, Feldman RA, Swensen J, Gatalica Z, Korn WM, Borghaei H, et al. Detection of NRG1 gene fusions in solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:4966–4972. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-0160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yarden Y, Pines G. The ERBB network: at last, cancer therapy meets systems biology. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:553–563. doi: 10.1038/nrc3309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jones MR, Williamson LM, Topham JT, Lee MK, Goytain A, Ho J, et al. NRG1 gene fusions are recurrent, clinically actionable gene rearrangements in KRAS wild-type pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:4674–4681. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Heining C, Horak P, Uhrig S, Codo PL, Klink B, Hutter B, et al. NRG1 fusions in KRAS wild-type pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2018;8:1087–1095. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Drilon A, Somwar R, Mangatt BP, Edgren H, Desmeules P, Ruusulehto A, et al. Response to ERBB3-directed targeted therapy in NRG1-rearranged cancers. Cancer Discov. 2018;8:686–695. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Luchini C, Capelli P, Fassan M, Simbolo M, Mafficini A, Pedica F, et al. Next-generation histopathologic diagnosis: a lesson from a hepatic carcinosarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:e63–e66. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.5855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Golan T, Hammel P, Reni M, Van Cutsem E, Macarulla T, Hall MJ, et al. Maintenance Olaparib for Germline BRCA-mutated metastatic pancreatic Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:317–327. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1903387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tang M, Chen J, Goldstein D, Links M, Lord S, Marschner I, et al. Evaluation of phase II trial Design in Advanced Pancreatic Cancer. Pancreas. 2019;48:1274–1284. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000001429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Di Martino MT, Meschini S, Scotlandi K, Riganti C, De Smaele E, Zazzeroni F, et al. From single gene analysis to single cell profiling: a new era for precision medicine. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2020;39:48. doi: 10.1186/s13046-020-01549-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pishvaian MJ, Blais EM, Brody JR, Lyons E, DeArbeloa P, Hendifar A, et al. Overall survival in patients with pancreatic cancer receiving matched therapies following molecular profiling: a retrospective analysis of the know your tumor registry trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:508–518. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30074-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data presented in this review are totally available and present in the text.