Abstract

The Covid-19 pandemic has intensified the debate among optimists, pessimists, and centrists about whether the world economic order is undergoing a fundamental change. While optimists foresee the continuation of economic globalization after the pandemic, pessimists expect localization instead of globalization, given the pandemic’s structural negative consequence on the world economy. By contrast, the centrists anticipate a “U-shaped” recovery, where Covid-19 will not kill globalization but slow it down. The three existing perspectives on Covid-19’s impact on the economic globalization are not without merit, but they do not take sufficient temporal distance from the ongoing issue. This article suggests employing the historical perspective to expand the time frame by examining the rise and fall of economic globalization before and after the 2008 global financial crisis. The authors argue that economic globalization has been in transition since the 2008 financial crisis, and one important but not exclusive factor to explain this change is the evolving US–China economic relationship, from symbiotic towards increasingly competitive. The economic restructuring in US and China has begun after both countries weathered the 2008 crisis and gained momentum since the outbreak of trade war and Covid-19. The article investigates this trend by distinguishing different types of production activities, and the empirical results confirm that localization and regionalization have been filling the vacuum of economic globalization in retreat in the last decade.

Keywords: Globalization, Regionalization, US–China relations, World economic order, Covid-19

Introduction

After the White House published the Trump administration’s first National Security Strategy (NSS) report in 2017, many analysts anticipated that it represented a significant shift in America’s China policy [42, 44]. Indeed, the great power competition between Washington and Beijing has been intensified since then. After Trump announced a series of tariff plans on Chinese goods and US–China trade disputes rapidly escalated to an unprecedented level in 2018, many observers remarked that they were fundamentally driven by the increasingly competitive US–China relationship and that the negative consequences of a trade war could spill over into other domains such as technology, military, and ideology [47, 59]. After Trump declared that America must win the race for 5G and the US government decided its ban on Huawei in 2019, commentators regarded it as a technology cold war and the prelude to the US–China new cold war, which would probably give rise to the disintegration of the existing world order [28, 68]. As the tension and competition intensified, both sides seemingly reached a stalemate, and neither deviated from their course. The US–China rivalry has led to more serious concerns over the end of economic globalization and its negative impact on both American and Chinese economies as well as the global economy at large.

Worse still, after the outbreak of the Coronavirus disease (Covid-19) in December 2019, people who had expected transnational cooperation in the face of the threat to global health were disappointed to find that the conspiracy theories and blame games further intensified the competition of governance models between Washington and Beijing. Despite China’s prompt and effective response to the Covid-19, the Chinese government’s policies and measures have been, to a great extent, perceived by the American counterpart as an overwhelming state with strong capability of censorship and control in contrast to a penetrated society with limited autonomy. The Trump administration proclaimed that “as demonstrated by the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) response to the pandemic, Americans have more reason than ever to understand the nature of the regime in Beijing and the threats it poses to American economic interests, security, and values” [53]. Therefore, the White House released the United States Strategic Approach to the People’s Republic of China to detail a whole-of-government strategy to deal with China’s challenge and protect America’s interests [52]. By contrast, the Chinese leadership not only criticized the American counterpart’s scapegoating China for its own failure in coping with the pandemic but also endeavored to set China a strong example for successfully combating Covid-19 by the lengthy white paper China’s Action to Fight the Covid-19 [67]. Similar to the situation after the 2008 global financial crisis, China once again seemed to be more confident with its model of governance as an alternative to the Western liberal model in terms of crisis management [15]. In a nutshell, the Covid-19 pandemic has added more fuel to the fire by further advancing the US–China divergence and competition, thereby giving rise to the accelerated spiral deterioration of the bilateral relationship.

The Covid-19 pandemic is undoubtedly bringing a devastating blow for the global economy, according to World Bank’s report Global Economic Prospects in June 2020 [63], but how it will influence the trajectory of economic globalization is not without controversy. The article attempts to explore what impacts Covid-19 would have on the world economic order in the context of US–China competition. Will economic globalization recover and proceed soon after the world weathers the Covid-19 crisis? Or will the US–China rivalry and the Covid-19 pandemic lead to more regional or even local (national) production? Though it is difficult to make any precise prediction in the midst of an unfolding event, it is not difficult to find optimists, pessimists and centrists of economic globalization amid the current crisis. While optimists foresee the continuation of globalization after the pandemic, pessimists expect localization instead of globalization, given the pandemic’s structural negative consequence on the world economy. By contrast, the centrists anticipate a “U-shaped” recovery, where Covid-19 will not kill globalization but slow it down. The three existing perspectives are not without merit, but the authors do not take the three scenarios as equally likely.

More importantly, the authors understand the difficulty of dealing with a present and evolving issue like the world economic order under the great power politics and the Covid-19 pandemic. Therefore, the authors suggest employing the historical perspective that enables us to study particular moments, events, and critical junctures in the context of broader movements of historical processes. Specifically, the article expands the time frame by examining the rise and fall of economic globalization before and after the 2008 global financial crisis and considers the particular impact of the Covid-19 pandemic in the historical process.

Our article has two key findings. First, the authors argue that economic globalization has been in transition since the 2008 financial crisis and that one important but not exclusive factor in explaining this change is the evolving US–China economic relationship, from symbiotic towards increasingly competitive. The economic restructuring in US and China has begun after both countries weathered the 2008 crisis and gained momentum since the outbreak of trade war and Covid-19. Second, the authors also find that localization and regionalization have been filling the vacuum of globalization in retreat in the process, which provides us a better understanding, or at least a reasonable conjecture, of the potential long-term impact of the pandemic on the world economic order.

The article begins with a brief review of the contending views on economic globalization and discusses the historical perspective to explore the changing dynamics of world economic order. Then the authors will examine how economic globalization evolves along with the US–China economic relationship in the new millennium. Based on the above analysis, the article further explores the alternative forms of production and trade in more depth and situate the impact of the US–China tariffs and the Covid-19 pandemic on the world economic order in the general trend. Finally, the article summarizes the main points and makes some suggestions for further research.

Contending Views on the Economic Globalization and the Historical Perspective

Pundits and policymakers have described the emerging world order in a variety of ways: “a world without superpowers,” “G-zero world,” “no-one’s world,” “multiplex,” “multipolar,” and so on [1, 5, 7, 12, 31]. If the 2008 global financial crisis is the prelude of the changing world order, US–China competition and Covid-19 definitely speed up the tempo. Kissinger even suggests that the Covid-19 pandemic will forever alter the world order [30]. This article focuses on the economic dimension and discusses what the world economic order would be like.

Economic globalization has sped up to an unprecedented pace since the 1980s and swept almost every corner of the world in the past few decades. While the two major crises—the 1997 Asian financial crisis and the 2008 global financial crisis—have corrected the hyper-globalist view that globalization is an irreversible and formidable project, liberal institutionalists still hold a firm belief that the world economic order based on the liberal, rule-based, and multilateral principle is resilient and durable [23, 24]. However, after Trump took office, his attacks on the liberal world order, including but not limited to trade, multilateralism, international law, environmental protection, and human rights, have fundamentally questioned its survival [25]. With the Covid-19 soaring around the world, three contending views—optimists, pessimists, and centrists—could be identified within the existing literature on economic globalization. This section offers a critical review of the existing views and suggests that the historical perspective could be useful in understanding the trajectory of economic globalization.

First, the globalists still take a sanguine view of economic globalization in the near future. Optimists argue that, despite a certain degree of disruption to the international economic order during the pandemic, it is expected to return to the pre-crisis trajectory soon after the pandemic is contained. Economic globalization will continue once the market weathers the shock of the virus and the economic recession is ended. The most important reason is that no prior shocks, including epidemics such as the 2002–2004 SARS outbreak, 1968 H3N2 pandemic (Hong Kong flu), 1958 H2N2 pandemic (Asian flu), and 1918 H1N1 pandemic (Spanish flu), have done structural damage to the affected economies and fundamentally changed the nature of international economic order [9, 27]. Since statistics show that economic recovery from the prior pandemics was quick (i.e., V-shaped), economic recovery from Covid-19 will be more similar than different this time, as social distancing nowadays is not dramatically different from then [37]. Furthermore, optimists, especially the liberal internationalists, also strive to argue that Covid-19 will not kill globalization but reveal no one can go it alone. Covid-19 will make political leaders more aware that international cooperation is critical for effective mass testing and treatment for the virus, and then countries are expected to work together to improve production and distribution [18, 26].

Second, in contrast to the optimists, pessimists expect localization instead of globalization given the pandemic’s structural negative consequence on globalization. They have little hope of effective international cooperation under the current structure (underlying anarchy) of global governance on the one hand [40] and believe that Covid-19 will have significant and sustaining structural damage to the world economy on the other [63]. For instance, according to a recent poll from Reuters, nearly half of the economists expect a U-shaped recovery, more than any other option such as V-shaped or L-shaped [46]. Paulson [41] suggests that Covid-19 has triggered the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression and foresees a future that “belongs to the techno-nationalists” owing to “Beijing’s emphasis on indigenisation and Washington’s on relocating supply chains and sequestering technology.” In this scenario, pessimists view the Covid-19 crisis as a systemic and long-lasting crisis that is even more severe than the 2008 global financial crisis and, to a great extent, comparable to the Great Depression. The virus’s structural negative effect, as well as the lack of international coordination and cooperation, will put an end to this round of economic globalization. Given this, we should expect a wave of economic nationalism and localization to replace globalization. While both inter-regional and intra-regional production and trade will decrease, the share of domestic economic activities will rise.

Third, the centrists, as the name suggests, stand somewhere in the middle: The world economy will recover anyway, but not as quickly as optimists anticipate and as hard-hit as pessimists foresee. In this scenario, it is tempting to compare the current Covid-19 crisis to the 2008 global financial crisis: both have produced extraordinary volatility in financial markets and caused far-reaching economic repercussions. It is argued that Covid-19 will not kill globalization, but globalization will slow down after all. Many terms have been coined to describe this picture. For example, Zheng [69] suggests that economic globalization will not simply ebb but return to “limited globalization,” similar to the one before the 1980s. Bakas coins the term “slowbalisation” to describe the faltering globalization in the last few years [48]. Regardless of the terms, the new normal of economic globalization essentially has two implications. First, it implies continued integration of the global economy but albeit at a significantly slower pace. Second, “slowbalization will lead to deeper links within regional blocs” [49]. As Covid-19 has exposed the dangers of relying on any one country for needed inputs or final products, it is important for countries to regionalize their supply chains and companies to diversify their trading partners in the face of a considerable period of slower economic growth. In a nutshell, Covid-19 will not put an end to economic globalization; rather, it will promote other forms of economic integration such as regionalization.

While the three perspectives are not without merit, especially insofar as they propose different scenarios of how we could grasp the potential impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the economic globalization, the three scenarios should not be treated as equally likely. Specifically, it is very unlikely that, as the optimists expect, a quick recovery of the world economy and economic globalization will happen in a few months. It is not difficult to draw this conclusion if we carefully read China as a typical case study. Even if China was the first country to impose stringent lockdown measures, the first to lift them, and the first to get some economic activities back on track, the Chinese economy is unlikely to return to normalcy until the last quarter of 2020 [70]. More importantly, there are good reasons to be skeptical that other countries will and can follow China’s model of containing the virus. For instance, Normand suggests that “the U.S. and global economy might exhibit more U than V-shaped characteristics as occurred after the global financial crisis, so will likely fail to recoup its 2020 first half output loss even by the end of 2021” [27]. Under the circumstance, the Covid-19 pandemic is expected to bring sustained disruptions to global trade, supply chains, and investment flows.

Despite the above seemingly plausible analysis, we have to admit that it is currently difficult to draw any firm conclusion and prediction in the midst of an unfolding event, as the future is undeniably influenced by many uncertain factors. In this case, the authors suggest that, if we employ the historical perspective to take a longer-run view, we can get a more comprehensive and clearer picture of how economic globalization gains and loses momentum. It helps us to explore the particular impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the world economic order and find which scenario to be more likely afterward.

However, it is worth clarifying the historical perspective herein before we embark on the historical analysis, as IR scholars have examined history in different ways and deployed history for different purposes [8, 10, 11, 20, 33, 57]. The authors do not intend to add further fuel to the existing debates among the various historical perspectives [6], but to state clearly that they have referred the aforementioned historical perspective in this article to a research method. This historical method does not simply mean looking back to history, which is of course necessary, but more importantly, it studies particular moments, events, and critical junctures in the context of broader movements of historical processes [34]. As Ziblatt [71:3] suggests, “temporal distance—moving out from single events and placing them within a longer time frame—can also expose previously undetectable social patterns.” Like archaeologists working too close to the ground, we may fail to see the trajectory of economic globalization if we do not take sufficient temporal distance from the Covid-19 crisis. All three existing perspectives on Covid-19’s impact on the world economy and globalization have such a shortcoming, and this article strives to highlight this crucial issue. Therefore, the authors propose to shift our perspective and examine the trajectory of globalization within a longer time frame. The length of the time frame is of course not fixed and hinges on the object of study. In this research, the authors propose a range of twenty years to examine the continuities and changes in the cycle of globalization and deglobalization in the new millennium. The longer-run view is helpful in discerning not only the important pattern of a historical process but also the particular impact of a historical event such as an economic crisis and a deadly pandemic. We can probably gain a better understanding of the post-pandemic world economic order if we take Covid-19’s impact into account within the historical dynamics of economic globalization.

The Ebb and Flow of Economic Globalization before and after the 2008 Crisis

The section examines the turning points as well as the ebb and flow in the evolution of economic globalization in the new millennium. As America and China are two of the most important economies and their economic relationship is critically important for globalization in the twenty-first century, the authors will read it as a typical case study to examine how economic globalization evolves along with the bilateral economic relationship.

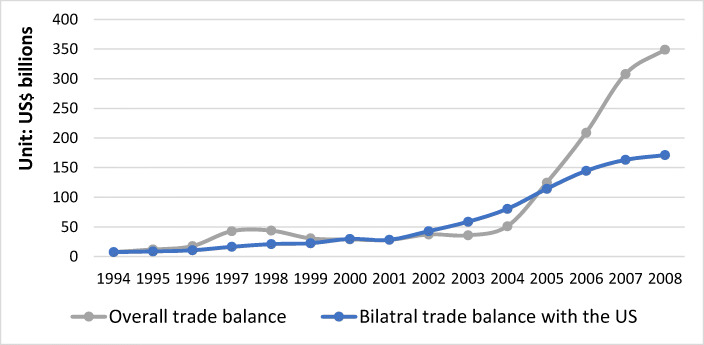

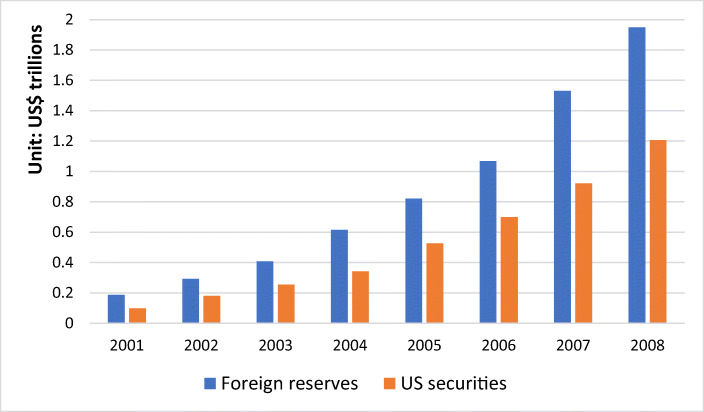

Before the 2008 financial crisis, the US–China economic relationship was more complimentary and cooperative in nature. America and China essentially formed a symbiotic relationship: the US consumed China’s cheap exports, paying China in dollars, and China held US dollars and bonds, in fact, lending money to the US. Essentially, China’s export-driven growth and its accumulation of dollar reserves and US debts were closely intertwined with the dollar hegemony in the international monetary system and America’s increasing over-drafting consumption and trade deficit [16, 21, 22]. Some observers even perceived the two economies as conjoined twins, “ChinAmerica” [29] or “Chimerica” [17], which was based on Chinese export-led growth and American overconsumption. The US–China symbiotic economic relationship was demonstrated in Figs. 1 and 2. Figure 1 shows China’s overall trade surplus and a bilateral trade surplus with the US from 1994 to 2008. After its accession to the WTO membership in 2001, China’s position in global trade and payments substantially changed. Its trade surplus rose sharply from 2003, as did its bilateral trade surplus with the US. Figure 2 reveals the corresponding dramatic increase in China’s holdings of foreign reserves and US securities from 2001 to 2008. It is estimated that about two-thirds of China’s reserves were held in the form of dollar debt [58].

Fig. 1.

China’s overall trade surplus and a bilateral trade surplus with the US, 1994–2008. Source: IMF Direction of Trade Statistics (March 2020 Edition), https://stats2.digitalresources.jisc.ac.uk/?Dataset=DOTS&ShowOnWeb=true&Lang=en

Fig. 2.

China’s foreign reserves and holdings of US securities, 2001–2008. Source: IMF International Financial Statistics (March 2020 Edition), https://stats2.digitalresources.jisc.ac.uk/?Dataset=DOTS&ShowOnWeb=true&Lang=en

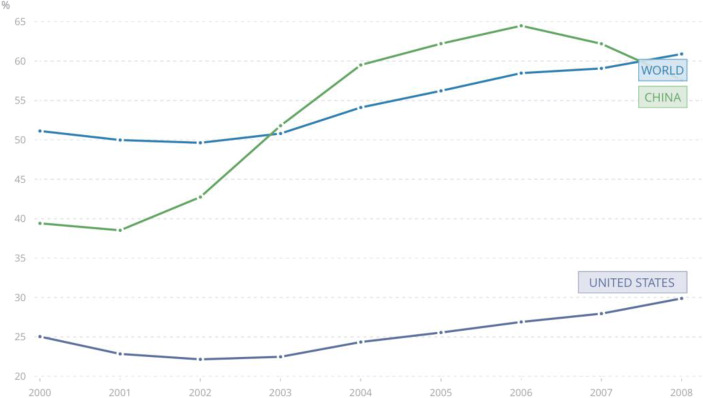

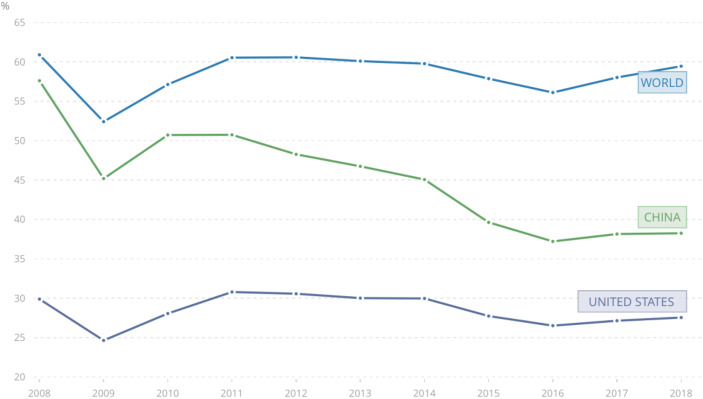

Therefore, after its accession to the WTO membership in 2001, China developed its complementary economic relationship with the US and increasingly integrated into the world economy. The US–China economic relationship was one of the most important engines of economic globalization before 2008. As Fig. 3 demonstrates, the world trade as a percentage of the world GDP was generally on the rise during the golden period of economic globalization; the ratio of China’s international trade to GDP climbed up from around 40% to more than 60% quickly in the process, and the US experienced slow but steady growth as well after the economic downturn in 2001.

Fig. 3.

Trade as % of GDP: World, the US, and China, 2000–2008. Source: World Bank Data

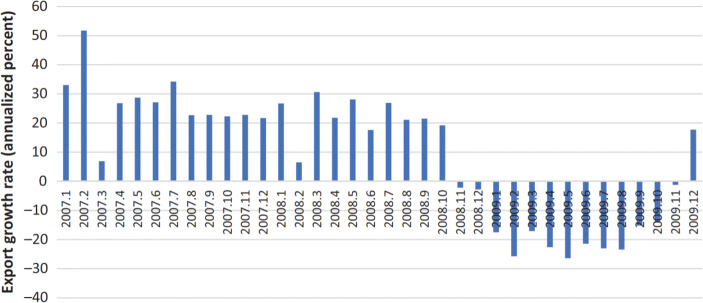

However, with the benefit of hindsight, the 2008 global financial crisis marked an important turning point in the trajectory of economic globalization. The crisis exposed China’s severe vulnerability in the symbiotic economic relationship with the US. Figure 4 shows while China’s exports grew by an average of more than 20% month-by-month for most of 2008, they fell dramatically by 2.2% in November and experienced considerable negative growth in 2009, which made China’s political elites more aware of the disadvantages of over-dependence on the US market and dollar. Under the circumstance, the Chinese government rolled out a series of ad hoc rescue policies, including the mega fiscal stimulus plan and expansionary monetary policy in 2009. Though the Hu-Wen administration recognized the unsustainability of China’s export-driven growth model, the Chinese leadership placed priority on growth and stability and put domestic economic reforms in the secondary place in the face of the crisis.

Fig. 4.

China’s monthly export growth rate, 2007–2009. Source: National Bureau of Statistics, People’s Republic of China, https://data.stats.gov.cn/easyquery.htm?cn=A01

More importantly, after both countries weathered the crisis, the US–China economic relationship became increasingly competitive. This is a result of a variety of factors, including China’s domestic economic reforms and growing ambition in global economic governance [60]. It is worth noting that after he consolidated and centralized power within China’s political system, Xi Jinping was more confident and capable in carrying out substantial reforms in both domestic and international domains.

Domestically, Xi clearly aimed to change China’s growth model to one driven by domestic consumption and innovation, instead of inexpensive exports and low-efficiency investments [65]. Not only did China demonstrate its plan to steer away from labor-intensive industries to high-tech manufacturing, it also showed its ambition to become a global leader in innovation by releasing the national blueprint “Made in China 2025.” The guideline pledges that “China will be an innovative nation by 2020, an international leader in innovation by 2030, and a world powerhouse of scientific and technological innovation by 2050” [51].

Internationally, China gradually became a proactive participant in global economic governance under the Xi administration. China put forward the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and established the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) to fund infrastructural projects in Asia. Though China claimed that both BRI and AIIB had a supplementary nature to the pre-existing institutions such as World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF), many consider them as China’s challenge to the pillars of the US-dominated liberal world order. The stories of how Beijing built an alliance to create AIIB in the face of Washington’s opposition and how Washington forged the Indo-Pacific alliance to contain BRI’s increasing influence demonstrate the contestation between the US and China for leadership in global economic governance [14, 45].

With China’s continued economic restructuring and industrial policy, China was upgrading its exports from labor-intensive to more capital and technology-intensive products, which caused more competition with products manufactured in advanced/industrialized countries. China’s attempt to expand its economic and financial influence regionally and internationally further intensified the competition. This growing competitive nature of the US–China economic relationship after the 2008 global financial crisis has also been captured by empirical studies. For instance, Kwan [32] finds that owing to China’s increasingly sophisticated trade structure in recent years, China’s complementarity with industrialized countries (the United States, Japan, and Germany) has been diminishing, and competition with newly industrializing economies (India and Indonesia) and resource countries (Australia and Russia) has also been decreasing.

While the US–China symbiotic economic relationship added momentum to economic globalization before 2008, the increasingly competitive nature of the bilateral economic relationship slowed it down, if not to say reversing the trend. As Fig. 5 suggests, international trade was severely hit and then recovered from the 2008 global financial crisis, but the world trade as a percentage of world GDP did not continue to grow after 2011. During the period from 2011 to 2018, China’s trade-to-GDP ratio experienced a significant decline, from more than 50% down to less than 40%, compared to America’s slow and slight counterpart, with no more than 5% decrease. This corresponds with the aforementioned cases in which China was more proactive in adjusting its economic relationship with the US and its way to participate in economic globalization after the 2008 global financial crisis.

Fig. 5.

Trade as % of GDP: World, the US, and China, 2008–2018. Source: World Bank Data

Now we can gain a better understanding that economic globalization has been in transition since the 2008 financial crisis. The world economy experienced a U-shaped recovery after the 2008 crisis, and some fundamental changes in the nature of globalization have taken place since then. Economic globalization reached the turning point in the 2008 crisis, and the aforementioned slowbalization is quite accurate to describe the subsequent development, if not to say reversed globalization. One important but not exclusive factor in explaining this change is the evolving US–China economic relationship, from symbiotic towards increasingly competitive. This is, of course, not to say that the US and China have no or little economic complementarity presently. Economic indicators such as US–China bilateral trade volume and China’s holdings of US Treasury bonds suggest that the two countries are still very important economic partners to each other. It would be a mistake, or at least too early, to say that the nature of the US–China economic relationship has fundamentally changed at this stage. The emphasis of this section is not on the transformed consequence but on the evolutionary process, in which the US experienced intensified anxiety regarding China’s growing competitiveness. In this sense, it would be easier to understand why several key US government agencies expressed such concerns in 2017 and Trump began to fight a trade war against China after 2018 [55, 56]. Though there is no official data from World Bank for 2019 and 2020 yet, it is plausible to speculate that the global and bilateral trade would further shrink with the US–China tariffs implemented and the outbreak of Covid-19 [4, 64]. While the trade war reveals the risk of manufacturing goods in China for export and highlights the need to deliver the production of some goods elsewhere, the Covid-19 further drives the American government and companies to move US production and supply chain dependency away from China. The following section will further analyze how regional and domestic forms of production and trade developed in the face of slowbalization after the 2008 crisis.

Exploring Globalization, Regionalization, and Localization: Some Empirical Results

The historical perspective has shed light on the ebb and flow of economic globalization along with the evolving US–China economic relationship from symbiotic towards increasingly competitive before and after the 2008 global financial crisis. It suggests that the economic restructuring in US and China has begun after both countries weathered the 2008 crisis and gained momentum since the outbreak of trade war and Covid-19. However, it is worth exploring the economic restructuring in more depth or, put more specifically, to examine the alternative forms of production and trade in the face of globalization in retreat after the 2008 crisis. The authors find that localization and regionalization have been filling the vacuum of globalization in retreat in the slowbalization process.

Before we set out on the journey, we need to distinguish different types of production activities. The authors follow the methodology of Wang et al. to decompose production activities into four types [61]. The first type, purely domestic or localized, is added value produced and the final product consumed at home without involving international trade. The second type, traditional international trade, is an added value produced at home and final product exported for international consumption, such as China’s cloth in exchange for America’s soybeans. The third and fourth types involve intermediate trade and cross-border production. The third is a simple type of global value chain (GVC) when the intermediate product crosses border once for foreign production, such as China’s steel produced for America’s building. The fourth is a complex type of GVC if the intermediate product crosses borders at least twice to produce final export for other countries, such as iPhone’s manufacturing lines [62].

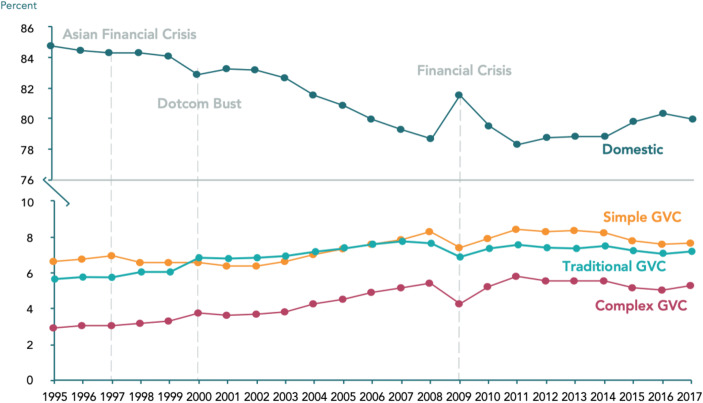

After the decomposition, Fig. 6 demonstrates how the four types of production activities evolved from 1995 to 2017. A few patterns are noteworthy. First, the relative importance of domestic production activities was decreasing before 2008, while the shares of traditional, simple, and complex GVCs were generally increasing. This corresponds with our aforementioned analysis that economic globalization before the 2008 global financial crisis. Moreover, it further demonstrates that economic globalization was, to a larger extent, driven by the complex GVC activities, whose share experienced a faster increase that those of tradition and simple GVCs. Second, after the shape decline of international trade in 2009, all three GVC activities took two years to return to the pre-crisis level, which resonated with the U-shaped recovery of the world economy. Third, the relative importance of domestic production activities was increasing after 2011, while traditional, simple, and complex GVCs was generally decreasing. The decline was the steepest for complex GVC activities, and this once again corresponds with our aforementioned analysis that the 2008 global financial crisis was a watershed and that globalization slowed down subsequently.

Fig. 6.

Four types of production activities as a share of global GDP, 1995–2017. Source: Xin Li, Bo Meng, and Zhi Wang, “Recent patterns of global production and GVC participation,” in World Bank and World Trade Organization, Global Value Chain Development Report 2019, Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group, p. 12

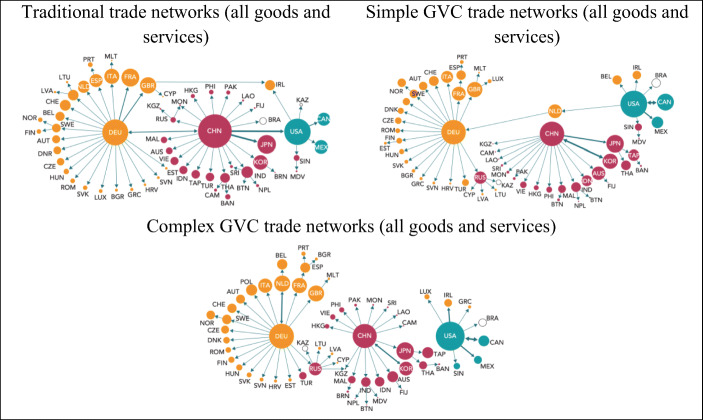

Furthermore, if we more carefully examine the latest data (as of 2017) and visualize the three GVC activities through network analysis, we can find some structural characteristics of the international production networks. First, as shown in the upper-left of Fig. 7, the three hubs of traditional trade networks are Germany, China, and the US, which have important linkages with each other. Second, for both simple and complex GVC trade networks, we can no longer find any important direct linkage between any two hubs. The upper-right of Fig. 7 shows that simple GVC activities are to a great extent concentrated within each of the three regions, except for the US and Germany’s indirect link through the Netherlands. Complex GVC activities are more concentrated among regional trading partners (see the bottom of Fig. 7) [62]. Therefore, a tentative conclusion can be drawn that globalization is in retreat while localization and regionalization are filling the vacuum.

Fig. 7.

Supply hubs of three GVC activities trade networks in 2017. Source: Xin Li, Bo Meng, and Zhi Wang, “Recent patterns of global production and GVC participation,” in World Bank and World Trade Organization, Global Value Chain Development Report 2019, Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group, p. 27

This localized and regionalized nature of the value chain in the last decade has also been captured by some existing empirical research. For instance, Baldwin and Lopez-Gonzalez base their analysis on two latest data sets—the World Input–Output Database (WIOD) and the Trade in Value Added (TiVA) Database—to suggest that the global value chain is no longer accurate to describe the international production network, which is predominantly regional in scope [3]. They provide a strongly supportive argument that “the global production network is marked by regional blocks, what could be called Factory Asia, Factory North America, and Factory Europe” [3]. Their research suggests a transition of international production networks from “Factory World” to regional production systems.

Moreover, McKinsey’s several pieces of research reports confirm that regionalization is restructuring the global value chain. Specifically, it is strongly argued that nearshoring and regionalization of apparel production and trade (that is, production in places like Turkey for the European market and Mexico for the US market) is more profitable today and is likely to become more so in the decade ahead [2]. Global innovations value chains are also found to experience very pronounced shift toward regionalization, given their need for just-in-time sequencing [36]. It is estimated that “the intraregional share of global goods trade has increased by 2.7 percentage points since 2013,” which is considerably driven by the increasing trade flows within the EU-28 and within the Asia-Pacific region [36]. In a nutshell, the empirical results reveal the trend that value chains are becoming more regionalized and less global in the last decade.

Despite the fact that no rigorous study can be possibly conducted on the recent development owing to the lack of complete data, it is plausible for us to speculate that the US–China trade tension and the Covid-19 would make the production and trade networks even more regional and less global. The trend can be analyzed from both the macro-level and the micro-level.

From the macro perspective, as the World Trade Organization (WHO) is on the road to becoming defunct under the Trump administration and the Covid-19 pandemic further represents an unprecedented disruption to the global trade, countries are speeding up to forge regional trade agreements to mediate the trade uncertainty. For example, the US, Mexico, and Canada signed the new free trade agreement, United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA), to replace the old North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in December 2019. The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) negotiations among the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) along with China, Japan, South Korea, India, Australia, and New Zealand advanced to the final stage in 2019. Though India finally decided not to join because of domestic problems, 15 other participating states agreed to forge ahead [39]. The tariff wars and Covid-19 do not, of course, constitute the sole cause of the regionalization project, but they are playing the role of catalyst or accelerator in the process.

From the micro perspective, global trade disruption has impelled companies to revaluate the operational strategy, such as where to place production and locate operations. It becomes more necessary for transnational companies to regionalize and diversify their supply chains in order to cope with the rising risks. For instance, according to the McKinsey Global Surveys in 2018, nearly half of respondents stated that their companies would shift their global footprint in response to the US–China trade tension, and one-quarter said they would invest more in regional and local supply chains [35]. When it came to 2019, according to the surveys by supply chain consultancy QIMA, over 75% of US respondents reported being affected by the US–China tariffs, and 80% of US respondents and 67% for those based in the EU expressed that they had already begun to diversify their supply chains and strengthen their presence in the local regions, or had plans to do so in the near future [43]. The Economist Intelligence Unit recently examines how Covid-19 has impacted and will continue to fundamentally reshape global supply chains, and strongly argue that Covid-19 will fundamentally reshape trade, accelerating the trend towards shortening supply chains [50].

To summarize, the empirical results confirm that while economic globalization continues to slow down, the relative importance of domestic and regional production activities has been on the rise in the last decade. Both the US–China tariff war and the Covid-19 pandemic have exposed the dangers of relying on any one country for needed inputs or final products, which make it increasingly important for countries to regionalize or localize their supply chains and companies to diversify their trading partners in the face of global trade uncertainty. In a nutshell, US–China competition and Covid-19 will not put an end to economic globalization, rather, they will promote other forms of production activities such as regionalization and localization.

Concluding Remarks

The Covid-19 pandemic has intensified the debate about whether the world economic order is undergoing a fundamental change. As Winston S. Churchill once suggested, “the farther backward you can look, the farther forward you are likely to see.” Since optimists, pessimists and centrists can hardly reach a consensus on what the post-Covid-19 world economic order will be like, the authors suggest taking sufficient temporal distance from the temporary ongoing issue. The article has employed the historical perspective to expand the time frame by examining the trajectory of economic globalization in the new millennium and consider the particular impact of the Covid-19 pandemic in the historical process. It emphasizes the continuities and changes in the cycle of globalization and deglobalization. The longer-run view is helpful in discerning important patterns and situating a crisis’s particular impact in the more general trend, so that we can get a better understanding of the post-Covid-19 world economic order.

The article has argued that the world economy experienced a U-shaped recovery after the 2008 crisis, and some fundamental changes in the nature of economic globalization have taken place in the past decade. Slowbalization is quite accurate to describe the new normal of economic globalization, and one important but not exclusive factor to explain this change is the evolving US–China economic relationship, from symbiotic towards increasingly competitive. More importantly, the article makes a contribution by examining the different forms of production and trade activities in the past decade. The empirical results reveal that localization and regionalization have been filling the vacuum of economic globalization in retreat in the last decade. As O’Sullivan [38] suggest in his book, The Levelling: What’s Next After Globalisation, globalization is fading away behind us, and we are embracing the emerging multipolar world, which is dominated by at least three large regions: North America, Europe, and a China-centric Asia. The article confirms this point and suggests that the US–China tariff war and the Covid-19 pandemic are not the beginning but the accelerators or catalysts of this more general trend.

The article presents a more nuanced study of economic globalization in the last two decades and provides a perspective to understand the impact of the US–China tariff war and the Covid-19 pandemic on the world economic order. Our article definitely invites some more future research. First, though the centrist’s view of a U-shaped world economy and slowbalization seems to be more likely, we still need to keep track of how things really unfold. As both the US–China rivalry and the Covid-19 pandemic is still ongoing, the only certainty is that nothing is certain for the post-Covid-19 world economic order. If it is really so, we also need to more rigorously study the transformation of the world economy and the extent to which economic globalization is slowed down by the pandemic, after the economic data becomes available.

Second, it is worth noting that neither the US–China competition nor the Covid-19 pandemic constitutes the sole cause of the global transformations of production and trade looming ahead. Though some empirical results have revealed that economic globalization is slowing down and regionalization is filling the vacuum, we are not yet fully aware of the complex dynamics and the underlying mechanisms. Other forces that drive regionalization include but are not limited to new technologies, changing global consumption patterns, as well as the dynamic benefits and costs of location decisions [36]. It is probably necessary to probe into different industries in different countries and regions [66]. It is also necessary to combine quantitative and qualitative methods to explore the decisions made by businesses regarding where to place production and locate operations. The sectoral and dynamic analyses of value chain transformation are likely to be very important in the near future.

Last but not least, if we would like to more specifically examine how regionalization evolves over the past few years, we should adopt some different methods to decompose the international production and trade. For example, we can pay special attention to whether added value produced is within a single country, within a single region or covering at least two regions and thus separate different networks of value chain production into three types—domestic value chain (DVC) production, regional value chain (RVC) production and global value chain (GVC) production [19]. Generally speaking, the more RVC production, the higher the degree of regional economic integration, whereas the more GVC production, the higher the degree of economic integration into the global economy [62]. Then we are able to more precisely calculate the relative importance of regionalization by measuring and comparing shares of DVC, RVC, and GVC based on data from WIOT [13, 54]. Unfortunately, WIOT’s most recent release is the November 2016 version. We need to wait a couple of years to get access to the data as of 2020, if we intend to analyze how regionalization evolves in the context of the US–China rivalry and Covid-19.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge funding support from two research grants by Fujian Federation of Social Science Circles (grant number: FJ2018C025) and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (grant number: 20820181018). The authors are also very grateful to the School of International Relations at Xiamen University for providing outstanding facilities for research, including but not limited to the office, the library and the shower room.

Biographies

Zhaohui Wang

is Assistant Professor at the School of International Relations and the Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Xiamen University, China. His research lies in the fields of Politics and International Relations, Political Economy, China Studies and Southeast Asian Studies. His academic papers have appeared in Globalizations, Journal of Contemporary China, Asian Survey, Asian Studies Review among others.

Zhiqiang Sun

is a postgraduate student at the School of International Relations & Public Affairs, Fudan University, China. His research lies in the fields of International Relations, Comparative Politics and Southeast Asian Studies. His academic papers have been published in Comparative Political Studies, The Journal of State Governance, Nanjing University Asia-Pacific Review among others.

Contributor Information

Zhaohui Wang, Email: zhaohuiwang@xmu.edu.cn.

Zhiqiang Sun, Email: zqsun19@fudan.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Acharya A. The end of American world order. Cambridge: Polity; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersson, Johanna, Achim Berg, Saskia Hedrich, and Karl-Hendrik Magnus. 2018. Is apparel manufacturing coming home? Nearshoring, automation, and sustainability – Establishing a demand-focused apparel value chain. McKinsey & Company, October 11. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/is-apparel-manufacturing-coming-home. Accessed 7 September 2020.

- 3.Baldwin, Richard and Javier Lopez-Gonzalez. 2013. Supply-chain trade: A portrait of global patterns and several testable hypotheses. NBER working paper no. 18957, April 2013. Retrieved from https://www.nber.org/papers/w18957. Accessed 7 September 2020.

- 4.Bekkers, Eddy and Sofia Schroeter. 2020. An economic analysis of the US-China trade conflict. WTO staff working paper ERSD-2020-04, march 19. Retrieved from https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/reser_e/ersd202004_e.pdf. Accessed 7 September 2020.

- 5.Bremmer I. Every nation for itself: What happens when no one leads the world. New York: Portfolio Penguin; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burrow J. A history of histories: Epics, chronicles, and inquiries from Herodotus and Thucydides to the twentieth century. New York: Vintage; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buzan B. The inaugural Kenneth N. waltz annual lecture a world order without superpowers: Decentred globalism. International Relations. 2011;25(1):3–25. doi: 10.1177/0047117810396999. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buzan B, Lawson G. The global transformation: History, modernity and the making of international relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carlsson-Szlezak, Philipp, Martin Reeves and Paul Swartz. 2020. What coronavirus could mean for the global economy. Harvard Business Review, March 3. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2020/03/what-coronavirus-could-mean-for-the-global-economy. Accessed 7 September 2020.

- 10.Carr EH. What is history? New York: Vintage; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cox R. Gramsci, hegemony and international relations: An essay in method. Millennium: Journal of International Studies. 1983;12(2):162–175. doi: 10.1177/03058298830120020701. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clegg J. China’s global strategy: Towards a multipolar world. New York: Pluto Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Constantinescu, Cristina, Aaditya Mattoo, and Michele Ruta. 2017. Trade developments in 2016: Policy uncertainty weighs on world trade. World Bank Group, February 21. Retrieved from https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/228941487594148537/trade-developments-in-2016-policy-uncertainty-weighs-on-world-trade. Accessed 7 September 2020.

- 14.Corre, Philippe Le. 2015. Dividing the west: China’s new investment bank and America’s diplomatic failure. Brookings, March 17. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2015/03/17/dividing-the-west-chinas-new-investment-bank-and-americas-diplomatic-failure. Accessed 7 September 2020.

- 15.Deva, Surya. 2020. With coronavirus crisis, China sees a chance to export its model of governance. South China Morning Post, March 29. Retrieved from https://www.scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3077320/coronavirus-crisis-china-sees-chance-export-its-model-governance. Accessed 7 September 2020.

- 16.Eichengreen B. Global imbalances and the lessons of Bretton woods. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferguson N, Schularick M. “Chimerica” and the global asset market boom. International Finance. 2007;10(3):215–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2362.2007.00210.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Furman, Jernej. 2020. Coronavirus hasn’t killed globalisation – It proves why we need it. The Conversation, may 6. Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/coronavirus-hasnt-killed-globalisation-it-proves-why-we-need-it-135077. Accessed 7 September 2020.

- 19.Hanzl-Weiss, Doris, Sandra M. Leitner, Robert Stehrer, and Roman Stöllinger. 2018. Global and regional value chains: How important, how different? The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies – Wiiw research report no. 427, April 2018. Retrieved from https://wiiw.ac.at/global-and-regional-value-chains-how-important-how-different-p-4522.html. Accessed 7 September 2020.

- 20.Hobson JM, Lawson G. What is history in international relations? Millennium: Journal of International Studies. 2008;37(2):415–435. doi: 10.1177/0305829808097648. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hung H-f. America’s head servant? The PRC’s dilemma in the global crisis. New Left Review. 2009;60:5–25. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hung H-f. China: Savior or challenger of the dollar hegemony? Development and Change. 2013;44(6):1341–1361. doi: 10.1111/dech.12063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ikenberry J. The rise of China and the future of the west: Can the liberal system survive? Foreign Affairs. 2008;87(1):23–37. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ikenberry J. Liberal leviathan: The origins, crisis, and transformation of the American world order. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ikenberry J. The plot against American foreign policy: Can the liberal order survive? Foreign Affairs. 2017;96(3):2–9. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ikenberry J. The next liberal order: The age of contagion demands more internationalism, not less. Foreign Affairs. 2020;99(4):133–142. [Google Scholar]

- 27.J.P. Morgan. 2020. What will the recovery look like from the COVID-19 recession? April 10. Retrieved from https://www.jpmorgan.com/global/research/2020-covid19-recession-recovery. Accessed 7 September 2020.

- 28.Jing, Meng and Zen Soo. 2019. Tech cold war: How Trump’s assault on Huawei is forcing the world to contemplate a digital iron curtain. South China Morning Post, May 26. Retrieved from https://www.scmp.com/tech/big-tech/article/3011700/tech-cold-war-how-trumps-assault-huawei-forcing-world-contemplate. Accessed 7 September 2020.

- 29.Jones H. ChinAmerica: The uneasy partnership that will change the world. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kissinger, Henry A. 2020. The coronavirus pandemic will forever alter the world order. The Wall Street Journal, April 3. Retrieved from https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-coronavirus-pandemic-will-forever-alter-the-world-order-11585953005. Accessed 7 September 2020.

- 31.Kupchan CA. No One’s world: The west, the rising rest, and the coming global turn. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kwan, Chi Hung. 2013. Trade structure of China becoming more sophisticated: Changing complementary and competitive relationships with other countries. Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry, June 5. Retrieved from https://www.rieti.go.jp/en/china/13060502.html. Accessed 7 September 2020.

- 33.Lebow RN. Forbidden fruit: Counterfactuals and international relations. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mann M. The social sources of power: Volume 1, a history of power from the beginning to AD 1760. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 35.McKinsey & Company. 2018. Economic conditions snapshot, September 2018: McKinsey global survey results. September 27. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/economic-conditions-snapshot-september-2018-mckinsey-global-survey-results. Accessed 7 September 2020.

- 36.McKinsey & Company. 2019. Globalization in transition: The future of trade and value chains. January 16. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/innovation-and-growth/globalization-in-transition-the-future-of-trade-and-value-chains. Accessed 7 September 2020.

- 37.Noy, Ilan. 2020. Past pandemics show how coronavirus budgets can drive faster economic recovery. The Conversation, May 8. Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/past-pandemics-show-how-coronavirus-budgets-can-drive-faster-economic-recovery-137775. Accessed 7 September 2020.

- 38.O’Sullivan M. The Levelling: What’s next after globalization. New York: Public Affairs; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parkin, Benjamin and John Reed. 2019. India decides not to sign China-backed pan-Asian trade deal. Financial Times, November 4. Retrieved from https://www.ft.com/content/530ec540-ff12-11e9-b7bc-f3fa4e77dd47. Accessed 7 September 2020.

- 40.Patrick S. When the system fails: COVID-19 and the costs of global dysfunction. Foreign Affairs. 2020;99(4):40–50. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paulson, Henry. 2020. Save globalisation to secure the future. Financial Times, April 17. Retrieved from https://www.ft.com/content/da1f38dc-7fbc-11ea-b0fb-13524ae1056b. Accessed 7 September 2020.

- 42.Pifer, Steven. 2018. Assessing the U.S. National Security Strategy. Brookings, January 25. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/testimonies/assessing-the-u-s-national-security-strategy. Accessed 7 September 2020.

- 43.QIMA. 2019. Trade war: US demand for China-based inspections drops by −13% as other regions reap benefits. QIMA 2019 Q3 Barometer. Retrieved from https://www.qima.com/qima-news/2019-q3-barometer-sourcing-regions-reap-benefits. Accessed 7 September 2020.

- 44.Rolin, Josh. 2017. Trump’s National Security Strategy marks a hawkish turn on China. The Washington Post, December 18. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/josh-rogin/wp/2017/12/18/trumps-national-security-strategy-marks-a-hawkish-turn-on-china. Accessed 7 September 2020.

- 45.Saeed M. From the Asia-Pacific to the indo-Pacific: Expanding Sino-US strategic competition. China Quarterly of International Strategic Studies. 2017;3(4):499–512. doi: 10.1142/S2377740017500324. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sarkar, Shrutee. 2020. U.S. economy likely set for U-shaped recovery after deep rut: Reuters poll. Reuters, April 21. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-economy-poll/u-s-economy-likely-set-for-u-shaped-recovery-after-deep-rut-reuters-poll-idUSKCN2231V6. Accessed 7 September 2020.

- 47.Schneider-Petsinger, Marianne, Jue Wang, Yu Jie, and James Crabtree. 2019. US-China strategic competition: The quest for global technological leadership. Chatham house research paper, November 7. Retrieved from https://www.chathamhouse.org/publication/us-china-strategic-competition-quest-global-technological-leadership. Accessed 7 September 2020.

- 48.The Economist. 2019. Globalisation has faltered. January 24. Retrieved from https://www.economist.com/briefing/2019/01/24/globalisation-has-faltered. Accessed 7 September 2020.

- 49.The Economist. 2020. Has covid-19 killed globalisation? May 14. Retrieved from https://www.economist.com/leaders/2020/05/14/has-covid-19-killed-globalisation. Accessed 7 September 2020.

- 50.The Economist Intelligence Unit. 2020. The great unwinding: Covid-19 and the regionalisation of global supply chains. Retrieved from https://www.eiu.com/n/campaigns/the-great-unwinding-covid-19-supply-chains-and-regional-blocs. Accessed 7 September 2020.

- 51.The State Council of People’s Republic of China. 2016. The state council publishes the guideline for China’s innovation-driven development strategy. Xinhua, May 19. Retrieved from http://www.xinhuanet.com//politics/2016-05/19/c_1118898033.htm. Accessed 7 September 2020.

- 52.The White House. 2020. United States Strategic Approach to the People’s Republic of China. May 20. Retrieved from https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/U.S.-Strategic-Approach-to-The-Peoples-Republic-of-China-Report-5.24v1.pdf. Accessed 7 September 2020.

- 53.The White House. 2020. United States Strategic Approach to the People’s Republic of China. May 26. Retrieved from https://www.whitehouse.gov/articles/united-states-strategic-approach-to-the-peoples-republic-of-china. Accessed 7 September 2020.

- 54.Timmer, Marcel P., Bart Los, Robert Stehrer, and Gaaitzen J. de Vries. 2016. An anatomy of the global trade slowdown based on the WIOD 2016 Release. The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies – wiiw, November 9. Retrieved from https://wiiw.ac.at/an-anatomy-of-the-global-trade-slowdown-based-on-the-wiod-2016-release-n-176.html. Accessed 7 September 2020.

- 55.US Trade Representative. 2018. 2017 report to congress on China’s WTO compliance. January 2018. Retrieved from https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/files/Press/Reports/China%202017%20WTO%20Report.pdf. Accessed 7 September 2020.

- 56.US-China Economic and Security Review Commission. 2017. 2017 Report to Congress of the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission. November 2017. Retrieved from https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/annual_reports/2017_Annual_Report_to_Congress.pdf. Accessed 7 September 2020.

- 57.Wallerstein I. World-systems analysis: An introduction. London: Duke University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Walter, Andrew. 2013. Addressing global imbalances. In China Across the Divide: The Domestic and Global in Politics and Society, ed. Rosemary Foot, 152–175, Oxford: Oxford University press.

- 59.Wang Z. Understanding Trump’s trade policy with China: International pressures meet domestic politics. Pacific Focus. 2019;34(3):376–407. doi: 10.1111/pafo.12148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang Z, Zeng J. From economic cooperation to strategic competition: Understanding the US-China trade disputes through the transformed relations. Journal of Chinese Political Science. 2020;25(1):49–69. doi: 10.1007/s11366-020-09652-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang, Zhi, Shang-Jin Wei, Xinding Yu, and Kunfu Zhu. 2017. Measures of participation in global value chains and global business cycles. NBER working paper no. 23222. Retrieved from https://www.nber.org/papers/w23222. Accessed 7 September 2020.

- 62.World Bank Group. 2019. Global Value Chain Development Report 2019: Technological Innovation, Supply Chain Trade, and Workers in a Globalized World. April 15. Retrieved from http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/384161555079173489/Global-Value-Chain-Development-Report-2019-Technological-Innovation-Supply-Chain-Trade-and-Workers-in-a-Globalized-World. Accessed 7 September 2020.

- 63.World Bank Group. 2020. Global Economic Prospects. June 2020. Retrieved from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/33748/9781464815539.pdf?sequence=20&isAllowed=y. Accessed 7 September 2020.

- 64.World Trade Organization. 2020. Trade set to plunge as COVID-19 pandemic upends global economy. April 8. Retrieved from https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/pres20_e/pr855_e.pdf. Accessed 7 September 2020.

- 65.Xi, Jinping. 2014. To accelerate the implementation of innovation-driven development strategies. Xinhua, August 18. Retrieved from http://www.xinhuanet.com//politics/2014-08/18/c_1112126938.htm. Accessed 7 September 2020.

- 66.Yilmaz S, Li B. The BRI-led globalization and its implications for east Asian regionalization. Chinese Political Science Review. 2020;5:395–416. doi: 10.1007/s41111-020-00145-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yang, Yifan and Xuechen Chen. 2020. Globalism or nationalism? The paradox of Chinese official discourse in the context of the COVID-19 outbreak. Journal of Chinese Political Science. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11366-020-09697-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 68.Zheng, Yongnian. 2018. Technology cold war and the prelude to the Sino-US cold war. Zaobao, April 24. Retrieved from https://www.zaobao.com.sg/forum/expert/zheng-yong-nian/story20180424-853336. Accessed 7 September 2020.

- 69.Zheng, Yongnian. 2020. Limited globalization after the pandemic. Institute of Public Policy, South China University of Technology, April 17. Retrieved from http://www.ipp.org.cn/index.php/home/blog/single/id/561.html. Accessed 7 September 2020.

- 70.Zhou, Hao. 2020. How soon will economies recover from the coronavirus pandemic? Look to China for answers. South China Morning Post, May 6. Retrieved from https://www.scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3082866/how-soon-will-economies-recover-coronavirus-pandemic-look-china. Accessed 7 September 2020.

- 71.Ziblatt D. Conservative parties and the birth of democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]