ABSTRACT

Trauma can profoundly affect the sense of self, where both cognitive and somatic disturbances to the sense of self are reported clinically by individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). These disturbances are captured eloquently by clinical accounts, such as, ‘I do not know myself anymore,’ ‘I will never be able to experience normal emotions again,’ and, ‘I feel dead inside.’ Self-related thoughts and experiences are represented neurobiologically by a large-scale, cortical network located along the brain’s mid-line and referred to as the default mode network (DMN). Recruited predominantly during rest in healthy participants, the DMN is also active during self-referential and autobiographical memory processing – processes which, collectively, are thought to provide the foundation for a stable sense of self that persists across time and may be available for conscious access. In participants with PTSD, however, the DMN shows substantially reduced resting-state functional connectivity as compared to healthy individuals, with greater reductions associated with heightened PTSD symptom severity. Critically, individuals with PTSD describe frequently that their traumatic experiences have become intimately linked to their perceived sense of self, a perception which may be mediated, in part, by alterations in the DMN. Accordingly, identification of alterations in the functional connectivity of the DMN during rest, and during subliminal, trauma-related stimulus conditions, has the potential to offer critical insight into the dynamic interplay between trauma- and self-related processing in PTSD. Here, we discuss DMN-related alterations during these conditions, pointing further towards the clinical significance of these findings in relation to past- and present-centred therapies for the treatment of PTSD.

KEYWORDS: default mode network, PTSD, trauma, sense of self, posterior cingulate cortex, medial prefrontal cortex, somatic, present-centred treatment, past-centred, treatment, MDMA

HIGHLIGHTS: • Trauma may impact significantly an individual's sense of self.• The default mode network is thought to confer a stable sense of self.• We discuss alterations in connectivity in this network in PTSD and their clinical significance.

Abstract

El trauma puede afectar profundamente el sentido del Yo, donde tanto perturbaciones cognitivas como somáticas del sentido del Yo han sido reportadas clínicamente por individuos con trastorno de estrés postraumático (TEPT). Estas perturbaciones son capturadas de forma elocuente por relatos clínicos como ‘ya no me conozco a mí mismo(a)’, ‘nunca más volveré a ser capaz de experimentar emociones normales’, y ‘me siento muerto(a) por dentro’. Los pensamientos y experiencias relacionadas con el Yo se representan neurobiológicamente por una red cortical a gran escala, localizada entre la línea media del cerebro, conocida como la red neuronal por defecto (DMN por sus siglas en ingles). Reclutada predominantemente durante el reposo en pacientes sanos, la DMN también está activa durante el procesamiento de memorias autobiográficas y auto-referentes, procesos a los que comúnmente se les atribuye la función de proveer la base para un sentido estable del Yo, que persiste a lo largo del tiempo y puede estar disponible para el acceso consciente. En participantes con TEPT, sin embargo, la DMN muestra conectividad de reposo disminuida comparada con la de individuos sanos, con mayores disminuciones asociadas con mayor severidad en síntomas de TEPT. De manera crítica, individuos con TEPT describen con frecuencia que sus experiencias traumáticas se han vuelto íntimamente relacionadas con su percepción del sentido del Yo, que puede estar mediada, en parte, por alteraciones en la DMN. Por lo tanto, la identificación de alteraciones en la conectividad funcional de la DMN en reposo, y durante condiciones subliminales y estímulos relacionados con el trauma, tiene el potencial de ofrecer una introspección crítica hacia la interacción dinámica entre el trauma y el procesamiento relacionado al self en el TEPT. En este estudio, discutimos las alteraciones relacionadas con la DMN durante estas condiciones, apuntando hacia la significancia clínica de estos hallazgos en relación a las terapias centradas en el presente y el pasado, para el tratamiento del TEPT.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Red Neuronal Por Defecto, TEPT, Trauma, Sentido del Yo, Corteza Cingulada Posterior, Corteza Prefrontal Medial, Somático, Terapia Centrada en el Presente, Terapia Centrada en el Pasado, MDMA

摘要: 创伤会深刻影响自我意识, 创伤后应激障碍 (PTSD) 患者临床上会报告自我意识的认知和躯体障碍。这些障碍可被临床报告充分捕捉到, 例如‘我不再了解自己”, “我将再也无法体验正常的情绪”和“我内心生不如死”。自我相关想法和体验在神经生物学上由位于大脑中线的大面积皮层网络呈现, 被称为默认模式网络 (DMN) 。 DMN主要是在健康参与者静息状态下收集的, 在自我参照和自传体记忆处理过程中也很活跃, 而这些过程共同被认为可为跨时间持续存在的自我意识提供稳定的基础, 并且可用于有意识的访问。但是, 相较于健康个体, 患有 PTSD 的参与者的 DMN 表现出明显降低的静息态功能连接, 越高的 PTSD 症状严重程度降低程度更大。至关重要的是, PTSD 患者经常描述他们的创伤经历已经与他们的感知自我意识紧密联系在一起, 这种感知可能被 DMN 的改变部分中介。因此, 识别 DMN 在静息态以及阈下创伤相关刺激条件下功能连接的改变, 有可能为 PTSD 中创伤和自我相关加工之间动态相互作用提供关键见解。在这里, 我们讨论了在这些情况下与 DMN 相关的改变, 进一步指出了这些发现与关注过去和关注当下的 PTSD 治疗相关的临床意义。

关键词: 默认模式网络, PTSD, 创伤, 自我意识, 后扣带回皮层, 前额叶内侧皮层, 躯体, 关注当下的治疗, 关注过去, 治疗, MDMA

1. The sense of self in the aftermath of trauma

Trauma can profoundly affect the sense of self (Schore, 2003) – leaving a lasting imprint on both the cognitive and the somatic domains of an individual’s sense of self (Lanius, Frewen, Tursich, Jetly, & McKinnon, 2015; for a review, see Frewen et al., 2008, 2020). Cognitively, individuals who have experienced trauma are often tormented by thoughts that reflect intensely negative core beliefs about themselves, which can include, ‘I will never be able to feel normal emotions again,’ ‘I feel like an object, not like a person,’ ‘I do not know myself anymore,’ or, ‘I have permanently changed for the worse’ (Cox, Resnick, & Kilpatrick, 2014; Foa, Tolin, Ehlers, Clark, & Orsillo, 1999). Somatically, recent research points increasingly towards the notion that trauma can leave a lasting physical representation, where lower back pain, general muscle aches and pains, flatulence/burping, or feeling as though your bowel movement has not finished have been identified as somatic disturbances that significantly perturb the sense of self (Graham, Searle, Van Hooff, Lawrence-Wood, & McFarlane, 2019). Here, Graham et al. (2019) found that two thirds of cases of military-related posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are missed when a PTSD checklist for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5; APA, 2013) (i.e. PCL-5) served as the only assessment tool; these cases are, however, captured when physical symptoms are considered in conjunction with the PCL-5. Moreover, participants with PTSD report somatically-based alterations in relation to self-experience, including feelings of disembodiment and related identity disturbances, revealed by reports like, ‘I feel dead inside,’ ‘I feel as if I am outside my body,’ ‘I feel like my body does not belong to me,’ or, ‘I feel like there is no boundary around my body’ (Bernstein & Putnam, 1986; Foa et al., 1999; Briere & Runtz, 2002; Frewen & Lanius, 2015; for a review, see Frewen et al., 2008, 2020). These reports underscore the vulnerability the sense of self has in the aftermath of trauma, where both cognitive and somatic disturbances to the sense of self are thought to reflect remnants of the traumatic past among individuals with PTSD.

2. Neural underpinnings of the sense of self: the default mode network

A wide body of evidence suggests that self-referential processes, as well as past- and future-related autobiographical memory processing, are facilitated by a large-scale, intrinsic network known as the default mode network (DMN) (Greicius, Krasnow, Reiss, & Menon, 2003; for a review, see Raichle, 2015). Self-referential processes define the various self-related or social-cognitive functions that allow us to gain insight and to draw inferences related to our own mental and physical conditions, as well as to mentalize these alike conditions in others (Greicius et al., 2003). Although the DMN is recruited predominantly during rest, it is also active during internally-directed cognitive processes (for a review, see Raichle, 2015). Collectively, these DMN-mediated processes are thought to provide the foundation for a continued experience of the self across time, occasionally referred to as ‘autonoetic consciousness’ (Fransson, 2005; Piolino et al., 2006; Tulving, 1985), where self-relevant information and events associate to produce our sense of self (Conway & Pleydell-Pearce, 2000; Levine, Svoboda, Hay, Winocur, & Moscovitch, 2002).

The DMN is composed primarily by cortical regions located across the brain’s mid-line, including the posterior cingulate cortex, the precuneus, and the medial prefrontal cortex (Spreng, Mar, & Kim, 2009; Greicius et al., 2003; Buckner, Andrews-Hanna, & Schacter, 2008; for a review, see Qin & Northoff, 2011). These DMN-related cortices contribute variously to self-related processes. Whereas the posterior cingulate cortex and the precuneus are associated more strongly with our experience of having an embodied self that exists in space, the medial prefrontal cortex is associated more strongly with our awareness of thoughts and emotions related to the self (for a review, Qin & Northoff, 2011). Critically, the DMN displays widespread functional alterations in individuals with PTSD during rest (Akiki et al., 2018; Brown et al., 2014; for a review, see Moore & Zoellner, 2007; St Jacques, Kragel, & Rubin, 2013; Nazarov et al., 2014, 2015; Wang et al., 2016; Koch et al., 2016; Barredo et al., 2018; Akiki, Averill, & Abdallah, 2017) and during trauma-related stimulus conditions (Terpou et al., 2019a; for a review, see St Jacques et al., 2013; Freeman, Hart, Kimbrell, & Ross, 2009), where these alterations are likely to mediate the clinical disturbances underlying self-related processes observed in PTSD.

3. The default mode network at rest in the aftermath of trauma

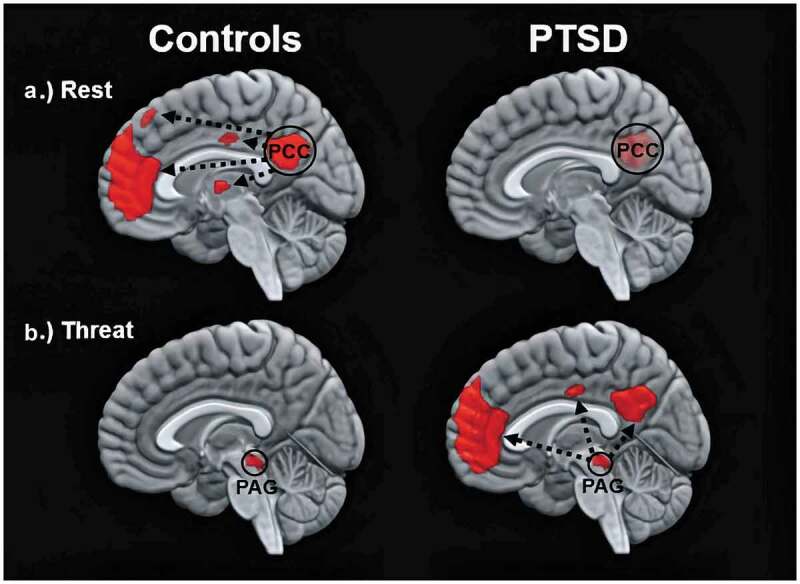

Altered functionality across large-scale, resting-state networks can be evaluated using functional connectivity – an endeavour that has proven vital to identifying the neural correlates underlying PTSD. Functional connectivity estimates the degree to which a particular brain region (i.e. seed) reveals neuronal coupling across the brain by correlating the spontaneous low-frequency activity of the seed across the remaining whole-brain voxels (Friston, 1994). In PTSD, the DMN displays reduced functional connectivity during rest as compared to healthy controls (Figure 1(a)) (Bluhm et al., 2009; Sripada et al., 2012). In particular, reduced resting-state functional connectivity has been observed for each DMN-related hub as exhibited with other DMN-related brain regions in participants with PTSD as compared to healthy individuals (posterior cingulate cortex: Lanius et al., 2010; Wu et al., 2011; Sripada et al., 2012; Miller et al., 2017; precuneus: Bluhm et al., 2009; Di et al., 2012; Reuveni et al., 2016; medial prefrontal cortex: DiGangi et al., 2016). Reduced functional connectivity between DMN hubs and the DMN more generally points strongly towards a diminished coherence across the network, where stronger reductions in resting-state functional connectivity across the DMN are associated with greater PTSD symptom severity (Bluhm et al., 2009; Di et al., 2012; Shang et al., 2014; Sripada et al., 2012). Critically, reduced resting-state functional connectivity across the DMN among participants with PTSD has been replicated by multiple research groups and across varying trauma exposures (combat exposure: DiGangi et al., 2016; Reuveni et al., 2016; King et al., 2016; Kennis, Van Rooij, Van Den Heuvel, Kahn, & Geuze, 2016; interpersonal trauma: Lanius et al., 2010; Bluhm et al., 2009; acute trauma: Wu et al., 2011; Patriat, Birn, Keding, & Herringa, 2016; Lu et al., 2017).

Figure 1.

Images show the functional connectivity of the DMN in healthy controls (left) and in participants with PTSD (right) under different conditions. Top and bottom images depict within-group patterns in functional connectivity during rest and during trauma-related stimulus processing, respectively. Whereas resting-state functional connectivity is depicted in relation to the time series of the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), trauma-related functional connectivity is depicted in relation to the time series of the periaqueductal grey (PAG). Figure 1 is an adaptation from two previous findings, where resting-state and threat-related functional connectivity are related to results by Bluhm et al. (2009) and Terpou et al. (2019a), respectively

Although PTSD symptoms can emerge following trauma(s) that are experienced well into adulthood, Daniels, Frewen, McKinnon, and Lanius (2011) have proposed that early-life trauma(s) may interfere particularly with the developmental trajectory of the DMN – beginning in childhood and maturing well into adolescence and early adulthood (Supekar et al., 2010; Sripada, Swain, Evans, Welsh, & Liberzon, 2014; Sherman et al., 2014; for a review, see Fair et al., 2008). Specifically, resting-state functional connectivity between the posterior cingulate cortex and the medial prefrontal cortex is thought to play an important role in the development of self-related and social-cognitive functions. Both DMN hubs reveal reduced resting-state functional connectivity in individuals with PTSD (Bluhm et al., 2009; Miller et al., 2017; Sripada et al., 2012) – an observation that has been linked, in part, to childhood maltreatment or neglect. For example, Sripada et al. (2014) found that adults reporting a history of childhood abuse are more likely to demonstrate not only decreased DMN functional connectivity, but also greater cortisol levels in response to a perceived social stress. Accordingly, these results have been taken as evidence for the psychopathological vulnerability the DMN shows in relation to adverse environmental conditions, particularly in childhood, where reduced resting-state functional connectivity across the DMN may harbour the vestiges of an individual’s trauma history, or, alternatively, may serve as a predisposing factor towards the development of PTSD.

The DMN can be divided into two dissociable subsystems – the medial prefrontal and the medial-temporal subsystem. These subsystems are recruited during autobiographical memory processes, where the medial prefrontal and the medial-temporal subsystem are thought to govern different autobiographical memory processes, namely construction and elaboration, respectively (Buckner & Carroll, 2007; Cabeza & St Jacques, 2007; Svoboda, McKinnon, & Levine, 2006). Autobiographical memory-related construction refers to early memory formation processes, where the semantic and contextual information that provide the setting for a memory to be recalled are brought to mind – a process mediated mostly by the medial-prefrontal subsystem. Autobiographical memory-related elaboration refers to subsequent memory formation processes, where self-referential perspectives and visual imagery processes allow a memory to be re-experienced by recalling its more salient characteristics (i.e. emotional, sensory) – a process mediated by the medial-temporal subsystem (along with the posterior parietal cortex) (Buckner et al., 2008; Kim, 2012; Philippi, Tranel, Duff, & Rudrauf, 2013).

In PTSD, reduced resting-state functional connectivity between DMN hubs and the DMN more generally appears concentrated predominantly in the medial-temporal subsystem (Bluhm et al., 2009; DiGangi et al., 2016; Miller et al., 2017; Sripada et al., 2012) – a pattern related likely to the altered autobiographical memory-related re-experiencing observed among individuals with PTSD (for a review, see Brewin, 2015). Moreover, reduced functional connectivity between DMN-related hubs and the medial-temporal subsystem correlates negatively to symptom severity in avoidance and numbing measures administered to participants with PTSD (Miller et al., 2017). Accordingly, reduced DMN functional connectivity may promote clinical disturbances in self-related processes during rest in PTSD, which can include guilt, shame, or remorse emotional experiences, as well as alterations in perceptual experiences, including self-perceptions of body awareness that are perturbed during moments of depersonalization and/or derealization (Barredo et al., 2018; Bluhm et al., 2009; Cloitre, Scarvalone, & Difede, 1997; Frewen et al., 2008, 2020; van der Kolk, Roth, Pelcovitz, Sunday, & Spinazzola, 2005). To date, however, these hypotheses remain to be tested directly in individuals with PTSD.

4. The default mode network under threat in the aftermath of trauma

In PTSD, the DMN also demonstrates altered functional connectivity during threat- or trauma-related conditions – a pattern that contrasts sharply with the DMN deactivation observed usually in healthy individuals. Threat- or trauma-related information is processed generally by an inter-connected network comprised of brainstem, midbrain, and thalamic structures, jointly referred to as the innate alarm system (IAS) (Liddell et al., 2005). The IAS detects threat-related information at the level of the midbrain, where the information is then transmitted to the frontolimbic neural cortices (Tamietto & de Gelder, 2010). Critically, the IAS bypasses the primary sensory processing cortices, thus allowing threat information to be transmitted rapidly and permitting the network to respond to a stimulus that has been presented subliminally (i.e. below conscious threshold) (Tamietto & de Gelder, 2010; Williams et al., 2006). In PTSD, the IAS demonstrates increased activity during subliminal, trauma-related stimulus conditions as compared to healthy individuals (Felmingham et al., 2008; Bryant et al., 2008; Rabellino, Densmore, Frewen, Théberge, & Lanius, 2016; Terpou et al., 2019b; for a review, see Lanius et al., 2017), where a trauma-related stimulus refers to self-generated material in relation to an individual’s trauma memory, or, in healthy individuals, a highly aversive/stressful memory. In PTSD, subliminal, trauma-related stimulus conditions evoke stronger activity across the IAS, including the amygdala (Bryant et al., 2008; Felmingham et al., 2008; Steuwe et al., 2014), the midbrain periaqueductal grey (PAG) (Rabellino et al., 2016; Terpou et al., 2019b), as well as the brainstem more generally (Felmingham et al., 2008). In our own research, we have postulated that the IAS overactivation occurs in association with the increased hypervigilance and hyperarousal symptoms reported among individuals with PTSD – symptoms that are coordinated largely by the midbrain and, in particular, by the PAG (for a review, see Terpou et al., 2019c).

More recent works points towards the PAG as central to threat-related processing in PTSD. Here, the PAG refers to the grey matter located around the cerebral aqueduct of the midbrain, which, when activated, can engage evolutionarily conserved defensive responses that function to resist or to avoid an impending threat (e.g. fight, flight, faint; De Oca, DeCola, Maren, & Fanselow, 1998; Brandão, Zanoveli, Ruiz-Martinez, Oliveira, & Landeira-Fernandez, 2008; Fenster, Lebois, Ressler, & Suh, 2018; for a review, see Keay & Bandler, 2014). Terpou et al. (2019a, 2019b) recently investigated the functional characteristics of the PAG during subliminal, trauma-related stimulus conditions in participants with PTSD as compared to healthy individuals. Initially, Terpou et al. (2019b) assessed subcortical activity using improved spatial normalization procedures to attain greater resolution across brainstem, midbrain, and cerebellar brain structures (Diedrichsen, 2006). The approach revealed the PAG to display stronger activity in participants with PTSD as compared to healthy controls during subliminal, trauma-related stimulus conditions (Terpou et al., 2019a). These findings are in keeping with a putative bias towards evolutionarily conserved defensive responses in PTSD, which may be expressed more actively in participants with PTSD than in healthy controls (for a review, see Fragkaki, Thomaes, & Sijbrandij, 2016; Kozlowska, Walker, McLean, & Carrive, 2015; Terpou et al., 2019c).

In a subsequent paper, Terpou et al. (2019a) sought to assess functional connectivity of the PAG during subliminal, trauma-related stimulus conditions in participants with PTSD as compared to healthy individuals using the same participant sample and paradigm as described in Terpou et al. (2019b). Here, Terpou et al. (2019a) found significantly stronger functional connectivity between the PAG and the DMN in individuals with PTSD as compared to healthy controls during subliminal, trauma-related stimulus conditions. In particular, the DMN hubs (i.e. posterior cingulate cortex, precuneus, medial prefrontal cortex) were connected functionally to the PAG, but only during subliminal, trauma-related stimulus conditions and not during subliminal, neutral stimulus conditions (Figure 1(b)). Terpou et al. (2020) also evaluated the directed functional connectivity, or effective connectivity, between the PAG and the DMN to determine whether the PAG or the DMN were driving patterns of functional connectivity in participants with PTSD and healthy controls. In PTSD as compared to controls, Terpou et al. found the PAG showed stronger excitatory effective connectivity to the DMN during subliminal, trauma-related stimulus processing. Taken together, these findings contribute to our understanding of why individuals with PTSD may describe experientially links between trauma- and self-related processing states. Specifically, the PAG, which mediates innate, defensive responses, demonstrates strong, directed functional connectivity to the DMN responsible, in part, for mediating higher-order, self-related processing; these patterns are only present during subliminal, trauma-related stimulus conditions but not during rest more generally.

These findings shed light on the central role that trauma plays in personal identity among participants with PTSD – a relation that may be mediated, in part, by these functional alterations. A stronger understanding of PTSD-related asymmetries in functional connectivity across the DMN during rest, as well as during subliminal, trauma-related stimulus conditions may yield important clinical knowledge surrounding the sense of self in the aftermath of trauma. Going forward, such efforts will be necessary to grasp more thoroughly the experience of individuals with PTSD who do describe an inextricable link between trauma and the sense of self in the aftermath of trauma (for a review, see Olff et al., 2019).

5. The DMN under threat: how might DMN-related alterations present clinically?

Thus far, we have characterized the DMN-related alterations observed in individuals with PTSD as compared to healthy individuals, both during rest, as well as during subliminal, trauma-related stimulus conditions, where the former and the latter contexts are associated with greatly different functional connectivity patterns – that is, decreased and increased DMN functional connectivity, respectively. Additionally, we have reviewed an important function of the DMN in generating a perceived sense of self, where an interplay across interacting DMN-related processes associate to produce the sense of self, which, critically, shows disturbances in PTSD. For example, it is well known clinically that individuals with PTSD – particularly when associated with early childhood maltreatment – report frequently a rudimentary sense of self, or a sense of self that does not exist entirely, illustrated eloquently through statements, such as, ‘I do not know who I am,’ or, ‘I feel like I have stopped existing.’ Our research, as well as that of other research groups, suggests that these experiences may relate, in part, to the reduced functional connectivity observed during rest among individuals with PTSD, where these patterns contrast strikingly with the enhanced DMN functional connectivity observed under threat- or trauma-related stimulus conditions in PTSD. Here, data pointing to an increased DMN functional connectivity under conditions of threat (i.e. subliminal, trauma-related processing) are just emerging. Given the multi-functional properties of the DMN, we now offer several interpretations on why the DMN may display recruitment under conditions of threat from a clinical perspective. We hope the following discussion will serve as a starting point for future investigation of the DMN under threat in traumatized individuals.

Autobiographical memory represents an important function mediated by the DMN, which may assist our understanding on why the DMN demonstrates increased functional connectivity in PTSD during subliminal, trauma-related stimulus conditions. Autobiographical memory helps us learn from previous experiences (Qin & Northoff, 2011), where we can evaluate past experiences in the present to guide actions more adaptively. Autobiographical memory must then intrinsically represent our past experiences, which, in turn, would shape how we perceive the present – as the present exists in constant relation to the past. Through this lens, we can observe how detrimental childhood maltreatment may be towards the development of the DMN, which begins maturation during childhood and does not end until early adulthood (Sherman et al., 2014; for a review, see Fair et al., 2008). Where the maltreatment and/or trauma(s) are repeated often, we would suspect then that the developing DMN will be biased towards threat- or trauma-related conditions. This perspective may also hold for trauma experienced as a singular event during childhood, but then re-experienced, or relived internally whilst the trauma remains unprocessed (van der Kolk, 2015). Although the present perspective would be more difficult to apply for trauma(s) experienced later in adulthood, recent research suggests that individuals with combat-related PTSD are more likely to report childhood adversity or maltreatment as compared to combat-exposed individuals who do not go on to develop PTSD post-combat (Blosnich, Dichter, Cerulli, Batten, & Bossarte, 2014; Bremner, Southwick, Johnson, Yehuda, & Charney, 1993; Dannlowski et al., 2012). Here, DMN-related alterations may be developed during childhood and, in turn, act as a vulnerability factor towards the development of PTSD post-combat. Accordingly, we present the case where autobiographical memory-related processes may promote biases towards trauma-related processing among individuals with PTSD, which may assist to explain the stronger DMN functional connectivity during subliminal, trauma-related stimulus conditions reported by Terpou et al. (2019a). Future research will also need to determine whether such biases towards trauma-related processing may provoke certain traumatic re-enactments, or automatic repetitions of the past – a phenomenon observed frequently among individuals with PTSD. Here, van der Kolk (1989) has suggested that ‘assaults lead to hyperarousal states for which the memory can be state-dependent, or dissociated, where the memory only returns fully during renewed terror.’ It is therefore possible that some individuals with PTSD under certain conditions may seek situations involving threat or terror in order to engage the DMN. This may in turn afford the experience of a semblance of a sense of self and a related sense of agency, which may be lacking in the absence of extreme hyperarousal states.

Additionally, the ability to mentalize the perspective of others is another critical function mediated by the DMN, which may serve a central role in survival, particularly during conditions of interpersonal violence, where the awareness of the emotions and the malicious intents of others may prove life-saving. Under such conditions, a more intact DMN may serve as an indispensable aid to survival by assisting a repeatedly traumatized individual to act and to make decisions in the present, with consideration to the past and to the future, as well as to facilitate an ability to assess the mental states of others. This hypothesis awaits further examination, where, for example, relative to healthy controls, women with a history of developmental trauma are delayed in their response to sad, fearful, and happy, but not angry (i.e. threatening) voices (Nazarov et al., 2015), an effect that was enhanced also among survivors with an increased severity to childhood abuse. Interestingly, more severe symptoms of dissociation were associated with reduced accuracy in discriminating between emotions in the same sample.

Another important question raised by the findings of enhanced DMN connectivity under threat concerns the possibility that individuals with PTSD may be drawn towards fear- or terror-inducing conditions in an attempt to heighten emotional experience and to perceive at least the semblance of a sense of self. Here, individuals who suffer from PTSD report frequently that they do not ‘feel alive’ unless they engage in sensory seeking or reckless behaviours. The following quote from an individual with a history of significant developmental trauma describes eloquently how inducing fear and terror through engaging in shoplifting helped to create the experience of a rudimentary sense of self. She notes, ‘I started shoplifting when I was five. I’d pretend to add the quarter my mother gave me to the collection plate, then sink it deep and hot into the pocket of my Sunday dress. On the long walk home, I’d pass a pharmacy where I’d steal a Clark Bar or a Milky Way, pantomime leaving the quarter for my coke and with a mix of terror and thrill leave the store, sugar happy and known to myself … I shoplifted well into my adulthood, at great risk to me were I to be caught … It was always confusing why I did this. It was so, so risky. I knew that. But, I think the adrenaline organized me, rising it seemed from my belly through my brain, from the back to the front. I felt my feet; I knew my hands and fingers; I had eyes. I was agency. It lit me up. It was essential. At five and still at fifty, I didn’t exist to myself except as the artful dodger [pickpocket] – at these moments, I existed; all of me, in the act of stealing, I would “come online”.’

It is interesting to note that reckless behaviour is exhibited by many individuals with PTSD and, accordingly, has been included as a symptom of PTSD in the most recent version of the DSM, the DSM-5 (APA, 2013). As described in the quote above, reckless behaviour may assist the traumatized individual not only to feel more alive and embodied by helping to overcome intense symptoms of emotional numbing, but may also aid in bringing online a sense of agency that is lacking sorely in the aftermath of their personal trauma. It will therefore be critical for future research to examine the relation between reckless behaviour, fear/terror, and the integrity of the DMN. On balance, the findings reviewed here point further towards the urgent need to target therapeutically the sensory seeking and the reckless behaviour that may be evoked as a last resort to recruit the DMN, thus leading the participant with PTSD to experience a veneer of a sense of self they may have lost in the aftermath of trauma.

What are other implications for treatment that we need to consider? Given the findings described above, understanding the importance of clinical treatment to the restoration of the self, particularly in the absence of threat, will be of the utmost importance. Here, re-establishing, or establishing for the first time, a sense of self that is continuous across time and into the future has been a focus of treatment for trauma-related disorders for decades (Allen, 1995; Herman, 1992; van der Kolk, 2015). More specifically, overcoming the fragmentary, or the timeless nature of traumatic memories, increasing emotional awareness, and helping individuals with PTSD reclaim his/her body are critical components of both present- and past-centred therapies (i.e. Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT); Resick and Schnicke (1992); Prolonged Exposure Therapy; Foa, Hembree, and Rothbaum (2007); Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR); Shapiro (2018); Mindfulness Therapy; Boyd, Lanius, and McKinnon (2018); Lanius, Bluhm, and Frewen (2011); Frewen and Lanius (2015)) and mirror eloquently the functions of an intact DMN. Moreover, several present- and past-centred therapies, including mindfulness training (King et al., 2016), neurofeedback (Kluetsch et al., 2014), EMDR, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), and prolonged exposure (for a review, see Malejko, Abler, Plener, & Straub, 2017) that are used to treat PTSD have shown a restoration across the DMN while at rest.

Recently, psychotherapeutic interventions for individuals with PTSD have been combined with various psychoactive substances, including the stimulant/psychedelic hybrid 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) (Mithoefer, Grob, & Brewerton, 2016; Mithoefer et al., 2018). Here, Carhart-Harris et al. (2014) have shown MDMA to significantly activate the DMN during the recall of favourite and worst autobiographical memories in healthy controls. Strikingly, whereas positive memories were experienced as more vivid and emotionally intense, negative memories were experienced as less negative following administration of MDMA versus a placebo in healthy individuals. Future research examining the effects of MDMA in conjunction with psychotherapy in participants with PTSD will therefore need to elucidate DMN functional connectivity and integrity and associated DMN-related functions pre- and post-MDMA treatment.

In summary, we have attempted to provide a strong case for the involvement of the DMN towards an altered sense of self observed among individuals with PTSD, where, critically, both the DMN, neurobiologically, and the sense of self, clinically, demonstrate dramatic alterations among participants with PTSD. Future research examining treatment outcomes associated with trauma-related disorders will need to incorporate not only measures to assess the continuous sense of self into the future, but also an assessment of the distributed functions related to the DMN, including self-referential and autobiographical memory processes, theory of mind, and embodiment, as well as to investigate specifically how these processes may be influenced by present- and past-centred therapies. It will also be critical to examine DMN integrity and its related functions in interpersonal versus non-interpersonal trauma, as well as the vulnerability factors to the development of PTSD. Moreover, assessing traumatic re-enactments and reckless behaviour and their potential relation with the DMN will be crucial to further our understanding of trauma-related disorders. Only by targeting specifically critical DMN dysfunctions in the aftermath of trauma will we be able to assist further in the restoration of the self in PTSD, allowing these individuals to reclaim a sense of self that had previously been lost.

Funding Statement

RAL and MCM are co-funded by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (Grant Numbers: 171647). RAL is funded by the Canadian Institute for Military and Veteran Health Research (Grant Number: W7714-145967/001/SV T27).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Akiki, T. J., Averill, C. L., & Abdallah, C. G. (2017). A network-based neurobiological model of PTSD: Evidence from structural and functional neuroimaging studies. Current Psychiatry Reports, 19(11), 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiki, T. J., Averill, C. L., Wrocklage, K. M., Scott, J. C., Averill, L. A., Schweinsburg, B., & Abdallah, C. G. (2018). Default mode network abnormalities in posttraumatic stress disorder: A novel network-restricted topology approach. NeuroImage, 176, 489–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen, J. G. (1995). Coping with trauma: A guide to self-understanding. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Barredo, J., Aiken, E., Van ’T Wout-Frank, M., Greenberg, B. D., Carpenter, L. L., & Philip, N. S. (2018). Network functional architecture and aberrant functional connectivity in post-traumatic stress disorder: A clinical application of network convergence. Brain Connectivity, 8(9), 549–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, E. M., & Putnam, F. W. (1986). Development, reliability, and validity of a dissociation scale. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 174(12), 727–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blosnich, J. R., Dichter, M. E., Cerulli, C., Batten, S. V., & Bossarte, R. M. (2014). Disparities in adverse childhood experiences among individuals with a history of military service. JAMA Psychiatry, 71(9), 1041–1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluhm, R. L., Williamson, P. C., Osuch, E. A., Frewen, P. A., Stevens, T. K., Boksman, K., & Lanius, R. A. (2009). Alterations in default network connectivity in posttraumatic stress disorder related to early-life trauma. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, 34(3), 187–194. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, J. E., Lanius, R. A., & McKinnon, M. C. (2018). Mindfulness-based treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder: A review of the treatment literature and neurobiological evidence. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience, 42(6), 170021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandão, M. L., Zanoveli, J. M., Ruiz-Martinez, R. C., Oliveira, L. C., & Landeira-Fernandez, J. (2008). Different patterns of freezing behavior organized in the periaqueductal gray of rats: Association with different types of anxiety. Behavioural Brain Research, 188(1), 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner, J. D., Southwick, S. M., Johnson, D. R., Yehuda, R., & Charney, D. S. (1993). Childhood physical abuse and combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder in Vietnam veterans. American Journal of Psychiatry, 150(2), 235–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin, C. R. (2015). Re-experiencing traumatic events in PTSD: New avenues in research on intrusive memories and flashbacks. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 6. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v6.27180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere, J., & Runtz, M. (2002). The inventory of altered self-capacities (IASC): A standardized measure of identity, affect regulation, and relationship disturbance. Assessment, 9(3), 230–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, V. M., Labar, K. S., Haswell, C. C., Gold, A. L., Beall, S. K., Van Voorhees, E., & Morey, R. A. (2014). Altered resting-state functional connectivity of basolateral and centromedial amygdala complexes in posttraumatic stress disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology, 39(2), 351–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, R. A., Felmingham, K., Whitford, T. J., Kemp, A., Hughes, G., Peduto, A., & Williams, L. M. (2008). Rostral anterior cingulate volume predicts treatment response to cognitive-behavioural therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, 33(2), 142–146. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner, R. L., Andrews-Hanna, J. R., & Schacter, D. L. (2008). The brain’s default network: Anatomy, function, and relevance to disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1124(1), 1–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner, R. L., & Carroll, D. C. (2007). Self-projection and the brain. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(2), 49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabeza, R., & St Jacques, P. (2007). Functional neuroimaging of autobiographical memory. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(5), 219–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carhart-Harris, R. L., Wall, M. B., Erritzoe, D., Kaelen, M., Ferguson, B., De Meer, I., & Nutt, D. J. (2014). The effect of acutely administered MDMA on subjective and BOLD-fMRI responses to favourite and worst autobiographical memories. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 17(4), 527–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre, M., Scarvalone, P., & Difede, J. A. (1997). Posttraumatic stress disorder, self- and interpersonal dysfunction among sexually retraumatized women. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 10(3), 437–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway, M. A., & Pleydell-Pearce, C. W. (2000). The construction of autobiographical memories in the self-memory system. Psychological Review, 107(2), 261–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox, K. S., Resnick, H. S., & Kilpatrick, D. G. (2014). Prevalence and correlates of posttrauma distorted beliefs: Evaluating DSM-5 PTSD expanded cognitive symptoms in a national sample. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 27(3), 299–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, J. K., Frewen, P., McKinnon, M. C., & Lanius, R. A. (2011). Default mode alterations in posttraumatic stress disorder related to early-life trauma: A developmental perspective. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, 36(1), 56–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dannlowski, U., Stuhrmann, A., Beutelmann, V., Zwanzger, P., Lenzen, T., Grotegerd, D., & Kugel, H. (2012). Limbic scars: Long-term consequences of childhood maltreatment revealed by functional and structural magnetic resonance imaging. Biological Psychiatry, 71(4), 286–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Oca, B. M., DeCola, J. P., Maren, S., & Fanselow, M. S. (1998). Distinct regions of the periaqueductal gray are involved in the acquisition and expression of defensive responses. Journal of Neuroscience, 18(9), 3426–3432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di, Q. L., Wang, Z., Sun, Y. W., Wan, J. Q., Su, S. S., Zhou, Y., & Xu, J. R. (2012). A preliminary study of alterations in default network connectivity in post-traumatic stress disorder patients following recent trauma. Brain Research, 1484, 50–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diedrichsen, J. (2006). A spatially unbiased atlas template of the human cerebellum. NeuroImage, 33(1), 127–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiGangi, J. A., Tadayyon, A., Fitzgerald, D. A., Rabinak, C. A., Kennedy, A., Klumpp, H., & Phan, K. L. (2016). Reduced default mode network connectivity following combat trauma. Neuroscience Letters, 615, 37–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fair, D. A., Cohen, A. L., Dosenbach, N. U. F., Church, J. A., Miezin, F. M., Barch, D. M., & Schlaggar, B. L. (2008). The maturing architecture of the brain’s default network. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 105(10), 4028–4032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felmingham, K., Kemp, A. H., Williams, L., Falconer, E., Olivieri, G., Peduto, A., & Bryant, R. (2008). Dissociative responses to conscious and non-conscious fear impact underlying brain function in post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychological Medicine, 38(12), 1771–1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenster, R. J., Lebois, L. A. M., Ressler, K. J., & Suh, J. (2018). Brain circuit dysfunction in post-traumatic stress disorder: From mouse to man. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 19(9), 535–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa, E. B., Hembree, E. A., & Rothbaum, B. O. (2007). Prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD: Emotional processing of traumatic experiences: Therapist guide. Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/med:psych/9780195308501.001.0001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foa, E. B., Tolin, D. F., Ehlers, A., Clark, D. M., & Orsillo, S. M. (1999). The posttraumatic cognitions inventory (PTCI): Development and validation. Psychological Assessment, 11(3), 303–314. [Google Scholar]

- Fragkaki, I., Thomaes, K., & Sijbrandij, M. (2016). Posttraumatic stress disorder under ongoing threat: A review of neurobiological and neuroendocrine findings. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 7(1), 30915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fransson, P. (2005). Spontaneous low-frequency BOLD signal fluctuations: An fMRI investigation of the resting-state default mode of brain function hypothesis. Human Brain Mapping, 26(1), 15–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, T. W., Hart, J., Kimbrell, T., & Ross, E. D. (2009). Comprehension of affective prosody in veterans with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 21(1), 52–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frewen, P. A., & Lanius, R. A. (2015). Healing the traumatized self: Consciousness, neuroscience, treatment. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Frewen, P. A., Lanius, R. A., Dozois, D. J. A., Neufeld, R. W. J., Pain, C., Hopper, J. W., & Stevens, T. K. (2008). Clinical and neural correlates of alexithymia in posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 117(1), 171–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frewen, P. A., Schroeter, M. L., Riva, G., Cipresso, P., Fairfield, B., Padulo, C., & Northoff, G. (2020). Neuroimaging the consciousness of self: Review, and conceptual-methodological framework. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 112, 164–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston, K. J. (1994). Functional and effective connectivity in neuroimaging: A synthesis. Human Brain Mapping, 2(1–2), 56–78. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, K., Dipnall, J., Van Hooff, M., Lawrence-Wood, E., Searle, A., & AO, A. M. F. (2019). Identifying clusters of health symptoms in deployed military personnel and their relationship with probable PTSD. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 127, 109838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham, K., Searle, A., Van Hooff, M., Lawrence-Wood, E., & McFarlane, A. (2019). The Associations between physical and psychological symptoms and traumatic military deployment exposures. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 32(6), 957–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greicius, M. D., Krasnow, B., Reiss, A. L., & Menon, V. (2003). Functional connectivity in the resting brain: A network analysis of the default mode hypothesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 100(1), 253–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman, J. L. (1992). Complex PTSD: A syndrome in survivors of prolonged and repeated trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 5(3), 377–391. [Google Scholar]

- Keay, K. A., & Bandler, R. (2014). Periaqueductal Gray. The Rat Nervous System: Fourth Edition, 207–221. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-374245-2.00010-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kennis, M., Van Rooij, S. J. H., Van den Heuvel, M. P., Kahn, R. S., & Geuze, E. (2016). Functional network topology associated with posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans. NeuroImage: Clinical, 10(2), 302–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H. (2012). A dual-subsystem model of the brain’s default network: Self-referential processing, memory retrieval processes, and autobiographical memory retrieval. NeuroImage, 61(4), 966–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King, A. P., Block, S. R., Sripada, R. K., Rauch, S., Giardino, N., Favorite, T., & Liberzon, I. (2016). Altered default mode network (DMN) resting state functional connectivity following a mindfulness-based exposure therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in combat veterans of Afghanistan and Iraq. Depression and Anxiety, 33(4), 289–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluetsch, R. C., Ros, T., Théberge, J., Frewen, P. A., Calhoun, V. D., Schmahl, C., & Lanius, R. A. (2014). Plastic modulation of PTSD resting-state networks and subjective wellbeing by EEG neurofeedback. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 130(2), 123–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch, S. B. J., van Zuiden, M., Nawijn, L., Frijling, J. L., Veltman, D. J., & Olff, M. (2016). Aberrant resting-state brain activity in posttraumatic stress disorder: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Depression and Anxiety, 33(7), 592–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowska, K., Walker, P., McLean, L., & Carrive, P. (2015). Fear and the defense cascade. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 23(4), 263–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanius, R. A., Bluhm, R. L., Coupland, N. J., Hegadoren, K. M., Rowe, B., Théberge, J., & Brimson, M. (2010). Default mode network connectivity as a predictor of post-traumatic stress disorder symptom severity in acutely traumatized subjects. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 121(1), 33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanius, R. A., Bluhm, R. L., & Frewen, P. A. (2011). How understanding the neurobiology of complex post-traumatic stress disorder can inform clinical practice: A social cognitive and affective neuroscience approach. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 124(5), 331–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanius, R. A., Frewen, P. A., Tursich, M., Jetly, R., & McKinnon, M. C. (2015). Restoring large-scale brain networks in PTSD and related disorders: A proposal for neuroscientifically-informed treatment interventions. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 6(1), 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanius, R. A., Rabellino, D., Boyd, J. E., Harricharan, S., Frewen, P. A., & McKinnon, M. C. (2017). The innate alarm system in PTSD: Conscious and subconscious processing of threat. Current Opinion in Psychology, 14, 109–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine, B., Svoboda, E., Hay, J. F., Winocur, G., & Moscovitch, M. (2002). Aging and autobiographical memory: Dissociating episodic from semantic retrieval. Psychology and Aging, 17(4), 677–689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddell, B. J., Brown, K. J., Kemp, A. H., Barton, M. J., Das, P., Peduto, A., & Williams, L. M. (2005). A direct brainstem-amygdala-cortical “alarm” system for subliminal signals of fear. NeuroImage, 24(1), 235–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, S., Pan, F., Gao, W., Wei, Z., Wang, D., Hu, S., & Li, L. (2017). Neural correlates of childhood trauma with executive function in young healthy adults. Oncotarget, 8(45), 79843–79853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malejko, K., Abler, B., Plener, P. L., & Straub, J. (2017). Neural correlates of psychotherapeutic treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder: A systematic literature review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 8, 85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, D. R., Hayes, S. M., Hayes, J. P., Spielberg, J. M., Lafleche, G., & Verfaellie, M. (2017). Default mode network subsystems are differentially disrupted in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, 2(4), 363–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mithoefer, M. C., Grob, C. S., & Brewerton, T. D. (2016). Novel psychopharmacological therapies for psychiatric disorders: Psilocybin and MDMA. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(5), 481–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mithoefer, M. C., Mithoefer, A. T., Feduccia, A. A., Jerome, L., Wagner, M., Wymer, J., & Doblin, R. (2018). 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)-assisted psychotherapy for post-traumatic stress disorder in military veterans, firefighters, and police officers: A randomised, double-blind, dose-response, phase 2 clinical trial. The Lancet Psychiatry, 5(6), 486–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore, S. A., & Zoellner, L. A. (2007). Overgeneral autobiographical memory and traumatic events: An evaluative review. Psychological Bulletin, 133(3), 419–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazarov, A., Frewen, P. A., Oremus, C., Schellenberg, E. G., Mckinnon, M. C., & Lanius, R. A. (2015). Comprehension of affective prosody in women with post-traumatic stress disorder related to childhood abuse. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 131(5), 342–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazarov, A., Frewen, P. A., Parlar, M., Oremus, C., Macqueen, G., Mckinnon, M., & Lanius, R. A. (2014). Theory of mind performance in women with posttraumatic stress disorder related to childhood abuse. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 129(3), 193–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olff, M., Amstadter, A., Armour, C., Birkeland, M. S., Bui, E., Cloitre, M., & Thoresen, S. (2019). A decennial review of psychotraumatology: What did we learn and where are we going? European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1672948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patriat, R., Birn, R. M., Keding, T. J., & Herringa, R. J. (2016). Default-mode network abnormalities in pediatric posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 55(4), 319–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippi, C. L., Tranel, D., Duff, M., & Rudrauf, D. (2013). Damage to the default mode network disrupts autobiographical memory retrieval. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 10(3), 318–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piolino, P., Desgranges, B., Clarys, D., Guillery-Girard, B., Taconnat, L., Isingrini, M., & Eustache, F. (2006). Autobiographical memory, autonoetic consciousness, and self-perspective in aging. Psychology and Aging, 21(3), 510–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin, P., & Northoff, G. (2011). How is our self related to midline regions and the default-mode network? NeuroImage, 57(3), 1221–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabellino, D., Densmore, M., Frewen, P. A., Théberge, J., & Lanius, R. A. (2016). The innate alarm circuit in post-traumatic stress disorder: Conscious and subconscious processing of fear- and trauma-related cues. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, 248, 142–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raichle, M. E. (2015). The brain’s default mode network. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 38(1), 433–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resick, P. A., & Schnicke, M. K. (1992). Cognitive processing therapy for sexual assault victims. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60(5), 748–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuveni, I., Bonne, O., Giesser, R., Shragai, T., Lazarovits, G., Isserles, M., & Levin, N. (2016). Anatomical and functional connectivity in the default mode network of post-traumatic stress disorder patients after civilian and military-related trauma. Human Brain Mapping, 37(2), 589–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schore, A. N. (2003). Affect dysregulation and disorders of the self. New York: W. W. Norton & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, J., Lui, S., Meng, Y., Zhu, H., Qiu, C., Gong, Q., & Zhang, W. (2014). Alterations in low-level perceptual networks related to clinical severity in PTSD after an earthquake: A resting-state fMRI study. PLoS ONE, 9(5), e96834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, F. (2018). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy: Basic principles, protocols, and procedures (3rd ed.). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, L. E., Rudie, J. D., Pfeifer, J. H., Masten, C. L., McNealy, K., & Dapretto, M. (2014). Development of the default mode and central executive networks across early adolescence: A longitudinal study. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 10, 148–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spreng, R. N., Mar, R. A., & Kim, A. S. N. (2009). The common neural basis of autobiographical memory, prospection, navigation, theory of mind, and the default mode: A quantitative meta-analysis. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 21(3), 489–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sripada, C. S., Liberzon, I., Garfinkel, S. N., Sripada, R. K., King, A. P., Wang, X., & Welsh, R. C. (2012). Neural dysregulation in posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychosomatic Medicine, 74(9), 904–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sripada, R. K., Swain, J. E., Evans, G. W., Welsh, R. C., & Liberzon, I. (2014). Childhood poverty and stress reactivity are associated with aberrant functional connectivity in default mode network. Neuropsychopharmacology, 39(9), 2244–2251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St Jacques, P. L., Kragel, P. A., & Rubin, D. C. (2013). Neural networks supporting autobiographical memory retrieval in posttraumatic stress disorder. Cognitive, Affective and Behavioral Neuroscience, 13(3), 554–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steuwe, C., Daniels, J. K., Frewen, P. A., Densmore, M., Pannasch, S., Beblo, T., & Lanius, R. A. (2014). Effect of direct eye contact in PTSD related to interpersonal trauma: An fMRI study of activation of an innate alarm system. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 9(1), 88–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supekar, K., Uddin, L. Q., Prater, K., Amin, H., Greicius, M. D., & Menon, V. (2010). Development of functional and structural connectivity within the default mode network in young children. NeuroImage, 52(1), 290–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svoboda, E., McKinnon, M. C., & Levine, B. (2006). The functional neuroanatomy of autobiographical memory: A meta-analysis. Neuropsychologia, 44(12), 2189–2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamietto, M., & de Gelder, B. (2010). Neural bases of the non-conscious perception of emotional signals. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11(10), 697–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terpou, B. A., Densmore, M., Théberge, J., Frewen, P., McKinnon, M. C., Nicholson, A. A., & Lanius, R. A. (2020). The hijacked self: Disrupted functional connectivity between the periaqueductal gray and the default mode network in posttraumatic stress disorder using dynamic causal modeling. NeuroImage: Clinical. 27(1), 102345. 10.1016/j.nicl.2020.102345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terpou, B. A., Densmore, M., Théberge, J., Thome, J., Frewen, P., McKinnon, M. C., & Lanius, R. A. (2019a). The threatful self: Midbrain functional connectivity to cortical midline and parietal regions during subliminal trauma-related processing in PTSD. Chronic Stress, 3, 247054701987136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terpou, B. A., Densmore, M., Thome, J., Frewen, P., McKinnon, M. C., & Lanius, R. A. (2019b). The innate alarm system and subliminal threat presentation in posttraumatic stress disorder: Neuroimaging of the midbrain and cerebellum. Chronic Stress, 3, 247054701882149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terpou, B. A., Harricharan, S., McKinnon, M. C., Frewen, P., Jetly, R., & Lanius, R. A. (2019c). The effects of trauma on brain and body: A unifying role for the midbrain periaqueductal gray. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 97(9), 1110–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulving, E. (1985). Memory and consciousness. Canadian Psychology, 26(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- van der Kolk, B. A. (1989). The compulsion to repeat the trauma. Re-enactment, revictimization, and masochism. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 12(2), 389–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Kolk, B. A. (2015). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. New York: Viking. [Google Scholar]

- van der Kolk, B. A., Roth, S., Pelcovitz, D., Sunday, S., & Spinazzola, J. (2005). Disorders of extreme stress: The empirical foundation of a complex adaptation to trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 18(5), 389–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T., Liu, J., Zhang, J., Zhan, W., Li, L., Wu, M., & Gong, Q. (2016). Altered resting-state functional activity in posttraumatic stress disorder: A quantitative meta-analysis. Scientific Reports, 6(1), 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, L. M., Liddell, B. J., Kemp, A. H., Bryant, R. A., Meares, R. A., Peduto, A. S., & Gordon, E. (2006). Amygdala-prefrontal dissociation of subliminal and supraliminal fear. Human Brain Mapping, 27(8), 652–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, R. Z., Zhang, J. R., Qiu, C. J., Meng, Y. J., Zhu, H. R., Gong, Q. Y., & Zhang, W. (2011). Study on resting-state default mode network in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder after the earthquake. Journal of Sichuan University (Medical Science Edition), 42(3), 397–400. Retrieved from http://www.embase.com/search/results?subaction=viewrecord&from=export&id=L361 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]