Abstract

Purpose of Review

Insufficient knowledge about COVID-19 and the potential risks of COVID-19 are limiting organ transplantation in wait-listed candidates and deferring essential health care in solid organ transplant recipients. In this review, we expand the understanding and present an overview of the optimized management of COVID-19 in solid organ transplant recipients.

Recent Findings

Transplant recipients are at an increased risk of severe COVID-19. The unique characteristics of transplant recipients can make it more difficult to identify COVID-19. Based on the COVID-19 data to date and our experience, we present testing, management, and prevention methods for COVID-19. Comprehensive diagnostic tests should be performed to determine disease severity, phase of illness, and identify other comorbidities in transplant recipients diagnosed with COVID-19. Outpatients should receive education for preventative measures and optimal health care delivery minimizing potential infectious exposures. Multidisciplinary interventions should be provided to hospitalized transplant recipients for COVID-19 because of the complexity of caring for transplant recipients.

Summary

Transplant recipients should strictly adhere to infection prevention measures. Understanding of the transplant specific pathophysiology and development of effective treatment strategies for COVID-19 should be prioritized.

Keywords: COVID-19, Transplant recipient, Prevention, Management

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has led to unique challenges in solid organ transplantation as centers balance the risk of caring for immunosuppressed patients with the best timing and urgency of transplantation. Insufficient knowledge about COVID-19 and the potential risks of COVID-19 for transplant donors and recipients are limiting organ transplantation as well as research in transplantation [1–3]. However, transplantation is essential for lifesaving transplants of heart, lung, or liver and for deceased donor kidney transplantations (KT) in candidates with a lack of dialysis access or who are highly sensitized [4].

To assist in the timing of transplantation during the COVID-19 pandemic, Massie et al. developed a model for mortality of wait-listed patients and transplant recipients in relation to COVID-19 [5]. Kidney transplantation (KT) reliably provides survival benefit unless mortality risk for KT recipients exposed to COVID-19 is 50% or higher and community risk of COVID-19 acquisition is 50% or more per month over the first 6 months [5]. To date, the mortality of KT recipients with COVID-19 is much less than 50% (Table 2). However, this model does not account for the risk of living kidney donors, and this should be considered in transplant decision-making. Candidates and families should be educated about increased risks, and transplant teams should ensure that households are willing to adhere to the mitigation precautions that may be more stringent than local official guidance.

Table 2.

Laboratory findings and outcomes of transplant recipients and non-transplant recipients with COVID-19

| Akalin et al. [17] (n = 36) | Pereira et al. [18] (n = 90) | Yi et al. [19] (n = 21) | Chaudhry et al. [11]a (n = 35) | Fernandez-Ruiz et al. [20]a (n = 18) | Kates et al. [13]a (n = 482) | Mohan et al. [21]a (n = 15) | Tschoppet al. [22]a (n = 21) | Alberici et al. [23]b (n = 20) | Wang et al. [24] (n = 69) | Chaudhry et al. [11]a (n = 100) | Docherty et al. [9]a (n = 20,133) | Guan et al. [14]a (n = 1099) | Shi et al. [25]b (n = 81) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory findings | ||||||||||||||

| WBC (μL) | 5300 | 5160 | 6400 | 5500 | 4800 | 4800 | 5470 | 3820 | 6050 | 4200 | 8110 | |||

| Lymphocyte (μL) | 600 | 700 | 524 | 500 | 700 | 800 | 630 | 1170 | 1150 | 800 | 1000 | 1100 | ||

| Lymphopenia (%) | 79 | 42 | 33 | |||||||||||

| Platelet (×103/μL) | 146 | 176.5 | 176 | 196 | 171 | 178 | 168 | 212.2 | ||||||

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.6 | 3.3 | ||||||||||||

| ALT (U/L) | 18 | 23 | 25 | 46.2 | ||||||||||

| AST (U/L) | 26 | 37 | 28 | 40.8 | ||||||||||

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.89 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 0.75 | 0.85 | |||||||||

| LDH (U/L) | 336 | 253 | 288 | 275 | 231 | 224 | 334 | |||||||

| CPK (U/L) | 145 | 69 | ||||||||||||

| CRP (mg/dL) | 7.9 | 6.9 | 11.8 | 10.4 | 3.3 | 4.9 | 1.3 | 4.8 | ||||||

| Procalcitonin (ng/mL) | 0.2 | 0.29 | 0.23 | 0.46 | 0.16 | 0.22 | 0.13 | 0.15 | ||||||

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 1230 | 801.5 | 617.5 | 471 | 831 | 586.5 | ||||||||

| D-dimer (μg/mL) | 1.02 | 1.335 | 1.46 | 1.02 | 0.39 | 0.279 | 1.18 | 6.5 | ||||||

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 20 | 21 | 24 | 8.5 | ||||||||||

| Outcomes | ||||||||||||||

| Hospitalization (%) | 78 | 76 | 67 | 65.7 | ||||||||||

| AKI (%) | 46.8 | 11.1 | 40 | 42.9 | 30 | 43 | 0.5 | |||||||

| Acute cardiac injury (%) | ||||||||||||||

| ARDS (%) | 35.3 | 22.2 | 19 | 55 | 34 | 3.4 | ||||||||

| Mechanical ventilation (%) | 30.5 | 27 | 34.3 | 27 | 36 | 6.1 | ||||||||

| Death (%) | 28 | 18 | 5 | 22.8 | 27.8 | 7 | 9.5 | 25 | 7.5 | 25 | 26 | 1.4 | ||

aPatients hospitalized with COVID-19 were included

bPatients hospitalized with COVID-19 pneumonia were included Abbreviations: INR, international normalized ratio; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; CPK, creatine phosphokinase; CRP, C-reactive protein; IL-6, interleukin-6; AKI, acute kidney injury; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome

Transplantation centers have rapidly adopted management practices that will continue to evolve as knowledge for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) expands [1, 2]. This review article will provide an overview of our current understanding of COVID-19 as a basis for optimizing the care of this vulnerable population.

Clinical Features of Transplant Recipients with COVID 19

COVID-19 is an infectious viral disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 [6]. SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins bind to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), which is located on the surface of many cell types including heart, lung, kidney, liver, gastrointestinal tract and triggers internalization of the virus [6]. The targeting of ACE2 by SARS-CoV-2 leads to reduced ACE2 level and increased angiotensin II levels [7]. Subsequently, this process can activate the angiotensin II pathway, cause dysregulation of complement, hypercoagulation, hypoxia, hypotension, and cytokine storm [8]. In addition to direct invasion by SARS-CoV-2, these complex processes can cause to damage to multiple organs [8]. In a prospective study of 20,133 hospitalized patients with COVID-19, old age, male, obesity, and comorbidities, including chronic cardiac, pulmonary, kidney, liver disease, were risk factors of death [9]. Transplant recipients have several factors contributing to the risk of worse outcomes, including advanced age, immunosuppression, defective mucocutaneous barrier, co-infection, drug-induced leukopenia, and underlying cardiovascular comorbidities [10]. The mortality rates of transplant recipients with COVID-19 may be higher than in the general population. Chaudhry et al. compared the mortality between hospitalized transplant recipients and hospitalized non-transplant patients [11]. They showed that transplant status itself does not affect the mortality in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 (22.8% in transplant recipients vs. 25% in non-transplant patients) [11]. However, the proportion of severe COVID-19 severity scores associated with mortality was 8.6% and 19% in transplant recipients and non-transplant patients [11]. Roberts et al. reported that the mortality rate was higher in transplant recipients when compared using unpublished data from non-transplant patients (16% in transplant recipients vs. 4.3% in non-transplant patients) [12]. In another study, the mortality rate was 20.5% among 376 hospitalized transplant recipients [13]. Meanwhile, in a study by Guan et al., the mortality rate was 1.4% in 1099 hospitalized non-transplant patients [14]. However, it is not yet clear whether transplantation affects COVID-19 associated mortality. In the future, more results need to be accumulated.

The common symptoms in transplant recipients are outlined in Table 1. Atypical symptoms such as diarrhea are much more common (22−67%) compared to the general population (2−14%). Fever may be absent in up to 50% of transplant recipients [10, 15, 16]. These atypical symptoms alongside baseline cough, dyspnea, or medication side effects may make it more difficult to identify COVID-19 specific symptoms in transplant recipients. Due to high infectivity, transplant recipients may present with COVID-19 at any time after transplant (Table 1). Thus, a very low threshold for COVID-19 testing should be considered in recipients with even minor symptoms or high-risk exposures.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and clinical symptoms of transplant recipients and non-transplant recipients with COVID-19

| Akalin et al. [17] (n = 36) | Pereira et al. [18] (n = 90) | Yi et al. [19] (n = 21) | Chaudhry et al. [11]a (n = 35) | Fernandez-Ruiz et al. [20]a (n = 18) | Kates et al. [13]a (n = 482) | Mohan et al. [21]a (n = 15) | Tschoppet al. [22]a (n = 21) | Alberici et al. [23]b (n = 20) | Wang et al. [24] (n = 69) | Chaudhry et al. [11]a (n = 100) | Docherty et al. [9]a (n = 20,133) | Guan et al. [14]a (n = 1099) | Shi et al. [25]b (n = 81) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transplanted organs (n) | Kidney 36 |

Kidney 46 Liver 13 Lung17 Heart 9 Dual-organs 5 |

Kidney 12 Liver 3 Lung 2 Dual-organs 4 |

Kidney 26 Liver 0 Lung 4 Heart 5 Pancreas 1 |

Kidney 8 Liver 6 Heart 4 |

Kidney or Kidney/Pancreas 318 Liver or Liver/kidney 73 Heart or Heart/Kidney 57 Lung 30 Others 4 |

Kidney 15 |

Kidney 10 Liver 5 Lung 1 Heart 1 Pancreas 1 Dual 3 |

Kidney 20 | |||||

| Time from transplant to diagnosis (years) | 6.64 (2.87−10.61) | 5.58 (2.25−7.33) | 5 (2−10) | 4.08 (3.16−9.83) | 13 (9−12) | |||||||||

| Within 1 month (%) | 3 | 6.7 | ||||||||||||

| Within 1 year (%) | 14 | 6.7 | ||||||||||||

| Age (years) | 60 | 57 | 54.8 | 62 | 71 | 57.5 | 51 | 56 | 59 | 42 | 60 | 73 | 47 | 49.5 |

| Male (%) | 72 | 59 | 62 | 65.7 | 77.7 | 61.2 | 67 | 71 | 80 | 46 | 50 | 60 | 58.1 | 52 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||||||||||

| HTN (%) | 94 | 64 | 84 | 94.3 | 72.2 | 77.4 | 66.7 | 85 | 13 | 72 | 15.0 | 15 | ||

| DM (%) | 69 | 46 | 63 | 65.7 | 44.4 | 51 | 42.9 | 15 | 10 | 33 | 28.1 | 7.4 | 12 | |

| Heart disease (%) | 17 | CAD 32 |

CHF 28.6 CAD 14.3 |

27.7 |

CHF 8.3 CAD 21.8 |

CHF 4.8 CAD 23.8 |

CAD 15 | 12 |

CHF 14 CAD 12 |

30.9 | CAD 2.5 | 10 | ||

| Chronic lung disease (%) | 19 | 17.1 | 5.5 | 10.4 | 19 | 6 | 13 | 17.7 | 1.1 | 11 | ||||

| CKD (%) | 63 | 88.6 | 5.5 | 37.3 | 57 | 16.2 | 0.7 | 4 | ||||||

| Clinical symptoms | ||||||||||||||

| Fever (%) | 58 | 70 | 86 | 65.7 | 83 | 54.6 | 87 | 76 | 100 | 87 | 69 | 71.6 | 88.7 | 73 |

| Maximal temperature (°C) | 37.4 | 38.3 | ||||||||||||

| Cough (%) | 53 | 59 | 73 | 62.9 | 67 | 73.2 | 60 | 57.1 | 50 | 55 | 74 | 68.9 | 67.8 | 59 |

| Dyspnea (%) | 44 | 43 | 64 | 68.6 | 61 | 58.5 | 27 | 30 | 5 | 29 | 73 | 71.2 | 18.7 | 42 |

| Diarrhea (%) | 22 | 31 | 67 | 54.3 | 22 | 20 | 33.3 | 14 | 17 | 3.8 | 4 | |||

| Nausea/vomiting (%) | 8 | 22 | 7 | 33.3 | 4 | 5 |

aPatients hospitalized with COVID-19 were included

bPatients hospitalized with COVID-19 pneumonia were included

Abbreviations: CHF, congestive heart failure; CAD, coronary artery disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease

Tests for Transplant Recipients with COVID-19

Transplant recipients diagnosed with COVID-19 should be considered for diagnostic tests to determine disease severity, phase of illness, and identify other comorbidities. Table 3 shows the current tests recommended for transplant recipients with COVID-19 at the Johns Hopkins Comprehensive Transplant Center (JH-CTC). Lymphopenia is a common finding that correlates with disease severity (Tables 2 and 3). COVID-19 associated lymphopenia may be caused by direct virus-induced cell death or cytokine storm [8, 26], and further augmented by drug-associated myelotoxicity in transplant recipients receiving lymphocyte-depleting agents and/or antimetabolites. Levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) and IL-6 may be higher in transplant recipients with COVID-19 than the general population (Table 2) [17–19, 21, 24, 25]. Considering that lymphopenia, CRP, and IL-6 are independent factors related to the severity of COVID-19 [27, 28], these should be monitored closely in transplant recipients hospitalized with COVID-19.

Table 3.

| Tests on hospitalization | Laboratory results related with disease severity | Considerations in interpreting test results of transplant recipients | Monitoring interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complete blood counts with differential | Neutrophil count > 8000/μL, lymphocyte < 1000/μL, neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio, platelet < 100 × 103/μL | Myelosuppression by immunosuppressants | Daily |

| Coagulation tests | Prothrombin time ≥ 16 s | Daily | |

| D-dimer ± Fibrinogen | D-dimer > 1 μg/mL | Every 48–72 hoursa | |

| Comprehensive metabolic panel | Albumin level < 3.4 g/dL, ALT > 40 U/L, AST, bilirubin, BUN, creatinine > 1.1 mg/dL | Side effects by immunosuppressants and antimicrobial prophylaxis, toxicity by drug-drug interactions | Daily |

| LDH | > 250 U/L | Every 48–72 hoursa | |

| CPK | > 185 U/L | ||

| Ferritin | > 300 ng/mL | Every 48–72 hoursa | |

| Troponin Ib | > 28 pg/mL | ||

| CRP | > 4 mg/dL | Daily | |

| Procalcitonin | ≥ 0.07 ng/mL | Bacterial infection | |

| IL-6 | > 32.1 pg/mL | ||

| Urinalysis | New-onset proteinuria: renal involvement by SARS-COV-2 | ||

| Urine legionella and pneumococcal antigen | |||

| Respiratory viral panel | |||

| Culture for bacteria and fungi | |||

| CMV antigenemia and PCR | |||

| β-d-glucan and galactomannan | |||

| Cryptococcal antigen | |||

| Histoplasma antigen | |||

| Clostridium difficile toxin assay | |||

| Level of immunosuppressants | |||

| Chest radiography | |||

| ECG | |||

aTests should be performed daily in kidney transplant recipients with severe or rapidly progressing COVID-19

bTroponin concentration is measured if acute myocardial infarction of new onset LV dysfunction is considered

Abbreviations: AST, Aspartate amino transferase; ALT, Alanine amino transferase; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; LDH, Lactate dehydrogenase; CPK, Creatinine phosphokinase; CRP, C-reactive protein; IL-6, interleukin-6; CMV, cytomegalovirus; ECG, electrocardiogram

The incidence of liver dysfunction ranges from 14 to 53% in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 [34]. Although liver dysfunction seems to be mild in most patients, liver injury, especially hepatocellular type or mixed type, was detrimental in patients with severe COVID-19 [35]. Liver dysfunction may be caused by a direct virus-induced injury and/or provoked inflammatory response [34]. Cai et al. showed that elevated liver enzymes and histopathology were also associated with hepatotoxic medications in patients with COVID-19 [35]. Thus, liver enzymes should be frequently monitored and efforts considered to reduce non-essential medications with hepatotoxic potential.

Kidney injury is common in COVID-19 patients. In a study of 701 patients with COVID-19, 14.4% exhibited an elevated serum creatinine at admission and 5.1% developed acute kidney injury (AKI) during hospitalization [36]. Further, 43.9% had proteinuria and 26.7% had hematuria at hospital admission [36]. AKI may develop in response to the inflammatory phase and cytokine storm, and be exacerbated by hypercoagulation, microangiopathy, rhabdomyolysis, acute tubular necrosis, hypoxia, and hypotension [8, 37]. Proteinuria may be caused by direct infection of SARS-CoV-2 in podocytes and proximal tubular cells [38]. Because renal abnormalities are associated with a high risk of in-hospital death and appear to be more prevalent in transplant recipients [36], serum creatinine and urinalysis should be monitored closely.

Thrombotic complications have been reported to occur in 31% of intensive care unit (ICU) patients with COVID-19 and pulmonary thromboembolism was the most frequent among them [39]. Typical findings include an increased D-dimer level, a relatively modest decrease in platelet count, and a prolongation of the prothrombin time in patients with COVID-19 [40]. At autopsy of COVID-19 patients, segmental fibrin thrombosis in glomeruli was observed in renal findings [41]. Considering that immobilization and vascular damage increase the risk of thrombosis [40], thrombotic complications of allografts may be more common in transplant recipients with COVID-19. The International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) published an interim guidance statement recommending that prothrombin time, platelet count, and D-dimer concentrations should be monitored once or twice daily in patients with severe COVID-19 [29].

The prevalence of co-infection among COVID-19 patients ranges from 0% to 45% overall [42]. In a report by Zhou et al., the incidence of co-infection was 50% in non-survivors [30]. Bacterial, viral and fungal infections have all been documented and may need specialized diagnostic microbiology to identify these serious complications [42]. Most co-infections occurred within 1−4 days of onset of COVID-19 disease [31]. Generally, transplant recipients experience co-infection more commonly than immunocompetent individuals [43]. In a report by Roberts et al., co-infection was 22% and 35% in transplant recipients with COVID-19 and those admitted to ICU [12]. Thus, transplant recipients should be evaluated for bacterial and opportunistic fungal infections when diagnosed with COVID-19. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is common in transplant recipients and may reactivate under conditions of stress or augmented immunosuppression [43]. Table 3 shows tests that the JH-CTC examines: a respiratory viral panel, urine legionella and pneumococcal antigen, culture of blood and urine for bacteria and fungi, CMV antigenemia and PCR, β-d-glucan and galactomannan, cryptococcal antigen, histoplasma antigen in serum and urine, Clostridium difficile toxin assay. While bronchoscopy is not routinely available, tracheal aspirates could be considered for intubated patients to obtain microbiological samples. In instances where the risk of diagnostic procedures may be precluded sample collection, empiric antibiotics, anti-fungals, or anti-virals should be carefully considered based on the organ-specific pathogen risks.

An increase of the procalcitonin level reflects bacterial co-infection and predicts the progression toward severe disease [44]. Previously published literatures suggest that procalcitonin levels may be comparatively higher in transplant recipients with COVID-19 than in the general population with COVID-19 (Table 2) [11, 17, 18, 21, 23, 24]. The monitoring of procalcitonin may play a role in predicting bacterial infection in the absence of direct microbiology.

Chest radiography plays an important role in the diagnosis of COVID-19. Abnormal findings on chest radiography were identified in up to 76.5% of individuals, and abnormalities on chest computed tomography (CT) were 84.4% and 94.6% among patients with non-severe COVID-19 and patients with severe COVID-19, respectively [14]. Despite a higher sensitivity, the infectious precautions needed to safely transport patients with COVID-19 and decontaminate equipment necessitate thoughtful consideration of the optimal use of CT [45, 46]. Alternative modalities such as lung ultrasonography may provide results similar to chest CT to assess pneumonia and reduce staff/equipment exposure [46–48]. However, CT may still have a valuable role in the evaluation of pulmonary emboli and/or diagnosis of pneumonia when other modalities are non-diagnostic. Further studies are required to determine the optimal use of imaging in managing the care of the COVID-19 transplant recipient.

Outpatient Management for Transplant Recipients

Outpatient Prevention and Management of General Transplant Recipients

Evolving knowledge of viral transmission informs the approach to the management of transplant recipients with COVID-19. The median incubation period of COVID-19 is estimated to be 5.1 days and the majority of symptomatic patients develop symptoms within 11 days [49]. Moreover, the infectiousness of SARS-CoV-2 starts from 2.3 days before symptom onset and up to 10 days after resolution of symptoms in the immunocompetent host, but possibly up to 4 weeks in immunocompromised hosts. Unfortunately, 44% of infection occurs at the pre-symptomatic phase [50], and due to its high transmissibility in droplets, contact and aerosols, preventive precautions are critical.

Respiratory droplets, the most common mode of transmission, are formed when an infected patient sneezes, coughs, or even talks, and viral particles are directly inhaled, or when an uninfected individual touches a contaminated surface and subsequently their mucous membranes [51]. Transmission through respiratory droplet may be reduced with the use of surgical or cloth masks, and thus transplant recipients should ensure that they and all individuals outside of their household are wearing masks during an in-person encounter [52]. Further, hand hygiene is essential to reduce transmission from contact surfaces, as SARS-CoV-2 can be detectable on the surface of the plastic and stainless steel up to 72 h [52]. Given the higher risk of serious complications from COVID-19, we recommend that patients and household contacts receive ongoing education: the importance of exposure prevention and risk reduction measures, as these behaviors may erode over time.

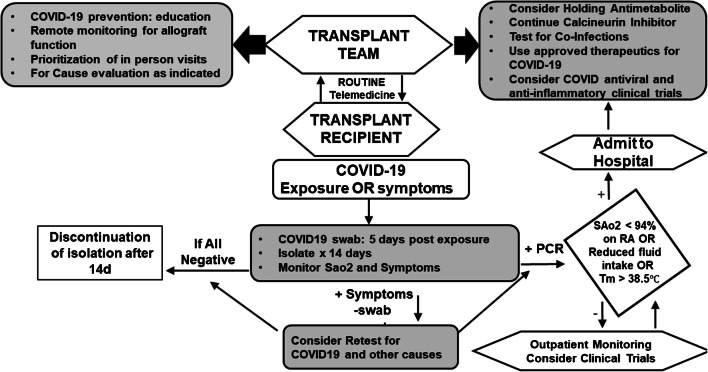

The complexity of routine transplant care in monitoring allograft function, toxicities, and general health has necessitated a reimagining of health care delivery during COVID-19 pandemic. In this regard, centers have instituted telemedicine, limited in-person visits, and increased remote monitoring allows uninterrupted outpatient care while limiting direct patient contact to highest priority individuals. With these tools, limited ambulatory care then ideally be provided in social distanced settings with appropriate COVID−19 screening to reduce nosocomial transmission risk [53]. Telemedicine can be performed using a combination of synchronous, asynchronous, or remote monitoring. Synchronous refers to real-time encounters via telephone or audio-video interaction. Asynchronous telemedicine is a “store-and-forward” technique that sends the collected data and images to clinicians. Remote patient monitoring refers to the direct transmission of a patient’s clinical measurements to their healthcare provider [52]. Telemedicine may also be an important component of preparation for in-person encounters to reduce the amount of time spent in direct patient contact and to conduct necessary COVID-19 symptom and behavior risk screening (Fig. 1) [54, 55]. For maximum utility, transplant centers may need to invest in resources for patient self-monitoring, including tools for vital signs monitoring, technology platforms, and resources to document objective findings.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart for management for solid organ recipients during COVID-19 pandemic. Abbreviations: MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; ALC, absolute lymphocyte count

The frequency of routine laboratory testing, routine health maintenance tests, and cancer screening should be considered to balance the infection risk of SARS-CoV-2 with the risk to health if these diagnostics are deferred. Ideally, when required, diagnostic tests should be performed at a facility that practices mitigation behaviors such as a restricted number of persons in waiting rooms, scheduled appointments, and strict screening of patients for COVID-19. Collaboration between transplantation specialists, monitoring of local COVID infection rates, and the local health care provider may be required [54, 56]. The frequency of allograft surveillance biopsies should be determined to take into account the individual risks and benefits, especially during this epidemic period. When available, non-invasive technologies such as donor-derived cell-free DNA (dd-cfDNA), gene expression profiles, and home spirometry may allow transplant recipients to reduce invasive procedures for rejection monitoring. In KT recipients, the negative predictive value of dd-cfDNA for any active rejection at a cutoff of 1.0% was 84%, and thus may be a good non-invasive marker of allograft surveillance [57]. While its role in other solid organ transplants is still being defined, peripheral gene expression tests may also be helpful for surveillance for cardiac allograft rejection to reduce need for invasive biopsies [54].

The emotional toll of the COVID-19 pandemic should be recognized and addressed with patients. Fear of COVID-19 and health recommendations to transplant recipients to shelter in place when there is significant community spread may worsen anxiety, and/or cause patients to defer essential health care. The emotional toll of social isolation may lead transplant recipients to engage in behaviors that increase their risk of exposure to COVID-19. Thus, the transplant team should assess mental health during their patient encounters and provide referrals or interventions as appropriate during this unprecedented challenge. In transplant recipients with COVID-19, depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbances associated with COVID-19 can worsen non-adherence to immunosuppressive therapy and increase the risk of allograft rejection [58]. Melatonin is an effective drug for anxiety and sleep disturbances, which might also be beneficial for clinical outcomes of patients with COVID-19 due to its anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant properties [59, 60].

Outpatient Management for Transplant Recipients with Suspected or Confirmed COVID-19

Transplant recipients with COVID-19 can progress rapidly and seriously. They should be monitored and managed through frequent communication between the transplant team and patients. Figure 1 shows a model for the management of solid organ transplant recipients during COVID-19 pandemic, based on recommendations of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the American Society of Transplantation (AST) [52, 61]. Transplant recipients with direct contact (< 6 ft for ≥ 15 min) with a COVID-19 infected individual should be quarantined for 14 days and consider testing for SARS-CoV-2 after exposure or if they develop symptoms [49, 52]. Patients with confirmed COVID-19 should check their temperature and respiratory rate (RR), oxygen saturation, and symptoms. Transplant centers should consider assistance for pulse oximeters if patients experience hardship in obtaining these devices. If they have dyspnea or RR ≥ 24 per minute, oxygen saturation < 94%, persistent or high fever, difficulty eating foods with predominant gastrointestinal symptoms, low urine volume (< 400 mL per day), or worsening of general conditions, they should plan for hospitalization (Fig. 1) [52, 54].

The determination of when a transplant recipient is no longer infectious is evolving. Immunocompromised patients may have prolonged viral shedding, and further research is needed to determine the timeframe of infectivity in this population [62, 63]. The AST recommends a 28-day time-frame because the shedding of the virus can be prolonged in transplant recipients, although infectivity is unclear [61]. This is different from recommendations for immunocompetent hosts and should be communicated to health care providers and COVID-19 infected transplant recipients. Alternatively, a test-based strategy has also been used with the use of negative results of RNA PCR tests from at least two consecutive respiratory specimens ≥ 24 h apart as well as recovery of symptoms.

Management for Hospitalized Transplant Recipients for COVID-19

COVID-19 progresses through syndrome phases that include: the early infection phase, the pulmonary phase, and the hyperinflammation phase [64]. The early infection phase is triggered by the virus itself and the hyperinflammation phase is developed by the host response.

At the initial stage or infection, most patients have mild, non-specific symptoms. Because SARS-CoV-2 multiplies and establishes residence in the host during this period, the reduction of immunosuppressive agents should be considered to enhance viral clearance [64]. At the JH-CTC, it is recommended that mycophenolate be preemptively discontinued if the absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) were < 700 cells/mL and reduced if the ALC was 700–1000 cells/mL. Because calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs) block nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) and thus transcription of downstream inflammatory cytokines, we do not recommend reducing the CNIs and maintain tacrolimus levels between 5 and 10 ng/mL. Clinical trials of therapies to enhance viral clearance, such convalescent plasma may be offered at this stage.

In the second stage, viral multiplication and localized lung inflammation occur [64]. Markers of systemic inflammation may be elevated. Anti-viral therapies, as discussed in a separate article of this issue, may be indicated for patients with hypoxia, and investigational agents may be considered. A minority of COVID-19 patients progress into the hyperinflammation phase. In this stage, markers of systemic inflammation are elevated and systemic organs would be involved [64]. Immunomodulatory agents have been studied and applied to reduce systemic inflammation to try and prevent multiorgan dysfunction, but with exception of dexamethasone, remain under off-label or investigational use.

Supportive therapy includes management of hypoxia, fluid therapy, medication adjustments, and control of symptoms such as fever, cough, and diarrhea. Considering that acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is one of the most severe complications in patients with COVID-19 and a leading cause of death (Table 2) [65], patients requiring mechanical ventilation should be managed per standard of care practices for ARDS. Proning may be required due to the distribution of parenchymal changes, and in some centers is initiated prior to intubation [66]. The optimal fluid therapy for COVID-19 patients has not been established but may need to be individualized based on the presence of AKI, Sepsis, or ARDS [37, 67]. As the risk of AKI is high in patients transplant recipients with COVID-19, avoidance of non-essential nephrotoxic agents may also be advisable [21, 30]. The use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ACEI/ARBs) has been controversial due to concerns that may increase susceptibility to the SARS-CoV-2 [6]. In recently published studies, use of ACEI/ARBs before or during hospitalization was not associated with mortality among hypertensive patients with COVID-19 [68, 69], and thus should be maintained as clinically indicated.

The ISTH recommends prophylactic dose low molecular weight heparin in patients with coagulopathy (D-dimer > 3 to 4 times, prolonged prothrombin time, platelet count < 100 × 103/μL, or fibrinogen < 2.0 g/L) and patients hospitalized for COVID-19 in the absence of any bleeding or thrombocytopenia [29, 40]. A study demonstrated that the use of prophylactic LMWH was associated with low mortality in patients with severe COVID-19.

The optimal regulation of transplant immunosuppression in COVID-19 remains a challenging question, with a paucity of clinical data for guidance. Immunosuppressive drugs may prolong viral shedding, have beneficial anti-inflammatory effects, or even have anti-viral properties [70]. Little is known about the exact role of cyclophilin in coronavirus replication, but it has been reported that cyclosporine, which also binds cyclophilin, may inhibit the replication of coronaviruses at noncytotoxic concentrations [71, 72]. In vitro, tacrolimus inhibited the replication of SARS-CoV, suggesting the requirement of FK506-binding proteins for virus growth [73]. Further, CNIs may be capable of reducing the frequency of cytokine release syndrome through inhibition of NFAT. However, the exact role of these agents for enhancing viral clearance in COVID-19 is unknown and merits further investigation. Given these in vitro effects and the need to maintain some immunosuppression to prevent allograft rejection, many centers, including ours, have implemented reduction or holding antimetabolite and continuing the CNIs and glucocorticoids in transplant recipients with COVID-19. Others have recommended that CNIs and the antimetabolite be immediately withdrawn and the glucocorticoid dosage increased in KT recipients with severe or rapidly progressing COVID-19 [54, 74]. However, we remain hesitant to recommend complete cessation of CNIs without further clinical data to support the safety of this practice.

While there is literature in the general population to support the use of augmented dexamethasone in severely ill COVID-19 recipients, these studies have not reported the outcomes of this augmentation in immunocompromised individuals. In a preliminary report by Horby et al., dexamethasone (6 mg daily for up to 10 days) reduced mortality among COVID-19 patients receiving mechanical ventilation or oxygen [75], and this has been incorporated into routine practice. However, optimal adjustment of immunosuppression and return to maintenance dosing remains unknown. As we have previously reported, permanent discontinuation of the antimetabolite in KT patients with a severe viral infection such as CMV and BK virus is safe and effective [76, 77]. However, there are less data about the safety of the prolonged cessation of antimetabolites in other organ transplants, particularly for viruses in whom the disease severity is characterized by a hyperactive immune response, or for conditions such as in thoracic transplant where respiratory viral infections have been shown to trigger immune responses that induce chronic allograft dysfunction [78–81].

Adjunctive Supplements

There has been much interest in supplements such as vitamin D and melatonin in adjunctive therapy for patients with COVID-19 due to their anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant properties and low risk of harm. Inadequate vitamin D levels have been found in > 70% abdominal transplant recipients [82] and may be exacerbated by glucocorticoids, CNIs, low sun exposure, and inadequate dietary intake [83]. Low vitamin D levels have been associated with a high risk of CMV infection and overall infection in transplant recipients [84, 85]. Further meta-analyses of RCT data have demonstrated that vitamin D has a protective effect against acute respiratory tract infection and with even further risk in subjects who concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) below 37.5 nmol/L [86]. In these studies, once daily dosing at modest doses (400–4000 IU/day) appeared to confer benefit, particularly when Vitamin D levels were low. The prevalence of vitamin D deficiency is 40−70% in the intensive care unit and circulating 25(OH)D concentrations may drop rapidly in the early illness [87]. However, in multi-center RCTs of critically ill patients, a single dose of 540,000 IU or short term therapy (50,000 IU or 100,000 IU for 5 days) did not show mortality benefit [88, 89]. As the relationship between vitamin D supplementation and improvement in COVID-19 outcomes has not yet been established, measurement of Vitamin D levels may be a reasonable strategy to guide supplementation using modest daily dosing until further data is available. In KT recipients, we routinely give ergocalciferol 50,000 units orally daily for 5 days at the time of transplant and upon a positive COVID-19 PCR.

Melatonin lowers the levels of circulating cytokines and may reduce pro-inflammatory cytokine levels in COVID-19 patients [60]. Further, stress and sleep deprivation induce immunosuppression. These negative effects on immunity may be alleviated by restoring sleep disorder and reducing anxiety through melatonin [90]. So far, the direct evidence of melatonin application in COVID-19 is unclear. Further research is needed to determine if it has a COVID specific application outside of generalized sleep and anxiety disorders.

Cytokine release syndrome (CRS), characterized by a systemic inflammatory response resulting from the release of inflammatory cytokines including IL-6, is a hallmark of COVID-19 progression [91]. Although immunomodulatory therapy is discussed separately, we note that blocking of the catecholamine pathway with alpha-1 adrenergic receptor antagonists (⍺-blockers) may reduce cytokine storms [92]. In a retrospective study, Vogelstein et al. found that the use of α-blockers was associated with reduced ARDS and death from CRS [93]. As such, prospective clinical trials are underway to determine whether these agents can pre-emptively reduce COVID-19 disease progression [94].

Patients can be discharged from the hospital when clinically indicated. Isolation should be maintained if the patients are discharged to home or long-term care facility before discontinuation of isolation and may pose a challenge in a safe return to a home environment if there are uninfected individuals in the home. Long-term care facilities should follow infection prevention and control recommendations for the care of COVID-19 patients [52].

As there is a paucity of high-quality evidence to guide management of the COVID-19 infected transplant recipient, many centers have implemented practices based on biological plausibility and extrapolation from scenarios which share common features with COVID-19. At our institution, we have noted markedly low mortality of 3.7% in the 1st 27 solid organ transplant recipients cared by our providers between March 15, 2020 and May 22, 2020, compared to reports from other institutions in similar time periods (Table 2). While we cannot yet definitely determine which of our practices contributed to this excellent outcome, we have in this section, detailed our center’s specific practices (Fig. 1), and look forward to further science to refine these clinical algorithms.

Conclusions

COVID-19 is an unprecedented worldwide challenge, that is, heightened in solid organ transplant recipients. While a worldwide effort is underway to identify the best therapeutics and vaccines, their risk and benefit in transplant recipients remain undetermined. Thus, it is critical to reinforce to transplant households to strictly adhere to infection prevention measures. Transplant recipients should remain in close communication with their health team to monitor their overall health, manage comorbidities and identify any new findings that may confer risk of COVID-19. Finally, understanding of the transplant specific pathophysiology, effective treatments, and adjunctive practices for COVID-19 should be prioritized as part of a comprehensive research strategy to optimize outcomes.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on COVID19 and Transplantation

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ahn C, Amer H, Anglicheau D, Ascher N, Baan C, Bat-Ireedui B, et al. Global transplantation COVID report March 2020. Transplantation. 2020;104:1974–1983. doi: 10.1097/tp.0000000000003258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyarsky BJ, Po-Yu Chiang T, Werbel WA, Durand CM, Avery RK, Getsin SN, Jackson KR, Kernodle AB, van Pilsum Rasmussen SE, Massie AB, Segev DL, Garonzik-Wang JM. Early impact of COVID-19 on transplant center practices and policies in the United States. Am J Transplant Off J Am Soc Transplant Am Soc Transplant Surg. 2020;20:1809–1818. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bromberg J, Baan C, Chapman J, Anegon I, Brennan DC, Chakera A, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on the state of clinical and laboratory research globally in transplantation in May 2020. Transplantation. 2020;Publish Ahead of Print. 10.1097/tp.0000000000003362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Rabb H. Kidney diseases in the time of COVID-19: major challenges to patient care. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(6):2749–2751. doi: 10.1172/jci138871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Massie AB, Boyarsky BJ, Werbel WA, Bae S, Chow EK, Avery RK, et al. Identifying scenarios of benefit or harm from kidney transplantation during the COVID-19 pandemic: a stochastic simulation and machine learning study. Am J Transplant Off J Am Soc Transplant Am Soc Transplant Surg. 2020. 10.1111/ajt.16117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Sanchis-Gomar F, Lavie CJ, Perez-Quilis C, Henry BM, Lippi G. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and antihypertensives (angiotensin receptor blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors) in coronavirus disease 2019. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95:1222–1230. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.South AM, Tomlinson L, Edmonston D, Hiremath S, Sparks MA. Controversies of renin-angiotensin system inhibition during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2020;16:1–3. doi: 10.1038/s41581-020-0279-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Batlle D, Soler MJ, Sparks MA, Hiremath S, South AM, Welling PA, Swaminathan S, on behalf of the COVID-19 and ACE2 in Cardiovascular, Lung, and Kidney Working Group Acute kidney injury in COVID-19: emerging evidence of a distinct pathophysiology. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31:1380–1383. doi: 10.1681/asn.2020040419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Docherty AB, Harrison EM, Green CA, Hardwick HE, Pius R, Norman L, et al. Features of 20 133 UK patients in hospital with covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1985. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fishman JA. Infection in organ transplantation. Am J Transplant Off J Am Soc Transplant Am Soc Transplant Surg. 2017;17(4):856–879. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaudhry ZS, Williams JD, Vahia A, Fadel R, Parraga Acosta T, Prashar R, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of COVID-19 in solid organ transplant recipients: a case-control study. Am J Transplant Off J Am Soc Transplant Am Soc Transplant Surg. 2020. 10.1111/ajt.16188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Roberts MB, Izzy S, Tahir Z, Al Jarrah A, Fishman JA, El Khoury J. COVID-19 in solid organ transplant recipients: dynamics of disease progression and inflammatory markers in ICU and non-ICU admitted patients. Transpl Infect Dis. 2020:e13407. 10.1111/tid.13407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Kates OS, Haydel BM, Florman SS, Rana MM, Chaudhry ZS, Ramesh MS, et al. COVID-19 in solid organ transplant: a multi-center cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. 10.1093/cid/ciaa1097.

- 14.Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, Liu L, Shan H, Lei CL, Hui DSC, du B, Li LJ, Zeng G, Yuen KY, Chen RC, Tang CL, Wang T, Chen PY, Xiang J, Li SY, Wang JL, Liang ZJ, Peng YX, Wei L, Liu Y, Hu YH, Peng P, Wang JM, Liu JY, Chen Z, Li G, Zheng ZJ, Qiu SQ, Luo J, Ye CJ, Zhu SY, Zhong NS, China Medical Treatment Expert Group for Covid-19 Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manuel O, Estabrook M. RNA respiratory viral infections in solid organ transplant recipients: guidelines from the American Society of Transplantation Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Clin Transpl. 2019;33(9):e13511. doi: 10.1111/ctr.13511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sawyer RG, Crabtree TD, Gleason TG, Antevil JL, Pruett TL. Impact of solid organ transplantation and immunosuppression on fever, leukocytosis, and physiologic response during bacterial and fungal infections. Clin Transpl. 1999;13(3):260–265. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0012.1999.130307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akalin E, Azzi Y, Bartash R, Seethamraju H, Parides M, Hemmige V, Ross M, Forest S, Goldstein YD, Ajaimy M, Liriano-Ward L, Pynadath C, Loarte-Campos P, Nandigam PB, Graham J, le M, Rocca J, Kinkhabwala M. Covid-19 and kidney transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(25):2475–2477. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2011117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pereira MR, Mohan S, Cohen DJ, Husain SA, Dube GK, Ratner LE, Arcasoy S, Aversa MM, Benvenuto LJ, Dadhania DM, Kapur S, Dove LM, Brown RS, Jr, Rosenblatt RE, Samstein B, Uriel N, Farr MA, Satlin M, Small CB, Walsh TJ, Kodiyanplakkal RP, Miko BA, Aaron JG, Tsapepas DS, Emond JC, Verna EC. COVID-19 in solid organ transplant recipients: initial report from the US epicenter. Am J Transplant Off J Am Soc Transplant Am Soc Transplant Surg. 2020;20:1800–1808. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yi SG, Rogers AW, Saharia A, Aoun M, Faour R, Abdelrahim M, et al. Early experience with COVID-19 and solid organ transplantation at a US high-volume transplant center. Transplantation. 2020;Publish Ahead of Print. 10.1097/tp.0000000000003339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Fernández-Ruiz M, Andrés A, Loinaz C, Delgado JF, López-Medrano F, San Juan R, González E, Polanco N, Folgueira MD, Lalueza A, Lumbreras C, Aguado JM. COVID-19 in solid organ transplant recipients: a single-center case series from Spain. Am J Transplant Off J Am Soc Transplant Am Soc Transplant Surg. 2020;20:1849–1858. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mohan S. Early description of coronavirus 2019 disease in kidney transplant recipients in New York. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31:1150–1156. doi: 10.1681/asn.2020030375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tschopp J, L'Huillier AG, Mombelli M, Mueller NJ, Khanna N, Garzoni C, Meloni D, Papadimitriou-Olivgeris M, Neofytos D, Hirsch HH, Schuurmans MM, Müller T, Berney T, Steiger J, Pascual M, Manuel O, Delden C, Swiss Transplant Cohort Study (STCS) Amico P, Aubert JD, Banz V, Beldi G, Benden C, Berger C, Binet I, Bochud PY, Branca S, Bucher H, Carell T, Catana E, Chalandon Y, Geest S, Rougemont O, Dickenmann M, Duchosal M, Elkrief L, Fehr T, Ferrari-Lacraz S, Garzoni C, Soccal PG, Gaudet C, Giostra E, Golshayan D, Hadaya K, Halter J, Hauri D, Heim D, Hess C, Hillinger S, Hirsch HH, Hofbauer G, Huynh-Do U, Immer F, Klaghofer R, Koller M, Laesser B, Laube G, Lehmann R, Lovis C, Majno P, Manuel O, Marti HP, Martin PY, Martinelli M, Meylan P, Mueller NJ, Müller A, Müller T, Müllhaupt B, Pascual M, Passweg J, Posfay-Barbe K, Rick J, Roosnek E, Rosselet A, Rothlin S, Ruschitzka F, Schanz U, Schaub S, Schnyder A, Schuurmans M, Seiler C, Sprachta J, Stampf S, Steinack C, Steiger J, Stirnimann G, Toso C, van Delden C, Venetz JP, Villard J, Wick M, Wilhelm M, Yerly P. First experience of SARS-CoV-2 infections in solid organ transplant recipients in the Swiss transplant cohort study. Am J Transplant Off J Am Soc Transplant Am Soc Transplant Surg. 2020;20:2876–2882. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alberici F, Delbarba E, Manenti C, Econimo L, Valerio F, Pola A, Maffei C, Possenti S, Zambetti N, Moscato M, Venturini M, Affatato S, Gaggiotti M, Bossini N, Scolari F. A single center observational study of the clinical characteristics and short-term outcome of 20 kidney transplant patients admitted for SARS-CoV2 pneumonia. Kidney Int. 2020;97(6):1083–1088. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Z, Yang B, Li Q, Wen L, Zhang R. Clinical features of 69 cases with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:769–777. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shi H, Han X, Jiang N, Cao Y, Alwalid O, Gu J, Fan Y, Zheng C. Radiological findings from 81 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(4):425–434. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30086-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen G, Wu D, Guo W, Cao Y, Huang D, Wang H, Wang T, Zhang X, Chen H, Yu H, Zhang X, Zhang M, Wu S, Song J, Chen T, Han M, Li S, Luo X, Zhao J, Ning Q. Clinical and immunological features of severe and moderate coronavirus disease 2019. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(5):2620–2629. doi: 10.1172/jci137244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ji D, Zhang D, Xu J, Chen Z, Yang T, Zhao P, Chen G, Cheng G, Wang Y, Bi J, Tan L, Lau G, Qin E. Prediction for progression risk in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia: the CALL score. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:1393–1399. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu F, Li L, Xu M, Wu J, Luo D, Zhu Y, Li BX, Song XY, Zhou X. Prognostic value of interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, and procalcitonin in patients with COVID-19. J Clin Virol. 2020;127:104370. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thachil J, Tang N, Gando S, Falanga A, Cattaneo M, Levi M, Clark C, Iba T. ISTH interim guidance on recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(5):1023–1026. doi: 10.1111/jth.14810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu X, Ge Y, Wu T, Zhao K, Chen Y, Wu B, Zhu F, Zhu B, Cui L. Co-infection with respiratory pathogens among COVID-2019 cases. Virus Res. 2020;285:198005. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2020.198005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.ESC. ESC guidance for the diagnosis and management of CV disease during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.escardio.org/Education/COVID-19-and-Cardiology/ESC-COVID%2D%2DGuidance. Accessed 21 Apr 2020

- 33.Galloway JB, Norton S, Barker RD, Brookes A, Carey I, Clarke BD, Jina R, Reid C, Russell MD, Sneep R, Sugarman L, Williams S, Yates M, Teo J, Shah AM, Cantle F. A clinical risk score to identify patients with COVID-19 at high risk of critical care admission or death: An observational cohort study. J Infect. 2020;81:282–288. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.05.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fix OK, Hameed B, Fontana RJ, Kwok RM, McGuire BM, Mulligan DC, et al. Clinical best practice advice for hepatology and liver transplant providers during the COVID-19 pandemic: AASLD Expert Panel Consensus Statement. Hepatology. 2020. 10.1002/hep.31281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Cai Q, Huang D, Yu H, Zhu Z, Xia Z, Su Y, Li Z, Zhou G, Gou J, Qu J, Sun Y, Liu Y, He Q, Chen J, Liu L, Xu L. COVID-19: abnormal liver function tests. J Hepatol. 2020;73:566–574. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheng Y, Luo R, Wang K, Zhang M, Wang Z, Dong L, Li J, Yao Y, Ge S, Xu G. Kidney disease is associated with in-hospital death of patients with COVID-19. Kidney Int. 2020;97(5):829–838. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ronco C, Reis T, Husain-Syed F. Management of acute kidney injury in patients with COVID-19. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:738–742. doi: 10.1016/s2213-2600(20)30229-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martinez-Rojas MA, Vega-Vega O, Bobadilla NA. Is the kidney a target of SARS-CoV-2? Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2020;318(6):F1454–F1f62. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00160.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klok FA, Kruip M, van der Meer NJM, Arbous MS, Gommers D, Kant KM, et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020;191:145–147. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Levi M, Thachil J, Iba T, Levy JH. Coagulation abnormalities and thrombosis in patients with COVID-19. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7(6):e438–ee40. doi: 10.1016/s2352-3026(20)30145-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Su H, Yang M, Wan C, Yi LX, Tang F, Zhu HY, Yi F, Yang HC, Fogo AB, Nie X, Zhang C. Renal histopathological analysis of 26 postmortem findings of patients with COVID-19 in China. Kidney Int. 2020;98:219–227. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lai CC, Wang CY, Hsueh PR. Co-infections among patients with COVID-19: the need for combination therapy with non-anti-SARS-CoV-2 agents? J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020. 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Timsit JF, Sonneville R, Kalil AC, Bassetti M, Ferrer R, Jaber S, Lanternier F, Luyt CE, Machado F, Mikulska M, Papazian L, Pène F, Poulakou G, Viscoli C, Wolff M, Zafrani L, van Delden C. Diagnostic and therapeutic approach to infectious diseases in solid organ transplant recipients. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45(5):573–591. doi: 10.1007/s00134-019-05597-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lippi G, Plebani M. Procalcitonin in patients with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a meta-analysis. Clin Chim Acta. 2020;505:190–191. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Amalou A, Turkbey B, Xu S, Turkbey E, An P, Carrafiello G, Ierardi AM, Suh R, Amalou H, Wood BJ. Disposable isolation device to reduce COVID-19 contamination during CT scanning. Acad Radiol. 2020;27:1119–1125. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2020.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peng QY, Wang XT, Zhang LN. Findings of lung ultrasonography of novel corona virus pneumonia during the 2019-2020 epidemic. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(5):849–850. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05996-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mayo PH, Copetti R, Feller-Kopman D, Mathis G, Maury E, Mongodi S, Mojoli F, Volpicelli G, Zanobetti M. Thoracic ultrasonography: a narrative review. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45(9):1200–1211. doi: 10.1007/s00134-019-05725-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pascarella G, Strumia A, Piliego C, Bruno F, Del Buono R, Costa F, et al. COVID-19 diagnosis and management: a comprehensive review. J Intern Med. 2020;288:192–206. doi: 10.1111/joim.13091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lauer SA, Grantz KH, Bi Q, Jones FK, Zheng Q, Meredith HR, Azman AS, Reich NG, Lessler J. The incubation period of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) from publicly reported confirmed cases: estimation and application. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(9):577–582. doi: 10.7326/m20-0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.He X, Lau EHY, Wu P, Deng X, Wang J, Hao X, Lau YC, Wong JY, Guan Y, Tan X, Mo X, Chen Y, Liao B, Chen W, Hu F, Zhang Q, Zhong M, Wu Y, Zhao L, Zhang F, Cowling BJ, Li F, Leung GM. Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26(5):672–675. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0869-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Abbasi-Oshaghi E, Mirzaei F, Farahani F, Khodadadi I, Tayebinia H. Diagnosis and treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): laboratory, PCR, and chest CT imaging findings. Int J Surg. 2020;79:143–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.CDC. Coronavirus (COVID-19). https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov. Accessed 25 Jun 2020

- 53.Daggubati LC, Eichberg DG, Ivan ME, Hanft S, Mansouri A, Komotar RJ, D'Amico RS, Zacharia BE. Telemedicine for outpatient neurosurgical oncology care: lessons learned for the future during the COVID-19 pandemic. World Neurosurg. 2020;139:e859–e863. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.05.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gleeson SE, Formica RN, Marin EP. Outpatient Management of the Kidney Transplant Recipient during the SARS-CoV-2 virus pandemic. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15:892–895. doi: 10.2215/cjn.04510420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lal H, Sharma DK, Patralekh MK, Jain VK, Maini L. Out patient department practices in orthopaedics amidst COVID-19: the evolving model. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2020;11(4):700–712. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2020.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Boettler T, Newsome PN, Mondelli MU, Maticic M, Cordero E, Cornberg M, Berg T. Care of patients with liver disease during the COVID-19 pandemic: EASL-ESCMID position paper. JHEP Rep. 2020;2(3):100113. doi: 10.1016/j.jhepr.2020.100113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bloom RD, Bromberg JS, Poggio ED, Bunnapradist S, Langone AJ, Sood P, Matas AJ, Mehta S, Mannon RB, Sharfuddin A, Fischbach B, Narayanan M, Jordan SC, Cohen D, Weir MR, Hiller D, Prasad P, Woodward RN, Grskovic M, Sninsky JJ, Yee JP, Brennan DC, Circulating Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA in Blood for Diagnosing Active Rejection in Kidney Transplant Recipients (DART) Study Investigators Cell-free DNA and active rejection in kidney allografts. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(7):2221–2232. doi: 10.1681/asn.2016091034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.De Pasquale C, Pistorio ML, Veroux M, Indelicato L, Biffa G, Bennardi N, et al. Psychological and psychopathological aspects of kidney transplantation: a systematic review. Front Psych. 2020;11:106. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Reiter RJ, Abreu-Gonzalez P, Marik PE, Dominguez-Rodriguez A. Therapeutic algorithm for use of melatonin in patients with COVID-19. Front Med. 2020;7:226. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang R, Wang X, Ni L, Di X, Ma B, Niu S, et al. COVID-19: melatonin as a potential adjuvant treatment. Life Sci. 2020;250:117583. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.AST. 2019-nCoV (Coronavirus): Recommendations and guidance for organ donor testing https://www.myast.org/sites/default/files/internal/COVID19FAQDonorTesting05142020.pdf. Accessed 19 May 2020

- 62.Zhu L, Gong N, Liu B, Lu X, Chen D, Chen S, Shu H, Ma K, Xu X, Guo Z, Lu E, Chen D, Ge Q, Cai J, Jiang J, Wei L, Zhang W, Chen G, Chen Z. Coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in immunosuppressed renal transplant recipients: a summary of 10 confirmed cases in Wuhan, China. Eur Urol. 2020;77(6):748–754. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Memoli MJ, Athota R, Reed S, Czajkowski L, Bristol T, Proudfoot K, Hagey R, Voell J, Fiorentino C, Ademposi A, Shoham S, Taubenberger JK. The natural history of influenza infection in the severely immunocompromised vs nonimmunocompromised hosts. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(2):214–224. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Siddiqi HK, Mehra MR. COVID-19 illness in native and immunosuppressed states: a clinical-therapeutic staging proposal. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2020;39(5):405–407. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2020.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ruan Q, Yang K, Wang W, Jiang L, Song J. Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(5):846–848. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05991-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Phua J, Weng L, Ling L, Egi M, Lim CM, Divatia JV, Shrestha BR, Arabi YM, Ng J, Gomersall CD, Nishimura M, Koh Y, du B, Asian Critical Care Clinical Trials Group Intensive care management of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): challenges and recommendations. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(5):506–517. doi: 10.1016/s2213-2600(20)30161-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Giwa AL, Desai A, Duca A. Novel 2019 coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19): an updated overview for emergency clinicians. Emerg Med Pract. 2020;22(5):1–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fosbøl EL, Butt JH, Østergaard L, Andersson C, Selmer C, Kragholm K, Schou M, Phelps M, Gislason GH, Gerds TA, Torp-Pedersen C, Køber L. Association of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker use with COVID-19 diagnosis and mortality. Jama. 2020;324:168–177. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.11301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang P, Zhu L, Cai J, Lei F, Qin JJ, Xie J, Liu YM, Zhao YC, Huang X, Lin L, Xia M, Chen MM, Cheng X, Zhang X, Guo D, Peng Y, Ji YX, Chen J, She ZG, Wang Y, Xu Q, Tan R, Wang H, Lin J, Luo P, Fu S, Cai H, Ye P, Xiao B, Mao W, Liu L, Yan Y, Liu M, Chen M, Zhang XJ, Wang X, Touyz RM, Xia J, Zhang BH, Huang X, Yuan Y, Loomba R, Liu PP, Li H. Association of Inpatient use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers with mortality among patients with hypertension hospitalized with COVID-19. Circ Res. 2020;126(12):1671–1681. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.120.317134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Brennan DC, Aguado JM, Potena L, Jardine AG, Legendre C, Säemann MD, Mueller NJ, Merville P, Emery V, Nashan B. Effect of maintenance immunosuppressive drugs on virus pathobiology: evidence and potential mechanisms. Rev Med Virol. 2013;23(2):97–125. doi: 10.1002/rmv.1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tanaka Y, Sato Y, Sasaki T. Suppression of coronavirus replication by cyclophilin inhibitors. Viruses. 2013;5(5):1250–1260. doi: 10.3390/v5051250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Willicombe M, Thomas D, McAdoo S. COVID-19 and calcineurin inhibitors: should they get left out in the storm? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31(6):1145–1146. doi: 10.1681/asn.2020030348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Carbajo-Lozoya J, Müller MA, Kallies S, Thiel V, Drosten C, von Brunn A. Replication of human coronaviruses SARS-CoV, HCoV-NL63 and HCoV-229E is inhibited by the drug FK506. Virus Res. 2012;165(1):112–117. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kronbichler A, Gauckler P, Windpessl M, Il Shin J, Jha V, Rovin BH, Oberbauer R. COVID-19: implications for immunosuppression in kidney disease and transplantation. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2020;16(7):365–367. doi: 10.1038/s41581-020-0305-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, Mafham M, Bell JL, Linsell L, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19-preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2020. 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436.

- 76.Spinner ML, Saab G, Casabar E, Bowman LJ, Storch GA, Brennan DC. Impact of prophylactic versus preemptive valganciclovir on long-term renal allograft outcomes. Transplantation. 2010;90(4):412–418. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181e81afc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mwintshi K, Brennan DC. Prevention and management of cytomegalovirus infection in solid-organ transplantation. Expert Rev Anti-Infect Ther. 2007;5(2):295–304. doi: 10.1586/14787210.5.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Peghin M, Los-Arcos I, Hirsch HH, Codina G, Monforte V, Bravo C, Berastegui C, Jauregui A, Romero L, Cabral E, Ferrer R, Sacanell J, Román A, Len O, Gavaldà J. Community-acquired respiratory viruses are a risk factor for chronic lung allograft dysfunction. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;69(7):1192–1197. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gunasekaran M, Bansal S, Ravichandran R, Sharma M, Perincheri S, Rodriguez F, Hachem R, Fisher CE, Limaye AP, Omar A, Smith MA, Bremner RM, Mohanakumar T. Respiratory viral infection in lung transplantation induces exosomes that trigger chronic rejection. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2020;39(4):379–388. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2019.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Seifert ME, Gunasekaran M, Horwedel TA, Daloul R, Storch GA, Mohanakumar T, Brennan DC. Polyomavirus reactivation and immune responses to kidney-specific self-antigens in transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(4):1314–1325. doi: 10.1681/asn.2016030285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hardinger KL, Koch MJ, Bohl DJ, Storch GA, Brennan DC. BK-virus and the impact of pre-emptive immunosuppression reduction: 5-year results. Am J Transplant Off J Am Soc Transplant Am Soc Transplant Surg. 2010;10(2):407–415. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02952.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Eyal O, Aharon M, Safadi R, Elhalel MD. Serum vitamin D levels in kidney transplant recipients: the importance of an immunosuppression regimen and sun exposure. Isr Med Assoc J. 2013;15(10):628–633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sarno G, Nappi R, Altieri B, Tirabassi G, Muscogiuri E, Salvio G, Paschou SA, Ferrara A, Russo E, Vicedomini D, Vincenzo C, Vryonidou A, Della Casa S, Balercia G, Orio F, de Rosa P. Current evidence on vitamin D deficiency and kidney transplant: what’s new? Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2017;18(3):323–334. doi: 10.1007/s11154-017-9418-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kalluri HV, Sacha LM, Ingemi AI, Shullo MA, Johnson HJ, Sood P, et al. Low vitamin D exposure is associated with higher risk of infection in renal transplant recipients. Clin Transpl. 2017;31(5). 10.1111/ctr.12955. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 85.Astor BC, Djamali A, Mandelbrot DA, Parajuli S, Melamed ML. The association of 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels with late cytomegalovirus infection in kidney transplant recipients: the Wisconsin Allograft Recipient Database. Transplantation. 2019;103(8):1683–1688. doi: 10.1097/tp.0000000000002672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pham H, Rahman A, Majidi A, Waterhouse M, Neale RE. Acute respiratory tract infection and 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(17). 10.3390/ijerph16173020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 87.Amrein K, Papinutti A, Mathew E, Vila G, Parekh D. Vitamin D and critical illness: what endocrinology can learn from intensive care and vice versa. Endocr Connect. 2018;7(12):R304–Rr15. doi: 10.1530/ec-18-0184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Han JE, Jones JL, Tangpricha V, Brown MA, Brown LAS, Hao L, et al. High dose vitamin D administration in ventilated intensive care unit patients: a pilot double blind randomized controlled trial. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2016;4:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jcte.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ginde AA, Brower RG, Caterino JM, Finck L, Banner-Goodspeed VM, Grissom CK, et al. Early high-dose vitamin D(3) for critically ill, vitamin D-deficient patients. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(26):2529–2540. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Shneider A, Kudriavtsev A, Vakhrusheva A. Can melatonin reduce the severity of COVID-19 pandemic? Int Rev Immunol. 2020;39(4):153–162. doi: 10.1080/08830185.2020.1756284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Riegler LL, Jones GP, Lee DW. Current approaches in the grading and management of cytokine release syndrome after chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2019;15:323–335. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.s150524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Staedtke V, Bai RY, Kim K, Darvas M, Davila ML, Riggins GJ, Rothman PB, Papadopoulos N, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Zhou S. Disruption of a self-amplifying catecholamine loop reduces cytokine release syndrome. Nature. 2018;564(7735):273–277. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0774-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Vogelstein JT, Powell M, Koenecke A, Xiong R, Fischer N, Huq S, et al. Alpha-1 adrenergic receptor antagonists for preventing acute respiratory distress syndrome and death from cytokine storm syndrome. ArXiv. 2020.

- 94.Konig MF, Powell M, Staedtke V, Bai RY, Thomas DL, Fischer N, Huq S, Khalafallah AM, Koenecke A, Xiong R, Mensh B, Papadopoulos N, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Vogelstein JT, Athey S, Zhou S, Bettegowda C. Preventing cytokine storm syndrome in COVID-19 using α-1 adrenergic receptor antagonists. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(7):3345–3347. doi: 10.1172/jci139642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]